The Washington D.C. Temple: Mr. Smith’s Church Goes to Washington

Maclane E. Heward

Maclane E. Heward, “The Washington D.C. Temple: Mr. Smith's Church Goes to Washington,” in Latter-day Saints in Washington, DC: History, People, and Places, ed. Kenneth L. Alford, Lloyd D. Newell, and Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 393‒414.

Maclane E. Heward was a Seminaries and Institutes instructor and was a visiting professor at Brigham Young University when this was written.

The Washington D.C. Temple. Photo by Richard C. Clawson.

The Washington D.C. Temple. Photo by Richard C. Clawson.

Sacred space is among the most visible aspects of religion and functions as a location of interaction between believers, interested onlookers, and the divine.[1] The Washington D.C. Temple (formerly the Washington Temple) functions as a prominent and unique example of sacred space for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints because of its location in the nation’s capital. It has become a location shared by the Church and its members as well as the national and international communities located in the area. This shared location was purposefully created by the Church and has facilitated important relationships between the Church and national and international leaders throughout the world. The following pages will discuss the vision the leadership of the Church had for the temple, how interaction with God sacralized the temple and how the Church and the community have utilized the location for their own purposes. This will facilitate an understanding of the uniqueness of the Washington D.C. Temple in fulfilling its intended purposes.

The Unique Mission of the Temple

Church leaders saw the temple as not only beneficial to the membership but also as a symbol that the Church had entered a new phase of respectability. The temple was also seen as an opportunity to inform the world about the tenets of the faith. Elder Ezra Taft Benson (then of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles) and President Hugh B. Brown (of the First Presidency) both indicated that the building of the temple was a symbol that the Church had outgrown persecution. Speaking at the dedication of the ground for the temple on 7 December 1968, Benson reflected on the history of the Church in the DC area: “I thought last night . . . of the days of persecution when the Saints were being driven—many of them murdered, and their homes burned.” Along with recounting President Martin Van Buren’s famous response to Joseph Smith, Benson also discussed the Reed Smoot hearings with a sense of bewilderment that Smoot’s senate seat was called into question after he was “elected by the people of the sovereign state of Utah.” “Well, there have been great changes,” which Benson attributed partially to the specific efforts of the Saints in the DC area. “I’m so pleased,” Benson continues, “that a temple of God is to be erected in the nation’s capital, the capital of the greatest nation under heaven.” So Benson saw the temple as a symbol that the Church had overcome its persecuted past and looked forward to the continued establishment of the Church in the United States. His concluding thoughts leave little room to misunderstand that a primary benefit of the temple in Washington, DC, is for the neighbors of the Church in that area. “A temple in Washington will be inspiration not only to the Latter-day Saints, but to people of many faiths, our friends, our neighbors, and thousands upon hundreds of thousands who will come here and receive inspiration as they view this structure which will light this hill.” Benson concluded with an invitation for those present to “appreciate what this project means.”[2]

The Washington D.C. Temple and fountain. Courtesy of author

The Washington D.C. Temple and fountain. Courtesy of author

President Hugh B. Brown began his remarks at the dedication of the temple site by indicating that President David O. McKay, the President of the Church, made a special effort to ensure that a message of his love was brought to the people in the Washington area. Brown then quickly transitioned and paralleled Benson’s remarks: “To me,” he began, “this is one of the most significant moments in the history of the Church—a moment when we came back east from which we were driven years ago. . . . But now we come back and we propose to build a temple on this site—a temple to the Lord, our God. I had a thrill as I think of its significance, what it portends.” Thus, for both Benson and Brown, the temple symbolized the Church coming to a time in its development when it had overcome the persecutions of the past and was now a part of the nation. Later in his remarks Brown discussed the gospel being taken to the nations of the earth in anticipation of the day of peace. He seemed to suggest that this temple will have a significant role in that development and thanked God in the dedicatory prayer, saying, “We thank thee for what it portends.”[3] According to Brown, the temple seemed to be a significant part of that development.

President Brown made his understanding of the purpose of the temple even more clear as he invited the selected group of architects to begin their work designing the building. Keith Wilcox, one of the architects, remembered meeting with Brown and hearing Brown’s emphasis on sharing with those who would design the building the unique feelings of the First Presidency regarding this particular temple. Brown emphasized the specific “missionary impact” of the building, further stating that Washington, DC, was the capital of the country but that some viewed it as the “capital of the world.” The architecture should therefore match the intended missionary impact as well as fit in with the other architecturally significant buildings in the area. It ought to be beautiful and be a credit to the Church.[4] Though the Church leaders wanted the architecture to be meaningful and powerful, no one knew how iconic the temple would become. After the route of the Capital Beltway was finalized and before the groundbreaking, the location of the temple was adjusted sixty feet to line up perfectly with the Capital Beltway. This small adjustment has had repercussions for missionary work as many people, due to its visibility and beauty, stop by the temple seeking information about its purpose.[5]

The approach of the Church in actively seeking public participation in the events of the temple completion and open house represents a transition for the Church. Historian J. B. Haws indicated that this transition had roots at Brigham Young University. In 1969 Ernest Wilkinson, the president of BYU, faced a difficult decision to either stay quiet regarding the exploding racial conflict growing out of BYU athletics and the Church’s racial policies or to defend the university and the Church. Wilkinson accurately expressed the previous approach of the Church when he expressed worry that “our story is being told—by our detractors, by those who are uniformed, by almost everyone except us. . . . In the past our lips have been largely sealed.” Wilkinson was advised by N. Eldon Tanner of the First Presidency to use his “best judgment” in the situation. With the help of Heber Wolsey, the head of public relations for the school, the school began to tell its own story and control its own message. Though an aberration from previous patterns, this approach was incredibly successful. Wolsey, just three short years later, became the chief assistant in the newly formed Public Communications Department. This development, growing out of the newly organized administration of President Harold B. Lee, dramatically altered the public communication strategy of the Church, leaving it professionalized and progressive. The shift went from an approach of “we don’t, in effect, want media publicity to the idea that we’ll hire the best people we can possibly hire to help us with the public relations program.”[6]

The approach of the Church in introducing the temple to the community in Washington, DC, evidences this significant shift. Not only did the Church seek after the “best people” for their public relations efforts regarding the opening of the temple, but the Church sought to use the temple to proactively educate the public about its core beliefs and create relationships with key constituencies. Though the temple gave evidence for the vitality of the diaspora of Latter-day Saints and the effectiveness of the missionary program, information gathered by the newly formed Public Communications Department indicated that Americans at large did not understand who the Saints were, what the Church was, or what its doctrines were. Just before the opening of the temple, the Public Communications Department assessed the attitudes and understanding of Americans regarding the Church in six metropolitan areas. The department members’ main takeaway was summarized by Boyd K. Packer of the Twelve Apostles on one of the final pages of the report: “The problem faced by missionaries ordinarily is not opposition, but obscurity.”[7] The temple and the open house associated with it became an opportunity for the newly formed, professionalized Public Communications Department to make an impact on public perception and to try and establish “family unity” as the brand of the Church.[8] They did this, in large measure, by inviting individuals to come and experience the temple before its dedication and to feel of the power of the sacred space after its dedication through annual events. Thus visitors were welcomed to the grounds to sense the sacredness of the place, a sacredness that was manifest to and created by local members of the Church even before the final purchasing agreement was signed and the location was approved as a temple site.

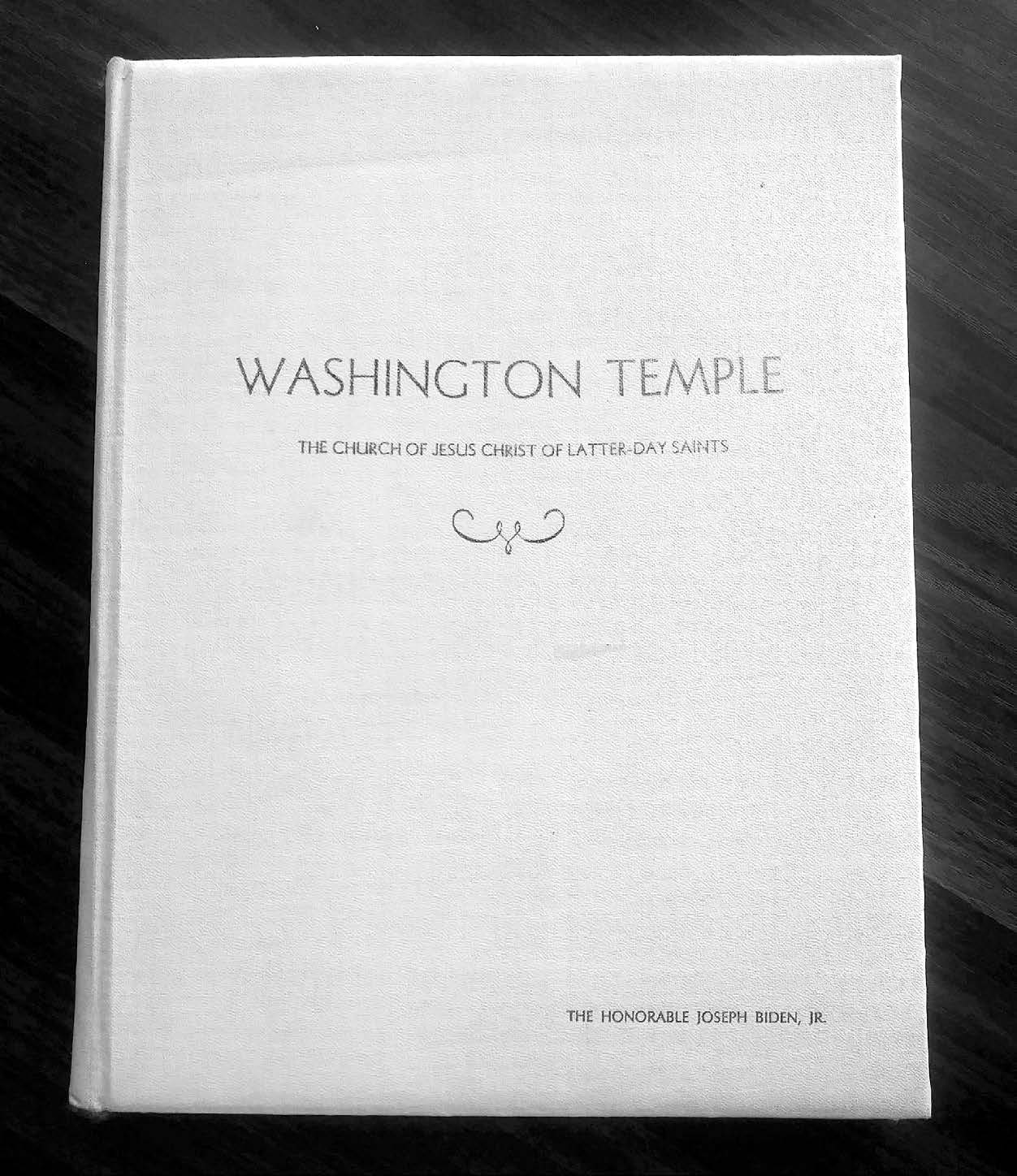

Members of the United States Senate and House of Representatives, along with many other government officials, were given special copies of a special issue of the Ensign magazine with their names embossed on the cover. Joseph Biden Jr.’s personalized copy is shown above. Photo in possession of the author. This Ensign is currently in the possession of Flora McConkie and was given to a local stake president by a member of Senator Biden’s staff.

Members of the United States Senate and House of Representatives, along with many other government officials, were given special copies of a special issue of the Ensign magazine with their names embossed on the cover. Joseph Biden Jr.’s personalized copy is shown above. Photo in possession of the author. This Ensign is currently in the possession of Flora McConkie and was given to a local stake president by a member of Senator Biden’s staff.

Making the Temple Sacred Space

What makes space sacred? Sacred space can commemorate past events, look forward to future events, or be a conscious effort to invite the sacred into a space. Sacred space is formed through the commemoration and anticipation of theophanies. Mount Sinai, the Mount of Olives, the Sacred Grove, and Adam-ondi-Ahman are examples of such spaces. Mircea Eliade, a religious historian and philosopher, suggested that if a “sacred location” is not directly attached to hallowed historic events, the performance of sacred rites and rituals can “provoke” or create sacred space. In effect, Eliade argued that men and women could create a space and, through ritual, invite God to inhabit the location. “Since religious man cannot live except in an atmosphere impregnated with the sacred,” explains Eliade, “we must expect to find a large number of techniques for consecrating space.” One such technique is engaging in ritual that “reproduces the work of the gods.”[9] Latter-day Saint theology sacralizes temples for each of these reasons: The temple is a location that both commemorates and anticipates interaction with the divine. It is a place where individuals participate in ritual to invite the divine. And men and women participate in the “work of the gods” at the temple. The following anecdotes will illustrate the unique spirit of the Washington D.C. Temple and how that connection with the divine developed through lived experience.

The location of the temple and the designation of the area as sacred space came even before the land was officially selected as the location of the temple. Initially, the land in Kensington Maryland, where the Washington D.C. Temple rests was unavailable for purchase by the Church. The eventual purchase of the land was a result of a mutual understanding and respect for sacred space shared by Latter-days Saints and Jews. For many Church members who understand the details, the acquisition of the land for the temple illustrates God orchestrating and facilitating the accomplishment of his will.

In 1962 the title to the coveted land was owned by a group of investors who authorized three of its group to proceed with negotiations for the sale of the property.[10] Renowned lawyer and local Church leader Robert Barker was given approval by Church leadership to purchase the land. Barker was met with repeated rejection as the sale of the land was already being negotiated for by a real estate developer who wanted to build homes on the property. The investors had given their word that the land would be sold to the developer. In a moment of despair, Barker expressed his frustration to his wife, Amy, and explained that he felt strongly that the temple needed to be in this particular location, but it seemed the way was being hedged up. At this point in time, the Capital Beltway had been approved, but the plans and location were not finalized. Amy’s response to her husband’s frustrations and determinations was to direct him to tell the investors exactly what temples mean to Latter-day Saints and why it was so important that this spot of land be purchased. Barker decided to make one final attempt, asking one of the three leading investors to have lunch with him. This investor flatly refused and indicated that the land was not for sale. Barker, in an act of desperation, promised the investor that if he would come to lunch and hear what he had to say, Barker would never contact him again; this was just the motivation the investor needed!

During his lunch with this Jewish investor, Barker sought to build on common ground and to speak from his heart. He connected the love Latter-day Saints feel about the temple with the temple-building tradition of the Jewish people. Barker assured the investor that the temple ceremonies that Latter-day Saints participate in have similarities with the ceremonies with which the Jewish people were familiar. In the end, Barker shared the Church’s doctrine about temples and the Church’s commitment to building them in a personal, heartfelt way. The end of the lunch left Barker uncertain about the impact of his attempt, but that uncertainty did not last long. Just two hours later, the investor called Barker to indicate that the requested land would be sold to the Church. The investors decided that to stand in the way of a religious group wanting to build a house to God would not align with the individual beliefs of the investors, who were significant contributors in the Zionist movement.[11]

Years later when Diane Holling, a DC-area architectural student, was tasked with collecting historical documents regarding the temple, she interviewed the two surviving Jewish investors and found that if Barker’s final plea would have been three days later, the land would have been tied up in the purchasing process and unavailable for the Church. Utah senator David S. King, former president of the Washington D.C. Temple and author of Come to the House of the Lord, concluded his summation of this story by declaring that in the details of the acquisition of the land, “the hand of the Lord was felt in the accomplishment of his purposes.” King remembered that at the dedicatory service, President Spencer W. Kimball “declared . . . that the selection of the temple site . . . had been inspired of God.”[12] Thus Saints interpreted the purchasing of the land as a moment in which they were working with God to bring about his purposes, a work that helped make the temple sacred space.

The development of the architectural plan for the temple also evidenced God’s hand. Keith Wilcox remembered the significant emphasis President Brown placed on the shoulders of those who were assigned to design the building. The temple was to be a symbol of the Church and its presence in the nation and the world. Along with his emphasis on the reality that the temple structure ought to fit the purpose and missionary aims of the Church, he added one final measure of importance to the project by indicating that President David O. McKay had a “keen interest in this project.”[13]

The men immediately began holding meetings to solidify the plans for the temple. In a meeting on 5 February 1969, one of the architects chided Wilcox for not yet submitting a drawing of the temple to the committee for consideration. Knowing the significance of the task, Wilcox cleared his schedule that Friday and Saturday and commenced the creation of a plan. “As I sat and pondered this challenge, I decided to make the problem a matter of deep, personal prayer.” The inspiration that came to him came in the form of a single word: “enlightenment.” Unaware of the time, Wilcox worked through the night, recalling that ideas “seemed to flow out of my fingertips without effort,” visualizing the building’s appearance even before drawing it. “I began to feel a great surge of the Spirit and a creative desire. It was a glorious feeling. I felt as if I were being lifted up; my mental faculties sharpened. I lost awareness of where I was. Truly, I felt full of ‘enlightenment.’ My mind and spirit were in tune with the challenge. A power beyond my own gave me strength.”[14] At one point, Wilcox explained that he almost felt that he was in the presence of “Heavenly Beings.”[15] He was deeply humbled by the experience and professed that the inspiration of heaven brought about the temple design. The building therefore came to represent for Wilcox a visible reminder of a sacred moment when he felt that God had parted the heavens and inspired an architect to create his house. Wilcox had participated in the “work of the gods.”[16]

The sacrifice of individual members in donating money for the Washington D.C. Temple also helped to sacralize the edifice. During this time, members of the Church who would benefit from the construction of new buildings were asked to financially contribute to a building fund.[17] For the temple, members were asked to contribute more than four million dollars. Nicholas Perry, a wealthy convert, became the first to donate to the temple building funds. Perry had moved to Eastern Europe with his company before WWII commenced. During the war, Perry’s business was confiscated by the Nazi Regime in Eastern Europe, and he and his family fled for their lives back to the United States. Perry had received funds from the Alien Property Custodial Act but donated the funds to the building of the temple instead.[18]

Other anecdotes illustrate the degree to which the Washington D.C. Temple was sacralized in the minds of the Latter-day Saints. Marsha Sharp Butler and her husband, Karl D. Butler, were able to attend the temple dedication ceremony and described it as a magnificent experience. Marsha expressed her feelings that the temple had a special aura around it and that she “just knew that it was a special place and that it was meant to be there at that particular time.” After attending the temple dedication, Karl and Marsha noticed that a Brother Zimmer, a member of their local congregation, looked as if he was having a difficult time walking to his car from the temple. His walking was so labored that he needed assistance from his family, something unusual for Brother Zimmer. The next week at their local meetings, Marsha was informed that Brother Zimmer had experienced a theophany while in the temple. This experience further sacralized the temple for the Butlers. Later, when Karl was preparing to participate in ordinances in behalf of his deceased grandfather, his grandfather appeared to him as if to verify to Karl that the work he was doing was exactly what God and his grandfather wanted. These experiences bound the Butlers’ hearts to this location as a sacred place where God manifested himself to his people.[19]

The Butlers’ experiences are not unique. Other oral histories mention the realities of visitations or experiences where individuals felt the presence of those who had died. Doreen Taylor and her husband, Bramwell, went to the Washington D.C. Temple to be sealed. Because they were living in New Brunswick, Canada, they stayed in a hotel and spent a few days participating in ordinances for their deceased ancestors. While Doreen participated in the initiatory ordinances for her mother and grandmother, she “knew” that they had accepted the gospel, and she felt that they were by her side. She reported that all who were helping her through these ordinances were emotional, and, to this day, she still gets emotional thinking about the experience.[20]

Harold Ranquist, a local member who worked on the temple and served at that time as a major in the Army Reserves, believes God miraculously provided a miracle that facilitated the opening of the temple open house. At the last minute, the day before President Gerald Ford, his family, his cabinet, and many foreign diplomats were scheduled to attend the temple open house, the fire marshal refused to allow the open house to take place unless a separate emergency standby generator was ready to operate the sprinkler fire-suppression system in the event of a power outage. Having connections with military personnel in the area, Ranquist spent eight hours on a Sunday calling his military connections, including vacationing generals, to locate a generator that could be borrowed. As attendance was limited, virtually everyone that he spoke to asked for tickets to the open house. After significant effort, a generator was found and arrived on location just twenty-five minutes before the open house’s scheduled starting time. After connecting the generator to the building systems and receiving the approval of the fire marshal, the open house began with minutes to spare. “That day,” recalled Ranquist, “30 tickets were committed to the various colonels and generals with whom I had spoken. I have received several letters of appreciation from them commenting on their excellent experience and thanking me for making it possible.”[21] In Ranquist’s mind, God had provided a miracle that further facilitated the sacralization of the temple and an understanding that the Saints were engaged with God in sharing the temple with their neighbors.

Inviting Their Neighbors to Experience Sacred Space

President Gerald Ford and First Lady Betty Ford talk with President Spencer W. Kimball and Sister Camilla Kimball at the Tabernacle Choir concert held in the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in conjunction with the dedication of the Washington D.C. Temple and open house. Kimball–Ford Photos, Church History Library.

President Gerald Ford and First Lady Betty Ford talk with President Spencer W. Kimball and Sister Camilla Kimball at the Tabernacle Choir concert held in the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in conjunction with the dedication of the Washington D.C. Temple and open house. Kimball–Ford Photos, Church History Library.

The Church organized an executive committee to plan and carry out activities designed to allow the members of the Church and the public to learn about and experience the sacred space of the temple. This helped accomplish the leadership’s vision for the temple. The following anecdotes illustrate the Church’s deliberate efforts to invite key constituencies to experience the temple and also show the impact of the Church’s efforts. The committee orchestrated four main planned events to accomplish their purpose. They first facilitated completion and cornerstone-laying ceremonies. Next, they held an exclusive temple preview in which special guests participated in a tour of the interior of the temple. The invited guests included all General Authorities and local church leaders, the president of the United States and the White House staff, all members of the Senate and House of Representatives, the Supreme Court justices, and national and international leaders and their spouses.[22] To the third event, the public preview, which was originally scheduled for four weeks, was extended an additional two weeks, which resulted in more than 215,000 additional attendees. In all, more than 758,000 people attended the temple open house, more than all previous temple open houses combined, a reality that partially evidences the contributions brought about through the Church’s Public Communications Department.[23] Tickets to attend the open house, according to Christianity Today, became “as scarce as those for the home games of the Washington Redskins football team.”[24] The dedication was the final event and included ten dedicatory sessions, with each session accommodating 4,200 individuals.[25]

President Gerald Ford and his wife, Betty, were scheduled to attend the open house on the first morning of the special preview. Due to unforeseen circumstances, President Ford was required to reschedule his attendance, but the First Lady reported having an excellent experience.[26] Upon leaving the temple, Mrs. Ford gave a statement to the press in which she indicated that the open house was a wonderful experience for her and that the temple was “one of great beauty and a great addition to our surroundings here in Washington.” She then explained that the temple “is really an inspiration to all of us. I don’t know when I have enjoyed anything quite so much.” Mrs. Ford also complimented the Church on allowing individuals to tour the building, saying that the Church was “very generous letting us attend and having it open to the public before they have their own services.” She concluded with the statement that the Church’s actions “shows a great generosity on their part.”[27] Mrs. Ford’s focus on the inspiration that the temple provided to all and the great generosity of the Church in allowing individuals to participate evidences the goodwill built through the efforts of the Church.

First Lady Betty Ford signs the temple open house guest book with Sister Kimball and President Kimball. Kimball– Ford Photos, Church History Library.

First Lady Betty Ford signs the temple open house guest book with Sister Kimball and President Kimball. Kimball– Ford Photos, Church History Library.

The experiences in the temple facilitated further interactions between the Church leaders and the First Lady. As President Kimball and other political and religious leaders escorted the First Lady and some of the White House aides through the temple, they explained that the ordinances of the temple required preparation and therefore admittance to the temple was limited. While in the solemn assembly room, that Betty Ford asked how temple officials were able to distinguish between those who were prepared and those who were not. As one of the party explained that each individual who met the qualifications was given a “recommend,” Senator Wallace Bennett took out his recommend and showed it to Ford. One by one, each individual in the group leading the tour showed his or her recommend, except for President Kimball who rifled through his wallet three or four times before finally finding his recommend. Ford, with some mischief in her voice, said, “I’m so glad you’ve got one, too. You had me worried.”[28] Interactions like this removed barriers and created friendships with national influencers.

Other governmental leaders expressed similar feelings to Ford’s at the conclusion of their tours. Supreme Court justice Warren E. Burger remarked that the temple “certainly will be a tremendous addition to the great religious monuments of Washington along with the other great cathedrals that are here.” Maryland governor Marvin Mendel said, “I think the temple itself is probably one of the most beautiful buildings I have ever seen in my life, and we are absolutely delighted that it is located here in Maryland. It certainly adds something to our state.”[29]

The temple attracted widespread favorable publicity across the nation from news organizations, churches, and church members.[30] The National Catholic News Service issued a news release that in part read the following: “In the Temple which bears the Mormon name, Catholics and members of many other faiths will be getting a rare insight during the weeks ahead of how another religion is practiced. It will be a fascinating discovery.” In addition to these encouraging remarks, the news release attributed sacred meaning to the building, saying, “the three-story celestial room stands as a symbol of the exalted state [men and women] may achieve through the gospel of Jesus Christ.”[31] A Methodist woman remarked on the feeling in the temple by saying, “It is a place of worship, and of course we worship the same God, and we worship the same Christ. For that reason I felt a worshipful attitude as I walked through the temple today.”[32]

The temple open house clearly made an impact on visitors, as was evidenced with the number of individuals who requested additional information. As part of the tour, participants were handed a card that they could fill out if they desired additional information. Some 15 to 20 percent of visitors returned the cards to request additional information, a significant figure, said one of the missionaries involved, when one “considered that most persons who filled out cards brought their whole families with them.”[33]

The temple continues to be a location that the Church uses as a way of building goodwill. Just a few years after the temple was completed, the Church organized its first Festival of Lights at the adjacent visitors’ center. Each year since 1978, the Church has invited ambassadors from across the globe who are in Washington, DC, to participate in the temple Christmas lighting ceremony. One ambassador is selected to give remarks and to turn on the Christmas lights. These experiences have promoted significant understanding and have created relationships and opened doors for the Church. Utah senator Orrin G. Hatch has attended many of these events being that he arrived in Washington the year before the lighting ceremonies began. Hatch described the benefit of these ceremonies by recalling an experience he had with the Russian delegation that had been invited to the temple lighting ceremony. Hatch indicated that a few days after the ceremony, the Russian ambassador took the chance to meet with Hatch and ask him questions regarding the Church, allowing Hatch to share general information about the Church and its desire to strengthen families and nations. Hatch expressed that these relationships have benefited the Church and even helped to facilitate countries being willing to officially receive the Church.[34]

President Spencer and Camilla Kimball talk with First Lady Betty Ford on the grounds of the Washington D.C. temple after Ford completed a tour of the Temple, 12 September 1984. Kimball Ford Photos, Church History Library.

President Spencer and Camilla Kimball talk with First Lady Betty Ford on the grounds of the Washington D.C. temple after Ford completed a tour of the Temple, 12 September 1984. Kimball Ford Photos, Church History Library.

The lighting ceremonies helped to create a situation in which relationships were formed in natural and significant ways. In 1998, for example, the Deseret News began an article about the Festival of Lights at the Washington D.C. Temple by saying, “Not many years ago, few would have dared imagine a high official of China publicly praising The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, embracing a general authority and inviting the church to work more with his Communist country. But the impossible dream of Cold War years was a reality Wednesday as Li Zhaoxing, ambassador to the United States from the People’s Republic of China, did all of that.” The article indicated that Senator Hatch introduced the ambassador and that Zhaoxing, after the kind introduction, hoped that all those “good words were overheard by God and by my boss.” The article concludes by indicating that over the past decades, the ambassadors that have been honored in the tree lighting ceremonies have “later helped open the doors to LDS missionary work in their nations—including numerous formerly Communist countries.”[35] Clearly, from these experiences, the temple has become a location from which the Church has symbolically stated that they are a permanent part of the national and international religious marketplace.

The temple has also become a location for comedic and political commentary. One early news article suggested that the temple looked like a “bleached Emerald City of Oz.”[36] Even before the dedication of the temple, a comedic artist created a signage on one of the underpasses approaching the temple that read “Surrender Dorothy.”[37] Some thirty-four years later, a similar sign appeared with comedic value and political motives. The vandalism came at the end of a week in which President Donald Trump’s former campaign manager was convicted of eight felony counts and his former attorney pled guilty to campaign finance violations. The sign read simply “Surrender Donald.”[38]

The temple is an accepted part of the landscape of the DC area and a landmark to which individuals are drawn. This is a calculated and intended outcome driven by the desire of Church leaders to create a place in which national and international leaders may feel the spirit of the place and create relationships of mutual respect and understanding. This location is a significant place to help the Church overcome “obscurity” and positively impact the Church’s missionary efforts. Thus it is not unusual to have individuals enter the visitors’ center indicating that they have long seen the temple on their commute and have finally come for information. Likewise, a picture of the DC metropolitan area phone book even donned a picture of the temple on its cover.[39] The related experiences have shown that the Church consciously used the temple to create relationships with national and international leaders and the local public. In large measure, the tactics of the Church have succeeded in showing that the Church has come to stay, both nationally and internationally.

Notes

[1] Alonzo L. Gaskill, “Religious Ritual and the Creation of Sacred Space,” in Sacred Space, Sacred Thread: Perspectives across Time and Tradition, ed. John W. Welch and Jacob Rennaker (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2019), 103.

[2] Ezra Taft Benson, “Remarks at the Washington D.C. Temple Site Dedication,” 7 December 1968, CR 633 1, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Hugh B. Brown, address, 7 December 1968, photocopy of typescript, MS 3305, Church History Library.

[3] Hugh B. Brown, address, 7 December 1968, photocopy of typescript, MS 3305, Church History Library, 1–4.

[4] Further illustrating the leadership’s emphasis on using the temple to take the message of the restored gospel not only to the nation but to the world, a radio broadcast in 1972 called “The World of Religion” reported a Church spokesmen as saying, “We have a message for the world. We want the world to hear it. We want the world to have the opportunity of understanding the gospel—the Restored Gospel. We are happy to attract people to our message. We hope the design does attract a great deal of attention so people will investigate the Church.” Clearly the target audience went far beyond the nation. As quoted in Keith W. Wilcox, The Washington DC Temple: A Light to the World (Kensington, MD: self-pub.,1995), 5, Church History Library. Stewart M. Hoover, a professor of religion and media studies, indicated that “The World of Religion” radio broadcast was, in 1998, America’s longest-running radio broadcast focused on religion. It was produced at KMOX in St. Louis. Stewart M. Hoover, Religion in the News: Faith and Journalism in American Public Discourse (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 1998), 156.

[5] Mark Garff, Church Building Committee chair; Emil Fetzer, Church architect; and Tim Timmerman, construction architect, were the architects who made the adjustments to the location of the temple by sixty feet. These adjustments were made during the planning phase, before the commencement of construction. Diane L. Holling, interview by Maclane Elon Heward, 10 and 12 July 2019.

[6] The campaign consisted of radio appearances, campus visits and traveling presentations among other things. J. B. Haws, The Mormon Image in the American Mind: Fifty Years of Public Perception (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 62, 75.

[7] “Attitudes and Opinions Towards Religion: Religious Attitudes of Adults (over 18) Who Are Residents of Six Major Metropolitan Areas in the United States: Seattle, Los Angeles, Kansas City, Dallas, Chicago, New York City—August 1973,” 33, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. See also Haws, Mormon Image, 76–77.

[8] Orson Scott Card, “Wendell Ashton Called to Publishing Post,” Ensign, January 1978, 73–4. “Attitudes and Opinions Towards Religion,” 33. See also Haws, Mormon Image, 76–77. A number of factors led to the flood of curious visitors during the open house. The Church had been in the news at an unprecedented rate in the previous five to seven years for things like the death of President David O. McKay, George Romney’s presidential campaign, and the protests directed at BYU regarding the Church’s racial policies. The excitement around the Church at the end of the 1960s and into the 1970s coincided with the Church’s participation in the New York World’s Fair, a success that convinced Church leaders of the untapped potential of outreach on a grander scale. The result was the replacement of the Church Information Service with the Public Communications Department. The leader of the newly formed communications department, Wendell Ashton, was an advertising executive and a journalist. He pulled Heber Wolsey (BYU’s public relations officer who had played a significant role in the proactive stance of the university in the protests at the turn of the decade) into the newly formed organization as Ashton’s chief assistant. See Jon Ben Haws, “The Mormon Image in the American Mind” (PhD diss., University of Utah, 2010), 170–76. Wolsey’s graduate training and professional experience centered in radio and television broadcasting. Between the two, the culture of the department was set. Ashton reported that the “whole thrust of our department was to take the initiative and not wait to respond to people seeking information.” See Wendell J. Ashton oral history, 1984, 173, Church History Library, as cited in Public Affairs Department, unpublished departmental history, cited in Haws, Mormon Image, 77.

[9] Mircea Eliade, Sacred and Profane: The Nature of Religion, trans. Willard R. Trask (Orlando: Harcourt, 1957), 28–29; emphasis in original. Sacrifice can also create sacred space. Members of the Church were asked to raise significant funds for the building of the temple ($4.5 million). Frank Miller Smith, “Monument to Spirituality: Sacrifice, Dreams, and Faith Build the Washington Temple,” Ensign, August 1974, 8.

[10] Wilcox, Washington DC Temple, 5.

[11] David S. King, Come to the House of the Lord (Bountiful, UT: Horizon, 2000), 12–14. See also Holling, interview, 10 July 2019.

[12] King, Come to the House of the Lord, 12–14. See also Holling, interview, 10 July 2019.

[13] Wilcox, Washington DC Temple, 5.

[14] Wilcox, Washington DC Temple, 9–10.

[15] Wilcox, Washington DC Temple, 13.

[16] Mircea Eliade, Sacred and Profane, 28, 29. The temple rests on forty-eight concrete caissons, which were sturdy enough to help the temple withstand a 5.8 magnitude earthquake forty miles northwest of Richmond, VA, in 2011. Though minor damage occurred, the temple remained open. See Joseph Walker, “‘Minor Damage’ to D.C. Temple in Earthquake,” Deseret News, 24 August 2011.

[17] During his brief remarks at the dedication of the land for the temple, Hugh B. Brown voiced his opinion that he hoped the Church never stopped asking the members to help pay for buildings. He clearly recognized the benefits to the membership of the Church in sacrificing to create sacred space. He also shared his own experiences sacrificing to contribute to Church buildings. Hugh B. Brown, address, 7 December 1968, photocopy of typescript, Church History Library.

[18] Smith, “Monument to Spirituality,” 8.

[19] Marsha S. Butler, oral history, interview by Karl D. Butler Jr., Salt Lake City, 25 April 2014, Church History Library.

[20] See Bramwell W. Taylor and M. Doreen Taylor, oral history, interview by Arnon Livingston, New Brunswick, Canada, 12 August 2014, Church History Library.

[21] See Harold Alexander Ranquist, reminiscence, 1999, typescript, Church History Library.

[22] Special guests were given a special edition of the Ensign magazine with their names embossed on a special cover. The author is in possession of a picture depicting the cover of one magazine embossed with “THE HONORABLE JOSEPH BIDEN, JR.”

[23] “Washington Temple: Missionary Tool,” Ensign, December 1974, 73.

[24] See Harold Alexander Ranquist, reminiscence. For the citation regarding the Washington Redskins, see Edward E. Plowman, “Ford’s First Month: Christ and Conflict,” Christianity Today, 27 September 1974.

[25] Jesse R. Smith, “Washington Temple,” in History of the Mormons in the Greater Washington Area: Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the Washington, D.C. Area, 1839–1991 (Washington, DC: Community Printing Service, 1991), 168.

[26] For information regarding President Gerald Ford’s attendance at the temple open house, see Edward L. Kimball and Andrew E. Kimball Jr., Spencer W. Kimball: Twelfth President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1977), 419.

[27] “Statement of Mrs. Betty B. Ford to the Press, 11 September 1974, upon leaving the Washington Latter-day Saint Temple, 11 September 1974,” typescript, Church History Library.

[28] Jesse R. Smith, “Washington Temple,” 169. See also Holling, interview, 10 July 2019.

[29] The Washington Temple: A New Landmark (video), Church History Library.

[30] Richard O. Cowan, Temples to Dot the Earth (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, 1997), 177. The open house also attracted widespread publicity. Favorable articles appeared not only in national periodicals but also in newspapers in all fifty states and abroad. Surprisingly, controversies relative to the Church from just a few years previous were either not mentioned or mentioned only obscurely. See Haws, Mormon Image, 70–71.

[31] Tom Lorsung, “Mormon Temple Tour Is a Rare Insight,” Catholic Research Resources Alliance, Catholic News Service-Newsfeeds, 5 September 1974.

[32] The Washington Temple: A New Landmark (video).

[33] “Washington Temple, Missionary Tool,” Ensign, December 1974, 73–74.

[34] Orrin G. Hatch, interview by Maclane Heward, Salt Lake City, 29 May 2019.

[35] Lee Davidson, “Chinese Envoy Illuminates D.C. Temple: He Offers Warm Praise for the LDS Church,” Deseret News, 3 December 1998.

[36] “Behind the Temple Walls,” Time, 16 September 1974, 110.

[37] “Wicked Witch of the Beltway?” Montgomery Journal, 31 October 1974.

[38] John Kelly, “‘Surrender Donald’: A Highway Overpass along the Capital Beltway Goes Political,” Washington Post, 24 August 2018.

[39] John Laing, interview with Maclane Heward, Salt Lake City, 1 March 2019.