Preface

The Man, The Church, and Seeking Zion

Bruce A. Van Orden, "The Man, The Church, And Seeking Zion," in We'll Sing and We'll Shout: The Life and Times of W. W. Phelps (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), xxi–xxvii.

On an early summer day in 1831, William W. Phelps, together with his family, approached Joseph Smith’s residence, the Isaac Morley farm just east of Kirtland, Ohio. Joseph was known as “the Prophet” or “the Seer” to Mormons, a group that had organized a little over a year earlier in upstate New York. Smith had met this prominent newspaper editor in New York, but it was a surprise that Phelps showed up at this time. The Prophet was bustling about on this fourteenth of June, excited to leave later in the week for Missouri with other Church leaders in quest for the location of Zion and the New Jerusalem.

Thirty-nine-year-old W. W. Phelps had just resigned his editorship of the Anti-Masonic Ontario Phoenix newspaper in Canandaigua, New York. He announced to Joseph Smith that he had come with his family to Kirtland “to do the will of the Lord.”[1] The Prophet, as he had done for many other men, sought God in prayer in William’s behalf and returned with a revelation. “Thou art called and chosen,” the revelation stated. It charged Phelps to be baptized and ordained an elder straightaway by Joseph Smith. Phelps learned from this revelation that he was expected to join Smith’s group that very week and go to Missouri, where he would receive his “inheritance” to carry forth the work of Zion.[2]

Who was W. W. Phelps? What attracted this well-known newspaperman to a new and apparently fanatical religious group? What would he contribute to Mormonism? One thing for certain, as soon as he joined “The Church of Christ,” the original name of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, he became part of Joseph Smith’s inner circle. Even after two years of “apostasy” from the Church (1838–1840), Phelps reconnected with Joseph Smith in an exceptionally significant way. From 1831, when Phelps became a Mormon, to 1844, when Smith was slain, Phelps could be considered among the ten most influential men in Mormonism. And nothing was closer to the heart of these two friends than the quest to establish Zion in preparation for the Second Coming of the Lord Jesus Christ.

And who is Joseph Smith Jr., the founder of Mormonism? In the spring of 1820 in Manchester, New York, young Joseph sought divine guidance. He stated that the Father and the Son appeared to him, comforted him, and instructed him to join none of the churches, for their doctrines were corrupted. In time, Joseph learned, he would obtain additional instructions in building the kingdom of God.

Meanwhile, young Joseph Smith went about his normal pursuits of helping to clear and cultivate his father’s land. He also frequently took on day-labor jobs to help his family’s financial situation. He waited patiently for further divine guidance. On September 21, 1823, he felt inspired to fervently seek God in prayer again, and he was rewarded with a visitation from a heavenly messenger.

From 1823 to 1827 Joseph received annual visits from an angel named Moroni, who introduced the young prophet to a set of golden plates that lay hidden in a drumlin (a long oval mound formed of glacial drift) near the Smith farm. The plates, Joseph learned from Moroni, contained a religious record of a fallen people that once had inhabited the Western Hemisphere. The angel instructed Joseph to prepare himself so he could be entrusted to receive the plates and translate them with the aid of divine interpreters. Once he received the plates, Smith began translating them “by the gift and power of God” (Book of Mormon title page). The product became known as the Book of Mormon and was published in March 1830. This Book of Mormon would have an outsized impact on W. W. Phelps for the rest of his life.

Enormous controversy, however, followed Joseph Smith and his family during the 1820s. He was also known for his dabbling in folk magic and seeking for buried treasure. His reputation in the vicinity of his home plummeted as the public heard of his work with the “Gold Bible.”

In October 1827, just a month after Joseph Smith obtained the plates from the angel, Phelps went to Trumansburg, New York, about halfway between Cortland and Manchester, to edit a new anti-Masonic newspaper, the Lake Light. The next April he went to Canandaigua to edit a more prominent paper, the Ontario Phoenix. Canandaigua, the first, largest, and most energetic village in western New York at that time, was merely twelve miles from Palmyra, where the Book of Mormon was published. Phelps was among the first to obtain a copy and read it. The Book of Mormon and revelations to the Prophet Joseph Smith all became inextricably linked thereafter to the life and works of W. W. Phelps.

Phelps may have been prominent, but he was also eccentric. Everywhere he went people considered him somewhat strange. Some even believed him to be downright fanatical. He plainly was a zealot in whatever cause that captured his attention. Phelps helped found one of the most zealous of frontier political/

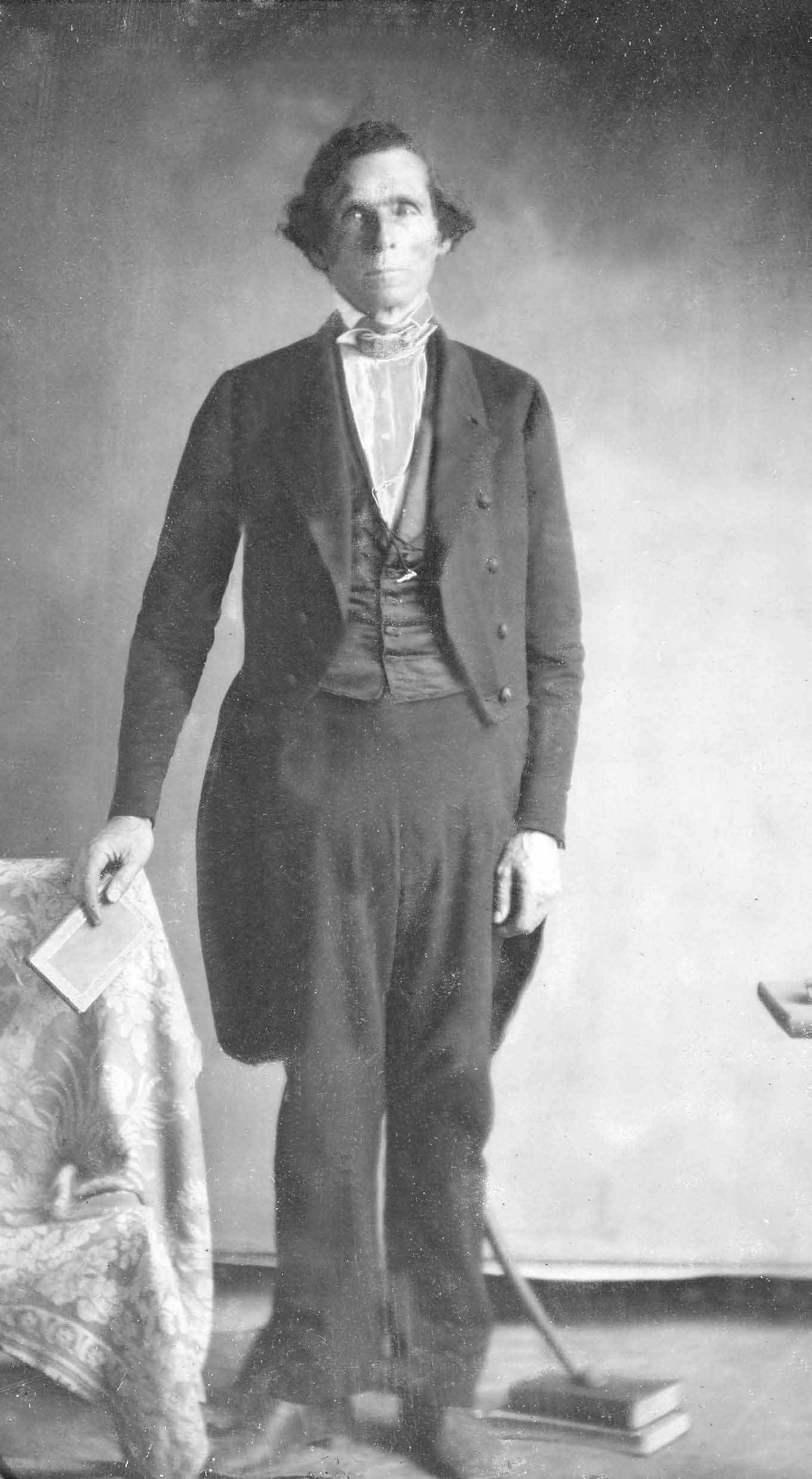

Thin and gangly, Phelps once wrote his wife that he had regained his normal heft of 135 pounds. He was about five feet, eleven inches, which would have been tall for that time. He also wore spectacles and appeared at all times to be studious and seriously caught up in his thoughts.

Phelps was also officious. He took pride in his rhetorical skills and knowledge of ancient languages. His writing was usually pedantic and verbose. He forever carried about a notebook in which he would compose a rhyme, couplet, or entire poem. Most of his poetry was moralistic. So, too, was his erudite prose. Throughout his life, he sought to excel and gain honor. Occasionally he could be downright egocentric.

Yet Phelps, a sincerely devout man, sought to do God’s will. Early in his life he was spiritually inclined and read the holy scriptures at his mother’s knee. He professed absolute fealty to his Savior Jesus Christ and often extolled the Lord in verse and prose. He may have struggled with pride, but he also desired to be humble and receive God’s approbation. Singing hymns was his favorite means of praising God. He held family devotionals morning and evening in which he led his family in reading the Bible (and, later, Latter-day Saint scriptures) and in singing hymns suitable for each occasion.

William had decided against joining any single church. His parents and family in Cortland County, as well as his wife Sally, had been partial to the Baptists. He occasionally went with her to the large Baptist congregation in Canandaigua. No doubt he vigorously joined in the singing, for in singing hymns he knew he was praising God and strengthening his faith. He personally did not join a church at that time, but he was a believer in Christ, especially in the resurrection and the imminent Second Coming. He was a “seeker,” one who sought the same church organization and gifts of the Spirit that existed in the original Christian church.

Once he reached adulthood, Phelps always referred to himself as “W. W. Phelps” in his newspaper mastheads, business and professional titles, and signatures. Joseph Smith called him William, but it is likely that most acquaintances, and certainly his wife at times, referred to him informally as “W. W.,” though his brothers and sisters called him William.

W. W. Phelps’s signature from 1863.

W. W. Phelps’s signature from 1863.

Phelps was an ardent family man, seemingly having inherited this trait from his Puritan background. His letters to his sweetheart Sally, his occasional sentimental musings in his newspaper columns, and his poetry on home and family betray deep emotional attachments to hearth and home. Precisely like his Puritan forebears, he considered his role as husband in family matters superior to Sally’s role as wife. Often he either cajoled or outright chastised her for perceived improprieties. He insisted on her loyalty and frequent expressions of devotion and affection for him. He was stern in disciplining his children, yet kind and loving toward them. He desired that his family members be proper in all their behavioral traits. When Phelps joined the Mormon Church in 1831, he and Sally had six children, four daughters and two sons. Another daughter had died in infancy. They would yet have three additional children.

W. W. Phelps as an editor in Salt Lake City, ca. 1853.

W. W. Phelps as an editor in Salt Lake City, ca. 1853.

W. W. Phelps was also a patriot and politician. Numerous veterans of the Revolutionary and Indian Wars dot his family tree on his father’s and mother’s sides as well as in Sally’s family. Repeatedly, Phelps wrote of precious liberties won by American blood. He attributed the rise of the American nation to the hand of God and felt that God would bless America only if her inhabitants kept the Lord’s commandments and eschewed evil. Combining his religious, superstitious, sentimental, and patriotic instincts, Phelps latched on early to the fast-rising Anti-Masonic movement as it started in western New York in 1826. He played a significant role in the new political party, and he sought its nomination as lieutenant governor in party caucuses in 1828, although he failed in the attempt.

Thus when Phelps came to Ohio and was baptized on June 16, 1831, he was a natural to assume several roles in the infant Church of Christ. He and the former restorationist preacher Sidney Rigdon, both distinguished in their respective professional lives, were the two most prominent and educated men to join the Church at that time. It was obvious to Joseph Smith that Phelps’s printing, writing, and newspaper editing talents could be put to immediate use in the Church. Joseph’s assignments to Phelps always pertained to the establishment of Zion.

In his early ministry Joseph Smith Jr. generally chose as his closest associates older men than himself, such as Phelps. The only men near his age whom he deeply trusted were his brother Hyrum, Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, and John Whitmer. In 1831, when Phelps joined the Church, the Prophet was still only twenty-five years old and many of his chief advisers were men substantially older than himself: Joseph Smith Sr. (sixty), Martin Harris (forty-eight), Sidney Rigdon (thirty-eight), Edward Partridge (thirty-eight), Newel K. Whitney (thirty-six), A. Sidney Gilbert (forty-one), Joseph Coe (forty-five), Frederick G. Williams (forty-three), and W. W. Phelps (thirty-nine).

The Church had grown from six official members in Fayette, New York,[3] on April 6, 1830, to little over a hundred in three separate branches by the fall of that year. In October four missionaries led by Oliver Cowdery headed west toward Missouri to teach Native American Indians (or “Lamanites” as they were called in the Book of Mormon and Doctrine and Covenants). En route they stopped in northeastern Ohio and introduced the gospel message to Sidney Rigdon, former friend and ministerial associate of missionary Parley P. Pratt. Not only did Rigdon embrace the new faith, but so too did many of his Reformed Baptist parishioners. Within three weeks, nearly 150 Ohioans were Mormons. This new development doubled the Church’s membership at once. Upon hearing of this singular achievement, Joseph Smith dispatched John Whitmer to Kirtland, Ohio, to preside over the new flock. In January 1831 the Prophet received revelation instructing him and the New York Saints to gather to Ohio and a new Church headquarters. By late spring of that year, just before Phelps came to join the movement, the combined gathering of New Yorkers and other converts and vigorous proselytizing had swelled the Church’s rolls to over 1,000. Phelps was well aware of the move to Ohio by all the New York migrants.

W. W. Phelps and Mormonism were made for each other. Only a few Latter-day Saints in the 1830s had greater impact upon the rise of the Church, both ecclesiastically and doctrinally. In the early 1840s he served his prophet-hero Joseph Smith as scribe, legal assistant, and ghostwriter. He was one among at least a dozen who were part of Joseph’s scribal culture from 1831 to 1844. Following the Prophet’s death in 1844, Phelps assisted the Twelve Apostles as an important aide. In the 1850s and into the 1860s, he remained a stalwart Saint and esteemed elder statesman.

Phelps truly cherished the revelations of God. He revered Joseph Smith for receiving scores of revelations and providing the world with pure and transparent truths. He was present when some of those revelations were received, and he served as scribe for some of Smith’s most significant prophetic and translation work.

As the Church’s first printer and editor, Phelps delivered the word of the Lord to the Saints as no other early member could. He assisted with the editing of the manuscript revelation books that were used to produce the first edition of the Doctrine and Covenants (1835). He was editor or assistant editor of eight early Church newspapers: The Evening and the Morning Star, the Upper Missouri Advertiser, the Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate, the Northern Times, the Times and Seasons, The Wasp, the Nauvoo Neighbor, and the Deseret News. He also compiled and published thirteen editions of the Deseret Almanac in Utah.

Phelps wrote dozens of hymns for the early Church, although only about twelve are still sung. Yet no hymn writer in the Church’s history is more deservedly remembered than this man who wrote such favorites as “The Spirit of God,” “Now Let Us Rejoice,” “Redeemer of Israel,” “Praise to the Man,” and “If You Could Hie to Kolob.” His hymn writing became his greatest legacy.

All in all, this interesting and somewhat strange man impacted the young Church in many vital ways. Furthermore, Phelps’s ardent quest for Zion remains today a significant feature of the restored gospel and Church.

Notes

[1] JSP, D1:336–37, 337n499; MHC, vol. A-1, 124; HC, 1:184; PJS, 1:355.

[2] See D&C 55:1–5. The manuscript copy of this revelation is published in JSP, MRB:154–55. A discussion of D&C 55 is found in JSP, D1:336–39.

[3] H. Michael Marquardt has argued that the actual organizational meeting for the Church took place in Joseph Smith Sr.’s log home in Manchester, New York. See H. Michael Marquardt and Wesley P. Walters, Inventing Mormonism: Tradition and the Historical Record (Salt Lake City: Smith Research Associates, 1994), 154–72. In April 1833 W. W. Phelps wrote, “Soon after the book of Mormon came forth, containing the fulness of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the church was organized on the sixth of April, in Manchester; soon after, a branch was established in Fayette” (“Rise and Progress in the Church of Christ,” EMS 1 [April 1833]: 4). In the Book of Commandments in 1833, Phelps identified Manchester as the location for the meeting on April 6, 1830, and for the revelation now known as D&C 21. The so-called Wentworth Letter, published under the title “Church History” in Nauvoo (T&S 3, March 1, 1842, 708), indicated that the Church was organized in Manchester. I assert that Phelps had a hand in writing that document. See JSP, R2:57 and JSP, D1:128–29, 129n95 for a discussion of this issue and the conclusion that the actual site for the organizational meeting was in Fayette. A version of “Church History” was added to by Phelps and was published as “Latter Day Saints” in 1844. This history also identifies Manchester as the site of the Church’s organization. See JSP, H1:502–16, especially p. 510.