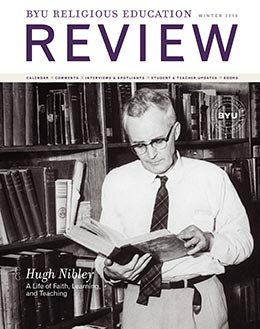

Boyd Jay Petersen (boyd.petersen@uvu.edu) was the Program Coordinator for Mormon Studies at Utah Valley University and was teaching in the English department when this was wirtten. He also teaches for the BYU Honors Program as a writing instructor. He wrote Hugh Nibley: A Consecrated Life, which won the Best Biography Award from The Mormon History Association.

As Halley's Comet glittered in the March sky of 1910, the forty-six states of America were only ten years into a new century full of hope and optimism. The Wright brothers' famous flight had occurred only seven years earlier. The Model T Ford had been coming off the assembly line for a year, and William Howard Taft, the acknowledged successor of the popular progressive Teddy Roosevelt, was president of the United States. Amid such promise, likely no more hopeful and prosperous a place existed than Portland, Oregon. Employment was keeping pace with a population growing by almost twenty thousand each year. In Portland, Alex Nibley ran the Oregon Lumber Company, a business started by his father, Charles W. Nibley, and Charles's partner, David Eccles.

On March 27, a baby boy was born to Agnes Sloan, Alex Nibley's wife. They named him Hugh Winder Nibley. Hugh and his three brothers attended Portland public schools, but the family hired tutors to instruct them in music and language. Hugh supplemented his early studies by exploring the redwood forests near his home, aware that his family's business was destroying them. Hugh later wrote about that destruction:

As we stood on the little station platform at Gearhart Beach at the end of our last summer there, the family could hear a lumber company a mile away in the towering woods noisily beginning what was to be the total destruction of the greatest rain forest in the world. My father obligingly explained that the lumber company was only acting in the national interest, since spruce wood makes the best propellers, and a strong air force is necessary to a strong and free America. But it was another message that reached and offended childish ears from that misty battleground of man against nature.[1]

In 1921, the family moved to Los Angeles, where Alex would manage other business interests for his father. Hugh attended Los Angeles High School and enjoyed learning. Three things became his passions: astronomy, art, and English. His obsession with astronomy led him to paint over the streetlight outside his bedroom observatory, and on one occasion when he came down to breakfast, the family noticed there was something different about him. "We kept looking at him," recalls his brother Sloan. "There was something wrong and we couldn't figure it out. Suddenly, one of us noticed that his eyelashes were gone." Hugh had cut them off so he could see better through the telescope.[2]

Hugh also discovered a natural ability as an artist. His medium was primarily pencil sketches, and his specialty was tall ships. Despite his ability, he remained humble. Eleven-year-old Hugh wrote his grandfather in 1921, "The other night I stayed up till two o'clock (mainly drawing) while my gentle guardians were out. Drawing is like learning to play the violin. The more you know, the less you think you know. I am positive I know an awful lot."[3]

Two gifted and devoted high school English teachers nurtured Hugh's love and gift for language and literature. "In my first year in high school," Hugh later wrote, "the object of the [class] was to memorize as many notable passages of literature as possible."[4] And memorize he did. By age twelve, he had memorized "all the major Shakespearian tragedies" and the works of many major poets.[5] And this love for language and literature led him to seek out the roots of English literature. He studied Anglo-Saxon, then Latin, then Greek.

When Hugh graduated from high school in 1927, he had proved that he had great intellectual curiosity and ability. He was also an able outdoorsman. His family worried, however, that his social development left something to be desired. His father remarked in a letter to Hugh's grandfather, "The poor kid has been wrapped up so in his books all his life that he lacks experience in traveling and caring for himself among civilized beings. He is perfectly able to take care of himself out in the mountains alone with the bears and the wild cats."[6]

At age seventeen, he was called to the Swiss-German Mission. Hugh was a dutiful missionary, but his main source of guilt was his diversion into his secular studies. On March 16, 1929, Hugh confided to his journal, "Can one hour of Greek a day be playing the devil with my mission?" One intellectual diversion that he felt no guilt over was his studies in the Book of Mormon. "The Book of Mormon is giving me greater joy than anything ever did," he wrote on March 25.

Following his mission, Hugh returned home to attend UCLA, where he graduated summa cum laude in 1934, and then went to graduate school at Berkeley. During this time he witnessed firsthand the effects of the Great Depression. Hugh's family had been quite wealthy and their wealth survived through most of the 1930s, but as it disappeared Hugh's father became more desperate to regain the wealth. For the 1936–37 school year—his final year of graduate work at Berkeley—Hugh received a university fellowship. The cash award provided for all of Hugh's school and living expenses. When Hugh received the fellowship money, his father approached him for a loan. "Dad said he needed the money just over the weekend," Hugh recalls, "to rescue one of [his] mining deals." Hugh's mother pressured him too, assuring him that the money would all be back by the following Monday. But, Hugh says, "I never saw the money again."[7]

Hugh later remembered this period of his life as a desperate time when "the bottom of the world fell out." Hugh was not certain that he would be able to continue his studies, and he didn't know where to turn for help, but he was fortunate enough to be offered a translation job that allowed him to continue his studies, an opportunity he attributed to providence.

Despite the fact that Hugh was able to continue his studies, he was extremely discouraged at this time. When he returned to his family's home in Hollywood for the Christmas vacation at the end of 1936, his discouragement had become a full-blown depression, saying, "Those were desperate times."[8] He even began to doubt the truthfulness of the Church. "I thought there were certain flaws in the gospel," says Hugh.[9] "I was terribly bothered about this afterlife business and that sort of thing. I had no evidence for that whatever." That all changed when Hugh came down with appendicitis and was taken to the hospital. When the doctor turned the ether on, Hugh swallowed his tongue and stopped breathing. While unconscious, Hugh experienced a life-after-life experience that reoriented his life. "I didn't meet anything or anybody else, but I looked around, and not only was I in possession of all my faculties, but they were tremendous. I was light as a feather and ready to go."[10]

This experience had a profound influence on Hugh. Certainly, education remained important to him throughout the rest of his life. However, this experience was a "higher" form of education that helped him recognize that the most important tests in this life are not administered in the classroom. This knowledge helped him not take life too seriously, writing, "We're just dabbling around, playing around, being tested for our moral qualities, and above all the two things that we can be good at: we can forgive and we can repent."[11]

In 1938, he took his PhD from Berkeley and then taught at Claremont, Scrips and Pomona Colleges during the years before World War II. He joined the army in September of 1942 and served as an intelligence officer, driving a jeep onto Utah Beach on D-day, landing in a Horsa glider in Holland, and serving at Mourmelon-le-Grand at the Battle of the Bulge.[12]

Following the war, Hugh worked as an editor at the Improvement Era, where he became acquainted with Elder John A. Widtsoe. Elder Widtsoe urged Hugh to apply to teach at BYU, and recommended him to then-president Howard S. McDonald. Widtsoe described Hugh as "a book worm of the first order." He continued, "He will probably annoy his wife, when he marries, all his life, by coming home late at night—too late for dinner—and by sitting up all night with his books." At the bottom of the letter, Elder Widtsoe wrote, "I believe we must keep this man for our use."[13] Hugh accepted a position as assistant professor of history and religion at BYU.

Elder Widtsoe did have one concern about Hugh when recommending him to teach at BYU—his marital status. Hugh was a thirty-six-year-old bachelor. In a letter to his close friend Paul Springer, Nibley described Widtsoe's prodding as "the rising admonition of the brethren that I get me espoused."[14] Obedient to the end, Nibley told Elder Widtsoe that "I would marry the first girl I met at BYU."[15] On one of his first days on campus, May 25, 1946, Hugh walked into the housing office, and Phyllis Draper—the receptionist—was the first young woman he met there.[16] With just that one encounter, Hugh decided that he was going to marry Phyllis, whom he later described to his mother as "delectable and ever-sensible."[17] They courted until August 18, when he popped the question.[18] The couple was married on September 18. About their whirlwind courtship, Hugh quipped, "That's why it's called BYWoo, I guess."[19] Hugh and Phyllis reared eight children in a house full of books, music, and guests.

Hugh became a one-man campus, teaching language courses in Latin, Arabic, Greek, Russian, Hebrew, and Old Norse as well as courses on early Christianity, ancient history, ancient Near Eastern religion, and, of course, the Book of Mormon. He began publishing on two fronts. First, he published apologetic articles for a Mormon audience, constructing arguments that deftly defended Mormon beliefs from detractors. His first publication that captured the attention of LDS readers was a response to Fawn Brodie's No Man Knows My History, a biography of Joseph Smith that took a naturalistic view of Mormon origins. Hugh's response, entitled No, Ma'am, That's Not History, was acerbic and witty, but established him as a defender of the Church. He followed this with a steady stream of articles mostly published in the Church magazine the Improvement Era that established a Middle Eastern background for the Book of Mormon. Hugh also published in some top peer-reviewed journals aimed at a non-Mormon academic audience.

Hugh came to be seen as an apologist, in the classical sense of the word, whether defending the Church against anti-Mormon attacks or preemptively laying out evidence for the restored gospel. His anti-anti-Mormon writings have been collected in the volume Tinkling Cymbals and Sounding Brass, where Hugh writes with great sarcasm about the techniques employed by anti-Mormon writers. His greater legacy, however, has been to set the Book of Mormon, the Book of Abraham, Book of Moses, and the temple into an ancient Middle Eastern milieu. He broke ground in these areas and dramatically affected the way Latter-day Saints read and interpret their scriptures.

In the 1970s Hugh began increasingly to speak out against problems he saw with Mormon culture, specifically along the Wasatch Front. He lamented our disregard for the environment, our prioritizing of personal wealth over the law of consecration, and our tendency to be military hawks instead of heeding the admonition to "renounce war and proclaim peace" (D&C 98:16). His social criticism, like his apologetics, was rooted in his understanding of Mormon scripture and prophetic words. Hugh's belief in an ethic of environmental responsibility was born not only of his experiences growing up in the woodlands of Oregon but also from his close reading of Mormon scripture. He took seriously the Mormon concepts of a spiritual creation and stewardship. Likewise, Hugh's call for social justice and anti-materialism stemmed not only from his witnessing the effects of the Great Depression but from his reading of the Doctrine and Covenants and the words of prophets like Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, and Spencer W. Kimball. And Hugh's strong antiwar positions resulted not only from his experience as a student of classical history and as an intelligence officer in World War II but from his reading of the Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants.

Hugh Nibley witnessed almost the entire twentieth century. He heard family conversations about World War I and saw the staggering effects of the Great Depression and of World War II. When he was a boy, tall ships were sailing into the harbor of his Portland home town. He saw the world move from jetliners to spaceships. He also witnessed firsthand the transition of Mormonism from a Utah church to a worldwide church. When Hugh was born, there were only 398,000 members and four temples. Today there are over thirteen million members and 130 temples, with twenty more planned. In addition to witnessing this explosive growth, Hugh had a significant influence on the direction the Church took in its approach to the Book of Mormon, the Pearl of Great Price, and the temple. He set a wonderful example of faithful discipleship, all the while showing us that if we take the gospel seriously, we can laugh at ourselves and have a good time during our days of probation. And, most importantly, he touched many individual lives as he urged us to take the law of consecration more seriously, respect the environment, and work for peace.

Notes

[1] Hugh Nibley, "An Intellectual Autobiography," in Nibley on the Timely and the Timeless (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1978), xix–xx.

[2] Interview with Sloan Nibley, n.d., Faith of an Observer, complete transcripts, 531.

[3] Hugh Nibley to Charles W. Nibley, June 30, 1921; family correspondence, Charles W. Nibley Collection, Church History Library.

[4] Hugh Nibley, Approaching Zion (Salt Lake: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1989), 545–46.

[5] Interview with Hugh Nibley by Mark A. Eddington, September 22, 2000.

[6] Alexander Nibley to Charles W. Nibley, November 1, 1927; L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, C. W. Nibley collection, Mss. 1523, box 1, folder 3.

[7] Complete transcript of interviews from Faith of an Observer, 29.

[8] Faith of an Observer, 221.

[9] Faith of an Observer, 222.

[10] Faith of an Observer, 229.

[11] Faith of an Observer, 229.

[12] I describe Hugh's war experience in three chapters in the biography and my brother-in-law, Alex Nibley, created an excellent contextualized memoir of Hugh's war years in Sergeant Nibley, Ph.D.: Memories of an Unlikely Screaming Eagle (Salt Lake: Shadow Mountain, 2006).

[13] John A. Widtsoe to Howard S. McDonald, March 14, 1946, BYU Archives, Howard S. McDonald Presidential Papers, box 3, folder 7.

[14] Hugh Nibley to Paul Springer, about August 5, 1946.

[15] Todd F. Maynes, "Nibleys: Pianist, Scholar, Brilliant But Different," Daily Universe, November 1, 1982, 7.

[16] Hugh Nibley's personal journal.

[17] Hugh Nibley to Agnes Sloan Nibley, postmarked August 23, 1946.

[18] Nibley's personal journal; Hugh Nibley to Agnes Sloan Nibley, August 19, 1946.

[19] Maynes, "Nibleys," 7.