Discussions

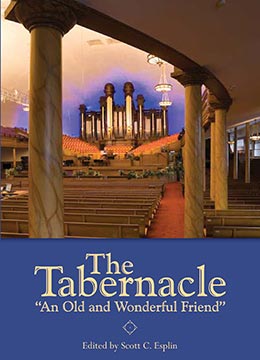

Scott C. Esplin, “Discussions,” in The Tabernacle: “An Old and Wonderful Friend” (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2007), 217–39.

There are several items concerning the Salt Lake Tabernacle that are not of historical record. As a result, a great deal of conjecture has grown up concerning them, as well as some misinformation. It is the purpose of this chapter to present some of the information available concerning these questions and to draw some conclusions therefrom.

Acoustics of the Tabernacle

Annually thousands of tourists are guided through the Tabernacle. During their tour, they are given a demonstration of some of its acoustical properties. Attendants drop a pin on a wooden rail, rub their hands, and whisper toward and away from the visitors who are seated near the rear of the building, nearly two hundred feet away. All of the demonstrations can be heard distinctly. The result is that the Tabernacle has a reputation of being one of the most acoustically perfect buildings in the world. In the light of this, it is interesting to return to the history of the building at the time of its construction to find the reaction to its acoustical properties at that time.

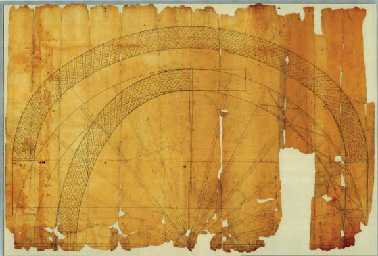

Sketches of the proposed roof structure, from various angles. Folsom's name is written in the top left corner of this recently acquired image.

Sketches of the proposed roof structure, from various angles. Folsom's name is written in the top left corner of this recently acquired image.

Acoustics were a priority in the Tabernacle's design. The domed roof and gallery created an ideal sounding board for both speakers and performers to be heard by large audiences in an era before amplification.

Acoustics were a priority in the Tabernacle's design. The domed roof and gallery created an ideal sounding board for both speakers and performers to be heard by large audiences in an era before amplification.

For four years prior to the completion of the Tabernacle, the Saints had been obliged to hold all of their large meetings outdoors in boweries. Under these circumstances the audience had great difficulty in hearing the speaker. This was especially true if there was any wind or other outside noise. So it was a matter of prime concern that the audience be able to hear. This concern was expressed in an article in the October 2, 1867, issue of the Salt Lake Daily Telegraph: “How It Will Sound.—Everybody has something to say about the new Tabernacle, and ‘will the speaker be heard?’ is not unfrequently asked. On Sunday that question will be solved. The general expectation is that it will be an easy building to speak in. Without the audience, no reliable experiment can be made; but the probabilities are all favorable. On Monday evening, the choir practice could be heard very distinctly about two blocks distant. It is a great edifice.”[1]

The people’s concern about the acoustical properties of the building was shared by Brigham Young. Mr. Stenhouse, in reporting on the first conference in the Tabernacle, wrote: “Preceding the services, President Young spoke to different persons in various parts of the building, endeavoring to ascertain how the speaker could be heard. The results did not then seem to be the most satisfactory, but as every attention is given to this subject, we reserve observations thereon till we obtain something that may be serviceable.”[2]

The observations made by Mr. Stenhouse about the acoustics of the Tabernacle were common to others. Truman O. Angell, who designed the interior of the Tabernacle, wrote in his journal:

Sunday, [October 6, 1867.] I arose very early and walked down to the city and went to conference in the morning. The bustle and noise made by the people destroyed the words of the speaker or drowned them. I moved about in several places, the same noise seemed all through the house. It was about the same in the afternoon. I thought of the subject and worried over it, but I made up my mind—if the people would be very still, all might hear.

Monday 7th. In the morning I seated on the last row on the east of the new seats. The President said if the people would be very still he thought all could hear very well and this proved true to me for I heard well. In the afternoon I went on the stage. I entered the south door, but I did not hear much. It would of been much better if the people would come in at the right hour and be seated and keep seated and stop whispering and keep their feet still.

Charles Smith, a resident of St. George and pioneer leader of the southern Utah area, was in Salt Lake City for the first conference held in the Tabernacle in October of 1867. He reports the event in his journal: “October 6, 1867. Conference was opened in the new Tabernacle by President Brigham Young. This Tabernacle will seat eight or ten thousand people. I took a seat in the body of the building, but could not hear very well, so in the afternoon I went further up where I could hear better.”[3]

In reporting the opening of the Monday morning session of the conference, Mr. Stenhouse observed:

The severe rain storm during the preceding night told upon the audience this morning. The Tabernacle was probably not more than three parts occupied. The noticeable portions of the absent were the very young, and the quiet of the audience was much improved. It seemed from this and also from the change in the weather that the speakers were better heard throughout the entire building. It will probably be our experience yet, that when the audience is as still as it always should be, it will require very little if any change to make it a very easy place to speak in, especially after the speakers have themselves become familiar with the building and the government of their voices to the situation of the audience.[4]

No doubt further research into this question would reveal comments by many others to the effect that the acoustics of the Tabernacle left much to be desired.

Some years after Mr. Stenhouse had attended the opening of conference in the Tabernacle, he became disaffected with the Church and eventually grew quite bitter toward it. He ceased publication of the Telegraph and moved to San Francisco, where he wrote for some of the leading newspapers of the day. He also wrote a bitterly anti-Mormon book entitled The Rocky Mountain Saints. An excerpt from this book is interesting:

The first object—after Brigham—that every visitor should see is the new Tabernacle. It is the most uncomely edifice that was ever erected for a place of worship, but it holds a great many persons—twelve thousand. As seen from a distance, it looks like a huge turtle. . . . It is oval in shape, and without a column to obstruct the vision; but, in compensation for that advantage, as “the Lord” had everything to do with its construction, an utter disregard for what Gentile experience could have suggested might have been expected, and the massive building grew up and was finished free from every taint of the science of acoustics. When it was dedicated and opened for preaching, not one-third of the audience could hear any speaker distinctly, and the rest of the auditory heard only a rumbling noise, and were left to guess the subject from the gestures of the preacher. Of course, the ungodly considered those who heard the least were the most favoured! . . .

When the Tabernacle was nearly finished, and much glory was anticipated, there were a number of claimants for honour. Brother Grow, brother Angel, and brother Folsom, wanted each the major share of glory, if Brigham should leave any for distribution: but, when the building was found to be a magnificent failure, even the apostle, Orson Hyde, hesitated to credit it to “the Lord.” After many weeks of hard labour, and endeavouring to arrive at some conclusion, Brigham finally discovered that there was “no echo in the building—the voice only reverberated!”[5]

While the excerpt from Stenhouse’s book may present an exaggerated picture, it is evidence as to the inadequacy of the acoustics of the Tabernacle in its early stages. Mr. Stenhouse had been present at the opening of the building and at many meetings thereafter. At that time he had noted the acoustical deficiencies. Therefore, his later opinion, though exaggerated, is to a degree valid.

The poor acoustics of the Tabernacle was the occasion for many speakers throughout the early years of the Tabernacle to request the cooperation of the audience in keeping quiet so the speaker’s voice might be heard.

The first great improvement in the acoustics of the Tabernacle was made by the addition of the gallery in 1875. This change in the interior of the Tabernacle effectively reduced the reverberation and echo. But even with this improvement, there were many places in the Tabernacle where it was exceedingly hard to hear the speaker.

An excellent study on the acoustics of the Tabernacle has been done by Dr. Wayne B. Hales. He has found that many places in the Tabernacle, even with the gallery in place, have considerable reverberation. This reverberation is fine for a musical program but is poor for a speaker. The conclusions of Dr. Hale’s study are interesting:

1. Hearing is obviously best immediately in front of the speaker. It slowly decreases as one recedes down the center aisle and then rises again near the rear.

2. Hearing is poorest under the balcony and east of the north aisle.

3. Hearing is better on the whole in the balcony than under the balcony.

4. Good hearing is fundamentally dependent on loudness of voice increasing from 39 per cent for normal voice to 59 per cent for voice 3 x normal and to 80 per cent for the amplified voice. . . .

For reverberation [a] good compromise seems to have been well met in the construction of the Salt Lake Tabernacle. When an audience fills this auditorium the reverberation is a little more than a second, a period which is about right to produce the best effects on a listener when the entertainment is musical, and which is a little too long for ideal conditions when the entertainment is an address. It is indeed remarkable for an auditorium of this volume to have a reverberation of less than 5 seconds when the building is empty and about one second when filled with an audience.

The interference by successive reflections which was noted in certain sections of the tabernacle could be greatly reduced by placing some efficient absorbing material on the walls. This would lessen to a great extent the intensity of reflected waves. But since an auditor in the rear of the building (and in the balcony) is so dependent on these reflected waves for good hearing, it is doubtful that anything could be gained.[6]

The problem of making everyone hear in the Tabernacle was solved with the advent of efficient amplification system. The Tabernacle has now installed one, and the speaker’s voice is clearly audible in all parts of the building.

Source of the Idea for the Shape of the Tabernacle

The general design of the Tabernacle was Brigham Young’s idea. This is generally agreed in the writings of the day and is indicated by Henry Grow, who superintended the erection of the Tabernacle. However, none of the articles or journals make any reference to the source of the idea for its unique shape. No doubt there were many inquiries and conjectures at the time of its construction. With the passing of time, the conjectures grew in number, and four major stories have been handed down. The author’s research has found nothing which would give credence to any of them. However, they are repeated as a matter of interest.

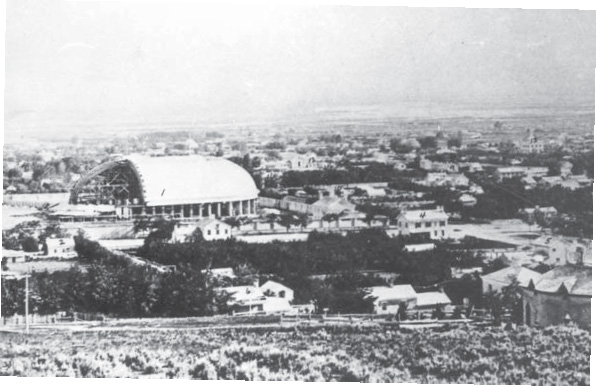

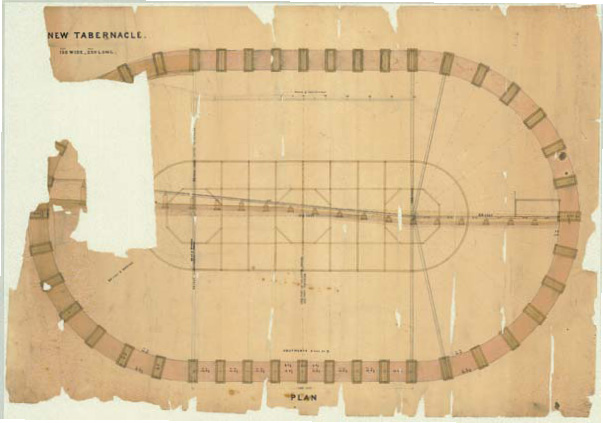

The Tabernacle as seen from Arsenal Hill (now Capitol Hill). Various sources have been suggested for the shape of the Tabernacle roof, from egg shells to the human mouth, but none have been historically confirmed.

The Tabernacle as seen from Arsenal Hill (now Capitol Hill). Various sources have been suggested for the shape of the Tabernacle roof, from egg shells to the human mouth, but none have been historically confirmed.

The first story, and probably the most widely told, relates that Brigham Young had, on occasions at breakfast, been impressed with the strength of the half of an eggshell after the boiled egg had been removed. The principle of the arched roof, therefore, developed in his mind. One day, so the story goes, he took along a boiled egg to one of his meetings and, placing it on the table in front of him, cracked it the long way, a little off center. Hollowing out the large portion he placed it upon the table and remarked, “I want a building shaped like that.”

It is easy to see how such a story could have developed, whether or not founded in fact. The general egg shape of the Tabernacle could easily have given rise to the idea and, having first been related as conjecture, later became tradition. In all the writings on the Tabernacle, none of them refer to its egg shape nor the fact that its idea came from the source indicated.

The second story is to the effect that Brigham Young met Henry Grow on the street one cloudy day and, raising up his umbrella, told Mr. Grow that he wanted the Tabernacle built in the shape of his umbrella. This story has been related to members of the author’s family by persons who were well acquainted with the Henry Grow family. The idea has been printed in several articles on the Tabernacle. One of these appeared in the Salt Lake Tribune, Sunday morning, November 14, 1915, in an article entitled “Out of the Desert a Tabernacle Arose”: “The roof of the tabernacle is a marvel of construction, especially so in view of the period at which it took form. . . . It stands a monument to William H. Folsom and Henry Grow and the army of good fellows who sawed and hammered and lifted and strained their faithful arms and backs until the thing was moulded into the shape that Brigham Young suggested when he opened his umbrella and said he wanted a roof ‘just like that.’”[7]

Again, none of the references searched by the author made any reference to the raised umbrella idea. The roof was likened to the back of a huge eastern turtle or to the hull of a ship turned upside down, but never to an umbrella or an egg.

The egg and umbrella stories are the most widely circulated. However, in the course of interviewing various people concerning the Tabernacle, two additional stories were related to the author which merit repeating here.

The first of these two comes from Preston Nibley, a widely read author on Mormon subjects. He reports that one day he was talking with Susa Young Gates, a daughter of Brigham Young, and she said to him, “Preston, do you want to know where my father got the idea for the shape of the Tabernacle?” Mr. Nibley indicated his interest, and Mrs. Gates continued: “Well, he got it from the small elliptical portion on the back of the old Tabernacle.” A reference by the reader to the picture of the Old Tabernacle on page ____ will reveal the rounding protrusion at the rear of the building. It is designed much like the band shells and orchestra stands in many parks and dance halls. According to the rest of the story, Brigham Young reasoned that if such a segment was so suitable for music and sound reflection, why could the principle not be extended into an entire building? And so the idea for the shape of the Tabernacle was born. However, this story, like the others, has no evidence to support it.

The last story was told the author by William H. Lund, assistant Church historian. He recounts that one day a friend asked Brigham where he got the idea for the Tabernacle, and Brigham Young replied, “From the best sounding board in the world, the roof on my mouth.” This story could have well developed after the Tabernacle became famous for its acoustical properties. The teeth could compare with the piers of the Tabernacle, and the roof of the mouth with the arched roof of the building. However, there is no evidence to support this idea.

It is unfortunate that none of the records of the day indicate the true source of the idea, if there was one such source. Each of the stories sounds possible, and each could have had an influence, but it seems that none of them would represent the whole story even if they were founded in fact. Brigham and his assistants must have been tired of posts. The first Bowery on the Temple Block was supported with posts. The second Bowery used about one hundred posts to sustain the roof, and the Bowery to the north of the Old Tabernacle had about one hundred fifty posts in it. These posts made it difficult for seeing and speaking to the audience. The Old Tabernacle was built without any obstruction in the main portion of the auditorium. This must have been a great relief from preaching to so many posts, and when the construction of the new Tabernacle was under consideration, it would seem very normal for President Young to say, “I want a building without any posts in it.” This is the phrase which Brigham Young used in telling Henry Grow of his desires in connection with the building.[8] According to the tradition in the Grow family, President Young was also interested in the application of the lattice arch to the roof. The outgrowth was the shape of the Tabernacle.

Whether the idea came from an egg, an umbrella, the Old Tabernacle, the roof of Brigham Young’s mouth, or the desire to get away from posts and the application of the lattice-arch principle, the fact remains that at the time of its construction the architecture was unique.

Who Was the Architect of the Tabernacle?

Gordon B. Hinckley, as publicity official for the Church, indicated that, in his experience with publicity on the point, a compromise had been reached in which it was indicated that Henry Grow and William Folsom cooperated on the design under the general instruction of Brigham Young. He added that so far as he knew there was no historical basis for the compromise but that it had been arrived at as a result of family pressure and the lack of historical proof to the contrary.[9]

It is generally accepted that Brigham Young indicated to the builders of the Tabernacle the building’s general plan. This probably included something as to the shape he desired and the fact that it was to be free from posts.

From his journal entries, it is evident that Truman O. Angell designed the interior of the building, including the stand, seating arrangement, doorways, stairways, and other finishing details.

The question remains, then, who designed the Tabernacle? There are three persons who are given credit for the design: Henry Grow, William Folsom, and Truman O. Angell. The author has found no material which will make the claim of any of the men incontrovertible.

There are two major factors which give credence to the claim of Mr. Folsom. First, he was the Church architect at the time of the commencement of the Tabernacle. In such a position it would be rational to assume that he would design the Tabernacle. Second, there was printed on June 3, 1863, in the Deseret News, an article which outlined the general plan for the Tabernacle and gave Mr. Folsom credit for being the architect.[10] These two items taken at face value seem to present good evidence to support the claim that Mr. Folsom designed the building. However, a closer analysis of the fact, in light of later developments, reveals several sources of doubt as to his authorship of the final design.

Mr. Folsom became architect for the Church in 1861, two years before the Tabernacle was started. He was replaced by Mr. Angell in April 1867, just at the time the big drive started for the completion of the Tabernacle. At that time, the interior of the building had not been designed and the exterior was far from completion. Whether Mr. Folsom had taken any interest in the building of the Tabernacle prior to his being replaced is not sure, but after he was replaced by Mr. Angell there is definite evidence that he was not connected with the completion of the Tabernacle. It hardly seems likely that if he were the architect of the building—supervising its erection, as architects do—he would leave the work right at its most crucial stage.

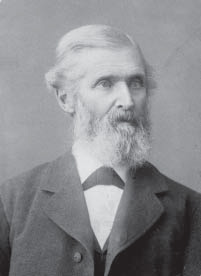

William Folsom

William Folsom

Truman Angell

Truman Angell

Henry Grow

Henry Grow

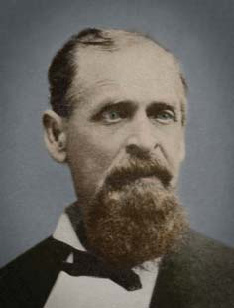

Early concept drawing for the Tabernacle, possibly by William Folsom. This document was recently acquired by Church archivists. In this design, the roof differs significantly from the present structure. Note the stone piers and oval shape, which were included in the final design.

Early concept drawing for the Tabernacle, possibly by William Folsom. This document was recently acquired by Church archivists. In this design, the roof differs significantly from the present structure. Note the stone piers and oval shape, which were included in the final design.

In connection, Mr. Angell has several revealing entries in his journal:

[May 4, 1867.] On my going to the house, I saw Br. Sharp. He wants a plan and a bill of timbers for the flume that will cross Big Cottonwood. He asked me if Folsom had given me the said plan. I said no. I saw Folsom still on my way; I invited him to call at or near my office Monday morning.

[May 6, 1867.] I went soon after to Folsom, and in a little time we saw J. Sharp, and I decided for Folsom to furnish said bills as he knew more about it that I did.

[May 10, 1867.] Brother Folsom made a diagram of the flume to cross Big Cottonwood, and bills also. He called me into his office to see it. I showed him it needed a brace to help stay against water more secure under the toepath. He saw it and added one in. I thought and told him it seemed to me better to raise the toepath 10 or 12 inches above the water on top of flume, but he did not see it, so it rested there.

[July 8, 1867.] Came into my office early and cleaned it out and commenced work getting ready to have the new tabernacle go on in order and dispatch as far as my branch need dictate the work. The best of the joiners are drawn off after Folsom & George,[11] and jobbing on the street. They instruct the men, I am informed, to not come here. A few, or one or 2, has come here. They are the old veterans that are much broken down.[12]

It hardly seems likely that Mr. Folsom would be spending the time drawing plans for a flume to cross Big Cottonwood Canyon at the time the Tabernacle was so in need of additional planning and supervision. Also it is significant that Mr. Angell invited Mr. Folsom to “call at or near [his] office.” Had Mr. Folsom been on the Temple Block overseeing the Tabernacle, he would have been right at Mr. Angell’s office and the work could have been done there without the necessity of an invitation.

The entry of July 8 is most significant in this study. Had Mr. Folsom been primarily interested in completing the Tabernacle, it is not at all likely that he would have permitted his company to recruit labor from the ranks of those who were laboring on the Tabernacle. The above items would indicate that although Mr. Folsom had been Church architect, his prime interest during 1867 was not the completion of the Tabernacle.

Consideration of the original plans published under Mr. Folsom’s name will also be helpful. The full article can be found on page ___, but excerpts from the plans will suffice: “The sides of the building outside will be 45 ft. high from floor level to eves of cornice. Roof, quarter pitch, with attic in centre, 50 ft. wide by 150 ft. long, on which will stand three octagon domes or ventilators. The arches will be formed with lattice work 9 ft. deep in the smallest part, with an increase in the centre and outer end.”[13]

Comparing those plans with the finished roof of the Tabernacle, one will find considerable discrepancy. First, the building is much less than forty-five feet to the cornice, and there are no eves in the conventional sense. Secondly, the roof is not quarter pitch but rather a circular roof. The quarter-pitch roof is descriptive of an ordinary straight roof. The finished roof of the Tabernacle can hardly be described as quarter pitch. The original plan also called for an attic 30 feet wide and 150 feet long. In the finished roof, there is no attic of the measurements indicated. These differences between the original sketch of the plans of the Tabernacle and the finished building indicate that the roof was redesigned following the issuance of the original specifications. This may have been one of the reasons for the long delay between the start of the building in 1863 and the start of the roof construction in September 1865.

Another factor that makes doubtful the proposition that Mr. Folsom was the architect, is that other than the mention of the Deseret News of 1865, none of the newspapers of the day give him credit for being its architect. This is also true of the early histories. It is not until later writings that his name is mentioned as architect of the Tabernacle. So far as the author has been able to determine, Mr. Folsom never claimed to be the architect of the Tabernacle.

The consideration of the proposition that Mr. Grow was the architect, as well as the builder of the Tabernacle, finds the following factors in its favor:

First, Mr. Grow claimed throughout his life to be the designer of the Tabernacle. On the back of his business card the following is found: “Large Tabernacle—Was completed October, 1867, shape was designed by President Brigham Young. The architect that planned this building was Henry Grow.”[14] The full text of Mr. Grow’s business card can be found on page _____.

Second, the writers at the time of the building of the Tabernacle gave Mr. Grow credit for its design. So did the contemporary historians. The Deseret Evening News wrote:

One of the most prominent and best known of pioneer builders, and especially remembered for the planning and construction of the tabernacle in this city, Henry Grow came to Utah in 1851. . . . In 1853 he built the first suspension bridge in Utah, across the Ogden river. Afterwards, during a long and busy life, the following important works may be placed to his credit: the old factory from which Sugar House ward takes its name, sawmills A, B, D, and E, in Cottonwood canyon, a sawmill seven miles up City Creek, woolen mill at the mouth of Parley’s canyon, suspension bridges over the Provo, Jordan and Weber, various mills for Prest. Young, the original ZCMI building, Assembly Hall, paper mill on Cottonwood, and, most enduring and conspicuous of all, the large tabernacle.[15]

Tullidge’s History of Salt Lake City, published in 1886, contained the biographies of many of the men who had contributed to the building of Salt Lake City. In the biography of Henry Grow, the following is published: “In 1865, the President called on him in regard to the construction of the Big Tabernacle. He designed the shape, planned, framed, put up and finished this Tabernacle in the fall of 1867. In 1868 the President called on him to put up the Z. C. M. I. building.”[16]

Whitney’s History of Utah, published in 1893, states: “In October, 1867, was completed,—so far at least as to enable the general conference held that month to convene beneath its ample roof,—the famous Mormon Tabernacle at Salt Lake City. . . . The architect of the Tabernacle, under Brigham Young, was Henry Grow, who also had charge of its construction.”[17]

This historical reference is good evidence, the author believes, to support the proposition that Henry Grow was the architect of the Tabernacle. This proposition is further supported by statements from Henry Grow’s sons. Otto Grow lives in Salt Lake City and was personally interviewed by the author. George Grow lives in Pasadena, California, and was interviewed by correspondence. Otto Grow states that he has heard the stories of the building of the Tabernacle many times in his home and that so long as his father and mother lived there was never any question that Henry Grow was the architect. One of the most vivid incidents he recalls hearing was that when Henry Grow was constructing the roof of the Tabernacle, Mr. Folsom would walk around and express his lack of confidence in the design by such comments as, “When the props are taken out, it will fall and probably kill us all.” This sniping so irritated Mr. Grow that he asked President Young to ask Mr. Folsom to stay away from the Temple Block.

If the story is true, the remark in Mr. Angell’s diary that he requested Mr. Folsom to “call at or near [his] office” has additional significance. This may also account for the recruiting of workers from the Tabernacle crew by the firm of Folsom and George.

It is the author’s judgment that Henry Grow was the architect of the Tabernacle roof and exterior and that Truman O. Angell was architect of the Tabernacle interior. Mr. Angell is seldom given any credit for work on the Tabernacle. It is hoped that this book may be the means of giving him some of the credit which is justly due.

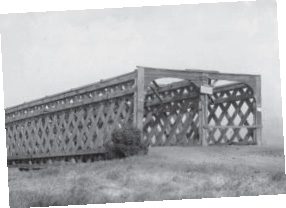

This bridge spanning the Jordan River was built by Henry Grow in 1860 using the Remington patent lattice work.

This bridge spanning the Jordan River was built by Henry Grow in 1860 using the Remington patent lattice work.

Henry Grow used the Remington patent lattice work in his design of the Tabernacle to support the roof without any interior columns.

Henry Grow used the Remington patent lattice work in his design of the Tabernacle to support the roof without any interior columns.

Were Any Plans Drawn for the Tabernacle?

For many years, guides on the Temple Block in Salt Lake City would remark that the main portion of the Tabernacle was built without plans. The guides no longer make such comments because in the light of modern requirements for architectural details and the absence of proof, the idea of building such a structure as the Tabernacle without detailed plans seems fantastic. The general position taken by Church authorities is that such a building as the Tabernacle must have been well planned in advance of its construction. To support such a position, they point out that other Church buildings which preceded the Tabernacle were planned in advance, and therefore there is no reason to suppose that the Tabernacle was an exception to the rule.[18] However, so far as the author could determine, there are no copies of plans for the exterior of the Tabernacle available, nor are there any records which prove that architectural plans were drawn for it. The nearest thing to proving that such plans were drawn is contained in the general prospectus of the building published in the Deseret News of 1865. But as has already been shown, those plans were not the plans by which the Tabernacle was built.

In support of the theory that no architectural plans were drawn, the author found the following item published in the Pasadena Post:

So in Pasadena, we have many, many interesting personages. Yesterday I discovered the son of the man who built the Great Mormon Tabernacle in Salt Lake City. He is a carpenter here, George Grow, lives at 1330 North Raymond Avenue, and has heard from the lips of his father, Henry Grow, who passed away in 1891, many of the details of the planning and construction of that great building.

It has always been said that Brigham Young designed the building, which when completed was the largest hall in the world unsupported by columns. Strange as it may seem, there never were any plans made for this building. According to George Grow, Brigham Young told Henry Grow what he desired. He wanted a huge Tabernacle and he didn’t want any posts in it. He wanted the roof to cover it without any supporting arches.

“Can you do it?” asked Brigham Young. Henry Grow, who had built a number of bridges in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, using the Remington Patent of Lattice bridges, stated that he could, and together he and Brigham Young drew roughly a sketch of what the building should look like. Then Henry Grow started out to erect the structure. He had no plans whatever. They were all in his head.

So through the son, George Grow, we learn this somewhat marvelous fact.[19]

In order to verify the article in the Pasadena Post, the author wrote to George Grow. His reply is reproduced in the appendix and contains the following statement: “There were no plans drawn. Henry Grow built it by details which he drew as he went along.”[20]

Otto Grow also supports his brother’s statement. He recounts how his father paced the floor at night for two weeks trying to develop a system of attaching the end arches to the center arches. If a detailed plan had been drawn in advance, such worry during the course of the construction would seem to be unnecessary.

An excerpt from Truman O. Angell’s diary is also indicative that no detailed plan for the building was drawn in advance: “I got along with penciling on the drawing of Tabernacle seating and flooring arrangement. There are some difficulties not overcome. It will be best to let the President choose what may suit him in the affair. In the morning I will level and leave marks to cite his mind to. If I had charge of this building from the start it would have been my way to of found all the main troubles in a plan ahead of the work, but now it is otherways and I will do the best I can.”[21]

Mr. Angell’s diary entry would plainly seem to show the lack of an overall plan. It is realized that the above evidence is not conclusive but nonetheless gives support to the story that the building was completed without a formal detailed plan.

Notes

[1] “How It Will Sound,” Salt Lake Daily Telegraph, October 2, 1867.

[2] “The Thirty-seventh Semi-annual Conference,” Salt Lake Daily Telegraph, October 8, 1867.

[3] Charles Smith, personal journal.

[4] “The Thirty-seventh Semi-annual Conference,” Salt Lake Daily Telegraph, October 9, 1867.

[5] Thomas B. H. Stenhouse, The Rocky Mountain Saints (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1873), 693–95.

[6] Wayne B. Hales, “Acoustics of the Salt Lake Tabernacle,” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America (January 1930), 1:291–92; includes further technical information on the Tabernacle’s acoustics.

[7] “Out of the Desert a Tabernacle Arose,” Salt Lake Tribune, November 14, 1915, 10.

[8] Otto Grow, a son of Henry Grow, related the story.

[9] Gordon B. Hinckley, conversation with author.

[10] See “The New Tabernacle,” Deseret News, June 3, 1863.

[11] Folsom and George were construction partners.

[12] Angell Journal, May 4, 6, 10, July 8, 1867.

[13] “The New Tabernacle,” Deseret News, June 3, 1863, 3.

[14] “Out of the Desert a Tabernacle Arose,” Salt Lake Tribune, November 14, 1915, 10.

[15] “Our Gallery of Pioneers: Henry Grow,” Deseret Evening News, September 11, 1915, 2.

[16] Edward W. Tullidge, “Biographies,” History of Salt Lake City, (Salt Lake City: Star, 1886), Biographies, 128.

[17] Orson F. Whitney, History of Utah (Salt Lake City: George Q. Cannon and Sons, 1893), 2:179–80.

[18] This view was expressed to the author by a representative of the Presiding Bishop’s Office, which supervises the construction of buildings, also by David A. Smith president of the Temple Square Mission.

[19] F. F. Runyon, “Our City, Comment and Discussion,” Pasadena Post, August 25, 1931.

[20] Letter from George Grow to author, June 2, 1947.

[21] Angell Journal, June 19, 1867.