Maeser and Cluff: Competing Paradigms?

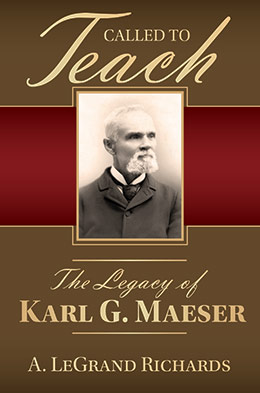

A. LeGrand Richards, Called to Teach: The Legacy of Karl G. Maeser (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2014), 541–564.

By keeping close to . . . the Spirit of the Gospel, upon which the Academy is founded, . . . there is no foretelling of all the grand results that will eventually grow out of the labors done in that institution.

—Karl G. Maeser to Benjamin Cluff[1]

During the last decade of his life, Maeser continued his remarkably challenging schedule of teaching Sunday School conferences, demonstrating religion classes, and visiting the Church schools. The rigors of his schedule would have been demanding with the most modern conveniences and modes of travel available today, but it is difficult to imagine how challenging it must have been in the 1890s, traveling by rail and buggy. Each year he would plan to visit all of the Church schools and as many of the wards and branches as possible on the way.

Consider, for example, some of the details of his first circuit tour in 1896. After conducting Sunday School conferences in Salt Lake City at the end of January, he traveled to Idaho (151 miles). On February 21 he observed the instruction at the Oneida Stake Academy in Preston, holding a public meeting that evening. On the twenty-second, he met with their academy board in the early afternoon, then traveled to Weston (12 miles) to deliver a lecture for the county district teachers on the teacher’s responsibilities to the family and public. The next day, he was back at Preston (12 miles) speaking at a public meeting. On the twenty-fourth, he traveled to Logan, Utah (27 miles), to meet with the faculty of the Brigham Young College. On the twenty-sixth, he was at Paris, Idaho (59 miles), presenting to the faculty of the Bear Lake Stake Academy. On the twenty-seventh, he spoke at St. Charles, Idaho (8 miles); on the twenty-eighth, he spoke at Liberty, Idaho (16 miles); on the twenty-ninth, at Ovid (4 miles). On March 1, he spoke at Paris (5 miles), in the afternoon and at Bloomington (3 miles) in the evening. On March 4, he was back at Rexburg (167 miles) visiting the academy; he met with the board on the sixth, then spoke at the Parker Ward (11 miles) at 10:00 a.m. and at the St. Anthony Ward (5 miles) at 2 p.m. On the eighth and ninth, Maeser conducted a Sunday School conference in Rexburg (11 miles) for the Bannock Stake. On the tenth he spoke again at a public meeting in Rexburg, then traveled to Lewisville (13 miles) to speak at 8:30 p.m. On the eleventh, he spoke in Pocatello (70 miles). Then he returned to Salt Lake and Provo (206 miles). In approximately three weeks, he traveled over 800 miles, mostly by buggy, and delivered more than twenty public discourses.[2] It might be noted that even though Maeser was “bundled up like a chrysalis” in blankets,[3] February and March were not the most pleasant months of the year for extended buggy rides through Idaho. The dizziness of this particular circuit tour was repeated in almost all of his tours.

Maeser wrote a report to the Church school officers and teachers in the Juvenile Instructor nearly every other month. He also maintained his enormous correspondence load by, encouraging teachers and principals and clarifying board policies and counseling on particular challenges as they arose. He continued to believe and defend the idea that Brigham Young Academy was to be the model school for all the Church academies. His expectations for Benjamin Cluff were particularly high. During this period, however, he was constantly attempting to temper Cluff’s tendency to overreact to some policies and underreact to others.

The Tensions Inherent in a Religious University

Maeser and Cluff had great respect and affection for one another, but they were of very different dispositions. The tensions between them were not merely the tensions between two very different personalities whose lives intersected at two very different points in their mortal experiences. The tensions they lived were the tensions that challenged Brigham Young Academy then and those that have challenged Brigham Young University ever since. These were the challenges that a “church-sponsored university” must face: challenges of allegiance, authority, governance, faith, accreditation, and public reputation.

Some have argued that the differences between Maeser and Cluff were a conflict between Maeser’s established conventional methods of European authority and Cluff’s progressive new educational techniques. This is an oversimplification. In fact, the methods of progressive education that Cluff supposedly learned at Michigan were mostly developed in Germany and Switzerland by Pestalozzi, Diesterweg, and the Reformpädagogik movement and were borrowed by the American progressives.[4] Cluff even confirmed this in a letter to Maeser in 1890.[5] Maeser was teaching progressive education twenty years before it was called such in America.

Bergera and Priddis went so far as to claim that “Cluff’s progressive approach to education represented the antithesis of what had been practiced at the academy under his predecessor.”[6] This is a massive overstatement. The actual innovations Cluff introduced were relatively minor, and the formal philosophies of the two men were virtually indistinguishable.[7] They often shared the same pulpit and almost always in those settings affirmed each other’s ideas. Their respect and fondness for one another was constant.

Ernest Wilkinson’s description of the contrast between Maeser and Cluff was technically more accurate, but it has helped to reinforce the stereotype of Maeser’s supposed traditional authoritarian methods by describing Maeser as “staid in appearance, an adherent of Prussian methodology of education, conservative, and sober in his demeanor.”[8] However, Wilkinson made no mention of the fact that the prerevolutionary “Prussian methodology” Maeser learned and used was antithetically different from the reactionary Prussian methodology that followed the failed revolution that is conjured up in the contemporary mind.[9] In contrast, Wilkinson described Cluff as “vibrant, impetuous, and imbued with new educational ideas he had brought from Ann Arbor.”[10]

It is true that Maeser was more formal, much older, more experienced, more cautious, and suspicious of the ways of the world. Cluff was young, exuberant, perhaps a little impatient, and hungry to participate in every opportunity of life.[11] Both men had a love of truth, and both wanted to foster the growth of young people within the context of their eternal missions. Both men had gratefully received the finest academic education the world had available at the time, one in Germany and the other in the United States. Interestingly enough, both educations, at the time, were deeply influenced by the same progressive principles and Pestalozzian philosophy. But Maeser had received his education before he was introduced to the principles of the restored gospel, and Cluff received it after.

Both men were dedicated missionaries who found great joy in bringing the message of their faith to those who did not yet see its power or persuasive evidence. Both knew the importance of constant learning and demonstrated passionate dedication to continuous study and growth. Both men felt a deep loyalty to Brigham Young Academy and recognized its central role in providing a model to the other Church institutions.

Maeser’s suspicions regarding the world’s secular training was built on his own personal experience. He knew, from his own life, how intellectual development without a balancing spiritual component could persuade a young student toward agnosticism. [12] He also knew what it was like to feel the ridicule of prominent thinkers who exerted discriminating prejudice toward immigrants and Mormons.[13] He had witnessed very bright Latter-day Saint intellectuals who had begun by disagreeing with priesthood authority and eventually grew into bitter enemies of the Church, using their intellects to fan the flames of dissidence.[14] Cluff grew up in very different times. The academic circles in which he moved were far more tolerant and accepting of Mormons. Prejudice toward the Church was far more subtle, and the dangers of secularization were not as vivid to him. Through most of Maeser’s career, the relationship of the Church and the United States was one of independent hostility; Cluff’s generation found a much more tolerant and financially interdependent relationship.

Cluff reveled in his experience at the University of Michigan, celebrated his friendships with some of the most prominent educational leaders in the country (including Francis Parker, John Dewey, George Herbert Mead, William James, G. Stanley Hall, Charles Eliot, and James Angell) and wanted as many BYA teachers as possible to go back and receive such an experience.[15] He believed that strengthening friendships with prominent educational leaders in the country would strengthen the reputation not only of BYA but also of the Church in general. Cluff did not share Maeser’s concerns that too many young minds went east and lost their testimonies of the Church. When he was in Michigan, Cluff even visited the Sunday schools of other denominations “with the view of getting suggestions for our own.”[16]

Maeser was constantly reading and studying the ideas of others.[17] He taught that “a teacher’s profession is a progressive one, and a teacher that ceases to learn, ceases to be fit for teaching. A fossilized, run-into-a-groove teacher, in short, a pedant, is an incubus upon the profession. . . . None of us have a monopoly on the truth.”[18] He encouraged the teachers of the Church schools to participate in the county teachers associations and even more so to invite the district school teachers to join them in their ongoing Church school training.[19]

At the same time, however, Maeser looked primarily to the prophets and modern revelation, to a religious purpose and mission and personal revelation. Cluff believed more strongly in bringing in all the good that could be found from the latest developments across the world. Neither was so rigid as to dismiss the other, but both experienced the tension inherent in an experiment to establish a Church-sponsored institution of higher education, and both saw the heart of their allegiance a little differently. Maeser might have asked, “If revelation comes from God, why rely very heavily on lesser sources?” Cluff might have asked, “If the gospel is the heir to all truth, why not embrace all sources that contribute to it?” Neither would have dismissed the importance of asking the other’s question, but the priority of these questions was a part of their differences.

A contrast between the teaching values of Maeser and Cluff at the Summer Teachers’ Institute illustrates this point. With Maeser, Utah teachers were invited to participate under the tutelage of Maeser and other teachers experienced in the Latter-day Saint approach to teaching (for example, Talmage, Cluff, Tanner, Nelson, and others). Under Cluff, the institute invited prestigious national figures who taught sessions alongside established Latter-day Saint educators. Maeser was always invited to be a participant, even though he was not always able to attend, and he enjoyed participating. Francis Parker’s visit in 1892 was a great experience for Maeser; he also attended and enjoyed Charles Eliot’s visit. In 1895, Cluff did not invite a national figure to the Summer Teacher’s Institute; he relied on the faculty of the BYA but advertised the instructors based upon the schools they graduated from in the East—for example, Joseph Jensen of MIT, W. M. McKendrick of Harvard, and Alice Reynolds of Michigan.[20] In 1896, Edward Howard Griggs of Stanford University gave a couple of lectures at the Summer Teacher’s Institute.

Evolution Controversy at BYA

For the Summer Teacher’s Institute at BYA, 1897, Cluff arranged to bring in the famous G. Stanley Hall, president of Clark University and founder of the American Psychological Association. Because he was engaged in his circuit tour of Arizona and Mexico, Maeser was not able to attend, but he followed the newspaper reports by Nels L. Nelson very carefully. It sounded to him that “the professor’s philosophy is evolution pure and simple, embellished and coached up, however, by splendid eloquence and dialectic.”[21] Cluff wrote back to Maeser, “Dr. Hall is no doubt an evolutionist, as are all scientific men, but he is what you would call a modified evolutionist.” He claimed that Dr. Hall did “not believe in the Darwinian theory of the origin of man.” He also added, “I regret very much that you were not able to be here, as I am certain you would have taken great pleasure in meeting the able professor.”[22]

In fact, Maeser would have agreed with much that Hall presented. In his first lecture, for example, Hall encouraged “nature-teaching.” He declared that “it is a narrow theology which interprets love of nature as opposed to love of God. Much holier is that conception which regards the love of created things as part of the worship of the Creator.” Hall knew that some neglected science teaching for fear of encouraging infidelity, but such fears, according to him, were “groundless.” He believed that the atheistic days of Huxley and Spencer had passed and that “today a band of investigators stand at the head of science who so far from scoffing at the reality of religion are earnest students alike of physical and spiritual phenomena.”[23]

Hall argued in further lectures, “Religion is the central fact in childlife, and no educational system is complete that neglects the cultivation of it.” He criticized American schools for neglecting it “because of the much-vaunted separation of church and state.”[24] He also argued that the Bible was “foremost among best books” and should therefore be central to a child’s reading.[25]

Cluff also reported to Maeser that “the Doctor was especially interested in the principles of the Gospel and before he left made purchase of all of the Church works” and visited with the First Presidency.[26] Maeser thanked Cluff for the clarification of Hall’s position,[27] but two anonymous authors began a series of letters to the editor of the Enquirer critical of inviting an evolutionist to speak at a Church school.[28] Nelson, who had edited Hall’s lectures for the Deseret News, responded quite sharply to these letters. This series of responses continued for over a month. So Maeser wrote to Cluff, “The discussion in the Enquirer about Bro. Nelson’s articles on Dr. Hall’s lectures is very unfortunate and is injurious to the influence of the institution. It must be stopped at once.”[29] He believed that the attention the argument was bringing BYA was not helpful. There were already enough “university people” trying “to counteract the influence and reputation of the BYA.” The “invisible rock” upon which the academy was founded was its “religious soundness,” and it would be a serious problem if people lost their confidence in that rock. Cluff tried to reassure Maeser that “the little controversy here in the paper” would not do any harm, but rather good. Regarding “the eminent men of science and letters,” Cluff insisted, “the school is not responsible for all of their utterances.”[30] Maeser was concerned that BYA protect its religious reputation and not raise unnecessary controversy; Cluff was convinced that the best way to strengthen the reputation was by strengthening its academic standing in the world.

Bergera, Priddis, and others have argued that Maeser considered evolution “taboo,” [31] while Cluff, “the school’s progressive principal,” openly defended “many of the premises of evolutionary theory,” in his theology class.[32] In reality, Cluff and Maeser agreed more with one another on this topic than they disagreed. Maeser was troubled far more by the argument and arrogance suggested in Nelson’s defense of Hall than by the arguments for evolution. For Maeser, to openly wrangle with another debate was unbecoming of a school’s representative, and he wanted it to stop. Cluff, on the other hand, believed that the controversy was simply a demonstration of the marketplace of ideas.

In fact, Maeser did not oppose evolution as a theory unless it was claimed to be a “final cause,” replacing the Creator. He made his position regarding evolution quite clear in 1895 and 1898: “Evolution is one of those agencies by which an all-wise Creator controls the development of His creations toward their ultimate destinies, but it is by no means either the only one or the Great First cause.”[33] Cluff would not have disagreed.

Maeser was not accusing Cluff of leading the school in an inappropriate direction. In fact, in the same letter asking Cluff to stop the debate in the Enquirer, Maeser congratulated Cluff for “the conscientiousness with which you observe our theological, domestic and monitorial principles which constitute the chief characteristics and distinguishing features of our educational system.”[34] He endorsed the prominence of BYA. “You are far ahead of the next of our church schools, taking the lead as the BYA always should do.”[35] Maeser was also pleased in 1898 when the General Board of Education unanimously awarded Cluff the title of doctor of didactics. He wrote that it was a “well- and long deserved recognition of your faithful and efficient services in the educational field.”[36] The differences between Cluff and Maeser, then, were far more subtle than often portrayed.

Religious Governance

The most serious difference between Cluff and Maeser was demonstrated in their attitude regarding the role of spiritual guidance and priesthood authority in academic matters. Maeser would hardly make a move or set a policy until he felt through prayer that the Lord would confirm the idea and that it was in harmony with the leading priesthood authorities in the Church. Nelson wrote that when Maeser was “perplexed even by small problems of school discipline” as a principal, he “would retire to his little office and lay the matter before the Lord, just as a child might approach his father with some unforeseen difficulty.”[37] Regarding the decision to send a teacher to help organize a stake academy, he wrote:

I have often stepped into the Normal room, but have seen no one whom I thought I could send. I remember one particular instance. I went home and asked the Lord whom I should send. That night I dreamed that I was in the Normal department, and a young man was with me. When I mentioned it to this student on the following day he said he could not think of accepting such a situation. I took him in the office, and together we asked God for guidance. The young man was sent, and he has been called a benefactor to that community. We may and must have brighter men intellectually than some who have been called to such positions in the past, but I hope and pray that we may have none without that great gratification, the Spirit of the Living God.[38]

As superintendent of Church schools, Maeser often asked President Woodruff for his counsel and advice on issues that many would suppose to be perfectly within his own purview to decide. He wanted confirmation on his travel schedule, school circulars, and hiring policies. When the general board set a policy, Maeser saw it as law.

Cluff did not operate under the same set of assumptions. He was much like an unbroken colt: ambitious, energetic, and not very patient with Church procedure. If he wanted to do something, he expected support for it, and he tended to react very quickly to things he disliked. When the Church Board of Education wanted to influence Cluff’s hiring decisions, he protested. When they prohibited the Church schools from handing out diplomas at graduation without their approval, he ignored the policy. When they decided that intercollegiate debating, college yells, and football contests should be prohibited, Cluff appealed the decision and allowed them to be conducted secretly until the policy was changed. He was notoriously late in submitting his records to the Church general board and reacted, sometimes in great haste, when he felt criticized.

This difference in attitude began to show itself in fairly small things. In May 1893, for example, Maeser wrote Cluff expressing his surprise that some BYA publications were using the term “professor” for teachers who had not been given the proper credentials according to the policy of the general board.[39] Cluff replied with an argument that Maeser believed held no relevance but showed a disturbingly noncompliant attitude.[40]

On another occasion, Cluff reacted quite dramatically in 1894, when Apostle Heber J. Grant spoke at a conference for the youth of the Utah Stake about the need to live closer to the Spirit of God. Elder Grant’s address focused on the need to live one’s religion, obey the Word of Wisdom, and avoid debt. The Deseret News reported that he proposed “something more than the cultivation of the mind was necessary to the perfect development of our young people. . . . The spirit of the Gospel should have a prominent place in all our educational institutions.”[41] The Enquirer, however, quoted him as suggesting “that the same spirit is not exhibited by the young graduates now as when Bro. Maeser was at the head of the school. Something more is needed than mind culture; the spirit of God is also needed.”[42] It also reported, however, that in the afternoon session Elder Grant apologized if his remarks were misunderstood. “I know of no other place that is doing as much for education as the Brigham Young Academy. I did not intend to . . . run down the leading school of the Territory.”

Cluff, who was not in attendance, immediately fired off an indignant letter to President Woodruff. President Woodruff and Joseph F. Smith wrote Cluff back: “We regret that any circumstances have arisen to cause you to so write. We believe we appreciate the good that the B.Y. Academy is doing and would not do nor say anything, nor have others do or say anything, that would lessen its influence for good.” They suggested that he may have overreacted to “an exaggerated account” and that President Smith, who was in attendance, “did not recognize in the remarks made those difficulties that present themselves to your mind.” They concluded with the hope that Cluff would “act wisely in letting the matter drop, as we do not think the incident was of sufficient importance for you to entertain the indignant feelings that your letter suggests.”[43] Cluff did not pursue this further, but it demonstrated his tendency to overreact.

In October 1896, Brigham Young Jr., Smoot’s replacement as the president of the BYA board and a member of the Church’s Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, disagreed with some of Cluff’s policies. Maeser wrote both parties to encourage reconciliation. To Cluff, Maeser wrote, “I wrote a letter to Bro. Brigham Young exonerating you from the charge according to Bro. Keeler’s report.” He made it clear that Brother Young “declared he would resign” from the board if Cluff did not comply and that Cluff would be asked to resign if he did not find a way to resolve the concerns. Maeser concluded, “I am a truer friend to you than it would be my place to state here.”[44] Cluff tended to take board policy as he wanted. His position was, “If we should endeavor to run the school according to the hints we receive, even from good men, we would be like the man and his boy and the donkey.”[45]

Regardless of their differing points of view, however, both Cluff and Maeser agreed that the value of Church schools transcended a secular experience supplemented by religious training. They may have disagreed on some of the details of how it should be implemented and how open it should remain to input from people of other faiths, but neither thought secular learning was sufficient for Latter-day Saints. Trying to demonstrate this position became a dominating theme of Maeser’s last few years.

Cluff’s Expedition to South America

It was in 1900 that the most serious difference between Maeser and Cluff was demonstrated. Cluff had proposed an expedition to South America, believing it would bless the Church, the academy, and the students by searching for the ancient Book of Mormon city of Zarahemla—hardly a secular venture. Initially he received the support of the Brethren for the expedition and called it a mission, but between the tense political conditions in Central America, delays at the border, and accusations of misconduct by the members of the team, serious questions were raised regarding the reasonableness of the excursion. Elder Grant, then a member of the Quorum of the Twelve, met the group in Arizona and returned to Salt Lake to express his belief that the expedition should be disbanded.[46]

Maeser had returned from a circuit tour to Arizona and Mexico before the expedition left in April. He had an assignment to conduct a Sunday School conference in Ogden, so he was not available to wish farewell to Cluff and the expedition. He sent his regards through George H. Brimhall and then proceeded to another circuit tour in southern Utah and other administrative duties, so it is not clear how informed Maeser was regarding the feelings of the Brethren toward the expedition. Eva reported that her father had been quite concerned that Cluff had not received sufficient approval from Church leaders before leaving and that when Maeser confronted him, Cluff stated that it was sufficient that he had made up his own mind.[47]

While Maeser was away from Salt Lake, the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve met and decided to contact President Joseph F. Smith, who was traveling to Mexico to meet with Cluff and tell him that the expedition should be terminated. Cluff adamantly maintained that the honor of the school required it to continue, saying that “his reputation was worth more to him than his life.”[48] On hearing Cluff’s response, the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve met again on August 9 to discuss the matter. Elder Grant expressed concern, writing, “Brother Cluff should have respected the mind of the man sent specifically to reflect the mind of the Presidency to him, but instead of doing that he persists in carrying out his own wishes.”[49] To make matters worse, it was disclosed that Cluff had sought post-Manifesto permission from President Snow to marry another plural wife, Florence Reynolds, a former student and teacher at the Church academy at Colonia Juárez.[50] Permission was denied, but Cluff found a way for it to happen anyway while he was in Mexico. President Cannon stated that had he known of this, he would have opposed the expedition in the first place. It was decided that a telegram would be sent to President Smith informing him “that it was the mind of this council that Brother Cluff and his party disband and return.”[51]

Without mentioning his secret marriage to Florence Reynolds, once again Cluff insisted that the reports of misconduct were “gross exaggerations” and that the expedition must continue with or without the Church’s endorsement. All but seven of the students were released to return home, but the expedition continued. Cluff wrote, “I do not feel discouraged though I am humiliated. I feel that a great injustice has been done me, and through me the Academy, but I thank God that I am permitted to go on.”[52]

The expedition was anything but a success; the party suffered sickness, Cluff spent time in a Mexican prison, and when they returned in the spring of 1902, a formal complaint was filed against Cluff. A trial was held by the board of directors to investigate twenty-four charges brought against Cluff by Walter Wolfe and others of the expedition. They charged him with immoral conduct and abuse of his authority. After thirteen hours of deliberation, Cluff was vindicated of almost all the charges,[53] and though he was retained another year as president of BYA, his reputation never completely recovered.

For Maeser, it was imperative to remain in harmony with the Brethren and to abide by the counsel of priesthood leaders. He taught his students, “If we understood the nature of the priesthood to the fullest extent we would rather lay our hands on hot coals, and burn it to cinders than to raise our hand against one holding the priesthood. You have made sacred covenants.”[54] While Cluff persisted in his expedition in opposition to priesthood counsel, Maeser continued his whirlwind pace as superintendent of Church schools and counselor in the general Sunday School presidency. On September 2, 1900, Maeser was thrilled and humbled to be called as patriarch in the Salt Lake Stake.[55] He had taught that patriarchal blessings were paragraphs “from the book of our possibilities,”[56] so he saw this responsibility as a great honor.

In October, Maeser was asked to participate once again in the Founders’ Day celebration at BYA. The program deeply moved him, and when he was asked to speak, he arose and said:

While on my seat a panorama of academy pictures passed before my mind. At the commencement of this great outgrowth it had been my policy to teach correct principles, and the students had governed themselves. Line upon line, precept upon precept, was given me by my heavenly Father in the directing of the school. Many bitter lessons were received when I did not solicit the aid of the Spirit of God, while everything had been plain to me when I went to my heavenly Father.[57]

The students were then urged to learn this valuable lesson early in life, and thus escape the sad mistakes that would happen otherwise. The students, he said, should study the language of God as is found in the dew-drop and the spear of grass, as well as in all the direct revelations of God.

The Need for Church Schools

One of the last projects Maeser undertook was once again to address the need for Church schools. Apparently, there had been a renewed attempt by the University of Utah to undercut the educational efforts of the Church. In December 1900, George H. Brimhall (acting president of BYA in Cluff’s absence) wrote to Cluff in Mexico, expressing his concern that the University of Utah was trying to force “the Church to discontinue collegiate work and make the Church schools nothing more than High schools and feeders to the University.” Brimhall believed that the need was greater than ever to support a “Latter-day Saint College.” In the “educational institutions of the world,” a young man could expect “that everything [would] be done to tear down his faith.” Brimhall felt that “having Mormon professors in the University with a view of guarding against infidelity” would fortify students much better and make the “loss of faith in the Gospel less possible.”[58] He explained that he had expressed his opinion on these matters to a few General Authorities and was planning to express it to President Lorenzo Snow. He knew that financial matters in Salt Lake were very delicate topics at the time, but he felt that with the academy’s growth, the means would come.

Again, the response to this matter differed greatly between Cluff and Maeser. Cluff immediately wrote back to Brimhall from Mexico in fairly aggressive terms:

Let me urge you not to give up your intention for the retention of the Collegiate Dept., until it is the expressed will of Pres. Cannon that you should yield. . . . It has always been a battle with us for our rights. If we had sat idly down, if we had not urged right at head quarters, the Academy would have been a little one horse stake institution today, and the other Church schools would have been but little better, while the University would have had all the pupils, and our elders would have deplored the great apostasy that had come among our young people. No, let us not give up nor get discouraged, nor frightened.[59]

Maeser probably shared many of the same concerns with Brimhall and Cluff. He had openly published that Church schools “are an essential part in the great program of the latter-day work,”[60] but he would never advocate fighting for “rights” from the Brethren. Rather, he was confident that with the proper information, they would make the best decision. He knew that stake presidents held the priesthood keys in their assigned areas; therefore, on the first of February, Maeser sent out a survey to the stake presidents who oversaw academies, asking them to reflect on the impact of Church schools on their stakes. The intent was not to present a general public referendum in favor of Church schools in order to put pressure on the General Authorities, but to gain feedback from the specific priesthood leaders who had stewardship over the young people in their stakes.

Maeser did not live long enough to follow up with all the stake presidents, to tabulate the results, and to submit a final report to the First Presidency, but he did raise the question of how and why the Church should sustain its own school system. Both Maeser and Cluff believed that such a system was necessary, but they disagreed on the Church’s role in its governance. This tension has continued. How much should a Church school conform to the academic standards of the larger society? What is the proper balance between resisting the influences of the world and seeking to impress it? What is the proper relationship between academic expertise and priesthood authority? If Church leaders are seen as spiritual stewards over the school, what does it mean to speak of academic freedom? How should disagreements in policies or academic theories be resolved at a Church school? How can a compartmentalized position that divides the secular and religious be reconciled with an integrationist position that recognizes no such division? How should integrationist educators be properly prepared to serve in a secular educational system? On the other hand, how can integrationist educators be properly prepared by compartmentalist academic programs outside of the Church educational system? How can an education built on the belief in continuous revelation avoid the temptation to reduce its teachings to rigid dogmas? What is the proper course of action when a faculty member loses faith in the sponsoring Church? What place is there at a Church school for faculty members who are academically competent but not members of the sponsoring Church? These and many more such questions flow from a careful examination of the tensions between Cluff and Maeser.

Notes

[1] Karl G. Maeser to Benjamin Cluff, May 2, 1894, UA 1093, box 1, folder 2, no. 38, LTPSC.

[2] See, for example, Juvenile Instructor, April 1, 1896, 197, or January 1, 1896, 28–30.

[3] Mabel Maeser Tanner, “My Grandfather,” MSS SC 2905, 32, LTPSC.

[4] See, for example, Winfried Böhm, Die Reformpädagogik, Montessori,

Waldorf und andere Lehren (München: C. H. Beck), 2012.

[5] “My studies in this University have only tended to increase my confidence in your methods of discipline and instruction.” Cluff to Maeser, April 21, 1890, UA 1094, box 1, folder 6, no. 7.

[6] Gary James Bergera and Ronald Priddis, Brigham Young University: A House of Faith (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1985), 8–9.

[7] Compare with Brian Q. Cannon’s summary of Cluff’s teaching approach in “Shaping BYU: The Presidential Administration and Legacy of Benjamin Cluff Jr.,” BYU Studies 48, no. 4 (2009): 5–40. chapter 13 of this volume.

[8] Ernest L. Wilkinson, ed., Brigham Young University: The First One Hundred Years (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1976), 1:218.

[9] I described the shift in Prussian education in “The Enemies of Democracy: Lessons from a Failed German Revolution,” Rassegna di pedigogia 69, nos. 3–4 (2011): 291–304.

[10] Wilkinson, Brigham Young University, 1:218.

[11] For one of the most positive descriptions of Benjamin Cluff, see Cannon, “Shaping BYU,” BYU Studies 48, no. 4 (2009): 2.

[12] See chapter 2.

[13] See chapter 6.

[14] See chapter 10.

[15] See Cluff’s letters to George H. Brimhall and J. B. Keeler, November 5, 1893, and November 12, 1893, UA 1093 box 1, folder 1, nos. 30, 31, LTPSC.

[16] See Cluff to Brimhall and Keeler, November 19, 1893, no. 32.

[17] Bergera and Priddis claimed the opposite, but offered no evidence for it (see Wilkinson, Brigham Young University, 5).

[18] “The Church School Convention,” Juvenile Instructor, September 1893, 553.

[19] See for example Karl G. Maeser, “Church School Papers, No. 26,” Juvenile Instructor, December 15, 1893, 764.

[20] “Summer Normal School: Fifth Annual Session, May 27–June 28, 1895” (Provo, UT: Brigham Young Academy, 1895).

[21] Maeser to Cluff, September 1, 1897, Cluff Papers, UA 1093, box 4, folder 3, no. 67.

[22] Cluff to Maeser, September 10, 1897, box 3, folder 7, no. 11.

[23] G. Stanley Hall, “Love of Nature,” Deseret Weekly News, October 2, 1897, 27.

[24] G. Stanley Hall in N. L. Nelson, “From Childhood to Adolescence,” Deseret Weekly News, October 23, 1897, 601–2.

[25] G. Stanley Hall in N. L. Nelson, “Reading and Cognate Art,” Deseret Weekly News, October 30, 1897, 610.

[26] Cluff to Maeser, September 10, 1897.

[27] Maeser to Cluff, September 24, 1897, no. 69.

[28] One of the authors used the name “Query” and the other “Observer.” Nelson responded to their first letters to the editor in fairly critical terms and they continued to respond as if to bait him into stronger responses. The attacks became more personal than substantive. Almost nothing was debated about evolution directly, but personal insults flew from both sides. More than nine articles appeared in the exchange, each side accusing the other of abuse, egotism, and bigotry.

[29] Maeser to Cluff, October 9, 1897, no. 70.

[30] Cluff to Maeser, October 12, 1897, box 3, folder 7, no. 39.

[31] Bergera and Priddis, A House of Faith, 131.

[32] Bergera and Priddis, A House of Faith, 132.

[33] Karl G. Maeser, School and Fireside, (Provo, UT: Skelton, 1898), October 16, 1984, 340.

[34] Maeser to Cluff, October 9, 1897, box 4, folder 3, no. 70.

[35] Maeser to Cluff, October 9, 1897.

[36] Maeser to Cluff, November 21, 1898, box 5, folder 3, no. 11.

[37] N. L. Nelson, “Dr. Maeser’s Legacy to the Church Schools,” Brigham Young University Quarterly, February 1, 1906, 4.

[38] “Maeser Reception,” Deseret Weekly News, March 12, 1892, 376.

[39] Maeser to Cluff, May 31, 1893, UA 1094, box 2, folder 2.

[40] Cluff argued that it was a common practice in the East to call teachers “professor.” He also argued that Maeser had referred to Dr. Moench of Ogden as “Professor.” Maeser simply responded that the Church General Board had set a policy, which they had the right to do and that Church schools should conform to it or help change it. See Karl G. Maeser to George Reynolds, June 7, 1893, UA 1094, box 2, folder 2, no. 49, LTPSC.

[41] “MIA Conference,” Deseret Weekly News, December 8, 1894, 782.

[42] “Word of Wisdom: The Theme at the MI Conference,” Daily Enquirer, December 3, 1894, 1.

[43] Wilford Woodruff to Benjamin Cluff, December 12, 1894, UA 1093, box 1, folder 4, no. 97, LTPSC.

[44] Maeser to Cluff, October 22, 1896, box 3, folder 2, no. 132.

[45] Cluff to Maeser, October 12, 1897, folder 7, no. 39. Cluff was referring to one of Aesop’s fables, showing that to try to please everyone is to please no one.

[46] Wilkinson, Brigham Young University, 1:308.

[47] “Interview with Eva Maeser Crandall by Hollis Scott,” June 26, 1964, LTPSC, 70.

[48] “Interview with Eva Maeser Crandall,” 70.

[49] Journal History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, August 9, 1900, 1, CHL.

[50] Florence was the daughter of George Reynolds, secretary to the First Presidency, who had been the test case for the constitutionality of anti polygamy legislation. Eva Maeser Crandall reported that Florence’s clandestine, post-Manifesto marriage to Cluff nearly killed her father. “Interview with Eva Maeser Crandall,” 73.

[51] “Interview with Eva Maeser Crandall,” 2–3.

[52] Benjamin Cluff to George H. Brimhall, August 13, 1900, UA 1093, box 6, folder 3, no. 71, LTPSC.

[53] See David John, journal, May 15–16, 1902, LTPSC.

[54] Priesthood Meetings of the BYA minutes, UA 228 September 11, 1883, LTPSC.

[55] Journal History of the Church, September 2, 1900, 2, CHL.

[56] Alma P. Burton, Karl G. Maeser: Mormon Educator (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1953), 73.

[57] “Twenty Fifth Anniversary,” Deseret News, October 17, 1900, 2.

[58] Brimhall to Cluff, December 24, 1900, no. 80.

[59] Cluff to Brimhall, January 15, 1901, folder 6, no. 83.

[60] “Church School Papers,” Juvenile Instructor, June 1, 1894, 351–52.