Teaching That Leads to Enduring Conversion

Shon D. Hopkin, Ross Baron, Rob Eaton, and Philip Allred

Shon D. Hopkin, Ross Baron, Rob Eaton, and Philip Allred, "Teaching That Leads to Enduring Conversion," Religious Educator 25, no. 3 (2024): 107–36.

Shon D. Hopkin is a professor of ancient scripture and the chair of the Religious Education Department of Ancient Scripture at Brigham Young University.

Ross Baron is a visiting teaching professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University.

Rob Eaton is a visiting teaching professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University.

Philip Allred is a visiting teaching professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University.

The Book of Mormon is “like a vast mansion, with gardens, towers, courtyards, and wings.” Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

The Book of Mormon is “like a vast mansion, with gardens, towers, courtyards, and wings.” Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Abstract: This article includes four presentations centered on teaching that leads to enduring conversion. To integrate and nuance the concepts into a cohesive whole, the four ideas were followed by a dialogue discussion between the four authors. Following the dialogue, each presenter provided brief concluding thoughts. While this article follows the basic organization of the presentations, the authors have refined and expanded on the comments delivered at the conference.

Keywords: teaching the gospel, conversion, scriptures, youth, young adults

Teaching the Scriptures in Context

Shon D. Hopkin

Helping students understand the scriptures in context will bless their lives in at least three important ways:

- It will inoculate students against later concerns that their revelatory insights are invalid because they used the scriptures inappropriately or wrested the scriptures’ meaning.

- It will help the scriptures continue to enliven students intellectually as they glimpse the joyous worlds of historical and literary context, doctrine, and principles that remain to be explored.

- It will broaden and deepen the wellspring of revelatory possibilities that await students throughout their covenantal journey.

It is fascinating to note that when Christ finally descended to teach the Nephites—even though God himself talked with his people—he still pointed them to the teachings of both ancient and current prophets (see 3 Nephi 12:1; 20:11). Year after year, Latter-day Saints engage in a reading cycle that includes both canonized scripture and the words of living prophets who, like Christ, consistently employ canonized scripture in their teachings. Although the words of modern prophets change and adapt according to the needs of the time, with the scriptural canon, Latter-day Saints will read the same words again and again throughout their lives. It saddens me to hear returned missionaries say, “The scriptures have gotten boring.” A main reason they are bored is that they haven’t learned how to dig deeply into the scriptures, the exciting worlds to be explored within and beyond their pages. They haven’t understood how the scriptures function as a wellspring for current needs.

Elder Neal A. Maxwell famously described the Book of Mormon as being “like a vast mansion, with gardens, towers, courtyards, and wings.” He lamented that we “as church members sometimes behave like hurried tourists scarcely entering beyond the entry hall.” One of our principal tasks as religious educators, then, is to inspire our students to move beyond the entry hall of the scriptures and “go inside far enough to hear clearly the whispered truths from those who have slumbered—which whisperings will awaken in us individually a life of discipleship as never before.”[1] With that goal in mind, it becomes more important for religious educators to use their influence to help gospel readers unlock the full content of the scriptures when possible, rather than only pointing them to faith-promoting tidbits here and there. Helping students increase their enthusiasm to understand the full scripture text in context will unlock a new world of exploration that will challenge and expand their minds for the rest of their lives, fueling enduring conversion rather than only short-term gains, as important as those short-term gains often are!

The scriptural text of 2 Nephi 17 (compare Isaiah 7) serves as a helpful example of a chapter that students will likely read dozens of times over the course of their lives. The chapter heading states, “Ephraim and Syria wage war against Judah—Christ will be born of a virgin—Compare Isaiah 7.” The heading provides some helpful historical background to frame the content of the chapter. As students move into the text, however, they are confronted with a plethora of names and terms for which they likely have very little context. In just the first three verses they will find, in rapid succession: Ahaz, Jotham, Uzziah, Rezin, Syria, Pekah, Remaliah, Israel, Jerusalem, house of David, Ephraim, Shearjashub, and “the conduit of the upper pool in the highway of the fuller’s field.” For many, the processing part of the mind will quickly shut down and their scripture reading will become little more than a rote task to accomplish. Or they will begin to scan the chapter for the second item noted in the heading, happily finding this powerful witness of Christ when they arrive at verse 14: “The Lord himself shall give you a sign—Behold, a virgin shall conceive, and shall bear a son, and shall call his name Immanuel” (2 Nephi 17:14). This verse will serve as a powerful confirmation—often with an accompanying witness of the Spirit—of the reality of the miraculous birth and mission of the Son of God.

As important as that moment is, the challenge of understanding what is happening throughout the chapter is compounded by the subsequent verses which make clear that there is a time component with this sign: “Before the child shall know to refuse the evil and choose the good, the land that thou abhorrest shall be forsaken of both her kings” (2 Nephi 17:16). Either the sign is meaningless for Ahaz, the receiver of the sign in this chapter, because this child won’t be born for another seven hundred years, or the sign has meaning for Ahaz and thus cannot refer to the birth of Christ. In the end, most readers will simply decide that Isaiah is impossible for anyone but either the most erudite or the most spiritual to understand. His prophecies of Christ are powerful, but they appear magically in the middle of unintelligible texts and readers need to wait for someone else to tell them what they mean or when and how they matter. For many, this same reading process of rapidly scanning a seemingly impossible chapter and then jumping to the beautiful truth in verse 14 will repeat year after year, with the risk that the activity eventually loses its power or that the reader learns what the entire chapter means in context and decides that the powerful spiritual witness of the Savior they felt when reading verse 14 must have been false.

Hopefully, however, time can be devoted to helping the students understand the chapter in context, including President Jeffrey R. Holland’s statement that this prophecy has a “dual or parallel fulfillment.”[2] Coupled with the helpful detail that the Hebrew word translated as “virgin” in the King James Version of Isaiah 7:14 means “young woman of marriageable age,”[3] but that Matthew 1:23 is working from the Greek translation of the word (in the Septuagint) that literally means “virgin,”[4] students can then better understand the near-time fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy that would have been helpful to Ahaz. The scripture text is presenting the image of the all-powerful King Ahaz incapacitated by his fears while a young woman in Isaiah’s day, likely Isaiah’s own wife (see 2 Nephi 18:3–4), has sufficient faith to move forward and have a child, and that woman’s faith and that child’s birth is a sign that God is still with them. That near-time fulfillment then points even more powerfully to the meridian-time fulfillment in which the virgin, Mary, a young woman living under the threat of Rome, would have the faith and courage to believe the word of God and give birth to the child who would literally be Immanuel, “God with us.” With the ability to understand the scriptures in context—context that points even more powerfully to the later fulfillment in Christ—students can also recognize that they live in treacherous times as well. Broadening contextual understanding strengthens the witness of Christ gained through the students’ reading of 2 Nephi 17:14, even as they are fortified in their own courage and faith to carry forward God’s plan in their own lives, just as Isaiah’s wife and as Mary did centuries before.

Understanding the scriptures in context is a lifelong journey for all of us, including religious educators, and no one, no matter how well they may understand the scriptures, has arrived at the destination yet. We don’t need to self-recriminate for past or current weaknesses. Instead, as with our students, we can let the joy of exploring the scriptures continue to draw us forward into ever more-exciting worlds and vistas of understanding. Helping students understand the scriptures in context is an activity that is scalable according to the ability and needs of both teachers and students. It can be as simple or as sophisticated as time and ability allow and can include things such as helping provide an overview or summary of the text; literary context; historical context; and themes, patterns, connections, doctrines, principles, and invitations found in the scriptures. It is crucial to remember that this is not simply an academic exercise, but rather it is designed to help bring the scriptures to life as they point the students to modern prophetic teachings and most importantly to the Savior.

As we deepen our own capacity to understand the scriptures in context, we can be even more effective instruments in the Lord’s hands in helping our students study the scriptures in a way that leads to enduring conversion. How can religious educators embark on or continue this journey so they can better guide students? Doctrine and Covenants 88:118 encourages all of us to “seek ye out of the best books.” Excellent (but imperfect) sources include the tools found in the Church’s edition of the scriptures and Gospel Library study aids, Latter-day Saint study Bibles and commentaries, and wonderful study Bibles and scripture commentaries written by others. As these good books are used, it is important to remember that understanding scripture is the point, not reading something about scripture. It is also important to remember that none of these aids hold the same weight as canonized scripture or the words of modern prophets.

As religious educators teach the scriptures in context, it is crucial to recognize that one of the roles of modern prophets has always been to bring the scriptures to life to help with current needs. As they have done so, they have at times used the scriptures out of context in ways that provide strength to the message God needs his people to hear at the time. Indeed, it is nearly impossible to apply the scriptures at all without pulling them from their original context and introducing them into our own. From the Gospel of Matthew (see Matthew 1:23) to Nephi (see 1 Nephi 19:23) to Jesus Christ himself (see Luke 11:29, 3 Nephi 21), God’s messengers use scriptures for the current needs of their listeners, providing a connecting link of immediate relevancy. Teaching the scriptures in context provides an opportunity to show that very process to students, allowing the words of modern prophets and the way they use scriptures today to have full power in their lives even as the scriptural text itself, understood in context, provides ever-more-fertile ground for current and future revelatory experiences. To set up ancient scriptural context against the current context addressed by prophetic leaders ignores the authorized and Spirit-guided role of current leaders and ignores that this pattern has existed regularly throughout the centuries whenever prophets called by God have taught from scriptural texts.

Romans 8:16 provides a final helpful example: “The Spirit itself beareth witness with our spirit, that we are the children of God.” This verse is at times used to teach that we are literal spirit children of God, a concept that is eternally true and significant, but that is not what Paul was teaching. The chapter heading in the Latter-day Saint edition of the Bible—“Those adopted as children of God become joint heirs with Christ”—helps students understand the scripture in context, connecting powerfully with King Benjamin’s Book of Mormon message about the importance of being born again. Students can then read and understand Paul’s message throughout Romans 8, providing increased opportunities for encouragement and for revelatory experiences throughout their lives. Teaching the scriptures in context will also give teachers the opportunity to remind students that they are spirit children of a Heavenly Father and that the Spirit does bear witness of that reality, a truth that is taught regularly throughout the scriptures (see Numbers 16:22; Acts 17:28–29; Deuteronomy 14:1; Psalm 82:6; Hosea 1:10; Matthew 5:48; 6:9; John 20:17; Ephesians 4:6, and more).

When religious educators take time to help students understand the scriptures in their original context, they honor the original inspired message of the prophetic author in ways that also support the words of modern prophets. Doing so will help inoculate students against future concerns that their revelatory insights were incorrect, will encourage students to continue to explore the scriptures throughout their lives, and will give the scriptures more power to serve as a revelatory springboard. Teaching the scriptures in context helps lead students to enduring conversion.

Modeling Your Love for the Savior, His Prophets, and the Scriptures

Ross Baron

A crucial component in teaching that leads to enduring conversion is modeling who you are as a teacher. We, as gospel teachers, need to model our love for and testimony of Heavenly Father, his great plan, the Lord Jesus Christ, his prophets, and the word of God. Every time we come into class, the central focus should be the Savior, his prophets, and his word. As it states in Teaching in the Savior’s Way, “So no matter what you are teaching, remember that you are really teaching about Jesus Christ and how to become like Him.”[5] The students are watching us, not just for the content we teach, but the way we speak about and testify of the Savior and his living prophets. The students might not remember all the content we shared, but they will remember the Spirit of the Lord that we, as teachers, helped to bring into that class. It is that Spirit that will bless their entire lives as they learn to act and not to be acted upon. Just like the boy Joseph Smith, they can learn to say, “I have learned for myself” (Joseph Smith—History 1:20).

One of the key ways to do this is in the choice of questions you ask. There are many types of questions. Different situations and different levels of student maturity can guide in the kinds of questions we ask. President Henry B. Eyring stated, “To ask and answer questions is at the heart of all learning and teaching.”[6]

An example of using certain powerful questions to take a passage of scripture and focus on Jesus Christ is from 2 Nephi 2:27. Lehi teaches, “Wherefore, men are free according to the flesh; and all things are given them which are expedient unto man. And they are free to choose liberty and eternal life, through the great Mediator of all men, or to choose captivity and death, according to the captivity and power of the devil; for he seeketh that all men might be miserable like unto himself.”

When we are teaching, we need to remember that understanding the text precedes application of the text. Often, we want to rush to the modern application of a text, because we, as teachers, are so excited about it. Or we want to rush to a great analysis of the text. However, there is a process we must attend to with our students. Many students might not understand certain words, or they might not fully grasp the context. They might have a hard time identifying principles or doctrine in the passage or passages being studied. Hence, a teacher should start with doing “search questions.” Search questions are questions intended to help students slow down to understand and define words, phrases, concepts, principles, context, and doctrine. It ensures that the students are comfortable with what the text is saying. After the search questions, you can proceed to analysis questions and then on to the deeper application questions. After the search and analysis questions, students will often start to answer their own application questions without any prompting from the teacher because application flows organically and comes naturally as the Spirit of the Lord helps them.

The following are some examples of analysis questions from 2 Nephi 2:27. Please notice that the end focus of the analysis questions centers on Jesus Christ.

- What are some things you learned from Lehi in this verse that teach us about Jesus Christ?

- In what ways does the Savior give us liberty and eternal life?

- What are some reasons you believe we are “free to choose” because of Jesus Christ?

- One of the roles of Jesus Christ is to be our Mediator with the Father. In this verse, he is described as “the great Mediator of all men.” How does knowing that one of his roles is the Mediator of all men help you in having faith in him?

Next, I like to find prophetic quotes relating to the verses that we have studied. I call that “enhancing the text.” In this case President Nelson in October 2023 commented on this verse and said, “When you make choices, I invite you to take the long view—an eternal view. Put Jesus Christ first because your eternal life is dependent upon your faith in Him and in His Atonement.”[7] An analysis question that might follow this quote could be something like the following: Since this verse targets our capacity to make choices, what do you think President Nelson meant when he said, referring to this and other verses, that we should take “the long view”?

The examples given here of the questions about the text and the quote from President Nelson model for the students your testimony and love of Jesus Christ, the Lord’s prophet, and the word of God. Again, the students might not exactly remember everything you taught about 2 Nephi 2:27, but they will remember how you taught them and how they felt the Spirit of the Lord because you focused on Jesus Christ and the words of his prophets.

Depending on your class, you can ask questions that might be considered hard or more in-depth questions. These kinds of questions can strengthen faith and understanding in a powerful way. For example, in discussing 2 Nephi 2:27, you might ask something like this: Given that the Lord loves all his children and wants them to return to him, why would he give us this kind of freedom? This freedom presents the risk that some will not choose the Lord or his covenant path. How is that a manifestation of God’s love?

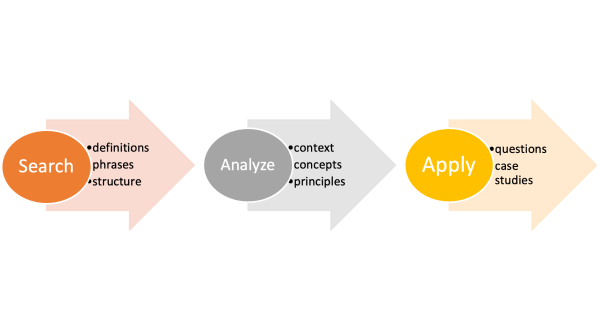

As instructors, model this flow of scriptural study questions in class. It will train students in this helpful discipleship skill when they are outside the classroom. The following is a graphic of how these Christ-centric questions flow:

Christ-centric questions

Christ-centric questions

All this reinforces what Elder Neil L. Andersen said when he taught, “Spiritually, the classroom of faith becomes less like a lecture hall and more like a fitness center. Students do not get stronger by watching someone else do the exercises. They learn and then participate. As their spiritual strength increases, they gain confidence and apply themselves all the more.”[8]

Teaching that leads to lifelong conversion is as much about the process which you model as a teacher, as it is about the content. One should not be sacrificed at the expense of the other. As guided by the Spirit, process and content can be harmonized to bless the lives of our students.

Beginning with the End of Enduring Conversion in Mind

Rob Eaton

When President Russell M. Nelson became the President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, one of the first invitations he extended to members of the Church was to “begin with the end in mind.”[9] His invitation was to live in a way that led to being endowed, sealed, and exalted. While he was talking to us in our individual capacity as disciples, imagine the power of beginning with those same ends in mind for our students as we prepare lessons and teach students. Approaching our classes with the end of enduring conversion in mind can shape every aspect of what we do, including which topics we choose to cover.

Beginning with the end in mind is essentially synonymous with a core concept from instructional design, backward design. Typically, if we are not especially intentional about how we design courses or prepare for individual classes, we begin by deciding what to cover, move on to considering how to cover it, and then—almost as an afterthought—consider how we might determine whether students have learned what we hope they will learn. Backward design invites us to reverse that process, beginning by considering what we want our students to know, to be able to do, and (in our case) to become because of our class. As instructional designer and author Julie Dirksen comments, “Before you start designing a learning experience, you need to know what problem you are trying to solve.”[10] Once we establish that, we then reverse engineer the learning experiences that will produce those outcomes.

When we focus more on what we want students to take away from our classes than on what we want to cover, we quickly realize the need to be more selective about just how many ideas we try to cover in each lesson. Years ago, my wife and I bought a couple of apple trees and were delighted when they produced loads of blossoms that soon transformed into little apples. But we soon learned that if you don’t thin the blossoms or the fruit, the trees produce a bunch of very small, almost inedible apples. Paradoxically, thinning blossoms produces more edible fruit.

Similarly, most of us have made the mistake of overloading our lessons with every concept from a reading block that seemed significant—only to be reminded of the myth that coverage equals learning. It does not. As the authors of a recent article on the “tyranny of coverage” concluded, “The science of teaching and learning clearly tells us that covering content is not the best way to help one’s students retain facts, core concepts, and competencies and then be able to transfer and apply their conceptual understanding to other situations.”[11] Thus, just as thinning blossoms produces more edible fruit, thinning the number of concepts we cover in a single class can produce more lasting learning.

Such an assertion is counterintuitive. But one study of how students who had taken different types of science courses fared in introductory science courses in college bore this out. Those whose high school courses had covered fewer topics in greater depth tended to perform better in their introductory science courses in college than those who had taken high school science courses that focused on breadth of coverage.[12]

Such a result may well be explained by the fact that “the drive to ‘cover content’ presents a formidable barrier to incorporating more learner-centered practices into undergraduate courses in general and into science and biology courses in particular.”[13] In other words, the more topics teachers try cover in a given class, the more prone they are to lecture—and the less likely they are to use the kinds of active-learning techniques proven to help students learn deeply.

One key to escaping this tyranny of coverage, the authors write, is to focus “a course on core concepts and competencies.” Doing that allows teachers to “move away from the goal of covering a breadth of material in a shallow manner to having students engage with a subset of material in more depth.”[14] Scott Knecht articulated this idea in the Religious Educator when writing about the myth of coverage: “The sooner a teacher lets go of the idea of coverage, the better will be the learning experience for his or her students.”[15]

For all of us who love the scriptures, thinning the material can be extraordinarily challenging. Few of us ever wonder how to fill up an entire class period. Instead, our constant challenge is making the difficult decision of what to leave out so that we can invest sufficient time exploring the most critical topics, allowing students to learn deeply. But how can we decide which topics to leave out, which to touch on lightly, and which to explore in-depth?

The authors of the article on the tyranny of coverage suggest teachers need to identify the concepts that are truly critical for our students to learn, a step they compare to a museum curating and displaying only certain artifacts rather than every artifact. “In teaching, curating involves identifying what core concepts and competencies are at the heart of what students should learn deeply and be able to use.”[16]

Mormon faced just such a curation conundrum when he abridged the Book of Mormon. Fortunately, Nephi gave all those who would write on his plates some invaluable guidance: “Wherefore, I shall give commandment unto my seed, that they shall not occupy these plates with things which are not of worth unto the children of men” (1 Nephi 6:6). As we begin with the end of enduring conversion in mind, that end will guide us to identify which “core concepts and competencies are at the heart of what students should learn deeply and be able to use”—in other words, the concepts of greatest worth to our students, those that are most spiritually relevant and most likely to facilitate enduring conversion.

Let me illustrate with two examples. The Sermon on the Mount is one of my favorite passages of scripture. Frankly, teaching it can be a challenge—precisely because it is so densely packed with rich doctrine. Consequently, thinning the concepts I choose to explore in class is especially difficult.

However, when I step back and consider the greatest challenges to the faith of the rising generation, following living prophets is near the top of the list. Consequently, I look for every opportunity I can to bolster my students’ commitment to follow living prophets. With that filter in mind, one verse that will survive my thinning process—whether I’m teaching the Sermon on the Mount from Matthew or 3 Nephi—is the beatitude the Savior introduces at the outset of the sermon in 3 Nephi 12:1. I want my students to hear the Savior’s words how he feels about those whom he calls to lead his Church: “Blessed are ye if ye shall give heed unto the words of these twelve whom I have chosen from among you.”

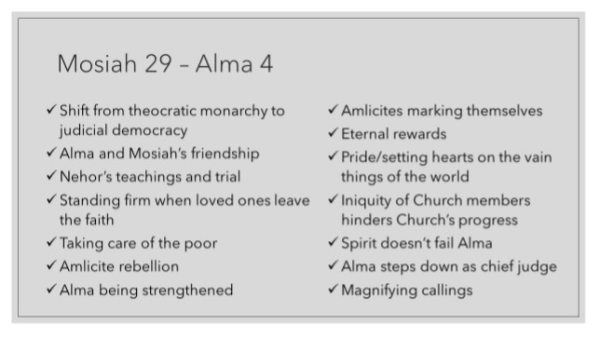

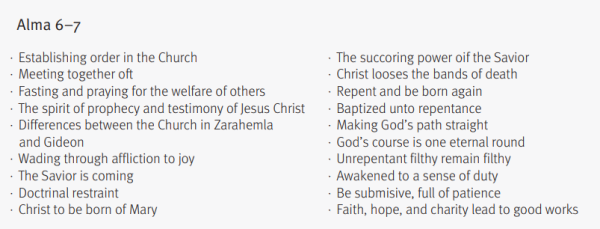

Figure 1. Topics of Mosiah–Alma 4

Figure 1. Topics of Mosiah–Alma 4

The second example is more comprehensive. I recently taught a Gospel Doctrine class as a substitute, and the scripture block consisted of Mosiah 29 through Alma 7. In figure 1, I’ve created a list of just some of the possible topics we could explore from Mosiah 29 to Alma 4. If I were subconsciously influenced by a desire to impress students with novel insights, I might spend several minutes discussing the shift from a theocratic monarchy to a more pluralistic judicial democracy, because I have some thoughts on that particular topic. In fact, I have about twenty pages of thoughts from a paper I wrote on that subject in law school.

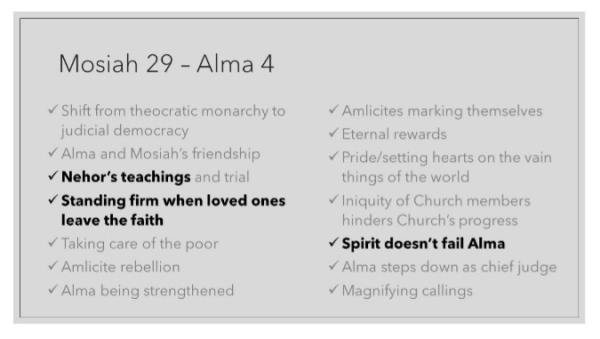

Figure 2. Selected Topics of Mosiah 29–Alma 4

Figure 2. Selected Topics of Mosiah 29–Alma 4

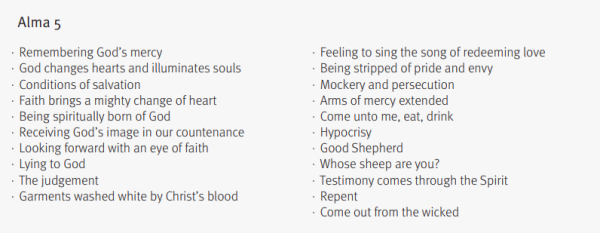

As you can see in figure 2, that topic and many others didn’t make the cut when I began my lesson and thinned with enduring conversion in mind. Instead, our focus for the first part of the lesson was on Nehor’s teachings and related concepts, such as how to discern and combat similar false teachings in our day. Similarly, rather than try to discuss all the topics identified in figures 3 and 4 from Alma 5–7, I asked a question that allowed us to discuss several of those topics under a unified heading: What do we learn from these chapters about how to experience and sustain a mighty change of heart? (figure 5).

Figure 3. Topics of Alma 5

Figure 3. Topics of Alma 5

Figure 4. Topics of Alma 6–7

Figure 4. Topics of Alma 6–7

Figure 5. Search question based on Alma 5–7

Figure 5. Search question based on Alma 5–7

In discussing that question, we did more than simply rehash things most students already knew. For example, we highlighted the phrase “baptized unto repentance” in Alma 7:14—a phrase that seems out of the usual sequence, in which repentance leads to baptism. I noted that this phrase appears ten times in the Book of Mormon and invited students to consider what it might mean. Finally, we noted that seeing the elements of the doctrine of Christ as repetitive and iterative elements of an ongoing process, as Elder Dale G. Renlund has taught, helps us live the doctrine of Christ in a way that produces enduring conversion.[17]

Taking a deeper dive into that concept was possible because I had thinned the number of topics we tackled in a single class. Painful as it was to omit a discussion of several other important concepts, beginning with the end of enduring conversion in mind helped me focus my attention on a smaller number of concepts that were especially critical.[18] Narrowing allowed for deepening. It also allowed us to spend a few minutes savoring Christ’s succoring power as described in Alma 7:11–13.

In conclusion, when we begin and thin with enduring conversion in mind, we choose differently when deciding what to explore in any given class. In fact, we choose better: we choose more spiritually relevant ideas of which the Spirit is more likely to testify with power. That allows us to teach with greater power, the very power our students need if they are to experience an enduring conversion themselves—the power of the Holy Ghost.

Revelatory Reading and the Revelatory Classroom

Philip Allred

In his inaugural address to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, President Russell M. Nelson highlighted our need for personal revelation. “If we are to have any hope of sifting through the myriad of voices and the philosophies of men that attack truth, we must learn to receive revelation.”[19] The prophet further emphasized that “in coming days, it will not be possible to survive spiritually without the guiding, directing, comforting, and constant influence of the Holy Ghost.”[20] Durable discipleship and lifelong conversion require our continuing connection to the Lord through the Holy Ghost.

In our CES classrooms, whether in Seminaries and Institutes, Ensign College, or any of BYU’s campuses, we are granted a remarkable opportunity to assist our students to “increase [their] spiritual capacity to receive revelation.”[21] In this article I will explore a way to transform a common learning activity—notetaking—into a more revelatory practice. The outcome is greater student recognition of revelation, both in their personal study and in their classroom experience. We’ll call this “revelatory reading and the revelatory classroom” because it actively engages students in one form of “the spiritual work required to enjoy the gift of the Holy Ghost and [facilitates them] hear[ing] the voice of the Spirit more frequently and more clearly.”[22]

Revelatory Reading

I first became aware of the revelatory aspect of scripture study as a catalyst for receiving the Spirit when President Dallin H. Oaks visited the Japan Osaka Mission, where I was serving in the mid-1980s. During a mission conference, he asked us what we did when we experienced what he called “zoning out” during our scripture reading. By “zoning out” he meant the time when we were awake and our eyes were following the text, but our minds were unconscious of the written words. One missionary said, “I go back over the page and find where I last remember reading and start from there.” I was amazed at President Oaks’s response. He said, essentially, “Please don’t do that—don’t go back over the words on the page, instead go back over the frames of your mind. Don’t review the text, review instead the frames of your mind—what were you thinking about? As you reflect, what do you see that is spiritually significant? Notice especially those promptings to act and be on errands of the Lord.”[23] From that day forward my study of the scriptures and the modern prophets’ teachings was richly enhanced by his apostolic insight. I began to then learn for myself how “the words of Christ will tell [me] all things what [I] should do” (2 Nephi 32:5).[24]

I was delighted several years later to discover President Oaks had expanded on this revelatory reading approach in an Ensign article to the Church and in some of his CES trainings. He taught, “It is not that the scriptures contain a specific answer to every question—even to every doctrinal question. . . . We say that the scriptures contain the answers to every question because the scriptures can lead us to every answer.”[25] How does this work? The Apostle explained that “even though the scriptures contain no words to answer our specific personal question, a prayerful study of the scriptures will help us obtain such answers. This is because scripture study will make us susceptible to the inspiration of the Holy Ghost, which, as the scriptures say, will ‘guide [us] into all truth’ (John 16:13), and by whose power we can ‘know the truth of all things’ (Moroni 10:5);” and this is true “whether or not that question directly concerns the subject we are studying in the scriptures. That is a grand truth not understood by many.”[26]

President Oaks further explained the relationship between scriptures and revelation, stating that “for us, the scriptures are not the ultimate source of knowledge, but what precedes the ultimate source. The ultimate knowledge comes by revelation.”[27] In an address to the Harvard Law School, President Oaks repeated and expanded this revelatory connection: “Thus, while Latter-day Saints rely on scriptural scholars and scholarship, that reliance is preliminary in method and secondary in authority. As a source of sacred teaching, the scriptures are not the ultimate but the penultimate. The ultimate knowledge comes by personal revelation through the Holy Ghost.”[28] Accordingly, “Because we believe that scripture reading can help us receive revelation, we are encouraged to read the scriptures again and again. By this means, we obtain access to what our Heavenly Father would have us know and do in our personal lives today. That is one reason Latter-day Saints believe in daily scripture study.”[29]

The Revelatory Classroom

There are likely multiple ways that revelatory reading could be applied in the classroom. One approach I have taken is a daily student activity called “My Learning Notes.” These personal notes facilitate individual spiritual reflection. It’s a metacognitive exercise; meaning that students track what they’re thinking about. In traditional academic settings (both secondary and collegiate), it is common for students to take notes in preparation for assessments. Motivated by test performance, students can fall into a dogged tracking of everything uttered by the instructor and every detail of the instructional materials. While this approach has an important place in knowledge acquisition, when the student is allowed to articulate what they are thinking about, among other virtues,[30] it specifically creates space for the Spirit to engage them in their learning. “My Learning Notes” purposefully transcends what I’m doing as their instructor—even beyond what they’re doing in the scriptures and the teachings of the modern prophets. This is student facing rather than instructor facing. It is vertical learning engagement (student–Spirit) in addition to the lateral learning experience (student–instructor or student–student). In the past I have thought of teaching by the Spirit as a function of what I’m doing as the instructor (both in classroom preparation and during my teaching). However, in the revelatory classroom, I think more about what they are doing to recognize and record the Spirit’s teaching. A particularly praiseworthy aspect of metacognitive notetaking is that it actively engages every student, including those who are vocally challenged and might only rarely, if ever, vocalize a question or share an insight in discussion.

What does this look like in my classroom? In the “My Learning Notes” instructions, I highlight the difference between assessment-preparation notes and this personal reflection on the spiritual incomings of the Holy Ghost.[31] Essentially, students write in first-person. Sentences and phrases feature references to “I,” “me,” and “my.” These notes are less factual about the content of the lesson or tracking with the flow of content specifics than they are relational with the Lord—an awareness of his will, errands, comfort, and direction to them individually[32] (which as President Oaks noted earlier may have little or nothing to do with the immediate class content). Additionally, “My Learning Notes” give each student the opportunity to track their own questions, ponderings, insights, and budding understanding, as well as a place to practice articulating the gospel in their own words and experiences. I’ve found it helpful to make a deliberate pause here and there during class to create space for them to write (sometimes these are planned before class while others are impromptu). I prompt their notetaking with something like the following: “OK, for the next ninety seconds, reflect and write what you are thinking about. What’s flowing over the frames of your mind? What are you learning or hoping to learn?”

Student Response Samples

Examples from some recent students’ learning notes are encouraging. Whether typed or handwritten, it is remarkable to see how the Spirit is directing them personally in ways that transcend my reach or capacity at the instructor. (Names have been changed for anonymity).

One student wrote: “I need to better understand temple covenants and what steps I am about to take with Brayden to get sealed. The better I know these covenants the more prepared I will be to receive revelation from God (specifically about temple covenants).”

Another noted in the middle of some doctrinal pondering: “Reminder: Appreciate the process, Aubrey”—indicating the receipt of a comforting perspective from the Spirit.

Another exclaimed, “I’ve never thought about it this way before,” later followed by a handwritten emphasis in all caps, “It really makes me WONDER what some of those are.”

A different learner jotted down a couple follow-up tasks for further reading [resources not mentioned in my instruction] and exclaimed: “Talk to Kylee about it!” This was followed by a “Beautiful Thought” containing two bullet points that connected with President Nelson’s childhood experiences and summed them up with “God can transform people into amazing disciples. He can transform me. It gives me hope, grateful for our living prophet.” So many students wrote about the Lord’s errands to minister to others, like, “Reach out to Elder Jones this week to follow up” and later in the same entry, “Reach out to Kaden to see when a good time to stop by would be this week and meet his roommates/

These representative student responses indicate the attractiveness of the effort to provide students with an ongoing workshop experience in the Spirit—to make our classrooms a practice ground for being vertically attuned to the workings of the Spirit of the Lord as we study the scriptures and teachings of the modern prophets. In this way, the revelatory classroom capitalizes on revelatory reading for personal edification and increased student discipleship, often in the form of invitations to minister on the Lord’s errand.

As we facilitate the revelatory classroom, we will be that much more aligned with President Nelson’s pleas to be more connected to the Holy Ghost. He deliberately bookended the October 2022 general conference with important references to the revelatory process. In that Saturday morning session he declared, “From this pulpit you will continue to hear truth”; therefore, “please make notes of thoughts that catch your attention and those that come into your mind and stay in your heart.”[33] President Nelson then closed the conference with his heartfelt hope “that you have recorded your impressions and will follow through with them.”[34]

Group Dialogue

Ross. Phil, with your ideas for creating a revelatory classroom, there may be the possibility that you could get some somewhat bizarre or outside of the box answers that may lead the student or the class in unhelpful directions. How do you create some guidelines and boundaries around the activity that would help increase the likelihood that it will be truly helpful?

Phil. I think it’s important to recognize that there is nothing that the Holy Ghost is going to reveal to any of us that will be at odds with Jesus Christ and his gospel or contrary to our Heavenly Father’s plan or his will for us. So, this is a training exercise. As students are thinking and recording thoughts, I’m inviting them and training them and teaching them how to check their thoughts against the Father’s plan, what they know about the teachings of the restored gospel, and what they know of the Spirit’s uplifting influence. As we triangulate those also with the living prophets, that adds to their skill set as lifelong disciples in discerning between the Lord’s voice as opposed to the adversary’s deceptions or the erroneous ideas of men. At times I’ll pause and ask the students if there is something that they’ve recently written that they feel would be appropriate to share with the class. Those are moments when we can share together and if needed do some of that housekeeping so they can see their ideas and incoming thoughts and impressions in the larger context of doctrinal synchronization.

Rob. I’ve watched Elder Bednar try to help us make this paradigm shift in the ways we listen in meetings.

Phil. It’s been helpful to start this approach from the very first day of class because I want this to be a consistent thing they are doing with their scripture studies at home, in Church meetings, as well as in the classroom. I review their learning notes regularly allowing me to see if they are working from the “I/

I think the shoe could be on the other foot regarding excellent questions, Ross, especially very challenging and hard questions. How do you guard against the very same issue of straying too far from the central doctrines of the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Ross. I do ask hard, open-ended questions. What I try to do from day one in class is emphasize the principle that no matter what we’re teaching, we are always teaching about Jesus Christ. In an open-ended environment, sometimes students will start to go off track a bit, and I gently but firmly will say, “How is that teaching us about the Savior? What are we learning about the Savior?” I’ve found that using that technique self-corrects. I’ve done this at the seminary level as well as the university level, and if I bring it back to the Savior and his prophets then the classroom and that individual will almost always stay centered.

Shon. A little bit of a revelatory insight occurred to me while we were discussing this presentation. I’ve always believed in the importance of teaching scriptures in context as well as showing how they link with the teachings of modern prophets. It dawned on me that if I only teach the scriptures in context, students don’t have any kind of training to know what the boundaries are for how they should apply the scriptures in their lives. As we teach some boundaries of what the ancient text means as well as the guidance provided by modern prophets, students will be better prepared to apply the scriptures in healthy ways. I think most of us have had experiences where somebody wants to share their new scripture idea with you and, as they start to share it, you think, “Oh, no. That’s going to lead to some really unhealthy behaviors. That’s an unhealthy application.” Modern prophets and what they are teaching, combined with ancient scripture, really help that process. In fact, prophetic commentary provides both boundaries and an illustration we can emulate of how to liken the scriptures to ourselves.

Rob, you discussed beginning with the end in mind and teaching for relevancy. How do you make sure that doesn’t just turn into using the scriptures for a couple of cherry-picked ideas in which they only briefly serve to launch you into an entire concept that you really want to discuss, rather than staying grounded in the scriptures? If you’re going to go for high relevancy, how do you also then teach in a way that can give long-term payoff with students truly understanding them in context?

Rob. I think you’re also asking how to avoid simply devotionalizing the scriptures. When I think of devotionalizing, I think of things like pictures of cats with spiritual captions or something akin to fried froth. I think of spiritual platitudes. I think of things that are spiritually superficial. So I’m glad you asked this question because I want to be clear that this approach is not one that suggests we should be shallow in our teaching or learning. In Doctrine and Covenants 9:7–8, the Lord teaches: “Behold, you have not understood; you have supposed that I would give it unto you, when you took no thought save it was to ask me. But, behold, I say unto you, that you must study it out in your mind; then you must ask me if it be right.” That counsel suggests to me that to help our students gain spiritual insights, we’ve got to pay a price and help them pay a price.

President Nelson himself has said to “make time to study His words. Really study!”[35] In fact, he models this for us as he uses intellectual rigor to produce spiritually relevant insights. Thinning how many topics we cover in a class makes it more possible to dig deeply and lay a foundation, but always with spiritual payoff in mind. For example, I recently sat in on the class of a talented, knowledgeable colleague who spent the whole hour laying a linguistic foundation for a profound spiritual point he wanted to make. It was unquestionably intellectually enlarging, but the intellectually larging foundation led to a spiritually strengthening, culminating thought about the meaning of the phrase “I Am that I Am.” He stretched their minds, but not just for the sake of abstract intellectual growth; he did it in the service of deepening their faith and their discipleship and their connection to God.

That said, I admit there is a danger of doing something I have been guilty of at times as I go into depth into a smaller number of topics instead of covering so many. It’s the temptation to have a whole lesson on a couple of topics that might be covered by only two verses in the whole block. I think we’ve got to do justice to the scripture block. It helps to choose some topics that are laced throughout the scripture block so that we can draw from many different passages within the assigned section. And we always need to take the time to provide the context so that we aren’t wresting scriptures out of context.

Phil. In fact, if I might add, for the revelatory classroom we need to provide the Spirit accurate material to work with. If the Holy Ghost testifies of truth, but we aren’t teaching truth, or if we’re not pulling truths from the words of the prophets and the scriptures, then there’s less opportunity for the Spirit to bear witness. If so, our classrooms may be informational, at best, but not transformational.

Rob. I’ll just add one thought. I loved how you talked about the excitement of going from discovery to discovery. I’m always teaching scripture-based classes with the goal of helping students develop the study skills and the capacity to be great readers of scripture themselves so that they will become lifelong serious students of the scriptures. I think that is a perfect end to have in mind. When we think about what will facilitate enduring conversion, one of the best ways to do that is to help our students learn to study the scriptures so well that they will want to do it for the rest of their lives.

Ross. I look at every single class as my small plates, and then I have only so much time. I have to do that which is of most worth, so I don’t want to have a spiritual meme. I want to teach the scriptures in context, but I also realize some things might have to be thinned.

Shon. We should probably add that this is all aspirational. This is what we try to do but that we all do imperfectly. We all stumble and need to self-correct and improve over the course of every class we teach.

Rob. President Reese this morning talked about a couple of BYU’s Aims of being intellectually enlarging and spiritually strengthening. Sometimes I hear people talk about these as if they’re competitors. How do you balance those two? How do you do both?

Shon. I think we all agree that these must not be competitors. Learning is a whole-bodied, joyous, mental-spiritual-physical exercise. We worship God with the heart, the mind, and the soul. But sometimes they do feel a little bit different, and you have to make sure that both the mind and spirit are being enriched. I’ll prepare students by saying something like, “If you feel at any point like we’ve spent too much time on history, data, or concepts, hang in there because we will move over into application soon. If you feel like we are talking way too much about feelings, hang in there, because we will zero in on some things like literary or historical context soon.” A good class will enrich both the heart and the mind.

Ross. You come to class prepared in the text and you know the prophets’ teachings about the text. You’ve studied the scriptures, maybe some Bible commentaries, and words of modern prophets. You come in ready, and I think that when the students see that kind of approach, that is intellectually enlarging and spiritually strengthening, they recognize that they’re not competitors. They see you model it and they know you love it. I’m going to bring Hebrew insights and we’re going to bring in historical things, but at the same time we’ll talk about why those things matter in the students’ lives today.

Phil. I love that as we amplify the modern prophets’ teachings, it also shows their intellectual capacity as they engage the word of God in both ancient and modern contexts. Helping our students see the prophets processing that in intellectually responsible ways becomes a double cure: the students learn more truth and their confidence in the Lord’s anointed also increases.

Rob. We can’t expand souls without stretching minds. But we’ve got to make sure we close the loop, because stretching minds alone isn’t enough. Law school stretched my mind, but it didn’t expand my soul. So I’m always going to be looking for intellectually enlarging ways to teach that lead to spiritual strengthening.

Concluding Thoughts

Phil. Are there protective banks to the cascading flow of thoughts and impressions that come while reading the scriptures and engaging in the classroom? Drawing on Elder Dale G. Renlund’s October 2022 general conference address, “A Framework for Personal Revelation,” several gatekeeping questions will help our students avoid wresting the scriptures and the teachings of our modern prophets.

- Is the experience consistent with scriptural teachings about the Lord’s revelation?[36]

- Is what is received within my purview, or does it tread on the prerogative of others?[37]

- Is the thought aligned with the doctrine of Christ, God’s commandments, and “the covenants we have made with Him?”[38]

- Is the direction in harmony with my previous personal revelation from the Lord?[39]

If we practice applying these checks regularly in the classroom, our students will more likely gain the lifelong discipleship skill of discerning between revelations from the Spirit of the Lord versus the “doctrines of devils, or the commandments of men” (Doctrine and Covenants 46:7).

I have been delighted and blessed to see my students grow in their consciousness of the Holy Ghost’s individualized inspiration and instruction to them. As religious educators, our efforts to create space to recognize and record the Holy Ghost’s personal edification provides the Lord an additional avenue for him to deepen our students’ conversion and quicken their discipleship.

Rob. Phil’s presentation and Elder Gilbert’s story during the 2024 CES conference about seeing a supportive a young men’s leader at his track meet both reminded me about a concept I have been thinking a lot about lately: revelatory catalysts. Anything the Lord uses to provoke revelation in our lives could be considered a revelatory catalyst, from Joseph Smith’s translation of the Bible to affliction to the gesture of a supportive Young Men leader showing up at a track meet, as Elder Gilbert explained in his remarks.

Providing revelatory catalysts is a simple but important way to facilitate enduring conversion in our students’ lives. As I have pondered today what I can do to provide more revelatory catalysts to my students, two thoughts came to mind. First, it would seem a shame to talk about how to better facilitate enduring conversions without quoting this gem from Preach My Gospel: “The Book of Mormon, combined with the Spirit, is your most powerful resource in conversion.”[40] That makes me want to do what I can in whatever class I am teaching to help connect students with that powerful revelatory catalyst.

Of course, as amazing as the Book of Mormon and the scriptures are, there is no salvation in them. As the Savior teaches us in John 5:39, the scriptures point us to him, and salvation is in him. Perhaps that is why they are such a powerful revelatory catalyst—because they point us to the Savior, who himself may be the ultimate revelatory catalyst. As Ross reminded us and President Nelson has taught, “Nothing invites the Spirit more than fixing your focus on Jesus Christ. Talk of Christ, rejoice in Christ, feast upon the words of Christ, and press forward with steadfastness in Christ.”[41]

Elder Neil L. Andersen further explained, “If you ever wonder what to say, speak the words of the Savior. Speak of His experiences; speak of His parables; speak the words of scripture of and of prophets testifying of Him. As we teach and testify of Jesus Christ, the Holy Ghost will confirm in the hearts of our young disciples the truth of His life and teachings with a power far more lasting than the power of our own teaching.”[42]

When we teach our students about the Savior, hearing of Him provides the ultimate revelatory catalyst—a special opportunity for them to feel the powerful, lasting witness of the Spirit. Perhaps that is the single best way, then, to facilitate enduring conversion.

Ross. Years ago, I was called to be a volunteer early morning seminary teacher in Southern California. My first year teaching, I had eighteen amazing students. The class was at six o’clock in the morning. If I had to honestly assess myself as a teacher of that class, I would say (as kindly as possible) I was a disaster. Please know that I loved my students, I loved the gospel, and I loved the scriptures. However, I was really not that good. I did not have the skills or the understanding of teaching to fully achieve the aims of Church Education. However, I had a Church Educational System coordinator who kindly mentored me and taught me. I wanted to learn, and I wanted to be better. By the third year, in a different ward, I had thirty-three 15-year-olds at 6:00 a.m. This time, because of skillful mentoring from my CES coordinators, I had one of the most amazing experiences of my life. I had grown, and I had tried to incorporate and to put into practice what I had been taught.

One of the reasons I wanted to be better was because I wanted to follow the Savior and be an instrument in his hands to bless the lives of those in my class. A guiding principle in all I do when in a class is inspired by this teaching from President J. Ruben Clark Jr. He said, speaking of teachers in a classroom, “As you enter there, you stand in holy places that must be neither polluted nor defiled, either by false or corrupting doctrine or by sinful misdeed.”[43] The Lord told Moses, as Moses approached the presence of the Lord in the burning bush in the wilderness, “Put off thy shoes from off thy feet, for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground” (Exodus 3:5).

I believe our classes, somewhat like the burning bush, are “holy ground.” I feel this when I walk into a classroom. I am on sacred, holy ground. I hope you feel that whether you are teaching the fifteen-year-olds on Sunday, an early morning seminary, or you are at a university class. God, in his kindness and mercy, has given us entrance into the hearts of our students. Hence, this is a powerful opportunity for all of us, and we need to stand faithfully to our charge to bear witnesses of Jesus Christ, the restoration of the Father’s plan, and of his living prophets. As we do that, we will receive help from mentors from the Lord and from the Lord himself because we are on his errand with his children.

Shon. Ross mentioned the reality that religious educators are given a trusted and sacred position of entrance into the hearts of our students. Who we are matters. In our weakness, in our imperfections, and in our humanness, but in our faith, our love, and our passion for the word of God, for the restored gospel for Jesus Christ, and for our Savior Jesus Christ, who we are matters. What we are hoping to achieve is that the barrier between teacher and students becomes permeable, so that when we speak it does not bounce off a cement wall or appear in a thought bubble above our heads. Instead, we hope to pull in our students and persuade them to love what we love, to explore what we explore, and to be devoted to what we are devoted to. This happens most powerfully and effectively when teachers teach from converted souls. As President Gordon B. Hinckley taught, “Teaching is the essence of leadership in the Church.”[44]

I love and regularly quote the following statement made by President Joseph F. Smith:

Leaders of the Church, then, should be [those] not easily discouraged, not without hope, and not given to forebodings of all sorts of evils to come. Above all things the leaders of the people should never disseminate a spirit of gloom in the hearts of the people. If [those] standing in high places sometimes feel the weight and anxiety of momentous times, they should be all the firmer and all the more resolute in those convictions which come from a God-fearing conscience and pure lives. . . . It is a matter of the greatest importance that the people be educated to appreciate and cultivate the bright side of life rather than to permit its darkness and shadows to hover over them. In order to successfully overcome anxieties in reference to questions that require time for their solution, an absolute faith and confidence in God and in the triumph of his work are essential.[45]

What a joy it is to work as a united body of religious educators who have this confidence of the truth and are trying to help instill it and encourage our students to gain and exercise that confidence in the perfect one, the Savior Jesus Christ, and in the gospel that points to him.

Notes

[1] Neal A. Maxwell, “Great Answers to the Great Question,” Brigham Young University devotional, October 11, 1986, https://

[2] Jeffrey R. Holland, “‘More Fully Persuaded’: Isaiah’s Witness of Christ's Ministry,” in Isaiah in the Book of Mormon, ed. Donald W. Parry and John W. Welch (FARMS, 1988), 6.

[3] Francis Brown, S. R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs, eds., The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (Press, 1906), 761.

[4] John Oswalt, The Book of Isaiah, Chapters 1–39, New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Eerdmans, 1986), 211.

[5] Teaching in the Savior’s Way (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2016).

[6] Henry B. Eyring, “The Lord Will Multiply the Harvest,” satellite broadcast address to religious educators in the Church Educational System, February 6, 1998, 5–6.

[7] Russell M. Nelson, “Think Celestial,” general conference talk, October 2023.

[8] Neil L. Andersen, “A Classroom of Faith, Hope, and Charity,” broadcast for instructors and personnel in the Church Educational System, February 28, 2014.

[9] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “We Are Going to Start with the End in Mind,” Church News, May 4, 2018.

[10] Julie Dirksen, Design for How People Learn (New Riders, 2016), 60.

[11] “The Tyranny of Content: ‘Content Coverage’ as a Barrier to Evidence-Based Teaching Approaches and Ways to Overcome It,” NCBI, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

[12] “The Tyranny of Content,” 5.

[13] “The Tyranny of Content,” 2.

[14] “The Tyranny of Content,” 5.

[15] Scott H. Knecht, “The Myth of Coverage,” Religious Educator 12, no. 1 (2011): 119.

[16] “The Tyranny of Content,” 3.

[17] Dale G. Renlund, “The Powerful, Virtuous Cycle of the Doctrine of Christ,” general conference talk, April 2024, paras. 7–8, www.churchofjesuschrist.org.

[18] I am not suggesting that using the end of enduring conversion as a filter for thinning the topics we choose will or should always produce precisely the same result of topics. To the contrary, when we are guided by the Spirit, who knows the needs of our individual class members, we will often be prompted to add or omit certain topics based on what will most help students in each class.

[19] Russell M. Nelson, “Revelation for the Church, Revelation for our Lives,” general conference talk, April 2018. Note how this dovetails with one of the three discipleship outcomes for our students in the Strengthening Religious Education document (2019) from the Board of Education to all CES religious education instructors and faculty at college-level institutions of higher education: “Strengthen their ability to find answers, resolve doubts, respond with faith, and give reason for the hope within them in whatever challenges they may face.”

[20] Nelson, “Revelation for the Church.”

[21] Nelson, “Revelation for the Church.”

[22] Nelson, “Revelation for the Church.”

[23] Paraphrased from personal notes, mission journal, February 26, 1987.

[24] Nephi clearly had revelation in mind as he pleaded for his people to “press forward, feasting upon the word of Christ” (2 Nephi 31:20), but was dismayed that they were “ponder[ing] in their hearts concerning that which [they] should do” now that they had commenced along the covenant path (2 Nephi 32:1). Apparently, Nephi’s people did not recognize the role of the Spirit in continually directing their lives with the words of Christ. Nephi clarified, “[Angels] speak the words of Christ: wherefore, I said unto you, feast upon the words of Christ; for behold, the words of Christ will tell you all things what ye should do. . . . if ye will enter in by the way, and receive the Holy Ghost, it will show unto you all things what ye should do” (2 Nephi 32:3, 5). Similarly, today, we may assume that “feasting on the word of Christ” is simply a reference to scripture study. Instead, to “ask” and to “knock” (2 Nephi 32:4) while in our scripture study, or to practice revelatory reading, could be one approach to growing into the principle of revelation.

[25] Dallin H. Oaks, “Studying the Scriptures,” unpublished Thanksgiving devotional to seminaries of Salt Lake and Davis counties, November 24, 1985; cited in Scripture Study—The Power of the Word Teacher Manual, 45; emphasis in original, www.churchofjesuschrist.org.

[26] Oaks, “Studying the Scriptures,” 1985.

[27] Dallin H. Oaks, “Scripture Reading and Revelation,” Ensign, January 1995, www.churchofjesuschrist.org. In this article President Oaks explores the canonicity properties of our standard works, particularly our latter-day claims that the canon is “open.” Religious educators would be well served by reviewing his Restoration-grounded approach to what many of our Christian counterparts consider to be a “closed canon.”

[28] “Fundamental Premises of Our Faith - Talk Given by Elder Dallin H. Oaks at Harvard Law School,” Newsroom, February 26, 2010, https://

[29] Oaks, “Scripture Reading and Revelation,” emphasis added; President Oaks has employed the following scriptures in support of revelatory reading: John 16:13; Joseph Smith—Translation 1 Corinthians 2:11; 2 Corinthians 3:5–6, 8; 2 Timothy 3:16; see also 2 Peter 1:21; 1 Nephi 10:19; 1 Nephi 15:3, 11; 2 Nephi 28:30//

[30] Researchers in the scholarship of teaching and learning have long recognized a variety of benefits of having students reflect and write in journals, including critical thinking, self-awareness that leads to personal growth, deeper understanding of the course material, and knowledge retention; see Anselmus Sudirman et al., “Harnessing the Power of Reflective Journal Writing in Global Contexts: A Systematic Literature Review,” International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research 20 (2021): 174–94. We are uniquely positioned as teachers of the restored gospel to add to these benefits as we invite students to record impressions they receive not just from their own introspection, but from the gift of the Holy Ghost they possess. I am entirely indebted to Rob Eaton for this point.

[31] For example, here are the instructions for my BYU undergraduate students: “Your ‘My Learning Notes’ should contain what you are learning and pondering about during each class. This is not a summary or even a detailed flow of class. Instead, listen to your own thinking and the impressions of the Spirit. Observe your ideas, questions, wonderings, and connections and write them even if they aren’t fully formed yet. Your notes should be in first person where most of your references are to ‘me,’ ‘my,’ and ‘I.’ If you receive personal insights that you would rather not share for me and our TA to review, please make sure you record those specifics somewhere else, so you don’t lose that inspiration.”

[32] In a previous gathering of religious educators, Elder Richard G. Scott defined these personal spiritual incomings as one instantiation of edification. “To me, the word edified means that the Lord will personalize our understanding of truth to meet our individual needs and as we strive for that guidance. In the branch priesthood meeting [I attended], I understood the principles that were taught by a Spirit-directed instructor. I had a witness of their truthfulness. But in addition to that, I was edified. The message taught was powerfully expanded for my personal benefit by sacred impressions communicated through the Holy Ghost.” Richard G. Scott, “Helping Others to Be Spiritually Led,” address to religious educators at a symposium on the Doctrine and Covenants and Church history, Brigham Young University, August 11, 1998, www.churchofjesuschrist.org.

[33] Russell M. Nelson, “What Is True?,” general conference talk, October 2022, www.churchofjesuschrist.org.

[34] Russell M. Nelson, “Focus on the Temple,” general conference talk, October 2022, www.churchofjesuschrist.org.

[35] Russell M. Nelson, “Come, Follow Me,” general conference talk, April 2019, www.churchofjesuschrist.org.

[36] This includes the seeker’s motives according to Elder Renlund: “We ask for what is right and good and not for what is contrary to God’s will. We do not ‘ask amiss,’ with improper motives to promote our own agenda or to fulfill our own pleasure.” Dale G. Renlund, “A Framework for Personal Revelation,” general conference talk, October 2022, www.churchofjesuschrist.org.

[37] “A second element of the framework is that we receive personal revelation only within our purview and not within the prerogative of others. . . . Doctrine, commandments, and revelations for the Church are the prerogative of the living prophet, who receives them from the Lord Jesus Christ. That is the prophet’s runway. . . . Personal revelation rightly belongs to individuals. You can receive revelation, for example, about where to live, what career path to follow, or whom to marry. Church leaders may teach doctrine and share inspired counsel, but the responsibility for these decisions rests with you. That is your revelation to receive; that is your runway.” Renlund, “Framework for Personal Revelation.”

[38] If the Holy Ghost is inspiring us, then the communications will be in harmony with the dispensational direction already provided by the Lord bolstered by the law of witnesses. Elder Renlund warns that “when we ask for revelation about something for which God has already given clear direction, we open ourselves up to misinterpreting our feelings and hearing what we want to hear,” and though “the Lord often does change, amend, or make exceptions to His revealed commandments, . . . these are made through prophetic revelation and not personal revelation. Prophetic revelation comes through God’s duly appointed prophet according to God’s wisdom and understanding.” Renlund, “Framework for Personal Revelation.” Additionally, Elder Neal A. Maxwell insightfully cautioned that “the gospel’s principles do require synchronization,” otherwise, “when pulled apart from each other or isolated, men’s interpretations and implementations of these doctrines may be wild.” Neal A. Maxwell, “‘Behold, the Enemy Is Combined’ (D&C 38:12),” Ensign, May 1993, 78.

[39] “The fourth element of the framework is to recognize what God has already revealed to you personally, while being open to further revelation from Him. . . . If God has answered a question and the circumstances have not changed, why would we expect the answer to be different? . . . If we have received personal revelation for our situation and the circumstances have not changed, God has already answered our question.” Renlund, “Framework for Personal Revelation.”

[40] Preach My Gospel: A Guide to Sharing the Gospel of Jesus Christ (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2023), chap. 5.

[41] Russell M. Nelson, “Make Time for the Lord,” general conference talk, October 2021, www.churchofjesuschrist.org.

[42] Neil L. Andersen, “The Power of Jesus Christ and Pure Doctrine,” CES religious educators conference, June 11, 2023, www.churchofjesuschrist.org.

[43] J. Reuben Clark Jr., “The Charted Course of the Church in Education,” Brigham Young University devotional, August 8, 1938, https://

[44] Gordon B. Hinckley, worldwide leadership training, February 2011, www.churchofjesuschrist.org.

[45] Joseph F. Smith, Gospel Doctrine (Deseret Book, 1986), 155.