A Distinctive Way of Life

Family, Health, Education, and Employment

George K. Jarvis and Jonathan A. Jarvis

George K. Jarvis and Jonathan A. Jarvis, “A Distinctive Way of Life: Family, Health, Education, and Employment,” in Canadian Mormons: History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Canada, ed. Roy A. and Carma T. Prete (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 498-515.

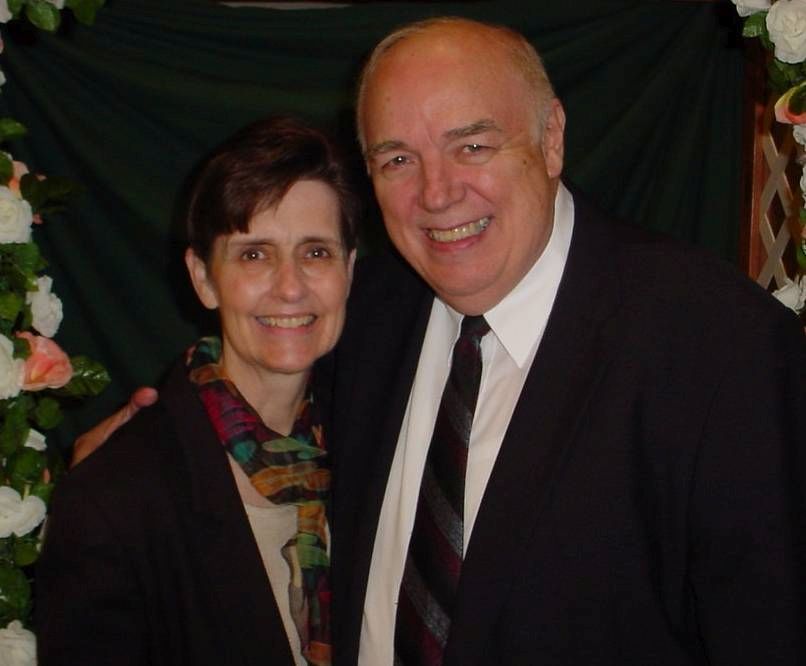

George K. Jarvis earned a PhD in sociology at the University of Michigan. After nine years at the University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario, he relocated to Edmonton, Alberta, in 1974, where he became a full professor and in 1996 professor emeritus of sociology at the University of Alberta. After retirement, he taught at the University of Hawaii in Honolulu. Professor Jarvis has published and consulted widely in sociology, including work on suicide, addictions, urban structure, and the demography of special populations, such as Mormons and native peoples. In 1978–79, he spent a sabbatical year in Geneva, Switzerland, working at the World Health Organization. As young people, he and his wife, Kathryn, served missions in Germany and France respectively. He also served three senior missions with Kathryn, one as president of the Romania Bucharest Mission. The Jarvises have six children and seventeen grandchildren. (Kathryn Jarvis)

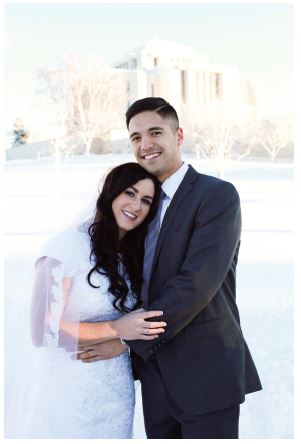

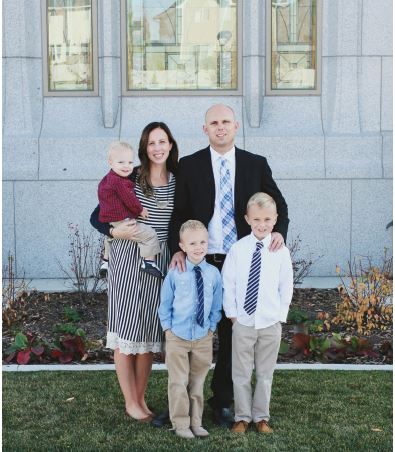

Latter-day Saints believe that families can be together eternally. Couples who are married for “time and eternity” in an LDS temple by proper priesthood authority are assured that their relationship will endure into the eternities if they follow Church teachings. Many of the characteristics of Mormons in Canada that distinguish them from their neighbours stem from their beliefs about the family. (Ashley Bennett)

Latter-day Saints believe that families can be together eternally. Couples who are married for “time and eternity” in an LDS temple by proper priesthood authority are assured that their relationship will endure into the eternities if they follow Church teachings. Many of the characteristics of Mormons in Canada that distinguish them from their neighbours stem from their beliefs about the family. (Ashley Bennett)

Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (often referred to as Latter-day Saints or Mormons) believe that they are different from the general population and that their beliefs and practices make them a distinctive people. They believe they are inheritors of covenants and promises made to the children of Israel and to early Christians. Moses referred to the tribes of Israel as a “peculiar people” (Deuteronomy 14:2). The Apostle Peter also called early Christians a “peculiar people” (1 Peter 2:9). In what respect were these chosen people “peculiar”? In Titus 2:14 , we read that Christ came “that he might redeem us from all iniquity, and purify unto himself a peculiar people, zealous of good works.” These references do not indicate that early Christians were odd or strange; rather, it indicates that they differed from others in their quest for a better way of life, and, because of this, they were particularly valued.

Differences between Latter-day Saints and others go beyond simple self-perceptions. Latter-day Saints in Canada today look and act very much like Canadians not of their faith and would like to be accepted by others, but they are empirically different or special in significant ways. The most notable of these is in their family structure, including more durable marriages and larger families. They also have better health and longer life due in part to a strong health code known as the Word of Wisdom, which forbids the use of tea, coffee, tobacco, and alcohol. Mormons value education, are somewhat better educated than the population at large, have a higher employment rate, and have greater mobility. There are several excellent reviews of these differences between Mormons and others in other countries, mainly the United States.[1] This study will concentrate on Canada and will use Canadian data.

Mormons in Canada

Mormons in Canada reflect not only the ethnic and linguistic features of the country but also its geographic breakdown. In addition, there are strong differences within the Mormon population based on their historic origins, depending on whether they have been long-term Mormons or recent converts. Some background as to the source of information and the variations among the population across the country is thus necessary to draw up a sociological profile of Latter-day Saints in Canada in the first decades of the twenty-first century.

Sources of Information

This chapter uses data from several sources but emphasizes material from the census of Canada. Canada is one of the few countries in the world that has for many years asked about religious identification in the national census. Some countries that ask about religion do not have a religiously diverse population, so in those nations the question is not as valuable. In Canada, the population is religiously diverse, enhancing the value of religious comparisons.

The Census of Canada takes place every five years, in years ending in “1” and “6” (i.e. 1996, 2001, 2006, 2011, etc.), and people are required by law to respond. All persons are asked basic household questions. One in five census respondents is asked a long list of questions which, in years ending with “1,” includes religious identification. In the Census of Canada, “religion refers to the person’s self-identification as having a connection or affiliation with any religious denomination, group, body, sect, cult or other religiously defined community or system of belief. Religion is not limited to formal membership in a religious organization or group. Persons without a religious connection or affiliation can self-identify as atheist, agnostic or humanist, or can provide another applicable response.”[2] He or she chooses with which, if any, religion he or she identifies. In recent years, the number of Canadians choosing “no religion” has been increasing. Since religion has become a sensitive question for many, some countries, such as England (2001) and Canada (2011) made this a voluntary question. The 2011 Canadian Census included the religious question in a voluntary “Household Survey.”[3]

The authors of this chapter have chosen to use data from the 2001 census instead of the 2011 census for a variety of reasons. Since the religious question was not required by law in 2011, the proportion of the population that responded was reduced. Other changes to the census in 2011—removing persons living in group quarters and reducing the sample of persons in rural areas and of immigrants—further made the 2011 data not comparable with earlier censuses.[4] By using the 2001 Canadian Census, we are able to consider demographic, cultural, family, education, and economic characteristics of the Mormon population as they compare to the Canadian population as a whole, since the religious question was still then mandatory. Although the 2001 census data are a little older than data from the Canadian Household Survey of 2011, they are more comparable to previous censuses and therefore allow more accurate comparisons with work on the Church using earlier Canadian census data.[5] Recently, the Canadian government reintroduced mandatory participation in the census long form for 2016, which makes the 2011 data an isolated occurrence which cannot be accurately compared with census data from years before and after 2011.[6]

Selected Demographic Characteristics

Demographic characteristics constitute a statistical description of a population. Though their effect may not be immediately obvious, they set the conditions that influence social life. For instance, the ratio of men to women, known as the sex ratio, affects the marriage chances of both men and women. Similarly, the size of a population affects its chances for notice and influence in the nation as a whole. In this section, we will consider the size of the LDS population in Canada; the distribution of Latter-day Saints, including rural-urban differences; and the distribution of Latter-day Saints at the regional level. Subsequent sections will deal with marriage, age, sex composition, and fertility within the Mormon concept of family; health and mortality within the Mormon lifestyle; and education, employment, and mobility as a reflection of related values.

Size of Group

Approximately 101,850 individuals identified themselves as having preference for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the 2001 census. This is a different number than the 167,000 that appears on Church membership rolls at that same time.[7] The discrepancy is based largely on the fact that the Church and the Canadian Government gather data on religion for different purposes. Once a person is baptized and confirmed, he or she tends to remain on Church records unless a specific request is made to remove his or her name from Church rolls. Church councils may also remove persons from Church records. The rest of the names remain on Church records even if the individual ceases to attend or have anything to do with the Church. This is not done to inflate the membership numbers and therefore the importance of the Church, as some seem to believe. Rather, the membership rolls include all those who have made a covenant through baptism and confirmation to obey teachings of the Lord as understood by the LDS Church. The Church feels a responsibility to reach out to such persons to encourage their religious participation.

Some people who have been confirmed as Church members no longer record an LDS preference in the census. Some have no current religious preference or have come to prefer another denomination. There may also be a few individuals who have never formally joined a religious group or are nominal members of another faith but prefer The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Sometimes these people are known as “dryland Mormons,” meaning not having been baptized. Overall, we make the assumption that those who voluntarily express an LDS preference are more likely to live a Mormon lifestyle and to be “more” Mormon in their characteristics than people who are members of the Church in name only.

Minerva Teichert, Rescue of the Lost Lamb. Laden with symbolism, this painting shows the tender care with which Christ seeks after the “lost sheep.” Church members feel a similar anxiety to seek after those who stray from the flock. (Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Minerva Teichert, Rescue of the Lost Lamb. Laden with symbolism, this painting shows the tender care with which Christ seeks after the “lost sheep.” Church members feel a similar anxiety to seek after those who stray from the flock. (Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Regional Distribution

Since the late nineteenth century, Alberta has been the centre of the LDS faith in Canada. Initially, most Latter-day Saints in Canada lived in small towns in Alberta following the Mormon pattern of farm communities rather than isolated farmsteads, as in much of North America. Over time, the percentage of Latter-day Saints outside the Alberta core has grown from 47 percent in 1965 to 58 percent in 2015.[8] Since this time, Mormons have gradually moved to larger places, as young Mormons have migrated to areas of greater educational and economic opportunity.[9] In Canada as a whole, this same pattern occurred, as young people tended to move to the cities, leaving older populations to age in place in rural areas.[10]

Rural-Urban Residence

There are also other differences between Alberta and non-Alberta Mormons that may not relate directly to observance of Church standards. Many Mormons in southern Alberta live in smaller towns, although in recent decades the number living in cities has increased. Mormons in other provinces are much more likely to live in large places.[11] A whole range of attitudes and experiences separate persons from urban and rural backgrounds. As a result, the LDS Church population is not the same in all provinces of the country.

For instance, LDS congregations in large places are more ethnically diverse, are more educated, and have different occupations than in smaller places. In Canada, there are more immigrants in larger communities and fewer in smaller places.[12] For these reasons it is important to look beyond simple comparisons of Latter-day Saints with other persons in the total Canadian population; it is also important to examine comparisons of Alberta Mormons with those living in other provinces. Mormons in Edmonton and Calgary may be more like Mormons in other large cities than like Albertans from smaller places.

Family Patterns

Marriage

Children are taught from an early age to reverence the temple as the Lord’s house and to prepare themselves to receive its blessings, including that of eternal marriage. Pictured here is the family of Ashley and Tom Bennett, with children left to right, Jones, Grayder, and Porter, beside the Calgary Alberta Temple. (Ashley Bennett)

Children are taught from an early age to reverence the temple as the Lord’s house and to prepare themselves to receive its blessings, including that of eternal marriage. Pictured here is the family of Ashley and Tom Bennett, with children left to right, Jones, Grayder, and Porter, beside the Calgary Alberta Temple. (Ashley Bennett)

It is part of Mormon theology that the greatest rewards in the hereafter may be claimed only by a couple that are sealed in marriage for time and eternity. Mormons’ beliefs on marriage and the family provide much of the driving force for their distinctive patterns of family life.

For Mormons, the temple provides a sacred setting for marriages and vicarious ordinances for those who are dead and whose identities are established by genealogy, thus building family networks that exist eternally. This at once shows the importance of the family for Mormons and justifies the great time and expense spent in gathering genealogical data and family history.

Another aspect of LDS family emphasis is giving great attention to children and young adults. Special meetings, classes, and a wide range of activities seek to familiarize LDS youth with the values of the Church and to bind them to their families and their ancestors. More Mormon youth attend church in their parents’ religion than do youth in most other churches.[13] These youth typically know their religion better, know the scriptures better, believe their religion more fervently, and struggle with social problems less than the youth of other faiths.[14] These are group differences and should not cause us to ignore that even among LDS youth, a significant proportion choose different lifestyles than those of their parents.

This family from Qualicum, British Columbia, is engaged in cleaning the flower beds. Since 1991, Church members have cleaned and maintained Church buildings on a voluntary basis. (Serenity Roulstone)

This family from Qualicum, British Columbia, is engaged in cleaning the flower beds. Since 1991, Church members have cleaned and maintained Church buildings on a voluntary basis. (Serenity Roulstone)

Mormons tend to marry earlier than others, and they are more likely to marry. As a result, one would expect that Mormons would be more likely to be married than other Canadians. In 1981, Mormons had a high proportion of marriages before the age of thirty (95 percent for Mormon males and 96 percent for females). This was higher than the national rates by 4 percent.[15]

Despite the time that they spend on missionary work and postsecondary education, Mormons tend to marry at a younger age than most Canadians. In 1981, the majority of Mormon families in Canada, or 63 percent, were traditional, consisting of a father, a mother, and children, as compared to 57 percent for the country as a whole. Conversely, families of husbands and wives only, newlyweds, and seniors, made up 24 percent of Mormon households, while the national figure was 32 percent.[17]

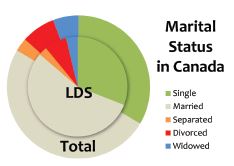

In the 2001 census, 58.3 percent of Latter-day Saints were currently married and not separated, whereas 50 percent of Canadians as a whole were similarly married. This relationship is even stronger in Alberta and in large cities of Alberta, such as Calgary, where there are more members who have been in the Church for multiple generations and have been subject to more promarriage socialization throughout their lives. Encouragement to marry is strong among Latter-day Saints. More Saints over the age of fifteen had been married (69 percent), as compared to the general Canadian population (66.5 percent). Older single Latter-day Saints sometimes express a feeling of discomfort with not being married, although there are special programs in the Church for young single adults (through age Thirty-one) and for older single adults as well. Single adults attend meetings of the Church, hold offices in the Church, and attend the temple, meeting the same standards of worthiness as married persons.

Divorce

Mormon families have shown evidence of instability and change, although at a somewhat lower rate than other Canadians. For separated or divorced males in 1981, the Mormon rate was 5.8 percent, compared to 6.6 percent for the country as a whole. For females the proportion was 12 percent for Mormons, compared to the national figure of 8.9 percent. This result may be explained by the propensity of divorced females to join the LDS Church. A higher proportion of divorces among Mormons was found in the east than in the west, reflecting regional differences in male-female ratios, intergroup marriage rates, and the length of active Church involvement.

Divorced Canadians outnumber divorced Latter-day Saints (7.7 percent to 7.2 percent in the 2001 census). This indicates a slight upswing in proportion of divorce for both Canadians and Mormons since 1981. Mormons have fewer divorces than other Canadians, although some persons have been divorced before they join the Church as adults.

Widowed persons show some striking differences. Canadians as a whole have 5.8 percent widowed, and Latter-day Saints have only 3.7 percent.[18] Latter-day Saints live a healthy lifestyle (described later in the chapter), and LDS couples have more years of life together. Even separated persons are more common among non-LDS Canadians than Latter-day Saints.

Single, Never Married

Throughout Canadian cities, the proportion of Latter-day Saints who are single persons never married is roughly similar in the LDS population to the non-LDS Canadian population. An exception is in the city of Toronto, where the proportion of singles among Latter-day Saints is greater than in the overall population. Explanations for this may include the migration of young, single Latter-day Saints to Toronto for jobs and education. However, another possible factor is that in response to the pressure to marry, singles in the Church gravitate toward a place where other eligible persons live and where there are units of the Church for singles only.

Cohabitation

A pronounced trend in the modern family is that many people choose to cohabit with each other without formal, legal marriage. Among Canadians in private households in 2001, 7.8 percent were living in such a cohabitation arrangement. Among Mormons only 2.4 percent were cohabiting.[19]

This difference is expected because cohabitation is prohibited in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Those who do this are urged by Church leaders to formalize the marriage or to cease cohabiting. If the couple does not stop cohabiting, they may be subject to Church discipline, which could result in either disfellowship or excommunication from the Church. Disfellowship is a partial reduction of Church privileges, whereas excommunication represents complete loss of Church membership. Neither condition is seen as permanent, and efforts continue to assist the person to return if he or she desires to do so.

Sexual Relationships

In the Latter-day Saint view, “marriage is ordained of God” (Doctrine and Covenants 49:15). Sexual relationships are intended for legally and lawfully wedded spouses but are forbidden among those who are not married. Homosexual marriages are not recognized by the Church even if they are legal in the jurisdiction where the couple live.

Fertility

Members are taught that it is good to bring spirit children into their homes through birth and that these children can be theirs for eternity. These doctrines encourage fertility. Contraception is not forbidden, but members are taught not to limit families for selfish reasons. Abortion is proscribed except under a few carefully limited circumstances, such as rape, incest, obvious fetal malformation, and serious threat to the mother’s health.

Warren and Nadine Edis and their family in 1995. The 1995 family proclamation, issued by the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the Church, reiterated the Psalmist’s affirmation that “children are an heritage of the Lord” (Psalm 127:3) and reaffirmed many traditional family values. Despite the declining birthrates in Canada, LDS families with four or more children are not uncommon. (Nadine Edis)

Warren and Nadine Edis and their family in 1995. The 1995 family proclamation, issued by the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the Church, reiterated the Psalmist’s affirmation that “children are an heritage of the Lord” (Psalm 127:3) and reaffirmed many traditional family values. Despite the declining birthrates in Canada, LDS families with four or more children are not uncommon. (Nadine Edis)

The Mormon fertility rate is consistently greater than average. In 1941, the average Mormon family had between five and six children. The figure has remained comparatively high, although it has followed the secular trend downward. In 1981, the average Mormon woman had 3.2 children in western Canada and 2.7 in the east, as compared to the national average of 2.5 children.[20] A different way of ascertaining fertility from census data is to look at the proportion of census family members that are children. In non-LDS Canadian families in 2001, 19.4 percent of the population under age fifteen were children; in LDS families, 26.3 percent were children.

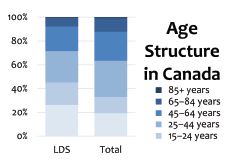

Age Distribution

The age distribution of a group largely reflects past fertility. If past fertility has been high, the proportion of the group under age fifteen will be large, and the population age sixty-five and over will be correspondingly small. The reverse is true for a group that in the past has had relatively few babies born. Mortality and migration have lesser effects on the age composition than does fertility. Latter-day Saint theology favours marriage and family. Children are viewed as spirit children of God, sent to earth for the mutual benefit of parent and child. Family members have an eternal investment in each other, as family ties are extended beyond this life.

Since Latter-day Saints throughout the world tend to have more children than average, one would expect to see a greater proportion of Canadian Latter-day Saints under age fifteen and a smaller proportion aged sixty-five and over. This is true in all provinces and in major cities across the country. Because they have more children, Latter-day Saints are particularly concerned about them and have many programs for their benefit.

The Mormon population in Canada is more youthful than the non-LDS Canadian population. The difference between LDS age structure and that of non-LDS Canadians reflects the Mormon emphasis on family, a somewhat higher birthrate, and a lower mortality rate.

The Mormon population in Canada is more youthful than the non-LDS Canadian population. The difference between LDS age structure and that of non-LDS Canadians reflects the Mormon emphasis on family, a somewhat higher birthrate, and a lower mortality rate.

Working-age adults are a smaller proportion among Latter-day Saints in Canada and throughout the provinces. An exception is in Vancouver, which is a destination for young, working Latter-day Saints. Where the proportion of working adults is smaller, as among Latter-day Saints, there is a greater burden on the LDS working-age population. They must support and train a larger number of children. On the other hand, older persons benefit. While they have smaller numbers, there are more young persons to love them and take care of them. Strong solidarity of families and norms of helping the elderly also benefit the LDS elderly population.

Two other factors may affect the age composition of Latter-day Saints in Canada: the number of persons who immigrate to the country or emigrate from the country, and the age composition of those joining or exiting the membership rolls of the Church. For instance, if members of the Church who immigrate to Canada are more youthful than average, this will lower the average age of the LDS population. The same is true for converts to the Church, who tend to be somewhat younger than the average Latter-day Saint. Emigrants may similarly change the age composition by the subtraction of their age characteristics.

Sex Ratio

The sex ratio is the number of males per one hundred females. It describes the makeup of the population with respect to males and females. Such a statistic has vital social consequences for marriage and social life, as well as for procreation. For a population to have a maximum chance for marriage and procreation, the number of males and females should be roughly equal. Disparities such as an overabundance of males or females reduce the chances for marriage, procreation, and normal concourse between the sexes.

At birth there is a slight surplus of males over females, unless there is selective abortion or infanticide. The sex ratio at birth is usually about 105 or 106 males for every 100 females. The propensity for males to die more than females through life results in a sex ratio much less than one hundred in old age. In advanced age in Western societies, the sex ratio may be as low as 50 males for every 100 females, representing only half as many males as females. In rural areas there is typically a sex ratio of more than 100, showing a majority of males. In many urban areas the sex ratio is less than 100 unless the manufacturing base predominates.

The sex ratio has been declining over the past twenty years for both Mormon and non-Mormon Canadians. Perhaps women are receiving more benefit from increases in life expectancy. In 1981, the Mormon sex ratio was 91.9 compared to 98.6 for non-Mormon Canadians. In 1991, the ratio of males to females among Mormons in Canada was 90.5; for the non-Mormon population it was 97.7. In non-Mormon Canadians in 2001, the sex ratio was 96.6, and the typical pattern by age is evident: a sex ratio more than 100 in childhood, about 100 during the prime years for marriage selection, and further declines with age. Among Latter-day Saints in Canada the sex ratio is 88.4, which shows fewer males and more females than average for Canada. Marriage has a high value among Latter-day Saints, and the fact that the sex ratio is less than average indicates a slight disadvantage for females in the selection of partners. As a result, some females find it difficult to marry or to remarry. This produces special suffering in a society that values marriage and family so highly. Women who are not able to find a partner often feel that they are not full participants and feel insecure about their future in this life and the next.

Single adults Curtis Connors, left, from Belleville, Ontario, and Miles Detlor, from Napanee, Ontario, in costume at a single adult dance in Ottawa in 2011. The Church fosters programs and activities for young single adults, ages eighteen to thirty-one, and for singles thirty-two and over, which provide activities for social, cultural, athletic, and spiritual enrichment, as well as service opportunities. (Curtis Connors)

Single adults Curtis Connors, left, from Belleville, Ontario, and Miles Detlor, from Napanee, Ontario, in costume at a single adult dance in Ottawa in 2011. The Church fosters programs and activities for young single adults, ages eighteen to thirty-one, and for singles thirty-two and over, which provide activities for social, cultural, athletic, and spiritual enrichment, as well as service opportunities. (Curtis Connors)

Health, Mortality, and Life Expectancy

In 1833, just three years after the Church was organized, Joseph Smith gave the Latter-day Saints a set of health rules called the Word of Wisdom.[21] Members of the Church believe these rules are given from God and that if they are followed, the risks of premature death and ill health are reduced. Not only will physical health be enhanced, but the individual will realize spiritual benefits, such as receptivity to the promptings of the Holy Ghost and the knowledge that accompanies this blessing.

The Word of Wisdom instructs Latter-day Saints to abstain from the use of alcohol, tobacco, and hot drinks. Church leadership later interpreted “hot drinks” to mean tea and coffee. Obedience to these proscriptions increased gradually through the early years of the Church.[22] These prohibitions have been expanded during the last century to include the use of illegal drugs and the misuse of prescription medications.[23] Obedience to these commandments is a requirement for full fellowship in the Church, including permission to enter the temple and eligibility to hold major callings in the Church. Following this commandment is a visible symbol of obedience to the gospel and unity with fellow believers.

The Word of Wisdom also encourages reduced consumption of meat in conjunction with a diet that emphasizes natural grains, fruits, and vegetables. Many Latter-day Saints interpret it as a stewardship of the mortal body that should be cared for by proper sleep, exercise, and healthy practices. These parts of the Word of Wisdom are left to individual interpretation but provide a general impetus to healthy living.

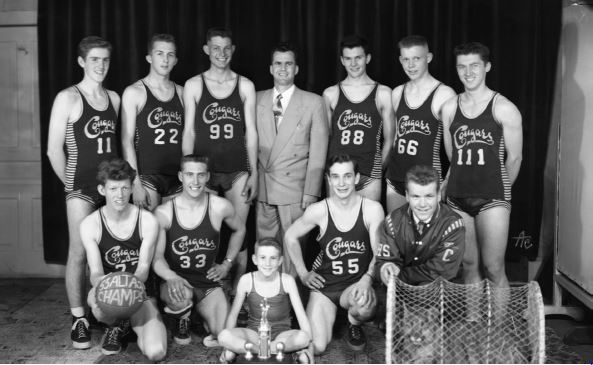

Cardston, Alberta, basketball team, ca. 1954. Many Latter-day Saint meetinghouses come equipped with a cultural hall that serves as a gymnasium for sports and other recreational activities. Basketball is the preferred sport among Latter-day Saint youth in much of Canada. In addition to the health law contained in the Word of Wisdom, leaders encourage exercise and physical activity. (Glenbow Archives ND-27-90)

Cardston, Alberta, basketball team, ca. 1954. Many Latter-day Saint meetinghouses come equipped with a cultural hall that serves as a gymnasium for sports and other recreational activities. Basketball is the preferred sport among Latter-day Saint youth in much of Canada. In addition to the health law contained in the Word of Wisdom, leaders encourage exercise and physical activity. (Glenbow Archives ND-27-90)

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in the United States regularly conduct studies of substance use. Studies in Utah demonstrate that Mormons use tobacco and alcohol less often than other residents of the state do. Several studies in the 1970s found that Latter-day Saints had lower death rates from cancer and cardiovascular disease in California, Utah, and Canada.[24] They also found evidence that Mormon men and women who participate in the religion have a greater benefit with respect to cancer and cardiovascular disease than do less-active Latter-day Saints. Mormon men showed greater reduction in these diseases than did Mormon women.[25]

The earliest study of Mormon mortality in Canada was done in 1977 by George K. Jarvis (coauthor of this chapter). In this study of mortality among Alberta Mormons, he gathered deaths on Church records, and linked these records with official death certificates.[26] He obtained age and cause of death from official records allowing conclusions about risks of cancer and other causes of death among Mormons and the non-Mormon population. Mormons were at significantly lower risk of dying from cancer than were other persons. This was especially true for deaths related to alcohol and tobacco use. Mormons also had a substantially lower risk of dying from cardiovascular disease and stroke. LDS men realized greater gains than LDS women compared to other residents of Alberta, though both men and women benefited.

A major study of mortality among active members of the LDS faith, which concluded in 2004, examined a sample of 9,815 religiously active Mormon adults in California.[27] They were followed from 1980 to 2004 and compared to 15,832 representative US white adults enrolled in the 1987 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), who were followed from 1988 to 1997. This study found that active Mormons in California tend to have a strong family life, achieve higher-than-average education, and avoid tobacco or alcohol. Unusually low risks of death occurred among Latter-day Saints who were married, never smoked, attended Church weekly, and had at least twelve years of education. This subgroup of actively participating California Mormons at age twenty-five could expect to live to 84.2 years for males as compared to 74.3 years for the white American male population. Active LDS females at age twenty-five could expect to live to 86.1, as compared to 80.5 years for the white American female population. LDS gains in health and mortality risks seem to be especially important in young adulthood and through middle age. Deaths occurring to youth and those in middle age are especially traumatic to survivors. Similar to what was found earlier in Canada, Mormon families avoid many of these events.

These findings are of immense importance for members of the Church. Practicing Mormons in California, according to the authors in the study, had the lowest total death rates and the longest life expectancies ever documented in a well-defined US group. The same seems to be true in Canada as well.[28] And there is another significant fact to emerge from the study: the more strictly Mormons follow Mormon lifestyle and participate in the Church, the longer they live. The authors concluded that the findings suggest a model for substantial disease prevention in the non-Mormon population.[29]

The ideal of multigenerational families, with each generation as securely anchored in the faith as the previous, is often realized in Mormon culture. (Ashley Bennett)

The ideal of multigenerational families, with each generation as securely anchored in the faith as the previous, is often realized in Mormon culture. (Ashley Bennett)

Grandparents play a significant role in transmitting the faith heritage from one generation to the next. Because of a longer life expectancy, more Mormon young people will have had the experience of knowing their grandparents and interacting with them than most non-Mormon Canadian grandchildren. Blair and Jane Bennett, with grandchildren, left to right, Grayden, Jones, and Porter. (Ashley Bennett)

Grandparents play a significant role in transmitting the faith heritage from one generation to the next. Because of a longer life expectancy, more Mormon young people will have had the experience of knowing their grandparents and interacting with them than most non-Mormon Canadian grandchildren. Blair and Jane Bennett, with grandchildren, left to right, Grayden, Jones, and Porter. (Ashley Bennett)

In 2004, Ray M. Merrill, a BYU professor, compared life expectancy between members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the non-Mormon population in Utah.[30] Life expectancy at birth was 70.0 years for non-LDS males and 77.3 years for LDS males, and 76.4 years for non-LDS females and 82.2 years for LDS females. Latter-day Saints thus lived an additional 7.3 years for males and 5.8 years for females. While women lived longer than men in both LDS and non-LDS settings, the gap between men and women in length of life was shorter among Latter-day Saints.[31] The gains in length of life for active LDS persons were initially thought to be due to adherence to the Word of Wisdom alone. However, careful examination of findings discovered that the active LDS population lived even longer than a sample of US non-smokers.[32]

Supporting this view, Merrill found that non-LDS tobacco use explains only 21 percent of the difference.[33] Clearly, other factors are at work that need to be investigated. It should be noted that Mormons typically live a more conservative sex life; tend to marry and remain married longer than the rest of the population; have more than the average number of children; go to a wide range of Church activities, including Sunday church services; fast one day a month; are encouraged to seek education and to work; and are assigned social contacts and other service activities within the Church. Many of these behaviors have been shown to be healthy in that they reduce stress and increase caring and contact. Among these are number and quality of social contacts. Studies show that people who regularly attend Church live longer. Those with more social contacts, especially social contacts that are rewarding, have much lower rates of death and disease, and they tend to have better overall health.[34]

These findings have important social consequences. The length of marriages for active Latter-day Saints is longer, more people in advanced age are still married, and years of widowhood for active Latter-day Saints are shorter. The living family has undergone reorganization because of the survival of older generations.

The family of Allan and Sharlene Orr gathered for Christmas dinner, 2015, in Orton, Alberta. Family gatherings for special occasions are an important way of reinforcing family values and provide opportunities for children to mingle with grandparents and cousins. Where multigenerational LDS families live in the same area, these kinds of gatherings, often for a family meal, may take place regularly, on a weekly or monthly basis. Living great-grandparents are also included. (Allan Orr)

The family of Allan and Sharlene Orr gathered for Christmas dinner, 2015, in Orton, Alberta. Family gatherings for special occasions are an important way of reinforcing family values and provide opportunities for children to mingle with grandparents and cousins. Where multigenerational LDS families live in the same area, these kinds of gatherings, often for a family meal, may take place regularly, on a weekly or monthly basis. Living great-grandparents are also included. (Allan Orr)

In the past, the grandparental family was the utmost a family could look forward to, and this was not always realized. Grandparents, for most younger family members, were either unknown or were distant figures known only by story or a few souvenirs. In many families today, including the majority of LDS families, grandparents are known by grandchildren and are consequently real persons, loved and able to teach and build loving relationships with the younger members of the family. A relatively recent addition to this picture is the growth of families headed by living great-grandparents. Because of their longevity, these older people are known by and may influence four generations and occasionally even more during their lifetimes.

Because large numbers of LDS persons live to old age in relatively good health, the Church has opened a wide variety of activities for older persons. They serve in temples, welfare agencies, genealogy, prisons, educational institutions, and visitors’ centers, and they have the opportunity to go on missions either near their homes or in other places. These opportunities in turn increase participants’ feelings of usefulness, enhance social contacts, and increase a sense of purpose in one’s life. These factors themselves lead to a longer and healthier life.

Roy and Kathleen Harker, from Magrath, Alberta, on a mission in Samoa in 2012. The LDS Church has a force of about eight thousand full-time senior missionaries who serve worldwide in a variety of support and technical roles. Other thousands, as part-time Church service missionaries, work from their homes as volunteers two to three days per week. Many are engaged in indexing or other family history research-related activities. (Roy Harker)

Roy and Kathleen Harker, from Magrath, Alberta, on a mission in Samoa in 2012. The LDS Church has a force of about eight thousand full-time senior missionaries who serve worldwide in a variety of support and technical roles. Other thousands, as part-time Church service missionaries, work from their homes as volunteers two to three days per week. Many are engaged in indexing or other family history research-related activities. (Roy Harker)

Education, Employment, and Mobility

The desire for learning and knowledge is deeply ingrained in Mormon theology. LDS doctrine encourages members to learn from the best books (Doctrine and Covenants 109:7), and indicates that it is impossible to be saved in ignorance (Doctrine and Covenants 131:6), that the glory of God is intelligence (Doctrine and Covenants 93:6), and that intelligence gained in this life rises with us in the Resurrection (Doctrine and Covenants 130:18).

Within three months after they arrived in June 1887, Mormon colonists in southern Alberta had established a school, which rotated among the log homes of the members.[35] Young persons were encouraged to attend available universities and qualify as teachers in order to continue the education tradition. From earliest times, both males and females were encouraged to prepare themselves for life through education. High literacy rates among males and females reflected this emphasis.

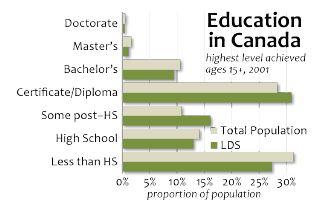

School Attendance

Over the past thirty-five years, Latter-day Saints have continually reached higher levels of educational attainment, echoing the trend for Canada as a whole. In the 2001 census, Mormons aged fifteen and over were more likely (15.1 percent) than others in Canada (11.6 percent) to be attending school both full time and part time. In the 2001 census, respondents were asked to report the highest level of education they had achieved. Among those not attending school in Canada, but aged fifteen or over, Mormons were more likely (65.7 percent) than other Canadians (62.6 percent) to have graduated from high school.

Postsecondary Education

From 1981 to 2001, the proportion of Latter-day Saints achieving at least some postsecondary education increased steadily. In 1981, 48 percent of LDS individuals took some post secondary education; in 1991, this increased to 52 percent. In 1981, 14.6 percent were awarded a university degree; by 1991 this had increased to 15.8 percent. In 2001, a larger proportion of Latter-day Saints (59.7 percent) completed at least some postsecondary education than did non-Mormons in Canada (54.6 percent). This relationship seems to hold true for all provinces and major cities.

At the highest levels of education (master’s and doctorate), Mormons have slightly lower proportions than the rest of Canadians. However, in western Canada, Mormons have approximately the same proportion earning master’s and doctorate degrees as the non-Mormon population. Mormons in the west tend to have higher levels of education than those in eastern Canada. The deficit areas for Mormon graduate study are particularly evident in eastern Canada, where a higher proportion of members join the Church as adults. Many of these adult convert members had already completed their formal education before they joined the Church.

Fields of Study

Census data are available for major field of study for those with a post-secondary education. LDS students are significantly over-represented in the health professions (15.5 percent to 11.1 percent) and in education (13.4 percent to 10.4 percent) but only marginally over-represented in agricultural, biological, nutritional and food sciences, and in fine arts. Mormons are significantly less likely to specialize in applied-science technologies and trades (19.4 percent to 21.3 percent); less likely in engineering and applied sciences (2.9 percent to 4.7 percent) and mathematics, computer and physical sciences (2.5 percent to 3.8 percent); and about the same as others in the humanities, social sciences, and business.

Church Education

A strong factor in Mormon identity in Canada is the effort to supplement public education with religious instruction. This process begins in the home and is extended through high school and the university. Instruction during school occurs typically in the morning before school, but it may take place on weekends or after school. It can occur in a home, a school, or a separate building owned by the Church. Religious instruction is offered today with students taking classes in the high school seminary program or institute classes at the post-secondary level. Research has shown that seminary and institute attendance are related to individuals forming and retaining personal relationships within the Church. These relationships in turn are powerful factors in the formation and continuation of religious belief and commitment.[36] While not strictly defined as part of their educational experience, missionary service tends to anchor young Latter-day Saints in their beliefs and practices for their post-mission lives.

Sister missionaries leaving from the Kingston Ontario Branch in December 2016, left to right, Madison Lalonde, going to the Italy Rome Mission, and Elizabeth Detlor, going to the Vancouver Canada Mission (to work in Spanish). Since the age for missionaries to serve was lowered in 2012 (from 19 to 18 for men and 21 to 19 for women), many more young women serve on missions worldwide. (Stephen Elliott)

Sister missionaries leaving from the Kingston Ontario Branch in December 2016, left to right, Madison Lalonde, going to the Italy Rome Mission, and Elizabeth Detlor, going to the Vancouver Canada Mission (to work in Spanish). Since the age for missionaries to serve was lowered in 2012 (from 19 to 18 for men and 21 to 19 for women), many more young women serve on missions worldwide. (Stephen Elliott)

Work Ethic: Independence and Cooperation

Throughout their history, Mormons have built colonies with a reasonably self-sufficient economic life and a high degree of cooperation in difficult circumstances. They have been able to do this by a strong application of their values and a willingness to employ the latest technology and organization to practical problems. The combination of independence and cooperation is unusual.[37] The Prophet Joseph Smith said somewhat facetiously that if all the Mormons were condemned to hell, they would busy themselves and create a heaven out of the place.[38] There are strong obligations placed on Mormon men and women to work hard and provide economically for themselves and for their children. Men have the first responsibility for this, but marital partners are required to help each other in their particular responsibilities as circumstances may require.[39]

Early Mormon life in southwestern Alberta was dominated by agriculture. The original colonists profited from a rich experience in the farming communities of Utah. Over time agriculture itself changed to a more modern form as technology changed and farms grew in size. In this process there was always cooperation with non-Mormons in the area.

Mormons put strong emphasis on the work ethic. During times of need, bishops may provide economic and other assistance, but it is seen as temporary. The bishop makes efforts to restore the family’s ability to support itself. Latter-day Saints are asked to contribute generously to the Church and be aware of the needs of others. Home teachers and visiting teachers, with a responsibility to visit members on at least a monthly basis, are assigned to each family and may assist families according to their needs. Beyond such formal assignments, members are taught to be generous and aware. When sickness comes, informal assistance of all kinds is often given.

The notions of self-help and family support, as well as the concepts of cooperation and mutual support, are deeply ingrained in Mormon culture. LDS employment centres exist in major cities, such as the one in Montreal shown here, which aid those seeking employment to acquire the necessary job-seeking skills. This centre often benefits from the service of a full-time senior missionary couple. (Catherine Jarvis)

The notions of self-help and family support, as well as the concepts of cooperation and mutual support, are deeply ingrained in Mormon culture. LDS employment centres exist in major cities, such as the one in Montreal shown here, which aid those seeking employment to acquire the necessary job-seeking skills. This centre often benefits from the service of a full-time senior missionary couple. (Catherine Jarvis)

The Church has employment services centers located in major cities in Canada. These locations serve both members and nonmembers of the Church. Each stake and ward has an employment specialist. These individuals identify persons with employment needs. The bishops and priesthood leaders also cooperate with these specialists and facilitate the passing of job information. At the centers there are workshops on presentation of self through verbal and written means, complete with practice interviews. Both jobs and self-employment are subjects for workshops. Workers help address special needs, such as youth entering the labour force, women reentering the world of work after periods in the home, and immigrants getting acquainted in a new country with possible needs for language and cultural instruction. They stress using computers, and they introduce patrons to the Church’s own website and job database as well as other computer resources.[40]

Labour-Force Participation and Employment

The 2001 census reports that Mormons participate in the labour force more often (67.1 percent) than non-Mormon Canadians (66.4 percent). In the year and a half before the census, significantly more Mormons had worked more (74.4 percent) than had the total population (71 percent). Correspondingly fewer Latter-day Saints were “not in the labour force” (32.9 percent) than were non-LDS Canadians (33.6 percent). Mormons were more often employed (62.2 percent) than non-LDS Canadians (61.5 percent).

The unemployment rate measures the percentage of employable people in a country’s workforce who are age sixteen or over and who have either lost their jobs or have unsuccessfully sought jobs in the last month and are still actively seeking work. They may also be unemployed if they are waiting to go back to a job. Unemployment is different than simply not working. Many persons are retired, disabled, in family work, discouraged, or not looking for work. These persons are not officially unemployed. Only 4.9 percent of Mormons were unemployed in Canada at the time of the 2001 census; at the same time, 7.4 percent of non-Mormon Canadians fit the description of unemployment. This is a major difference but may reflect in part the large number of Mormons who live in Alberta, traditionally a province with low unemployment rates. Greater LDS participation in the labour force may be due at least in part to the strong pressures to be productive and independent in the faith. The level of education among Latter-day Saints is slightly higher than that of the non-LDS population, fitting them for greater employability. Young Latter-day Saints are trained from an early age to work and to participate in earning a living, and they are encouraged to get jobs when not involved in school. Mission experiences and working in the Church are thought to increase the LDS member’s employability and ability to maintain a job.

Industries and Occupations

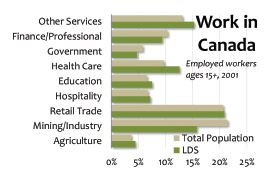

Data on industries and occupations are available for religions in the 2001 census. An “industry is the general nature of the business carried out in the establishment where the person work(s).”[41] In 2001, the pattern of work by industry shows that Mormons are overrepresented in agriculture, forestry and fishing, mining, oil and gas, retail trade, administrative support, waste management, educational services, healthcare and social assistance, arts, entertainment and recreation, and accommodation and food services. Mormons have traditionally favoured primary industry other than mining (this is an exception), education, health services, and local business. Mormons are noticeably underrepresented in construction, manufacturing, wholesale trade, finance and insurance, and public administration.

An occupation is the “kind of work performed in a job” by a worker to carry out his or her duties.[42] By the 1990s, Mormons in Canada were overrepresented in entrepreneurial, management, and professional occupations and underrepresented in unionized occupations and union leadership.[43] In 2001, occupations show some of the same pattern as industries. Mormons were overrepresented in business and finance, health, sales and service and primary industries. Mormons worked in the following occupations less than non-Mormon Canadians: management, natural and applied science, trades, transport and equipment and processing, manufacturing and utilities. Mormon prominence in health, education, sales, service, and primary industry is similar to the industry data, but prominence in business and finance is contrary to the industrial data. Mormons seem to avoid processing, manufacturing, trades, transport, and equipment. For some reason, they also avoid natural- and applied-science jobs. Mormons also are somewhat prominent in self-employment, but more so in unincorporated than incorporated self-employment. Unpaid family workers are rather uncommon in modern Canada, but Mormons are 50 percent more likely to follow this pattern than other Canadians.

LDS Movement within Canada

So far as the authors are aware, it has not been noted before that Latter-day Saints are more likely than others to move or change residence within Canada. According to the 2001 census, over half of Latter-day Saints five years of age and over (51.7 percent) have moved during the last five years. Significantly fewer (41.9 percent) of non-Mormon Canadians five years of age and over have moved. This relationship is true for interprovincial movement (6.0 percent LDS, 3.2 percent non-LDS) and intraprovincial movers (16.5 percent LDS, 12.8 percent non-LDS).

The reason for the large number of LDS movers is not clear. Three possible factors may be at work. First, moving and travelling from place to place may well be an ingrained part of the Mormon heritage. Part of Mormon heritage is associated with the migration of peoples: the early Saints’ move west to Utah, their subsequent gathering to Zion, and, in Alberta’s case, the trek of nearly seven hundred miles from Utah to southern Alberta. Mormon missionaries have routinely travelled to faraway places to serve missions, and university students have routinely travelled for educational reasons. Such experience may break down some of the inherent fears associated with uprooting and relocation.

Second, those who move in Canada often do this for education and for better conditions of work. It may be that Latter-day Saints are more likely to be seeking education and better work than others. Supporting this idea is the higher percentage of Latter-day Saints with postsecondary education and the higher proportion of Latter-day Saints who are working at jobs. Their extra children could be a driver as well. Having more children is a motivation to earn more money to meet the extra expenses.

Austin Doig, of Magrath, Alberta, cheerfully fulfills his duty as a home teacher by helping one of his families move. Home teachers visit the homes of members monthly to attend to their spiritual and temporal needs. Helping families move provides an opportunity for service. Many elders quorums routinely help members move, while women of the Relief Society typically provide other services, such as helping pack and unpack and childcare. (Patricia Whitehead)

Austin Doig, of Magrath, Alberta, cheerfully fulfills his duty as a home teacher by helping one of his families move. Home teachers visit the homes of members monthly to attend to their spiritual and temporal needs. Helping families move provides an opportunity for service. Many elders quorums routinely help members move, while women of the Relief Society typically provide other services, such as helping pack and unpack and childcare. (Patricia Whitehead)

Third, wherever Latter-day Saints move, they find a ready-made community of fellow believers—people with a similar worldview, similar lifestyle, and similar will to help new families adjust to their community. LDS movers may even have family members at the new location. Latter-day Saints tend to have large, extended families, and leaders keep track of their flocks. The men in elders quorums typically help load and unload moving trucks at the points of departure and arrival, and the women of the Relief Society often help with packing, unpacking, caring for children, and providing other support. These factors reduce the costs of moving, considering both economic cost and psychological stress.

Conclusions

In this study of official statistics as they apply to Latter-day Saints, we have discovered that Mormons are objectively different from non-Mormons in Canada. They follow trends present in the larger society but remain different in ways suggested by their doctrine. They have a distinctive way of life. This does not suggest they are uniformly observant of their rules, but it does suggest that Mormons live in a way that is influenced by their ethnos or culture. In this regard they are an ethnoreligious people.[44]

Mormon differences are really a matter of emphasis and degree. Mormons share in most basic human activities. They marry and have children. Their children are not uniformly obedient but, as with all children, require every possible effort to achieve a successful outcome. Mormons strive for achievement and education. They care for each other and often act in charitable ways toward others not of their own faith. Some observers say that Mormons have less of a life because of religious restrictions placed on them. Some of these restrictions are related to diet, sexuality, large amounts of time for service, and money given as donations. Many Mormons view these same restrictions and say that they do not feel limited but actually have more of life. They live longer, tend to have good health, have larger families, and have fewer divorces. They are somewhat more educated and are usually gainfully employed. From youth they are taught to serve and give of their substance. They have faith that their style of living will produce greater happiness in this life and will positively impact their life after death as well.

Notes

[1] Tim B. Heaton, “Vital Statistics,” in Latter-day Saint Social Life: Social Research on the LDS Church and Its Members (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1998), 105–32; Ray M. Merrill, “Life Expectancy among LDS and Non-LDS in Utah,” Demographic Research 10, no. 3 (2004): 61–82; James E. Enstrom and Lester Breslow, “Lifestyle and Reduced Mortality among Active California Mormons, 1980–2004,” Preventative Medicine 46 (2008): 133–36.

[2] “Religion,” Statistics Canada, Census Program: National Household Survey Dictionary, 2011, https://

[3] Carl Bialik, “Elusive Numbers: U.S. Population by Religion,” Wall Street Journal, 13 August 2010, http://

[4] “Canada’s Changing Religious Landscape,” Pew Research Center, 2013, http://

[5] The 2011 Household Survey sample does not provide data to the public on smaller religions such as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, although such data may be purchased from Statistics Canada. We received assistance from the Data Liberation Initiative, a program of Statistics Canada that allows more detailed data to be released through local representatives to qualified researchers. We are grateful to Dr. Chuck Humphrey of the University of Alberta for providing these materials.

[6] Hannah Jackson, “The Long-Form Census Is Back, It’s Online—And This Time, It’s Mandatory,” CBC News, Politics, last updated 2 May 2016, http://

[7] Deseret News, Deseret News 2003 Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 2003), 298.

[8] Dean Perkins, Member and Statistical Records Division, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, email to Stephen V. Beck, Country Profile Manager, Church History Library, 28 March 2016.

[9] See Daniel K. Olsen, Brandon S. Plewe, and Jonathan A. Jarvis, “Growth, Distribution, and Ethnicity,” herein.

[10] “Canada Goes Urban,” Statistics Canada, 2016, http://

[11] Census of Canada, Profile of Income of Individuals, Families and Households, Social and Economic Characteristics of Individuals, Families and Households, Housing Costs, and Religion, for Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Divisions and Census Subdivisions, 2001, Catalogue #95F0492XCB2001001.

[12] “Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity in Canada,” Statistics Canada, 2013, National Household Survey, 2011, http://

[13] Robert D. Putnam and David E. Campbell, American Grace (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010), 137.

[14] Christian Smith, Melinda Lundquist Denton, Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 35–54, 72–74, 222–24.

[15] Brigham Y. Card, “Mormons,” in The Encyclopedia of Canada’s Peoples (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), 989.

[16] Jessie L. Embry, “Exiles for the Principle: LDS Polygamy in Canada,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 18 (1985): 112–13; Jessie L. Embry, “Transplanted Utah: Mormon Communities in Alberta,” Oral History Forum (Forum d’histoire orale) 18 (1998): 68–69.

[17] George K. Jarvis, “Demographic Characteristics of the Mormon in Canada,” in The Mormon Presence in Canada, ed. Brigham Y. Card and others, (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1990), 296.

[18] Unless otherwise indicated, this and following statistics are from the 2001 Canadian census.

[19] A less conservative measure of Canadian family structures found that by 2011, 16.7 percent of Canadian families were living in common-law relationships. (Table 1, Distribution (Number and Percentage) and Percentage Change of Census Families by Family Structure, Canada, 2001 to 2011,” Statistics Canada, 2015. http://

[20] Brigham Y. Card, “Mormons,” in Encyclopedia of Canada’s Peoples, 989.

[21] Doctrine and Covenants 89.

[22] “Word of Wisdom History and Implementation,” Fair Mormon Answers, http://

[23] Gordon B. Hinckley, “The Scourge of Illicit Drugs,” Ensign, November 1989, https://

[24] James E. Enstrom, “Cancer Mortality among Mormons,” Cancer 36, no. 3 (1975): 825–41; James E. Enstrom, “Cancer and Total Mortality among Active Mormons,” Cancer 42 (1978): 1943–51; George K. Jarvis, “Mormon Mortality Rates in Canada” Social Biology (1977): 294–302.

[25] Joseph L. Lyon, Melville R. Klauber, John W. Gardner, and Charles R. Smart, “Cancer Incidence in Mormons and Non-Mormons in Utah, 1966–1970.” New England Journal of Medicine 294 (1976): 129–33; Joseph L. Lyon, John W. Gardner, and Melvin R. Klauber, “Low Cancer Incidence and Mortality in Utah,” Cancer 39 (1977): 1608.

[26] Jarvis, “Mormon Mortality Rates in Canada,” 294–302.

[27] James E. Enstrom and Lester Breslow, “Lifestyle and Reduced Mortality among Active California Mormons, 1980–2004,” Preventative Medicine 46 (2008): 133–36.

[28] Jarvis, “Mormon Mortality Rates in Canada,” 294–302.

[29] Because no recent studies have examined this in Canada, we rely on recent US data.

[30] Ray M. Merrill, “Life Expectancy among LDS and Non-LDS in Utah,” Demographic Research 10, no. 3 (2004): 61–82.

[31] For those alive at age eighty, the remaining years of life expected were 8.2 for LDS males, 6.5 for non-LDS males, 10.3 for LDS females, and 7.1 for non-LDS females. Older LDS females have a longer life ahead than LDS males; they also have a longer life than non-LDS females. Ibid.

[32] James E. Enstrom, and Frank H. Godley, “Cancer Mortality among a Representative Sample of Nonsmokers in the United States during 1966–68.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute 65, no. 5 (1980): 1175–83, 1980.

[33] Ray M. Merrill, “Life Expectancy among LDS and Non-LDS in Utah,” Demographic Research 10, no. 3 (2004): 61–82.

[34] Julianne Holt-Lunstad, Timothy B. Smith, J. Bradley Layton, “Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-Analytic Review,” PLoS Medicine 7, no. 7 (2010): e1000316, doi: 10.1371/

[35] Brigham Y. Card, “Mormons,” in Encyclopedia of Canada’s Peoples, 992.

[36] Marie Cornwall, “The Social Bases of Religion: A Study of Factors Influencing Religious Belief and Commitment,” Review of Religious Research 29 (1987): 44–56.

[37] Brigham Y. Card, “Mormons,” in Encyclopedia of Canada’s Peoples , 985.

[38] History, 1838–1856, volume E-1 [1 July 1843–30 April 1844], The Joseph Smith Papers, http://

[39] “The Family: A Proclamation to the World,” Ensign, November 2010, 129.

[40] Personal Knowledge of George K. Jarvis, who with his wife, Kathryn, served as a full-time missionaries at the Montreal Employment Service Centre. Called in 2012, the couple served as directors of the LDS Employment Resource Center for the region.

[41] “Occupation of Employed Person,” Statistics Canada, 2016, http://

[42] “Occupation of Employed Person,” Statistics Canada, 2016, http://

[43] Brigham Y. Card, “Mormons,” in Encyclopedia of Canada’s Peoples, 986.

[44] David E. Campbell, John C. Green, and J. Quin Monson, Seeking the Promised Land: Mormons and American Politics (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 39, 42.