Crossing the 49th Parallel

Community, Culture, and Church in the Canadian Environment

Rebecca J. Doig and Daniel H. Olsen

Rebecca J. Doig and Daniel H. Olsen, “Crossing the 49th Parallel: Community, Culture, and Church in the Canadian Environment,” in Canadian Mormons: History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Canada, ed. Roy A. and Carma T. Prete (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 144-177.

Mormon settlers crossing northward into Canada faced a new land, with different laws, culture, and climate. As they made their homes in southern Alberta, they adapted their traditions to create a uniquely Canadian Mormon identity. Today’s traveller confronts a wholly different world. How Latter-day Saints adapted to the Canadian environment is the subject of this chapter. (Darrel Nelson)

Mormon settlers crossing northward into Canada faced a new land, with different laws, culture, and climate. As they made their homes in southern Alberta, they adapted their traditions to create a uniquely Canadian Mormon identity. Today’s traveller confronts a wholly different world. How Latter-day Saints adapted to the Canadian environment is the subject of this chapter. (Darrel Nelson)

When Charles Ora Card and the first company of Mormon settlers crossed the border into Canada in 1887, they “halted and gave three cheers for [their] liberty as exiles for [their] religion.”[1] These Mormon settlers had high hopes for Canada. Church President John Taylor had counselled Card to seek refuge in Canada, observing, “I have always found justice under the British flag.”[2] Much like the Aboriginal peoples of the day who believed that by crossing the US-Canadian border they were crossing a “medicine line,” Mormons hoped that north of the border they would find a safe haven where they could continue their religious beliefs and practices without harassment.[3] But the desire to re-create their unique society in this new land north of the 49th parallel not only involved the immediate challenges of adapting to a New physical, social, and political environment, but had long term consequences in terms of establishing a new church in a new land with differing political traditions.

Political borders act as psychological and physical barriers to the movement of people, goods, services, cultural ideas, and values. Yet, as one expert has pointed out, the US–Canadian border has long displayed “variability in its role as an inhibitor.”[4] As the longest unmilitarized border in the world, the US-Canadian border has acted as a semipermeable barrier rather than an absolute barrier between the two countries. At different points along the length of the border and at different times in the history, cross-border movement has occurred with varying levels of intensity. The US-Canadian border has been a major factor in determining the differing cultural, economic, and political trajectories of Mormon settlements on either side of it.

This chapter will explore the extent to which Mormon settlers crossing the border from the United States into Canada were successful in recreating a typical Utah community in southern Alberta and how their pattern of living enriched Canadian life. It will evaluate the ways in which they were forced to adapt to the unique political, legal, social, and climatic environment in Canada. It will assess the degree to which southern Alberta Latter-day Saint culture in its early decades was enhanced and transformed by ongoing interactions with LDS culture in the United States. This chapter will also address the extent to which southern Alberta culture was able to spread throughout the rest of Canada and what new ideas emerged as the Church grew across the country and as Latter-day Saints had to deal with the challenges that they faced in an environment where they were in the minority. The study will consider the changes that came to LDS culture in Canada from the 1960s to the 1990s as the Church began to globalize, simplify, and refocus its programs, and drop its American cultural bias. It will assess the impact of the growing Canadian ethnic diversity on Mormon culture and the extent to which there has emerged a distinctive Canadian-Mormon culture and identity in the twenty-first century. At the same time, this chapter will reflect on the political culture of Canadian Mormons, the functioning of the Church as an institution within the Canadian legal framework, and the problems related to cross-border movements of people and commodities. These are issues which Card could have hardly imagined as he found a new home for his coreligionists in this northern refuge.

As Church President John Taylor predicted, Mormons arriving in Alberta in the 1880s were treated fairly by the Canadian government. (Darrel Nelson)

As Church President John Taylor predicted, Mormons arriving in Alberta in the 1880s were treated fairly by the Canadian government. (Darrel Nelson)

Establishment of a Distinct Mormon Community in Southern Alberta

Adjusting to Canadian Laws: The Presence of the North-West Mounted Police

While the southern Alberta settlements were similar to other LDS settlements in the American Intermountain West, the border was an important factor, right from the beginning, making the Alberta communities distinct from their American counterparts. When Mormons arrived in Utah, they were beyond the frontiers of the United States, and thus Church leaders hoped that they could practice their faith without outside interference. Conflict came later as the United States extended territorial control throughout Utah and imposed laws banning the practice of polygamy. In contrast, it is significant that when the first Mormon settlers arrived in Canada, the law, enforced by the North-West Mounted Police (later renamed the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, or RCMP), was already established and had a strong presence in southern Alberta. This was a significant Canadianizing influence on the Mormon settlers and ensured that they obeyed the laws of their new homeland.

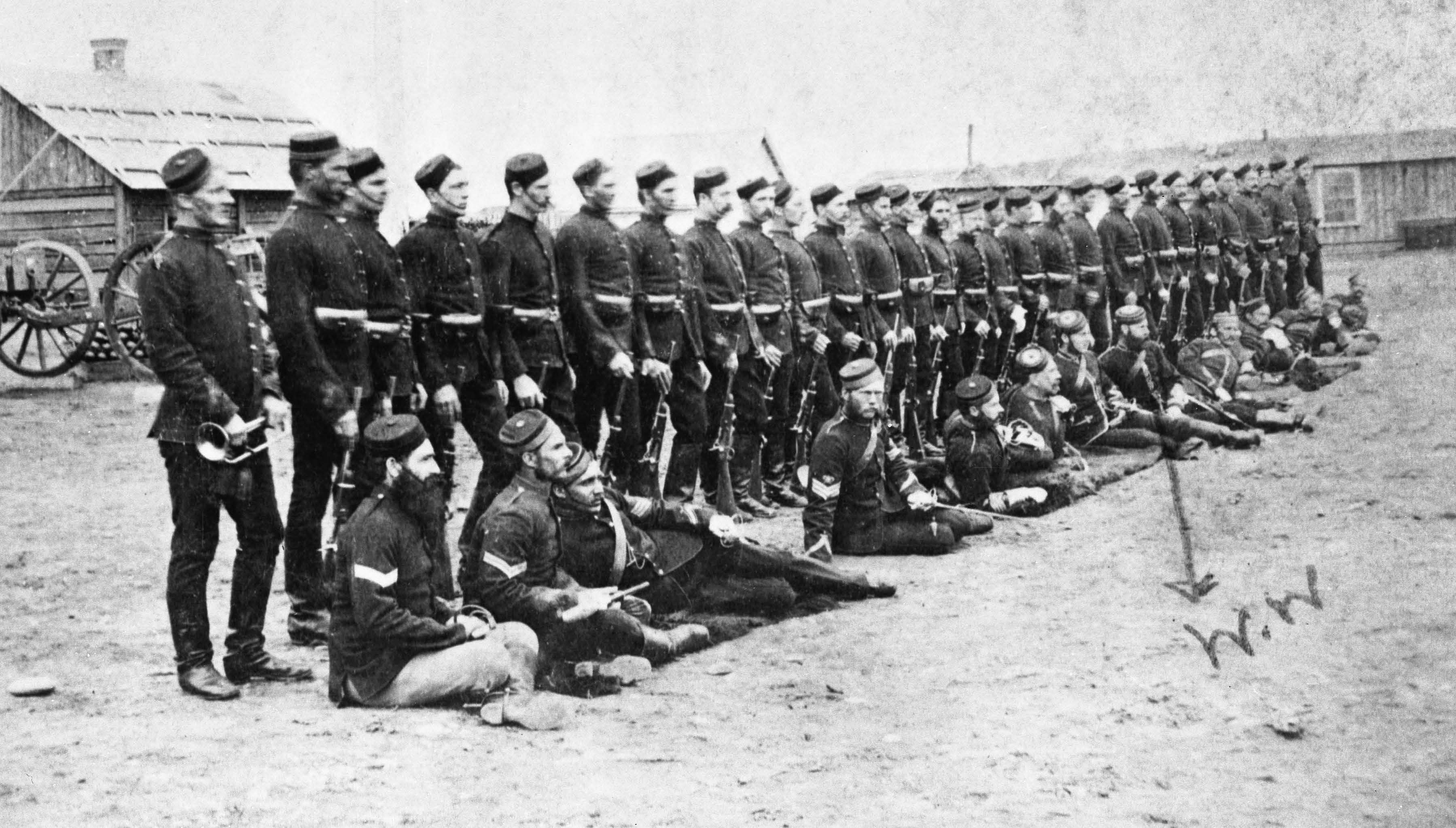

C Troop of the North-West Mounted Police at Fort Macleod, 1879. The North-West Mounted Police was established in 1873 and had established a fort at Fort Macleod by 1874. Hence, they were well established in southern Alberta before the arrival of the first Mormon settlers in 1887. (Glenbow Archives NA-98-18)

C Troop of the North-West Mounted Police at Fort Macleod, 1879. The North-West Mounted Police was established in 1873 and had established a fort at Fort Macleod by 1874. Hence, they were well established in southern Alberta before the arrival of the first Mormon settlers in 1887. (Glenbow Archives NA-98-18)

Embracing a New Homeland: Early Mormon Patriotism in Canada

Mormon settlers in Alberta were conscious of being in a different country and made efforts to embrace their new homeland. Card and other Church leaders encouraged the Saints to take out Canadian citizenship.[5] Church leaders also made efforts to demonstrate loyalty to their new homeland, initiating elaborate Dominion Day celebrations at Lee Creek on 1 July 1887, a few weeks after their arrival, complete with a picnic, speeches, singing, foot and horse racing, jumping, and a parade. Nearby Blood Tribe members, local ranchers, and NWMP were invited to attend.[6] In later years, similar celebrations were extended to Raymond, Magrath, and other Mormon communities as they were established.

The ways in which the Mormons celebrated Dominion Day, however, were more similar to a 4th of July celebration than to Dominion Day observances of the time.[7] Their rousing American-style celebrations seemed rather odd to their neighbours, who typically observed the holiday as a day of “popular leisure and recreation” rather than a day of “patriotic ceremonial and public rejoicing.”[8] In his history of the North-West Mounted Police, R. C. Macleod commented that the Mormons’ enthusiastic display every 1 July was curious, “since instead of making the Latter Day Saints less conspicuous it only made them more so. Canadians generally tended to be undemonstrative on the occasion.”[9]

Bishop Levi Harker of Magrath encouraged the Saints in Magrath to be patriotic Canadians. He erected a giant flagpole with the Union Jack atop. Liberty poles like this were popular in the United States at that time but not common in Canada. Harker is shown at the top of the pole with men below preparing dynamite to explode between two anvils to announce the beginning of a celebration day.[10] (Magrath Museum)

Bishop Levi Harker of Magrath encouraged the Saints in Magrath to be patriotic Canadians. He erected a giant flagpole with the Union Jack atop. Liberty poles like this were popular in the United States at that time but not common in Canada. Harker is shown at the top of the pole with men below preparing dynamite to explode between two anvils to announce the beginning of a celebration day.[10] (Magrath Museum)

Adapting to the Canadian Climate

The first party of settlers who crossed into Canada on 1 June 1887 woke up to four inches of snow the next morning.[11] This was a forceful reminder that they were not in Utah anymore and that the Canadian climate would pose new challenges for the Saints. Nonetheless, as Card noted, they planted wheat, oats, and alfalfa in the first year. The seeds “came up in a luxuriant manner” and the “soil [was] quick and productive.”[12] Most years, crops were grown successfully, and Mormons were important in establishing new agricultural practices in southern Alberta. They were instrumental in proving that wheat, including spring wheat, could be successfully grown on the prairies. They also introduced alfalfa and were early proponents of sheep farming,[13] as well as pioneering farm-related industry including flour mills, sugar beet factories, creameries, and cheese factories. Over the years, experimentation by Mormons, as well as government-owned experimental and model farms, led to improved farming techniques and greater yields. Sugar beets, introduced into southern Alberta thanks to the investment of LDS businessman and philanthropist Jesse Knight in 1901, were a unique LDS innovation.[14]

With regard to climate, as one scholar on Alberta settlement patterns has observed, “Far more important than the climatic norms in southern Alberta, were the extremes of climatic variability.”[15] Hurricane-force winds, spring snow storms, flooding, dry summers, early frosts, and long, harsh winters were and continue to be among the severe conditions that have sometimes led to crop failures and losses of livestock. Many Mormon settlers eventually returned to Utah after having had enough of the Canadian climate.[16] For those who stayed, the volatility of the weather frequently brought the Saints to prayer and fasting and reliance on the Lord for help (see chapters 3 and 8).

One thing Utah Mormons were accustomed to before coming to Canada was a shortage of water. Mormons had experience with extensive irrigation projects in the intermountain United States and could see the agricultural potential of land in the arid Palliser Triangle, which others could not.[17] Mormons began successful experiments with irrigation shortly after founding Cardston.[18] This laid the groundwork for an unprecedented economic agreement between Elliott Galt and Charles A. Magrath and the Mormons (see chapter 3), which led to the building of an irrigation canal from Kimball to Stirling, with a branch line to Lethbridge.[19] The building of this canal led to a large influx of additional Mormon settlers from Utah to southern Alberta beginning in 1899 and led to the founding of the towns of Magrath and Stirling. In 1901, the community of Raymond was built along the canal as well. Bringing irrigation to southern Alberta must number among one of the most important Mormon contributions to Canada.

Plat of Zion and Agricultural Villages

One of the key goals of early Mormon pioneers in Alberta was to recreate the sense of community they had enjoyed in intermountain settlements in the United States. These settlements were agricultural villages inspired by Joseph Smith’s model community called the Plat of Zion. This settlement model included wide streets oriented to the cardinal compass points, residential lots large enough for family gardens but small enough to foster a feeling of community, and a centralized location for church, educational, and civic buildings. Farmers lived in the village and travelled outside the community to work on their farmland, while workers in local industry, merchants, educators, and others also lived in the village proper.[20] The benefits of close-knit community life and religious observance could thus be maintained in an agricultural setting.

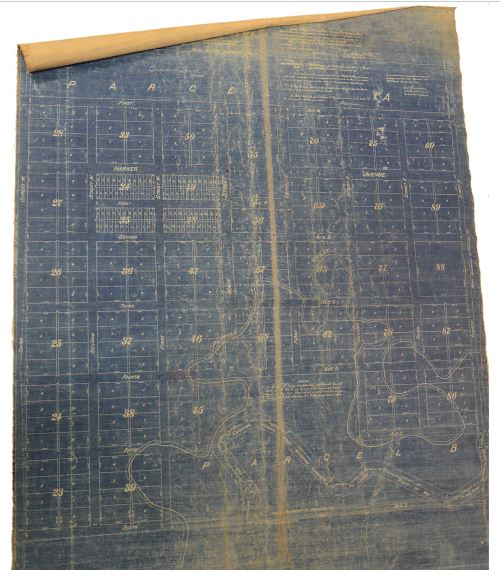

This map shows the town of Magrath one-mile square divided into ten-acre blocks with eight 1.25-acre lots per block. Central blocks were set aside for schools, a church, and businesses. Lots were big enough that families could plant trees and shrubs, have a large garden, and keep chickens and a dairy cow or two on their lot, but small enough that residents enjoyed close associations with their neighbours and community. Though not identical, most Mormon settlements in southern Alberta were designed in a similar way. (Magrath Museum)

This map shows the town of Magrath one-mile square divided into ten-acre blocks with eight 1.25-acre lots per block. Central blocks were set aside for schools, a church, and businesses. Lots were big enough that families could plant trees and shrubs, have a large garden, and keep chickens and a dairy cow or two on their lot, but small enough that residents enjoyed close associations with their neighbours and community. Though not identical, most Mormon settlements in southern Alberta were designed in a similar way. (Magrath Museum)

However, there were obstacles to duplicating this settlement pattern in southern Alberta. Unlike the Mormons in Utah who were able to impose their settlement pattern on an unsettled land, the Mormon settlers in southern Alberta were bound by the 1872 Dominion Land Act, which set the size and location of homesteads, the location of roads, and the distribution of farms. In essence, this act mandated “highly dispersed, low density settlement patterns” across western Canada.[21] As such, the formula through which the Dominion Land Act organized the settlement of southern Alberta was one “that prescribed a lonely and isolated existence for immigrant homesteaders.”[22]

In the 1888 visit to Ottawa, Card and his associates asked to buy land from the Canadian government to allow for their distinctive community settlement pattern. Though they were allowed to purchase a half section of land for the Cardston townsite, they were not granted any other exceptions to the Dominion Land Act.[23] Card soon found another way to get land. Within a few days of his return from Ottawa, he approached Charles A. Magrath, land agent for the Northwest Coal and Navigation Company.[24] The company had received massive land grants for building the railway from Dunmore, near Medicine Hat, to Lethbridge. Card’s visit with Magrath initiated a productive relationship, which resulted in many Mormon communities being built on railway lands.

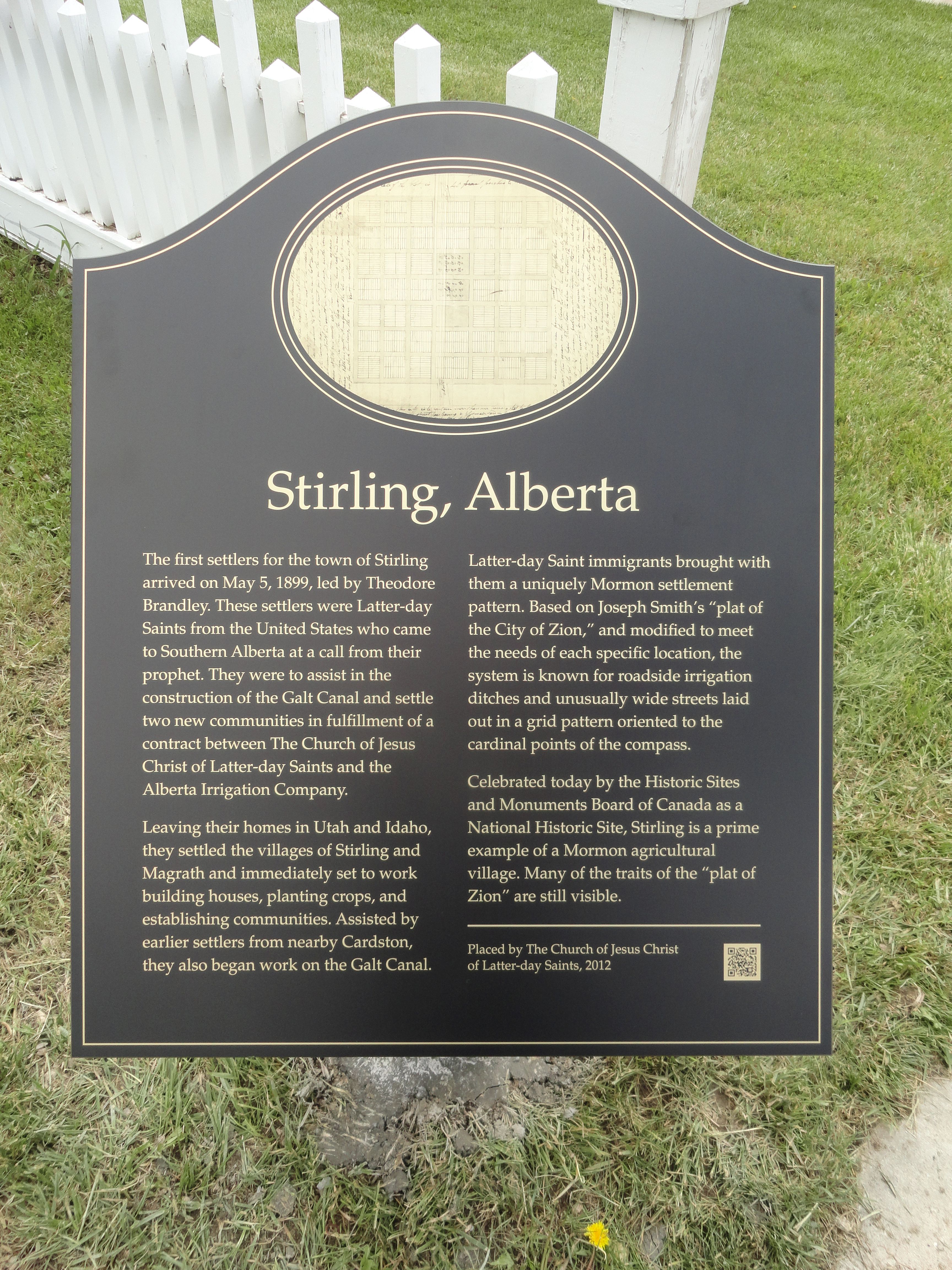

Thus, thanks to the tenacity of Charles O. Card in overcoming obstacles, southern Alberta Mormon settlements were set up as agricultural villages after all. The style of community living established in southern Alberta was similar to that of Mormon settlements in the United States and very different from the solitary homestead life that was characteristic of the farming population of Canadian prairies. In recognition of how distinctive Mormon agricultural villages are in the Canadian landscape, in 2001, the Government of Canada chose Stirling, Alberta—the best-preserved example of a Mormon agricultural village—as one of three communities in Canada to be designated a National Historic Site.[25]

Below, Stirling historic marker; above, the Michelson home, an original historic home with some modern additions. Mormon settlers in southern Alberta, for the most part, settled in agricultural villages, rather than on isolated homesteads, which enabled them to maintain strong Church and community participation. Stirling has been designated as a National Historic Site. (Gary Boatright)

Below, Stirling historic marker; above, the Michelson home, an original historic home with some modern additions. Mormon settlers in southern Alberta, for the most part, settled in agricultural villages, rather than on isolated homesteads, which enabled them to maintain strong Church and community participation. Stirling has been designated as a National Historic Site. (Gary Boatright)

Resolving the Issue of Polygamy

A major casualty in the Mormon desire to re-create the culture of their previous mountain home was the discontinuation of the practice of polygamy in Canada. In a meeting in 1888 with Canadian Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, Card, accompanied by Mormon Apostles Francis M. Lyman and John W. Taylor, asked the prime minister if the Mormons could be allowed to bring their plural wives to Canada.[26] The request was categorically denied. Card promised Macdonald that the Mormons would not bring the practice of plural marriage into Canada.[27] This promise he kept, effectively barring the practice of plural marriage among Alberta Mormons. While several early Mormon settlers had a wife in Canada and additional wives in the United States, including some who married additional wives after coming to Canada, the practice of keeping two or more wives in Alberta was virtually nonexistent (see chapter 3).[28] Card and those who came with him to Canada to escape proscription for the practice of polygamy, in effect, had to abandon the practice to remain good citizens in this new land of liberty.

Community Building: Rodeos, Sports, and Cultural Arts

At the time southern Alberta was settled, the Church had a very strong community focus—an emphasis on building Zion communities—that matched their settlement pattern and was a particular feature of this period in Church history. In the early years of Mormon settlement in Alberta, as was the case in American Mormon settlements at the time, there was very little distinction between church and community. In fact, in the first several decades of LDS settlement in Alberta, the Church was involved very directly in organizing the settlements and in community building. Early Church leaders such as Charles Ora Card, E. J. Wood, Levi Harker, Theodore Brandley, and Heber S. Allen purchased land, directed the settlement of communities, expanded irrigation, established local industries and schools, performed judicial functions, provided counsel on farming techniques, and in other ways directed community life.[29]

In the first decades after settlement in Alberta, the LDS Church was not only involved in community building in terms of geographical organization, industry, and employment, but also committed to providing opportunities for Church members to develop the “whole person” through the promotion of education, recreation, cultural arts, sports, homemaking arts, and more.[30] In 1902 Joseph F. Smith taught, “The Church is provided with so many priesthood organizations that only those can be recognized. . . . No outside organization is necessary.”[31] Similarly, in 1932 President Heber J. Grant taught, "I am grateful that no Latter-day Saint upon the face of the earth needs to go anywhere outside the Church to solve any problem whatever, moral, intellectual, physical, mental [or] spiritual."[32] In the twenty-first century, it may seem strange that the Church assumed such a broad role in community life. However, this was a time when the vast majority of Church members lived in predominantly LDS communities, and when many of these were farming villages which were too small and isolated to provide, without Church support, the cultural, sporting, and educational opportunities available in larger centres. Therefore, it was fitting and extremely beneficial to Church members that the Church stepped in to fill these roles.

This holistic thinking fit in with the progressive movement in the United States that occurred in the late 1800s and early 1900s. During this time, the Young Men Christian Association (YMCA) movement was emerging, and many religious denominations were espousing the concept of “muscular Christianity.” According to this viewpoint, a religion was concerned with developing individuals with not only strong spirits but also strong minds and bodies.[33] According to historian Richard Ian Kimball, the LDS Church espoused its own version of this thinking. From the 1890s onward, the church developed expansive recreation, cultural, and sporting programs governed primarily through the Young Men and Young Women Mutual Improvement Associations, which aimed to “communicate Mormon morals, attitudes and expectations. As an instrument of social persuasion—a method of teaching proper behavior—recreation programs instructed adolescents in what it meant to be Mormon.”[34]

Thus, when the Saints came to southern Alberta, they brought with them “a tradition of play and recreation” that was compatible with their religion.[35] Horse racing, athletic competitions, and footracing were favourite pastimes of the Mormon settlers. Over time, a number of sporting and cultural activities were imported to southern Alberta from Utah.

Rodeo was an LDS import into southern Alberta in 1902 (see sidebar), and the sport continues to be popular among southern Alberta farming and ranching families to this day. Football has also been much more popular in southern Alberta than in other places in Canada. Raymond has been termed “the football factory of Raymond, Alberta”[36] by Canadian sports broadcasters and journalists because the town has produced multiple Canadian Football League players over the years. Between 1985, when high school provincial football championships were first awarded, and 2015, Raymond won ten provincial championships and Cardston won five.[37]

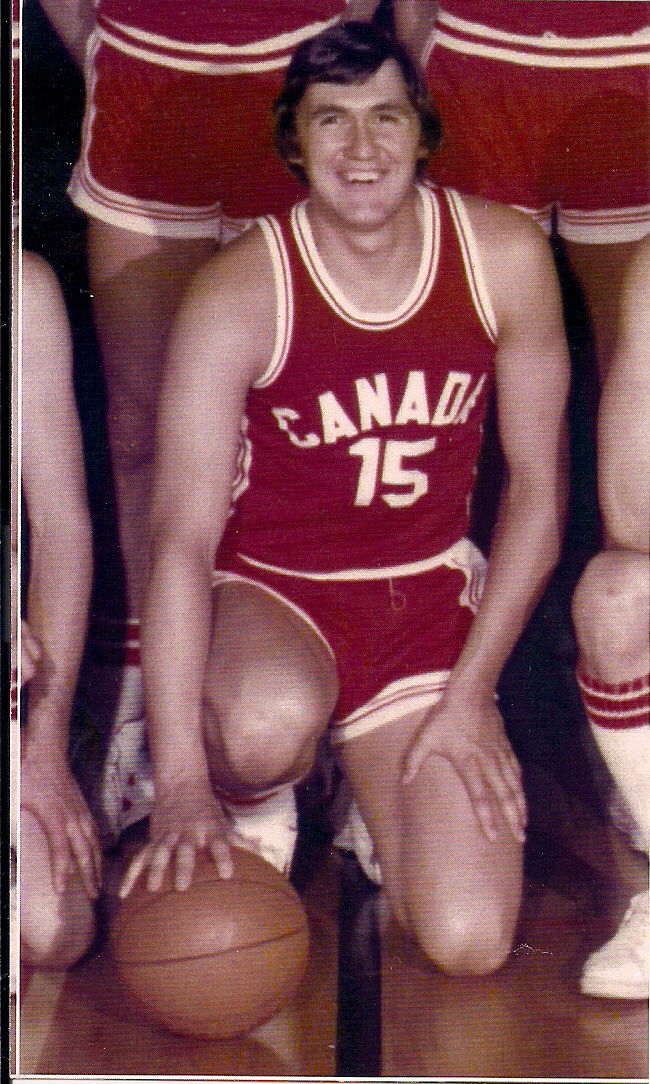

Basketball is the most popular sport among southern Alberta Mormons. Invented by Canadian James Naismith in 1891, basketball was brought to Salt Lake with the introduction of the YMCA about 1893. Basketball became popular in Utah in the 1890s, and was introduced into southern Alberta by the Saints who built the irrigation canals. In fact, Stirling claims to have been the first place in Canada to form a basketball team in April 1903,[42] and Raymond had the first high school boys’ basketball team in Western Canada later that year.[43] Teams also sprang up in Cardston and Magrath, with girls’ teams being established in tandem with boys’ teams. Games were initially played outdoors until indoor facilities were built.[44]

The Pothole Mollies, representing the portion of Magrath south of Pothole Creek, played against Cardston “for the basketball championship of the world, and no fault of theirs if the world doesn’t know it,” in front of a large outdoor audience in Lethbridge in 1905. The Mollies won and each girl received a C$5 gold coin from Charles A. Magrath. (Magrath Museum)

The Pothole Mollies, representing the portion of Magrath south of Pothole Creek, played against Cardston “for the basketball championship of the world, and no fault of theirs if the world doesn’t know it,” in front of a large outdoor audience in Lethbridge in 1905. The Mollies won and each girl received a C$5 gold coin from Charles A. Magrath. (Magrath Museum)

Basketball has been a major element of southern Alberta sporting culture, and in particular southern Alberta Mormon culture, and many basketball teams from the region have been successful at various levels of play. For example, the Raymond Union Jacks won the first ever Canadian Men’s National Basketball Championship in 1924 and also won fifteen provincial titles between 1921 and 1941.[45] Today, each southern Alberta LDS town big enough to have a high school boasts a beautiful school gymnasium with extra seating paid for by community fund-raising.[46]

The basketball culture in southern Alberta high schools in predominately LDS communities has drawn media attention, including articles in Maclean’s magazine and the Calgary Herald. Among the phenomena noted are: the ability of these small schools to compete effectively year after year against schools sometimes ten times as large; the vastly disproportionate number of provincial championships won by these communities; the incredible community support and high attendance at games; the outstanding players who have come out of these programs; and the multigenerational support for the game, including small children aspiring to one day represent their school and their town.[47]

Baseball was unique in that it was popular in southern Alberta from its very beginnings among Church members and non-Church members alike. The 1891 Lethbridge News reported baseball competitions between Lethbridge and Great Falls.[48] While baseball was also popular among LDS settlers, it appears they did not begin playing against Lethbridge and Fort Macleod until 1897.[49] Other sports such as Lacrosse, which were popular in Lethbridge, did not seem to take root among the Latter-day Saint settlers.[50] While there are now ice arenas in Cardston, Magrath, and Raymond, and some LDS youth do play hockey, it is not the dominant sport in these communities like it is in other small towns in Canada. The cultural dominance of basketball and the universality of Sunday play are deterrents to playing hockey for many southern Alberta LDS families.[51]

The Church itself fostered sports through Church-wide tournaments in basketball, baseball, and other sports. These tournaments were held annually from the 1920s until 1972.[52] The objectives of these recreational programs went beyond athletics. Excellence in the actual sport was combined with emphasis on sportsmanship and adherence to Church standards, and to be eligible to play, church attendance and abstinence from alcohol and tobacco were required.[53] Tournaments also included devotionals and other faith-centred meetings and cultural events. In order to accommodate the Church’s athletic programs and cultural activities, Church buildings in southern Alberta have always provided space for sports and recreation. In the early days, this even took the form of the pews being removed during the week, to allow for basketball to be played in the chapel.[54] Later on, cultural halls (gymnasiums) became standard for Church buildings.

Church leaders in the Taylor Stake went a step further. In the 1940s, stake president James Walker had a vision of an ambitious recreation complex to allow stake members, particularly youth, to remain physically and spiritually active through the long Alberta winters. He finally persuaded Church President David O. McKay, arguing, “President, when you called me as a stake president, you charged me with saving the boys, and I need this building to do that.”[55] This one-of-a-kind structure (minus President Walker’s proposed basement bowling alley and banquet room) was completed in 1955 and was eventually joined with the adjacent stake centre in 1975.[56] This beautiful gymnasium still exists and boasts such extensive seating that until recently many Raymond high school basketball games were played there.[57]

The cultural hall of the Taylor Stake in Raymond, completed in 1955, included extensive spectator seating that demonstrated the community’s high priority on sports and recreation. (Glenbow Archives NA-4510-132)

The cultural hall of the Taylor Stake in Raymond, completed in 1955, included extensive spectator seating that demonstrated the community’s high priority on sports and recreation. (Glenbow Archives NA-4510-132)

Music, Dance and Drama

Sports were not the only cultural elements brought from Utah and adapted to southern Alberta church culture. Mormon settlers awarded a high priority to music, dancing, and drama. In 1902, cash-strapped Magrath residents voted to reject a motion to spend three hundred dollars to build a bridge over Pothole Creek to unite the two halves of the town, but were successful in raising three hundred dollars in subscriptions to allow for the creation of the brass band.[58] The first play was performed in Magrath in 1900, only one year after the settlement was founded and before many residents even had proper homes.[59] In 1904 some LDS homesteaders in Taber who had migrated from Hooper, Utah, having just completed their homes, combined all their family tents and put them up over a temporary floor creating a “tent hall” for dances and entertainment.[60]

In 1909, the Raymond Opera House, complete with a large stage, balcony, and spring loaded and optionally tilting floor, was opened. The opera house was such a grand venue that, in addition to hosting local plays, dances, and concerts, it attracted well-known travelling theatre companies and musicians.[61] The opera house was a community venture, but received support from the Church. A Raymond ward Relief Society president, Irene Redd, recalled the struggle she experienced when her bishop asked her to sell the wheat the Relief Society has been storing in case of tough times to buy shares in the opera house. Though she agonized over the decision, she followed her bishop’s request.[62] A significant portion of the cultural arts tradition of southern Alberta was officially promoted by the Church itself, with the Church sponsoring one-act play contests and with many wards sponsoring one three-act play and several one-act plays each year.[63] Orchestras, choirs, bands, and theatre, including musical theatre, have all been significant components of southern Alberta Mormon communities ever since, although sometimes overshadowed by sports. In Cardston, the well-renowned Carriage House Summer Theatre attracts a full house every night all summer long, and each town also has a community theatre association.

The Raymond Opera House, completed in 1909, was a venue for many local cultural events and attracted touring musicians and theatre companies. This photo shows the performance of Gilbert and Sullivan’s famed musical The Mikado. (Raymond Pioneer Museum)

The Raymond Opera House, completed in 1909, was a venue for many local cultural events and attracted touring musicians and theatre companies. This photo shows the performance of Gilbert and Sullivan’s famed musical The Mikado. (Raymond Pioneer Museum)

The Temple City Saxophone Band evidenced the ongoing enthusiasm for and commitment to music in the Cardston community. (Glenbow Archives ND-27-23)

The Temple City Saxophone Band evidenced the ongoing enthusiasm for and commitment to music in the Cardston community. (Glenbow Archives ND-27-23)

The LDS Relief Society organization for women was also a significant instrument for promoting cultural refinement in southern Alberta. From the early days of the Cardston settlement, Zina Young Card, wife of Charles Ora Card, directed numerous plays, and Relief Society women participated in lectures, recitations, and musical performances; they also won prizes at the Territorial Fair in Regina for painting and needlepoint.[64] All of this was done in addition to their duties of tending to the needs of the poor and the sick, caring for motherless children, holding work parties to piece quilts, sew carpet rags, and mend clothing.[65]

Boy Scouts

Scouting was introduced in southern Alberta in 1914, the same year it was incorporated in Canada by an Act in Parliament.[66] That year, Louisa Grant Alston of Magrath became Canada’s first female Scoutmaster. In this position, she helped train leaders and build the Scouting movement around southern Alberta. She subsequently received recognition from Canadian Scouting officials, including the Duke of Devonshire, who visited the western provinces, commended her troops, and appointed her the first female Scout Commissioner in 1917. Her influence must have extended beyond Canada, because she was recognized at a Salt Lake City rally as being the second most prominent woman in Scouting in America.[67] The LDS Church continues to be a strong supporter of Scouts Canada, with thousands of LDS young men and leaders participating in the program, despite the inability of some less well-developed congregations to maintain the program.[68]

Louisa Grant Alston, pictured here, was a pioneer of Scouting among Latter-day Saints in southern Alberta. (Magrath Museum)

Louisa Grant Alston, pictured here, was a pioneer of Scouting among Latter-day Saints in southern Alberta. (Magrath Museum)

Gospel Culture

Southern Alberta has been home to the full spiritual program of the Church. Many have a strong pioneer heritage. The choice to come to Canada in the first place was for many families an expression of faith. Some came to escape persecution for living the Church’s law of plural marriage, while others came in response to mission calls. Others came to settle in dry farming districts. Staying to farm in the sometimes-harsh southern Alberta climate tended to build faith and reliance on the Lord. Members of the Church in southern Alberta have had ready access to temple blessings for nearly a century, resulting in multigenerational families sealed[69] together in the temple. The proximity of the temple has also meant that southern Alberta Church members have been able to actively participate in temple service and to strengthen their faith through frequent temple attendance. Many members coming from southern Alberta have had rich experience in effectively run Church programs. Anecdotal reports suggest that southern Alberta wards still have some of the highest statistics in the Church for sacrament meeting attendance, home and visiting teaching, seminary graduation, and other key indicators of spiritual strength.[70] In the final analysis, the spiritual culture of southern Alberta has been the most durable and the most exportable.

The temple in Cardston, dedicated in 1923, was a focal point for the southern Alberta Latter-day Saints, strengthening them in their faith and anchoring subsequent generations in the gospel. Southern Alberta became a gathering place for the Saints across Canada. (Magrath Museum)

The temple in Cardston, dedicated in 1923, was a focal point for the southern Alberta Latter-day Saints, strengthening them in their faith and anchoring subsequent generations in the gospel. Southern Alberta became a gathering place for the Saints across Canada. (Magrath Museum)

Continuity and Change over Time

As noted, during the pioneering phase, the Church provided its members both spiritual and cultural nourishment. Much of the culture and many of the institutions of community life in southern Alberta came through the Church, giving the communities a distinctly Mormon and American flavor. Over time, however, Mormon towns in southern Alberta developed an increasingly Canadian feel, as the Church reduced its influence in community life and as governments, businesses, and community groups took over functions once filled by the Church. These typically Canadian institutions played a role in drawing the Mormon settlements into mainstream Canadian culture.

For example, from 1910 to 1921, the Church in southern Alberta operated a regional high school in Raymond, “The Knight Academy.” The teachers were university trained and some were from Utah. The curriculum included a program of “music, art, drama, household economics, industrial arts, religion and basketball along with the usual high school courses of science, mathematics, history and languages.”[71] Once public schools were introduced, the Academy was closed, so as not to compete with the public school system, and because funding the Church school in addition to the public school was burdensome to local residents.[72] Likewise, with the passage of time, schools and community organizations have taken over sports and community theatre as well. Canadian political, medical, educational, financial, and media institutions have further integrated southern Alberta communities into Canadian culture and lifestyle, making them fundamentally different from similar settlements in the United States.

Maintenance of Cultural Ties

While the US-Canadian border has sometimes acted as a barrier to American cultural transfer to Canada, Mormon cultural ties to the United States have remained strong, especially in southern Alberta, over the entire history of permanent LDS presence in Canada. When early Mormon settlers came to southern Alberta, they left family and friends behind in the United States. Keeping in touch with Utah relatives was a top priority. Establishing a postal service was on the list of requests that Charles O. Card made to the Canadian government in 1888 when he and his associates visited Ottawa.[73] The service was established soon thereafter. A rail line between Lethbridge and Great Falls was completed in the 1890,[74] and in 1894 a telephone line connected Cardston with Lethbridge and beyond.[75] In 1903, the St. Mary Railway was completed, connecting Stirling to Cardston via Raymond and Magrath with a branch line to Kimball.[76] These developments helped early settlers not only stay connected with each other, but to maintain contact with Utah. Every summer for many years, special excursion trains brought friends and family from Utah and Idaho to Canada and vice versa.[77]

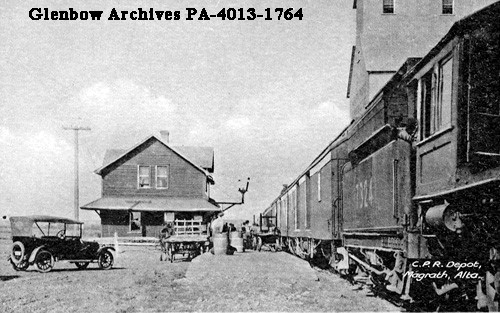

The Canadian Pacific Railway depot at Magrath, about 1925. Establishment of rail lines greatly facilitated travel between Utah and the Canadian Mormon settlements as well as among the Canadian Mormon settlements. (Glenbow Archives PA-4013-1764)

The Canadian Pacific Railway depot at Magrath, about 1925. Establishment of rail lines greatly facilitated travel between Utah and the Canadian Mormon settlements as well as among the Canadian Mormon settlements. (Glenbow Archives PA-4013-1764)

The Alberta settlements received frequent visits from general Church leaders including auxiliary and seminary leaders, Apostles, and even members of the First Presidency.[78] Apostle John W. Taylor sometimes lived in Alberta, as did many children and grandchildren of the First Presidency and Apostles of the Church.[79] With such regular contact, leaders in southern Alberta were trained in the latest Church policies and programs, enabling the Canadian Church to grow in a manner consistent with what was happening south of the border.[80] Likewise, southern Alberta leaders travelled to Utah for various conferences and training sessions sponsored by the Church.[81] Prior to the completion of the Cardston temple in 1923, southern Alberta members also travelled to Utah to attend the temple.[82] The Church sport tournaments and dance festivals provided another avenue for culture transfer between Saints in Canada and Utah.[83]

Another source of contact between Utah and Idaho and Canadian Mormons, especially those from southern Alberta, has been postsecondary education. Many Canadian Mormons have received postsecondary training at the old Brigham Young Academy, at Brigham Young University (BYU), or at BYU–Idaho (formerly Ricks College). Some settled in the United States following their education, but others returned to Canada with reinforced cultural ties with the American Church.

Young single adults of the

Young single adults of the

Kingsway Young Single Adult

Ward, Edmonton North

Stake, enjoy an activity suited

to their interests and needs.

There are approximately

thirty-five single adult wards

and branches across Canada.

(Brad Lybbert)

Today’s LDS communities in southern Alberta are the result of a 130-year evolution of LDS culture in a Canadian environment. Local Church members greatly appreciate their pioneer heritage and the deep sense of community they derive from their past. Many have large extended families close by and strong multigenerational heritage in the gospel.[93] The spiritual focus resulting from the close proximity of the temple has also been a lasting heritage. In recent years, small communities, affordable housing, large yards, extensive cultural and recreation programs, and good schools have increased the perception of southern Alberta towns as favourable environments for raising large families.

Beyond Southern Alberta: Mormon Culture and Expansion of the Church in Canada

Impact of Urbanization

As part of the massive trend toward urbanization after World War II, large numbers of Church members from rural southern Alberta began moving to major Alberta cities like Calgary and Edmonton, and to a lesser extent to other major cities throughout Canada. As these southern Alberta Church members moved, they brought their experience with the Church’s many cultural and recreational programs, which became a significant element for Church congregations in some of those locations. However, some cultural traditions, such as the sense of community that is a distinctive feature of Mormon settlements in southern Alberta, have not been fully transmissible to an environment where LDS form only a small minority of the total population. Most importantly, much of the spiritual heritage has been effectively transmitted by migrating southern Albertans. This heritage has been a valuable strength to members of the Church in parts of Canada with significant numbers of southern Alberta migrants. In other locations with fewer members native to southern Alberta, cultural traditions from southern Alberta have had little impact.

One example of southern Alberta culture being transmitted to an Alberta city was when, in the 1940s, some LDS students arrived at the University of Alberta in Edmonton and wanted to play basketball together in the university’s intramural league. However, to enter the league, they needed to belong to a university-sponsored club. Brigham Y. Card, a Church member who was a professor at the university, arranged for the organization of an LDS Club, which called for regular religious meetings in addition to organizing a basketball team. This LDS Club became the precursor to the development of the Institute of Religion in Edmonton as well as Institutes of Religion on university campuses across Canada.[94]

In the early 1960s, extensive Church sports and cultural programs were part of the official program in cities where the Church was well established.[95] Teams from across Alberta as well as from the Vancouver and Toronto Stakes competed for a chance to go to the all-Church tournaments in Salt Lake City. For example, the Calgary Fourth Ward was the Canadian champion in junior softball in 1965 and 1966 and competed in the all-Church tournament.[96] In due course, the Saints were able to build their own meetinghouses, which included gymnasiums complete with stages to facilitate the athletic and cultural activities of the Church.

Fund-Raising Projects

The Church in cities in which it was being newly established faced different challenges than the Church in southern Alberta communities, including the need to fund-raise for Church buildings, do missionary work, strengthen and integrate new converts, and improve the public image of the Church. Local Church leaders were both creative and inspired as they sought to fill these needs while also applying Latter-day Saint doctrines, such as, “whatever principle of intelligence we attain unto in this life, it will rise with us in the resurrection” (Doctrine and Covenants 130:18), “ye are the light of the world” (Matthew 5:14), and “where much is given much is required” (Doctrine and Covenants 82:3). Ingeniously, they were able to develop fund-raising projects that simultaneously improved the Church image and provided opportunities for members to develop their talents and share them with the community. Church cultural values, while appreciated and enjoyed for their intrinsic value, were thus adapted as a tool to meet the pressing needs of the local congregations.

One of the means used to generate funds was holding musical or dramatic performances for the community and raising funds from ticket sales. For example, as early as the 1920s, the Calgary Branch produced plays and performed them for the public to raise money for the Church.[97] A 1948 production of a Gilbert and Sullivan operetta in Edmonton raised $3,000 for the Church building fund.[98] Fund-raising dinners and rummage sales were held,[99] and booths at the Calgary Stampede and Edmonton Klondike Days were also important annual fundraisers in their respective cities.[100]

In Calgary and Edmonton, the Relief Society organized bazaars where Mormon handicrafts were displayed, taught, and sold to the public, with the dual purpose of raising money and integrating with the community. Children’s clothing, pillowcases, aprons, quilts, and other handicrafts made by Mormon women were very popular, and the bazaars were good fundraisers and also received significant media attention.[101] When Hattie Jensen, a native of Aetna, Alberta, was living in Edmonton, she was asked to crochet two doilies to sell for a bazaar. However, she suggested an even better plan. Growing up in southern Alberta, she had learned the art of chocolate making, and she suggested making chocolates to sell instead.[102] In time, chocolate making developed into a massive operation in its own right in Edmonton, involving all adults, and it is said that the first Edmonton stake centre (now the Bonnie Doon Stake Centre) was “the church that chocolates built.”[103] Chocolate-making was so successful that the skills were formally taught to Relief Societies across western Canada and into eastern Canada, and were even demonstrated at a Relief Society conference in Salt Lake City.[104] At its peak, the Church in Edmonton sold twelve thousand pounds of chocolates each year.[105]

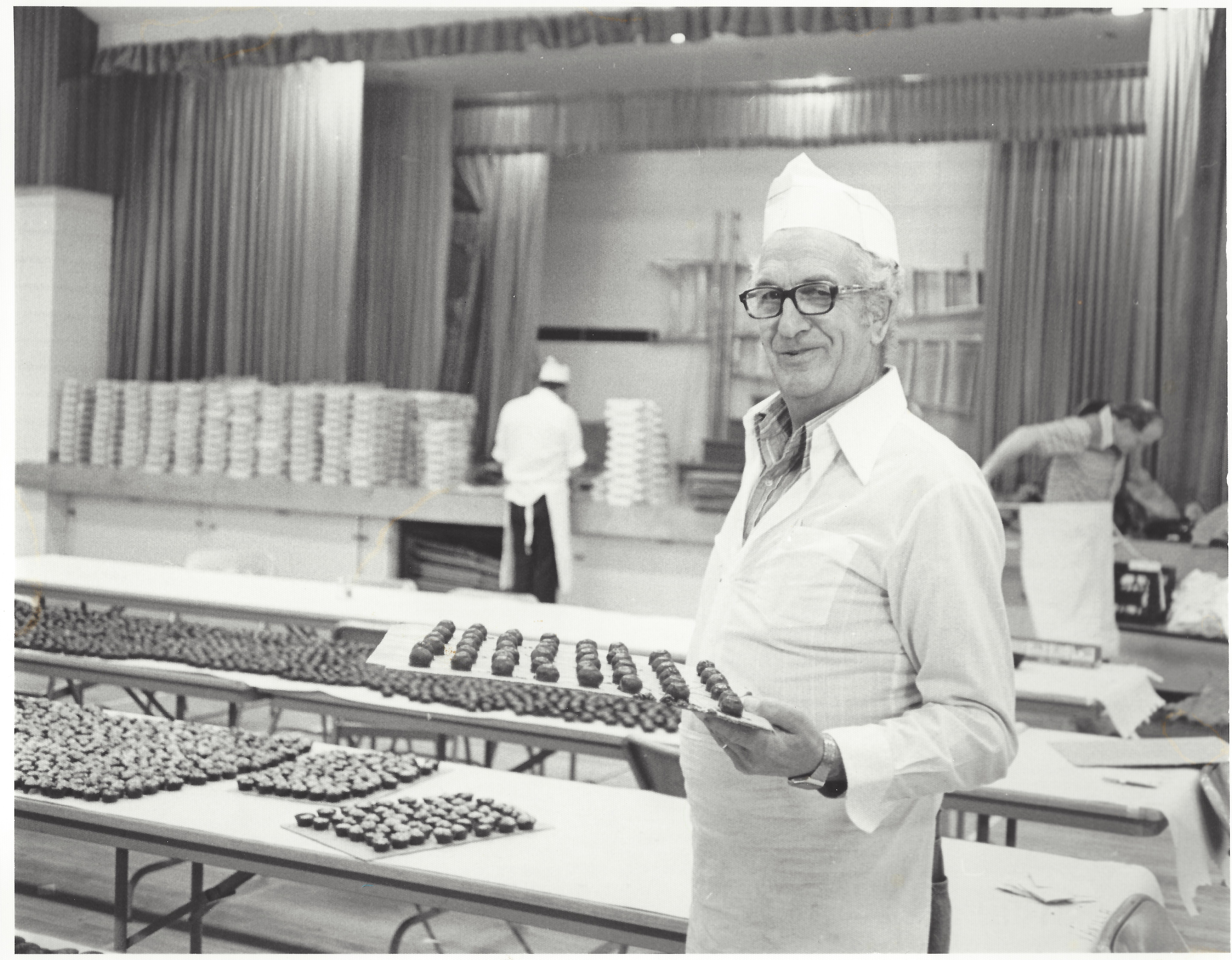

Beginning with the efforts of Relief Society women in Edmonton, chocolate-making became a very successful fund-raising activity in many parts of Canada. Shown here is Varge Gilchrist, patriarch of the Ottawa Stake, helping with chocolate making in Ottawa in 1980. (Gail Schow)

Beginning with the efforts of Relief Society women in Edmonton, chocolate-making became a very successful fund-raising activity in many parts of Canada. Shown here is Varge Gilchrist, patriarch of the Ottawa Stake, helping with chocolate making in Ottawa in 1980. (Gail Schow)

In Vancouver, the Church was smaller relative to the population, but it seems to have had similar cultural and fundraising experiences in the postwar period. The members held a production of “Promised Valley” in 1961 and hosted travelling performances of the Ogden Chorale, the combined choruses of the Institutes of the University of Utah, and other groups. These events raised funds for buildings and/

Promised Valley, a musical stage production composed in 1947 for the centennial of the Mormon pioneers’ arrival in the Salt Lake Valley, was produced in various parts of Canada, including Edmonton (shown here) in the early 1960s, Vancouver in 1961, and Calgary in 1973. (Courtesy of Walter Meyer)

Promised Valley, a musical stage production composed in 1947 for the centennial of the Mormon pioneers’ arrival in the Salt Lake Valley, was produced in various parts of Canada, including Edmonton (shown here) in the early 1960s, Vancouver in 1961, and Calgary in 1973. (Courtesy of Walter Meyer)

The Toronto Stake was formed in 1960—the same year as the Vancouver Stake. Though its members were even more scattered, efforts were made to implement the Church’s sports and cultural programs. The stake held track and field competitions in the 1960s.[107] The track and field event, featuring individual sports, could be held on a single day. This avenue for promoting sport was more realistic for the new Toronto Stake than putting together teams to compete in the Church wide basketball or baseball tournaments, especially given the distance of over two thousand miles from Church headquarters. However, some Church ball teams were also organized in the Toronto area.[108]

Mormon Culture in the Mission Field

In the post war era, majority LDS communities in southern Alberta continued to focus heavily on developing well-rounded individuals and strong communities. In Alberta cities, and to a limited extent in Vancouver and Toronto, the focus was on adapting the full Church program to help with fundraising and public image issues. Church members in the rest of Canada faced entirely different realities. After the directive, beginning in early 1900s, for members to build Zion locally rather than gathering to Church settlements, there began to be small numbers of Church members living in isolation from each other across Canada. Some of these members originated in southern Alberta, some came to Canada from other locations, and the bulk of them were local converts.

In pioneering the Church in each location, it was wholly unrealistic to try to implement the full cultural and athletic programs of the Church. Early members faced many challenges, including geographic isolation, difficulty gaining access to Church resources, coping with profound anti-Mormon prejudice, and getting missionaries into their areas. Branches and districts administered by the mission president and missionaries naturally had a much greater emphasis on missionary work than wards and stakes administered by local leaders. Missionary open houses, cottage meetings, missionary firesides, and other activities were a significant part of the Church in its pioneering phase in these areas.

Later, efforts had to be made in each area to train leaders to effectively administer the priesthood and Church programs, before stakes could be formed. Often a limited number of well-trained faithful members were kept extremely busy trying to run the basic programs of the Church while tending to far-flung members and to those who were new to or struggling in the faith. Members also faced challenges in raising children in the faith while living in an environment that could be hostile to the Church. Later, as the Church grew in each location, the members added a focus on fundraising for Church buildings and other needs and on improving public perceptions. While the full sports and cultural program of the Church could not be implemented in all parts of Canada, some parts of the Church program such as roadshows and gold and green balls were widely adopted. Road shows, which are short musical plays, were written and staged by individual wards and branches and performed in stake competitions in many parts of Canada. Annual gold and green balls (formal dances) were also widespread.

Angels with harps in a ward roadshow, Edmonton, 1976. Roadshows, a popular activity throughout the Church, were original, short, and often humorous musical stage productions with simple costumes and portable sets and props. (Walter Meyer)

Angels with harps in a ward roadshow, Edmonton, 1976. Roadshows, a popular activity throughout the Church, were original, short, and often humorous musical stage productions with simple costumes and portable sets and props. (Walter Meyer)

One element that was not lacking, as Saints struggled to help the Church gain a foothold in isolated locations, was faith. Joseph Smith taught the principle that sacrifice builds faith, so it is not surprising that incredible faith was often found among those Saints who had to sacrifice the most to be faithful members of the Church. Not distracted by sports or dramatic productions, members transplanted from southern Alberta were able to strengthen and transmit the most important part of their culture—their core testimony of the gospel—to help strengthen the Church around the country. Faithful members who were converts to the Church or transplanted from elsewhere are also among the pioneers who built up the Church in their own areas. The faith of these pioneers was deepened by their need to rely on God in difficult circumstances.

The Diffusion across Canada of Solutions for Fund-Raising and Improving Public Image

Fundraising, missionary work, and improving public perceptions of the Church were major issues everywhere in Canada as the Church tried to establish its presence outside southern Alberta. While all Canadian LDS Church units operated under a uniform set of Church policies and handbooks which applied to the Church around the world, these policies did not often dictate the specifics of how to fundraise, share the gospel, or integrate with the community. The Church had no Canadian-specific structure to share ideas for activities and programs or deal with uniquely Canadian needs.[109] Thus, it is interesting to observe the spread of ideas across the country and to notice that some locations developed entirely original ways to deal with issues many Canadian Mormons had in common. In terms of fund-raising, chocolate making, bazaars, and having booths at fairs were dominant ideas in Western Canada. In the Maritimes, a completely different tradition emerged. Gingerbread houses were made and sold in Halifax as a successful fundraiser. Wards in many parts of Ontario delivered flyers, including Sears and Canadian Tire catalogues.[110] While there was some chocolate making in eastern Canada and some catalog delivery in western Canada, the dominant traditions were dissimilar.

Overcoming prejudice and false impressions about the Church has been big issue for members of the Church around Canada. In Calgary in 1964, Western Canadian Mission pioneered a live outdoor nativity pageant as a service to the community and to help overcome perceptions that Mormons are not Christians. The Calgary pageant has now been running annually for over fifty years. It takes place at Heritage Park where it attracts about twenty thousand community members each year.[111] In 1977, the Kingston Ward of the Ottawa Ontario Stake, on the completion of its new building, adapted the Calgary outdoor nativity pageant, put on by the joint efforts of two Calgary stakes, to a production that could be presented by a single ward or branch. Both pageants were so successful that other branches, wards, and stakes across Canada have also embraced nativity pageants as a way to improve the profile of the Church and render service to the community.

The rise of outdoor nativity pageants in other areas of eastern Canada, regardless of the cold weather, has often coincided with members from Kingston moving into an area and reporting to Church leaders on the relative merits of such an activity. For example, John Ekin, who was involved in the Kingston pageant, moved several times and helped start pageants in other places he lived, including Smith Falls, Ottawa and Newmarket, Ontario. Tim Holt, the set designer from Kingston, was instrumental in bringing nativity pageants to Halifax, Nova Scotia, and Trenton, Ontario. At least sixteen pageants were spin-offs from the Kingston pageant.[116] Other nativity pageants trace their origin directly to the Calgary pageant. As of 2013, there were nativity pageants in Calgary, Cardston, Lethbridge, Spruce Grove, and Taber, Alberta; Duncan and Victoria, British Columbia; Kindersley and Swift Current Saskatchewan; Winnipeg, Manitoba; London, Brampton, Kingston, Ottawa, Newmarket, Ontario; Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island; and Dartmouth, Nova Scotia.[117] Several wards and branches, such as in Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, and Walkerton, Ontario, have opted to provide a community service by hosting an indoor crèche display for the community.[118]

Expanding into the French Language

As the Church expanded into Quebec where the majority population is French-speaking, and as Canada has become more multicultural and multilinguistic, the Church has made efforts to provide access to the gospel in the native tongue of its members and prospective members. In Quebec, prior to the Quiet Revolution, missionary work was largely unsuccessful among French Canadians, and the first Church units in Quebec were English-speaking (see chapter 14). However, in 1961, when Thomas S. Monson was president of the Canadian Mission, French-speaking missionaries were assigned to work among Francophones in Montreal. Baptisms followed, and the English-speaking Montreal Branch began holding an additional weekly sacrament meeting and Sunday School in the French language to accommodate new Francophone converts and French-speaking people who were investigating the Church. In 1964, the first French-speaking congregation in Canada was formed in Montreal, called the Hochelaga Branch.[119]

In 1969, the Church in Quebec had an enormous opportunity to get into the public eye. The Church leased space on the site of the 1967 Montreal World’s Fair, Expo 67, where a subsequent exhibition, “Man and His World,” was held for several years. The Church constructed a pavilion, featuring the film Man’s Search for Happiness, along with displays about the restoration of the gospel. In 1969, the first year the Mormon pavilion was opened, more than three hundred thousand people visited and learned more about the Church. This pavilion jumpstarted missionary work in Quebec at the time when French-speaking Quebecois were experiencing the cultural change called the Quiet Revolution and were beginning to look outside the Catholic Church for answers.[120] French-Canadians joined the Church in considerable numbers in the years that followed. In 1978, the first French stake in North America was formed in Montreal, and in 2006 a second French stake was organized in Longueuil, Quebec.[121]

Ethnic Wards and Branches

Canadian immigration policy has gradually changed the ethnic composition of Canada (see chapter 4). In the late 1960s, immigration policy officially defined Canada as a bilingual and multicultural country. As a country that celebrates multiculturalism, Canada has become home to people, cultures, and languages from practically every country in the world. In the United States, ethnic wards and branches were established beginning in the early 1960s under the direction of President Spencer W. Kimball, who was “an enthusiastic supporter of ethnic units.”[122] In Canada, members of minority language communities began joining the Church while others arrived in Canada already belonging to the Church. Soon the Church organized a number of “specialized congregations” in Canada as well to meet the linguistic and cultural needs of these immigrants.[123] According to Jessie L. Embry, the establishment and growth of ethnic wards and branches followed the scriptural admonition to teach the gospel to people in their own language,[124] and was “a logical outgrowth of ethnic proselyting” and the establishment of “ethnic Sunday Schools”[125] associated with English-speaking wards.

Ethnic and linguistic wards and branches are “culturally comfortable places for members to worship in their native language.”[126] They serve as centres of ethnic cohesion, as these wards and branches tend to have more “planned activities unique to that culture,”[127] decreased potential prejudice, and more opportunities for members to serve in Church callings.[128] However, some ethnic and linguistic wards and branches face challenges, including small membership and inadequate leadership to run the full program of the Church. Separating by language or ethnicity may make it harder for immigrants to integrate with the majority language and culture. In addition, there is also a school of thought that because the gospel supersedes all cultures and languages, wards and branches should integrate and accommodate all cultural and linguistic differences among their membership.[129] Church leaders weigh all these considerations when making decisions to create and occasionally to disband ethnic and linguistic wards and branches. In 2015, there were twenty wards and branches across Canada whose language was neither English or French, most of which were in Canada’s largest centres, Vancouver, Calgary, Toronto, and Montreal. Of these, thirteen were Spanish-speaking, six Chinese (three Mandarin, one Cantonese, and two designated “Chinese”), and one Korean.[130] In many other cases, wards that are “English” or “French” actually have members from many ethnic, linguistic, and cultural backgrounds (sometimes referred to as “integrated wards”).[131] In those cases, members do their best to accept differences, overcome language barriers, and serve one another.

These Korean dancers, performing in “Every Nation, Every People,” a 2007 Church-sponsored program in Vancouver, shared their unique culture with an appreciative audience. In the same program, groups from other heritages and backgrounds likewise brought their own colourful music and dance to the stage, showcasing the ethnic diversity of the area. (John McCulloch)

These Korean dancers, performing in “Every Nation, Every People,” a 2007 Church-sponsored program in Vancouver, shared their unique culture with an appreciative audience. In the same program, groups from other heritages and backgrounds likewise brought their own colourful music and dance to the stage, showcasing the ethnic diversity of the area. (John McCulloch)

Political Culture of Canadian Mormons

Although the political culture of Canadian Mormons is not fully documented and more research is needed in this area, it is known that early settlers in Cardston tried their best to integrate into the Canadian political system. In the 1890s, Charles Ora Card advised Church members to “make a good showing at the polls,” and that they were “at liberty to choose either of the national parties.” He also counselled them to “avoid political excitement.”[135] His advice reflected LDS policy of encouraging political involvement while remaining politically neutral, a policy which continues into the twenty-first century. While the early settlers were sometimes bewildered by the Canadian political process,[136] in time members of the Church found their way onto the political stage in Alberta.

Over the course of the history of the Province of Alberta, Mormons have served as Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) in numbers roughly proportionate to their population; between two and three percent of all Alberta MLAs have been LDS, while roughly two percent of the Alberta population is LDS.[137] While most MLAs for the Cardston constituency (now Cardston-Taber-Warner) have been LDS,[138] there have been several LDS MLAs representing other constituencies as well. It is a notable reflection of the acceptance Mormons enjoy in Alberta that religious affiliation has not been an issue for these provincial candidates. Even when Mormon Gordon Kesler was elected in 1982 to represent the Western Canada Concept Party (a western separatist party), though much was made of his election in the media, his religious background was not often mentioned.[139] Several LDS MLAs have also served in the cabinet of the Alberta Government, including N. Eldon Tanner, Solon Low, Edgar Hinman, Bill Payne, Jack Ady, and Cindy Ady. The cities of Lethbridge, Calgary, and Edmonton have each had an LDS mayor.[140]

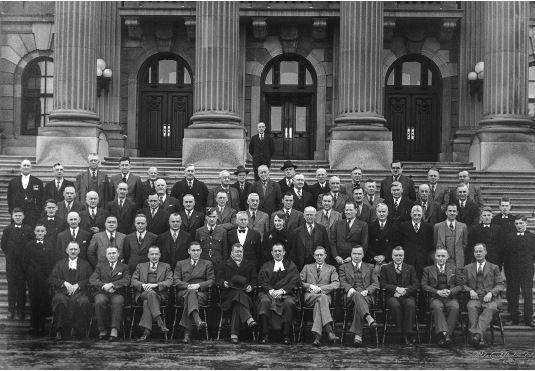

Many Latter-day Saints have served as members of the Alberta Legislative Assembly over the years. The 1944 photograph of all members of the Assembly shows the diversity of political philosophies among Church members. N. Eldon Tanner, a senior cabinet minister in the Social Credit government, was serving at the same time that Jim Walker, another LDS member of the Legislative Assembly, was the leader of the opposition party. Every Alberta Legislative Assembly from 1905 to 2015 has included at least one Latter-day Saint. (Provincial Archives of Alberta A3581)

Many Latter-day Saints have served as members of the Alberta Legislative Assembly over the years. The 1944 photograph of all members of the Assembly shows the diversity of political philosophies among Church members. N. Eldon Tanner, a senior cabinet minister in the Social Credit government, was serving at the same time that Jim Walker, another LDS member of the Legislative Assembly, was the leader of the opposition party. Every Alberta Legislative Assembly from 1905 to 2015 has included at least one Latter-day Saint. (Provincial Archives of Alberta A3581)

On the Federal level, only five Latter-day Saints have ever served as Members of Parliament—all from Alberta.[141] Few, if any, members of the Church have served as members of their provincial legislative assemblies outside Alberta. The underrepresentation of Mormons in politics in the rest of Canada may in part be explained by the fact that the Church is run by a lay ministry; the time faithful members give to Church service is especially great where congregations are small. While Church members in Alberta feel a sense of community as members of the Church, members in other places around Canada, where they constitute a small minority of the population, may feel apart from the community as a whole and therefore uncomfortable representing it. Another deterrent for would-be Mormon political candidates might be fear of bringing upon themselves and their families the hostility they have seen displayed in the mainstream media toward traditional social values in general and toward the LDS Church in particular.

The Church has voiced positions on social issues such as alcohol, abortion, gay marriage, and gambling, and on occasion Church members have been mobilized into the political arena to support the Church’s position. This was the case in Alberta in 1998 when several communities were circulating petitions to force a plebiscite on banning video lottery terminals. The Church mobilized its members in Edmonton and Calgary to work with other churches who opposed gambling to canvass for signatures on the petition. Church members in each city gathered about half of the needed signatures, and the plebiscites were held.[142] Church members also partnered with like-minded people in Saskatchewan to oppose gambling.[143]

Prohibition of alcohol has been an important issue to members of the Church in southern Alberta towns for more than a century. E. J. Wood was active in the early twentieth century in the campaign for prohibition, and a high percentage of Mormon settlers voted to keep alcohol out of their communities.[144] In 2014, the town of Cardston, still predominantly LDS, held a plebiscite on whether to uphold the century-old ban on liquor sales in the town, as well as whether to rent out town recreational facilities on Sundays. (The facilities had been closed on Sundays.) With a high voter turnout, 68 percent of voters favoured upholding a complete liquor ban, while 67 percent opposed opening recreation facilities on Sundays, even for rentals.[145] In this case, a strong majority of Church members voted to have their community support LDS values.

With respect to party politics, there is not much data on how church members vote. However, there is no reason to think that they vote as a block. While the Church encourages its members to participate in the political process, it does not endorse candidates or parties. Members of the Church are left to use their own judgment to choose representatives that most closely reflect their values and interests. The choice of candidates is not considered appropriate discussion in church services.

In the United States, Mormons have tended to vote Republican more than Democrat, with the likelihood of voting Republican increasing with higher levels of activity in the Church.[146] However, unlike the United States, political parties in Canada have not always been delineated by stands on social and moral issues. The Liberal Party has traditionally had more liberal social policies than The Progressive Conservative Party, but neither represented an especially socially conservative point of view. The Conservative Party of Canada, formed in 2004 under Stephen Harper, has included social conservatives in its “big tent.” While they did not reopen morally divisive issues, the Conservatives had several policies that supported families that chose to have a parent stay home with children.[147] However, there is no data to determine if Mormons vote Conservative more than their neighbours. While the majority of Mormons in southern Alberta seemed to vote Conservative in recent federal elections, this is also a reflection of the regional tendency to vote Conservative in Alberta. Members of the Church around Canada are likely influenced in their voting by regional trends, and further research is needed to understand what impact, if any, Church membership has on voting in Canada.

The Impact of the US–Canadian Border on Church Administration in Canada

The international border continues to have a significant impact on the development of the Church in Canada, even as the Church becomes well established. In particular, because institutions, laws, and regulations are different in Canada, the Church has had to incorporate itself as a legal and financial entity separate from the main Church headquarters in the United States. Incorporation provides the Church with several advantages, including separating the Church as a legal entity from individual members; limiting the liability of regular Church members and Church leaders with regards to Church debt or the actions of other Church members; purchasing, selling, transferring, and mortgaging land regardless of membership changes; being able to bring legal action in its own name; entering into legal contracts as a corporation; and ensuring continuity when membership and/

Victims of drought and famine in a refugee camp in Korem, northern Ethiopia, in November 1984. A devastating famine killed up to one million people in Ethiopia between 1983 and 1985, leaving millions of others destitute. On 27 January 1985, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints held a special fast for the famine victims. The Canadian Saints raised $250,000, which was donated to the Canadian Red Cross. The Alberta government matched the Church’s donation, and the federal government matched the combined Church and Alberta government donations. (Contact Press Images)

Victims of drought and famine in a refugee camp in Korem, northern Ethiopia, in November 1984. A devastating famine killed up to one million people in Ethiopia between 1983 and 1985, leaving millions of others destitute. On 27 January 1985, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints held a special fast for the famine victims. The Canadian Saints raised $250,000, which was donated to the Canadian Red Cross. The Alberta government matched the Church’s donation, and the federal government matched the combined Church and Alberta government donations. (Contact Press Images)

Under Canadian law, the LDS Church in Canada incorporated into a legal entity in 1926–27. All Church property in Canada is held in the name of “The president of the Lethbridge Stake of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.” Finances of the church are held in the names of the Stake Presidents of the Church in Canada with two stake presidents in Calgary serving as trustees for the Church in Canada. All financial documents for the Church in Canada are signed by these trustees.[149]

The incorporation of the LDS Church in Canada was necessary in part because the border acts as a barrier to the free flow of money from the LDS Church’s Canadian corporation to the Church headquarters in Salt Lake City. Canadian law limits donations sent from Canada directly to Salt Lake City to 5 percent of total revenues,[150] and since the Canadian Church collects more than it needs to manage and administer the Church’s programs, pay its full- and part-time employees, and maintain its buildings, it has to find appropriate ways to use this money to serve the world wide Church while obeying Canadian law. For example, money donated to the general missionary fund stays in Canada and is sometimes used to fund missionaries from around the world who are assigned to missions in Canada. Money is also donated to Church-affiliated charities, to other non-LDS charities and to institutions that the Canadian government recognizes as “qualified donees,” such as Brigham Young University.[151]

The famine in Ethiopia provided an example of how the border acts as a financial barrier. In 1985, the First Presidency of the LDS Church called for a North America–wide fast for the victims of the Ethiopian famine. Canadian Saints donated $250,000 as part of the special fast. However, Canadian law did not permit the money to be sent to Salt Lake City for the Church to send directly to Ethiopia. A decision was made by Canadian Church leaders, after consultation with Church headquarters, to donate the money to the Canadian Red Cross, a qualified donee. The Alberta government decided to match the Church’s contribution of $250,000, and then the Canadian government matched the Church’s and the province’s contributions, so that in total one million dollars was donated to the Canadian Red Cross, which was reportedly the largest single donation to the organization up to that time.[152]

The border also acts as a barrier for bringing Church materials to Canada. L. David McLachlan, a former president of the Lethbridge East Stake, was one of a series of LDS employees who worked at the custom broker H. H. Smith. Part of McLachlan’s job was to handle all the LDS Church accounts from 1994 to 2011. His challenge was to facilitate the importing of Church materials, such as curriculum books, temple clothing, Church magazines, building materials, and disaster relief supplies in such a way as to strictly comply with Canadian laws, while keeping expenses as reasonable as possible. Minimizing postage expenses for the Church News and Church magazines has also been a priority. As a result, all Church magazines clear the border at Coutts and are shipped to Calgary, where they are mailed to homes across Canada.[153]

Young Men and Young Women receive training in job-seeking skills at the LDS Employment Centre in Lethbridge. This multifunction facility not only has employment and counselling services but also houses a bishops’ storehouse which provides groceries for those in need. In addition, it stocks food storage products and has a dry pack canning facility. The five bishops’ storehouses in Canada (one in British Columbia, three in Alberta, and one in Ontario) must carefully comply with Canadian law to stock their shelves. (Darrel Nelson)

Young Men and Young Women receive training in job-seeking skills at the LDS Employment Centre in Lethbridge. This multifunction facility not only has employment and counselling services but also houses a bishops’ storehouse which provides groceries for those in need. In addition, it stocks food storage products and has a dry pack canning facility. The five bishops’ storehouses in Canada (one in British Columbia, three in Alberta, and one in Ontario) must carefully comply with Canadian law to stock their shelves. (Darrel Nelson)

Part of the challenge associated with importing goods from the United States into Canada is that they are subject to Canadian import laws and regulations. For example, all temple clothing has to be labelled in accordance with Canadian clothing labelling laws. Canned foods for the bishops’ storehouses in Canada, which are part of the LDS Church’s vast welfare system that allows the Church to look after the temporal needs of its members and other members of the community, are no longer being brought from the Church canneries in the United States because nutritional and language labelling laws made their import impractical. Instead, the Church in Canada contracts with Canadian food suppliers to stock the shelves of the bishops’ storehouses. Some food storage items are still imported from the United States. For example, hot chocolate for dry pack canning was approved for importing, but only after it was determined to have a high enough sugar content to be classified as confectionary rather than dairy. Wheat imports and exports have historically been limited because of the Canadian Wheat Board. Building materials, furnishings for chapels and temples, and disaster relief supplies are all imported in accordance with Canadian law. Local construction companies are often selected to build Church buildings because of Canadian labour laws as well as a desire to support local economies.[154]

Fashioning a Distinctive Canadian Mormon Identity

The question of national identity is very complex, especially in a country such as Canada, which has distinct regional identities, including a strong sense of “nationality” in French-speaking Quebec. In 1968, the Liberal government of Pierre Elliott Trudeau, giving due recognition to the French population of Quebec as one of the founding peoples of Canada, and the vast ethnic differences within the country, defined Canada as a bilingual, multicultural country. In Canada, regional identities are much more pronounced than in the United States, with various regions clamoring for either special recognition or a larger share of the national wealth.

Shaped by a history and tradition quite different from the United States, Canadian culture tends to be more European than American culture. While similar in its concept of democracy and the rule of law, Canada has a parliamentary system of government, based on the British model rather than the American presidential system. In terms of foreign policy, since World War II, Canada, while engaging with the United States in NATO and cooperating on other security issues, has had more focus on UN-based peacekeeping missions than the United States, and has been selective in which American wars it participates. Canada, typically, has had a more open policy toward immigration and refugees than the United States has had. On social issues, on the European model, Canada has had state-paid medicine for more than fifty years and has long since abolished the death penalty. Canadians tend to be much more environmentally conscious than their American counterparts, and some provinces have extensive recycling programs. Gay marriage, accepted in the United States by a Supreme Court ruling in 2015, had been legal in Canada for more than a decade. While Canadian Mormons may not support and in fact may oppose many of the social aspects of the country which run counter to traditional beliefs or family values, the fact of living in the country and being Canadian has forged a deep sense of Canadian patriotism and identity. At the same time, they as Mormons have had a deep sense of identity as Mormons, who have distinctive beliefs and practices. Following the Mormon settlement in Alberta, Mormons began to forge a sense of being Canadian Mormons. Arguably, that identity has persisted in one form or another in succeeding generations.