Constructing the Temple

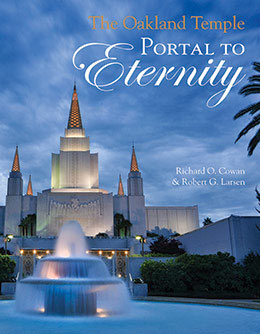

Richard O. Cowan and Robert G. Larson, The Oakland Temple: Portal to Eternity (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2014), 89–122.

1962 Ground broken by President McKay (Saturday, May 26); contract awarded

Pouring of concrete under way (September)

1963 Cornerstone laid by Joseph Fielding Smith (Saturday, May 25)

Roofed over and interior work progressing (December)

1964 Sculptures of Christ and Apostles lifted into place (spring)

End of construction, keys handed over to temple president (Friday, September 25)

Even though construction of the Interstake Center had consumed energy, time, and money to complete, there were some positive benefits. The hill was leveled, road improvements were made that vastly enhanced accessibility to the site, and utilities were brought to the property. All these improvements saved valuable resources and therefore expedited construction of the temple.

In March 1962, the First Presidency announced that ground would be broken for the Oakland Temple on May 26. They explained that by that time, “the plans for the temple will be completed, contracts awarded and everything in readiness to begin construction.” [1]

Selecting the Contractor

Jack Wheatley, who would become the temple’s contractor, had always been interested in mathematics and engineering. He graduated from West Point as a second lieutenant in 1950. Only two weeks later, the Korean War broke out, and almost immediately he was deployed there as part of a combat engineering battalion. At age twenty-two, he found himself building roads, bridges, and pontoons—all urgent projects that needed to be completed quickly. After a year and a half in Korea, he returned to the United States and rose to the rank of captain. Still, in 1954 he decided to leave military service. He then worked two years for Jacobsen Construction in Utah as a project engineer and estimator. He next went into business with his brother Leon building houses, apartment buildings (some for themselves), elementary schools, and subdivisions in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Early in 1962, the contractor for the Oakland Temple was selected by competitive bids—a process that had not commonly been used up to that time. Jack Wheatley had maintained a cordial relationship with the Jacobsens since leaving them and moving to California. Therefore, he and Leon formed a “joint venture” with Ted and Leo Jacobsen to submit a bid. Five or six bids were submitted. Church Building Department officials carefully scrutinized the qualifications and experience of the bidders and their subcontractors, as well as the total cost of the bid. The Jacobsen-Wheatley partnership submitted the winning bid of 3.5 million dollars, and at age thirty-five Jack Wheatley became project supervisor for the Oakland Temple construction. [2]

Jack quickly developed a comfortable working relationship with the temple’s architect, Harold W. Burton, who was now in his seventies. Burton was very demanding, as “the only quality he knew was to have a perfect temple.” Typically he visited Oakland every three or four weeks, spending two or three days to review progress and answer questions. He was one of the few architects Wheatley knew who could skillfully and accurately draw the details even on full-sized plans. “I looked to him for guidance on anything he felt we needed to do better,” the contractor reflected. [3]

Some thirty-five subcontractors worked under the general supervision of the Jacobsen-Wheatley consortium. They were responsible for such diverse matters as tile work, glazing, electrical systems and sound, elevators, floor coverings, granite facing, insulation, iron and steelwork, masonry, doors and frames, painting, plumbing and air- conditioning, roofing, sheet metal, and folding doors. [4] Thus a veritable army of specialized craftsmen would construct the house of the Lord on Temple Hill in Oakland.

Groundbreaking

Saturday, May 26, 1962, dawned bright and warm in contrast to cool rains, which had prevailed for the last several days. The entire First Presidency—David O. McKay, Henry D. Moyle, and Hugh B. Brown—together with President Joseph Fielding Smith and Elder Harold B. Lee of the Council of the Twelve, and Presiding Bishop John H. Vandenberg, traveled to Oakland to dedicate the site and break ground for the new temple. They were met at the San Francisco Airport at 7:40 a.m. by O. Leslie Stone, president of the Oakland-Berkeley Stake and chair of the Oakland Temple Committee. They immediately drove across the Bay Bridge to the temple site, where they met the other stake presidents in the temple district at 8:30 a.m. They held a press conference a half hour later. [5]

Some 7,000 gathered at the Interstake Center on Temple Hill for groundbreaking ceremonies, which began at 10:00 a.m. This was “the largest group of Latter-day Saints ever assembled in Northern California.” [6] President Stone conducted the service. First, he read a letter from California’s governor, Edmund G. Brown, in which Brown praised the Latter-day Saints, who “have done much to contribute to the growth and development of California.” In his remarks, President McKay emphasized the purpose of temples and temple work and reviewed the events surrounding the acquisition of Temple Hill. He declared that “one of the distinguishing features of the Restored Church of Jesus Christ is the eternal nature of covenants and ceremonies” and added that “love is just as eternal as the spirit.” He testified, “In the house of the Lord where the marriage ceremony is performed by those who are properly authorized to represent our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, the union between husband and wife, and between parents and children, is effected for time and all eternity.” He also explained that all are required to be baptized to enter the kingdom of God, and that our privilege to receive this ordinance in behalf of those who died without it confirms that God’s plan is just. President McKay believed that these two great purposes of temples would “appeal to the justice of those who love the truth.” [7]

President Moyle related how he had recently stood on the Nauvoo Temple site and received the conviction that the pioneers must have obtained “the strength which carried them across the plains as a result of having built that temple and received the endowments of the Lord therein.” He then suggested that the Oakland Temple would similarly “give to the Saints of today the strength to carry on and be an ensign to the world and to have the courage and the power, the inspiration to lead the righteous of the world into light and out of darkness.” President Brown asserted that “if we did not believe completely in the doctrine of immortality we would not make the sacrifices we do for the building of temples in order that we might enjoy the blessings of Heaven after life.” [8]

President Smith taught that in the merciful plan of Jesus Christ, the gospel must be preached to the millions who died without it, and that our duty is to seek out our ancestors as far as we can go. Elder Lee testified that the decision to build temples comes through divine revelation to the prophet and that they would continue to be built; there would probably be a hundred temples, and they would not be enough to accomplish the work that needed to be done. Bishop Vandenberg affirmed that “this people will continue to build temples. The Lord requires it of them and we delight in doing it.” [9]

The official party then went outside onto the temple site, where they ceremonially turned over the soil with gilded shovels to symbolize the commencement of construction. These proceedings were carried by closed-circuit television to the throng still inside the Interstake Center. In this way, they were able to witness what was said and done more clearly than if they had joined the group outside. In conjunction with the groundbreaking, President McKay officially dedicated the temple site. [10] On this occasion, eighty-eight-year-old President McKay prophetically remarked that he would return to dedicate the temple itself.

After the groundbreaking concluded, the officials from Church headquarters, together with the stake presidents from the temple district and their wives, enjoyed a lunch at the nearby Claremont Country Club. At 4:00 p.m., President McKay and his party departed on their flight home.

Construction Moves Forward

The contractors received offers from members in such distant areas as Germany or South America to come and work free of charge on the temple. Nevertheless, they were legally bound to hire only union workmen in the various trades. Most were not members of the Church. Still, under the direction of Gary Dalrimple, the project engineer and therefore member of the leadership team, each workday started with a brief prayer meeting, with the men standing in a large circle. Dalrimple would usually call on one of the few other Latter-day Saints to pray. At first, most of the thirty or forty workmen who were on the site for a typical day chose not to participate, thinking the practice was strange. As the work progressed, however, they came to appreciate that they were building a temple to God, and attendance at the morning devotionals increased. At one of these gatherings, a burly, “cigar-smoking” electrician admonished the group that there had better not be any swearing or foul language on the job, because what they were building was holy. For the most part, the workmen observed this standard, allowing a special spirit to prevail on the site. [11]

Because the site had already been leveled in connection with the construction of the Interstake Center, work on the temple could begin immediately on the Monday morning following Saturday’s groundbreaking. One of the first tasks was to excavate the trenches and set the forms for the temple’s concrete and steel foundations. Beneath the basement level, the foundations under the central, or tower, portions of the building were an additional twelve feet deep, while those under the remainder of the structure were eight feet deep. [12] Thus, in some places the excavations had to go as much as twenty-one feet deep, a difficult task because of the rocky nature of the site. These excavations were completed by September and the pouring of concrete was underway. The cement slab for the temple’s basement was two feet thick. Next came the main floor and the walls. Workmen hoped to complete this phase of the work before the rainy winter season. [13]

Because of the granite facing and other features of the building, the concrete walls and floors had to be within tolerances of only about a quarter inch. Therefore, the Jacobsens sent Robert C. Loder, who “knew concrete work upside down and backwards,” to be superintendent on the project. Bob had worked in construction ever since childhood with his father. [14] Dalrimple drew the layouts and inspected the accuracy of dimensions as the work was completed.

Arthur Price, a gentleman in his upper eighties, had been appointed by the Church to protect its interests; as construction supervisor, he monitored the quality of the work being done on the temple. A native of Ruaben, Wales, Price had begun his architectural career at the age of nineteen. As an architect with the Church’s building committee, he had performed a similar quality-control function some forty years earlier during the construction of the Arizona Temple in Mesa. Specifically, he had selected the right kind of sand, gravel, and cement and had helped conduct tests to determine the optimum mixture to produce flawless concrete that could withstand the ravages of time. This earlier experience qualified him to supervise the concrete work and ensure similar high quality at Oakland Temple. As an employee of the Building Department, he had actually helped to draw the plans for the Oakland Temple under Architect Burton’s direction. [15]

When Jack Wheatley first met Price, he wondered how a person of his advanced age could perform his work, such as climbing up scaffolding to check the quality of the 170-foot central spire. Arthur did succeed, however. He had a small office on the site and was on the job every day. Often he was the first one there, Contractor Wheatley recalled.

Granite Facing

By the beginning of 1963, the foundation was in place and work commenced on the upper part of the temple. The reinforced concrete walls were from eight to twelve inches thick, and there was a considerable amount of steel in the structure. The walls and towers were faced with over 75,000 square feet of granite. One of the most interesting and challenging construction jobs, and therefore one of the most significant subcontracts, was the placing of these great blocks of stone. This work was awarded to a partnership of three young, yet experienced and skilled, men. All were members of the Church and wanted to use their expertise to help build a temple to the Lord. They were Walter E. Hirschi, Glen R. Nielsen, and Stanley J. Harvey. [16] Hirschi and Harvey were brothers-in-law. Harvey and Nielsen lived in the same Saratoga ward in California, and because both were builders, they had become close friends. They had worked together on building the nearby Los Gatos chapel, so were familiar with how the Church’s building department functioned. [17] “When we learned of the approval of the First Presidency for the building of a temple in Oakland,” Stan Harvey recalled, “we had a desire to assist in this great construction job—the building of a Holy Temple—and called upon the Church Building Committee to discuss how we might contribute our skills and experience as builders, primarily as stone masons.” [18] In the light of what they were told, the three builders decided to join forces. They formed a partnership and ultimately incorporated as the Harvey Nielsen Hirschi Company. [19]

Harvey, Nielsen, and Hirschi obtained copies of the plans and working drawings for the temple and consulted with members of the Church Building Department in order to become thoroughly familiar with “the details and specifications of the work to be done.” In one of these discussions, Harvey asked, “How long is the building designed to stand?” He was answered, “One hundred years, but if it is used for one day, the Church leaders feel we will have gotten our money’s worth.” “This astonished us,” Harvey reflected, “but later, as we considered it, we agreed it was an interesting and appropriate answer.” [20]

The three wanted to make their bid as low as possible; they would have been willing to work as “labor missionaries,” donating their services. Because the job was so large, however, they were instructed to submit a formal bid. Only one other company bid on the granite contract. When the three partners learned that they were the lowest bidder by over 80,000 dollars, they worried for a moment that they had forgotten something. Still, they were grateful to be awarded the contract.

The beautiful and generally flawless white granite came from the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The Raymond Granite Company, which supplied it, was located about thirty-five miles northeast of Fresno, California. It was “a wonderful company operated by some very fine men who were very helpful and courteous in all our dealings with them,” Harvey affirmed. “It was interesting to see how they quarried the huge blocks of granite. They were literally ‘sawed’ out with a special saw like a band saw.” [21]

All the granite was precut at the quarry to meet specifications in size, shape, and texture (polished or unpolished). A few areas required polished granite, such as around the benches on the temple’s terrace. Rough-textured granite, which was used for the walls, was created by being passed slowly under a flame from gas jets. Most blocks were rectangular, measured about nine-by-five feet, were four inches thick, and weighed about 1,700 pounds. The three partners often wondered how ancient builders could have moved and hoisted such huge building blocks and stones into place without modern equipment. The builders had to create their own devices to do the job. Glen Nielsen was “a genius in developing methods and equipment,” Stan Harvey gratefully acknowledged. [22] They needed a variety of hoists and cranes to place the granite. For example, they constructed a unique monorail system across the top of the building to move the huge slabs. The electric hoist was suspended from wheels that rolled along a large I beam; it could almost be moved by hand, even when carrying one of the heavy granite slabs. Some of the panels were set into place using a large rotating crane situated in the center of the building. Because the stone slabs could be quite brittle, great care was needed in handling them. One day, a wind was blowing when the panel next to the cornerstone was set. As it was moved into place, a sudden gust slammed it hard against the building. Surprisingly, there was no damage; Stan Harvey described this as a miracle. [23]

A special method was devised for fastening, or “tying,” the granite slabs to the steel and concrete walls of the building and to each other. Each granite slab had three slot openings on the top and bottom and two on each side. Slender ties of stainless steel that were about six to eight inches long five-eighths of an inch in diameter and had a ball on the inner end were inserted into the walls. Dry-pack cement was then pounded in tightly around the shaft to keep it from slipping out. Each of these anchors had two “ears” that fit into the slots on the two adjoining granite slabs. At first, holes for these steel pins had to be drilled by pounding a star drill with five points into the concrete and twisting it by hand until the desired depth of three to four inches was achieved. Shortly afterward, however, a power roto-hammer drill became available; this greatly sped up the work, and Stan Harvey regarded this timing as another miracle.

Cement trucks brought the grout to the site and emptied it into the grout pump. The three builders devised a special tub to then haul the grout to where it was needed. This bucket was about two and a half feet wide and could fit right against the temple’s walls; it narrowed across the bottom to a long door that could be opened gradually by a lever to allow just enough grout to pour into the inch-wide space between the granite facing and the temple’s reinforced concrete walls. Higher up on the building, grout was pumped through heavy hose lines and directed through a nozzle into this space. Lead spacers—about one inch square— were placed on top of one slab to allow grout to fill in and to keep the weight of the slab above from squashing out the grout, thus creating a perfect seal. [24]

In April 1963, the Church News summed up the status of construction. “On the first level, nearly all of the siding of four-inch granite veneer is in place. The elevator shafts, the boiler plant and most of the heating units have been installed and at least fifty percent of the duct work is finished. Over 6,200 yards of concrete have been poured. In a few days the giant tower crane will be jacked up to begin work on the next level. Almost half of the interior lathing and plastering has been finished.” [25]

Laying the Cornerstone

Temple cornerstones are reminders of Paul’s description of the Church as “built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Jesus Christ himself being the chief cornerstone” (Ephesians 2:20). In the nineteenth century, when temples were built of large hewn stones, the placing of the cornerstone marked the beginning of construction, as with the Kirtland, Nauvoo, and Salt Lake Temples. When reinforced concrete became the norm during the twentieth century, cornerstone layings were purely symbolic and were conducted at some point after the walls were at least partially completed. In the early 1980s, however, the cornerstone laying would become part of the dedication proceedings after the temple was finished. Hence, over the years, the placing of cornerstones has shifted from the beginning to the completion of construction.

Despite heavy rains, construction on the Oakland Temple moved forward on schedule. The cornerstone ceremony was conducted the Saturday morning of May 25, 1963—just one year after ground had been broken. Presiding was Elder Joseph Fielding Smith, President of the Quorum of the Twelve. Because the temple was built on a hill, there was very little space where people could assemble close to the building. Therefore, the 6,236 Saints who gathered for the occasion were accommodated in the nearby Interstake Center, where they watched the proceedings by closed-circuit television—as had been done the year before at the groundbreaking.

Under the direction of Elmo R. Smith, second counselor in the Oakland-Berkeley Stake presidency, a variety of meaningful artifacts were collected and placed in a copper box. These included the standard scriptural works of the Church, current copies of periodicals describing Astronaut Gordon Cooper’s twenty-three-orbit flight around the world, a set of coins minted in the current year, recent issues of all the Church periodicals, and a fifty cent piece coined in 1830, the year the Church was organized (donated by Annaleone D. Patton of Berkeley). This box would then be placed in a space in the temple’s wall.

The services were conducted by President Stone of the Oakland-Berkeley Stake and chairman of the Oakland Temple district. Also, in the main auditorium of the Interstake Center was the Salt Lake Mormon Tabernacle Choir, which was then on a California concert tour. They had presented a concert in the famed Hollywood Bowl Thursday evening and in San Francisco’s noted War Memorial Opera House on Friday evening. At the cornerstone ceremony, the choir sang “We are Watchmen on the Towers of Zion,” with words composed by President Joseph Fielding Smith; Jesse Evans Smith, President Smith’s wife, was soloist for this number. Also present was Elder Richard L. Evans of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, who was the well-known voice for Music and the Spoken Word, the choir’s weekly network radio broadcasts.

At the designated point in the proceedings, Church leaders left the Interstake Center and went to the corner of the adjacent temple to participate in the actual placing of the cornerstone. Arthur Price, who had celebrated his eighty-ninth birthday the week before, had broken an ankle bone a few weeks earlier but insisted on having the cast removed in time for him to be present for this occasion. An instantly developed Polaroid picture of him and President Smith preparing to set the cornerstone was placed in the box just before it was soldered closed. Price then supervised the putting of mortar around the box and President Smith’s placing the commemorative granite plaque to cover the opening. As the cornerstone was placed, the choir and congregation in the nearby Interstake Center sang “The Spirit of God,” a moving and impressive experience for those present.

The cornerstone laying received extensive press coverage, including television and articles in San Francisco, Oakland, and other Bay Area newspapers. “Most of the news reporters and photographers were prepared to stay only a few minutes,” the Church News reported, “but after looking over the situation they called their papers and arranged to stay for the whole service.” [26]

A report at the end of 1963 summarized progress made during the second half of the year:

Special effort was made the past few months to get the building roofed over before the onset of the highly unpredictable northern California rainy season. Many new craftsmen have taken over the interior work which is also well under way. All of the rough paneling has been completed including the tile floors and walls of the dressing rooms. . . . Viewed from the adjoining freeway, the granite veneer blocks which form the facing of the exterior walls of the Temple, create an impressive sight as they reflect the light of the sun. The entire structure stands atop of “Temple Hill” as a sentinel overlooking the blue Pacific Ocean. [27]

Overcoming Some Challenges

The three stone subcontractors—Walter E. Hirschi, Glen R. Nielsen, and Stanley J. Harvey—developed a close working relationship with Arthur Price. Glenn Nielsen reflected:

Brother Arthur was one of the most humble men I have ever met, yet he was also one of the strongest men I have ever known. He was a man of perfection. He was a man that understood his job and his job was to see that the Oakland Temple was built like our Father in Heaven wanted it built. Brother Arthur was a man who loved and trusted our Father in Heaven and I know that he talked to Him every day. He told me if I had any problems about how the granite stone-facing was to be set or how to do our work on the temple to be sure and pray about these things and that our Father in Heaven would answer our prayers. He told me that it was God’s temple and he would let me know how He wanted the work to be done. [28]

Even after Price broke his foot, he was able to keep tabs on the work from his home and office across the street. One day he asked the three granite contractors to have dinner with him. He invited them to examine the veins in a distant leaf using his telescope that was fitted with crosshairs. They then realized how he was able to know about every detail of the work on the temple.

“One day when I was laying out the placement of the stone,” Nielsen remembered, “Bob Loder, the building superintendent, came up to me and said, ‘Glen, I want you to know that you must be sure that the stones are perfectly plumb level or else Brother Arthur will have you do them over until they are right.’ Bob then said, ‘That man has eyes like an eagle. [He’ll] know if the least little thing is wrong.’”

Nielsen described how Arthur approached them on another occasion: “‘Now, Brethren, I want to make it clear that the work must be done perfectly. I don’t want to be called up before the Lord and have him say to me, “Arthur, what went wrong down there?”’ He made it clear that he didn’t want to be caught in that kind of a situation and he also reminded us that we would be standing right there with him so it was best that we saw to it that the work was done right.” [29]

Price’s attention to detail was seen in connection to the temple’s towers. The white cast concrete panels for the towers were produced by the Buehner Block Company in Salt Lake City. This family-owned business had received similar contracts for the Idaho Falls and Los Angeles Temples. They regarded the obtaining of these contracts as a fulfillment of the patriarchal blessing given to Carl Buehner, which declared that “he and his sons would help erect temples for this Church.” [30] Buehner had emigrated from Germany in 1901 and started this cement-products business in his backyard.

Using large sheets of paper laid out on the floor of the nearby Interstake Center’s cultural hall, Arthur Price double-checked the layout of the concrete panels. It was very important that they come out even in order to create a proper appearance along all the edges. One day Arthur approached Glen Nielsen and asked if they had checked the layout for the tower. He believed there was an error made in the tower panels. Glen promised Arthur that if they found a mistake when they started setting the tower, they would let him know. “Sure enough, when we reached the third section of the main tower,” Nielsen recalled,

the stone was 5/

The north and south walls of the main building feature sculptured panels that were thirty-five feet wide and thirteen feet and one inch high. Even these figures were designed by the architect, Harold Burton. The panel on the north front depicts the Savior in the Holy Land as recorded in the New Testament. There are five pieces—two background panels, two depicting in relief the multitude on either side of the Savior, and one central figure of Christ with his arms raised. The sculpture on the south depicts the Lord visiting the inhabitants in ancient America as recorded in the Book of Mormon. It consists of just one large panel. A small model of the sculptures was shown to President David O. McKay. He approved almost everything, but insisted with a feeling of unexpected certainty that a few details of the Savior’s appearance needed to be corrected. [32]

Most of the carving was done at the granite company, but the sculptures were to be finished once placed on the temple. These sculptured panels “grow out of the face of the building,” and, being carved from the same granite as the rest of the exterior, they seem to be an integral part of the temple itself. [33] Safely lifting these huge artworks into place posed a particularly difficult challenge.

By the spring of 1964, the builders had to make a decision concerning how to set these large sculptured panels into place. Stan Harvey and Glen Nielsen made a trip to visit the granite company in Raymond. “When I first saw those beautiful panels they were about half finished,” Glen recalled, “but even then they were beautiful.” [34] Stan’s reaction was similar. “The first time I saw them, I just couldn’t hold the tears back, because there was the Savior in stone.” [35]

Nielsen and Harvey asked officials of the granite company if they had any equipment for picking up the sculptures and setting them into place. Unfortunately, there was no method to recommend. The brethren therefore tried desperately to think of some way to accomplish the task. They finally came up with what seemed to be the best solution. Because there was only about one-fourth of an inch of clearance on each side and on the bottom, and a space of only one inch behind the panel in which to pass cables, they concluded to drill “some kind of a hole in the sculptured panels wherein a bolt could be inserted” for lifting. They consulted with the architect and explained to him what they thought would work best. Nielson told him that “we would have to put two holes in each panel for the bolt to go through and that would let us move the large panels into place. He told me to go back over to the stone company and tell them what we had decided to do and if that was the only way to handle the panels we were to go ahead and have the holes drilled.”

Early one Saturday morning, Glen Nielsen drove with his little daughter, Kathy, to the granite company in Raymond. “When those beautiful sculptured panels were shown to us I marveled at what I saw,” Glen recalled. “I told the man who had done the work about the drilling of the holes and where I thought they should be drilled. He said to me that he would not drill any holes, that there had to be another way. I asked him if he had any ideas and he told me he did not. On my way home, I couldn’t think of anything but what I had seen and how beautiful the sculptured panels were.” Nevertheless, he asked the architect to contact the granite company, ordering them to drill the holes. Still, when the sculptures were delivered to the temple site, there were no holes! “I felt so alone,” Nielsen reflected. Hoping to get some direction, he went over to visit his “good friend” Arthur Price. “Glen, there is a way,” Arthur counseled. “Now you go pray about this and you will find a way.” Glen had prayed for some time about this matter and knew that Walt and Stan had also been praying about it. Still, Glen affirmed, “Again I went to my Father in Heaven with our problem and I asked Him to please show us the way to pick up these large panels which weighed approximately twelve tons, without accident and if he would show us the way I would never use the method for my financial gain.” Even a slight bump could break off the Savior’s arms, requiring the whole figure to be sculptured again and causing a major delay. The time grew very short and the crane had been ordered, and they needed to figure out how to lift the sculptures. [36]

One Sunday— just before the time when the sculptured panels needed to be set, Glen Nielsen’s daughter, Kathy, gave a talk in the junior Sunday School (now Primary), and Nielsen went to listen to her. He recalled, “I was sitting in the back by myself, and as I sat there I was shown the way we were to pick up the panels. It was as clear to me as if I looked at someone face to face. I knew the exact number of bolts to use, their size, the metal to use and how it was to be constructed.” [37] Stan Harvey, who was waiting for him just outside, remembered how Glen came running out and exclaimed, “Get a piece of paper and a pencil, I have just seen how to set those stones!” [38]

The unique clamp for lifting the sculptures consisted of two heavy metal plates attached to hoisting cables, one behind and the other in front; together they formed a cradle around the bottom of the stone. Across the bottom of each plate was a row of a dozen quarter-inch holes through which stainless steel bolts held the two plates together. After the stone panel was in place, these bolts were unscrewed from the front and removed. The rear plate could then be lifted out from behind the stone before the space was filled with grout. The stainless steel nuts, which would not rust, could be safely left behind. Harvey gratefully acknowledged that “the crane operators were the most careful technicians you could imagine. They did it with hand signals.”[39] The segments of the sculpture fit together so closely that the joints between them could not be seen.

“The special gift from our Father in Heaven worked out just perfect,” Glen Nielsen testified.

It picked up the panels and just put them in place just right. Everyone that was working on the temple at that time stopped working and came to watch as this miracle was performed. My good friend, Arthur Price, came up to me and asked me how I thought up that most ingenious clamp. I told him of my prayer and Brother Arthur looked me right in the eye as if to say, “Yes! It is His house and He will show the way.” He reached out and patted me on the shoulder and went on his way. I will always love my Father in Heaven for what He has done for me. I know that He lives and that He will answer our prayers. [40]

Construction Moves toward Completion

As the work progressed in the temple’s interior, Jack Wheatley—the project supervisor—noted that the quality of ceilings, walls, stairways, doors, light fixtures, and other finishing details was of a much higher quality than on the usual job. [41] In addition to the primavera wood in the celestial room, many beautiful woods would adorn the temple’s interior. They included teak, walnut, white oak, cherry, birch, African mahogany, and avodire. [42]

The building was heated by steam brought through a tunnel from the heating plant, which was built into the side of the hill below and directly behind the temple. Two medium-sized Kewanee gas-fired boilers could be used separately or in combination, depending on how much steam was required. The heating plant also housed air-conditioning equipment. The temperature in individual temple rooms was regulated by a thermostat that could direct either warm or cool air into the room as needed. [43] This type of system, though of high quality, is no longer common and was eventually replaced.

Fitting the large metal baptismal font into the temple was a difficult task because the doors were barely wide enough. Harold W. Burton had thick rubber molds made of the oxen he had designed decades earlier for the Alberta Temple in Cardston, so they were reproduced for use for the font in Oakland. They were cast in light concrete by the Buehners in Salt Lake City. The physical exertion of moving the oxen and precisely placing them in their exact spots was a technical construction challenge, because lifting equipment could barely fit into the restricted space. Fitting all these elements together and providing the needed plumbing for the font posed a considerable challenge for the builders. Gold leafing the oxen was accomplished by Church members Rudy Coffing and his wife, Mavis, who were involved in other interior decorating work in the temple. [44]

On September 12, the Church News reported that the “final details of finish work on the Oakland Temple, including furnishing and landscaping, will get under way immediately.” [45] Architect Burton was personally involved in finishing the temple’s interior. Along with designing the building itself, he designed its furnishings—including tables, chairs, and sofas. Hence none of these items could be purchased out of a catalog but had to be individually made. He even selected the yarn for the carpeting and had it woven to his specifications. “He knew everybody,” Wheatley marveled, “so knew just where to go for marble work and these other jobs.”

Because of his legal background, W. Glenn Harmon, Berkeley Stake president, became involved with the concerns of people living just below the temple. As they watched the large building go up, they wondered if the weight of the temple and other buildings would place too much strain on the bedrock, resulting in soil slippage, thus damaging their homes. The issue of frost level came up as well. In cold climates such as Minnesota, frost-level criteria is found in building codes. Foundations must be anchored to bedrock below the frost level to prevent weakening of the foundation by alternate freezing and thawing of the soil. Church builders and Harmon spent considerable time looking for evidence of a frost level. After considerable effort, experts determined that a frost level did not exist in the Oakland hills. It was never sufficiently cold long enough for the subsoil to freeze. However, if any of the temple’s neighbors had a problem with ground slippage, the Church wanted to make it right. [46]

As the temple was being completed, President McKay felt that with the size and location at the very front of the property, the red brick exterior of the Interstake Center would detract from the temple itself, so the brick was painted over with off-white to match the temple. [47] Many Church members did not know of this change, so were surprised when they came to Temple Hill and saw the center’s new appearance.

The original contract with Wheatley-Jacobsen was only for construction of the building itself. About two months before the project was completed, however, Jack Wheatley received a supplementary contract for additional work—including the parking lot, walks, landscaping, fountains, and ornamental waterways. All this had to be completed before the open house, the dates already having been announced. Because his regular crews were already busy completing the temple itself, some additional workers were needed. The stone subcontractors were of particular help.

One of the most unique and beautiful features of the temple’s landscaping is the “rippling brook,” or cascade, flowing northward from the temple’s forecourt to the entrance on Lincoln Avenue. Just a few weeks before the temple’s scheduled open house, Bob Loder and Harold Burton were standing on the temple’s roof looking north towards its entrance. Loder commented that such a beautiful building should not only be seen behind a parking lot. When Burton asked what could be done, Loder responded that he envisioned “a river with white rocks, running down towards Lincoln Ave. with fountains on either end.” As they discussed this concept, Burton became very excited and promised to “get the clearance and the money for it somehow.” Douglas Burton of Burton and Son Architects in Los Angeles designed the brook. The streambed was constructed with attractive white onyx stones from Utah. Water from a graceful fountain at the temple gate flowed to another fountain next to the street entrance, where it would be recycled back to the point of origin. Two Oriental-style arched bridges spanned the stream. Flower beds along each side added to its beauty. Loder and others worked through the night and completed the pumping system just minutes before the open house began. [48]

The last task to complete the temple’s interior was the installation of 200 upholstered theater seats in each of the temple’s two endowment presentation rooms. They had been ordered from a manufacturer in the southern part of the United States, but a strike prevented the seats being delivered on schedule. During August and September of 1964, “the Building Committee in Salt Lake City had been in almost daily contact with the manufacturer and had been assured the seats would be delivered to the Temple in time to accommodate the public viewing.”

The open house was scheduled to begin Friday evening, September 25. When the seats had still not arrived on Tuesday morning, the temple presidency reluctantly considered the possibility of renting and setting up folding chairs temporarily. At about 11:00 Wednesday morning, however, “an elderly workman” arrived at the gates with two large trucks carrying the seats. He was asked, “Where is the crew to install them?” to which he replied, pointing to a young man by his side, “This young man and I constitute the installing crew, and we will get the job done in time.” They had brought sleeping bags and planned to work through the night. On Thursday evening they had planned to go out for a hot meal, but the watchman had already locked the gates, so they couldn’t get out. They had to eat the last of the cold food some temple workers had given them instead. On Friday morning at 9:00, the job was completed—only a few hours before the first open-house visitors were scheduled to arrive. “The man and his young helper were thanked profusely; one of the temple staff was assigned to take them out for a good hot meal, and thereafter, with little fan-fare, they left and began their long journey homeward.” [49]

Just a short time before, as the temple was nearing completion, Church President David O. McKay made a surprise visit to inspect it. “We all met in the celestial room,” Stan Harvey recalled. “I was standing with my wife when these two great men, President McKay and Arthur Price, who had been close friends for years, saw each other. They didn’t say a word. President McKay came in from the northeast corner and my dear friend Arthur was standing at the southeast corner. They just stood and looked at each other and I know what our Prophet said to Brother Price, although not one word was spoken: ‘Well done, thou good and faithful servant.’” [50]

Notes

[1] “Oakland Temple Groundbreaking, May 26,” Church News, March 17, 1962, 2.

[2] “Contracts Awarded for Oakland, S. L. Temples,” Church News, July 21, 1962, 3.

[3] Jack Wheatley, interview by Richard Cowan, December 3, 2009, Provo, UT, in possession of Richard Cowan.

[4] For a complete list of subcontractors, see appendix F.

[5] “Temple Groundbreaking, May 26,” Church News, May 19, 1962, 2.

[6] Delbert F. Wright, “Building the Oakland Temple,” 1979, draft booklet, Oakland Stake Archives, 23.

[7] “Pres. McKay Dedicates Plot for Erection of New Oakland Temple,” Church News, June 2, 1962, 15, 18; for a complete text of President McKay’s remarks, see appendix C. Henry A. Smith, “Delegation of Church Officials Attend Dedication of Oakland Temple Site: 7,000 Witness Rites at Groundbreaking,” Church News, June 2, 1962, 14.

[8] Smith, “Delegation of Church Officials,” 3, 14.

[9] Henry Smith, “Delegation,” Church News, June 2, 1962, 14.

[10] Henry Smith, “Delegation” Church News, June 2, 1962, 14. For the text of his site dedicatory prayer, see appendix D.

[11] Stanley J. Harvey, conversation, January 24, 2014, notes in possession of Richard Cowan.

[12] Wright, “Building the Oakland Temple,” 28–29.

[13] “Cement Poured at Oakland Temple,” Church News, September 1, 1962, 14;

“Oakland Temple Construction Moving Ahead,” Church News, October 13, 1962, 15.

[14] “Born to Build,” Argus, February 28, 2000.

[15] “Busy at Drawing Board Despite His 91 Years,” Church News, January 30, 1965, 4.

[16] Wright, “Building the Oakland Temple,” 33.

[17] Harvey, interview by Richard O. Cowan, September 6, 2009, Provo, UT, recording in possession of the interviewer.

[18] Harvey, remarks, fireside in the Dublin Ward Chapel, September 30, 1979, transcription in Delbert F. Wright, “Building the Oakland Temple.”

[19] Harvey, interview.

[20] Harvey, remarks.

[21] Harvey, remarks.

[22] Harvey, remarks.

[23] Harvey, interview.

[24] Harvey, interview.

[25] Nell Smith, “Temple Rises on Oakland Hill,” Church News, April 27, 1963, 9; see also “Construction Work on Oakland Temple Right on Schedule,” Church News, February 23, 1963, 5.

[26] Henry A. Smith, “As We See It . . . from the Church Editor’s Desk,” Church News, June 1, 1963, 5.

[27] Nell Smith, “Work Pressed Forward on Oakland Temple,” Church News, December 28, 1963, 8.

[28] Glen R. Nielsen, remarks, fireside in the Dublin Ward Chapel, September 30, 1979, transcription in Delbert F. Wright, “Building the Oakland Temple.”

[29] Nielsen, remarks.

[30] Carl W. Buehner, “Blessings We Receive through Membership in the Church,” in Speeches of the Year (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 1961), 3–4.

[31] Nielsen, remarks.

[32] Harvey, conversation.

[33] Wright, “Building the Oakland Temple,” 26.

[34] Nielsen, remarks.

[35] Harvey, interview.

[36] Nielsen, remarks.

[37] Nielsen, remarks.

[38] Harvey, interview.

[39] Harvey, interview.

[40] Nielsen, remarks.

[41] Wheatley, interview.

[42] Wright, “Building the Oakland Temple,” 49.

[43] Wright, “Building the Oakland Temple,” 50–51; “Another Side to Oakland Temple,” Church News, January 11, 1964.

[44] Wright, “Building the Oakland Temple,” 60.

[45] “Oakland Temple Nearing Completion,” Church News, September 12, 1964, 2.

[46] Beryl Harmon, telephone conversation with Robert Larsen, March 8, 2012.

Eventually some of the potentially affected property was purchased by the Church and has not been put to any other use.

[47] Eunice Knecht, statement to Richard O. Cowan, December 8, 2013; O. Leslie Stone, Memorandum 64-1 to Hugh B. Brown, April 11, 1965, copy in possession of Richard O. Cowan.

[48] Robert C. Loder, “Oakland Temple Cascade and Fountains,” undated typescript in possession of the authors; Wright, “Building the Oakland Temple,” 32.

[49] Wright, “Building the Oakland Temple,” 62.

[50] Harvey, interview; see also Nell Smith, “Pres. McKay Pays Surprise Visit to Oakland,” Church News, August 8, 1964, 3.