Introductory Essay

A Life’s Story

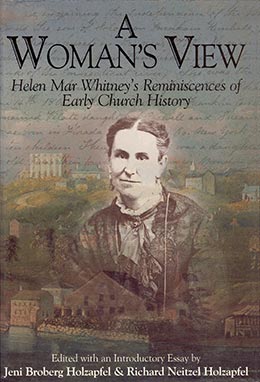

Jeni Broberg Holzapfel and Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, eds., A Woman’s View: Helen Mar Whitney’s Reminiscences of Early Church History (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1997), ix–xlviii.

Helen Mar Whitney was a courageous woman living in an extraordinary time when the LDS Church and its members were subject to intense criticism and persecution. Fortunately for us, she took pen and paper in hand before she died to describe vividly her times as a member of the Latter-day Saint Church during its first two decades of existence in a series of articles published in the Woman’s Exponent (beginning in May 1880 and concluding in August 1886).

In addition to this series of recollections, Helen Mar wrote letters and poems for publication in the same newspaper between 1 October 1880 and 1 March 1891, adding important details of her life and activity during this period. The complete collection of articles was brought together in 1976, a copy of which is available in the LDS Church Library. [1]

All in all, Helen Mar’s writings published in the Woman’s Exponent in the 1880s represent a hope that the efforts to tell her story will be helpful to the rising LDS generation which was both physically and temporally removed from the Church’s early history and to non-Mormons interested in trying to understand the Mormon point of view—in particular, a woman’s view of how the Church membership arrived at its present state of belief and practice.

Helen Mar Whitney’s Reminiscences

Helen Mar notes in her first article published in the 15 May 1880 issue of the Woman’s Exponent, “This has been proclaimed as a year of jubilee.” [2] She continues: “I truly rejoice that I have had the privilege of being numbered with those who have come up through much tribulation and gained a knowledge for myself that this is the work of God which neither wealth nor worldly honors could tempt me to part with. This is a world of sorrow and disappointment. Life and everything here is uncertain, but beyond is eternal life and exaltation. The experience of the Latter-day Saints during the past fifty years has disciplined and prepared them in a measure for the great and wonderful changes which are coming, while those who know not God are groping as it were in midnight darkness.” [3]

Helen Mar chose to include only specific periods of her life in the main portion of her reminiscences. Few nineteenth-century reminiscences are complete autobiographies; although they tell only a part of the writer’s larger story, they generally capture at least one significant aspect of the individual’s life. In LDS autobiographies, focal points generally include events such as birth, conversion, and gathering. Many of the autobiographies found in such repositories as the LDS Church Archives, Utah State Historical Society, and the Harold B. Lee Library end once the individual has crossed the plains, as though the really noteworthy things happened before getting to Utah. Even Eliza R. Snow’s diary ends shortly after her arrival in the Great Basin. Helen Mar focused on the time when her children and grandchildren did not know her.

In the first two articles, Helen Mar recounts the difficult days of the Missouri persecution (1838–39) and then confesses in her third article, published in the 15 June 1880 issue, “When I first commenced these reminiscences, I only gave a short sketch and did not think to continue them, but having been urged to write more, I will.” [4] She also notes another motive in publishing her life story: “I can truly say that I feel an interest in the welfare of all, and if some of the incidents of my life could impress the minds of others, as they have my own, I would feel amply repaid for writing them. There seems to be a great curiosity in the minds of strangers about the ‘Mormon’ women, and I am willing, nay, anxious, that they should know the true history of the faithful women of Mormondom.” [5]

Apparently, Helen Mar was responding in part to published reports about the Latter-day Saints that were sweeping the nation at the time. [6] From the outside, Mormonism appeared as a monolithic institution where all women were enslaved by polygamy. However, Helen Mar demonstrates from the inside that LDS women’s lives were filled with a variety of experiences and freedoms. Sometimes her response to outside criticism was specific, as was the case when she wrote to refute attacks by Reverend J. M. Coynen and Joseph Smith III. [7] She, like other Latter-day Saint women during the same period, took the time to present to the world a simple but honest account of her life, hoping to ameliorate the hatred engendered by the latest rounds of anti-Mormon sentiment circulating through the eastern press—sentiment that eventually had tremendous negative impacts on the lives of Latter-day Saint women in the West. [8] In this regard, Helen not only acknowledged her belief in plural marriage but became, through her writing, one of its staunchest supporters. Courageously, she steps forward to defend her church and herself in print. The deep feeling engendered by such criticism and publicity is demonstrated in a letter Helen Mar wrote to the editor of the Woman’s Exponent in October 1880, just a few months after she began her series on Church history:

When reading in last evening’s [Deseret] News the proceedings of our would-be tyrants, I confess that for a moment I felt warmed up and really indignant. It seems that we “poor, down-trodden women,” whose sorrows and sufferings called forth so much PITY until it was disgusting to every true hearted “Mormon” woman, have disappointed our very “liberal” and sympathetic friends! We really love our husbands and prefer to be governed by our brethren instead of by our acknowledged enemies. We have also proved true to the principles of our religion, which is far dearer to us than are our lives, or anything else without it; and it seems we have become a power to be dreaded, and now the poor hypocrites are trying to undo what they have done. “To want to and can’t” is their unenviable condition and will continue to be if we will be humble and united.

We shall see the hand of God in this, as we have in every other move made by our enemies. They can do nothing against us, but for us. These trials are necessary to separate the dross from the pure metal. We can look back through all our mobbings and drivings and can see the hand of God in every move. Instead of our enemies destroying us as they hoped and expected to do, we have become rich and popular and they are now filled with envy, and are really the ones to be pitied, for they are trusting in their own strength as did Goliath, and we trust in the Almighty, who will show forth his power in behalf of his people. [9]

In several sections of these reminiscences, one can see that current political and social realities existing in Utah Territory and Washington D.C. in the 1880s constrained Helen Mar to respond by telling her story—a woman’s story—from her point of view. Among the stories she chose to include in this important series on Church history, none is more emotionally laden than that of the introduction of plural marriage, a very public issue in the 1880s. Apparently, Latter-day Saint women were at first reluctant to respond publicly, but as pressure continued to mount, they began to defend themselves and their rights to practice their religion as they chose. Pressure from the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, which denied Joseph Smith ever practiced or taught plural marriage, added to the need to respond. In particular, Helen Mar challenged Joseph Smith III to read her articles printed in the Woman’s Exponent entitled “Scenes and Incidents in Nauvoo” because they “contain nothing but truths and are calculated to destroy error.” [10]

Additionally, Helen Mar revealed the reluctance of plural wives to respond to critics publicly: “A feeling of delicacy takes possession of the author in attempting to perform a labor of this nature.” [11] Nevertheless, she wanted “to open the eyes and throw light upon the minds of those who are laboring under false impressions concerning the religion and works of the Latter-day Saints of Utah.” So she took up the challenge and offered her story to the world—a world that often ridiculed and degraded Latter-day Saint beliefs in print, as well as from the pulpits and podiums in churches and halls throughout the nation.

The story of plural marriage did not begin in Salt Lake City in the 1880s. For Helen Mar, it began in Nauvoo in the 1840s—a place and time with which she was intimately acquainted. Her personal remembrances of those days constitute an important source that, taken together with other first-hand accounts by participants, provides a more complete view of the introduction of one of the most distinctive features of nineteenth-century Mormonism. Whether unpublished private documents or published public documents, these accounts are important historical records that must be taken seriously by the modern reader or historian.

Plural Marriage

In the articles dealing with the emotionally charged issue of plural marriage, Helen Mar reveals that she was initially unaware of her father’s practice of the principle, as it was called, in Nauvoo. Although forty years had elapsed since Heber C. Kimball first told her of plural marriage, she recalls vividly her feelings at the time: “I remember how I felt, but which would be a difficult matter to describe—the various thoughts, fears and temptations that flashed through my mind when the principle was first introduced to me. . . . [S]uffice it to say the first impulse was anger.” [12] Helen Mar adds: “My sensibilities were painfully touched. I felt such a sense of personal injury and displeasure . . . but [he] left me to reflect upon it for the next twenty-four hours, during which time I was filled with various and conflicting ideas. I was skeptical—one minute believed, then doubted.” [13]

She asks for a sympathetic understanding for the plight of the sister-Saints who moved forward to practice a principle they believed came from God:

What other motive than real faith and a firm conviction of the truth of this principle could have induced them to accept and practice a doctrine so opposite to their traditions and the rigid training received from their sectarian parents and ancestors? Who would wish to become objects of derision, to have their friends and associates turn the cold shoulder, and be subjected to the sneers and scoffs of persons prejudiced by the extravagant tales spread by certain ones who, while professing friendship and faith in the principle, were two-faced and treacherous to their brethren and sisters; the latter, though virtuous and modest in their demeanor, and their motives as noble and pure as were those of Ruth and Naomi, had to silently bear the title of lewd women. [14]

Helen Mar also notes in another article in the series that “no earthly inducement could be held forth to the women who entered this order [plural marriage]. It was to be a life-sacrifice for the sake of an everlasting glory and exaltation.” [15] Her initial reaction was typical of many, both men and women, when plural marriage was first introduced. [16] Eventually, she came to accept the new teaching and consented to be sealed to Joseph Smith as a plural wife some time in May or June 1843. [17]

Following the Prophet’s death, she married Horace Kimball Whitney, apparently her teenage sweetheart. He eventually married additional wives, placing Helen Mar in a polygamous relationship again. In these articles, she not only justified herself and her own choice to live the principle but also spoke for all Latter-day Saint women—a duty she felt bound to fulfill by defending the principle. In this particular regard, one can only imagine the strong emotions Helen Mar felt when she wrote about the day in February 1846 when she finally married Horace. She recalls: “At early twilight on the 3rd of February a messenger was sent by my father, informing H. K. Whitney and myself. . . that we were to present ourselves there [the Nauvoo Temple] that evening. The weather being fine we preferred to walk; and as we passed through the little graveyard at the foot of the hill a solemn covenant we entered into—to cling to each other through time and, if permitted, throughout all eternity, and this vow was solemnized at the holy altar.” [18]

She had been sealed to the martyred Prophet three years earlier for time and eternity because of duty and family loyalty, especially out of deference to her father’s wishes. Now, Horace stood as proxy for Joseph Smith in the Nauvoo Temple to have the ordinance reconfirmed. Apparently, Helen Mar stood proxy for a woman, Elizabeth Sikes, who was sealed to Horace for eternity. Then, they both kneeled together to be “sealed” for time on this day. [19] Helen Mar’s desire to “cling to [Horace] through time and . . . throughout all eternity” was a romantic wish. She is silent on this subject, except for this brief reference. Her choice leaves the modern reader with many questions. She clearly was struggling with emotional and spiritual ambiguities.

Apparently, the Kimballs, Youngs, and Whitneys were fully aware of Helen Mar’s marriage to Joseph Smith, but the general public in the 1880s was not. Helen Mar, like many other plural wives of the Prophet, was not anxious to publicly declare her relationship in this matter. She makes no mention of the sealing in these articles, in the brief autobiographical chapter in Representative Women of Deseret, nor in the two important pamphlets on the subject published in 1882. [20] Apparently, the first sympathetic public announcement of her marriage to Joseph Smith was Andrew Jenson’s listing of the Prophet’s plural wives in 1887. [21] Helen Mar’s marriage to Joseph Smith was also recorded publicly in her son’s biography of Heber C. Kimball, published in 1888. [22] There are two anti-Mormon references to Helen Mar’s marriage to Joseph Smith. [23]

Within a few years after vigorously defending the principle in print, Helen Mar confronted her feelings about polygamy when President Wilford Woodruff issued the 1890 Manifesto, which began the process of ending new plural marriages. [24] Two weeks later, it was her son, Orson F. Whitney, who read the Articles of Faith, including the one regarding “obeying, honoring, and sustaining the law,” and the Manifesto to the congregation attending the historic conference in October 1890.

The Story Line of the Reminiscences

In her articles in the Woman’s Exponent, Helen Mar tells the story of the “last days in Nauvoo” and the great exodus of the Latter-day Saints into the Iowa wilderness. She utilizes Jane Taylor’s diary to help reconstruct her own departure from Nauvoo on 16 February 1846, just at sundown:

“Helen Kimball, daughter of H. C. Kimball, rode alongside of our wagon until she became so cold that she could not sit on her pony. She stopped and we gave her some wine, and Brother Dickson kindled a fire, and we sat around and warmed ourselves. We reached the camp at Sugar Creek about seven o’clock.” This, like a thousand other indicents, had passed from my memory till Sister Taylor reminded me.

The pony that I rode belonged to my brother Heber. It was first purchased for William from a lady in Illinois, who had named it “Happy go lucky,” but William having grown too large and heavy for it gave it to Heber. It was a gentle little animal and stood about three feet and a half high. Many a happy go lucky ride I had taken over the prairies, and when it paced or galloped it was as easy as a cradle. At Sugar Creek father’s men had pitched a tent and put up a sheet iron stove at one end, and great log fires were burning all through the camp. When we had warmed ourselves we made our beds upon the ground and laid down with grateful hearts for so comfortable a shelter, and slept soundly till morning. The snow was deep so that paths had to be made with spades between the wagons and tents. Camping out increased our appetites so that our picnic was very nearly consumed before the camp was ready to leave Sugar Creek. We had cooked up a great amount of provisions, consisting of roasted chicken, beef, boiled hams, pork and beans, bread, rusks and many other eatables, besides sea biscuits and crackers, which we could eat and eat and still be hungry. [25]

Another story Helen Mar chose to tell involves details regarding the exodus from Nauvoo and the incredible trek across Iowa in 1846. Utilizing her husband’s diary, Helen Mar provides a detailed account of that journey, interspersed with personal reflections. Additional resources add depth to her story of “Our Travels Beyond the Mississippi.”

The refugees gathering on the banks of Sugar Creek, Lee County, Iowa, officially began the next leg of the journey on 1 March 1846, when groups of Saints left Sugar Creek and followed an old and established territorial road that eventually led them to less-developed roads and American Indian trails across Iowa. By 3 March, Helen Mar passed through Farmington and encamped. She recalls, “[T]he mud made traveling almost impossible.” [26] The trek across Iowa was long and hard—it took Brigham Young an incredible 131 days to complete the 310-mile trek from east to west. By comparison, the last leg of the journey took 111 days to cover 1,050 miles from Winter Quarters to Salt Lake. Helen Mar writes: “I remember how nearly forlorn I felt some of the time during those dismal, stormy days; being in Bp. Whitney’s camp I was separated from my dear mother by an almost impassable road.” [27]

However, there were moments of celebration and recreation on the road west. “The inspiring music by William Pitt’s brass band, which was organized into companies of tens to travel together,” she recalls, “often gladdened the hearts of the Saints, and helped greatly to keep their spirits from sinking.” [28] She also notes that “there was a great amount of sympathy manifested by the people as we traveled through Iowa. Many visited our camps, and wherever the companies stopped our men were able to find employment.” [29]

By 23 April, a group of pioneers made their first permanent camp, called Garden Grove, and then established another one, which was named Mount Pisgah. The first pioneer group left Mount Pisgah on 1 June, following another Indian trail to the Missouri River Valley and a region known as Council Bluffs. That region, a fifty-mile radius around several trading posts, was an important gathering place of native people. Of course, the winter snow and spring rain eventually provided the Saints with nature’s bounties. Helen Mar recalls, “The heat of the weather was now at its height, and the whole country around abounded in strawberries, raspberries and blackberries, and other fruit indigenous to the county.” [30]

By 1 August, Church leaders made the decision that the Saints should winter in the Missouri River Valley—ten thousand of them. Helen Mar, like many other Saints, settled into their winter retreat, waiting for the following spring when they hoped to begin the last leg of their journey to a new promised land, far in the West.

Helen Mar Whitney’s Family Relationships

Throughout her writings, including the reminiscences, Helen Mar mentions family members. A brief review of her immediate family relations illuminates the complex and interesting structure of the Kimball and Whitney households.

Helen Mar was the third of nine children born to Vilate and Heber C. Kimball. The Kimballs’ first child, Judith, died shortly after her birth in 1823. Their second child, William Henry, was born in 1826. Helen was born 22 August 1828. A fourth child, Roswell Heber, was born in 1831, but he died as an infant.

The family moved from Mendon, New York, to join the Saints in Kirtland, Ohio, in September 1833 when Helen Mar was five years old. A fifth child, Heber Parley, was born to the Kimball family two years after their arrival in Kirtland in 1835. During the following year, Helen Mar was baptized by “Uncle Brigham” in the cold Chagrin River. When she was nine years old, she and her family left their home in Ohio in July 1838 for Far West, Missouri, the new Mormon gathering place. Within six months, they were on the move again, seeking refuge in Illinois following the “Mormon War” in northern Missouri. A sixth child, David Patten, was born in 1839 to Heber and Vilate Kimball. In 1845, a seventh child, Brigham Willard, was added to the Kimball family in Nauvoo.

During the following year, Helen Mar married her teenage sweetheart, Horace K. Kimball; and, within a few days, the young couple left Nauvoo for Iowa.

Along with thousands of other Saints, the Kimball and Whitney families settled in the Missouri River Valley. Here, at Winter Quarters, an eighth child, Solomon Farnham, was born to Heber and Vilate Kimball in 1847. The advance company, which included Helen Mar’s husband, Horace, left Winter Quarters to make its historic trek to the Great Basin in April. Later, on 6 May, nineteen-year-old Helen Mar bore her first child, a stillborn. Upon Horace’s return, the couple began making preparations to leave the Missouri River Valley for Utah in the spring of 1848. On the way to Zion, Helen Mar gave birth to William Howard on 17 August 1848 while resting at the Sweetwater in western Wyoming. The child died a few days later on Helen Mar’s twentieth birthday. The young couple continued on to Salt Lake City, arriving 24 September 1847. Nearly a year later, Helen Mar completed her third pregnancy on 1 September 1849. The child, Horace Kimball, died on the day of his birth.

In January 1850, Helen Mar’s mother bore her last child, Murray Gould (Helen Mar’s last full sibling). Just as Vilate ends her child-bearing years, Helen Mar begins; thus, mother’s and daughter’s child-bearing years overlap. Both are mothers with small babies at the same time.

Of course, Helen Mar had many half-siblings because her father had begun living plural marriage in Nauvoo. These half-siblings played an important role in Helen Mar’s life, as they pop up all over the place in her writings, especially in the diaries.

On 9 October 1850, Horace married Lucy Amelia Bloxham, who later seems to fade away mysteriously from the story.

Three years later, Helen Mar finally gave birth to a child who would survive infancy, Vilate Murray, born 2 June 1853. Two years later, Orson Ferguson was born on 1 July 1855. Horace married his second plural wife, Mary Cravath, on 1 December 1856. Mary had a large family; her children lived close to Helen Mar, and the families seemed to live harmoniously with each other.

Helen Mar’s sixth child, Elizabeth Ann, was born 27 November 1857. Four other children were born during the next few years: Genevieve on 13 March 1860; Helen Kimball on 24 March 1862; Charles Spaulding on 21 November 1864; and Florence Marian on 4 April 1867. During the same year, Helen Mar’s mother died of scarlet fever (22 October 1867), and Heber soon followed her (22 June 1868).

Helen Mar’s last child, Phebe Isobel, was born 24 September 1869. Within five months, however, Helen Mar’s first surviving child, Vilate Murray, died (5 February 1870). And on 23 July 1874, her daughter, Phebe Isobel, died just before reaching five years of age. Helen Mar began to record her life story shortly thereafter, and the first installment appeared in print in 1880. While she spent countless hours reading primary sources and examining her own memory, she continued to experience the daily challenges of life—sickness, physical struggles, and deaths of loved ones. Her husband, Horace, died of dropsy on 22 November 1884; and her son, Charley Spaulding, committed suicide or died of a gun accident in July 1886.

The Significance of the Series

Helen Mar’s recollections of early Church history cover a wide range of topics, recounting not only stories of people and places important to the Latter-day Saint heritage but preserving extracts from discourses, letters, diaries, and public documents. These articles give insights into such topics as the family organization of some of the leading members of the Church and nineteenth-century practices of washing of feet, speaking in tongues, adoption, baptism for the dead, healing baptisms, blessing of children, temple endowments, and sealings. They reveal Latter-day Saint attitudes regarding the sabbath day, dancing, education, arts, music, theater, and the raising of children. Finally, the recollections help uncover the contours of life in the Mormon settlements in the 1830s and 1840s.

Helen Mar’s series is a “gold mine” for woman’s history. She was so perfectly placed—daughter of Heber C. and Vilate; “niece” of Brigham Young; wife of Joseph Smith; daughter-in-law of Newel and Elizabeth Whitney; friend of Eliza R. Snow and her Smith sister wives; “niece” of the Kimball plural wives; and half daughter-in-law of Emmeline Wells. She is the key source for the later lives of two obscure plural wives of Joseph Smith—Flora Woodworm Smith Grove and Sarah Lawrence Smith Kimball. Flora’s later life would be totally lost without Helen Mar’s account of meeting her in Winter Quarters.

Additionally, Helen Mar jumps from the past to the present from time to time, giving the reader details about the events of her day (1880s) when she published these reminiscences of an earlier time.

In this particular series of recollections, Helen Mar not only recounts the experiences of her immediate family, including her father and mother (Heber Chase Kimball and Vilate Murray Kimball), but also paints a panoramic picture of life among the early Saints in Kirtland, Ohio; Far West, Missouri; Nauvoo, Illinois; and Winter Quarters, now Nebraska. Additionally, Helen Mar describes her trek across Iowa—a long and difficult journey for the refugees from Illinois—in 1846. Her recollections capture familiar themes of Mormon history found in other autobiographies and reminiscences. In this way, Helen Mar forges a backward link to the Mormon collective remembered past.

It is perhaps understandable that only a few diaries and reminiscences from the vast collection of LDS life stories have received close attention and that those few consist mainly of narratives written by men. Recently, however, historians have been directing more attention and effort to women’s material. Even the importance of Helen Mar’s recollections as published in the Woman’s Exponent has not gone entirely unnoticed by scholars. Andrew F. Ehat (1981) employed Helen Mar’s reminiscences in his BYU master’s thesis detailing the introduction of temple ordinances by Joseph Smith. [31] Stanley

B. Kimball (1981) used extensive citations from the series in his biography of Heber C. Kimball. [32] Leonard J. Arrington (1985) cited this source in his biography of Brigham Young. [33] Jill Mulvay Derr, Janath Russell Cannon, and Maureen Ursenbach Beecher (1992) found several nuggets from this source for their history of the Relief Society. [34] The most extensive use of these reminiscences to date is Todd Compton’s forthcoming effort to reconstruct the life stories of Joseph Smith’s wives, including Helen Mar. [35]

Organization of the Reminiscences

Helen Mar’s published reminiscences were divided into several sections when first published in the Woman’s Exponent: “Early Reminiscences,” “Life Incidents,” “Retrospection,” “Scenes in Nauvoo,” “Scenes and Incidents in Nauvoo,” “Scenes in Nauvoo after the Martyrdom of the Prophet and Patriarch,” “Scenes in Nauvoo, and Incidents from H. C. Kimball’s Journal,” “The Last Chapter of Scenes in Nauvoo,” “Our Travels Beyond the Mississippi,” and “Scenes and Incidents at Winter Quarters.” We present them here in the order in which they were originally published.

Helen Mar Whitney’s Sources

Helen Mar’s reminiscences of the history of the Church utilize not only her own memory of the events she personally experienced but also the diaries and letters of her father, mother, and husband. [36] One of the unintended consequences of collecting and editing Heber C. Kimball’s papers for inclusion in these articles was a separate publication of her father’s diaries, letters, and autobiography in 1882, which Helen Mar provided to the publisher. [37] Obviously, many of the extracts from Elder Kimball’s diaries and letters are more meaningful when read in conjunction with Helen Mar’s comments preserved in these recollections, especially when the excerpt is either directed to Helen Mar, as in the case of letters addressed to her by her father, or when the diary entry relates to her immediate family or to her personal experience. Although many of the individual sections share resource material, some articles within the sections and some sections themselves contain more of Helen Mar’s own words than others. Much of the material comes from sources Beyond her memory, but these selections reflect what she felt was important. Helen Mar made the selection, and therefore those items, even when written by another individual, reflect her perspective.

Helen Mar recognized the problem of the passing of time since the events described in these recollections. She notes insightfully: “I often find it a very difficult one to gather up the many broken threads of the almost forgotten past, and weave them into a shape for the perusal of others, and it is a pleasant relief, like a cooling draught to the thirsty traveler, to find here and there a scrap of our history interwoven with that of others, bringing before us objects and scenes which were once familiar, but had become dim and nearly effaced from our memory by the hand of time, which has been to me unsparing in its ravages.” [38]

In this sense, reminiscences are different from diaries and letters in that they give the writer’s life from a later perspective, filtered through the passage of time. Certainly, Helen Mar distinguished between the public nature of these recollections and the private nature of the diaries she began to keep in the 1880s. While she argued that chronological distance sometimes blurred the edges of past scenes, she realized that her use of primary sources, such as Heber C. Kimball’s diary and Vilate Kimball’s letters, helped recover much of the past and brought into sharp focus those areas that had become dim over time. In a real sense, the sources she chose acted as a springboard to awaken her memory of the past.

Like other sister-Saints writing their personal life stories during the latter half of the nineteenth century, Helen Mar describes in vivid detail those singular events of a woman’s life: courtship, marriage, birth of children, and the death of family members or personal friends. Her story, like that of many other Latter-day Saints, is irradiated with a deep sense of faith in her religion. Autobiographical writings almost always develop recurring themes and patterns. [39] Daniel Shea explains: “The entries of a diary may possess considerable homogeneity and may even accumulate into a number of discernible ‘themes.’ Nevertheless, autobiography represents a further stage in the refinement of immediate experience, a stage at which the writer himself has attempted to introduce pattern and moves consciously toward generalization about his life. The very circumstances of composition determine that the autobiographer shall consider the possibility of a relation between personal events widely separated in time, whereas the diary keeper is almost invariably a prisoner of the present.” [40]

Helen Mar’s themes include the hardships and persecutions of the early Mormon experience demonstrating the conflict between “good and evil,” thus reinforcing younger Mormons in their religion and culture. Another theme is the defense of plural marriage, which was increasingly becoming the center of the national political agenda. Finally, she presents her father as one of Mormonism’s greatest heros, which is both a family history theme and a Mormon community theme. Like other spiritual autobiographies, this series, of articles demonstrates the patient work of compiling, organizing, and narrating the life story of a woman who lived in an extraordinary time.

Woman’s Exponent

One of the most impressive achievements of Latter-day Saint women in the late nineteenth century was the publication of the Woman’s Exponent in Salt Lake City. [41] Although it was not an official publication of the Church, it served as the major voice of women between 1872 and 1914 throughout the Latter-day Saint colonizing region in western North America. Among the many types of items published in the paper, personal reminiscences of witnesses and participants in the story of the early history of the Church played a significant role.

One may ask why Emmeline B. Wells, the editor at the time, was so committed to Helen Mar’s ongoing series. Emmeline had been a plural wife of Newel K. Whitney (married in 1845); so she was Helen Mar’s half mother-in-law. Emmeline definitely was a Whitney, as she had two children with Newel before he died in 1850. Later, she married Daniel H. Wells in 1852. Apparently, she was a doting “aunt” to Helen Mar’s children, especially Helen Mar’s son, Orson F. Whitney.

Emmeline also published several other women’s autobiographies and reminiscences in the Woman’s Exponent, including those from members of the Whitney family.

Her last tribute, Helen Mar’s obituary (see Appendix Two), confirms Emmeline’s close association with her.

Context of the Reminiscences

Autobiographical works were rare in antiquity before the Roman and Christian eras, beginning about A.D. 100. [42] Not until Roman times is there an example of a woman’s autobiographical work. Until the mid-seventeenth century, only about 10 percent of the total number of published autobiographies were written by women. The nineteenth century ushered in a plethora of autobiographies—the result of the revolution in printing, increased economic stability, and, especially for women, advancements in education. Apparently, the public was eager to read about everyone—not just the famous.

During the late nineteenth century, women’s works included the usual diaries, letters, journals, captivity narratives, and spiritual autobiographies. [43] Quakers and Puritans wrote most of the religious autobiographies published in the United States during that period. Although some of these efforts were published before the death of the authors, most were not. By the second half of the nineteenth century, many Latter-day Saints took the time to tell their own stories through journals, diaries, and autobiographical works. [44] Among the thousands of LDS life-story records, relatively few are by women.

For many of the committed Saints, some of their words went to print as living witnesses of the Restoration and of their own sacrifices in following the Church through its movements and difficulties before their deaths. [45] There are also, of course, autobiographies from angry ex-Mormons such as Fanny Stenhouse. [46]

One of the early attempts to record the life stories of Latter-day Saint women is Eliza R. Snow and Edward W. Tullidge’s 552-page compilation, The Women of Mormondom, published in New York in 1877. [47] Containing the accounts of some forty women, the book is an important contribution to the preservation of LDS women’s experiences during the founding years of the Church.

Another opportunity to publish a positive view of the Saints came in 1880 when non-Mormon Hubert Howe Bancroft began collecting information for a multivolume history project on the western territories. [48] Enlisting the cooperation of LDS Church leaders, Bancroft began collecting material on Utah—including life stories of Latter-day Saint women. [49]

During the same year, the Church’s jubilee anniversary, Helen Mar began publishing her important series on early Church history, which contained her own reminiscences. [50] While Helen Mar published a history of the early Church from her own perspective in the Woman’s Exponent, several other women joined with her in 1884 to tell the story of Latter-day Saint women in Augusta Joyce Crocheron’s Representative Women of Deseret. [51]

Of course, since then, other labors provide the modern reader with vivid descriptions of everyday life for nineteenth-century Latter-day Saint women. Exemplary of such efforts to collect and publish Latter-day Saint women’s life writings is Carol Cornwall Madsen’s In Their Own Words: Women and the Story of Nauvoo. [52] Not only does Madsen provide excerpts from the personal writings of some twenty-five sister-Saints but she also gives important context to the types of material utilized in her well-crafted book. Her efforts, along with other recent works, provide a fresh perspective from which to view such vital but often-neglected aspects of Church history as work, family life, childbirth, child rearing, education, entertainment, health, disease, and death. [53]

Limitations of the Reminiscences

Whether chronicling the broader events of Church history (based on years of thought and reflection) or the intimate family experience within the larger historical context, Helen Mar recreated her life as she wanted the public, including her own children, to remember it. As Maureen Ursenbach Beecher notes: “It would seem that in life writings truth is a matter of purpose and point of view.” [54] Carol Cornwall Madsen adds: “Understandably, these women [Latter-day Saints of the period] were selective in what they recorded, and the reader (and the historian) must always recognize the historical limitations of personal discourse.” [55]

It is true that Helen Mar, like others who wrote of their experiences, was selective in what she recalled and in particular what she chose to include as additional documentary sources. Yet these serialized accounts published more than one hundred years ago allow one to hear the voice of a woman as an individual experiencing life with all its twists and turns. Helen Mar responds in different ways to the institutional history of the Church and to personal experiences. The shape and content of her recollections are, therefore, as varied as the lives of the individuals mentioned in these recollections. But with all the individuality of her story and the unique characteristics of her reminiscences, Helen Mar shared much with other women who gathered with the Saints during the 1830s and 1840s. Additionally, there is a common purpose at the heart of the process of these nineteenth-century Latter-day Saint women’s efforts to record their life stories and a shared commitment to the Restoration, as well as a need to record their testimonies of it.

Whatever one finds in such personal recollections, they often provide a window to the past that not only allows us to imagine a time and place that has been lost but also provides an opportunity to hear the “personal voice” of some truly interesting human beings who lived in a world utterly unlike that of today, in many ways. Additionally, reading about a woman’s life, her family’s lives, and her community’s life often connects the modern reader intimately with other lives and stories—in this case with a woman’s life. To fully appreciate her story, one must identify with a different perspective—Helen Mar’s perspective. As one reads these recollections, one shares the writer’s experience of the turning points and inevitable personal victories and losses by which one characteristically measures a life. When Helen Mar describes her feelings of loss when her child died at Winter Quarters, readers can relate to the experience because they feel the same type of sorrow when friends and family die unexpectedly, or even after long illness.

Preparation of the Reminiscences for Publication

Helen Mar’s effort to compile her history in the 1880s was not the first time she attempted to recount part of that life story. She notes in an unpublished autobiography, apparently written during the first nine days in January 1876:

My life has been truly an eventful one like many others in the “Mormon” Church, and at the solicitation of a few of my Sisters I have undertaken the task of writing a little sketch of my life for the benefit of the young and inexperienced more especially my own children who may read and proffit by it when I am gone. . . .

My Father when on his last mission East wrote me a letter and in it requested me to write my history in one of his large Books & when his own was written said that mine should go in with it. but I never felt inclined to untill the year 1876, in the 47th year of my age Being very feeble, so much so that I was confined to my room through winter. . . . The Dr could not cure me, so I’d no other source to look to but my Father in Heaven so concluded to send for Sister [Eliza R.] Snow who came soon bringing Sister [Margaret Thompson] Smoot. They washed & anointed me & I was greatly comforted. We talked about many things—among the rest I told some of my experience. Sister Smoot told me she thought I would be a great benefit to the young sisters to hear my history & she considered it my duty to tell them. She had told me the same when I was at her house in Provo, and that night I made up my mind to commence my byography as it would serve two purposes, my mind would be occupied & this last reason stimulated me more than any other to undertake it. I was up stairs in a peaceful pleasent room where I had nothing to disturb my thoughts & after I commenced writing I gained in strength.—I became so absorbed in the past that I lost sight of the present, & almost fancied that I was young and living my life over again. Some portions of which brought sweetest joy, & others never failed to bring tears to my eyes. I realy felt that I was blessed in doing this & never again was I lonesome while occupied in that way. [56]

Like many others, Helen Mar moved from the informal transmission of her life story to the formal when Margaret Smoot visited her and said that she “thought it would be a great benefit to the young sisters to hear” her story. Apparently, until that time, Helen Mar had attempted to share her experiences only informally. Now, at age 47, she finally decided that the time had come to record her life story so that when her voice became silent, the memories of her early life would not be forgotten.

She adds a poem to the entry regarding her efforts, thoughts, and feelings as she recreates her life story in January 1876:

While mem’ry helps me to retrace

My steps through every nook and place

Endeard by love and grief and pain

All linked together forms a chain.

Of interesting scenes to me—

Some were bitter, it is true;

But, had I power one link to sever

My trusting heart would say no never.

For faith and hope look far away

Where all is joy in endless day,

And bids me hold out to the end

And never weary but defend

The principles of righteousness

Which brings to me true happiness— [57]

This autobiographical sketch apparently is the basis of Helen Mar’s first articles published in the Woman’s Exponent in 1880. An incomplete manuscript collection numbering some thirteen leaves in possession of a member of the Whitney family suggests that Helen Mar may have, on occasion, written at least one draft before submitting a final version to the Woman’s Exponent. Additionally, these manuscripts suggest Helen Mar intended to continue her story Beyond Winter Quarters, since she detailed the journey to Salt Lake City in 1848. [58] However, Helen Mar notes in her last article published in the Exponent that “the increase of care and responsibilities thrown upon me through the death of my husband, with various duties which require my attention, I must resign this one at least at the present, as I find it difficult to devote the amount of time and thought which it requires and attend to the tasks incumbent upon me.” [59] Her labors to capture the past in word pictures (reminiscences), her autobiographical sketches (1876 and 1881), and her later day-to-day accounts (diaries) make Helen Mar one the best-documented nineteenth-century women in LDS Church history, or even in nineteenth-century western American history.

Helen Mar’s diaries (which she began to keep in 1884) reveal, to some extent, the often-difficult effort to prepare material for publication. In 1885, for example, she notes:

Thursday [February] 12th.—This day spent copying from Horace’s journal at “Winter Quarters”—my arm & shoulder painful, from writing—caused by the great amount of writing previously done from time to time with pencil, etc. Have had to give up & lay down awhile, last evening, & this—being completely used up—Am so anxious to accomplish what I have on my mind to do, before I pass over to “the other side”. [60]

A few months later, Helen Mar records her feelings about the research she was doing for the articles:

Thursday [June] 18th. Felt unwell this morning—I sewed hard half the day—then, for a change, went to work sorting papers & letters in Horaces [?] secretary drawers—Many forgotten scenes & incidents have been recalled by the notes & letters, which I found, that were written years ago by him, and his old friends—connections, and chums, of the long ago. [61]

She adds on the following day:

Friday [June] 19th. Charley goes every day to work on the road—taking his dinner—finished looking over Horace’s papers—have had an interesting time—all to myself—and have had peculiar feelings—found letters from our brother’s—Wm.& Charley Kimball. Orson & Joshua Whitney. 2 from my father to H. some from mother to me, & m a n y others, which I read over till my eyes were tired out. In the midst of it, received callers— [62]

In October 1885, Helen Mar notes the struggle to find a few moments during a busy day to prepare one of her articles for the Woman’s Exponent: “I, after a hard trying, have written another historical article for Ex.—thought I should not be able to, for the constant interruptions.” [63]

In February 1886, she reveals at least one time to begin and finish an installment for her series on early Church history for the Woman’s Exponent: “I commenced another historical article for the Ex. today.” [64] A few days later, she records: “I finished my copy and took it to Ex. Off—found no one there—left it with George Lambert to give Em in the morning.” [65] “Em” is Emmeline B. Wells, editor of the Woman’s Exponent. After only a few days, Helen Mar notes: “Commenced a historical article for the next Exponent.” [66] A comparison of Helen Mar’s holographic material (diaries and letters) with the published reminiscences demonstrates careful editing and polishing of the Woman’s Exponent articles, standardizing and formalizing spelling and grammar. In all likelihood, Emmeline B. Wells is the unseen hand responsible for that editing.

After all the struggles and efforts to produce the series, Helen Mar was apparently happy with the end product. In one particular entry, she notes with some satisfaction a praise she received regarding her efforts: “One of Bro. Home’s sons—Bishop of one of the towns south—introduced himself to me—said he had not met me before, but had enjoyed reading my writings in the Exponent, etc. I thanked him, feeling to appreciate the compliment.” [67]

The Rest of Her Story

Helen Mar notes in her earliest written autobiography: “I never wrote or kept a Diary one day in my life.” [68] Later, beginning in 1884, she started keeping a diary, revealing details about the last decade of her life (the diaries continue until just a month before her death in November 1896). Her diaries are located in two separate repositories in Utah. One set is found in the Helen Mar Whitney Collection, Merrill Library, Utah State University, Logan, Utah. The smaller diary collection is found in Helen Mar Kimball Whitney Papers, Church Archives, Historical Department, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah. [69] These diaries reveal another layer of Helen Mar’s life. The contrast between the diaries and the autobiographies and recollections published in the Woman’s Exponent is often dramatic. Far different from the reasoned and often carefully crafted autobiography and recollection, the diary entries reveal a day-to-day patchwork of life following several tragic events—deaths of family members, including her husband and son; concerns for economic security; and personal health problems.

Additionally, as already noted, Helen Mar published two important booklets, Plural Marriage as Taught by the Prophet Joseph Smith and Why We Practice Plural Marriage, as well as several letters and poems in the Woman’s Exponent that give additional information about her life and times. Taken together, these sources, both published and unpublished, allow the modern reader to come to know Helen Mar.

Conclusion

A few days following the publication of Helen Mar’s obituary in local Salt Lake City newspapers in November 1896, the Deseret Evening News reported: “In the Eighteenth ward chapel Wednesday afternoon, the funeral services of Sister Helen Mar Whitney were held. The speakers were Elders Heber J. Grant, John Henry Smith, President Joseph F. Smith and Elders Joseph Kingsbury and Angus M. Cannon. The remarks of President Smith especially produced a powerful impression. Fitting music was rendered by the Eighteenth ward choir, and a beautiful solo, ‘The Bright Beyond,’ which had been requested by Mrs. Whitney, was sung by Miss Edmonds. A long line of carriages followed the remains to the grave.” [70]

A distinguished group of participants honored a Latter-day Saint woman who took the time, stealing a few moments in a busy life filled with family obligations and the hard work of washing clothes, preparing meals, cleaning house, and taking care of the sick, to leave her posterity and the modern reader important documents including diaries, autobiographies, and reminiscences to help recover her life story. She might have chosen to express her life summation in other ways. Helen Mar felt a sense of profound responsibility to her immediate family and descendants and to her wider “family,” the LDS community, that caused her to write her life history. Her reminiscences celebrate her sacrifices for the Church she dearly loved and for the gospel that imbued her world view. Finally, Helen Mar’s reminiscences, like the life writings of many other women, provide “a woman’s view” of early Church history—something that reveals another level of historical understanding—a nontraditional source of study and appreciation.

Notes

[1] Mel Bashore, as a result of a suggestion by Ron Esplin, collected copies of the Woman’s Exponent containing Helen Mar Whitney’s reminiscences in 1975; see “Writings of Helen Mar Whitney in the Woman’s Exponent” located in the LDS Church Library, Historical Department, Salt Lake City, Utah. Excerpts from the years 1880–83 appear on Infobases’ CD, LDS Collectors Library, 1995 edition. Apparently this represents less than one-third of the original content of the series. Additionally, Bashore compiled an index to Helen Mar’s Woman’s Exponent writings in 1975; see “Index to the Writings of Helen Mar Whitney in the Woman’s Exponent,’” also found in the LDS Church Library, Historical Department, 1975.

[2] Woman’s Exponent 8 (15 May 1880): 188.

[3] Woman’s Exponent 8 (15 May 1880): 188.

[4] Woman’s Exponent 9 (15 June 1880): 10.

[5] Woman’s Exponent 9 (1 July 1880): 18.

[6] For example, see Ronald W. Walker, “The Stenhouses and the Making of a Mormon Image,” Journal of Mormon History 1 (1974): 51–72.

[7] See, for example, Woman’s Exponent 11 (1 June 1882): 1–2.

[8] This disrupted their lives when their husbands and fathers were imprisoned or forced onto the underground, driving many of them into hiding from federal officials and taking away their rights to vote and to hold office in Utah Territory; see Thomas G. Alexander, Utah: The Right Place, The Official Centennial History (Salt Lake City: Gibbs-Smith Publishers, 1995), 186–201.

[9] Woman’s Exponent 18(1 October 1880): 70.

[10] Helen Mar Whitney, Plural Marriage as Taught by The Prophet Joseph: A Reply to Joseph Smith, Editor of the Lamoni (Iowa) “Herald” (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor, 1882), 38–39.

[11] Helen Mar Whitney, Plural Marriage as Taught by The Prophet Joseph: A Reply to Joseph Smith, Editor of the Lamoni (Iowa) “Herald” (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor, 1882), 1.

[12] Woman’s Exponent 11 (1 August 1882): 39.

[13] Woman’s Exponent 11 (1 August 1882): 39.

[14] Woman’s Exponent 11 (1 August 1882): 39.

[15] Woman’s Exponent 11 (1 March 1883): 146.

[16] Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Jeni Broberg Holzapfel, Women of Nauvoo (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1992), 86–103.

[17] Todd Compton, In Sacred Loneliness: The Plural Wives of Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, forthcoming).

[18] Woman’s Exponent 12 (1 November 1883): 81.

[19] See Appendix One: “Helen Mar Kimball Whitney 1881 Autobiography Written to Her Children”; original found in the Archives Division, Church Historical Department, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah, hereafter cited as LDSCA.

[20] Plural Marriage as Taught by the Prophet Joseph (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor, 1882) and Why We Practice Plural Marriage (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor, 1884). See the “Introductory” section in Plural Marriage as Taught by the Prophet Joseph for the relationship between her Woman’s Exponent articles and this pamphlet.

[21] Andrew Jenson, Historical Record 6 (May 1887): 234.

[22] Orson F. Whitney, Life of Heber C. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Kimball Family, 1888), 339; (328, 1945 ed.).

[23] Catherine Lewis, Narrative of Some of the Proceedings of the Mormons; Giving an Account of their Iniquities . . . (Lynn, Massachusetts: the Author, 1848), 19 and Wilhelm Wyl, Mormon Portraits: Joseph Smith, the Prophet: His Family and Friends (Salt Lake City: Tribune Press & Publishers, 1886).

[24] She wrote a long letter revealing her feelings about her own experience reading the minutes of the conference when the Manifesto was approved by the congregation in October 1890: “I did so with a prayerful heart and desire for the right spirit and understanding to judge of its true source. And the testimony, and spirit that came to me was strong enough to convince me that this step was right,” Woman’s Exponent 19 (15 November 1890): 81.

[25] Woman’s Exponent 12 (1 December 1883): 102.

[26] Woman’s Exponent 12 (1 November 1883): 81.

[27] Woman’s Exponent 12 (1 January 1884): 117.

[28] Woman’s Exponent 12 (1 December 1883): 102.

[29] Woman’s Exponent 12 (1 December 1883): 102.

[30] Woman’s Exponent 12 (15 April 1884): 170.

[31] Andrew F. Ehat, “Joseph Smith’s Introduction of Temple Ordinances and the 1844 Mormon Succession Question” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1981); additionally, David John Buerger published material from Helen Mar Whitney’s recollection in The Mysteries of Godliness: A History of Mormon Temple Worship (San Francisco: Smith Research Associates, 1994).

[32] Stanley B. Kimball, Heber C. Kimball: Mormon Patriarch and Pioneer (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1981).

[33] Leonard J. Arlington, Brigham: Young American Moses (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985).

[34] Jill Mulvay Derr, Janath Russell Cannon, and Maureen Ursenbach Beecher, Women of Covenant: The Story of Relief Society (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992).

[35] Compton, In Sacred Loneliness.

[36] Heber C. Kimball’s diaries covering the period, with breaks, from 4 June 1837 through 38 October 1847 and Horace Kimball Whitney’s diaries covering the period with breaks from 15 February through October 1847 are found in the LDSCA. Many of the letters of Heber and Vilate Kimball used by Helen Mar Whitney are also found in the LDSCA.

[37] President Heber C. Kimball’s Journal Designed for the Instruction and Encouragement of Young Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor, 1882); see the introductory material for information regarding Helen Mar Whitney’s contribution to the project.

[38] Woman’s Exponent 10 (15 December 1881): 106.

[39] See Marlene A. Schiwy, A Voice of Her Own: Women and the Journal-Writing Journey (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 243–44.

[40] Shea, Spiritual Autobiography, x.

[41] See Sherilyn Cox Bennion, “The Woman’s Exponent: Forty- Two Years of Speaking for Women,” Utah Historical Quarterly 44 (Summer 1976): 222–39 and Equal to the Occasion: Women Editors of the Nineteenth-Century West (Reno, Nevada: University of Nevada Press, 1990); see also Carol Cornwall Madsen, “Voices in Print: The Woman’s Exponent, 1872–1914,” in Women Steadfast in Christ, ed. Dawn Hall Anderson and Marie Cornwall (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 69–80.

[42] See Estelle C. Jelinek, The Tradition of Women’s Autobiography: From Antiquity to the Present (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1986).

[43] See Daniel B. Shea Jr., Spiritual Autobiography in Early America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968).

[44] Davis Bitton lists close to three thousand autobiographies and diaries; see Davis Bitton, Guide to Mormon Diaries & Autobiographies (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1977).

[45] Maureen Ursenbach Beecher suggests that the ratio of women’s material to men’s material in Davis Bitton’s Guide to Mormon Diaries & Autobiographies is one to ten; The Personal Writings of Eliza Roxcy Snow, ed. Maureen Ursenbach Beecher (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1995), xv.

[46] Fanny Stenhouse, Tell it All (Hartford, Conneticut: A. D. Worthington and Co., 1874).

[47] Edward Tullidge, Women of Mormondom (New York: Tul-lidge & Crandall, 1877).

[48] Between 1874 and 1890, Bancroft published thirty-nine historical works dealing with the West, including the history of Utah; Hubert Howe Bancroft, History of Utah (San Francisco: The History Company, 1889).

[49] Apparently, Franklin D. Richards received the assignment to coordinate efforts to help Bancroft. He enlisted his wife, Jane Snyder Richards, to help collect the stories of Latter-day Saint women; see Beecher, Personal Writings of Eliza Roxcy Snow, 4.

[50] She was not the only Latter-day Saint woman to agree to write her life story in 1880 as a “memorial” to the jubilee anniversary of the Church; see, for example, Mary Jane Mount Tanner, “Autobiography” (1837–80), photocopy of typescript; and Mercy Fielding Thompson, Mercy Thompson Papers, Daughters of the Utah Pioneers Collection, LDSCA. Carol Cornwall Madsen indicates that several women, including Mary Jane Mount Tanner and Mercy Fielding Thompson, designated that their stories be “read at the one-hundredth anniversary of the Church” in 1930 by their oldest female descendant; see Carol Cornwall Madsen, In Their Own Words: Women and the Story of Nauvoo (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1994), xi.

[51] Augusta Joyce Crocheron, Representative Women of Deseret (Salt Lake City: J. C. Graham, 1884); Helen Mar Whitney’s life story is covered in pages 109–17. A brief summary and historical setting of this work is found in Judith Rasmussen Dushku and Patricia Rasmussen Eaton-Gadsby, “Augusta Joyce Crocheron: A Representative Woman,” Sister Saints, ed. Vicky Burgess-Olson (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1978), 487–92.

[52] Madsen, In Their Own Words.

[53] Along with the efforts of Carol Cornwall Madsen and Maureen Ursenbach Beecher cited above are Kenneth W. Godfrey, Audrey M. Godfrey, and Jill Mulvay Derr, Women’s Voices: An Untold History of Latter-day Saints, 1830–1900 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1982); Holzapfel and Holzapfel, Women of Nauvoo; and Maurine Carr Ward, Winter Quarters, The 1846–1848 Life Writings of Mary Haskin Parker Richards (Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1996).

[54] Beecher, Personal Writings of Eliza Roxcy Snow, xviii.

[55] Madsen, In Their Own Words, x.

[56] Helen Mar Whitney Papers, “Reminiscences and Diary 1876 and November 1884-September 1885,” 9 January 1876, LDSCA.

[57] Helen Mar Whitney Papers, “Reminiscences and Diary 1876 and November 1884-September 1885,” 9 January 1876, LDSCA.

[58] Original manuscript material in possession of Lester and Shauna Smoot Essig, Centerville, Utah; copies in possession of the authors.

[59] Woman’s Exponent (15 August 1886): 47.

[60] Helen Mar Whitney Diary, 12 February 1885, LDSCA.

[61] Helen Mar Whitney Diary, 18 June 1885.

[62] Helen Mar Whitney Diary, 19 June 1885.

[63] Helen Mar Whitney Diary, 15 October 1885.

[64] Helen Mar Whitney Diary, 3 February 1886.

[65] Helen Mar Whitney Diary, 11 February 1886.

[66] Helen Mar Whitney Diary, 13 February 1886.

[67] Helen Mar Whitney Diary, 9 May 1888. Helen Mar Whitney was likely referring to Joseph Smith Home, bishop of the Richfield Second Ward, Sevier Stake.

[68] Whitney, “Autobiography,” 9 January 1876.

[69] Todd Compton and Chuck Hatch are preparing these diaries for publication as part of a Utah State University Press series, “Life Writings of Frontier Women.”

[70] Deseret Evening News, 19 November 1896.