Sorting Out the Seven Marys in the New Testament

Blair G. Van Dyke and Ray L. Huntington

Blair G. Van Dyke and Ray L. Huntington, “Sorting Out the Seven Marys in the New Testament,” Religious Educator 5, no. 2 (2004): 53–84.

Blair G. Van Dyke was a principal in the Church Educational System and an instructor of ancient scripture at BYU, and Ray L. Huntington was associate professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University when this was published.

It is apparent from the text of the New Testament that the name Mary (the Greek form of the Hebrew Miriam) was a common name in first-century Palestine. Consider these Marys: Mary the mother of Jesus, Mary Magdalene, Mary of Bethany, Mary the mother of James and Joses, Mary of Cleophas, Mary the mother of John Mark, and Mary of Rome. The task of keeping these seven important women of the New Testament straight frequently results in confusion or misidentification. [1] Therefore, it is not surprising that from early-morning seminary classes to New Testament classes at Brigham Young University, religious educators consistently field inquiries about these seven women mentioned in the writings of Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, and Paul. Thus, we will clearly identify these women in order to resolve confusion and misidentification where possible. Moreover, in delineating the differences between the seven Marys, we also see the characteristics of deep discipleship common to each woman, which we will accomplish in three stages.

First, to provide context, we will briefly explore the role of women in first-century Palestine. A general awareness of the socio-cultural nuances of this time period is imperative to understanding the significant role these seven women played in the early Church. Second, we will survey how the four Evangelists and Paul (in the case of Mary of Rome) portrayed these women as disciples of Christ in their respective settings and circumstances. This survey will be grounded in scriptural texts and the careful use of extracanonical sources. Last, we will provide two charts intended to serve as quick reference tools for determining the location and frequency of references to the women named Mary. Because the Gospel writers provided more narrative regarding the activities of Mary the mother of Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Mary of Bethany, the sections devoted to them will be lengthier and include greater detail. The biblical texts addressing Mary of James and Joses, Mary of Cleophas, Mary of John Mark, and Mary of Rome range from modest to scant. Thus, the brevity of their treatment in the New Testament is reflected in the length of discussion we devote to these four women. Nevertheless, we will discover clues in the available narrative that unlock, in part, the noble stature of these women.

Women in First-Century Palestine

As one scholar noted: “If writing women’s lives is never simple, to write about Jewish women’s lives during the years and in the regions where Christianity first emerged is fraught with distinctive perils.”[2] One of those distinctive perils may be the tendency to overgeneralize and oversimplify the subject matter. However, having taken into account the multiple and varied nuances associated with gender issues of the time, we draw the following conclusion: as a general rule, women in first-century Palestine faced a difficult life. Specifics will be offered in the following overview, which is by no means comprehensive, in an effort to provide context to our primary focus on New Testament women named Mary.

In Jesus’s day, all women in the Greco-Roman world lived within a strict patriarchal framework. However, there was a good deal of variety in the opportunities afforded women from one culture to another. For example, a Roman woman could not rule, but she could be a force of power behind the man on the throne. An Egyptian woman could actually rule. Women in Asia Minor, Macedonia, and Egypt could engage in private business. Though women in Roman society did not enjoy as many freedoms as their peers in Egypt or Macedonia, they enjoyed higher levels of education because educating women in Roman circles was deemed important.[3]

By comparison, Jewish women of first-century Palestine were more limited. Like the greater Greco-Roman world, Jewish culture of Jesus’s day was staunchly patriarchal and, generally speaking, a woman was to remain unobserved in public life. Prior to her marriage, she answered entirely to her father, and it was preferred that she not leave the home at all. Furthermore, if the situation warranted it, her father could sell her into slavery before she came of age to marry.

The betrothal ceremony marked the beginning of the transfer of power over the woman from father to husband. Legally, betrothal involved two steps and constituted a relationship akin to marriage that could only be broken by a formal divorce. During this period the couple was considered husband and wife, albeit they did not share the same home or bed. The first step involved a marriage contract before witnesses, and the second step involved the husband taking his wife from her father’s home to live in his family home. This two-step process generally lasted approximately one year and was usually completed by the time the woman was twelve or thirteen. The woman’s move into the home of her husband constituted his complete authority over her, but she gained few freedoms in the exchange. [4] Her status in society was just above that of a Gentile or a slave, and she was obligated to obey her husband as strictly as a slave obeyed his or her master. [5] She could own property through inheritance, but given the early age of betrothal, it was rare for a woman to enter marriage holding property independent of her husband. [6] Furthermore, while education was granted to young boys from privileged families, their female peers usually received no formal schooling. Subsequently, the vast majority of Jewish women of the period were illiterate, having received only basic religious training. Finally, she could not hold public office, and her public testimony was strictly limited if it contradicted the word of her husband. Josephus records that in certain cases, her witness could not be trusted or admitted in legal proceedings “on account of the levity and boldness of [her] sex.” [7] Generally speaking, however, her word was considered more trustworthy than that of a Gentile or a slave. [8]

It is not surprising, then, that a Jewish woman in Palestine, like women in other parts of the Greco-Roman world, was discouraged from moving freely in society. [9] She could venture out into public to fulfill some of her domestic duties, but only if heavily veiled. Interaction of any kind with men was forbidden. In some cases, even a greeting between a man and a woman could lead to divorce. [10]

Of course, there existed a spectrum of application for these cultural expectations among Jewish women in Palestine. For practical reasons, peasants in small villages could not fully subscribe to many of these requirements because there were animals to feed, fields to tend, and water to fetch for drinking, cooking, and cleaning. Obviously, these activities required movement outside the home. In this regard, strict adherence to these cultural expectations was often viewed as a mark of status, as only the wealthy could afford to have their women maintain true seclusion. [11] Even so, a woman’s world in Palestine typically revolved around housework, husband, and children. [12]

The domestic duty of rearing children rested solely on her shoulders, and the birth of a daughter was viewed as a mixed blessing. As on was nursed by his mother twice as long as a daughter, who was always placed behind sons, even in the essentials of life such as basic nutrition. [13] From birth, then, Jewish women in Palestine were largely absent from male-dominated public life in many ways. [14] This exclusion was rarely negated except in the pitiable case of widowhood, wherein a woman was allowed to assume male roles in order to ensure survival for herself and her children. [15] Because a woman’s legal status was tied to her husband, his death left her detached from the few rights and protections afforded her by the law.

In the realm of religious practice, scriptural directives regarding women provided a limited reprieve. The Torah mandates that honor be shown to a mother (see Exodus 20). Also, the spiritual significance of the mother was manifest in the fact that Jewish lineage for her children was determined by her bloodline. Finally, a Jewish woman in Palestine was afforded the opportunity to enter into Nazarite vows (see Numbers 6), participate in feasts and associated sacrificial meals (see Exodus 12), offer sacrifice (see Luke 2:22–24), and serve in the temple (see Luke 2:36–38). Beyond these, however, a woman’s worship experiences were generally limited to those activities that could be carried out within the privacy of the home and that served to preserve and pass on religious traditions and practices to her children.

While this depiction of the treatment of women may be troubling to readers today, it represents the general conditions that women faced in day-to-day living two millennia ago. Without question, exceptions to these general rules existed, and no doubt many Jewish women of Palestine lived full and happy lives within their own socioeconomic, spiritual, and cultural niche. However, as a general rule, Jewish women in Palestine enjoyed limited civic rights, were restricted in religious involvement, and were valued almost exclusively for their procreative abilities and domestic services.

This, then, is part of the stage onto which Jesus stepped. We can only imagine the uplifting and immediate effects His ministry and teachings had upon women who heard and embraced His message. Many of these effects are evident in the lives of the women named Mary in the New Testament.

Jesus and the Status of Women

Understanding the sociocultural and religious norms and their impact upon Jewish men and women in Palestine in the first century 56 allows one to draw a conclusion regarding the ministry of Jesus. The four Gospels, Acts, and the writings of Paul not only bear witness of Jesus’s divine mission but also document Jesus’s desire to raise the status of women, even if it meant challenging the current social practices of the day. [16] Indeed, Elder James E. Talmage taught that “the world’s greatest champion of woman and womanhood is Jesus the Christ.” [17] Some examples of the Savior’s breaks with social norms of the day include conversing with the woman at the well in Samaria and bearing witness of His divinity (see John 4:5–29), inviting women to travel with Him and be His disciples (see Luke 8:1–3), publicly expressing compassion to the widow of Nain both in conversation and in the act of raising her son from the dead (see Luke 7:11–15), allowing women who were ritually unclean to touch His person (see Luke 8:43–48),and, on at least two occasions, allowing women to unveil their heads in public to use their hair to wash or anoint His feet (see Luke 7:36–39; John 12:1–3). Christ also taught with parables whose central figures were women (see Matthew 25:1–13; Luke 18:1–8; Luke 15:8–9), and He allowed a woman to temporarily abandon certain domestic duties in order to be instructed at His feet (see Luke 10:38–42).

These and many more examples in the Gospels constitute radical departures from the accepted norms of the day. Taken together, we see the Savior’s earnest desire to institute reform and generate spiritual equity within the bonds of discipleship. [18] In His day, such a reformation was repugnant to most. As a disciple of Jesus, a woman frequently enjoyed greater privileges than her peers in Palestine and the Greco-Roman world. The following surveys of the women named Mary should be considered in this context.

Mary, Mother of Jesus

The authors of the four Gospel accounts in the New Testament provide the most significant treatment of Mary, the mother of Jesus, in the rise of Christianity. Furthermore, from a Latter-day Saint perspective, no woman is esteemed more highly than Mary. Our esteem for her does not rise to the level of worship—to be sure, she is not considered a mediator between mankind and God—nevertheless, she is viewed as a chosen vessel of the Lord. This high regard is captured in latter-day scripture. In fact, the Book of Mormon contains four prophecies that address the significance of Mary. [19] First, we learn from Nephi that Mary was an exceedingly fair virgin who carried the Son of God in her arms and nurtured him to adulthood (see 1 Nephi 11). Second, King Benjamin taught the people of Zarahemla that the mother of the Son of God “shall be called Mary” (Mosiah 3:8). Third, Alma’s prophecy about Mary describes her as a virtuous woman who is “a precious and chosen vessel” (Alma 7:10). Finally, the Lamanite leader King Lamoni came to know through a vision that the Messiah would “be born of a woman, and he shall redeem all mankind who believe on his name” (Alma 19:13). Taken together, these prophecies indicate the importance of Mary, the mother of Jesus, in the canon of scripture that has emerged in our day. The fact that King Benjamin identified Mary by name approximately 124 years before her birth places her in a small circle of individuals whose names were known before their mortal life began, such as Noah, Aaron, Moses, John the Baptist, Jesus Christ, and Joseph Smith. [20]

Latter-day prophets and apostles have also described the greatness of Mary, the mother of Jesus. One example is found in the writings of Elder Bruce R. McConkie: “Can we speak too highly of her whom the Lord has blessed above all women? There was only one Christ, and there is only one Mary. Each was noble and great in pre-existence, and each was foreordained to the ministry he or she performed.” [21]

Of course, the importance of Mary is an evident feature of the four Gospel accounts. In fact, three of the four Evangelists (Mark excluded) focus on the mother of Jesus as their testimonies unfold. The first two chapters of Matthew, whose Gospel account is directed primarily to a Jewish audience, center heavily upon Jesus under the watchful care of Mary and Joseph. In chapter 1, he provides a genealogy of Joseph’s line, intending to prove that Jesus was of royal descent from the tribe of Judah and was truly the “Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham” (Matthew 1:1). Luke provides a genealogy that some believe is the royal lineage of Mary, who also descended from King David (see Luke 3:23–38). Talmage explains that “a personal genealogy of Joseph was essentially that of Mary also, for they were cousins. Joseph is named as son of Jacob by Matthew, and as son of Heli by Luke; but Jacob and Heli were brothers, and it appears that one of the two was the father of Joseph and the other the father of Mary.” [22] It is important to note, however, that while Joseph is of Davidic descent, he is not the father of the Savior; Jesus’s descent from the Davidic line rests solely in Mary’s royal lineage. [23]

Matthew describes Mary’s espousal to Joseph. She is contractually bound to him but does not yet live in his home. Under these circumstances, Mary is “found with child” following her stay in Judea, [24] and Joseph is “minded to put her away privily” (Matthew 1:19). An angelic ministrant appears to Joseph in a dream to intervene on Mary’s behalf. 58 The angel tells him to fear not to take Mary to wife, explaining that the child in her womb is the Savior of mankind and should be named Jesus (see Matthew 1:20–21). The second chapter of Matthew continues with Jesus’s birth in Bethlehem, the family’s flight into Egypt, and Mary and Joseph’s relocation to Nazareth in Galilee. Again, each of these experiences is in direct fulfillment of ancient prophecy. [25]

Taken together, the details of the first two chapters of Matthew’s narrative reach a climax in the following words: “Now all this was done, that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by the prophet, saying, Behold, a virgin shall be with child, and shall bring forth a son, and they shall call his name Emmanuel, which being interpreted is, God with us” (Matthew 1:23; emphasis added; see also Isaiah 7:14).In other words, Jesus and Mary stand together at the meridian of time to fulfill centuries-old prophecies about the miraculous birth of the Son of God. Furthermore, the essential role of Mary in the life of Jesus becomes more accentuated when we consider that it would have been acceptable, even normal, in first-century Palestine to have written about the Son of God without even noting the woman who gave birth to Him. Again, given the lowly status of women at the time, it is remarkable that Mary receives such prominence in the opening lines of Matthew’s testimony. In this case, such a break from cultural norms lends credibility to the chronicle.

The Mark an account, generally recognized to be the earliest Gospel composed (a position we accept), is substantially leaner in details about Mary, the mother of Jesus. [26] His focus on her is designed to establish the difference between being in Christ’s physical family (father, mother, brothers, and sisters) and belonging to His spiritual family as a disciple (through conversion, calling, obedience, and loyalty). In every case, membership in His spiritual family prevails over membership in His physical family (see Mark 3:13–19, 31–35; 6:3–4).

Mark is the first Evangelist to recognize Mary as the mother of children other than Jesus (see Mark 3:31). Matthew, writing later, provides the names of the brothers (James, Joses, Simon, and Judas)and informs us that Jesus had sisters as well (Matthew 13:55–56).[27] Following the birth of the Savior, Mary and Joseph experienced the normal relationships between a husband and wife and had children of their own. This conclusion is supported by Matthew, who wrote, ”Then Joseph being raised from sleep did as the angel of the Lord had bidden him, and took unto him his wife: and knew her not till she had brought forth her firstborn son” (Matthew 1:24–25). This strongly implies a normal, intimate husband-wife relationship—the natural result of which would be children. [28]

With the picture of Mary surrounded by several children instead of just one, we may conclude that her life was anything but simple. Caring for Joseph along with five sons and at least two daughters would have created substantial domestic duties for Mary. According to Jeremias, she would have been responsible to “grind meal, bake, wash, cook, suckle the children, prepare her husband’s bed and, as repayment for her keep, to work the wool by spinning and weaving. Other duties were that of preparing her husband’s cup, and of washing his face, hands and feet.” [29] This portrait, couched first in Mark’s Gospel, allows us to view Mary as a prototype for female disciples in the first century. In Mark’s initial description of Mary, we find a typical woman of the day—she has a family to care for and a burden of domestic duties to look after. While she is part of Christ’s physical family, she is not yet part of His spiritual family (see Mark 3:31–35). The implied message of Mark is that even the mother of Jesus must embrace the gospel preached by Him and be ushered into His holy circle of influence. Her social status as a woman in Palestine cannot be viewed as an acceptable deterrent in her quest to join the spiritual family of Jesus and become a full-fledged disciple. [30]

It is apparent from Luke’s text that, like Mark, he is providing through Mary a pattern of discipleship. From Luke we will explore four characteristics of an ideal disciple exemplified by Mary: (1) regardless of socioeconomic status, humility yields goodness; (2) virtuous living instills beauty and conviction; (3) courage in the face of opposition is a hallmark of discipleship; and (4) discipleship requires strict obedience to the laws and ordinances of God.

Humility

Luke is the only Gospel writer who named Nazareth as Mary’s childhood home and the village wherein the Annunciation occurred. The insignificance of Nazareth was proverbial, as evidenced in Nathaniel’s exclamation, “Can there any good thing come out of Nazareth?” (John 1:46). Furthermore, the village is not mentioned in the Old Testament, the writings of Josephus, or the Talmud. Archaeological findings indicate that some two to four hundred people lived in the unwalled village in the first century. The remains of numerous winepresses, olive presses, caves for storing grain, and cisterns for water indicate that the economy of Nazareth was primarily agricultural with some craftsmen like Joseph in the population. [31] To be sure, Nazareth was virtually unknown in the Roman Empire and was distanced from major roads and significant trade. The evidence suggests that the small village could barely sustain the economy of a peasant class, meaning that acute poverty was the rule in Nazareth. [32] As will be seen, Mary belonged 60 to the ranks of the impoverished of Nazareth. It was to this village that the angel Gabriel was sent to visit the young girl Mary. From this visit we learn that humility is a core characteristic of Mary’s discipleship.

Luke explains that Gabriel “came in unto her,” suggesting that his visitation to Mary occurred indoors (Luke 1:28).[33] Given the domestic responsibilities that would have been hers by the time she was twelve to fourteen years of age, the angel’s appearance within Mary’s modest Nazareth home seems likely. Whatever the case, Gabriel employed language indicative of Mary’s chosen status, proclaiming that she was “highly favoured” and saying, “The Lord is with thee: blessed art thou among women” (Luke 1:28). According to Luke, Mary was not troubled by the presence of Gabriel but rather by his exclamations of favor in her behalf (see Luke 1:29). In her meekness, she silently wondered how she could be such a highly favored and blessed woman in the sight of God. Her humility is exemplary and places her in a category of Old Testament personalities such as Adam, Eve, Enoch, Abraham, Sarah, Rebekah, Rachel, and Moses, whose humility also yielded much goodness. [34]

Virtue

Gabriel announced to Mary that she would conceive and bring forth a son who should be named Jesus and who would be the ”Son of the Highest” and would “reign over the house of Jacob forever” (Luke 1:32–33). At this juncture, her silence was broken by her question to Gabriel: “How shall this be, seeing I know not a man?”(Luke 1:34). Such a bold and resolute response from Mary is the outgrowth of her disposition to strictly observe God’s commandment to live a chaste life.

Virtue was a fundamental aspect of Mary’s beauty. As we have seen, when Nephi beheld Mary in vision, he described her as “a virgin, most beautiful and fair above all other virgins” (1 Nephi 11:15). In this light, consider the words of David O. McKay: “There is a beauty every girl has—a gift from God, as pure as the sunlight, and as sacred as life. It is a beauty that all men love, a virtue that wins all men’s souls. That beauty is chastity. Chastity without skin beauty may enkindle the soul; skin beauty without chastity can kindle only the eye. Chastity enshrined in the mould of true womanhood will hold true love eternally.” [35]

In answer to Mary’s query “how shall this be?” Gabriel discreetly explained that “the Holy Ghost shall come upon thee, and the power of the Highest shall overshadow thee: therefore also that holy thing which shall be born of thee shall be called the Son of God” (Luke 1:35).Commenting on this verse, Elder McConkie wrote: “Our Lord was destined to have all of the essential experiences of mortality, including. . . birth in the natural and literal sense.” [36] Beyond this affirmation of Jesus’s literal son ship, little should be said except that Mary was chosen and found worthy to have the Holy Ghost come upon her, enabling the power of the Highest to overshadow her, allowing her to become the mother of the Son of God. Mary’s response to Gabriel’s annunciation was typical of the confidence, strength, and perception possessed by disciples who live above reproach. She said, “Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it unto me according to thy word” (Luke 1:38). This upright willingness cast Mary in the role of a type and shadow of the submissive disposition of her yet unborn son Jesus.

Courage

True disciples “stand as witnesses of God at all times and in all things, and in all places,” regardless of the pressures or conditions that are brought to bear upon them (Mosiah 18:9). Courage to stand, particularly in the face of opposition, is a hallmark of discipleship. In this regard, Mary may be grouped with Eve, Sarah, Zipporah, Emma Smith, and others as one of the most courageous individuals depicted in scripture. While there are several illustrations of Mary’s courage found throughout the Gospel accounts, Luke provides two examples that occur early in her life and that are associated with her initial experiences with motherhood. From them we learn that Mary possessed a courageous disposition at a very early age and maintained that characteristic throughout her life, as is evidenced by her intrepid action to stand by her son throughout His terrible ordeal at Golgotha.

First, sometime after conception but before her espoused husband Joseph had knowledge of her pregnancy, Mary traveled to the home of her aged relative Elisabeth. Mary had learned from the angel that Elisabeth was six months pregnant with John the Baptist (see Luke 1:36).It is likely that Zacharias and Elisabeth lived some ninety miles south of Nazareth in a city or village near Jerusalem. [37] The exact justification behind such an arduous journey by the youthful Mary is not known. Certainly, she would not have undertaken the potentially perilous trip without escorts. Perhaps Gabriel commanded Mary to travel to Judea. [38] It is also possible that Mary felt a need to assist her cousin in the last months of Elisabeth’s miraculous pregnancy. Elder McConkie provides an additional possibility. He wrote, “Gabriel’s announcement about Elisabeth was unspoken counsel to Mary to go and receive comfort and help from her cousin, whom she no doubt loved and revered—the inference is that Mary’s mother was dead—and who, being herself with child in a miraculous manner, could speak peace to the young virgin’s heart as no other mortal could.” [39] If Mary was motherless at the time of the Annunciation, conception, and birth of the Savior, we are left to afford her an even greater portion of praise for her courage and fortitude in the face of a potentially severe trial.

When Mary entered the home of Zacharias, her courage was rewarded by Elisabeth’s proclamation, “Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb. And whence is this to me, that the mother of my Lord should come to me?” (Luke 1:42–43).In her own modest way, Mary humbly deflected this praise, exclaiming,” My soul doth magnify the Lord, and my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Saviour” (Luke 1:46–47). At a time when most would bask in adoration, Mary magnified the Lord.

Second, following a three-month stay with Elisabeth, Mary returned to her home in Nazareth. Upon her arrival, family members, friends, and particularly Joseph learned of Mary’s pregnancy. In a state of shock, Joseph desired to “put her away privily,” which meant to annul the betrothal as privately as possible (Matthew 1:19). To have her betrothed husband believe that she had been immoral when she had not would be a crushing burden to bear. Furthermore, had Joseph divorced Mary, it would have left her and her unborn child in the most disastrous of circumstances socially and economically, the weight of which would have been a trial of monumental proportions for any woman of the day.

As we have learned, an angel appeared to Joseph in a vision to explain Mary’s condition and to encourage him to take Mary to wife, which he did (see JST, Matthew 1:24). Even so, it was too late to curb the rumors that undoubtedly flew through the small village and beyond. As Joseph’s reaction indicates, Mary’s pregnancy was viewed initially as sordid and shameful. For many, this perception persisted for over three decades. For example, while teaching at the temple during the Feast of Tabernacles about six months before His Crucifixion, Jesus was challenged by a group of Pharisees who rejected His testimony that He was ”the light of the world” and that true freedom could be obtained only by following Him, the Son of the Father (see John 8:12, 29, 31–32).His antagonists recoiled at this notion. Indeed, they claimed that they were of Abraham’s seed, were spiritually free, “and were never in bondage to any man” (John 8:33). Jesus responded by saying, “I speak that which I have seen with my Father: and ye do that which ye have seen with your father” (John 8:38). The Pharisees answered, “Abraham is our father” (John 8:39). Jesus then responded, “If ye were Abraham’s children, ye would do the works of Abraham. But now ye seek to kill me, a man that hath told you the truth, which I have heard of God: this did not Abraham. Ye do the deeds of your father [the devil]” (John 8:39–41; see also John 8:44). Likely out of deep frustration at their inability to counter Jesus’s words, they hurled a vicious accusation: ”We be not born of fornication” (John 8:41). This accusation may have been an allusion to spurious hearsay associated with Mary’s miracles conception over thirty years earlier. [40] If rumors regarding the birth of Jesus were still in circulation so many years later and had spread from the obscure village of Nazareth to the power centers of Judea, we may reasonably conclude that Mary faced such rumors from her early adolescence through her mid-forties and probably beyond.

These two examples from Luke suggest that Mary endured bitter trials in her life. In the face of loneliness, confusion, potential ruin on all fronts, and ongoing slander, she never turned from her son and His message. Her example is a testimony of courageous discipleship in the face of opposition.

Obedience

On the eighth day after the birth of Jesus in Bethlehem, Mary and Joseph were required to have Him circumcised and named, according to the law of Moses (see Leviticus 12:2). Forty days from the birth of Jesus, the law further dictated that He be presented to God at the temple. At this time, five shekels were paid as a symbolic redemption of the firstborn child (see Numbers 18:15–16; Exodus 13:2).Also, a lamb of the first year and a young pigeon or turtledove were to be offered for a burnt offering in behalf of Mary. This latter sacrifice was to ensure her ritual cleanliness before the Lord following childbirth (see Leviticus 12:4, 6–7). Luke recounts that Mary and Joseph obeyed these commandments (see Luke 2:21–24, 39), and it is through that obedience that spiritual strength and wisdom flowed into her at this time in her life.

As mentioned previously, in the early decades of the first century, Nazareth and poverty were virtually synonymous. Mary likely survived the first decade of her life with many deprivations, enjoying only bare sustenance. The Gospel of Luke suggests that in the days and weeks immediately following the birth of Jesus, Mary and Joseph lived a life of deep poverty. [41] Given their origins in Nazareth, this is not surprising.

Luke records that when the days of Mary’s purification were accomplished, she came with Joseph to the temple to offer sacrifice according to the law. However, instead of offering a lamb and a pigeon or turtledove, she offered only a pair of turtledoves. Under the law, not offering a lamb on this occasion was an option reserved for only the poorest of Israelites, who could instead substitute two turtledoves (see Leviticus 12:8). When we consider that Mary and Joseph anticipated this offering for months, we are left to conclude that only the deepest poverty could keep them from offering a lamb and a turtledove. Nevertheless, her offering was accepted, and blessings began to flow immediately because of her obedience.

A just man named Simeon was moved upon by the Spirit to be in the temple on the day that Jesus was presented to God. Simeon beheld Mary with the Christ child and took Him into his arms, exclaiming, “Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace, according to thy word: for mine eyes have seen thy salvation” (Luke 2:29–30). He then prophesied that Jesus would be a light to the Gentiles and the Israelites and that He would save many souls. To Mary he forewarned, “Yea, a spear shall pierce through him to the wounding of thine own soul also” (Joseph Smith Translation, Luke 2:35).

On the heels of Simeon was a righteous woman named Anna, whom Luke refers to as “a prophetess,” who served in the temple night and day. She also approached the Christ child and upon viewing the infant gave thanks to the Lord for allowing her to see the Messiah. She “spake of him to all them that looked for redemption in Jerusalem” (Luke 2:38). From Luke’s account we learn that strict obedience to God’s ordinances does not hinge upon temporal stability or social status. The genuine offerings of the impoverished are as valuable to God as the seemingly more extravagant offerings of the wealthy. Mary and Joseph were likely destitute, yet commitment to covenants over shadowed their poverty in the eyes of God. This deep devotion is a characteristic of all true disciples.

Furthermore, we learn that strict obedience will yield spiritual strength and added wisdom in the lives of disciples. Because of her obedience at a time when her poverty could have allowed shame or embarrassment to drive her away, Mary received prophetic confirmations of the divinity of her son through the words of Simeon and Anna. We may safely conclude that she took solace and strength from these confirming witnesses of Jesus’s role as the Light and Redeemer of the World. Also, Mary received added wisdom through Simeon’s forewarning of a spear passing through Jesus to the wounding of her soul. In other words, even though Jesus was the Son of God, Mary’s relationship with Him would be knit so closely that to wound Him would be to wound her. This insight was likely a comfort for an imperfect mother striving to rear a perfect son. Finally, these blessings emanated from Mary’s strict obedience to the law of God. We would do well to incorporate this characteristic of Mary’s discipleship into our lives.

Luke’s final reference to Mary is in the book of Acts, where she is found in company with the closest associates of the Savior. These disciples, men and women, were gathered in an upper room in Jerusalem, worshiping through prayer and supplication. In this scene, she is portrayed as the mother of Jesus but, more importantly, as a disciple of Jesus and a member of His spiritual family (see Acts 1:14).

From Luke’s depiction of Mary, we learn a great deal about discipleship. True disciples of the Savior are humble, virtuous, courageous, and obedient. Luke describes Jesus’s life between the ages of twelve and thirty as a time wherein He “increased in wisdom and stature, and in favour with God and man” (Luke 2:52). It is apparent from Luke’s account that as Jesus progressed from adolescence to adulthood, He had a noble pattern of discipleship to rely on—that of His mother. Like Mark and Luke, John paints Mary as a disciple progressing from the physical family of Jesus to His spiritual family. She is never referred to by her proper name; rather, John employs the appellations ”mother of Jesus” (John 2:1, 2, 5; 19:25–26) and “woman” (John 2:4;19:26). She appears only twice in the fourth Gospel—and then in contrasting fashion, acting in one way at the beginning of John’s Gospel and in a different way at the end.

For example, in John 2, Mary is at the wedding feast in Cana. Her concern for the shortfall of wine suggests that she was somehow associated with the hosts of the celebration. As the mother of the Son of God, she had abiding faith and an indisputable sense of Jesus’s divine powers. However, as this narrative illustrates, she had not yet developed a sensitivity for the timing of His mission. She imposed her membership in Jesus’s physical family to facilitate miraculous powers in a way that members of His spiritual family may not have done. Her request of Him to intervene was not evil or forbidden (after all, Jesus honored it), but it constituted a breach of timing, as His hour had not yet come (see Joseph Smith Translation, John 2:4).

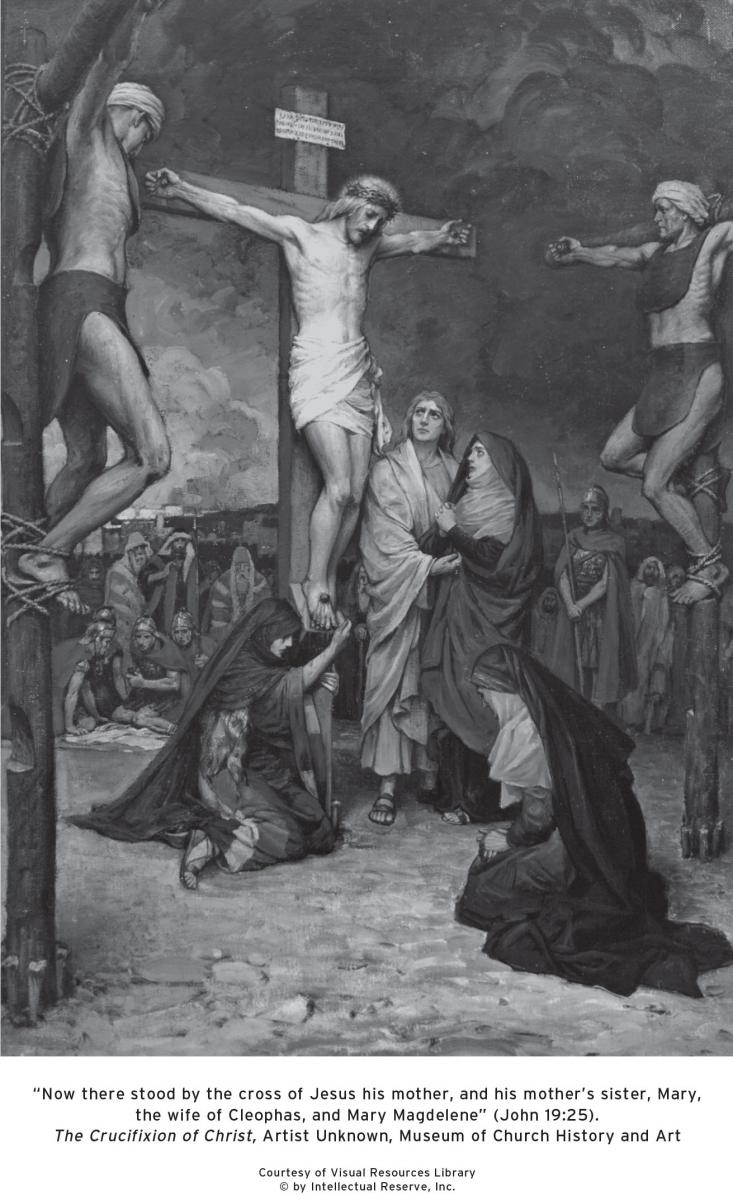

The second time Mary appears in John’s Gospel is at the Crucifixion. We are safe to conclude that watching her Son die was a soul-wrenching experience beyond description. Undoubtedly, her immediate motherly instincts yearned to see Jesus employ His divine powers to save Himself and be united with her physical family once again. However, she had matured in her discipleship. Unlike at the wedding of Cana, Mary clearly understood that Jesus’s hour had come. With John by her side, she suppressed her motherly desires, allowing them to be eclipsed by deeper spiritual desires (see Mosiah 3:19).

At this moment, Jesus beheld His mother standing next to John. The Gospel of John then reads, “He saith unto his mother, Woman, behold thy son! Then saith he to the disciple, Behold thy mother! And from that hour that disciple took her unto his own home” (John 19:26–27). According to F. F. Bruce, Jesus gave John a custodial charge over Mary because “the brothers of Jesus were still too unsympathetic to him 66 to be entrusted with her care in this sad hour; in any case, they may not have been in Jerusalem at the time.” [42] To be sure, Mary’s immediate physical needs were of concern to Jesus. However, we must consider an additional possibility beyond these temporary needs that may further explain Jesus’s exchange with Mary and John. It is possible that Jesus was communicating to His mother that her faith and devotion as a disciple had progressed dramatically since the wedding at Cana. Indeed, she had reached a level of discipleship wherein she was invited to enjoy an ongoing association with John and to stand shoulder to shoulder with the most beloved of Jesus’s disciples. [43] Again, given the status of Jewish women in Palestine in the first century, this proclamation is remarkable—if we are correct—and yet is a significant message of the Gospel of John. All people, old and young, bond and free, male and female, may progress in their discipleship to a point where they are ushered into the spiritual family of Christ. As it was with Mary the mother of Jesus, so it can be with us.

Mary Magdalene

While all four Evangelists include Mary Magdalene in their Gospels, only Luke mentions her in a narrative outside the events of the last week of Jesus’s life. Therefore, we turn to Luke for introductory insights to Mary and her role in the ministry of the Savior. Following Luke’s introductory ideas, we will turn our attention to Mary’s role during the Passion of Christ.

We have established the fact that Jesus was initiating a sociocultural reform in Jewish Palestine that brought previously unheard of freedom and mobility to some women of the day. From Luke we learn that Mary Magdalene, in company with a group of many women, embraced these freedoms and became an active disciple of Jesus, including traveling with Him during an extensive missionary tour of Galilee and later traveling with Him to Judea. Concerning the missionary travels of this band of female disciples, it has been written that “women did indeed leave their homes in Jewish Palestine, but only to travel to feasts, visit family, or attend to business, and this was only for a short duration. Women leaving behind family responsibilities would have been considered extremely a typical.” [44] Another writer notes that it was considered not only atypical but also scandalous by Jews of the day. [45] Furthermore, Mary must have been a charismatic leader, for it appears that she was the leader of this group of female disciples, being mentioned first in each listing of the most prominent members (see Matthew 27:56; Mark 15:41; Luke 8:2–3; Luke 24:10).[46] Finally, as unlikely as it was for Jewish women in first-century Palestine, Mary Magdalene and some of her peers were women of means who supported the ministry of Jesus with the resources at their disposal. Luke speaks of “certain women. . . Mary called Magdalene . . . and Joanna the wife of Chuza Herod’s steward, and Susanna, and many others, which ministered unto him of their substance (Luke 8:2–3; emphasis added).[47] While specifics are few, clues to Mary’s mobility and apparent fiscal independence may be found in her name.

Magdala (meaning tower in Hebrew), usually identified as Tarichae (meaning salted fish) in Greek, was a town located on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee about one mile north of Tiberias. [48] As the Greek suggests, Magdala was a prominent fishing town. Salted fish were an important export in the Roman Empire, making Magdala a prosperous center of business. [49] The appellation Magdalene is generally taken to mean that Mary came from Magdala. Since women of the day were usually known by a name that linked them to a man such as her husband, father, brother, or son (such as Joanna listed above), it is possible that Mary Magdalene was unattached. If this is the case, her financial security could have resulted from inheriting property in the area or from the proceeds of a Magdala business enterprise. Whatever the case, her commitment to Jesus’s ministry involved a significant financial element that was uncommon for a woman of that time period.

What moved Mary to be such a deeply devoted disciple of the Lord? Again we turn to Luke, who informs us that Mary had received a blessing and had been healed from infirmities inflicted by seven devils that had possessed her (see Luke 8:2). Details surrounding this healing are sparse, but Elder Talmage states that the priesthood blessing that healed Mary of physical and mental maladies was bestowed by Jesus Himself. [50] Given her temporary possession by evil spirits, we may picture Mary Magdalene as a grievously incapacitated person during that time. She was likely in a state of great mental, emotional, spiritual, and physical instability, unable to function normally in society. [51]

We are left to imagine the scene of her healing. Nevertheless, the scriptures capture a fairly uniform series of miraculous healings which we may draw upon as patterns. Jeni and Richard Holzapfel suggest that Jesus likely approached the incapacitated Mary in gentleness and love, assessed her condition, and felt compassion. He probably reached out to her, touched her, and pronounced words of priesthood blessing upon her. Healed and whole, she looked upon the Savior, and He lifted her up from her torment-torn bed or station and introduced her 68 to those in His company. Released from the pain of possession, her spirit soared, her charismatic personality was freed, her unflinching faith became unhindered, and her devotion was sealed. [52] Elder Talmage explains that from that moment on, “Mary Magdalene became one of the closest friends Christ had among women; her devotion to Him as her Healer and as the One whom she adored as the Christ was unswerving.” [53] Of her healing and subsequent discipleship, Elder McConkie wrote:

At some unrecorded time she was healed by Jesus from severe physical and mental maladies, and from her body the Master—of the seen and the unseen—cast out seven devils. Hers was no ordinary illness, and we cannot do other than to suppose that she underwent some great spiritual test—a personal Gethsemane, a personal temptation in the wilderness for forty days, as it were—which she overcame and rose above—all preparatory to the great mission and work she was destined to perform.

How often it is that the chosen and elect of God wrestle with physical, mental, and devilish infirmities as they cleanse and perfect their souls preparatory to the ministerial service they are called to render.. . . That Mary Magdalene passed whatever test a divine providence imposed upon her, we cannot doubt. And so we find her here, traveling with and ministering to the needs of the One who chose his intimates with perfect insight. [54]

From Luke’s early depiction of Mary Magdalene, we learn that he gospel of Jesus Christ breaks down all barriers that otherwise may hinder discipleship. Social, cultural, economic, spiritual, emotional, and even mental obstacles may be overcome through Christ. His invitation to join Him is a genuine outreach to all peoples of the earth. Furthermore, Jesus’s proposition is not just to join His Church and then idly stand by but to fully embrace His message and lead other sunder His direction.

Finally, all four Evangelists indicate that Mary Magdalene was a crucial figure in events surrounding the Crucifixion, burial, and Resurrection of the Lord. We believe that the most important role she played in the narrative of these events was that of special witness. The following chart is indicative of her part in these events and how her involvement builds in her personal and public witness of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ.

|

Gospel |

At Cross |

At Burial |

At Empty Tomb |

Witness to the Apostles |

| Matthew | 27:55–56 | 27:61 | 28:1 | 28:7, 9–10 |

| Mark | 15:40–41 | 15:47 | 16:1–2 | 16:7 |

| Luke | 23:49* | 23:55 | 24:1—8 | 24:9—10 |

| John | 19:25 | 20:14—16 | 20:17 |

*Of the four Gospel accounts, Luke alone does not place Mary by name at the Crucifixion. He does, however, report that the women who followed Jesus from Galilee witnessed the Crucifixion from “afar off” (Luke 24:49). As we have indicated, Mary was likely the leader of this group.

The first four columns (Gospel, At Cross, At Burial, At Empty Tomb) in the above chart are self-explanatory. The fifth column (Witness to the Apostles) captures Mary’s role as a witness and requires some explanation.

Matthew, Mark, and Luke each place Mary at the empty tomb where she is greeted by two angelic messengers. John’s narrative depicts Mary being met near the tomb by the resurrected Lord Himself. In each case (Luke excepted), Mary is commanded to go and find Peter and his remaining brethren of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and testify of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. [55] Because she was sent by heavenly ministrants, Mary Magdalene became a witness to the Apostles. [56] To be sure, Mary Magdalene was not an Apostle, but her divine selection to serve as the world’s first witness of the Resurrection of Christ is an honor of great magnitude. Indeed, as Holzapfel and Wayment explain, her testimony fulfilled the prophecy in the messianic Psalm that states, “I will declare thy name unto my brethren: in the midst of the congregation will I praise thee” (Psalm 22:22).[57]

Once again, we learn from the Evangelists that the discipleship and testimony of faithful women matter deeply to God, who is not bound by the social and cultural norms established by mortals. Mary found freedom in her discipleship—freedom to lead, to follow, and to offer credible testimony to men in the highest circles of leadership in the Church. Like Mary the mother of Jesus, Mary Magdalene was a spiritual pioneer of her day.

Mary of Bethany

This Mary comes from Bethany, a town located approximately one and a third miles east of Jerusalem. [58] She lived with her sister, Martha, and brother, Lazarus, whom Jesus raised from the dead. Mary was bold, fearless, and spiritually independent. Matthew and Mark do not mention Mary of Bethany in their testimonies. Luke and John, on the other hand, describe her as a faithful follower of Christ whose deep and endearing commitment to Him enable her to bravely shed traditional female roles of the day in favor of discipleship at the feet of the Master. We will

Examine two examples—one from Luke, the other from John—that illustrate Mary’s impressive commitment to Jesus and His teachings.

In Luke 10 we find Jesus in the home of Mary and Martha at Bethany. [59] It seems apparent that Martha is the older of the two sisters because she “received him into her house” and assumed the primary responsibilities of the hostess (Luke 10:38).[60] Mary, on the other hand, ”sat at Jesus’ feet, and heard his word” (Luke 10:39). This troubled Martha, who approached Jesus, asking that He intervene and encourage Mary to assist with the domestic duties of the home. Jesus answered by saying, “Martha, Martha, thou art careful and troubled about many things: But one thing is needful: and Mary hath chosen that good part, which shall not be taken away from her” (Luke 10:41–42).

This scene is singular in a variety of ways, but our focus will rest upon Mary. [61] With the approval of Jesus, it appears that Mary had broken free from her socially mandated role by leaving her domestic duties to sit at the feet of Jesus and receive instruction. In Mary’s day, learning in general, let alone at the feet of a renowned teacher or rabbi, was a privilege reserved solely for men. However, to further understand the stark departure from the norm in this case, we must appreciate that the phrase “at Jesus’ feet” is likely a technical way of identifying an active and accepted disciple. [62] Therefore, Luke communicates to the reader that discipleship overrules all other interests and social customs that may be brought to bear on an individual. Female discipleship was openly sanctioned by Jesus in this instance, and while Mary’s decision was unquestionably difficult, we learn from Jesus that such decisions will be judged by Jesus as “that good part” (Luke 10:42).

The four Gospels make it clear that Jesus made Bethany His headquarters during the last week of His life. Six days before the Passover, John informs us that Jesus was back in the home of Mary, Martha, and Lazarus, partaking of a meal with these close friends (see John 12).[63] Again, Martha paid her devotion to Jesus by serving Him food. While Martha’s service was significant and was appreciated by Jesus, Mary was again seated as a disciple at Jesus’s feet and was prepared to show a higher devotion. John records that Mary took “a pound of ointment of spikenard, very costly, and anointed the feet of Jesus, and wiped his feet with her hair: and the house was filled with the odour of the ointment”(John 12:3).[64] From Matthew we learn that she poured the ointment on Jesus’s head (see Matthew 26:7). Speaking of this anointing, Elder Talmage observed: “To anoint the head of a guest with ordinary oil was to do him honor; to anoint his feet also was to show unusual and signal regard; but the anointing of head and feet with spikenard, and in such abundance, was an act of reverential homage rarely rendered even to kings. Mary’s act was an expression of adoration; it was the fragrant out welling of a heart overflowing with worship and affection.” [65]

There is one additional element of the story that is stunningly atypical. Mary unveiled her hair and used it to brush, caress, and gently massage the costly spikenard into Jesus’s feet. [66] For a woman to uncover her hair in the company of anyone but her husband was an act of scandal in Mary’s day. The shock of her action likely resonated through the room and may have emboldened Judas Iscariot to rebuke Mary for her apparent excess (see John 12:4–5). Jesus immediately came to Mary’s defense, saying, “Let her alone: for she hath preserved this ointment until now, that she might anoint me in token of my burial” (Joseph Smith Translation, John 12:7).

What is the significance of Mary’s using her hair to gently spread the ointment on the Savior’s feet? A common practice of a slave owner in the first century was to use a slave’s hair to wipe excess oil or water off their hands at dinnertime. Therefore, it is possible on this occasion that Mary adopted the posture of a slave to manifest her absolute devotion to her Master and King. In a sense she was communicating what Mary, the mother of Jesus, said to Gabriel at the Annunciation—”Behold the handmaid of the Lord” (Luke 1:38).[67]

Mary’s act of anointing was inspired on at least two fronts: first, she likely fulfilled the prophetic Psalm, “thou anointest my head with oil”(Psalm 23:5); second, generally speaking, bodies were not anointed for burial until after death. Of this, JoAnn Seely writes: “Significantly, the anointing of Jesus took place while Jesus was alive, focusing on the richer meaning inherent in this act. The title Christ, or Messiah in Hebrew, means ‘anointed one,’ and Jesus came in fulfillment of Messianic prophecies.” [68] This idea is further captured by Elder McConkie, who wrote: “So Mary of Bethany . . . as guided by the Spirit, poured costly spikenard from her alabaster box upon the head of Jesus, and also anointed his feet, so that, the next day, the ten thousands of Israel might acclaim him King and shout Hosanna to his name. We see Jesus thus anointed and acclaimed, heading a triumphal procession into the Holy City.” [69]

Luke and John allow us to view Mary of Bethany as a bold and noble disciple of Christ. She would not allow her discipleship to be hindered by traditional views of womanhood. Luke’s Mary chose to manifest her discipleship by learning at the feet of Jesus. Similarly, John’s Mary marked her devotion by serving at the feet of Jesus. In the 72 end, our discipleship will also be measured by our willingness to learn and serve at the Savior’s feet.

Our study will now turn to the remaining four women named Mary in the New Testament. There is far less text involving these final Marys. However, sufficient detail exists to provide significant and helpful clues about the lives of these women. Even so, their biographical sketches will be significantly less detailed than those of the mother of Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Mary of Bethany.

Mary, the Mother of James and Joses

As we discovered in our discussion of Mary Magdalene, a goodly number of women followed Jesus during His Galilean ministry and later witnessed His crucifixion. Mary, the mother of James and Joses, was one of these women (see Mark 15:40; James being the English form of the Hebew Jacob, and Joses being the Greek form of Joseph).Matthew initially refers to her as the mother of James and Joses but then simply calls her “the other Mary” (Matthew 27:61). She is not mentioned in John’s Gospel.

It is reasonable to conclude that she was a very close associate of Mary Magdalene. Like her, this Mary also enjoyed a great deal of freedom and financial independence when compared to most women of the day. Mark tells us that she gave her personal resources to support the travels and ministry of Jesus (see Mark 15:41). Details related to her age, the age of her children at the time of Jesus’s ministry, her husband, and her source of economic security are virtually unknown Some suggest that Mary, the mother of James and Joses, is the same woman known as Mary of Cleophas (see John 19:25)—who will be described in the next section. While this is possible, we have not drawn this conclusion for three basic reasons. First, the text will not justify an absolute conclusion one way or the other in this case; second, Mary is a name used with such great frequency in first-century Jewish Palestine that it would be more reasonable to find more women, not fewer, with this name; and third, Matthew and Mark report that many women followed Jesus during His Galilean ministry and traveled with Him on His final journey to Judea (see Matthew 27:55; Mark 15:41). Taking these facts together, we believe that in this instance, identifying Mary of James and Joses as Mary of Cleoph as is overly harmonistic. [70]

With that said, we know that Mary the mother of James and Joses traveled extensively with Jesus, was taught by Him, and likely witnessed His miraculous power on multiple occasions. She was with Jesus on His final trip to Jerusalem and was probably one of the “many women” who witnessed the Crucifixion from “afar off” (Matthew 27:56). She observed the burial of Jesus, discovered the empty tomb with Mary Magdalene, and was greeted by angels who testified of Christ’s Resurrection early Sunday morning. According to Matthew’s account, Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of James and Joses were met by the resurrected Lord as they made their way out of the garden to share the glorious news with Peter and the rest of the Apostles (see Matthew 27:9–10).

Thus, while we lack many details about this Mary, we may safely conclude that she was a faithful woman who merited the trust and companionship of the Lord, that she was a close friend to Mary Magdalene, and that she was likely her peer in spirituality and charisma. She possessed a determination of soul sufficient to break from social norms of the day that would have viewed her ministry above and beyond her domestic obligations as scandalous. She gave freely of her substance to further Christ’s work and, most significantly, became one of the earliest witnesses of the Savior’s triumph over death.

Mary of Cleophas

John 19:25 is the only instance wherein Mary of Cleophas is mentioned by name in the New Testament. [71] She is likely the wife of a man named Cleophas, and since she is grouped with those who are close friends or relatives of the Savior, we may conclude that she enjoyed an ongoing access to this inner circle of disciples as either a close friend or perhaps a relative. John places her at the Crucifixion with Mary the mother of Jesus, Mary’s sister, and Mary Magdalene. In their company she was a witness to the fulfillment of the Old Testament prophecy that Jesus would experience thirst on the cross, which would be mockingly met with vinegar mingled with gall instead of water or wine (see Psalm 69:21; John 19:28–29). More importantly, she witnessed the concluding moments of Jesus’s mortal life as He proclaimed, “It is finished” (John 19:30).

While details surrounding the life of Mary of Cleophas are scant at best, John’s Gospel makes it clear that she was an important member of the group of women who ministered with and to Jesus. Again, the inclusion of a female witness to the Passion of Christ further illustrates the high regard the Evangelists had for faithful women of their day.

Mary, the Mother of John Mark

Luke, in the Acts of the Apostles, introduces his readers to “Mary, the mother of John, whose surname was Mark” (Acts 12:12). Her attachment by name to her prominent son, who was a missionary companion to Paul and who authored the Gospel of Mark, coupled with the fact that her house belonged to her, suggests she was a widow. [72] Luke lets us know that she was a woman of substantial means who lived in a rather lavish Jerusalem home including a courtyard, a wall with agate, and at least one servant (see Acts 12:12–14).

It is also apparent from Luke’s writings that Mary’s home was a primary meeting place for the Jerusalem Saints following the Resurrection of Jesus. The events described in Acts 12 occur in AD 44, [73] but her home was likely open to the Church much earlier. Indeed, she may have been in the “great company” of women from Jerusalem that bewailed and lamented Jesus as He made His way to Golgotha to be crucified. To this group, Jesus said, “Daughters of Jerusalem, weep not for me, but weep for yourselves, and for your children. For, behold, the days are coming, in the which they shall say, Blessed are the barren, and the wombs that never bare, and the paps which never gave suck” (Luke 23:28–29). It is also possible that she knew Jesus during His ministry, but the common suggestion that an upper room in her Jerusalem home was the place of the Last Supper is probably errant. [74]

The year AD 44 was a time of great persecutions at the hands of Herod Agrippa I, grandson of Herod the Great. In Acts 12:2 we learn that Herod Agrippa murdered James (the brother of John), who served as a counselor to Peter in the First Presidency of the Church. Peter was also imprisoned at this time. To be sure, Mary understood the peril associated with opening her home for Christian worship services as she did in Acts 12. From this we conclude that Mary, the mother of John Mark, possessed hearty zeal and determination as a disciple of Christ. These traits allowed her to raise a son who would author one of the four Gospel accounts and help shelter the Church through her temporal wealth. Without question, Luke’s desire is to convey to his readers that women may contribute to Christianity through personal faith, courage, motherhood, and hospitable service. [75]

Mary of Rome

Romans 16:1–16 is occasionally referred to as an ancient greeting card. [76] Paul recommends, greets, or commends twenty-eight individuals—a number of them women and some of whom were apparently his relatives (see Romans 16:7, 11, 21).[77] Mary of Rome is one of the twenty-eight. Indeed, Paul’s epistle to the Romans is entrusted for delivery to a woman named Phebe from Cenchrea (just outside Corinth), whom Paul also commissioned to conduct Church business in Rome (see Romans 16:2). In the letter, Mary is commended by Paul because she “bestowed much labour on us” (Romans 16:6). She is mentioned in company with Priscilla, who was deemed by Paul, along with her husband Aquila, to be “helpers in Christ Jesus: [having] laid down their own necks [for me]” (Romans 16:3–4). All others listed are commended for faithfulness as servants and ministers in the Church and are worthy of a salute from the Church of Christ (see Romans 16:16). How she came to join the Church is unknown, and there is no agreement as to whether she is a Gentile or a Jewish convert to Christianity. Even so, through commendation and the company she keeps, it is obvious that Mary is a faithful, upstanding, and fruitful member of the Church in Rome.

The exact way in which Mary “bestowed much labour” is not clear. However, Lampe and Witherington suggest that given the newfound freedom enjoyed by women in the first-century Church, Mary’s service exceeded her domestic responsibilities and included ecclesiastical duties. The translation rendered in the New Revised Standard Version may suggest a more active role for Mary as a disciple. It reads: “Greet Mary, who has worked very hard among you” (Romans 16:6; emphasis added).This rendering suggests that Mary of Rome was a spiritual caretaker in the city with her peers like Priscilla, Tryphena, Tryphosa, and her associate from Greece, Phebe (see Romans 16:1, 3, 12). Lampe suggests that Paul’s usage indicates that Mary was either a missionary or a woman of responsibility within the Roman congregation of Christians. [78] Again, this is certainly plausible when we consider the rise of freedom for women in the Church and the high-profile way in which Paul singles out her contribution in Rome.

In this light, what may be the most fascinating aspect of Paul’s brief greeting to Mary of Rome is the spirit of open camaraderie and fellowship in which it was given. More to the point, Romans was written by Paul from Corinth in about AD 58—meaning that only thirty years had passed from the time Jesus instituted sweeping reforms regarding women as disciples and active participants in Christ’s spiritual family. [79] Paul’s communication to the seventh Mary of the New Testament lets us know that Jesus’s preferred role for women as active and open disciples not only survived the initial decades of the Christian movement in Palestine but also spread with the expanding first-century Church.

Conclusion

Sorting out the seven women named Mary in the New Testament is more complicated than many students of the Bible anticipate. Even 76 so, our efforts lead us to know that an understanding of the historical and social context of women in first-century Palestine is critical. Within this context we learn that women of Jesus’s day generally experienced a status just above that of Gentiles and slaves. Without a connection to a husband or father, a woman was usually ostracized from society culturally, legally, and economically.

However, Jesus initiated a stunningly bold reform intended to invite and encourage the open participation of women in the Church as disciples and even leaders. Our survey provides an overview of how the four Evangelists and Paul portray these women and their roles in the early Church in light of the reforms Jesus instituted. Evidence of the changes associated with this reform is laced throughout the New Testament. Examples range from Mary Magdalene’s apparent leadership of female disciples, to Mary of Bethany choosing to learn at the feet of Jesus as His disciple and as a peer of her male contemporaries, to Mary the mother of John Mark hosting worship services in her Jerusalem home. Finally, our survey leads us to conclude that Jesus initiated these reforms in the face of opposing sociocultural pressures to ensure opportunities for women and all people to be more openly devoted to Him as disciples without hindrance. In the end, our careful survey of the seven women named Mary yields a rich and varied template for discipleship in the first century and today.

Supplementary Section: Charting the Seven Women Named Mary

The following chart provides a general concordance to the scriptural passages that name the seven Marys. In the case of Mary the mother of Jesus, she is so frequently (and exclusively in the Gospel of John) referred to as the mother of the Lord without being called Mary that these instances have been included.

The Seven Women Named Mary in the New Testament Matthew Mark Luke John Paul Mother of Jesus 1:16, 18, 20;2:11, 13–14,21; 13:553:31–32; 6:3 1:27, 30, 34,38–39, 41,43, 46, 56;2:5, 16, 19,33–34, 43,48, 51; 8:19; Acts 1:142:1, 12;19:25–27 Mary Magdalene 27:56, 61;28:115:40, 47;16:1, 98:2; 24:10 19:25;20:1, 11,16, 18 Matthew Mark Luke John Paul Mary of Bethany 10:39, 42 11:1–2, 19–20,28, 31–32,45; 12:3 Mary of James and Joses 27:56, 61;28:115:40, 47;16:124:10 Mary of Cleophas 19:25 Mary of John Mark Acts 12:12 Mary of Rome Romans 16:16

Notes

[1] Some suggest there are six, not seven, women by the name of Mary in the New Testament. The question arises in part from the way one reads and interprets John 19:25, which states: “But standing by the cross of Jesus were his mother and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Cleoph as and Mary Magdala.” If the sister of Mary, the mother of Jesus, is Mary the wife of Cleophas, then there are six women named Mary. However, this would mean that there are two daughters in the same family by the name of Mary. This is possible but unlikely. On the other hand, if the mother of Jesus is standing next to her sister (unnamed in John’s narrative)and another woman named Mary (of Cleophas), then there are seven. We are persuaded that the latter is true. Similarly, if the mother of James and Joses is the same woman referred to by John as Mary of Cleophas, then there are six and not seven women named Mary in the New Testament. While this is a possibility, we are persuaded that drawing this conclusion would be overly harmonistic (see Matthew 27:55–56; Mark 15:40–41; see also Ben Witherington III, Women in the Ministry of Jesus [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984], 120). We believe that the latter is true, leaving seven women by the name of Mary in the New Testament; see also F. F. Bruce, The Gospel and Epistles of John (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1983), 371.

[2] Ross S. Kraemer, “Jewish Women and Christian Origins,” in Women and Christian Origins, eds. Ross Shepard Kraemer and Mary Rose D’Angelo (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 35.

[3] David Noel Freedman, ed., The Anchor Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992), s.v. “Women.” For an overview of how women in the Greco-Roman world were viewed in the decades and centuries leading up to the ministry of Jesus, consult Jeni Broberg Holzapfel and Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, Sisters at the Well (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1993), 10–15; Anchor Bible Dictionary, s.v. "Greece,” “Hellenism,” “Roman”; Doren Mendels, The Rise and Fall of Jewish Nationalism (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1997), 13–33; John F. Hall, “The Roman Province of Judea: A Historical Overview,” in Masada and the World of the New Testament, ed. John F. Hall and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 1997), 319–36; Eric D. Huntsman, “Before the Romans,” in From the Last Supper through the Resurrection: The Savior’s Final Hours, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Thomas A. Wayment (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), 269–317; Cecilia M. Peek, “Alexander the Great Comes to Jerusalem: The Jewish Response to Hellenism, ”in Masada and the World of the New Testament, 99–112.

[4] Raymond E. Brown, The Birth of the Messiah (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1977), 123–25; Bonnie Thurston, Women in the New Testament: Questions and Commentary (New York: Crossroads Publishing, 1998), 14.

[5] Joachin Jeremias, Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1969), 368–69.

[6] Witherington, Women in the Ministry of Jesus, 3.

[7] Josephus, Antiquities, 4.8.15, in Josephus: Complete Works, trans. William Whiston (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 1960).

[8] Witherington, Women in the Ministry of Jesus, 9. Witherington disagrees with the claim of Jeremias that a woman’s word was generally unacceptable. Rather, he argues that in practice, her word was accepted even in some doubt fulinstances.

[9] See Philo, The Special Laws, 3.169–75, in The Works of Philo: Complete and Unabridged, trans. C. D. Yonge (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2000).

[10] Jeremias, Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus, 359–60.

[11] Ross S. Kraemer, “Jewish Women and Women’s Judaism(s) at the Beginning of Christianity,” in Women and Christian Origins, 61.

[12] Adolf Deissmann, Light from the Ancient East, trans. Lionel R. M. Strachan (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1995), 314–15.

[13] Holzapfel and Holzapfel, Sisters at the Well, 22, 25; see also Witherington, Women in the Ministry of Jesus, 13.

[14] It is possible to understate the role of women based solely on their contributions to society as defined by men. Shanks notes that “given the central position of the family in the economy and social organization of [Judah], the influence of women on society as a whole is assumed to have been pervasive despite their invisibility in the public record” (see Hershel Shanks, ed., Ancient Israel [Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1999], 164).

[15] Holzapfel and Holzapfel, Sisters at the Well, 22, 25; see also Peter Connolly, Living at the Time of Jesus of Nazareth (Bnei Brak, Israel: Steimatzky, 1988), 53.

[16] Elaine Pagels, The Gnostic Gospels (New York: Vintage, 1979), 61; see also Jeremias, Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus, 376; Richard Lloyd Anderson, Understanding Paul (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983), 111. Interestingly, conditions for this reformation on the greater socioeconomic stage of Palestine had become favorable. For a treatment of these changes, consult Martin Goodman, The Ruling Class of Judaea (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 51–75.

[17] James E. Talmage, Jesus the Christ (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1977), 475.

[18] Talmage, Jesus the Christ, 484.

[19] For an expanded treatment of these prophecies, consult S. Kent Brown, Mary and Elisabeth: Noble Daughters of God (American Fork, UT: Covenant, 2002), 13–18.

[20] Brown, Mary and Elisabeth, 15–16. For Noah, see Moses 7:42; for Aaron, see JST, Genesis 50:35; for Moses, see JST, Genesis, 50:29, 34; 2 Nephi 3:9–10,16–17; for John the Baptist, see Luke 1:13; for Joseph Smith, see JST, Genesis Sorting Out the Seven Marys in the New Testament 79 The Religious Educator • Vol 5 No 3 • 200450:33; 2 Nephi 3:15; for Jesus Christ, see 2 Nephi 10:3; 25:19; Mosiah 3:8.

[21] Bruce R. McConkie, The Mortal Messiah: From Bethlehem to Calvary (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1979–81), 1:326–27; see also Bruce R. McConkie, Doctrinal New Testament Commentary (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1987), 1:85.

[22] Talmage, Jesus the Christ, 86, 89; see also Brown, Mary and Elisabeth, 98. Another possibility is preserved by Eusebius in his Ecclesiastical History wherein is recorded an epistle by Julius Africanus (c. AD 160–240), who explained that “Eli and Jacob were brothers by the same mother. Eli dying childless, Jacob raised up seed to him, having Joseph, according to nature belongeth to himself, but by the law to Eli. Thus, Joseph was the son of both” (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, 1.7.16, in Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History, trans. C. F. Cruse (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2000).

[23] Beyond the four Gospels, Paul is the first to identify Jesus as a literal descendant of David. His epistle to the Romans, written in the mid-first century, confirms this fact (see Romans 1:3) as well as other writings (see 2 Timothy 2:8);see also Wolfgang A. Bienert, “The Relatives of Jesus,” in New Testament Apocrypha, ed. Wilhelm Schneemelcher, trans. R. McL. Wilson (Cambridge: James Clark, 1991), 1:471; Brown, Mary and Elisabeth, 38–39; Talmage, Jesus the Christ, 86.

[24] Elder McConkie suggests that Mary told Joseph of her pregnancy prior to her departure from Nazareth to visit Elisabeth in Judea and that for almost three months he was tested to the extreme as to whether he should divorce Maryor complete the betrothal contract through a formal marriage ritual. Near the end of this three-month period, Gabriel appeared to Joseph in a dream, confirming Mary’s story and the divinity of her son, at which time Joseph sent for Mary to return home (see Mortal Messiah, 1:332–33).Elder Talmage, on the other hand, suggests that Mary left for Judea and the home of Elisabeth without informing Joseph of her pregnancy. He learned that Mary was expecting a child when she returned to Nazareth three months later. Upon her arrival, she explained to Joseph the miraculous events that had transpired in her life, but he was not persuaded. Indeed, he was minded to divorce her as privately as possible. At this juncture, Gabriel appeared to Joseph in a dream and confirmed Mary’s report (see Jesus the Christ, 84–85).Ultimately, it is impossible to determine with certainty whether Joseph knew of Mary’s pregnancy before she left Nazareth for Judea or upon her return. Certainly, both possibilities should be considered. We are persuaded that Joseph learned of Mary’s pregnancy upon her return to Nazareth. One thing is certain: Joseph came to know of Mary’s pregnancy during the betrothal period.

[25] The prophecy that Jesus would be born in Bethlehem is found in Micah 5:2. The prophecy that Jesus would be taken to Egypt is found in Hosea 11:1. The prophecy that Jesus would live in Nazareth is not located in the Old Testament. Nevertheless, Matthew 2:23 makes it clear that a prophecy of ancient date existed and was generally known to Matthew’s audience.

[26] Anchor Bible Dictionary, s.v. “Mark, Gospel of.”

[27] Some apocryphal sources suggest that Joseph was a widower when he married Mary and that these additional children were his by a previous wife. This tradition is questionable, as it emerges at a late date without justification from earlier writings or the Gospel narratives. Given long-standing Jewish customs associated with marriage, the likelihood of an eighteen- to twenty-year-old Joseph being married to a twelve-to fourteen-year-old Mary appears to be more probable 80 (Brown, Mary and Elisabeth, 41; see also Protevangelium of James 9.2; “Extract from the Life of John according to Serapion,” in New Testament Apocrypha,1:467).

[28] See McConkie, Doctrinal New Testament Commentary, 1:280; see also Witherington, Women in the Ministry of Jesus, 99; Holzapfel and Holzapfel, Sisters at the Well, 123; Brown, Mary and Elisabeth, 41; David Noel Freedman, ed., Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2000), s.v. “Mary.”

[29] Jeremias, Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus, 369.

[30] It should also be taken into account that Mark 3:31–35 and Matthew 12:46–50 (both passages find Jesus teaching while His mother and brothers, but not Joseph, beckon for Him from outside) imply that Joseph is no longer alive. Christian tradition holds that Joseph died some time after Jesus was found teaching in the temple at age twelve and before His public ministry about eighteen years later. If this is indeed true, Mary was a widow during the critical years of the Savior’s ministry and would likely have been exposed to the previously mentioned cultural complexities associated with being a woman unattached to a husband. Even so, Mary embraced and then maintained discipleship in the spiritual family of Christ (see Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, s.v. “Joseph”; see also McConkie, Doctrinal New Testament Commentary, 1:281).

[31] John McRay, Archaeology and the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI:Baker Book House, 1991), 157–58; see also S. Kent Brown and Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, Between the Testaments: From Malachi to Matthew (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2002), 243.

[32] Economic conditions for Joseph and Mary may have changed somewhat following their flight to Egypt with Jesus and subsequent arrival in Nazareth. Joseph likely found work in Sepphoris, which lies about six kilometers (three to four miles) to the northwest of Nazareth. At the death of Herod the Great in 4 BC, his son Herod Antipas inherited this region of the Galilee. He claimed Sepphoris, acity which had been destroyed by Roman forces some years earlier due to revolts, as his capital city and began a vigorous rebuilding project. He recruited local artisans to perform the labor. As Joseph and Mary brought Jesus out of hiding in Egypt, Joseph likely saw the work projects of Antipas as a source of work and income (see Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, The Holy Land [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998], 374–77).

[33] Talmage, Jesus the Christ, 82; see also Brown, Mary and Elisabeth, 46.

[34] S. Michael Wilcox, Daughters of God (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1998), 170.

[35] David O. McKay, “True Beauty,” Young Woman’s Journal, August 1906,360; see also Wilcox, Daughters of God, 170–71.

[36] McConkie, Doctrinal New Testament Commentary, 1:83; see also Talmage, Jesus the Christ, 81.

[37] Brown, Birth of the Messiah, 331. If Zacharias lived in Jerusalem, Luke would have undoubtedly identified his hometown as such. Rather, when his days of service in the temple were accomplished, “he departed to his own house” (Luke 1:23), suggesting a journey beyond the borders of the city. The reality was that fewer than one-fifth of the priests who served in the temple lived in Jerusalem.

[38] Brown, Mary and Elisabeth, 28; see also McConkie, Mortal Messiah, 1:319.