Preaching Jesus, and Him Crucified

Eric D. Huntsman

Eric D. Huntsman was a professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University and the coordinator of the Ancient Near Eastern Studies Program when this was published.

On Good Friday we gather to commemorate all that Jesus Christ did for us in the final week of his life, and we prepare to celebrate his Resurrection on Easter morning. From third to eleventh grade, I grew up in the greater Pittsburgh area, where most of my friends were Roman Catholics or mainline Protestants. This was an area where we always had fish on Fridays in the school cafeteria and where many of my friends were excused from school on Good Friday. Growing up as a member of the LDS diaspora, I used to wonder, “What is so good about Good Friday?” I knew that it was the day when we commemorated that Jesus had died for us on the cross, but celebrating it as a holiday was not part of either my church or family traditions.

Francisco de Zurbarán, Crucifixion.

Francisco de Zurbarán, Crucifixion.

Now it is, and I would ask the question “Why not Good Friday?” Only over time have I come to understand better the meaning of this day. Only as an adult did I come to learn that “good” here might have been an archaic way of referencing God, as when we say “good-bye,” which originally meant “God be with ye” or “Go with God.” That aside, it is good because it was “holy” Friday, the day when, as Paul says in Romans 5:8‒12, we were reconciled to God by the death of his Son. The Crucifixion, which stands starkly and painfully as the central feature of this day, figures as one of the central features of the teaching of Paul, who wrote, “For I determined not to know any thing among you, save Jesus Christ, and him crucified” (1 Corinthians 2:2) and “God forbid that I should glory, save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, by whom the world is crucified unto me, and I unto the world” (Galatians 6:14).

A number of factors have probably contributed to why Latter-day Saints do not formally celebrate Good Friday as a holiday per se. Generally, as a faith community we tend to avoid emphasizing or focusing on all the suffering connected with the last day of Jesus’ mortal life. Many of the earliest Latter-day Saints were descended from New England Puritans, who largely avoided marking holy days, some of them even avoiding celebrating Christmas. Perhaps most significantly, culturally our faith community has not featured the cross in its iconography. Nevertheless, Book of Mormon features prophecies about Jesus’s rejection, abuse, false judgment, and Crucifixion such as 1 Nephi 19:9, 2 Nephi 6:9, and Mosiah 3:9.

In regard to the cross, Gaye Strathearn, associate professor of ancient scripture, and Robert L. Millet, professor emeritus of ancient scripture and former dean of Religious Education, have done important work examining many of the historical, theological, and cultural issues involved in our understanding of the use of the means of our Lord’s death as a symbol for his atoning work. After reviewing historical aspects of crucifixion as a form of execution and how New Testament authors employ its imagery in her 2013 Religious Educator article “The Crucifixion: Reclamation of the Cross,” Strathearn reflects on reasons why the cross should be meaningful to Latter-day Saints. These include the fact that the events on the cross were integral parts of the Atonement, that Christ’s being lifted up upon it was a symbol of God’s love for us, that the invitation to “take up our cross” was a symbol of discipleship, and that the signs of the Crucifixion were so significant that he retained them in his resurrected body.[1]

Harry Anderson, The Second Coming.

Harry Anderson, The Second Coming.

In his essay “What Happened to the Cross?” in a 2007 Deseret Book volume of the same name, Millet, noting that he is not aware of any doctrinal prohibition against the display of crosses, suggests that perhaps the first Latter-day Saints did not use it largely because of their Puritan, anticonographic roots (105).[2] In addition, our cultural avoidance of focusing on Jesus’s suffering in the hands of the Jewish and Roman authorities and his death upon the cross may also be a result of what Millet has called the tendency to “teach to our distinctives.”[3] Because we have a deeper understanding of the role of Gethsemane in Jesus’s saving work, we often focus on that critical part of the Atonement. To this I would add the human penchant to sometimes react against the teachings of others: because we feel that some of our friends of other Christian traditions overemphasize the cross, perhaps we sometimes overcompensate by not considering it enough. Nevertheless, the cross is central to Jesus’s own definition of what his gospel is. Speaking to the gathered Nephites, the Risen Lord proclaimed:

And my Father sent me that I might be lifted up upon the cross; and after that I had been lifted up upon the cross, that I might draw all men unto me, that as I have been lifted up by men even so should men be lifted up by the Father, to stand before me, to be judged of their works, whether they be good or whether they be evil—

And for this cause have I been lifted up; therefore, according to the power of the Father I will draw all men unto me, that they may be judged according to their works. (3 Nephi 27:14−15; emphasis added)

Jesus’s Atoning Journey

The events between Gethsemane up to and including Golgotha are likewise important parts of our Atonement theology. Book of Mormon prophecies such as 1 Nephi 19:9, 2 Nephi 6:9, and Mosiah 3:9 emphasize how Jesus experienced betrayal, abandonment, rejection, abuse, and false judgment. No wife betrayed by a husband, no child abused by a parent, no friend rejected by another will fail to resonate with Jesus’s being betrayed by the kiss of a friend, abandoned by his disciples, and denied, if only briefly, by Peter. No one who has ever been falsely judged can fail to relate to how Jesus, innocent and pure, was falsely accused and condemned. Through these experiences, Jesus “descended below all things” (D&C 88:6; see also D&C 122:8), and they may have been ways that Jesus shared such burdens.[4]

Reclaiming Good Friday and the cross thus begins, perhaps, by seeing Jesus’s salvific work as an atoning journey rather than as a discrete event in the Garden of Gethsemane. Employing the Old Testament sacrificial model, this journey began when our burdens were placed upon Jesus in Gethsemane, just as an Israelite worshipper claimed his sacrificial victim by laying hands on it, symbolically transferring both ownership and guilt. It continued as Jesus was led away captive from the garden, carrying that burden, even as the scapegoat carried Israel’s guilt. It culminated when he died upon the cross, just as a sin offering was slain for atonement or as the paschal lamb was slaughtered so that the sinful might live. And then, just as the smoke of the sacrifice rose to God, so did Jesus rise with newness of life through the Resurrection to ascend to his Father.[5]

This has led Elder Holland to “speak of the loneliest journey ever made and the unending blessings it brought to all in the human family. I speak of the Savior’s solitary task of shouldering alone the burden of our salvation, . . . these scenes of Christ’s lonely sacrifice, laced with moments of denial and abandonment and, at least once, outright betrayal.”[6] Understanding that this journey includes betrayal, abandonment, denial, abuse, and false judgment provides poignant context for the well-known prophecy, “But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities: the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed” (Isaiah 53:5; cf. Mosiah 14:5).

Caravaggio, The Flagellation of Christ.

Caravaggio, The Flagellation of Christ.

The “lifting up” motif of the Gospel according to John suggests that the importance of the cross is not its shape—which could have been a t-shaped tau, an x-shaped chi, something akin to the usually depicted Latin cross, or mere scaffolding or a convenient tree—not its later use in iconography. To Nicodemus, Jesus declared, “And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up: that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have eternal life” (John 3:14−15). The type of the brazen serpent raised by Moses in Numbers 21:9 to provide healing for all who would look suggests that Jesus’s being raised upon the cross was a symbol of how his atoning suffering and death are there for all to see and how he will heal all those who will look to him. To the Pharisees, he said, “When ye have lifted up the Son of man, then shall ye know that I am he” (John 8:28), and to the people before his Passion he prophesied, “And I, if I be lifted up from the earth, will draw all men unto me. This he said, signifying what death he should die” (John 12:32), words very close to what he would later use in 3 Nephi 27.[7]

Dying Daily in Christ

Another less-explored way of reclaiming the cross is to explore and embrace some of Paul’s imagery and teaching, particularly “I protest by your rejoicing which I have in Christ Jesus our Lord, I die daily” (1 Corinthians 15:31; emphasis added). This concept of “dying daily” can be connected to the Pauline participation salvation model. Like many Latter-day leaders and teachers, the Apostle Paul strove to help explain the Atonement of Jesus Christ through different models or comparisons. Today we have President Packer’s debtor model, President Gordon B. Hinckley’s “He Took a Lickin’ for Me” model, or Stephen Robinson’s parable of the bicycle.[8] In his writings and those attributed to him, Paul employed a number of models including the judicial, rescue, expiation, and redemption models. Perhaps the most common, and important, is the reconciliation model, the Greek word katallagē for reconciliation also being the word translated as “atonement.”[9] But of particular importance for the events of Good Friday is the participation model, which suggests that in some deep way we participate with Christ in the different aspects of his saving work, benefiting from their results and, sometimes, a degree of the experiences themselves.[10] It is in this way I suggest that we can understand Paul’s references to dying with Christ.

First, Dying to Sin

In Romans 7:1‒6, Paul uses an analogy from marriage to explain how Christians, especially Jewish Christians, were freed from the demands of the old law of Moses when they become new creatures in Christ. Just as a woman is free to remarry after her husband dies, so Christians are now party to a new covenant, the law of Christ. This has a possible illustration in a Jewish burial custom. Throughout an observant Jewish man’s adult life, he wears a tallit, or fringed garment, as either a prayer shawl or tallit gadol for morning prayers and high holidays or as a special undergarment, the tallit qatan. Both have fringes that are tied in 613 knots, which represent the 613 mitzvot or commandments of the law. When a man dies, he may be wrapped in his tallit, the tassels of which are cut off to indicate that he is no longer bound by the law.[11]

Tallit

Tallit

Because both Romans and 2 Nephi 2 explain that one of the purposes of law is to define sin, the participation model explains Paul’s powerful baptismal imagery: “Know ye not, that so many of us as were baptized into Jesus Christ were baptized into his death? Therefore we are buried with him by baptism into death: that like as Christ was raised up from the dead by the glory of the Father, even so we also should walk in newness of life” (Romans 6:3‒4). The old man or woman of sin thus dies, emerging from the waters of baptism as a new man or woman of Christ.[12] But as virtually all of us have experienced, the mighty change of heart that we have at conversion does not always yield a permanent state of no longer having a disposition to do evil, as King Benjamin describes it (see Mosiah 5:2). Instead, most of us must frequently, even daily, take personal inventory, asking ourselves with Alma, “If ye have experienced a change of heart, and if ye have felt to sing the song of redeeming love, I would ask, can ye feel so now?” (Alma 5:26). Having had that mighty change of heart and having been born of God—which are experiences so graphically illustrated by baptism—we must retain and often regain it, dying to sin daily and beginning to live in Christ anew. Is this partly what Paul meant when he said that he “died daily”?

Garden Tomb

Garden Tomb

Dying to Sorrow

On Good Friday, Jesus was the quintessential Man of Sorrows: “He is despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief. . . . Surely he hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows: yet we did esteem him stricken, smitten of God, and afflicted” (Isaiah 53:3‒4). I came to better understand this right before Easter in 2007. Our son, Samuel, was just being diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder, and our hearts were broken. Already suffering from a developmental delay, our little boy stopped smiling, rarely talked, and would not look at us in the eye or let us hold him. On the Thursday before Easter while in the Provo Utah Temple, I poured my heart out to the Lord in the celestial room. I felt words and phrases come into my mind in response to each of my silent pleas. When I expressed my sadness that my son might not have all the traditional opportunities and life experiences that LDS parents often expect for their children—such as serving a conventional, full-time mission and marrying in the temple—the answer that came was direct. Many young men and women in the Church do not have those opportunities, the Spirit seemed to say, but often it is because of choices they make. If Samuel did not, it was because he was not able, and he would not be deprived of any blessing in the eternities. Understanding but still distraught, I cried out in my heart, “But Lord, he is my only son!” As chance had it, that day was Maundy Thursday, the Thursday before Easter that commemorates the Last Supper and Jesus’s suffering in Gethsemane. The next day was Good Friday, when the Son of God suffered and died for all of us. The clear response to my cry was firm and struck me to the core: “What about my Only Son?”

Eric and Samuel Huntsman.

Eric and Samuel Huntsman.

In the years since, we have seen miracles small and great in Samuel’s life. He is mainstreamed in public school, and last year I ordained him a deacon. He smiles, talks, and laughs. There are still disappointments, challenges, and heartaches, but I am learning to allow sorrow to draw me closer to my Savior. How often do we pray, asking the Lord to make us more like Jesus? Then, when the trials and heartaches come that will refine and shape us, we more often than not plea for him to take them away. There is something about suffering with Jesus that makes us more like him. And if this is true, then “death,” both actual and metaphorical, can signal the end of suffering. Alma taught, “And then shall it come to pass, that the spirits of those who are righteous are received into a state of happiness, which is called paradise, a state of rest, a state of peace, where they shall rest from all their troubles and from all care, and sorrow” (Alma 40:12; emphasis added). Jesus bore our griefs and carried them to the cross. When our sorrows bring us closer to Jesus, the miracle of the Atonement is that he lifts them, carries them, and dies for them. Trusting Christ, availing ourselves of his comforting grace, means letting the man or woman of sorrow die each day.

Dying to Sickness and Infirmity

One of the great Christological contributions of the Book of Mormon is found in Alma’s sermon in Gideon. Apparently drawing upon Isaiah 53:4, as Matthew later would, Alma prophesied, “And he shall go forth, suffering pains and afflictions and temptations of every kind; and this that the word might be fulfilled which saith he will take upon him the pains and the sicknesses of his people. . . . He will take upon him their infirmities, that his bowels may be filled with mercy, according to the flesh, that he may know according to the flesh how to succor his people according to their infirmities” (Alma 7:11‒12; Matthew 8:16‒17). In addition to taking upon himself our sins and our sorrows, here Alma teaches us that Jesus also bears our pains, sicknesses, and weaknesses. From this arises our understanding of the beautiful healing power of Christ’s grace.

Eric and Marilyn Huntsman.

Eric and Marilyn Huntsman.

In our mortal lives we often describe death as bringing welcome relief to pain and sickness. Indeed, how often do we speak of someone who dies after a long illness by observing, “Well, at least he is no longer suffering.” This was the case with my own dear mother. A three-time cancer survivor, she endured to the end, living life as fully as she could, serving her family and her church with faith and an inspiring, positive attitude. Finally, however, Mother’s body, ravaged by cancer treatments, at last faltered in the face of renal and then heart failure. In her final months, this once vibrant, joyful woman literally withered before our eyes. As heart-wrenching as her death was to me, when she passed peacefully in my home with me standing by her side and my daughter holding my hand, I felt to thank God that her struggle was over and that she was no longer in pain. Seeing the peaceful expression on her face, I knew that her spirit was now free.

Following Paul, I would suggest that Jesus did not just vicariously suffer for our infirmities, but he took them up and carried them to the cross, where his death brought them to an end. Even as Jesus heals our hearts of sorrow, so he can heal our bodies, miraculously in this life and ultimately through the Resurrection. The mortal man and woman of sickness and death can be strengthened and sustained in this life and ultimately exchange this corruption for incorruption.

The Lamb of God

To the Pauline concept of our sin, sorrows, and infirmities being swallowed up in the death of Christ, I would add one other powerful Johannine image. This is of Jesus as the Lamb of God who “taketh away the sin of the world” (John 1:29). Significantly, “sin” here is in the singular, referring apparently not only to our individual sins and transgressions but more broadly to our sinful, fallen, and mortal state. Indeed, I would suggest that in John, Jesus’s saving death is portrayed primarily as the source of spiritual, eternal life. Whereas the synoptics largely employ the imagery of Jesus’s death as a sacrificial offering for sin, the blood of the first Passover lambs was intended to ward off death and allow new life. Even as that blood was spread on the wooden door frames of the huts of the Hebrews in Egypt, now the blood of the Lamb of God stained the wood of the cross. Not only did Jesus’s death on the cross ward off spiritual death, the water that flowed with the blood from his side can symbolize a fountain of life-giving water springing up unto everlasting life.

Francisco de Zurbarán, “Agnus Dei.”

Francisco de Zurbarán, “Agnus Dei.”

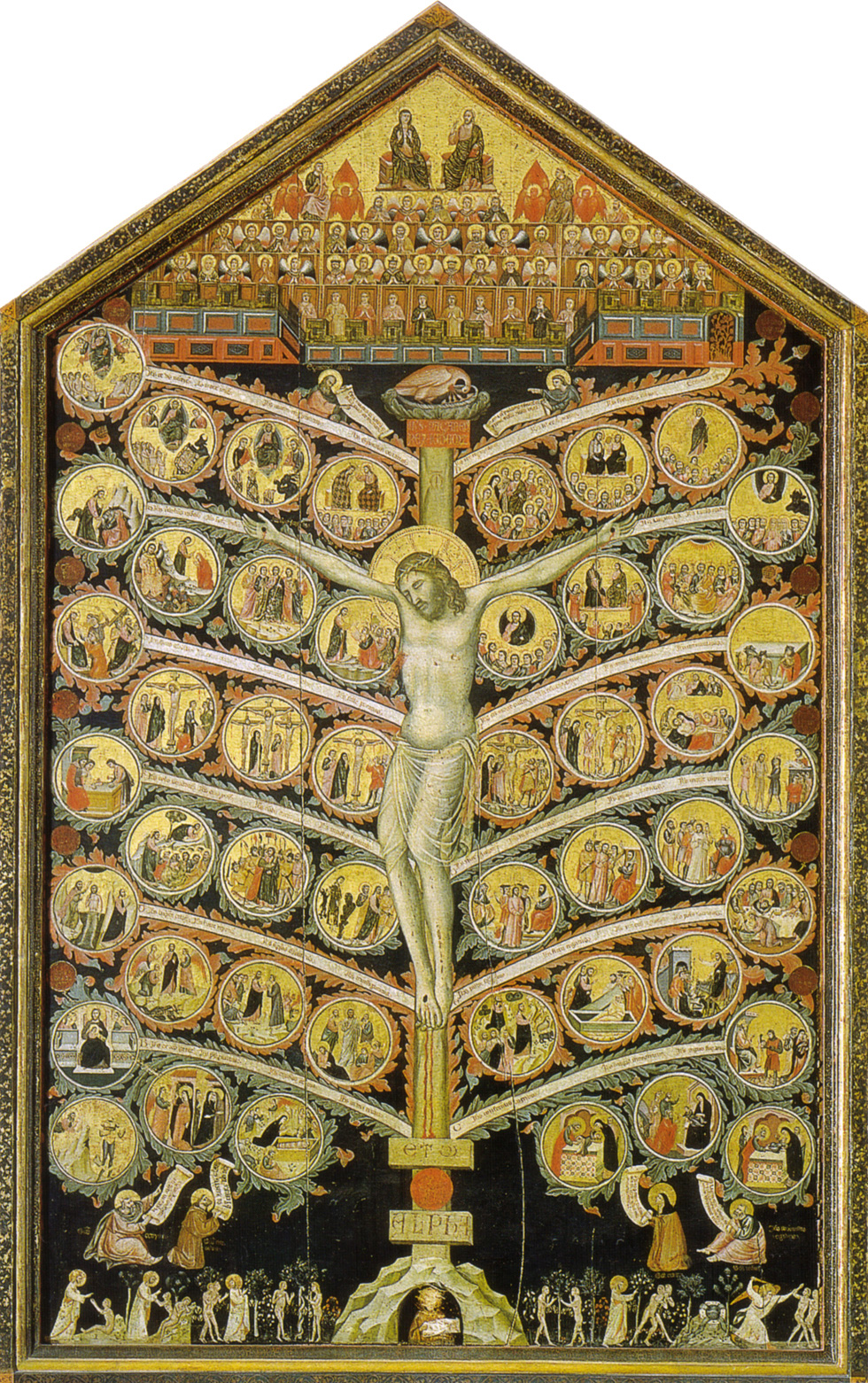

Indeed, part of reclaiming the cross is seeing it not just as a symbol of death but as a source of new life. This is illustrated in the legend—perhaps better the allegory—of Adam’s tomb. In the Middle Ages arose the story that Adam had been buried under Golgotha. Thus, in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre under the Greek and Latin altars of Calvary lies the Chapel of Adam, with a pane of glass revealing the rock of Golgotha. Thus, when Jesus later died upon the cross, the blood and water from his side ran down its post and flowed into Adam’s grave, making him the first beneficiary of Christ’s saving blood and life-giving stream. While this is but a legend, it speaks to the truth that “for as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive” (1 Corinthians 15:22). This also gave rise to the image of the Verdant Cross, a cross that sprouted leaves and fruit. In other words, the dead tree of cursing had become a new tree of life.

Commonly, we explain our wariness of the cross by emphasizing that we worship a living Christ, not a dying Jesus. It is true that our Catholic friends utilize a crucifix—that is, a depiction of Jesus on the cross—largely for liturgical reasons, because the celebration of each mass is a new sacrifice. But I remember being surprised once when a former Presbyterian friend corrected me when I told her that we preferred to worship a living rather than a dead Christ; she responded that she did too. The cross reminded Protestants that Jesus died for their sins, but it was empty because he was risen and was no longer there on it. I was chastened by her response, realizing that just as we do not appreciate others mischaracterizing our beliefs, neither should we presume to understand or misrepresent the beliefs and practices of others.

Matt Reier, Nails. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Matt Reier, Nails. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

While President Hinckley taught that the lives of our people—lives transformed by Christ—are the most meaningful expressions of our faith and serve as the symbol of our worship, he also said, “No member of this Church must ever forget the terrible price paid by our Redeemer, who gave his life that all men might live . . . This was the cross on which he hung and died on Golgotha’s lonely summit. We cannot forget that. We must never forget it, for here our Savior, our Redeemer, the Son of God, gave himself a vicarious sacrifice for each of us.”[13]

And so while I, with you, look forward with eager anticipation to the joy of Easter morning, and while I live each day with a firm assurance that he lives, on Good Friday I pause to think of his suffering and death. Tonight in Salt Lake some 360 of my closest friends will be closing their performance of Handel’s Messiah with the words of the heavenly hosts, singing, “Worthy is the Lamb that was slain, and hath redeemed us to God by his blood, to receive power, and riches, and wisdom, and strength, and honour, and glory, and blessing. . . . Blessing and honour, glory and power, be unto him that sitteth upon the throne, and unto the Lamb, for ever and ever” (Revelation 5:12–13).

Pacino di Bonaguida, Tree of Life.

Pacino di Bonaguida, Tree of Life.

Thanks be to God, who has given us this victory through Jesus Christ, our Lord. I know that he took upon himself our sins, sorrows, and weaknesses in Gethsemane and carried them to the cross. I know that he suffered and died for me and for you. I know that he came forth from the tomb that first Easter, rising with healing in his wings. May we stand as witnesses of this at all times, in all things, and in all places—preaching Jesus Christ, and him crucified and risen.

Notes

[1] Gaye Strathearn, “Christ’s Crucifixion: Reclamation of the Cross,” Religious Educator 14, no. 1 (2013): 45–57.

[2] Robert L. Millet, “What Happened to the Cross?,” in What Happened to the Cross? (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2007), 105.

[3] Millet, “What Happened to the Cross?,” 106‒7.

[4] Eric D. Huntsman, God So Loved the World (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 66.

[5] Huntsman, God So Loved the World, 66.

[6] Jeffery R. Holland, “None Were with Him,” Ensign, May 2009, 86.

[7] Leon Morris, The Gospel according to John (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1995), 198‒99, 401, 531‒32; Huntsman, God So Loved the World, 84‒85.

[8] Boyd K. Packer, “The Mediator,” Ensign, May 1977, 54‒55; Gordon B. Hinckley, “The Wondrous and True Story of Christmas,” Ensign, December 2000, 4; Stephen E. Robinson, Believing Christ (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 30‒32.

[9] James D. G. Dunn, The Theology of Paul the Apostle (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998), 212‒23, 227‒31.

[10] Dunn, Theology of Paul, 482‒87.

[11] [11] Hayim Halevy Donim, To Be a Jew (New York: Basic Books, 1972), 297.

[12] See the discussion of Douglas J. Moo, The Epistle to the Romans, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1996), 359‒69.

[13] Gordon B. Hinckley, “The Symbol of Faith,” Ensign, April 2005, 4.