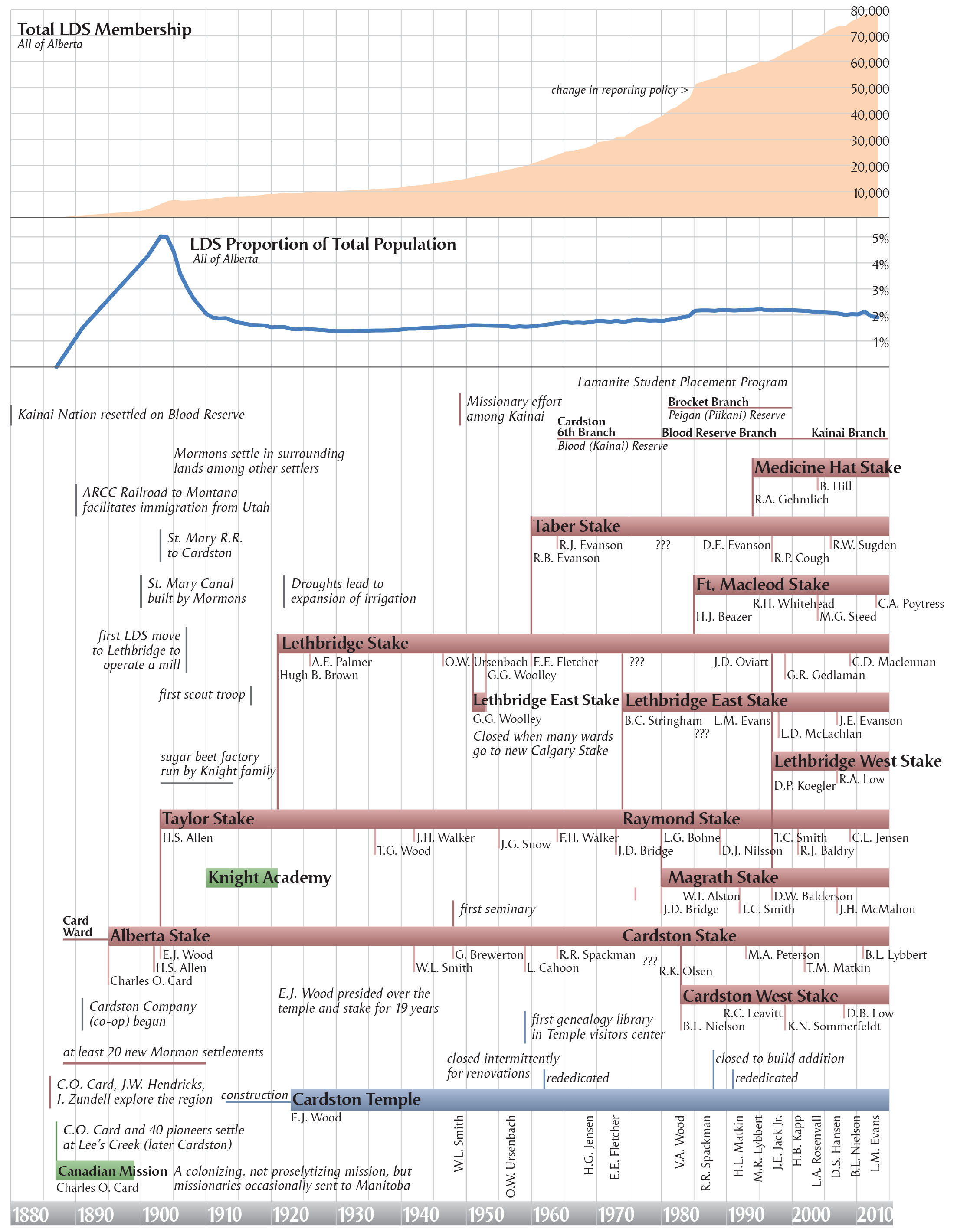

The Alberta Settlement

Rebecca J. Doig and W. Jack Stone

Rebecca J. Doig was born in Edmonton, Alberta, and raised in Kingston, Ontario. She earned a BA in history from Brigham Young University and an MA in history from the University of Alberta. She also served a mission in Nagoya, Japan. She is married to Robert P. Doig and is the mother of four children. She has served on several community boards and in many callings in the Church, including Primary president, Young Women president, Relief Society president, and stake Young Women president. She and her family currently reside in Magrath, Alberta. (Rebecca Doig)

W. Jack Stone was born in Raymond, Alberta. After serving an LDS mission in the eastern Atlantic states, he graduated from Brigham Young University with a BA in English and education, where he subsequently completed an MA in educational psychology and a PhD in educational administration. Making his career in the LDS Church Educational System, he taught in various places, including Cardston and Calgary, Alberta, and Ottawa, Ontario, eventually becoming the CES director for all of Canada for ten years. One of his long-term special interests has been collecting noteworthy stories and materials related to the history of the LDS Church in Canada. He has served as Sunday School teacher, bishop, counselor in two stake presidencies, and counselor in two mission presidencies. He and his wife, Janice, are currently temple workers. They have ten children and thirty-nine grandchildren. (Jack Stone)

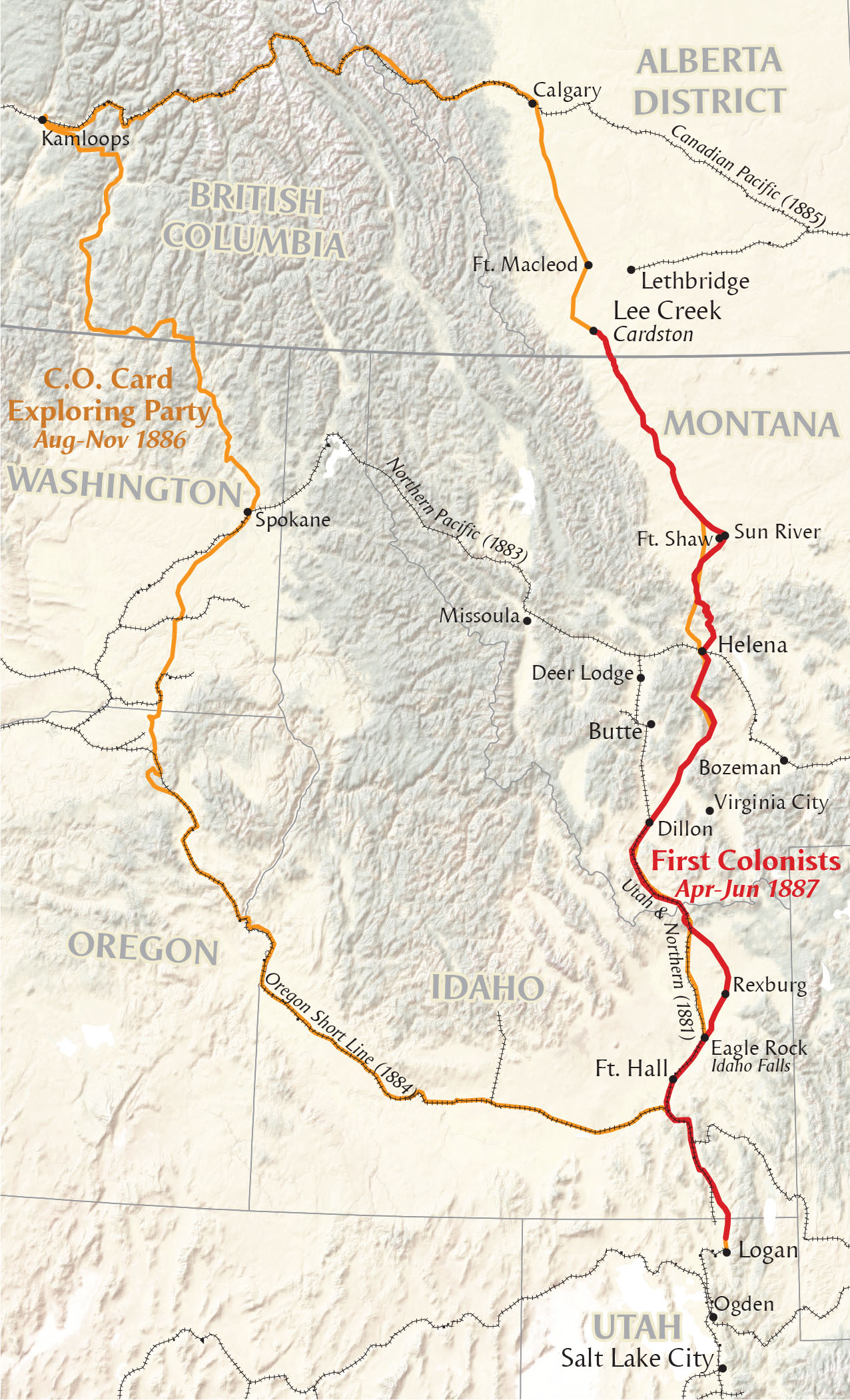

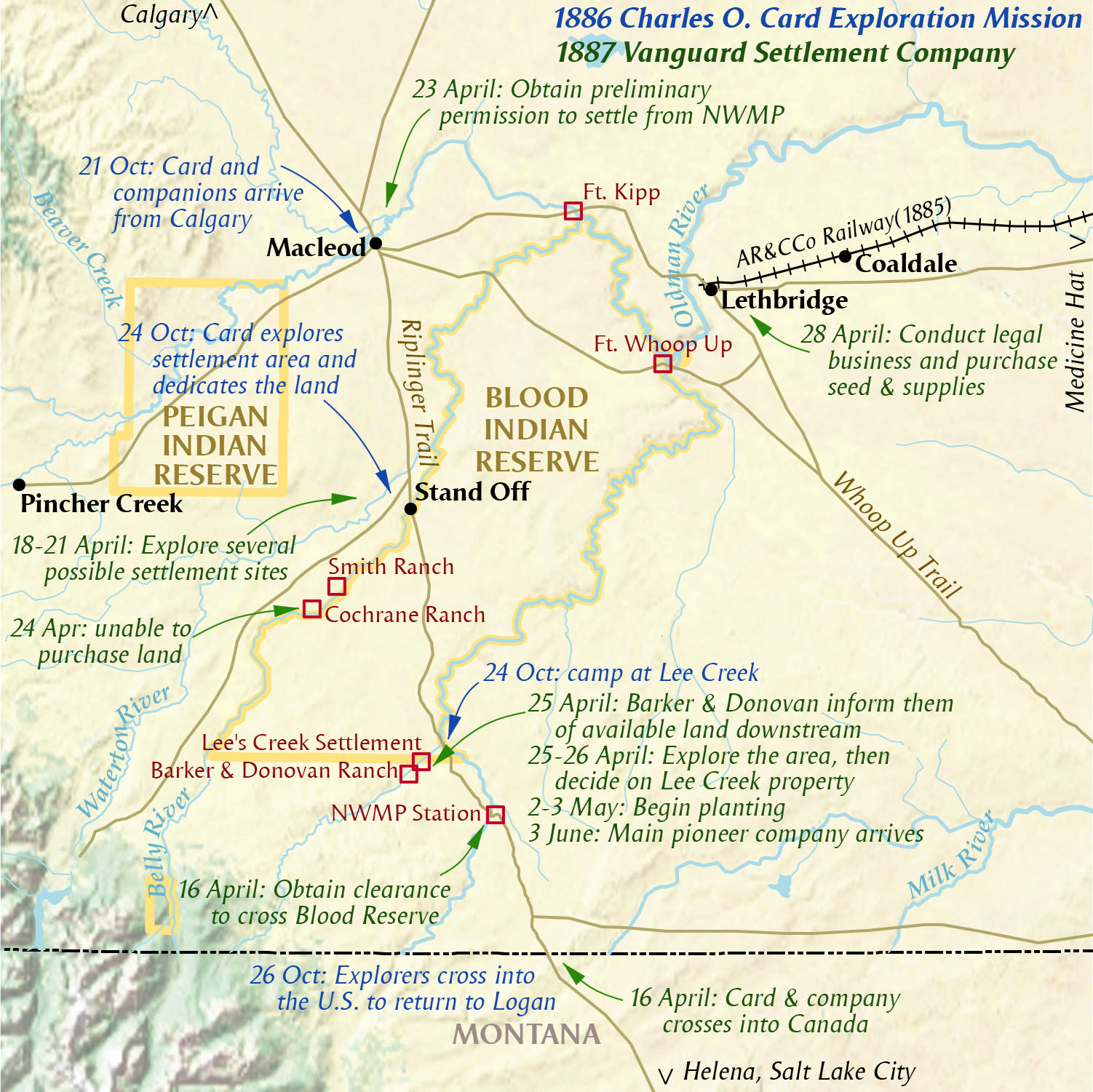

Charles O. Card and two companions made an exploratory trip from Utah to Canada in 1886, travelling from Cache Valley, Utah, to British Columbia and then across the mountains to Alberta. Card decided that southern Alberta would be a suitable place where Latter-day Saints could settle. The following year, he led a small group of forty-one Mormon settlers from Cache Valley to Alberta, establishing a town at Lee Creek,[1] later named Cardston, the focal point for the development of Latter-day Saint settlement in southern Alberta.

Charles O. Card and two companions made an exploratory trip from Utah to Canada in 1886, travelling from Cache Valley, Utah, to British Columbia and then across the mountains to Alberta. Card decided that southern Alberta would be a suitable place where Latter-day Saints could settle. The following year, he led a small group of forty-one Mormon settlers from Cache Valley to Alberta, establishing a town at Lee Creek,[1] later named Cardston, the focal point for the development of Latter-day Saint settlement in southern Alberta.

When Charles Ora Card and his little band of refugees established a settlement at Lee Creek, Alberta, in the spring of 1887, a new era of permanent LDS settlement in Canada humbly began. To these first settlers, Canada was a haven from prosecution for the practice of plural marriage. Many who followed in the next few years found similar refuge in Canada, settling several communities in the Cardston area.[2]

However, it soon became apparent that Canada would also be a land of opportunity for LDS settlers. When economic difficulties hit Utah in the 1890s, many young LDS families looked beyond Utah for a place to settle. Meanwhile, Charles Ora Card and southern Alberta entrepreneurs and land owners Elliott Galt and Charles A. Magrath had been collaborating on an ambitious irrigation building and settlement plan. In the realization of these plans, LDS settlers, many of whom came in response to mission calls, poured into southern Alberta in 1899 and 1900, completing a canal from Kimball to Stirling with a branch to Lethbridge and establishing villages in Magrath and Stirling. Two years later, a fourth major settlement was established when LDS entrepreneur and philanthropist Jesse Knight bought a huge tract of land and committed to building a sugar factory, which would provide employment and open lands for settlement in Raymond and area. This time no mission calls were needed to help Mormon settlers see the opportunities before them. As Mormons spread across southern Alberta in additional settlements, Saints migrated in groups or as individual families to pursue opportunities to homestead, ranch, build industry, or pursue education and employment in cities.

Canada was a place of challenge for Mormon settlers, and these challenges tended to strengthen faith for those who remained. The southern Alberta climate can be harsh. Fierce winds, dry seasons alternating with flood years, hailstorms, untimely frosts, and powerful snowstorms are among the elements southern Albertans have had to contend with over the years. The fickleness of nature on the foothills and prairies of southern Alberta often brought the Saints to their knees in prayer and fasting. Many times throughout the 130-year history of Mormons in southern Alberta, Church leaders have promised rain or some needed change or tempering of the elements in response to the faith of the members, and many times these promises have been fulfilled in seemingly miraculous ways.

In summary, this chapter on the LDS settlement of southern Alberta until 1923 is a story of immigrant Latter-day Saints coming from the United States seeking refuge, responding to mission calls and looking for economic opportunities. It is the story of the establishment of several Church-organized settlements, as well as non-Church-directed settlements and clusters of LDS families across southern Alberta. It is a story of the introduction of irrigation to an arid region and the area’s resulting growth and expansion, including the development of industry and innovation that contributed to the overall development of southern Alberta. This happy story is sometimes interrupted by crop and livestock failures and personal tragedy as the Saints sought to make their way on the unpredictable Alberta foothills and prairies. It is a story of growing acceptance for Latter-day Saints among the general population of southern Alberta, facilitated by the support of Charles A. Magrath and Elliott Galt. It is a story of a humble people living their religion and building their faith. This chapter culminates in the completion of the landmark Cardston Alberta Temple, a symbol of the maturity and faith of the Alberta settlement of Latter-day Saints.

Conditions in Western Canada and Card’s Quest for a Place of Refuge

When Charles Ora Card came to Canada, the Dominion of Canada was only twenty years old, the confederation of four eastern provinces to form the new country having taken place in 1867.[3] The sparsely populated land that later became the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan were then part of the Northwest Territories and had been acquired by the Canadian government from the Hudson Bay Company only eighteen years earlier in 1869.

Maintenance of Canadian control of the land north of the 49th parallel was by no means assured. In 1867, the Americans purchased Alaska from Russia. The United States had already established a state in Oregon and a territory in Washington, and, with the purchase of Alaska, the concept of “Manifest Destiny”—that the whole continent was destined to become American—was as strong as ever. Fifty years before Confederation, Canada had been at war with the United States. There were still political tensions between the two nations. Thus, the Canadian government understood the urgent need to take measures to assert sovereignty in the Northwest. By the time Card arrived, the Dominion Land Act of 1872 had already established the pattern for settlement of the Canadian Northwest. The North-West Mounted Police had also been established (1873) with one of its posts located at Fort Macleod.[4] Furthermore, Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald had succeeded in his monumental endeavor of building the transcontinental railway, which was finished in 1885.

While these developments tended to assert Canadian sovereignty of the prairies, what was really needed to prevent US encroachment were settlers. However, the prevailing viewpoint, since John Palliser’s report about the prairies was submitted to Parliament in 1865, was that southern Alberta and southern Saskatchewan, which formed the “the Palliser Triangle,” were too arid to support agriculture. In 1887, large land tracts were leased to ranchers, while railway companies held massive land grants and the aboriginal populations had only recently been relegated to designated reserve lands. The Blood Indian Reserve, adjacent to Cardston, was established in the years following confederation with the signing of Treaty #7 in 1877. Though the Dominion Land Act of 1872 had set up the provisions required for homesteading on government-owned lands, southern Alberta had very few farming settlers.[5]

Charles Ora Card’s Legal Trouble and the Advice to Go to Canada

The immediate impetus for the Mormon settlement in Canada was the legal trouble facing Charles Ora Card of Logan, Utah, for practicing plural marriage, trouble that came because of the Edmunds Anti-Polygamy Act of 1882 and its rigorous enforcement which put in jail and fined many Mormon men practicing polygamy. Card had supervised construction of both the Logan Tabernacle and the Logan Temple, and on the day that the temple was dedicated in 1884 he was called to be the president of the Cache Valley Stake.[15] Card was a successful businessman, having been involved in flourmills, sawmills, and general stores.[16] Card had a total of four wives: Sarah (Sallie) Beirdneau, Sarah Jane Painter, Zina Young Williams, and Lavinia Clarke Rigby. However, Card never had more than three wives at a time because Sallie divorced him and filed a suit against him when she became disaffected with the Church and with plural marriage in 1884. This was before Card took his last two wives.[17] All Mormon men practicing polygamy faced the threat of arrest by US marshals, but that threat was particularly acute for Charles Ora Card, both because of his prominence in the Church and community and because of the suit associated with his divorce.

The threat of arrest increased so much in 1885 that Card was in hiding, moving from house to house, staying with friends and families.[18] It became almost impossible for him to carry out his Church responsibilities or provide for his families.[19] On 26 July 1886, Card was arrested and escorted onto a train for Ogden, where he would face incarceration. In Hollywood style, Card jumped from the moving train, mounted a nearby horse, and galloped away through cheering crowds to make his escape.[20]

In September 1886, with wagons already packed for the family to migrate to Mexico,[21] Card sought approval from the President of the Church, John Taylor. Taylor surprised Card, advising against going to Mexico, saying, “No. I feel impressed to tell you to go to the British Northwest Territories. I have always found justice under the British flag.”[22] John Taylor had been born in England and joined the Church in Toronto in 1836. His counsel at this pivotal moment, based on his positive experiences in England and in Canada, changed Card’s plans and eventually led to a permanent Mormon presence in Canada.

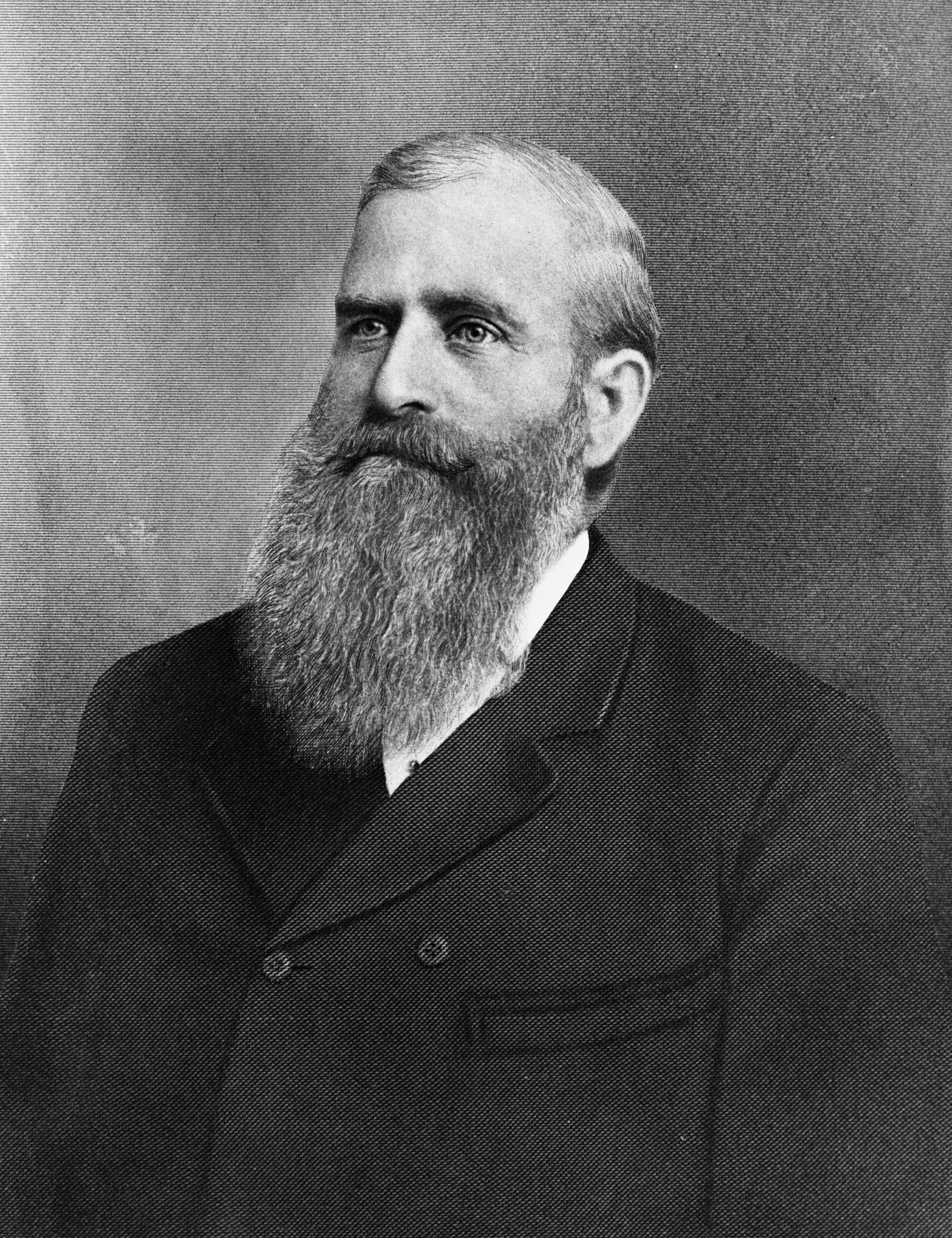

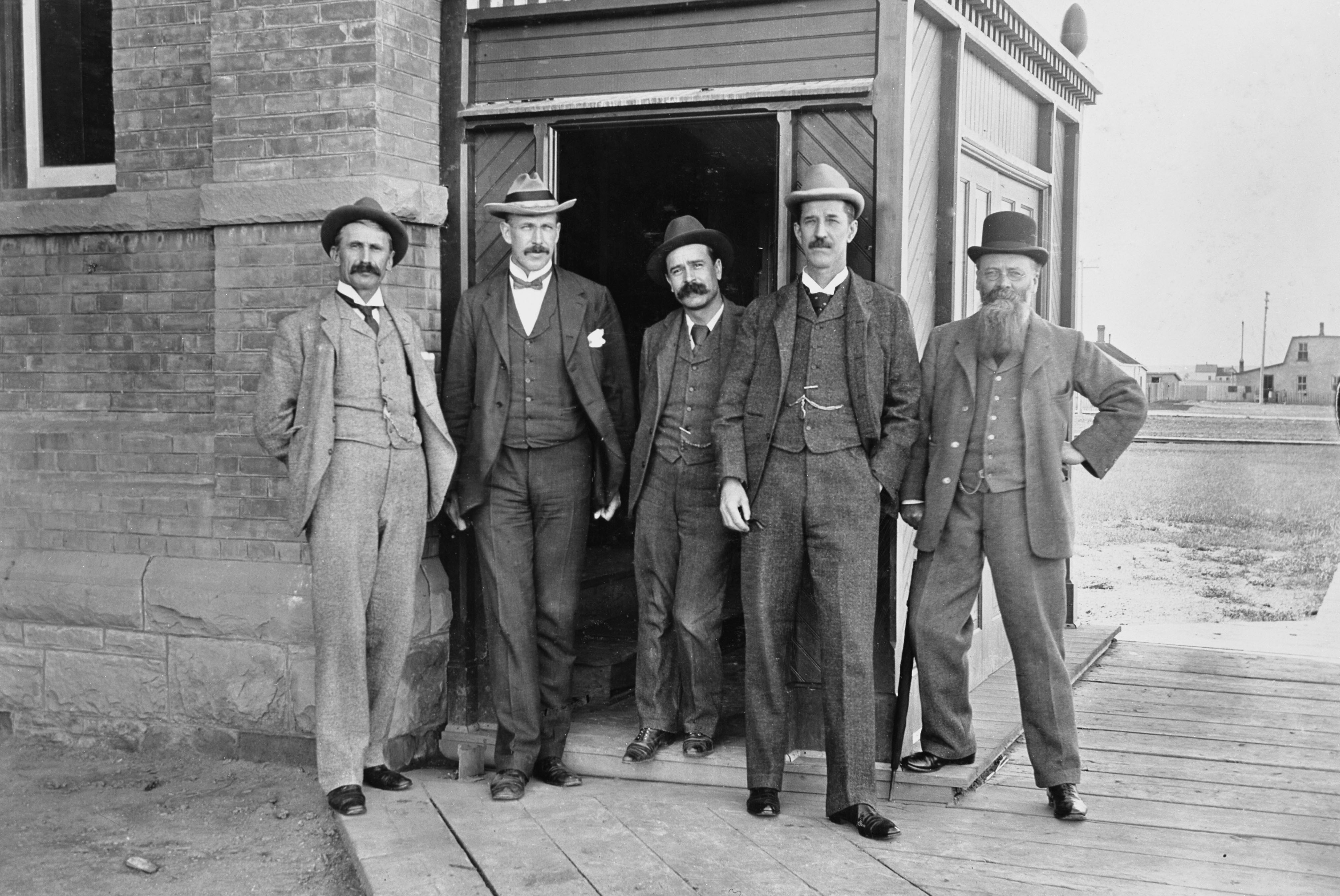

Charles Ora Card led the first group of Mormon settlers to Canada in 1887, where they settled at Lee Creek. (Glenbow Archives NA-1759-1)

Charles Ora Card led the first group of Mormon settlers to Canada in 1887, where they settled at Lee Creek. (Glenbow Archives NA-1759-1)

An Exploration Mission to Canada

A few days later, on 14 September, Card embarked on a Canadian exploration mission with two men who were called to accompany him—James W. Hendricks and Isaac E. D. Zundell. They travelled west by horse and train through southern Idaho up to the area east of Boise, then north through eastern Oregon, and up through eastern Washington state to Spokane. At Spokane, Card and his travelling companions were nearly arrested. As they lay in bed at their hotel room late at night, they heard men outside their door demanding access to the room in search of the “renegade Mormons.” The innkeeper denied the request, preferring to wait until morning. In his journal, Card wrote, “As I lay reflecting over the probabilities of being arrested in the morning, the thought struck me to ask the Lord to cause the party or parties to sleep long enough for us to pack up and get out of the way.” Card’s prayer was answered, and he and his companions were able to leave in the morning undisturbed. They entered British Columbia east of Osoyoos Lake on Wednesday, 29 September 1886. The recent threat of arrest probably made them even more conscious of the refuge Canada offered. As Card recorded: “We . . . crossed the Brittish line and for the first time in my life placed my foot upon the soil of Brittish Collumbia. . . . As we passed the stone monument that designates the line, I took off my hat, swung it around and shouted in Collumbia We are free.”[23]

On Sunday, 3 October 1886, near Osoyoos Lake, the three men held the first known sacrament meeting in western Canada. Card left this record of that meeting, which suggests once again their sentiment that Canada would provide the Saints a place of refuge:

Our prayer is constantly [“]Father direct us by revelation that we may seek the right place.[”] Up to the present we have not had a cross word in our little trio but have night and morn invoked the blessings of God upon us in seeking a haven of rest for the persecuted and imprisoned. . . . We concluded we would hold a meeting today . . . and administered the sacrament. . . . In my [opening] prayer, I Invoked the blessings of God upon the Land and water that it yet would be a resting place for the afflicted and oppressed of the sts [Saints].[24]

Card and his associates found that nearly all the land in that part of British Columbia was already leased in large tracts to ranchers. However, only three days after their sacrament meeting, they met an old mountaineer who told them about the vast buffalo plains east of the Rocky Mountains. Card was deeply impressed with what the man said. Then, reportedly, Card pulled his companions together, put his arms around them, and said, “Brethren, I have an inspiration that Buffalo Plains is where we want to go, that if the buffalo can live there, so can the Mormons.”[25]

Card and his two companions headed further north through the Okanagan Valley, passing through Kelowna, and headed west to Kamloops. Card’s journal tells of selling their horses and paying the lofty sum of $87.60 to board a train for Calgary.[26] After some difficulty, due to arriving in Calgary during a snowstorm, they obtained horses for the rest of their journey and headed south to explore more land for settlement. On Saturday, 23 October, they arrived at Stand Off,[27] and on Sunday, they walked along the Waterton River about two miles west, knelt down, and “dedicated the Land to the Lord for the benefit of Israel both red and white.”[28]

On Monday, 25 October 1886, they returned to their horses and rode south, camping overnight at the “Junction of Lees Creek and St. Marys River [sic],”[29] near the present-day town of Cardston. The next day, the three men started south toward Utah. They finally arrived home on 17 November—their mission to find a place for the Saints having lasted over two months.

It is interesting to note that, while faithful on the exploration mission, neither Isaac Zundell nor James Hendricks chose to settle in Canada. While Card certainly saw potential in the new land, the idea of travelling a thousand miles, leaving wives and children, homes, farms, kindred, and friends behind, to conquer an untamed land in a northern clime was not appealing to everyone.

Recruiting Settlers

After his exploration to Canada, Card returned to Utah to rejoice with his families. Immediately on his arrival, he was busied with family needs, his Church calling, and the urgency of hiding from marshals. Still, Card took every opportunity to speak of the possibilities for a Canadian colonizing mission.[30] In a report he sent to Church President John Taylor, Card presented a list of forty-one men who had told him they would be willing to go to Canada.[31] However, many of them soon backed away from their promise, and Card felt dismayed and alone. On 4 March 1887, Card met with Apostle Franklin D. Richards and told him of his plight of having very few people actually willing to go to Canada. Elder Richards’s reply was insightful, prophetic and encouraging:

He [Richards] stated you can say to them you are going and if your numbers are reduced the[y] will be like the Armies of Gideon and of the right stripe.[32] He encouraged me much and told me if I went I would be a founder of a city and do a good work as a pioneer of a new country and should be known of my good works. He Blessed me as he bade me adieu.[33]

This was the beginning of a pattern for Charles Ora Card. This was not the only time he would have the burden of campaigning to recruit sometimes reluctant settlers to come to Canada. Perhaps one of the reasons for the particularly strong heritage of faith in southern Alberta is that the choice to come in the first place required great faith and strength of character. In other instances, such as after a severe hailstorm in the summer of 1889, the challenges of life in Alberta led some to return to Utah. As Card noted in that instance, “This caused some to become dissatisfied & return to Utah, which had a tendency to weed out many that were not very faithful L.D. [Saints].” Like the armies of Gideon, those who came and stayed were few relative to those who might have, but they were faithful and strong.

The Expedition to Canada

A few Saints gathered in Cache Valley, Utah, in March 1887. Card prepared his family, and, because marshals were watching for him, he disguised himself and secretly headed north with a small group of men who would prepare the way for their families who would soon follow. “They travelled with horse and buggy to American Falls, Idaho, from there to Helena, Montana, by train, and then with teams again to Canada.”[34] Others staggered their departures, believing that if too many men left together they might attract the notice of marshals.[35] On 16 April 1887, Card crossed the border, and he and his fellow travelers spent the next several days in making contacts with the North-West Mounted Police, paying the required duties on imported equipment at the Customs House at Fort Macleod, and making inquiries about obtaining land. They were unsuccessful in getting permission to settle on the land leased by the Cochrane Ranch near Standoff (most likely the land they had dedicated the previous fall), though, interestingly, this land later came into LDS hands when the Church purchased the Cochrane Ranch in the early 1900s. In 1887, however, the vanguard group had to continue looking for a settlement site. The ranching economy was already established, and, though the population density was extremely low, there was very little land actually available to settle. They felt fortunate to find an abandoned lease in the area of Lee Creek,[36] and considered this as a location to settle. This site was appealing because of the creek and because of its proximity to the Blood tribe, for whom these pioneers felt a special sense of mission because of the Book of Mormon promises to them.[37]

The Cardston Settlement, 1887–1900

On Tuesday, 26 April 1887, Card wrote in his journal, “This evening we voted unanimously that Lee Creek was the best location at present and decided to plant our colony thereon.”[38] On 3 May, Card and his fellow settlers plowed the first furrow, and the following day, they planted onions, lettuce, carrots, beets, radishes, and potatoes. The settlers later planted oats and more potatoes. Card called this his “Pioneer garden.”[39]

The next day, Card began the long, rugged trek south toward Helena to meet his wife Zina who was travelling in a wagon toward Canada along with seven other families, twenty-six cows, and sixteen horses. It was near the town of Boulder, Montana, about halfway between Helena and Butte, where Card had a joyful reunion with his wife, his stepson Sterling, and little son Joseph on Thursday, 12 May 1887.[40] Difficulties accompanied them the entire way, but after nineteen days, they finally arrived in Canada. Card wrote:

Wednesday, June 1, 1887 Today we resumed our march and about 9 A.M. we crossed the north fork of the Milk River [in northern Montana] in a rain storm which lasted about an hour and about 10:30 A.M. we crossed the Boundery line between the Brittish possessions and the United States, halted and gave three cheers for our liberty as exiles for our religion.[41]

This view of the stone cairn near the US-Canadian border shows the terrain over which the early Mormon pioneers travelled as they entered Canada. (Jack Stone)

This view of the stone cairn near the US-Canadian border shows the terrain over which the early Mormon pioneers travelled as they entered Canada. (Jack Stone)

Beginnings of a Settlement

The next morning, on 2 June, the camp awakened to see four inches of snow on the ground. This must have been a powerful reminder that nature would pose challenges for this brave band of pioneers. They soon began to press forward toward their settlement site. But first, they had to cross the St. Mary River.[43] By the evening of 2 June, the river was so high and fast flowing that they could not cross it. Card counselled the company to “ask the Lord [to] open the way that we might cross the River in safety. We all made it the burthen of our prayers in public & secret.”[44] Their prayers were miraculously answered. The next morning, according to Card, “the stream fell about 18 inches and which just allowed us to cross safely.”[45] According to her account of the same incident, Jane Woolf Bates recorded that, as soon as the seven wagons, livestock, and people were safely on the other side of the river, it began to rain again and the river rose again to its former high level.[46]

Later that day, on Friday, 3 June 1887, Charles Ora Card and his pioneer party arrived at the site along Lee Creek. They set up tents to accommodate their “41 souls, 12 heads of families, 8 with their wives and children.” They were finally home! On Sunday, 4 June, they all gathered into a fourteen-by-sixteen-foot tent to hold a sacrament meeting.[47] A few more families from Utah joined them that first winter, and the first two babies, Zina Alberta Woolf and Lee Ora Matkin, were born in December 1887. Fifteen of the sixteen men in the colony that year were polygamists, many of whom had been in hiding, unable to attend meetings or live openly with their families for some time.[48] Uncertain of the terms on which they might establish themselves in Canada, each came with only one wife.

The new settlers in Canada began plowing fields and planting wheat, oats, and alfalfa. The weather was stormy and difficult for the pioneers but favourable for crops, and the “garden seeds came up in a luxuriant manner.”[49] This colony was unusually blessed with experienced pioneers, many of whom knew from firsthand experience how to settle a new land. The pioneers went about building their colony in a most systematic and productive way. In just the first year, they pioneered roads to get timber from the west, opened a coal bed to mine coal, built and plastered log cabins for their homes, made shelters and corrals for their animals, built a community building that also functioned as a school or church, fenced many acres of land, and made the difficult trek to and from Lethbridge to buy supplies.[50] The Mormons established mutually supportive relationships with their neighbours, inviting local ranchers and police to their Dominion Day celebrations and other parties and events.[51] Card worked hard to establish relationships with Mounties, ranchers, First Nations people, the postman, customs officers, guides, and businessmen in Lethbridge, including perhaps his most important acquaintance, Charles A. Magrath.[52]

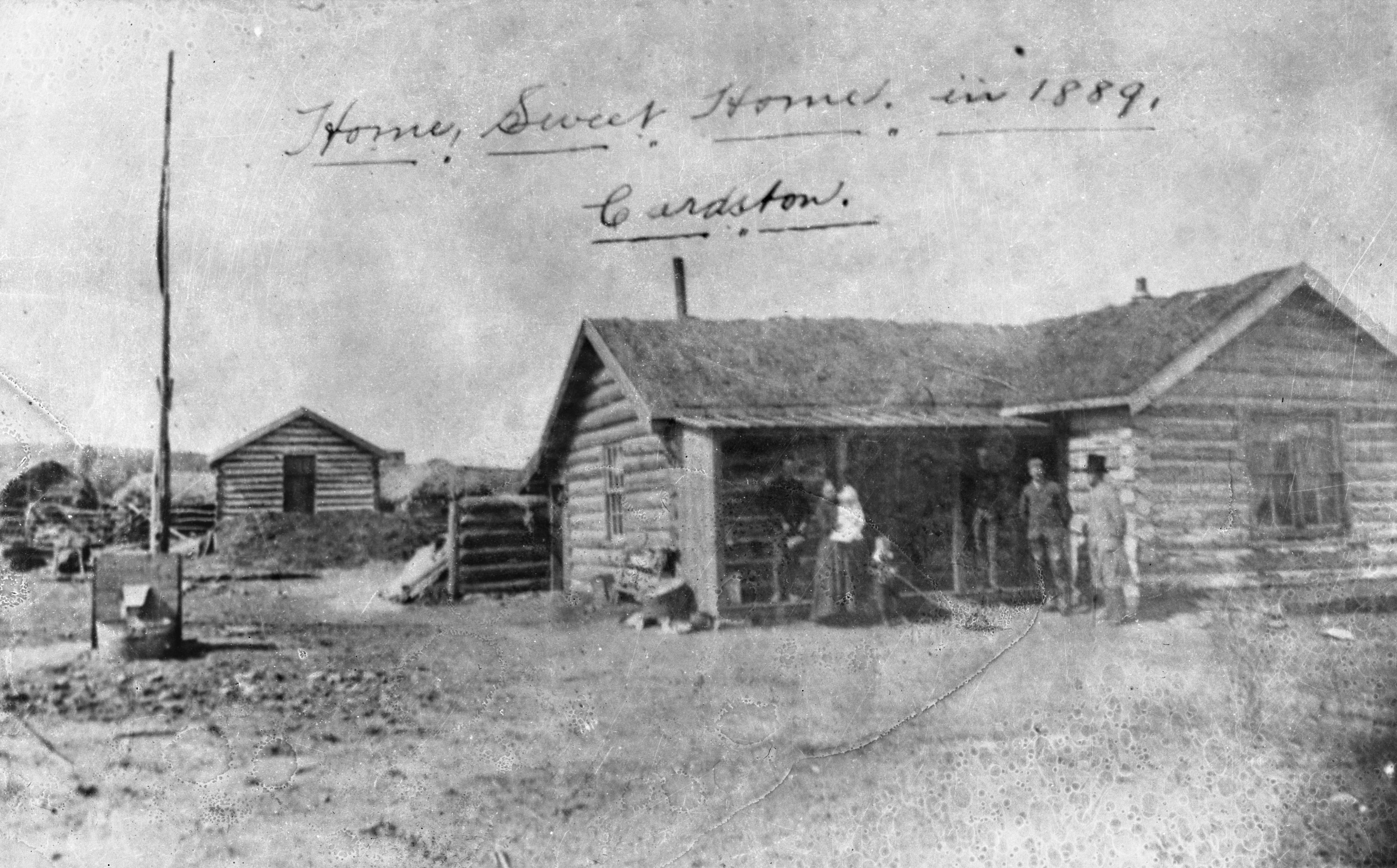

Card Cabin. Charles O. Card, after arriving in Alberta in 1887, built this log cabin in Cardston, where he lived with his wife Zina, a daughter of Brigham Young. It was in this cabin that he and Zina hosted and entertained many government and Church officials and other visitors. (Glenbow Archives NB-3-1)

Card Cabin. Charles O. Card, after arriving in Alberta in 1887, built this log cabin in Cardston, where he lived with his wife Zina, a daughter of Brigham Young. It was in this cabin that he and Zina hosted and entertained many government and Church officials and other visitors. (Glenbow Archives NB-3-1)

It did not take long for the pioneers to learn the peculiarities of the southern Alberta climate, including chinook winds. On 23 January 1888, the day they were plastering the log cabin school, Card recorded that the thermometer registered –20˚F in the morning but showed 40˚F by 1 or 2 p.m. He further wrote, “Although we were enjoying 8 inches of snow It was all gone and the Boys played ball on the Prairie on the 26th.”[53] Mild, pleasant weather seemed to alternate with stormy, freezing weather during the winter,[54] but the faithful pioneers made the best of all kinds of weather, taking advantage of when the rivers were frozen to explore and travel on routes that were otherwise difficult to travel.

Card provided spiritual leadership as much as temporal leadership. He turned to prayer in difficult moments, such as when some wagons loaded with supplies were nearly lost, and the lives of the men and horses along with them, while crossing the St. Mary River in July 1887.[55] When the men were worried about providing for their families, he offered an inspired promise that they would be able to get work, and they soon had jobs haying on the Cochrane Ranch.[56] At each moment of difficulty, Card responded with faith, writing on one occasion in what was a common theme for him, “The Lord has always provided for our wants and certainly we can trust him in the future.”[57]

Early Prophecies of a Temple

The colony felt the spirit of prophecy from the very beginning. On 19 June 1887, less than three weeks after the main company’s arrival, Sunday School superintendent Jonathan E. Layne wrote in his journal about a Sunday School meeting where he spoke. His account is as follows: “While speaking, the Spirit of Prophecy rested upon me and under its influence I predicted that this country would produce for us all that our Cache Valley homes and lands had produced for us, and that Temples would yet be built in this country. I could see it as plain as if it was already here.”[58]

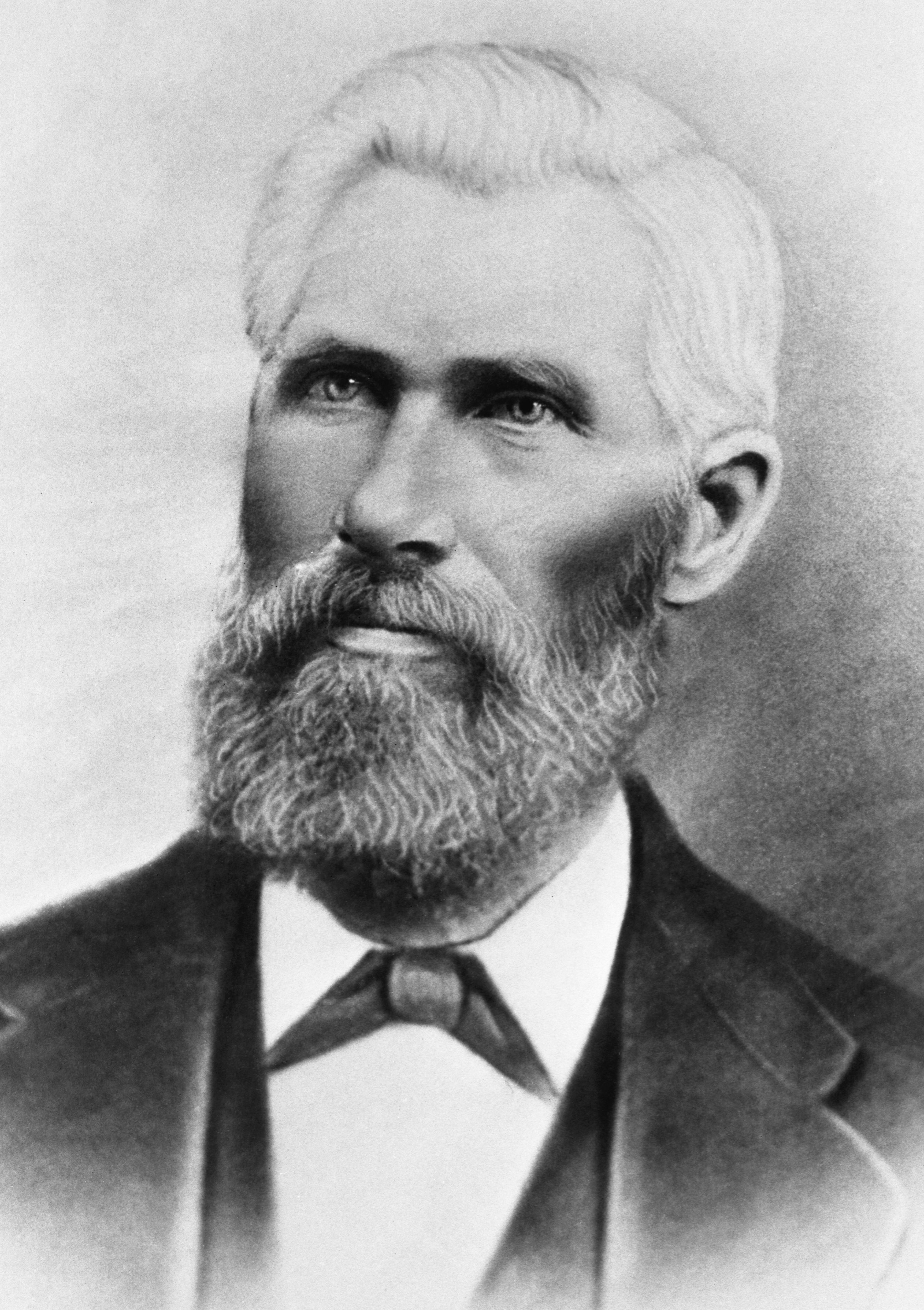

Jonathan E. Layne was one of the original settlers in Cardston and was serving as Sunday School superintendent when he made a remarkable prophecy about a future temple in Canada. (Glenbow Archives NA-114-5)

Jonathan E. Layne was one of the original settlers in Cardston and was serving as Sunday School superintendent when he made a remarkable prophecy about a future temple in Canada. (Glenbow Archives NA-114-5)

In October 1888, a year after the colony was founded, two Apostles, Francis M. Lyman and John W. Taylor (son of Church President John Taylor), came to visit the Saints. A conference was held on 7 October in which the Card Ward of the Cache Stake was created, with John A. Woolf as Bishop.[59] Charles O. Card was still serving as president of the Cache Valley Stake in Logan, Utah, at that time, and the Card Ward became part of that stake.

On Monday, 8 October, Card took the Apostles and others with him up the hill on the west, pointing out the survey of the town site. When they reached the block set aside for the tabernacle, they formed a circle of seven men and seven women, and Apostle Taylor offered a dedicatory prayer, dedicating the land to “the habitation of the saints.”[60] During the prayer, he is recorded as saying, “I now speak by the power of prophecy and say that upon this very spot shall be erected a temple to the name of Israel’s God and nations shall come from far and near and praise His high and holy name.”[61] This prophecy was astounding! The tiny settlement was only one year old, yet a temple was dedicated only thirty-five years later on the very spot.

Students and teachers, Cardston Public School, 1895. Education of children was an early priority despite pioneer conditions. (Glenbow Archives NA-147-2)

Students and teachers, Cardston Public School, 1895. Education of children was an early priority despite pioneer conditions. (Glenbow Archives NA-147-2)

Delegation to Ottawa[62]

Only a few days later, Charles Ora Card, accompanied by the two Apostles, left on a landmark 4,000-mile round trip to Ottawa, via the Canadian Pacific Railway, to meet with government leaders, including Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald and Edgar Dewdney, Lieutenant Governor of the Northwest Territories. It was important for Card and his associates to ascertain whether the Canadian government was agreeable to the establishment of a Mormon colony and to clearly establish the terms on which they could settle in Canada.

On Friday, 9 November 1888, Card and Apostles Taylor and Lyman met with Dewdney, requesting government permission for the Saints to purchase land and settle in Canada. They asked for permission to purchase coal lands and to use timber and rock for domestic purposes. They discussed the use of water for milling, manufacturing, irrigation, and other purposes. They also addressed the use of tithing by the Church and asked permission to carry out this principle.[63]

The next day, Saturday, 10 November, they met with Sir John A. Macdonald, Prime Minister of Canada, and reviewed the items that had been presented to Dewdney the day before.[64] They also presented their most important request—and least likely to be accepted—permission to practice plural marriage in Canada. As Card recorded:

Bro. Lyman appealed to Him in behalf of those who had Entered in to the covenant of Eternity of Marriage whom at this date were suffering in prisons of the U.S. besides being heavily fined and not allowed to mingle with their families with the repetition of fines and imprisonment and it had become very Grievous to bear. He then asked Sir John if he did not think that this Government would give them a resting place upon their Soil for they were the choicest of men and had many sons and ample means to sustain themselves and would bring wealth into the Dominion. Then Bro. John W. Taylor Explained further the great principle of plurality of wives as viewed by the sts [Saints] and as practiced in its purity for the purpose of observing God’s Laws in multiplying and replenishing the Earth.[65]

The Prime Minister heard them out and seemed to them somewhat sympathetic to their plight.[66] They also obtained audiences with the Post Office General, the Minister of Agriculture and the Minister of Customs. In these meetings, they asked for postal service, a reduction in customs duties and other favours as well.[67]

The matter of Mormon settlers in the Northwest Territories was tricky for the Government of Canada. On the one hand, they had just built the Canada-Pacific Railway at an enormous expense in the hope of asserting Canadian sovereignty on vast prairie land between the provinces of Manitoba and British Columbia. However, since the government had had very little success encouraging settlement, and since the land nearest the border was arid and considered by many to be unfit for agriculture, it was an incredible boon to the government to have such a capable, experienced, and community-oriented people with a grudge against the United States willing to settle. On the other hand, polygamy was extremely unpopular, and the government could not be seen as doing favours for polygamists and could not possibly allow its practice without absolutely assuring a loss at the polls in the next election. The Minister of Agriculture explained to Card that he had tried to openly assist the Mormon settlement, “but it had risen such a hue & cry from the tradesmen that popular clammer [sic] forbade it.”[68]

Hence, Sir John A. MacDonald, Edgar Dewdney, and their associates had to walk a fine line. In essence, their response to the Mormon petitions was to allow all items to be settled according to existing law. The Saints were allowed to buy a half section of crown land for the town site, but they could not obtain additional crown lands except by following existing homestead requirements of the Dominion Land Act of 1872.[69] They were advised of existing laws which allowed for free use of water and stone (except when stone was quarried, in which case there was a 5 percent tax),[70] and the need to obtain a permit to use timber.[71] They would be subject to the usual taxes, duties, and tariffs, but they were advised how to minimize these obligations within existing law.[72] Vague support was given for establishing a postal service.[73]

Perspectives on Mormon Polygamy in Canada

Their request to bring their plural wives to Canada was denied, and within three years the government passed more stringent laws against polygamy.[74] Card gave his promise to Sir John A. Macdonald that Mormon men would not keep more than one wife in Canada.[75] Two years later, an accusation of the practice of polygamy and cohabitation among Mormon settlers reached Ottawa, and Deputy Interior Minister A. M. Burgess relayed the accusation to Card. Card replied “that our good faith in this matter has not been broken [emphasis by Card].”[76] He went on to say, “I desire most earnestly that your department make such investigations as you deem necessary through the Police or otherwise that the Mormon Colony on Lees Creek may be freed from the onus they are branded with by those who delight in misrepresentations against an inoffensive people.”[77] Card did his best to ensure that the Mormon settlers remained true to this promise and the practice of having two wives in Canada was extremely rare.[78]

Children of Thomas Rowell Leavitt, one of the first settlers in Cardston, and his wife Ann Eliza Jenkins Leavitt. Front, left to right: Edwin Jenkins Leavitt, Edward Jenkins Leavitt; seated, left to right: Ann Eliza Leavitt, Thomas Rowell Leavitt Jr., Martha Ellen Leavitt; standing at back, left to right: Mary Emmerine Leavitt, William Jenkins Leavitt, Franklin Dewey Leavitt, Louisa Hannah Leavitt, and Sarah Leavitt. Thomas Rowell Leavitt is one of three men known to have had two wives in Canada, though it was only for a short time from 1890 until his death in 1891. Of twenty-three Leavitt children who lived to adulthood, twenty-one lived in Canada as adults, with nineteen of these staying in southern Alberta until their deaths.[79] The settlement of Leavitt was named after Thomas Rowell Leavitt. (Daughters of Utah Pioneers)

Children of Thomas Rowell Leavitt, one of the first settlers in Cardston, and his wife Ann Eliza Jenkins Leavitt. Front, left to right: Edwin Jenkins Leavitt, Edward Jenkins Leavitt; seated, left to right: Ann Eliza Leavitt, Thomas Rowell Leavitt Jr., Martha Ellen Leavitt; standing at back, left to right: Mary Emmerine Leavitt, William Jenkins Leavitt, Franklin Dewey Leavitt, Louisa Hannah Leavitt, and Sarah Leavitt. Thomas Rowell Leavitt is one of three men known to have had two wives in Canada, though it was only for a short time from 1890 until his death in 1891. Of twenty-three Leavitt children who lived to adulthood, twenty-one lived in Canada as adults, with nineteen of these staying in southern Alberta until their deaths.[79] The settlement of Leavitt was named after Thomas Rowell Leavitt. (Daughters of Utah Pioneers)

However, that does not mean that the principle of plural marriage was denounced by early Mormon settlers. The men who initially settled Cardston had additional wives and children in the United States, and most did their best to stay in touch and provide what limited support they could. Some returned to Utah to visit and provide for their families, especially during semiannual general conferences. Still, a few, despite reproofs from Church leaders, never returned to see the wives and children they had left behind.[80] Despite passing an antipolygamy law in 1890 directed specifically at Mormons, the Canadian government turned a blind eye to this cross-border practice of plural marriage so long as only one wife was present in Canada.[81] Local Mounties were frequently on the lookout for any second wives living in Canada but never succeeded in gathering the evidence to make a case.[82]

Meanwhile, the United States government was passing increasingly punitive antipolygamy laws. Those who practiced plural marriage were subject to fines, disenfranchisement, and imprisonment. The Edmunds-Tucker Act of 1887, which was upheld by the Supreme Court in May 1890, allowed for government seizure of all Church assets over $50,000.[83] This would have resulted in temples and meetinghouses falling into the hands of the state. At this time, Church President Wilford Woodruff received a bleak vision of what would happen if the Church did not comply with these laws.[84] As a result, in September 1890, Wilford Woodruff issued a Manifesto counselling the Saints to “refrain from contracting any marriage forbidden by the law of the land.”[85]

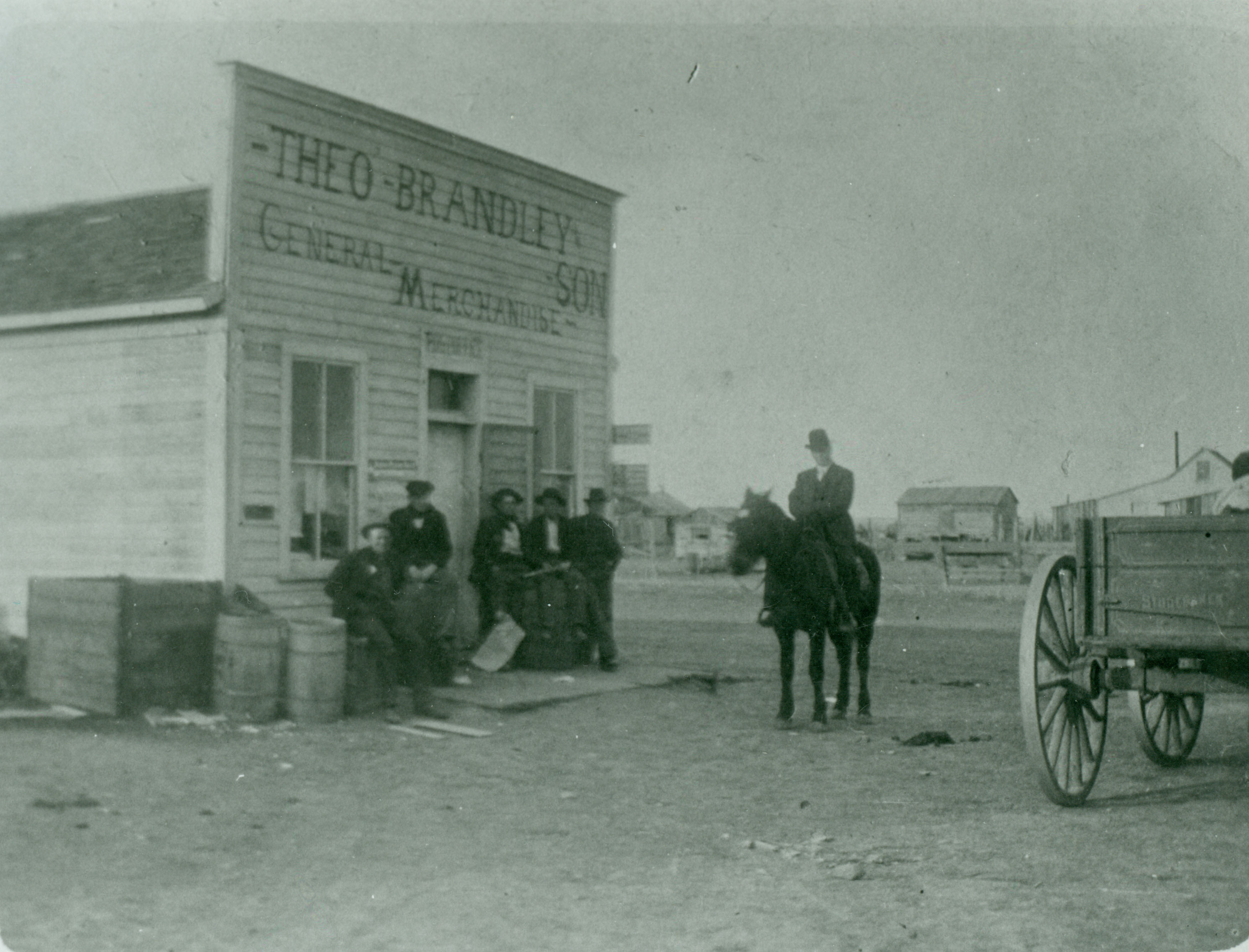

This Manifesto largely ended the contracting of new plural marriages within the United States, though most men continued to live with and support their existing families for the duration of their lives well into the twentieth century.[86] However, this first Manifesto was not necessarily considered a renunciation of the principle of plural marriage. After 1890, a lesser number of plural marriages were quietly solemnized outside the United States, including in Canada and in Mexico. Individual Apostles, including John W. Taylor and Matthias Cowley, who were frequently in Canada, understood themselves to be authorized to perform plural marriages outside temples when outside the United States.[87] For example, Theodore Brandley, the first bishop of Stirling, left two wives in the United States, and, shortly after arriving in Canada in 1899, married Rosina Zaugg, who stayed with him in Canada.[88] At the time the Alberta Stake was split in 1903, both of the new stake presidents were counselled by Apostle John W. Taylor to take second wives.[89] Taylor Stake President Heber S. Allen took a second wife, Elizabeth Hardy, in 1903. Their six children were all born in Salt Lake City where she lived.[90] Alberta Stake President E. J. Wood also quietly took a second wife, Adelaide Solomon, sister to his first wife, Mary Ann, in February 1904. Adelaide lived in Salt Lake City, and they had two children.[91] These post-1890 plural marriages were not common.[92] There is evidence that there may have also been people during this period who journeyed to Canada from the United States in order to have their plural marriage solemnized, and then they would return home after that.[93]

In the April 1904 general conference, Church President Joseph F. Smith issued a second Manifesto attaching Church disciplinary action to anyone performing or contracting plural marriages.[94] After this time, plural marriages were no longer sanctioned by the Church. Apostle John W. Taylor, one of plural marriage’s most ardent proponents, was unable to accept this Manifesto, and because of this, he was removed from the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in 1905. He was excommunicated in 1911 after it became known that he took an additional wife in 1909.[95] Matthias Cowley also continued to advocate for plural marriage following the Second Manifesto and was disfellowshipped but was later reinstated after admitting his error.[96]

Colony Expansion

The 1888 visit to Ottawa, while disappointing on some levels, provided a clear understanding of how the Mormon settlement stood in relation to the Canadian government. Having been denied the purchase of crown land, Card immediately began negotiations to purchase land from Charles A. Magrath, the land manager for the North Western Coal and Navigation Company. That company had received huge land holdings from the government for building a narrow-gauge railway from Dunmore to Lethbridge and was happy to sell land to Mormon settlers, both because they needed cash from the land and because of the potential added business to their railway and coal operations. Over time, Magrath and Card developed a deep mutual respect for each other. Magrath sincerely admired the LDS people and recognized the value they added to the development of southern Alberta. Over the years, they would have many interactions.

Agricultural Villages and the Plat of Zion

As they did in Utah, the Saints settled in farm villages, reminiscent of the Plat of Zion, organized on a grid with settlers living in the village and farming land outside the village.[97] Agricultural villages allowed the Saints to participate in the full program of the Church with all its recreational, cultural, social, service and spiritual components. It also made education, medical care and community businesses and services more accessible (see chapter 6).[98] The rich community life in the Mormon agricultural villages contrasted starkly against the isolated lifestyle of most prairie homesteaders. Some Mormon settlers homesteaded, but Card encouraged them to move into the settlements after they had met the six-months-per-year, three-year residence required to “prove up” on the isolated homestead land.[99]

Card led out in promoting cooperative industries and businesses, many of which operated under the charter of the Cardston Company (chartered in 1892). In his business endeavors, Card was aided by the considerable inheritance of his wife Zina from the estate of Brigham Young. Among the industries established in Cardston before the turn of the century were a store, a sawmill, a gristmill, a cheese factory, and a creamery. There were also cattle and sheep ranching, pig farming, grain and vegetable farming, hay selling, local irrigation projects, a bank, and a newspaper. “The Cardston Company Ltd. expanded to include a butcher shop, farm implements store, a coal mine, ice business, and a glove, boot and shoe factory.”[100] Often, Card travelled far and wide to obtain the best equipment and expertise and to try and secure financing for these projects—a difficult task. He, and even more so, his wife Zina, invested much of their personal money in Canadian land and in these projects, often at considerable sacrifice. The Church provided funds to support the colony from time to time, and this show of official support probably lent credibility to the colony for potential Mormon settlers. The settlers brought in trees, including fruit trees, shrubs, rhubarb, berries, and flowers to beautify the settlement and add variety to their diet.[101]

Some of the first women in the Cardston settlement, about 1900. Back row, left to right: Elizabeth Hammer, Zina Y. Card, Lydia J. Brown. Middle row, left to right: Catherine Pilling, Rhoda C. Hinman, Mary L. Woolf, Jane Hinman, Sara Daines. Front row, left to right: Mary L. Ibey, Jane Elizabeth Bates. (Glenbow Archives NA 147-4)

Some of the first women in the Cardston settlement, about 1900. Back row, left to right: Elizabeth Hammer, Zina Y. Card, Lydia J. Brown. Middle row, left to right: Catherine Pilling, Rhoda C. Hinman, Mary L. Woolf, Jane Hinman, Sara Daines. Front row, left to right: Mary L. Ibey, Jane Elizabeth Bates. (Glenbow Archives NA 147-4)

In addition, the settlers tackled transportation and communication problems. They soon built a bridge across Lee Creek and the St. Mary River and mapped out a wagon road to Lethbridge. Rail transport continued to expand and improve, and, by 1890, with the completion of the narrow-gauge Great Falls & Canada Railway, it was possible to travel by rail from Utah to Lethbridge, though the trip required layovers and switching railways. In 1892, after a few years of picking their mail up in Fort Macleod and Lethbridge, a post office was opened in Cardston.[102] The Saints also built the telephone line to Lethbridge, and service was completed in 1894.[103]

Reception of Mormons in a New Land

When Mormons arrived in Canada, they were met with a notably negative reception from the national press and from Protestant churches, while receiving a more favourable reception from government and business officials. Anti-Mormon and antipolygamy articles appeared frequently in newspapers around the country, and “the Mormon Problem” was a hot topic for the Methodist and Presbyterian churches.[104] However, the Lethbridge News and the Macleod Gazette frequently came to the defense of the Mormon settlers when they were attacked by newspapers in Edmonton, Calgary, eastern Canada, or elsewhere.[105] Only after the 1888 delegation to Ottawa, when Card, Lyman, and Taylor requested permission to practice polygamy in Canada, did the Lethbridge News temporarily turn on the Saints, condemning the “hideous aspect of polygamists.”[106]

The reception from government and business leaders was more favourable than the national press, though their position against polygamy was clear and unequivocal. The local customs officer, Dr. William Cox Allen, had instructions from the government to “do all he could to encourage our people to settle in this country, which he said he intended to do.”[107] Whenever dignitaries or government officials were in the area, the Mormon settlers reached out, with Card often entertaining the guests in his own home. In 1889, Card hosted the Honourable Mackenzie Bowell, Minister of Customs, and his associates for two days.[108] Bowell returned to Ottawa with such high praise for the Mormon settlers that he was teased that perhaps he would “resign his seat in parliament and join the Saints.”[109] Thomas Shaughnessy, vice president of the CPR, described the Saints as “the most efficient colonizing instruments on [the] continent.”[110] Similarly, irrigation surveyor J. S. Dennis visited the Lee Creek colony in 1888 and wrote, “Any person visiting the colony cannot help being struck with the wonderful progress made by them during the short time they have been in the country, and I may say that I have never seen any new settlements where so much has been accomplished in the same length of time. I am satisfied that they are an exceedingly industrious and intelligent people, who thoroughly understand prairie farming.”[111]

Gradually, Mormon settlers gained greater acceptance, and, by World War I, Canadian nativism was directed toward immigrants from enemy countries as well as visible minorities. Mormons who were white, middle class, and well-educated were no longer the main focus of negative national press. Overall, Canadian Mormons experienced much less prejudice than other ethnic and religious groups settling in Canada, some of whom were subject to restrictive immigration measures and limitations on human rights.[112] Mormons were also accepted better in Canada than in most other countries in that period. Anti-Mormon sentiment did not lead to violence as it did in the American South or Great Britain, and missionary work was not banned as it was in some European countries.[113]

Relations with Aboriginal Peoples

When exploring southern Alberta, Card was very conscious of being in “Indian country.” While near Standoff in October 1886, he wrote, “I saw good wheat and Oats raised here on the Belly River, By the Blood Indians. This would be in the heart of an indian country. . . . Here would be a good place to establish a mission among the Lamanites.”[114] The Book of Mormon, a primary religious text for Mormons, is the religious history of an ancient-American Christian people. Mormons believed that aboriginal peoples were descended from the Lamanite people of the Book of Mormon. They therefore felt an affinity for these peoples and a desire to teach them about their ancestors. Once they settled just south of the Blood Reserve, Card and the other settlers worked to build friendly relations with First Nations people. Card hosted Blood Tribe members in his home and invited them to social events in Cardston.[115] He recorded the following in 1896, with regard to the Cardston Co. store: “We have always kept friendly relations with the Indians & lead out in giving them 100 cents in goods for each dollar & and treated them with the same consideration as white people giving them 16 oz to the lb. in tea, Sugar & coffee while former traders only gave 12 oz to the lb. cheating them in net [weight].”[116] Card met with Chief Red Crow, the Blood chief, in 1894 and satisfactorily negotiated to allow the LDS sheep ranch to use reserve lands.[117] Card even smoked the peace pipe with Red Crow.[118] However, despite Card’s initial assessment, it does not appear that any organized missionary efforts were directed toward the neighbouring tribes until years later.

Growth

The Lee Creek Settlement, renamed Cardston in 1889, grew, and other nearby settlements emerged. Aetna (1888), Mountain View (1890), Beazer (1891), Leavitt (1893), Kimball (1897), Caldwell (1898), Taylorsville (1898), and Wolford (1900) are the settlements that became large enough to have church units.[119] The mid-1890s were a time of limited economic opportunities in Utah, but the opportunities available in the Alberta settlement were quite well known in Utah due to frequent visits back and forth between the Alberta settlement and Utah, as well as the publication of pamphlets[120] about Canada and reports of Alberta Stake conferences in the Deseret News.[121] Card recorded in his journal on several occasions that on his frequent visits to Utah, he answered many enquiries about Canada.[122]

As each community became firmly established, corresponding wards and branches were created. In 1895, although the LDS population in Canada was only about 780,[123] the First Presidency approved Card’s request for the creation of an Alberta Stake, the thirty-fifth stake of the Church, and called him as stake president. By this point it must have been clear the colony would experience continued growth. The creation of a stake itself encouraged growth by adding strength and stability to the settlement. By the end of 1898, the settlements had grown and there were 1597 Saints living in eight communities in the southern Alberta foothills.[124] It should be noted that those who settled in the area in the 1890s were not necessarily polygamists; the primary motivation for settlement for many was economic.

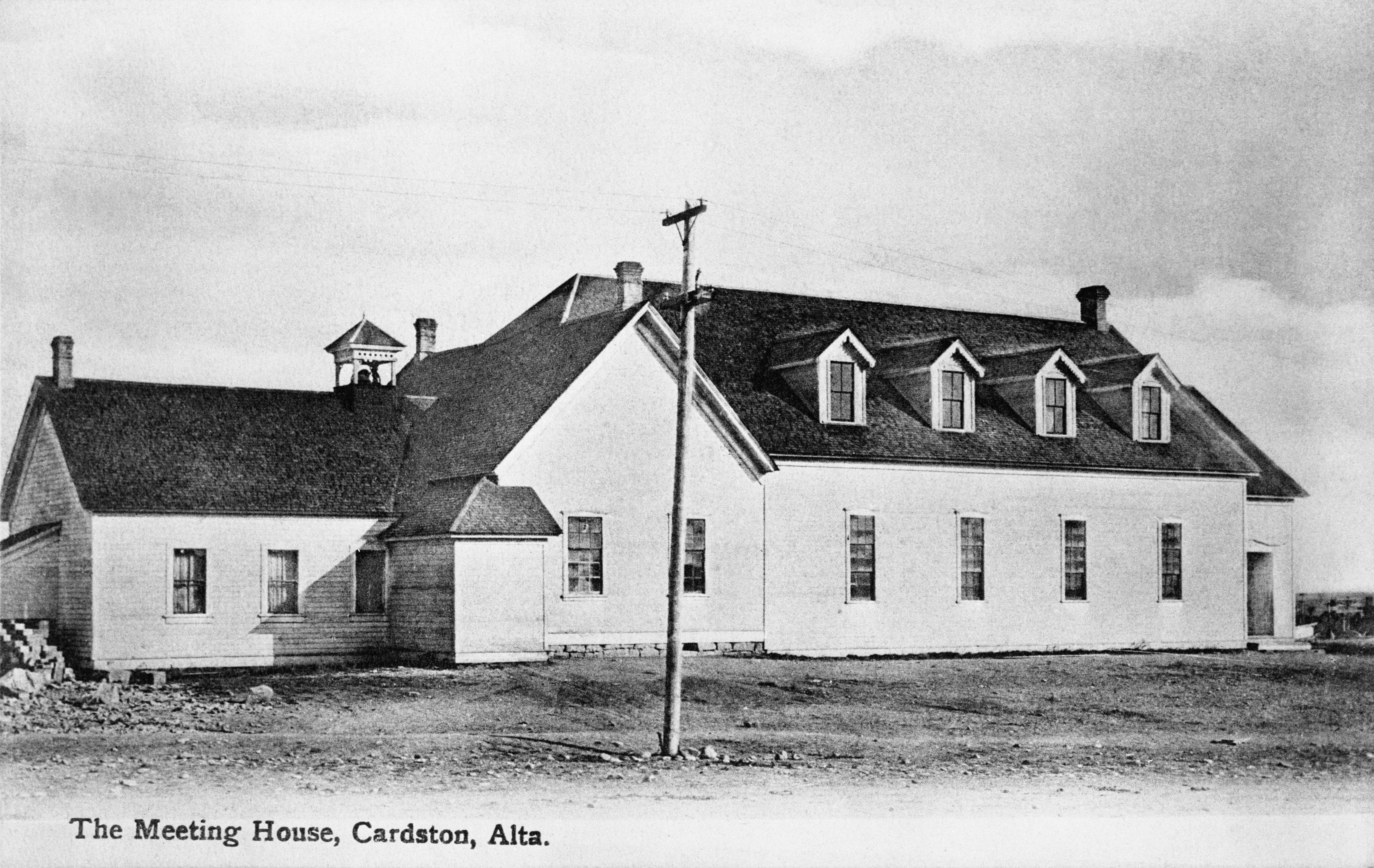

Cardston meetinghouse, 1910. (Glenbow Archives NA-114-19)

Cardston meetinghouse, 1910. (Glenbow Archives NA-114-19)

The Church in Alberta was not just growing in size, but it also experienced a Pentecostal feast of gifts of the Spirit. At many meetings, Saints (usually women) spoke in tongues. Always accompanying this gift was another who was given the gift to interpret tongues. On these occasions, people made prophecies and gave words of blessing and caution.[125] Other people uttered additional prophecies, including some by Card,[126] with Apostle John W. Taylor being mouth of many other prophecies that were later fulfilled.[127] Many times, priesthood holders were called on to administer to the sick, and witnesses reported corresponding healings. The Saints often met together in fasting and prayer to ask the Lord to temper the elements, or to help them in times of need.[128] These spiritual gifts offered hope, joy and consolation to this faithful band of pioneers who felt exiled from their homes and families for choosing to live the laws of God, as they understood them.[129]

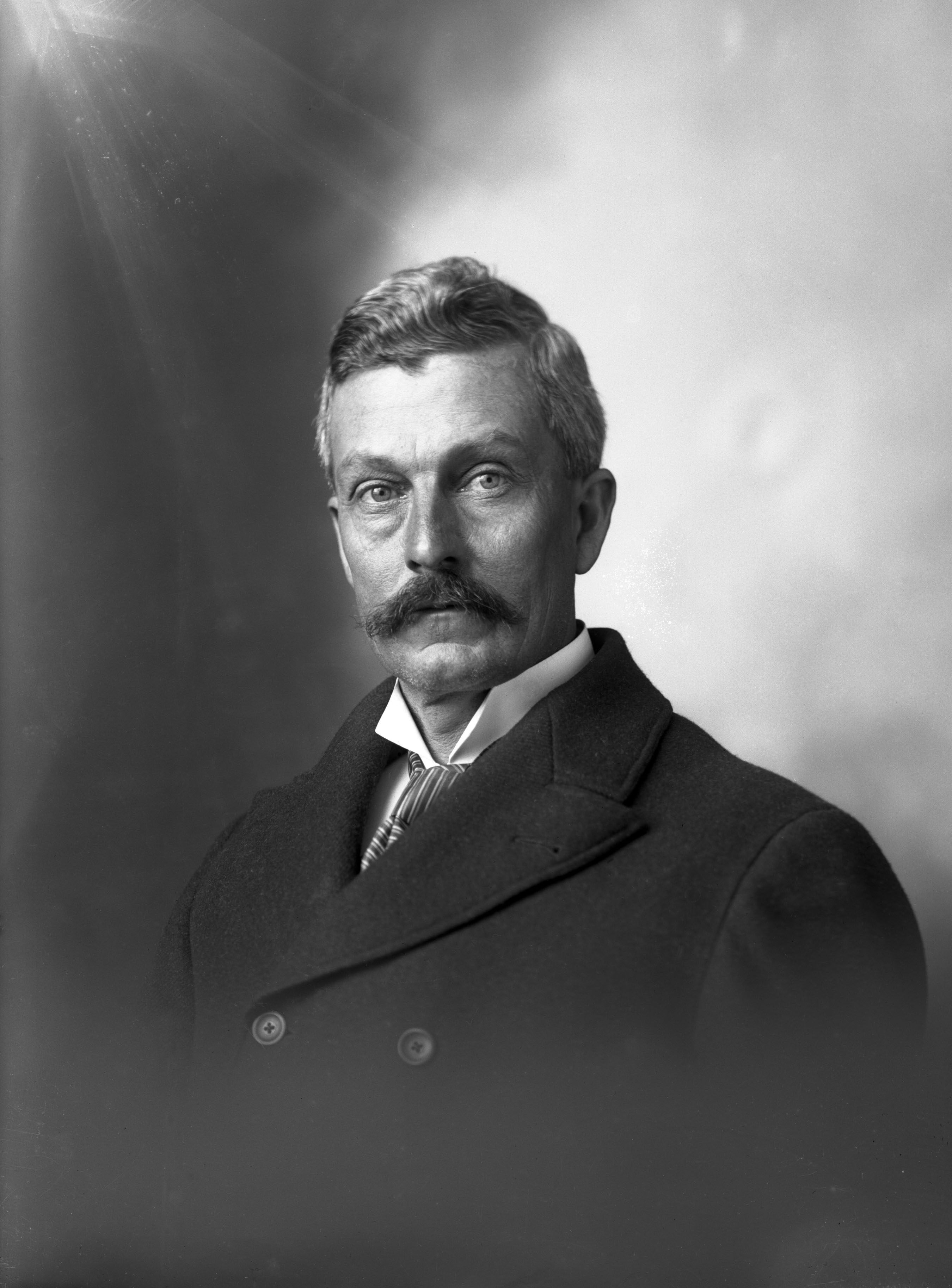

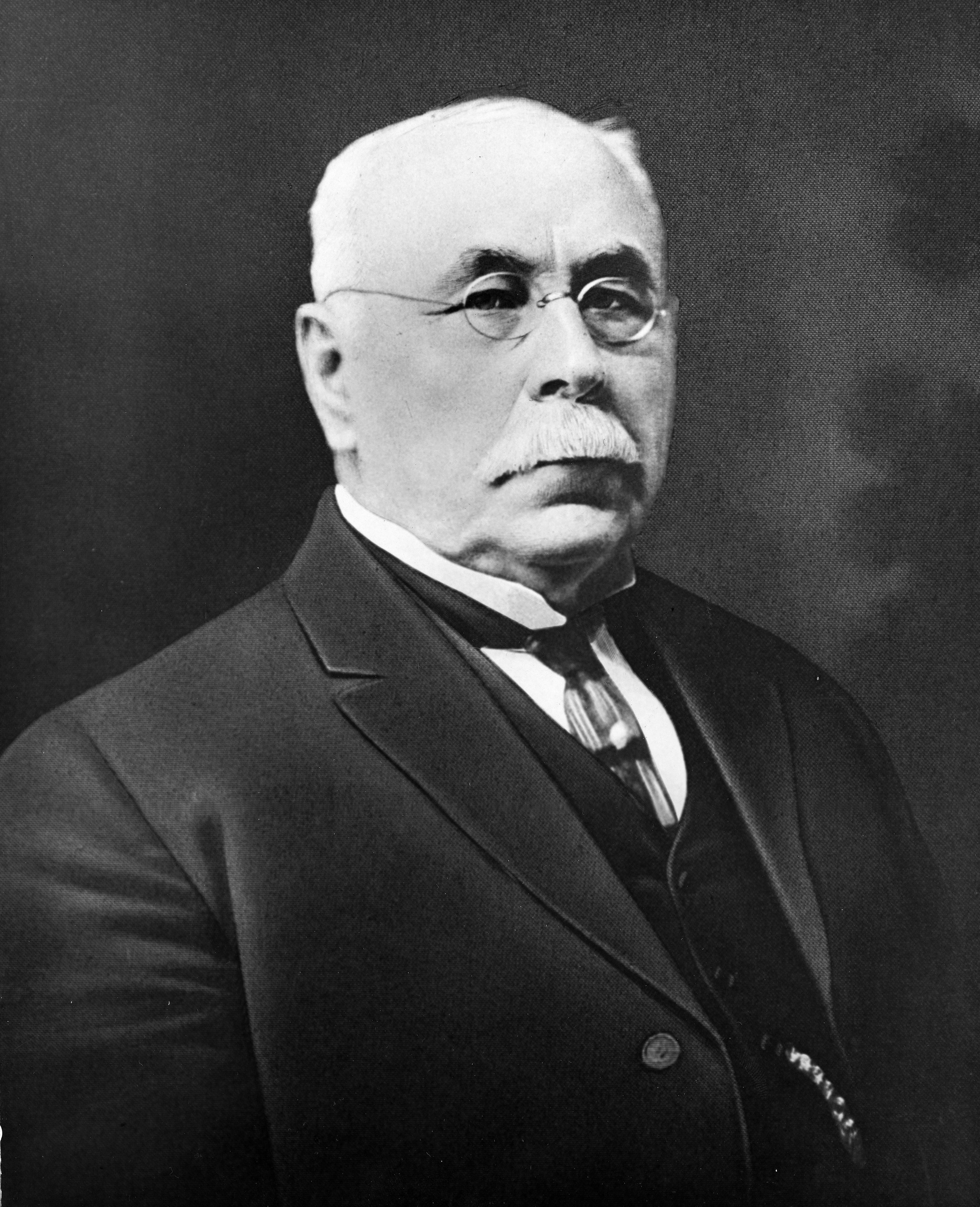

John W. Taylor, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, took a particular interest in the Alberta settlement. He made frequent visits there, where he made prophecies about the future of the settlement and promoted various business enterprises, including irrigation and sugar beets. (Glenbow Archives NC-7-534)

John W. Taylor, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, took a particular interest in the Alberta settlement. He made frequent visits there, where he made prophecies about the future of the settlement and promoted various business enterprises, including irrigation and sugar beets. (Glenbow Archives NC-7-534)

Irrigation and the Beginnings of Magrath and Stirling

Levi Harker’s Vision

Levi Harker first settled in the Cardston area in 1892,[130] where he and his brother Ephraim, both monogamists, pioneered sheep farming under Card’s direction.[131] One day, as Levi was out riding his horse, herding sheep, looking down on a completely uninhabited and untamed prairie landscape, a vision opened to his mind:

As he rode and looked north from his vantage point on the northern slope of the Milk River Ridge, . . . suddenly he felt impelled to stop his horse and look north, when a vision opened to his view. . . . He saw the country criss-crossed with wire fences, divided into fields, prosperous farms; well-travelled roads ran between the section lines; a canal wound its way along the slope of the Milk River Ridge and fields of golden grain were everywhere. Interspersed were green fields of sugar beets or hay. Prosperous farm-steads dotted the fields. On the north bank of Pothole Creek he saw a prosperous town with beautiful trees and comfortable homes. He looked in wonder as he saw beneath the soil rich reservoirs of gas and oil, potential wealth of the future. A voice seemed to say, “You will see all this come to pass and more.” The vision faded— the wind blew in his face, bent the prairie grass eastward as he turned his horse west toward Cardston and home.[132]

In 1899, the vision began to be fulfilled when Levi Harker was called to serve as the first bishop of the new settlement of Magrath. He served in that capacity for thirty-two years and also filled two terms as mayor. So beloved was he for his work in building up that community that he was termed the “father of Magrath.”[133]

The St. Mary Canal-Building Project

God’s hand was in the founding of the communities of Magrath and Stirling. One evidence is God opening this vision to Levi Harker. Another evidence is the miraculous confluence of circumstances that unfolded in the 1890s to bring about the monumental contract between the LDS Church and the Alberta Irrigation Company resulting in the building of the first large-scale irrigation canal in Canada and the LDS settlement of communities in Magrath and Stirling in 1899. When Card and his fellow settlers came to Cardston, they brought with them irrigation experience from the Cache Valley in Utah and immediately recognized the potential for large-scale irrigation projects to turn the arid southern Alberta prairie into productive farmland. As Magrath related, the Mormons “understood irrigation, and Lethbridge being their market town, we were continually told of the wealth that could be created by diverting onto the land the waters running to waste down the rivers.”[134] Card, Apostle John W. Taylor, Richard Pilling, and others promoted southern Alberta irrigation among Canadian officials, potential investors, and the LDS Church over a period of many years before they were able to see the dream of a large-scale irrigation project in southern Alberta.[135]

Soon after the Mormon pioneers settled in Cardston, they began small-scale irrigation projects, even though the Cardston area, being in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, often gets adequate rain for crops. They built at least two irrigation ditches near Cardston. The first was completed on 15 July 1890 but began operation June 1894. It powered the gristmill and irrigated town lots and adjacent farms.[136] A second project, the Pioneer Irrigation Canal, supplied water to eight hundred acres on south side of Lee Creek. Both projects were in operation until 1902, when they were damaged by flooding.[137] The success with these small projects demonstrated to others in the area the potential of irrigation and instilled in them the belief that Mormons were the ones who could do it.

In 1891, with great optimism about the future of irrigation in southern Alberta, Charles Card and John W. Taylor negotiated a contract with Elliott Galt and his land agent Charles A. Magrath to purchase seven hundred thousand acres at $1.00 per acre on condition of providing it with irrigation by 1895.[138] However, there were many obstacles to building a large-scale irrigation project, such as the lack of irrigation law, the company land being located in alternating townships, the feasibility of the project not having been formally studied, lack of investors, reluctance for the LDS Church to get involved, and unwillingness for its members to come and build the canal and settle. It proved impossible to overcome these obstacles within the time frame agreed to, and the contract lapsed.[139]

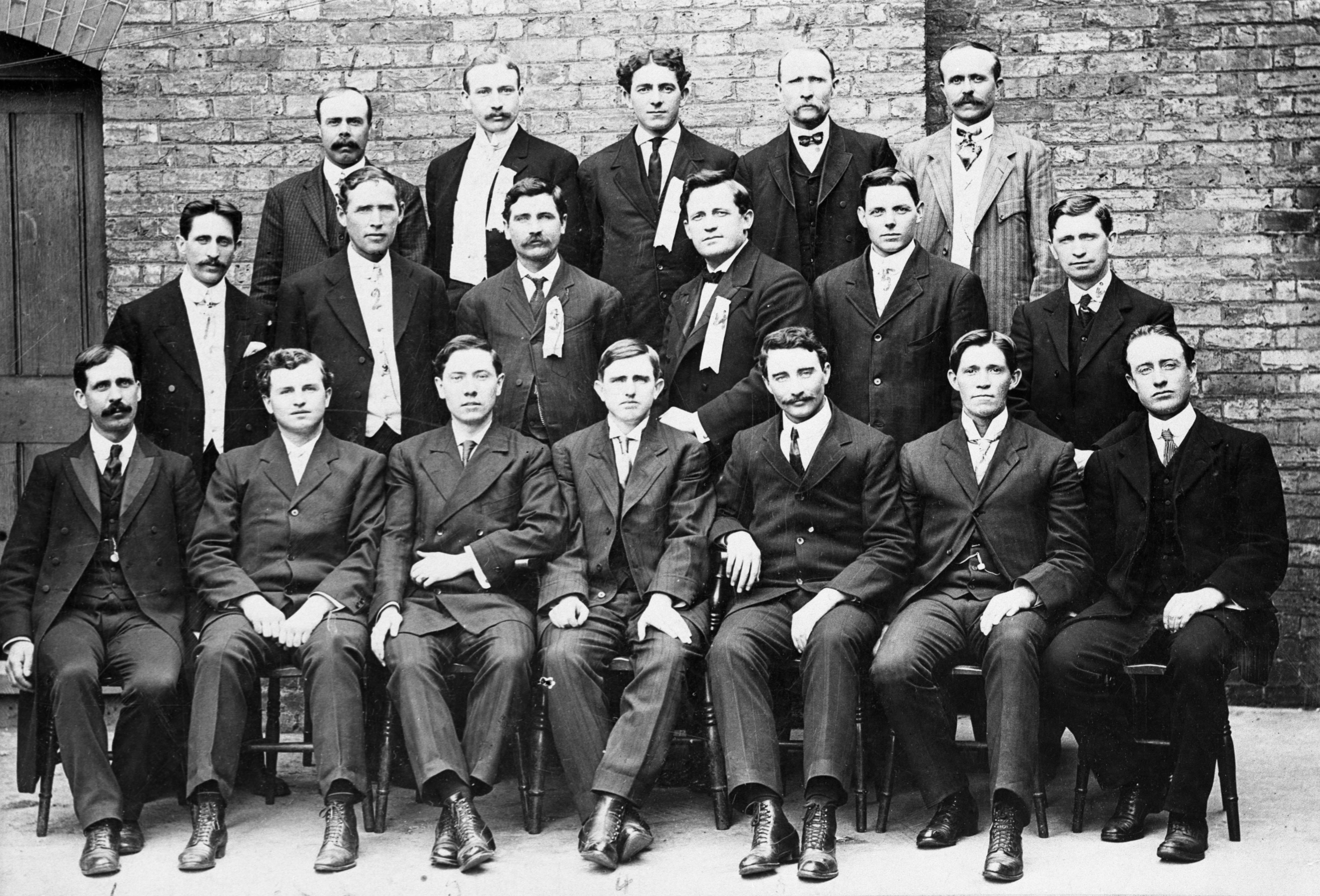

Elliott Galt, son of Alexander T. Galt, a father of Confederation, was a talented and well-educated entrepreneur and colonizer with strong connections in government and with investors. He teamed up with Charles A. Magrath, who later married Galt’s sister. Magrath was an expert surveyor, enthusiastic land developer, and faithful associate. The two men were the key players in a succession of companies that first began mining coal at Lethbridge in 1882.[140] Their second project, completed in 1885, was to build a narrow-gauge railway from Lethbridge to Dunmore to connect with the CPR to provide a market for their coal. They also built the Canadian portion of the Great Falls & Canada Railway, which connected Lethbridge with Great Falls, Montana, by December 1890.[141] For each project, they were awarded massive land grants. Later, when they widened their railways to standard gauge, they were granted even more land. In total, they were granted a whopping 1,592,368 acres of land.[142] Land was usually allocated to railways in alternating sections (a section is one square mile), but they arranged for land in alternating townships (a township is six square miles) so that the blocks of land would be large enough for ranches. However, leasing their land to ranchers was not very profitable. In order to pay their stockholders, they needed to convert their land into money, and the key to making their land habitable was irrigation. After Taylor and Card’s contract lapsed, Galt and Magrath moved to the forefront in promoting a major irrigation project which required the unlikely cooperation of the Canadian government and British and local investors, including the CPR, and the LDS Church.

The Alberta Railway and Coal Company, 1898. Canadian business leaders and entrepreneurs recognized opportunities for profitable partnerships with the industrious Mormon settlers to develop and settle arid lands in southern Alberta. Left to Right: W. D. Barclay, manager of the Bank of Montreal; C. Magrath, ARCC Land Commissioner; G. G. Anderson, consultant; Elliot Galt, ARCC President; and Jeremiah Head, consultant. (Glenbow Archives PD-301-19)

The Alberta Railway and Coal Company, 1898. Canadian business leaders and entrepreneurs recognized opportunities for profitable partnerships with the industrious Mormon settlers to develop and settle arid lands in southern Alberta. Left to Right: W. D. Barclay, manager of the Bank of Montreal; C. Magrath, ARCC Land Commissioner; G. G. Anderson, consultant; Elliot Galt, ARCC President; and Jeremiah Head, consultant. (Glenbow Archives PD-301-19)

Meanwhile, William Pearce, a land surveyor, successful irrigation entrepreneur in the Calgary area, and a senior employee in the federal department of the interior, was promoting to the Canadian Government the idea of expanding irrigation to solve the problems of settling the arid Palliser Triangle. After 1882, in his capacity as inspector of land agencies, he reported directly to Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald. In the early 1880s, he travelled to the US Midwest and Intermountain West, including Utah, where he studied Mormon irrigation and settlement methods. By 1883, he was convinced that Mormon irrigation and land settlement practices should be applied to the Canadian West. He began promoting his ideas in 1885 within the Department of the Interior through speeches and reports, but the federal government did not receive his ideas well, because they worried that his talk about irrigation might actually discourage settlement in parts of the Northwest where there was adequate rainfall for agriculture. He was soon forbidden to speak publicly about irrigation, but he continued to promote irrigation in the government and was ultimately influential in changing the anti-irrigation climate in Ottawa.[143] Pearce, meanwhile, experienced success with some small-scale irrigation projects of his own in Calgary, and this success was a necessary precursor to the St. Mary project, as it encouraged otherwise skeptical investors.[144]

Various councils and lobby groups were established in the 1890s to promote irrigation, and the press in Lethbridge, Fort Macleod, and Medicine Hat[145] also clamoured for irrigation development. However, the Conservative government only began to reconsider its hostility to irrigation when a major drought started in the late 1880s and continued through the mid-1890s, and when Pearce brought to their attention that the Montana government was looking at diverting the water from the St. Mary River to the Milk River for a large-scale irrigation project of its own.[146]

Finally, in 1894, the government enacted legislation based on Pearce’s recommendations, which formalized irrigation law and retained riparian (meaning “adjacent to a river bank”) rights to the government to enable large-scale projects rather than piecemeal development. Beginning in 1895, the government undertook a survey of the St. Mary River area to determine the feasibility of a large-scale project. Later, the Alberta Irrigation Company (the latest Galt company) commissioned a second survey, which improved plans for the canal and greatly reduced expenses by making use of the existing Pinepound and Pothole Creeks as main arteries for the canal.[147]

Two important events proved providential to the irrigation scheme: the election of the Liberal Government of Wilfrid Laurier in 1896 and the appointment of Clifford Sifton from Winnipeg, who was also an enthusiastic promoter of Western Canadian settlement, as Minister of the Interior. After years of the previous government’s unsuccessful lobbying, Minister Sifton quickly agreed to a major concession that was necessary to the irrigation project—the consolidation of railway lands from alternating townships into solid blocks.[148] Without this concession, they would have needed to obtain rights of way and build around other people’s land, which would have made the project inefficient and thereby unrealistic. In addition, Galt succeeded in convincing Sifton to reimburse the cost of the canal survey. This concession, though not very expensive for the government, was enough to signal to investors the support of the government that was needed to satisfy their jitters.[149]

With irrigation law established, surveys completed, lands consolidated, and investors secured, the final step was to find a way to get the canal built and people settled on the land. This is where the Mormons came into the picture once again. Prime farmland in Utah had been parceled out by the 1880s, and Mormon settlements had expanded into fertile valleys throughout the Intermountain West. By the late 1890s, there were many Saints trying to eke out a living on marginal lands. In addition, the Cleveland Panic of 1893 resulted in an economic depression and high unemployment in Utah in the late 1890s.[150] Thus, there was a providential alignment of both a “push” from Utah and a “pull” toward Canada, which brought many settlers.

By 1897, Church leaders were interested in negotiating an irrigation agreement, with their primary goal being to provide employment and economic opportunity for Church members.[151] Initial proposals from C. A. Magrath, which would have provided land at $1.00 per acre provided the Church built the irrigation system, were unsatisfactory to the Church, as the Church was not able to finance the project.[152] Later proposals involved other investors providing capital, with the Church providing labour compensated in equal parts of cash and land at $3.00 per acre. On 14 April 1898, the terms of the contract were decided. Work on the canal was to begin before 1 September 1898, and by 31 December 1899, Mormon contractors were required to have earned $100,000 ($50,000 in cash and 16,667 acres of land). By April 1900, the Church was required to have established two hamlets with 50 families (250 residents) each and to have earned $150,000 ($75,000 in cash and 25,000 acres of land). Labour was to be paid at a rate of 12.5 cents per cubic yard of ordinary soil with rockwork, cement, side hill work paid at a higher rate. The land was to be available in two large, nearly square blocks around each of the two hamlets.[153] Water rights were then available to farmers at a rate of $2.00 per year, which could be earned by working on the canal or the railroad.[154] Though the initial project called for the building of a canal from Kimball to Stirling, residents of Lethbridge protested being left out of the plan and a branch line to Lethbridge was included in the project. Water flowed through the completed canal from Kimball to Lethbridge and Stirling beginning in July 1900.[155]

The communities of Stirling and Magrath were laid out as classic Mormon farm villages, with wide streets oriented north– south and east– west and square blocks divided into lots large enough for a family to keep animals and a garden. Farmland for town residents would be located outside the community. Centre blocks were designated for businesses, recreation, churches and schools.

Mormon Canal Building

The Church gave Charles Ora Card both the authorization and responsibility to encourage settlement and canal building and to make sure the terms agreed to by the Church were fulfilled.[165] It was no small task, but as always, Card relied on his faith in God to help him with the task. In his journal, Card wrote:

April 26, 1898 I met with Prests [Presidents] Cannon & Woodruff [Wilford Woodruff was President of the Church and George Q. Cannon was his Counselor in the First Presidency] & talked Canal matters over about Alberta & the construction of the Canal the Church had engaged to do $100000.00 worth of Labor. . . .I was told in this interview that the Church depended on me to see that the work was done & contract carried out. . . .

I am left to paddle my canoe as before & trust in the Lord as my brethren seem powerless, the Church is behind so much. [This refers to the Church’s financial debt at that time.] I will here record for the sake of my children in the future the Lord has never required anything through his Servants that I have not been able to perform. . . . & all I can do is to be industrious and continue to lean on the Lord. [166]

Construction on the canal began on Friday, 26 August 1898, south of Kimball, with Charles Ora Card digging the first furrow.[167] In 1898, work began to build the headgates to supply the canal with water diverted from the St. Mary River and on the section of canal between Kimball and Spring Coulee.[168] This work was done by Saints already living in southern Alberta.

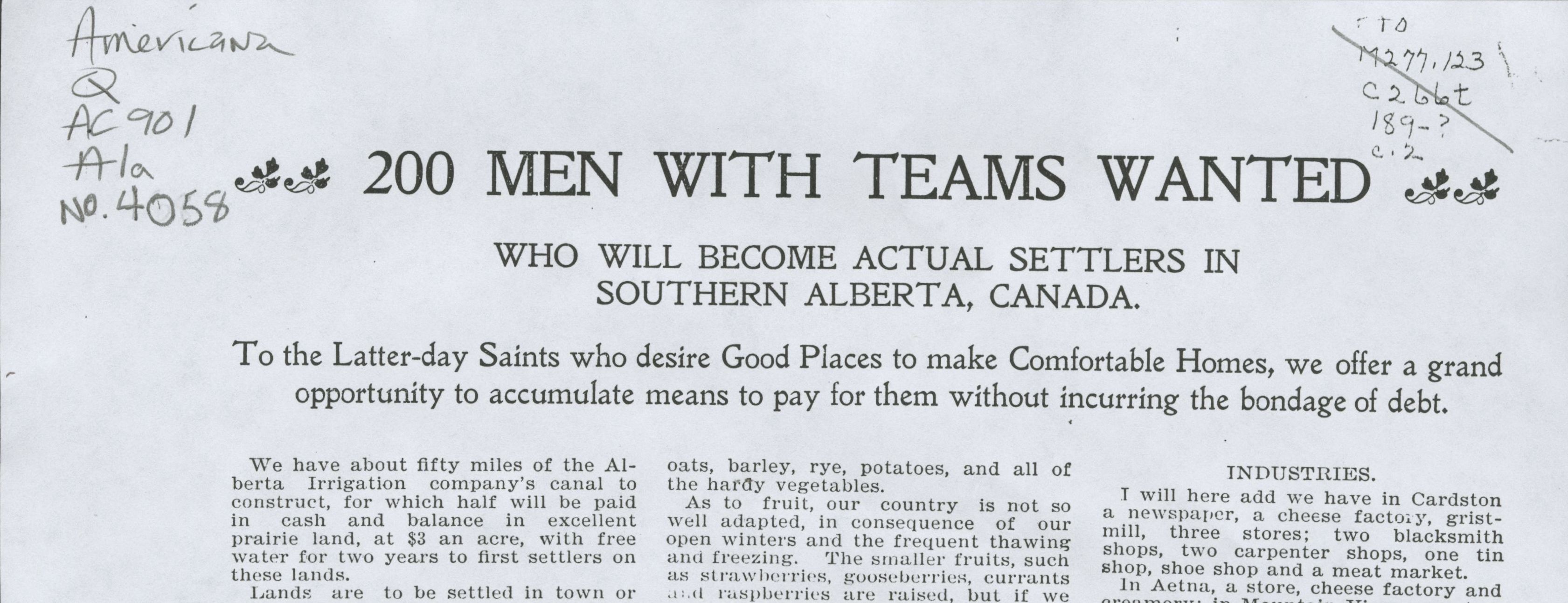

Charles Ora Card travelled all over Idaho and Utah in the winter of 1899 promoting the southern Alberta irrigation project. This article, which appeared in the Deseret News in January 1899 and was also printed as a circular, was part of his campaign. (Photo Archives, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University)

Charles Ora Card travelled all over Idaho and Utah in the winter of 1899 promoting the southern Alberta irrigation project. This article, which appeared in the Deseret News in January 1899 and was also printed as a circular, was part of his campaign. (Photo Archives, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University)

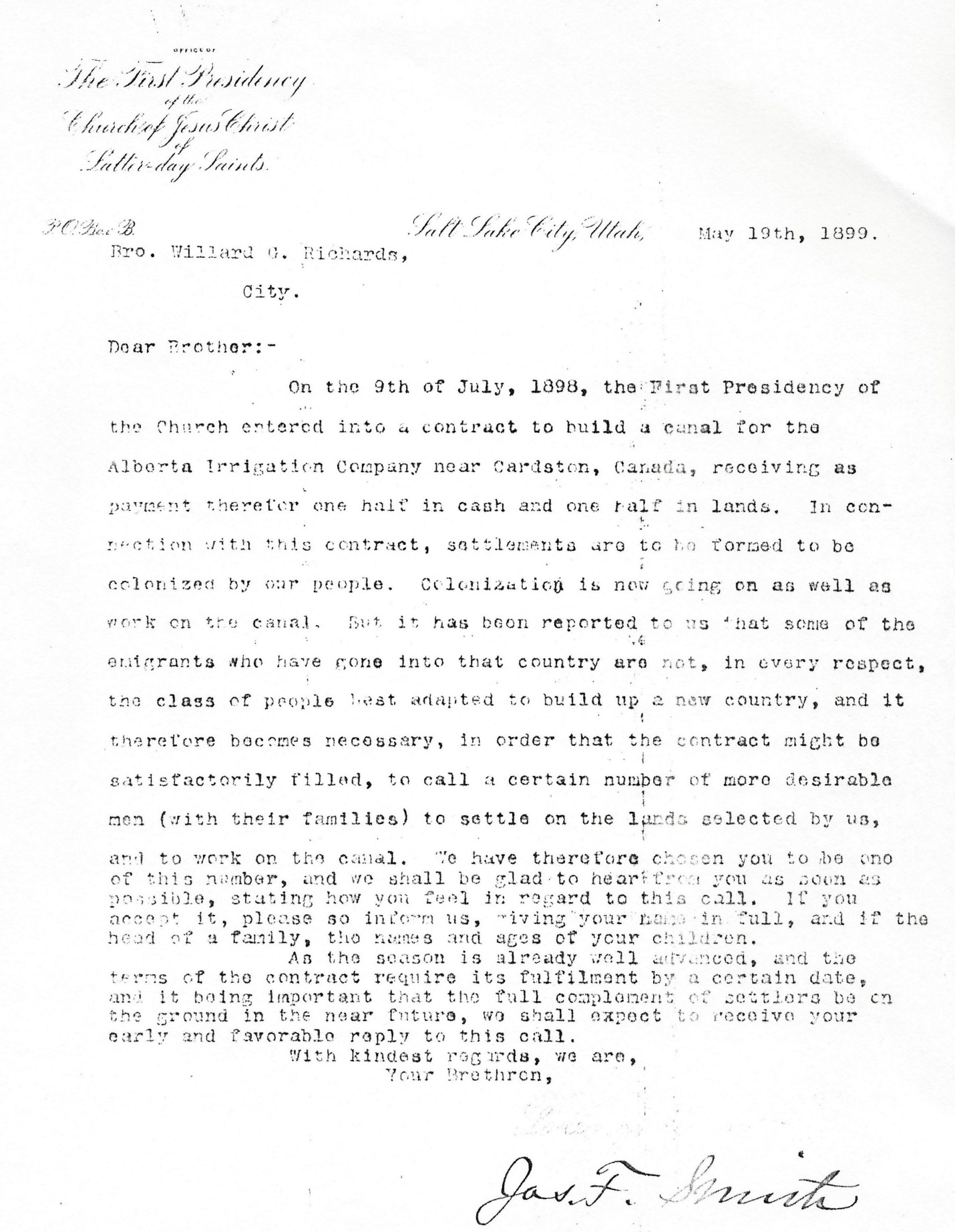

From December 1898 until April 1899, Card travelled all over Utah promoting the Canadian irrigation project. He kept an exhausting pace, speaking to congregations, publicizing through pamphlets as well as articles and advertisements in the Deseret News, and answering questions in person and by letter.[169] Despite the recruiting efforts of Card, John W. Taylor, and others, there were not enough people with the needed teams, equipment, leadership skills, and expertise volunteering to come to Canada. In early 1899, the Church began issuing mission calls, some for canal building and others for both canal building and settlement, in an effort to assure that they could meet their contract obligations and establish successful settlements.[170] Church members responded to the calls, and by the end of 1899, there were 424 settlers in Magrath and 349 in Stirling.[171] One of the first people called on a colonizing mission was Theodore Brandley. On 4 May 1899, he arrived by train at the Stirling junction with his family and company of 24 souls, the first settlers of Stirling. His call was to direct the settlement of Stirling.[172] As new families arrived, he met them at the train station, helped them choose a town lot for their future home and get started on canal building.[173]

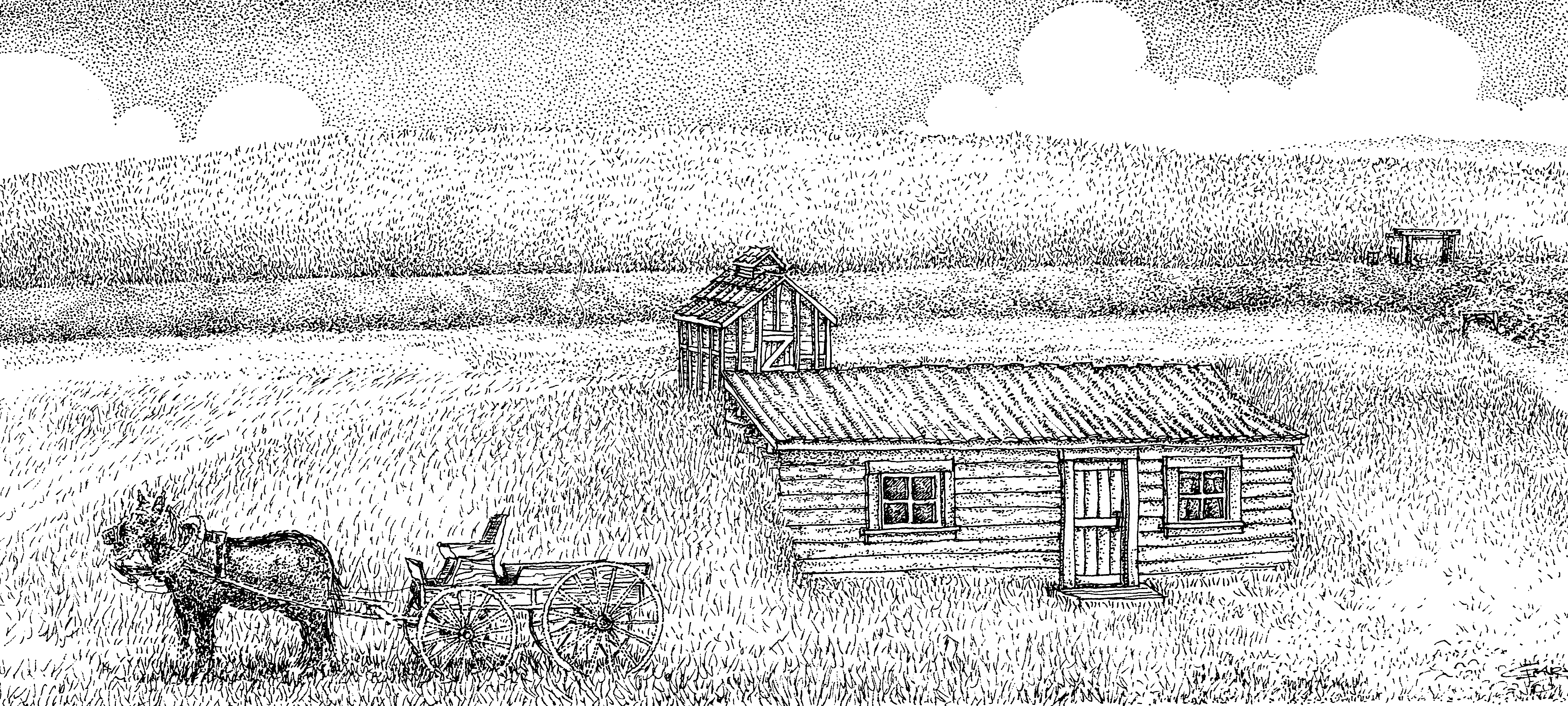

Charles Heber Dudley was the first settler in Magrath. He came alone and took a contract for a particularly challenging one-mile section of canal just east of today’s Highway 62, which came to be known as “Gumbo Point.” He returned to Utah for his family in the spring of 1900. This picture is a depiction of the twenty-four-by-eighteen-foot dugout home, excavated into the hillside, where his family lived for four years. (Alan Dudley)

Charles Heber Dudley was the first settler in Magrath. He came alone and took a contract for a particularly challenging one-mile section of canal just east of today’s Highway 62, which came to be known as “Gumbo Point.” He returned to Utah for his family in the spring of 1900. This picture is a depiction of the twenty-four-by-eighteen-foot dugout home, excavated into the hillside, where his family lived for four years. (Alan Dudley)

The first families began arriving in Magrath in April 1899. On 20 April 1899, C. H. Dudley was the first person to arrive in Pothole, which was renamed Magrath in May 1899. The Rasmussen family arrived shortly after and claimed the honour of being the first family to arrive. Some, like Theodore Brandley and his company, came to Canada by rail, while others came by wagon. Though rail service was available as far as Stirling, it was logistically difficult and expensive for those travelling with animals, equipment, and household belongings to travel by rail. Those who travelled by wagon faced a six-week-long journey on rutted trails over mountain passes, through frigid rivers and across barren plains in often cold, stormy weather.[174] Truly, this was a new generation of Mormon covered-wagon pioneers. Receiving a mission call to leave behind lands, businesses, friends, and relatives just to uproot family and tame a new northern wilderness was no small thing. Responding to the call required great faith, and the Mormon settlements in Magrath and Stirling were blessed to be populated by this calibre of faithful and faith-filled pioneers.

To encourage more Latter-day Saints to settle in Alberta and participate in the canal-building project, Church leaders issued mission calls to faithful and industrious men and their families to relocate in Canada. This mission call letter, dated 19 May 1899, was addressed to Willard G. Richards and signed by Joseph F. Smith of the First Presidency. It is an example of many similar letters that were sent. (Courtesy of Jack Stone)

To encourage more Latter-day Saints to settle in Alberta and participate in the canal-building project, Church leaders issued mission calls to faithful and industrious men and their families to relocate in Canada. This mission call letter, dated 19 May 1899, was addressed to Willard G. Richards and signed by Joseph F. Smith of the First Presidency. It is an example of many similar letters that were sent. (Courtesy of Jack Stone)

Canal building was done with teams of horses plowing the ground to loosen it and removing the dirt with a horse-pulled slip scraper, not aided by any machinery. It is estimated that by the time the Lethbridge branch line was completed in 1900, over 1,121,000 cubic yards of dirt had been moved, and over one million feet of freighted-in lumber had been used to build gates, sluiceways, and buildings.[176] Canal building was an arduous task under the best of conditions, but in the spring of 1899, canal workers faced anything but optimal conditions. According to the story told by Samuel Woolley Taylor, son of Apostle John W. Taylor, two weeks of heavy rain in June 1899 slowed progress on the canal to almost a standstill and severely discouraged workers, who wondered why irrigation was needed in a country with so much rain. The men were growing increasingly concerned that with work on the canal going so slowly, they would not have time to plant crops in time to reap a harvest before winter. Some were ready to give up on the canal. However, at this critical moment, John W. Taylor travelled around to the work camps, encouraging the workers. He reminded them of the Church’s contract and of their responsibility to uphold the integrity of the Church. He promised them that if they would fulfill their canal obligations, the Lord would temper the elements and they would obtain a harvest, though the season was late. He also encouraged them to hold dances and play music at their camps to lighten their spirits. Eventually, the weather improved and the canal work progressed. Apostle Taylor’s promises were fulfilled. Miraculously, the summer season was extended, and the Saints were able to harvest their crops.[177]

From 1898 to 1900, Mormon settlers built the irrigation canal from Kimball to Stirling with a branch line to Lethbridge. Teams plowed the ground to loosen the earth, then moved the soil one-tenth of a meter at a time with a horse-drawn slip scraper. (Sir Alexander Galt Museum and Archives)

From 1898 to 1900, Mormon settlers built the irrigation canal from Kimball to Stirling with a branch line to Lethbridge. Teams plowed the ground to loosen the earth, then moved the soil one-tenth of a meter at a time with a horse-drawn slip scraper. (Sir Alexander Galt Museum and Archives)

During the period of canal construction, new settlers received a visit from Joseph F. Smith of the First Presidency of the Church. In a meeting held 6 November 1899, President Smith spoke powerfully and prophetically of the importance of LDS settlement in Canada. He told the Saints that they were in the Lord’s vineyard where God wanted them and that they were “laying the foundation of a great work that [they could not] comprehend.” He told them that God would bless them there and not forget them.[178] Little could these weary pioneers imagine the strength their little communities would contribute to the Church in Canada.

The canal had an inestimable value in opening up the Canadian prairies for settlement and assuring Canadian sovereignty north of the 49th parallel. The canal itself brought in many settlers, but perhaps more importantly, its success proved that the Palliser Triangle could be settled with the help of irrigation. It was the first of many large-scale irrigation projects in this arid region. According to geographer Lynn Rosenvall, irrigation canals and water systems constitute “the most important Mormon contribution to agricultural development in Western Canada.”[179] These systems continue to contribute to the agricultural productivity of southern Alberta in the twenty-first century.

A cowboy watches his cattle beside a newly dug irrigation canal in Stirling, 1900. Irrigation soon transformed grasslands, which had previously served for the grazing of cattle, into farmlands. (Glenbow Archives NA-922-18)

A cowboy watches his cattle beside a newly dug irrigation canal in Stirling, 1900. Irrigation soon transformed grasslands, which had previously served for the grazing of cattle, into farmlands. (Glenbow Archives NA-922-18)

Community Building in Magrath and Stirling

Settlers in Magrath and Stirling had the advantage of Church organization in place early. The first Church services were held in Magrath on 28 May 1899. Two weeks later, Levi Harker, the sheep farmer who had been living in the Cardston area and who had the vision of the future of Magrath, was sustained the first bishop of the Magrath Ward. On the same day, Theodore Brandley was sustained as bishop of the new Stirling Ward.[180]

The Theodore Brandley General Store in Stirling. (Church History Library)

The Theodore Brandley General Store in Stirling. (Church History Library)

Nevertheless, conditions were especially difficult for the settlers the first year. Having been so occupied with canal building, some settlers did not have time to build homes. Some spent the winter in dugouts on a hillside, while others lived in tents. After a tough winter, they had to build houses for their families. They also had to break the virgin soil, raise crops and livestock, and help build community facilities. Some helped build the railway to Cardston and took contracts to build additional canals.[181] They were industrious in all these labours and soon had productive communities. In 1902, despite severe flooding which damaged the canal and many homes, Charles Ora Card reported to the First Presidency that the colonies were stable enough to stand alone without further assistance from Church headquarters in Salt Lake. By 1903, Stirling had telephone service, rail service to Cardston, two stores, a post office, a church, a school, two lumberyards, and irrigation to town lots.[182]

Magrath enjoyed similar progress. It was incorporated as a town in 1907.[183] Both communities had an active community life with sports, recreational activities, bands, dramatic productions, and so on.[184] The communities continued to grow as new waves of LDS settlers arrived from Utah.[185] By 1911, Magrath had 995 residents and Stirling had 514.[186] Farmers organized themselves into cooperatives known as irrigation districts to expand and manage the irrigation system. This was parallel to the pattern that was common in the American Mormon settlements.[187] Several large ranches were also established in the area, particularly on the Milk River Ridge.

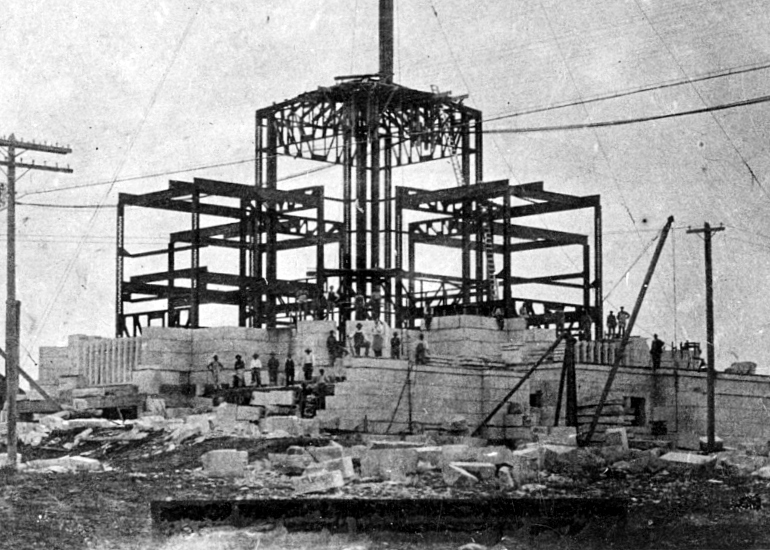

A picnic for members of the Magrath Ward during a workday at the missionary farm, 1903. Proceeds from the farm supported missionaries and missionary work. The first five missionaries from Magrath left that same year. Church farms in southern Alberta have been an important source of funds for Church building projects, ward budgets, and welfare needs. (Magrath Museum)