Martyrdom And Succession

Bruce A. Van Orden, "Martyrdom And Succession" in We'll Sing and We'll Shout: The Life and Times of W. W. Phelps (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 369–392.

During Joseph Smith’s presidency, from 1830 to 1844, the Latter-day Saints faced numerous crises. W. W. Phelps participated in significant ways in many of them, such as the Mormons being brutally driven from Jackson County in 1833, the “Great Apostasy of 1837–1839,” the Saints being forced to leave Missouri altogether in 1838 and 1839, the John C. Bennett apostasy and its aftermath, and the legal as well as illegal attempts to extradite Smith to Missouri. But no crisis matched the actual dual martyrdom of the Prophet Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum, the two highest officers in the church. How could this happen? Didn’t Phelps and most other Mormons believe that these two beloved leaders would live up to the second coming of the Savior himself? How could Phelps and the Saints move on without “Brother Joseph”? Who would be their new leader?

Phelps was as close to Joseph Smith as nearly anyone else at the time of the Prophet’s death. His emotions surely reached nearly their breaking point when his close friend and hero was murdered in cold blood. How could he cope? What would the Church of Christ do now?

The context of the times and the actual sequence of events from January to June 27, 1844, are significant. So, too, with the succession crisis that followed. Phelps was in the mix the entire way.

Contextual circumstances include the practice of plural marriage by Joseph Smith and a few other leaders; the falling away of William Law, second counselor to Joseph Smith in the First Presidency; Law’s creating a group opposed to Smith claiming he was a “fallen prophet”; the increasing frustration toward Mormons of both Whigs and Democrats in Illinois that was heightened by Joseph Smith’s campaign for the presidential chair; difficulties with Freemasons in Illinois; the rage of the Anti-Mormon Party that was centered in Warsaw, Carthage, and Green Plains in Hancock County, Illinois; and the absence of most of the Twelve Apostles at a crucial time. These events occurred during roughly the same time frame, but they must be considered individually to understand their cumulative causation of the assassination of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. W. W. Phelps, who was at Joseph’s side for several hours almost daily from January through June 1844, was intimately connected with each of these circumstances.

Plural Marriage and William Law

Joseph Smith’s introduction of the doctrine of “plurality of wives” and his extensive practice of the same incited anger against him. Phelps was well-informed about the doctrine of plural marriage before the Prophet’s death. He was present when Joseph Smith, visiting Indian lands with his entourage way back on July 17, 1831, first alluded to a future practice of polygamy.[1] Characteristically, Joseph would have informed Phelps of the “revelation” (now D&C 132) dictated on July 12, 1843.[2] Smith involved Phelps fully in all political discussions, in the Council of Fifty meetings involving the kingdom of God both spiritually and politically on the earth, with the temple-related endowment and being a member of the “Quorum of the Anointed”[3] (those individuals who received their endowment under the hand of the Prophet), and by sealing William and his wife Sally for eternity. The kingdom of God, the endowment, and sealing doctrines were inextricably connected to the Prophet’s teachings of plural marriage, considered “celestial marriage” at the time. However, Joseph Smith did not ask Phelps to enter plural marriage as Smith had asked a handful of other trusted associates directly.[4] Yet Brigham Young and the Twelve would later authorize Phelps to enter plural marriage before leaving Nauvoo.

Phelps was neck-deep in the “Nauvoo Expositor affair” that centered on problems some church members had with the doctrine of plurality of wives. The leader of the Nauvoo dissenters was William Law, a former member of the First Presidency.[5] (Other issues also eventually provoked the creation of the Nauvoo Expositor and its attacks on Joseph Smith.)

Becoming acquainted with William Law is necessary to this story. He was born in 1809 in Northern Ireland and immigrated to the United States in 1819 or 1820. William and his brother Wilson were accomplished millwrights. Possessing keen entrepreneurial minds, they were always on the lookout for land deals and community development opportunities. With his talents, William was drawn to the Toronto area of Upper Canada. William and his wife Jane were introduced to the restored gospel near Toronto. He served as a branch president and met Joseph Smith when the Prophet went to Canada as a missionary in 1837. Smith urged all Canadian converts to gather to church headquarters. Soon after leaving Canada, the Laws learned of the Saints’ expulsion from Missouri, so they tarried until traveling to the Mormons’ new home in Nauvoo in November 1839. Wilson accompanied William and Jane. The Laws’ talents were put to use in developing Nauvoo. William and Wilson proved loyal to Joseph Smith in both religious and secular ways. William Law, thirty-one years old, was called as Joseph Smith’s second counselor in the presidency in January 1841 when Hyrum Smith was elevated to associate president and patriarch to the church.[6] For his part, Wilson Law became a major general in the Nauvoo Legion.[7] Both became land developers and sawmill operators, among other business activities.

William and Wilson Law’s eventual dissent from the church was based on factors similar to those of other dissenters of that general period (dating back to Far West in 1837–1839). “These reasons essentially related to a growing ‘concentration of authority’ in the President of the Church and the extension of that authority into the areas of politics and economics.”[8] W. W. Phelps could scarcely have avoided noting similarities of his own fall in Far West to that of the Law brothers and others in Nauvoo in 1843–1844.

Law’s economic and political concerns were tragically compounded when Smith introduced him to plural marriage in the spring of 1843. The multiple interchanges between Smith and Law regarding polygamy as well as with Hyrum Smith, Emma Smith, Law’s wife Jane, and others are enormously complex.[9] Joseph Smith and William Law tragically broke up over these episodes. Subsequently, Law also became incensed when the Prophet introduced the doctrine of “plurality of Gods” and the unconditional sealing of individuals up to eternal life.[10]

During the final week of December 1843, Joseph Smith discussed with his closest advisers, including Phelps, that William Law had become a “Brutus” (a traitor) and that the police should keep a watch on what Law was up to, along with this brother and perhaps others. Smith told the new force of forty policemen: “I am exposed to far greater danger from traitors among ourselves than from enemies without, although my life has been sought for many years by the civil and military authorities, priests, and people of Missouri.”[11]

Discussions ensued in city council special sessions, with W. W. Phelps a main participant, where Law testily defended himself.[12] The final break between these two former close friends—Smith and Law—took place on January 8, 1844, in a heated argument on Water Street immediately in front of the Phelps home. Joseph Smith informed Law that he had been dropped from the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Anointed.[13]

Joseph Smith, Hyrum Smith, Sidney Rigdon, John M. Bernhisel, Almon Babbitt, W. W. Phelps, and many others strived to bring reconciliation with William and Wilson Law. But this came to no avail given the passions and hurt feelings of these strong-willed men. Both Law brothers became especially incensed when their personal stories of alleged marital infidelities came before discussions in private councils of church leaders.[14] Furthermore, they felt that their excommunication trials on April 18, 1844, were convened illegally.[15] They came to the conclusion that Joseph Smith was a “fallen prophet.” Along the way, William and Wilson Law gravitated to a group of prominent Nauvoo men who were of the same mind regarding what they considered Joseph Smith’s tyrannical leadership and who also were caught up with charges of sexual improprieties. Coincidentally, four of the leaders were two other pairs of brothers: Chauncey and Francis Higbee and Robert and Charles Foster. They formed a clique consisting of more than two hundred other dissenting but less well-known Mormons who were known as the “reform movement” or the “Reformers.” Two significant non-Mormons—Joseph H. Jackson, a businessman and an aide-de-camp to Joseph Smith in the Nauvoo Legion (but who also was engaged in a counterfeiting scheme and in an unholy quest to take Hyrum Smith’s daughter Lovina as a wife), and Sylvester Emmons, who had served on the Nauvoo City Council—joined them and ultimately participated in plots to eliminate or kill Joseph Smith.[16]

They established their own Reformed Mormon Church on April 28 at Wilson Law’s sawmill business. William Law was named president, and others were placed in a first presidency and quorum of apostles. They created a committee to visit the homes of Nauvoo residents to see who would be willing to join them.[17]

Nauvoo Expositor

Joseph Smith’s candidacy for president proceeded apace. However, he could not simply ignore challenges from within the church. This became especially obvious when on May 10, 1844, the “reformers” published a prospectus for a newspaper that they planned to call the Nauvoo Expositor. In the prospectus, the group proposed to expose the “UNION OF CHURCH AND STATE” in Nauvoo and the despicable acts of the “SELF-CONSTITUTED MONARCH.”[18]

A few days later in the pages of the Times and Seasons, Phelps sought to delimit the severity of the emergence of the reformers and of the Expositor. He said that “a few artless villains can always be found who are watching for [Joseph Smith’s] downfall or death.” Yet, Phelps asserted, the Lord will cause them “fall into their own pit.” Phelps was sure that their tale “will soon be forgotten.”[19]

However, Joseph Smith and his many advisers (Phelps included) grew increasingly wary of the threats of the Laws and their coconspirators. Smith gave a public sermon on Sunday, May 26, 1844, strongly outlining his feelings regarding these threats. He wanted all Latter-day Saints to know of the existence of this “new church” and new “holy prophet” (sarcastically referring to William Law) to help them avoid deception.[20] On June 4 Joseph met with W. W. Phelps and other advisers still in town about the possibility of prosecuting William and Wilson Law and Robert Foster for perjury and slander as it pertained to their false and malicious court testimonies a few days earlier in Carthage.[21] The brethren sought any possibility to forestall threats to life and limb and to the very continued safety of Nauvoo.

The first, and as it turned out, the only issue of the Nauvoo Expositor was printed on the dissidents’ new printing press and distributed on June 7. The publishers (in order of their listing) were William Law, Wilson Law, Charles Ivins, Francis M. Higbee, Chauncey L. Higbee, Robert D. Foster, and Charles A. Foster. Sylvester Emmons, the most literate among the “Reformers” and also trained as a barrister, was the editor and likely author of most of the articles. The paper’s stated purpose was to inform the public of the reason why this group had seceded from the “Latter Day Saint Church.” But, most of all, the sheet attacked Joseph Smith mercilessly for his “self-aggrandizement”; his complete political, military, and economic control over Nauvoo and church members; his “whoredoms” resulting from the “spiritual wife doctrine”; and his introduction of the doctrine of plurality of Gods. The Nauvoo Expositor slandered Joseph Smith and other leaders, claiming they purposely strived to seduce the many arriving young British women converts into licentiousness. The newspaper consisted of four pages (much like the Nauvoo Neighbor run by Phelps) and promised to publish weekly at least for a year.

In the “Preamble” of the issue, Emmons wrote that they were not going to forsake their God-given rights of freedom of speech and liberty of the press. He also realized that the publishers were “hazarding every earthly blessing, particularly property, and probably life itself, in striking this blow at tyranny and oppression.”[22]

The Expositor also attacked W. W. Phelps as a spokesman for Joseph Smith. They claimed that Phelps said that “Joe” was above the law. Emmons asserted that by voting for Smith, “you are voting for a man who contends all governments are to be put down and the one established upon its ruins. You are voting for an enemy to your government.”[23]

Joseph Smith and Phelps believed that the ongoing existence of the Expositor would lead to extreme violence against Mormons from within and without. It could become worse than Missouri!

As the furor surrounding the publication of the Nauvoo Expositor rapidly heated up throughout the city, Mayor Smith hastily called city council meetings to consider the cases of the Reformers and how to respond to the Expositor. W. W. Phelps, serving both as a city councilman and clerk of the mayor’s court, added numerous legal observations and personal opinions regarding the dangers posed by the dissidents.[24]

In the first of these meetings, on the day following the publication of the Expositor, the council lambasted members of the Law conspiracy for their impertinence and character flaws. They especially assailed Joseph Jackson for his threats to kill Joseph and Hyrum Smith. Council members wanted to gather evidence to justify their growing resistance to the newspaper’s existence. Phelps recommended that illegal alcohol distilleries in Nauvoo be raided in order to get offenders to testify against Law’s group. A motion also passed that the council prepare an ordinance to prevent a libelous publication from existing and “to prevent all conspiracy against the peace of the city.” Joseph Smith contended that the dissenters intended to whip up a “mob spirit.” Phelps, as was often the case, ended up authoring the proposed ordinance. He withdrew from the discussion temporarily, wrote the ordinance, returned, and read it to the council. Then Mayor Smith directed that a committee consisting of Phelps and two others edit and enhance the ordinance, especially with language to protect the Nauvoo Charter.[25] The Phelps-authored ordinance is yet another lengthy, pedantic piece on the many wrongs suffered by Latter-day Saints. Phelps connected heavenly mandates with state regulations.[26]

Two days later, in the morning of Monday, June 10, 1844, the council reconvened in an emergency session. Again, council members brought forward various new allegations against the Laws, the Higbees, the Fosters, and Emmons and Jackson, including gross immoralities and intention to commit murder. They exaggerated some of their assertions. Mayor Smith indicated he felt justified in identifying the Expositor as a “nuisance,” a term that had meaning in previous US legal cases. In the afternoon, the council passed the ordinance and then discussed means to put the Expositor out of business. W. W. Phelps had consulted legal references such as those by James Kent (Commentaries on America Law, four volumes), William Blackstone (Commentaries on the Laws of England, four volumes), the Illinois Constitution, and the Springfield Charter (a model used to create the Nauvoo Charter) and was prepared during the discussion to point out what he felt was legal and what was not. Hyrum Smith recommended that the best way to deal with this libelous “nuisance” was to smash the press to pieces and to “pie” (meaning to scatter or spill) the type. Benjamin Warrington recommended that the Nauvoo government not be too hasty in its decisions but rather fine the publishers three thousand dollars for libel. A heated discussion against the dissenters continued for several minutes. The turning point came when Phelps exclaimed he “felt deeper this day than he ever felt before” about putting an end to this press. He challenged the rest of the council to agree with him with a resounding “yes,” which they did. As justification, Phelps referred to the well-known noble actions at the “Boston Tea Party.” The council promptly voted to have the mayor take action to destroy the press of the Nauvoo Expositor.[27]

Mayor Smith “immediately ordered” the press destroyed by City Marshall John P. Greene and to be backed up as necessary by members of the Nauvoo Legion under the direction of Major General Jonathan Dunham. In the evening, Greene and his posse quickly destroyed the press, scattered the type, and burned copies of the paper. Forthwith Francis Higbee along with others of the Law clique threatened vengeance by “throwing down” Joseph Smith’s house and burning the church’s printing office (where Phelps worked).[28]

The city’s action of destroying a free press appeared to most outside observers as an unconstitutional act of the first order. This act prompted legal action against Joseph and Hyrum and all members of the city council, Phelps included.[29]

Perhaps Phelps would have thought back on the 1833 destruction of the church’s own printing shop in Independence, named W. W. Phelps & Co., by local political leaders even as he as a government official pushed for the destruction of the Expositor. (The irony is not lost on present-day observers.) Phelps defended the decision of the council in the Nauvoo Neighbor:

The church as a body and individually has suffered till “forbearance has ceased to be a virtue”: the cries and pleadings of men, women, and children with the authorities, were, will you suffer that servile murderous intended paper to go on and vilify and slander the innocent inhabitants of this city, and raise another mob to drive and plunder us again as they did in Missouri? Under these pressing cries . . . the city council of the city of Nauvoo on the 10th, inst., declared the establishment and Expositor a nuisance. . . .

And in the name of freemen, and in the name of God, we beseech all men who have the spirit of honor in them, to cease from persecuting us collectively or individually. Let us enjoy our religion, rights, and peace, like the rest of mankind: why start presses to destroy rights and privileges, and bring upon us mobs to plunder and murder?[30]

Political Opposition

Another attempt to destroy Joseph and Hyrum Smith came from politicians in Illinois, especially those of the Whig Party, but also some Democrats. The two parties, who were evenly divided at the time in Illinois, first sought Joseph Smith’s and the Mormons’ political favor from 1839 to 1843, but by 1844 both were severely opposed to Smith and the Saints.[31] “Latter-day Saints during the Nauvoo years held beliefs about government and politics defined by their own Anglo-American orientation and in even more significant ways by their religious worldview.” The Saints sought legitimate political protection and the right to live their own religion without violent opposition. Yet, “at the same time, their millennial orientation anticipated a future theocratic government following the Second Coming, and their experiences had taught them to distrust many elected and appointed officials.”[32] Unfortunately, nearly everything Smith and ghostwriter Phelps tried to do politically only got them in trouble with other Illinois citizens.

Joseph Smith and other church leaders sought help and protection from Illinois politicians. Simultaneously, the candidates for office also looked for Joseph Smith’s approval so they could gain political power and influence. Yet neither side satisfied the other, and everyone was disappointed.

The Whig Party in particular included many fierce opponents of the Mormons and used partisan newspapers such as the Alton Telegraph, the Quincy Whig, and Springfield’s Sangamo Journal to publish their vitriol. W. W. Phelps, presumably representing the church, beginning in 1843 often shot back at these Whig papers in kind through first The Wasp and then the Nauvoo Neighbor.[33]

The political and cultural spat between Whigs and Mormons developed into a deadly struggle. In 1843 most Illinois Whig leaders coalesced behind Henry Clay as the party’s presidential standard bearer in 1844. Various in-state and out-of-state Whigs sought Joseph Smith’s and the Mormons’ support for Clay. Their thinking was that Illinois could make the vital difference in the Electoral College to get Clay elected, and Mormon support would ensure that Clay would win Illinois. General Smith considered the possibility of supporting Clay for months, but in early 1844 he announced his own candidacy for the presidential chair and also sent a stinging letter (ghostwritten by Phelps) to Clay repudiating his political doctrines. This development totally infuriated the Illinois Whigs, who then proceeded to do everything they could to undermine Smith and the Mormons. Significantly, Abraham Jonas, a Whig Party operative, had provided the press that was used by the Mormon Reformers to publish the Nauvoo Expositor. Other well-known Illinois Whig Party bosses—John J. Hardin (a congressman), Thomas Gregg, and Oliver Hickman Browning—also contributed to the dangerously rising animosity against the Saints in Nauvoo and outlying areas.[34]

Animosity of Freemasons

This same Abraham Jonas was not only a Whig leader but also the first Grand Master of the Freemasons in Illinois. Back in 1842, Jonas was still striving to gain political capital from the Mormons in his quest to become a congressman. In late 1841, some Latter-day Saints including former Masons Hyrum Smith, John C. Bennett, James Adams, Heber C. Kimball, and George Miller thought that establishing a Masonic lodge was a good idea in order to increase tolerance with influential men in Illinois. Jonas endorsed the request of several Nauvoo men to create a temporary lodge in Nauvoo on October 15, 1841. Jonas officially established Nauvoo’s first Masonic lodge on March 15, 1842, and, in an unusual ploy, elevated Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon to “master Masons” on sight. (Joseph Smith played no direct role in Masonry after this, but he allowed Hyrum Smith to be the “Worshipful Master,” or lodge leader.) Nauvoo Masonic leaders quickly allowed scores of new petitioners to join the fraternity and went forward with plans to build a stately Masonic hall. By adding so many new members so quickly, the local Mormon Masonic lodge eventually lost its credibility.[35]

Jonas’s cozying up to the Mormons and the too-rapid growth of the fraternity in Nauvoo created heated feelings among other Illinois Masonic lodges. Eventually, Jonas was deposed as Grand Master, and the Mormon-dominated lodges were thrown into ill repute by other Illinois lodges. Numerous Masons in both Hancock and Adams Counties coalesced in their animosity toward Mormons resulting from all these missteps regarding Freemasonry. Many Masons may have been involved with the eventual plotting and carrying out of the murders of Joseph and Hyrum Smith.[36]

Was W. W. Phelps once again a Freemason in Nauvoo after once being an Anti-Mason? No extant records answer the question. A list of the first 155 inducted Masonic members in Nauvoo has been discovered. Phelps was not among that number. This same list indicated that 250 others signed the documents.[37] Historians Wicks and Foister claim that “almost every church leader was a Mason and nearly two-thirds of all Freemasons in Illinois were Latter-day Saints” and that Phelps was a Freemason.[38] Certainly Phelps became a major advocate of the emerging “temple endowment” that had striking similarities to Freemasonry rites. However, in his position as the de facto editor of the Nauvoo newspapers, he gave scant attention to the rise of Masonry in Nauvoo.

Anti-Mormon Party

Finally, the Anti-Mormon Party contributed significantly to the martyrdom story. This group was founded in the summer of 1841, but it gained new impetus after the August 1843 congressional election. Warsaw Signal editor Thomas C. Sharp and a few of his town’s allies worked indefatigably to create a large and widespread anti-Mormon organization. He and others set up numerous meetings in the county seat Carthage to solidify the membership and aims of this group. W. W. Phelps relished combatting Sharp and his party in the press. Beginning in October 1843, Phelps reported repeatedly on the actions of the “anties” in the Nauvoo Neighbor. At first Phelps spoke of the new party derisively, as if its objectives would quickly devolve into nothingness.[39] But as he realized that the anti-Mormons were increasing in number and influence, he was forced to deal with them more directly.

Church leaders learned in late December 1843 that Colonel Levi Williams (Illinois state militia officer from Green Plains, Hancock County) had organized a meeting of anti-Mormons in his community to go to war with arms against the Mormons.[40] Thereafter, Levi Williams was coleader with Thomas Sharp of Illinois anti-Mormons.

On January 10, 1844, after reporting that a handful of Nauvoo citizens were assaulted doing business in Carthage, Phelps scornfully wrote that although Anti-Mormon Party members did not believe they were “mobocrats,” they proved themselves such by these actions. If those actions were acceptable to common society, Phelps stated, “farewell to our republican institutions; farewell to law, equity, and justice; and farewell to all those sacred ties that bind men to their fellow men.”[41]

Two weeks later Phelps reported that the Anti-Mormon Party had expanded and boasted many members from Carthage, Warsaw, and Green Plains. He asserted that the party was much more interested in gaining political offices and influence than dedicating themselves to principle. Yet, he acknowledged, the falsehoods spread far and wide by this clique were having an adverse effect on the minds of Hancock citizens. It was a time of great alarm in the minds of many Nauvoo residents.[42]

The Anti-Mormon Party continued to beat the drums of war through the winter and into the spring and summer of 1844.[43] Sharp’s editorials in the Warsaw Signal and Levi Williams’s fiery rhetoric in caucus meetings spurred them on.[44] When the party learned of the Nauvoo Expositor’s destruction, they were ready to ally with the Mormon Reformers and also with the Whig Party operatives, of which Levi Williams was already a part. The three groups jointly sought to bring about legal justice to Joseph Smith and other church leaders. This fortified alliance also sought to ambush Joseph Smith somehow and kill him.

Complicating matters was the absence of ten members of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles, who had gone east on both political and church missions. Joseph Smith depended on them immensely, particularly Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball. These two were levelheaded, and the Saints had come to rely on their counsel and directions as they spoke in Sabbath meetings, visited branches away from Nauvoo, and distributed directives via the Times and Seasons. Now they were gone when Smith needed them desperately. John Taylor and Willard Richards (as well as Associate President Hyrum Smith) were still in town, and they were clearly utilized as these enormous challenges grew and nearly overwhelmed church members. W. W. Phelps and his family surely shuddered and prayed as these crises grew toward a climax.

Preparing for War

The immediate spark lighting the tinderbox leading to Joseph and Hyrum Smith’s assassination was the destruction of the Nauvoo Expositor press on June 10, 1844. Events in Nauvoo and western Illinois quickly spiraled into chaos, and the safety of Latter-day Saint leaders and of lay members alike suddenly was in jeopardy. Word of the press’s destruction spread quickly to other Hancock County towns. As one of Joseph’s chief advisers, Phelps again was involved with all actions taken by Smith leading to the Carthage Jail atrocity.

Indignation meetings led by the Anti-Mormon Party convened on June 11 in Carthage and Warsaw and decried the Mormons’ abrogating the constitutional guarantee of freedom of the press. Similar meetings, some extending into additional counties, took place in days that followed.[45] The Mormons’ decision to destroy the Nauvoo Expositor to waylay prejudice against Nauvoo and the Mormons had exactly the opposite effect. It soon became obvious that the Saints had lost nearly every friend among regular Illinois citizens. All hell had broken loose.

Thomas Sharp called for public outrage against the Mormons that could include violence: “War and extermination is inevitable! Citizens ARISE ONE and ALL!!! — Can you stand by, and suffer such INFERNAL DEVILS! To ROB men of their property and RIGHTS, without avenging them. We have no time for comment, every man will make his own. LET IT BE MAKE WITH POWDER AND BALL!!!”[46]

On June 12, Hancock County constable David Bettisworth arrested Joseph Smith in his office at 12:30 p.m. on charges of destroying property. The writ also called for the arrest of seventeen additional men, W. W. Phelps included, who were either on the city council or part of the posse that had destroyed the Expositor press.[47] Smith objected, indicating that his arrest was illegal, and proceeded to petition and then obtain a writ of habeas corpus from the Nauvoo Municipal Court for himself, thus allowing himself freedom to move about. The other men also received a similar writ the next day.[48] These actions provided only a mere respite.

On June 17, Phelps put out an “Extra” of the Nauvoo Neighbor that included a “Proclamation” from Mayor Smith ghostwritten by Phelps. They defended their actions to destroy the Nauvoo Expositor press, referring to it as a “public nuisance,” and cited Blackstone, the Illinois constitution, and the Nauvoo Charter for justification. In his typical way, Phelps lambasted the internal enemies of the church:

A short time since a press was started in this city which had for its object the destruction of the institutions of the city, both civil and religious: its proprietors are a set of unprincipled scoundrels who attempted in every possible way to defame the character of the most virtuous of our community, and change our peaceful and prosperous city into a place as evil and polluted as their own black hearts. To rid the city of a paper so filthy and pestilential as this, become the duty of every good citizen, who loves good order and morality; a complaint was made before the City Council, and after a full and impartial investigation it was voted—without one dissenting, a public NUISANCE, and to be immediately destroyed; the peace and happiness of the place demanded it, the virtue of our wives and daughters demanded it.[49]

Threats of violence against Nauvoo caused Mayor Joseph Smith to declare martial law on June 18. In full uniform, General Smith assembled the militia on the street in front of the Mansion House and prepared to address the people. First, he had W. W. Phelps read the Warsaw convention’s call for the extermination of church leaders and the driving of the Mormons from Illinois. Then, with his sword unsheathed, Smith expressed his love for the Saints and his determination to protect them, if even by the shedding of his own blood.[50]

Phelps continued to defend the Prophet and the people in the press. He produced another “Extra” for the Nauvoo Neighbor for Friday morning, June 21, in which he wrote three spirited articles. Responding to “preparations to an appeal to arms” by the anti-Mormons, Phelps wrote:

Internal War! Mobbing and bloodshed; and for what? any outrage upon the community, committed with impunity? No! no! verily no! But two Laws, two Fosters, and two Higbees, with a few other discontented spirits, wish to wreak vengeance on a whole community because forsooth, that community will not lie still and let them destroy them and their rights. Now really if the baser sort of men rush out in war, and murder men, women, and children, for the supposed wrongs of others, they must be thirsty for blood. Where is common sense? where is humanity, and where is the efficient arm of the government, to shield the oppressed from such a tornado of internal wrath and persecution?[51]

Events Leading to Carthage

Where was Governor Ford, he who alone was in a position to bring peace to western Illinois poised for a bloody civil war? He learned of the destruction of the Expositor in Springfield. He decided to go to Carthage and arrived there on June 21. He deployed various militia contingents throughout Hancock County to assure that all competing sides could be protected from each other as he sought for a peaceful resolution. He tended to agree with those who swarmed around him regarding the atrocities performed by the Mormons, particularly in denying freedom of the press. Ford wrote Joseph Smith demanding that he and other perpetrators submit themselves to stand trial in Carthage, and he promised to protect them in confinement.[52]

Joseph Smith met with numerous advisers, Phelps included, to plan what they could do. Certainly they didn’t trust the governor’s word. Reports flooded in regarding threats to Mormon villages in the countryside. Phelps, as clerk of the mayor’s court, recorded and certified many depositions of victimized Saints who fled to the city. Church leaders decided to firmly entrench in the city and protect themselves with armed sentries and pickets.[53]

The brethren concluded that Joseph and Hyrum Smith should flee to avoid a certain lynch mob. They could possibly arrange to go to Washington and appeal to President John Tyler. Joseph and Hyrum believed that Nauvoo would likely be safe in their absence. On the evening of June 22, the Prophet sent for W. W. Phelps and asked him to leave the next day for Cincinnati and prepare petitions to President Tyler and Congress. Phelps was also to consult with Emma Smith and Mary Fielding Smith about the possibility of their families accompanying Phelps to Cincinnati to meet up with Joseph and Hyrum.[54]

During the night, a couple of hours after midnight, on Sunday morning, the twenty-third, the Smith brothers arrived on the Iowa side of the river. Soon they learned that a posse sent by Governor Ford had arrived that morning in Nauvoo to arrest them. Many in Nauvoo feared for their safety because so many enemies were threatening to destroy the city. Responding to desperate pleas from his wife and others, as well as considering the will of God, Joseph Smith decided that he and Hyrum should return and submit to arrest, which they did that day.[55] Thus Phelps did not leave for Cincinnati, but rather he stayed as close as he could to his prophet-hero.

On Monday morning at 6:30, Joseph Smith and his enormous entourage gathered for their journey on horseback toward Carthage. All eighteen under indictment for “riot,” including Nauvoo councilor W. W. Phelps, were in this impressive group along with attorneys and witnesses. They paused to look out at the beautiful city that in so many ways had grown rapidly and had prospered. Smith remarked that the people did not realize the trials that awaited them.[56] These Mormon men proceeded to Carthage and spent the night there under the tenuous protection of Governor Ford’s guards.

Carthage was filled with dozens of nonresidents the next day, Tuesday, June 25, 1841. They included all the indicted Nauvoo officials and some Mormon friends who desired to protect their leaders. Naturally, most of the official accusers—the publishers of the Nauvoo Expositor—were ready to testify in court. Numerous Anti-Mormon Party members desired to see what would happen with Joseph Smith. Their leaders, particularly Thomas Sharp and Colonel Levi Williams, strategized how to isolate Smith in order to kill him as justified by “vigilante justice.” Neither the Mormons nor their enemies expected the judicial system to work in their favor. Governor Thomas Ford remained in Carthage hoping with the powers of his office to ensure a peaceful outcome.[57]

At a court hearing that day, all Nauvoo city councilmen were let free on bond until trial, which was scheduled for Saturday, just four days hence. Phelps and his associates had to post the high amount of $500.00 apiece backed up by their personal property. They left for Nauvoo that evening. However, Joseph and Hyrum Smith were held on new charges of “treason” based on statements that each had made before the Nauvoo Legion a few days earlier.[58]

Murder in Carthage and Its Aftermath

The next day most Mormon onlookers and sympathizers were hassled out of town. Even though Governor Ford promised protection, it was clear that most of the seventy militia members (from the local “Carthage Greys”) assigned to protect the Mormon prisoners were part of the Anti-Mormon faction. Joseph and Hyrum were kept in the stone county jail. John Taylor and Willard Richards of the Twelve, at the Prophet’s request, willingly stayed with the prisoners. Richards was also Joseph’s personal scribe and took dictation and closely recorded the hour-by-hour events that transpired.[59]

The day of the foul murders arrived on Thursday, June 27, 1844. At dawn W. W. Phelps entered Carthage Jail to briefly speak with the two Smiths, Taylor, and Richards. He was not allowed to stay and went home to Nauvoo.[60] The occupants in jail spent the long hours in decided melancholy and tried to gain strength from conversation, singing, and reading scriptures.

During the day, Governor Ford and his cohorts left for Nauvoo to calm the Mormons. En route they met up with various militia troops, which the governor disbanded. But under the direction of Sharp and Williams, about eighty Warsaw militia members unofficially made their way to Carthage with their murderous intentions. Along the way, the mob grew to about two hundred. With painted faces, they persuaded the Carthage Greys to move away and stormed the jail at about 5:00 p.m. with guns blazing. Hyrum tried to withstand the mob by holding fast the cell door. However, a musket ball entered through the door, striking Hyrum in the face, killing him instantly. Joseph then used his six-shooter to keep the mob at bay and spent his rounds. He went to the window and, raising his hand in the Masonic signal of distress, cried out, “O Lord, my God!” He was shot from both within and without the jail, causing him to fall to the ground dead. Richards protected the wounded Taylor from further attack and kept a record of what happened, including the death of the Smiths.[61]

Later that day, Willard Richards sent word to Phelps and others in Nauvoo that “Joseph and Hyrum are dead.” He urged Saints to turn totally away from violent vengeance, something that Carthage and Warsaw residents feared. The next day, the twenty-eighth, Richards arranged for the transport of the bodies of the two Smiths back to Nauvoo. Meanwhile, Phelps addressed the Nauvoo Legion at 10:00 a.m., urging them to be peaceful and to prepare to meet the group of men delivering the bodies of Joseph and Hyrum to Nauvoo later in the day. Phelps joined Richards, Joseph’s brother Samuel H. Smith, and numerous bodyguards in guiding the cortege from the temple to the Mansion House, generally recognized as church headquarters. More than a thousand people gathered in the street. Phelps was considered one of three temporary leaders of the church along with the two apostles, Richards and Taylor. The wounded Taylor was still in Carthage under care of his wife Leonora.[62]

At the Mansion House, Richards and Phelps addressed the Saints and emphasized the pledge made to Governor Ford that Mormons would allow the laws of the land to take their course. The congregated Saints sustained the brethren’s proposals and dispersed knowing that they could view the slain bodies in the Mansion House beginning the next day.[63] William and Sally Phelps along with their children were filled with despair and weeping.

Thousands passed by the bodies as they lay in state on Saturday, June 29, 1841. After the viewing concluded, a congregation gathered at the preaching “grove” near the temple for funeral services. W. W. Phelps was the designated speaker.[64] The fact that he had that honor and responsibility speaks to his position of leadership at this stage. Given the times and the strong emotions felt by Phelps and other Saints, as well as their love for their beloved prophet and patriarch, Phelps’s words rang sincere and truthful:

Two of the greatest and best men, who have lived on the earth, since the Jews crucified the Savior, have fallen victims to the popular will of mobocracy in this boasted “Asylum of the oppressed”—the only far famed realms of liberty—or freedom, on the globe; and the sword of justice, that ought to glitter with vengeance to repel such an insult to humanity—and the rich boon of life, and the free pursuit of happiness, hangs in the closet; and the stately robes of jud[g]ment that might clothe the sons of freemen with “brief” authority to wipe off the stain of innocent bloodshed by a philistine clergy and hypocritical people, from our national escut[c]heon, hangs there too; and there they will hang till Jehovah comes out [of] his hiding place and vexes the nations with a sore vexation.[65]

Phelps spent the rest of his funeral sermon extolling the virtues of Joseph Smith and emphasizing the restoration of the priesthood with all its keys and attendant blessings, powers, and ordinances. Phelps spoke to the revelatory truths taught by the Prophet over the preceding fifteen years.

In the aftermath of the murders, Phelps, with the permission of Elders Richards and Taylor, would take on a hefty role in leading the Saints through their grief and peaceful, nonretaliatory course. Using Richards’s accounts of the tragic events in Carthage, Phelps would oversee the preparation of a Nauvoo Neighbor “Extra” and report details of the assassinations.

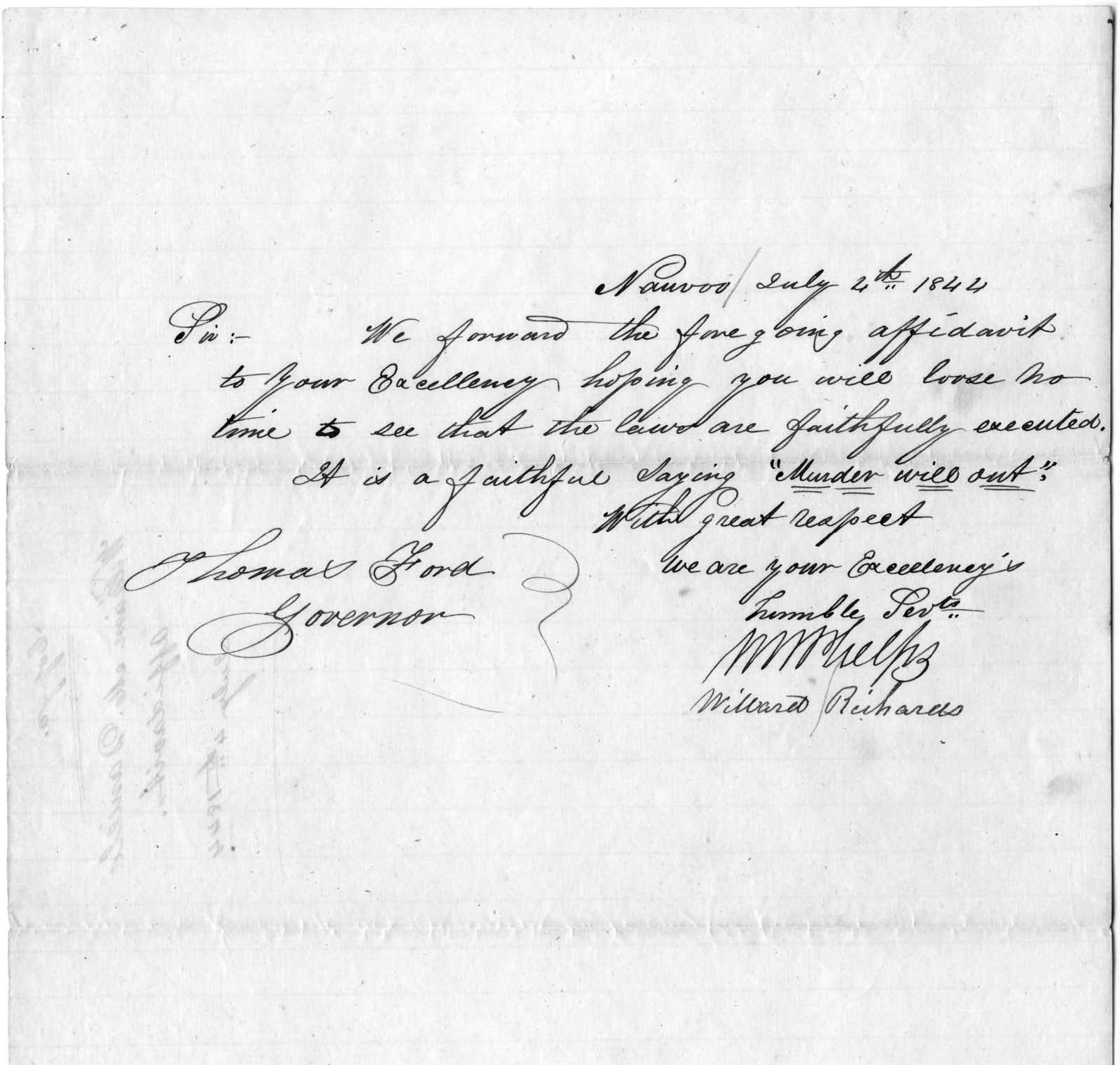

Letter from W. W. Phelps and Willard Richards to Governor Thomas Ford.

Letter from W. W. Phelps and Willard Richards to Governor Thomas Ford.

Phelps’s published that “Extra” on Sunday, June 30, and a special edition of the Times and Seasons a day later to report on the murders and events that led up to them. He published “Awful Assassination! The Pledged Faith of the State of Illinois Stained with Innocent Blood by a Mob!” Phelps drew on Willard Richards’s firsthand oral accounts to write his report of the tragic news. Using the word martyrs for the first time in referring to the slain Smith brothers, Phelps dramatically stated, “Thus perishes the hope of law; thus vanishes the plighted faith of the State; thus the blood of innocence stains the constituted authorities of the United States, and thus have two among the most noble martyrs since the slaughter of Abel, sealed the truth of their divine mission, by being shot by a Mob for their religion!”[66]

Phelps also published a “proclamation” that he had just received from Governor Ford. Ford urged all Illinois citizens to exercise restraint in their actions, to which Phelps sardonically responded: “We assure the Governor, if he can manage human butchers, he has nothing to fear from armless, timid, and law abiding Latter day Saints.”[67]

The three local leaders of the church wrote a letter of consolation to members of the church everywhere. It was in the names of W. W. Phelps, Willard Richards, and John Taylor (in that order). Phelps was the obvious author.

As has been the case in all ages, these saints have fallen martyrs for the truth’s sake, and their escape from the persecution of a wicked world, in blood to bliss, only strengthens our faith, and confirms our religion, as pure and holy. We, therefore, as servants of the Most High God, having the Bible, Book of Mormon and the book of Doctrine and Covenants; together with thousands of witnesses, for Jesus Christ; would beseech the Latter Day Saints in Nauvoo, and elsewhere, to hold fast to the faith that has been delivered to them in the last days, abiding in the perfect law of the gospel. Be peaceable, quiet citizens, doing the works of righteousness, and as soon as the “Twelve” and other authorities can assemble, or a majority of them, the onward course to the great gathering of Israel, and the final consummation of the dispensation of the fulness of times, will be pointed out.[68]

The Nauvoo City Council met to discuss matters of the community after the assassination of two of its leading lights. Willard Richards was present but essentially served as the recorder of the minutes. Naturally, John Taylor was not present. So it fell to Phelps to guide the meeting and determine the city council’s actions. He had already prepared a series of resolutions that he read and then moved that they be passed. They stated that Nauvoo citizens would “rigidly sustain” the laws and directions of Governor Ford, denounce any form of retribution for the assassinations of the Smiths, and appeal to the “majesty of the law” to bring the perpetrators to justice. Phelps called for a public meeting later in the day to allow all Nauvoo citizens to approve these resolutions.[69]

Together with Willard Richards and John P. Greene, Phelps on July 7 wrote a letter to the governor’s militia commander requesting that no troops be quartered in Nauvoo and that Robert Foster, known enemy to the church, be required to stay out of the city. Foster came to the city anyway and was protected from threatened retaliation.[70]

Phelps kept considerably busy throughout the month of July. He met in council with the other leaders and wrote to and received correspondence from Governor Ford. He also spoke in the city council, insisting that they keep the police force.[71] Almost single-handedly, he directed the printing and publishing efforts in the printing office. John Taylor was recuperating at home, and Wilford Woodruff was still on his mission in the East. Phelps wrote numerous articles for the Times and Seasons and the Neighbor. He also consulted with Willard Richards at first and then with John Taylor as well. William Clayton confided frustratingly in his journal in early July that Richards and Phelps were acting alone in making decisions in behalf of the church.[72] Parley P. Pratt was the first of the absent apostles to return to Nauvoo, on or about July 10.[73] With John Taylor’s gradual healing, four men (Pratt, Richards, Taylor, and Phelps) took the reins of church leadership until a majority of the Twelve were present, especially Brigham Young.[74]

Pratt, Richards, Taylor, and Phelps (in the order of their listing) wrote a letter entitled “To the Saints Abroad” with sage advice:

On hearing of the Martyrdom of our beloved prophet and patriarch, you will doubtless need a world of advice and comfort, and look for it from our hands. We would say, therefore, first of all, be still and know that the Lord is God; and that he will fulfill all things in his own due time; and not one jot or tittle of all his purposes and promises shall fail. Remember, REMEMBER that the priesthood, and the keys of power are held in eternity as well as in time; and, therefore, the servants of God who pass the veil of death are prepared to enter and more effectual[ly] work, in the speedy accomplishment of the restoration of all things spoken of by his holy prophets.[75]

One of Phelps’s major efforts was to call for the nation’s judicial system to bring the murderers of Joseph and Hyrum to justice. He wrote, “If one of these murderers, their abettors or accessories before or after the fact are suffered to cumber the earth, without being dealt with according to law, what is life worth, and what is the benefit of laws?”[76]

In the Nauvoo Neighbor, Phelps compared the contemporaneous mob action against the Irish in Philadelphia, which was engendering much national publicity, with the repeated persecution against the Mormons that he considered to be far worse. Using his own experiences, he stated,

Appalling as it is, we have to give more particulars of mobbery in the once goodly city of Loving brothers,—Philadelphia. Fourteen years experience in the horrors of persecution, mob violence, and the signs of the times,—which the junior Editor of this paper [reference to Phelps himself], has had in four states, has not left him destitute of feeling, reflection, hope, anticipation, or sorrow for a day of retribution,—of vengeance as whirlwind from the Almighty![77]

One of W. W. Phelps’s most important contributions at this time in behalf of the Saints was publishing a poem that he entitled “Joseph Smith” in the August 1, 1844, edition of the Times and Seasons. Phelps intended that these lines be sung to the tune “Star in the East.” This hymn, known now as “Praise to the Man,” has become one of the most widely appreciated and long-lasting contributions from W. W. Phelps to the church. Of significance is Phelps’s desire to blame Illinois mobsters and politicians for Joseph’s death: “Long shall his blood which was shed by assassins, / Stain Illinois, while the earth lauds his fame.”[78] The words “Stain Illinois” were changed in future LDS hymnals to read “Plead unto heav’n.”

In September, the Nauvoo printing office published the new edition of the Doctrine and Covenants that had been in the works for two years. Phelps had played a key role already in preparing the volume. A final statement entitled “Martyrdom of Joseph Smith and Hyrum Smith” was placed at the end of the new edition. That statement has since been canonized and now is Doctrine and Covenants 135. Phelps likely contributed to the wording of this statement. “Since at least the early 20th century, commentators and Church leaders had assumed that the statement was written by John Taylor, an Apostle and the head of the printing office. The section was never attributed to Taylor during his lifetime, however, and it may have been the work of Taylor, Richards, Phelps, or another regular contributor in the Nauvoo printing office.”[79]

Succession

Parley P. Pratt, John Taylor, Willard Richards, and W. W. Phelps were able to keep the Saints in Illinois in a peaceful state throughout July, but on August 3 Sidney Rigdon arrived from Pennsylvania and declared, based on recent alleged visions to himself, that he should be the successor to Joseph Smith. He received support from many Nauvoo leaders, particularly those who, like Rigdon, opposed Joseph Smith’s plural marriage doctrine. William Marks, Nauvoo stake president, agreed with Rigdon that a meeting should be held quickly to designate Rigdon as leader. Leading apostles, including Brigham Young, had not yet returned to Nauvoo. Rigdon and Marks knew that these men would oppose their action. Marks called for a meeting to settle the matter for Thursday, August 8.

W. W. Phelps and the others met with Rigdon on Tuesday, August 6, and charged him not to hold a meeting so quickly.[80] Later that evening, Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, Orson Pratt, Wilford Woodruff, and Lyman Wight of the Twelve arrived in Nauvoo. (George A. Smith had already arrived on July 28 and Amasa Lyman of the First Presidency on the thirty-first.) According to Woodruff, the Saints in Nauvoo were in “a deep gloom” and “feeling like sheep without a shepherd.”[81] Seeing circumstances as they were, Brigham Young, in a manner that befitted him, leaped into action. He convened an important meeting the next day with the Twelve, the first time they were together in “council” for many weeks.[82] Young was not going to allow Rigdon and Marks to get their way.

Both Brigham Young and Sidney Rigdon spoke in the Seventies Hall on Wednesday, the seventh. Rigdon spoke about visions he had received indicating that he was to be the designated “spokesman unto Joseph” and “guardian to the people” and that he would continue to build up the church to Joseph Smith. Young indicated that the Twelve had the keys to preside over the church and that God should manifest to the people who should lead.[83] Thus, the respective arguments as to who should succeed Joseph Smith were now clear—Sidney Rigdon as guardian or the Twelve Apostles under the leadership of their president, Brigham Young.[84]

The next morning, Sidney Rigdon appeared before the people in what was supposed to be only a “prayer meeting”[85] and spoke in random, incoherent terms for an hour and a half about his new divine assignment as guardian. Meanwhile, Brigham Young met with the Twelve on financial issues and, hearing of Rigdon’s speech and feeling the urgency of the moment, decided that the apostles needed to be part of the proceedings. Young made it to the assembly before Rigdon concluded. Young announced that all the Saints should reassemble at 2:00 p.m., when he and others would speak to the people.[86]

This date of August 8, 1844, goes down as one of the most impactful dates in all of Mormon history. W. W. Phelps would play a pivotal role. Hundreds of church members would remember the remarkable events and spiritual manifestations of that day. Before the meeting started, Brigham Young organized priesthood bearers according to quorums. Especially prominent were members of the Twelve who appeared ready to act in tandem.

W. W. Phelps offered the invocation. Brigham Young delivered one of his signal powerful addresses. He began by saying,

For the first time in my life, for the first time in your lives, for the first time in the kingdom of God in the 19th century, without a Prophet at our head, do I step forth to act in my calling in connection with the Quorum of the Twelve, as Apostles of Jesus Christ unto this generation—Apostles whom God has called by revelation through the Prophet Joseph, who are ordained and anointed to bear off the keys of the kingdom of God in all the world.

He asked for a vote if anyone in the congregation desired a “guardian” or “spokesman” to raise his hand. There were no hands. Young went on to declare powerfully that the Twelve held “the keys” of the priesthood and the kingdom of God and that Sidney Rigdon by himself most definitely did not.[87] A miracle that reportedly took place in the eyes of hundreds present indicated that the prophetic mantle had passed from Joseph Smith to Brigham Young.[88]

Sidney Rigdon wanted time to rebut, but according to the record “he could not speak.” He asked W. W. Phelps to speak in his behalf, hoping that Phelps would agree with his assertions.[89] Phelps’s address ended up being the second most important speech of that day because his opinions meant much to those who knew how close he’d been to Joseph Smith. Phelps rejected Rigdon outright and sustained the Twelve as having the keys to proceed forward:

With the knowledge that I have I cannot suppose but that this congregation will act aright this day. I believe enough has been said to prepare the minds of the people to act.

I have known many of them for 14 years, and I have always known them to submit with deference to the authorities of the church. I have seen the elders of Israel and the people—take their lives in their hands and go without purse or scrip in winter and in summer. I have seen them prepare for war, and ready to pour out their hearts’ blood, and that is an evidence that they will walk by counsel.

I am happy to see this little lake of faces, and to see the same spirit and disposition manifested here today, as it was the day after the bloody tragedy, when Joseph and Hyrum Smith were brought home dead to this city. Then you submitted to the law’s slow delay, and handed the matter over to God; and I see the same thing today—you are now determined as one man to sustain the authorities of the church, and I am happy that the men who were on Joseph’s right and left hand submit themselves to the authority of the priesthood. . . .

There is a combination of persons in this city who are in continual intercourse with William and Wilson Law, who are at the bottom of the matter to destroy all that stand for Joseph, and there are persons now in this city who are only wanting power to murder all the persons that still hold on to Joseph; but let us go ahead and build up the Temple, and then you will be endowed. When the Temple is completed all the honorable mothers in Israel will be endowed, as well as the elders.

If you want to do right, uphold the Twelve. If they die, I am willing to die with them; but do your duty and you will be endowed. I will sustain the Twelve as long as I have breath.

When Joseph was going away he said he was going to die, and I said I was willing to die with him; but as I am now alive, as a lawyer in Israel,[90] I am determined to live.

I want you all to recollect that Joseph and Hyrum have only been removed from the earth, and they now counsel and converse with the Gods beyond the reach of powder and ball. . . .

I want to say that Brother Joseph came and enlightened me two days after he was buried. He came the same as when he was alive, and in a moment appeared to me in his own house. He said, “Tell the drivers to drive on.” I asked if the building was on wheels? He said, “certainly”. I spoke, and away it went. We drove all round the hills and valleys. He then told the drivers to drive on over the river into Iowa. I told him Devil Creek was before us. He said, “Drive over Devil Creek; I don’t care for Devil Creek or any other creek;” and we did so. Then I awoke.[91]

From that day, August 8, 1844, the Twelve with Brigham Young at their head proceeded quickly and efficiently to guide the church in finishing the work revealed to Joseph Smith.[92] Succession in the presidency was not completely solved in August. Soon other “claimants to the throne” appeared and made their case. Phelps would prove to be exceptionally reliable and useful in helping the Twelve with their appointed tasks.

Notes

[1] See W. W. Phelps, letter to Brigham Young (both in Salt Lake City, Utah), August 12, 1861, CHL; JSP, D2:11n45.

[2] William Clayton, who recorded the revelation, wrote in his diary that the revelation was read to “several authorities during the day.” Phelps was a regular participant in Joseph Smith’s councils and could have been in attendance. See “Revelation, 12 July 1843 [D&C 132],” on the JSP website: http://

[3] Devery S. Anderson and Gary James Bergera, eds., Joseph Smith’s Quorum of the Anointed 1842–1845: A Documentary History (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2005).

[4] The thirty men known to have entered plural marriage before the death of Joseph Smith are listed in Gary James Bergera, “The Earliest Eternal Sealings for Civilly Married Couples,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 35, no. 3 (Fall 2002): 49. Phelps is not in that number.

[5] Biographical information, along with a thorough discussion of Law’s apostasy, is found in Lyndon W. Cook, “William Law, Nauvoo Dissenter,” BYU Studies 22, no. 1 (Winter 1982): 37–72; and Lyndon W. Cook, William Law (Orem, UT: Grandin, 1994).

[6] Cook, William Law, 4; D&C 124:91.

[7] JSP, J3:422, 474, 474n1.

[8] Cook, William Law, 4–5; Cook, “William Law, Nauvoo Dissenter,” 49.

[9] Discussion of these issues are found in Cook, William Law, 21–27; JSP, J3:159n707, 163n726, 207n907, 232n1037; JSP, CFM:64, 64n161, 191–92, 192n596.

[10] Cook, “William Law, Nauvoo Dissenter,” 56–67.

[11] JSP, J3:153n689; MHC, vol. E-1, 1836; HC, 6:152.

[12] John S. Dinger, ed., The Nauvoo City and High Council Minutes (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2011), December 29, 1843, January 3, 1844, January 5, 1844, 195–204; JSP, J3:153n689, 157n701; HC 6:149–53, 162–65; WWJ, 2:338; Cook, William Law, 38–46.

[13] Cook, William Law, 46–47; JSP, J3:xxiii–xxiv, xxiii n48, 158n705, 159, 159n707, 163n726; MHC, vol. E-1, 1857; HC, 6:171; Anderson and Bergera, Joseph Smith’s Quorum of the Anointed, 51–52.

[14] See JSP, J3:xxiii n48, 158n703, 232n1037 and JSP, CFM:64–65, 64n161, 65n162, 62n163, 152, 152n465, 154, 154n376, 192n597 for a discussion of these allegations and efforts to bring the Laws back.

[15] Only portions of the council proceedings that excommunicated William and Wilson Law, Jane Law (William’s wife), and some of their compatriots are recorded in Joseph Smith’s journal and in the official history. The council was presided over by Brigham Young and attended by members of the Twelve Apostles, some members of the Nauvoo Stake High Council, and several other high priests, including W. W. Phelps. JSP, J3:231–32, 232n1037; MHC, vol. E-1, 2022; HC, 6:341. For William Law’s diary entries concerning his excommunication, see Cook, William Law, 50–52.

[16] MHC, vol. E-1, 1936–37; HC, 6:272, 367; Dinger, Nauvoo City and High Council Minutes, June 8, 1844, 241–43, 241n77, 241n78; WWJ, 2:368; JSP, J3:207, 207n907, 232n1037, 234, 234n1048.

[17] JSP, J3:239, 239n1074; MHC, vol. E-1, 2026; HC, 6:346–47.

[18] The complete Nauvoo Expositor, including the prospectus, is available digitally online at https://

[19] T&S 5 (May 15, 1844): 535.

[20] JSP, J3:262, 262n117; MHC, vol. F-1, 48–49; HC, 6:408–12.

[21] JSP, J3:271, 271n1236; MHC, vol. F-1, 69–70; HC, 6:427.

[22] “Preamble,” Nauvoo Expositor 1 (June 7, 1844): 1.

[23] “Citizens of Hancock County,” Nauvoo Expositor 1 (June 7, 1844): 3; emphasis in original.

[24] Dinger, Nauvoo City and High Council Minutes, June 8, 1844, June 10, 1844, 238–50.

[25] JSP, J3:274–76, 274n1250, n1251, n1252, and n1253. See also n. 24 above.

[26] Dinger, Nauvoo City and High Council Minutes, June 8, 1844, June 10, 1844, 249–66; JSP, J3:276, 276n1256. Significant portions of the ordinance were entered into the official history. MHC, vol. F-1, 74–75; HC, 6:433–34.

[27] Dinger, Nauvoo City and High Council Minutes, June 10, 1844, 250–66; JSP, J3:276, 276n1257 and n1258; MHC, vol. F-1, 78–85; HC, 6:432–45; JSP, CFM:193–94, 194n604.

[28] JSP, J3:276–77, 277n1259, n1260, and n1261; Dinger, Nauvoo City and High Council Minutes, June 11, 1844, 266–67; MHC, vol. F-1, 85–86; HC, 6:432.

[29] For a thorough discussion of the legal ramifications of the destruction of the paper and the press, see Dallin H. Oaks, “The Suppression of the Nauvoo Expositor,” Utah Law Review 9, no. 4 (1964–65): 862–903.

[30] “Retributive Justice,” NN 2 (June 12, 1844): 2; emphasis in original.

[31] The web of deceit of many Illinois and national politicians and parties is discussed at length in Wicks and Foister, Junius and Joseph. The entire theme of this book centers on the political struggles between the Mormons and politicians. See also Glen M. Leonard, Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, A People of Promise (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2002), 289–300.

[32] Leonard, Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, 269–70.

[33] “Mormonism and the Editor of the Alton Telegraph,” The Wasp 1 (January 28, 1843): 2; The Wasp 1 (September 27, 1843): 2; “For the Quincy (Ill.) Herald” (letter to the editor of that paper written under the pseudonym “A Friend to the Mormons”), NN 1 (March 20, 1844): 3.

[34] Wicks and Foister, Junius and Joseph, 6–7, 29–25, 115–16.

[35] Leonard, Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, 313–21; Wicks and Foister, Junius and Joseph, 250–55; Mervin B. Hogan, Founding Minutes of Nauvoo Lodge, U.D. (n.p., n.d.), 1–32.

[36] See Wicks and Foister, Junius and Joseph, 250–55, 285–87.

[37] Hogan, Founding Minutes of Nauvoo Lodge, 11–32.

[38] Wicks and Foister, Junius and Joseph, 250, 289. The authors provide no source for their statement that Phelps was a Freemason.

[39] “The ‘Warsaw Message,’ and the Carthagenians,” NN 1 (October 4, 1843): 3.

[40] MHC, vol. E-1, 1831; HC, 6:145.

[41] “Disgraceful Affair at Carthage,” NN 1 (January 10, 1844): 2.

[42] “Carthage, Warsaw, and Green Plains,” NN 1 (January 24, 1844): 2.

[43] Leonard, Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, 304–7.

[44] Their most frequently stated political objective was to bring about a repeal to the Nauvoo Charter. A long list of Anti-Mormon Party participants and some biographical information on each is found in Wicks and Foister, Junius and Joseph, 290–92.

[45] MHC, vol. F-1, 86–87, 94–95; HC, 6:451–52, 461–64; Leonard, Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, 368–69.

[46] “The Time is Come!,” Warsaw Signal, Extra (June 11, 1844): 1. Capital letters in the original.

[47] Some believed that William Law and Robert Foster provided Hancock County officials with the information to arrest Joseph Smith and the others.

[48] MHC, vol. F-1, 87–91, 93; HC, 6:453–58, 460; JSP, CFM:194–95, 195n612, 195n613.

[49] Joseph Smith [W. W. Phelps], “Proclamation,” Nauvoo Neighbor, Extra (June 17, 1844).

[50] MHC, vol. F-1, 117–19; HC, 6: 497–500; Leonard, Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, 369–70; JSP, CFM:196, 196n618.

[51] “The Preparation,” Nauvoo Neighbor, Extra (June 21, 1844).

[52] JSP, CFM:196–97, 196n621; Leonard, Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, 372–73.

[53] MHC, vol. F-1, 132–37; HC, 6:528–39.

[54] Leonard, Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, 374–75; HC, 6:547.

[55] JSP, CFM:197–98, 198n626, 198n627; Leonard, Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, 375–76.

[56] MHC, vol. F-1, 151; HC, 6:554.

[57] JSP, CFM:199, 199n629; Leonard, Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, 381–83.

[58] Leonard, Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, 383.

[59] JSP, J3:311–23.

[60] JSP, J3:323.

[61] Leonard, Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, 387–98.

[62] T&S 2 (July 1, 1844): 561; Leonard, Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, 398–401.

[63] JSP, CFM:204, 204n645.

[64] On June 13, 1855, W. W. Phelps read the funeral sermon that he purportedly gave at the grove on June 29, 1844. It is lengthy, being twenty pages in handwritten text, and expressed in Phelps’s ponderous style. Phelps stated that it was a copy of the original sermon. The transcript of the sermon along with commentary is found in Richard Van Wagoner and Steven C. Walker, “The Joseph/

[65] Van Wagoner and Walker, “The Joseph/

[66] “Awful Assassination! The Pledged Faith of the State of Illinois Stained with Innocent Blood by a Mob!,” published in both the Nauvoo Neighbor (June 30, 1844) and T&S 5 (July 1, 1844): 560; emphasis in original.

[67] Nauvoo Neighbor, Extra (June 30, 1844); emphasis in original.

[68] “To the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints,” T&S 5 (July 1, 1844): 568. This message was reprinted in The Prophet, the church’s newspaper in New York City. “To the Saints Abroad,” The Prophet 1 (August 17, 1844): 3.

[69] Dinger, Nauvoo City and High Council Minutes, July 1–2, 1844, 271–78.

[70] MHC, vol. F-1, 255–56; HC, 7:169. Sally Phelps assisted a group of Nauvoo women in visiting Foster and insisting that he leave Nauvoo. MHC, vol. F-1, 261; HC, 7:176.

[71] MHC, vol. F-1, 276–78, 280–81, 285; HC, 7:200–201, 207–8, 212; Dinger, Nauvoo City and High Council Minutes, 281.

[72] William Clayton, Journal, July 6, 12, and 15, 1844, CHL.

[73] William Clayton, Journal, July 14, 1844; MHC, vol. F-1, 261; HC, 7:175.

[74] MHC, vol. F-1, 276, 278; HC, 7:200, 202.

[75] “To the Saints Abroad,” T&S 5 (July 15, 1844): 586.

[76] “The Murder,” T&S 5 (July 15, 1844): 585–86.

[77] “Mob! Mob!! Mob!!!,” NN 2 (July 24, 1844): 2; “Philadelphia Mob,” NN 2 (July 24, 1844): 2.

[78] “Joseph Smith,” T&S 5 (August 1, 1844): 607. The poem was reprinted in The Prophet 1 (September 21, 1844): 3. The tune “Star in the East” did not remain the music for this hymn, although various choruses have performed “Praise to the Man” with the original tune. See http://

[79] Jeffrey Mahas, “Remembering the Martyrdom: D&C 135,” an article in Revelations in Context, an online aid to Doctrine and Covenants study produced by the Church History Library (CHL) of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 2016. https://

[80] William Clayton, Journal, August 4 and 6, 1844.

[81] WWJ, 2:434, August 6 and 7, 1844; MHC, vol. F-1, 295; HC, 7:228–29.

[82] WWJ, 2:434, August 7, 1844; MHC, vol. F-1, 295; HC, 7:228–29.

[83] MHC, vol. F-1, 295–96; HC, 7:229–30; William Clayton, Journal, August 7, 1844.

[84] Andrew F. Ehat posited that the Twelve were in a position to succeed Joseph Smith because “they constituted the priesthood quorum Joseph Smith designated to be stewards of his temple revelations.” Andrew F. Ehat, “Joseph Smith’s Introduction of Temple Ordinances and the 1844 Mormon Succession Question” (unpublished master’s thesis, Brigham Young University), 1.

[85] JSP, CFM, 207.

[86] MHC, vol. F-1, 296; HC, 7:231; William Clayton, Journal, August 8, 1844.

[87] MHC, vol. F-1, 297–300; HC, 7:232–35; “Special Meeting,” T&S 5 (September 2, 1844): 637–38. Young’s insistence that the Twelve Apostles had received the priesthood keys to bear off the kingdom of God had merit. He and the other apostles were together in council the previous spring, likely on March 26, when Joseph Smith passed on the keys and gave them what has come to be known as the “last charge.” JSP, CFM:62–63, 62n149, 63n151, 66, 66n164.

[88] While Brigham was speaking, many testified that they beheld the transfigured personage of Joseph Smith and heard the voice of the Prophet speaking to them. See Lynne Watkins Jorgensen, “The Mantle of the Prophet Joseph Passes to Brother Brigham: One Hundred Twenty-nine Testimonies of a Collective Spiritual Witness,” in Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestations, ed. John W. Welch (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2005), 373–490.

[89] MHC, vol. F-1, 300; HC, 7:236–37.

[90] Phelps here referred to the blessing and assignment given him from Joseph Smith to be a “lawyer in Israel.” See JSP, D4:435–36; JSP, J3:172n770.

[91] MHC, vol. F-1, 300–301; HC, 7:237–38; emphasis added. For Phelps’s earliest version of his speech on August 8, 1844, see “Special Meeting,” T&S 5 (September 2, 1844): 638.

[92] A significant piece on the succession of Brigham Young and the Twelve Apostles is Ronald K. Esplin, “Joseph, Brigham and the Twelve: A Succession of Continuity,” BYU Studies 21, no. 3 (1981): 1–40.