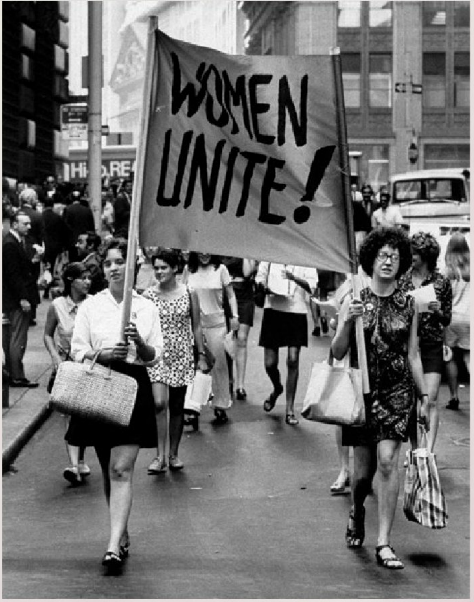

Three Decades after the Equal Rights Amendment

Mormon Women and American Public Perception

J. B. Haws

J. B. Haws (jbhaws@byu.edu) was an assistant professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this was published.

For Mormons who are interested in what the media is saying about their faith (meaning most Mormons!), there may have been some relief at the end of the 2012 US presidential campaign; a breather might have been welcome, so pervasive had talk of the “Mormon Moment” become. Yet, as Michael Otterson, director of Public Affairs for the LDS Church, has argued, since the 2002 Olympics, interest in Mormons has really never abated.[1] It seems to be the case that Mormonism has now become a fixture on the landscape of American public consciousness.

In recent months, much of the wider attention that has been directed at the faith has been driven by larger conversations about the place of women in the LDS Church. What this brief article seeks to highlight is an earlier chapter in this ongoing story, a story of the central role that issues related to Mormon women—and more important, women themselves—have played in shaping public perception of the Church and its members. That earlier chapter is the campaign for and against the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) in the 1970s and early 1980s.[2]

The Equal Rights Amendment finally passed Congress in 1972, a half century after supporters had first proposed it. In its final form, the one-sentence amendment seemed innocuous and almost patently obvious to a nation more attuned to civil rights and equality than it ever had been before. When Congress sent the amendment to the states, it seemed destined for quick adoption: twenty-two states ratified it in 1972 and eight states followed suit in 1973. But then the passages slowed—and finally stopped. With only the approval of a handful of additional states needed to make the amendment constitutional, the measure’s momentum ran out. In fact, the momentum reversed—five states even voted to rescind their earlier ratifications.

The unexpected part of this story, especially for readers three decades removed from the action, is that the opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment was initially spearheaded by women. Phyllis Schlafly, a committed Catholic and conservative political activist, launched STOP-ERA; STOP stood for “stop taking our privileges.” Schlafly argued that the ERA had the potential to strip the rights of women who wanted to be treated differently than men. She raised concerns that, under the amendment, women could be drafted into military service, or that women would no longer be eligible for alimony or child support, since there would be no unique protections or special-status recognition for women under the law.

Her message resonated with women nationwide, and the debate quickly took on religious overtones. Many conservative Christian women worried that the Equal Rights Amendment was an affront to their decisions to take on what they saw as biblically based roles of full-time wives and mothers. The Equal Rights Amendment came to represent, for them, an attack on traditional families.[3]

Latter-day Saint reaction to the Equal Rights Amendment followed many of these national patterns, but with a nuanced Mormon overlay to it—more about eternal gender identity and less about wives submitting to husbands. Mormon opposition was slow to develop and coalesce. The first well-publicized Mormon opposition to the ERA came from speeches by Mormon women: successive general Relief Society presidents Belle Spafford in July 1974 and Barbara Smith in October 1974. Spafford and Smith’s comments came after the Idaho legislature, with a number Mormons in its ranks, had already ratified the amendment in 1972. Spafford and Smith feared that the brevity of the amendment belied its potential disruptive power. They worried, like so many other women, that the amendment would give the Supreme Court too much interpretive license to change the definition of marriage, for example, or expand abortions-on-demand—and after the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, the ERA and the accessibility of abortions were inextricably linked. Many of the ERA’s most liberal proponents celebrated these potential societal disruptions; concerned opponents recoiled against them.[4]

What should not be missed in this history is the agency of women. After Barbara Smith spoke publicly against the ERA, she approached President Spencer W. Kimball to ask his opinion about the appropriateness of her remarks. President Kimball’s biographer notes that President Kimball’s journals “give no indication how he felt about the issue or how his attitudes may have developed.” But the Church News ran an editorial against the ERA just a few months after Barbara Smith’s address. Within two years, the First Presidency officially expressed its opposition to the ERA, noting that while the Church lamented many of the gender inequities in society, it did not think the broadly ambiguous amendment was the solution.[5]

Thousands of Mormon women mobilized in response to the Church’s invitation to express their opposition to the amendment. And, as the media reported it, these Mormon women had measurable effects on the way legislatures voted in Nevada, in Virginia, and in Florida.

Not to be missed, though, is that the Church’s strong anti-ERA stand also alienated many Mormon women who felt that many of society’s injustices could be remedied with the power the amendment would give to lawmakers and to the courts. Some Mormon women felt that the Church—which, they noted, historically had been an advocate of education for women, and theologically had departed from many traditional Christian positions about the culpability of Eve in the Fall—was giving in to a retrograde, Victorian-era view of women’s roles. Church leaders said that members could vote their consciences on this matter, yet some Mormon women and men wondered if the 1979 excommunication of Sonia Johnson belied that expressed toleration of political dissent. Johnson began making headlines with her “Mormons for ERA” position in the late 1970s. Her group’s tactics included public protests at general conferences and the Seattle Temple open house, as well as well-publicized media appearances in print and on television. She argued that Church leaders demonstrated “savage misogyny” (although she noted that this statement was taken out of context), and she recommended to the American public that they not allow Mormon missionaries into their homes until the Church reversed its ERA stand.[6]

Johnson’s excommunication for apostasy (“perhaps the most conspicuous media event in [LDS] Church history” to date, one observer called it)[7] and her vocal complaints about the political influence of Mormon money and out-of-state letter-writers introduced a new dimension into the media’s treatment of Mormons—or, perhaps more accurately, revived a dimension that had characterized reporting on Mormons a century earlier. That dimension was fear—fear of Mormon political ambitions, and fear of a Church whose centralized hierarchy could wield enormous influence in the lives of devoted, but mostly unthinking, disciples.[8]

The ERA was never ratified, and many policy-makers felt that the main anti-ERA argument, that women’s needs could be better served by specific piecemeal legislation, proved persuasive enough to effectively dull public interest in the amendment. But pro-ERA activists’ complaints about Mormon power did not disappear or dissipate, and in fact continued to color media portrayals of the Church well into the 1980s, just as other groups—like evangelical Christians and academics within and without the Church—expressed renewed concern about Mormon growth and Mormon intolerance of dissent.

Three decades later, the place of women in Mormon media is still being discussed. In July 2014, A Mormon columnist in the New York Times proclaimed that the “Mormon Moment” was over when Ordain Women’s Kate Kelly was excommunicated. The writer felt that the excommunication signaled the end of what many observers had noted in recent Mormondom, and that was the prominence of a diversity of voices and faces in, say, the “I’m a Mormon” campaign, as well as the world of social media. Yet Kelly’s excommunication, the columnist feared, would change all of that—it was evidence of a “crackdown” that would “[mark] the end of . . . a distinct period of dialogue around and within the Mormon community.”[9]

Others, however, have not been so sure.[10] While it is far too early to know how this will play out, one thing that does feel different today is that attention to Mormon women seems to be highlighting important Mormon diversity as much as, or even more than, perceived Mormon authoritarianism—and this is a theme that seems to have momentum in the national media. Recent coverage of the place of women in the LDS Church has carried signals to those outside and inside the faith that there is no one “valid” Mormon viewpoint, but rather there are many. One case in point: In a spring 2014 New York Times series on changes in the sister missionary program—and the attendant changes of the place of women in the Church generally—the following women were quoted: Linda Burton (general Relief Society president); Neylan McBaine, identified in the article as a moderate Mormon; Kate Kelly; Joanna Brooks; and, significantly, Maxine Hanks, identified with this telling line: “Maxine Hanks, one of the excommunicated feminist scholars, recently rejoined the church because she sees ‘so much progress’ for women, she said in an interview.”[11] Such diversity of opinions is certainly a notable change in the media coverage of the Mormon community.

Part of this surely has come about because the nature of media coverage in today’s world has changed, in that social media platforms have exponentially multiplied the number of potential media commentators. This means that a variety of Mormon women, in their own voices, are able to describe their experiences in, concerns with, and hopes for a Church to which they are deeply committed. This accessibility makes snap judgments—that split the camps into “faithful”/”unfaithful” sides—come off as unfair and unreflective of reality. Instead of only being polarizing, then, attention to these issues now seems to be opening space for productive conversations. Part of that space, too, seems to have been opened by institutional initiative on the part of the Church to reflect the richness and complexity of its own history and within its own people. What these current conversations might therefore do is sensitize Latter-day Saints and outside observers to additional layers in the “Mormons and the ERA” story and its aftermath, and warn all sides against easy assumptions: it would be just as wrong, we begin to see, to assume that every Mormon woman who favored the ERA rejected outright the idea of prophetic direction, as it would be to suppose that every Mormon woman who opposed the ERA was subservient and unthinking. These current conversations can prompt us to listen to each other more.

It says something that Neylan McBaine, characterized as “an orthodox believer” by one of her book’s endorsers, could write in her new book, Women at Church: Magnifying LDS Women’s Local Impact, that “the truth is found not in sweeping these tensions under a rug or bundling them into tidy packages of platitudes; it is in wrestling with them outright.” And it says something that McBaine’s book carries endorsements from Camille Fronk Olson, chair of the Ancient Scripture Department at BYU; from Juliann Reynolds, cofounder of FairMormon; and from Lindsay Hansen Park, founder of the Feminist Mormon Housewives Podcast.[12] It seems to say, at the very least, that there is room in the contemporary Church for a variety of voices and viewpoints, that Matt Bowman was right when he told National Public Radio in the fall of 2012 that coverage of Mitt Romney’s campaign had struck at the prevalent “myth” of Mormonism-as-“monolith.”[13] It also says, and forcefully so, that the agency of Mormon women is being better recognized than ever before in the role such agency has had—and will have—in shaping the meaning of “Mormon,” both in terms of a clearer public understanding and adherents’ self-understanding. Finally, it seems to say that the aspirations of Church members to rise to new heights are driven by the ideals of equality for which the Church itself stands. “We can be encouraged,” McBaine writes, “by the ways our doctrine opens doors to theological possibilities and potential that are not options in other faith communities.” The question she therefore asks is worthy of repeated reflection: “Are we practicing what we preach?”[14]

Notes

[1] Michael Otterson, interview, September 9, 2011, interviewed by author, transcript in author’s possession, 4.

[2] For studies of Mormon involvement in the Equal Rights Amendment campaign, see Martha Sonntag Bradley, Pedestals and Podiums: Utah Women, Religious Authority and Equal Rights (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2005); D. Michael Quinn, “A National Force, 1970s–1990s,” in The Mormon Hierarchy: Extensions of Power (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1997); and J.B. Haws, “The Politics of Family Values: 1972–1981,” in The Mormon Image in the American Mind: Fifty Years of Public Perception (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[3] See Daniel K. Williams, God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 108–111.

[4] See Jane J. Mansbridge, Why We Lost the ERA (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1986), 5.

[5] See Edward L. Kimball, Lengthen Your Stride: The Presidency of Spencer W. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2005), 176–178. The First Presidency’s statement is reprinted on pages 177–178.

[6] See “A Savage Misogyny: Mormonism vs. Feminism and the ERA,” Time, December 17, 1979, 80: “[Johnson] explains that the phrase was directed at Mormon culture in general.” Sonia Johnson argued later that the way she used the phrase in her speech was misappropriated by a reporter who applied the charge of misogyny specifically to Mormon leaders, whereas Johnson asserted she was speaking about all of Western culture: “It was inexplicable to me why they persisted in believing their misquote of the UPI misquote over evidence that proved without a doubt that I have never attributed ‘savage misogyny’ to either church leaders or Mormon culture.” Sonia Johnson, From Housewife to Heretic (Albuquerque, New Mexico: Wildfire Books, 1989), 334. On refusing the missionaries, see Diane Weathers and Mary Lord, “Can A Mormon Support the ERA?,” Newsweek, December 3, 1979, 88.

[7] Stephen W. Stathis, “Mormonism and the Periodical Press: A Change is Underway,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 14, no. 2 (Summer 1981): 48–49.

[8] One Mormon woman who added her name to a 1979 pro-ERA pamphlet, “Another Mormon View of the ERA,” said that she worried her signature “would either get me exed [excommunicated],” or that her husband would lose his job at a Church university. “But,” she said, “nobody bothered with me, we were overreacting I suppose.” Nancy Kader to J.B. Haws, email, December 11, 2014.

[9] Cadence Woodland, “The End of the ‘Mormon Moment,’” New York Times, July 14, 2014, http://

[10] See Nate Oman’s blog post, “Discussion, Advocacy, and Some Thoughts on Practical Reasoning,” Times and Seasons, June 24, 2014, http://

[11] Jodi Kantor and Laurie Goodstein, “Missions Signal a Growing Role for Mormon Women,” New York Times, March 1, 2014, http://

[12] Neylan McBaine, Women at Church: Magnifying LDS Women’s Local Impact (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2014), 6. The “orthodox believer” description comes from Lindsay Hansen Park’s blurb inside the book’s cover.

[13] Quoted in Liz Halloran, “What Romney’s Run Means for Mormonism,” National Public Radio, November 1, 2012, http://

[14] McBaine, Women at Church, 61, 176.