Carma T. Prete, “Eastern Canada: An Early Fruitful Field, 1829-77,” in Canadian Mormons: History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Canada, ed. Roy A. and Carma T. Prete (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 22-53.

Carma T. Prete received her BA in history at Brigham Young University in 1968. Since then, she has engaged in researching, writing, and editing materials on Latter-day Saint history in eastern Ontario. She was an associate editor of Zion Shall Come Forth: A History of the Ottawa Ontario Stake (1995), for which she researched and wrote three chapters. She is the author of “We Do Not Doubt Our Mothers Knew It”: Latter-day Saint Pioneers in the Shannon View Saskatchewan Area, 1905–1969 (2016). As a Church history missionary in Salt Lake City, Utah (2013–16), she did extensive research on the history of the LDS Church in Canada. She has served in numerous Church callings: Primary president (four times), Relief Society president (twice), and district director of public affairs. She is the mother of six children and grandmother of twenty-four grandchildren. (See photo at beginning of chapter 1.)

Eastern Canada was an early fruitful field for the preaching of Mormonism. Between 1832 and 1853, as many as 2,500 people joined the Church, and numerous small branches were established. But by 1855, responding to the call to gather to Zion, most of these converts had left Canada to join the main body of the Church in Utah.

Eastern Canada was an early fruitful field for the preaching of Mormonism. Between 1832 and 1853, as many as 2,500 people joined the Church, and numerous small branches were established. But by 1855, responding to the call to gather to Zion, most of these converts had left Canada to join the main body of the Church in Utah.

The British North American colonies, which formed the Dominion of Canada after 1867, played a significant role in the early history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Because of the close proximity of Upper Canada (now Ontario) to the birthplace of the new religion in upstate New York, Canada was the first country outside the United States to receive the restored gospel. In 1832, just two years after the organization of the Church, missionaries arrived in Kingston, Upper Canada, to boldly proclaim that God had restored his Church upon the earth through a latter-day prophet and that they had a book of modern scripture, the Book of Mormon, in addition to the Bible. During the 1830s and 1840s, missionaries took this message to various areas in Upper Canada, to English-speaking regions of Lower Canada (now Quebec), and to the Maritime colonies.

Eastern Canada was a fruitful field, especially Upper Canada, where many people were prepared to accept the message of the Restoration. Through the efforts of Brigham Young, Parley P. Pratt, John E. Page, and other zealous missionaries, who travelled “without purse or scrip,” an estimated 2,500 Canadians joined the Church by the early 1850s. Most of these converts, however, departed from Canada soon after their conversions, gathering with the main body of Saints in Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois and eventually going west to settle in the Rocky Mountains in the United States. Although the nineteenth-century presence of the Church in eastern Canada was short lived, the lasting influence of early Canadian converts on the Church as a whole was immense, not only in terms of numbers but also leadership.

British North America in the Early Nineteenth Century

When the thirteen colonies, as a result of the Revolutionary War, won their independence from Great Britain and established the United States of America in 1783, the British still held vast territory to the north, known as British North America. Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island had been settled largely by English and Scottish colonists, while the population in Lower Canada was dominantly French speaking. Following the American Revolution, an estimated forty to fifty thousand United Empire Loyalists from the United States found refuge in Canada, the vast majority settling in what would become the Maritime provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, while others settled in what would become the provinces of Ontario and Quebec.[1] To accommodate the new arrivals, New Brunswick was established as a separate colony in 1784, and under the Constitutional Act of 1791, the Canadas were divided into Upper Canada and Lower Canada. These colonies, which remained under the British crown, had a measure of self-government and enjoyed religious toleration. Each colony had a governor or lieutenant governor who had an appointed council with an elected assembly, which had authority to approve taxes. Foreign relations remained under the control of the British government.[2]

The Loyalists set the tone of anti-American sentiment, and a certain antipathy to Great Britain reigned in the newly formed United States. Following the Loyalists, other immigrants came from England, Scotland, and Ireland, seeking land and better economic opportunities. Prior to War of 1812, these immigrants were joined in Upper Canada by numerous “Late Loyalists,” Americans of doubtful loyalty to the Crown, attracted mainly by the availability of cheap land. The border, however, was essentially open for the free passage of people, although heavy tariffs acted as a brake to commercial interaction. By 1831, the population of British North America had surpassed one million.[3]

Several factors helped prepare people in Canada for the advent of new religious ideas. A largely rural and agricultural society, British North America, especially Upper Canada, was just emerging from the frontier stage of its development. Early settlers—having established farms, villages, and businesses—were now able to turn their attention from mere survival to political and religious matters. Social, economic, and political conditions were unsettled, making people more receptive to new ideas.[4] Roman Catholicism was the overwhelmingly dominant religion in Lower Canada, which had been settled by Catholics from France during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The Catholic clergy were firmly established in Lower Canada, making it an inhospitable place for preaching a new religion. The Loyalists and later settlers in the rest of British North America in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were predominantly Protestant. The Anglican Church had been given official status and significant land grants, the so-called “clergy reserves” that were set aside for its financial support, providing for clergymen and the construction of Anglican churches in the more populous areas. But inadequate provision was made to extend the Anglican ministry to the many and scattered settlers in rural and remote areas, who lived under pioneer conditions, far from cities and without religious ministrations. Methodist circuit riders from the United States and later from Britain stepped into the void, travelling and preaching to the unchurched settlers throughout the rural areas, resulting in Methodism becoming a large and significant religion among English-speaking Canadians. Methodist preachers generated a great excitement about religion as they travelled from community to community. Presbyterians, Mennonites, and Baptists also claimed adherents in the Canadas.[5] The religious pluralism and competition awakened people to the quest for religious truth.

Roads were few and of poor quality in much of British North America in the early 1800s, making waterways a particularly important mode of transportation. The lower Great Lakes, Lake Erie and Lake Ontario, flowing into the Saint Lawrence River, were the heart of the interior waterways system in that period. Other lakes and rivers also formed part of a waterways network. By 1830 steamships carrying passengers and freight regularly plied these various waterways. Built primarily for military purposes, the Rideau Canal was completed in Upper Canada in 1832, connecting a series of rivers and lakes by canals and locks, stretching from Kingston to Bytown (Ottawa), on the Ottawa River. The Rideau Canal provided an alternate safe route from the Great Lakes to Montreal. The canal was also used for passenger transportation and commerce.[6] Early Mormon missionaries found these water highways a useful means of transportation to their fields of labour.[7]

The Atlantic Ocean, of course, was the great connecting link between the British North American colonies, the United Kingdom, the European continent, and the Eastern US Seaboard. Interestingly, early missionaries and migrants from Atlantic Canada to the centres of Mormonism made only occasional use of this thoroughfare, travelling mostly overland across the border to and from the United States.

The Origins of Mormonism and its Introduction to Upper Canada

Joseph Smith and the Restoration

As part of the religious revivalism sweeping the area, a great deal of religious excitement prevailed in the spring of 1820 in Palmyra, New York, just across Lake Ontario from Upper Canada. Methodists, Presbyterians, and other denominations competed for converts among the local settlers, who, just as in Upper Canada, were emerging from the pioneer stage of their development. Confused by this “war of words” and “contest of opinions,” fourteen-year-old Joseph Smith went into a grove of trees to pray about which of all the existing churches was right. In response to Joseph Smith’s fervent petition, God the Father and his Son, Jesus Christ, appeared to him, instructing him to join none of the churches. An angel visited Smith in 1823, telling him of a sacred record engraved on gold plates buried in a nearby hillside that contained “an account of the former inhabitants of the [American] continent” and “the fulness of the everlasting Gospel . . . as delivered by the Savior” to them. Smith obtained the plates in 1827, and by 1830 he had translated and published the record, known as the Book of Mormon. Priesthood authority was restored to Smith in 1829 by heavenly messengers, and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was organized in April 1830.[8] Early Church members were eager to share their witness that the primitive church of Jesus Christ had been restored to the earth through a modern-day prophet, complete with a new volume of scripture. Their missionary zeal resulted in the rapid spread of the gospel message to adjacent areas.[9] Not surprisingly, emissaries of the new religion soon found their way into nearby areas of Canada.

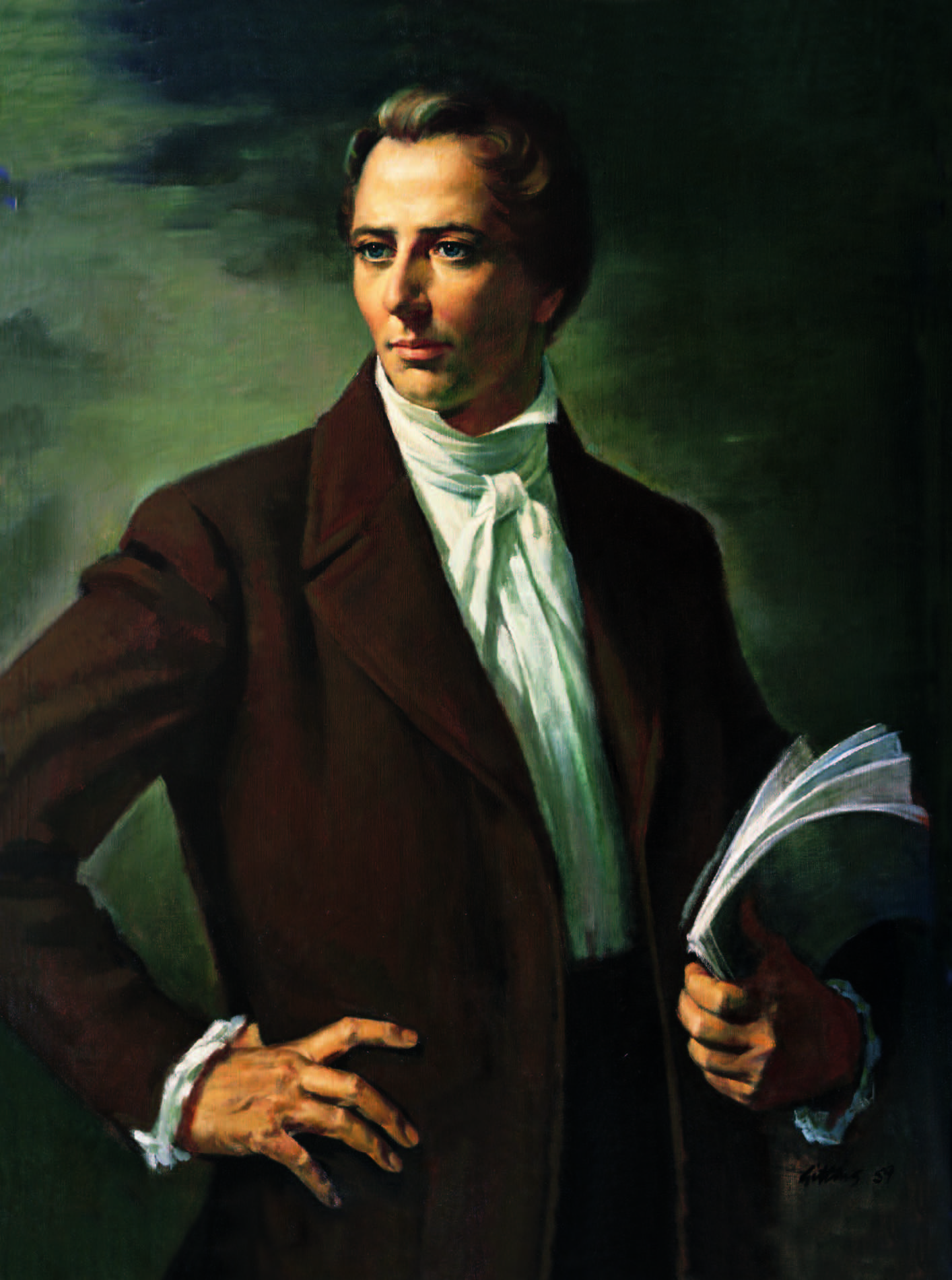

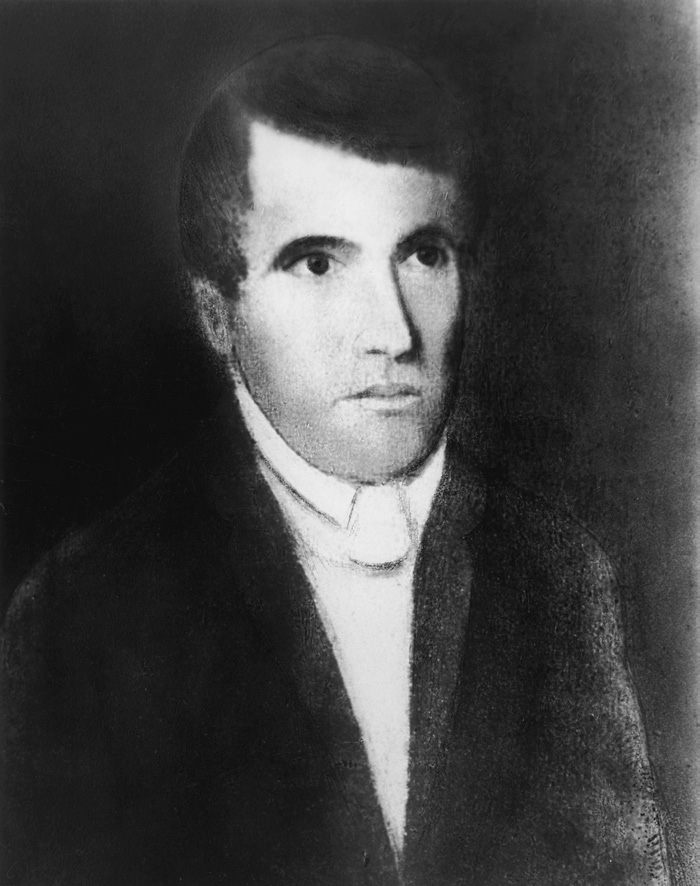

Joseph Smith, revered by Latter-day Saints as a prophet of God. In the spring of 1820, fourteen-year-old Joseph Smith went into a grove of trees near Palmyra, New York, to seek religious truth. In answer to his fervent prayer, he received a glorious vision of God the Father and Jesus Christ. From this experience and subsequent spiritual manifestations arose a dynamic new religion, claiming a restoration from heaven of New Testament Christianity. (IRI)

Joseph Smith, revered by Latter-day Saints as a prophet of God. In the spring of 1820, fourteen-year-old Joseph Smith went into a grove of trees near Palmyra, New York, to seek religious truth. In answer to his fervent prayer, he received a glorious vision of God the Father and Jesus Christ. From this experience and subsequent spiritual manifestations arose a dynamic new religion, claiming a restoration from heaven of New Testament Christianity. (IRI)

Sporadic Early Preaching

The earliest efforts to introduce the restored gospel to Canada were sporadic and unplanned. The first known person to preach of Mormonism in Canada was Solomon Chamberlin, who lived in Lyons, New York. He had long searched for religious truth and had received assurances from God that, within his lifetime, God would establish his true religion with the power and authority of Christ’s original church. In 1829, prior to the publication of the Book of Mormon and the organization of the Church, Chamberlin was on his way to visit friends in Upper Canada when he felt inspired to stop in Palmyra. There, Joseph Smith’s brother Hyrum told him of the Restoration and accompanied him to the Grandin Print Shop in Palmyra, where Chamberlin obtained the first sixty-four printed pages of the Book of Mormon. Chamberlin then continued on his journey. His account does not contain details of his visit to Upper Canada, except that he travelled a total of seven hundred to eight hundred miles, sharing “all that [he] knew concerning Mormonism” with “all both high and low, rich and poor.”[10] No one he encountered during his journey had ever heard of the so-called “Gold Bible.” He noted that “this was the first that ever printed Mormonism was preached to this generation.”[11] Chamberlin was baptized in April 1830.[12]

In early 1830, Joseph Smith received a revelation directing Oliver Cowdery, Hiram Page, Josiah Stowell, and Joseph Knight to go to Kingston, Upper Canada, to sell a copyright of the Book of Mormon for the “four Provinces.”[13] Although there is no date on the revelation, recent scholarship has determined that it was given between mid-January and early March 1830, during a period when funds were sorely needed to proceed with the publication of the Book of Mormon in Palmyra.[14]

Cowdery and Page, and probably Stowell and Knight as well, then travelled to Canada. Details of their journey are scarce and often contradictory. Two accounts refer to the men going to Toronto (York) instead of, or in addition to, Kingston.[15] There were at least three major publishers in Kingston at that time with whom the men might have discussed selling the rights to publish the Book of Mormon in Canada, but there were also active publishing houses in Toronto, which was at that time smaller than Kingston.[16] In any case, the men did not find a willing buyer for the publication rights for the Book of Mormon,[17] but they undoubtedly shared aspects of the story of the Restoration in their attempt to do so.

In August 1830, Joseph Smith Sr., father of the Prophet Joseph Smith, accompanied by his son Don Carlos, travelled from Palmyra to St. Lawrence County, New York, to share the gospel with his father, brothers, and sisters. Travelling by boat along the Saint Lawrence River, Smith reported stopping at “several of the Canadian ports” and distributing “a few copies of the Book of Mormon.”[18]

Phineas Young Bears the First Recorded Testimony in Canada

In April 1830, soon after the organization of the Church, Phineas Young purchased a copy of the Book of Mormon from Samuel Smith, brother of Joseph Smith and the first official missionary for the Church. Phineas, a Methodist preacher living near Mendon, New York, thought the book must be a fraud or a deception and obtained the book for the sole purpose of reading it to expose its errors. However, as he read the book from cover to cover twice during the next two weeks, he found no doctrinal errors, but instead he became convinced that the book was the word of God.[19]

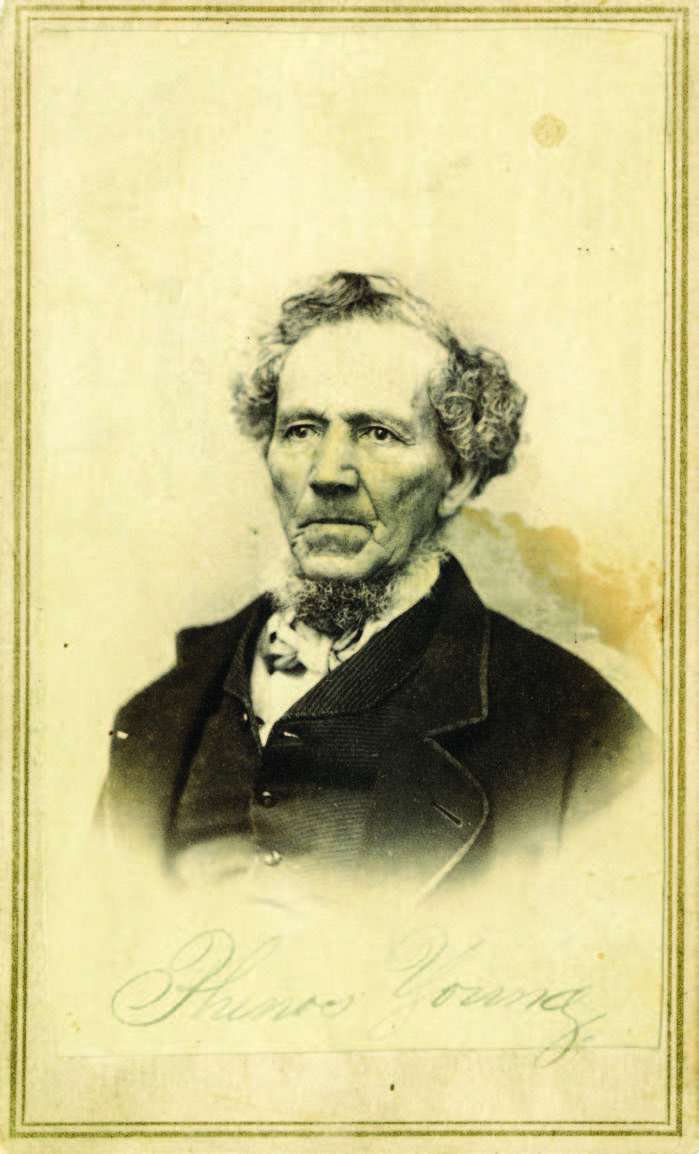

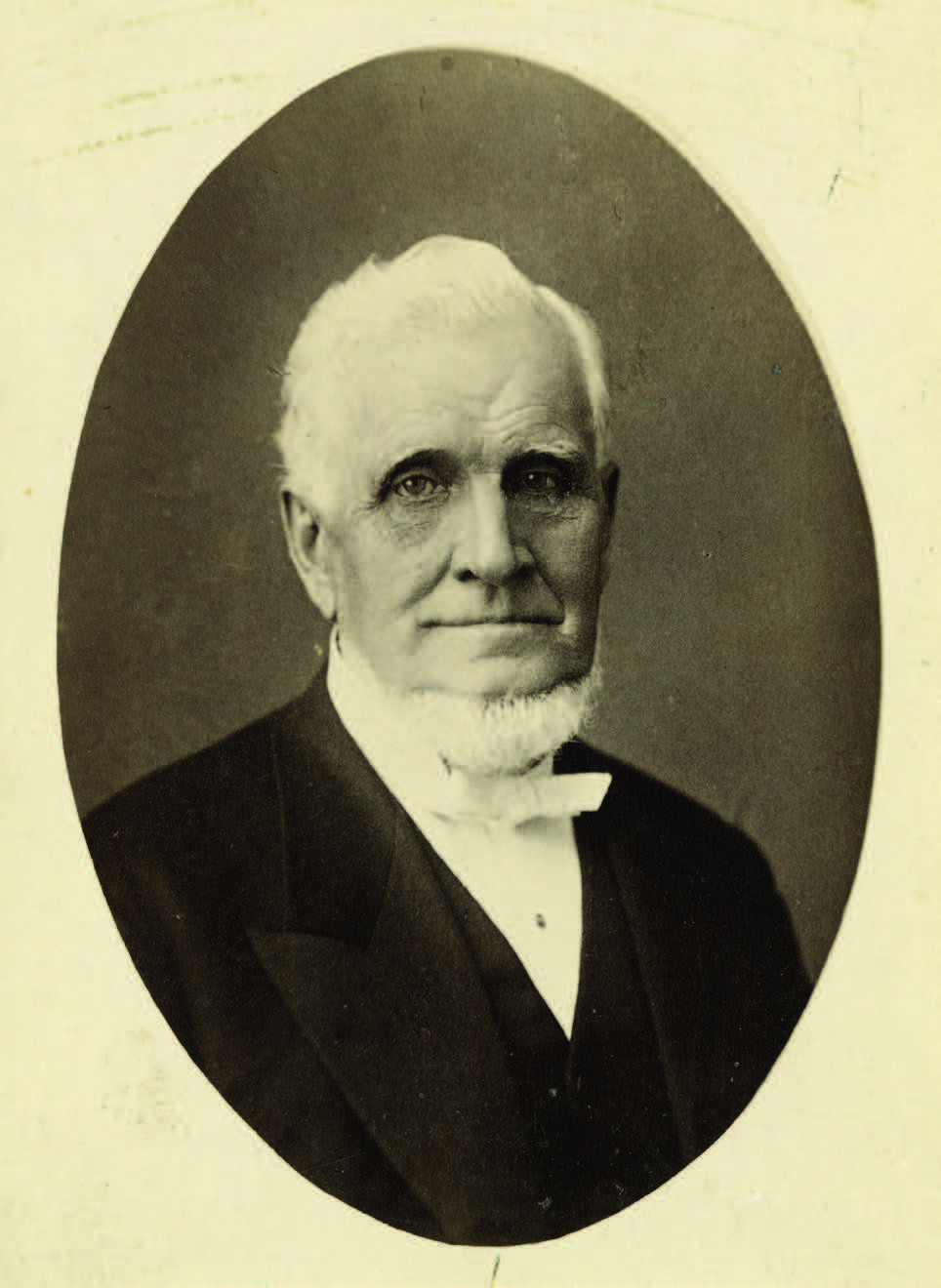

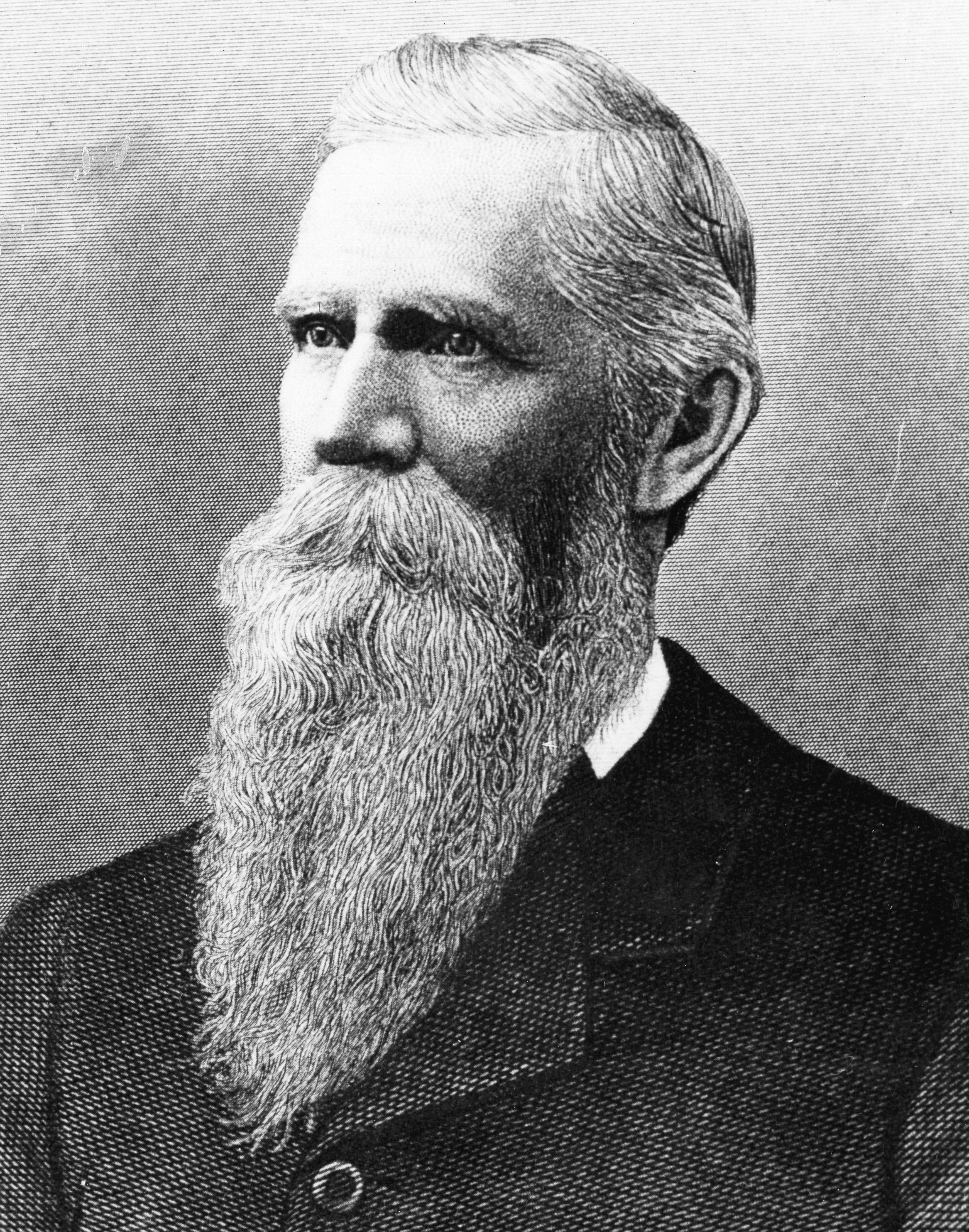

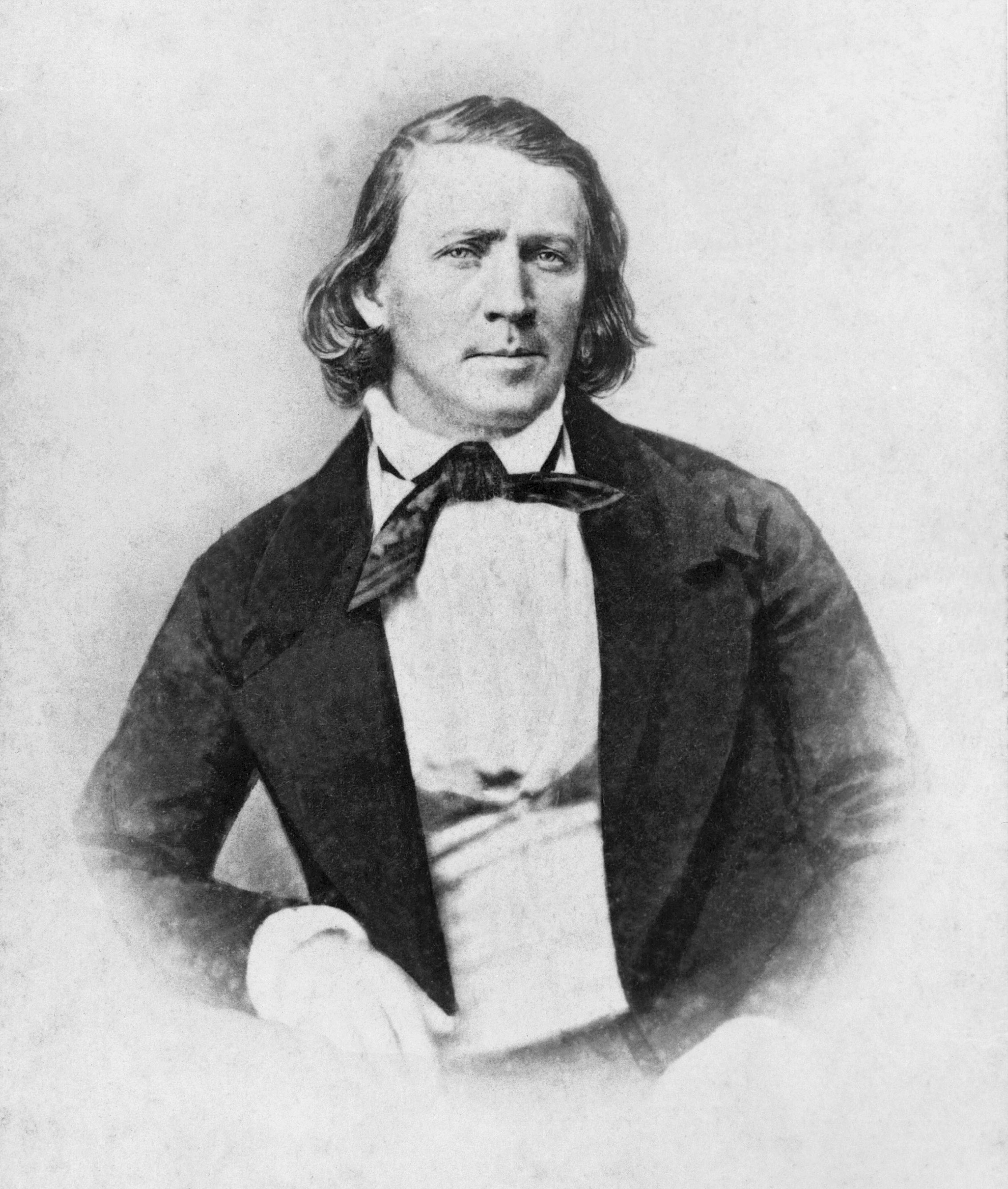

Phineas Young, an itinerant Methodist preacher, bore the first recorded testimony of the Book of Mormon outside the United States to a group of Methodist ministers in Kingston, Upper Canada, in 1830. (Church History Library)

Phineas Young, an itinerant Methodist preacher, bore the first recorded testimony of the Book of Mormon outside the United States to a group of Methodist ministers in Kingston, Upper Canada, in 1830. (Church History Library)

In August 1830, Joseph Young, a Methodist preacher labouring in Upper Canada, visited his brother Phineas east of Mendon, New York. Joseph invited Phineas to accompany him back to Canada to preach there. The two brothers departed for Canada on about 20 August, stopping in Lyons, New York, to visit an acquaintance, Solomon Chamberlin. While they were there, Chamberlin preached with zeal about the Book of Mormon and the church which had recently been organized.[20] After the Youngs left Chamberlin’s home, Phineas continued to ponder on what Chamberlin had said. He had not previously heard of the restoration of the priesthood or of the organization of the Church, and these ideas weighed powerfully on his mind.[21]

Joseph and Phineas Young journeyed on to Kingston, Upper Canada, and preached for a time in the Ernestown and Loughborough areas, west and north of Kingston. Although Joseph’s ministry proceeded well, Phineas found that he could not put his heart into preaching Methodism because his mind was so much focused on the Book of Mormon. He decided to return home.[22]

On his way, Phineas stopped in Kingston to attend the quarterly meeting of the Episcopal Methodists held at the conclusion of their annual conference. A First Nations man, speaking at the evening service, told of the traditions of his ancestors, and much of what he said corresponded with what Phineas had learned of the Lamanite people in the Book of Mormon. When Phineas returned to his hotel, he found that most of the participants of the conference were seated in two large rooms. He placed himself in the doorway between the two rooms and took the opportunity to address the assembly, numbering more than one hundred. He inquired if anyone present was familiar with the Book of Mormon, sometimes referred to as the “Golden Bible.” This statement caught the attention of the group, and he was invited to give a fuller account. Phineas related, “I commenced by telling them that it was a revelation from God, translated from the Reformed Egyptian language by Joseph Smith, jun., by the gift and power of God, and gave a full account of the aborigines of our country and agreed with many of their traditions, of which we have been hearing this evening, and that it was destined to overthrow all false religions and finally to bring in the peaceful reign of the Messiah.”[23]

He continued, “I had forgotten everything but my subject, until I had talked a long time and told many things I had never thought of before. I bore a powerful testimony to the work, and thus closed my remarks and went to bed, not to sleep, but to ponder with astonishment at what I had said, and to wonder with amazement at the power that seemed to compel me thus to speak.”[24]

Conversion of Brigham and Joseph Young

Brigham Young, a brother of Phineas and Joseph Young, was introduced to the Book of Mormon in 1830 and continued to study the gospel in the months that followed. In January 1832, Brigham and Phineas Young, accompanied by Heber C. Kimball, travelled to Columbia, Pennsylvania, to visit a branch of the Church and further investigate the new religion. They remained in Pennsylvania for one week, during which time they became increasingly convinced of the truthfulness of the restored gospel.[25]

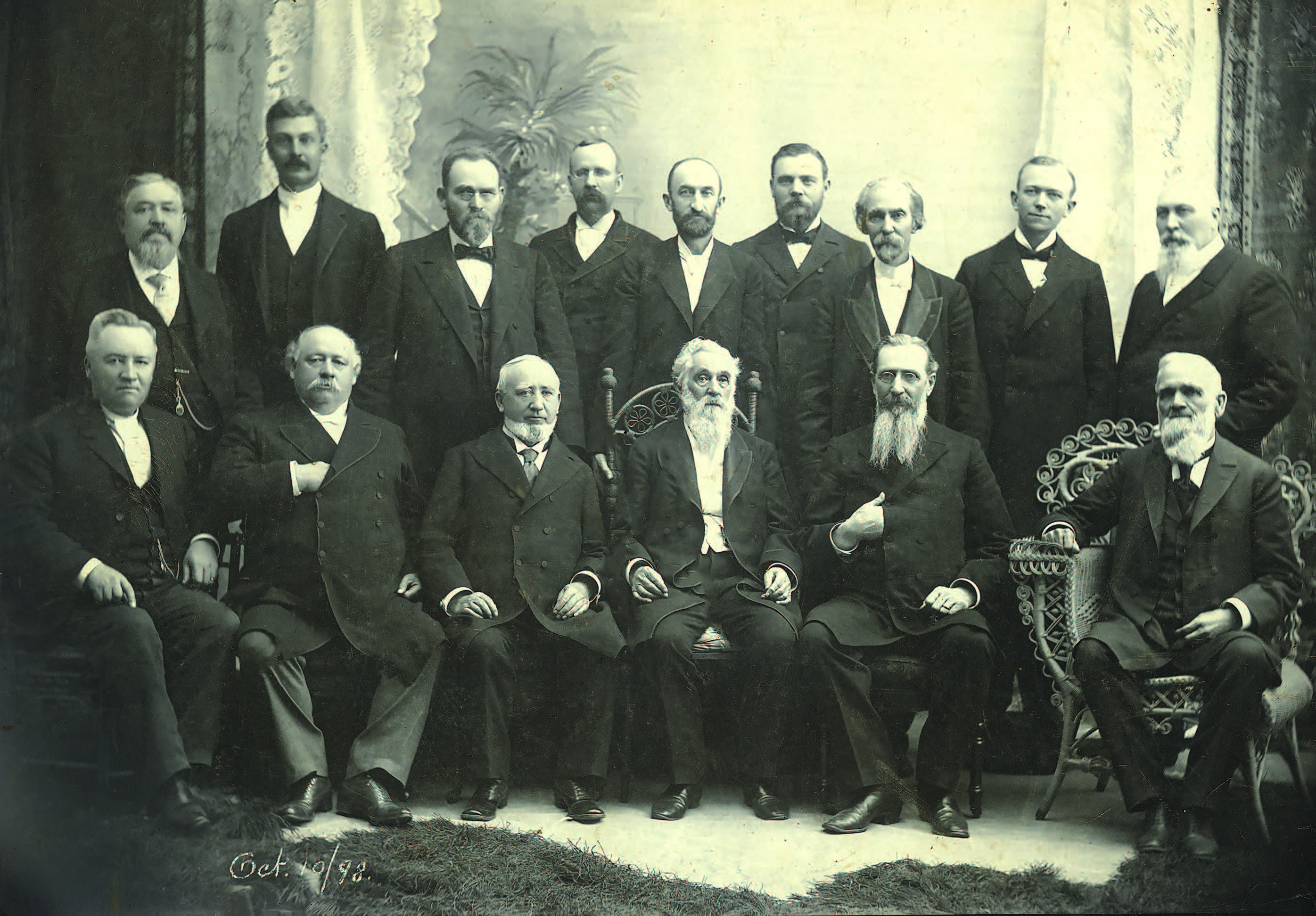

Brigham Young and his four brothers. Left to right: Lorenzo, Brigham, Phineas, Joseph, and John. Three of the Young brothers—Phineas, Joseph, and Brigham—were among the first to preach of the restored gospel in Canada. (Church History Library)

Brigham Young and his four brothers. Left to right: Lorenzo, Brigham, Phineas, Joseph, and John. Three of the Young brothers—Phineas, Joseph, and Brigham—were among the first to preach of the restored gospel in Canada. (Church History Library)

Brigham Young had a burning desire to share his newly acquired knowledge with his brother Joseph, who was still labouring as a Methodist preacher in Upper Canada, near Kingston. Immediately after returning from Pennsylvania to his home in Mendon, Young departed in a horse-drawn sleigh for Canada. Brigham Young, though not yet a baptized member of the Church, was a successful missionary. According to his account, “After finding my brother Joseph, and explaining to him what I had learned of the Gospel in its purity, his heart rejoiced, and he returned home with me, where we arrived in March.”[26] Brigham, Phineas, Joseph, and their father, John Young, were baptized in April 1832.[27] All of the Youngs remained faithful to the Church. An energetic and effective missionary, Brigham Young made four proselytizing trips to the Kingston area between 1832 and 1835 and went on to become President of the Church after Joseph Smith was martyred in 1844.

Early Preaching in the Kingston Area, 1832–33

In June 1832, six missionaries were sent to Upper Canada, the first ordained missionaries to labour outside the United States. The six men—four of whom came from Rutland, Pennsylvania, and two from Mendon, New York—were Joseph Young, Phineas Young, Eleazer Miller, Elial Strong, Enos Curtis, and one other as yet unidentified.[28] Phineas Young reported that they laboured in the Ernestown Township area for approximately six weeks, during which time they had great success and organized “the first branch in British America.”[29] Strong and Miller described “thousands” of people who “flocked” to their meetings, causing them to hold their services out of doors because houses were too small to accommodate the multitudes, and Strong said that he personally had baptized five people in the Ernestown area.[30] No baptismal numbers were given for the other missionaries. Among those who were baptized by these first missionaries were James and Philomela Lake and at least some of their older children.[31] Joseph Young, labouring among the people he knew so well from his previous Methodist preaching in the area, remained in the Ernestown area for two or three months after the other missionaries departed from Canada, organizing a second branch.[32]

Missionary work in the early days of the Church was quite different from more recent times. Missionaries went out without “purse or scrip” and relied upon the generosity and hospitality of the local people for their maintenance. They tended to preach in public facilities, churches, schools, or even barns, as these could be arranged. Their preaching and ministering were often accompanied by gifts of the Spirit, “good liberty” in their preaching (as Brigham Young described it),[33] healing others, and sometimes speaking in tongues. People were baptized as soon as they expressed the desire to be baptized. Although some missionaries in the early days of the Church received specific callings from Church leaders, others went out preaching on their own initiative, some immediately following their baptism and ordination to the priesthood. That the first group of six missionaries to Canada came from different locations and gave a report—which was published in the Evening and Morning Star, a Church publication—would suggest that they may have received a call for their assignment. In this “era of the freelance missionary,” others apparently went out on their own initiative to locations and for durations of their own choosing, However, the first missionaries to Canada were empowered, as part of their ordination as elders, to preach the gospel (see D&C 36:5; 50:10, 13–14) and apparently had authority to organize branches as occasion required.[34]

In early January 1833, Brigham Young and his brother Joseph departed on a mission to Upper Canada.[35] Even though Brigham’s wife, Miriam, had died the previous September, leaving him with two young daughters, he left them in the care of relatives to share his message. Brigham and Joseph Young travelled on foot “most of the way through snow and mud from one to two feet deep.”[36] Reaching the eastern end of Lake Ontario, they found that the channel had frozen over the previous night, allowing them to cross on the ice. However, the ice was very thin, so they proceeded with care. In Brigham Young’s words, the ice “bent under our feet, so that in places the water was half shoe deep, and we had to separate from each other, the ice not being capable of holding us.”[37] They continued six miles on the ice before arriving at Kingston, a remarkable example of having “faith in every footstep.” From Kingston they proceeded to the Loughborough Township area, a few miles north of Kingston, where they preached for approximately one month, baptizing forty-five people, and organized “the West Loboro and other Branches.”[38] One of those baptized by Brigham Young during this period was Artemus Millet, an experienced stonemason and construction foreman who later used his skills to great benefit in the construction of the Kirtland Temple.[39] Another pair of converts, Daniel Wood and his wife, Mary, became the great-grandparents of Henry D. Moyle of the First Presidency.[40] In February 1833, the two Young brothers departed for home, crossing the ice from Kingston to New York State just before the ice broke up.[41] During their two-month mission, they travelled between five and six hundred miles, returning to their home in Mendon, New York, by 1 March.[42]

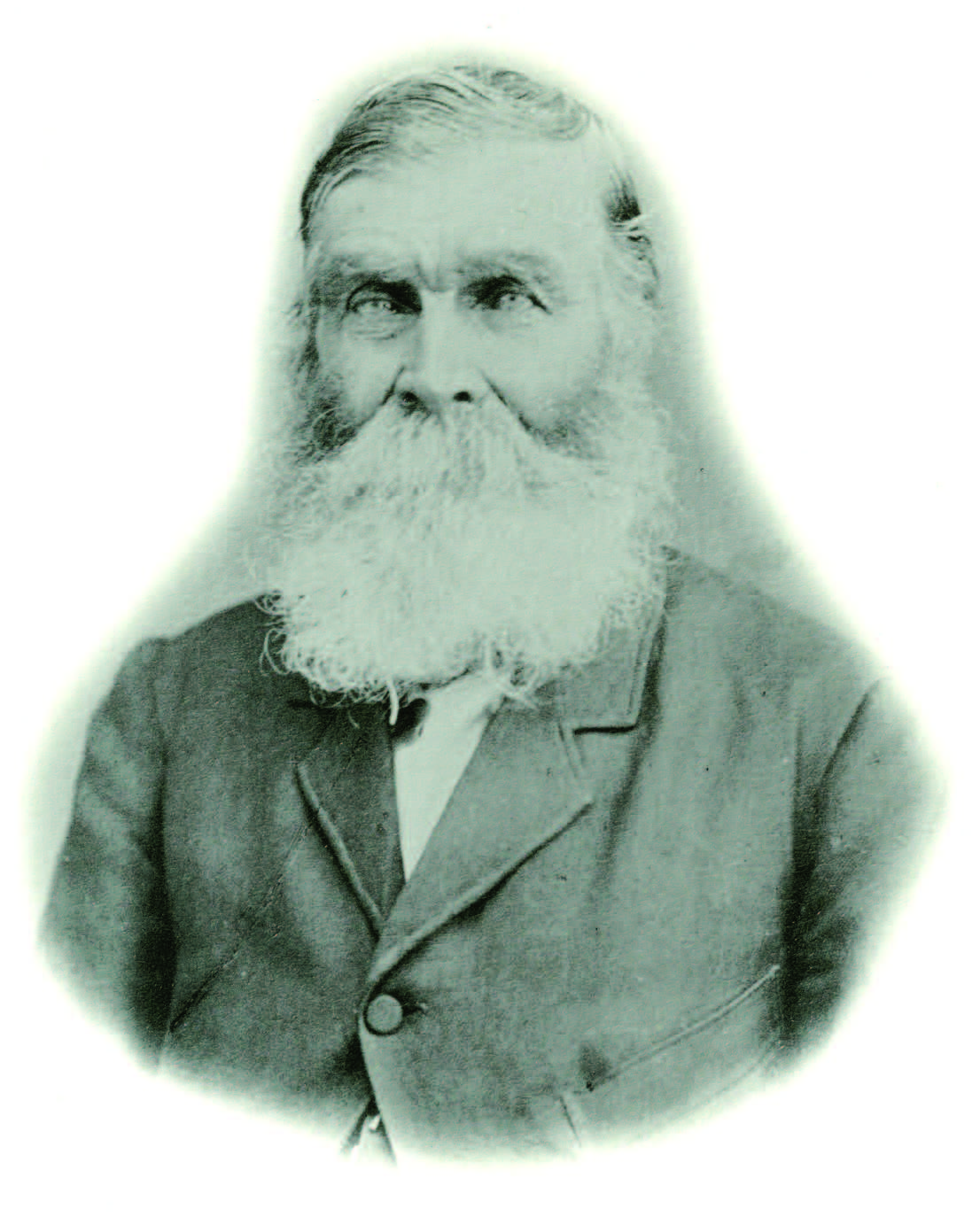

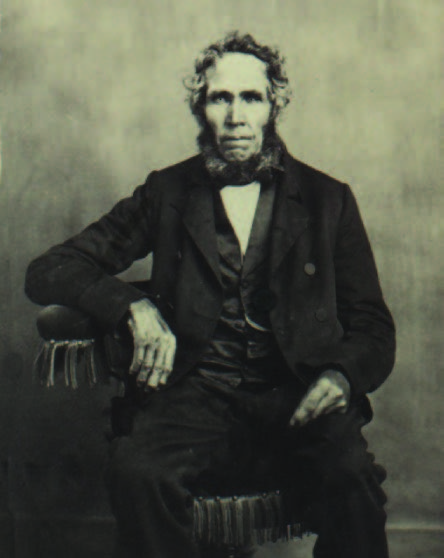

Daniel and Mary Snyder Wood were baptized by Brigham Young in February 1833 near Kingston, after which they moved to Kirtland. Daniel Wood later returned to the Kingston area as a missionary on at least three occasions. Woods Cross in Utah is named after him. (Church History Library)

Daniel and Mary Snyder Wood were baptized by Brigham Young in February 1833 near Kingston, after which they moved to Kirtland. Daniel Wood later returned to the Kingston area as a missionary on at least three occasions. Woods Cross in Utah is named after him. (Church History Library)

Brigham did not stay home for long. In April 1833, he embarked on another missionary journey. On his way to the Ernestown-Loughborough area of Upper Canada, he stopped for a time to preach in Lyons, New York, where he baptized thirteen and organized a branch. Among the converts in Lyons was a young man named Jonathan Hampton, whom Young ordained to the priesthood and recruited to be his missionary companion.[43] Young and Hampton preached on the American side of the border until 22 May, when they took a steamboat from Ogdensburg, New York, up the Saint Lawrence River to Kingston. They were greeted by Church members in Ernestown and Loughborough, who made them welcome in their homes. Young was pleased to find there had been seventeen people baptized since he and his brother Joseph were there three months earlier. In his journal account, Brigham Young mentioned the names of some of the Church members in the area—James Lake, Dennis Lake, William Draper, Daniel Wood, Henry Wood, Artemus Millet, Peter Boice, Brother Pixley, and Brother T. Lot.[44]

On 1 July 1833, Brigham Young, accompanied by the large James Lake family and others, forming a group of more than thirty, embarked from Kingston to Kirtland, Ohio. The group travelled by steamboat to the west end of Lake Ontario. They then went overland to Buffalo, New York, from whence some of the group went by boat to Kirtland, while the rest journeyed by land.[45] Daniel Wood, a recent convert from Loughborough, and his brother Abraham accompanied the group to visit Kirtland.[46] The following year, Daniel Wood sold his property in Loughborough and moved his family to Kirtland.[47] Upon arriving in Kirtland, Young assisted the Lake family to settle in their new home before he returned to his own residence in Mendon.[48] The Lakes were the first known Canadian family of converts to gather to the main body of the Church.

Joseph Smith’s First Visit to Canada

Joseph Smith departed from Kirtland to visit Upper Canada on 5 October 1833, accompanied by Sidney Rigdon and Freeman Nickerson.[49] Nickerson and his wife, Huldah, having been baptized in Dayton, New York, in April 1833, had a strong desire to share the gospel with two of their sons, Eleazer Freeman and Moses, who were operating a prosperous business in Mount Pleasant, Upper Canada, just south of Brantford. Nickerson had invited Joseph Smith to go with him and Nickerson’s wife to personally teach his sons of the restored gospel, providing the “team and conveyance” for the journey.[50]

On Friday, 18 October, the group arrived at the home of Eleazer Freeman Nickerson, in Mount Pleasant.[51] Smith recorded in his journal that, as he travelled through the prosperous and well-cultivated Canadian farmland, he “had many peculiar feelings in relation to both the country and people.”[52] Smith wrote that he and Rigdon were “kindly received,” although another guest in the Nickerson home, Lydia Bailey, revealed that the Nickerson sons initially had serious reservations about the presence of the Mormon prophet. Eleazer F. Nickerson told his father, “I will welcome them for your sake, but I would just about as soon you had brought a nest of vipers and turned them loose upon us.”[53]

After listening to Smith and Rigdon preach, the Nickersons softened their feelings. They sent out notices inviting all interested people to attend a public meeting at the Nickerson store the following night where Smith and Rigdon could further explain their beliefs. In the ensuing days, Eleazer and his wife, Eliza, accompanied their guests on visits to their friends in nearby communities so that they also could hear the gospel.[54]

Smith and Rigdon spent ten days in the area, preaching in Brantford, Colborne, Waterford, and Mount Pleasant, baptizing fourteen people, including Eleazer F. Nickerson; his wife, Eliza; his brother Moses; and Lydia Bailey.[55] The Prophet reported that during his visit to Upper Canada, “the spirit was given in great power to some,” and Lydia Bailey, who had been baptized the previous day, spoke in tongues.[56] Eleazer F. Nickerson was ordained an elder on 28 October and placed in charge of the branch there.[57]

Moses Nickerson reported to Sidney Rigdon on 20 December 1833 about the progress of the Mount Pleasant Branch since the departure of Rigdon and Smith two months earlier. There were at that time thirty-four members of the Church in the branch, all of whom were endeavouring to be faithful to their new religion. Five members of the congregation had spoken in tongues, and three had sung in tongues. Nickerson requested that more missionaries be sent to them soon.[58]

Preaching in the Toronto-Brantford Area

Lydia Goldthwaite Bailey was baptized by Jospeh Smith during his October 1833 visit to Mount Pleasant, Upper Canada. Lydia moved to Kirtland, Ohio, where she married Newel Knight in 1835. Their son jesse Knight, a Utah industrialist, and grandson Raymond Knight later played an important role in establishing the sugar beet industry in southern Alberta and founding the town of Raymond. (IRI)

Lydia Goldthwaite Bailey was baptized by Jospeh Smith during his October 1833 visit to Mount Pleasant, Upper Canada. Lydia moved to Kirtland, Ohio, where she married Newel Knight in 1835. Their son jesse Knight, a Utah industrialist, and grandson Raymond Knight later played an important role in establishing the sugar beet industry in southern Alberta and founding the town of Raymond. (IRI)

John P. Greene embarked on a missionary journey to Upper Canada in early May 1834. After a “tedious journey” through a heavy spring snowfall that was “distressing to both man and beast,” Greene arrived in Mount Pleasant, at the home of “Brother Nickerson.”[59] Greene was warmly welcomed by the Church members in the area, who were desirous of being further instructed in the gospel. Greene laboured in the area for two months with success, although he encountered some opposition. He wrote that the Lord’s “word is sown in Canada; it has taken root in good ground, and it will grow.”[60] In November 1834, another missionary labouring in Mount Pleasant, Zerubbabel Snow, reported that the Church was prospering in that area. He was able to preach to “many attentive congregations,” and he had more invitations to preach than he was able to accept.[61]

In May 1833, Horace Cowan and a companion, on a mission to the “Eastern country,” preached in the Niagara area. After viewing the falls, they travelled along the Niagara River, preaching at Youngstown and Lewiston on the US side of the river. They also preached at “the village at the head of Lake Ontario,” which likely refers to Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario.[62] On 11 June 1835, Peter Dustin departed from Kirtland to serve a mission in Upper Canada. He went first to Mount Pleasant and from there to Malahide, about fifty miles to the southwest. After two months of labour in the Malahide area, Dustin had established a congregation of thirty-two Church members. He spent the first month preaching and baptizing and the second month teaching and nurturing the new converts, hoping to fortify them against temptations and opposition from others.[63]

Nathan and Jane Staker, probably living in Pickering at the time, were baptized on 11 June 1835.[64] In July 1836, Almon W. Babbitt reported that he and Benjamin Brown had recently served a mission to New York, Pennsylvania, and Canada, in which they had many preaching opportunities and baptized about thirty individuals.[65] Orson Pratt of the Quorum of the Twelve left Kirtland on 6 April 1836 to do missionary work in Upper Canada. He laboured in Brantford and the surrounding area for two months, during which time he baptized twelve people and held a total of thirty-four meetings, despite concerted opposition.[66] Pratt also preached with his brother Parley in the Toronto area later that year.[67]

Six Apostles Visit the Kingston Area

In February 1835, twelve men were chosen and ordained as members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles—Thomas B. Marsh, David W. Patten, Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, Orson Hyde, William E. McLellin, Parley P. Pratt, Luke Johnson, William Smith, Orson Pratt, John F. Boynton, and Lyman Johnson—with a particular mandate to testify of the restored gospel to all the world. Joseph Smith, President of the Church, met with the Twelve in Kirtland on 12 March, instructing them to embark on a mission, travelling eastward to the Atlantic Ocean, holding conferences with various branches along the way. The Twelve were to give instruction to the Saints and regulate the branches located far from the main body of the Church. A schedule was drawn up by which the Twelve were to depart from Kirtland, Ohio, on 4 May and hold four conferences in northern New York from 9 May to 19 June; a conference in West Loughborough, Upper Canada, on 29 June; and five other conferences in Vermont, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine in the following weeks.[72]

The twelve men embarked on their mission as scheduled on 4 May.[73] On 23 June, after holding four conferences in New York, six members of the group opted not to go to Canada but to travel on towards Vermont for the conference scheduled there for 17 July.[74] Six members of the Quorum of the Twelve—Thomas B. Marsh, Brigham Young, Orson Hyde, William E. McLellin, Parley P. Pratt, and William B. Smith—agreed to continue to the conference at Loughborough, eighteen miles northwest of Kingston.[75] Marsh, McLellin, and Pratt had arrived in the Loughborough area on 24 June, where they visited Church members and preached on at least three occasions during the following days. Brigham Young, William Smith, and Orson Hyde were delayed, having been required to appear at a legal proceeding in Kirtland in defense of Joseph Smith, but afterwards they travelled to Upper Canada, where they joined Marsh, McLellin, and Pratt on 27 and 28 June.[76] Canadian converts Daniel Wood and William Draper, who were at that time living in Kirtland, accompanied Young, Smith, and Hyde to Loughborough to attend the conference.[77] Hyde and McLellin wrote, “Notwithstanding we had passed from the happy institution of our free republic into another realm, yet we could with propriety adopt the words of the presiding apostle and say, ‘God is no respecter of persons, but in every nation he that feareth God and worketh righteousness, is accepted of him.’”[78] These were the first known members of the Quorum of the Twelve to visit Canada, and, indeed, the first to travel outside the United States.

Orson Hyde was one of the first six Apostles to visit Canada, attending a conference at Loughborough (near Kingston), Upper Canada, in June 1835. Hyde also preached in the Toronto area the following year. (IRI)

Orson Hyde was one of the first six Apostles to visit Canada, attending a conference at Loughborough (near Kingston), Upper Canada, in June 1835. Hyde also preached in the Toronto area the following year. (IRI)

The conference began 29 June in West Loughborough, with thirty in attendance.[79] Parley P. Pratt presided at the conference, and members of the Twelve gave “much instruction” and “regulated the church,” appointing Frederick M. Van Leuven as presiding elder.[80] During the conference, which continued on 30 June, two were excommunicated and at least three were baptized.[81] The twenty-five Church members in the area were, according to Hyde and McLellin, “uninformeed in the principles of the new covenant, not haveing had an opportunity for instruction, being under another government and aside from the general course of the travelling elders: But we endeavored to instruction them faithfully in the knowledge of God.”[82]

On 1 July, four of the Apostles departed for their next scheduled conference in Vermont, but William E. McLellin and Brigham Young remained in the Ernestown-Loughborough area until 7 July, where they preached in Camden, Ernestown, and other locations.[83]

Parley P. Pratt’s Mission to Toronto

In April 1836, as other members of the Quorum of the Twelve were preparing to embark on missions, Parley P. Pratt was uncertain what to do. He knew he also should serve a mission, but he was deeply in debt, and his wife was seriously ill. Under those circumstances, he wondered if the Lord would justify him in remaining at home to care for his wife and pay his debts.[84]

One evening, Heber C. Kimball, one of his fellow Apostles, and others visited him. Kimball pronounced a “marvelous” blessing on Pratt’s head, prophesying that Pratt’s wife, Thankful, childless after nine years of marriage, would be healed and would bear a son, and that if Pratt would “go forth in the ministry, nothing doubting,” his temporal needs would be taken care of abundantly.[85] Kimball directed Pratt that he should “go to Upper Canada, even to the city of Toronto,” where he would “find a people prepared for the fullness of the gospel” and enjoy widespread success in establishing the Church in Toronto and the surrounding areas.[86] Kimball further prophesied that “from the things growing out of this mission, shall the fullness of the gospel spread into England, and cause a great work to be done in that land.”[87] With faith, Pratt prepared to embark on his mission, leaving within a few days.[88]

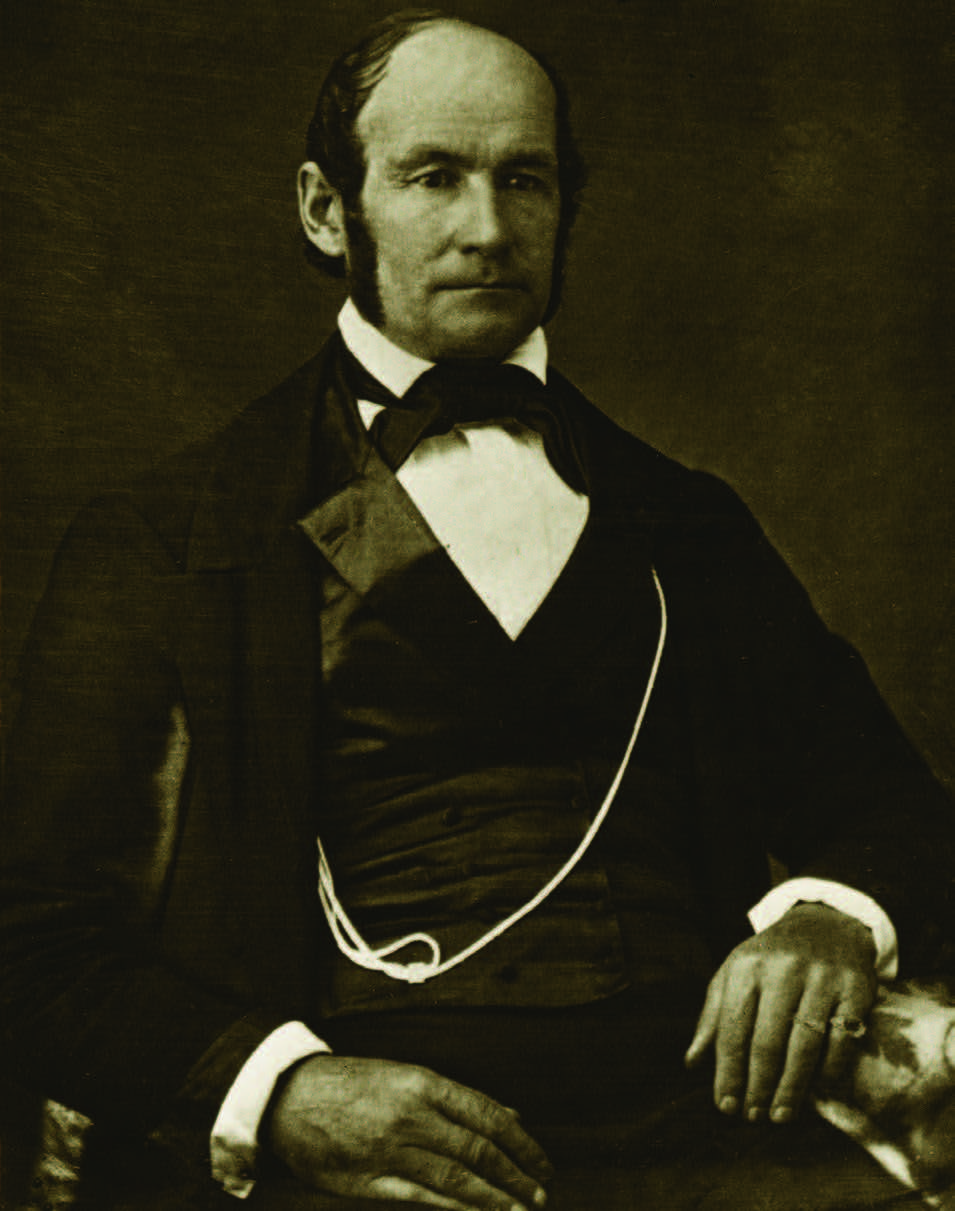

Parley P. Pratt exercised enormous faith in accepting a call to serve a mission in Toronto in 1836 despite crushing debts and a gravely ill wife. During his time in Toronto in 1836–37, he converted a significant number of people, including future Church President John Taylor and the legendary Mary Fielding, who became the mother of Joseph F. Smith, sixth President of the Church. (Church History Library)

Parley P. Pratt exercised enormous faith in accepting a call to serve a mission in Toronto in 1836 despite crushing debts and a gravely ill wife. During his time in Toronto in 1836–37, he converted a significant number of people, including future Church President John Taylor and the legendary Mary Fielding, who became the mother of Joseph F. Smith, sixth President of the Church. (Church History Library)

Pratt arrived at Niagara Falls by 22 April 1836, where he was awed by the majesty and power of God’s creation. Then, travelling on foot, he continued to Hamilton. Roads were very muddy and travel was laborious. The ice on Lake Ontario had recently broken up, opening the lake to steamboat traffic. Taking a boat from Hamilton to Toronto would save Pratt days of wearisome walking, but the cost was two dollars, and Pratt had no money. After praying in a wooded area, Pratt returned to Hamilton, where he was soon approached by a stranger who gave him ten dollars and a letter of introduction to a man in Toronto, John Taylor.[89]

Pratt, after arriving in Toronto on 25 April 1836, experienced rejection and a lack of interest on every side. He visited the John Taylor home, but Taylor showed little regard for his message. Pratt then approached each clergyman in the city, and they universally denied him the opportunity to preach in their churches. He sought permission to preach at the courthouse, marketplace, and other public areas, but to no avail. Having done all he could, he supposed, Pratt walked to a grove of pine trees just outside the city, where he knelt and prayed, telling the Lord of his unsuccessful efforts and pleading that, in light of Heber C. Kimball’s prophecy, somehow “an effectual door” could be opened to enable him to do the work he had been called to do.[90]

Pratt then returned to the John Taylor home, discouraged and preparing to leave the city. There he met Isabella Walton—a widow and a friend of John Taylor’s wife, Leonora—who reported that she had been prompted by the Spirit to visit the Taylor home at that exact time. After meeting Pratt and learning of his mission, Walton offered Pratt room and board and opened her home for preaching.[91] That evening, Pratt addressed a group of Walton’s friends and relatives gathered in her parlour, who listened attentively. In the days that followed, a growing number of people returned to Walton’s home to learn more from Pratt’s gospel instruction.[92]

John and Leonora Taylor were among the first to be baptized by Parley P. Pratt in Toronto in May 1836. John Taylor soon became an effective missionary and Church leader in the Toronto area. He later became an Apostle, preached the gospel in England, was with Joseph and Hyrum Smith in 1844 when they were martyred, and became President of the Church in 1877. (Church History Library)

John and Leonora Taylor were among the first to be baptized by Parley P. Pratt in Toronto in May 1836. John Taylor soon became an effective missionary and Church leader in the Toronto area. He later became an Apostle, preached the gospel in England, was with Joseph and Hyrum Smith in 1844 when they were martyred, and became President of the Church in 1877. (Church History Library)

On 1 May, through contacts he had made with Walton and others, Pratt was invited to attend a meeting of humble, sincere people who had been meeting together twice a week for two years to study the Bible and search for religious truth independent of any organized religion. Among that group were John and Leonora Taylor. John Taylor addressed the group, discussing the discrepancy between Christ’s original church and the doctrines and practices of current churches, noting the need to return to the pure gospel of Christ. Pratt offered to address those very issues later that evening.[93]

That night, Pratt preached at length to a large gathering, discussing the characteristics of the Christian church in New Testament times, the absence of these characteristics in current religions, and the recent Restoration of Christ’s ancient church through the Prophet Joseph Smith. Many were greatly interested in these teachings and returned in subsequent evenings to hear more. On 9 May 1836, John and Leonora Taylor were baptized, and numerous others also accepted baptism during that period, including Isabella Walton and her family, Walton’s brother Isaac Russell, and Joseph Fielding and his two sisters Mary and Mercy.[94]

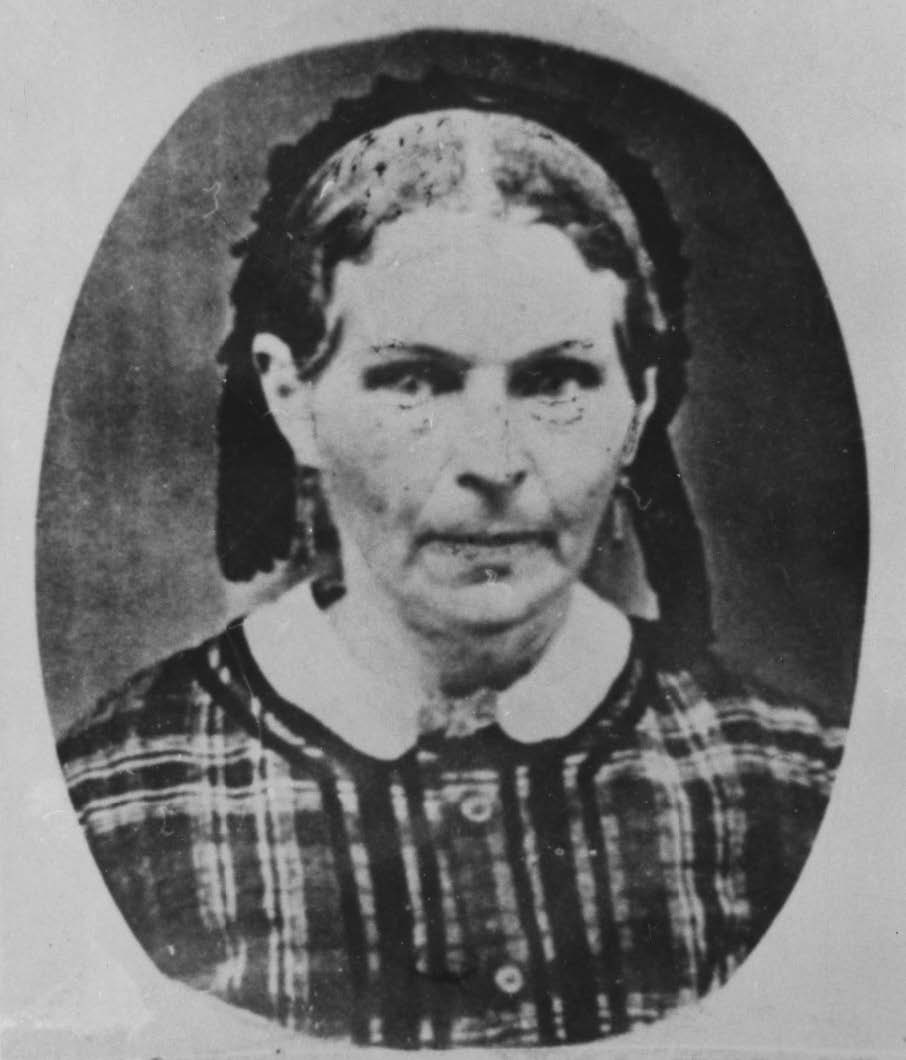

Mary Fielding, along with her brother Joseph and sister Mercy, moved to Kirtland in 1837, where Mary married the recently widowed Hyrum Smith and a year later gave birth to Joseph F. Smith, future Church President.[95] (Church History Library)

Mary Fielding, along with her brother Joseph and sister Mercy, moved to Kirtland in 1837, where Mary married the recently widowed Hyrum Smith and a year later gave birth to Joseph F. Smith, future Church President.[95] (Church History Library)

Black Creek was the site of baptisms in 1836, including those of Joseph Fielding and his two sisters Mary and Mercy. (Church History Library)

Black Creek was the site of baptisms in 1836, including those of Joseph Fielding and his two sisters Mary and Mercy. (Church History Library)

Pratt returned to Kirtland briefly in June 1836, bringing his wife, Thankful, back to Toronto with him. He immediately resumed his missionary work, which expanded to the point that he had to travel a circuit continually from branch to branch. More and more people were being baptized, and healings and other gifts of the Spirit were manifested.[96]

By July, when Orson Hyde arrived in Toronto to join Parley P. Pratt in the work, curiosity about Mormonism had greatly increased in the area. Thousands of interested people came to hear a debate between a “Mormon Preacher” (Hyde) and a prominent Presbyterian minister supported by five or six fellow clergymen. Citing numerous Bible passages, Hyde silenced the slanderous attacks of his opponent and delivered a lengthy discourse on the Restoration.[97]

Parley P. Pratt likewise engaged in debates with various religious leaders of the area. In one instance in 1836, he sought to meet with a well-known Irvingite minister named Caird, who had vigorously criticized and misrepresented Mormonism in his own preaching. Although Caird refused to enter into a public debate with Pratt, Pratt succeeded in obtaining a hall in Toronto in which he held two well-attended meetings, refuting Caird’s charges and putting forward accurate information on the Restoration. The hall, which had a seating capacity of three hundred, was provided by William Lyon Mackenzie, a prominent political figure and advocate of reform. Mackenzie’s newspapers had printed articles and information about the Church that, while not completely favourable, were much more sympathetic and fair-minded than other newspapers of the day. Mackenzie, while not in agreement with Pratt’s doctrines, believed strongly in religious pluralism and the right of people to believe as they wished.[98]

William Law was among the 1836 converts in the Toronto area. He was appointed president of the Churchville Branch in 1837 and, after leading a company of seven wagons to Nauvoo in 1839, became a prominent Church leader, serving as a member of the First Presidency from 1841 to 1844. The story turned to tragedy when Law developed strong objections to certain doctrines, including plural marriage, and to the leadership role of Joseph Smith in traditionally secular matters. Law was dropped from the First Presidency in January 1844, was excommunicated in March of that year, and became a bitter enemy of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Law’s publication of the Nauvoo Expositor on 7 June 1844 and the subsequent destruction of its press led to Joseph Smith’s incarceration and martyrdom in Carthage, Illinois, on 27 June.[99] Wilson Law, William’s brother, who accompanied him from Canada, was later baptized in Nauvoo, served on the Nauvoo City Council, and was a major general in the Nauvoo Legion. Becoming disaffected with Joseph Smith, Wilson Law left the Church in 1844 and supported his brother in his opposition to the Prophet.[100]

Sometime after October 1836, as Parley and Thankful Pratt, Orson Pratt, and Orson Hyde were leaving for Kirtland, the Apostles placed John Taylor in charge of the branches of the Church in the Toronto area.[101] By the time they departed Canada, Parley and Thankful had witnessed the further fulfillment of the prophecy of Heber C. Kimball: Several branches of the Church had been created in the Toronto area; the Pratts’ debts in Kirtland had been paid by generous Church members; and Thankful was expecting a baby, the couple’s first child after more than nine years of marriage. Their baby, a son, was born on 25 March 1837 in Kirtland and was given the name Parley. Thankful lived only three hours after giving birth. Pratt was deeply heartbroken by the death of his wife, but he acknowledged the Lord’s goodness in giving him a son. He coped with his grief by returning to Canada to follow up on his work in Toronto.[102]

When Parley P. Pratt returned to Canada in the spring of 1837, he enlisted missionaries to go to England. At a conference in Churchville, west of Toronto, on 24 April 1837, with twenty Church members in good standing in attendance, John Taylor prophesied that Joseph Fielding would be moved by the Spirit of God and would “lift up his voice in his native land” as a missionary.[103] Ultimately, four of Pratt’s Toronto converts—Joseph Fielding, Isaac Russell, John Goodson, and John Snider—were chosen to accompany Willard Richards and Apostles Heber C. Kimball and Orson Hyde as the first missionaries to England. The men departed New York City on 1 July 1837 and soon opened missionary work in England, with remarkable success in the Preston area, fulfilling another part of the prophecy of Heber C. Kimball.[104] Two years later, two other Toronto converts, Samuel Mulliner and Alexander Wright, were the first missionaries to take the gospel to Scotland.[105]

Heber C. Kimball made an extraordinary prophecy to Parley P. Pratt in April 1836 that if Parley would serve a mission to Toronto, he would convert many people, that the gospel would be taken to England as a result of his preaching, that his debts would be taken care of, and that his wife, Thankful, childless after nine years of marriage, would bear a son. By 1837, all of these prophecies had come to pass. (Church History Library)

Heber C. Kimball made an extraordinary prophecy to Parley P. Pratt in April 1836 that if Parley would serve a mission to Toronto, he would convert many people, that the gospel would be taken to England as a result of his preaching, that his debts would be taken care of, and that his wife, Thankful, childless after nine years of marriage, would bear a son. By 1837, all of these prophecies had come to pass. (Church History Library)

Meanwhile, Joseph Fielding’s sister Mercy had moved from Toronto to Kirtland, where she married Robert B. Thompson on 4 June 1837. The marriage ceremony was performed by Joseph Smith himself. Mercy’s husband was also an 1836 Toronto convert. Shortly after their marriage, the Thompsons were called to return to Toronto as missionaries, where they served until March 1838.[106] They were among the first missionary couples in the Church.

Joseph Smith’s Second Visit

The Prophet Joseph Smith, accompanied by Sidney Rigdon, First Counselor in the First Presidency, and Thomas B. Marsh, President of the Quorum of the Twelve, left Kirtland on 27 July 1837 to visit Church members in Canada.[107] On 2 August, a notice of their arrival appeared in a Toronto newspaper owned by William Lyon Mackenzie. The notice read, “We understand that Mr. Smith, the famed chief of the new sect called Mormons, who have suffered so much persecution in Missouri, and the great preacher Mr. Rigdon are in town.”[108]

Upon his arrival in Toronto, Joseph Smith immediately sent for John Taylor, who had been appointed to preside over the six branches of the Church in the Toronto area, in order to plan for the various meetings and conferences to be held during the following weeks. Taylor informed Smith that a high priest from Kirtland, Sampson Avard, had arrived in Toronto the previous spring with a spurious document, allegedly from Church leaders, assigning Avard the leadership of the Church in the Toronto-area. Smith, Rigdon, and Marsh proceeded to visit the Toronto area branches, including the Scarborough and Whitby branches, accompanied by John and Leonora Taylor, where Smith held conferences and firmly reestablished Taylor as leader of the Church in Toronto. Avard, the imposter, was strictly reproved for his deception.[109]

Isabella Horne, who, with her husband, Joseph, hosted the visiting Church leaders in their home and accompanied them on their visits to the branches in the Toronto area, recorded her experience: “When I first shook hands with [Joseph Smith] I was thrilled through and through and I knew that he was a Prophet of God, and that testimony has never left me.”[110]

Isabella Hales and Joseph Horne, just weeks after their marriage, heard the gospel from Orson Hyde and Parley P. Pratt in Toronto. They were soon baptized, bringing many family members with them into the Church. Joseph Smith stayed in their home when he visited Toronto in 1837. The Hornes went on to be important leaders in the Church and in their community in Utah. (Church History Library)

Isabella Hales and Joseph Horne, just weeks after their marriage, heard the gospel from Orson Hyde and Parley P. Pratt in Toronto. They were soon baptized, bringing many family members with them into the Church. Joseph Smith stayed in their home when he visited Toronto in 1837. The Hornes went on to be important leaders in the Church and in their community in Utah. (Church History Library)

John Taylor wrote of his experience during the Church leaders’ visit: “This was as great a treat to me as I ever enjoyed. . . . I had daily opportunity of conversing with them, of listening to their instructions, and in participating in the rich stores of intelligence that flowed continually from the Prophet Joseph Smith.”[111] Before Joseph Smith and his companions left Toronto at the end of August, they ordained John Taylor a high priest.[112]

John E. Page’s Mission to Leeds County and Surrounding Area

While Parley P. Pratt and others were winning many converts in the Toronto area, another effective missionary was operating in eastern Ontario, along the Rideau Canal. In May 1836, Joseph Smith asked John E. Page to serve a mission in Canada. Page declared that he was unable to serve because he had inadequate clothing, not even a coat for the northern climate. Smith responded by taking off his own coat and presenting it to Page, assuring him that he would be greatly blessed by the Lord in his missionary labours.[113]

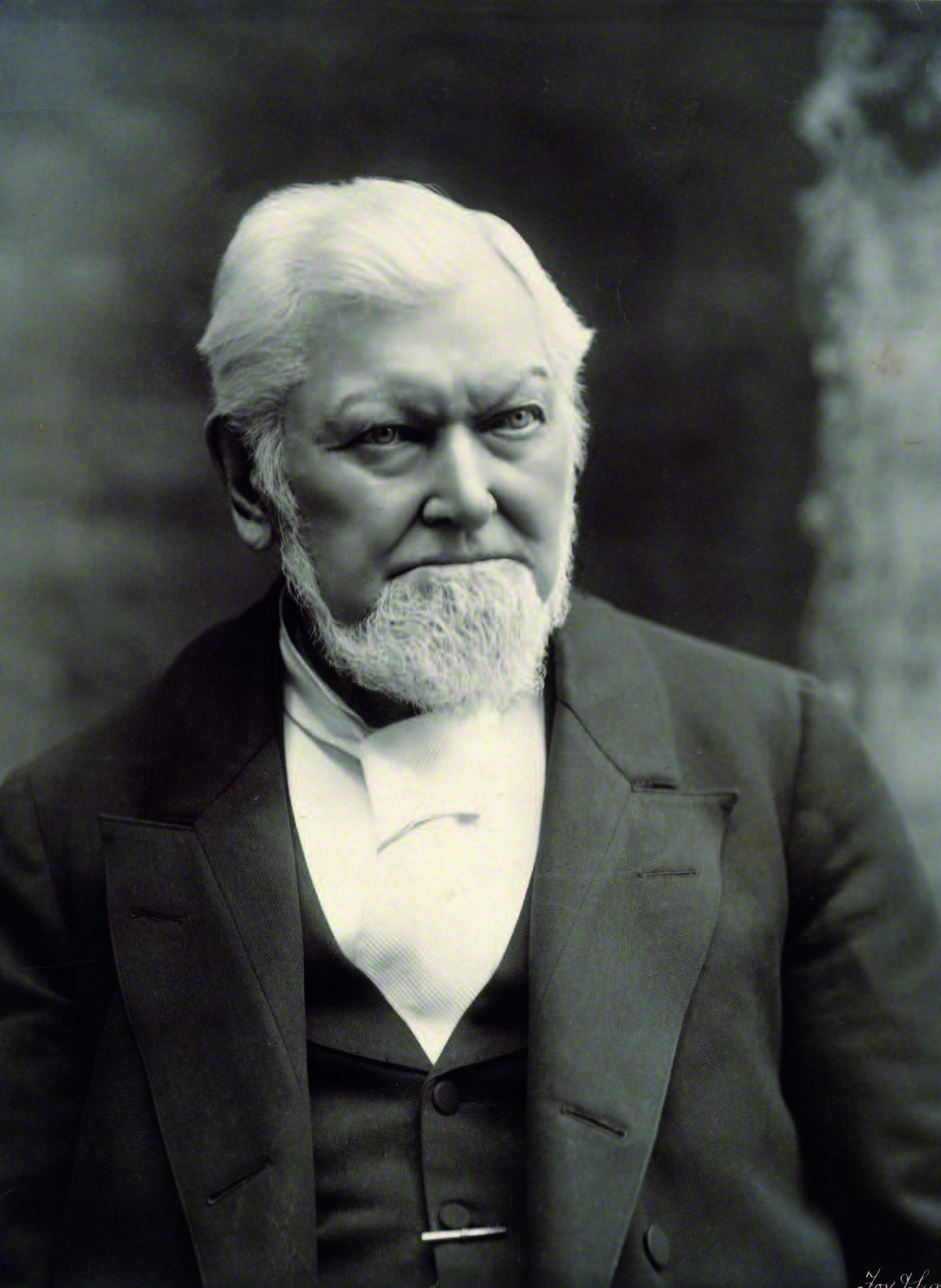

On 31 May, Page departed on his mission from Kirtland. His missionary companion for the first three months was William Harris.[114] Page and Harris began their labours in Loughborough Township, where they added fourteen converts to the Loughborough Branch. They then proceeded northward, preaching in communities along the Rideau Canal, including Leeds Church, Bedford, and North Crosby. In spite of the “ragings of wicked persecutors,” Page and Harris baptized a total of forty people before Harris departed for Missouri in early September. James Blakeslee joined Page as a missionary companion later that month.[115] They worked primarily in Leeds County in eastern Ontario.[116]

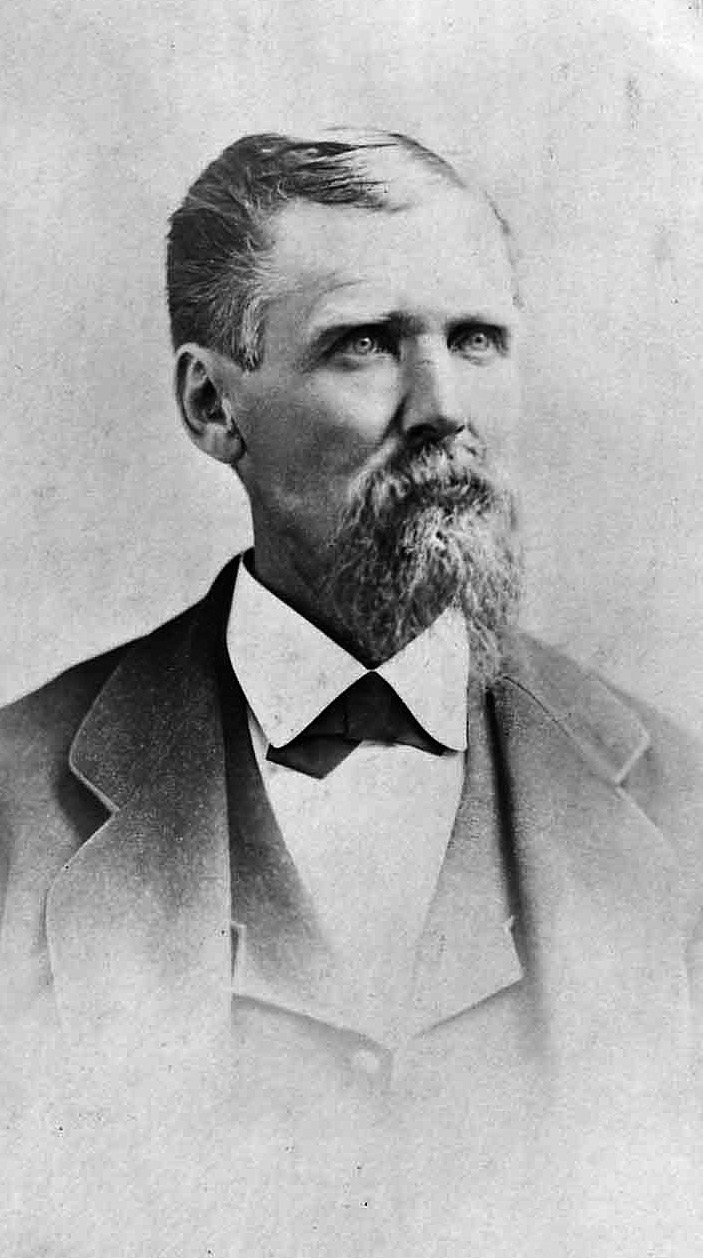

John E. Page was the most effective missionary to serve in Canada, baptizing more than six hundred people in eastern Upper Canada between 1836 and 1838. He led a group of his converts to Missouri in 1838 and was called as one of the Twelve Apostles. (Courtesy LDS Church Archives)

John E. Page was the most effective missionary to serve in Canada, baptizing more than six hundred people in eastern Upper Canada between 1836 and 1838. He led a group of his converts to Missouri in 1838 and was called as one of the Twelve Apostles. (Courtesy LDS Church Archives)

Page held three conferences among their numerous converts between September 1836 and January 1837. At a September 1836 conference at North Crosby, four men were ordained to offices in the priesthood. At another conference in November, sixteen were ordained. On 6 January 1837, Page presided at a conference in Loughborough, where three were ordained.[117]

After seven months of missionary labour, Page returned briefly to Kirtland, where, on 20 January 1837, he reported to Church leaders on his success as a missionary in Canada, where he and his companions had already baptized 267. He encouraged Church leaders to send other missionaries to Canada, where “a wide door is opening . . . for preaching.”[118] He departed Kirtland in February to return to his mission, bringing his wife and two children with him.[119]

Zadock Knapp Judd, nine years old at the time, later recorded his memories of his family’s introduction to Mormonism by Page and Blakeslee in early 1837: “They made quite a stir in the neighborhood. They preached new doctrine. My father went to their preaching and after hearing two or three sermons, I heard him make the remark if the Methodists would preach as they do and prove up all their points of doctrine like that how I would like it.”[120]

Page held a conference of the Church at Portland, Leeds County, along the Rideau Canal, on 11–12 June 1837. More than three hundred Church members in good standing were present at the conference, almost all of whom resulted from the missionary labours of John E. Page and his companions, William Harris and James Blakeslee, during the past thirteen months.[123] Branches represented at the conference included West Bastard, Bedford, Bathurst, North Bathurst, East Bastard, Williamsburg, Leeds, and South Crosby. The West Bastard Branch had the largest number at the conference, with seventy-three attending. Five more people were baptized during the conference.[124] Wilford Woodruff travelled by boat along the Rideau Canal to Portland to attend the conference. On 11 June, Woodruff addressed the large gathering and recorded that he had “peculiar feelings” as he “arose to address a large Congregation of Saints raised up in another nation under . . . the British government.”[125] Woodruff also recorded that there were thirty-two men ordained to the priesthood at the conference and reported significant experiences healing the sick there.[126] William Draper, an 1833 convert from the Ernestown-Loughborough area, also travelled from Kirtland to attend the conference.[127]

Missionary work continued. In late 1837 and early 1838, James Blakeslee, working alone along the Saint Lawrence River, preached the gospel in New Dublin, Saint John’s Island, Lansdowne, Elizabethtown, and Gananoque, baptized several, and formed a small branch.[128]

In May 1838, John E. Page completed his mission and departed from Canada, bringing with him a substantial number of his converts, some of whom travelled overland and some by water, to join the main body of the Church in Missouri. John E. Page had a highly successful mission, baptizing about six hundred people during the previous two years. While en route to Missouri, Page received word that he had been appointed a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.[129]

Dynamic Local Missionaries

The zeal of new converts greatly contributed to the dynamic missionary spirit that prevailed in Upper Canada in the 1830s and 1840s, where men were frequently baptized, ordained to the priesthood, and immediately sent on missions. Three examples of this widespread practice are given here.

William Draper was baptized and ordained in Loughborough in 1833, after which he “traveled and preached as circumstances permitted” until he departed for Kirtland with his family in September 1834. After settling his family in Kirtland, Draper returned to Upper Canada in the summer of 1835, where he preached in the Loughborough area and along the north shore of Lake Ontario, passing through Toronto, baptizing “quite a number” in his missionary journey.[130]

On 19 June 1837, less than six months after being baptized by John E. Page, Arza Adams began his first mission. Based at his home in Leeds County, Adams proselyted in areas nearby, preaching to friends and acquaintances. Two other recent converts from the area, William B. Simmons and Elder Stoddard, served as his companions during part of his mission.[131] A third example of a new convert becoming a successful missionary was Theodore Turley, who was baptized and ordained to the priesthood in Churchville in 1837, was called on a mission the day following his baptism, and within three weeks had baptized seventeen others.[132]

Gathering to Zion

Gathering with the main body of the Church was an important doctrine for early Latter-day Saints, including those in Canada. A substantial number of Canadian converts had emigrated from Canada to the United States prior to 1838. For example, Brigham Young led a group of more than thirty to Kirtland in 1833, and the Fieldings moved to Kirtland in 1837. John Ellis, because of the bitter opposition of his family after they learned of his baptism, departed from Toronto in the winter of 1837, going around the southern shore of Lake Erie from Buffalo, New York, to Kirtland Ohio, on ice skates.[136]

The year 1838, however, was a very big year for Canadian converts relocating to join the main body of the Church. The extended Ira and Joel Judd families, a group of Page’s converts from Bastard Township, had intended to leave for Missouri in the spring of 1838, but because of political unrest in Canada, they departed earlier, in midwinter.[137] In what has become known as the Rebellion of 1837–1838, William Lyon Mackenzie led dissatisfied insurgents in armed opposition to the British and the elitist Family Compact, which prevailed in Upper Canada, while patriote rebels in Lower Canada mounted an even more violent and generalized insurrection.[138] The Judds—who were planning to leave anyway, aware of the gathering political storm—feared that waiting until May might prove dangerous. Possibly they were concerned that in the event of hostilities, the Saint Lawrence River would be blocked. Zadock Knapp Judd, who was ten years old at the time, later described their caravan of six wagons pulled by oxen, accompanied by cattle and other livestock, crunching through the deep, crisp snow. He said the sound could be heard for miles. With the help of a local pilot, the caravan crossed the ice on the Saint Lawrence River to New York State. Four miles from the river, the Judd families settled in for the rest of the winter, feeling safe from “party strife” and prepared to complete their journey in the spring.[139]

Ira Nathaniel Hinckley and his brother Arza heard the gospel from John E. Page in 1836, when they were children. They accompanied their extended family, the Judds, as they emigrated from Leeds County, Upper Canada, to join the main body of the Church in 1838. Ira N. Hinckley later served for twenty-five years as president of the Millard Stake and became the grandfather of Church President Gordon B. Hinckley. (Church History Library)

Ira Nathaniel Hinckley and his brother Arza heard the gospel from John E. Page in 1836, when they were children. They accompanied their extended family, the Judds, as they emigrated from Leeds County, Upper Canada, to join the main body of the Church in 1838. Ira N. Hinckley later served for twenty-five years as president of the Millard Stake and became the grandfather of Church President Gordon B. Hinckley. (Church History Library)

John E. Page led a convoy of thirty wagons from Leeds County to Missouri in 1838, carrying a large group of converts.[140] Several other families, including the Arza Adams and Barnabas Adams families, also departed from Leeds County in 1838. In June 1838, Christopher Merkley, a local 1837 convert, led a company of local converts from Williamsburg, Upper Canada, to Missouri with eleven wagons and twenty-six horses. In addition to Merkley and his family, the company included the Francis and Alexander Beckstead families and the Stephen Kettle and Zenos H. Gurley families.[141] Some crossed the Saint Lawrence River on the ferry, and some travelled across the Great Lakes by boat.[142]

As John E. Page was departing from Leeds County in May 1838,[143] a large number of converts also emigrated from the Toronto area to Missouri that year, including the John Taylor, Joseph Horne, Theodore Turley, John Snider, Joel Terry, and Stephen Hales families.[144] Parallel to the Kirtland Camp, which moved from Kirtland to Missouri in the summer of 1838, a large group of Canadian converts, called the Canadian Camp, proceeded along a similar path. The two groups camped near one another in July and August, some labouring on a turnpike to earn needed funds to continue their journey. John E. Page was invited to preach to the Kirtland Camp on at least two occasions.[145]

Some Canadian communities were greatly affected by the conversion and departure of so many Mormons. One historian of eastern Ontario wrote that in 1838, schools in some communities were left empty.[146] One man from the Williamsburg area wrote to his mother in 1838, describing the large-scale exodus of many of their relatives and neighbours who went to join the Mormons in Missouri, noting that only seven or eight of their former religious congregation remained behind.[147] An historian of southern Ontario wrote that Mormon missionary activity in the Toronto area in 1836 caused the membership of the Canadian Methodists in the Young Street circuit to decline from 951 to 578.[148] Censuses taken after the “Mormon exodus” revealed the dwindling presence of the Church in Canada: in the 1851 Canadian census, only 247 people reported their religion as “Mormon,” and that number decreased to 74 in the 1861 census.[149]

The Missouri Experience

Canadian converts arriving in Missouri in 1838 encountered a severe test of their faith. Mob violence against Latter-day Saints in the state was widespread and escalating. On 2 October, an LDS settlement at De Witt was besieged by a menacing mob for two weeks. An armed skirmish between Mormons and Missourians took place at Crooked River on 25 October, in which David W. Patten of the Quorum of the Twelve was killed.[150] On 27 October, Lilburn W. Boggs, the Missouri governor, issued his infamous extermination order, stating that Mormons were enemies of the state and should “be exterminated or driven from the State if necessary.”[151] The massacre at Hawn’s Mill took place on 30 October.[152] On 31 October the Missouri militia surrounded Far West, where refugees had fled for safety from earlier mob violence in other areas, and arrested and incarcerated Joseph Smith and other Church leaders. The remaining members of the Church were disarmed, after which the “Missouri attackers committed numerous outrages against women and property.”[153] That winter, about twelve thousand Church members were obliged to abandon their property and leave the state, relocating to Illinois.[154]

Many Canadian converts shared in these fearful events.[155] Not surprisingly, some Canadian converts found that life among the Mormons was not for them. After arriving in Missouri in the fall of 1838 and experiencing firsthand the hardships and persecutions, Ami Chipman and his family, converts from Bastard Township, opted to abandon their new religion and return home. Chipman built a log canoe in which he and his family escaped down the Missouri River, returning to Canada a year after they departed.[156] But amazingly, most of the Canadian converts remained with the Church, received temple blessings in the Nauvoo Temple, and continued on to Utah.[157]

Among the Canadian converts emigrating in 1838 were important future Church leaders. John Taylor had just been called to the Quorum of the Twelve and later became President of the Church.[158] Ten-year-old Ira Nathaniel Hinckley later became president of the Millard Stake in Utah and grandfather to Church President Gordon B. Hinckley.[159] Seven-year-old Margaret Judd later became the mother of Rudger Clawson, who was President of the Quorum of the Twelve for twenty-two years.[160]

William Burton and his wife, Elizabeth, were baptized by Zerah Pulsipher in December 1837 in Mersea, Essex County, in southwestern Ontario.[161] Pulsipher and Jesse Baker, serving missions in the area, baptized twenty-two people between 29 November and the end of December and formed the Mersea Branch.[162] Before the missionaries left, they appointed William Burton to be the presiding elder.[163] In the autumn of 1838, most members of the Mersea Branch sold their property and departed to join the Saints in Missouri.[164] Robert T. Burton, one of the converts in Mersea, later became a member of the Presiding Bishopric of the Church in 1874 and served until his death in 1907.[165]

Robert T. Burton and many members of his family were converted in 1837 in Mersea, Essex County, Upper Canada. The family soon moved to Missouri to join the Saints there. Burton would become a member of the Presiding Bishopric in 1874. (© Utah State Historical Society)

Robert T. Burton and many members of his family were converted in 1837 in Mersea, Essex County, Upper Canada. The family soon moved to Missouri to join the Saints there. Burton would become a member of the Presiding Bishopric in 1874. (© Utah State Historical Society)

More Missionaries in Upper Canada

In June or July 1839, Arza Adams, Christopher Merkley, and William Snow departed from Illinois to serve missions in Canada. Adams and Merkley, both Canadian converts of John E. Page, had moved to Missouri in the summer of 1838. The missionaries laboured in Perth, Smiths Falls, Mountain, and in towns along the Saint Lawrence River. They visited family and friends in the area and did much preaching. In spite of considerable opposition, the missionaries had significant success.[166] Among their converts were the large families of William Empey, John Casselman, and David Wood of Osnabruck, Dundas County.[167] Merkley organized a branch at Mountain and reported that he and his companions had baptized a total of seventy-two people by the time they returned to their families in the Nauvoo area in May 1840.[168]

On 23 June 1841, Christopher Merkley embarked on his second mission to Canada. He laboured in eastern Ontario, visiting his father in Mountain and preaching at Vankleek Hill, and made one foray into Quebec. Several other missionaries served in the same general area at the same time, including Henry Jacobs, Murray Seamon, Amos F. Hodges, and Homer Duncan. Merkley proved to be a skilled advocate for the restored gospel, successfully defending it against concerted opposition by sectarian ministers and others. By the time he returned to Nauvoo in September 1844, he had baptized forty-one people, most of whom were in Canada.[169]

John Morrison, who had been converted by Arza Adams in 1840, reported that he and his companion, Elder Bates, had baptized twenty people in Kingston in 1841.[170] In April 1844, Gordon E. Deuel began his mission in St. Lawrence County, New York, after which he crossed the border into Canada. He baptized in L’Orignal, Upper Canada, and organized a small branch there. His mission was far-flung, as he also preached and baptized in Camden (near Kingston) and Niagara, in Upper Canada, as well as in Lower Canada.[171]

On 1 April 1840, Samuel Lake, a missionary, baptized twenty people in the Essa and Tosorontio area in Simcoe County, north of Toronto. In January 1841, he and his companion, James Standing, ordained Alexander Hill an elder and left him to preside over the branch. The branch contained several members of the extended Hill family in addition to other families.[172] In the summer of 1842, some members of the Essa and Tosorontio Branch departed from Canada to join the Saints in Nauvoo.[173]

In 1843, John Borrowman introduced the gospel to the Gardner family in Warwick, Lambton County. William Gardner and his wife, Janet, were the first of the family to be baptized, on 1 April 1843.[174] Other members of the family followed, including Gardner’s brothers Archibald and Robert, sister Mary, their spouses, and his mother. By 1845, Borrowman organized a branch in Warwick with about twenty-five members.[175]

Archibald Gardner and many members of his family joined the Church between 1843 and 1845 in Lambton County, Upper Canada. In 1846, Gardner sold his grist- and sawmills and other property at a great loss in order to gather with the Saints before they crossed the plains to Utah. He and his family cut a six-mile road through the wilderness—still known as the Nauvoo Road—to connect with a road that would take them more directly to Nauvoo. (Daughters of Utah Pioneers)

Archibald Gardner and many members of his family joined the Church between 1843 and 1845 in Lambton County, Upper Canada. In 1846, Gardner sold his grist- and sawmills and other property at a great loss in order to gather with the Saints before they crossed the plains to Utah. He and his family cut a six-mile road through the wilderness—still known as the Nauvoo Road—to connect with a road that would take them more directly to Nauvoo. (Daughters of Utah Pioneers)

During the winter of 1845–1846, John A. Smith arrived in Warwick, Ontario, bearing a message from Church leaders in Nauvoo. The Saints were being driven from Nauvoo and were expecting to travel to the Rocky Mountains soon. Church members in Warwick were encouraged to come without delay to join the main body of the Church and travel with them. The Gardners and other Church members immediately disposed of their property, suffering significant financial losses, and purchased wagons and supplies for their journey.[176] In their haste to unite with the main body of the Church, the Warwick Saints cut a six-mile road north from Alvinston through heavy forests to connect with Egremont Road, a more direct route to Sarnia and on to Nauvoo, thus saving about one hundred miles of travel.[177] One hundred years later, in 1946, a monument was erected in Alvinston commemorating this pioneer saga, and the route was officially named the Nauvoo Road.[178]

Preaching in Lower Canada

Between 1833 and 1841, missionaries made inroads in Lower Canada as well. In the summer and autumn of 1833, Horace Cowan and his companion, Hazen Aldrich, reported preaching once in Lower Canada in the course of their mission to the New England states, but they did not have any baptisms.[179] In 1835, the large Jeremiah and Sarah Sturtevant Leavitt family, living in Hatley, Lower Canada, and several members of their extended family received Church literature and learned of the restored gospel from a sister-in-law who had listened to missionaries preach. Members of the Leavitt family eagerly read the literature, embraced the message, and desired to be baptized. However, since there were no missionaries in the area, the family packed up and moved to Kirtland, where they received the ordinance of baptism.[180]

Sarah Sturtevant Leavitt and her husband, Jeremiah, learned of the gospel in 1835 in Hatley, Lower Canada. They and their children and many of their large extended family soon joined the main body of the Church, and after Jeremiah died in Iowa in 1846, the family continued on to Utah. This life-sized statue of Sarah stands in Santa Clara, Utah, to honour her faith, fortitude, and contribution to her family and community. Her son, Thomas Rowell Leavitt, was instrumental in founding Leavitt, Alberta. (Dean Louder)

Sarah Sturtevant Leavitt and her husband, Jeremiah, learned of the gospel in 1835 in Hatley, Lower Canada. They and their children and many of their large extended family soon joined the main body of the Church, and after Jeremiah died in Iowa in 1846, the family continued on to Utah. This life-sized statue of Sarah stands in Santa Clara, Utah, to honour her faith, fortitude, and contribution to her family and community. Her son, Thomas Rowell Leavitt, was instrumental in founding Leavitt, Alberta. (Dean Louder)

Hazen Aldrich and Winslow Farr came to Lower Canada in the summer of 1836. Aldrich reports that they established a preaching circuit which included Stanstead, Hatley, Compton, and Barnston. In most of these areas, the missionaries were allowed to preach in schoolhouses. In a three-month period, Aldrich baptized eleven people (probably including some of the Leavitt family who had not yet moved to Kirtland), and “many more were searching the Scriptures to see if the things preached were so.”[181] When Aldrich left the area, Winslow Farr remained behind for a time to continue the missionary effort, which, Aldrich predicted, had “just begun.”[182] In the autumn of 1841, two missionaries arrived in the Eardley area, west of Ottawa and north of the Ottawa River. As a result of their efforts, David Moore; his wife, Susan Mariah Vorce Moore; Barnabas Merrifield; and Merrifield’s wife, Clarissa, were baptized “on or about” 17 November 1841.[183] David Moore was baptized by Murray Seamon, one of the missionaries. The following day, the missionaries departed. The Moores and Merrifields made what preparations they could and left Quebec on 16 August 1842 to gather with the main body of the Church in Nauvoo.[184]

Missionaries in the Maritimes

While Upper Canada and Lower Canada shared the same geographical region as the early centres of the Church in New York and Ohio and enjoyed the benefit of the interior waterways, the Maritime colonies of North America—New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island—were more closely linked geographically with the nearby American state of Maine and shared the Atlantic communication links and the climate of the New England states.

Lyman Johnson and James Heriot preached in Nova Scotia as early as 1832 or 1833 as an extension of their missionary labours in several nearby American states, but there is no record of any baptisms there.[185] In 1836, Johnson, then a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, returned to the Maritimes with greater success, accompanied by Milton Holmes and James Herrit.[186] Johnson’s account does not mention visits to other Maritime colonies, but he specifically recorded being in New Brunswick, where he preached in Saint John and at various other places in the province. In Sackville, New Brunswick, he had his most notable success, writing that “through the assistance of God,” he had been able to establish a small branch of eighteen Church members there in the spring of 1836. The Sackville Branch was the first known Latter-day Saint branch to be created in the Maritimes.[187]

Among the 1836 Sackville converts was Sarah Ann Reynolds Merrill. Merrill, the mother of thirteen children, retained her testimony of the restored gospel for many years though her husband was an unbeliever, and she did not gather with the main body of the Church in the West.[188] Her son Marriner W. Merrill was baptized in 1852 in Sackville and later became a member of the Quorum of the Twelve, as did his own son, Joseph F. Merrill.[189]

The First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, October 1898. Standing on the far left is Marriner W. Merrill, an 1852 Canadian convert from New Brunswick. Next to Merrill is John W. Taylor, son of Canadian convert John Taylor. John W. Taylor would play a key role in the settlement of Latter-day Saints in southern Alberta. Fourth from the left is Rudger Clawson, son of Margaret Gay Judd. Judd’s parents had been baptized in Leeds County, Upper Canada, in 1836, when she was a small child.