Introduction

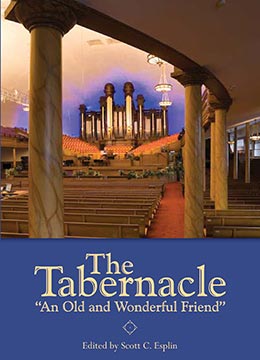

Scott C. Esplin, introduction to The Tabernacle: “An Old and Wonderful Friend” (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2007), 11–63

“It is a peculiar building. I am not acquainted with any quite like it,” President Gordon B. Hinckley observed of the Salt Lake Tabernacle on its 125th anniversary. “It has a character, a spirit of its own. Those who sit beneath its great domed ceiling seem to sense this.”[1] Thousands of visitors to Temple Square, together with the countless others who participate in it by way of broadcast, echo these sentiments regarding the Salt Lake Tabernacle. Together with the neighboring Salt Lake Temple, as President Hinckley later commented, they stand as “two venerable old parents—the Temple, the father, the Tabernacle, the mother—parents of generations that have followed, still standing and shedding light and understanding and knowledge and love.”[2]

President Hinckley is not alone in his veneration of the historic structure. Celebrating its century of service to the Church, President David O. McKay wrote, “The Tabernacle—the Salt Lake Tabernacle—I cannot ever recall thinking of it as just another building of wood and stone. In my parents’ home, at my own fireside, and in the family circles of my children, the Tabernacle has always been as a cherished friend.”[3] Though there are bigger meeting halls worldwide, as President Hinckley continued, the building itself “is different—different in origin, different in its structure, different in its qualities. . . . This building has a spirit, a quality unique and wonderful.”[4] Therefore, as more than just a building, an accurate history of the Salt Lake Tabernacle must include not only details of its unique construction; it must also capture a portion of its spirit.

Stewart Grow and the Preserving of the Tabernacle History

In 1947, author Stewart L. Grow preserved an element of the Tabernacle’s history, together with its spirit, in his classic thesis, “A Historical Study of the Construction of the Salt Lake Tabernacle.” Arguing that is was “appropriate that a history should be written of the most famous building which [Latter-day Saint] pioneer society produced,”[5] Grow endeavored to “present a historical study of the construction of the Salt Lake Tabernacle, in order that the history of the construction of that remarkable building might be preserved, and also to provide a means of giving credit to those pioneer builders who showed such skill and determination.”[6] Sponsored by the History Department at Brigham Young University, Grow’s thesis was later published, in an edited form, by Deseret Book Company under the title A Tabernacle in the Desert.

Contributions of Grow’s thesis. Students of the Tabernacle owe much to Grow’s groundbreaking work. Especially important is the access he had to descendants of those who built the structure. Introducing the work, Grow describes how he hoped to “interview all of the persons who would chance to know anything authoritative about the construction of the Tabernacle.”[7] Though Grow acknowledged that information drawn from the memories of participants “is not completely authentic and cannot be proved,” he argued that the lack of better sources justified its inclusion.[8] The work’s appendix catalogues these interviews, conducted with potentially prominent Tabernacle sources like the children and grandchildren of the four chief architects (Brigham Young, William Folsom, Henry Grow, and Truman Angell), guides on Temple Square, the President of the Temple Square Mission, and officials from the Church Historian’s Office. In addition, Grow had access to officials in the highest levels of Church leadership, interviewing then Church President George Albert Smith as well as three future presidents (David O. McKay, Joseph Fielding Smith, and Gordon B. Hinckley). Though the text does not specify what information came from each individual, a work authored only a generation after the building’s construction and written with access to four Church presidents and numerous other historical experts is critical to our understanding of the Tabernacle’s history.

Need for further study. Though Grow’s thesis provides an important starting point, additional study can be done regarding the Salt Lake Tabernacle. For example, much has been learned about the Tabernacle since he authored his study. In fact, one of the challenges he faced was finding primary sources. Describing the process as “a great deal of ‘leafing through’ the old papers and documents,” Grow lamented the fact that little was indexed from the documents and newspapers of the time.[9] Modern researchers, on the other hand, have a wealth of catalogued, indexed, and even electronically searchable resources available to them. These additional sources aid the researcher in expanding understanding of the Tabernacle.

Furthermore, changes continue to be made to the Tabernacle itself. Though Grow details some of these, including the addition of the balcony, changes in seating, and improvements in safety and technology, significant improvements continue to be made to the structure. Chief among them is the recent renovation the building has undergone in an effort to preserve and protect it. Details of these important changes augment Grow’s excellent work.

Finally, additional significant events have occurred in the historic structure since Grow wrote his thesis sixty years ago. Indeed, the building is more than merely wood and stone. The venue continues to serve as a spiritual and social gathering place for the community, hosting significant gatherings of Church members as well as other civic functions. Even though larger and more modern facilities have been added to Salt Lake City, the Tabernacle continues to be an important part of the downtown landscape.

This introductory essay chronicles some of what researchers, architects, and historians have learned about the historic building since Grow conducted his study. Beginning where he left off, it traces further research on the building and use of the Tabernacle since Grow authored his work. Included are additional details of the hall’s construction, early use, and subsequent renovations. Most importantly, it chronicles significant events housed in the historic structure, including its important ecclesiastical, cultural, and civic uses. Expanding and updating Grow’s study further clarifies our picture regarding the importance of the Tabernacle to the Church and the Salt Lake community.

Additional Research Since Grow’s Thesis

Visitors to the Salt Lake Tabernacle still marvel at two of the building’s components emphasized in Grow’s thesis: the genius of the hall’s construction and the wonder of its acoustics. In 1954, architect Frank Lloyd Wright reportedly called the Tabernacle “one of the architectural masterpieces of the country and perhaps the world.”[10] Decades later, tourist articles similarly summarized:

Salt Lake City’s Mormon Tabernacle is one of the world’s most unusual architectural concoctions: It sits like an enormous inverted bowl balanced atop 44 columns of cut sandstone. This eye-catching design has given the temple unparalleled acoustic qualities. For example, as part of the official tour, visitors are asked to congregate at one end of the building while the guide drops a pin at the other end. Believe it or not, you can hear the proverbial pin drop from as far as 250 feet away!

When the tabernacle was constructed in 1863, Salt Lake was still a frontier town some 800 miles away from the nearest settlement. Today, the temple is a jewel in the heart of a busy western metropolis, a mecca for Mormons and a must-see for everyone else.[11]

Thus, though significant components of Grow’s original text, the wonder of the building’s construction and the phenomenon of its acoustics continue to be emphasized.

Information about construction. Additional insight regarding the Tabernacle’s construction has become available since Grow authored his thesis. One marvel is the staying power of the pioneer construction. In fact, questions regarding the building’s durability existed even during its construction. “Skeptics—of which there are always many,” observed President Gordon B. Hinckley, “said that when the interior scaffolding was taken down the roof would come with it. But the scaffolding was removed and the roof remained intact. It has so remained now for 125 years. Engineers periodically check it. They marvel and find no deterioration or weakening.”[12] Of this fact, architectural historian Carl Condit observed, “Although Salt Lake City’s Mormon Tabernacle, with its enormous turtleback roof, is a celebrated tourist attraction, surprisingly little is known about the structure. Built a century ago (1863-1868), it is the largest work of timber roof framing surviving, and the only one in which lattice trusses were built as arch ribs.”[13]

Though Grow highlights the construction of the Tabernacle, visitors, authors, and architects continue to comment on its unique design and durability. For example, in addition to commenting on the building’s durability, “architects have showered praise on the Tabernacle’s structural ingenuity. For over one hundred years, the Tabernacle was the world’s largest hall without internally supporting columns.”[14] Praise regarding the ingenuity seems to center on the building’s focal point, its unique, turtle-back roof. Addressing the American Society of Civil Engineers at their annual convention held in Salt Lake City, Elder Richard R. Lyman observed, “The most characteristic feature of the structure is the immense roof.”[15] Moreover, celebrating the building’s centennial, the Church’s Improvement Era observed, “One of the unique features of the building, a feather that gives it such marvelous acoustical properties and also allows for uninterrupted sightlines from any seat is the immense dome.”[16] From an academic perspective, Professor Condit similarly commented on the building’s marvelous dome, “The ceiling is plaster embedded with cattle hair, which was laid on lath nailed to rafters fixed in turn to little wooden hangers suspended below the lowermost struts, braces, and ribs of the framing system. The underside of the rafters was cut to conform to the profile of the vault curve. There has been very little cracking of the plaster, and since the double shell of the roof and ceiling provides ideal protection for the structural system, there has been no deterioration of the framing members.”[17]

One insight gained since Grow authored his study centers on the method of construction itself. Throughout his thesis as well as consistently in other sources on the Tabernacle, mention is made of architect Henry Grow’s employing the “Remington Patent of Lattice Bridges” as a model for construction. The architect Henry Grow himself even boasted about the innovative construction method on the back of his business card. However, at least one recent historian questions this claim, observing, “Standard historical treatments of American bridge design and construction fail to mention the Remington technique or any patent associated with it. Grow’s claim to have the right to such a procedure may have been a marketing device to further his Utah reputation and business.”[18] Though his experience building bridges was used in constructing the Tabernacle, there may have been no official Remington technique or an associated patent.

Additional understanding about the construction of the roof itself has also come to light. In the thesis, Grow emphasizes that “the operation of building of the end portions of the Tabernacle was one of the most difficult of the entire construction process.”[19] Further inspection of the roof itself verifies this difficulty, especially as it is related to attaching the roof to the supporting stone pillars. In fact, some mistakes may have been made in the construction process. Architect Carl Condit observed, “The suspicion that [architect Henry] Grow may have miscalculated the shape and size of the piers is suggested by diagonal cracks following the joints near the base of several piers. Although the structural integrity of the Tabernacle is not jeopardized, the cracks do indicate that some adjustment in the masonry has occurred as a result of the bending moment of the arch thrust. A new equilibrium was established, and no further displacement appears likely.”[20] Given this, it is little wonder that some originally questioned the structural integrity of the building. It appears from further study that the architects themselves may not have always known exactly how to make the building work.

Information about the interior. The interior of the Tabernacle is another area that has gained significant additional understanding since Grow authored his thesis. In his work, Grow focused largely on the exterior construction of the hall. However, Grow makes some mention of the interior, especially regarding the installation of the gallery and completion of the famous Tabernacle organ in 1870. Additional detail is also given regarding expansions and improvements made to the organ through 1938. Finally, a brief four-page chapter concluding Grow’s work summarizes the addition of gas and electric lighting, attempts at controlling the building’s temperature, changes made to the speaker’s stand and choir loft, and painting. Though these interior changes are important, the brief detail in the Grow’s thesis inadequately covers these and the numerous other improvements that have been made to the inside of the building.

Decorating the vast interior of the structure is one important change that has occurred over time. Of the early structure, historian Ronald Walker observed, “Early photographs show a bare and gloomy interior, and the Mormons themselves described the building’s first days as one of ‘rough lumber and scanty paint.’”[21] In fact, one visitor called the Tabernacle “the dreariest of white-washed buildings inside.”[22] Another remarked that “the inside is vast, dreary, and strikes one with a chill.”[23]

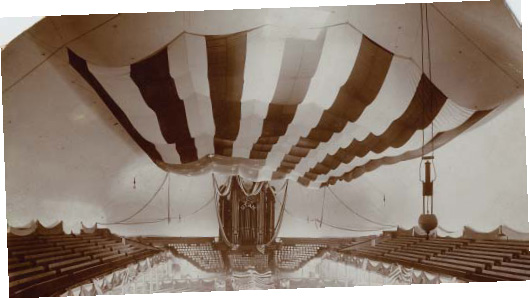

Ronald Walker’s excellent article, “The Salt Lake Tabernacle in the Nineteenth Century: A Glimpse of Early Mormonism,” does much to clarify understanding regarding the Tabernacle’s interior. For example, possibly in response to the building’s bare interior, decorations were frequently used within the Tabernacle, something rare within Church meeting halls today. Walker notes that within several months of the building’s dedication in 1875, “‘an immense blue banner emblazoned with a golden beehive’ was hung on the rear wall of the building.”[24] Placed by the Deseret Sunday School Union, the beehive, together with the caption beneath, “By Industry We Thrive,” was designed to remind children of the importance of work. At the west end of the building, similar symbolic reminders were also added, including a star, at times accompanied by the word “Utah,” located above the seats. In addition, the phrases “In God we put our trust” and “Under the everlasting covenant God must and shall be glorified” were draped amongst the organ pipes.[25] Additionally, the hall was frequently adorned with American flags and red, white, and blue bunting, symbol of American loyalty by the Saints. In fact, as part of Utah’s 1896 statehood celebration, the ceiling was draped in an enormous American flag measuring 75 by 160 feet, from which “the space designating Utah’s ‘forty-fiftieth’ star was cut from the banner to allow the placement of an electrically lighted star.”[26]

Photographs from other occasions illustrate similar decorative techniques, including garland, festoons, and flowers. Often, like the use of the numerous flags for the statehood celebration, these decorations were part of various commemorations held in the building. In fact, one account describes on the left of the organ “a large collection of sage-brush, with small sun-flowers, and one small pine tree, and on a large calico strip, [and] the figures 1847. . . . On the right-hand side of the organ were sage-brush, sunflowers and every variety of flowers; and amongst them all, in great figures, 1880.”[27] According to a tourist’s account, this was all to symbolize “that when the Mormons came to Utah . . . they found not a single blade of grass in the region; nothing but sagebrush, sunflowers, and pine trees.” By the 1880’s, the settlers had made the region blossom. These and other decorations were typical of the building’s interior in the nineteenth century.

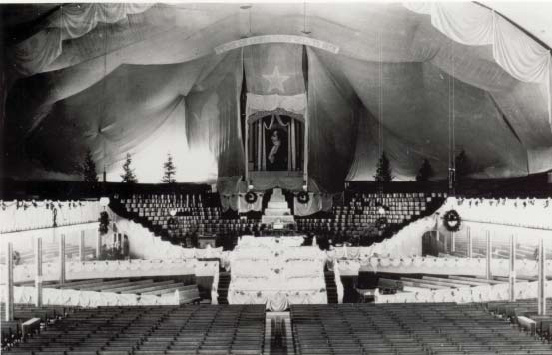

Wilford Woodruff's funeral, 1898, provides an example of the decorations used in the Tabernacle at the turn of the century.

Wilford Woodruff's funeral, 1898, provides an example of the decorations used in the Tabernacle at the turn of the century.

The Tabernacle interior decorated for the statehood celebration, 1896.

The Tabernacle interior decorated for the statehood celebration, 1896.

Tabernacle interior, around the 100th anniversary of Joseph Smith's birth, December 1905.

Tabernacle interior, around the 100th anniversary of Joseph Smith's birth, December 1905.

Funeral of John Taylor in the Salt Lake Tabernacle, July 29, 1887. The lion statues on either side of the stand may be the same statues that surrounded the fountain formerly in the center of the Tabernacle.

Funeral of John Taylor in the Salt Lake Tabernacle, July 29, 1887. The lion statues on either side of the stand may be the same statues that surrounded the fountain formerly in the center of the Tabernacle.

The lion statue used in the 2007 Church History Museum exhibit on the Tabernacle. It has been bronzed since the earlier 1800s photo.

The lion statue used in the 2007 Church History Museum exhibit on the Tabernacle. It has been bronzed since the earlier 1800s photo.

Ironically, while some visitors complained of the building’s bland interior, others remarked on the worn-out nature of the decorations used to remedy the situation. Walker observed that “once the resplendent decorations were in place, they might remain on display long after the event—far too long, according to some fastidious visitors. These critics spoke of ‘faded evergreen wreaths and tawdry flags,’ ‘old and withered’ garlands, and shopworn Christmas wreaths and evergreens. ‘B. E. E.,’ the author of Wanderings in Distant Lands, complained that one chandelier of ‘withered evergreens’ bore the ‘dust of seven years.’”[28]

While for some the faded remnants of forgotten festivals remained in the building far too long, other decorations within the Tabernacle’s interior were of a permanent nature. In fact, unlike current buildings used for Church worship, the Tabernacle itself displayed several prominent illustrations for a number of years. “These included several historical murals, one of which showed Joseph Smith receiving the Book of Mormon golden plates. After the turn of the century, the Mormons also hung a portrait of Smith, several times larger than life, between the Tabernacle organ’s biggest pipes. This portrait was set off by a festoon of white cloth. Inscriptions above and below the painting read: ‘Peace on earth good will to men’ and ‘The glory of God is intelligence.’ Both were illuminated by electric lights.”[29] In addition to paintings, statues were also used in decoration. For the 1875 jubilee celebration, Church leaders “placed a ‘gilded and shaded figure’ of a heavenly messenger, sounding the gospel trumpet to ‘every kindred, tongue and people,’” above the organ.[30] Later, the highest pulpit itself was even adorned with lion statuary on either side for a period of years, a reminder of Brigham Young as the “Lion of the Lord.”[31]

Unique among all decorations on the interior of the Tabernacle was a white ornamental fountain that, for a number of years, “occupied the center of the main floor, about a dozen or so benches from the west-end rostrum.”[32] Placed in the building as part of an 1875 grand youth “jubilee,” it represented the “living water” offered by Christ and His gospel.[33] Grow’s thesis makes brief mention of the object, including the humorous account of one youngster frolicking in the water during a meeting. Several pictures of the Tabernacle’s interior capture its prominent location in the center isle of the building for a number of years.

What we still don’t know. While additional research has brought us much knowledge regarding the Tabernacle itself since Grow wrote his thesis, several significant details are still unknown about the building. Near the end of his thesis, Grow discusses various questions regarding the Tabernacle in his day, several of which remain questions. For example two questions regarding how the idea for the shape of the Tabernacle originated and whether or not plans were ever drawn for the building remain a mystery. Concerning the origination of its shape, one writer observed, “No architectural drawings are in existence today, so just what detailed plans were drawn is not known, nor is it known how the unique shape of the building was decided upon.”[34] An Improvement Era issue celebrating the Tabernacle’s one-hundredth anniversary mentioned five different possibilities under the title, “Popular Tales,” concluding that “the full account seems to have been lost with the passing of years.”[35]

The question of the building’s famous acoustics also continues to be discussed by researchers and visitors to the Tabernacle. Grow apparently relied heavily on the 1930 acoustical analysis by Wayne B. Hales, wherein he analyzed various sound patterns throughout the entire structure. More recently, Condit explained these details:

The celebrated acoustical properties of the Tabernacle are a result of both shape and material. The concave ellipsoidal surfaces above the organ and choir blend and hold instrumental and vocal sounds, projecting the reflected waves cleanly throughout the auditorium. The possibility of annoying echoes is further reduced owing to the sound absorbency of the cattle hair embedded in the plaster.

How much of this acoustical excellence is a matter of luck and how much of experience and intuition is difficult to judge today. The structural system is for the most part perfectly functional, revealing an imaginative adaptation of the bridge-builder’s art to the requirements of a large public building. The over-all shape, however, seems to have been dictated by the idea of the most convenient form to include the volume, rather than by the search for good acoustical properties. Thus the solution to one problem brought with it the means to solve another—a coincidence that often characterizes the old craft tradition in building.[36]

In praise of these dynamics, Elder Richard R. Lyman observed, “It was once commonly believed, and many people still believe, that the general design for this building was a result of inspiration. Certainly there is no other building like it. As regards acoustics, the elliptical plan, according to architectural authorities, is the perfect section if the ceiling also be elliptical. The Tabernacle is popularly considered the most acoustically perfect structure of any magnitude in the world.”[37] More recently, another author observed, “Without question, the Tabernacle ranks with the Baptistery at Pisa and the Greek Theatre at Epidaurus as among the several acoustical wonders of the world.”[38]

The final discussion point from Grow’s thesis, namely who should receive credit as Tabernacle architect, seems more settled, though some question remains. Cognizant of his relationship to Henry Grow, one of the primary architects of the building, Stewart Grow cautiously attempted to “minimize the effects of family pride.”[39] Citing then Church publicity official Gordon B. Hinckley, Grow indicates that a compromise “had been arrived at as a result of family pressure and the lack of historical proof to the contrary.”[40] Grow’s analysis, though presented in discussion form, seems to have carried the day. A later author observed,

Although through the years some dissension has existed as to which individual played the greater part in bringing into existence the magnificent Tabernacle on Temple Square, conscientious examination of the great mass of available information has led us to believe that four men should share equally in the laurels: Brigham Young for his foresight in realizing the need for such a building, and his genius in planning it; William H. Folsom for his masterful handling of the exterior; Henry Grow who directed the building of the unique and distinguished roof; and Truman O. Angell, who with great finesse completed the interior.[41]

The American Society of Civil Engineers likewise seems to have sided with Grow. When designating the Tabernacle as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark, the printed program stated, “The Tabernacle was built during the administration of Brigham Young, second President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. William H. Folsom directed construction of the exterior; Truman O. Angell, the interior; and Henry Grow designed and supervised construction of the unique arched roof.”[42]

Most recently, another descendant of architect Henry Grow likewise weighed in on the debate. Of the four chief architectural participants (Brigham Young, William Folsom, Henry Grow, and Truman Angell), Nathan Grow wrote, “All four men made essential contributions to the building’s design and construction. All four were ‘architects’ of the building, and all four should receive credit for contributing to its significance.”[43] He based his conclusion on historical definitions of an architect. A 1902 description of the architect’s role observes,

Obviously, an architect may be charged with any part of this work, and may leave it to another at any state of the proceedings. The man is equally an architect who, having undertaken the task of carrying the whole building to a conclusion, dies after the lot is chosen, the drawings made, and the main lines are staked out upon the ground. Equally is he an architect who, taking charge of a building nearly finished, carries it to completion, including its decorations and final preparations for use. The term signifies nothing more than head workman or director of the workmen, and the exact duties of the architect vary with the epoch, the country, the kind of building, and the wishes of the owner.[44]

In summary, “a given building may have more than one architect. The term can be applied to anyone who at any time has control over design or construction.”[45] In this case Brigham Young acted as originator of the plan, William Folsom as early designer, Henry Grow as roof specialist, and Truman Angell as interior finisher. By this description, all four men occupy the position of architect of the Salt Lake Tabernacle, a conclusion hinted at by Stewart Grow.

Changes to the Tabernacle Itself

While additional information has become available regarding the original construction of the Tabernacle since Grow wrote his thesis, the building itself has also undergone significant renovations. Thus, as the building has changed, updates to Grow’s thesis have become necessary.

Many of the changes in the historic structure involve technological and safety improvements. On the occasion of the building’s centennial, the Church’s Improvement Era summarized some of these changes, “The building has been remodeled and changed through the years as science and technology have opened new doors and avenues to improvement. The choir loft has been rebuilt half a dozen times; new electrical and heating systems have been installed; broadcast facilities have been added; the balcony stairs have been remodeled to allow for outside rather than inside access; and many other improvements have been made.”[46]

Lighting system used for broadcasts and Tabernacle productions.

Lighting system used for broadcasts and Tabernacle productions.

Lighting and heat. Some of the earliest technological advancements brought to the building involved lighting and heat. Though the numerous doors and window provided some natural light during the day, the necessity of artificial lighting soon became evident. A similar need was quickly recognized for heating the hall as functionality was hampered during the cold winter months. In 1884, a heating and lighting system was installed. Three hundred gas-filled jets flooded the hall with light. Gradually, the gas was replaced with electricity, as the Tabernacle became one of the first structures in Utah to have electric lighting.[47] Later lighting changes have been driven by the needs of the various productions that originate from the structure. For example, when it was determined to improve the lighting for live and broadcast productions, engineers were forced to find a way to make changes without damaging the structure. Ultimately, it was determined to pass the cables and wiring through holes left in the ceiling for maintenance so as to “in no way impair the acoustics of the auditorium.”[48] This and other balancing acts between technological updates and preservation of the historic structure characterize the history of the improvements to the Tabernacle.

Moderating cold temperatures in the historic structure was also addressed with technology. One historian observed,

In pioneer days the great hall could not be heated, which resulted in little use of the building during cold weather. It is said that at one time a pot-bellied stove stood in the middle of the building, although there is no evidence as to where the stovepipe ran. For many years, in order to conserve heat, a great canvas partition swung from the ceiling to the floor directly through the center of the great auditorium, shutting off the eastern section, the western section facing the pulpit usually being large enough to accommodate the congregations that met for Sunday worship. It was only during conference, or for other large gatherings, that the canvas was drawn up and the whole of the building used. In due time, steam heating was provided.[49]

Improvements to the heating have made the building more functional in the winter, though heat still plagues the building during the summer.

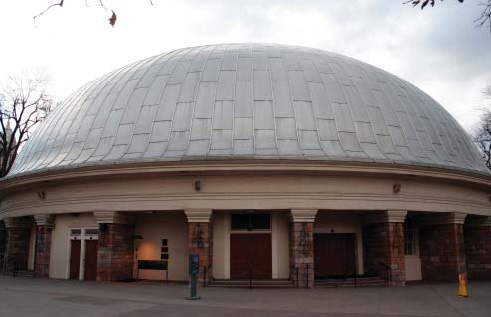

Over time, the Tabernacle roof has had several surfaces, including wood and metal, such as the aluminum roof shown above, which was installed in 1947.

Over time, the Tabernacle roof has had several surfaces, including wood and metal, such as the aluminum roof shown above, which was installed in 1947.

Safety additions. Furthermore, while improvements in lighting and heat have increased the functionality of the Tabernacle, safety improvements have also increased its longevity. The Improvement Era remembered some famous near-disasters over the life of the building, “The days of the Tabernacle have not been without excitement. During a Fourth of July celebration in 1887, fireworks ignited the roof, but, according to Church historical records, ‘the flames were promptly put out by the fire brigade before doing much damage.’ . . . In 1933 water pipes froze and burst one bitterly cold night, causing extensive damage to some of the walls and carpets. Six inches of water accumulated in the basement under the organ, but the organ itself was not touched. On a quiet January Sunday in 1938, four men were found spraying gasoline on the building. During the ensuing scuffle, one of them was severely burned.”[50] These and other potential disasters prompted safety improvements in the structure.

One major threat facing the nearly all-wooden structure was fire. Originally covered with 400,000 wooden shingles, the roof posed the biggest threat to a stray spark. “Because of wear and weather, this roofing was replaced at the turn of the century with sheet tin, which was covered with canvas and tar. A new aluminum roof was put on during the Utah Centennial year of 1947,” the same year Grow wrote his thesis.[51] In the interior, changes were also made to protect the structure from fire. A sprinkling system was added to the interior of the roof in 1930. Made of a soft metal, it was designed to melt and release a spray of water in the event of a fire.[52] In addition, alarms were linked with local Salt Lake City fire departments to notify them of the danger.

After protecting for fire, Church leaders sought to protect the building from other natural disasters, especially earthquake. “In 1942 the entire roof was reinforced by angle-iron stringers being welded together. This was built only as a matter of protection against an earthquake to keep the plaster from falling, particularly if the building was being occupied at the time.”[53] Though these measures undoubtedly help, further protecting occupants and the structure itself from possible harm seems to be a current concern of Church leaders. Announcing the Tabernacle renovation in 2005, they stressed, “The Mormon Tabernacle on Temple Square in Salt Lake City is undergoing a two-year renovation to bring the building into conformity with modern safety and seismic codes.”[54]

Comfort and utility. In addition to improving safety, Church officials have sought to increase comfort and utility in the historic Tabernacle. For example, in 1951 a quiet room was added to the General Conference broadcast, improving meeting facilities for members with young families. Later, in 1968, a full basement was dug underneath the building to house mechanical equipment, radio and television facilities, offices, and storage. Especially important was the addition of dressing and storage facilities, though limited, for use by the famous Mormon Tabernacle Choir. Further improvements in this regard will be made during the current renovation. Commenting on the project, President Gordon B. Hinckley observed, “We must do extensive work on the Salt Lake Tabernacle to make it seismically safe. . . . The time has come when we must do something to preserve it. It is one of the unique architectural masterpieces in the entire world and a building of immense historical interest. Its historical qualities will be carefully preserved, while its utility, comfort, and safety will be increased.”[55]

Though efforts have been made to improve the comfort of the Tabernacle, one source of continual discomfort and, at times, disappointment with the structure, has been the seating. In fact, while announcing the construction of the neighboring Conference Center as a replacement for the Tabernacle, President Hinckley remarked,

I regret that many who wish to meet with us in the Tabernacle this morning are unable to get in. There are very many out on the grounds. This unique and remarkable hall, built by our pioneer forebears and dedicated to the worship of the Lord, comfortably seats about 6,000. Some of you seated on those hard benches for two hours may question the word comfortably.

My heart reaches out to those who wish to get in and could not be accommodated.

We recognize, of course, that we can never build a hall large enough to accommodate all the membership of this growing Church. We’ve been richly blessed with other means of communication, and the availability of satellite transmission makes it possible to carry the proceedings of the conference to hundreds of thousands throughout the world.

But there are still those in large numbers who wish to be seated where they can see in person those who are speaking and participating in other ways.[56]

Later, at the first General Conference held in the completed Conference Center, President Hinckley further remarked, “The Tabernacle, which has served us so well for more than a century, simply became inadequate for out needs.”[57]

President Hinckley is not alone among prophets in expressing concern about seating the saints in the Tabernacle. On the occasion of the building’s centennial, President David O. McKay observed, “Wherever I see Temple Square literally overflowing with Saints and know that there are additional thousands who would like to come, I wish there were some way to provide room for them in the Tabernacle. Whenever I see the Tabernacle crowded to capacity, which is often, I have a re-affirmation of the strength of the Church.”[58]

In his thesis, Grow highlighted the problem presented by limited capacity even when the Tabernacle was first opened. During the last General Conference before the building was completed, George A. Smith remarked, “I expect that by the time our great Tabernacle is finished, we shall begin to complain that it is too small, for we have never had a building sufficiently large and convenient to accommodate our congregations at Conference times.”[59] Brigham Young similarly observed, “I expect . . . that by the time our building is finished we shall find that we shall want a little more room. Mormonism is growing, spreading abroad, swelling and increasing, and I expect it is likely that our building will not be quite large enough.”[60] Even with the addition of the gallery in 1870, the editor of the Deseret News still remarked, “We scarcely think there need be any fear entertained of lack of room, though there never was a time in the history of the Latter-day Saints—no matter how large the building might be which they had to meet in—when the people could find sufficient room to hold their conferences.”[61] Indeed, according to a later account of the conference, the gallery was full “some time before the commencement of the meeting.”[62]

Improving the sound. Though getting everyone under one roof was always problematic, hearing the speaker once inside was also a major challenge. Of the outdoor venues used before construction of the Tabernacle, George A. Smith observed, “It requires a great effort for even a man with sound lungs to make ten thousand persons hear him speak distinctly.”[63] Though completing the Tabernacle helped, leaders and members still faced a challenge. At the first conference, the Deseret News reported, “When the audience is as still as it always should be, it will requite very little, if any change, to make it a very easy place to speak in, especially after the speakers . . . become familiar with the building, and the government of their voices to the situation of the audience.”[64]

Though the building is famous for its acoustics, changes have also been made to improve the sound quality in the Tabernacle. Speakers did not always appreciate the way sound reverberated in the hall. Grow noted in his thesis architect Truman Angell’s observation, “It would have been much better if the people would come in at the right hour and be seated and keep seated and stop whispering and keep their feet still.”[65] President David O. McKay summarized the challenge from a speaker’s perspective, “Although dropping a pin has been associated with demonstrating the acoustics of the Tabernacle for as long as I can recall, when I was a junior member of the Twelve, vigorous speaking in the Tabernacle was the order of the day. We had to stand at the pulpit and literally shout.”[66]

One early remedy involved partitioning the building to reduce sound reverberation. A year after the building was opened, Wilford Woodruff recorded in his journal, “[The Tabernacle] was divided in the Middle with a Cotton veil so the people Could hear better & a New canopy over the Priesthood stand. The Building is so large & the arch so high that it is impossible to make all the people so as to [understand].”[67] Though not ideal, the addition of the gallery in 1870 improved the acoustics. Again, Elder George A. Smith observed, “Acoustic properties of the Tabernacle are evidently improved by the erection of the gallery, and if all who attend Conference will leave their coughing at home, sit still while here and omit shuffling their feet, they may have an opportunity of hearing pretty much everything that may be said.”[68] In reality, as Paul H. Peterson observed, “the very acoustical powers of the structure could work against the speaker if the audience were not perfectly quiet.”[69] In the April conference of 1899, Joseph F. Smith highlighted the problem, “It is the wonderful acoustic properties of this house that actually make it so difficult, in one respect, to make the people hear when there are so many together as are here today, because every little sound tends to confuse the voice of the speaker.”[70]

Though Church leaders and members struggled with the problem of hearing in the Tabernacle for nearly fifty years, technological advances provided a solution. “For many of the Brethren,” remarked Paul H. Peterson, “it must have seemed long overdue.”[71] In April 1923, amplification was first used in a Church general conference. Covering the historic advancement, the Deseret News remarked,

For the first time in the history of the Mormon church Conference, a mechanical device is being used to facilitate and increase audition on its part of the persons in attendance. An amplifier of the most modern type, with two receivers and transmitters that project in three directions, has been installed in the tabernacle . . . .

Officials of the presiding bishopric of the church, under whose orders the amplifier was installed, pronounced it a success and conference attendants who sat at the very extreme east end of the building and under the gallery, said they heard distinctly all of the speakers.[72]

Improvements over the years to the amplification system have continued to augment the building’s famous acoustics. Amplifiers and speakers have been added to various parts of the building, especially in some of the hall’s “deaf spots.” One of the more famous of these areas caused one writer to remark, “The building’s acoustics are world famous, but because of deaf spots, particularly in the choir seats, they are anything but a dream for a choir singer—those sitting in the alto section can scarcely hear the basses.”[73]

Broadcasting from the Tabernacle. Other technological advancements soon followed, further expanding the reach of the historic Tabernacle. Radio transmission capabilities were added in 1924, expanding the opportunity for millions to participate, in remote form, as part of the Tabernacle audience. Television brought picture to the sound, becoming a part of Tabernacle events for the October general conference of 1949. These were later first seen in color in 1967. During the same time period, efforts were made to expand the Tabernacle’s influence internationally. Short wave radio broadcasts of general conference, designed to reach saints in Europe, South America, South Africa, and Mexico, first originated from the building in 1962. Satellite transmissions followed, with interested television and cable systems carrying Tabernacle events beginning in 1975. In 1980, conference sessions were first carried by satellite to church centers worldwide. These advances have helped make the historic Tabernacle a widely-recognized image for the growing Church.

The Tabernacle organ is a widely recognized icon of the Tabernacle and of the Church itself.

The Tabernacle organ is a widely recognized icon of the Tabernacle and of the Church itself.

The Tabernacle Choir and organ. While technology has helped make the building well-known to Church members, the Tabernacle Choir and the famed organ that accompanies it continues to be the structure’s primary attraction. As Stewart Grow mentioned in his thesis, “the story of the Tabernacle Choir is a separate one from the building of the Tabernacle, but the great organ is such an integral part of the building itself and so intertwined in its history as to merit separate consideration here.”[74]

The connection between the organ and the building dates back to Brigham Young himself. To choir leader George Careless, President Young reportedly remarked, “We cannot preach the gospel unless we have good music. I am waiting patiently for the organ to be finished; then we can sing the gospel into the hearts of the people.”[75] Since its completion in 1870, visitors have frequently commented on the instrument. Of these early accounts, historian Ronald Walker observed, “The organ was one feature of the Tabernacle—and Mormonism—that visitors praised.”[76] Another commenter remarked, “The renowned organ . . . might well be the most easily recognized musical instrument in the world.”[77] The Church’s Improvement Era noted, “Statisticians estimate that more persons worldwide could recognize a picture of the Tabernacle organ than any other musical instrument.”[78]

Like the building that houses it, the Tabernacle organ has undergone numerous changes throughout the years. Grow’s thesis chronicles many of these improvements, including the frequent reconstruction of the instrument, expansion of the pipes, and even the installation of a water wheel and later electricity to power it. Currently, the organ is ranked on most lists as among the fifteen largest organs in the world, with over 11,600 pipes in 206 ranks.[79] In fact, one organ technician observed, “If a boy started to play the Tabernacle organ when he was four years old and played eight hours a day, changing combinations every fifteen minutes until he was 94 years old, he still wouldn’t have exhausted all of the meaningful combinations.”[80] The sound produced by the versatile instrument is accented by the structure of the Tabernacle itself. “Unlike most other organs, the Tabernacle organ was placed inside an acoustical shell. The building’s nearly all-wood nature returns the organ tones like a great cello.”[81]

The world-famous Mormon Tabernacle Choir goes hand in hand with its remarkable instrument. Of the connection, President Stephen L. Richards quipped, “I would not venture to say whether the Tabernacle has made the choir or the choir has made the Tabernacle famous.”[82] Whichever the case, Grow only briefly mentions the history of the choir in his thesis, but many of the changes implemented in the Tabernacle over the years have been necessitated by the technological demands of the choir. The first radio broadcast of the choir, held on Monday, July 15, 1929 to thirty different stations, involved stringing a single microphone from the ceiling of the Tabernacle with a ladder placed below it. Ted Kimball, nineteen-year old son of organist Edward P. Kimball, stood atop the ladder throughout the broadcast to announce the songs.[83] Seventy-eight years and more than 4000 broadcasts later, the Tabernacle Choir and Music and the Spoken Word continue to be associated with the famed hall. The broadcast was first moved to television in 1962. Though the choir was displaced from the building by its recent renovation, Church officials announced, “The organ will be carefully protected throughout the renovation and will resume its place as the focus of Temple Square music when the Tabernacle reopens.”[84] Choir broadcasts, including Music and the Spoken Word, are likewise scheduled to return.

The 2007 Tabernacle renovation. The current renovation itself is the most recent significant change to the Tabernacle since Grow authored his thesis. Announcing the renovation, President Hinckley remarked, “Buildings, like men, grow old. They don’t last forever unless you look after them, and this building is old now.”[85] The improvements made by the Church during renovation reflect an attempt to preserve and protect this jewel of Church architecture. A primary goal of the renovation project included historical preservation. President Hinckley continued, “I respect this building. I love this building. I honor this building. I want it preserved. I want the historicity of it preserved. I don't want anything done here which will destroy the historical aspect of this rare gem of architecture. Now in the process of working on it, they'll have to put in some steel work, yes, and so on. But I don't want a modern, 2004-2005 building. I want the old original Tabernacle, its weak joints bound together and preserved and strengthened and its natural and wonderful beauty preserved and strengthened.”[86] In fact, he warned those involved in the project, “Now, [to] the engineers, the architects, I just want to say, be careful. Don’t you do anything you shouldn’t do, but whatever you do, do well and do right. . . . Now [Bishop H. David Burton is] going to take you through an exercise on exactly what they’re going to do. But I am going to say this, when the drawings are all complete, I’m going to take another look at them to see that nothing is destroyed that shouldn’t be destroyed.”[87]

The recent renovation brought about several changes, including the addition of interior steps facilitating easier access to the gallery.

The recent renovation brought about several changes, including the addition of interior steps facilitating easier access to the gallery.

The most important aspect of the project was reinforcing the structural integrity of the building, with the building’s foundation and balconies slated to be strengthened to withstand potential earthquake.[88] Jacobson Construction, the company contracted for the project, summarized, “This historic renovation and seismic upgrade will stabilize the existing structure by adding supplemental framing and reinforcing bars to walls and roof. A general refurbishment of the interior will also take place including remodeling the existing spaces used by the Tabernacle Choir and the Orchestra at Temple Square. Special precautions and building techniques will be applied to preserve the historic nature of the building.”[89] Of this process, Bishop H. David Burton remarked, “We hope in a very inauspicious way to structurally strengthen the building.”[90] Leaders also noted that the building was lacking in structural integrity in some places. They hoped to more securely attach the roof to the walls and pillars. On the interior, the changes consisted of “renewing what is here.” The balcony would be seismically reinforced, but Bishop Burton stressed, “for most eyes, you won’t be able to detect it.”[91] One major change to the interior would be the seating. Church spokesman Dale Bills remarked, “Some of the original benches are being placed back into the building; others will be replaced with oak replicas to maintain historicity.”[92] The change may also mean a reconfiguration of seating, with a corresponding loss in capacity, to improve leg room for modern audiences. Additionally, changes were made in the building’s underground portions, including the additions of dressing rooms, restrooms, and a library to better support the 350 voice Mormon Tabernacle Choir. Summarizing the renovation, Bishop Burton promised that the “ecclesiastical opportunities will be increased.”[93]

The Spirit of the Building

While a history of the building’s construction and renovation itself is important, the Salt Lake Tabernacle is also unique because of the significant spiritual, cultural, and social events that have occurred there. Summarizing these occasions, President Hinckley remarked, “What a remarkable and useful building it has been. What great purposes it has served. I know of no other structure like it in all the world.”[94] Summarizing the building’s remarkable utility, he continued,

It has served the needs of this Church and this community through all of these years. General conferences of the Church have been held here. The voices of prophets have spoken out from this podium. The law and the testimony have been quoted and declared. Numerous other Church meetings have been held here. In this magnificent old structure the funeral services of beloved leaders have been conducted. Presidents of the nation and other distinguished men have spoken from where I now stand. This has been home to the Tabernacle Choir since the structure was completed. More recently it has been home also to the Mormon Youth Chorus and Symphony. It was the first home of the Utah Symphony. Handel’s Messiah has been presented here over a period of many years. Countless concerts of various kinds, a variety of musical ensembles, and many distinguished soloists have all entertained the public in this great and singular hall.[95]

Indeed, because of these and other significant events, the Tabernacle seems to have developed “a personality of its own.”[96]

The Tabernacle as missionary tool. One of the early contributions of the Tabernacle was as a missionary tool for the Church. Commenting on this characteristic, Elder Howard W. Hunter observed, “[The Tabernacle] has stood as a great missionary, introducing the gospel of Jesus Christ to people all around the world—those who have entered its portals and those who have heard the message that has gone forth from here in music and the spoken word.”[97] The building itself introduces Mormonism to everyone that encounters it.

Even in its earliest days, the Tabernacle impacted visitors, largely because of its size and location in the pioneer west. “This great structure, enormous at the time of its building,” remarked President Stephen L. Richards, “is the physical embodiment of a mighty concept that the work of God is expansive, all-embracing, with room for all who will come and listen and receive.”[98] Of the visitors who toured the structure, historian Ronald Walker similarly observed, “Everyone agreed that the building was big, especially for its time. Travelers to Salt Lake City used such words as ‘huge,’ ‘extraordinary,’ ‘immense,’ and a ‘monster in size’ to voice their awe. . . . . [However,] admiration for the building’s engineering and size did not necessarily translate into praise for its design.”[99] After lauding the orderliness of the city itself, one eastern visitor remarked, “The far-famed tabernacle strikes one as a huge monstrosity, a tumour of bricks and mortar rising on the face of the earth. It is a perfectly plain egg-shaped building, studded with heavy entrance doors all around; there is not the slightest attempt at ornamentation of any kind; it is a mass of ugliness; the inside is vast, dreary, and strikes one with a chill, as though entering a vault.”[100] Others remarked that the building had “no more architectural character . . . than . . . a prairie dog’s hole.”[101]

Some of the disdain may have stemmed from disregard for the building’s sponsoring faith, causing the Tabernacle to became “a frequent target for caricature.”[102] Some called it “the Church of the Holy Turtle,” others “half an eggshell set upon pillars.” Additional comparisons included a “culinary serving dish . . . , Noah’s ark had it been capsized . . ., [and] balloons, bathtubs, bells, watermelons, a whale, and even mushrooms.” In a moment of hyper-exaggeration, one man even remarked, “For my part, I decided that, so far as my experience goes, the oval tabernacle . . . is unsurpassed, even by its neighboring preaching shanty, for oppressive ugliness among all the buildings now standing in the world.” Historian Ronald Walker summarized, “In short, the building was a gigantic curio, something ‘strange’ and ‘unique,’ to be talked or written about because of its outlandishness. ‘We have never seen anything like it,’ said a British minister.”[103]

Though disagreeing with the design, one visitor did note that “its acoustical properties are wonderful” and that Church members are and should be “justly proud” of the organ, for “notwithstanding its immense size, it has not a single harsh or metallic sound; on the contrary, it marvelously soft-toned; from the low flute-like wailing voice of the vox humana to the deep bass roll which stirs the air like a wave of melodious thunder, it has all the delicacy of the Aeolian harp, with the strength and power of its thousand brazen voices.”[104] Ronald Walker observed, “It was one thing to stand outside the Tabernacle and observe its oddity; it was another to enter its sanctum. It was here that visitors could better see that the Tabernacle did its tasks well.”[105] Apparently, though not agreeing with the entirety of the building, some visitors were won over by other aspects.

In addition to its missionary influence by impacting visitors, the Tabernacle has also served as the hub of the Church’s missionary work. “In the earlier days,” observed President Stephen L. Richards, “the missionaries were personally called from the stand in this Tabernacle. One can well imagine the thrill and deep impression made by such procedure. Here the courses of life were changed by assignments from the Presiding Brethren.”[106] More recently, the Tabernacle has expanded its role as a missionary tool. Of its importance, President Richards remarked that the building “may appropriately be designated as the center of our missionary work.”[107] Sermons originating from its pulpits have circulated the world by various means proclaiming the truths of the everlasting gospel. Additionally, the Tabernacle Choir’s Sunday program, Music and the Spoken Word, has historically originated from the structure, making “an invaluable contribution to our missionary endeavor in bringing to our missionaries a more kindly and considerate reception as they bear the message of the gospel from door to door out in the world.”[108] The hall has also created missionary opportunities for the over one-million people that visit Temple Square annually.

The Tabernacle as pioneer meetinghouse. While a showcase for visitors to the area, the Tabernacle was primarily the meetinghouse for the early saints. “Its presence was more than physical,” observed historian Ronald Walker. “The Tabernacle was, after all, the most important public building of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the last part of the nineteenth century. It was where the Saints came to worship each Sunday, weather permitting. It was also where thousands of outsiders came to see Mormons firsthand; and after their visits, they recorded details that Zion’s own men and women often failed to mention. In short, the Tabernacle was where early Mormonism revealed itself to contemporaries.”[109]

Initially, the Tabernacle served as the Saints’ primary meeting place in the Salt Lake valley. Morning and afternoon meetings were held on Sundays for anyone in the area, with preaching in the early meeting and the administration of the sacrament in the latter. Describing the administration of the ordinance, Ronald Walker wrote, “To accomplish the task, the bishops began at the start or the meeting by breaking the stacked piles of bread on the bishops’ table into small pieces. The officiator then signaled the speaker to pause for a prayer of blessing, which might be offered by one of the bishops, standing with both arms raised in supplication. After a small squad of men passed the bread to the congregation, a similar ceremony was completed for the sacramental water. Most of the two-hour meeting was required to complete the ordinance.[110]

Slowly, general meetings in the Tabernacle were replaced by those held in neighborhood ward buildings. In 1894, Church leaders discontinued the sacramental service at the Tabernacle, encouraging members to partake in their local congregations.[111] Gradually, local meetings replaced the general one held in the Tabernacle, though Sunday afternoon services, largely for visitors, continued into the 1920s.[112] Since this time, the building has largely been used for special occasions rather than weekly worship services.

The Tabernacle as home for general conference. Though the weekly meetings from the pioneer era ended in the Tabernacle in the early twentieth century, the building continued to serve as the primary location for the Church’s general conferences. In the building’s 1875 dedicatory prayer, Elder John Taylor emphasized the importance of these prophetic conference messages, asking God to bless the building as “a holy and sacred place wherein thy servants may stand forth to declare thy words and minister unto thy people in the name of thy Son forever.”[113] Regarding these messages, Elder Taylor further prayed,

May thy holy angels and ministering spirits be in and round about this habitation, that when thy servants are called upon to stand in these sacred places, to minister unto thy people, the visions of eternity may be open to their view, and they may be filled with the spirit and inspiration of the Holy Ghost and the gift and power of God; and let all thy people who hearken to the words of thy servants drink freely at the fountain of the waters of life that they may become wise unto salvation, and thereby overcome the world and be prepared for an everlasting inheritance in the celestial kingdom of our God. . . .

We pray thee to bless the Twelve Apostles; fill them with the spirit of their office and calling, clothe them with the intelligence of heaven, the light of revelation, and the gift and power of God.[114]

In fulfillment of this prayer, acting as the speaking venue for the Apostles and Prophets eventually became the building’s primary focus. Uniquely, it is one of the few if not the only building in the world that can boast the distinction of having had every prophet of the Church, with the exception of Joseph Smith, occupy its pulpit. Of the significant events held in the Tabernacle, 133 years of general conference rank as among the most important.

Latter-day Saints have used the Tabernacle for hundreds of general conference sessions since the first one held there, in October 1867.

Latter-day Saints have used the Tabernacle for hundreds of general conference sessions since the first one held there, in October 1867.

As mentioned in Grow’s thesis, the first general conference held in the Tabernacle was in October 1867 and lasted four days because Church members voted to extend it an extra day. The location of future conferences rarely changed until the completion of the Church’s conference center in 2000. In fact, only five general conferences, moved out of Salt Lake due to government harassment of Church leaders during the mid 1880’s, were ever convened outside the Tabernacle during the 133 year period.[115] During its time hosting general conference, the building has witnessed significant Church activities, including solemn assemblies to sustain thirteen presidents of the Church, the canonizing of scripture, and announcements of official Church action like the cessation of plural marriage in 1890 and the extension of priesthood access to all worthy males in 1978. Additionally, it has hosted unique general conference experiences, including a special testimony meeting held as the last session of the general conference in October 1942. Held at the height of World War II, the Sacrament was administered during the meeting and those assembled “returned home better able to cope with the dark days ahead.”[116]

Most importantly, powerful testimonies and declarations regarding the gospel of Jesus Christ have resonated within the Tabernacle’s walls. Summarizing these messages, President Stephen L. Richards of the First Presidency remarked,

Ponder for a moment, my brethren and sisters, and all who listen, the glorious and vital truths which have been proclaimed in this building—the nature and composition of the Godhead, the organization of the universe, the history and placement of man in the earth, his purpose in living, and the divine destiny set for him, the laws governing his conduct and his eligibility for exaltation in the celestial presence the true concept of family life in the eternal progression of the race, the truth about liberty and the place of governments in the earth, the correct concept of property, its acquisition and distribution, the sure foundations for peace, brotherhood, and universal justice. All these elemental things, and many others incident thereto, have been the burden of the message of truth which has come from this building through the generations.[117]

Indeed, the building’s primary contribution has been spiritual. Recognizing the import of these messages, President Richards concluded, “I stand today in a pulpit sanctified by its history. When I recall the noble servants of our Heavenly Father who have stood here and given inspired counsel to the people, and borne testimony with such power and conviction and spirit as to electrify every soul who heard; when I contemplate the operation of the still, small voice, which has come from simple and lowly word given here, which have touched the hearts and sympathies of the people; when I think of the vast volume of precious truth which has been proclaimed from this stand, I feel very small and weak within it.”[118]

The Tabernacle as civic center. In addition to being a home for spiritual worship for latter-day saints, the Tabernacle has also served as the center of community life in the intermountain region for more than a century. President Stephen L. Richards noted, “This Tabernacle has been, in some respects, a civic center. It has been a forum for Presidents of the United States, candidates for the Presidency, notables from foreign countries, and lecturers, and for the discussion of some of the most important issues which have ever confronted the nation. It has been used as a gathering hall for great national conventions, and it has played a part in the advancement of important civic causes. It has paid tributes of homage and honor to our national heroes; it has met the demands of emergency; it has been through the years an invaluable asset in our community life.”[119]

President John F. Kennedy at the Tabernacle pulpit during a visit to Salt Lake City, September 26, 1963.

President John F. Kennedy at the Tabernacle pulpit during a visit to Salt Lake City, September 26, 1963.

Tabernacle decorated with garlands for Brigham Young's funeral, 1877.

Tabernacle decorated with garlands for Brigham Young's funeral, 1877.

Though originally reserved for religious services, the Tabernacle soon assumed the role of civic gathering place. “The first recorded mention of a non-religious use of the building was in 1870 when, according to Andrew Jensen’s Church Chronology, ‘discussion commenced in the large Tabernacle . . . between Apostle Orson Pratt and Dr. John P. Newman, chaplain of the U.S. Senate, on the question, ‘Does the Bible Sanction Polygamy?’”[120] Other civic events soon followed.

Prominent visitors to the territory and later the state of Utah seem to have sought out the Tabernacle. Ulysses S. Grant, the first president to visit the territory, toured the historic tabernacle shortly before its dedication in 1875.[121] Other U.S. presidents to visit or speak in the historic structure include Rutherford B. Hayes, Theodore Roosevelt, William H. Taft, Woodrow Wilson, Warren G. Harding, Herbert C. Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson. Of the group, President Hayes was amazed with the building’s acoustics and the fact that he could carry on a conversation with General William T. Sherman from 200 feet away.[122] Presidential candidates, some of which later won election to the office, spoke from its podium, including Dwight D. Eisenhower, William Jennings Bryan, James G. Blaine, Richard M. Nixon, and Barry Goldwater. Other prominent visitors span the breadth of the world and its causes, including General William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army, Sir Arthur Sullivan, Susan B. Anthony, Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil, Queen Liliuokalani of Hawaii, actress Lillie Langtry, Gen. Phillip Sheridan, Actor Edwin Booth, Joseph Smith III, Ferdinand de Lesseps, builder of the Suez Canal, Henry Ward Beecher, Dr. Norman Vincent Peale, and Harvard President Charles William Elliot.

Over the years, numerous other civic events have been held in the building, including “nominating conventions for political offices, a mass protest meeting over the conduct of federal appointees in the territory, a benefit concert for the Johnstown flood victims, the Western Silver Conference, President Wilford Woodruff’s 90th birthday celebration, [and even] . . . a convention of Episcopalians.”[123] Prominent among these civic events have been sacred memorials of national and international import. In 1923, for example, a memorial service was held in the Tabernacle mourning the death of United States’ President Warren G. Harding. Ironically, President Harding had spoken in the Tabernacle on his visit to Utah only six short weeks earlier. More recently, the hall served as a solemn gathering place for the Church following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. As part of the National Day of Prayer and Remembrance, members and Church leaders gathered in the historic Tabernacle to sing, worship, and pray. Following the meeting, Church New editor Gerry Avant observed, “With seeming reluctance, people filed from the Tabernacle that, for the brief span of about an hour, had sheltered them as in a dome of peace and tranquility.”[124]

Finally, in addition to being the home to prophetic addresses in general conference, the Tabernacle has also been the site for many of their final farewells. President Stephen L. Richards remarked, “I wish to say a word about the comfort and solace which have come to our Father’s children in this great building. Funeral services have been held here for many noble men and some women. Heavenly music has been rendered, so inspiring and touching that it seemed as if those from the other world could have joined in the singing. Sermons depicting the transition into immortality, and expounding the atonement and redemption wrought by our Savior, have been given with such convincing assurance as to elevate the aggrieved and despondent to the sublimity of resignation, hope and firm faith. Within these sacred walls have the great of our community found opportunity for the expression of their noblest thoughts and convictions, and from here they have been laid to rest in the closing of their lives.”[125]

One of the earliest funerals in the Tabernacle was held for President Heber C. Kimball on June 24, 1868, just nine months after the building opened.[126] The first funeral for a President of the Church occurred in 1877 when Saints bid farewell to Brigham Young from the historic structure. Since then, funeral services for every President of the Church (with the exception of President Joseph F. Smith, whose service was private because of the 1918 flu epidemic) and numerous other prominent men and women of Mormonism have originated from the Tabernacle. For example, the funeral service was held there for Joseph Standing, a missionary killed by a mob in Georgia in 1879. Later, the structure hosted funeral services for a number of soldiers killed in the Spanish-American war in the Philippines. Memorial services were also held there for three assassinated presidents of the United States—James A. Garfield, William McKinley, and John F. Kennedy.[127]

The Tabernacle as cultural center. While many of the civic events held in the Tabernacle involve prominent visitors and significant historic events, a chief contribution of the building has been its cultural presence in the community. Noting that “the Tabernacle has been a great cultural center,” President Stephen L. Richards summarized,

For eighty years it has housed substantially all of the major concerts, symphonies, bands, choirs, and vocal and instrumental artists who have come to this section of the country. It is safe to say that without it the communities in this area would have been deprived of innumerable opportunities to see and hear the outstanding talent of the world. It has been the scene of great pageants that will long live in our memories; and in addition to being the greatest stage for artistic presentations in our community, it has been a place of instruction and rehearsal for thousands upon thousands of children, young people, and adults, developing talent and artistic appreciation wholly beyond our power to measure. Throughout the years the building has generally been contributed to almost every conceivable cultural project which has come our way.[128]

As the artistic and cultural center of Utah, the Tabernacle has served the community well.

Historically, the hall has also been used for a variety of educational and cultural purposes. “In its early days, the Tabernacle was the scene of many lectures that today are more commonly held on local college campuses. Madame Mountford, a native of Jerusalem, attracted audiences for three consecutive nights in 1897 with her lectures on village life in Palestine, the Bedouins of the desert, and the life of Jacob. The same year Senator Frank J. Church lectured on ‘The Manners and Customs of the Japanese and Chinese.’”[129] Similar presentations continued in the Tabernacle until other speaking venues were built throughout the valley.

Early Church leaders who sponsored the construction of the Tabernacle felt strongly about the value of cultural enrichment. “As the pioneers struggled for survival in Utah, the arts were championed by Brigham Young, who understood how music and drama could break the monotony of privation and physical labor. ‘Tight-laced religious professors of the present generation have a horror at the sound of a fiddle,’ he declared, probably remembering his puritanical upbringing. ‘There is no music in hell, for all good music belongs to heaven.’”[130] With this philosophical background, the Tabernacle has been a home to the arts in Utah.

Though music was valued by Church leaders, introducing sectarian singing into the Tabernacle took special arrangements. The first such concert held in the historic structure was by world-famous operatic soprano Adeline Patti in February 1884. Not only the first concert, it was also the first ever held at night and in the winter. Gas lamps were brought in, together with pot-bellied stoves to illuminate and warm the building. For her part, Patti had a special rail line built, taking her car directly to the Tabernacle itself.[131] All of this was over the objections of some members of the Twelve, who apparently disapproved of such sectarian uses for the building. However, by one account, Madame Patti won President John Taylor over to the idea by praising the magnificent Tabernacle and expressing “a strong desire that she might be allowed to try her voice there.” Apparently, her appeal included “enthusiastic praise of the Mormon doctrines, and, in fact, . . . a strong wish to join the Mormon Church.”[132] The concert was a success, with over 14,000 people present.

Since the first concert, musicians have made the Salt Lake Tabernacle a regular stop on their North American tours. The building has hosted some of the most famous musicians of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including Polish pianist Paderewski, Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff, Austrian violinist Fritz Kreisler, and, more recently, American vocalists Frederica von Stade and Gladys Knight.[133] Of these and other visitors, Deseret News music editor Harold Lundstrom observed on the occasion of the Tabernacle’s centennial, “At least a dozen of the world’s great artists (who, for obvious reasons must go unnamed here) have told me that the principal reason for their accepting a concert date in Utah was so that they could include in their concert credits a ‘performance in the Salt Lake Mormon Tabernacle.’ At least four of them have said that a performance in the Tabernacle carried the prestige second only to Carnegie Hall.”[134] Like soloists, famed performing groups have also sought out the hall as a venue. Over the years, the Tabernacle has hosted the New York Philharmonic, the Pittsburgh Symphony, the Chicago Symphony, the Berlin Philharmonic, and the Vienna Philharmonic. Additionally, before the completion of Salt Lake’s Abravanel Hall, the Tabernacle was home to the Utah Symphony Orchestra for over thirty years.[135]

While national and international musical talent has regularly performed in the building, the Tabernacle has also sponsored its own significant special musical events. One early event was a Welsh singing festival, the great Eisteddfod, held in the building in conjunction with the October 1895 general conference of the Church. By one account, this musical extravaganza “exceeded in scope and attendance any musical and literary event of its kind ever held in the United States, with the exception of the Eisteddfod held during the World’s Fair in Chicago [of 1893].”[136]

In addition to these non-LDS cultural events, the Tabernacle also played host to significant Church productions. During the twentieth century, for example, the Church frequently used the hall for various historical commemorations. In honor of the centennial of the Church in 1930, members participated in a pageant entitled “The Message of the Ages,” held in the building throughout the month of April. Emphasizing the restoration of the gospel, it presented a chronologically summary of the history of God’s work on earth. One observer commented that this was “probably one of the most outstanding events ever held in the Tabernacle.”[137] Seventeen years later, in 1947, a similar production was held to commemorate the arrival of the pioneers in Utah and the Church’s reaching a milestone of one million members worldwide. More recently, the Tabernacle was used in Salt Lake’s celebration of the 2002 Winter Olympics and Paralympics, hosting concerts with the Tabernacle Choir and world-renowned artists throughout the celebration of the games.

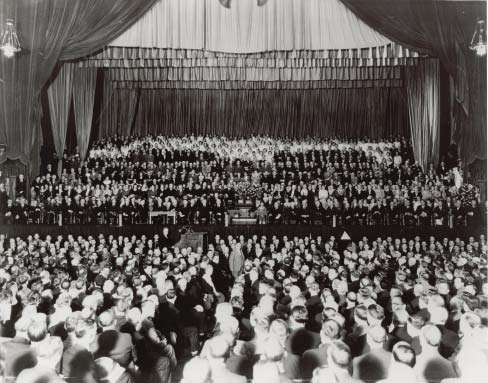

Audience, General Authorities, and cast of The Message of the Ages pageant celebrating the centennial of the Church, April 1930. The organ is covered by layers of curtains hung for the occasion.

Audience, General Authorities, and cast of The Message of the Ages pageant celebrating the centennial of the Church, April 1930. The organ is covered by layers of curtains hung for the occasion.

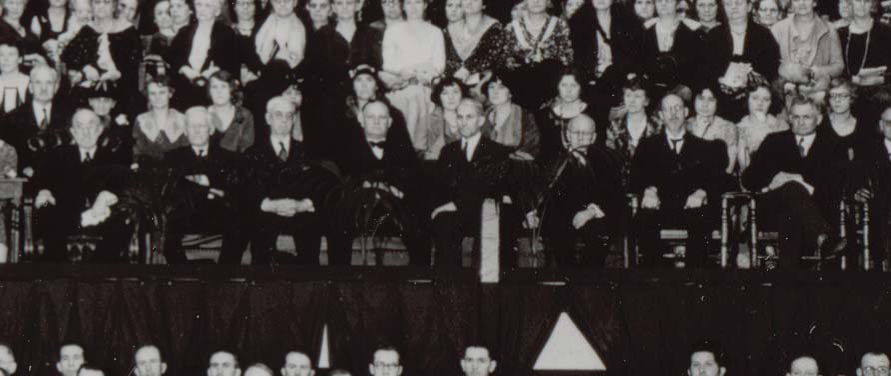

This detail of the pageant photo shows then-President Heber J. Grant and future presidents George Albert Smith and David O. McKay seated with other General Authorities on the stand in the front row.

This detail of the pageant photo shows then-President Heber J. Grant and future presidents George Albert Smith and David O. McKay seated with other General Authorities on the stand in the front row.

Conclusion

The Tabernacle has stood as a silent witness to significant events in Church and world history for the past 140 years. When first opened in 1867, it was the primary meeting place for a Church with a membership of approximately 100,000 located in only four stakes (Salt Lake, Weber, Utah, and Parowan) and 10 organized missions.[138] A sixty-six year old Brigham Young presided over the first general conference in the building, an occasion at which the Church sustained twenty-eight year old Joseph F. Smith as the newest member of the Quorum of the Twelve. Now 140 years, thirteen Church presidents, and nearly thirteen million members later, the building still stands as a solid reminder of the faith, ingenuity, and vision of its pioneer builders. Remembering the early saints’ accomplishments, President Gordon B. Hinckley observed,