Terror In Jackson County

Bruce A. Van Orden, "Terror In Jackson County" in We'll Sing and We'll Shout: The Life and Times of W. W. Phelps (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 95–110.

An irreconcilable conflict had been brewing in Jackson County between the Mormons and the original settlers ever since the “Lamanite missionaries” arrived there in January 1831. The conflict was acute because neither side evidently had any empathy for the other when it came to religion, culture, politics, landholdings, and economics. Furthermore, a radical disagreement developed between the two groups over Indian relations and slavery. They were on a collision course from the beginning. As editor of the only two newspapers in the county and as proprietor of the Mormon press, William W. Phelps was a major player in the conflict. Before the horrible scene played itself out in 1833, all Jackson County Latter-day Saints, whether new to the vicinity or not, became embroiled in an ugly and occasionally bloody tug-of-war.

Reasons for the Mutual Antagonism

The anger that erupted early in Jackson County over Mormon religion and preaching was not at all unusual. Nearly everywhere in America where Mormon missionaries had preached since the Church’s first year had witnessed similar antagonism. The crucial difference in Jackson County was Joseph Smith’s declaration in July 1831 that the county was the location of a latter-day Zion and the future site of the New Jerusalem. This assertion ended up being a nagging thorn that first irritated and then inflamed the white settlers. Unabashedly, Phelps promoted through the press the Mormons’ quest to build Zion, a quest that would eliminate any “gentiles,” that is, original inhabitants of Jackson County.

Alexander Majors, a teenaged Jackson County resident at the time, reported, “The community [was] composed of Methodists, Baptists of two different orders, Presbyterians of two different orders, and Catholics, and a denomination calling themselves Christians.”[1] Reverend Benton Pixley, who had been sent to Independence by a missionary society, led the charge of Christian groups against the Mormons. Newel Knight reported, “His talks were of the bitterest kind, his speeches perfectly inflammatory, and he appeared to have an influence among the people, to carry them in his hellish designs.” Knight added that Pixley’s efforts “were seconded by such men as Reverends McCoy, Fitzhugh, Boggard, Kavanaugh, Lovejoy, Lukins, Hunter and others.”[2] Phelps stated that Pixley “was a black rod in the hands of Satan. . . . He wrote horrible falsehoods about the Saints which he sent to religious papers in the East, from time to time, in order to sour the public mind against them.” Pixley also used his influence “among both Indians and whites to overthrow the Church in Jackson county.”[3]

Typical Mormon zeal about their beliefs and holy claims quickly antagonized these religious leaders, who in turn whipped up their devout followers. Alexander Majors claimed that the Saints conducted “tantalizing talks” when they dealt with the other citizens. “They claimed that God had given them that locality, and whoever joined the Mormons, and helped prepare for the next coming of the Lord Jesus Christ, would be accepted and all right; but if they did not go into the fold of the Latter Day Saints, that it was only a matter of time when they would be crushed out.” He added that Mormons believed Jackson County was their “promised land and they had come to possess it.” He also said that the Mormon leaders asserted that “the Lord had sent them there and would protect them against any odds in the way of numbers.”[4]

Phelps participated in these “tantalizing talks.” It had been his nature as an Anti-Masonic firebrand to stir the political and social pot of a community. He probably did this in Independence as well. Phelps’s printshop was just a few yards from courthouse square, where all manner of people gathered each day to discuss politics and social affairs. He did his fair share of tantalizing the opposition with his vociferous millennial views. Phelps’s writings were certainly open to public view; everybody knew he was the editor of The Evening and the Morning Star. Phelps was not alone among the Mormons in stirring the pot. Other leaders such as Edward Partridge, Sidney Gilbert, Oliver Cowdery, and John Whitmer, as well as average Church members, also spoke out.

Religious conflict between the Mormons and the others was not confined to contention over the “unusual” Mormon beliefs and practices. The majority of the Jackson Countians were actually irreligious by nature and tradition. This infidelity to religion and God was equally as unimpressive to Phelps as was sectarian antagonism. Most Saints were like Phelps and had strong New England roots. They valued congregational Sabbath worship, education of their children, and refined personal decorum. These values clashed with the “rough and ready” Missourians, many of whom had come west precisely to avoid any community or religious interference in their lives. There were no schools for their children. A missionary from the American Home Missionary Society who had been sent to Jackson County before the arrival of the Mormons described Independence as “a godless place, filled with so many profane swearers. . . . The majority of the people make a mild profession of Christian religion, but it is mere words, not manifested in Christian living.” He wrote of saloons, prostitutes, horse racing, cockfighting, gouging, and other forms of violence. “Christian Sabbath observance here appears to be unknown. It is a day for merchandising, jollity, drinking, gambling, and general anti-Christian conduct.”[5]

Puritanical by nature, Phelps found himself in opposition to the worldly environment around him. He later recalled, “We could not associate with our neighbors who were many of them of the basest of men and had fled from the face of civilized society, to the frontier country to escape the hand of justice, in their midnight revels, their Sabbath breaking, horse racing, and gambling, they commenced at first to ridicule, then to persecute.”[6]

Some original settlers viewed the Latter-day Saints as economically exclusive because the Saints lived on Church lands and traded entirely with the Church store or mechanical shops in accordance with their living the law of consecration and stewardship. Others accused Mormon immigrants of pauperism when the new arrivals could not occupy purchased lands because of diminished Church resources. Neither of these economic conditions augured well for harmonious relationships.

The original settlers, like most Americans, feared and often despised Indians. This antipathy increased in the early 1830s as the government resettled eastern tribes on lands just west of Jackson County. After the 1832 Black Hawk War in Illinois, western Missouri citizens petitioned Congress to establish a line of military posts for their protection. In absolute contrast, Mormon elders, most assuredly including Phelps, declared the prophetic destiny of the Native Americans. Again and again Phelps printed reminders in The Evening and the Morning Star that the Indians were “gathering” to these western regions in fulfillment of Old Testament and Book of Mormon prophecies. For example, as Phelps printed news of Indian resettlement from other newspapers, he wrote, “We continue to glean items of Indian news, and it is really pleasing to see how the Lord moves on his great work of gathering the remnants of his scattered children.”[7] Phelps freely cited scriptural prophecies concerning the Indians. No wonder, then, that the old settlers were frightened that the Mormons would band with Indians to help them conquer the area for their New Jerusalem. (Phelps’s interpretation of the effects of the 1830 Indian Removal Act contrasts with twenty-first-century historical interpretations that the Native Americans were brutally treated.)

Many of the transplanted southerners in Jackson County owned slaves, but the majority did not. However, they all prized their right to do so. They abhorred abolitionism, a sentiment held by some New England, New York, and Ohio Mormons. Phelps held mild abolitionist views, as evidenced by his statements in his previous paper, the Ontario Phoenix. One of the planks of Anti-Masonry, of which he had been a part, was the gradual abolition of slavery. Phelps reported in The Evening and the Morning Star, “In connection with the wonderful events of this age, much is doing towards abolishing slavery, and colonizing the blacks, in Africa.”[8] Some Missourians believed the false rumor that the Saints were interfering with the settlers’ slaves and were working for their freedom.

Obviously, the Mormons posed a political threat to the original residents. By early summer 1833, over one thousand Latter-day Saints had arrived in the county, representing more than a third as many as the combined other citizens. Mormons had been streaming in by the dozens each week, and it was boasted that thousands more were coming. Simple arithmetic attests that by 1834 or 1835, Mormons could have wrested political control from those who had established Jackson County and Independence. Because Phelps had political experience, he no doubt harbored ideas that he could become one of the elected officials of Jackson County once Mormons had sufficient voters.

Fragile Peace Comes to an End

Harmony never did exist between the Mormons and Gentiles in Jackson County. Violent episodes occurred often before the summer of 1833. Amazingly, outright fighting had not broken out already.

On July 1, 1833, Reverend Pixley, the Mormons’ religious archenemy, started distributing a tract entitled Beware of False Prophets. He carried this from house to house to incense the citizens against the Mormons and to drive them from the county.[9] W. W. Phelps, who had not yet completely prepared the July issue of The Evening and the Morning Star, hastily wrote an answer to Pixley’s little pamphlet and printed it on the first page of his paper. It bore the same title as Pixley’s: “Beware of False Prophets.” The Phelps press printed the July issue and got it out about the tenth of the month.

Phelps started by explaining, “Our object in quoting this caution of our blessed Savior, is to give the saints and the world, inasmuch as the inhabitants thereof wish to enter in at the door and be saved, a few hints relative to false prophets.” The article had a plain message: “There can not be but one church of Christ, as there is one Lord, one faith, and one baptism.” Phelps claimed that many ministers from the diverse denominations came forward “supported by large salaries” and “striving shrewdly to maintain the systems invented by men since they rejected the gift of the Holy Spirit.” He said these men came “in sheep’s clothing” but were “full of pride, and full of contention; fond of vanity.” Phelps suggested that the proper means of ascertaining a true prophet was to “compare his prophecies with the ancient word of God, and see if they agree,” because the scriptures declare, “The Holy Ghost dwelleth not in unholy temples. By their fruits shall they be known.”[10] Clearly, Phelps’s rejoinder did not calm any waters but rather further incensed the Saints’ opponents. Protestant ministers took umbrage with Phelps’s challenges to their authority and integrity.

By early July, the powder keg was about to be lit. A crucial event took place at a Sunday Mormon preaching meeting at the “temple lot.” Church leaders invited William E. McLellin, one of the Missouri Saints who was a noted orator, to deliver the sermon. McLellin reported that a large number of local citizens with whom he had formed an acquaintance also turned out to hear him preach. He chose as his text for his two-hour sermon “The Gathering of the Last Days.” McLellin, like Phelps, was a known firebrand and had the reputation of whipping up the emotions of his listeners. Another speaker, name unknown, prophesied that within five years all unbelievers in Jackson County would be destroyed. McLellin reported in reminiscences that that very day some of the principal men of Jackson County met together and formulated a document that they circulated “pledg[ing] to each other, their property, their lives, and their sacred honors, to drive all the members of the Church of Christ, (whom they called Mormons,) from the county, peaceably if they could, but forcibly if they must.”[11]

Indeed, the now-militant Jackson County leaders met secretly on the Fourth of July and decided to draft a manifesto of beliefs. Over the next several days a committee of leading male citizens composed the document that came to be known as the “secret constitution.” The authors went door-to-door seeking signatures. Hundreds of citizens signed the document. It began, “We the undersigned citizens of Jackson County believing that an important crisis is at hand, as regards our civil society in consequence, of a pretended religious sect of people that have setled and are still setling [sic] in our County styling themselves Mormons . . .” The petitioners declared that they intended to rid their society of this Mormon menace “as by the law of self preservation.” They called for a meeting to take place at the courthouse on Saturday, July 20. Signers included such leading citizens as the county clerk, assistant county clerk, jailor, Indian agent, postmaster, militia colonel, two justices of the peace, constable, and two well-to-do merchants.[12]

The petition asserted that Mormons had interfered with the slaves and advocated “inviting free negroes and mulatoes [sic] from other States to become mormons, and move and settle among us.” The exact opposite was true. In July’s Evening and the Morning Star, Phelps actually cautioned Mormon missionaries about proselytizing among slaves and former slaves.[13] When he learned that he was misunderstood, Phelps quickly responded with an “Extra” explaining that the Church had no intention to invite free blacks to Missouri. “We say, that none will be admitted into the Church; for we are determined to obey the laws and constitutions of our country, that we may have that protection which the sons of liberty inherit.”[14] These disclaimers had no effect on these incensed enemies. They chose to believe that Mormons had every intention of bringing black converts to Missouri and of aligning with slaves for an uprising.

During this difficult time, Mormon families in Independence sometimes gathered together at the home of Bishop Edward Partridge for their protection. The bishop’s daughter Emily later wrote in her memoir that Church members had no idea what the mob might do. Thus the brethren armed themselves and held regular prayer meetings. “Children had heard so much about the mob that the word was a perfect terror to them. They would often cry out in their sleep and scream ‘the mob is coming, the mob is coming.’”[15]

Emotions of the anti-Mormon faction were rattled by the soon-to-be-published Book of Commandments.[16] The book’s publication was no secret, for residents not only had read some of the revelations in the Star but had learned in the same newspaper that the compilation was nearly finished and that the book would shortly come out for sale. As prompted by the religious ministers, leading local residents did not want this explosive book to reach the public.[17]

Vigilante Violence

Missouri antagonism against the perceived Mormon threat reached the boiling point on the fateful day of July 20, 1833. In the morning the appearance of a large company of men and women startled the Mormon settlers working at the ferry on the Big Blue River. Rarely did such a large group gather to cross the river. According to David Pettegrew, a Mormon observer, “they had a solemn and determined look. I saw several women in their company who seemed to be more interested in mobbing than their husbands.”[18] They proceeded on to Independence, where a group of nearly five hundred gathered from all over the county for the scheduled meeting at the courthouse.

The vigilantes passed whiskey around and distributed another petition. It outlined again the various grievances the original settlers had fostered against the Mormons: “the corrupting influence upon our slaves,” “their pretended revelations from Heaven,” “the contemptible gibberish with which they habitually profane the Sabbath and which they dignify with the appellation of unknown tongues,” “the grossest superstitions,” “the most abject poverty,” and the realization that “the day is not far distant, when the government of the county will be in their hands.”[19]

Sometime in the afternoon a committee of thirteen representing the large assemblage walked over to W. W. Phelps & Co. to talk with Mormon leaders. Representing the Church were the leading high priests, including William W. Phelps.[20] Isaac Morley, one of the high priests, reported: “They requested us to leave the County forthwith, We told them that we should want a little time to consider upon the matter, they told us that we could have only fifteen minutes, we replyed to them that we could not comply or consent to their proposals with in that time, one of them observed and said then I am Sorry I think it was Lewis Franklin Said he then, the work of destruction will then Commence Ammeadiately.”[21]

In the course of the confrontation, the committee demanded that the Mormons “should immediately stop the publication of the Evening and Morning Star, and close printing in Jackson County.”[22] The representatives returned the few yards to the courthouse to the large and restless group that was becoming moblike in character. In a few minutes, passions erupted and all the men voted to raze the Phelps printing establishment and to destroy the type. They believed destroying Phelps’s Mormon press would be the first necessary step to thwarting the Mormon movement.

Among the citizens at the courthouse was a man whose wife Sally Phelps had recently attended in childbirth. This individual slipped out of the meeting and alerted the Phelps family. Phelps, realizing that he would be a target of much of the hatred, quickly exited and found a hiding place. He took with him some copies of the galley sheets of the Book of Commandments. John Whitmer or another printing office employee spirited the handwritten manuscript book of revelations to safety.[23]

Sally dressed the children and then, bearing sick little James, still an infant, prepared to ride off with a wagon and team of horses. She was threatened with death if she didn’t leave.[24] Inadvertently, she left two of her sons, Waterman and Henry, in the building.[25]

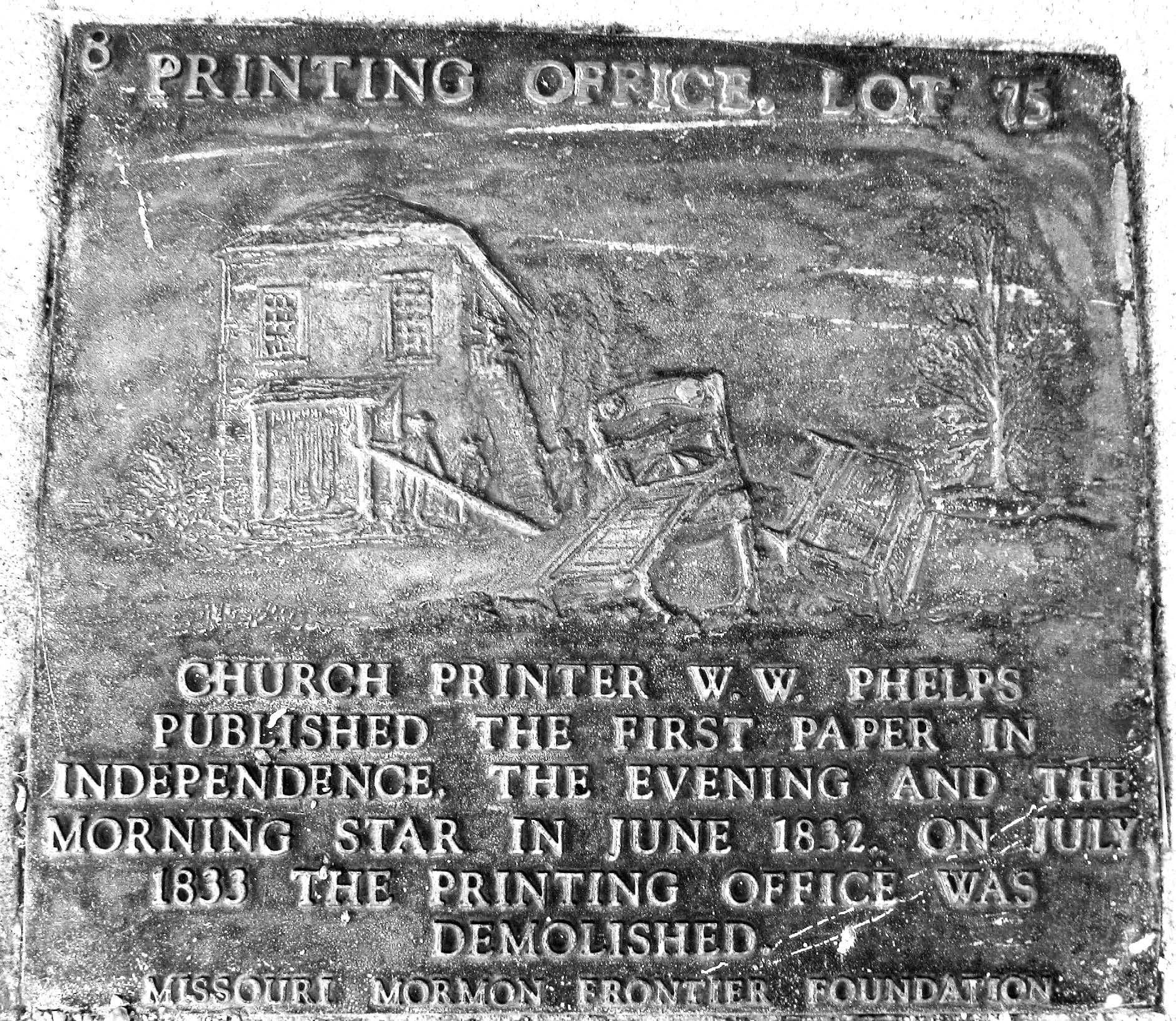

A plaque in the sidewalk at the site of the W. W. Phelps & Co. printing office, Independence, Missouri. Photograph by Bruce Van Orden.

A plaque in the sidewalk at the site of the W. W. Phelps & Co. printing office, Independence, Missouri. Photograph by Bruce Van Orden.

Following the frontier propensity to use force to resolve a conflict, about three hundred men dashed over to the printshop, the first target of their destruction. Some men who disagreed with this mob action went home. But there were plenty of hands to do the dirty work. Samuel Weston, a justice of the peace, grabbed a club to ward off Mormon defenders.[26] John Whitmer reported that the mob threatened to kill the attending Mormons if they did not leave immediately.[27] A standoff took place. Alexander Majors remembered, “While the mob was forming, many of the elders stood and looked on, predicting that the first man who touched the building would be paralyzed and fall dead upon the ground. The mob, however, paid no attention to their predictions and prayers for God to come and slay them, but with one accord seized hold of the implements necessary to destroy the house.”[28] Some men hurried up the flight of steps on the outside of the building and knocked open the door to the pressroom with a piece of timber. Majors reported that “within the quickest time imaginable [they] had it torn to the ground, and scattered their type and literature to the four winds.”[29] All Mormon witnesses likewise testified that the Phelps house and printshop was “demolished,” the furniture destroyed, the type scattered, and the press broken from being thrown from the upper window.[30] Phelps later described additional items that had been damaged or destroyed: “printing paper, printing ink, blank deeds, blank forms of various other things, unprinted manuscripts, and other unpublished works.”[31]

This was a terrible ordeal for Sally Phelps and her little children, including the sick infant James.[32] When she was a safe distance away, Sally thought she saw her house burning. Undoubtedly, there were some flames from burning papers. Sally located an old stable as a place for her family to sleep.[33] William spent several hours of dread worrying about the safety of his family and whether the vigilantes would locate him and lynch him, or at the least abuse him in some way.

The mob had every intention of wreaking more havoc with the Mormons and their possessions. After finishing with the printshop, they went north across the street to Sidney Gilbert’s store. Their intent was to demolish it as well, but after Gilbert pleaded for clemency and promised to close it, they stopped.[34] Vigilantes then went to the home of Bishop Edward Partridge, took him captive, and tarred and feathered him.[35] Alexander Majors reminded his readers many years later that “the people who were doing this were not what is termed ‘rabble’ of a community, but many among them were respectable citizens and law-abiding in every respect, but who actually thought they were doing God’s service to destroy, if possible, and obliterate Mormonism.”[36]

Watching the whole scene was a prominent Jackson County citizen who was the sitting lieutenant governor of Missouri, Lilburn W. Boggs. He exclaimed with satisfaction, “Mormons are the common enemies of mankind and ought to be destroyed” and “You know what our Jackson County boys can do, and you must leave the country.”[37]

The mob had become so frenzied that they seemed to lose all sense of respectability. They physically assaulted numerous Church members within these approximately two hours of rampaging.[38] The Mormon high priests later wrote in a report to the Missouri governor: “They caught other members of the church to serve them in like manner [with tarring and feathering], but they made their escape—With horrid yells and the most blasphemous epithets, they sought for other leading Elders, but found them not—It being late, they adjourned until the 23rd.”[39]

Aftermath of the Violence

Most of the galley sheets for the Book of Commandments were destroyed. But two girls from the Latter-day Saint Rollins family, Mary Elizabeth (fourteen) and Caroline (twelve), watched the mobbers carry out a pile of large sheets of printed paper. While the men’s backs were turned, the girls dashed to the paper and loaded up their arms. They fled their pursuers and made their way to the same abandoned log stable where Sally Phelps and her family were hiding. Sally took possession of the Book of Commandments sheets. Another man, John Taylor (not the same as the third LDS Church President), also retrieved some galleys and safely fled from the mob. William E. McLellin gathered a number of sheets blowing about in the streets. The heroic action of these individuals preserved exceptionally valuable historical documents. Enough sheets were preserved to later put together a few copies of the Book of Commandments.[40]

The next several hours and days were absolutely frightening for the Phelps family and all the Independence Mormons. The two Phelps boys were not found until late that Saturday evening when some Church members walked into the demolished Phelps home and found them uninjured under brick and debris. They had been unable to free themselves.[41]

Phelps later pathetically reflected, “After the mob had retired, and while evening was spreading her dark mantle over the scene, as if to hide it from the gaze of day, men, women, and children, who had been driven or frightened from their homes, by yells and threats, began to return from their hiding places in thickets, corn-fields, woods, and groves, and view with heavy hearts the scene of desolation and wo.” Phelps gave a theological interpretation to the tragedy: “While [the Saints] mourned over fallen man, they rejoiced with joy unspeakable that they were accounted worthy to suffer in the glorious cause of their Divine Master.” Regarding his own stewardship, he recorded, “There lay the printing office a heap of ruins; Elder Phelps’ furniture strewed over the garden as common plunder; the revelations, book works, papers, and press in the hands of the mob, as the booty of highway robbers.” In his righteous indignation, similar to the way he had once railed against the Freemasons, Phelps wrote, “The heart sickens at the recital, how much at the picture! More than once, those people, in this boasted land of liberty, were brought into jeopardy, and threatened with expulsion or death, because they desired to worship God according to the revelations of heaven, the constitution of their country, and the dictates of their own consciences. Oh, liberty, how art thou fallen! Alas, clergymen, where is your charity!”[42]

The mob mostly sought two other leading Church brethren, Oliver Cowdery and William E. McLellin, who luckily escaped into the woods. If Cowdery and McLellin had been apprehended, the finders would have been given a hefty eighty-dollar reward.[43] The committee of citizens agreed to meet again the next Tuesday morning. Nobody knew if the mob would strike again en masse. The Phelps family probably took up residence with one or more other Latter-day Saint families in Independence. This insecure and inconvenient setup would last clear through November for the Phelps family.

Early on Tuesday morning, July 23, the vigilantes again assembled at the courthouse square, fully armed and bearing a red flag, which the Mormons took as a “token of blood.”[44] They went straight to the home of Isaac Morley, took him into their custody, and proceeded one by one to round up each of the other high priests, including Phelps. The mob “told [the leaders] to bid their families farewell; as they would never see them again.” Under point of bayonet, the high priests were thrust into jail “amid the jeers and insults of the crowd . . . to be kept as hostages and for immolation, in case any of the mob should be killed while depredating upon the persons and property of the ‘Saints.’”[45]

At this point of great alarm, W. W. Phelps, Edward Partridge, John Corrill, Isaac Morley, and John Whitmer “offered to surrender up themselves as victims, if that would satisfy the fury of the mob; and purchase peace and security for their unoffending brethren, their helpless wives, and innocent children.” The only reply they received to this Christlike offer was “The Mormons must leave the county en masse or every man shall be put to death.”[46]

At this stage Phelps and the other leading high priests felt they had no choice but to acquiesce to the terrorism of the mob. They signed the prewritten treaty. This satisfied the vigilantes, and they quickly dispersed. The treaty called for Church leaders to move their families out of Jackson County by the first of next January, to influence half of the Mormon society to remove by the same date, and to ensure that all Mormons be gone from Jackson County by the next April 1. The Church leaders were to “advise and try all means in their power to stop any more of their sect from moving to this county.” John Corrill and Sidney Gilbert could remain as general agents to wind up the Church’s business. “The Star is not again to be published nor a press set up by any of the society in this county.” Bishop Partridge and Phelps would be allowed to come and go in Jackson County to finish their business, that is, if they got their families out of the county by January 1, 1834.[47]

At least the “treaty” afforded Phelps and these Mormon leaders some breathing space. In any event they thought that they would be able to breathe easier. They conferred with each other and decided to dispatch Oliver Cowdery to Kirtland, Ohio, as quickly as he could travel to confer with Joseph Smith and the Ohio high priests on what to do next.[48]

Communicating with Ohio

Oddly, on July 29, only nine days following the attack on the properties and persons of the Saints, Phelps and his associates received many documents from Joseph Smith and the brethren in Ohio.[49] Unfortunately, all the instructions were moot as far as their immediate implementation was concerned. The instructions pertained to building Zion physically. Phelps and the others undoubtedly sighed with considerable resignation when they read these significant and exciting plans but could not begin to implement them. Their lives, their families’ well-being, and their property were all in jeopardy of further depredations by angry Jackson County residents.

The documents, dated June 25, 1833, in Kirtland, contained an explanation of the “Plat of the City of Zion” and a description of “the House of the Lord, which is to be built first in Zion.” These detailed instructions, including a drawing of the plat and of the temple, called for a one-square-mile city divided evenly into squares, twenty-four sacred buildings to carry on the work of Zion, and a most sacred house that would be ornately constructed and adorned.[50]

In an accompanying letter, the presidency of the high priesthood—Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, and Frederick G. Williams—brought the Zion brethren up to date on news of the Church and the sacred translation projects engaged in by these Ohio brethren. They had a few things to say regarding printing assignments that would affect W. W. Phelps. They announced that Phelps would not print the “New Translation” (the inspired revision of the Bible known as the Joseph Smith Translation) after all. Joseph Smith would have to be personally present for that project. Joseph hinted that a press would be obtained in Ohio for that purpose. The Prophet instructed Phelps to distribute the Book of Commandments without worrying about getting the copies bound. “They will be sold well without binding, and there is no bookbinder to be had that we know of, nor are there materials to be had for binding, without keeping the books too long from circulation.” The Zion brethren probably wept bitter tears when they read these instructions, because nearly all potential copies of the Book of Commandments had already been destroyed by the mob. Regarding the newspaper, the presidency said, “We feel gratified with the way in which Brother William [W. Phelps] is conducting the Star at present, we hope he will seek to render it more and more interesting.”[51]

On the very day that these documents from Kirtland arrived in Independence, July 29, 1833, John Whitmer and W. W. Phelps wrote a report of the depredations that the Saints had just suffered in Zion. In his portion of the letter, Whitmer wrote, “Our daily cry to God is deliver thy people from the hand of our enemies send thy destroying angels, O God in the behalf of the people that Zion may be built up according to the plan of our Lord to his servants.” The “plan” refers to the plan for the city of Zion they had received that very morning in the mail from Kirtland.[52] Whitmer also included the text of the lengthy covenant entered into by approximately three hundred Jackson County citizens earlier in July that demanded that the Mormons leave Jackson County. He then added what he called the “memorandum of the agreement” that was signed under duress by many Church leaders on July 23, wherein they agreed that the Mormons would leave the county, some as early as the following January 1 and others the next spring.[53]

In the Phelps portion of this same letter, William inquired as to what should be done in the future regarding his destroyed printing establishment and also Gilbert’s store. He added this poignant observation: “I know from the experience I have had that it is a good thing to have our faith thoroughly tried. Zion must and will be pure.”[54]

As the terrors of July melted into the unsure peace of August, the Zion high priests, including Phelps, began meeting in council to decide further action. For one thing, they figured that the so-called treaty could not be valid because it had been forced upon them under duress. They eagerly awaited further words of counsel and comfort from Joseph Smith and the Ohio brethren.

In the September council meeting, Zion was divided into ten separate branches with ten high priests to “watch over” them. Phelps was still among the brethren presiding over all the Saints in Zion. The council also discussed whether or not Saints living in other parts of Missouri should be encouraged to come that fall to Jackson County or not. They came to no conclusion.[55]

Assessing Responsibility for the Terror

During these months in the aftermath of the press’s destruction, Phelps had a chance to assess the damage. Counting all that was demolished or stolen—including the printing press, the office, the house, the type, the paper, and the nearly completed Book of Commandments—Phelps concluded that the damages amounted to “near seven thousand [dollars].”[56] Oliver Cowdery reported that the destruction caused seven laborers to lose their jobs and three families to be “left destitute of the means of subsistence.”[57] One of these families would have included the Phelps family, which had already gone through so many periods of dislocation, privation, and consequent suffering.

How much was Phelps responsible for the Jackson County terror of 1833 and thus the failure of the Mormons to bring about Zion in that location? Two historians have suggested, “The church might have experienced greater success in Jackson County had Phelps been a more temperate editor. Efforts to put church beliefs into print did not make a good impression with the colony’s Jackson County neighbors, but rather provided a focus for intense animosity. It is significant the mob chose to move first on the press.”[58]

However, Phelps cannot be held any more responsible for the problems in Jackson County than approximately twenty-five other Mormons. The words and actions of Joseph Smith Jr., Sidney Rigdon, Oliver Cowdery, Edward Partridge, and William E. McLellin undoubtedly antagonized the white settlers. We can assume, knowing what we do about the lives and contributions of many other Mormon men, that they too could have incited the antagonism among their acquaintances and neighbors. These would have included David Whitmer, John Whitmer, John Corrill, Sidney Gilbert, Isaac Morley, Lyman Wight, Porter Rockwell, Parley P. Pratt, Thomas B. Marsh, Joseph Knight Sr., Newel Knight, Joseph Knight Jr., Hiram Page, Peter Whitmer Sr., Peter Whitmer Jr., Jacob Whitmer, Christian Whitmer, Simeon Carter, Charles Allen, Harvey Whitlock, Calvin Beebe, David Pettegrew, and Levi Jackman. Some Mormon women no doubt antagonized early settlers as well.

In no sense can the leading Jackson County citizens be exonerated from their unlawful vigilantism and mean-spirited exciting of riot and destruction of others’ property. These Missourians included Lilburn W. Boggs, Benton Pixley, Finis Ewing, Isaac McCoy, Samuel C. Owens, R. W. Cummins, Jones H. Flourney, Samuel D. Lucas, Thomas Pitcher, Samuel Weston, William Brown, Moses G. Wilson, Thomas Wilson, Lewis Franklin, Hugh Brazile, George Simpson, Gen Johnson, Richard Simpson, Dr. N. K. Olmstead, Colonel William Bowers, Russell Hicks, Harmon Gregg, and Samuel Bogard. Unquestionably, many women on both sides contributed to stirring up the conflict. There is plenty of blame to go around. Phelps should not shoulder all the responsibility.[59]

Phelps and Partridge, along with the other Zion high priests, assumed that a peaceful resolution to this conflict could be reached. For one thing, they felt that God would intervene in their behalf to punish their enemies and restore them to their New Jerusalem projects. For another, they believed they would soon receive divine direction given to Joseph Smith about what they should do. Tragically, however, the experiences of the summer were merely a foretaste of what would happen in the late fall.

Notes

[1] Alexander Majors, Seventy Years on the Frontier (New York: Rand, McNally, 1893), 44.

[2] Newel Knight’s journal, as published in Scraps of Biography, Faith-Promoting Series (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor Office, 1883), 76. This quotation is also found in MHC, vol. A-1, 319–20; HC, 1:372–73.

[3] HC, 1:373n1.

[4] Majors, Seventy Years on the Frontier, 45.

[5] As cited in T. Edgar Lyon, “Independence, Missouri, and the Mormons, 1827–1833,” BYU Studies 13, no. 1 (1972): 10–19.

[6] “Church History,” T&S 3, no. 10 (March 1, 1842): 708. This quotation comes from the “Wentworth Letter,” and, as discussed in chapter 23, Phelps likely wrote this historical portion of the letter.

[7] “The Indians,” EMS 1, no. 9 (February 1833): [7].

[8] “The Elders Stationed in Zion to the Churches Abroad, in Love, Greeting,” EMS 2, no. 14 (July 1833): 111.

[9] MHC, vol. A-1, 320; HC 1:372.

[10] “Beware of False Prophets,” EMS 2, no. 14 (July 1833): 105.

[11] McLellin reported all this in a journal that he edited after Joseph Smith’s death when he tried to win Mormons over to his cause. Ensign of Liberty 1 (January 1848): 61. McLellin’s labors in Jackson County at this time are reported in Jan Shipps and John W. Welch, eds., The Journals of William E. McLellin, 1831–1836 (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 1994), 307. Ronald E. Romig referred to this incident with further documentation in Eighth Witness: The Biography of John Whitmer (Independence, MO: John Whitmer Books, 2014), 209, 209n7.

[12] “The Book of John Whitmer,” in JSP, H2:52–54; HC, 1:374–76.

[13] “Free People of Color,” EMS 2, no. 14 (July 1833): 109.

[14] MHC, vol. A-1, 326; HC, 1:378–79.

[15] Emily Dow Partridge Smith Young, “What I Remember,” November 4, 1883, http://

[16] JSP, D3:148n422.

[17] “Jackson County,” MS D 6019, folder 7, CHL (hereafter “Phelps in Jackson County”).

[18] David Pettegrew, “A History of David Pettegrew,” in David Pettegrew, journal, 1840–1857, MS 22278, box 1, folder 1, 15, CHL.

[19] As cited in William Mulder and A. Russell Mortensen, Among the Mormons: Historic Accounts by Contemporary Observers (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1958), 77–80.

[20] “The Book of John Whitmer,” in JSP, H2:54–55; “To His Excellency, Daniel Dunklin, Governor of the State of Missouri,” EMS 2, no. 15 (December 1833): 114; JSP, H2:146.

[21] In 1840 Isaac Morley, one of the seven leading high priests, swore out a statement of grievance that would be forwarded to the United States federal government. He described the events of that day, including the meeting of the committee with the high priests. Morley’s grievance, along with all Mormon redress petitions, are found in MRP. The Morley document is found on pp. 499–501.

[22]“To His Excellency, Daniel Dunklin, Governor of the State of Missouri,” 114.

[23] Romig, Biography of John Whitmer, 212.

[24] MRP, 461.

[25] The Phelps family descendants have retained a story in their respective books of remembrance about the dastardly deed of sending Sally and her sick infant out of house and home. This is the source of the two boys being left behind in the house. Henry Enon Phelps often related this story to his posterity. W. W. Phelps, son of Henry Enon Phelps and a descendant of the original W. W. Phelps, recorded the story in December 1942 so that it could be placed in copies of the book of remembrance. A copy of the story is in my possession. For contemporary confirmation of the sick infant, see “To His Excellency, Daniel Dunklin, Governor of the State of Missouri,” 114; and “The Outrage in Jackson County, Missouri,” EMS 2, no. 18 (March 1834): 138.

[26] As cited in Pearl Wilcox, The Latter Day Saints on the Missouri Frontier (Independence, MO: n.p., 1972), 68.

[27] “The Book of John Whitmer,” in JSP, H2:55.

[28] Majors, Seventy Years on the Frontier, 45.

[29] Majors, Seventy Years on the Frontier, 45.

[30] See Edward Partridge, in JSP, H2:209; and for many others, MRP, 15, 64, 104, 396, 433, 461, 465, 499, 509, 517, 526, 565, 696.

[31] “William Phelps versus Lewis Franklin,” as cited in Romig, Eighth Witness, 211.

[32] JSP, H2:209; “The Outrage in Jackson County, Missouri,” 138.

[33] Ronald E. Romig and John H. Siebert obtained this information from various sources and reported it in “First Impressions: The Independence, Missouri, Printing Operation, 1832–33,” John Whitmer Historical Association Journal 10 (1990): 63, 63n77.

[34] JSP, H2:209.

[35] MRP, 512.

[36] Majors, Seventy Years on the Frontier, 46.

[37] As cited in Wilcox, Latter Day Saints on the Missouri Frontier, 71. See also MHC, vol. A-1, 328; HC, 1:391–92.

[38] See discussion of this in Ronald E. Romig, Early Independence, Missouri “Mormon” History Tour Guide (Independence, MO: Missouri Mormon Frontier Foundation, 1994), 34. See also Romig, Biography of John Whitmer, 213–19.

[39] “To His Excellency, Daniel Dunklin, Governor of the State of Missouri,” 114.

[40] Romig and Siebert, “Independence, Missouri, Printing Operation,” 63–64; Romig, Early Independence, Missouri “Mormon” History Tour Guide, 34; “Autobiography of Mary E. Lightner,” Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine, July 1926, 196.

[41] This story comes from Phelps family sources included in the family book of remembrance. Copy in my possession.

[42] MHC, vol. A-1, 329; HC, 1:393.

[43] Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 307.

[44] See the 1838 memorial to the Missouri legislature and the 1840 appeal to the United States Congress in MRP, 15, 104. See also JSP, H2:211.

[45] MRP, 104.

[46] MRP, 104–5. In their October 1833 letter to Missouri governor Daniel Dunklin, these brethren said they “offered themselves a ransom for the church, willing to be scourged or die, if that would appease their anger toward the church, but being assured by the mob that every man, woman, and child would be whipped or scourged until they were driven out of the county, as the mob declared.” See “To His Excellency, Daniel Dunklin, Governor of the State of Missouri,” 114.

[47] MHC, vol. A-1, 330; HC, 1:394–95. See also John Corrill, A Brief History of the Church of Christ of Latter Day Saints (St. Louis: Printed for the Author, 1839), in JSP, H2:147; and Edward Partridge’s account in JSP, H2:211.

[48] MHC, vol. A-1, 330; HC, 1:395.

[49] The date of July 29 is ascertained from a reference to the mail arriving that morning from Kirtland in a letter written back to Kirtland by Phelps on July 29. See JSP, D3:197.

[50] JSP, D3:121–46 contains this document along with its complete historical setting and significance.

[51] JSP, D3:147–58.

[52] JSP, D3:190.

[53] JSP, D3:190–95.

[54] JSP, D3:197.

[55] MB2, 36; FRW, 65, 67; MHC, vol. A-1, 345; HC, 1:409.

[56] “Phelps in Jackson County.” Broken as it was, the press was taken by the vigilantes. A firm in Liberty, Clay County, was allowed to take ownership. They refurbished the press and used it to publish the Missouri Enquirer in Liberty. See MHC, vol. A-1, 412; HC, 1:470.

[57] “To His Excellency, Daniel Dunklin, Governor of the State of Missouri,” 114.

[58] Romig and Siebert, “Independence, Missouri, Printing Operation, 1832–1833,” 66.

[59] I gathered the names mentioned in this paragraph from the numerous reports about the conflicts between the Mormons and the original Jackson County citizens. I have taken into account their leadership responsibilities and reputations in the community.