The Interstake Center

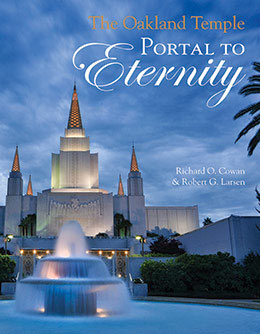

Richard O. Cowan and Robert G. Larson, The Oakland Temple: Portal to Eternity (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2014), 41–65.

1937 Property purchased on Lake Merritt for possible future tabernacle

1949 Plans announced for Los Angeles Temple (January 17)

1955 Architect Harold W. Burton presents plans for Interstake Center (January 14)

1956 Third stake organized in East Bay Area (August 19)

1957 Ground broken for Interstake Center by Stephen L. Richards (July 20)

1960 Interstake Center dedicated by President David O. McKay (September 25)

Even though the site for a temple had been acquired, no one expected that it would be built immediately. However, few realized how long it would actually take. Still, there was great interest in the site that became known as Temple Hill. Members and their families climbed slopes and crossed fences to reach the site where they could take pictures and enjoy the view. There were even events such as an Easter sunrise service held on the hill.

Postwar Growth in the Bay Area

During World War II, a large number of young Latter-day Saint men and women from all over the country joined the armed services. For example, in 1944, some 615 persons were included in the “roll of honor” of Oakland Stake members serving in the military. [1] Furthermore, many Mormon service men from other areas were assigned to the eleven military installations in the Bay Area for basic training or were there in transit to their combat assignments. Many of these servicemen and women were impressed with the area, so they returned after the war to become permanent residents. Many others moved from the mountain states to the West Coast for improved economic opportunities.

The formation of new stakes reflected the growth of Latter-day Saint membership. Before World War II, there had been only two stakes in the Bay Area. In 1946, the San Francisco and Oakland Stakes were divided to form the Palo Alto and Berkeley Stakes, respectively. W. Glenn Harmon became president of the Berkeley Stake in September 1946. He had a distinguished legal career after graduating from the Boalt School of Law at the University of California and passing the bar in Utah and California. In 1932 Harmon joined the law practice established by another Latter-day Saint, J. Edward Johnson, in San Francisco five years earlier. It was a partnership that lasted over forty-five years with a simple handshake as a contract. A Boalt Hall and BYU graduate and former BYU student body president, Johnson was also counselor in the original presidencies of both the San Francisco and Oakland Stakes.

In 1956 the two East Bay stakes, Oakland and Berkeley, were realigned into three stakes—Hayward, Oakland-Berkeley, and Walnut Creek. Harmon was released when the Oakland-Berkeley Stake was formed; thus he was the only president the Berkeley Stake had during its ten years of existence, prompting his wife, Wanda, to claim he was the best president the Berkeley Stake ever had!

The Santa Rosa Stake had been formed in 1951 from portions of the Berkeley Stake and mission branches north of the bay. The following year, the southern wards from the Palo Alto Stake and mission branches formed the new San Jose Stake. Then in 1958, the San Mateo Stake was organized on the San Francisco Peninsula. All this growth heightened the need for a temple in Northern California, but at the same time it created enormous pressure on resources, which temporarily postponed achieving that goal.

Factors Putting Plans for a Temple on Hold

The rapidly increasing Church population stimulated interest in having a temple in the Bay Area. But there were other serious needs that had to be met first. These needs required members to commit substantial amounts of money, time, and energy.

The growing number of stakes and wards in the Bay Area all needed facilities to accommodate worship services and other activities. For example, Oakland Stake president Delbert F. Wright (who had succeeded Eugene Hilton in 1949) reported in January 1954 a stake population of 6,600 members in nine wards and two branches. Just one year later, these numbers had risen to 7,500 members in eleven wards and one branch. The Centerville Branch had become a ward, so it needed more ample facilities to accommodate its increased activities and therefore had a building program under way. The San Leandro Ward was created from parts of other neighboring units, so it needed its own building. The Oakland Fourth Ward’s building was under construction. The San Lorenzo Ward intended to build in the spring of 1955 but had to wait until this could be coordinated with plans for a temple. [2] (This was the first mention of coordinating future ward buildings with construction of a proposed temple.) Other Bay Area stakes faced similar pressures.

The formulas of Church versus local funding changed over the years, depending on the type of building involved. Typically, the Church paid sixty percent and the local members forty percent (this would also be the formula for the Interstake Center). On many of these projects, local members could receive credit for voluntary labor, popularly called “sweat equity,” offsetting the local cash assessments. Older members look back on these volunteer experiences as spiritual highlights. Their sacrifices were recompensed by a sense of ownership, accomplishment, and satisfaction from gathering together with other members in a purposeful effort to achieve the Lord’s goals. Church policy was to not dedicate any building until it had been fully paid for. However, buildings were often put into use before dedication.

The Church Welfare Program also placed demands on the Saints. Beginning during the Great Depression of the 1930s, it promoted independence. Each stake was to participate in purchasing and operating a welfare project; these included orchards, farms, canneries, and storehouses. Church members then worked on these projects to provide food and clothing for the needy. Thus implementing the welfare program took away labor and money from other possible activities.

In addition, faithful Church members made various donations in cash. Tithes, 10 percent of a member’s income, supported building, missionary, educational, and other programs Churchwide. Members made an offering equal to or more than the amount saved by fasting for two consecutive meals each month; these fast offering funds were used by wards and stakes to provide for needy members. Then, ward budget donations paid for the cost of local activities, such as building maintenance and cultural and educational programs (particularly for the youth).

Many families contributed what they could, but even devout members reached their limits. Adding contributions to a temple fund would be difficult, even though temples represented the apex of Latter-day Saint worship.

Finally, construction of temples in other areas delayed the building of one in Oakland. In 1949, for example, Church leaders announced the building of a temple in Los Angeles and did not think that constructing two temples in California at the same time was advisable. Construction of even more distant temples caused delays—the Idaho Falls Temple during the 1940s and the Swiss, London, and New Zealand Temples in the following decade.

All these factors delayed plans for a Bay Area temple until the 1960s. Meanwhile, plans for another kind of building in Oakland went forward.

The Oakland “Tabernacle”

In the 1950s, fully implementing the Church programs was very important to Bay Area Saints. Stakes sponsored a variety of cultural, educational, social, and recreational programs, so they needed facilities to accommodate them. Each stake also needed office space and room for occasional regional meetings.

Among early Latter-day Saints, such larger buildings, constructed by a coalition of congregations, had been called “tabernacles.” Hence the term had a Mormon cultural usage in addition to its meaning in the Bible. Typically, tabernacles accommodated meetings of larger groups. Generally, these gatherings were religious, but there were also cultural and civic events. The best-known of these buildings is the Tabernacle on Temple Square in Salt Lake City, with its world-renowned choir and organ.

As early as 1937, a stake fund had accumulated enough cash to purchase a three-acre site at the head of Lake Merritt near downtown Oakland. The stake presidency dreamed of constructing a conference center with facilities for youth activities. These leaders anticipated that even when the stake would grow large enough to be divided, these facilities could serve both stakes. The stake employed an architect who completed preliminary drawings in the early 1940s. [3] However, in 1946 the dream of a stake tabernacle at Lake Merritt came to an abrupt end. The site lay squarely in the path of a new freeway, so the site had to be sold.

In 1954, eight years after the stake had been divided, both the Oakland and Berkeley Stakes proposed building a tabernacle of their own, each contending that the site proposed by the other stake would unduly inconvenience its own members. Berkeley actually found and purchased a building site. [4] In July of that year, President Stephen L. Richards, counselor in the First Presidency, and Elder Mark E. Peterson of the Quorum of the Twelve, met with the two stake presidents. Richards, in a successful effort to resolve the conflict, proposed a joint “tabernacle” on Temple Hill for both stakes. [5] Apparently, this possibility had not been considered before.

When the temple site was first purchased, the most likely access roads were Lincoln Avenue—a local residential street—and Mountain Boulevard, then only a winding country road not suitable for use by large numbers of people. The Church had to negotiate for other parcels to be added to the main site to make access feasible. In the 1950s, Mountain Boulevard became a north-south highway skirting the east side of Temple Hill. At that time, Lincoln Avenue was extended from the Dimond District, passing the temple site to a connection with Mountain Boulevard and Joaquin Miller Park. These two improvements made it possible to develop the site with direct access via Lincoln Avenue.

While many temples stood alone on their property, others did not. For example, Temple Square in Salt Lake City included not only the temple but also the tabernacle, the assembly hall, and a visitors’ center. Thus the proposal to include another building on Oakland’s Temple Hill was in keeping with this pattern. The first structure erected at the temple site would be a tabernacle, which came to be known as the Oakland Interstake Center. The center would have a definite impact on the subsequent building of the Oakland Temple.

The architectural firm Harold W. Burton and Son was selected to design the Interstake Center. Seven years earlier, stake president Eugene Hilton had recommended Burton as the temple architect: “Not only has he had a successful part in planning the Hawaiian and Canadian temples but he has a good practical understanding of the California scene and what is appropriate here.” [6] Furthermore, decades earlier he had been the architect for two landmark stake centers in Los Angeles and Honolulu, so he would be experienced in designing a similar facility for Oakland. The Hollywood (later Los Angeles) Stake Center, or Wilshire Ward Chapel, was dedicated by Church President Heber J. Grant on Sunday, April 29, 1929. Constructed of exposed concrete, it was an outstanding example of California’s art deco architecture. The chapel featured stained-glassed windows, including a large one of the Savior at the front depicting the scripture “I stand at the door, and knock” (Revelation 3:20). President Grant asserted that other than the temples and the Salt Lake Tabernacle, it was the finest building in the Church. It was designated as the “finest cement building in America” by Architectural Concrete in 1933. [7]

Burton’s other outstanding work was the Oahu Stake Tabernacle in Honolulu, Hawaii, dedicated by David O. McKay—then Second Counselor in the First Presidency—on Sunday, August 17, 1941 (less than four months before the attack on nearby Pearl Harbor). Before high-rise apartments and condominiums dominated the skyline, the tabernacle’s 141-foot tower could easily be seen from ships at sea. A prominent feature of the building’s facade is a mosaic of the Savior with welcoming, outstretched arms. Made up of at least 100,000 small ceramic tiles, this masterpiece was the work of Eugene Savage, head of the Art Department at Columbia University. [8]

President Stephen L. Richards was enthusiastic about the proposed Oakland building. He was convinced that it would be effective and could become a model for other joint tabernacle projects Churchwide. He outlined five major features to be included in the building: a 1,700-seat auditorium with provisions for a later addition of 800 seats in a gallery, a stage situated between the auditorium and the reception hall, a chapel and classrooms for one ward, a baptistry near the stake president and high council offices, and a standard basketball court. All these proposals actually became part of the Interstake Center—a rather remarkable achievement. A unique feature was the font room, with its sloping floor and seating for about two hundred people.

The architects met with the Church Building Committee in Salt Lake City on January 14, 1955. Burton presented a model of the proposed building. Although the cost of the Interstake Center would be great, it would be less than the cost of two separate stake buildings, while at the same time the facilities would “far outstrip those possible in a single stake center.” [9] At this time, the structure had the unwieldy title of “The Joint Berkeley-Oakland Inter-Stake Meeting and Recreation Center.”

Site Preparation

For several months there was little visible progress while plans and contract requirements were being prepared. Finally, Gallagher and Burk Inc. received a contract for “filling and grading of building site of the Oakland Temple and Inter-stake Center for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Oakland, California.” [10] Even though the public announcement for construction of the temple occurred only after the Interstake Center was dedicated, it is obvious from this document that plans had gone ahead for construction of a temple well before it was announced. Not included in the contract were plans for the Visitors’ and Family History Center, which would be built over three decades later on the west side of Temple Hill.

The actual dirt moving began in mid-January 1956 and continued for several months, wet spring weather permitting. As Gallagher and Burk sliced off the top thirty-two feet of Temple Hill, they moved 200,000 yards of dirt to Alameda for the construction of Bay Farm Island between the city of Alameda and the Oakland Airport. Eight pieces of heavy earth-moving equipment and seventeen large hauling trucks were used. The leveling was completed in May.

Fund-raising

Plans to raise funds for the Interstake Center and the attached ward building were completed in September 1955. The total cost of the building and furnishings was estimated at $750,000 (over $5 million today). For example, Berkeley Stake’s share of the cost of the building was $125,000. The stake already had $50,000 in funds as a credit, so the remaining cost to be raised for the Interstake Center was $75,000, plus an additional $25,000 for a stake welfare farm. Norman B. Creer of Concord Ward then worked out a general plan of suggested payments based on each individual’s ability. [11] Berkeley Stake began fund-raising on Sunday, September 11, 1955. In twos, the stake presidency and the twelve members of the high council spread out over the entire stake. Creer’s plan of suggested contributions was placed in each person’s hands at meetings held that Sunday. Many pledge cards were signed at the meetings and others mailed theirs in during the following three days. The results indicated that the total of $100,000 would be raised in six months. [12]

O. Leslie Stone, president of the recently combined Oakland-Berkeley Stake, became chair of the Interstake Center Building Committee. He emphasized that Church policy required that the “Church Inter-Stake Meeting and Recreation Center” could not be dedicated until the stakes’ share of the cost was paid in full. Construction was expected to begin early in 1957. The Church made a $300,000 loan to the stakes to enable the project to move forward.

Several notable and unique fund-raising events were produced. For example, a Polynesian group sponsored a south-seas feast and dance festival. This became very popular and was repeated in several wards. One group of actors, the Temple Hill Minstrels, received a lot of attention in the Messenger in the fall of 1956. They toured every ward in Berkeley Stake to raise money for the “Berkeley-Oakland, Walnut Creek, and Hayward Interstake Center” (the 1956 reorganization of the Oakland and Berkeley Stakes into three stakes necessitated this change in the Interstake Center’s name). [13] The Minstrels completed a nine-show run and earned close to $4,000 for the Interstake Center building fund. Profits from selling boxes of Newton apples also went to the building fund.

The Hayward Second Ward scheduled a “sacrifice month” in which ward members were invited to go without “conveniences, luxuries and entertainment” in order to donate to the building fund. Ralph Lane, first counselor in the Alameda Ward bishopric, and Carl Lane, who was not a member of the Church, were paid to build pulpits, sacrament tables, and other furnishings for the ward chapel portion of the Interstake Center; they then donated their earnings. [14]

The sale of two ward buildings was connected with the Interstake Center’s construction. The Evergreen Baptist Church purchased the Oakland Ward’s building on MacArthur Boulevard and Webster Street. The reasons given for the sale were a shift in the population in the Oakland area, lack of parking, undesirable traffic on MacArthur Boulevard, and the building’s inability to meet the needs of the enlarging programs of the Church. Nevertheless, a baptismal font in the basement made this a desirable purchase for the Baptist group. The Dimond Ward meetinghouse was also placed for sale for similar reasons. The Oakland Ward then shared the Claremont Ward’s chapel until the ward facilities at the Interstake Center became available. As a result, before the Interstake Center was completed there were only two baptismal fonts left in the East Bay Area—in the Walnut Creek and Centerville Ward buildings. The proceeds from these sales offset the cost of the ward portion at the new Interstake Center. [15]

Groundbreaking

Groundbreaking ceremonies were planned for July 20, 1957—the Saturday preceding Pioneer Day (the anniversary of the Mormon Pioneers arriving in the Salt Lake Valley July 24, 1847). Both events would be celebrated together on Temple Hill—the Pioneer Day celebration followed by the groundbreaking.

Wielding ceremonial shovels were President Stephen L. Richards, First Counselor in the First Presidency; Elder Mark E. Peterson, of the Council of the Twelve; Presidents Milton P. Ream, Norman B. Creer, and O. Leslie Stone of the Hayward, Walnut Creek, and Oakland-Berkeley Stakes respectively; Bishops Frank C. Higham and M. Dee Smith of the Oakland First and Third Wards, which would meet in the building; and Wendell B. Mendenhall, chair of the Church Building Committee. All were dressed in suits; Richards and Peterson wore fedoras as well.

In an address at the ceremonies, President Richards placed an eternal perspective on the project:

I am glad this building is to be located so near to where the Temple will stand. And I hope when it is used for the recreational and social activities of youth, that every young man and every young woman who are members of our faith will look out of the windows of this building toward the lofty edifice which is to be built near to it, and remember that the only way in which to form an enduring and compatible and promising partnership, for this time, this life and for the hereafter, is to have that union sealed by the power of the Holy Priesthood for time and for all eternity.

The Lord bless you in this undertaking and guide and direct you and extend your vision; that every brick that is laid, that every shovelful of mortar, every bit of cabinet work and all that shall go into the construction of this building shall be dedicated—dedicated by your faith, by your effort, to a great and noble cause, which commends our esteem, our respect and our eternal devotion. [16]

Construction

By November 1957, the footings had been poured and brick was being laid. The Interstake Center building required some 400,000 bricks. Brick is not normally the building material of choice in an earthquake-prone region. The contractor, Woodward and Wilson, used a grouted brick construction that sandwiched reinforcing steel and concrete between two brick layers. This type of construction was based on atomic blast tests in Nevada that indicated that, of all construction types, this one held up best to atomic blast shock waves. Crown Electric, owned by Church member Bill Powell, constructed the electrical system. In all there were about 120 subcontractors that worked on the Interstake Center. [17]

The construction superintendent, James Everett, performed admirable service and brought the project to completion on time—in spite of dealing with heavy springtime rains. He was described as honest and dependable in handling supplies, contractors, and employees. Thys Winkel became the project clerk. His performance went far beyond his assignment, and he became almost legendary in his thoroughness in every matter connected with the project. He was on the job from the very beginning and continued after the building’s completion, when he was named chair of the Interstake Property Management Committee. [18]

With building construction well under way, it was time to select a planning committee from the three participating stakes. The three stake presidents formed the core of the committee: O. Leslie Stone as chair and Milton Ream and Norman B. Creer as members. Paul Warnick was named chair of the finance committee and Elmo R. Smith the legal advisor. This executive committee and their ten subcommittees were to plan the finishing touches on the building. In January 1958, J. Howard Dunn became project manager in order to include some local people in managing the actual construction.

The Final Push to Completion

At the end of 1957, President Stone reminded members, “Although we are ahead in construction, we are behind in financing.” [19] He therefore invited all to visit the site as a means to boost their commitment to contributing the needed funds.

By June 1958, the estimated total was $1.5 million (over $11 million today)—double the original estimate. As of June, 55 percent of the local funds had been received. A merchandise carnival, variety show, buffet dinner, and an all-you-can-eat pancake breakfast were held that month. Manufacturers donated merchandise as a community service. In spite of these successful events, construction continued to be ahead of donations. At this point, President Stone disclosed the $300,000 construction loan obtained from the Church to help finance this huge project. [20] The total cost had climbed to $1.9 million, which seemed like an excellent incentive to hurry and pay off the building allotment before it rose even higher.

Now that the building was in its final stages of completion, the matter of its name became the subject of discussion. The designation “Oakland Tabernacle” did not receive much acceptance, so the term “Tri-Stake Center” was coming into vogue. [21] There were many other titles at various times, but it is now popularly known as the Interstake Center (with or without capitalization or hyphenation).

Even though the building was not completely finished, the first meetings occurred during December 1958 in the ward chapel attached to the Interstake Center. On the last day of that same month, there was a stake New Year’s Eve dinner-dance, attended by 2,000 people, in the center’s large cultural hall. The buffet dinner was prepared in the center’s large kitchen and served smoothly as the huge crowd passed through the line. [22]

Then, on January 25, 1959, approximately 5,000 people gathered at the Interstake Center to offer thanks for the completion of the building. This was a thanksgiving service, not a dedication, since all of the money had not been raised. President Stephen L. Richards and Elder Mark E. Petersen once again came to Oakland for these services. Both stressed the spiritual benefits that would result from the use of the building. [23]

Various groups began to hold final fundraisers to “pay off the mortgage.” Eddie Te’o directed a Samoan feast sponsored by the Rodeo Ward. There were 450 people in attendance. Oakland Ward presented a “Festival of Stars”—a show produced by William L. Stoker, a member of the San Mateo Stake presidency and a professional musician and producer.

The final payment to complete the fund-raising effort—$7,800—was made August 8, 1960, by the Hayward Stake. In addition to contributing funds for the Interstake Center, the East Bay Saints “built a fine Bishop’s Storehouse” to further the Church’s welfare program, and the payment of tithes increased. [24]

Individuals and families also contributed to the Interstake Center project. A majestic pipe organ, costing $52,000, was installed in the center’s main auditorium; general Church funds covered $28,000, and the Stone family contributed the balance. This family also donated the Baldwin Grand Piano for the ward chapel (in memory of their late son, Reed), provided the large refrigerator and table settings for 600 to the Interstake Center kitchen, and furnished the stake presidency’s office. [25]

A genealogy library in the Interstake Center also became a reality. A facility of this sort had been discussed for years. Besides donated books and a few microfilms, the library acquired a microfilm reader, a long carriage typewriter for filling out legal-size forms, and a copy machine. From this relatively modest start, a permanent home for the Oakland Family History Library was achieved. [26]

Dedication

As a welcome culmination to years of work by the Bay Area Saints, Church President David O. McKay, then age eighty-seven, personally traveled to Oakland to dedicate the East Bay Interstake Center on Sunday, September 25, 1960. Some 5,536 people were assembled inside the building. Others gathered outside on this warm and sunny afternoon. This was the largest LDS audience ever to congregate in Northern California. In his remarks, President McKay noted that his wife’s grandparents had been part of the group that sailed around Cape Horn aboard the Brooklyn. [27] He also acknowledged the Saints’ anticipation of a temple. He reported that since arriving at the San Francisco airport, “I think I have heard ‘Temple site’ mentioned about five or six times. President Stone took us around to show us right where it is and where it should be.” The prophet described the Interstake Center as “magnificent” and “wonderful,” regarding it as “a tribute to the foresight, to the judgment, and principally, to the inspiration that have attended these three [stake] presidencies and you people who have subscribed so willingly, gratuitously, to the erection of such a fine center.” President McKay acknowledged that eventually there would be a temple “overshadowing” the Interstake Center. “Those young people who look out upon it will have that feeling of sanctity and reverence in their heart” springing from an awareness that God’s ultimate purpose is to “bring to pass immortality and eternal life” of His children. [28]

During the dedicatory service, the magnificent pipe organ was heard for the first time, with Robert Douglas at the console. Nico Snel conducted a three-stake chorus. The organ contained eighty-six ranks of distinctive tonal quality. A dedicatory program praised it as “a superb recital and worship service instrument, responsive to all organ literature of the past 450 years.” Swain and Kates Inc.—a company with over 200 years of experience in West Germany—designed the organ. Dr. Alexander Schreiner, chief organist at the Salt Lake Tabernacle, would play at the dedicatory recital two months later, on November 17 and 18, 1960. [29]

To commemorate the opening of the Interstake Center, the three East Bay Stakes published a 76-page booklet entitled Triumph. The booklet included two historical articles written by Eugene Hilton, former president of the Oakland Stake, and W. Glenn Harmon, first president of the Berkeley Stake. It also contained many pictures depicting the construction and facilities of the new building. The booklet’s cover featured a drawing of the Interstake Center with an ethereal sketch of the longed-for temple in the clouds above. Many attending the dedicatory services hoped that seeing this cover might prompt President McKay to announce specific plans concerning the temple, but the time was not yet. The people of Northern California were undoubtedly now ready to build a temple to the Lord, but they would have to wait four more months for the eagerly anticipated announcement.

The Center’s Impact

An experience that unfolded just a few years after the Interstake Center’s dedication illustrates the positive impact the Interstake Center had. Thomas R. Stone, son of stake president O. Leslie Stone, was presiding over the Latter-day Saint mission in French Polynesia. Thomas Stone had been applying for permits to build a new chapel there, but government officials, suspicious about potentially political uses of a church building that included classrooms, were dragging their feet. On May 3, 1964, Pan American Airways inaugurated direct service between California and Tahiti. Because the Church was one of Pan Am’s largest customers, members of the First Presidency were invited to be guests on the inaugural flight; they, in turn, asked mission president Stone and his wife to represent them. Thus Tom and Diane Stone were part of a group of over thirty leaders that included high government officials, religious leaders, and their spouses.

Upon arriving in San Francisco, the group was over an hour early for a reception at the East Bay’s Claremont Hotel, so Tom Stone suggested they stop at Temple Hill. At first, the Pan American escort was hesitant to stop at a religious site, but then agreed when he learned it would not be too much out of the way and would afford a spectacular view of the bay. Just as the group was getting off the bus to enjoy the view, stake president Stone drove up, although there had been no plan for him to meet his son and the group from Tahiti there. He offered to show them the new Interstake Center, of which they were very proud. The visitors were impressed with the 2,200-seat auditorium with its stage that rivaled the San Francisco Opera House in size. An organist happened to be practicing for his performance the following Sunday, so the cultured French visitors were treated to and enjoyed a fifteen-minute private recital. As they continued their tour, they walked through the cultural hall, which was large enough to accommodate six basketball courts. When they entered the ward portion of the facility, they saw classrooms and asked what they were for. President O. Leslie Stone explained they were where children and young people were taught religious lessons from the Bible. Translation was provided as they entered the room where a Relief Society testimony meeting was in session. As the visitors were about to leave, the leader of the group asked for permission to say a few words. He apologized for interrupting the sisters’ beautiful meeting but added, “We want all of you to know how delighted we are to have your church in French Polynesia. Its teaching the youth to be active and live according to high morals is a blessing to our country.” [30]

President Stone then invited the group to come over to his home, which was not far away. Although his wife, Dorothy, did not know they were coming, she was prepared to welcome them warmly into their beautiful home. This would be the only private family home the group would visit while in America.

Back in Tahiti, Tom and Diane Stone now had a friendly first-name relationship with all the government and religious leaders who had been on the trip. They promptly received the permits for their new chapel. It was finished and dedicated just two weeks before Tom completed his service as mission president. In subsequent years, relations between the Church and government were much more cordial. [31]

Notes

[1] Oakland Stake anniversary commemorative booklet.

[2] Messenger of Northern California (Berkeley, CA: January 1955), 3 (hereafter cited as Messenger).

[3] W. Glenn Harmon and Wanda B. Harmon, “Oakland Branch 80th Anniversary,” draft 5, Oakland Stake Archives, 15–19.

[4] Harmon and Harmon, “80th Anniversary,” 20.

[5] Messenger, January 1955, 1.

[6] Eugene Hilton to First Presidency, May 3, 1947, MS 13944, folder 11, Church History Library.

[7] Orton, More Faith Than Fear, 84–91.

[8] Thomas E. Daniels, “Honolulu Tabernacle to Be Renovated,” Church News, April 26, 1997.

[9] Messenger, January 1955, 3.

[10] Union Pacific Insurance Company, Performance and Payment Bond No. 259898, November 1955.

[11] Messenger, September 1955, 12.

[12] Messenger, October 1955, 12.

[13] Messenger, October 1956, 1.

[14] David W. Cummings, Triumph: Commemorating the Opening of the East Bay Interstake Center (n.p.: Hayward, Oakland-Berkeley, and Walnut Creek Stakes, 1958), 30, 45.

[15] Messenger, January 1957, 11.

[16] Triumph: East Bay Inter Stake Center (n.p.: commemorative booklet, 1959), 11.

[17] Triumph, 70.

[18] Triumph, 20.

[19] Messenger, December 1957, 1.

[20] Messenger, June 1958, 1.

[21] Messenger, January 1959, 1.

[22] Triumph, 16.

[23] O. Leslie Stone, “History: Covering Years 1903–1960” (distributed primarily among Stone family, copy in Brigham Young University Library), 38.

[24] Stone, “History,” 39.

[25] Stone, “History,” 38.

[26] Messenger, March 1960, 16.

[27] Dr. John Rogers Robbins was the ship’s doctor aboard the Brooklyn. However, he did not stay long in San Francisco. His family returned to New Jersey via the Isthmus of Panama. Then in another major move he traveled overland to Salt Lake City in 1853. He was the grandfather of Emma Rae Riggs McKay, the wife of Latter-day Saint President David Oman McKay. A simple version of this complicated story is found in Richard H. Bullock, Ship “Brooklyn” Saints (Ship Brooklyn Association, www.shipbrooklyn.com), 209–14.

[28] “Full Text of East bay Address by Pres. McKay Dedicatory talk at East-Bay Center,” Church News, October 1, 1960, 18–19.

[29] Dedicatory program of the enlarged pipe organ, Friday, April 12, 1968. Sponsoring stakes: Concord, Fremont, Hayward, Oakland-Berkeley, San Leandro, and Walnut Creek.

[30] Interview with Thomas R. Stone, November 12, 2010, recording in possession of Richard Cowan; see also S. George Ellsworth and Kathleen C. Perrin, Seasons of Faith and Courage: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in French Polynesia A Sesquicentennial History, 1843–1993 (Sandy, UT: Yves R. Perrin, 1994), 196–98; Evelyn Candland, An Ensign to the Nations: History of the Oakland Stake (Oakland California Stake, 1992), 55–56.

[31] Stone; see also Ellsworth and Perrin, Seasons of Faith and Courage, 196–98; and Candland, An Ensign to the Nations, 55–56.