‘Olelo: Women of Faith Speak

Debbie Hippoliteatuai Wright, Rosalind Meno Ram, Kathleen L. Ward, Rowena L. K. Davis, Jessika Lawyeratulai Tora, and Seini Mu'amoholeva

Debbie Hippoliteatulai Wright, Rosalind Meno Ram, and Kathleen L. Ward with Rowena L. K. Davis, Jessika Lawyeratulai Tora, and Seini Mu‘amoholeva, “‘Olelo: Women of Faith Speak,” in Pioneers in the Pacific, ed. Grant Underwood (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005), 69–80.

Debbie Hippolite Wright, a Maori from Aotearoa, was a professor of social work with a particular interest in Pacific Island women, families, and communities when this was published.

Rosalind Meno Ram was a librarian at the Joseph F. Smith Library with great interest in the Pacific Islands and most especially the women of the Pacific when this was published.

Kathleen L. Ward was a professor of international cultural studies with an emphasis in women’s studies and Black American culture when this was published.

Rowena L. K. Davis was an adjunct faculty member of social work at Brigham Young University–Hawai’i when this was published.

Seini Mu‘amoholeva and Jessika Lawyeratulai Tora were also members of this project collecting Pacific Island women’s oral histories.

The Latter-day Saint women you are about to meet from the islands of the Pacific are as varied and distinct as are their island homes. Their stories were recorded as part of a larger women’s oral history project funded by Brigham Young University– Hawai’i. While these women are widely diverse in background, experience, and age, they share in common religious convictions and the ability to align testimony with strong cultural identities. As will be evident, their journeys have not always been smooth; yet whatever waters may be stirred at the meeting of religion and culture, Pacific Island women are adept navigators, steering confidently into the merged currents of ancestral teaching and gospel principles. We found these women neither oblivious to nor snared by the surface trappings of religion and culture, and their stories aptly focus on the myriad satisfactions and struggles of daily living, with eyes ever focused on the enduring things.

The Enduring Things

Just what is enduring to Pacific Island women? What are the constants that shape their lives and values? We had not traveled far nor talked to many before several answers began to emerge:

Pacific Island women are spiritually grounded, at ease with Deity and the natural world.

Pacific Island women work, work, work. As one said, “Work is our theme song!”

Pacific Island women are dedicated mothers and “othermothers,” sharing with each other the responsibilities of nurturing children.

Pacific Island women are active and articulate about the preservation of their cultures.

While this list does not capture the full range of individual experience, it underscores four central themes weaving in and out of the narratives, signaling what is important and enduring in the lives of today’s Pacific Island women.

The Project

It is fitting here to provide a context for the stories you will read, indeed, to first tell another story—that of the “In Her Own Voice” project and those of us immersed in it. Our initial objectives were both basic and challenging: first, to provide a venue for a variety of Pacific Island women at different stages in life and with varied experiences to talk about their lives and to give us an opportunity to listen and learn from them; second, to re-create the experience of listening and learning firsthand for our readers, who include the women themselves and our university students. In close association with these primary objectives was a determination to replace absence with presence and to fill a void that has both rightly and wrongly suggested women’s secondary status in the Pacific. In truth, it was the absence of recorded material on contemporary island women that initially fueled our interest and embarked us on the project. Bringing women’s voices into the larger conversation of the Pacific was our goal.

More problematic than the question of objectives was deciding exactly what would happen with the narratives we gathered. How would we write and present them? Like Joan Metge in her work on Maori values and beliefs, we wished to pursue “not facts but understanding,” to bring forth that which “cannot be proved or disproved by . . . scientific procedures.” [1] We concluded that we would listen intently and present the stories in the women’s own words, as unfettered by our interpretive lens as we could manage. Yet we also knew that with the telling of each story would come interpretive choices: what to include, what to omit, and how best to capture the nuances of voice and the subtleties of silence. Therein would lie our greatest challenge and also our greatest reward.

Numerous writings on oral history and narrative corroborate our allegiance to women’s stories and to aspects of naturalistic inquiry—that favoring of natural settings and casual conversation for the exchange of life stories. [2] Women talking to each other about their lives, whether in the Pacific or some other part of the world, is a long and noteworthy tradition. It is an ancient endeavor, an activity, says Susan Geiger, that “predates writing and transcends research institutions” and, we insist, that may well refuse the constraints of both. [3] Gradually we peeled away the layers of our own traditional Western training and resolved to be the listeners and gatherers that we ultimately became.

Out of that process of reflection emerged a methodology and philosophy that has guided our work throughout the project. We summarize it below, with some adjustments to underscore our Latter-day Saint perspective:

We assume that being both a Latter-day Saint and a woman shapes one’s life experiences.

We accept as valid and worthwhile a woman’s interpretation of her world.

Our goal is to understand rather than control the material we gather. The life stories shared with us will not be used or manipulated to support personal or academic positions.

Our interpretive choices will be guided by collaborative reflection and by respect for the women we interview.

We see our work of listening to and gathering women’s stories as a way to help complement an incomplete historical picture of the Pacific.

We believe the views and experiences of Latter-day Saint Pacific Island women will provide insight into the intersections of culture, religion, and gender in the Pacific and beyond.

From the beginning, the Pacific Island backgrounds of four of our five team members were invaluable in knowing the protocol of the Pacific: Rowena is Chinese Hawaiian from Hawai’i; Debbie, Maori from Aotearoa; Rose, Chamorro from Guam; Seini, Tongan from Utah; and Kathleen, Caucasian from the Pacific Northwest. Jessika, a Caucasian from Colorado, joined our team later. Albeit outsiders in some respects—all living in Hawai’i and all from a United States university—the multiethnicity of our team enhanced our endeavor at every turn and provided a resounding statement about Pacific Island women.

Our journey began in Sāmoa, where we met and talked with women in the marketplace and shops, the schools, and the churches. We gathered their narratives in the open fales (houses) of the villages, in the government offices of Apia, around their supper tables, and in the shade of high-reaching palms. What began in Sāmoa we continued in four other island countries: Tonga, Aotearoa, Fiji, and Rarotonga of the Cook Islands. In each we encountered a profusion of experiences that came both planned and unannounced to shape and define our collaborative endeavor. A single illustration: word went out in Tonga, in the quick and efficient way that it does on an island, that we were there to talk to women and that we had only three days (a late arrival had deprived us of valuable time). The women came. Throughout the day and into the night, they moved in and out of our lodging, bringing food and laughter, but most importantly, bringing their stories. At nearly midnight on our last night, our new friend, Sita, concerned that we would leave Tonga without the mother-tongue voices of Latter day Saint women from the villages, asked that we loan her a tape recorder and hurriedly left. Who would she find awake at that hour? She returned early the next morning with two full interviews: one of herself (“I just pressed the button and started talking”), the other of an elderly woman who had been sitting up and waiting for her. “I knew you were coming,” the woman told Sita. Having gone to bed earlier that night, the woman dreamed a guest was on her way to her home. She awoke and dressed, confident someone would soon arrive.

Whakawhanaungatanga

Two cultural concepts, unspoken but firmly embedded in our methodology, deserve further comment—more for readers beyond the Pacific than within—for they were instrumental in calling forth the women’s voices. The first is whakawhanaungatanga, a word from the language of the indigenous people of Aotearoa that means “the process of becoming family.” Such a process was central to the sisterly connections we developed with the women we met. Whakawhanaungatanga began to unfold early in the preinterview phase, during an unrushed period of visiting and laying a foundation of trust and kinship that helped facilitate the gathering that followed, with minimum prompting from us as interviewers.

Whakawhanaungatanga became our ritual of encounter with each woman. The women wanted to know who we were and what we were about. We told them how we came to be there, what we hoped to accomplish, what would happen with their “voices,” and how we would keep in touch during the life of the project. In turn, they wanted us to know who they were in ways that were meaningful to them. Long before the tape recorder went on, they told of their families, villages, and towns, identifying ancestry and significant places in their lives in the customary way peoples of the Pacific introduce themselves. Although we had a schedule to follow, we put aside our pressing notion of time so that each woman could impart her background and ask questions unimpeded. Only then was she ready for korero, or the intimate talking-story that connects speaker and listener.

Ho‘okupu

A second cultural ritual woven into our research was ho‘okupu, a Hawaiian term that embodies reciprocity and the ceremonial gift-giving practiced throughout the Pacific. Each story from the women was a gift that invited ho‘okupu, and we had planned for it carefully, including a specified budget item in our grant request. We practiced our ho‘okupu deliberately, knowing that to the receiver the act of the giving is more important than the gift itself. The Western practice of quietly leaving a gift behind or sending something later was not appropriate. Instead, we presented the gift in a ceremonial manner, thanking the woman on behalf of ourselves, the others on our team, and our university, and then listened as she responded. Engaging in the traditional custom of ho‘okupu provided a meaningful closure to our time with the women while simultaneously leaving open the door of friendship for further communication.

“Oh, You Must Talk to . . .”

Frequently we are asked how we selected the women to be interviewed. A partial answer is, through the generous help of women we had contacted prior to our arrival, some who were BYU–Hawai‘i graduates, others who were family members and friends. Each arranged for us to meet several women, particularly on the first day of our visit. We learned quickly that no further planning was necessary, for the first women interviewed invariably led us to others. Once they understood our objectives and our desire for diversity, they were quick to think of other women we “must talk to.” On several occasions they left messages with women’s names and addresses, even setting up times and places for our meeting. In turn, this next tier of women had still others we “must talk to.” And on it went, providing a rich pool of personalities and backgrounds for our work. From the beginning we also relied upon and greatly enjoyed random meetings, those unexpected encounters that came along as we traveled from one place to another. When we could arrange it, we returned to record the stories of these newly met women.

Although most of the women were interviewed in English, we were able, through liberal assistance on each island, to gather a number of voices in the indigenous tongues of the Pacific. Often the women spoke in both English and their native language, creating a bilingual mosaic that required diligent translation upon our return. Translators for the narratives, primarily our own Pacific Island students, added another set of people affected by and contributing to the project. One young man translated the words of his grandmother interviewed in a Fijian village. Knowing her grandson would be the one listening to her words, she held the recorder lovingly, calling him by name and urging him to live a good life.

The project entitled “In Her Own Voice: Pacific Islander Women Speak” will soon conclude in a publication of narratives and images dedicated to Pacific Island women. The narratives that follow, drawn from that larger collection, are the voices of four Latter-day Saint women interviewed during the summer and fall of 1997. Each lives a life characterized by cultural and religious synthesis. Each has a story to tell. In her introduction to Toi Wahine: The Worlds of Maori Women, Kathie Irwin proudly refers to “the world according to wahine Maori,” a phrase that captures well what we seek to bring together here, the world according to women, Latter-day Saint women of the Pacific, speaking to us of their distinct lives and remarkable faith. [4]

Temaliti Losiale Kava (Tonga)

“I think for women, for us women, education never ends.”

If you come to my house, I’m telling you, there’s books over here, up to the ceiling, books over there, up over there. I don’t really have much in material things. Everything I have in my house is books. My whole life, if I’m not reading a book, I feel sick. With some of the books I started a library. Even the books people throw away, I go wash and clean and dry them very well, and I put them in a little library for the children, so they can read, so they can go to a dictionary that will help them learn how to spell. I love it. And my mind, sometimes I forget things, but when I read books, my mind keeps on growing, and I feel younger, and I feel wanted when I do that.

I was born in the northern islands of Vava‘u in the little village of Tu‘anuku. It’s a beautiful scene. The sea is so calm you never see the waves, even if it’s raining. Temaliti is a Polynesian name. It means a ball of fire, after the volcano in the northern islands. My middle name, Losiale, is a plant here in Tonga and is very fragrant and all white in color. Kava means the drink they make from plants. Before Christianity arrived in Tonga, we didn’t have Sione, Matiu, Mele or those names because they’re Bible names. We used the animals’ names, the sky, the trees, plants, the rocks—words like Maka, Kuli, Matagi—all names that have a meaning.

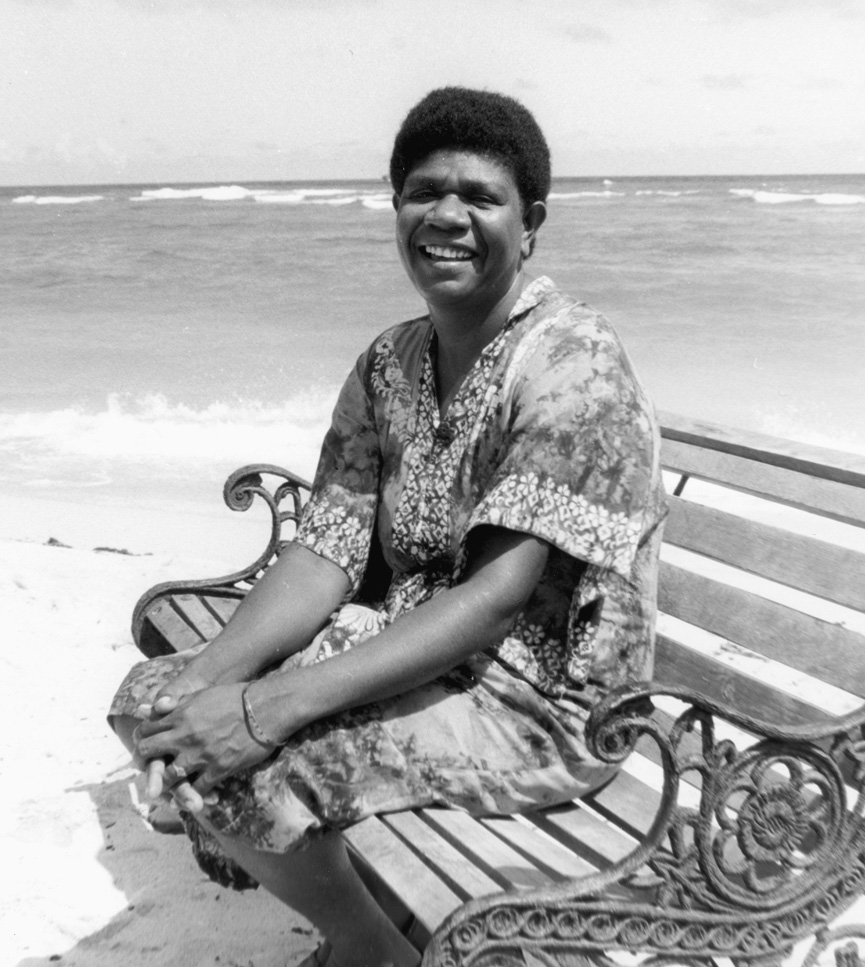

Temaliti Losiale Kava Courtesy of “In Her Own Voice” project

Temaliti Losiale Kava Courtesy of “In Her Own Voice” project

I moved with my mother from Vava‘u to Nuku‘alofa, where I went to school. When I graduated from Liahona High School, I got a scholarship to go to college in Hawai‘i. Oh, how I wanted to go to college! But my uncles were scared. At the time they didn’t know where Hawai’i was and what people looked like there and who was going to take care of me. And they heard that Captain Cook was killed there. So they stopped me from going. I stayed home and worked many years for the government as a primary teacher. And all the time I kept learning. I think for women, for us women, education never ends.

There were many challenges while I was raising my four children. I was paid so little, and my husband wasn’t working. But I didn’t give up. In my whole life, there’s nothing I couldn’t do if I worked at it. I always prayed that before I go down to the grave, I would graduate from a university. It was the challenge of my life because I had to take care of my children, and all that time I wanted to go back to school. I took correspondence courses, and in 1979 I got a scholarship and went to Hawai’i with my husband and my two daughters. Five years later I graduated from Brigham Young University–Hawai’i with a bachelor of arts in early childhood development. I was fifty-one years old. At the time I think I was the first married woman in Tonga to go back to school. Now they do it, but before, in the fifties and the sixties, no, they don’t. Once you got married, you’re out of education. You stay home. That’s how we view it.

Today I’m retired, but I’m still learning and still teaching. Our society needs help, needs teachers for all the women who didn’t go to school. I help them however I can, especially with their children. There are some children who cannot go to school because of financial problems. I help them in my house. They come, and I teach them how to write and how to read in Tongan, and I make them love reading.

Right now I’m raising five of my grandchildren. It’s just a very, very hard job to do. As you see, I’m growing old, but I didn’t want to see my grandchildren go astray. As I went overseas to Hawai’i and to the United States mainland, I saw the Tongan grandchildren going astray. They go in gangs, and they don’t know their Tongan ways. They don’t know our way of respecting old people. Tongans love and respect the mature people, but when I went there, my grandchildren jump here and jump there, and when I called their names, they said, “What? What?” That’s not the way to answer a call from parents or grandparents. They should answer, “Ko au, I’m over here.” When they pass someone, they should say, “Excuse me,” or “Tulou” in Tongan, but for them not even a word. And if they ask for something say, “Sorry, can I have this?” or “Please, Grandma, may I have this?”

Especially, I saw the way of sharing things is lost from them. They want things the most for themselves. But when I brought them home, there’s only one loaf, look over here, there’s only one loaf and there’s many of us, so we bless it, whatever little piece we have, and we share it among us. That’s the reason I want to raise them in Tonga. When they come here, they have the Tongan language. I sit down with them face to face. I hold them to my bosom and tell them what’s wrong and what’s right. And then I praise them when they’re doing good, or I hold them again and say, “That’s not the right way of doing this” or “That’s not the right way to ask things.” I tell them what is more important is their education. That’s how I stick to my grandchildren. Even though it’s a hard labor, I love it.

I plan to go back for my master’s by next year. My grandchildren told me, “Grandma, if you think you can make it in the best of health, we will supply everything, but we don’t know the good of going back to school. You cannot work because you’re retired already.” But I don’t think that education ends because you don’t work. I enjoy going to school; I enjoy reading; I enjoy new things. I ‘m very good with my hands, and I could sew and do lots of weaving, but I still want to go for the education. I think there’s always more to learn in life.

Moeroa Brothers (Cook Islands)

“Where did his soul go?”

One evening when I was just fifteen years old, my father came home and said to my mother for me to pack; I’m going to New Zealand. And I cried and cried because I didn’t want to leave them, you know, this is my island, the only place I know, and New Zealand is a big country. I’ll get lost in it! But he wouldn’t listen. He said, “No, you’ve got to go.” Being a young girl, what could I do?

Moeroa and Ngametua Brothers Courtesy of Jon Jonassen

Moeroa and Ngametua Brothers Courtesy of Jon Jonassen

So I left Rarotonga, and my life started from there. My dad used to write, but I wouldn’t answer for months because I didn’t like the way he sent me over, like they didn’t want me. And I used to put all my letters in my drawers. Then one day my girlfriend asked me, “What are all these letters? Open one,” she said. I told her, “No, leave it,” but she said, “Open it.” When I opened it, I read my father was sick, and I started crying. Then I wrote back, and from then on, I’ve forgiven my dad.

Eventually I moved to Auckland and stayed with my sister; she married a Samoan man. So she said to me, “Stay here with me and look after the kids.” But to me, I didn’t go there to look after any children; I wanted to go to night school so I can better myself. Then I met a girl who says to me, “You want a job?” It was a waitress at a café. I started working there, but they closed the place down because it was a brothel. The boss was running a brothel! Not with us, but a side business.

About then I met an Englishman, half Dutch. We didn’t get married, but I had my son, Andre. That’s the day my life began. I was twenty-three years old, and from that time, my independence dropped because in those days you don’t get money from the government, you go to work and look after your own child. And I might as well say it, I had a hard time taking care of him. And then I met the husband that I have now. He was Rarotongan, and he was a good man, good to my son, so we got married. We had a good life bringing up Andre together. At this time—I’m still in New Zealand—I wasn’t a Latter-day Saint, but my sister was, my older sister who married a Tahitian.

Then in 1983 my life was lost to me. My son Andre died. He was twenty years old. My husband and I, everything we did, we did for Andre and for his future, and then all of a sudden he was gone. He was a wonderful boy. When he died, I just wanted to give up living. Andre said to me once, “Why don’t you adopt a child?” He told me, “I’m going away, and I don’t want you to be alone.” I thought, What a silly thing to say; where are you going? He said, “I’m going to see the world, what’s out there.” And I asked him, “What is out there?” And he said, “Oh Mom, I can go. I’m a man now. I want to touch everything in my life.” That was three weeks before he passed away.

A few months later we visited my husband’s family, and I was still grieving for my boy. There were so many little kids there, and my husband said, “Uncle, give us one of those children, or two or three.” Six months later, he sent his son who said to us, “There’s a baby for you to adopt,” and I said, “Where’s the baby?” He told us we could have her after she was born, but I didn’t believe it. When Tasha was born, I am still thinking the young mother will change her mind. When she asked, “Can I have her for just two weeks?” I thought, Well, I won’t get her. But the next morning they brought her, a beautiful little girl. That’s how we have Tasha in our lives. And that’s when my life began.

I never thought I would come back to the Cook Islands, but when Andre died I used to have this vision nearly every week of the islands, everything, the villages, the mountains, the palaces. There was a Maori lady who used to interpret my dream, and she said, “How long your son been dead?” I said, “Four years; next year it will be five.” She told me, “When it’s five years, you go back to where you belong.” And the funniest thing, when the five years were up, I just came back for a holiday, but when my nephews started calling me a foreigner, I thought to myself, “Gosh, I am a foreigner because I keep thinking of going back to a place that I don’t belong.”

So I stayed, and that’s when I was taught the gospel of Jesus Christ. And that’s when my life truly began! When I was taught, I knew it was true the first time because only I know what I asked the Lord. Because when Andre died, what really worried me was, where did his soul go? And I kept asking the Lord, “Where did his soul go? Where is my son, Andre?” When the elders met me, they had the answers to my questions.

Right now, my daughter Tasha loves the Church. We were sealed in 1992. Later, when she found out she was adopted, she said to me: “Mum, it’s not true that I’m adopted because Andre is my brother and we’re sealed for all eternity.” It took her a long time to understand. I wanted to wait, but you know how the children say, “They’re too old for you, you must be their granddaughter.” And she used to ask, “Why are they saying that to me?” One little girl in the Primary, a very bright little girl, said to her, “Your mum doesn’t look like you, so you can’t be her daughter.” And so I told her. And I said to her, “Don’t worry, Tasha; don’t worry what they say. Just tell them mummy and daddy love you very much.” And now she’s getting over it. I’m teaching her every day that she’s a very blessed little girl.

When I was taught the gospel, it didn’t take me long to know it was true. I’m not afraid to share my beliefs. Every time I get up there in public, I feel confident because I’ve been placed by Heavenly Father to learn and to read and to study. My first day in genealogy, it was like a hurricane. The elders came up to me and said, “Sister, you were just baptized, and now you’re in genealogy!” And I said, “These are my ancestors. They’re excited because I’m going to save them.” Now I’m in the Young Women’s. I’m the oldest person there, and I love it! Yes, now I understand why my son was taken from me: so I can know the true Church of Jesus Christ.

Emma Lobendahn (Sāmoa and Fiji)

“This is the work the Lord prepared me to do.”

I was a very sick child. We were in Apia then. Every time I woke up in the middle of the night, I saw my mother kneeling down and praying, asking the Lord to help me, to cure me. One day she decided to go to the branch president and ask if they could fast for me. So the branch president went around to all the members of our branch and asked if they could fast, whoever could, to help me. So they did fast, and all these men came to our house to break the fast. I remember it was on a Friday afternoon. I probably was about fourteen years old. My mother prepared a meal for them, but they said they didn’t come to eat, they came to bless me. But before they came, my mother had cried and said, “If it’s God’s will, please, I want him to take my daughter away. She has suffered a lot.” Then it came to her: “Emma is not going to die. The Lord has a work for her to do.” So they came, and I remember them all kneeling down, all holding hands, and they anointed me with oil, and they said the same thing, “I know the Lord will save you because there is work for you to perform.” After they blessed me, they said the same thing again. In the night my mother dreamed of a medicine to cure me. I knew it wasn’t just a dream, that it was the answer, and in two weeks I was cured. From that time on, I went about doing things, and I forgot all about this blessing.

Emma Lobendahn Courtesy of “In Her Own Voice” project

Emma Lobendahn Courtesy of “In Her Own Voice” project

I came to Fiji in 1943, and in 1945 I married my sister-in-law’s brother. We decided to migrate to New Zealand. At the end of 1954, I came back to Fiji. There was fourteen of us when they first organized the Church. The first two elders came, Elders Abbott and Harris, and asked me to be Relief Society president. I said, “No, I’m sorry I cannot do that work because I don’t know very much about the Relief Society.” So the second time they came again to me and said, “We fasted and prayed; still you come up.” I still said, “No, I cannot do it.” So the third time they said, “Sister Lobendahn, we’ve been fasting all this time, and your name always comes up in our prayer. We see you, your face is always there, and we know you’re the one.” So when they said those things, I thought of the blessing that I had in Sāmoa when I was still a girl. That’s why the Lord didn’t take me when I was very sick. He saved my life to do this work.

So I served in Relief Society for twenty years, from 1955 to 1975. I did my best to struggle along because sometimes sisters don’t come. I think it happens to every place when we first start. When the construction people came to build the chapel, I assigned some of the sisters to wash clothes and help carry the work through until the mission was complete. I would always go there and cook and run down to the market and buy what other things the workers should have, like fish or meat, because most of their food was all canned stuff. So I helped them in that way. I feel I have done my part well to build up the kingdom of heaven.

I raised my children alone in the Church because my husband is a Catholic. He wanted me to go to the Catholic Church. He wanted his children to be raised Catholic. But I tried to raise my children the way I was raised with my parents. When we first came back from New Zealand, the only school available for my children was the Catholic school. One day the schoolteacher wrote me that some kids said that my children were from the Mormon Church. The teacher told me to stop taking my kids to the Mormon Church. But what I used to do, I would send them to the mass on Sunday morning, Catholic mass, then we went to the chapel for church and came home. But my children came home one Monday and showed me their fingers and knuckles where the brother hit them. My son would say, “Please, Mom, this is really painful.” I said, “That’s all right, just carry on. It won’t be long.” Another letter came, and I went to the elders to please help me to write a letter to the education department. There was a grammar school; you can go to that school only if you are part European. So the elders said, “Don’t worry; we’ll do it.” So they did, and after a while the school accepted my kids. I didn’t tell my husband at first. He came in the morning and the kids were ready to go to school, and they were wearing a different uniform. “What are you doing?” he asked. I said, “I am changing the kids’ school.” He wanted to know why, and I told him, “Because the brothers don’t want my kids to go to church.” He said, “Emma, why don’t you leave the kids until they grow up and decide for themselves what church they want to go to?” But I said, “No, that’s not my style. I want my kids to go to church now.” So that was that.

When it was time for my boys to be baptized, my husband just said, “No, the boys are not going to be baptized in the Mormon Church.” I said, “Okay.” So I left it for a time. One week passed, and I asked again and he still said no. I started to fast because I wanted my boys to be with the Church. I fasted all the time, every weekend. I fasted and asked the Lord to help me find a way for my boys to get baptized. I know they were old enough to hold the priesthood. One Saturday, I said to him, “I still want the boys to be baptized.” He said, “Go ahead and do what you think is right.” My three boys went on a mission, and he supported them, and he supported me in my calling even though he wasn’t a member. He supported me after realizing that he can’t stop me from going to Church. I want my children to remember that nothing comes to us without God’s help.

Ethel Ariembo (Papua New Guinea)

“I knew my Heavenly Father was with me.”

I was brought up in the Anglican Church. My ancestors were the ones who welcomed the Anglican missionaries when they arrived in my village on the northern coast of Papua New Guinea. Before they arrived, my great, great-grandfather sensed a message, and he told the people there were missionaries sailing towards our island. The people got ready, and they were all dressed in our traditional costumes when the missionaries arrived the next day. They held the Holy Bible in their hands and lifted it up, saying, “We are bringing a message for you.” So that was how the Anglican missionaries arrived in my area.

Emma Lobendahn Courtesy of “In Her Own Voice” project

Emma Lobendahn Courtesy of “In Her Own Voice” project

I am third-born in my family of eleven children, and I loved to go to church. Every Sunday I would go to church. I worshiped God with all my heart, and I was also very, very close to my mother. I followed her footsteps by helping old people and needy people who were very sick. I would just go and gather firewood for them and help them in anything that they wanted. So I was blessed, and even though I did not have much education in elementary school—I did not speak English very well at that time—I was blessed, and I really believed that Heavenly Father lived and Jesus was His Son.

From childhood I had an interest in nursing. We lived in a remote area, and because my parents were not very educated, we did not have balanced food. Often I had boils all over my body. So after high school I went to a nursing school in Eastern Province and trained there for three years. When I became a nursing officer, I was sent to my home village where I grew up. So I served my own people, my own community in my small village.

I will never forget one of the patients that I first served. He was chopping trees down to make a new garden, and a tree fell right on his ear and cut it off so it was just hanging down. Now, I was junior at that time, but when the man ahead of me did not have the courage to stitch it up, I said: “Well, I will do it!” So somehow I put the ear up against his head and tucked it in place and sutured it back. And it healed very smoothly and became the normal ear that it had been. I will never forget this. I was very young and inexperienced, and I knew my Heavenly Father was with me.

I met my husband, Benson Ariembo, when I was eighteen years old. On our first date we decided that we would be friends while he was away for further studies, then we would marry. A year before he graduated, in 1983, we got married in an Anglican church. Two years later my husband was converted to the Church by reading the Book of Mormon.

For a year he had been investigating some of the doctrines of the other denominations, and it happened one day that he was riding the bus home. Two girls about thirteen years old asked what was the time. He asked where they were going, and when they said they were going to seminary, he asked what church they belonged to. So they gave him a little Book of Mormon, about pocket-size, and told him about Joseph Smith. They said, “We cannot bear any more testimony at this time. We will give you this book to read it yourself and find out.” So that’s what he did.

It was a quick change in my husband’s life as he found the truth in the Book of Mormon. From the time he was given the Book of Mormon, he would just have dinner and read and read, and he would mark the important things that were touching him. It happened for a week, and he would not be with me and our little girls to tell stories and enjoy family life. So I asked him, “What kind of book is it that you cannot do anything now, just read and then go to sleep late?” And he said, “I think we are going to join this church.” I could not believe it! One day (oh, I regret to say this) he left the book on the table and I hid it in the cupboard, high up where he cannot reach it. And I thought, He will not find this book again. When he asked for it, I said, “The children must have put it somewhere or thrown it out.” But he asked again and again, so I gave it to him. He read it through, and the following week he compared it to the Bible, and he was greatly touched with the Spirit. And so that was how he was converted.

He was baptized, and soon after that he was gone to Indonesia for a time. I went to my former church, but the congregation had no good words to say about my husband’s decision. They were backbiting and gossiping, and that hurt me. The Anglican priest gave me an anti-Mormon booklet so that I would not join, but when I read this article, it did not make sense. I did not believe all the things it was saying about these Mormons. So I decided to follow my husband. In my heart I repented to my Heavenly Father for trying to hide the book and for saying all sorts of things about my husband. I prepared myself for when he returned; then I openly repented to him and told him that I was going to come with him to church. I sat very quietly and observed how the church meeting went and how it was organized, and I was touched by the Spirit. I knew my Heavenly Father was with me. I wanted to know more, and soon I was baptized.

My husband and I were the first to join the Church in our families. I teach our four children that we must be an example because when we are, others will become members. In our culture, you know, we don’t let our extended families away from us. We gather them, we fellowship them, even if it takes a long time. There was a relative of my husband’s who wanted his family to join the Church, but his wife said no. Two years later this family had a two-year-old baby who was very, very sick and in the hospital near us. The woman came to our house, and she cried and said, “I need your help.” My husband and I did all our best to convert this family. I had thirteen visitors in my house at that time, and each day I would cook for my guests and then go to the hospital because this woman had another baby, about six months old, and she could not help the husband with their very sick child. I took them food or helped nurse the sick child so they could come back to our house, wash and have dinner, and go back. I encouraged them, fasting and praying for this little girl.

But the girl had sickness spread all over her body. She was very weak. We fasted for the family to have strength, and her father had a vision about his daughter. He was softened by the Spirit to know there is a life after death. When the child passed away, I got my new bilum bag and put her dead body inside and carried it on my head, and my husband hired a bus so we could take the family home to their village. I believe just being an example helped to soften their hearts. They felt the Holy Ghost witness to them that there is life after death, and they accepted the gospel and got baptized.

The Church’s coming to Papua New Guinea has been good for families. The gospel has taught more good values, how to live with the family and with the community. This is especially important for the women. In Papua New Guinea, the women have second status, and they put men first. And the women do all the work, all the work in Papua New Guinea. They do gardening, they raise the children up, they feed the family, and they do housework. The men take all the responsibility in the community, and they look down on the women. As the Church is growing here, the women are now becoming more equal to the men, sharing responsibilities. The women can take callings and they can teach seminary; they can teach in the Young Women and Relief Society; they can support each other by listening and sharing spiritual experiences. It is a wonderful life for women in the Church!

Kathleen L. Ward is a Brigham Young University–Hawai‘i professor of international cultural studies with an emphasis in women’s studies and Black American culture.

Debbie Hippolite-Wright, a Maori from Aotearoa, is a Brigham Young University–Hawai‘i professor of social work and has a particular interest in Pacific Island women, families, and communities.

Rosalind Meno Ram is a librarian at the Joseph F. Smith Library and has great interest in the Pacific Islands and most especially the women of the Pacific.

Rowena L. K. Davis is an adjunct faculty member of social work at Brigham Young University–Hawai‘i.

Seini Mu‘amoholeva and Jessika Lawyer-Tora were also members of this project collecting Pacific Island women’s oral histories.

Notes

[1] Joan Metge, In and Out of Touch: Whakamaa in Cross Cultural Context (Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University Press, 1989), 21.

[2] Yvonna S. Lincoln and Egon G. Guba, Naturalistic Inquiry (Beverly Hills: Sage, 1985), 39–43.

[3] Susan Geiger, “What’s So Feminist about Doing Women’s Oral History?” in Journal of Women’s History 2, no. 1 (Spring 1990): 306.

[4] Kathie Irwin and Irihapeti Ramsden, Toi Wahine: The Worlds of Maori Women (Auckland: Penguin, 1995), 10.