Anti-Masonic Partisan And Newspaper Editor

Bruce A. Van Orden, "Anti-Masonic Partisan And Newspaper Editor," in We'll Sing and We'll Shout: The Life and Times of W. W. Phelps (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 21–30.

Anti-Masonry appears to the modern mind as a movement highly unusual and bereft of any reasonable basis for existence. But in its day, most especially in New York State, this highly religious Anti-Masonic movement and the political party that it spawned greatly influenced politics for at least a decade and left a residue lasting to the present. W. W. Phelps was an ardent Anti-Mason, and he was surrounded by many others. Thousands of people added their votes and voices to the movement, including many leading clerics and politicians. They were not only in New York but also in twelve other states. Book of Mormon witness Martin Harris was also an Anti-Mason. Eber D. Howe of Painesville, Ohio, the first person to compile and publish an anti-Mormon book, was, like Phelps, an Anti-Masonic editor, in his case of the Painesville Telegraph.

Understanding Freemasonry

Anti-Masonry cannot be understood without first investigating Freemasonry, or as it was often simply called, Masonry. Masonry was and is an oath-bound order of men with a secret ritual based on the medieval guilds of stonemasons and cathedral builders. The order has promoted ethical teachings such as industry, harmony, and obedience to civil authority manifested in its members’ conduct in their daily responsibilities and in their relationships to each other. Masons have defined their craft in this way: “Freemasonry is a beautiful system of morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols.” Furthermore, “Freemasonry is a way of life; as an organization, its purpose is to make good men better.”[1]

Beginning in 1717 with the formation of the first Masonic Grand Lodge in London, England, Freemasons attempted to trace the fraternity’s origins to antiquity, even from Adam or Moses through King Solomon. Existing evidence, however, shows that modern Masonry arose out of the lodges of English and Scottish stonemason guilds consisting of men who worked on the cathedrals, castles, and monasteries of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The fraternity appeared in American British colonies within a few years after the organization of the first English lodge and under the “warrants” (or authorization) of this London Grand Lodge. Before the Revolution, American Masonry was accessible only in seaport towns. But it spread rapidly among the Continental officers during the war. George Washington became a member, encouraging other men to join. Masonry developed into a widespread popular movement during the 1790s as one of many religious responses to the frenzied evangelization known as the First Great Awakening.[2]

At the beginning of the Revolution, about 2,000 Masons were in the thirteen American colonies. In 1800 Freemasonry claimed 11 Grand Lodges, 347 subordinate lodges, and 16,000 members in the United States. By 1826, the year of the Morgan Affair, the infamous event that stopped the growth of Masonry, there were 26 Grand Lodges, 3,000 constituent lodges, and between 100,000 and 150,000 members. In New York State alone, which had the largest Masonic membership, there were about 500 lodges and 20,000 members.[3]

Masons were generally more prosperous and politically active in northeastern states than men who did not belong to the fraternity. The bulk of the members were businessmen, traders, and village and town leaders. It was commonly believed that the Masons “were an aristocratic lot who threatened to control all society by their power to reward one another. The suspicion had some basis in fact.”[4] Almost as a matter of course, up-and-coming men of potential influence would join the local lodge. Phelps, a community leader in Cortland in the 1820s, became a Mason. Fraternity members were particularly strong among the followers of New York governor DeWitt Clinton and in the political clique led by Martin Van Buren known as the “Albany Regency.”[5]

Development of Anti-Masonry

Freemasonry was not universally popular among New Yorkers, however. A suspicious sentiment against Masons developed in the “burned-over district” (the common term referring to western New York where fanatic evangelization took place from 1805 to 1835) among the evangelical wings of the Baptists, Presbyterians, and Methodists. Western New York became the seedbed for the Anti-Masonic movement. Some transplanted New Englanders brought with them a deep-seated distrust of Masonry when they migrated.[6]

Institutionalized Anti-Masonry began after the 1826 Morgan Affair. William Morgan, a feisty fifty-two-year-old stonemason and recent immigrant to Batavia in western New York, quarreled repeatedly with other Masons. He decided to get even with his adversaries by publishing a book, Illustrations of Freemasonry, that revealed the secrets of the first three degrees. This betrayal outraged other Masons, and they appealed to Morgan to cease his “madness,” but he persisted. David C. Miller, editor of the Batavia Republican Advocate, agreed to publish and sell Morgan’s book. Some lodge members seized the page proofs and set fire to Miller’s printing establishment. On September 10 the head of the Masonic Lodge in Canandaigua brought charges of theft against Morgan, which led to his arrest. On the twelfth, Morgan was abducted from the Canandaigua jail by members of the fraternity and was never seen again. According to most sources, he was taken west and drowned in the Niagara River. His exact fate has always remained a mystery.[7]

News of Morgan’s abduction and alleged murder spread rapidly throughout western New York, stirring up angry sentiment against Masonry and individual Masons. Hundreds of Masons repudiated their membership, throwing the lodges into turmoil. By the fall of 1827, a new movement was in full swing with the name Anti-Masons. The movement gradually evolved from a mere moral crusade to a political faction through a series of town meetings and conventions. By year’s end, Anti-Masons were publishing newspapers and pamphlets. Also by the end of 1827, many Masonic lodges in western New York were forced to shut down. The Anti-Masonic movement moved eastward through the center of the state, on to New England, and down to New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Ohio.

Anti-Masonry, particularly as a political party, came at a transitional moment in New York State politics. Factional splits had been intensifying for some time, and conditions were now ripe for creation of a new party that would submerge the differences and unite voters behind a platform pledged to defend democracy and equality before the law.

Phelps and Anti-Masonry

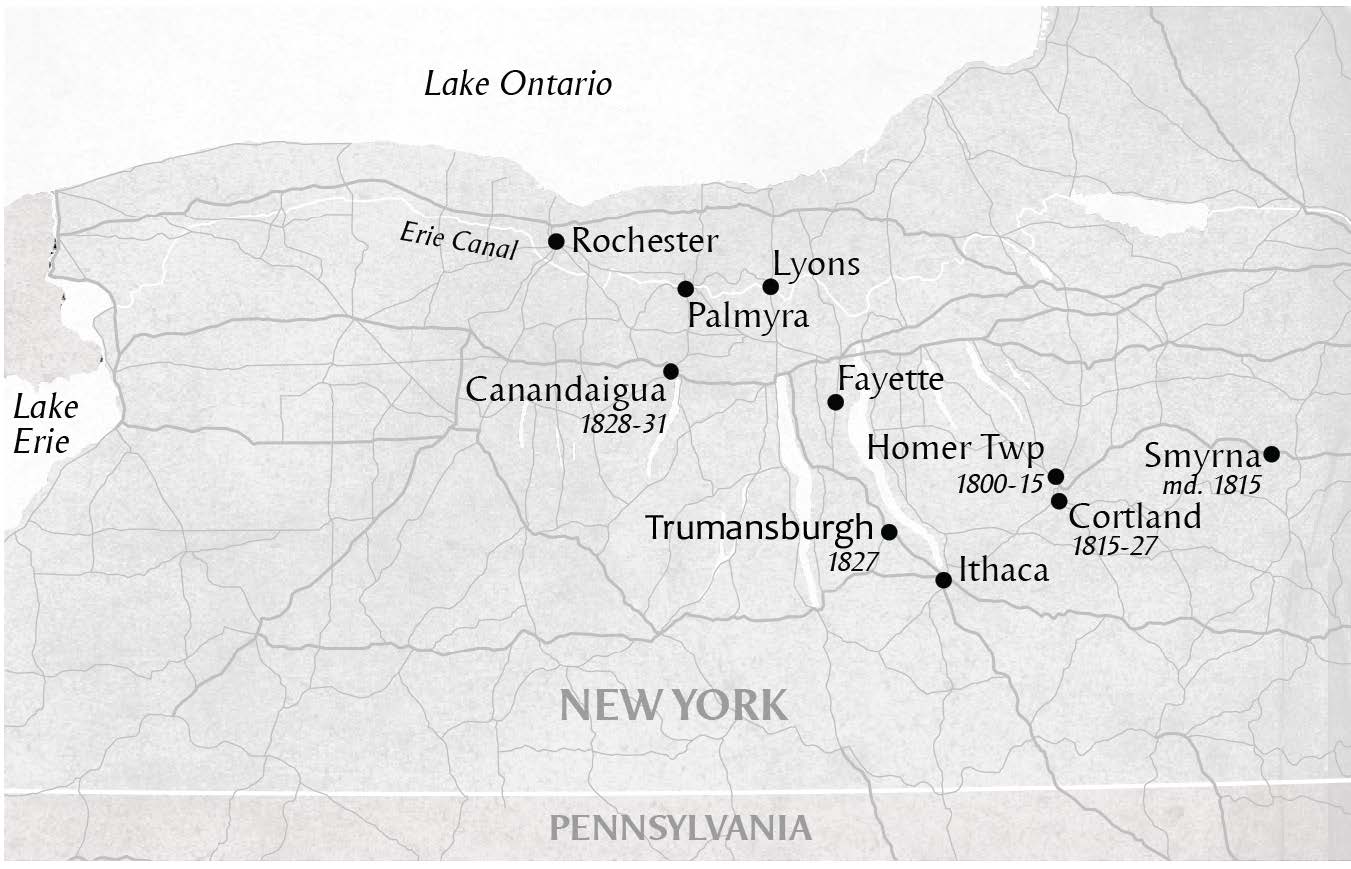

Locations in central New York showing periods of Phelps’s residence. Map by Brandon S. Plewe. Mormon Historical Studies 16, no. 1 (Spring 2015): 4.

Locations in central New York showing periods of Phelps’s residence. Map by Brandon S. Plewe. Mormon Historical Studies 16, no. 1 (Spring 2015): 4.

How did Phelps become involved in this Anti-Masonic ferment? He was a Master Mason in Cortland. He noted in his first Anti-Masonic newspaper, the Lake Light in Trumansburgh, that he abhorred Morgan’s abduction and murder and the secretive Masonic cover-up. He assaulted what he considered the conspiratorial and aristocratic style of Masonry. Phelps was a religious firebrand by nature and was motivated as were nearly all early Anti-Masons by strict religious beliefs common to that era. He possessed a deep love of liberty and a belief that all American men should be treated equally under the law. Phelps had strong egalitarian instincts, a hallmark of Anti-Masonry.

Following the Morgan affair, Phelps went through considerable soul-searching and then decided to leave Masonry. He had lost his livelihood in Cortland and had a number of political foes there. He noted that there was lingering pro-Masonic sentiment in Cortland Village. Phelps saw great opportunity to regain his reputation and ability to earn a living by leaving Cortland and casting his lot with Anti-Masonry. He took a job in late September or early October 1827 as the editor of a new newspaper, the Lake Light, in Trumansburgh, Tompkins County, New York. A Mr. R. M. Bloomer, a local Tompkins County businessman, hired Phelps as editor.[8] This was the first newspaper in this village.[9]

Trumansburgh was a small village two miles west of one of the longest “finger lakes,” Cayuga Lake. To get to Trumansburgh from Cortland, one had to travel twenty miles southeast to the Tompkins County seat in Ithaca at the foot of the lake and then twenty more miles northwest up the lake. Trumansburgh was a hotbed of Anti-Masonic sentiment, and many churchmen and politicians joined hands in the community to crush Masonry. “House was divided against house, neighbor against neighbor, churches closed their doors to Masonry and its advocates, and when found within its pale summary ejection followed.”[10] Anti-Masons in the village desired to promote their philosophy and conquer Masonry, so they followed American custom and created a newspaper. They needed an experienced printer and editor and found their man in Phelps, then thirty-five years old. A later local history favorable to Masons labeled Phelps a “crank” and said “there was nothing so dirty and contemptible but that he entered into.” It added sarcastically, “This bright and shining light afterward became a Mormon.”[11] While profoundly partisan, Phelps in reality attempted to be careful with his remarks in the biweekly, four-page Lake Light. His Anti-Masonic successors turned out to be the mean-spirited ones, certainly in comparison to Phelps. These other Trumansburgh Anti-Masons attacked individual Masons in vile terminology.

As an Anti-Masonic writer, Phelps displayed attitudes and traits that persisted after he joined the Latter-day Saints. His writing was not only far too wordy and pedantic but also often awkward and incoherent. He was passionate and wrote with certitude about what he believed.

Phelps was grateful to be an American. Said he, “[We are] placed in a land of liberty, of peace, of industry, of improvement, of means, of plenty, of sciences, of song, and of religion.” He added that “ours is the happiest country in the world” and that “there is no spot more favored.” What angered him was that Freemasons with their secret activities and aristocracy threatened America’s greatness. He even accused Masons of desiring monarchy. “We go for the whole, not for privileged orders or an enlightened few,” he wrote. “We are all equal in a free country.” He also had faith in the Constitution’s First Amendment rights of a free press: “Regarding the benefit of the press, suffice it to say that there is no sole effectual means under heaven to convey news around the world, no so faithful watches in the country to sound the trumpet of danger as welcome as the newspapers.” William attributed American liberty to Almighty God. He wrote, “May it [our freedom] long long [sic] be so even until Jehovah shall have wasted the elements in a world of flame.”[12]

Phelps undoubtedly needed this employment as a printer and editor in Trumansburgh to support his family. A notice ran in the Cortland Observer that he, being an “insolvent debtor,” would have his estate put up for division to his creditors in the upcoming December.[13] Phelps admitted in the first number of the Lake Light that his “necessities” had urged him to “come” to Trumansburgh. Phelps was not the owner of the paper, and he knew that he did not have independent funds of his own. He realized that if the paper did not do well, he would be out of this job. He urged local citizens to subscribe for “$2.00 per annum” (a common price for newspapers in that era) and to advertise in his paper. He indicated that legal notices would be published according to stipulations in New York law. Historian Daniel Boorstin has explained, “The thriving business of printing legal notices was itself a by-product of rapid settlement and expansion. Not only did it make newspapers profitable, in many places (in western New York, for example) the fees for legal notices alone made a country newspaper possible.”[14]

In each number, Phelps pounded on the subject of the “horrid” Morgan Affair, publishing lengthy accounts of the entire event, including the “heart-rending scene” at Morgan’s funeral, and sounded the alarm that the guilty Masons were going unpunished for their vile deed. “Nothing in the annals of history since our Savior’s crucifixion among the acts of men is comparable with this shocking tragedy,” he hyperbolized.[15] He emphasized, however, that his group desired no contention with “individuals, but with the institution.” Phelps’s paper also announced the formation of other Anti-Masonic newspapers throughout the state and publication of Anti-Masonic pamphlets.

Naturally, Phelps missed his wife and children very much, having left them behind in Cortland. In “The Pleasures of Home,” he mused, “Home is the flowery pathway of life, where the nobler passions of humanity blossom, in unspotted purity; the sacred shrine at which all our longing, vagrant, pilgrim fancies love to worship.” Whenever he was absent from his wife and children in his life, Phelps yearned to be reunited with them. Although encountering scorn from others, he knew he could always return to his home for comfort. “Man can only enjoy supreme happiness in this bright sphere of domestic affection. . . . Satiated with the world’s tinsel, and derisive amusements we return home, with redoubled satisfaction, and prize and love it the more.”[16]

Phelps also published poetry in the Lake Light and occasionally included verses that he wrote himself. His propensity for composing original poetry increased when he became a Latter-day Saint.

In January 1828, Phelps ran a lengthy notice in the Lake Light that he intended to begin a new weekly newspaper in Canandaigua, Ontario County, to be called the Ontario Phoenix, published by W. W. Phelps & Co. He ran this notice in several successive issues. “Necessarily its principles will be strictly anti-masonic,” he emphasized. “Its aim [will be] to expose the evil consequences of secret societies in a free government, and its course independent,—manly, and free from the cousining of monied aristocracies, or dictation of individuals for personal glory.” He added that “religion through the merits of a Savior shall receive our aid.” Finally, he noted that the paper would embrace “correct notions of liberty, anti-intemperance, poetry, amusement, the doings of the state & national governments, foreign news, passing events, and literary advances.”[17]

In February 1828, Phelps, as a delegate from Tompkins County, attended the first statewide Anti-Masonic convention in Le Roy, Genesee County, New York, located about halfway between Canandaigua and Lake Erie. Twelve western New York counties were represented. Le Roy had become the stronghold of the “blessed spirit,” as the religious enthusiasts for Anti-Masonry were calling the movement. The leader of this convention was David Bernard, who for thirty years had served as a Baptist minister in fifteen different rural churches. Many Baptists in western New York were greatly angered by Masonic clergy and laymen who excluded non-Masons from their fellowship, this in total violation of the Baptist closed communion principle. Bernard had been an early reader of Morgan’s Illustrations and was among the first to desert Masonry in 1826. Le Roy convention delegates agreed to support Bernard’s planned exposé of fifty separate degrees of Masonry. His book Light on Masonry came out in 1829. Phelps’s name was listed as a delegate from Tompkins County. Phelps joined a committee to compose a memorial to Congress explaining the Morgan abduction and murder.[18]

Phelps attended a second convention in Le Roy on March 6, 1828, again as the Tompkins delegate. This convention called for the suppression of Masonry through the ballot box, for a statewide political convention in August in Utica to nominate candidates, and for the establishment of many free presses and other means to spread the “blessed spirit.”[19]

Ontario Phoenix in Canandaigua

Phelps reported the proceedings of these two Le Roy conventions in the Lake Light. He proceeded to complete his affairs in Trumansburgh, including handing over the publication of the Lake Light in late March to others. Phelps then went to Canandaigua to publish an even larger newspaper with backing of many businessmen in the Canandaigua area. On March 28, 1828, his prospectus for the Ontario Phoenix appeared in the Albany National Observer. The first issue of the Ontario Phoenix came out on April 30 that year. Phelps was delayed by bad roads in getting from Trumansburgh to Canandaigua and apologized for being three weeks late in getting out his first issue. Part of the problem may also have been in transporting his family from Cortland to Canandaigua.

This new venture catapulted Phelps to prominence in western New York. He used the Phoenix to expound the social, religious, and political views of Anti-Masonry, a popular movement in one of the chief cities of this region of country—Canandaigua.

The third Anti-Masonic convention, held again at Le Roy on July 4–5, 1828, marked the zenith of the evangelical, religious impulse of the movement. The convention issued a “Declaration of Independence from the Masonic Institution” and asserted that Freemasonry was “opposed to the genius and design of this government, the spirit and precepts of our holy religion, and the welfare of society generally.” The document was signed by 103 seceding Masons and indicated the number and type of Masonic degrees each had taken. Phelps was the third person listed, behind Solomon Southwick, editor of the Albany National Observer, the premier state journal of Anti-Masonry, and Rev. David Bernard—the two acknowledged religious leaders of Anti-Masonry. Phelps’s residence was now listed as Canandaigua, and his number of degrees in Masonry was listed as three. Other signers had various degrees of experience as Masons, some more and some less than Phelps. The declaration noted that these men were prominent for their “talents and respectability, for real worth and standing in [their] community.” Convention minutes noted that the delegates included three judges of county courts, seven ministers, three attorneys, two physicians, and four newspaper editors (Phelps being one). The convention resolved not to do any campaigning for or against candidates for public office.[20]

Anti-Masonry with its definitive equal rights philosophy would certainly lead its proponents to be in favor of some New York political candidates and against others. A rift had developed in the Anti-Masonic movement about its purpose. Wily politicians such as William Henry Seward, Francis Granger, and Thurlow Weed (known as the Seward-Granger-Weed Triumvirate) would assume complete control of the crusade. At the same time, idealists wished to use it as a means of remaking society by protecting equal rights and opportunities. These same people favored limited political action, hoping to see the Anti-Masonic organization disband after it had obliterated Masonry. In contrast were the pragmatic politicians like Seward, Granger, and Weed who had sympathy for the Anti-Masonic causes. Their pragmatic desire was to establish a permanent political party to elect candidates opposed to the “Albany Regency” Democrats led by Martin Van Buren and to distribute the spoils of office.[21]

Thurlow Weed, a Rochester newspaper editor and businessman, schemed to use the rising Anti-Masonic sentiment in New York to fulfill his political designs. The Anti-Masons had not nominated candidates in their July Le Roy convention, so Weed directed a political convention of his own in late July in Utica. His platform was anti-Regency and supported then-sitting president John Quincy Adams. Weed arranged for Francis Granger, a state assemblyman from Canandaigua with Anti-Masonic ties, to receive the lieutenant governor nomination in an effort to pull the Anti-Masonic zeal to his side.

The Anti-Masons went forward with their own convention in Utica on August 4, 1828. The Utica delegates nominated Granger for governor hoping he would accept their offer for first place on the ticket rather than the second place Weed had offered him. Granger took three weeks to make up his mind and then opted to go with Weed’s (John Quincy) Adams party, which had nominated Judge Smith Thompson (not a Mason) for governor. Shocked Anti-Masons then called another convention in Le Roy on September 7 and nominated Solomon Southwick for governor instead.[22]

Phelps aspired to the Anti-Masonic nomination for lieutenant governor. After all, he was one of the leaders of the first three Le Roy conventions and was editor of the largest Anti-Masonic newspaper in the Finger Lakes region. Unlike Baptist minister David Bernard, Phelps was also politically astute; at least he fancied himself such. But both the August and September Anti-Masonic conventions opted instead to nominate John Crary, a state senator from Washington County, for the position.

In the November 1828 election, the Anti-Masonic split helped Van Buren garner the governorship with less than a majority vote. Nevertheless, Anti-Masons captured a number of state senate and assembly seats. Phelps took credit for this political success even though he was only one of several major players in the movement. The new party emerged as a potent force in the state legislature for the next five years. Seward, Granger, and Weed quickly moved in the next four months to take total control of the Anti-Masonic Party.[23]

Phelps continued his Anti-Masonic zeal in the pages of the Ontario Phoenix through May 1831, when he quit the paper to join the Mormons in Ohio. Phelps was an active participant in expanding one of the most deep-rooted American institutions, the press. He took shots regularly against numerous governmental officers and institutions, including President Andrew Jackson.[24] Pro-Masonic newspaper editors in turn pummeled Phelps and rightly accused him of hyperbole and name-calling.[25]

Phelps’s paper came out each Wednesday with a masthead drawing of a phoenix bird rising out of a fire with freedom printed on its wings. Legal notices and business advertisements took up two of the four pages in each issue. He advertised that he could print items for customers. These sources provided his income. During his Canandaigua years, 1828–1831, Phelps and his printing company were significant contributors to the city’s social, religious, and political scene. A side street entering into Main Street in present-day Canandaigua is designated as “Phoenix Street.” Likely on this very street, Phelps set up his W. W. Phelps & Co. printshop and bookstore.

William and Sally’s family grew in Canandaigua. On October 31, 1828, their second son, Henry Enon, was added to the family. A daughter, Mary, was born October 19, 1830. They occasionally worshipped in different congregations. One of the most prominent was the Congregational Church, the denomination that Sally had belonged to in her youth. The Congregational meetinghouse was constructed in 1815, years before the Phelpses came to Canandaigua, and still stands on the city’s Main Street.

While in Canandaigua, Phelps started hearing rumblings about a young village seer a few miles to the north and his “gold Bible.” Ever so gradually, the spiritual tug from a new book of scripture, the Book of Mormon, pulled Phelps and his family away from their Anti-Masonic moorings. William soon was lampooned with the derogatory nickname “Phifer Phelps” in various newspaper circles. Phelps had been accused in Cortland of being nothing more than a “fifer” in the army. When Phelps dabbled with interest in the Book of Mormon and Mormonism, his opponents used the ph from his surname and from the Phoenix to come up with “Phifer Phelps.”[26] Before long Phelps would abandon Anti-Masonry.

Notes

[1] Allen E. Roberts, The Craft and Its Symbols: Opening the Door to Masonic Symbolism (Richmond, VA: Macoy Publishing and Masonic Supply Company, 1974), 8. For further symbolic meaning of Masonry, I have used Roberts, Craft and Its Symbols, 67–71; Harold Waldwin Percival, Masonry and Its Symbols, 3rd ed. (New York: Word Foundation, 1974), 1–6; Arthur Edward Waite, A New Encyclopedia of Freemasonry (New York: Weathervane Books, 1970), 1:279–86; William Preston Vaughn, The Antimasonic Party in the United States, 1826–1843 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1983), 10–11; Michael Homer, Joseph’s Temples: The Dynamic Relationship between Freemasonry and Mormonism (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2014).

[2] Robert Freke Gould, The Concise History of Freemasonry, rev. ed. (New York: McCoy Publishing and Masonic Supply, 1924), 449–50; Vaughn, Antimasonic Party, 10–11; Michael W. Homer, “‘Similarity of Priesthood in Masonry’: The Relationship between Freemasonry and Mormonism,” Dialogue 27 (Fall 1994): 4–13; John L. Brooke, The Refiner’s Fire: The Making of Mormon Cosmology, 1644–1844 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 94–98.

[3] Brooke, Refiner’s Fire, 94–98.

[4] Edward Pessen, Jacksonian America: Society, Personality, and Politics, rev. ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1985), 262.

[5] Vaughn, Antimasonic Party, 11–12, 23–24.

[6] Vaughn, Antimasonic Party, 13.

[7] Vaughn, Antimasonic Party, 2–5; Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Freedom, 1822–1832 (New York: Harper & Row, 1981), 139; P. C. Huntington, The True History Regarding Alleged Connection of the Order of Ancient, Free and Accepted Masons with the Abduction and Murder of William Morgan in Western New York, in 1826 (New York: M. W. Hazen, 1886), 15–96.

[8] The first issue of the Lake Light was dated Wednesday, October 10, 1827. Phelps wrote that he was hurried in getting out the first number and apologized for its untidy appearance. Evidence shows that he arrived in Trumansburgh in late September without his family, who continued to reside in Cortland. The complete run of the Lake Light on microfilm is found in the Olin Library of Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.

[9] John H. Selkreg, ed. Landmarks of Tompkins County, N.Y. (Syracuse: D. Mason, 1894), 45.

[10] A History of Trumansburgh (Trumansburgh, NY: Office of the Free Press, 1890), 43–44.

[11] History of Trumansburgh, 44. For another anti-Phelps reference, see Proceedings of the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of the State of New York (New York: J. J. Little & Ives, 1908), 154–55.

[12] Lake Light 1 (Trumansburgh, NY), October 10, 1827, 2.

[13] Cortland Observer 3, no. 3, October 12, 1827.

[14] Daniel J. Boorstin, The Americans: The National Experience (New York: Vintage Books, 1965), 129.

[15] “The Morgan Affair,” Lake Light 1, October 29, 1827, 2.

[16] “The Pleasures of Home,” Lake Light 1, December 24, 1827, 2.

[17] “Notice,” Lake Light 1, January 21, 1828, 3. This ran numerous times in successive issues.

[18] Vaughn, Antimasonic Party, 19–20, 28; David Bernard, Light on Masonry (Utica, NY: William Williams Printer, 1829); Western Star (Westfield, NY), February 16, 1828, 1; Lake Light, March 5, 1828, 2; Geneva Gazette, March 19, 1828, 3.

[19] Bernard, Light on Masonry, 452–59.

[20] Vaughn, Antimasonic Party, 29–36; Bernard, Light on Masonry, 452–59.

[21] Vaughn, Antimasonic Party, 27–28.

[22] Vaughn, Antimasonic Party, 29–30.

[23] Vaughn, Antimasonic Party, 31–38.

[24] The Ontario County Historical Society has a microfilm copy of the Ontario Phoenix from July 7, 1830, to August 29, 1832. No known copies of the run from April 1828 to July 1830 are available.

[25] See Masonick Record 2, no. 25 (Albany, NY), July 19, 1828.

[26] Geneva Gazette, October 20, 1830, and November 1, 1830; Wayne Sentinel, October 11, 1831; Rochester Republican, August 21, 1832, September 11, 1832, and July 3, 1833.