Hell To Pay In Missouri

Bruce A. Van Orden, "Hell To Pay In Missouri" in We'll Sing and We'll Shout: The Life and Times of W. W. Phelps (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 273–294.

William W. Phelps was obviously a talented individual. Well organized, he helped create a coordinated structure for many projects since becoming an adult. His mind was quick. His knowledge of the printing trade, history, geography, politics, languages, and various sciences was far ahead of nearly all his peers wherever he had lived—Cortland, Trumansburgh, and Canandaigua, New York; Kirtland, Ohio; and Independence, Liberty, and Far West, Missouri. He had obvious writing and rhetorical skills. Phelps was always a fervent proponent as well as defender of whatever cause he embraced, whether it be a social-political movement or Mormonism. He was respected for his zeal and talents. However, his officiousness and occasional stubbornness and arrogance brought him into conflict with some individuals. He had always been rather unwise in making financial decisions. Phelps was undercut in his role as an Anti-Masonic politician and newspaper editor in western New York. He was mocked relentlessly by his opponents. When he joined the Latter-day Saints, some fellow journalists mocked him all the more.

In the spring of 1838, certain rivals in the Mormon movement had succeeded in undermining Phelps. Thomas Marsh and David Patten of the Twelve Apostles and at least two Missouri high councilors—John Murdock and George Hinkle—created church tribunals of questionable legitimacy to bring Phelps and other once-beloved leaders to the dust. His own financial actions had legitimized their antagonism toward him. Phelps’s emotions were ripe for his mind and heart to be poisoned by Oliver Cowdery, his dear friend, when Cowdery came to Far West in the fall of 1837. Stubbornness and arrogance helped bring Phelps low in the spring of 1838.

Previous Warm Relationship with Joseph Smith

One thing is certain about W. W. Phelps: his role in the Restoration and building up of the church was inexorably connected with Mormonism’s founder, Joseph Smith Jr. Phelps and Smith truly loved each other. Phelps had even written much poetry for the first hymnal that spoke either directly about Joseph Smith or about the newly revealed truths to the Prophet.

So what happened with the relationship between Joseph Smith and W. W. Phelps? That it became frayed there can be no doubt. The complete answer can be understood only by looking at the context and the times. Joseph Smith went through immense difficulties during the late 1830s, a most challenging period. The Prophet came to believe that opponents within the Mormon community had to be purged to keep the church pure. It also appears that Smith came to believe Thomas Marsh’s reports about Phelps’s alleged disloyalty and did not take an opportunity himself to check directly with Phelps.

The years 1837, 1838, and 1839 proved to be years of great distress for Joseph Smith and all Latter-day Saints. Thousands of members, perhaps as many as a third of the total, left the church during these years, never to return. Chaos reigned and persecution heightened during these years. The fact that the church even survived and would move forward in spite of its trials should be considered a miracle.

It was still an infant church, especially when considering the many decades that have passed since the 1830s. Young men led the emerging movement. When Phelps was cut off from the church in March 1838, Joseph Smith was still only thirty-two years old. Nearly all the men whom Phelps knew intimately from the council of the presidents, the Twelve Apostles, the Missouri bishopric, and the Missouri high council were younger than Phelps, who was forty-six at the time. Many were in their twenties or thirties. The only leading brethren older than Phelps were Joseph Smith Sr., Martin Harris, John Smith, Frederick G. Williams, Lyman Wight, and Isaac Morley. These many leaders, younger or older, often made grievous mistakes owing to their inexperience, personality traits, and mere humanity. Not one of the leading brethren, Joseph Smith Jr. included, remained exempt from making serious errors in judgment and behavior.

After W. W. Phelps was cut off from the church in March 1838, he disappeared for a few months from official church records. Phelps and the other so-called “dissidents” or “dissenters”—Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, John Whitmer, Frederick G. Williams, and Lyman Johnson—did not attempt to be in touch with Joseph Smith or Sidney Rigdon upon their arrival in Far West.[1]

Spring 1838

After Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon conducted general conference sessions in Far West from April 6 to 8, they turned their attention to bringing charges against Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, and Lyman Johnson (a member of the Twelve). According to revealed procedure,[2] Cowdery and Whitmer needed to be tried in a “common council” presided over by the bishop (Edward Partridge in this case).

Oliver Cowdery’s trial took place on April 12 and David Whitmer’s on April 13. Lyman Johnson of the Twelve was also tried on the thirteenth. All three were summarily “cut off” from the church. As it pertains to the Far West apostasy, the three were accused of bringing “vexatious lawsuits” against Mormons in good standing and scheming against the leaders of the church and blaspheming their names. (Interestingly, the charge against Cowdery for selling lands in Jackson County was dropped; nor had this charge been used to cut off W. W. Phelps and John Whitmer the previous month.)[3]

With some prompting from trusted advisers, Joseph Smith decided to avoid further internal dissension and persecution by cleansing the church from apostasy.[4] At this point, the church seemed to be rid of W. W. Phelps and his friends. However, excommunicating these men would not have a salutary effect on the church, but rather a negative one, at least throughout 1838 and the first half of 1839. “These excommunications did not restore harmony to the community. . . . [The dissenters] increased their verbal attacks upon the leading officials of the church. In addition, they pressed even more energetically the ‘vexatious lawsuits’ instituted against their former friends.”[5]

How engaged was W. W. Phelps in the spring of 1838 with the other “dissenters”? His feelings were torn. He was loyal to Oliver Cowdery and John Whitmer on the one hand, and he loved Joseph Smith on the other. What was Phelps to do? With whom would he ally? Or could he remain neutral? How would his family fare in such uncomfortable circumstances?

Private meetings of dissenters attended by Phelps went forward in which they plotted what they might do. These critics continued to live in Far West. They watched carefully what the church leadership was doing. John Corrill reported, “The dissenters kept up a kind of secret opposition to the presidency and church. They would occasionally speak against them, influence the minds of the members against them, and occasionally correspond with their enemies abroad.”[6]

On the other side, Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon of the First Presidency, their clerk Ebenezer Robinson, the Prophet’s scribe George W. Robinson, and the “temporary” presidency of the Missouri Stake—Thomas Marsh, David Patten, and recently appointed Brigham Young—convened in council about how to deal with the rift in the community. John Corrill explained that when Smith and the others realized that “the old strife kept up,” something had to be done with the dissenters who continued to harass them with “vexatious lawsuits” and other “ill treatment.”[7]

W. W. Phelps reported about this council meeting as well. In his November 1838 testimony, Phelps related: “As early as April last, at a meeting in Far West of eight or twelve persons, Mr. Rigdon arose, and made an address to them, in which he spoke of having borne persecutions, and law-suits, and other privations, and did not intend to bear them any longer, that they meant to resist the law.” Phelps also testified that Joseph Smith backed up Rigdon’s statement at this meeting.[8]

Even in the midst of these knotty problems, the leading brethren strived spiritually to look to the future. In April Joseph Smith sought and received revelations that pertained to responsibilities of the First Presidency and the Twelve. The most significant of these (D&C 115) was received on April 26, “making known the will of God, concerning the building up of this place [Caldwell County] and of the Lord’s house.” Yes, a temple was to be built! W. W. Phelps, when he learned of this revelation, may have pondered that he had envisioned a House of God at the very location that was now given to Joseph Smith in revelation. The revelation identified Far West as “a holy and consecrated land” unto God.[9]

Joseph Smith became particularly interested in writing his and the church’s official history in 1838. On April 9, Smith and Rigdon wrote a letter to John Whitmer, who for more than six years had been the official church historian, asking him to hand over his writings. They sarcastically noted his “incompetency as a historian.” If he refused to hand over the book, they had materials to write another, and that they would proceed forthwith to write a new history.[10] Sure enough, Joseph Smith started dictating his history on April 27.[11] This effort, inauspiciously begun, would later turn into the multivolume History of the Church. After he would return to the church in Nauvoo, W. W. Phelps would help compile, compose, and publish this history.

Joseph Smith was eager to fulfill revelation (D&C 115:18) “that other places should be appointed for stakes in the regions round about.” Most favorable sites in Caldwell County were already settled by the Saints. Joseph and his leadership council knew that many members who were still faithful to him would soon arrive in Missouri. Hence, on Friday, May 18, 1838, Joseph Smith, along with Sidney Rigdon, Thomas Marsh, David Patten, Bishop Edward Partridge, and “many others, left Far West to visit the north countries for the purpose of laying off a stake of Zion; making locations and laying claims for the gathering of the saints, for the benefit of the poor, and for the upbuilding of the Church of God.”[12]

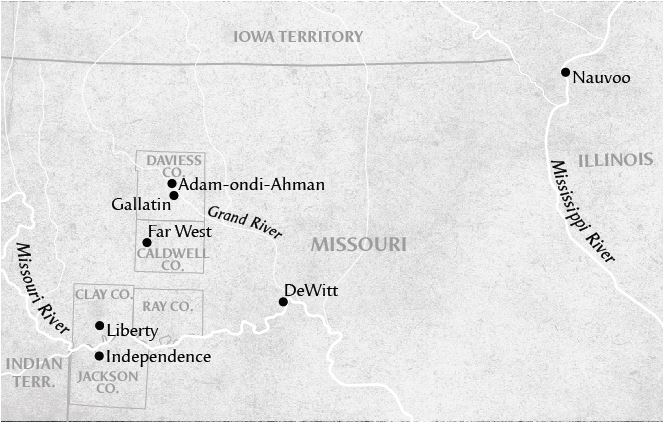

This two-week reconnaissance turned out to be fruitful, or at least it appeared to be so at the time. Prominent Mormon high priest Lyman Wight had moved to Daviess County a year earlier and set up a ferry on the navigable Grand River. Wight’s home served as headquarters for the exploration. On May 19 they identified a beautiful hill that they designated Spring Hill. It was revealed to Joseph Smith that day that the hill “is named by the Lord Adam-ondi-Ahman, because, said he, it is the place where Adam shall come to visit his people, or the Ancient of Days shall sit, as spoken of by Daniel the Prophet.”[13] Adam-ondi-Ahman was a term known to the Saints already (D&C 107:53); W. W. Phelps had even written a hymn about it that was sung at the Kirtland Temple dedication and by the Saints often in their meetings.[14] The brethren ended up surveying town lots in the area of Adam-ondi-Ahman for immediate settlement. Soon they arranged with the federal land office to gain “preemption rights” to that vicinity.

Settlement began in June in “Diahman,” as they affectionately called the community, and increased dramatically throughout July. According to one historian, “The clearest justification for Mormon removal from Missouri [in 1838–1839] was their expansion into counties outside the borders of Caldwell.”[15] Phelps would have significant experiences in Diahman, Daviess County, during the Missouri Mormon War later in 1838.

Meanwhile, throughout the month of May and into the first half of June 1838, even before Joseph Smith and others went to the north, the issue of dealing with the dissidents, Phelps included, rose to the surface. On May 6, a Sunday, Joseph Smith spoke to the Saints. He warned against listening to men who went throughout the community whining about their money problems and pointing out that they had suffered so much in helping the church. The Prophet indicated that these men were throwing out “insinuations” to “destroy the character” of the First Presidency.[16] Phelps was one of these men.

While Joseph Smith and others were exploring Daviess County and identifying a gathering spot at Diahman, the dissenters interacted unharmoniously with those professing loyalty to the First Presidency. In a contemporary account, John Corrill explained, “The church, it was said, would never become pure unless these dissenters were routed from among them. Moreover, if they were suffered to remain, they would destroy the church. Secret meetings were held, and plans contrived, how to get rid of them.”[17]

Effects of the “Salt Sermon”

The controversy exploded openly in a public meeting on Sunday, June 17, 1838. According to Corrill: “President Rigden delivered from the pulpit what I call the salt sermon; ‘If the salt have lost its savour, it is thenceforth good for nothing, but to be cast out and trodden under the feet of men,’ was his text.”[18] Everyone in the audience knew that this was an open threat to the dissenters. And since the First Presidency had emphasized obedience to God’s will, most members believed that drastic action should be taken. According to another Mormon contemporary, Reed Peck, “Joseph Smith in a Short speech Sanctioned what had been Said by Rigdon though said he I don’t want the brethren to act unlawfully but will tell them one thing . . . having created a great excitement and prepared the people to execute anything that should be proposed.”[19]

The next day, eighty-three Mormon men signed a multipage printed resolution ordering the dissenters to leave the county at once. They distributed the petition widely. Work on the document had started weeks earlier. Most observers concluded that Sidney Rigdon was the author because Rigdon had so openly threatened the dissenters the day before. Evidence also shows that Sampson Avard, a Mormon firebrand, also had something to do with its composition. Avard claimed that Rigdon drafted the document.[20] The document was specifically directed to “Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, John Whitmer, William W. Phelps, and Lyman Johnson.”[21]

Following are informative highlights from this threatening removal petition:

Whereas the citizens of Caldwell county have borne with the abuse received from you at different times, and on different occasions, until it is no longer to be endured; neither will they endure it any longer, having exhausted all the patience they have, and conceive that to bear any longer is a vice instead of a virtue.

We have borne long, and suffered incredibly; but we will neither bear nor suffer any longer. . . . There are no threats from you—no fear of losing our lives by you, or by any thing you can say or do, will restrain us; for out of the county you shall go, and no power shall save you. And you shall have three days after you receive this communication to you, including twenty-four hours in each day, for you to depart with your families peaceably . . . but in that time, if you do not depart, we will use the means in our power to cause you to depart. . . .

After Oliver Cowdery had been taken by a state warrant for stealing, and the stolen property found in the house of William W. Phelps; in which nefarious transaction John Whitmer had also participated, Oliver Cowdery stole the property, conveyed it to John Whitmer, and John Whitmer to William W. Phelps; and then the officers of law found it. . . . You appealed to our beloved brethren, Presidents Joseph Smith, jr., and Sidney Rigdon, men whose characters you had endeavored to destroy. . . . By secret efforts, [you] continued to practice your iniquity and secretly to injure their character, notwithstanding their kindness to you. . . . As we design this paper to be published to the world, we will give an epitome of your scandalous conduct and treachery for the last two years. . . .

Cowdery and his company [in Kirtland earlier] were writing letters to Far West, in order to destroy the character of every person that they thought was standing in their way; and John Whitmer and William W. Phelps were assisting to prepare the way to throw confusion among the saints of Far West. . . .

You have the audacity to threaten us that, if we offered to disturb you, you would get up a mob from Clay and Ray counties. For the insult, if nothing else, and your threatening to shoot us if we offered to molest you, we will put you from the county of Caldwell: so help us God.

Well-known men who signed this letter were Hyrum Smith, Sampson Avard, Jared Carter, Levi Hancock, Newel Knight, Philo Dibble, Charles C. Rich, John Smith, Orin Porter Rockwell, Ebenezer Robinson, George W. Robinson, Seymour Brunson, Joseph Holbrook, Dimick Huntington, and Amasa Lyman.[22]

Although the document mostly attacked Oliver Cowdery and Lyman Johnson, it also charged W. W. Phelps with actions that he never denied:

· Phelps concealed property stolen by Cowdery in his house.

· Phelps and John Whitmer assisted Cowdery in sowing confusion in Far West before Joseph Smith’s arrival.

· As postmaster in Far West, Phelps opened, read, and destroyed some letters meant for other Far West residents. (Phelps essentially admitted problems at the post office when he testified in November.)[23]

The June 18 letter to the dissenters fulfilled its desired intent. The next day, Tuesday, June 19, Oliver Cowdery, David and John Whitmer, and Lyman Johnson, fearing that they might be lynched, fled Far West for Clay County and took up temporary refuge with fellow dissenter William McLellin in Clay County. They stayed with him until their families could catch up with them. Their family members reported that all their belongings except clothing and bedding were robbed by their oppressors. Soon these men and their families, totaling about thirty-five in number, took up permanent residence in Richmond, Ray County.[24]

John Corrill wrote, “This scene I looked upon with horror, and considered it as proceeding from a mob spirit.”[25] The terrible irony in this affair is that Sidney Rigdon and these many other men employed the same tactics against the dissenters in 1838 that Jackson County leaders and militia members used to drive the Mormons out of their county in 1833. When the dissenters soon spoke with other Missourians about their banishment, they gave the Missouri government ammunition against the Mormons.

But what happened to William W. Phelps and his family? He had been addressed as a dissenter along with the others in the removal petition. Why didn’t he flee with the others? The answer is that he immediately asked for pardon from church and military officials. According to his November testimony, “I was willing to do any thing that was right, and, if I had wronged any man, I would make satisfaction.” This doesn’t mean, however, that the militant factions loyal to the First Presidency in Far West trusted him. In his testimony, he added, “For some time before and after [a second] meeting an armed guard was kept in town and one of them at my house, during the night, as I supposed, to watch my person.” He also conceded, “At this meeting I agreed to conform to the rules of the church in all things, knowing I had a good deal of property in the county, and if I went off I should be obliged to leave it.”[26] John Corrill reported that the intimidation tactics “compelled others of the dissenters to confess and give satisfaction to the Church.”[27] Phelps and a few others heretofore allied with the dissenters decided to conform to the new order in Far West. Because some of the his children were teenagers or even older and not easily removed out of their circumstances, Phelps was further motivated to stay in Far West.

The Danites

In June 1838 a paramilitary organization called the “Danites” was created in Far West. A duly organized Caldwell County militia already existed, and a number of officers had been legally commissioned in it, including W. W. Phelps. All men over eighteen were invited to be part of the militia. County and state militias were a common and widely acceptable means in America at that time to defend the populace against threats to common safety.[28] Latter-day Saints in Caldwell were pleased that in their own “Mormon County” they had the privilege of a militia composed of their own officers and men. But, sadly, and actually tragically, an additional military organization, the Danites, came into being. One historian explains:

In early June 1838, a number of men under the leadership of Sampson Avard, Jared Carter, and George W. Robinson began meeting in Far West to discuss the problems being generated by the dissenters and how best to deal with them. Those assembled subsequently organized, declared their allegiance to Joseph Smith, and vowed to uphold the voice and actions of the First Presidency. Furthermore, these ultra-loyalists determined that any members of the society who demonstrated any manner of disloyalty would be threatened with severe repercussions and punishment. . . . The organization was initially known by two names, “The Daughter[s] of Zion” and “the Brother[s] of Gideon,” but soon became known as the Danites, a name derived from the prophecy of Daniel wherein he foresaw that the Saints in the last days will take possession of the kingdom of God “and possess it forever” (Daniel 7:22).[29]

The Danites’ reason for existence initially was to electioneer for Mormon candidates for offices in Caldwell and Daviess Counties. But also early on, the Danites determined to get rid of the Mormon dissidents from Caldwell County. Later they would participate in military operations as well as illegal raids of private property in the Mormon Missouri War. Some of the Danites were regulars in the Mormon-dominated Caldwell and Daviess Counties militias, but some were not. As the war would play out, it became difficult to differentiate the acts of the Danites from county militia operations. Joseph Smith helped inspire the militancy that embodied the Danites’ aims and activities, but he did not organize the paramilitary group or give direct orders to its leaders.[30] Sidney Rigdon, however, had a more direct connection to the Danites. In his November testimony before a preliminary hearing, W. W. Phelps referred back to how he gradually learned about the Danites and their work:

It was observed in the meeting that, if the person spoke against the presidency, they would hand them over to the hands of the Brother of Gideon. — I knew not, at the time, who or what it meant. Shortly after that I was at another meeting, where they were trying several — the first presidency being present; Sidney Rigdon was their chief spokesman. The object of the meeting seemed to be to make persons confess, and repent of their sins to God and the presidency . . . and they said, whenever they found one guilty of these things, they were to be handed over to the Brother of Gideon. Several were found guilty, and handed over as they said. I yet did not know what was meant by this expression, “the brother of Gideon.” Not a great while after this, secret or private meetings were held; I endeavored to find out what they were; and I learned from John Corrill and others that they were forming a secret society called Danites, formerly called the Brother of Gideon.[31]

Corrill wrote that the Danites “bound themselves under oath to keep the secrets of the society, and covenanted to stand by one another in difficulty, whether right or wrong, but said they would correct each others wrongs among themselves.” He added that “the word of the presidency should be obeyed, and none should be suffered to raise his hand or voice against it.”[32]

W. W. Phelps felt uncomfortable about what he first learned about the Danites. His friend Reed Peck reported that he, Phelps, Corrill, and John Cleminson all felt bad about what was happening, but they feared to fully speak their minds at that time.[33] Moreover, Phelps felt that he wanted to be back in the church he loved and to be acceptable in the eyes of Joseph Smith.

Summer 1838

The Prophet recorded a revelation pertaining to former presidents Frederick G. Williams and W. W. Phelps, erstwhile dissidents who were now striving to conform to church discipline. Joseph Smith’s official journal for July 8, 1838, reads as follows:

Revelation Given the same day {July 8, a Sunday}, and at the same place {public square in Far West}, and read {by Joseph Smith} the same day in the congregations of the saints Making known the duty of F[rederick] G. Williams & Wm W. Phelps Verrily thus saith the Lord in consequence of their transgressions, their former standing has been taken away from them And now if they will be saved, Let them be ordained as Elders, in my Church, to preach my gospel and travel abroad from land to land and from place to place, to gather my Elect unto me saith the Lord, and let this be their labors from hence forth Even so Amen[34]

When Newel K. Whitney made a copy of this revelation, he noted that it was preceded by a prayer: “O Lord what is thy will concerning W W Phelps & F. G. Williams.”[35] Both W. W. Phelps and F. G. Williams had already been rebaptized, in late June.[36]

Phelps and Williams did not go on a mission at this time. Other pressing events got in the way, including the need to keep order in Far West and to help new immigrants settle in Diahman and other places in Daviess County—and then the Mormon Missouri War broke out in early August. Phelps and Williams were legitimate church members at this juncture and up through the end of the war in November.

As two of the Caldwell County justices, W. W. Phelps and John Cleminson (who was also clerk of the court), became involved in the issue of “vexatious lawsuits.” Joseph Smith approached both in an attempt to dissuade them from issuing any writs against him, Sidney Rigdon, or Hyrum Smith. Cleminson indicated that he was not a judge of whether the writs were a “vexatious suit” or not. He then testified, “I felt myself intimidated, and in danger, if I issued it, knowing the regulation of the Danite band.”[37] For his part in this episode, Phelps reported the following:

In the fore part of July, I being one of the justices of the county court, was forbid by Joseph Smith, jr., from issuing any process against him. . . . I observed to Mr. Smith that there was a legal objection to issuing it; that the cost (meaning the clerk’s fee) had not been paid. Smith replied, he did not care for that; he did not intend to have any writ issued against him in the county. These things, together with many others, alarmed me for the situation of our county; and at our next circuit court, I mentioned these things to the judge and several members of the bar.[38]

Also in July, W. W. Phelps was one of thousands in attendance at Sidney Rigdon’s Independence Day address that set the stage for warfare between the Mormons and the Missourians. Phelps was actually forewarned of the event: “A few days before the 4th day of July last, I heard D. W. Patten, (known by the fictitious name of Captain Fearnaught) say that Rigdon was writing a declaration, to declare the church independent. I [Phelps] remarked to him, I thought such a thing treasonable—to set up a government within a government. He [Patten] answered, it would not be treasonable if they would maintain it, or fight till they died.”[39]

Mormon communities in western Missouri in the late 1830s. Map by Brandon S. Plewe. Mormon Historical Studies 16, no. 1 (Spring 2015): 58.

Mormon communities in western Missouri in the late 1830s. Map by Brandon S. Plewe. Mormon Historical Studies 16, no. 1 (Spring 2015): 58.

That day Rigdon’s address was considered a patriotic success.[40] Since the latter part of his speech was more volatile, however, its repercussions would soon be felt throughout northern Missouri. Rigdon emphasized, “We have suffered [the world’s] abuse without cause, with patience, and have endured without resentment, until this day, and still their persecutions and violence does not cease. But from this day and this hour, we will suffer it no more.” In the name of Jesus Christ, he warned that any men who attempted to trample on the Saints’ rights would do so at the expense of their lives. “And that mob that comes on us to disturb us; it shall be between us and them a war of extermination, for we will follow them, till the last drop of their blood is spilled, or else they will have to exterminate us: for we will carry the seat of war to their own houses, and their own families, and one part or the other shall be utterly destroyed.” Joseph Smith gave his approval to the address and charged the Elders’ Journal press to print it and distribute it among both Mormons and non-Mormons.[41]

Phelps felt terribly alarmed after hearing Rigdon’s address. He worried that retaliation would come soon from the Mormons’ enemies. “Along through the summer and fall a storm appeared to be gathering,” he noted. Phelps took it upon himself to check out the feelings of citizens in the adjoining counties of Ray and Clay. He observed, “[I] saw and conversed with many gentlemen on the subject, who always assured me that they would use every exertion, that the law should be enforced; and I repeatedly made these things known in Caldwell county.”[42] However, when circumstances got out of hand in Carroll and Daviess Counties, where many Mormons had settled contrary to the wishes of the original inhabitants, several northern Missouri counties raised forces to keep the Mormons under control. Phelps would be an eyewitness to some of these searing events.

Missouri Mormon War

War began with an election-day brawl in Gallatin, Daviess County, on August 6, 1838. Mormons had quickly gained as many inhabitants as the original settlers in Daviess in the space of less than two months. Non-Mormon ruffians attacked some Mormon voters. False rumors spread quickly that there were deaths on both sides. Fighting ignited passions on each side, though, and open hostilities soon took place in four counties—Daviess, Carroll, Ray, and Caldwell. The war would last through November 1.[43]

W. W. Phelps played a relatively small role in the war. He was present on the Daviess County front when a series of skirmishes erupted on October 15, 1838. For five days, anti-Mormon vigilantes tangled with a mixture of Mormon Danites and Caldwell/

Understanding the context is necessary here. A colony of Saints, under Joseph Smith’s direction in June, had gathered to De Witt in Carroll County at the confluence of the Grand and Missouri Rivers. De Witt was designed to be a port of departure toward Daviess County for the incoming immigrants from the East. Carroll County citizens were incensed that Mormons had come in among them and were still coming in ever-increasing numbers. Illegal guerilla warfare against the Mormons in De Witt took place over many weeks. Finally, a horrible siege took place on October 2–10. Mormon forces from Far West, including Joseph Smith, came to reinforce De Witt. Mob forces who were actually mutineers from at least seven county militias came with cannon and other arms to conquer the Mormons. The Saints in De Witt made an appeal to Governor Boggs, but he simply replied that the two opposing forces “fight it out.” Mormons in De Witt simply had no other choice than to leave their properties and evacuate to Far West. Joseph Smith reported, “During our journey we were continually harassed and threatened by the mob, who shot at us several times, whilst several of our brethren died from the fatigue and privation which they had to endure, and we had to inter them by the wayside, without a coffin, and under circumstances the most distressing. We arrived in Caldwell on the twelfth of October.”[44]

Then, upon arriving in Far West, Joseph Smith learned the distressing news that the anti-Mormon mobs, eight hundred strong, had left Carroll County and were moving toward Daviess County, about eighty-five miles to the west, to drive the Saints from their homes and to abscond with their property. The Prophet called together a general meeting on Sunday, October 14. He testified that “greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his life for his brethren.” Smith then asked that all men who were willing to stand by him in battle to gather at the public square the next morning.[45]

W. W. Phelps wrote of that next fateful day:

I was at the meeting the Monday [October 15, 1838] before the last expedition to Daviess, having learned that steps would be taken there which might affect me. At this meeting, the presidency, together with many others, were there, to the number of perhaps 200 or 300, or more. Joseph Smith, jr., I think it was, who addressed the meeting, and said, in substance, that then they were about to go to war in Daviess county; that those persons who had not turned out their property should be taken to maintain the war. This was by formal resolution, and was not objected to by any present. . . . [Smith] rose and moved that [the dissenters] be taken out into Daviess county, and, if they came to battle, they should be put on their horses with bayonets and pitchforks, and put in front: this passed without a dissenting voice. There was a short speech made then, by Joseph Smith, jr., about carrying on the war; in which he said it was necessary to have something to live on; and, when they went out to war, it was necessary to take spoils to live on.[46]

Phelps may have been exaggerating here, but interestingly each aspect of this testimony is backed up by testimony of others at the Richmond hearing in November 1838 or by reports of others who were also eyewitnesses to these events of October 15–19, 1838, in Caldwell and Daviess Counties. Joseph Smith indeed authorized the gathering of “booty” from non-Mormons as a necessary act of war in order for the Mormons to feed themselves.[47]

W. W. Phelps, fearing what might happen, held back in Far West for two days and gathered supplies and provisions that he then took to Diahman, arriving the evening of Wednesday, the seventeenth. He updated Joseph Smith about militia troops in Far West and then took his rest on the floor of the “tavern.” He recounted:

Some time before day I awoke, and found Lyman Wight [leader of the Mormon Daviess militia and Danite troops] and Captain Fearnaught [David W. Patten, who was also a Danite] in the house; he [Wight] said he had an express to General Parks informing him that his militia was not needed. Wight asked J. Smith, twice if he had come to the point now to resist the law. . . . Smith replied, the time had come when he should resist all law. In the fore part of the night after my arrival I heard a good deal of conversation about drawing out the mob from Daviess. I heard J. Smith remark there was a store at Gallatin, and grocery at Millport; and in the morning after the conversation between Smith and Wight about resisting the law, a plan of operations was agreed on, which was, that Capt. Fearnaught, who was present, should take a company of one hundred men, or more, and go to Gallatin, and take it that day; to take the goods out of the store in Gallatin, bring them to Diahmon, and burn the store. Lyman Wight was to take a company and go to Millport on the same day; and Seymore [Seymour] Brunson was to take a company, and go to the Grindstone fork on the same day. . . .

On the same day and evening I saw both these companies return; the foot company had some plunder, which appeared to be beds and bed-clothes, &c. They passed on towards the bishop’s store, but I know not what they did with the plunder.

Phelps also testified that he saw a large clock carried about by George W. Robinson (who was a Danite) that he had stolen from a Daviess County non-Mormon resident.[48] All three Mormon incursions into enemy territory led by three different Danite commanders—David Patten, Lyman Wight, and Seymour Brunson—indeed were successful, and a great deal of booty was brought back to Diahman and placed in the storehouse administered by Bishop Vinson Knight. The furniture and food were then used to supply civilian Mormons who had fled from outlying areas in Daviess County as well as the soldiers.

W. W. Phelps stayed another night, October 18, in Diahman and then returned to Far West with a message that wood and provisions, given the cold and stormy weather, were to be provided to the families of the troops from Far West who had gone to Daviess. He continued to testify:

For the purpose of giving that information, [on Saturday, October 20] I was invited to a school house, where I was admitted. The men being paraded before the door when I arrived, in number about 40 or 50. It was remarked that these were true men; and we all marched into the house. A guard was placed around the house, and one at the door.

Mr. Rigdon then commenced making covenants, with uplifted hands. The first was, that if any man attempted to move out of the county, or pack their things for that purpose, that any man then in the house, seeing this without saying anything to any other person, should kill him, and haul him into the brush, and that all the burial he should have should be in a turkey buzzard’s guts, so that nothing of him should be left but his bones. That measure was carried in form of a covenant with uplifted hands.[49]

Rigdon gave Phelps the assignment to collect several wagons and transport families and supplies to Diahman. He fulfilled this duty on Monday, October 22. Phelps was then sent back the next day, Tuesday the twenthy-third, to Far West with four wagons laden with beef and pork and various other supplies that had been stolen from non-Mormons in the booty collection.[50] Phelps did no more in the war effort until the next Tuesday, October 30.

Circumstances went from bad to worse for the Mormons in the war. Various Missouri militia leaders who were already predisposed against the Mormons sent reports to Governor Lilburn Boggs in Jefferson City that the Mormons needed to be reined in and driven from the state. Daviess County non-Mormon exiles that had been driven out of the county by Danites fanned the flames of fear of Mormons in Ray County. Boggs also received false reports of Mormon military activity in Ray and Clay Counties. Boggs refused to go to the seat of war himself and didn’t even try to set up an honest board of inquiry to determine who was at fault in all the various skirmishes that took place in Carroll, Daviess, Caldwell, and Ray Counties. History shows that the majority of the unlawful war atrocities were perpetrated by non-Mormon militias or vigilantes. Mormons were also guilty of war crimes, but to a much lesser extent. However, only the Mormons were charged with crimes and brought to court. Never were any anti-Mormons even charged with crimes. Governor Boggs issued his infamous “Extermination Order” on October 27 that led to the siege of Far West.

What happened with W. W. Phelps’s nemeses—apostles Thomas B. Marsh and David W. Patten, who had taken over the Missouri stake as presidents pro tempore?

Once Joseph Smith was in Far West, he appointed Elders Marsh and Patten along with Brigham Young to continue as a stake presidency. Because of the troubles in 1838, no new presidency was ever called. Marsh and Patten often met with the First Presidency regarding church policy, including dealing with dissenters like Phelps, the Whitmers, Cowdery, and Johnson. Both Marsh and Patten also labored with fellow apostles to set up future foreign missions that were to start the next year. Marsh was the ad hoc editor of the Elders’ Journal in July and August 1838. He wrote extensively for both issues and included an extensive article by David Patten[51] as well. In a self-serving manner, he wrote of his and Patten’s complete loyalty to Joseph Smith and the First Presidency.[52] Marsh also wrote an exceptionally sarcastic article about the apostates in Kirtland, particularly laying into Warren Parrish and Luke Johnson.[53] Again he was trying to curry favor with Joseph Smith.

David W. Patten, a militant by nature, joined the secretive Danites in June 1838. He held a commission in the Caldwell County Militia, but in his military forays into Daviess County and at the Battle of Crooked River, he was clearly functioning as a Danite.[54] Patten was chosen as “commander-in-chief” of a military body, primarily made up of Danites, sent to the Crooked River, where an anti-Mormon militia had taken three Mormon hostages. The tragic Battle of Crooked River took place in the early morning of Thursday, October 25. Patten led a charge against the enemy and was fatally wounded. His brave act scattered the enemy and thus likely saved many Mormon lives. He died about four o’clock that afternoon after futile attempts to care for his wounds. He has come to be known as the first apostolic martyr of this dispensation.

A more tragic outcome occurred, at least spiritually speaking, to Thomas Marsh in the latter portion of the war. Marsh went with Joseph Smith and about two hundred others on October 15, 1838, north to Daviess. In truth, he had been falling away from the faith for a few weeks. Marsh admitted in his memoirs that sometime in August he began to look at Joseph Smith and other leaders with a jaundiced eye and saw all sorts of faults in them. He was offended that the First Presidency did not side with his wife in a dispute brought before the high council. He didn’t like what he saw with the Danites. Marsh skirted Joseph Smith’s question to him about whether he planned to stay in the church or not. When he saw all the booty being illegally collected by Danite bands in Daviess County on October 18, he decided that he would turn against Joseph Smith and the church. He slipped away from the army in Diahman on October 20 and made his way to Far West. He got together with Orson Hyde, another disillusioned member of the Twelve, and fled with their families to Richmond in Ray County. On October 24, 1838, Marsh and Hyde swore out an affidavit before the Ray justice of the peace accusing Joseph Smith of multiple crimes. They stated that Joseph Smith had no respect for the law of the land and would, like Mohammed of old, use the sword to conquer his enemies.[55] Marsh and Hyde’s affidavit was used by Governor Boggs and other leaders to justify the government’s arrest and imprisonment of Joseph Smith and his fellow leaders. No other document or statement from “apostates” or “dissidents” was more critical to the persecution of the Saints than that of Marsh and Hyde. Joseph Smith, when he had the chance to know the contents of the document, according to his official history, expressed his disappointment: “He [Marsh] had been lifted up in pride by his exaltation to office and the revelations of heaven concerning him, until he was ready to be overthrown by the first adverse wind that should cross his track, and now he has fallen, lied and sworn falsely, and is ready to take the lives of his best friends. Let all men take warning by him, and learn that he who exalteth himself, God will abase.”[56]

Phelps as Peace Negotiator

Phelps joined George M. Hinkle as a peace negotiator in the Mormon Missouri War. Hinkle commanded the Caldwell County militia. He helped make plans for Mormon military activities in the war, including his organizing the seventy-five-man force that went on to participate in the Battle of Crooked River. After Governor Boggs issued his “extermination order,” Missouri militia forces marched toward Far West on October 28. Hinkle prepared a force to defend the city. After two days, Joseph Smith and Mormon military leaders realized that their forces were outnumbered and didn’t have as many arms. Hinkle became the obvious person to go to the militia to negotiate a surrender; he would be joined by Phelps and four others.

The two main Mormon negotiators for a surrender to Missouri militia forces were George Hinkle, commanding officer of the Caldwell militia, and his adjutant, Lt. Reed Peck. General Alexander Doniphan was the temporary commander of the militia forces approaching Far West. After Peck approached the militia with a white flag and spoke with Doniphan, the latter recommended that a peace commission be increased to five. Doniphan knew all the leading personalities in Far West well and thought that the five best negotiators should be Hinkle (the commander of the Mormon militia), Peck (also a militia officer), Phelps (a militia officer and officeholder), John Cleminson (a county judge), and John Corrill (state legislator). All five were prominent citizens of Far West. Peck secretly allied with Phelps, Cleminson, and Corrill in their mistrust of the Danites and their frustration with the excessive rhetoric and actions of church leaders since June.[57]

On Tuesday, October 30, General Samuel Lucas of Jackson County, a long-time enemy of the Mormons, took control of the Missouri militia forces. He would exercise command until General John B. Clark, the militia officer who was put in charge of the entire war operation by Governor Boggs, could arrive on the scene. Lucas brought with him a copy of the governor’s order and was determined to carry it out before the arrival of Clark, whom he considered to be a rival in the state militia system. In the afternoon, the peace commission, consisting of Hinkle, Peck, Corrill, Phelps, Cleminson, and militia captain Arthur Morrison (Morrison having become the sixth member), gained audience with Lucas. He gave them a copy of the governor’s order, to which they reacted with great shock at its severity. Lucas also demanded several things in exchange for a promise that his forces would not attack the city and wreak havoc on the Saints. Joseph Smith had urged the commission to sue for peace, so they took Lucas’s demands to the Prophet. The demands were intentionally high:

- Give up their leaders to be tried and punished. Specifically, Lucas wanted Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, George W. Robinson, Lyman Wight, and Parley P. Pratt. (These first four were considered leaders in the Daviess County raids and planners of treasonous activities. Pratt was wanted for his role in the Battle of Crooked River.)

- For those Mormons who had taken up arms, they were to make an appropriation of their property to pay debts or indemnify damages done to Daviess County citizens.

- The rest of the Mormons were to leave the state at a time to be determined.

- Hand over all arms, including rifles, pistols, swords, and knives.

Hinkle tried reasoning with Lucas about these unconstitutional demands, but the general indicated that if he did not receive the designated wanted men by sundown, he would have his forces attack Far West that very night, and no one would be protected. The commission returned with the conditions.

Joseph Smith did not want a slaughter to take place, so he said “they would submit, and the Lord would take care of them.”[58] All five wanted men went with the peace commissioners to the militia camp thinking they would be treated respectfully and even be allowed to leave if they did not agree with the provisions laid down by General Lucas. Instead, as soon as these men were delivered, they were surrounded by the troops.

Aftermath of the War

Joseph Smith and his four companions were treated harshly over the next three days before Lucas took them as prisoners to Independence. A death sentence was even pronounced on them by an illegal court-martial; this was thwarted by courageous General Alexander Doniphan, who had always had some sympathy toward the Mormons. The militia also persecuted the families of these men and took all their properties. Joseph Smith and the other prisoners, and then other men who were subsequently taken into custody, came to believe they had been betrayed into the hands of the enemy by a traitorous George Hinkle and the other peace commissioners, Phelps included. Soon these men were treated as pariahs among the Saints in Far West. Each in his own way, except Morrison, became embittered. This would not be an easy time for Hinkle, Peck, Corrill, Cleminson, and Phelps.[59]

Hinkle did not think he was acting improperly by taking Joseph Smith and the others to Lucas and the militia. He and the other commissioners thought they were only setting up a peace parley and that the legal system would treat these potential prisoners according to constitutional guidelines instead of being mercilessly handled as fearsome hostages.[60]

The number of Mormon prisoners gradually grew to sixty-four. They were all brought to Richmond, where at least there was an unfinished courthouse that could house many of them and a court of inquiry could be held. Governor Boggs chose Austin A. King, a circuit court judge for northern Missouri, to preside. General John B. Clark, who had taken over the military command in Far West, “commenced ferreting out the guilty amongst the Mormons who were there—this business employed [Clark’s] time for two days and nights.” Clark said he obtained information from dissenters,[61] who easily could have been Phelps, Hinkle, Corrill, Peck, and Cleminson. These five didn’t feel so loyal anymore after having been branded as traitors. Each of the five testified at the court of inquiry that began in the Richmond courthouse on November 12, less than two weeks after Joseph Smith and the first prisoners were taken.

The Richmond court proceeding was similar to a modern preliminary hearing because it could not convict anyone. Rather, King was to decide which of the accused should be bound over to trial. The hearing lasted through November 29. All witness statements, including Phelps’s, were transcribed, but likely not totally accurately, because there were no hired court reporters, no recording devices, nor any use of shorthand. By order of the governor and the legislature, the entire transcripts of the hearing along with other documents pertaining to the Mormon Missouri War were compiled in 1839, and in 1841 they were published.[62]

Sampson Avard, a cofounder of the Danites the previous June, had been captured by troops on November 2. He turned state’s evidence and thereby avoided all prosecution, even though he may have been the guiltiest Mormon of them all. Clearly, King and all other proclaimed anti-Mormons wanted to punish the leaders of the Saints most. The hearing was decidedly one-sided. Phelps, Hinkle, and Corrill were key witnesses.

The prisoners were charged with one or more of the following crimes: high treason against the state, murder, burglary, arson, or robbery and larceny. After hearing all the evidence, Judge King discharged twenty-nine defendants for lack of sufficient evidence. Twenty-four were charged with bailable offenses and were turned over to Daviess County authorities for trial. Joseph Smith, Hyrum Smith, Sidney Rigdon, and three others were charged with treason and committed to the Clay County jail in Liberty. Charged with murder because of the killing of a militia member in the Battle of Crooked River were Parley P. Pratt and four others, who were kept in Richmond because the shooting had taken place in Ray County. Sidney Rigdon, who was severely ill, was able to post bail and was released. He then escaped into Illinois.[63]

W. W. Phelps and his comrades Hinkle, Corrill, and Cleminson were forced, or at least cajoled, into writing an official letter endorsing the fair treatment that General John Clark had afforded the Mormons in Far West after the surrender. In a letter dated November 23, 1838, these men testified that Clark and his troops treated the Mormon families with respect and that they had heard no complaints. They also said Clark showed extreme kindness by allowing the Mormons to stay in Far West until they could arrange their affairs before evacuating the state.[64] This statement is false in all respects because Phelps and the others would have been eyewitnesses of the maltreatment of many men, women, and children at the hands of the soldiers throughout the month of November.[65]

Naturally, Joseph Smith was deeply perturbed that erstwhile loyalists had turned against him at the Richmond hearing. He also came to believe, although not altogether correctly, that the peace commission that included W. W. Phelps had traitorously turned him over to the Missouri militia forces. On December 16 from Liberty Jail, the Prophet penned a lengthy letter to the Saints in Far West, including refugees from Daviess County. He wrote that he and the other prisoners gloried in their tribulation, and he gave many words of encouragement. He heaped curses upon the Missouri priests, magistrates, and soldiers who had oppressed the Saints. His statement regarding those whom he considered internal traitors follows:

Look at the dissenters. And again if you were of the world the world would love its own Look at Mr. [George M.] Hinkle. A wolf in sheep’s clothing. Look at his brother John Corrill Look at the beloved brother Reed Peck who aided him in leading us, as the savior was led, into the camp as a lamb prepared for the slaughter and a sheep dumb before his shearer so we opened not our mouth. But these men like Balaam being greedy for reward sold us into the hands of those who loved them, for the world loves his own. I would remember W[illiam] W. Phelps who comes up before us as one of Job’s comforters. God suffered such kind of beings to afflict Job, but it never entered into their hearts that Job would get out of it all. This poor man who professes to be much of a prophet has no other dumb ass to ride but David Whitmer. . . . we have waded through an ocean of tribulation, and mean abuse practiced upon us by the ill bred and ignorant such as Hinkle, Corrill, and Phelps, Avard, Reed Peck, [John] Cleminson, and various others who are so very ignorant that they cannot appear respectable in any decent and civilized society, and whose eyes are full of adultery and cannot cease from sin.[66]

These words, when he had the chance to read them, no doubt cut W. W. Phelps to the core. In his own mind, he had tried to help Joseph Smith and the Saints avoid problems that they were bringing on themselves by their belligerence against the laws of the land, their determination to defend themselves at all costs, and their willingness to attack their enemies by burning their homes and stealing their possessions. Phelps had surely tried to bring about peace and avoid total disaster for the Saints in the face of annihilation. Now he was being mocked and accused of unfaithfulness, ignorance, and possibly adultery. It must be remembered, however, that Phelps’s testimony at the Richmond court of inquiry had contributed to Smith’s incarceration.

A recurring feeling in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries is that W. W. Phelps was a despicable traitor and his actions constituted a major cause, if not the only one, for Joseph Smith’s arrest and incarceration and the persecutions that befell the Saints in late 1838 and early 1839. However, the affidavit of Thomas Marsh and Orson Hyde in late October 1838 had considerably more to do with Joseph Smith and the Saints’ problems than anything Phelps did. The same can be said of the November testimony of Sampson Avard in Richmond. Many others’ testimonies likewise hurt Joseph Smith and the church. And church leaders, Joseph Smith included, contributed much to their own undoing during this period.

Significant is the corroboration of W. W. Phelps’s claims in his court testimony by other historical sources from the period. His testimony emphasized that the Danites posed a threat to the church and to Missourians and that Mormon forces took booty from Daviess County Missourians during the war.

Joseph Smith himself eventually came to realize that he and others had made significant mistakes in Missouri. He admitted as much in a lengthy letter written on March 20, 1839, from Liberty Jail to all the Saints exiled in Illinois. Joseph Smith’s most recent biographer, Richard Lyman Bushman, assessed changes in Joseph Smith’s points of view:

While in prison, Joseph mulled over the problems of the past year. The Missourians were to blame, of course, but he now saw that the Church had erred, and he had made mistakes himself. . . .

Apart from the leaders’ mistakes, Joseph saw that the Church had been in error. The tone and spirit of their meetings had been unworthy. Beware, he warned, of “a fanciful and flowe[r]y and heated immagination.” . . . [Bushman quotes John Corrill to the effect that Joseph Smith had promised prosperity and deliverance, but none came.][67] Everything Corrill said was true. The great work had met defeat after defeat. None of the Mormon settlements had lasted in Ohio or Missouri. Joseph’s seven-year stay in Kirtland was the longest in any gathering place. At Far West, the Saints survived barely two years. The gathering led to one disaster after another, as local citizens turned against the expanding Mormon population. Joseph lost old friends and trusted supporters: Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, Frederick G. Williams, William W. Phelps, Orson Hyde, Martin Harris, and Thomas B. Marsh all left him in 1838, worn down by failures and perceived missteps. Six of the seven—all but Whitmer—returned to the Church before they died, and Phelps and Hyde within a few months. But the events of 1838 brought these faithful souls to the breaking point.

Bushman concluded that Joseph Smith was required of God to gain “experience” and that “life was a passage. The enduring human personality was being tested. Experience instructed. Life was not just a place to shed one’s sins but a place to deepen comprehension by descending below them all. The Missouri tribulations were a training ground.”[68] For W. W. Phelps too, the Missouri experiences were an important test and training ground, as well as a reminder of his need to humbly repent of his own missteps and sins.

Notes

[1] This is the conclusion drawn in Leland H. Gentry and Todd M. Compton, Fire and Sword: A History of the Latter-day Saints in Northern Missouri, 1836–39 (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2011), 88.

[2] D&C 107:72, 74, 76, 78, 82–84.

[3] MB2, 118–33; FWR, 163–78; MHC, vol. B-1, 789; HC, 3:16–20; JSP, J1:250–57; JSP, D6:83–104.

[4] JSP, D6:109.

[5] Gentry and Compton, Fire and Sword, 97.

[6] John Corrill, A Brief History of the Church of Christ of Latter Day Saints (St. Louis: printed for the author, 1839), in JSP, H2:165.

[7] Corrill, Brief History, in JSP, H2:164.

[8] Missouri General Assembly, Document Containing the Correspondence, Orders &c. in Relation to the Disturbances with the Mormons; and the Evidence Given Before the Hon. Austin A King . . . (Fayette, MO: Printed at the office of the Boon’s Lick Democrat, 1841), 121 (hereafter Document). The original handwritten minutes of the Richmond court proceedings are located at http://

[9] JSP, D6:112–18; JSP, J1:257–60; MHC, vol. B-1, 790–91; HC, 3:23–25; Elders’ Journal 1 (August 1838): 52–53.

[10] JSP, D6:77–79; JSP, J1:249; MHC, vol. B-1, 788; HC, 3:15–16. Whitmer gave his volume the name of “The Book of John Whitmer.” It has been cited frequently in this biography. Whitmer never handed his book over to the church. Eventually it fell into the hands of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now Community of Christ), who allowed it to be published twice in the twentieth century and again in the twenty-first century by the Joseph Smith Papers Project. JSP, H2:2–110.

[11] JSP, J1:260; MHC, vol. B-1, 791; HC, 3:25. In Joseph Smith’s journal, we also note that he spent April 30 to May 4 dictating his history. JSP, J1:263–64; MHC, vol. B-1, 793; HC, 3:26.

[12] JSP, J1:270; MHC, vol. B-1, 797; HC, 3:34.

[13] JSP, J1:271; MHC, vol. B-1, 798; HC, 3:35; D&C 116:1.

[14] See Alexander W. Baugh, “The History and Doctrine of the Adam-ondi-Ahman Revelation (D&C 116),” in Foundations of the Restoration: Fulfillment of the Covenant Purposes, ed. Craig James Ostler, Michael Hubbard MacKay, and Barbara Morgan Gardner (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2016), 157–87. Baugh argues that in Kirtland Phelps learned of the whole story and doctrine of Adam-ondi-Ahman from Joseph Smith in May and June 1835. At the same time, Phelps wrote his poem “Adam-ondi-Ahman,” which would become a hymn; and, significantly, Phelps helped formulate the language in D&C 107:53. See especially pp. 159–66.

[15] Alexander L. Baugh, “A Call to Arms: The 1838 Mormon Defense of Northern Missouri” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1996), 101.

[16] JSP, J1:266; MHC, vol. B-1, 794; HC, 3:27.

[17] Corrill, Brief History, in JSP, H2:165.

[18] Corrill, Brief History, in JSP, H2:165. Another Mormon observer, Reed Peck, also called it the “Salt Sermon.” Peck claimed that Rigdon laid out all the crimes committed by the dissenters and “called upon the people to rise en masse and ride [rid] the county of such a nuisance.” Rigdon added that “it is the duty of this people to trample them into the earth and if the county cannot be freed from them any other way I will assist to trample them down or to erect a gallows on the square of Far West and hang them up.” Reed Peck manuscript, 1839, 24–25, typescript, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT; JSP, H2:97n298. Rigdon may have been alluding to passages from the Doctrine and Covenants (now D&C 101:39–40): “When men are called unto mine everlasting gospel, and covenant with an everlasting covenant, they are accounted as salt of the earth and the savor of men; they are called to be savor of men; therefore, if that salt of the earth lose its savor, behold, it is good for nothing only to be cast out and trodden under the feet of men.”

[19] Reed Peck manuscript, 25–26.

[20] Gentry and Compton lay out the case for Rigdon’s writing the document and Avard’s participation with it in Fire and Sword, 101, 105, 121nn129–33.

[21] The petition, published in Ebenezer Robinson’s newspaper The Return 1 (1889): 218–19, is reproduced in Gentry and Compton, Fire and Sword, 101–5, and available online at http://

[22] Gentry and Compton, Fire and Sword, 101–5; emphasis in original. Document, 103–6.

[23] Document, 122. Phelps would eventually be pushed out of his postmaster’s office by the church’s one-party political forces on August 6, 1838. He was succeeded by Sidney Rigdon. JSP, J1:297.

[24] “The Book of John Whitmer,” in JSP, H2:97–98; Corrill, Brief History, in JSP, H2:165; Reed Peck manuscript, 26–28. Baugh discusses these events in his “Call to Arms,” 76–77. George Robinson, who kept Joseph Smith’s journal, also recorded the flight of the dissenters “over the prairie.” JSP, J1:278.

[25] Corrill, Brief History, in JSP, H2:166.

[26] Document, 122–23. See JSP, D6:182.

[27] Corrill, Brief History, in JSP, H2:165.

[28] Alexander Baugh writes extensively about the development of the militia system in colonial America and then in the United States in his “Call to Arms,” 38–67. In appendix A he lists the Mormon officers who participated in the Caldwell and Daviess County militias. He provides the acts of Congress that allowed for the calling forth of a legalized militia in appendixes B and C. In appendix D he explains the military organization of a normal militia, including the officer titles and number of troops in a company, battalion, regiment, brigade, and division.

[29] Baugh, “Call to Arms,” 79–81. Editors of the Joseph Smith Papers wrote balanced descriptions of the Danites in JSP, J1:464 and JSP, D6:169–70, 687–88.

[30] JSP, D6:170.

[31] Document, 121–22.

[32] Corrill, Brief History, in JSP, H2:166–67.

[33] Reed Peck manuscript, 29.

[34] JSP, J1:285, 288, 288n189; underlining in original. See also HC, 3:46n8, written by editor B. H. Roberts.

[35] JSP, D6:183, 183n95.

[36] JSP, D6:182, 182n87.

[37] Document, 114–15.

[38] Document, 123. Reed Peck also reported the attempts of Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, and others to stop Cleminson from issuing the writs. Reed Peck manuscript, 37.

[39] Document, 123.

[40] Gentry and Compton, Fire and Sword, 136.

[41] The oration was first printed by The Elders’ Journal press. It was reprinted in Peter Crawley, “Two Rare Missouri Documents,” BYU Studies 14 (Summer 1974): 502–27 (emphasis added), and is available online at www.josephsmithpapers.org/

[42] Document, 123.

[43] Baugh, “Call to Arms,” 90–91. Baugh’s entire dissertation is dedicated to a better understanding of the Mormon Missouri War, with chapters titled “The War Begins: Conflict in Daviess County, August–September 1838,” “The Mormon Defense of De Witt [in Carroll County],” “The Mormon Defense of Daviess County, October 1838,” “The Battle between Mormon and Missouri Militia at Crooked River,” “The Massacre at Haun’s Mill,” “The Mormon Defense of Far West,” and “Surrender and Military Occupation.” Gentry and Compton likewise have extensive chapters on the Mormon Missouri War in Fire and Sword, 169–393.

[44] Governor Boggs’s comment is found in JPS, H1:472–73; PJS, 1:215; MHC, vol. B-1, 835; HC, 3:157. Joseph Smith’s statement is found in JSP, H1:474; PJS, 1:215–16; MHC, vol. B-1, 836; HC, 3:160.

[45] JSP, H1:474–75; MHC, vol. B-1, 836; HC, 3:162.

[46] Document, 122–23.

[47] See documentation in Gentry and Compton, Fire and Sword, 250–51, 267–80, 300–301, 303–17; Baugh, “Call to Arms,” 182–205. See also JSP, D6:265–68.

[48] Document, 123–24. Once again, all of Phelps’s allegations are backed up by the testimony or writings of others. John Corrill corroborated all of Phelps’s claims in Corrill, Brief History, in JSP, H2:176–79.

[49] Document, 124.

[50] Document, 125.

[51] “To the Saints Scattered Abroad,” Elders’ Journal 1 (July 1838): 39–42.

[52] “Far West, May, 1838,” Elders’ Journal 1 (July 1838): 33–38.

[53] “Argument to Argument Where I Find It,” Elders’ Journal 1 (August 1838): 55–60.

[54] For documentation of Patten’s military and Danite roles, see Baugh, “Call to Arms,” 96, 225–48, 385, 409; and Gentry and Compton, Fire and Sword, 252, 265n166, 284–89, 318n175, 543.

[55] “History of Thomas Baldwin Marsh”; Gentry and Compton, Fire and Sword, 290–95, 315nn126–28; Cook, “Thomas B. Marsh Returns to the Church,” 394–96. Marsh’s affidavit appears in Document, 57–59, and portions of it in HC, 3:167n2.

[56] MHC, vol. B-1, 838; HC, 3:166.

[57] Information about what Hinkle and the other members of the peace commission did is found in Reed Peck manuscript, 101–21; Corrill, Brief History, in JSP, H2:182–87; letter from G. M. Hinkle to W. W. Phelps, August 14, 1844, published in Sidney Rigdon’s Messenger and Advocate (Pittsburg, PA), August 1, 1845; Baugh, “Call to Arms,” 316–26; and Gentry and Compton, Fire and Sword, 353–58, 380–84.

[58] Corrill, Brief History in JSP, H2:186.

[59] Baugh, “Call to Arms,” 331–32; JSP, D6:296–97.

[60] Gentry and Compton, Fire and Sword, 373–76, 382–84; Baugh, “Call to Arms,” 331–32.

[61] Document, 65–66.

[62] See note 8 herein for full publication information.

[63] For synopses of the hearing and the results, see JSP, H1:481nn74–79; JSP, H2:188nn222–24, 189n225; and JSP, D6:273–74.

[64] Document, 87.

[65] My interpretation is that they were trying to avoid further persecution against themselves and their families by submitting to General Clark and offering this testimony.

[66] JSP, D6:300–301, 307 (emphasis added); MHC, vol. C-1, 868–73; HC, 3:226–33. Possibly, Joseph Smith referred to these men’s seeming apostasy as adultery in much the same way as the Israelites in the Old and New Testaments who fell away from the true God were an “adulterous generation.”

[67] See Corrill, Brief History, in JSP, H2:197.

[68] Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 378–80.