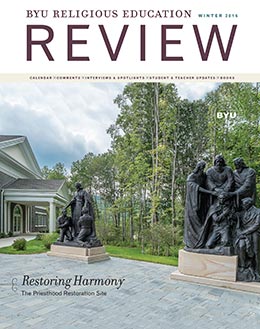

The Priesthood Restoration Site

Mark L. Staker

Mark L. Staker served as lead curator in the Church History Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when this was published, and has been involved in historic sites restoration for more than fifteen years. He holds a PhD from the University of Florida in cultural anthropology.

On September 19, 2015, Elder Russell M. Nelson, President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, dedicated the Priesthood Restoration Site in Oakland, Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania. During the dedicatory prayer, Elder Nelson entreated on behalf of the site, “I dedicate it as a place of faith, a place of prayer, a place of learning, a place of glory, indeed, a place of holiness. . . . I dedicate these buildings, grounds, and groves, all to the end that faith in Thee will increase and that families may be strengthened and qualify for exaltation according to Thy great plan of happiness.”[1] To accomplish these purposes, the renovation of the Priesthood Restoration Site under direction of Church leadership was a joint effort of the Church History Department, Missionary Department, and Special Projects Department, with many others contributing toward the effort, including staff and students at BYU.

BYU connections developed early in the process. The Church History Department’s historic sites program hired a team of bright students from BYU as interns several years before the project was publically announced. These students helped review published material, search the Church Archives collection, and think about the significance of the historical events connected with Church history in Pennsylvania. Once each week, a scholar, including many BYU faculty members, came to the Church History Museum to share his or her perspective on significant historical events related to the site, which helped in pondering the big events. These scholars included Larry Porter, Jack Welch, Royal Skousen, Carol Madsen, and Craig Manscill.

As the Historic Sites group (now the Historic Sites Division) searched the collections of the Church Archives, we learned extensive details about Wilford C. Wood’s acquisition of sections of the Joseph Smith and Isaac Hale farms from 1939 to 1946, and about additional land purchases over the ensuing years, culminating in the dedication of the Aaronic Priesthood Monument by Presiding Bishop Joseph L. Wirthlin on June 18, 1960. We also amassed a large amount of information that helped shed light in subsequent years on significant details of the story during the 1820s (when the site was still known as Harmony, Pennsylvania) which would help us better share a more accurate account of events at the new Priesthood Restoration site. The Church History Department commissioned Hartgen Archeological Associates Inc. in 2004 to do initial archeology at the Joseph and Emma Smith homesite, and hired them from 2011 to 2012 and in 2014 to do additional work at the Joseph and Emma Smith home and the Isaac and Elizabeth Hale farm. I was privileged to travel to many archives, libraries, and other repositories of historical materials connected to Susquehanna County to search for additional source material that could shed light on the Hale family, their property, and Joseph Smith’s history in Harmony.

Through careful review of the archeological work and documentary sources, the history of the sites began to yield itself. Land records, tax records, correspondence from neighbors and other documents suggested important details about both the Hale home and the Smith home which, when combined with information from the archeology investigation, suggested we could reconstruct both homes with the confidence that significant details would be correct. While we knew the large picture for the Hale home, for Joseph and Emma’s home we could reconstruct with confidence small details such as the style of their rain gutter, the style of their baseboards, and even the species of wood used for their floor. We could do this through relying on numerous photographs, letters from individuals who lived in the home and described its details, and even a small model of the home built in the late 1950s by an elderly resident who had been inside numerous time before it burned down June 23, 1919.

In order to accurately replicate furnishings in the homes, we turned to the archeological remains that were recovered, Isaac Hale’s probate records, and Lucy Mack Smith’s account of her visit in Joseph and Emma’s home, which mentioned various items in the home. We supplemented these specific details with general information about the possessions of many of their neighbors and the typical furnishings found the homes of the Susquehanna Valley, taking into account the owners’ birthplace, education, and economic situation. The capable staff at Old Sturbridge Village also allowed careful study of their vast collection of period artifacts. Several Church-service missionaries and volunteers with skills in early American furniture construction, tinsmithing, textile production, and numerous other site furnishings replicated pieces found in museums, local historical societies, and private collections. Their talents were supplemented by work from nationally renowned artisans. Steve Larson, who made wallpaper for the renovation of the White House Lincoln bedroom, replicated 1820s wallpaper for Isaac and Elizabeth Hale’s home. Joel Pardis, who made the lamps for Thomas Jefferson’s restored Monticello, found time during that project to repair a lamp for the Hale home. And Ron Raiselis, who made the coopered items for Jefferson’s Monticello and the Smithsonian’s American History Museum, and the large lye vats for the reconstructed Kirtland ashery, made a number of items in his New Hampshire workshop for use in the Harmony homes.

Even the landscape received attention to bring it in line with the historic record. Doctrine and Covenants 24:3 indicates Joseph Smith planted a field in July 1830. A study of soil in the area, entries in local farmers’ garden journals for July, and Joseph’s September departure from the valley indicated he likely planted buckwheat which ripened the week he left. A grass suggestive of buckwheat now grows in Joseph’s field, delineating its boundaries as defined by aerial photography. Some of Emma’s favorite flowers were used in landscaping. Numerous documents and a careful look at soil and water levels, suggested the “woods” where Joseph and Oliver went to pray when John the Baptist appeared and restored the Aaronic Priesthood grew at the north end of Joseph’s property rather than in the soggy ground by the Susquehanna River. Bob Parrott, the caretaker of the Sacred Grove in Manchester, New York, carefully examined the flora of Joseph’s property and delineated walking paths that would take visitors through the wooded areas on the mountain foothills, and help foster healthy growth in the sugar maple groves on the north end of Joseph’s property. Much of the data that helped us understand the nature of the Susquehanna River and the landscape of the area on May 15, 1829, was shared with the faculty of BYU’s Church History and Doctrine Department and reviewed by Church leadership before moving to restore the wooded landscape on the north end of the Joseph and Emma Smith farm.

The setting of the Book of Mormon translation area received particular attention to get the details correct. Steve and Ben Pratt of Cove Fort, Utah, carefully replicated the golden plates, relying on eyewitness descriptions and a sketch of the rings provided by David Whitmer. The young men and women of several stakes used images of Book of Mormon characters from several pre-1844 sources and followed detailed instructions to replicate the characters on specially prepared copper and gold alloy plates. An employee of the Church History Department, LaJean Carruth, volunteered her time to hand-weave the m’s-and-o’s patterned tablecloth that replicated Emma’s tablecloth Joseph used to wrap the plates. The hat that sits on the table in the reconstructed kitchen is made of beaver pelt with a hand-stitched hatband, which fits eyewitness accounts of the hat Joseph used in translation. Royal Skousen’s careful study of the original manuscript suggested Oliver wrote it using quill pens, and surviving 1820s pens in the Old Sturbridge Village collection became models to replicate the ones Oliver used. Even the original 1790s “make-do” water pitcher on the translation table, with its tin handle replacing the original that broke two centuries ago, replicates something Joseph and Oliver may have used in their poverty to keep their mouths wet as they repeated the words of the translation back and forth, hour after hour.

When President Nelson dedicated the furnishings of the site in his prayer and dedicated “the groves of trees—those sacred woods—where, under the direction of Peter, James, and John, the Aaronic Priesthood was restored by John the Baptist,” he made holy the efforts of many people who had worked hard to understand and replicate the setting where significant events of Church history took place. Elder Nelson recognized these efforts as he expressed prayerful gratitude, saying: “We thank Thee for the skills and artistry of craftsmen and women who actually did the work. Wilt Thou bless them and their families for their efforts.”[2]

Notes

[1] “Transcript: President Russell M. Nelson Remarks and Dedicatory Prayer at Priesthood Restoration Site,” Mormon Newsroom, http://

[2] “Transcript: President Russell M. Nelson Remarks.”