The Washington Chapel: An Elias to the Washington D.C. Temple

Alonzo L. Gaskill and Seth G. Soha

Alonzo L. Gaskill and Seth G. Soha, “The Washington Chapel: An Elias to the Washington D.C. Temple,” in Latter-day Saints in Washington, DC: History, People, and Places, ed. Kenneth L. Alford, Lloyd D. Newell, and Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 367‒92.

Alonzo L. Gaskill was a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published. Seth G. Soha, an alumnus of Brigham Young University, was a practicing physician assistant and an independent researcher when this was published.

The Washington Chapel. L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

The Washington Chapel. L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

The original Washington Ward’s chapel is unique among meetinghouses in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. From its architecture to its history, the chapel stands out as one of the most distinctive Church buildings constructed since the restoration of the gospel began.[1]

Prior to 1920, there was no “formal organization” of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—no wards or stakes—in the DC area.[2] The few Latter-day Saints who lived and worked in DC met on Sundays in homes or other buildings—but not as an organized branch of the Church.[3] When Elder Reed Smoot of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles became a U.S. senator (in 1903), his move to DC made him the de facto leader of the few Latter-day Saints living in that part of the world.[4] As numbers increased, and as members could no longer all meet in a living room or hotel room, the Church began renting various properties in the DC area so that members could comfortably gather together in one place to worship.[5] Starting in May 1920, the Washington Branch was officially organized—with an average Sunday attendance of somewhere between fifty and sixty members.[6]

Robert M. Stewart, son-in-law of Elder George Albert Smith (of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles), was the impetus behind getting a chapel built in DC. As he walked to work each day, he would pass the vacant lots (on Sixteenth Street) on which the Washington Chapel would eventually be built, and he was consistently impressed with what an ideal location that would be for the Church’s first chapel in Washington.[7] Elder Smith approached President Heber J. Grant about this and also encouraged Robert Stewart (who had previously worked in real estate) to make inquiries with regard to what it would cost to acquire the lots.[8] When Mary Foote Henderson—the wealthy widow of former Missouri senator John B. Henderson—learned that someone was interested in purchasing the two adjoining lots, she quickly purchased them.[9] Mrs. Henderson owned a significant amount of property in the area and thus was “quite anxious to control whatever buildings” might be erected in the vicinity.[10] Robert Stewart, on behalf of the Church, met several times with Mary Henderson in an effort to convince her to sell the lots. After several meetings, she made a verbal agreement to let the Church purchase the properties, as the following source relates:

According to Brother Stewart, when Mrs. Henderson told her architect, a Mr. Totten, that the Mormon Church was the purchaser of the lots, “he told her the sale was a mistake, that a Mormon Church in that vicinity would tend to depreciate the value of all property in the neighborhood, and foreign governments would refuse to rent her properties then used as embassies.” This was particularly important to Mrs. Henderson because she wanted to make 16th Street the most beautiful neighborhood in the city. She likewise told William Corcoran Hill, the real estate man, who became enraged and threatened to stop the sale if possible.

So, when Brother Stewart returned to Mrs. Henderson with the final form of the contract to be signed, she had to admit that she was sorry she had sold the property to the Mormon Church. Yet it remains to her credit that she kept her oral promise to them and signed the papers.[11]

It is said that, upon learning of the interest of the Church in the property, “a delegation of Protestant ministers” approached Mrs. Henderson in an attempt to discourage her from selling it to the Church.[12] Despite the very strong admonitions against selling the property to the Latter-day Saints (which she received from seemingly all sides), Mary Henderson moved forward with the deal for two primary reasons. First, because of her very “high regard for Senator [Reed] Smoot.”[13] Second, because of the Church’s position on the Word of Wisdom. (Mrs. Henderson was strongly against the use of tobacco and alcohol—and Senator Smoot is said to have explained the Word of Wisdom to her.)[14] In addition to Mrs. Henderson’s two lots (purchased on 9 April 1924[15] ), the Church also purchased a third lot (which adjoined the other two on their south sides) on 9 April 1930.[16] On the combined 18,300-square-foot property, the Church would build its first chapel in DC.[17]

In many ways, this chapel would stand as a symbol to the people of Washington that truth had been restored and that the gospel of Jesus Christ was taking root in the nation’s capital.[18] Not everyone was thrilled about that message or the building that would symbolize it. Thus, shortly before construction began on the new building (in December of 1930), a group of investors approached the Church—offering to purchase the combined lots for forty thousand dollars more than the Church had paid for them; this, in an apparent last-ditch effort to keep the Church from having a building in the upscale neighborhood. President Heber J. Grant’s “curt response,” sent via telegraph, was simply this: “Property not for sale.”[19]

The groundbreaking for the Washington Chapel was held on 13 December 1930.[20] The cornerstone was laid on 21 April 1932. The capstone atop the spire was placed on 21 March 1933. And, finally, the building was dedicated by President Heber J. Grant on Sunday, 5 November 1933—with the entire First Presidency and five members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles present.[21] Considering the tenuous relationship between the Church and the U.S. government during the nineteenth century, the construction and ultimate dedication of this edifice was a significant symbolic statement.

Stained glass window of Book of Mormon temple in the Washington Chapel. Photo by Richard J. Crookston.

Stained glass window of Book of Mormon temple in the Washington Chapel. Photo by Richard J. Crookston.

The new building had a number of unique features that set it apart from other nearby buildings and from other houses of worship built by the Church. The Washington Chapel has the singular honor of being the first building ever built with travertine, or what is commonly referred to as “birdseye marble,” that was taken from the Mount Nebo Quarry.[22] The beauty of this substance is that “at different times of the day [it] reflects various hues. After a heavy rain the effect is that of highly polished marble which changes, as it dries, into [a] hazy purple.”[23] The disadvantage is that it is a porous substance and thus not ideal for the humid climate of DC, thereby causing it to severely deteriorate over time.[24] On the north, south, and east sides of the chapel, there are also nine beautiful stained glass windows—unique to that building.[25] They depict various scenes in Church history, including the Hill Cumorah (where the plates of the Book of Mormon were buried), the migration of the Saints westward, and even ancient temples of the Western Hemisphere.[26]

The Torleif Knaphus angel Moroni statue being prepared for placement atop the spire of the Washington Chapel, where it was displayed from 1933 through 1976. L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

The Torleif Knaphus angel Moroni statue being prepared for placement atop the spire of the Washington Chapel, where it was displayed from 1933 through 1976. L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

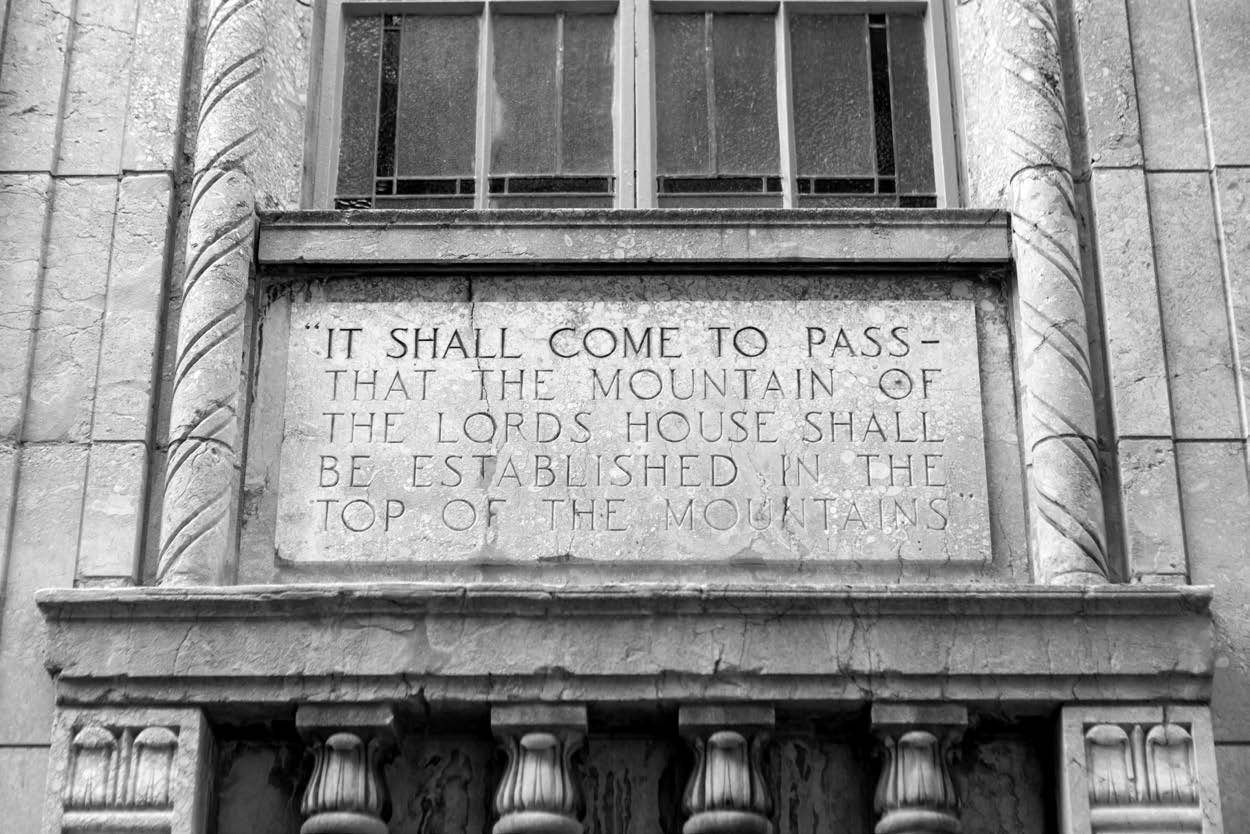

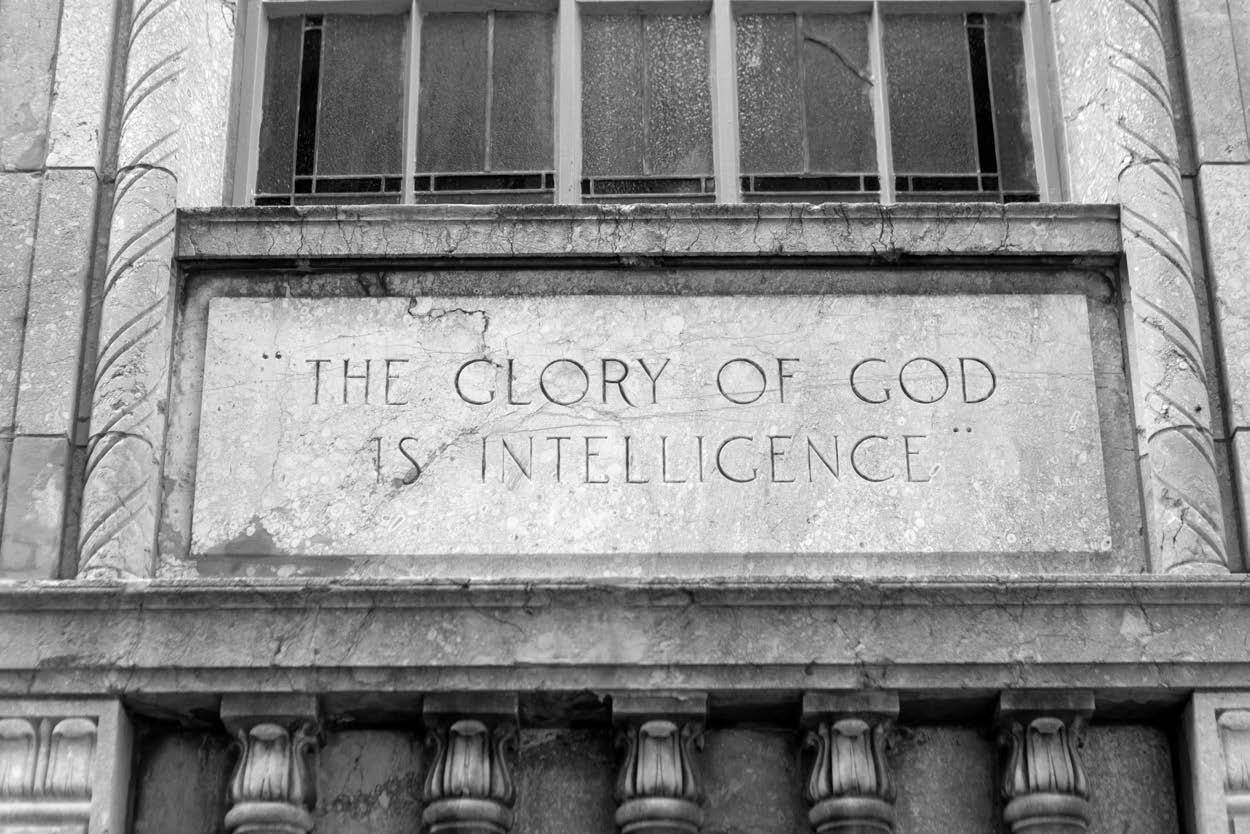

To some outside of the Church, the Washington Chapel was perceived as “the ‘Mormon Temple’ in Washington, D.C.”[27] Architecturally, many have noticed the design parallels between the chapel and the Salt Lake City Temple.[28] For example, the Washington Chapel’s singular 160-foot spire is remarkably similar in its design to the Salt Lake Temple’s six spires.[29] Indeed, one source states, “The chapel’s tower intentionally echoes the style and image of the six virtually identical towers on the Salt Lake City Temple, offering an architectural and cultural connection between the two buildings.”[30] The building has the unique distinction of being the only Sunday house of worship to ever have an angel Moroni atop its tall spire.[31] The Washington Chapel’s Moroni was similar to the angel Moroni statue atop the Salt Lake Temple and was sculpted by Torleif Knaphus.[32] Like many temples of the Restoration (including the Washington D.C. and Salt Lake Temples), the Washington Chapel faces east.[33] One source noted, additional “elements” on the Washington Chapel “recalling the [Salt Lake] Utah temple are the book and scroll design on the tower, urns, round arched windows, and the spire terminating in a ball, on which stood the figure of the angel Moroni.”[34] Elsewhere we read, “The [chapel’s] tower has two arched rectangular windows with a small vertically oriented oval window on each of its four elevations. . . . These openings . . . are mainly decorative and reminiscent of the windows found on the Salt Lake Temple.”[35] On the building’s exterior are engraved a number of inscriptions, including the words of Isaiah 2:2, Psalm 85:11, and the declaration of Doctrine and Covenants 93:36, “The glory of God is intelligence”—which is also inscribed over the doorway to the celestial room of the Mesa Arizona Temple.[36] Like the various temples of the Church, the Washington Chapel had a cornerstone ceremony during which certain items were placed in the cornerstone prior to it being sealed.[37] The placement of the Washington Chapel also seems to mimic the Church’s approach to placing their temples in conspicuous locations and, often, on elevated lots. For example, one source pointed out, “The [Washington] temple is located in Kensington, Maryland, just north of Washington, D.C., and is on top of the wooded hill in a beautiful suburban section.”[38] The Washington Chapel was also built “on one of the higher elevations of the city (two hundred feet above the base of the Washington Monument).”[39] Even the fact that the President of the Church signed off on the design of the Washington Chapel seems parallel with latter-day temples—since individual chapels do not traditionally need the approval of the prophet.[40]

Isaiah 2:2 carved on one of the exterior walls. Photo by Richard J. Crookston.

Isaiah 2:2 carved on one of the exterior walls. Photo by Richard J. Crookston.

Doctrine and Covenants 93:36 carved on an exterior wall. Photo by Richard J. Crookston.

Doctrine and Covenants 93:36 carved on an exterior wall. Photo by Richard J. Crookston.

A number of elements associated with the dedication of the Washington Chapel seem reminiscent of a temple dedicatory service. First, the entire First Presidency and five members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles attended and spoke at the dedicatory sessions—something that is simply unheard of as it relates to the dedication of a ward meetinghouse.[41] The President of the Church dedicated the building; again, a rarity for local chapels—and, in doing so, he used language that has been used in other temple dedicatory prayers.[42] After the dedicatory prayer, the choir sang the “Hosanna Anthem,” which happens to be the song composed for and sung at the dedication of the Salt Lake Temple.[43] In addition, during the dedicatory services, the congregation sang “The Spirit of God,” which was sung at the dedication of the Kirtland Temple.[44] Finally, there were three different dedicatory services held for the Washington Chapel; again, something the Church typically only does for the dedication of a temple.[45]

Like the Washington D.C. Temple that would follow it, the chapel was unique enough that it drew the attention of those who passed by. For example, one non–Latter-day Saint source—speaking of the chapel’s unique architecture—noted that “the golden figure on the spire . . . bids us pause for reflection.”[46] Unquestionably, “there was . . . an evangelical [or missionary] component to the building. . . . The exterior may be viewed in this light as well (attracting curious passers-by).”[47] In addition to the focus on the redemption of the dead and salvific ordinances for the living, temples often serve a missionary purpose. Their unique design and manicured grounds consistently draw the attention of those who are unfamiliar with the Church. The Washington Chapel is known for having this same effect. Once dedicated, it became a “beehive of missionary activity.”[48] Church members perceived the chapel as a sort of “showplace” that would draw nonmembers in and would provoke curiosity about the Church and its teachings.[49] The 5,000-plus pipe organ and its regular recitals, for example, facilitated the missionary work the building was designed to provoke.[50] “Elder [Edward P.] Kimball played organ recitals nearly every night except Sundays, giving 1001 recitals between November 5, 1933, and March 15, 1937, which 45,000 persons had enjoyed, and by his lovely music and spoken presentations learned of the Gospel and the history of the Church.”[51] The staff from various countries’ embassies would be invited to the building on specific nights during which Kimball would give “special recitals of the music of their own country.”[52] This served as a strong draw, bringing members of other faiths into the building every week. Elsewhere we read, “Following the organ recitals and after each of the regular meetings, tours were conducted throughout the chapel, which had become a major sight-seeing attraction of the city.”[53] Like many of the Church’s temples throughout the world, the Washington Chapel even had as part of it a bureau of information—akin to a visitors’ center—that answered investigators’ questions and coordinated building tours.[54] The Washington Chapel was a visual landmark that drew people in and prepared them for the further light and knowledge the gospel had to offer. Just as those who drive the Capital Beltway for the first time are often shocked when they see the Washington D.C. Temple rising up out of the trees, in many ways, those who saw the Washington Chapel for the first time were drawn in by its uniqueness and beauty. Both have served as great missionary tools for the Church, and the Church’s “leadership perceived the Church’s image as improving in light of the new chapel.”[55]

In the Church, we sometimes use the name Elias as a title, referring to something or someone that serves as a “forerunner.”[56] In some ways, the Washington Chapel was a kind of proto-temple and an “Elias,” or forerunner, of the Washington D.C. Temple.[57] Even though it may not have been intended as such, the chapel seemed to prepare the people for the temple. DC-area resident Page Johnson noted that “the Washington Chapel prepared people of other faiths and backgrounds for the arrival of the temple. Washington area residents . . . first began to know and accept the ‘Mormons’ because of the Washington Chapel. That building prepared them for an even more special place—situated on a hill for all to see—that would represent the continuation and expansion of the Lord’s work.”[58]

As the chapel’s window of use drew to a close, and as members of the Church living in the area began to prepare for the open house and dedication of the Washington D.C. Temple, missionary work centered on both buildings became very important.[59] Indeed, in a way, the construction and dedication of the Washington D.C. Temple functioned as a transition—a passing of the mantle. What was once the historic centerpiece, symbolic of the Church’s presence in the area, would fade into the background as a new edifice, also reminiscent of the Salt Lake Temple,[60] took the chapel’s place as the official symbol of the restored gospel’s presence in the nation’s capital. As a former member of the Washington Ward pointed out, “The opening of the temple ushered in a new era of the Church in Washington. Before, the Washington Ward chapel was the center of activity and the symbol of the Church in the Washington area; now, the temple and the visitors center filled those roles.”[61]

The final meeting of Latter-day Saints in the Washington Chapel was held on 31 August 1975.[62] The building had been deteriorating over a number of years, needed extensive repairs, and the costs to restore and maintain it were prohibitive. [63] In addition, post-WWII, many members had moved out of the city, preferring the suburbs. The neighborhood in which the chapel stood, once considered an upper-class portion of DC, was now run-down and had an escalating crime rate.[64] The building had served its purpose but was now no longer ideal for the Church’s needs in that part of the world. Thus, on that last day of August in 1975, stake president Donald Ladd announced that the Washington Ward was being dissolved and that its members would in one week begin to attend the various other chapels in the areas in which the members resided.[65] President Ladd also announced that the Church would be selling the Washington Chapel.[66] Needless to say, many members were saddened by the announcement.[67] Less expected was the anger that some felt. “One group, the Historical Washington Chapel Preservation Committee, became fairly well organized in opposition to the Church’s selling the chapel. They prepared an extensive report against the action, which they sent to the First Presidency of the Church; and they received some publicity in the news media, making it necessary for the Church to respond.”[68] In the end, such efforts didn’t change things, and the Church moved forward with its preparations to sell the historic edifice.

It took nearly two years to sell the building, in part because of zoning, but also because of its need for extensive repairs, and because of its unique and elaborate architecture—which made it appealing to a limited clientele.[69] “On September 9, 1977, the Mormon Church sold the land rights to Columbia Road Recording Studios, Inc. who allegedly planned to use it for a radio/

Before the Church formally turned the building over to the Unification Church, a crane was utilized to remove the statue of the angel Moroni, and the Latter-day Saints also opened the building’s cornerstone to remove its contents.[72] “The Angel Moroni statue was . . . stored until 1984, when it was displayed in Salt Lake City in the new Museum of Church History and Art,” now known as the Church History Museum, “where it has been since that time.”[73] After taking possession of the property, the Unification Church made major changes to the interior and added their own identifying symbol to the spire where the angel Moroni once stood.[74]

Though many members of the Church are unfamiliar with the history and use of the old Washington Chapel, it is an important part of the history of the Church. For example, many members will be unaware that we once had a Sunday meetinghouse that displayed a statue of the angel Moroni atop its spire, that two future Presidents of the Church, an Apostle, and a future Apostle, served in the leadership of the congregations meeting in the Washington Chapel,[75] or that the Houston Texas Temple was architecturally modeled after the chapel.[76] There is so much history wrapped up in this important and yet forgotten edifice. Though no longer in the hands of the Church, it remains a monument to an important part of the Church’s history—particularly its history in the nation’s capital. As one source noted, “The Washington Chapel joins in with the monumental landscape of national churches while simultaneously distinguishing itself as a unique, distinct entity. . . . The building’s symbolic legacy of permanently establishing Mormonism in Washington would outlast the ownership of the Mormon Church.”[77]

Notes

[1] As one source noted, “The Church did not build chapels like this elsewhere.” Samuel R. Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter Day Saints (Unification Church), 2810 Sixteenth Street Northwest, Washington, District of Columbia (Washington, DC: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, n.d.), Library of Congress, HABS No. DC-539, 8. Another source referred to the chapel as “one of the most beautiful church edifices . . . ever seen.” P. V. Cardon, “A Vacant Lot at the Crossroads,” Improvement Era, September 1935, 546.

[2] See Lee H. Burke, History of the Washington D.C. LDS Ward: From Beginnings (1839) to Dissolution (1975) (Salt Lake City: Publishers Press, 1990), 1; Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 6; Edgar B. Brossard, “The Church in the Nation’s Capital,” Improvement Era, February 1939, 119.

[3] Unofficial meetings such as those held in DC were common during that era. See Brossard, “Church in the Nation’s Capital,” 120.

[4] See Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 14; F. Ross Peterson, “Washington, D.C.,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, and Richard O. Cowan (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 1314. One source noted that “the branch perhaps owes more to Senator Reed Smoot . . . than to any other one person. In a general way the branch is a memorial to the able and persistent Church work of Elder Smoot.” Brossard, “Church in the Nation’s Capital,” 120.

[5] In addition to various hotel rooms and living rooms, from the early 1900s until November 1933, Church meetings were held in a hall owned by the National Board of Farm Organizations and in the Washington Auditorium Building’s Assembly Hall.

[6] See Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 14, 20; Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 6; Milton Barlow and Margaret Cardon, comps., Washington Chapel (Washington, DC: self-pub., 1943), 4. DC resident Brent Smith noted that there are records “that refer to the branch organization in May 1920, thus showing a discrepancy to Edgar Brossard’s published reference to the branch having been organized in June of that year. . . . Reed Smoot’s diary (which states [that the branch was organized] May 30 [1920]), as well as [the] Eastern States Mission . . . records . . . noted that ‘the Washington Branch was partly organized (on the evening of May 30th). Elder Reed Smoot presented the name of J. Bryan Barton to act as branch president . . . until the branch becomes well established. . . . Elder Barton will look after the affairs of the branch until all of the organizations are completed, when he will [then] be relieved of part of the responsibility.’ . . . [It] would have taken a few weeks to issue callings and get the auxiliaries up and running, which is probably what Brossard was remembering.” Brent Smith, correspondence, 15 July 2020. On a related point, “When the chapel was dedicated in 1933, [the] Washington Branch was within the Capitol District of the Eastern States Mission.” The Washington D.C. Stake was organized on 30 June 1940 with Ezra Taft Benson as its first stake president. See Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 82, 83. The Washington Branch became a ward this same year. Sue A. Kohler and Jeffrey R. Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture (Washington, DC: The Commission of Fine Arts, 1988), 2:525; Reed Russell, “The Washington, D.C. Chapel,” http://

[7] See Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 40. One source pointed out that the location was ideal because it was “in the very heart of the embassy district.” See Gladys Stewart Bennion, “Impressions,” in “Washington Ward Calendar—10th Anniversary, Vol XI, No 2 (Feb. 1942),” in Edgar B. Brossard Collection, Utah State University Archives, COLL MSS 4, box 37, folder 10, p. 22.

[8] See Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 7; Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 41.

[9] The lots were originally owned by Westmoreland Davis, the governor of Virginia. See Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 7. At the time Robert Murray Stewart noticed them, the lots were empty. One source notes, “there were four small frame buildings located on the property facing Columbia Road in 1896; however, they seem to have been cleared shortly thereafter—at [the] latest by 1919—in order to widen Columbia Road.” See Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 3.

[10] See Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 41–43.

[11] Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 44. See also Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:521; Barlow and Cardon, Washington Chapel, 5. The Church was to be built “in the historical Meridian Hill neighborhood among embassies, churches, and well-to-do residences. . . . On either side of Sixteenth Street, wealthy homeowners gravitated to the corridor for its proximity to power, and an eclectic mix of congregations would follow including Baptists, Episcopalians, Jews and Buddhists.” The street became “the de facto setting for many foreign embassies and national churches.” See Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 1, 5. Elsewhere we read, “Other churches in the area were at first reluctant to have the Mormons in their neighborhood, as were also some of the permanent residents living near the chapel.” Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 69.

[12] See Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:521; Russell, “Washington, D.C. Chapel.”

[13] See Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 43. See also Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 7; Barlow and Cardon, Washington Chapel, 5.

[14] See Barlow and Cardon, Washington Chapel, 5. See also Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 43–44; Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:521–22.

[15] Henderson agreed to the sale of the property on 28 March, 1924 and signed the paperwork on 9 April of that same year. See Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 7. DC-area resident Page Johnson suggested: “Mrs. Henderson’s conditions for selling the lots to the Church give insight into the architectural planning of the chapel: It had to be a church that was appropriate for the location and which fit the type of architecture she would approve. . . . [Not] only did the Church want a beautiful structure, but so also did the seller, who conditioned the sale on” the promise of an aesthetically pleasing design. Page Johnson, correspondence, July 6, 2020.

[16] The third lot belonged to Lucy E. Moten. See Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 3, 7; Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:522. Her name is sometimes erroneously given as “Jucey E. Moten.”

[17] See Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 45; Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 2, 4. On 20 May 1924, Elder Reed Smoot sent a letter to Isaac Russell (of Chicago). In that letter, Elder Smoot noted, “We have purchased the best corner in Washington. It cost the Church $54,000. I expect the Church to put up a magnificent building here, one that will be . . . an honor to the Church. . . . I know nothing that will advertise the Mormon people better than a magnificent structure on the corner of Columbia Road and Sixteenth Street.” A transcript of this letter can be found in Russell, “Washington, D.C. Chapel.” It should be pointed out that “the Washington Chapel only served as the dedicated meetinghouse for all members of the Church in Washington from 1933–1938, when church leaders divided the congregation [in 1938] into the Arlington Branch (Virginia) and the Chevy Chase Branch (Maryland). Members [then] started building and attending other chapels in the area.” Page Johnson, correspondence, 6 July 2020, emphasis added.

[18] See editor’s comment in J. Reuben Clark Jr., “Beware of False Prophets,” Improvement Era, May 1949, 268. Page Johnson wrote, “A great mission of the Washington Chapel was to herald the presence of the Church in Washington. It did that very well for four decades.” Page Johnson, correspondence, 6 July 2020.

[19] “Washington Ward Calendar—10th Anniversary, Vol XI, No 2 (Feb. 1942),” in Edgar B. Brossard Collection, Utah State University Archives, COLL MSS 4, box 37, folder 10, p. 27. See also Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 7; Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 45.

[20] Inscribed on the cornerstone of the building is the name of the three architects who designed the chapel: Don Carlos Young Jr., Ramm Hansen, and Harry P. Poll—all from the firm of Young & Hansen. This same firm built other noteworthy buildings, including the Mesa Arizona Temple and the Salt Lake Federal Reserve Building, in addition to being responsible for the remodels of “all LDS temples in Utah between 1935 and 1953.” See Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 8. See also Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 45.

[21] See Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 2, 9, 10, 11; Brossard, “Church in the Nation’s Capital,” 122; Barlow and Cardon, Washington Chapel, 5; Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:525; Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 45, 50–51, 54; “Beautiful Washington D.C. Chapel of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormon),” Church History Library MS 3642, 2; Russell, “Washington, D.C. Chapel.” There were three dedicatory sessions and, according to Burke, approximately 1,200 people total attended. Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 54. Another source claims that “approximately 3,000 people total . . . attended the three dedicatory services.” See Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 10. See also “3,000 Attend Mormon Rite in Dedication,” Washington Post, 6 November 1933, classified section, 13; Russell, “Washington, D.C. Chapel.” In addition to dignitaries from the Church, the President of the United States was also invited to the chapel’s dedicatory services. “Although President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was invited and responded that he would try to make it if his schedule allowed him, he proved to be too busy to leave the White House that day.” Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 10.

[22] See “New Mormon Chapel in Washington,” in Boston Evening Transcript, 18 November 1933, magazine section, 4; Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:523. One can only conjecture why the Church chose to use Utah birdseye marble instead of using local East Coast materials. Nevertheless, this creates a parallel between the Salt Lake Temple and the Washington Chapel; both buildings using stone from the Utah mountains. Of birdseye marble, one website sponsored by the state of Utah explains, “Approximately 58 to 66 million years ago (Paleocene epoch), a large body of water known as Lake Flagstaff covered parts of northeastern and central Utah. This lake deposited a sequence of sediments that formed rocks known as the Flagstaff Formation. Although these rocks are technically a limestone, the building stone industry has termed this deposit a ‘marble.’ The rocks are rich in algal ball structures commonly known as ‘birdseyes.’ These birdseye features were formed by algae that grew around snail shells, twigs, or other debris. The algae used these objects as a nucleus, forming into unusual, elongated, concentric shapes.” https://

[23] “New Mormon Chapel in Washington,” in Boston Evening Transcript, 18 November 1933, magazine section, 4. See also Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:523.

[24] See Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 1; Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:525, 528.

[25] Harry Kimball, of Salt Lake City, was the artisan who created the stained-glass windows for the Washington Chapel. See Washington Ward Calendar, March 1939, CHL LR 9948 25, 2. DC resident Brent Smith pointed out, “[An] August 2011 earthquake in the DC area . . . damaged the chapel itself[,] including its sanctuary and its ‘South America/

[26] See Barlow and Cardon, Washington Chapel, 6; Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 62; Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 34; Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:525, 535; “Beautiful Washington D.C. Chapel,” 1. “The foyer also has stained glass windows. Its semicircular-headed window on the north elevation has stained glass depictions of books of scripture; the five books represent the Book of Mormon, the Old Testament, the New Testament, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price. The top book is larger than the other four and inscribed in a circle.” Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 34. One source noted that these windows depicting the standard works of the Church “so attracted the attention of passers-by that I have seen them stop, look, turn around and slowly mount the steps of the chapel to learn their meaning.” Gladys Stewart Bennion, “Impressions,” in “Washington Ward Calendar—10th Anniversary, Vol XI, No 2 (Feb. 1942),” p. 24. See also Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 48–49.

[27] “Washington Ward Calendar—10th Anniversary, Vol XI, No 2 (Feb. 1942),” in Edgar B. Brossard Collection, Utah State University Archives, COLL MSS 4, box 37, folder 10, p. 9. While it was absolutely not designed nor intended to be one of our temples, that it was commonly mistaken as one is suggested by the following comment by DC resident Brent Smith: “Since 2016, Church Public Affairs, other DC-area Church members/

[28] See, for example, “New Mormon Chapel in Washington,” in Boston Evening Transcript, 18 November 1933, magazine section, 4; Dave Clemens, “Inner Circle of LDS Church Debating Fate of Historic Structures,” in Ogden Standard-Examiner, 9 November 1975, 14A.

[29] See Barlow and Cardon, Washington Chapel, 6; ““Beautiful Washington D.C. Chapel,” 2; J. Michael Hunter, “I Saw Another Angel Fly,” Ensign, January 2000, 32.

[30] Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 1. See also 8, 23. In addition, see Barlow and Cardon, Washington Chapel, 6; Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:528. Another wrote, “its design was intended to symbolize the spirit of the temple at Salt Lake City.” Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:522. See also Russell, “Washington, D.C. Chapel.”

[31] See Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 10. See also Russell, “Washington, D.C. Chapel.”

[32] See Barlow and Cardon, Washington Chapel, 5; “Mormon Faith Heads to Join in Dedication,” Washington Post, 29 October 1933, p. M; “New Mormon Chapel in Washington,” in Boston Evening Transcript, 18 November 1933, magazine section, 4. John Gerritsen, the grandson of Torleif Knaphus, suggested that the reason a Moroni statue was placed atop the Washington Chapel was because of the importance of the location of this building in the nation’s capital. His understanding was that the Church wanted the chapel to be easily recognized. John Gerritsen, interview, 27 November 2019. Lee Burke similarly explained that “they wanted this chapel to be a showplace to the nation’s capital; one that functioned as a gathering place in a city of dignitaries and ambassadors of other countries.” In hindsight, the fact that it looked to many so much like a temple may have helped to facilitate this. Lee Burke, interviews, 3 November 2019 and 20 July 2020. Elder Reed Smoot’s 20 May 1924 letter, cited above, confirms this. See Russell, “Washington, D.C. Chapel.” Sometime after the statue was removed from the top of the Washington Chapel, LaVar Wallgren “made two castings of the Knaphus replica. One was placed on the Atlanta Georgia Temple; the other was placed on the Idaho Falls Idaho Temple.” See Hunter, “I Saw Another Angel Fly,” 32. This version of the statue is ten feet high and weighs 645 pounds. It is covered in 23-karat-gold leaf.

[33] See Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 8.

[34] Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:522–23. See also “New Mormon Chapel in Washington,” in Boston Evening Transcript, 18 November 1933, magazine section, 4. For additional parallels between the Washington Chapel and the Salt Lake Temple, see Kohler and Carson 2:530; “Beautiful Washington D.C. Chapel,” 2; Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 25; “A Union Service with Mormons,” the Christian Leader (a national periodical of the Unitarian Church in America), cited in Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star, 30 May 1935, 339–40.

[35] Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 28.

[36] See Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 67; and Barlow and Cardon, Washington Chapel, 6. See also http://

[37] See Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:525–26. See also Russell, “Washington, D.C. Chapel.”

[38] Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 131–32.

[39] Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 4. See also “Beautiful Washington D.C. Chapel,” 1.

[40] While we do not know the extent of his involvement, President Heber J. Grant personally signed one of the architectural drawings of the building, and above his name he wrote “Approved.” See “Washington Chapel Rendering” dated 1925, CHL MS 27892.

[41] See Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:525. See also CHL LR 9948 25, “The Chapel Beautiful,” 26; Franklin S. Harris Jr., “Washington Chapel Dedicatory Services,” Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star 95, no. 49 (14 December 1933): 801–2; “3,000 Attend Mormon Rite in Dedication,” 13; “New Mormon Chapel in Washington,” in Boston Evening Transcript, 18 November 1933, magazine section, 4; Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 51. In his remarks (at the dedication), Elder Stephen L. Richards of the First Presidency described the chapel as “a beautiful prediction of the future.” Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 57. One can only conjecture as to what exactly President Richards meant or saw. Did he foresee the day when the temple would be built there? Or were his words simply meant as a prediction that the Church would grow significantly in the DC area in the coming years?

[42] For example, President Grant prayed, “Father, we thank Thee for this beautiful chapel and we now dedicate it to Thee for Thy Holy purposes.” “3,000 Attend Mormon Rite in Dedication,” 13. Similarly, in the Birmingham, Alabama Temple dedication, President Gordon B. Hinckley prayed, “We are met to present unto thee this sacred house, a temple of the Lord dedicated for purposes according to Thy will and pattern.” “Dedicatory Prayer,” Birmingham Alabama Temple, 3 September 2000. https://

[43] Richard O. Cowan, Temples to Dot the Earth (Springville: Cedar Fort, 1997), 112.

[44] Barlow and Cardon, Washington Chapel, 7; Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 55.

[45] See Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 54; “3,000 Attend Mormon Rite in Dedication,” 13. They had a special dedication for the cornerstone of the chapel; something unheard of for a chapel, but similar to a Temple. Elder Reed Smoot offered the prayer of dedication, stating the following, among other things: “Bless, O Lord, this effort. Help us to complete with all possible speed the erection of this building that it may be dedicated to Thy holy name. . . . May the stone laid here this day be a corner stone to a place of worship where truth and light may be always uppermost in the mind of those who come within its sacred portals.” Reed Smoot Cornerstone Dedicatory Prayer, CHL LR 9948 20, 1–2, emphasis added.

[46] Washington Evening Star, cited in Improvement Era, April 1957, 250.

[47] Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 14–15.

[48] Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 37. See also “Washington Ward Calendar—10th Anniversary, Vol XI, No 2 (Feb. 1942),” in Edgar B. Brossard Collection, Utah State University Archives, COLL MSS 4, box 37, folder 10, pp. 4–5, 7. During that era, the Washington and Potomac Stakes—which shared a border—were among the five highest baptizing stakes in the Church. See “Proposal for a Washington D.C. Temple,” in Edgar B. Brossard Collection, Utah State University Archives, COLL MSS 4, box 37, folder 15, p. 13.

[49] Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 70. Having a chapel in DC was a unique opportunity for making national and international contacts, as the building would be built in the heart of the embassy district. In fact, the chapel was listed in all major hotel and guidebooks of the era. Even cab drivers were familiar with the iconic edifice, and approximately ten thousand guests per year visited the building and toured its facilities. Such was not the case for most DC churches of the era, but the Washington Chapel was architecturally unique. Edgar Brossard explained, “A Church that has no National Chapel in Washington cannot be adequately represented in the religious life of the Capital. The Latter Day Saints have felt keenly the need of a spiritual center. . . . A superb building adds to the dignity of religious services, and a monumental church in Washington adds to the dignity and prestige of a religious organization.” Church leaders in the area wanted to build a “National Chapel,” which would be a showplace for the Church. It has been said that the unique Utah birdseye marble made the Church building “reminiscent of the Salt Lake Temple.” The distinctive exterior stone and gold Moroni statue would add to the uniqueness of the building and facilitated drawing attention to its unusual features. See Edgar B. Brossard Collection, Utah State University Archives, COLL MSS 4, box 37, folder 10, pp. 17, 22, 23, 28.

[50] See Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 63–64. Writing about the chapel’s remarkable organ, George D. Pyper—once a member of and “manager” of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir—wrote, “next to the great Salt Lake Tabernacle organ there was installed in the Washington chapel the finest instrument in the Church.” See George D. Pyper, “Church Music—LDS Church Music at the Nation’s Capital,” Improvement Era, December 1933, 863.

[51] Brossard, “Church in the Nation’s Capital,” 122. Another source noted, there were “public organ recitals six days a week (every day except for Sunday) for the first year, recording more than 18,000 visitors.” Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 15. See also Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:525. Edward P. Kimball was the organist for the Tabernacle Choir for nearly three decades prior to becoming the organist for the Washington Chapel. In response to a call from the First Presidency of the Church, he remained the organist at the chapel until his death (in 1937). Handwritten note regarding Kimball, in Edgar B. Brossard Collection, Utah State University Archives, COLL MSS 4, box 37, folder 7; “Washington Ward Calendar—10th Anniversary, Vol XI, No 2 (Feb. 1942),” in Edgar B. Brossard Collection, Utah State University Archives, COLL MSS 4, box 37, folder 10, p. 4.

[52] Brossard, “Church in the Nation’s Capital,” 123.

[53] Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 74. See also “Washington Ward Calendar—10th Anniversary, Vol XI, No 2 (Feb. 1942),” in Edgar B. Brossard Collection, Utah State University Archives, COLL MSS 4, box 37, folder 10, p. 7.

[54] See handwritten note about Edward Kimball, in Edgar B. Brossard Collection, Utah State University Archives, COLL MSS 4, box 37, folder 7. See also Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 57–58, 59, 62, 71. The Salt Lake Temple Square Visitors’ Center was originally called “The Bureau of Information,” and functioned much like the one operated at the Washington Chapel. See “Washington Ward Calendar—10th Anniversary, Vol XI, No 2 (Feb. 1942),” in Edgar B. Brossard Collection, Utah State University Archives, COLL MSS 4, box 37, folder 10, p. 30; Edward H. Anderson, “The Bureau of Information,” Improvement Era, December 1921, 130–39. One source noted, “At the close of the services, announcement was made that strangers who cared to remain would be shown through the building by Brother Kimball.” Cardon, “Vacant Lot,” 584. Kimball was originally the director of the bureau. See “Washington Ward Calendar—10th Anniversary, Vol XI, No 2 (Feb. 1942),” in Edgar B. Brossard Collection, Utah State University Archives, COLL MSS 4, box 37, folder 10, p. 4.

[55] Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 13. “On March 1, 1976, the New York Times described how the chapel’s completion in 1933 was ‘seen as a testament to the end of Washington’s hostility toward the Mormons.’” Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 18. Not many members lived in the DC area (in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries), in part because of the Church’s emphasis on gathering to Utah and, quite possibly, because perceptions of the Church were not great in those early years, particularly in Washington. President Heber J. Grant (1856–1945), eighth President of the Church, pointed out, “for years and years not a single person from Utah was ever able to secure employment in Washington, and . . . the delegates from Utah were expelled” from the United States Senate. Heber J. Grant, in Conference Report, April 1930, 186. See also Heber J. Grant, Gospel Standards (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1998), 90. The Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History similarly notes, “During the nineteenth century, numerous Latter-day Saint leaders visited the [U.S.] capital to seek federal support for the move west and for statehood, although the Church and the federal government were at odds over a variety of issues from 1857 until 1907.” Peterson, “Washington, D.C.,” 1314. See also Brossard, “Church in the Nation’s Capital,” 119. In more recent years, “the LDS Church has maintained a positive and respected position in Washington, D.C. The relationship with the federal government has evolved from one of antagonism and prejudice to one of participation and influence.” Peterson, “Washington, D.C.,” 1315. Thus, even though the Church would begin to grow rapidly in various parts of the world, starting with its official organization in 1830, it would be many decades before it gained any footing in the DC area. However, things would change. The Washington Ward would eventually include notables, such as a member of the United States Tariff Commission, the head of the Publication Division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the director of agricultural extension and industries for all Native Americans in the United States, the head of the Sugar Manufacturers’ Association of America, two future presidents of the Church, and several individuals holding various elected offices. Cardon, “Vacant Lot,” 583–84. The makeup of the congregation seems significant owing to all that the Church had gone through in that city over the years—particularly in light of a twentieth-century tradition of a supposed prophecy made by Joseph Smith after visits with President Martin Van Buren. After the president rebuffed the prophet, Joseph is said to have prophesied not only of the demise of Van Buren’s political career but also of a time when the Saints would be influential in DC. One source gives the prediction as follows: “The Mormons would return to Washington and occupy responsible positions in the affairs of the state and become a respected people.” Wendell B. Anderson, “Mormons in Washington,” Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star, 3 September 1942, 563. Elsewhere, this same prophetic declaration is given as: “Some day [sic] the Mormon people will be held in renown in the nation’s capital.” See “The Church Moves On,” Improvement Era, July 1938, 415.

[56] See “Elias,” in LDS Bible Dictionary (2013), 634; Robert L. Millet, “Elias,” in LDS Beliefs: A Doctrinal Reference, ed. Robert L. Millet, Camille Fronk Olson, Andrew C. Skinner, and Brent L. Top (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 177.

[57] It should be understood that we are not claiming that the Washington Chapel was intended as a “placeholder” for the future temple, nor are we claiming that the Church necessarily intended it as a “forerunner” to the future temple—only that it ultimately functioned as such.

[58] Page Johnson, correspondence, 6 July 2020.

[59] Burke Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 107.

[60] One source noted, “Similar to the Chapel before it in 1933, the [Washington D.C.] Temple sought to pay homage to the Salt Lake Temple, but it did so in a more formal gesture rather than a stylistic one. The six-spire design recalls that of the flagship temple in the Great Basin, but the architectural style is radically modern and dramatically vertical. The one feature shared by all three buildings . . . is having their highest point capped by as statue of the angel Moroni.” Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 17. Elsewhere we read, “The temple towering over the trees near the Washington Beltway, . . . gives the appearance of the Salt Lake Temple with similar shape and six towers. It is a breathtakingly lovely building—sometimes looking almost unreal, so white and tall above the trees.” Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 132.

[61] Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 134. The groundbreaking for the Washington D.C. Temple was held on 7 December 1968. See Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 131.

[62] See Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:525; Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 2, 18.

[63] See “Mormons’ historic chapel for sale as parish dissolves in Washington,” Battle Creek Enquirer (Battle Creek, MI), 3 April 1976, 7, where it suggests that repairs needed on the building would have cost the Church $450,000—and that figure excluded the cost of needed masonry work. See also “Mormons Selling Historic Chapel,” in New York Times, 1 March 1976, 42. The building was also lacking adequate parking. “Car ownership” when the building was built “was uncommon, and the later essential parking lot was not even considered in constructing the chapel. Street cars were the accepted mode of travel” when the building was first built. Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 69.

[64] See Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 136–39.

[65] According to Burke, the Washington Ward was dissolved before the building was sold, largely because of dissension in the ward regarding the selling of the building. Thus, there was a directive that the Washington Ward members begin to attend family wards in the suburbs of DC. At the time, the ward was made up of singles, sort of a mishmash attending from all over the area. Burke, similarly, lived in Virginia but attended the Washington Ward. Lee Burke, interview, 3 November 2019. Page Johnson pointed out, “In the last years the building was owned by the Church, a Spanish branch also met there.” Page Johnson, correspondence, 6 July 2020.

[66] See Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 135.

[67] See Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 135.

[68] Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 140; see also Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 18; Russell, “Washington, D.C. Chapel.” The Ogden Standard-Examiner reported, “Some critics” of the Church’s “preservation practices say the church lacks a guiding policy on historical buildings and has based the future of its edifices too much on financial expediency and on architecturally uninformed decisions by local leaders. The Church responds that its business is saving souls, not buildings, and that it can’t preserve all the structures others might think merit saving.” Two architects, Allen Roberts and Paul Anderson, conducted a “study” of the Church’s “historical buildings” and counseled the Church that the “Washington, D.C., chapel” should be considered “untouchable.” The Standard-Examiner added, “A group of local [DC] Mormons joined in to oppose the sale.” See Dave Clemens, “Inner Circle of LDS Church Debating Fate of Historic Structures,” in Ogden Standard-Examiner, Sunday, 9 November 1975, 14A.

[69] Mitchell NewDelman, president of Columbia Road Recording Studios, “said he contracted in April 1976 to purchase the chapel from the Mormon Church, but because of zoning and other difficulties, including a restrictive covenant in the deed, he was unable to reach a final settlement.” “The Mormon Media Image,” Sunstone, November–December 1977, 24. See also Laura A. Kiernan, “Unification Church Buys Former Mormon Chapel,” Washington Post, 16 September 1977. https://

[70] Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:525; Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 3–4; see also 1 and 19; Russell, “Washington D.C. Chapel.” Burke claims it was sold the very same day. See Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 141.

[71] Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 141; Russell, “Washington, D.C. Chapel.”

[72] See Kohler and Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture, 2:525–26. See also Russell, “Washington, D.C. Chapel.” Ariel Thomson, then a member of the high council, was given the assignment to clear out the building and remove the contents of the cornerstone. Thompson tried using a number of different chisels and four types of hammers in order to get the cornerstone open. He worked on opening it for three hours, with absolutely no progress (because the mortar was so hard). He finally took his biggest hammer and smashed the sides of the cornerstone. That enabled him to access the metal box inside. Within that box was a triple combination and a 1933 New York Times and Washington Post. According to Thomson, Don Ladd, who was at that time president of the Washington Stake, kept the triple combination that had been retrieved from the cornerstone. Ariel Thomson, interviews, 14 March 2019 and 2 November 2019.

[73] Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 140.

[74] See Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 19–23.

[75] President Ezra Taft Benson was the first president of the Washington Stake, serving in that capacity from 30 June 1940 until 5 March 1945. President Russell M. Nelson served as the second counselor in the DC Ward bishopric from 29 December 1951 until 15 March 1953. Apostles Reed Smoot and Richard G. Scott also served in the leadership of the Church in DC, the latter of the two serving as a counselor in the stake presidency (in the early 1970s), and the former being the one who first presided at gatherings of the Church in the area (prior to the official organization of a Church unit in DC). In addition, Religious Education professor Reed A. Benson—son of President Ezra Taft Benson—served as the second counselor in the bishopric from 13 February 1955 until January 1956. See Burke, Washington D.C. LDS Ward, 147, 149, 156.

[76] See Russell, “Washington, D.C. Chapel,” comments 51, 52, 54.

[77] See Palfreyman, Washington Chapel, HABS No. DC-539, 14, 10. Another source similarly stated that the Washington Chapel has been called “so rare a jewel, even among the magnificent churches of Washington.” Brossard, “Church in the Nation’s Capital,” 122.