Kent P. Jackson (kent_jackson@byu.edu) was a professor of ancient scripture at BYU when this was published.

Keith Hansen Meservy was born December 4, 1924, in Provo, Utah. From his parents, Edward and Lucille Meservy, he learned the gospel of Jesus Christ and nurtured an innate desire to love God with all his heart and to love his neighbor as himself. His love for God and his fellow mortals set the course of his life and directed the choices he would make. It was in recognition of how much he had been blessed, and with a desire to share his blessings with others, that he set out on a lifelong path of service.

Keith was reared in Provo, went to school in Provo, found his wife in Provo, and made his career in Provo. To some, that may sound like a straight trajectory, but, in fact, Keith Meservy was not known to walk in straight lines. He preferred to travel off the beaten path.

After his graduation from high school, Keith was drafted into the United States Army. He fought in the Pacific in World War II, was wounded in combat, and received a Purple Heart. Like many veterans of that war, he did not talk much about his experiences in it, but he certainly learned from them. When he returned home, Keith was called to serve in the Northern States Mission. He wrote later that while he was there, he “learned the meaning of love: love for people, love for the gospel, love for the scriptures, and love for the opportunity to teach.[1] Of the love he gained for the scriptures on his mission, Keith said, “We four missionaries decided on a Sunday that we would like to start reading the New Testament. That week became one of the marvels of my life. I don’t know how to describe the feelings I had as I read the New Testament.”[2] Keith added: “I was fascinated by what I read. I wasn’t just reading a story. I was reading about Jesus. I couldn’t get enough of it. My heart burned within me as my knowledge of Jesus and his ministry opened up to my mind and spirit. I had never experienced such strong feelings as I did when I studied the Gospels at that time.”[3]

In 1951, Keith married Arlene Bean. The couple had two daughters and two sons. When Keith graduated from BYU, he had the opportunity to choose whether he would work in the family business or continue his education. The family business was tempting because it was well established and would provide financial security. But the four loves Keith had acquired on his mission—people, the gospel, the scriptures, and teaching—set him on a different course. He wanted to become a religious educator, and he wanted to teach the scriptures.

Leaving the beaten path, Keith traveled to Baltimore in 1952 to begin his graduate studies in the Bible at the Johns Hopkins University. While at Johns Hopkins, he studied under the tutelage of William Foxwell Albright, the most famous and productive Old Testament scholar of his day. Albright attracted America’s finest young students in the field, many of whom went on to become the great biblical scholars of the next generation. Keith was at home in that environment and later in the academic environment of BYU. His broad intellectual curiosity, his capacity to learn languages, his memory for things he had read and heard, and his emotional connection with the Bible all contributed to his success both as a student and as a scholar.

In 1958, Keith was offered a job as a religion professor at BYU. He decided to take it, even though he had not yet finished his PhD, planning to complete the degree from Provo. When he was preparing for his new job, his department chair told him that he was to teach six classes, which was the norm in those days. Thinking he was doing as instructed, he signed up to teach six different courses—not six different sections of one or two courses. He said years later that the work required to prepare and teach those courses so exhausted his intellectual resources that there never really was a chance after that of completing his doctorate, though he received a master’s degree. But he didn’t let the situation slow him down. He wrote and published important works on the scriptures and helped train a generation of Latter-day Saint scholars after him to do the same. Even without having finished a PhD, he eventually rose to the rank of full professor. He retired from BYU in 1990.

Keith’s most well-known scholarly contribution to the Church was his explanation of the Sticks of Joseph and Judah mentioned in Ezekiel 37. In articles published in the Ensign, he wrote that the “sticks” were writing tablets, such as those that have been discovered in ancient archaeological contexts. The tablets he described were made of wood and coated with wax, and writers inscribed their words in the wax.[4] Keith’s explanation gained wide currency in the Church and was even included in a footnote in the LDS edition of the Bible at Ezekiel 37:16: “Wooden writing tablets were in common use in Babylon in Ezekiel’s day.”

My long association with Keith began in 1974 when I was a BYU student in search of courses on the ancient Near East. The courses I was looking for didn’t exist, so I was referred to Keith to direct me in a regimen of selected readings. Under his guidance, I read wonderful books on Mesopotamian and Egyptian history—books that inspired my own career path. Keith was the perfect mentor for those readings. Not only did his own excitement for the subject matter surpass even that of the authors themselves, but that excitement was contagious. For me, it was an inspiring experience to be in his small, cramped office in the basement of the old Joseph Smith Building, surrounded by books from floor to ceiling, with Keith’s desk piled a foot high with books and papers, and with boxes on the floor full of index cards containing the notes he had taken over the years.

Keith taught in the classroom with the same passion with which he did everything else. He loved Jesus Christ and the prophets who represented Him, but he also loved the scriptural records of their words and activities. He had the ability to feel the Old and New Testaments as though he had lived them himself. His teaching was a high-energy experience for those who witnessed it. He taught with emotion, joy, and obvious love for the subject matter. In the classroom, his great verbal gifts were on display, as was his capacity to tie together all the scriptures, both ancient and modern. Never mind that, seemingly oblivious to the calendar, he was sometimes still in Genesis when his colleagues teaching the same course were already in 1 Samuel. My current Religious Education colleagues David Seely, Richard Holzapfel, and Dana Pike also took classes from and were inspired by Keith Meservy, showing that his influence continues to be felt by later generations of students today.

Keith’s Bible was the most used copy I had ever seen. Virtually every page of it was covered with underlines and highlights. He whipped its pages back and forth with such speed, as he hurried from one passage to another, that it is surprising that they weren’t all torn up. When he wanted to make a point, he would thrust his long, thin index finger into the pages with such force that I thought he would poke a hole in the book. I was always hesitant to let him touch my own Bible for fear that I would not get it back intact.

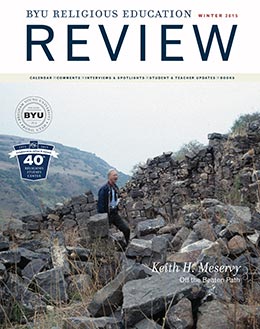

In 1972, Keith left the beaten path of the Joseph Smith Building in Provo and embarked on his first of five tours of duty with the BYU Jerusalem program. Teaching in the Holy Land became one of the passions of his life, and he did it very well. From that time on, the connection between the biblical text and its physical setting was paramount to him. He cared little for traditional interpretations but insisted on following the evidence. Thus, for example, he didn’t care that most Latter-day Saint visitors believed Jerusalem’s Garden Tomb was the place of Jesus’s burial. For him, the scriptural and archaeological evidence proved otherwise. And despite the generations of tour guides who identified one particular place as the location of Jesus’s trial before Pontius Pilate, Keith showed that it was on the wrong side of town. He wanted us—his students and fellow teachers—to get things right.

For Keith, the ultimate experience in teaching was to stand next to the walls of Gamla and read Josephus’s description of the Roman siege of that city; or to be in the ruins of Caesarea Philippi and read Matthew’s description of Jesus’s instructions to the Twelve; or to be on a boat on the Sea of Galilee and read the account of Jesus’s calming of the storm; or to stand in the City of David and read the accounts of the burials there of David and Solomon. At this last location, during the Palestinian uprising of 1987–91, Keith stood resolutely in the open and read the text under a barrage of rocks thrown by neighborhood youths, while his BYU colleagues hunkered down for safety in a nearby ancient tomb. He would not be deterred in his efforts to experience the Bible!

Nor did convention seem to deter him. He explored wherever he went, often well off the beaten path. Once his students found him standing high in a large fig tree harvesting ripe fruit for them to sample. Once his colleagues found him on top of the tower of a medieval building, to which he had gained access by climbing a wall studded with broken glass and hiking up stairs that were barely held together with wires. His explorer instincts led him into many places where more timid visitors never entered—all so he and those who were with him could experience the world of the Bible to the fullest extent possible. Every ancient place was an adventure for Keith, especially those off the beaten path. And every Bible story was his story.

Keith’s students could hardly keep up with him. Many noted with amazement at how he would burst into the classroom with his arms loaded with books and papers, ready to take on the subject matter. He was over seventy when he last taught in Jerusalem in 1997. When traveling with students, he was the first out of the bus and the last back into the bus, not always waiting to see if others were behind him. On the ancient sites, he was known for loping up hills with his long strides while his young students, gasping for breath, were trying to follow. Keith had a habit of bounding up stairs three or four steps at a time. That didn’t serve him well one day when he charged up the steep steps out of Lazarus’s tomb and knocked himself out when he hit the top of the entrance. Students behind him caught him and brought him out of the tomb. The event became a favorite story among his children and grandchildren because the concussion destroyed his sense of taste, and afterwards he was known to eat and enjoy foods that no one else thought were appetizing.

Keith was always a teacher, even in his private conversations and certainly in his academic writing. For a decade, he served in a calling from the Church to write lessons for the Gospel Doctrine manuals. Throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s, Church members all over the world were blessed by the scholarship and passion that he poured into those lessons. In addition, his conversations with colleagues were teaching experiences for them. He loved to talk about the scriptures and was not afraid to argue his case with vigor, all the while showing through his big smile that he loved those with whom he was thus engaged.

Love, indeed, was a trait that characterized all that Keith did. The four loves he had acquired on his mission stayed with him forever. First on that list, of course, was his love for people. Those close to him noted that in any issue regarding the conduct of others, he always took the side of compassion—not of judgment or condemnation—recognizing the frailties of others and wanting to cut everyone else enough slack to give them the chance to grow. His deep spirituality and deep love of God engendered in him a gentle, kindly nature toward others. Because guile was so foreign to his own character, he was nearly blind to the faults of others but fully able to perceive their strengths.

After a long bout with leukemia, Keith Meservy died on April 27, 2008. Because his passing was not unexpected, he drafted his own obituary. In it, he noted that he had “changed his address . . . from this world to the next.” But in that new venue, he was still exploring. “Now,” he wrote, “he is meeting those ancestors who left their comfortable homes in foreign lands to come to Zion. These forsook all that made their lives comfortable—their beloved countries, occupations, friends, associates and relatives and made it possible for them and all their posterity to enjoy the fullness of the blessings that God in these last days is extending to his children.”[5] Keith may have had to go off the beaten path to meet all those ancestors. But notice that with these words, written not for them but for us, he continues to be a teacher.

Notes

[1] Keith H. Meservy, unpublished obituary, http://

[2] Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson, “Lessons from the Scriptures: A Conversation with Keith H. Meservy,” Religious Educator 10, no. 2 (2009): 69.

[3] Keith H. Meservy, unpublished autobiographical sketch, 86; in possession of family.

[4] Keith H. Meservy, “Ezekiel’s ‘Sticks’,” Ensign, September 1977, 22–27; “Ezekiel’s Sticks and the Gathering of Israel,” Ensign, February 1987, 4–13.

[5] Meservy, unpublished obituary.