Declining Years And Death

Bruce A. Van Orden, "Declining Years And Death" in We'll Sing and We'll Shout: The Life and Times of W. W. Phelps (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 465–492.

In late 1853 William W. Phelps felt alive and productive in the kingdom of God in the mountains of Deseret, which by this time was orderly, productive, and free from oppression. He had contributed to Deseret’s success. Phelps often prayed and spoke at general conference and sat prominently in conference sessions among other leading high priests.[1] The Saints sang his hymns in conference and ward congregational settings. Phelps served on the University of Deseret Board of Trustees. He attended the annual Utah Territorial Legislature sessions as a representative from Great Salt Lake County. He spoke at numerous meetings and special gatherings. Phelps was in effect the Deseret News editor while Willard Richards lay on his sickbed. His annual Deseret Almanac was sold and spread far and wide throughout the emerging Utah settlements.

However, ever so gradually his star began to dim after 1854, and by the end of 1866 it had gone out almost entirely. Instead of being such a key player in the Restoration as he was from 1831 to 1838 and from 1840 to 1846, and even being an important contributor from 1846 to 1853, Phelps was relegated somewhat to the sidelines. What added more to his relative insignificance is that he was in a deteriorating state of dementia from 1866 until his death in March 1872.

Phelps’s declining years from 1854 onward are important to his life and memory. This man was always curious in his demeanor, but in his last years he was more eccentric than ever. Yet he strove to further God’s will on the earth in all ways that he felt he could. He also showed complete fealty to Brigham Young and other presiding church authorities. These years are best glimpsed by reviewing his ongoing publishing endeavors as well as his various other roles from legislator and explorer to translator and ordinance worker. The measure of the man is further revealed through his thoughts on the Civil War, his correspondence with Brigham Young, and insights into his family situation.

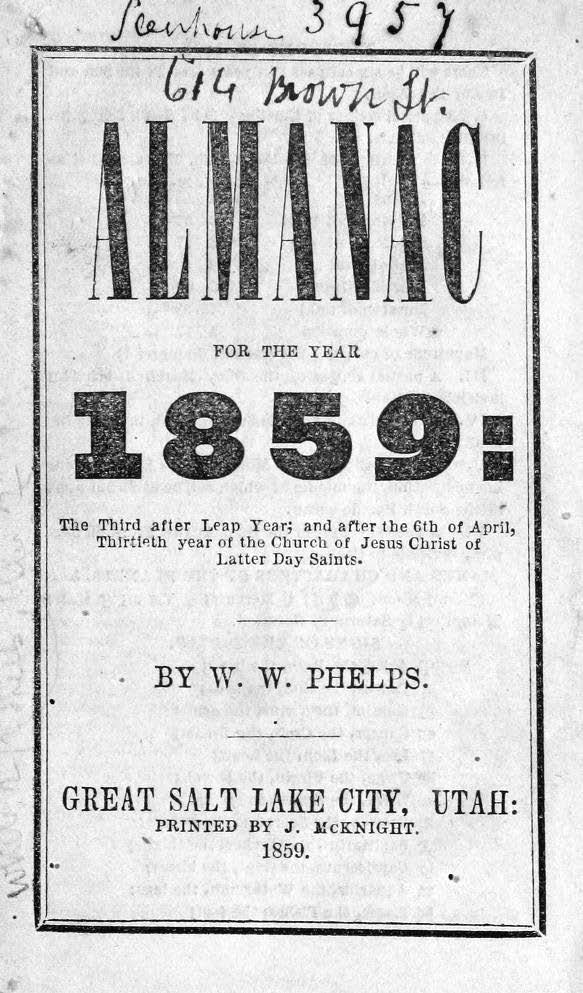

Continuing Publication of the Deseret Almanac

Phelps’s annual Deseret Almanac was his pearl, his shiny object, that he produced in his later years. Indeed, he declared, “A person without an Almanac is somewhat like a ship at sea, without a compass; he never knows what to do, nor when to do it: so Mormons, others, sect and Quaker, Buy Almanacs, and pay the maker.”[2] Phelps depended on the sale of his almanac for much of his yearly income. In America “the almanac functioned as the secular Bible. Where the Bible told people how to behave on Sunday, the almanac served as a guide during the rest of the week.”[3] The normal American almanac may have been mostly secular in nature, but Phelps’s Deseret Almanac was designed to be a spiritual guide as well because he emphasized church history, doctrinal statements, and his numerous parables and religious-oriented poetry.

Phelps’s almanac was typical in many ways. As the printer, he was also the almanac’s author and compiler. He included the standard calendars, weather information, astronomical data, and, beginning in 1857, astrological tables.[4] As with other almanac compilers, he provided useful household hints such as how to make candles, how to get hens to lay eggs, how to render hard water soft, how to make things fireproof and waterproof, and how to preserve herbs.[5] He listed government officials as well as church priesthood leaders. He published population figures. Increasingly, he provided advertisements of Utah business establishments.[6] The Deseret Almanac normally sold for twenty-five cents apiece, and Phelps received most of the profits.[7]

Phelps’s most noteworthy legacy from his almanac endeavors was his theological musings adapted from Joseph Smith’s expansive teachings of premortal existence, other worlds, and eternal progression. For example, in a fascinating poem that he “calculated for all Saints,” Phelps wrote the following lines under his pseudonym “King’s Jester.” He again pointed to the existence of a Heavenly Mother and of Kolob, residence of God.

Bear me on, Eternal Father—

Bear me through this world of woe;

Teach me how to do my duty,—

Where thou goest let me go:

Help me live or die triumphant,

Never, never let me fall;

Bear me through every trial,

Thou Almighty—all for all.

Give me daily food and raiment,

In a Kingdom full of truth,

Grant the Spirit’s consolation,

That that graced my “elder youth,”

In the realms of perfect freedom,

Where I scarcely knew “the rod,”

In the “infant school of glory,”—

In thy family, O God!

Fill me with that sacred wisdom,

I at first enjoyed with thee,

When the holy ones united

For eternal liberty:—

For an everlasting kingdom,

Where the light all truth promotes.

That was when they tried the spirits,

By their agency and votes,

For an everlasting kingdom,

Where the light all truth promotes.

Bless me with that precious feeling,

Jesus meekly shed abroad,

When he gave himself a ransom

For the out-cast sons of God:—

Greater love can none exhibit,

Than to die for friends they love;

’Tis a key to all perfection,

And it wins a crown above.

Call, O call me back to Kolob,

When the resurrection’s pass’d!

For I love my Father’s garden—

Where I promised in my childhood,

To be born,—(the second birth)

So, to try the gift of passion,

On a mission to the earth.

O that infant-spirit wisdom,

Which my Father gave to me,

In his mansion with my mother,

As I sat upon her knee!—

Sacred records kept in “Teman,”

Till the flesh has conquered sin,—

By the Priesthood, faith and virtue,

Then I’ll know them all again![8]

Throughout his entire publishing career, Phelps expressed his ideas about home and marital relations. Almost as if he could not help himself, he wrote “To Mormon Wives.”

Three things good wives should be like, and not like:—

First—Like a snail, neat within her house,—

And not like a snail, carry all upon her back.

Second—Like an Echo, speak when spoken to,—

And not like an echo, always have the last word.

Third—Like a Town Clock, keep time,—

But not like a town clock, alarm all the town.[9]

Through poetry Phelps further enunciated what he considered to be the wife’s role:

As the moon shed her rays round the earth,

So the wife throws her charms o’er her lord,

As the pledge of her love.[10]

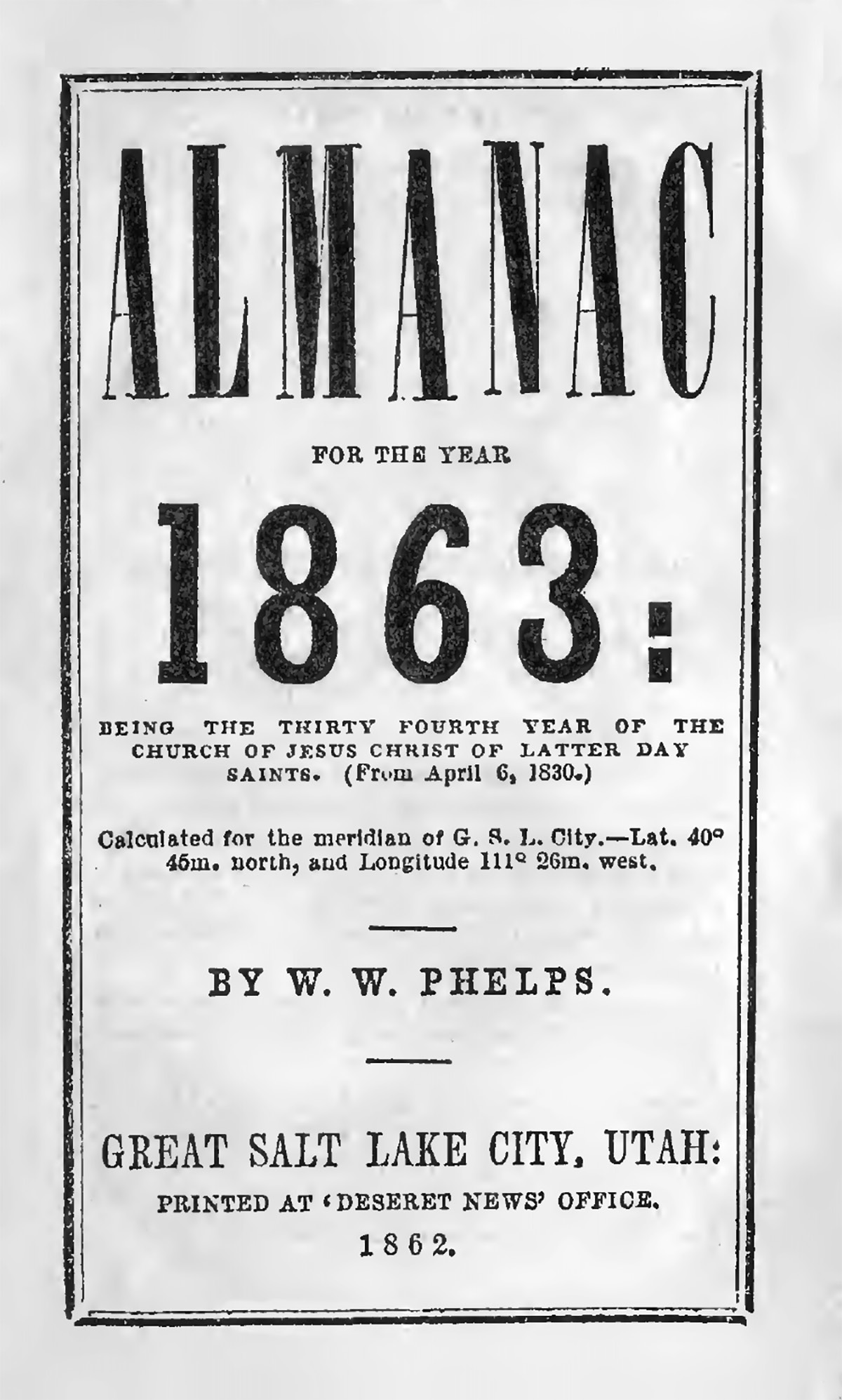

Phelps’s 1863 Deseret Almanac.

Phelps’s 1863 Deseret Almanac.

As the years progressed, the quality of Phelps’s almanacs diminished gradually. This is an evidence of his advancing years and of a decrease in his ability to think as acutely as he had done throughout his life. For example, his last published almanac, in 1865, was only eight pages long and did not contain his counsel and witticisms.

Yet, through his almanacs Phelps continued to promote Joseph Smith’s ministry and teachings. For example, in 1863 he published “Joseph Smith’s Last Dream.” “In June, 1844, when Joseph Smith went to Carthage and delivered himself up to Gov. Ford,” wrote Phelps, “I accompanied him, and while on the way thither, he related to me and his brother Hyrum the following dream.” The dream showed Joseph and Hyrum escaping a steamboat engulfed in flames and eventually finding solace among friends and relatives, their enemies William and Wilson Law having lost their lives in the conflagration.[11] This dream has received new energy in the minds of some Latter-day Saints in modern times through illustrated reenacting and commentary.[12]

Phelps did not publish an almanac in 1856 and 1857 owing to a dispute with the printing office over paying the printing costs in advance.[13] Albert Carrington, Deseret News editor, also refused to pay for the 1866 almanac.[14] In later years, Phelps desired to continue publishing the Deseret Almanac, as evidenced in this despairing letter to Brigham Young in March 1866:

I have just completed the compilation of an Almanac embracing 1866 and 1867 in one volume, and I greatly need the avails of it for a living—will you assist me in getting it published[?] Br Godbe has promised 50 dollars toward its publication; you can keep that, and there is such a call for them, the balance for publication will soon be realized. I do not mean to be understood as to be begging, but I labor in the “Endowments” and get but little and need more to make my family comfortable; and in my 75th year I am not able to labor much. If you will help me . . . you will confer a favor on your old friend and brother.[15]

Deseret News

Perhaps the most important contribution that Phelps made to the Deseret News during its first decade was continuing the series “History of Joseph Smith,” which was the official history envisioned by the Prophet. Phelps and editor Willard Richards considered this column of optimal importance. Phelps continued this series during Richards’s lengthy confinement and then on to its conclusion in January 1858.

Phelps often wrote news stories about events throughout Utah Territory. He especially enjoyed reporting on July 4th and July 24th holiday celebrations that included parades involving University of Deseret students. Many of the news items came in the form of letters from settlers themselves and were published in the paper. Phelps also printed missionary letters from Europe, the states, South Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and the Pacific islands. He continued to publish discourses of church authorities.

Occasionally, Phelps enjoyed inserting items with a play on words. For example: “It is said the devil has many imps. We presume the following are among the number:—Imp-erfection, imp-estuosity, imp-lacability, imp-udence, imp-ertinence, imp-urity, imp-iety.”[16]

Phelps acted as editor for several months before the appointment of Albert Carrington in the summer of 1854. Albert Carrington was a Dartmouth College graduate and rising young star in Mormonism. Carrington, like Phelps, was deft at numerous intellectual pursuits and, also like Phelps, was a noted surveyor. The two clashed somewhat. In a July 30, 1855, letter to Brigham Young, Phelps mocked Carrington behind his back: “While on the subject of wonder-working, scientific discovery, planetary rotation, and revelation, let me ask my much esteemed President, why our professor and Editor Carrington does not give a column or two in each No. of the ‘News’ of original matters of his own pericardium or pericranium, whichever is the best ‘literary depot.’”[17]

After Albert Carrington took over the Deseret News, Phelps’s contributions to the paper diminished considerably. Occasionally, he wrote news items, and certainly he was involved in weather reporting. From time to time, Phelps’s poetry appeared. He also promoted his almanac in the Deseret News. But the Salt Lake printing office eventually no longer was his base. When the church established a secular-based newspaper in 1859, The Mountaineer, to counter the non-Mormon–owned Valley Tan, Phelps was not asked to contribute. And when a vacancy arose on The Mountaineer staff and Phelps expressed his interest in a letter to Brigham Young,[18] he was denied this appointment.

Poetry in Other LDS Newspapers

In the mid-1850s, Brigham Young dispatched apostles to key United States metro centers to publish newspapers to cast a better light on Mormon beliefs, particularly plural marriage, which was considered an abomination by American Christians. Phelps sent newly composed poetry to two of those apostles—Erastus Snow, publisher of the St. Louis Luminary, and John Taylor, publisher of The Mormon in New York City.

Phelps was ever sentimental about family and learning. Erastus Snow published a reminiscence poem by Phelps entitled “I Always Loved” in April 1855. A bit about Phelps’s youth can be gleaned.

I always loved my father, who brought me into being.

To truly help him share the earth;

I always loved my mother, because she cloth’d my spirit,

And gave my body birth;

I always loved my kindred, because we play’d together,

So harmlessly in youth;

I always loved my home well, where I began to flourish,

And gather gems of truth;

I always loved my studies, for then the spirit whisper’d,

“There’s wisdom from the dead;”

I always loved my Bible, in that I got the tidings,

“All truth is from the head;”

I always loved my maker, for he begat my spirit,

And taught me how to love;

I always loved my priesthood, because its endless power,

Was perfect from above;

I always loved the women, in every stage of virtue,

With them we live again;

I always loved the union, that joins the Saints forever,

So let me love. Amen.[19]

Only a few weeks later, Phelps sent John Taylor a missive and a poem. Taylor was pleased with the correspondence and responded: “We have received the following from our old friend Judge Phelps. It is a literary curiosity, and just like the man. Who does not know or has not heard of Judge Phelps! If they have not they are behind the age, and need enlightening on this subject. Come, Judge let the quill wheel run and send us more of it.” Taylor’s lighthearted approach to Phelps stemmed from their close association years earlier at the Nauvoo printing office. Phelps called his new poem “Jerusalem.”

What glorious tidings are sounding abroad,

By angels and prophets, the servants of God;

The nations are warring, the world lives in fear;

The fig-trees are leaving, the summer is near;

Jerusalem, O Jerusalem, then

Be wise, and, like chickens, rush under the hen!

For Jacob now is like the dew from the Lord,

To mellow the tyrants that fight for reward;

And Judah, that halted at Shiloh at first,

From Gentile oppression in triumph will burst:

Jerusalem, O Jerusalem, then

Awake ye, and build up thy temple again.

The last days have come, with their terrors and tears;

The Gentiles must fall by their swords and their spears;

For Zion new rises the “kingdom to come,”

And Palestine beckons the Jews to come home;

Jerusalem, O Jerusalem, then

Arise in thy glory and splendor again![20]

Legislator

Phelps was the original Utah Territory Speaker of the House beginning in 1851. However, he only served for two years. He was replaced by Jedediah M. Grant, and later Hosea Stout served as Speaker. Yet Phelps was repeatedly nominated by church leaders and then automatically elected to be one of the representatives from Great Salt Lake County up through the seventh session (1857–1858).[21] In those early years, the term of office was only one year, not two.

Hosea Stout kept a voluminous journal with frequent references to legislative events and achievements. Stout occasionally referred to Phelps as being part of various committees, offering motions, giving speeches, and helping produce some legislation. Phelps played a major role in moving the territorial capital to Fillmore in central Utah and in conducting business there.[22] As it turned out, Fillmore was only a temporary capital.

An extant letter from Phelps to Governor Brigham Young, dated December 29, 1856, was written during the legislative session. Phelps referred to laws that he was working on to create a dam and a fishery on the Jordan River. Phelps also requested that Young appoint him notary public for Great Salt Lake County, a position that would bring him more income.[23] Young did so.

Phelps continued to serve as a county notary public through 1866. He advertised that service in the Deseret Almanac and Deseret News. In the August 1865 election, Phelps was “elected a Justice of the Peace, for the second Precinct in Great Salt Lake County.”[24]

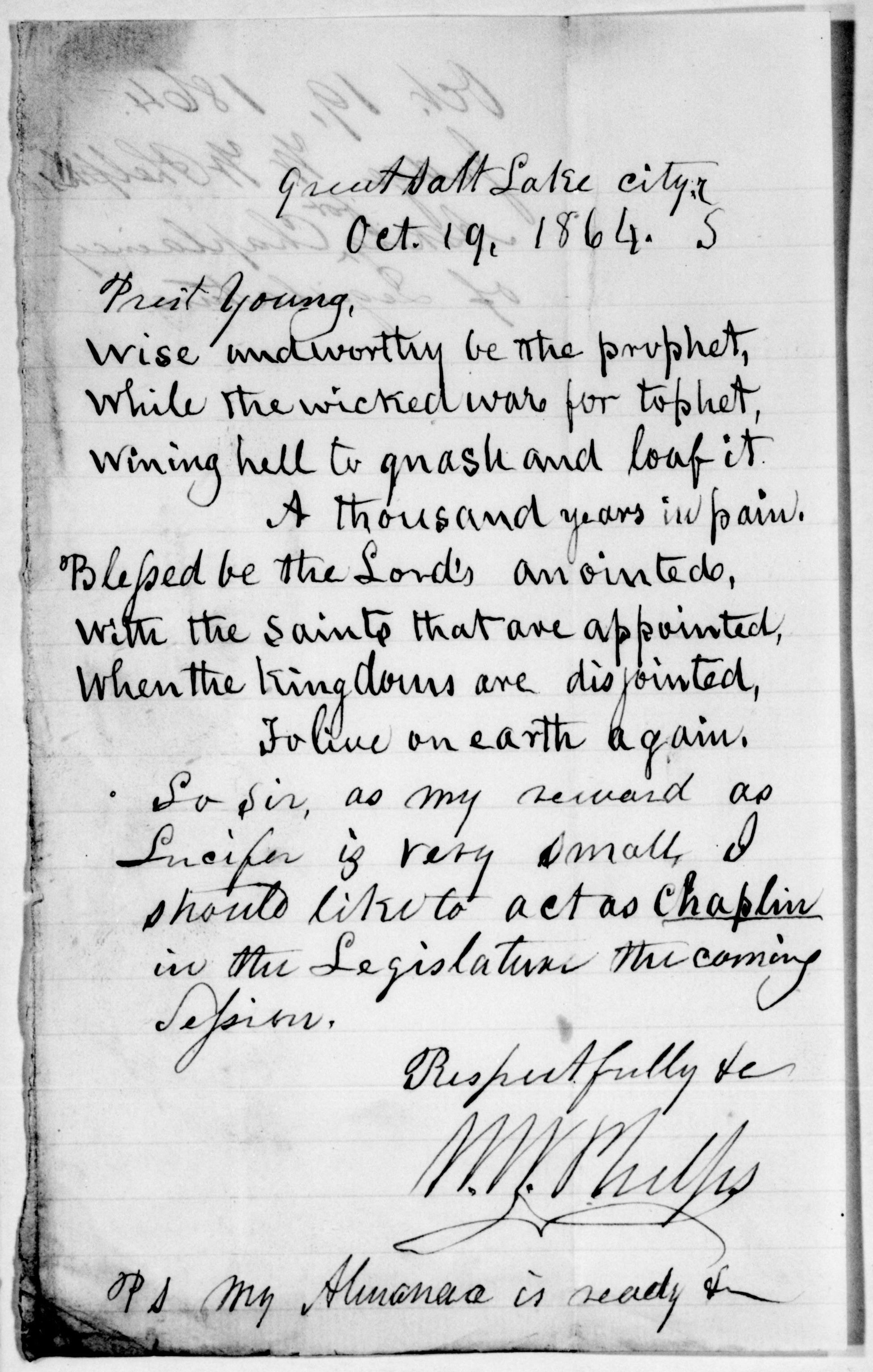

After serving in the legislature through January 1858, Phelps held another related government office, that of chaplain to the House of Representatives.[25] He officially held this position from 1859 to 1869, missing only one session. This was mostly an honorific title, but it gave some income to the Phelps family.[26] As chaplain, Phelps offered a prayer whenever the House met in session.[27] He rarely, if at all, attended the legislature from 1867 to 1869.

Weatherman

After Albert Carrington became editor of the Deseret News in 1854, Phelps reignited his interest in meteorology. He had considerably less to do at the printing office, so he threw his efforts into a new project.

Another significant impetus was the insurgent efforts of Professor Joseph Henry of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, who guided “a new phase of development for meteorology in America. . . . The heart of the project was an extensive system of volunteer observers who kept weather journals by a common plan and submitted their reports monthly by mail. . . . The Smithsonian developed and distributed calibrated instruments, standardized blank forms, uniform guidelines, and tables for the reduction of observations.”[28]

In his constant quest for more scientific knowledge, Phelps had obtained information from Professor Henry about regional weather centers. To Governor Brigham Young, Phelps wrote:

By the enclosed pamphlet you will see that a meteorological observatory for each state and territory is proposed and quite a number of respectable friends [in Utah] have proferred to help build a small building for that purpose—I thought I would solicit your advice on the subject. I have sent for an ‘inverted Telescope’; Prof. Henry writes me that the Smithsonian Institution will provide all the common instruments. . . . Such an establishment is just what I would like to superintend as I travel towards eternity.[29]

About the same time he wrote the foregoing letter, Phelps began introducing more articles in the Deseret News on weather and other climatic features. For example, after a cold, wet September storm, Phelps wrote, “Rain fell rapidly and quite steadily from about 1 to about 7 a.m., on the 10th inst. [September 1854]; showery the evening of the 11th, and a heavy rain, mingled with snow and hail, in the afternoon of the 12th. Ensign mount and the tops of the mountains east of this city were white with snow for a short time after the rain ceased.”[30] He also added long articles, some of his own writing and many from exchange papers, on meteorological facts.

Not only did he report the weather for the News, Phelps also informed readers of the Western Standard, edited by George Q. Cannon in San Francisco, about Utah’s weather:

Judge Phelps informs us that the entire fall of snow in this city, up to the 21th inst. has been over eight feet. November, December and most of January have been remarkably stormy, and many grass ranges have snowed under where heretofore but little snow has fallen. Some stock has been starved to death and some roofs crushed by the depth of the snow, a good hint to provide shelter and forage for stock and make stronger roofs.[31]

Henry Enon Phelps, Phelps’s oldest son in Salt Lake, became a faithful companion to his father in weather research. Henry provided his first “Meteorological Observations” in the Deseret News in March 1856.[32] He continued publishing these complex reports monthly over the next year. They included weather conditions and temperatures three times a day plus general comments. From 1858 to early 1860, the Phelpses provided a monthly weather column entitled “Monthly Journal.”[33]

Brigham Young and the Utah legislature did not respond immediately to Phelps’s request to be Utah’s official weatherman, but in the 1856–1857 session they created the office of superintendent of weather observations and appropriated money to the project.[34] The Deseret News announced the creation of the new territorial weather service in January 1857: “It will doubtless be gratifying to Professor Henry, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, and to all lovers of meteorological science, that the Honorable W. W. Phelps, at the request of His Excellency Governor Young, has consented, with the assistance of his son, Henry, to keep a regular set of meteorological readings.”[35] Indeed, the official weather reporting for Utah and the Smithsonian Institution for the next several years was a two-man effort of William W. Phelps and his trustworthy son Henry E. Phelps.[36]

Here is an example of the Phelpses’ frequent weather observations in the Deseret News:

The weather during the past week has been rather cool for the season, though when the wind has not blowed from the mountains, it has been warm at times. There has been some showers and the prospect for more is good. Snow has been falling in the mountains much of the time. In Springville on Tuesday week snow was six inches deep, though it was five inches deep on the bench near the mouth of South Mill Creek kanyon on Friday morning last.[37]

W. W. Phelps often referred to Utah as a “desert.” The Phelpses realized how important the winter snowfall was to required irrigation. In January 1860 they reported, “Much snow has fallen on the mountains in the northern and central parts of the Territory, enough probably to ensure plenty of water for irrigating purposes the coming summer in most locations, but in some places there is not enough yet, but doubtless will be before the stormy weather of winter and spring shall have ended.”[38]

In 1860 celebrated British explorer Richard F. Burton visited Phelps’s home and weather station on First South and noted that Phelps, a “meteorologist,” had a weathercock mounted on the top of his house upon which was printed a passage from Job 38:35—“Canst thou send lightnings, that they may go, and say unto thee, Here we are?” Phelps also showed Burton his invention of a “magnetic compass.”[39]

Once each month in the 1860s, the Deseret News generally printed a weather report of “meteorological observations” for the previous month as compiled by Phelps. This column, entitled “Abstract,” continued through August 1866. His columns reported constantly on precipitation because of water needs in arid Utah.

Scientific Advancement

Phelps, among so many other things, considered himself a scientist. In Utah he continued to read widely and published scientific discoveries that he drew from exchange newspapers in the Deseret News and his Deseret Almanac. He particularly heralded the quest for new knowledge provided by the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.[40]

Phelps’s conviction that he was likely the most learned man in the church is evident in a Wilford Woodruff journal entry: “Presidet Young Askes Wm. W Phelps if Asstrology is true. Phelps says I don’t know. BY. Brother Woodruff write that down. This is the first thing that I ever heard off but what Brother Phelps knew.”[41]

Phelps attended and occasionally participated in the weekly Deseret Theological Institute meetings. The mysteries of theology and the universe, as well as choir performances, were regular fare. For example, we read in the Deseret News that in one of the meetings Henry Maiben, a well-known Utah singer, sang “a new son[g], about Father Adam and Mother Eve, composed by W. W. Phelps.”[42]

Phelps attended and in many ways guided the proceedings of the Deseret Typographical Association. This association promoted the press as a means to build the kingdom of God and on one occasion encouraged the Deseret Alphabet: “On motion a committee of three was appointed to draft resolutions expressive of views of this Association relative to the Deseret Alphabet. Said committee to consist of Elders George D. Watt, W. W. Phelps, and Jas. McKnight.”[43] George Q. Cannon reported in his Western Standard in San Francisco regarding an annual festival sponsored by the typographical association: “Several songs composed for the festival by Messrs. Phelps, Davis, Lyon, Maiben, and Mills were sung, and dancing was entered into with a zest and hilarity characteristic of the Deseret typos.”[44]

When the Universal Scientific Society was created in 1855 to provide “lectures and essays of every branch of useful arts and sciences,” Phelps was designated “Assistant Corresponding Secretary.”[45]

Phelps also participated in the Deseret Horticultural Society, which was created in September 1855. Throughout his life, he had advocated the planting, nurturing, and harvesting of appropriate fruits and vegetables as well as advocating beautifying the earth with glorious flowers. The Deseret News reported: “Hon. W. W. Phelps rejoiced that we can now see the fruit of the earth raised by ourselves. In seven years from to-night, we can compare with any fruit culturists on the earth.”[46] Evidently, the Phelpses produced a productive garden. The Deseret News observed, “A water melon of the Valley Green species, was raised this season, in the garden of W. W. Phelps, which measured 19 1–2 inches in length, 31 1–4 inches round, and weighed 30 pounds. The flavor was, it was said, equal to a pine apple.”[47]

In 1859, in his position as Utah’s meteorologist, Phelps sent out the following plea: “The Smithsonian Institution wishes to collect the ‘nests and eggs’ of all the various feathered tribes, or fowls and birds common to Utah. . . . The history, habits, and time of nesting of both birds and fowls must accompany the eggs. Birds’ heads and wings can be preserved in alcohol. . . . [Those who] bring or send them to me, shall be remembered when literary favors are distributed.”[48]

Phelps occasionally reported brilliant sights in the night skies in the News. For example: “On Sunday evening, the 28th ult. [August 1859], a beautiful display of aurora borealis, or northern lights was observed in this city between 9 and 10 p.m.; a palish light wavered up about 30 degrees towards the zenith, giving the ‘Great Bear’ or ‘Dipper’ quite a silver hue; thence it began to spread east and west with increasing grandeur.”[49]

Exploring on Weber River

In 1857, when Phelps was at the peak of his value to Deseret as Utah Territory’s weatherman, Brigham Young charged him to lead another exploration in quest of a new settlement. Phelps, sixty-five at the time, still was sufficiently vigorous to lead an expedition. He was trusted with this endeavor as he had been earlier in helping lay out previous church settlements in Jackson County, Missouri, in 1832, when he was forty; in Clay County, Missouri, in 1833 and 1834, when he was forty-two; in Caldwell County, Missouri, in 1836 and 1837, when he was forty-four; and in southern Utah settlements based on the Southern Exploration Expedition in 1849 and 1850, when he was fifty-seven. This time he was assigned to go into the mountain ranges far up the Weber River in present-day Summit County, Utah. He brought to this task his vast experience with topography, surveying, meteorology, agronomy, and climatology. He reported his experience on May 20, 1857, in the Deseret News:

Week before last I made a trip to Weber River, in company with 28 men, one boy and a woman,—30 in all. I went for the purpose of laying out a Fort and farming land on said River, below Kamas prairie, or Rhoad’s [actually Rhodes’] Ranch, some six or eight miles north, and between 30 and 40 from this city in a south-easterly direction. I surveyed between 20 and 30 lots of from 10 to 22½ acres each, of tolerable fair appearance for grain and meadow land.

The altitude and climate show two or three weeks later vegetation than our Valley, but the signs for wheat, barley, oats, peas and potatoes, with grass and range for stock, are fair, and the soil good: together with stone quarries, adobie clay, timber, and water in abundance. . . .

The place was dedicated, as all the earth will eventually be, for the benefit of Israel, and whosoever lives there, must live by faith and works, in spirit and in truth, for no one else can hope to live there on any other principle.[50]

It turns out that these first settlers returned to Salt Lake in the fall of 1857 because of the approach of Johnston’s Army, but most returned in 1860 and established the village of Peoa. Phelps chose the name during the original exploration after he and the settlers found a log with the name PEOHA carved on it, perhaps from some Native American or trapper.[51] Throughout its history, Peoa has remained a small agricultural community.

Translator

Throughout his life, Phelps dabbled in myriad foreign languages, and he made what he considered a more detailed study of Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. He also felt that he had a spirit of revelation pertaining to other tongues.[52] Hence, in Utah he often put himself forward as a translator. His translations tended to be of biblical chapters pertaining to the redemption of Zion in the last days.

One of the most curious aspects of Phelps’s eccentric personality was his insistence that he was gifted in understanding ancient languages. For example, reporting a “Seventies’ Hall Lecture” in 1862, the Deseret News stated: “Professor Phelps followed with a short address upon the new translation of Joseph Smith, and read several extracts . . . having particular reference to the building up of the kingdom of God on the earth in the dispensation of the fullness of times. Said he had compared all these selections with the original Greek, Hebrew, and Chaldaic and found them to be correct renderings.”[53] In his almanacs, Phelps identified himself as “Translator of Oriental Languages.”[54]

Remarkably, Phelps penned a poem in 1863 that he claimed to be a translation from the Hebrew. In reality, it is a poetic rendition (that he hoped would be sung) of his doctrinal interpretations regarding an infinite eternity, plurality of Gods, multiple wives for righteous men, supremacy of northern hemisphere inhabitants, and the temple endowment.[55]

David’s Psalm 48

Translated from the Hebrew, by W. W. Phelps.

(A nice song for sweet singers.)

The Lord is great and glorious too,

Within the city, where

All cov’nants made are kept as true:

That holy mountain there.

In beauty high fair Zion stands,

The sacred place of joy,

For all the earth, where truth expands,

Without the least alloy.

’Tis in the northern hemisphere,

Where choicest singers sing,

Indu’d with ev’ry grace that’s dear,

The city of the king.

In her great temple of the Lord

The Gods will be endowed

For exaltation and reward,

Beneath the curtain cloud.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Just as we understand by truth,

Our happiness will be;

As if we held eternal youth

Throughout eternity.

There Lords and Gods, and kings and queens,

Are in perfection free,

To plan new worlds, by ceaseless means,

For their posterity.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

By cov’nants of the Saints, endow’d,

All Zion will be one,

As Israel, clean, beneath the cloud,

Are greeting Christ, the Son.

No pain, or sorrow, will be known,

Among her shining tow’rs;

For Satan’s bound—down with his own,

And Death hath lost his pow’rs.

O! who can count all Zion, then,

Or what is yet to be?

Gods! wives and children! pure as when

They star eternity.

Not surprisingly, Phelps inserted into his “translations” doctrines as he understood them from the Book of Abraham. Below are two verses from Phelps’s translation of Daniel’s interpretation of Nebuchadnezzar’s dream of the great tree.[56]

| King James Version of Daniel 4 | Phelps’s Translation of Daniel 4 |

| 25. That they shall drive thee from men, and thy dwelling shall be with the beasts of the field, and they shall make thee to eat grass as oxen, and they shall wet thee with the dew of heaven, and seven times shall pass over thee, till thou know that the most High ruleth in the kingdom of men, and giveth it to whomsoever he will. | 22. [Phelps’s verse numbers differed from the King James.] They will drive thee from men, and thou must dwell with the beasts of the field; and thou shalt graze grass as an ox; and the rain of heaven shall fall upon thee, till two thousand, five hundred and twenty years[57] shall have passed over thee, until thou hast learned that the Most High rules among the kingdoms of men, which are set up to be true. |

| 26. And whereas they commanded to leave the stump of the tree roots; thy kingdom shall be sure unto thee, after that thou shalt have known that the heavens do rule. | 23. And also, they say the roots of the stump shall be left, that the tree of thy kingdom may remain for thee, after that thou shalt have learned the full power of heaven.[58] |

Phelps translated not only the foregoing biblical passages but also numerous others as found in letters to Brigham Young, in Deseret News articles, and in the Deseret Almanac. He indicated that he was influenced by the Hebrew translation of the Bible by Johannes David Michaelis, a noted German biblical scholar and teacher. In these translations, Phelps again emphasized his favorite doctrines.[59]

Phelps’s most unusual translating activity was described sarcastically by T. B. H. Stenhouse: “[Phelps] is a singular genius, gifted in interpreting disentombed descriptions, especially upon old coins.”[60] For example, the Deseret News reported that a Manti man discovered on the banks of the Colorado River an old copper coin with hieroglyphics and purported “Hebrew letters.” The coin was taken to “Professor Phelps,” who was pleased to render a literal translation of the characters. He stated that the coin was 1,765 years old and was likely “a Nephite Senine or farthing.”[61] On one side of the coin was a greeting from a Nephite king named “Hagagadonihah.” The inscription on the other side read, “In the 95th year of the Kingdom of Christ, 9th year of my reign: Peace and life.”[62] Phelps also claimed to be able to translate the Hebrew characters from an imitation of a “holy stone” found near Newark, Ohio. He ascertained that the stone had been deposited by Nephites approximately 1,600 years earlier and referred to holy endowments.[63] These “translations” showed both Phelps’s devotion to the historicity and truthfulness of the Book of Mormon as well his megalomania brought on by his advancing age. In his increasing delusion, he actually likely believed that he possessed extravagant spiritual translation powers.

Endowment House

Inasmuch as Phelps had served as an ordinance worker in the Nauvoo Temple, primarily in the role of the serpent/

In November 1852, William and Sally Phelps were present in the special “temple room” of the President’s Office along with several other leading brethren and their wives in a prayer, anointing, and testimony meeting.[64] This type of meeting was typical, and since Phelps was part of the “Quorum of the Anointed” that originated in Nauvoo, he was a participant. Some few Saints were also endowed in this temple room with Phelps presumably performing his specific role.

The First Presidency directed that an enormous temple be constructed at Temple Square, but because it would take many years to complete, they decided to prepare a “temporary temple” on the same block that was to be called the “Endowment House.” It was constructed out of adobe and lumber and had all the necessary rooms and accoutrements of a regular temple. Only a year was required for the construction.

The dedication took place in May 1855. The First Presidency and four apostles were in attendance along with five other temple workers, including W. W. Phelps. President Young declared the Endowment House “The House of the Lord.” Five brethren and three sisters received their endowments that day, and Phelps performed the role of the serpent.[65] The First Presidency then invited Saints throughout Utah to prepare themselves for the endowment and to plan specific excursions to Salt Lake. Endowment ceremonies that involved Phelps took place generally one or two times a week over the next several years. Phelps was actively engaged until 1866.[66]

Phelps’s reputation for acting out his serpent’s role increased. Noted comedic actor and travel narrator Artemus Ward from Britain noted from his extended visit to Salt Lake City: “There is an eccentric Mormon at Salt Lake City of the name of W.W. Phelps. . . . It is said he enacts the character of the Devil, with a pea-green tail, in the Mormon initiation ceremonies.”[67] Fanny Stenhouse, a once-faithful Mormon who left the church with her husband, wrote of her Endowment House experience. In it she described Phelps: “Phelps used always to personate the devil in the endowments, and the rolé suited him admirably. . . . The curse was now pronounced upon the serpent—the devil—who reappears upon his hands and knees, making a hissing noise as one might suppose a serpent would do.”[68]

Phelps’s need for a new costume for use in the Endowment House in the twilight of his career is seen from his 1864 letter to Bishop William Miller, the church’s bishop for all temporal affairs in Utah County:

I have worked, (since we commenced in Nauvoo,) in the endowments. And once in a while I need new clothes to work in. I want the good Saints of Provo, and Springville to get me up six and a half yards of nice blue or dark mixed Jeans for a coat and pants for the old fellow to act in. . . . I am nearly 73 years old, and all of your good Saints, of or near that age, will join with me in saying—the tree is known by its fruit. I hope to enjoy the next half of my life, or the rest of it, on the land of Zion according to revelation.[69]

A goodly number of Latter-day Saints in Utah from 1855 to 1866 remembered Phelps mostly for his acting role as the serpent/

Thoughts about the Civil War

The War between the States took place from 1861 to 1865 and resulted in more than six hundred thousand deaths. Only a mere handful of Latter-day Saints suffered casualties. The war was far away from the Saints’ new home in the Rocky Mountains. Yet Mormons had reasons to be interested. Based on his lengthy journalism career, Phelps, as would be expected, expressed his interest in this war. To him it was a millenarian sign of the times.

Phelps’s Almanac in 1861, 1862, and 1864 contained pieces regarding the terrible war. Phelps inserted “A Revelation and Prophecy by the Prophet, Seer, and Revelator, Joseph Smith,” known later in Mormon lore as the “prophecy on war” (D&C 87). “Verily thus saith the Lord, concerning the wars that will shortly come to pass,” stated the prophecy, “beginning at the rebellion of South Carolina, which will eventually terminate in the death and misery of many souls. The days will come that war will be poured out upon all nations, beginning at that place; for behold, the Southern States shall be divided against the Northern States.” The prophecy also spoke of slaves rising up against their masters and that famine, plague, earthquake, and fierce lightning would follow and cause the earth’s inhabitants to mourn.[70] The contents of this prophecy were new to most Saints in 1861 because it had not been published in either the 1835 or 1844 editions of the Doctrine and Covenants.[71] On October 9, 1860, Phelps went into Brigham Young’s office and “made a statement about the revelation which Says the Southern States shall be divided against the North. He said after this revelation was given it was locked up in a desk. . . . Joseph prayed and afterwards ascertained from the Lord that he did not want it published just then.”[72] By printing this revelation in his Almanac, Phelps contributed to his contemporaries an understanding of a Joseph Smith prophecy that would later become well known and frequently cited in the church.

Phelps printed this war prophecy again in the 1862 almanac along with portions of a significant revelation to Joseph Smith (now D&C 101:85–95) that appeared to prophesy of the Civil War.[73] The revelation stated that if the Saints’ petitions to the courts, the governor, and the US president for redress of grievances in Missouri went unheeded, the Lord in his fury would vex the nation and “cut off the wicked, unfaithful, and unjust.”[74] Phelps knew this revelation well because in the 1830s he gave his all to fulfill its commands.

In his 1864 almanac, Phelps once more published Joseph Smith’s prophecy on war and included with it a reprint of “A Friendly Hint to Missouri” that Phelps had ghostwritten for Smith “twenty years ago.” In this essay, Phelps urged peaceful resolutions to horrible conflicts and attributed it to Joseph Smith even as he had done in 1844.[75]

Phelps’s letters to Brigham Young considered war issues. In 1861 before the war even started, Phelps provided a version of Zechariah 2, based on Johannes Michaelis’s translation, that referred to wrath coming from “the north” and stated that a certain people would “become prey of their slaves.” Phelps predicted, “By 1866, these ‘slaves’ will have a holiday as wonderful as their masters now have. ‘Sic transit gloria mundi’ [so the glory of the world].”[76]

In a subsequent letter to Young, explicitly written on Phelps’s seventy-first birthday, Phelps prophesied in verse that the United States would soon fall apart and die. The first two of six stanzas:

The United States is as dim as the gloom

Of a meteor’s flash or the gleam of a flame;

And the death knell and wail, from the hearthstone and tomb,

Put an end to the echo of “Freedom and fame.”

The trumpet of war sounds to arms! rush to arms!

And two nations—‘once one’—shout for “vic’try or death”;

While their armies, for armies, with Lucifer’s charms,

Use the “new patent method” to draw their last breath.[77]

Phelps was called on to speak in the April 1864 general conference. He emphasized that “the nations of the earth were at war and vied with each other in the manufacture of the most powerful engines of human destruction.” There “would be no peace but in Zion,” he asserted. People must not take up the sword against one another, he added, but should flee to Zion. He exhorted the Saints to do right and be ready for the hour when “the thief cometh.”[78] Four years later, having been relieved of official duties, W. W. Phelps offered an opening prayer in the church’s April 1868 general conference.[79]

A Letter from W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young.

A Letter from W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young.

Letters to Brigham Young and Others

In the 1850s and 1860s, it was common for busy men to communicate with others by letter, even if the receiver of the message lived nearby. Numerous Phelps letters of this kind to Brigham Young exist. Other Phelps letters also exist.

The letters to President Young usually dealt with Phelps’s impoverished condition after businesses started to thrive in Salt Lake City and the economy changed. Phelps could no longer sustain himself with home gardens and with contributions from the church, as had been the case earlier in Missouri, Ohio, and Illinois. He wrote pleadingly to Young many times. One plaintive excerpt follows:

During the past twenty years of your administration in this church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints, I have labored faithfully in the endowments, and other wise for the benefit of the Kingdom. As legislator, chaplin, clerk of the weather, &c, I have served the public, all of which has yielded me a tolerable support; that is my three wives and children and self for food and raiment.

For services in the endowments I received about $240 per annum for several years; lately that sum was reduced to $120. To meet that deficiency this year I sold my ten acre gross lot, but as I have no more lots to dispose of, and my horses, mules, and sheep have been taken by guerillas or doe heads [traitors], I would like to have the $120 restored to the original $240.[80]

Phelps also appealed to Daniel H. Wells and George Q. Cannon in the President’s Office to provide opportunities for additional remuneration for services. He emphasized that “for 28 years I have stood my ups and downs to the tune of many thousands [of dollars].”[81]

Phelps wrote a letter to an earlier close friend, John Whitmer, in 1859. His purpose was to ask Whitmer if he still had manuscripts of Joseph Smith’s “translation” of the first chapters of Genesis (now recorded in LDS scripture in the Book of Moses). Phelps confessed that he had lost some of his manuscripts. He promised to compensate Whitmer for copies of his manuscript. Phelps testified as well: “Mormonism, being founded in truth, has become great and will spread round the world and no power of man is able to frustrate its onward march.”[82] No record exists of any response from Whitmer.

Phelps Family

William and Sally Phelps had only marginal success raising their seven living children, that is, according to typical Latter-day Saint standards, those same lofty standards that Phelps so often wrote about in Mormon newspapers. Phelps was likely more responsible than Sally was for any negative attitudes their children possessed. His puritanical firmness about standards and his various eccentricities may have contributed to five of the children ultimately choosing other paths than Mormonism.

William and Sally’s three oldest daughters—Sabrina, Hitty, and Sarah—married men who had no interest in the church; these couples remained in the American Midwest with their families and posterity. Waterman, the oldest son, was sealed to Lydia Brewster in the Nauvoo Temple, but when thousands of Saints headed west, Waterman, Lydia, and their children took up residence in Fort Madison, Iowa, not far from Nauvoo across the Mississippi River. They came west in 1852,[83] but they decided not to stay in Salt Lake and went on to Placerville in California gold country. Waterman’s descendants have not been affiliated with the Mormons.

Henry Enon, the second son and fifth living child, turned out to be the most loyal and well-known Latter-day Saint of William and Sally’s children. He served a mission to Great Britain in 1854–1855. Upon his return, he aided in his father’s quest to become Utah Territory’s weatherman. Henry was endowed in the new Endowment House on September 7, 1855. Throughout the 1850s and 1860s, Henry assisted his father in preparing weather data for the Smithsonian Institution, the Deseret Almanac, and the Deseret News. On Main Street in Salt Lake City, Henry set up a dry goods store.[84] He remained a bachelor for many years, but in 1863 he married seventeen-year-old Mary Catherine Meikeljohn, who had recently emigrated from Scotland. He was thirty-five. Henry and Mary were sealed in the Endowment House in 1865. They raised nine living children in the faith.[85] Henry did not marry polygamously. A majority of the Phelps descendants who promote W. W. Phelps’s memory come from Henry and Mary.

The Phelpses’ next child was James. Not much is known about him. In a letter to his parents from Carson Valley (in present-day Nevada but in Utah Territory in 1853), he reported his experiences of driving cattle under the direction of Howard Egan.[86] He was called in 1855 as a twenty-three-year-old to the Australasian Mission (comprising Australia and New Zealand).[87] He first labored in New Zealand. A subsequent published report from this mission stated that he was assigned to the Australian province of Victoria.[88] He never returned to Utah from his mission.[89] The Australasian Mission history states that James left his assignment on May 10, 1857, just days after first arriving in Victoria, without “proper release.”[90] He never returned to Utah. No further definitive information exists on James.

William and Sally’s last surviving child was Lydia, who at sixteen married Thomas S. Williams, a Mormon Battalion veteran, as a plural wife in 1851. In 1852 she gave birth to Princetta, who was named after Lydia’s deceased younger sister. (Princetta Williams remained a faithful Mormon in Utah and Idaho and had a large posterity.) Thomas Williams, a merchant in Salt Lake City who opposed Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball’s tight controls, was excommunicated during the 1856 Reformation. Thomas and Lydia’s marriage ended in divorce.

Lydia then married widower and father of two Jeremiah Varney (who had assumed the name of Theodore Thorpe, one of his mining coworkers who had died) in November 1856. The couple had six children, three sons and three daughters, before Jeremiah’s death in 1869 from a mining accident. The children assumed the Varney surname, but Lydia went by Thorpe after her husband’s death. Lydia Thorpe was one of the first teachers in the church’s first Sunday School organization in 1861 in the Fourteenth Ward.[91] She remained true to her faith throughout her life. Lydia’s descendants also herald their Phelps heritage.

W. W. Phelps had to care in his older age for two additional families—from two plural marriages that appeared to be successful. In some form or fashion, as reported in earlier chapters, Phelps had married five other women, but those marriages did not last for more than a few days or weeks and certainly could not be considered successful.

Sarah Gleason Phelps, whom William had married in Winter Quarters in December 1847 and to whom he was sealed in 1852, remained a loyal plural wife. She and her children resided in a house immediately adjacent to Sally’s house on the corner of West Temple and First South in Salt Lake City. Sarah lost her first child, son Gleason, to death at age three in 1853. She gave birth to daughter Ellen Cleary (“Nellie”) Phelps in 1853 and son Enon Gleason Phelps in 1858. Sarah lived until 1916 and passed away in Salt Lake City.[92]

In September 1856, Phelps married a newly immigrated widow, Harriet Henrietta Schrader, in the Endowment House. She already had nine children that she brought from Philadelphia to Utah shortly after her first husband died. Conceivably, Brigham Young charged Phelps to marry this widow plurally.[93] Phelps supported Harriet and her children, who lived on the Phelps property. William and Harriett had no children together. Harriet died in 1892 in Salt Lake City.

Death

William W. Phelps firmly believed that Joseph Smith had promised him and Sally that they would never taste of death.[94] This promise may have come up in private conversations between Smith and Phelps. Another possible source for this belief comes from a blessing given to Phelps on September 22, 1835, in which Smith stated, “His days shall be prolonged upon the land of Zion; and when he is old and bowed down with many years, behold, he shall lift up his eyes and the heavens shall be opened upon him. He shall be lifted up at the last day, and his rest shall be glorious.”[95] The patriarchal blessing that Joseph Smith Sr. pronounced upon Phelps was a third possible source. The elder Smith promised, “Thou shalt see the city of Enoch and shalt gaze upon in all its glory: yes, thou shalt be exalted to the heaven.”[96]

Phelps interpreted these prophecies to mean that he would not taste of death and would be caught up to heaven immediately at the Second Coming. He loved the many promises given by his hero Joseph Smith and rewrote the 1835 prophecy about himself in full in an 1857 letter to Brigham Young.[97]

In an 1863 letter to George Q. Cannon, who was then serving as European Mission president, Phelps wrote, “I shall be 71 years old one month from today and I can say without the fear of contradiction that the past year has been one of the happiest of my life, without pain or sickness, and according to the revelation of Joseph, I expect to live the next 70 years, improving on the past and then may be ‘caught up & changed in the twinkling of an eye.’”[98]

No wonder, then, that Phelps often wrote poetically and in prose about the fears and challenges of death—he thought he would not have to endure them. For example, in the 1862 almanac, Phelps declared in poetry that “all but me” would be claimed in death, and the “good old world” was soon to pass into oblivion.[99] In 1864 he wrote in “The Tombs” his condolences to those who must die: “And yet all flesh is keen to shy it, / And would, by wealth and art, defy it; / But down they go among the tombs.”[100]

T. B. H. Stenhouse, a one-time faithful Mormon who turned against Brigham Young and the church, noted in his memoir: “The career of ‘W. W.,’ as he is familiarly styled, has been somewhat chequered, but he lives and is ‘not to taste of death.’ He is about eighty years of age and has the promise of living till Jesus comes again.” Before he published his volume, Stenhouse added a postscript regarding Phelps: “Alas, poor Phelps! Often did the old man, in public and in private, regale the Saints with assurance that they had the promise by revelation that he should not taste of death till Jesus came. The last time the author spoke with ‘Brother’ Phelps, the latter was fully satisfied that the revelation of Joseph Smith could not fail in its fulfillment.”[101]

A long-time friend of the Phelpses, Oliver Huntington, explained how this prophecy was indeed fulfilled:

The manner of the fulfillment of that promise is rather singular. They supposed, and so did all that knew of the promise, that they were to never die, but the Lord does business in his own way and his way is not as the way of a man.

Before Brother Phelps died he lost all his judgment, lost all his mind, reason, consciousness and all sense. He knew nothing, not even his name, nor how to eat, thus being unable to taste of anything; not even death. His mind gradually dwindled, withered and dried up.[102]

Phelps’s death occurred Thursday morning, March 7, 1872, at 2:00 a.m.[103] A daily newspaper promoting Mormon interests called The Salt Lake Herald came into being in 1870. The Herald wrote an appropriate obituary:

The death of Mr. W. W. Phelps, well known to the community as Judge Phelps, at the ripe age of eighty years, is announced under the proper heading under this morning’s HERALD. Mr. Phelps’ career was in many respects a remarkable one. He was early identified with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and, soon after its organization assumed editorial functions connected with the propagation of its faith. He was a man of decided literary tastes, and in a long life had acquired a large and varied amount of knowledge which he had the faculty of presenting in a peculiarly piquant and original manner. For a few years past his vigor of mind and body has been failing, and his death does not come as altogether unexpectedly, for at an age such as he attained few can be expected to linger on much longer. He was widely known, and had a large circle of friends, who will miss his pleasant manner and quaint sayings.[104]

On March 10, 1872, the Herald reported on his funeral:

The obsequies of Judge Phelps yesterday, at the 14th ward assembly rooms, was largely attended by friends of the family and those who had been acquainted with the deceased for many years. Addresses appropriate to the occasion were delivered by Elder John Taylor, Elder Wilford Woodruff, and [Presiding] Bishop [Edward] Hunter and the body was followed to its last earthly resting place [in the Salt Lake City Cemetery] by a numerous cortege.[105]

The newly established Salt Lake Tribune, anti-Mormon in nature, published the following the day after Phelps expired:

Death of Judge Phelps.—This very aged and noted man in Mormondom died yesterday morning at his residence in this city. For a considerable time he has appeared very feeble though he continues to walk about the streets. Judge Phelps was upwards of eighty years of age and has been a conspicuous man in the Church for forty years. He has figured somewhat as a literary man, being at one time an editor, and the author of a number of the Saints’ hymns, and a publisher for many years of the Deseret Almanac.[106]

Wilford Woodruff recorded in his journal for March 9, 1872:

I Attended the funeral of Brother Wm. W Phelps who died on Thursday night March 7, 1872 Aged 80 years & some months. He was Baptized in kirtland Ohio in 1831. He has been in the Church over 40 years. He has been a vary P[eculia?]r Man in many respects. He has been the Author of many of the most Choice hymns published by the L. D. Saints. He was publishing a paper when He Came into the Church & He Published the first Paper in the Church the Evening & Morning Star. He left the Church with many others in the difficulties in far west But finally returned to the Church in Nauvoo & [has] been in Ever since. Has been with Joseph a good dele & has written for him. He has labored in the Endowment House for many years. For the last year of his life he has not been Capable of doing any business.[107]

Sally Waterman Phelps, like her husband and eternal companion, did not “taste of death” in a normal fashion. While standing on a bridge over a ditch in Salt Lake City on January 2, 1874, a roof blew off a building and struck her in the neck, killing her instantly.[108] She was seventy-six. By all accounts, Sally was a remarkable woman who sacrificed immensely for her faith, her husband, and her children. Not the least of her challenges, as was the case for thousands of other Mormon women, was her husband’s plural marriages.

As with most people, W. W. Phelps’s death and that of Sally were anticlimactic compared with the adventures of their earlier lives.

Notes

[1] The Deseret News reported regularly on general conference sessions and often recorded Phelps’s participation. However, the paper did not report on a special conference held on June 27, 1854, on the tenth anniversary of Joseph Smith’s martyrdom. Phelps is recorded to have offered a “singing prayer” as an invocation for that meeting. LaJean Carruth, a trained shorthand expert in the Department of Church History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Salt Lake City, Utah, transcribed the conference proceedings on June 16, 2010. Phelps’s last known participation in general conference was October 9, 1865. In records not found in the Deseret News, Phelps is recorded as reading a hymn and telling an “anecdote” at the beginning of the conference session. Brigham Young gave the first address and spent many minutes contradicting Phelps’s account of the calling of the original Twelve Apostles in 1835. He belittled Phelps’s tendency to exaggerate his own importance. However, Young also acknowledged that Phelps had positively contributed to the general understanding of the Saints in the first session of the conference by drawing from a Greek rendition of the New Testament to testify that God has a body, is not merely a spirit, and therefore is an exalted man. Brigham Young, October 9, 1865, MS 4523, box 4, disk 3, 1865b, images 80–82, 89–95, LaJean Carruth transcription, February 6, 2012.

[2] K. J., “Almanac,” Deseret Almanac (1860), 32. Noted British adventurer, explorer, and travel chronicler Richard F. Burton wrote of spending a day with Phelps and receiving from him the recently published 1860 Deseret Almanac. Burton cited this same Phelpsian statement about almanacs and described the contents of the 1860 almanac. Richard F. Burton, The City of the Saints and Across the Rocky Mountains to California (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1862), 253–54.

[3] David J. Whittaker, “Almanacs in the New England Heritage of Mormonism,” BYU Studies 29, no. 4 (Fall 1989): 90. Whittaker also provided a historical narrative about Mormonism’s earliest almanacs between 1845 and 1849, produced by apostle and missionary Orson Pratt. See pp. 94–99.

[4] As noted previously, Phelps took an anti-astrological stance in his early almanacs. But with Brigham Young’s insistence, Phelps acquiesced and started including astrological tables. See Whittaker, “Almanacs in the New England Heritage of Mormonism,” 99–100, 103, 103n50; D. Michael Quinn, Early Mormonism and the Magic World View (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1987), 215–16.

[5] These examples come from the Deseret Almanac (1862), 22–23. Phelps likely obtained his information from both experience and his vast reading, including other almanacs.

[6] In a letter to Brigham Young in 1859, Phelps remembered the “experiment” he had made in the 1855 almanac to provide advertising, which resulted in more money for Phelps. Now in his old age, Phelps felt he needed further “pecuniary help,” so he asked permission of Young to solicit many advertisements. W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, February 11, 1859, Brigham Young Papers, CHL. Sure enough, the 1860 almanac came out with a plethora of advertisements for “merchants and mechanics,” as did his almanacs for subsequent years.

[7] Peter Crawley, ed., A Descriptive Bibliography of the Mormon Church (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1997), 3:109; W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, September 9, 1856, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[8] “The King’s Jester’s Soliloquy,” Deseret Almanac (1854), 6, 8; emphasis in original.

[9] “To Mormon Wives,” Deseret Almanac (1854), 8; emphasis in original.

[10] “Model Poetry,” Deseret Almanac (1860), 32.

[11] “Joseph Smith’s Last Dream,” Deseret Almanac (1863), 27–28.

[12] See, for example, Seth Adam Smith, “Symbolism and Meaning in Joseph Smith’s Last Dreams,” YouTube, August 26, 2011, https://

[13] W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, September 9, 1856, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[14] W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, December 12, 1865, and October 22, 1866, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[15] W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, March 20, 1866, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[16] Deseret News 4, no. 21 (August 3, 1854): 74; emphasis in original.

[17] W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, July 30, 1855, Brigham Young Papers, CHL; underlining in original.

[18] W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, June 26, 1860, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[19] W. W. Phelps, “I Always Loved,” St. Louis Luminary 1, no. 21 (April 14, 1855): 83.

[20] “Salt Lake Correspondence from Judge Phelps,” The Mormon 1, no. 22 (July 21, 1856): 3.

[21] “Territory of Utah Legislative Assembly Rosters, 1851–1894,” Utah Division of Archives and Record Service, updated December 28, 2007, https://

[22] Juanita Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier: The Diary of Hosea Stout, 1844–1861 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press and Utah State Historical Society, 1964), 2:402, 404, 421, 424–25, 524, 533, 535, 542, 547, 549, 559, 569–70, 576–77, 599, 610, 613, 617, 622, 635. See also “Resolution and Acts of the Territory of Utah” (1856–1857), Utah State Historical Society, 14–15; Crawley, Descriptive Bibliography of the Mormon Church, 3:178–79, 181, 254.

[23] W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, December 29, 1856, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[24] WWPP. This came from a certificate signed by Governor Amos Reed.

[25] Phelps continued to beg Brigham Young that he be allowed to continue as chaplain because he needed the income desperately. See W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, October 19, 1865, and October 22, 1866, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[26] “Territory of Utah Legislative Assembly Rosters, 1851–1894.” When the shadow State of Deseret legislature met in April 1862, Phelps was also the chaplain of the House. “State of Deseret,” Deseret News 11, no. 12 (April 16, 1862): 332. Phelps was identified as chaplain for the 1868–1869 session in “Legislative,” Deseret News 17, no. 49 (January 13, 1869): 338.

[27] W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, October 30, 1858, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[28] James Rodger Fleming, Meteorology in America, 1800–1870 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990), 75. Fleming also included Phelps’s brief biography in his appendix containing all Smithsonian observers. See pp. 180–81.

[29] W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, September 26, 1854, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[30] “The Weather,” Deseret News 4, no. 27 (September 14, 1854): 97. On this same page, Phelps wrote an article entitled “Formation of Dew.”

[31] “Snow,” Western Standard 2, no. 2 (March 20, 1857): 2.

[32] Henry E. Phelps, “Meteorological Observations for February 1856,” Deseret News 5, no. 52 (March 5, 1856): 416.

[33] The first of these was for January 1858 in “Monthly Journal,” Deseret News 7, no. 48 (February 3, 1858): 884.

[34] Glen Conner, “History of Weather Observations, Salt Lake City, Utah: 1857–1948” (report prepared for the Midwestern Regional Climate Center under the auspices of the Climate Database Modernization Program, NOAA’s National Climatic Data Center, Asheville, NC, November 2005), 2.

[35] Deseret News 6, no. 44 (January 7, 1857): 5.

[36] For example, under Henry E. Phelps’s name the first month’s official and thorough weather report in chart form was printed in the Deseret News 6, no. 44 (January 7, 1857): 8. The chart contained temperature readings for different times of the day and daily general observations such as “6 inches of snow fell.” For a request by Phelps that his son Henry be completely involved with the weather service, see W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, March 31, 1857, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[37] “The Weather,” Deseret News 7, no. 11 (May 20, 1857): 85.

[38] “Deep Snows,” Deseret News 9, no. 44 (January 4, 1860): 362.

[39] Richard F. Burton, The City of the Saints and Across the Rocky Mountains to California (New York: Harper and Brothers, Publishers, 1862), 254.

[40] “Smithsonian Institution in Washington—Its History,” Deseret News 5, no. 7 (April 25, 1855): 56.

[41] WWJ, 5:65 (June 28, 1857).

[42] “Deseret Theological Institute,” Deseret News 5, no. 15 (June 20, 1855): 120.

[43] “Deseret Typographical Association,” Deseret News 5, no. 18 (July 11, 1855): 144. On July 2, 1854, this committee made their report to the Deseret Typographical Association along with a motion to start teaching the Deseret Alphabet to Utah citizens. In subsequent meetings, the association continued to promote teaching of the Deseret Alphabet. See also Crawley, Descriptive Bibliography of the Mormon Church, 3:190–92.

[44] “Deseret Typographical Association Festival,” Western Standard 1, no. 8 (April 12, 1856): 2; Crawley, Descriptive Bibliography of the Mormon Church, 3:271.

[45] “Utah,” The Mormon 1, no. 15 (May 26, 1855): 2.

[46] “Deseret Horticultural Society,” Deseret News 5, no. 30 (October 3, 1855): 238.

[47] “Large Water Melon,” Deseret News 9, no. 27 (September 9, 1859): 216.

[48] “Oology,” Deseret News 9, no. 13 (June 1, 1859): 99.

[49] “Northern Lights,” Deseret News 9, no. 27 (September 9, 1859): 213. For Phelps’s reports on flying meteors, see also W. W. Phelps, “Meteoric Phenomenon,” Deseret News 9, no. 37 (November 16, 1859): 296; and Phelps, “Meteors,” Deseret News 12, no. 15 (October 8, 1862): 118.

[50] Phelps, “New Settlement,” Deseret News 7, no. 11 (May 20, 1857): 88.

[51] David Hampshire, Martha Sonntag Bradley, and Allen Roberts, History of Summit County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1998), 76; “From Kamas Prairie,” Deseret News 10, no. 33 (October 17, 1860): 260.

[52] In the name of Joseph Smith, Phelps had put forward some amateurish translations of small individual biblical passages in the Times and Seasons. See chapter 24 herein. The first known occasion when he translated a chapter from the Bible was in a letter to Bishop George Miller on January 3, 1846, containing a translation of Psalm 137. W. W. Phelps to Bishop Miller, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[53] “Seventies’ Hall Lectures,” Deseret News 11, no. 34 (February 19, 1862): 269.

[54] Phelps used this title twice in Deseret Almanac (1861), 23, 26. See also Burton, City of the Saints, 253.

[55] “David’s Psalm 48,” Deseret News 12, no. 42 (April 15, 1863): 330.

[56] “Nebuchadnezzar Still in Pasture,” Deseret Almanac (1861), 23–24.

[57] Phelps noted at the end of his translation, “Joseph Smith, the Prophet, said, that the day of an angel was one year, a week seven years, a month thirty years: a time, three hundred and sixty years. . . . A day with the Lord God in Kolob is one thousand years.”

[58] “Nebuchadnezzar Still in Pasture,” 23; emphasis added.

[59] W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, January 16, 1860, Brigham Young Papers, CHL (translation of John 4); W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, February 18, 1861, Brigham Young Papers, CHL (translation of Zechariah 2); W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, March 18, 1861, Brigham Young Papers, CHL (translation from Song of Solomon); W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, September 29, 1862, Brigham Young Papers, CHL (translation of Jeremiah 31:21–22); “Psalm II,” Deseret News 12, no. 15 (October 8, 1862): 118; “Daniel, Chapter XII,” Deseret Almanac (1861), 26–27; “Ancient Chaldaic,” Deseret Almanac (1861), 28; “Psalm 85,” Deseret Almanac (1861), 30.

[60] T. B. H. Stenhouse, Rocky Mountain Saints (New York: D. Appleton, 1873), 42.

[61] Farthing is the term used in the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:26), while the similar sermon given at the Nephite temple as recorded in the Book of Mormon uses the term senine (3 Nephi 12:26).

[62] “An Old Nephite Coin,” Deseret News 10, no. 41 (December 12, 1860): 321.

[63] JH, October 9, 1860; Fred C. Collier, ed., The Office Journal of President Brigham Young, 1858–1863, Book D (Hanna, UT: By the editor, 2006), 158.

[64] JH, November 8, 1852.

[65] JH, May 5, 1855.

[66] Phelps referred to his endowment work in letters to Brigham Young, including his playing the role of “Lucifer.” He emphasized how little pay he received for this work. See W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, December 15, 1855, October 19, 1864, and February 27, 1865, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[67] E. P. Hingston, ed., Artemus Ward (His Travels) among the Mormons (London: John Camden Hotten, 1865), 61. Richard F. Burton, another British travel chronicler, also noted Phelps’s nickname, “the Devil,” in Burton, City of the Saints, 253.

[68] Fanny Stenhouse, “Tell It All”: The Story of a Life’s Experience in Mormonism (Hartford, CT: A. D. Worthington, 1875), 363–64.

[69] W. W. Phelps to Bishop Miller, October 3, 1864, William Miller File, 1862–1866, CHL; underlining in original.

[70] Deseret Almanac (1861), 20; D&C 87:1–2, 6.

[71] JSP, R2:723. Phelps, of course, knew well this revelation/

[72] Collier, Office Journal of President Brigham Young, 157–58.

[73] Deseret Almanac (1862), 3–7.

[74] Deseret Almanac (1862), 31.

[75] Deseret Almanac (1864), 19–24.

[76] W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, February 18, 1861, Brigham Young Papers, CHL; underlining in original.

[77] W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, February 17, 1863, Brigham Young Papers, CHL; underlining in original.

[78] “Minutes of the Annual Conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints,” Deseret News 13, no. 29 (April 13, 1864): 224. See also WWJ, 6:164 (April 8, 1864).

[79] WWJ, 6:402 (April 5, 1868).

[80] W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, December 4, 1864, Brigham Young Papers, CHL; underlining in original.

[81] W. W. Phelps to Prest. D. H. Wells, October 30, 1858, Brigham Young Papers, CHL; W. W. Phelps to Brother Geo. Q. Cannon, April 11, 1866, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[82] John Whitmer family papers, 1837–1912, MS 6378, CHL.

[83] Frank Esshom, ed., Pioneers and Prominent Men in Utah (Salt Lake City: Utah Pioneers Book Publishing, 1913), 1104.

[84] Henry Phelps advertised his store in the Deseret Almanac, the Deseret News, and city directories. For example, “West side of East Temple street, 14th ward, Exchanges and Trades for cash, foreign and domestic commodities, Wares and Merchandize.” Deseret Almanac (1863), 15.

[85] Mary M. Phelps collection, 1863–1917, MS 7401, CHL.

[86] WWPP, James Phelps to “Father + Mother,” July 7, 1853.

[87] Deseret News 5, no. 5 (April 11, 1855): 36.

[88] “Report of Mission,” Western Standard 2, no. 1 (March 13, 1857): 3.

[89] This note was found in WWPP regarding James Phelps: “Went to New Zealand on mission & never came back (according to Aunt Lydia).” Lydia was Lydia Phelps Thorpe, the Phelpses’ youngest child.

[90] Australasian Mission history: Volume 1, 1840–1899, Part 1, 1840–1859, LR 10870, CHL, 14.

[91] This information is available on www.familysearch.org.

[92] Census and other records, www.familysearch.org. Phelps wrote Brigham Young about the need to support his families, including Sarah, and how difficult it was to provide shingles for Sarah’s house. W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, February 17, 1863, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[93] In that same year, 1856, Phelps wrote Young about possibly caring for a widow (whom he did not name) and her children who had arrived from the East and whose husband had just passed away. W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, March 17, 1856, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[94] “History of the Life of Oliver B. Huntington, Written by Himself, 1878–1900,” 9, online at https://

[95] JSP, D4:436.

[96] Patriarchal Blessings Book, vol. 2, 221, CHL.

[97] W. W. Phelps to Brigham Young, June 29, 1857, Brigham Young Papers, CHL.

[98] George Q. Cannon Journal, February 23, 1863, https://

[99] King’s Jester, “Good Old World,” Deseret Almanac (1862), 31–32.

[100] W. W. Phelps, “The Tombs,” Deseret Almanac (1864), 25.

[101] Stenhouse, Rocky Mountain Saints, 42.

[102] “History of the Life of Oliver B. Huntington,” 9.

[103] “Died,” Deseret News 21, no. 6 (March 13, 1872): 72.

[104] “Obituary,” JH, March 8, 1872.

[105] “Funeral,” Salt Lake Herald 2, no. 235 (March 10, 1872): 3.

[106] “Death of Judge Phelps,” Salt Lake Tribune 2, no. 122 (March 8, 1872): 3.

[107] WWJ, 7:62–63 (March 9, 1872).

[108] “Local and Other Matters,” Deseret News 22, no. 49 (January 7, 1874): 780. Oliver Huntington wrote, “His [Phelps’s] wife was killed instantly, so quickly that she had no time to taste of death. She was killed as she was dipping up a bucket of water from the ditch, a gust of wind hurled a board from a house and it struck her on the neck breaking it instantly. She never tasted of death nor even felt the blow.” “History of the Life of Oliver B. Huntington,” 9.