Historical Geography

Growth, Distribution, and Ethnicity

Daniel H. Olsen, Brandon S. Plewe, and Jonathan A. Jarvis

Daniel H. Olsen, Brandon S. Plewe, and Jonathan A. Jarvis, “Historical Geograhpy: Growth, Distribution, and Ethnicity,” in Canadian Mormons: History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Canada, ed. Roy A. and Carma T. Prete (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 100-125.

Brandon S. Plewe is an associate professor of geography at Brigham Young University, where he has been teaching courses in cartography and geographic information systems since 1996. He received a bachelor’s degree in cartography and mathematics from BYU in 1992 and then attended the State University of New York at Buffalo for his master’s (1995) and PhD (1997) in geography. His research focuses on mapping historical geography, especially of the western United States and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. His published works include the award-winning Mapping Mormonism: An Atlas of Latter-day Saint History. He served a mission in the New Hampshire Manchester Mission, 1987–89, and has since served in a wide variety of Church callings. He and his wife, Jamie, were married in 1992 and have five children. (Brandon Plewe)

Jonathan A. Jarvis is an assistant professor of sociology at Brigham Young University. He received his doctorate in sociology from the University of Hawaii at Manoa. In his research, Jonathan examines how globalization shapes educational strategies of Asian families in their home country and abroad. His most recent work explores international variations in how family background and structure shape educational outcomes. Jonathan served in the Korea Busan Mission and is presently the first counselor in the bishopric in his ward. He is married to Jodi Bennett Jarvis, and they have one daughter and one son, Talia and Isaac. Jonathan and Jodi are originally from Edmonton and Sherwood Park, Alberta, and presently live in Provo, Utah. (Jonathan Jarvis)

Daniel H. Olsen is an associate professor in the Department of Geography at Brigham Young University. He received his undergraduate degree in geography and history from the University of Waterloo. After completing his master of education (recreation and leisure) at Bowling Green State University in Ohio, he returned to the University of Waterloo to complete a PhD in geography. As a cultural geographer with an interest in tourism studies, his research interests include religious tourism, heritage tourism, and early historical geography of the LDS Church in Canada. Daniel has served as an elders quorum president twice, as a Gospel Doctrine, seminary, and institute teacher on numerous occasions, as Young Men president, as Sunday School president, and as an executive secretary. He served in the Utah Salt Lake City Mission from 1992 to 1994. He and his wife, Janet, are the parents of four children. (Daniel Olsen)

This remarkable photograph, deep with symbolism, was taken at the rededication of the Cardston Alberta Temple in 1991. Centre, Thomas S. Monson, Second Counselor in the First Presidency, with his wife, Frances; left, with scarlet tunic, Staff Sergeant Roy Monroe, a “Mountie” (Royal Canadian Mounted Police); and right, Garry Fox, First Nations chief with full headdress. The LDS Church in Canada has always had a unique tie with Church leaders in Salt Lake City, Utah. Thomas S. Monson, who served as mission president of the Canadian Mission with headquarters in Toronto, 1959–62, and began missionary work in Quebec, would become President of the Church in the 2008. Mounties, in their colourful uniforms and famous musical rides, have become a well-known symbol of Canada, while Latter-day Saints, including Charles Ora Card, who settled Cardston, have felt a particular mission to share the gospel with First Nations people because of their connection with the Book of Mormon. The Cardston Alberta Temple, rededicated on this occasion after lengthy renovations, was the spiritual heart of Mormonism in Canada until other temples were built across the country, starting in the 1990s. (Rod Gustafson, Church News)

This remarkable photograph, deep with symbolism, was taken at the rededication of the Cardston Alberta Temple in 1991. Centre, Thomas S. Monson, Second Counselor in the First Presidency, with his wife, Frances; left, with scarlet tunic, Staff Sergeant Roy Monroe, a “Mountie” (Royal Canadian Mounted Police); and right, Garry Fox, First Nations chief with full headdress. The LDS Church in Canada has always had a unique tie with Church leaders in Salt Lake City, Utah. Thomas S. Monson, who served as mission president of the Canadian Mission with headquarters in Toronto, 1959–62, and began missionary work in Quebec, would become President of the Church in the 2008. Mounties, in their colourful uniforms and famous musical rides, have become a well-known symbol of Canada, while Latter-day Saints, including Charles Ora Card, who settled Cardston, have felt a particular mission to share the gospel with First Nations people because of their connection with the Book of Mormon. The Cardston Alberta Temple, rededicated on this occasion after lengthy renovations, was the spiritual heart of Mormonism in Canada until other temples were built across the country, starting in the 1990s. (Rod Gustafson, Church News)

At the turn of the twentieth century, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Canada consisted of a single isolated colony in southern Alberta, with a few scattered families elsewhere. By 2016, the Church had a strong presence nationwide, with a membership of almost two hundred thousand.[1] This chapter provides a countrywide context for the chapters that follow, which cover the history of the Church in the Canadian regions. It examines the broad trends of Church growth and development, in light of changing policies and practices in Church administration and the evolution of Canada as a nation.

The growth of the Church in Canada is largely a story of how a people and organization with American roots have adapted to the geographic and economic realities of Canada in the face of numerous challenges. Additionally, the Church has come to mirror, albeit imperfectly, the ethnic composition of the country. This has been the result of two important developments. In the early 1960s, proselyting began in French-speaking Quebec, yielding a strong French language contingent. Also, in the mid-1960s, changes in the Canadian immigration policy resulted in a large influx of ethnically diverse immigrants, many of whom were, or have become, members of the Church, so that each ethnic group in the Canadian mosaic is now represented in the Church.

Geography, Weather, and Regions

Geographically, Canada is inherently different in several ways from the United States. While it is larger than the United States, much of its huge landmass is lightly settled. Canada is colder and more strongly regional in culture. Each of these differences has had an impact on the development of the country and has posed challenges for the growth and development of the Church.

Canada is an immense country stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean, over 5,500 kilometres, and from the US-Canadian border to the Arctic Ocean, more than 4,600 kilometres.[2] The second-largest country in the world, next only to Russia, Canada has a landmass of approximately ten million square kilometres (3.9 million square miles) and covers six time zones.[3] Distance has therefore been a major challenge in the development of the Church in Canada. Outside regions with large concentrations of Mormons, such as southern Alberta and major Canadian cities, many Church branches, wards, stakes, districts, and missions cover thousands of square kilometres, making them difficult to administer and grow. Members sometimes have long distances to travel to Church meetings and activities; some are so scattered they are unable to attend at all. Canada has a good system of highways, extending across the country to all but the most remote northerly areas,[4] and extensive railway and air transit systems. Nonetheless, the vastness of the spaces is an ever-present reality. The chapters of this book contain many examples of the influence of these vast distances on Church growth and development and the thousands of kilometres many leaders, members, and missionaries have had to drive, or otherwise travel, in order to administer to their brothers and sisters, to fellowship with other Latter-day Saints, or to attend the temple.

As a northerly country, Canada is colder than the United States. Canada’s vast territory and distinctive regions nonetheless result in great variations in temperatures and weather patterns from region to region. Indeed, Canada shares with the northern United States many of the same weather patterns. Southern British Columbia, for example, has mild weather similar to Oregon and Washington, while the Canadian prairies, like the northern Great Plains area, have very cold winter weather. Likewise, borderland areas in Ontario and Quebec and the Maritime Provinces have climates similar to the US states to the south of them. In general, as one moves northward, the weather gradually becomes colder and agriculture virtually disappears. With 75 percent of the Canadian population living within 150 kilometres of the US border,[5] most Canadians experience weather on average only slightly colder than the northern states of the United States.

Nonetheless, major cities on the Canadian prairies, including Winnipeg, Regina, Saskatoon, Calgary, and Edmonton, have very cold winters, with temperatures occasionally falling as low as –30˚ C (–22˚ F), or even –40˚ C (–40˚ F). Likewise, northern Ontario and Quebec have very cold winters. Mining and governmental services are the chief occupations. Only 122,000 people live in the vast Canadian northern territories—Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut—which stretch from the 60th parallel to the North Pole.[6]

Instances of climatic constraints affecting the growth of the Church in Canada are found in many chapters in this book, where long and snowy winters have created hazardous travelling conditions, have isolated Church members from their normal meeting places, and in some cases, have made it difficult for them to attend Church meetings—a condition only partially alleviated by the advent of automobiles and telecommunications.[7]

That Canada is a nation of several regions[8] has also influenced the growth and development of the Church. The country consists of distinct physical regions based on varied landscape, with drastically different landforms, soils, vegetation, wildlife, and natural resources.[9] These natural differences have influenced the settlement and economic patterns of Canada, with varying degrees of economic development among the regions. Canada is typically divided into six economic regions: British Columbia, the Prairies Provinces, Ontario, Quebec, the Atlantic Provinces, and the northern territories.[10] Historically, the manufacturing core of Canada has been Ontario and Quebec, with the rest of Canada being utilized as a rich resource hinterland, which fed raw resources to Central Canada. However, recent economic trends have caused people from all over Canada to move to Alberta for jobs, particularly in the petroleum industry. The regional economic disparity of Canada has affected migration patterns of Latter-day Saints, which has drawn Church members to areas of economic prosperity from less prosperous regions of Canada, decreasing the LDS membership numbers in those regions.[11] Several of the main regions of the United States extend into Canada, with the result that the administration of the Church in Canada has largely been an extension of the American regions.[12]

Climate, distance, and the regional character of the country have thus made it difficult in many areas in Canada for the Church to reach full organizational and demographic maturity, with each region having its own remarkable story to tell about the establishment and growth of the Church in its area.

In order to trace the growth and diffusion of the Church in Canada, its historical evolution is divided into four time periods: 1890–1918, 1919–55, 1956–90, and 1991–2015. Each period is typified by a distinct pattern of Church growth trends and distribution of members, which have been influenced by Church policy and practice. This influence has affected elements of Church growth, including the shifting of mission and area boundaries, the growth of seminary and institute programs, the creation of young single adult wards and branches, proselytizing in French-speaking Quebec, the creation of language-based wards and branches, and the accelerated construction of temples from coast to coast.

1890–1918: Laying the Foundation

As discussed in the previous chapter, at the turn of the twentieth century, the Mormon colonists in southern Alberta were working hard to establish their new colony. Immigration from Utah was steady (approximately 350 a year), and by the end of 1904 the Alberta and Taylor Stakes had 6,417 members within their boundaries. After 1904, growth continued steadily but because of natural growth rather than immigration. The two stakes added an average of 150 members per year, resulting in 8,928 members at the end of 1918.[13] However, beyond southern Alberta, Mormons were few and far between, with perhaps two hundred members of the Church scattered in a few branches across the rest of Canada, who had little to no contact with each other or with the Church in Salt Lake City.[14]

Maturing Presence in Southern Alberta

After having gained a permanent presence in southern Alberta, Church members attempted to integrate themselves into Canadian society. Therefore, they actively celebrated Canada Day, introduced an adapted Plat of Zion city design,[15] brought expertise in irrigation systems in a massive canal-building project, introduced sugar beets into the prairie region, and later imported rodeos, basketball, baseball, and Scouting from the United States.[16] Church members were instrumental in bringing cultural refinement to southern Alberta, with a strong focus on music, drama, and dancing, culminating in the building of the Raymond Opera House in 1909. The communities of Cardston, Raymond, Magrath, Stirling, Mountain View, Kimball, Leavitt, and several others were established by 1901. A number of other communities were established thereafter as more members from Utah moved into the area.[17]

The first Church building was completed on 29 January 1889 in Cardston, and the Alberta Stake (headquartered in Cardston and later called the Cardston Stake) was established in 1895.[18] Due to an influx of Church members into the region, in 1903 the Alberta Stake was reorganized, and a second stake, the Taylor Stake (headquartered in Raymond) was formed.[19] This was followed by the announcement in October 1912 that a temple would be built in southern Alberta. This pattern of constructing a Church building, establishing a stake, and then building a temple is a process of maturation that had occurred in Utah, Idaho, and Arizona and would subsequently occur in many areas of Canada.

Proselytizing Missions

Since the 1840s, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has organized its proselytizing efforts by dividing the world into missions, in which a mission president directs the work of between a dozen and 250 full-time missionaries, as well as administers to Church members and programs that are not within the boundaries of stakes.[20] It is typically difficult to send missionaries to contact every person within the boundaries of a mission, especially larger missions, due to the limited number of missionaries and because of travel costs. This frequently leads to a concentration of missionary efforts in larger cities and closer to the mission headquarters. This uneven geographical emphasis on missionary work in urban areas has been important in understanding the growth of the Church.

While missionary work in Canada occurred quite early, the effort was based on the doctrine of “gathering,” in which newly baptized Church members were encouraged to travel to the United States to join with the main body of the Church. As such, the majority of early converts to the Church left Canada, and the Church did not have a permanent presence in Canada, outside of a few scattered members, until the arrival of Charles O. Card and his group to southern Alberta in 1887.[21] When Card was called by Church President John Taylor in 1886 to settle in southern Alberta, he was also called as the president of the “Canadian Mission.” The purpose of this mission was mainly colonization, not proselytizing. However, a few Church members from southern Alberta proselytized in Manitoba from 1897 to 1899.[22] There were no known members outside Alberta prior to 1887 except a single family in British Columbia.[23]

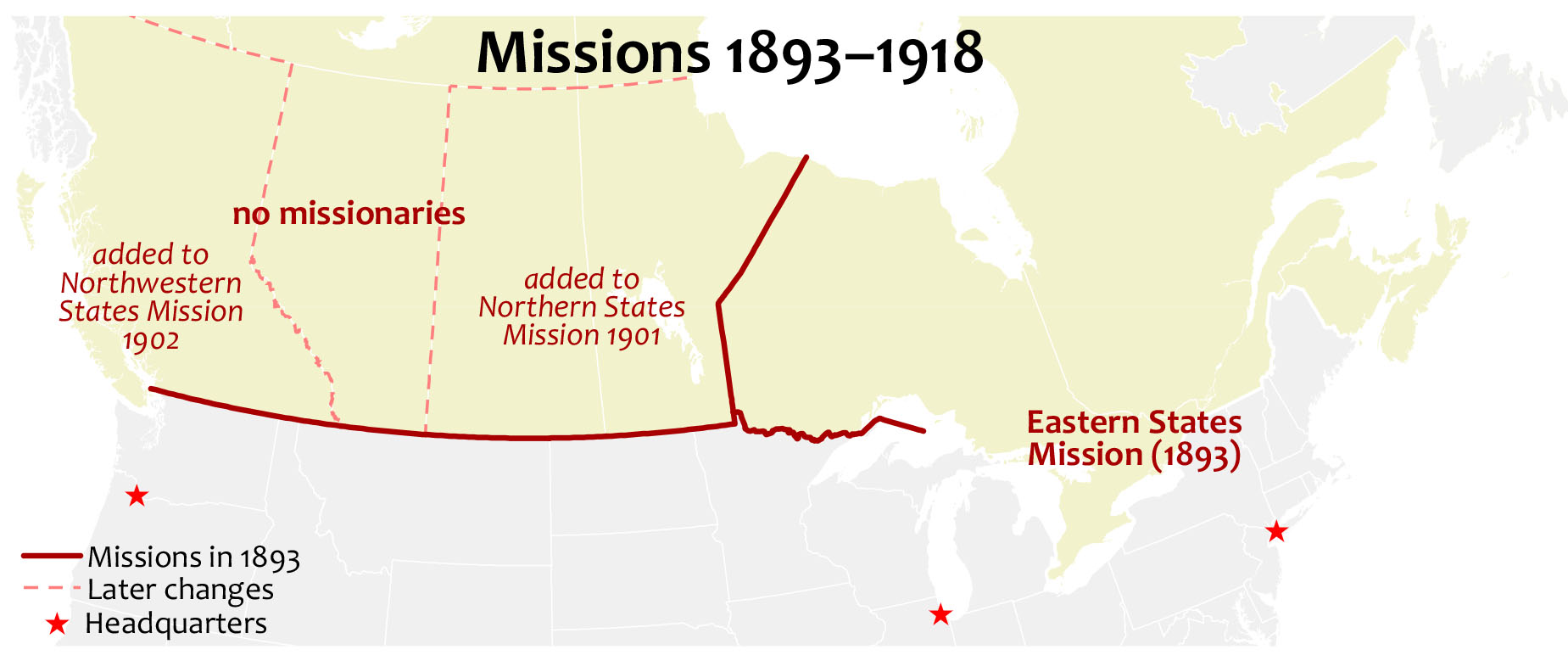

There was no specific organized missionary effort in western Canada until Manitoba was included as a part of the Northern States Mission (based in Chicago) in 1901 and British Columbia became a part of the Northwestern States Mission (based in Portland) in 1902, and even then, missionary activity was conducted on a very small scale. A few individual Church members moved from the United States to Canada to homestead or settle in various locations, but because of their remoteness from each other and from the main body of the Church, these people remained isolated and, in some cases, did not have contact with other Church members for decades.[24] A handful of missionaries of the Eastern States Mission (formed in 1893 and headquartered in New York City), were sent into eastern Canada but had very limited success.[25]

Missionary work in Canada prior to the opening of the Canadian Mission in 1919 was piecemeal and limited in scope. Winnipeg was the first place to receive missionaries in 1879; a branch was formed there in 1910, and the first Church-built building outside of Alberta was completed in 1914.

Missionary work in Canada prior to the opening of the Canadian Mission in 1919 was piecemeal and limited in scope. Winnipeg was the first place to receive missionaries in 1879; a branch was formed there in 1910, and the first Church-built building outside of Alberta was completed in 1914.

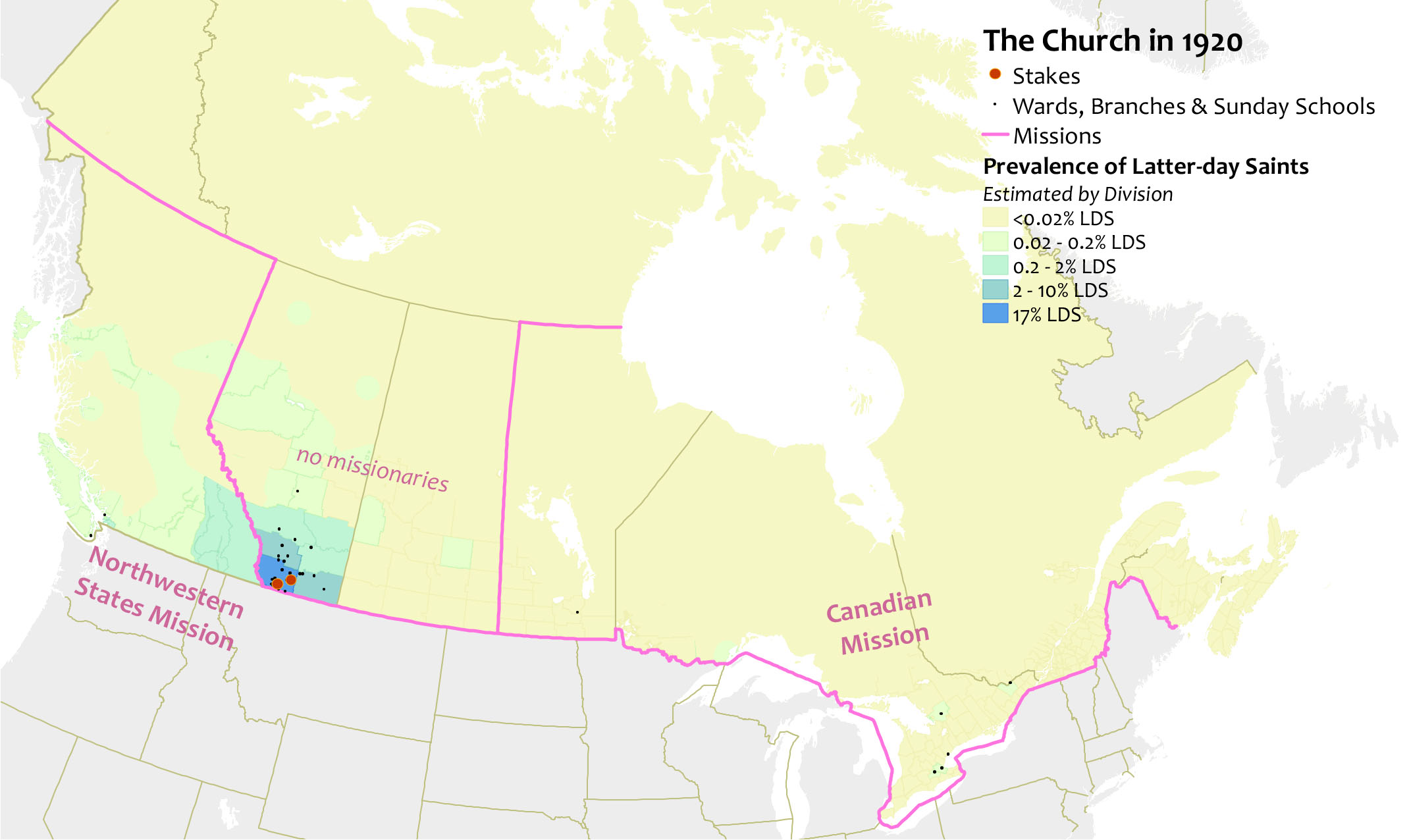

Membership distribution in 1920, illustrates an expanding core in southern Alberta and newly established branches.

Membership distribution in 1920, illustrates an expanding core in southern Alberta and newly established branches.

Church Academies

The Church has a long history of supporting both the secular and spiritual education of its young people. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, with no public education in the frontier territories inhabited by the Saints, the Church built its own schools, called academies. The thirty-six academies, located in the major Mormon settlements across the Rocky Mountain region of North America, were comprehensive schools, sponsored by the stakes, that generally taught at the secondary (high school) level, with some eventually adding college-level courses. The last of the academies to be built was the Taylor Stake Academy in Raymond, Alberta, in 1910, which served as a regional centre. It was later renamed the Knight Academy after the town’s benefactor and founder, Jesse Knight, and became an agricultural school.[26] With the rise of free public education in Alberta and Utah, the need for Church-run schools diminished, and in the 1920s most Church academies were closed except Brigham Young University, LDS University (now LDS Business College), and Ricks College (now BYU– Idaho). The Knight Academy was accordingly closed in 1921, given to the local school district, and became Raymond High School.[27]

The Church Reaches across Canada, 1919–55.

From 1919 to 1955, the Church built up branches in every province through the work of increasing numbers of missionaries and members. Southern Alberta still dominated the country statistically; in 1955, just over half of Canada’s 25,000 members lived south of Calgary. However, growth had slowed significantly there, averaging 1 percent per year, as many young adults moved for education and employment reasons. These two trends of proselytizing and migration led to the Church membership in the rest of the country growing at an average of 11 percent per year. Church membership in urban centres, such as Vancouver, Edmonton, Calgary, and many cities in southern Ontario, grew rapidly during this period.[28]

Establishment of Canadian Missions

On 1 July 1919, the Canadian Mission, headquartered in Toronto, was established. The new mission covered Manitoba and all of Canada eastward.[29] This was a watershed moment in Canadian missionary work and marked the beginning of more concerted efforts by the Church to establish a permanent presence throughout all of Canada. Rather than a few missionaries crossing the border from US-based missions into Canada, missionary efforts became more consistent and widespread, and the number of branches began to multiply. Starting in 1925, the Prairie Provinces began to get more attention from the new North Central States Mission, which was headquartered in Minneapolis, and even British Columbia received more missionaries from the Northwestern States Mission headquartered in Portland, Oregon.[30]

Milestones in the development of the Church in Canada were the establishment of the Canadian Mission in 1919 and the Western Canadian Mission in 1941, allowing for a more concentrated missionary effort in each area.

Milestones in the development of the Church in Canada were the establishment of the Canadian Mission in 1919 and the Western Canadian Mission in 1941, allowing for a more concentrated missionary effort in each area.

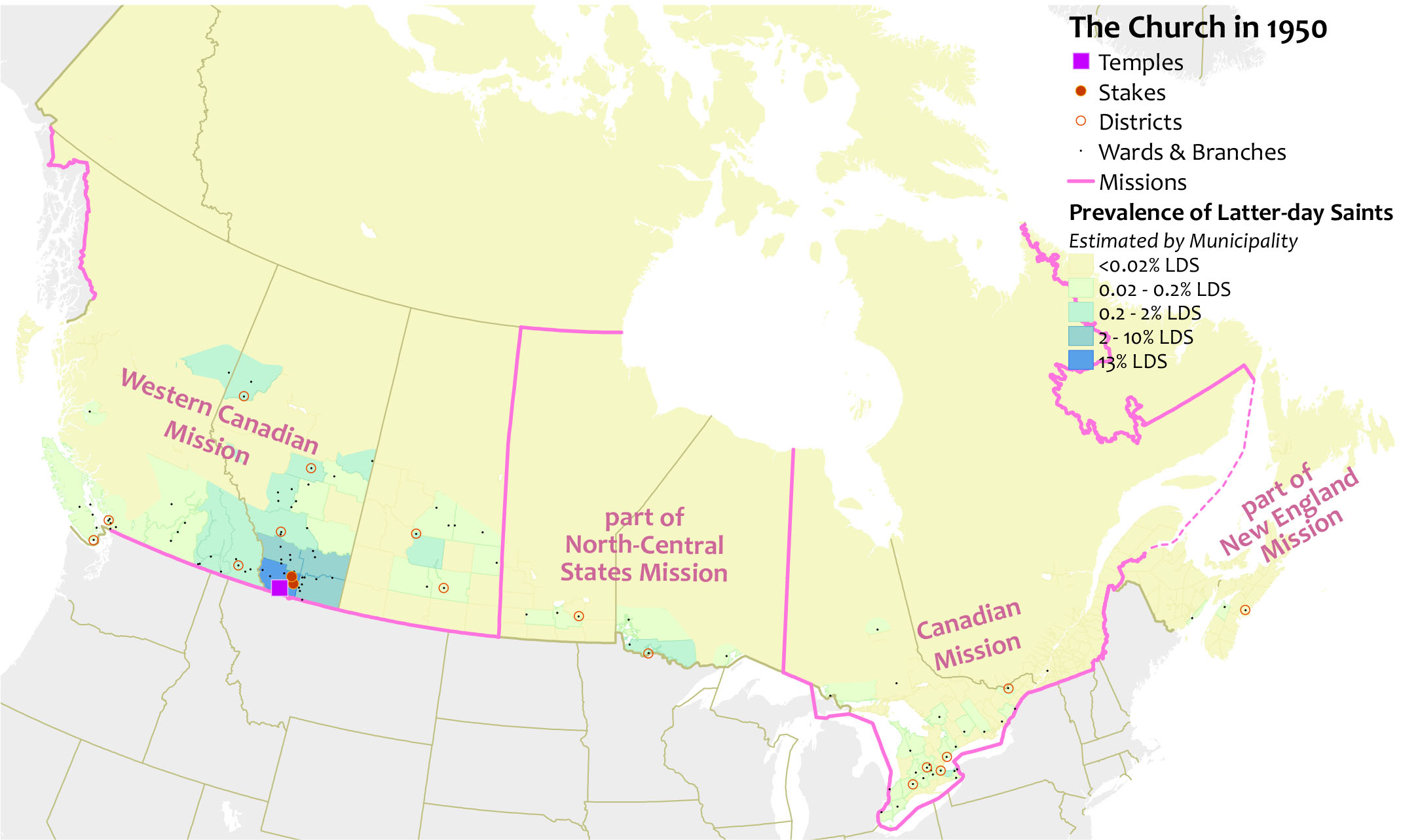

In 1941, the Church created the Western Canada Mission, headquartered in Edmonton, which expanded into Saskatchewan in 1942 and into British Columbia in 1947, helping grow the Church beyond the core in southern Alberta. Conversely, the Atlantic Provinces were taken from the Canadian Mission and placed in the New England Mission in 1937, which reduced missionary attention in this area of Canada (see figure 4-3).[31] The importance of establishing missions is illustrated on the map of Church membership distribution in figure 4-4, which shows great growth of Church membership in southern Ontario, northern Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan, and the southern portions of the Atlantic Provinces.

Outmigration from Southern Alberta

While the dedication of the Alberta Temple in Cardston on 26 August 1923 exemplified the growing influence and maturity of the Church in southern Alberta, many Church families and young adults, especially after the Second World War, left the economically disadvantaged rural southern Alberta settlement for educational and better employment opportunities. This pattern of outmigration mirrored a similar trend in the United States, which, starting a generation earlier in the 1920s, saw a fifty-year surge of membership growth in California dominated by transplants from Utah. In due course, strong Church congregations were established in major cities such as New York City; Washington, DC; Boston; and Chicago; often led by professionals who had been born in Utah but received their education and built their careers in the East.[32]

In Canada, the largest movement was the relocation of Mormon population from southern Alberta northward to the cities, first to Lethbridge (stake in 1921, now three stakes), Calgary (stake in 1953, now seven stakes), Edmonton (stake in 1960, now four stakes), as well as to smaller towns and agricultural areas throughout Alberta and Northern British Columbia. The dominance of southern Albertans in the leadership of the first stakes in Lethbridge, Calgary, and Edmonton is evidence of this movement (see sidebar, “Outmigration and the Midcentury Stakes”). This outmigration also included migrations to cities across Canada, such as Vancouver, Toronto, and Ottawa.[33]

The Church in Canada in 1950 had an increased presence in several urban and rural areas due to decades of increased missionary efforts and migration of experienced leaders from southern Alberta.

The Church in Canada in 1950 had an increased presence in several urban and rural areas due to decades of increased missionary efforts and migration of experienced leaders from southern Alberta.

The similarities and differences of the outmigration in Canada and the United States is exemplified by those who led the local Church. In the United States, the leadership of the new stakes and wards in the Northeast and California of the mid-twentieth century were dominated by transplants from Utah and Idaho, who typically had more Church experience than the local converts. In Canada, the four midcentury stakes in the major cities of Canada showed a variety of patterns. The Calgary and Edmonton Stakes were initially almost exclusively members from southern Alberta, whereas the Toronto and Vancouver leadership was a mix of local converts, southern Albertans, and British immigrants. Thus, leadership from southern Alberta was balanced by local priesthood and a strong British influence that is unique to Canada.

Return migration to Alberta

The movement of Latter-day Saints to Alberta, however, has offset much of this outmigration. While Church leaders in the early twentieth century encouraged members to build up the Church where they lived rather than to gather to Church headquarters in Utah, the practice of gathering continued unabated for several decades and has continued in various forms through to the present. With the dedication of the Alberta Temple, Cardston became a second gathering place for Canadian Latter-day Saints. Church leaders in Winnipeg and Regina, for example, complained in the 1920s and 1930s of the difficulty of building up the Church in their local areas when so many new converts immigrated to Utah and southern Alberta.[34]

In both the United States and Canada, the general trend of population movement during and since World War II has been from east to west. Latter-day Saints likewise have followed this pattern, especially in the movement from depressed areas in the Atlantic Provinces, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba to the dynamic economies of Alberta and British Columbia. The chief beneficiaries of this movement were the stakes in the large western cities of Calgary, Edmonton, and Vancouver. Latter-day Saints moved to these centres for economic reasons, to have association with larger groups of Latter-day Saints, and to have the benefit of the full Church program. The incidence of those who moved has weighed heavily in favour of young single adults seeking education opportunities and employment in a milieu with strong institute and young singles programs; also, young married families were seeking better economic opportunities. Families with teenage children have also “moved west” to give their children the advantage of association with large peer groups anchored in the gospel and stronger Church programs.[35] At the same time, many who earlier left southern Alberta for economic reasons have returned to Alberta to retire in southern towns in order to be near the temple and have closer association with children, grandchildren, and extended family members.[36]

Establishing Multiple Church Centres of Strength, 1956–90

During the latter half of the twentieth century, the Church became firmly established across Canada, as small mission branches became dozens of mature stakes. Proselytizing and migration continued to affect the Church in each province, especially as missionary work was strengthened among the First Nations, French Quebecois, foreign immigrants, and other minorities. Over forty-five years, total membership in Canada increased from 25,000 to 128,000. This steady growth, an average rate of 5 percent per year (i.e., doubling every fifteen years), was almost identical to the eastern half of the United States, which was experiencing very similar trends.[37]

Creation of Stakes

In practice, the ideal size for a Latter-day Saint congregation is between one hundred and three hundred active members—enough members to hold necessary leadership positions yet small enough to feel like a close community and to give everyone an opportunity to participate. Being part of a larger unit, whether ward or branch, has distinct advantages over smaller congregations, such as a stronger support group, implementation of the full Church program, and larger meetinghouses. However, outside of larger urban centres, Church membership in some Canadian congregations is sometimes scattered over hundreds of kilometres.

Two solutions to this challenge have been tried in different parts of Canada at different times. One way was for Church leadership to create smaller congregations (branches) that included only a few Church members, even though that the group was too small to fully operate all Church programs and was sometimes only able to run a Sunday School or Relief Society. This was especially common during the early twentieth century, with small branches of one or two dozen members being created. The second solution was to create congregations that were larger in both area and membership. While this approach required distant members to travel farther to get to Church (and necessitated leaders driving great distances to get to remote members), Church members were a part of a thriving ward rather than a struggling branch.

In missions administering to areas outside of stake boundaries, districts are formed under the direction of a district president, in which branches of various sizes are grouped, each presided over by a branch president. If enough members live in an area, stakes are formed to function at a regional level, coordinating the activities among multiple ward and branch congregations. As the most complete form of local administration, stakes represent the maturation of the Church in a region and are indicative of a sufficient concentration of members in which implementation of the full program of the Church can occur.

When David O. McKay became president of the Church in 1951, the only stakes outside the United States were in southern Alberta and the Mexican colonies.[38] President McKay set forth a new vision of the growth of the Church internationally: the call to gather to Utah, which had been downplayed for forty years, was officially ended, and members around the world were encouraged to build up their branches to become wards and stakes. During the late 1950s and early 1960s, a number of stakes were established outside of North America, including New Zealand (Auckland, 1958), the United Kingdom (Manchester, 1960 and three more in 1961), the first non-English stakes in the Netherlands and Mexico in 1961, Samoa and Scotland in 1962, and later the first stake in South America (São Paulo, Brazil) in 1966.[39] By the time of his death in 1970, President McKay had overseen the creation of thirty-four LDS stakes outside of North America.[40]

Prior to this push for international expansion by President McKay, Canada already had four stakes in southern Alberta: the Alberta Stake (Cardston), the Taylor Stake (Raymond), the Lethbridge Stake (1921), and the Calgary Stake (1953). As part of President McKay’s international initiative, three stakes were established in Canada in 1960 in Vancouver, Edmonton, and Toronto.[41] Another flurry of stake creation took place in the 1970s and the 1980s, as Church membership grew in Canada; in fact, of the forty-eight stakes in Canada in 2015, twenty-one (almost half) were created in the twelve years between 1974 and 1985.[42] (See appendix A for the dates of the creation of stakes.)

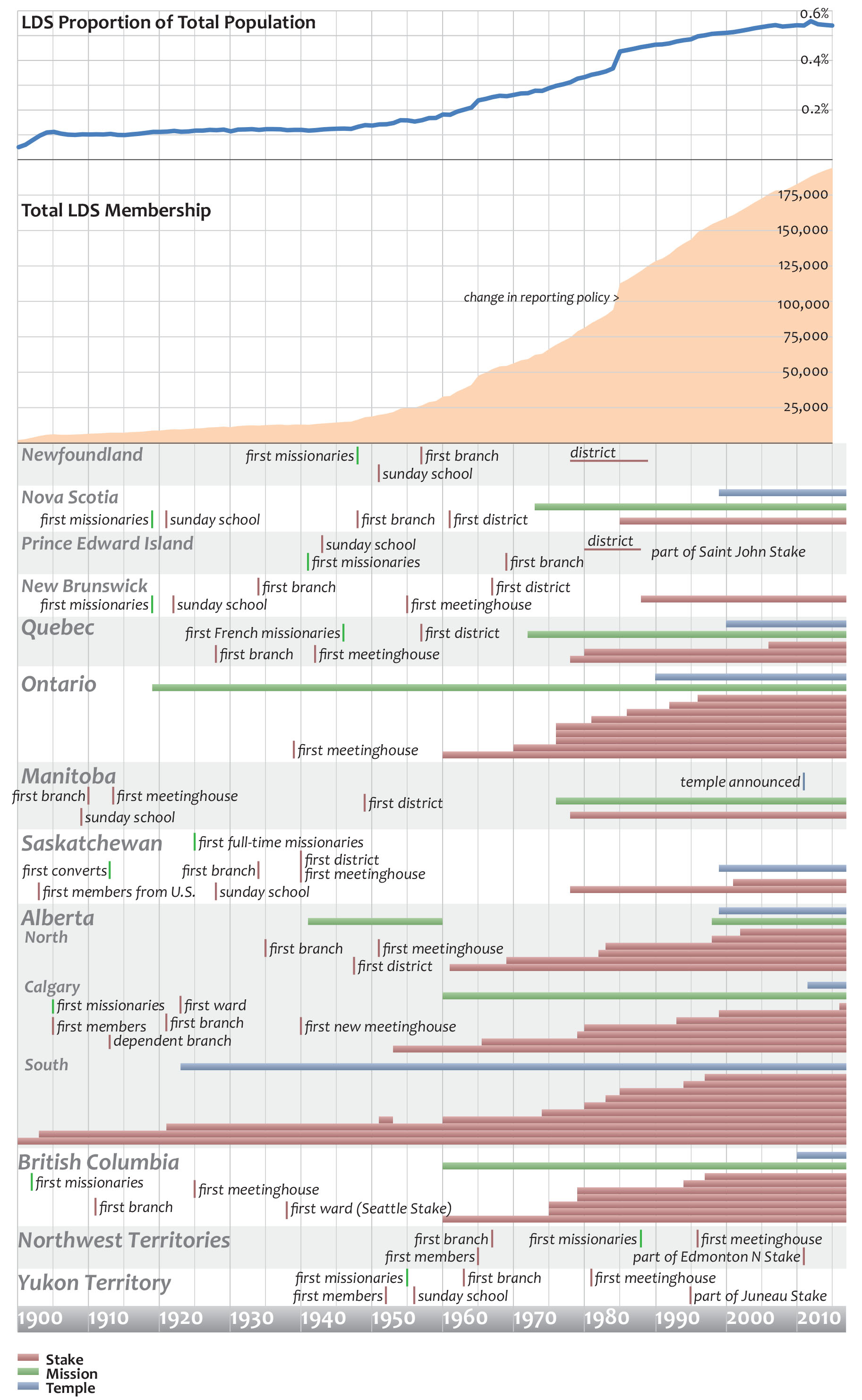

This timeline shows the growth of Church membership in Canada, as well as key moments in the growth of the Church in provinces and territories.

This timeline shows the growth of Church membership in Canada, as well as key moments in the growth of the Church in provinces and territories.

Initially, many of these new stakes were geographically large. The Toronto Stake included most of southern Ontario, while the Saskatoon and Winnipeg Stakes covered their entire provinces. As congregations both in the cities and in the rural areas multiplied, the new stakes formed during the 1970s and 1980s tended to be much more concentrated in the cities whenever possible, with districts covering the most scattered areas. Since then, most of the districts have disappeared and distant branches have been added to the nearest stake. For example, the Whitehorse Yukon Branch is 350 kilometres (but a ten-hour trip including a ferry) from its stake in Juneau, Alaska; the Thompson Manitoba Branch is 750 kilometres (eight hours) from Winnipeg; and the Yellowknife Branch in the Northwest Territories is 1,500 kilometres (fifteen hours driving in the summer) from the Edmonton North Stake Centre.

These geographically larger wards and stakes would have been unmanageable seventy or eighty years ago, especially given the impact of weather on travel in Canada. However, two trends have made this feasible. First, automobiles became more common and roads were improved. Second, communications technology has increased the ability of distant members to keep in touch with the Church, via telephone, satellite in the 1980s, and today through internet communications. Members can watch general conference in their homes in real time, stake conference can be broadcast to remote meetinghouses, and stake leaders can work with branch leaders via videoconference.

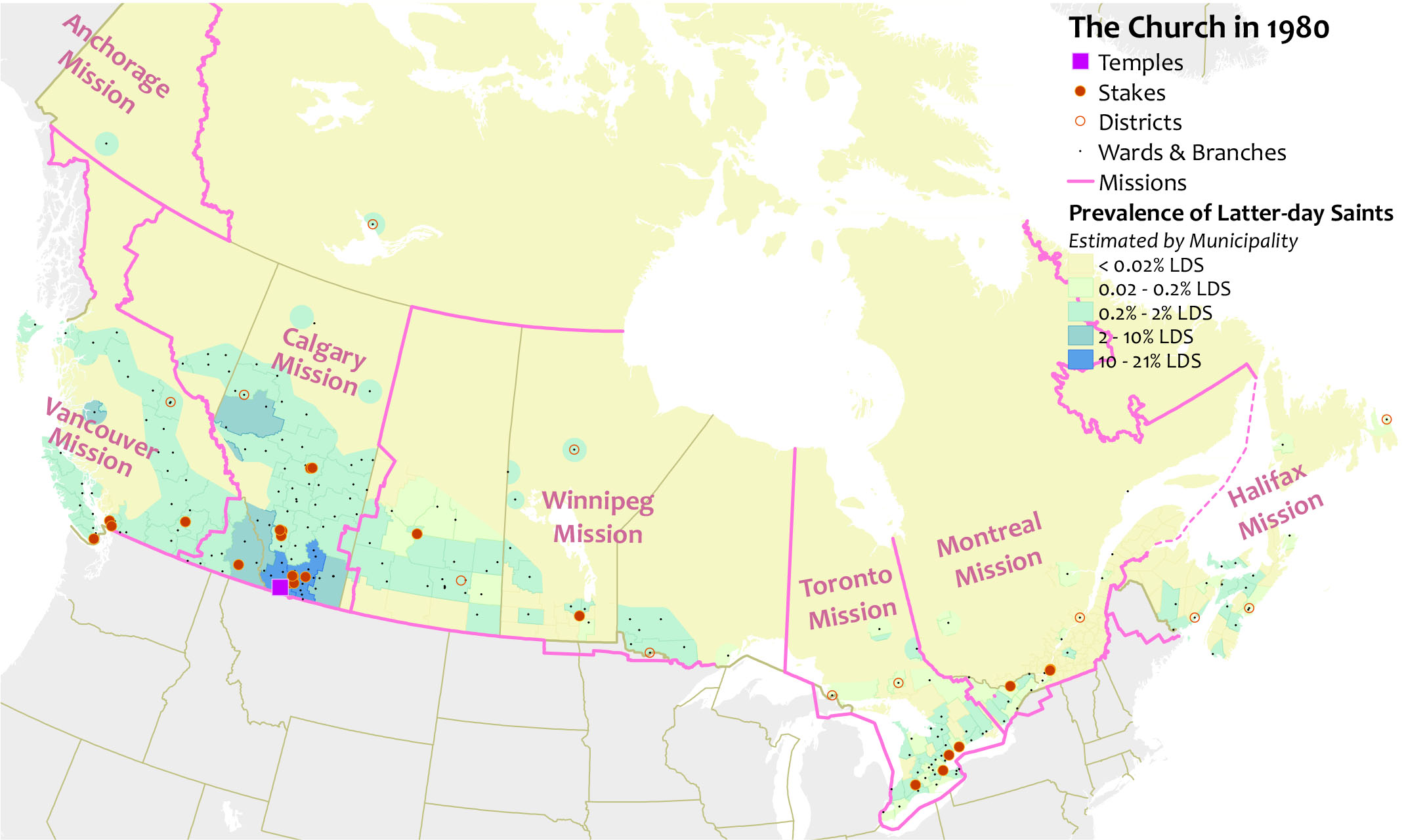

This map shows the remarkable growth of the Church in Canada that occurred between 1950 and 1980 and the establishment of the Church in Canadian cities and towns.

This map shows the remarkable growth of the Church in Canada that occurred between 1950 and 1980 and the establishment of the Church in Canadian cities and towns.

Canadian Missions

In addition to the creation of stakes, there were a number of Canadian missions created during this period. The second mission in Canada, the Western Canadian Mission (originally based in Edmonton, but moved to Calgary in 1960), soon spread to cover all of western Canada, where growth outside the southern Alberta core area had accelerated, particularly in cities such as Vancouver, Edmonton, and Regina (see figure 4-6). In 1960, the Alaskan-Canadian Mission (headquartered in Vancouver) further focused missionary efforts in British Columbia and the Yukon. During the mid-1970s, the Church decided to strengthen its missionary focus in Canada by creating new missions in Montreal (1972), Halifax (1973), Vancouver (1974) (with Alaska and Yukon going to the Alaska Anchorage mission), and in Winnipeg (1976).

In the 1970s and in subsequent decades, several new missions were established across Canada, so that, with a few exceptions, missionary work in Canada was directed from missions headquartered within the country.

In the 1970s and in subsequent decades, several new missions were established across Canada, so that, with a few exceptions, missionary work in Canada was directed from missions headquartered within the country.

The creation/

Regional Administration

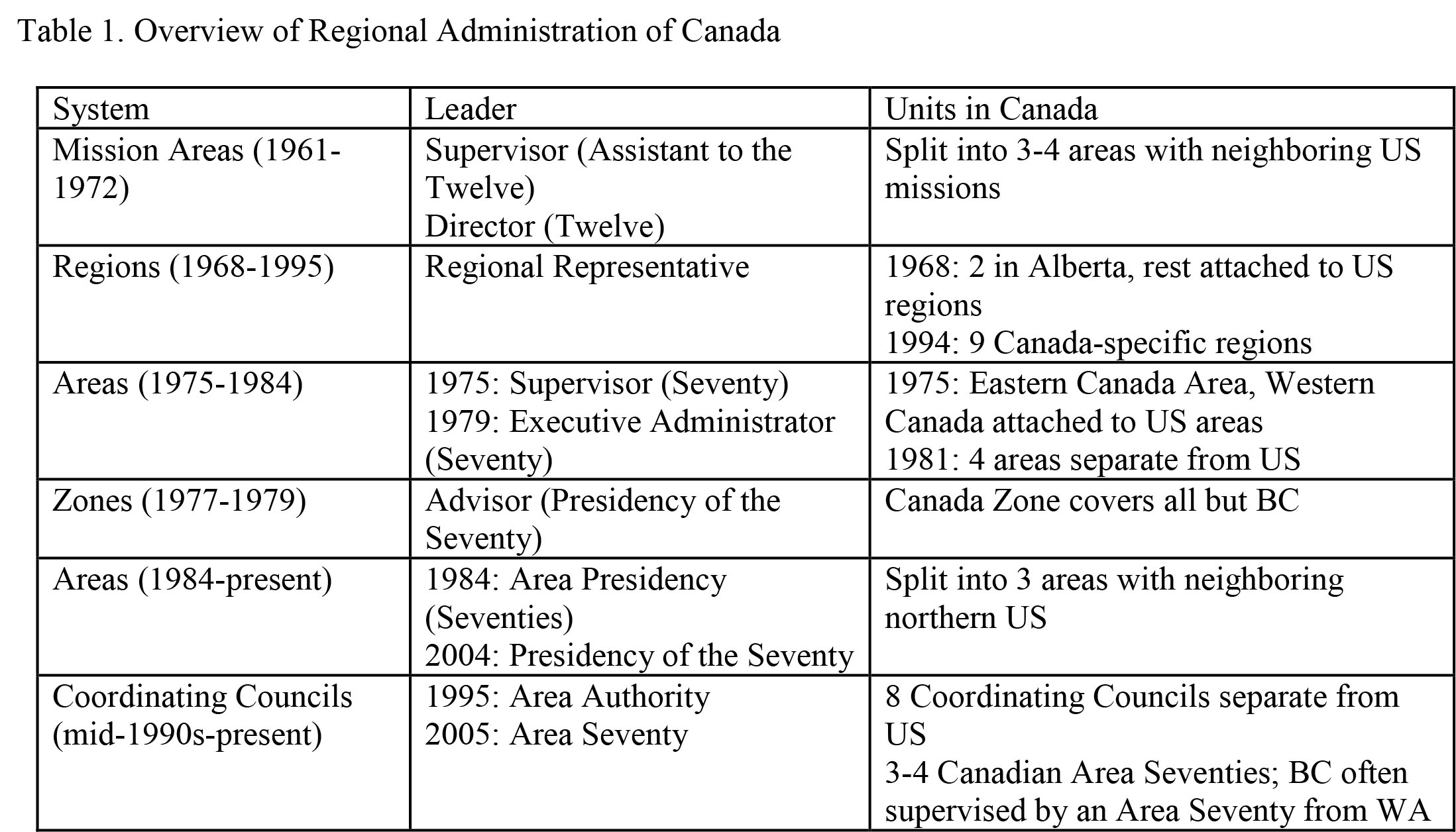

As members, stakes, and missions multiplied in Canada and the rest of the world, Church leaders recognized an increasing difficulty in having the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve directly administer and supervise all of the local leaders. Starting in the 1960s, multiple systems were introduced to build a “middle management” between the general and local authorities. These have generally consisted of regional groupings of stakes and/

Since Canada is a large country whose main areas of population are close to the United States border, it has been simpler, for administrative purposes, to combine Canadian regions with neighbouring US areas.

Since Canada is a large country whose main areas of population are close to the United States border, it has been simpler, for administrative purposes, to combine Canadian regions with neighbouring US areas.

The first administration system was fully developed in 1968 as part of a more general overhaul of all Church practices, known collectively as “Correlation.” The Assistants to the Twelve were each assigned to supervise a Mission Area, consisting of three to five missions, while regions of three to five stakes were overseen by Regional Representatives, who acted primarily as advisors and liaisons between Salt Lake City and local leaders.[44] In Canada, only Alberta had enough stakes to warrant its own regions (Calgary and Lethbridge). To the east and west, Canadian stakes were included in administrative regions based in the United States. All of the Canadian missions were grouped into areas with neighbouring missions in the United States to form Mission Areas.[45]

In 1975–76, the new Church President, Spencer W. Kimball, with N. Eldon Tanner (an Albertan) as a counselor, revised many elements of Church administration, including replacing the regional system. The Assistants to the Twelve were replaced as General Authorities by the First Quorum of Seventy, and the relationship between missions and stakes was standardized. This soon led to a consistent two-level administration of regions (three to five stakes), led by regional representatives (with increased supervisory authority) and areas, which included both stakes (five to ten) and missions (one to five) supervised by members of the First Quorum of Seventy.[46] Eastern Canada (including western New York) was one of the initial areas. As areas multiplied, they were grouped into eleven zones in 1977, including a Canada Zone that included the entire country except British Columbia, but this third level was soon abandoned.[47] By 1983, the sixty-three worldwide areas included four in Canada that covered the country (British Columbia, Alberta, Central Canada, and East Canada), covering ten Canada-specific regions, almost all of which were represented by Canadians.[48] Later, when it was typical for a single Seventy (later restyled “Executive Administrator”) to supervise multiple areas, the Canadian areas were often grouped with US areas.

During the 1980s, it became apparent that the number of areas was growing unwieldy and that local leadership was maturing to the point that direct supervision by General Authorities was not as crucial. In 1984, Gordon B. Hinckley announced a new system of larger areas (initially thirteen) led by a president and counselors from the Seventy with full ecclesiastical authority over their constituent stakes and missions.[49] From then to the present, Canada has been divided into three areas, along with the northern United States: the North America Northeast Area, the North America Central Area, and the North America Northwest Area.[50] In the 1990s, regions were restructured as coordinating councils, and regional representatives were replaced by Area Authorities (now called Area Seventies), local leaders with limited supervisory authority,[51] supervised directly by the Presidency of the Seventy.[52] As of 2016, the forty-eight stakes and two districts in Canada were grouped into eight coordinating councils (which roughly corresponded to the districts of the eight Canadian temples), most of which were supervised by three Canadians serving as Area Seventies: James E. Evanson (Lethbridge), Alain L. Allard (Montreal), and G. Lawrence Spackman (Calgary). British Columbia and southern Alberta have sometimes been overseen by a leader from neighbouring US states, and in 2016, British Columbia was administered by an Area Seventy residing in Washington State.[53]

Despite the changing details, for most of the past several decades, Canada has been administered in a similar way. At the area level, the country has been divided into three sections (British Columbia, the Prairie Provinces, and the East), each combined with adjoining parts of the United States.[54] At the regional level, Alberta and the East have generally been led by Canadians who had previously served as stake presidents.

Seminaries and Institutes

In Utah, Idaho, and Arizona, Church academies were gradually replaced in the 1910s and 1920s by seminaries that provided supplementary religious instruction to students at public high schools. However, it took many years for the practice to reach Canada beyond intermittent classes that were held in local churches in the Taylor Stake after 1929.[55] In 1948, the Alberta (now Cardston) Stake was able to get permission from the school district for released-time seminary at Cardston High School, in which students were allowed to leave the high school for one class per day to attend religious classes taught by a full-time teacher, which was the common practice in Utah and parts of surrounding states. Soon released-time courses were being taught throughout southern Alberta, and by the 1970s, most were meeting in their own buildings. In the 1990s, when Alberta school funding rules (in which schools lost enrollment-based funds when students left campus for seminary) threatened the program, seminary administrators were able to get courses for the Old and New Testament approved for high school credit in some districts.[56]

During the 1920s, increasing numbers of LDS youth in Utah were seeking higher education rather than careers in agriculture or trades. Not all youth could or wanted to attend one of the Church colleges, which led to increased enrollment at other universities. The first Institute of Religion associated with a university was founded in Idaho in 1926, and institutes quickly multiplied at state universities throughout the Mormon core region. The lure of higher education led young southern Albertans to places like the University of Alberta in Edmonton, where an institute was organized in 1952.[57] As with the released-time seminary, the Edmonton Institute had its own building and employed full-time instructors. Institutes were soon created in cities with significant numbers of LDS students, such as Lethbridge in 1958 and Calgary in 1961.[58]

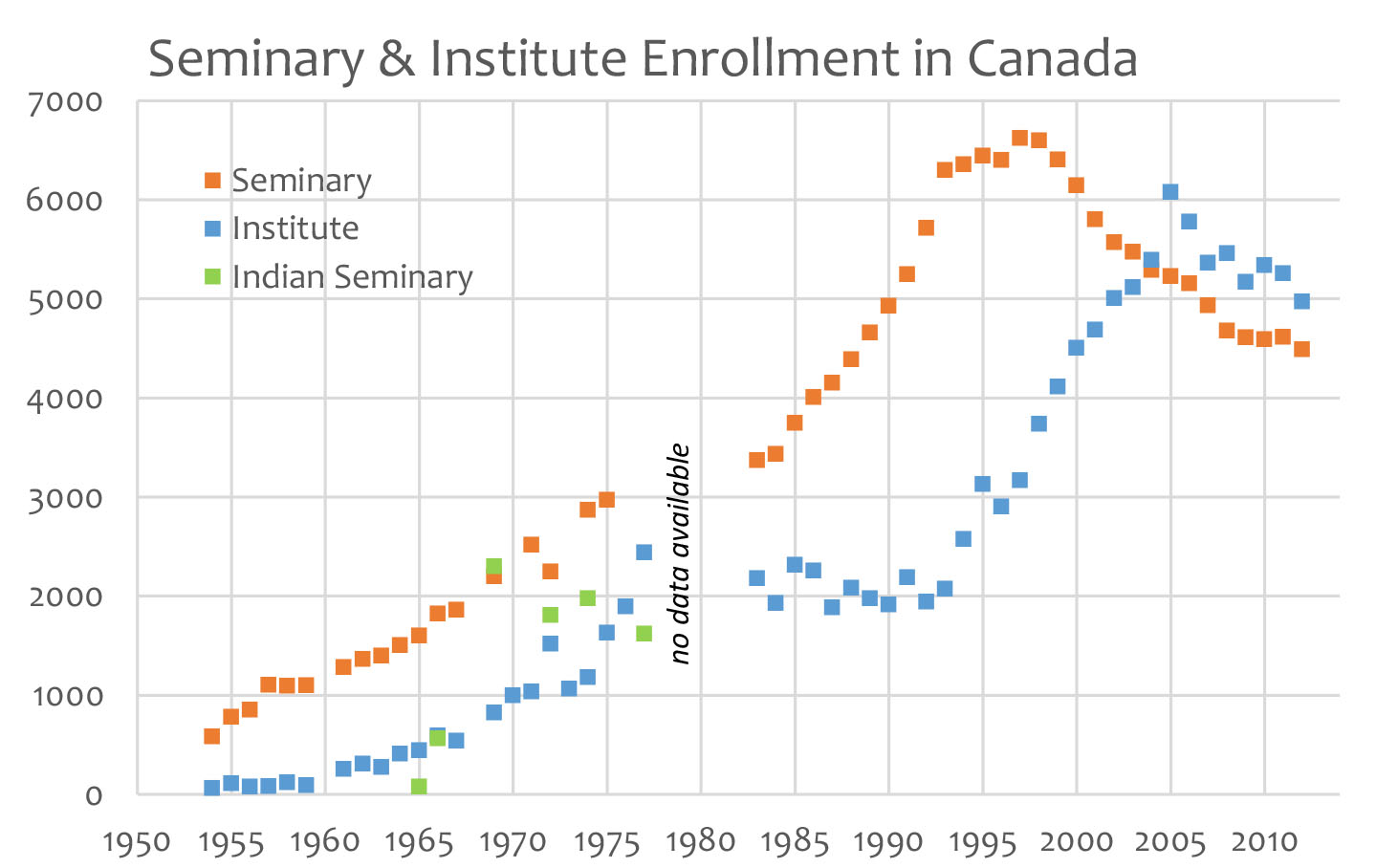

Beyond the core Mormon areas of Western Canada, students typically did not live in sufficiently concentrated numbers to warrant dedicated buildings and full-time instructors, so, starting in the 1950s, they met in ward and branch buildings and were taught by local members outside of school hours (typically in the early morning for seminary and evenings for institute). With the number of stakes doubling in the 1980s, the seminary program grew rapidly, in part because stakes were better able to support early-morning seminary efforts than missions. During the 1990s, growth slowed, and the past fifteen years have seen a significant decline in seminary enrollment. This may be because of two trends: a decline in the number of youth across the country, as Mormon families, like other Canadian families, are having fewer children,[59] and a decrease in the proportion of eligible youth attending seminary.[60]

Total enrollment in seminary and institute in Canada over the past sixty years shows a general increase in keeping with the total Church membership growth but a decline in recent years due to changes in demographics and levels of activity.

Total enrollment in seminary and institute in Canada over the past sixty years shows a general increase in keeping with the total Church membership growth but a decline in recent years due to changes in demographics and levels of activity.

Similarly, institute enrollment was stagnant during the 1980s (probably due to the total number of LDS college students remaining constant) but then tripled in the twelve years between 1993 and 2005. This was largely due to a concerted Churchwide effort to serve young single adult (YSA) members beyond the college campuses, where institute had been previously focused.[61] This included teaching additional institute classes at locations and times tailored to nonstudents and forming YSA wards and branches that were not necessarily tied to a college or university. In fact, twenty-four of the thirty-six YSA wards in Canada were formed during this twelve-year period. The stagnant enrollment since 2005 is reflective of the long-term decline in birth rate in Canada.

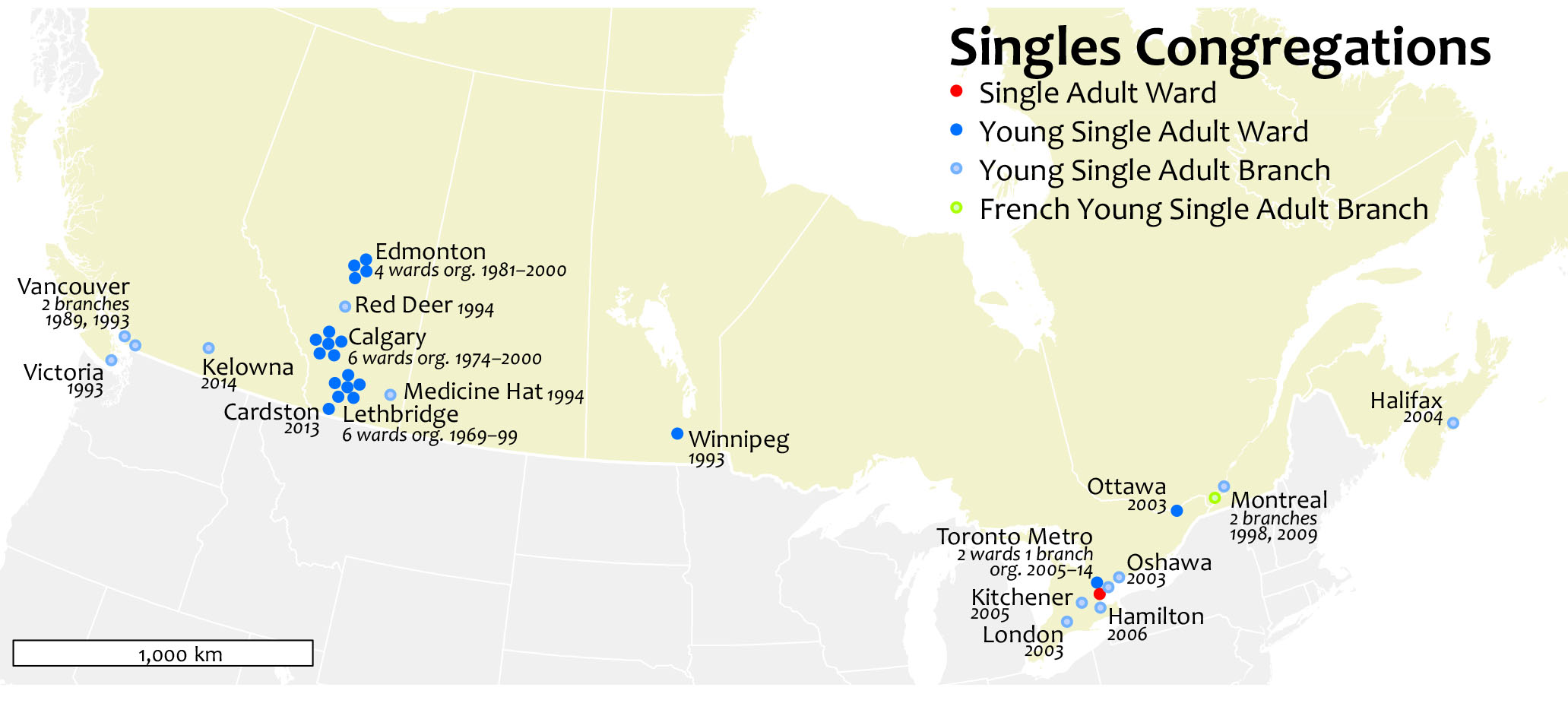

The distribution of young single adult (under age thirty-one) and single adult (over age thirty-one) wards in Canada is primarily concentrated in Alberta, where the Church is well established, and in major cities, to which Mormon young adults are attracted for education and employment and where missionary work among young adults is most successful. Many of these wards were organized during the 1990s as part of a Church wide effort to reach out to young singles.

The distribution of young single adult (under age thirty-one) and single adult (over age thirty-one) wards in Canada is primarily concentrated in Alberta, where the Church is well established, and in major cities, to which Mormon young adults are attracted for education and employment and where missionary work among young adults is most successful. Many of these wards were organized during the 1990s as part of a Church wide effort to reach out to young singles.

The administration of seminaries and institutes in Canada has followed a similar pattern to other aspects of regional Church administration. The Church Educational System, a Church department that is responsible for the religious and secular education mission of the Church, is divided into areas, each with a director (often one of the local instructors). At first, only the released-time seminaries in southern Alberta formed their own area; the rest of Canada was divided among areas in adjoining parts of the United States. Although the locally administered area gradually expanded to the three Prairie Provinces, British Columbia was still an appendage to Washington and Oregon, and the Eastern Provinces were joined with the Northeastern United States. Due to increasing difficulty in managing the different human resources policies of the two governments, especially for American instructors in Canadian seminaries and institutes, a separate Canada Area was created in 2002. While this new Canada Area has not necessarily meant continued growth in terms of seminary and institute enrollment, the change has eliminated the transfer of CES employees between the United States and Canada, with consequent human resource issues (i.e., unequal salaries, transfer of benefits between the two countries, and so forth).[62]

Work among First Nations Peoples

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a history of missionary work among the native inhabitants of North America, largely due to the belief that the Book of Mormon tells the history of at least some of their ancestors and contains promises for those who follow the gospel of Jesus Christ. After significant but sporadic missions to the “Lamanites” in the United States during the nineteenth century, there was little effort among the Native Americans until the establishment of the Navajo-Zuni Mission in 1943.[63] The renewed focus on preaching to Aboriginal peoples rapidly spread across the western United States and Canada.

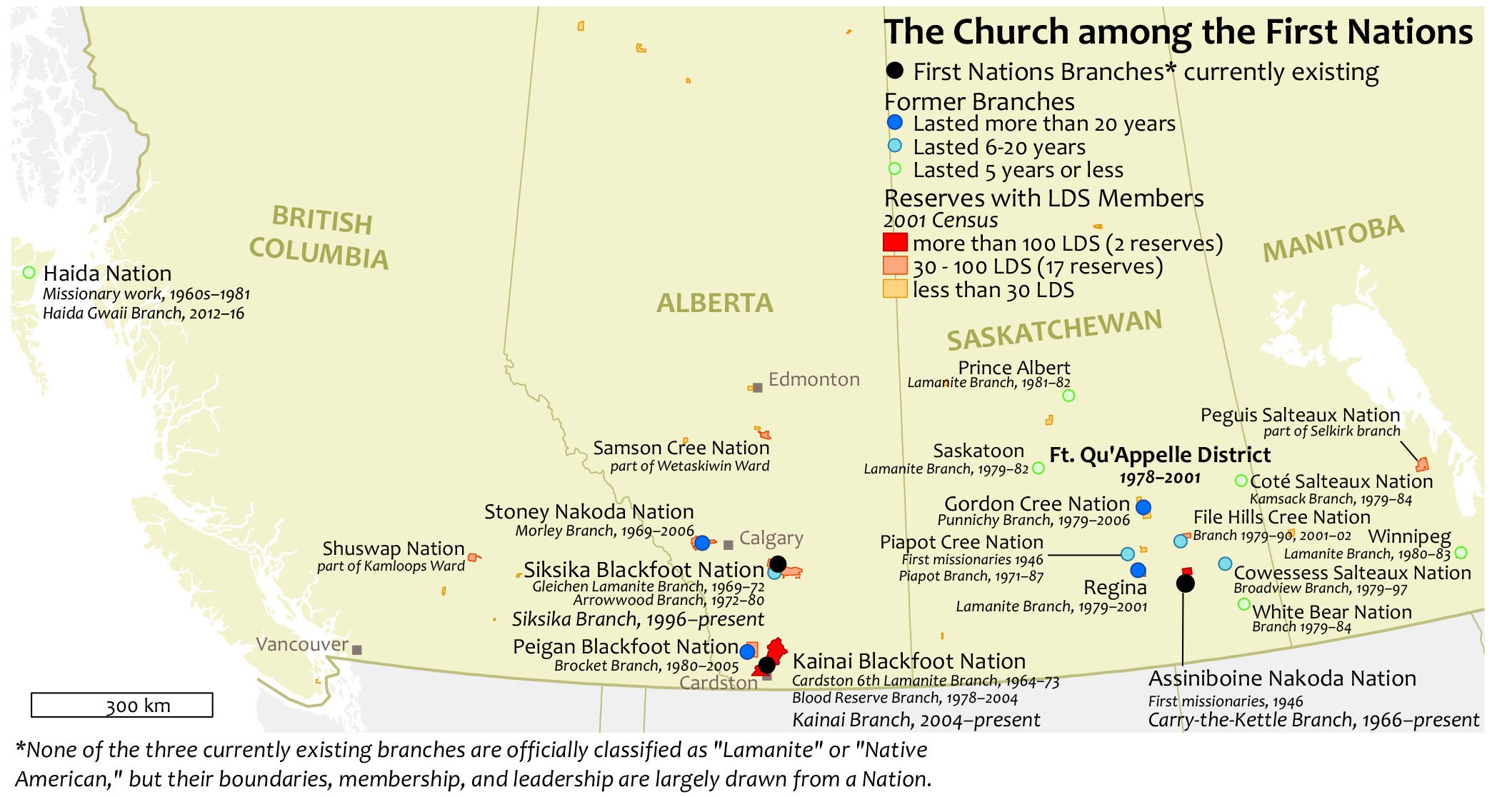

Map showing Aboriginal branches in Western Canada in 2016.

Map showing Aboriginal branches in Western Canada in 2016.

In Canada, proselytizing efforts generally mirrored practices adopted in the United States, with full-time missionaries and nearby members called to teach on First Nation reserves and help strengthen the priesthood leadership. Missionaries taught Aboriginal people who had moved to cities such as Regina and Saskatoon. The effort intensified during the presidency of Spencer W. Kimball, whose Arizona roots gave him a special love for Native Americans.[64] By the early 1980s, there were at least fifteen Lamanite branches across Western Canada, with most being part of the First Nation–specific Fort Qu’Appelle District in Saskatchewan. Missionary work was strongest in Saskatchewan, which has the largest Aboriginal population in the country,[65] and in Alberta, where large Mormon populations were living near Indian reserves (see figure 4-10).[66]

A second program earlier applied in the United States was Indian Seminary. In the United States, the Church began holding seminary, welcoming both members and nonmembers, at government boarding schools built for Native Americans in the late 1950s, especially those to which Church members were being brought, such as the Intermountain Residential School in Brigham City, Utah.[67] By the early 1960s, Indian Seminary was a key component in the renewed missionary effort among the Native Americans, with seminaries on many reservations in the Southwest and the Great Plains.[68] During the mid- to late 1960s, local Canadian members and CES administrators brought the idea to Canada, starting seminaries on Aboriginal reserves across British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and in Ontario in 1970. In Canada, Indian Seminary was usually taught by seminary instructors and missionaries in homes and in meetinghouses.[69] The program was rather successful, reaching an enrollment of one thousand in 1972, but gradually dissipated after the Church decided to phase out Indian Seminary as a separate program in 1982 when the US government closed its off-reservation boarding schools.[70] Since then, branches on and near reserves typically hold early-morning seminary just like the wards and branches around them.[71]

The Indian Placement Program (in which students boarded with member families during the school year) was also adapted from the United States. Many native youth and their families joined the Church through these programs, and they received a better education (both spiritual and secular) than was otherwise available. However, this program became embroiled in the larger national debate in the United States about the degree to which First Nations members should, or could, be assimilated into white culture, and the programs were eventually closed.[72]

First Nations multigenerational family culture is depicted in this colourful scene in the 2007 Vancouver cultural celebration, “Every Nation, Every People,” put on for the public by the three Vancouver stakes. (John McCulloch)

First Nations multigenerational family culture is depicted in this colourful scene in the 2007 Vancouver cultural celebration, “Every Nation, Every People,” put on for the public by the three Vancouver stakes. (John McCulloch)

The long-term results of the outreach to the First Nations has been mixed. After President Kimball’s death, the missionary focus seems to have gradually declined (as did the Church policy of independent “Lamanite” congregations). Many of the branches struggled to develop independent strength, and by the 1990s, most were closed and the members assigned to the nearest wards and branches. That said, First Nations members are strong participants in many of the congregations of western Canada, and three independent branches have survived (see figure 4-10) with strong aboriginal leadership and growing membership. There are also renewed efforts to preach among the First Nations, such as the Haida Nation on Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands) in British Columbia.

Maturity and Stability, 1991-2015

During the twenty-five years from 1991 to 2015, the Church in Canada experienced both the positive and negative effects of growing maturation. While the Church continued to grow throughout the period, the rate of Church growth decreased substantially. Statistics show that the growth in total Canadian membership, from 128,000 in 1991 to 194,000 in 2015, represents an annual increase of 1.7 percent per year, which was significantly slower than the growth rate of Church membership in the eastern United States (2.6 percent per year) and slightly below that in Europe (1.9 percent).[73] In a positive way, maturity has greatly improved the ability of Mormons across Canada to realize the full blessings of the gospel, especially through the building of temples in many cities. As well, congregations serving singles and non-English speakers have multiplied.[74]

Temples

President Gordon B. Hinckley’s announcement at the April 1998 general conference of a program to build thirty smaller temples[75] resulted in the building of four new temples in Canada—in Halifax, Regina, and Edmonton in 1999, and in Montreal in 2000. The creation of smaller temples was spurred in part because Church leaders realized that in many parts of the world, including Canada, distance was an obstacle for temple attendance. This was certainly the case in Canada, where many members of the Church had to travel many hours to attend a temple in either Cardston or Toronto or in the United States. Prior to the announcement of these smaller, less-expensive temples, Church policy held that temples were to be built close to large concentrations of multiple stakes.[76] Such temples were convenient to members living in those urban areas, but not for members living at a significant distance. However, with the concept of building smaller temples, more temples were built in areas that included one or two stakes. This was an important development, particularly for very large stakes that covered a large territory and generally lacked the requisite membership numbers for a large temple to be built within the stake boundaries.

In the twenty-first century, two new midsize temples were dedicated, in Vancouver in 2010 and in Calgary in 2012, to accommodate the larger number of Saints living in these two metropolitan areas, bringing the number of temples in Canada to eight, with temples stretching from coast to coast. Prior to the announcement of the Winnipeg Manitoba Temple in 2011, Church members from the Winnipeg Manitoba Stake, which covers the entire province of Manitoba, had to drive six hours or more one way to attend the Saskatchewan Regina Temple. After a long delay related to difficulty in obtaining a site, ground was broken for the Winnipeg Manitoba Temple in December 2016, to the great delight of Church members in Manitoba, excited about the prospect of having a temple in their stake.[77]

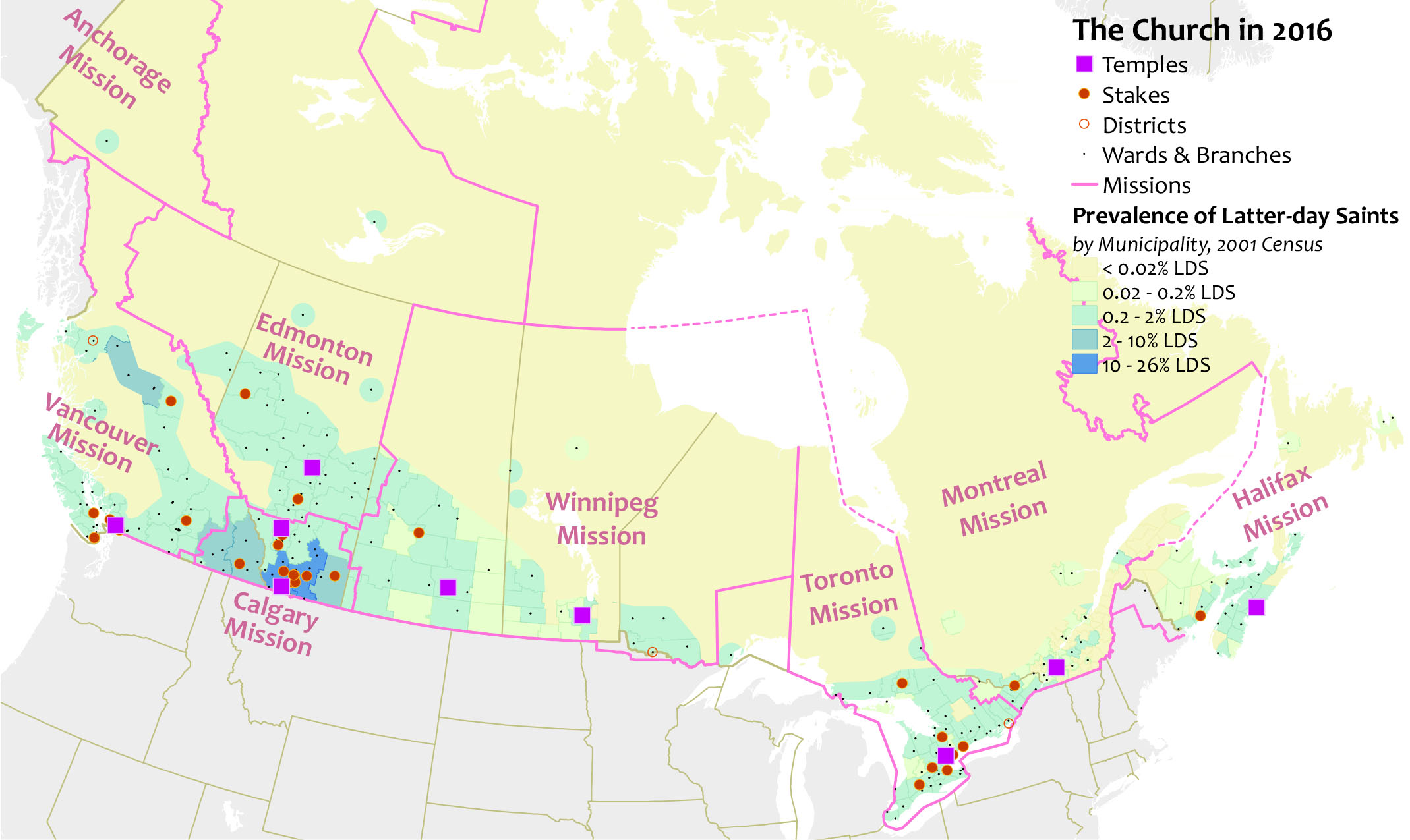

Since 1990, the general trend has been toward the development of new centres of strength across the country. While the percentage of Church population living in Alberta has decreased from 52.9 percent in 1965 to 41.6 percent in 2015,[78] Alberta has remained a bastion of strength, in which Latter-day Saints occupied 2.3 percent of the province’s total population in 2012, still the highest in Canada. Neighbouring provinces, British Columbia and Saskatchewan, had the next highest percentages of LDS at .067 and .054 percent respectively.[79]

Since 1990, the general trend has been toward the development of new centres of strength across the country. While the percentage of Church population living in Alberta has decreased from 52.9 percent in 1965 to 41.6 percent in 2015,[78] Alberta has remained a bastion of strength, in which Latter-day Saints occupied 2.3 percent of the province’s total population in 2012, still the highest in Canada. Neighbouring provinces, British Columbia and Saskatchewan, had the next highest percentages of LDS at .067 and .054 percent respectively.[79]

An Era of Stability

While Church membership has increased in Canada at a steady pace since 2001, at a rate of approximately 1.7 percent, as compared with an overall Church rate of 2.1 percent,[80] the number of new stakes created in Canada has slowed down, as most of the populated areas of Canada are now covered by a stake or mission. Since 2001, only four stakes have been created. On the other hand, two new temples have been dedicated, with the Winnipeg Manitoba Temple, as noted above, being built.

In 2011, the Toronto East and West Missions were consolidated by Church leaders as a part of a worldwide realignment of the limited missionary resources of the Church to more successful areas; worldwide, twenty-four missions were closed between 2009 and 2011, especially in Europe and Eastern North America.[81] After Church leaders lowered the age requirements for missionaries in October 2012, for men from nineteen to eighteen, and for women from twenty-one to nineteen,[82] the missions in Canada saw an increase in the number of assigned missionaries. So far, the results of an increased missionary force have been similar to results in the rest of the world: very little change in the overall number of convert baptisms. However, members and missionaries are placing a greater emphasis on reactivation efforts rather than on convert baptisms.[83]

Cultural Diversity

The cultural and linguistic diversity of Canadian Mormons in 2015 reflected the bilingual nature of the country and its multicultural origins, deriving from Canada’s immigration history. The first large wave of LDS immigrants to Canada took place in the 1880s in southern Alberta. Most of these settlers arrived from towns in Utah. Mormon settlers reflected the general Church population of the time and consisted mostly of American and European-born persons, many of whom were from Great Britain. Traditionally, migration has been of two types among Latter-day Saints in Canada: migration from small places of initial settlement in Alberta to cities further north in the province and to larger places throughout the country; and migration of LDS persons from European countries and the United States. These factors have meant that well into the post–World War II period, the ethnic makeup of Church membership in Canada was of British and European extraction, with a small minority of First Nations people represented.

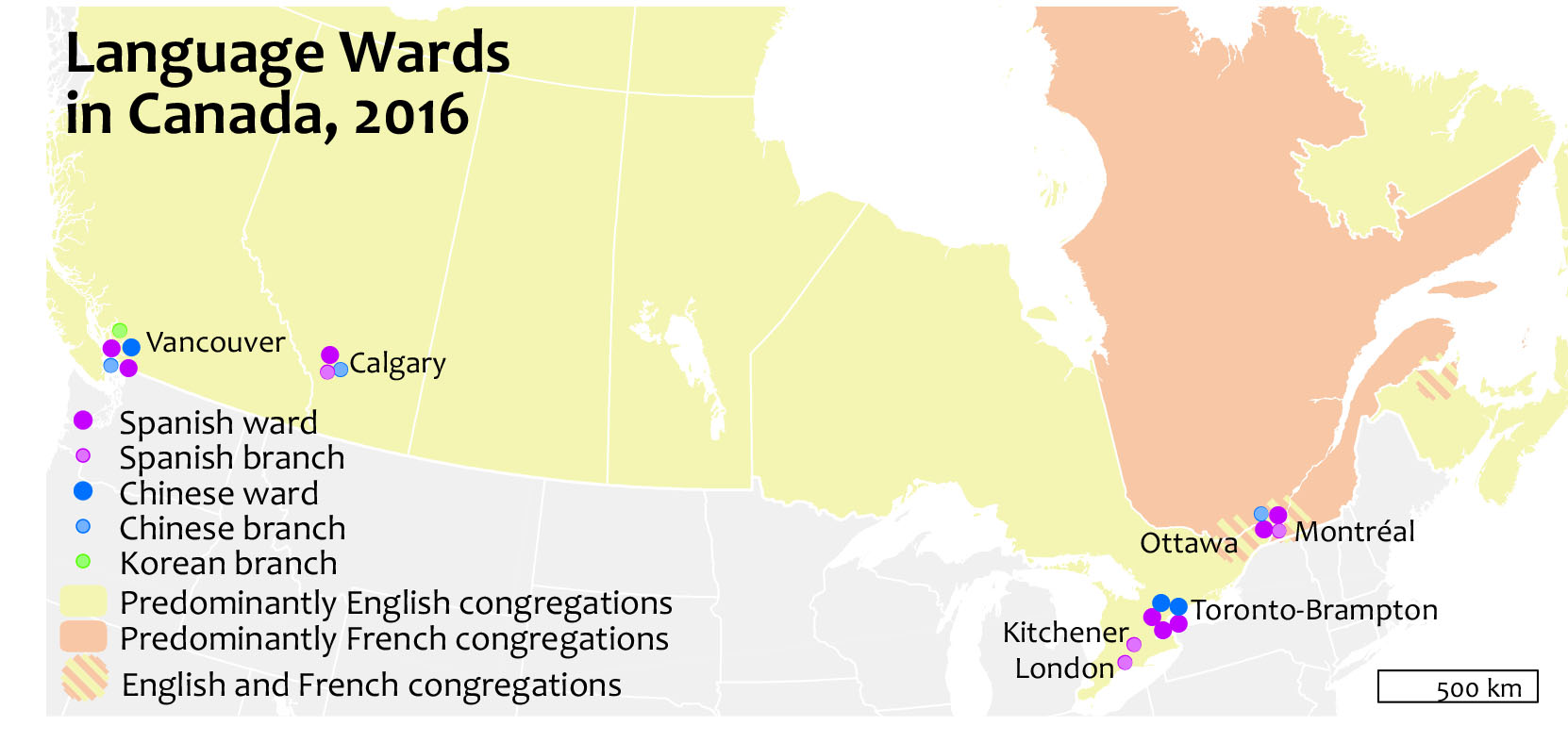

Two major developments in the 1960s and subsequent decades changed the cultural makeup of the Church in Canada: the successful launching of missionary work in the French-speaking part of Quebec, which eventually yielded two French stakes, and the change in immigration policy of the Canadian government that led to the influx of vast numbers of ethnically diverse people, particularly in the big cities. Although many linguistic groups did not have a sufficient number to form their own branches and wards, and thus needed to be integrated into either French- or English-speaking wards, some language-speaking units were established in all the major cities to accommodate the linguistic and cultural needs of groups from Asia and North and South America.

Extension of Gospel to French-speaking Quebec

Missionary work in Quebec began in earnest when Thomas S. Monson, president of the Canadian Mission, headquartered in Toronto, sent six French-speaking missionaries to begin proselytizing in the French-speaking part of Montreal. Prior to the mid-1960s, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints had a minimal presence in the province of Quebec, with branches of the Church only among the English-speaking population, which itself constituted only 20 percent of the total population of la belle province.[84]

Profound changes to Quebec society in the 1960s, a period commonly referred to as the “Quiet Revolution,” prepared the way for a new era of rapid Church growth in the 1970s. This included the widespread exposure of the Church and its teachings in the Mormon Pavilion at the Man and his World Exposition in Montreal in 1969–70. The Church also began to establish itself in several significant ways among the French population: a more extensive missionary program with all missionaries trained in the French language, the translation of Church general conferences into French, plus an active building program that provided Latter-day Saints with their own places of worship. Most important of all was the creation of French-language Church units, or branches, which began during these years. The first branches in Montreal (1964) and Quebec City (1969) and the creation of the all-French Quebec District in 1974 fostered the growth of the Church among the French-speaking majority and paved the way for a more permanent Latter-day Saint French-speaking community in Quebec. The French-speaking Montreal Quebec Stake was formed in 1978, the Montreal Mount Royal Quebec Stake (English speaking) in 1980, and the Longueuil Quebec Stake (second French-speaking stake), covering Montreal and the northern and northeastern part of the province, was formed in 2006. The crowning achievement was the dedication of the Montreal Quebec Temple in 2000, with worship sessions serving the increasingly ethnically diverse LDS population. [85]

With a population of more than eleven thousand in 2016, the Church in Quebec had become more visible and was now ready to make a significant contribution to mainstream society. While the proportion of Church members in Quebec is still very small in terms of the total population—approximately 35 percent of what it was in Ontario—there was now a robust French-speaking contingent in the province and the foundation had been laid for future growth and development.[86]

The Montreal Quebec Temple was rededicated after renovation in December 2015, to the great joy of those who could once again enjoy the full blessings of the temple without extensive travel. (Catherine Jarvis)

The Montreal Quebec Temple was rededicated after renovation in December 2015, to the great joy of those who could once again enjoy the full blessings of the temple without extensive travel. (Catherine Jarvis)

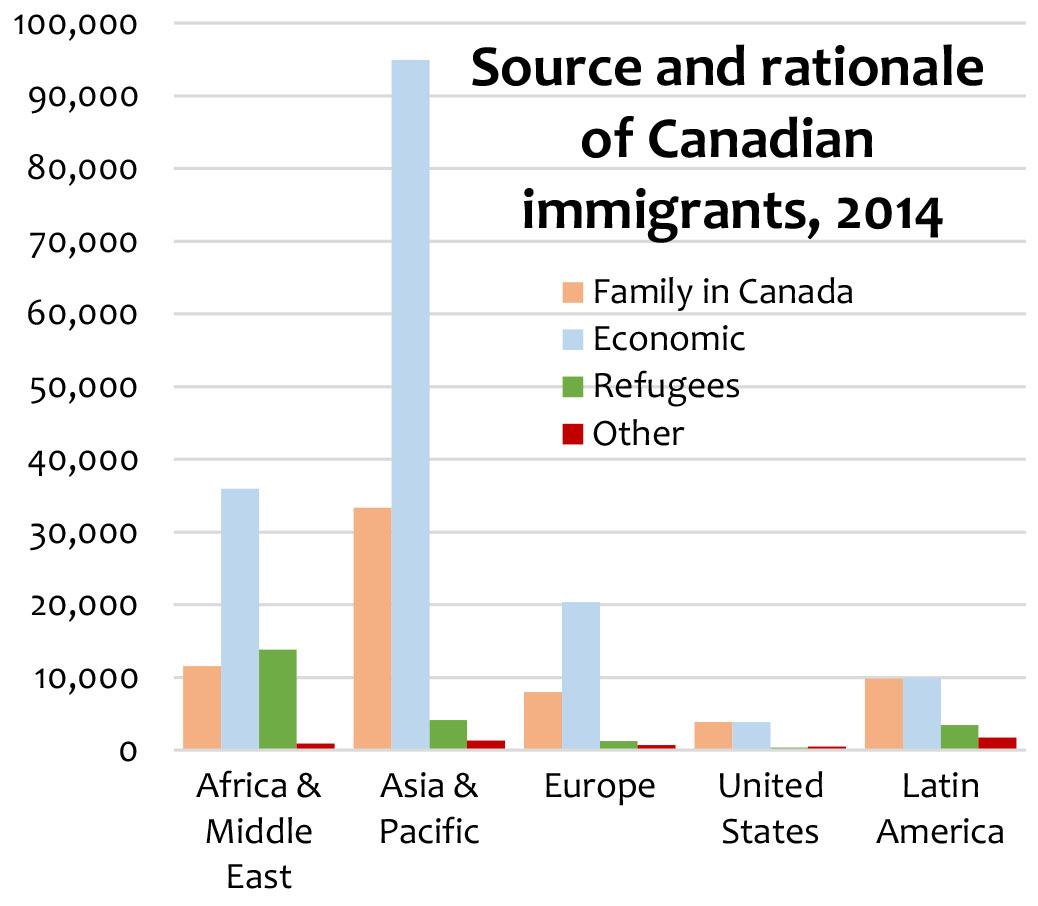

International Migration

The changing pattern of Canadian immigration since the mid-1960s has altered the ethnic, linguistic, and cultural composition of the country and had a significant impact on the ethnic composition of the Church. As the composition of immigrants to Canada has changed due to government policy, the population of the Church has changed within the overall population. For many who immigrated, the Church was a fresh spiritual experience and offered chances for community and economic adjustment. New immigrants, therefore, have more often been drawn to the gospel as converts. Because today immigration from other countries tends to target larger cities in Canada, this is reflected in Church membership. This has not only necessitated the integration of these groups into dominantly English-speaking or French-speaking congregations but has also led to the creation of nearly twenty wards and branches across the country to deal with the linguistic needs of these groups.

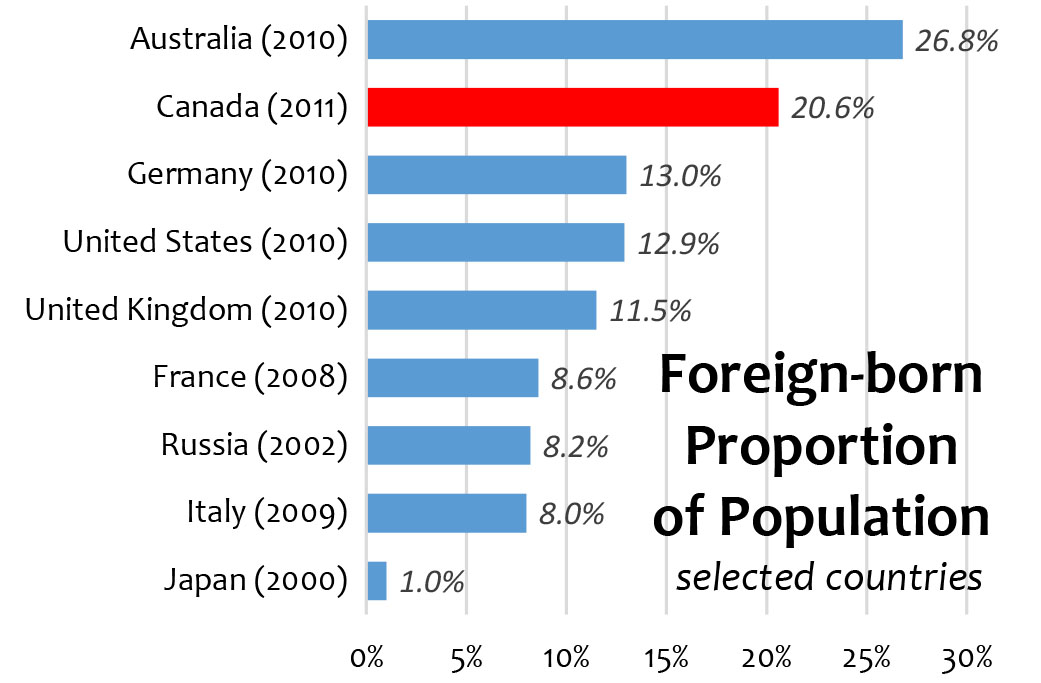

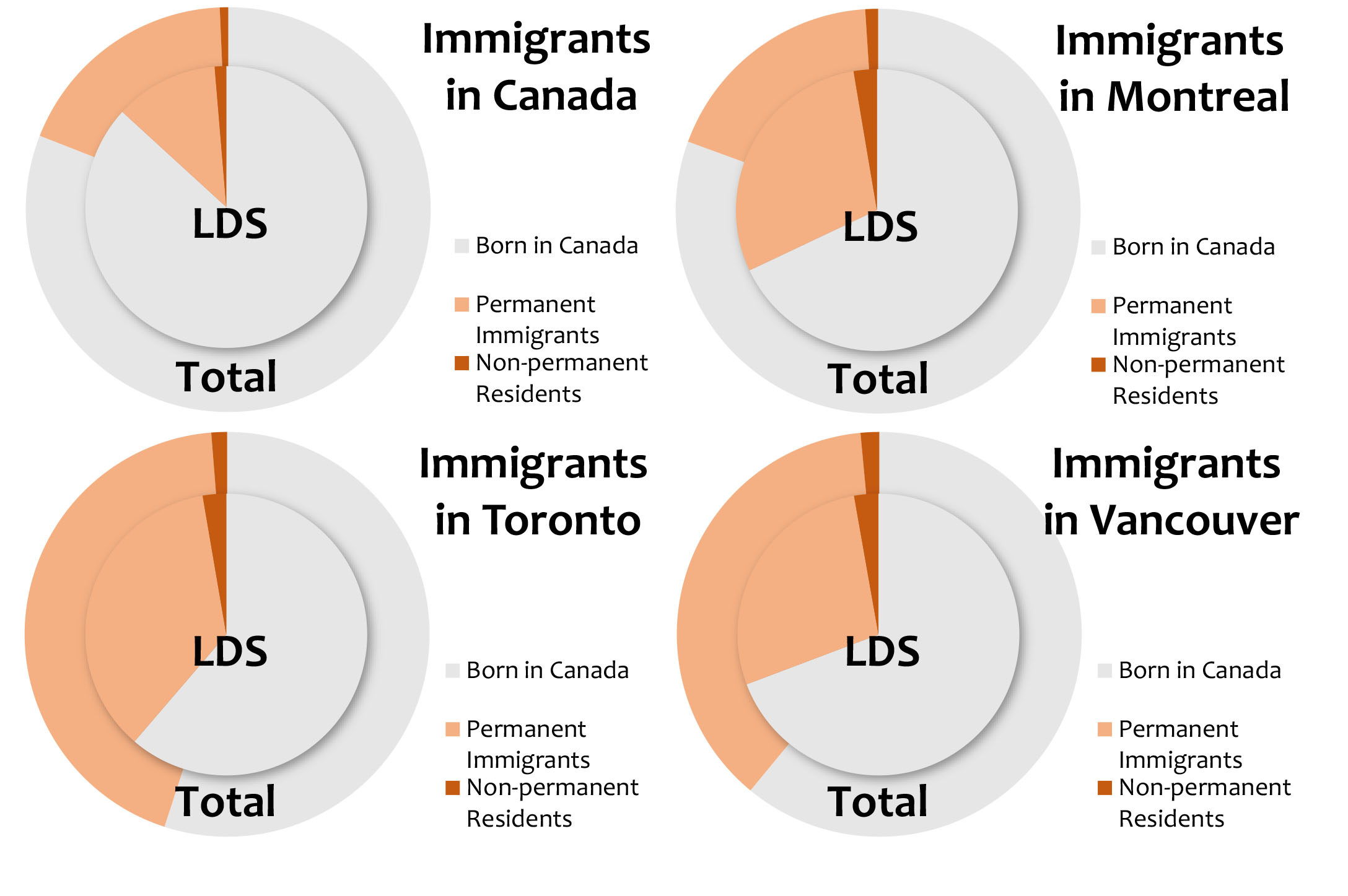

Canada has long relied on immigration to grow. Since the 1870s, the percent of foreign-born population in Canada has remained around 20 percent. Today Canada has the second-highest proportion of foreign-born population among high-income Western nations.[87] In several of these high-income nations, birth rates have decreased below rates of replacement, and immigration has been an important tool for maintaining a healthy economy and workforce.[88]

Immigration is not uniform across Canada, as provinces vary in their ability to attract immigrants. Historically, immigrants have been drawn to the largest cities in Ontario and British Columbia. Today the proportion of foreign-born population in Ontario and British Columbia is several times higher than other provinces.[89] To address this imbalance and to meet specific local economic needs in individual provinces, provinces have been allowed special considerations to attract more immigrants.[90]

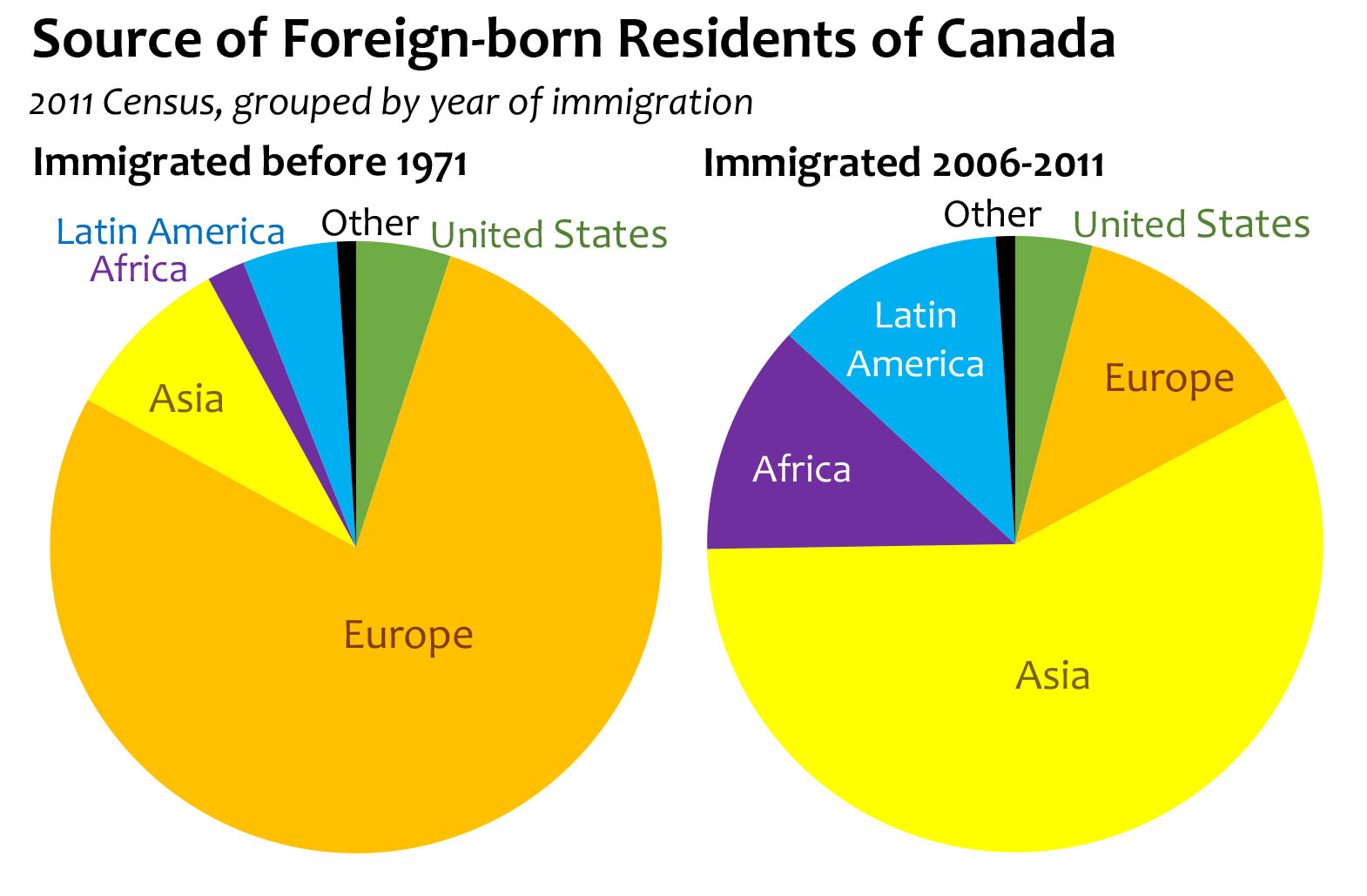

As Canada’s immigration policy has changed, the nations composing Canada’s foreign-born population have also changed. Early Canadian immigration favoured immigrants from northern and western Europe.[91] Immigration policies were enacted to limit, deter, or even bar immigration from different regions and countries. However, as a result of work shortages in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, immigrants from southern and eastern Europe and workers from China were “grudgingly admitted” to Canada to do cheap labour.[92] Through the 1950s, less traditional locations in Europe were scouted, and loans for passage to Canada were provided to fill labour needs across the country.[93]

In the 1960s, Canada’s immigration policy changed dramatically as the racially exclusionary policies of the past changed in favour of a points system based on education, work experience, and occupational needs in Canada.[94] This change in policy was designed to bring immigrants to Canada that could better meet long-term economic needs.[95] These “economic immigrants” were believed to have skills that could better withstand the fluctuations of economic change and were also viewed as less likely to become welfare dependent. As a result, immigration based on family connections (Family Class Immigrants) dropped from 50 percent of all immigrants with permanent residency in Canada in 1984 to only 25 percent of permanent residents in 2014.[96]

With an immigration policy especially favouring high-skilled economic immigrants, immigrants from Asia began to dramatically increase in numbers in Canada. This trend is reflected in the change in birthplace among immigrants to Canada over time. Before 1971, nearly 80 percent of immigrants to Canada were born in Europe. Between 1991–95, the top senders were all from Asian nations, comprising two to three times as many of the immigrants to Canada than any European nation. Between 2006 and 2011, fewer than 14 percent of immigrants were from Europe and the majority of immigrants (56.9 percent) were born in Asian countries.[97] By 2014, immigrants from China, India, and the Philippines made up the vast majority of permanent residents in Canada.[98]

Comparing the LDS population to the population of Canada as a whole, there were fewer immigrants who were LDS (13.6 percent) than immigrants among Canadians as a whole (20.6 percent). Because immigration to Canada has increasingly occurred as a result of particular skills for economic advantage, it is not surprising that immigration comes disproportionately to more prosperous areas. In English Canada, Toronto had the greatest number of immigrants, followed by Vancouver.

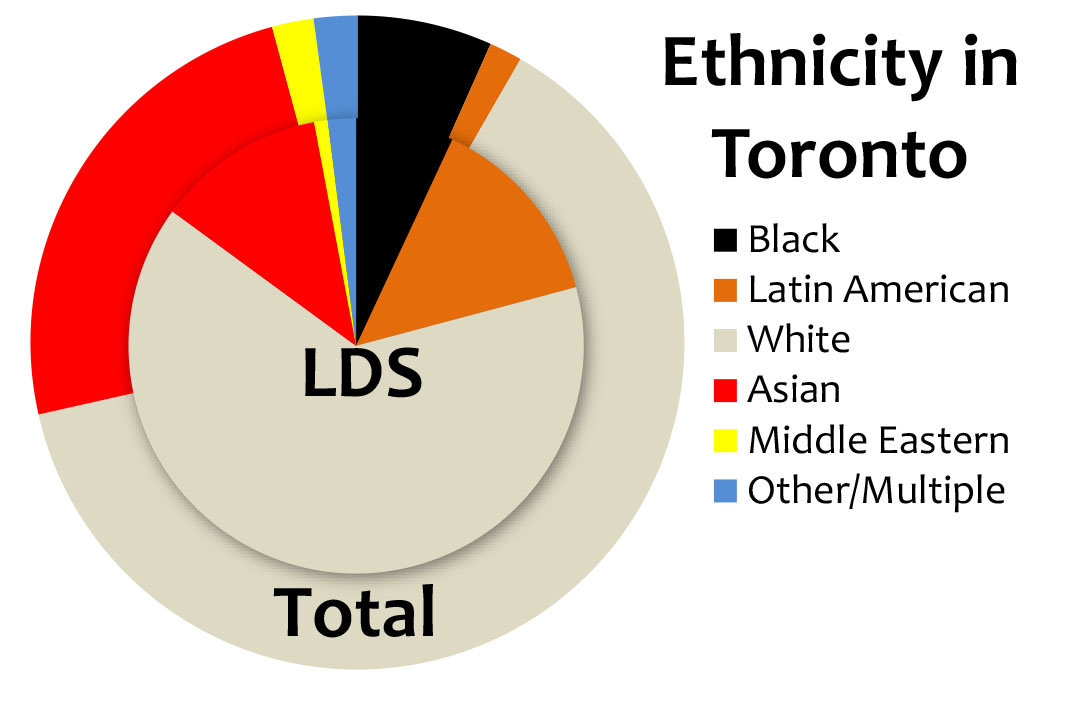

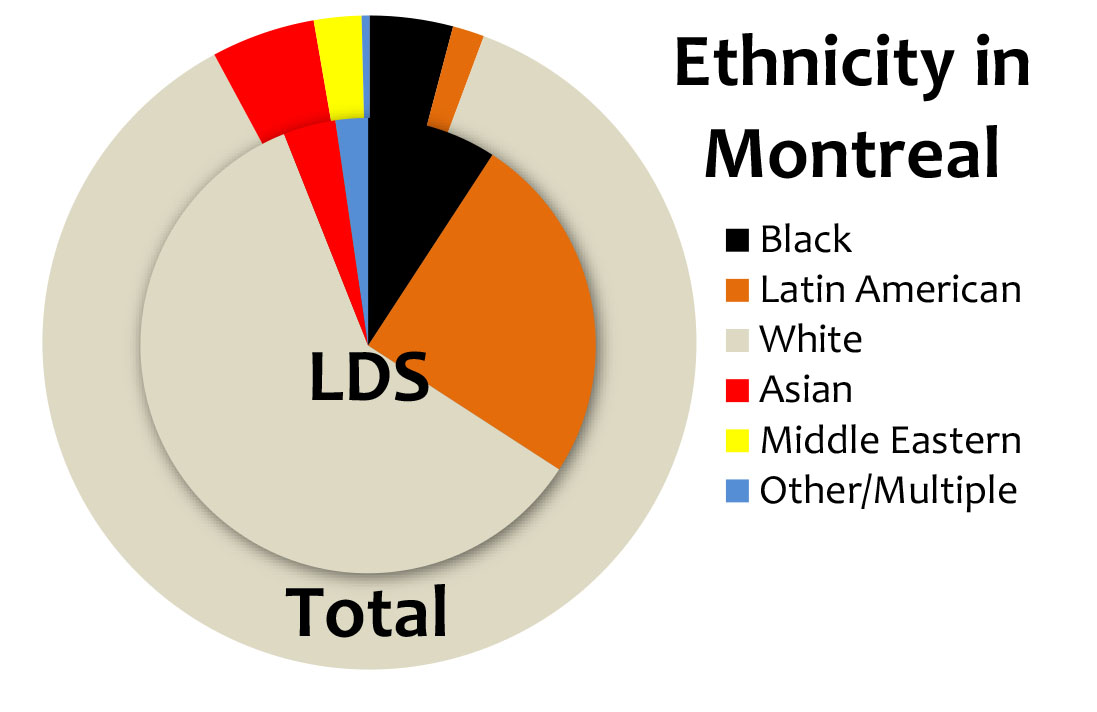

While the proportion of immigrants among Latter-day Saints was often less than the proportion of immigrants in the general population, the percent of immigrants in the Church was elevated in places such as Toronto, where there was a correspondingly larger proportion of immigrants in the total population. Nevertheless, the proportion of LDS immigrants was less than the proportion of immigrants in Toronto generally. The exception to this was in the province of Quebec and the city of Montreal in that province. In Quebec, the proportion of immigrants was lower than in other prosperous provinces, but the proportion of LDS immigrants was approximately twice as great as in Quebec as a whole. As indicated in the above figure, the proportion of Blacks in the LDS Church was about double that of the general population, whereas the proportion of Latin Americans was about 20 percent, compared with 2 percent in the population as a whole. In very recent years, new immigrants have been making up a larger proportion of converts to the Church, as missionary work reaches out to these communities.[99] If this continues, the proportion of immigrants in the Church will become noticeably larger, as will the proportion of visible minorities in the Church.

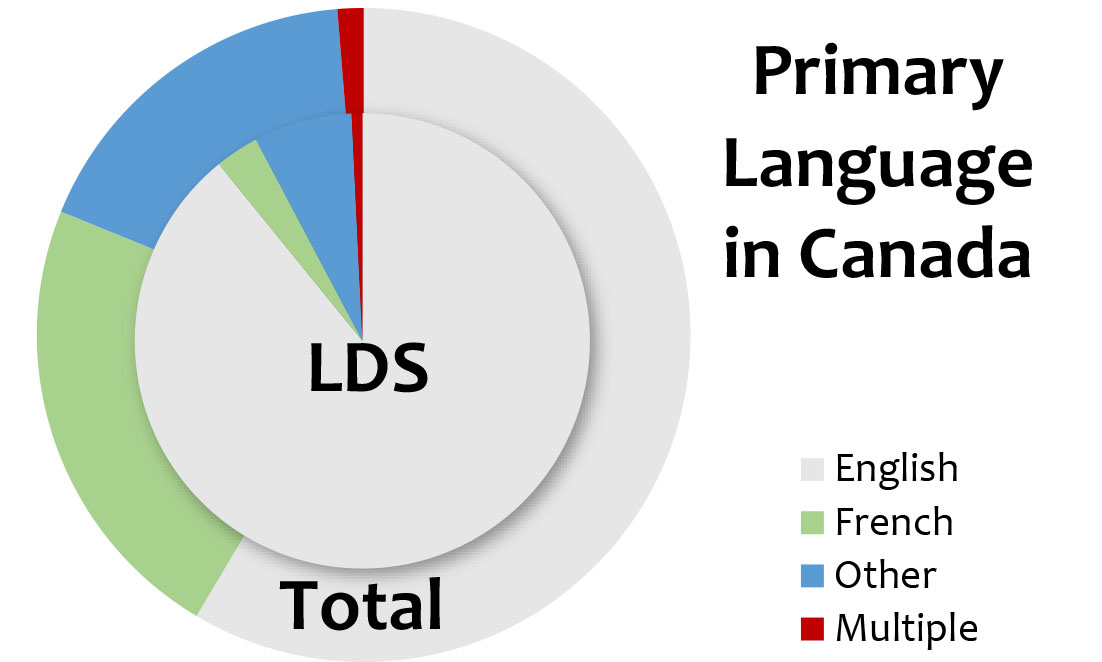

Primary Language

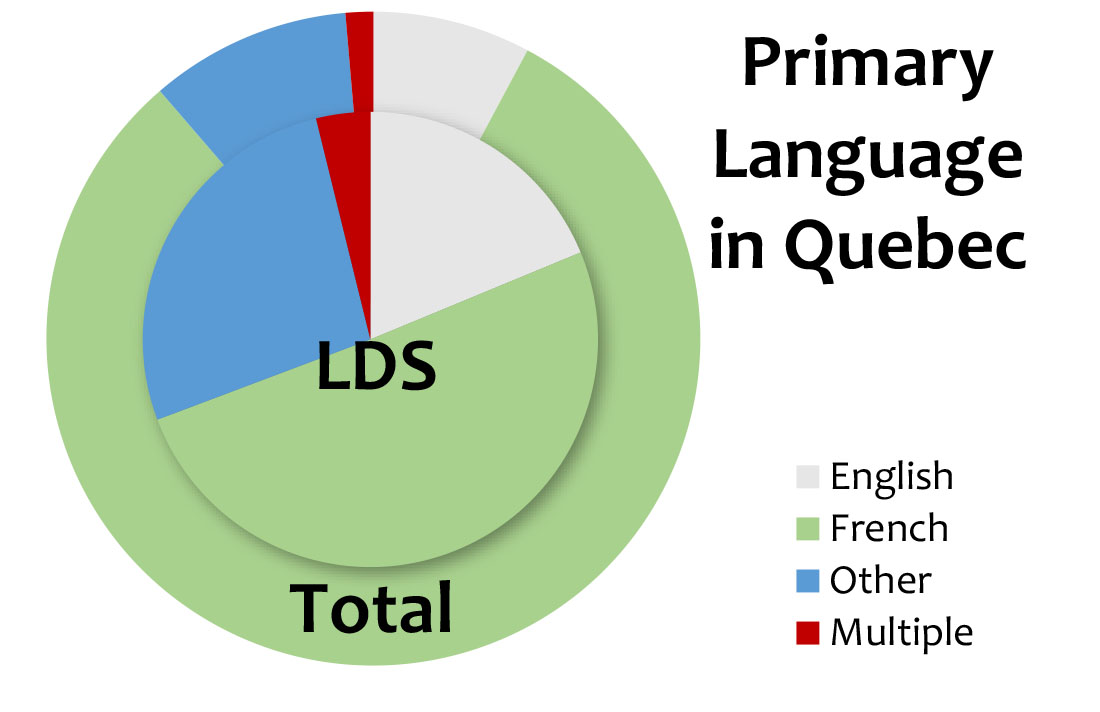

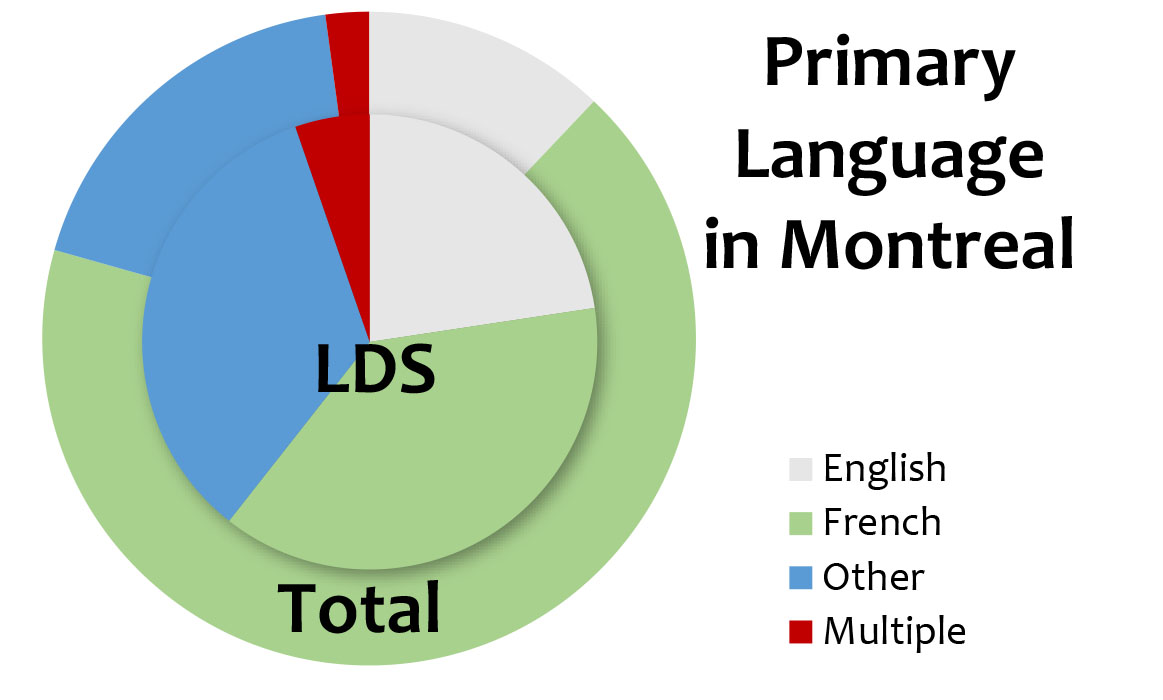

Latter-day Saints are different from Canadians as a whole in terms of primary language. The majority of Canadians speak the English language, but approximately 25 percent of Canadians, most of whom live in Quebec, claim French as their mother tongue. Among Latter-day Saints in Canada, by contrast, English was almost completely dominant, except in French-speaking units in Quebec and in other linguistic units. The dominance of English was related to the fact that many Mormons live in Alberta, Ontario, and western provinces where English predominates.

In Quebec the vast majority of the population uses French as their primary language. English and other languages make up a minority of speakers. The majority of LDS members in Quebec are also French speakers, but other-language and English speakers constitute a larger minority than in the Quebec population as a whole. This was a result of the early development of the Church solely in English until the early 1960s and of the fact that many converts in Quebec have come from immigrant populations.

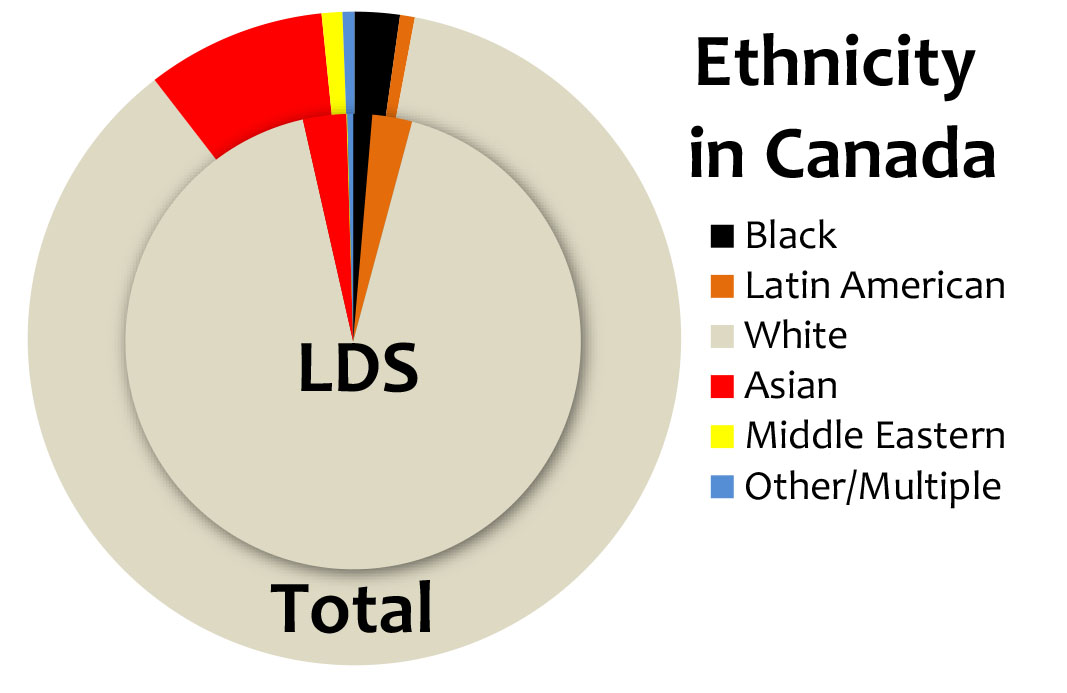

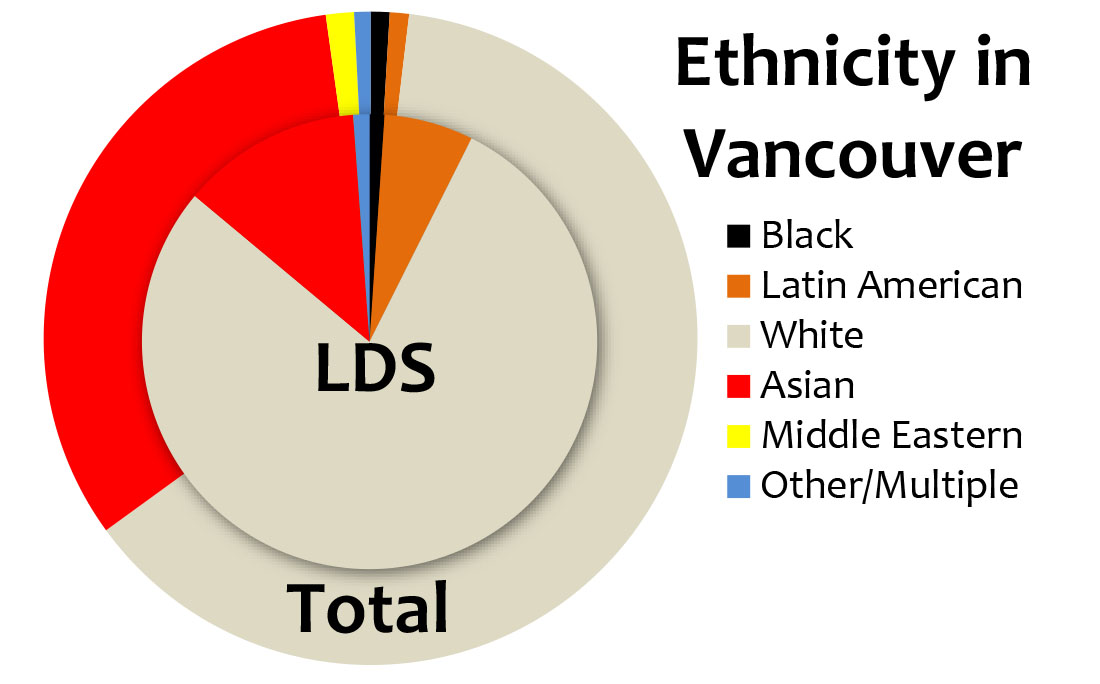

Ethnicity, Visible Minority Status

At present, there is no standard ethnic identity data by religion for the LDS population in Canada. However, data on visible minorities are presented here. The major visible minorities in Canada are Asian, Black, Latin American, and Middle Eastern. Aboriginal or First Nations are not included in these numbers. Increasingly, individuals are mixtures of multiple races but are still usually identified with one of the major categories. In the 2001 census, the last year’s questions about race and ethnicity were included; visible minorities totalled 13.4 percent of the Canadian population. Among Canadian visible minorities, 25.8 percent were Chinese, while 23 percent were South Asian. The third largest group was Black Canadians, with 16.6 percent. Since 2001, the visible minority population in Canada has continued to grow. Today nearly one in five Canadians (19.1 percent) is considered a visible minority.[100]

In 2001, the LDS population had far fewer visible minorities than the Canadian population (7.7 percent compared to 13.4 percent). The makeup of visible minorities among Latter-day Saints was different as well. The largest LDS visible minority was Latin Americans (36.7 percent of the LDS visible minority population). The second-largest group was Black Canadians (17.4 percent of visible LDS minorities) and the third largest group was Filipinos (14.7 percent of LDS visible minorities). Almost two-thirds of LDS visible minorities were from these three groups. The fourth largest group was Chinese (10.8 percent).

Hispanic culture was highlighted in colourful scenes in this 2007 cultural celebration for the general public sponsored by the three Vancouver stakes. (John McCulloch)

Hispanic culture was highlighted in colourful scenes in this 2007 cultural celebration for the general public sponsored by the three Vancouver stakes. (John McCulloch)

By 2001, according to Census Canada data, most cities in Canada followed the general pattern of fewer visible minorities among LDS membership than in the overall population. However, the makeup of the Church has begun to reflect the growing diversity in these larger Canadian cities. We can again see this trend most clearly in Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal. While the LDS population of visible minorities in Vancouver was not as large as in the city as a whole, there were more LDS visible minorities than in smaller cities in Canada. Thirteen percent of the LDS population in Vancouver were of Asian descent, and today almost a third were born abroad. Toronto also had a large proportion of visible minorities, and LDS minorities were a much higher proportion of the LDS population. There were still fewer visible minorities among Latter-day Saints than in Toronto as a whole, but the proportions were again closer than in smaller Canadian cities. Among LDS minorities in Toronto, Blacks and Latin Americans were a significant proportion of the membership, as were Asians. In Montreal, similar to the trend with the proportion of immigrants, the overall proportion of visible minorities in the LDS population actually exceeded that of the overall population. The clear majority of these Latin American, who comprised almost over 20 percent of the total Church membership in Metro Montreal.

The proportion of minorities of different backgrounds also varies across Canada. In the west of Canada, there were more Asians among visible minorities both outside the Church and within LDS membership. In the east, there were more Black Canadians both overall and among LDS members. The eastern minority population was more varied, with groups such as Middle Eastern represented. To a considerable extent, LDS minorities reflected the basic population of minorities in the cities where they are located. This explains the greater number of LDS Black Canadians in the east and Asians in the west and the greater variety in eastern congregations. The Latin American population was overrepresented compared to other minorities among Latter-day Saints and most likely reflects the large number of Latin Americans who have joined the Church before coming to Canada. Filipinos were one Asian population that showed this same pattern.

Creation of Ethnic Units

As in the United States, the Church has organized a number of “specialized congregations” that meet the linguistic and cultural needs of minority Church members from different ethnic backgrounds.[101] The first ethnic branch of the Church, a Hispanic branch called the Lehi Branch, was organized in Toronto in 1977. In 2015, there were nineteen such wards and branches across Canada, most of which are in Canada’s largest urban centres: Vancouver, Calgary, Toronto, and Montreal. Of these, ten are Spanish speaking, six Chinese (three Mandarin, one Cantonese, and two just designated Chinese), and one Korean.[102]

LDS language wards are established in areas with a sufficient concentration of members speaking a given language to make them viable. In many other cases, wards that are “English” or “French” (in Quebec) may contain members from many ethnic, linguistic, and cultural backgrounds because there are not sufficient numbers of each group to create a ward or branch. In these cases, accommodations, such as specialized classes, may be offered.

LDS language wards are established in areas with a sufficient concentration of members speaking a given language to make them viable. In many other cases, wards that are “English” or “French” (in Quebec) may contain members from many ethnic, linguistic, and cultural backgrounds because there are not sufficient numbers of each group to create a ward or branch. In these cases, accommodations, such as specialized classes, may be offered.

Conclusion

The Latter-day Saint Canadian experience is similar to the experience of Latter-day Saints in the United States in terms of ecclesiastical organization and general growth trends. This is because Church leaders, while seeing Canada as a different country, in light of the similarities and geographical proximity of the two countries, have administered Canada as an extension of the United States. As well, the organization of the Church has followed closely worldwide trends that have been influenced by policy changes in Salt Lake City, including the establishment of seminary and institute programs, the development of stakes in the 1960s, the increased emphasis on ministering to the Lamanites in the 1980s, and the building of smaller temples in the 1990s.

There are a number of factors that make the Latter-day Saint experience in Canada uniquely Canadian. Canada is very different from the United States in terms of weather, distance, regional fragmentation, government regulations, economics, bilingualism, and multiculturalism. These differences have led to larger wards, branches, and stakes; longer distances for Church members to travel to attend weekly church services, stake conferences, and temples; the increased use of telecommunication technologies to stay in touch with isolated Church members; the reduction of activities during winter months; the development of French-speaking stakes; an increasing number of ethnic wards in recent decades; and the movement of Church members to areas of economic prosperity.

Yet despite some of these challenges, the LDS Church in Canada has seen remarkable growth in the past century, particularly during the 1956 to 1990 time frame. Church growth has occurred when Church leaders have created mission and area boundaries that are entirely within Canada. Although since 2001, Church growth seems to have stabilized, there are presently 149 branches, 338 wards, three districts, forty-eight stakes, seven missions, and eight temples in Canada (with one to come),[103] all of which signify a maturation of Church membership throughout much of Canada. The widespread distribution of temples bodes well for the further growth of the Church in Canada and the creation of strong intergenerational families.

Appendix A: List of Stakes in Canada with Date of Organization as of 2016

|

Appendix B: Snapshots of Regional Administration (EA=Executive Administrator, RR=Regional Representative, SP=Stake President, AS= Area Seventy, CC=Coordinating Council)

| 1983 | 1994 | 2016 |

Canada British Columbia Area EA: Elder F. Enzio Busche (also over three areas in northwest United States) RR: David Owen Dance (of Seattle) Vancouver Region (four stakes) Two regions in Alaska Canada Alberta Area EA: Elder Loren C. Dunn (also over four areas in north-central United States) RR: Blaine Leon Hudson (former SP of Calgary North Stake) Calgary Region (four stakes) Edmonton Region (four stakes) RR: R. Donald Livingstone Cardston Region (three stakes) Lethbridge Region (three stakes) Canada Central Area EA: Elder Paul H. Dunn (also over three areas in Midwestern United States) RR: Fred Neel Spackman (former SP of Cardston Stake) Saskatoon Region (one stake) Winnipeg Region (one stake) Canada East Area EA: Elder Rex C. Reeve (also over four areas in northeast United States) RR: Elden C. Olsen (former SP of Hamilton Stake) Toronto Region (five stakes) Ottawa Region (one stake) Montreal Region (two stakes) No stakes in Atlantic Provinces | North America Northwest Area RR: Denzel N. Wiser (of Seattle) Vancouver Region (five stakes) One region in Washington North America Central Area RR: Ellis G. Stonehocker (former SP of Calgary South Stake) Calgary Region (five stakes) Edmonton Region (four stakes) Saskatoon Region (two stakes) RR: Donald Dahl Salmon (former SP of Edmonton Stake) Cardston Region (five stakes) Lethbridge Region (four stakes) North America Northeast Area RR: John Bruce Smith (former SP of Toronto Stake) Toronto Region (seven stakes) RR: C. Malcolm Warner (former SP of Brampton Stake) Montreal-Ottawa Region (three stakes) Dartmouth Region (two stakes) Cumorah NY Region (five stakes) | North America Northwest Area AS: Elder Michael R. Murray (of Seattle) Canada Vancouver Area CC (seven stakes) Two CCs in the United States North America Central Area AS: Elder G. Lawrence Spackman (former SP of Calgary Stake) Canada Calgary Area CC (seven stakes) Canada Edmonton Area CC (six stakes) Canada Winnipeg Area CC (three stakes, one district) AS: Elder James E. Evanson (former SP of Lethbridge East Stake) Canada Lethbridge Area CC (eleven stakes) Two CCs in the United States North America Northeast Area AS: Alain Allard (former SP of Montreal Stake) Canada Toronto Area CC (eight stakes, one district) Canada Montreal Area CC (four stakes) Canada Halifax Area CC (three stakes, three branches) |