Walk with Me

Towards a Christ-Inspired Shepherd-Leader Apprenticeship Model of Leadership Development

J. Gordon Daines III and David L. Rockwood

J. Gordon Daines III and David L. Rockwood, "Walk with Me: Towards a Christ-Inspired Shepherd-Leader Apprenticeship Model of Leadership Development," Religious Educator 25, no. 1 (2024): 131–168.

J. Gordon Daines III (gordon_daines@byu.edu) is a curator in the L. Tom Perry Special Collections at Brigham Young University.

David L. Rockwood (coachrockwood@gmail.com) is the data and assessment administrator for the Nebo School District.

Much has been written about Christ as a leader, and many have indicated the importance of becoming leaders like Christ.

Much has been written about Christ as a leader, and many have indicated the importance of becoming leaders like Christ.

Abstract: This paper reviews the literature on leadership development that focuses on Jesus Christ, then introduces a Shepherd-Leader Apprenticeship (SLA) model of leadership development. The SLA model describes how Jesus Christ develops leaders. It builds on previous scholars’ work on Christ’s leadership development approach and adds the concept of situated cognition and iterative (as opposed to linear) steps. The scriptures show how Christ used this model to develop the leadership skills of his disciples who served in a variety of capacities and roles. Christ used the SLA model with a variety of individuals who felt varying degrees of comfort with their ability to lead, and the model gave all of them the skills needed to become strong leaders. The article concludes with examples of how the SLA model can be used to help others develop leadership skills.

Keywords: leadership, teaching the gospel, Church organization

A pivotal event described in the New Testament occurred early in Jesus Christ’s ministry when he called Peter and Andrew to follow him. The scriptures state that Peter and Andrew “straightway left their nets, and followed him” (Matthew 4:18–20). This simple invitation launched a leadership training process for Peter, Andrew, and many others that would result in a blossoming of their ability to lead Christ’s fledgling church after his Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Ascension into heaven. Much has been written about Christ as a leader, and many have indicated the importance of becoming leaders like Christ. In early 1977 Spencer W. Kimball, then President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, gave an address to the Young Presidents organization in which he described Jesus Christ as the perfect leader. He outlined the qualities that made Christ such a powerful leader and said, “These same skills and qualities are important for us all if we wish to succeed as leaders in any lasting way.”[1] This statement points to an important question: “How do we develop the skills and qualities that enable us to become the type of leader that Christ would have us be?” Fortunately, Jesus Christ was not only the perfect leader; he was also the perfect trainer of leaders. This paper reviews the literature on Christ’s approach to leadership development and introduces a Shepherd-Leader Apprenticeship model of leadership development that can be used by aspiring leaders and trainers of leaders today. This model builds on the work of previous scholarship and contributes two new dimensions. It adds the concept of situated cognition and authentic activity to previously articulated leadership training models and breaks the strict linearity of those models, detailing a more iterative process than previously described. The Shepherd-Leader Apprenticeship model of leadership development has the potential to improve our ability to teach others to be Christlike leaders, a model that can be used in the classroom as well as in ecclesiastical settings.

Towards a Christ-Centered Leadership Development Model

The characteristics and attributes of good leaders have been studied in depth and from various angles and models.[2] Many of the models proposed for understanding what makes a good leader have been applied to Jesus Christ.[3] Similarly, there is a robust literature on learning theory and leadership development that tries to articulate how good leaders are developed.[4] Several scholars have attempted to apply this literature to how Jesus Christ develops leaders. We examine the models that they have developed and propose a new model that incorporates the concept of situated cognition and authentic activity and that breaks the strict linearity of these models.

Before exploring the various models of leadership development, the underlying science of learning theory, specifically context-dependent memory and situated cognition, is reviewed. Understanding learning theory prepares us to look at theories of leadership development and then to construct a model to understand how Christ develops leaders.

Learning Theory and Authentic Activity

Teaching a skill like leadership to another person runs headlong into a classic obstacle of learning: transferability, which means taking the learned skill and using it in an applied setting. Traditionally, it is assumed that a learner can acquire the needed skills in a classroom or lecture-type setting alone, and then be able to transfer those skills into the context of practice.[5] Research, however, has clearly demonstrated that this simply is not the case. Transmitting an enduring understanding to another person such that they can use that knowledge later cannot be accomplished by simply talking to them about the subject, no matter how skilled the teacher is at describing it. This is especially true when the lecture is conducted in a different environment than the one in which the learner hopes to use the skill. Walker and Dotger observe that “often novice [practitioners] acquire important knowledge in didactic classrooms yet fail to activate and use that knowledge in . . . practice.”[6] Learning that is divorced from the activity in which it is to be deployed is notoriously difficult to transfer. For learning to endure and be useful, it must be acquired in the environment or embedded in the authentic activity of practice as much as possible, intertwined with real-world experiences. The core concept is that “wisdom can’t be told,”[7] it must be experienced.

The reason classroom learning is so difficult to transfer into practice is because of an attribute of learning called context-dependent memory.[8] Knowledge and skills are inexorably tied to the contexts and environments in which they were acquired. For example, having learned how to solve a particular kind of mathematical problem, students often find it difficult to repeat the skill when at home, sitting at their kitchen table to do their homework, but then find it easier when once again in their classroom. The mathematical skill is best recalled in the same environment in which it was learned—the classroom—and difficult to transfer to a novel environment—the kitchen table. After conducting a brilliant set of experiments on this effect, Godden and Baddeley explained that “the phenomenon of context-dependent memory not only exists, but is robust enough to affect normal behaviour and performance away from the laboratory.”[9] Put simply, people are better at reproducing the learned skill when they are in the same environment in which it was learned, and encounter difficulties in transferring the skill for use in novel situations. As Brown, Collins, and Duguid explain, “the activity in which knowledge is developed and deployed . . . is not separable from . . . learning and cognition.” Rather, “learning [is] fundamentally situated” in, or linked to, the environments and activities within which it is learned.[10] This research suggests that to maximize a learner’s ability to apply the new skill in the environment of practice, the best scenario is for the learner to do the learning in the very same authentic environment of practice, or in other words, embedded within authentic activity. The next-best scenario would be to attempt to simulate the authentic environment of practice as near as possible. For example, in a study using role-playing (a simulated environment of practice) as a methodology for providing experiential learning, Sogunro reached the conclusion that “leadership competencies are learned more readily by direct experience.”[11]

Classroom-based or lecture-style learning alone is not adequate for learners to use the new skills most successfully within the authentic context of practice. However, when classroom-based or lecture-style learning is combined with practical, context-specific experience, it provides the strongest learning and transferability. Huizing underscores the importance of combining classroom learning (the why) with experiential learning (the how). He writes, “Teaching is primarily a cognitive exercise whereby disciples come to an understanding of why they should act in a particular manner. Training, on the other hand, is praxis oriented, assisting the disciple to act upon the knowledge gained through teaching. This praxis of the disciple leads to greater cognitive learning from experience and thus deeper cognitive understanding leading to further praxis.”[12] Conger agrees, writing that “it is one thing to decide in a classroom that a company should enter a new market and another to actually attempt to do it. Through a case study, a young manager can have only a limited sense of the complexities and implementation efforts required to think and act strategically. This is most effectively achieved through actual experiences.”[13] Effective leadership development involves both theory and context-specific practice embedded in authentic activity.

Models of Leadership Development, Mentorship, and Apprenticeship

As David Rockwood has written, “For the learning to endure and be useful, it must be acquired in the environment of practice, or embedded in the activity of practice, as much as possible.”[14] To produce the desired results, leadership development programs must be based in sound learning theory, providing opportunities to learn the new skills embedded within the context of application and practice (authentic activity). They must involve experiential learning. It is at the heart of effective leadership development.

Experiential leadership development goes beyond mere lecture-based training, focusing on providing followers with experiences that help them develop their leadership capabilities. This kind of experiential learning occurs best in authentic activity. By training his disciples through the medium of real-world experience, Jesus was able to provide, as Thomas puts it, “a pattern of transforming the individual in order to transform the world.”[15] Christ initially chose twelve men “to serve in leadership roles” and provided the opportunity “to interact with him in increasing degrees of intimacy and trust developed over a period of time and through observable and intentional activities.”[16] These activities provided the Apostles with experiential learning opportunities that helped them develop leadership skills in a way that was immediately usable, overcoming the learning obstacle of transferability. This was crucial for them to be able to lead the Church after Christ ascended to heaven.

This experiential learning developmental model was familiar to the Jewish people because it was used by many prophet-leaders described in the Old Testament. Keehn describes how the leadership training provided to Old Testament prophets was augmented and adapted by Jesus Christ. He writes, “Historically and biblically, leadership authority was passed onto an apprenticed leader through intentional training in the message and mission of the mentor-leader.”[17] The apprenticed leader was taught through an experiential leadership process. The spiritual leadership transition in Israel can be “seen in the examples of Moses to Joshua or Elijah to Elisha. It was their method of apprenticed leadership development that characterized Jesus’s leadership with his chosen successive leaders.”[18] Christ provided his Apostles with leadership opportunities that allowed them to move from follower to leader when the time was appropriate. The concept of experiential learning, or authentic activity, is a crucial component to the new model that we propose later in this paper.

Mentoring and apprenticeship provide potent tools for leadership development including experiential learning, and both were leveraged by Jesus Christ. Mentoring is a reciprocal and collaborative at-will relationship that most often occurs between a senior and a junior. Leadership scholars Russell and Nelson argue that mentoring is at the heart of leadership development.[19] Thomas expands this connection between mentoring and leadership development, writing that the “intent of leadership development through mentoring should consist of three specific stages of influencing others: training, educating, and giving experience, all of which can be identified in Jesus’[s] pattern of leadership development.”[20] A key component of mentoring is to provide future leaders with experiences that enable them to deepen their skills.

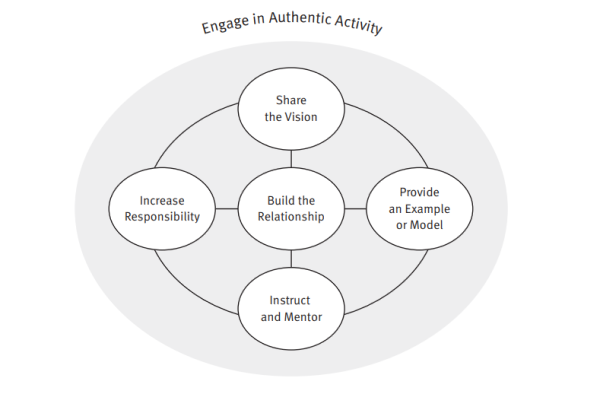

Apprenticeship is a special, formalized kind of a mentoring relationship. It is an arrangement in which someone learns an art, trade, or job under the guidance of another, normally a master. All apprenticeships are a kind of mentoring, but not all mentoring is an apprenticeship. Apprenticeship provides focused learning paired with experience. Brown, Collins, and Duguid point out that “cognitive apprenticeship methods try to enculturate students into authentic practices through activity and social interaction in a way similar to that evident—and evidently successful—in craft apprenticeship.”[21] They propose a model of apprenticeship learning that includes three steps. These steps apply to any apprenticeship scenario, including leadership. Expert teachers “promote learning, first by making explicit their tacit knowledge or by modeling their strategies for the students in authentic activity. Then the teachers and colleagues support students’ attempt at doing the task. And finally they empower the students to continue independently.”[22] Applied to the skills of leadership, the development of these skills involves modeling a task, helping the learner do the task, and then letting the learner do the task on their own, all done within the authentic environment of that skill—a methodology that Christ excelled at (see figure 1 below). The apprenticeship model of Brown et al. can be summarized into the following steps:

- The master teacher models the skills within the context of authentic activity: “Here, watch me do it.”

- The master teacher supports the students’ attempts to replicate the skills within authentic activity: “Now you try it. I’ll help.”

- The master teacher empowers the students as they continue independently: “Now you are ready to do it without me watching over your shoulder.”

The general model of mentoring and the specific model of apprenticeship are at the heart of Christ’s approach to leadership development. The next section of this article examines how the academic literature describes the leadership development methodologies used by Jesus Christ.

Earlier Christ-Inspired Models of Leadership Development

There are several models that attempt to describe Jesus Christ’s leadership development approach. Many of these models share common themes and principles, while also offering unique contributions (see table 1). All of them present a linear, step- or stage-based model in which Christ moves through the steps in a prescribed order.

Keehn outlines a four-step methodology, drawing heavily from Leader-Member Exchange theory, to describe how Christ helped his disciples develop into effective leaders. In it, the first step taken by the master-leader is to select apprentice-leaders. Applied to Christ, this step is demonstrated when he called his disciples to follow him. Kheen is the only scholar reviewed who included this step. For Crowther on the other hand, Christ’s first step is to help his disciples develop internal character traits like love, integrity, forgiveness, and perseverance, and to help them overcome selfishness and greed.[23] Crowther describes this stage as “preparation,” “pre-leadership,” and “soul development.”[24]

Keehn’s second step is to follow Christ, who provides for his students an example or model for how they are to lead. Wood agrees with Keehn, identifying example-giving as Christ’s first step of leadership development. “Jesus not only taught servant leadership,” Wood writes, “but modeled it.”[25] He points out that the “supreme demonstration of this took place just before his crucifixion when Jesus, alone in an intimate setting with his disciples, abruptly left the dinner table, wrapped a long towel around his waist, and proceeded to wash the disciples’ feet.”[26] Wood explains that this episode was more than an act of service. “The footwashing experience, understood only as an expression of service, misses half the point. As much as this was an act of service, it was also an act of leadership.”[27] Wood highlights the fact that Jesus not only exemplified servant leadership but that he was also, through word and deed, teaching his Apostles how to lead. The foot washing episode was an opportunity for Jesus to model “something he clearly wanted the disciples to grasp.”[28]

Keehn’s third step has significant overlap with the work of other scholars. He suggests that Christ provides to his apprentice-leader direct instruction, education, and training on how to lead. Wood includes this as the second step, calling it the step of teaching by “precept.”[29] Russell and Nelson include this as their first and second steps. We also note that Brown et al. list this as their first step in the nonscriptural apprenticeship model.

The fourth and final step in Keehn’s model also has significant agreement among other scholars, aligning with Crowther’s second step, Russell and Nelson’s third step, and Brown et al.’s second step. All these models identify the master-leader (Christ) giving the students increased responsibility, authority, and real-world experience—often under the supervision of the master-leader. Keehn describes this, saying, “The apprentice . . . must be given opportunities to act in the place of the master-leader.”[30] The third and final step in Brown et al.’s model is for the learner to continue their real-world application in a less supervised independent practice of the skills.

Wood’s third and final step posits that Christ shares his leadership vision with his disciples to encourage, motivate, and persuade them to work hard and align their practice with his own. Wood calls this teaching by “persuasion.”[31] And Crowther’s third and final step is for the master-leader to develop a leadership legacy, defined as “the leader must develop other leaders who can replace or improve upon her/

In surveying the various proposed models of how Christ trained leaders, Thomas identifies relationship building as the unspoken preparatory step to all of the proposed models. He explains that, for Christ, successful leader development “depends on the personal shaping of others found in close mentoring relationships.”[33] He identified relationship building as the “personal preparatory work by the mentor before effective mentorship takes place,”[34] because “for Jesus, discipleship was a relationship before it was a task, it was a who before a what.”[35]

A key component of relationship building, especially in a leadership context, is creating and deepening a sense of trust. Nanus succinctly states that “all leaders require trust as a basis for their legitimacy.”[36] Much has been written about trust in the context of leadership.[37] Mishra provides a compelling definition of trust, stating that “trust is one party’s willingness to be vulnerable to another,”[38] highlighting that a key precondition to developing trust is vulnerability. Hoy and Tschannen-Moran developed a comprehensive model for how leaders effectively build a sense of trust, grouping five key elements into a single approach.[39] As the leader demonstrates proficiency in the five elements, followers develop a deeper sense of trust in the leader. The critical elements are competence (the degree of confidence one has in the skills and abilities of the leader-teacher), honesty (the degree to which one can rely on the word or promise of the leader-teacher), openness (the open sharing of information, influence, and control), reliability (the teacher-leader’s consistency, predictability, and dependability), and finally benevolence (the confidence that one’s well-being will be protected by the teacher-leader). These five elements, when found together in the character and actions of a teacher-leader, serve to strengthen the trust felt by the learner-follower. Though vulnerable to the master-teacher, learner-followers trust that he or she is accomplished in the skill they are learning and proficient in teaching that skill, honest in word and deed, open in the sharing of information, dependable, and finally genuine in holding the best interests of the learners at heart.

| Thomas | Keehn | Crowther | Wood | Russell and Nelson | Brown et al. | |

| Develop a deep personal relationship | Step 0 (a preparatory step to all models) | |||||

| Select students | Step 1 | |||||

| Develop internal traits of character | Step 1 | |||||

| Be an example or role model | Step 2 | Step 1 | Step 1, plus below | |||

| Provide direct instruction (teach, train, educate) | Step 3 | Step 2 | Steps 1 and 2 | Step 1, plus above | ||

| Increase responsibility, authority, experience | Step 4 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 2 | ||

| Engage in independent practice | Step 3 | |||||

| Persuade, motivate, share vision | Step 3 | |||||

| Leave a legacy of leadership | Step 3 |

Table 1. Summary of Christ-inspired models of leadership development derived from analyzing the biblical record, alongside Brown et al.’s general apprenticeship model.

Shepherd-Leader Apprenticeship Model

There is substantial overlap of key components among these Christ-centric leadership development models proposed by earlier scholars, and each one contributes some unique perspective. Individually, however, each one is incomplete. We propose a new model for describing how Christ helps develop his disciples into leaders, a model that builds on the work of earlier scholars, synthesizing many of their strengths while also contributing new elements. Our newly articulated model breaks from their earlier work in two ways. First, it does not present leadership development as a set of universal and linear steps or stages but decouples Christ’s leadership development from strict linearity. This nonlinear approach to leadership development provides for an iterative and flexible model, allowing Christ to move between the elements as they are needed by his leader-apprentices. Below, we lay out the evidence from the scriptural record that Christ does indeed take a flexible and iterative approach to leadership development. He uses all the components of our proposed model as he trains leaders, but he does not necessarily use them in the same order with every learner. He tailors his leadership development to the needs of the individual being taught. The second main contribution of this new model is that it adds the concept of situated cognition, embedding the learning process within the context of authentic activity. This important component is supported by research in learning as well as evidenced in the scriptural record. Christ did not rely solely on lectures or sermons delivered in sterile classrooms or churches to train his leader-apprentices but consistently immersed his leadership training in the authentic context of actually doing the work.

We call our proposal the Shepherd-Leader Apprenticeship (SLA) model of leadership development. Below we describe how Christ uses this model throughout the scriptural record, spanning millennia and continents. He used it in the eras of the Old and New Testaments, the Book of Mormon, and the Doctrine and Covenants. Though the order is not fixed, the SLA model contains the following elements:

- Build the Relationship. Christ often begins, as Thomas asserts, with relationship building, so we place this component as a central feature of our proposed model. Relationship building can occur in many ways, but it always involves Jesus Christ showing that he trusts and loves the apprentice-leader and that the apprentice-leader can trust him in return. Christ builds his relationships with us through the gift of the Holy Ghost. This unique gift provides insight and knowledge to apprentice-leaders. It is also a support that helps apprentice-leaders know that they are on the right track in their efforts to become leaders. Support is often mentioned as a key component of secular leadership development.

- Share the Vision. Christ helps the individual catch and share his vision (of saving humankind, as declared in Moses 1:39). He then helps the individual understand what he or she can do to aid in this work (expanding personal vision). This component was included by Wood in his model, and we see Christ utilizing it in various ways as he develops disciples into leaders.

- Instruct and Mentor. In this component we have combined elements such as teaching, educating, and training from scholars such as Russell and Nelson, Keehn, Huizing, and Wood, as well as a guided mentorship/

apprenticeship from Brown et al. Christ mentors the individual through an apprenticeship model. Christ teaches leaders the skills necessary to successfully bring about his vision. He gives those he has chosen personalized instruction about the plan of salvation and the work that he intends for them to do. - Provide an Example or Model. Christ provides leaders with an example of how to do the work assigned to them. Leaders in training can “observe” him (either in person, in vision, or through the scriptures) leading others, and he expects them to participate in the same way. Doing so embeds the learning moments within the experience of doing the work, making the knowledge and skills learned more transferable and usable in the future. We see this element in the models of Brown et al. and of Wood.

- Increase Responsibility. Christ allows the individual to take a more active leadership role. He allows the leader in training to take on greater responsibility, learning from their experiences, reflecting on successes and failures, and iteratively improving their craft, all situated within the real-world context of practice. The increased responsibility often slightly outpaces their current skill level, requiring the leader apprentice to stretch and grow. We see this element in the models proposed by Russell and Nelson, Keehn, Brown et al., and Crowther. Secular leadership development theory talks about challenging prospective leaders. The SLA model allows this to happen by providing apprentice-leaders with increased responsibility.

- Engage in Authentic Activity. Drawn from the broader work in situated cognition generally (see Brown et al.), all the previous five components are embedded within the larger circle of authentic activity. It is crucial to note that Christ-led leadership development occurs in the authentic context of doing the work—it is real-world learning and action. Christ often asks his chosen leaders to “return and report” on their activities. This allows for personalized mentorship and assessment of the learning. It also activates the transferability of the skill, allowing the learner to use the new skills in independent practice with greater confidence. Authentic activity involves both learning by doing and being taught in a classroom setting with assignments that then allow the application of what was learned in the classroom.

Figure 1 illustrates how these components work together. The entire SLA model is contained within the Engage in Authentic Activity of real-world practice. Within the real-world experience of authentic activity, we find Build the Relationship as the central feature. Arrayed around relationship building are the other four elements of Share the Vision, Provide an Example or Model, Instruct and Mentor, and Increase Responsibility. These components are iterative in nature. Christ can (and does) start in different places with each individual learner and moves through the other components as the learner needs them, the contributions of each component folding into and strengthening the learner’s development in the other components.

Figure 1.The Shepherd-Leader Apprenticeship model of leadership development.

Figure 1.The Shepherd-Leader Apprenticeship model of leadership development.

The rest of this article examines how this model is seen in the Old Testament, New Testament, Book of Mormon, and latter-day eras. After examining these illustrative examples, the paper then turns to how leaders can apply this leadership development model in families, the Church, and other contexts. It is important to note here that many of the scriptural passages used as examples of how Jesus Christ utilizes the SLA model of leadership development could be used as illustrations of multiple components. For example, the Lord answering Nephi’s prayers shows how Jesus Christ builds relationships and provides direct instruction and shares vision. For simplicity in the analysis found below, in most cases we use each scriptural passage to illustrate one component of the SLA model rather than trying to explicate every single component of the model illustrated by the passage.

Old Testament Era: Enoch

Acting as Jehovah in the Old Testament era¸ Jesus Christ utilized the Shepherd-Leader Apprenticeship model of leadership development with many leaders. Here we use Enoch as an illustrative example.[40] Through the lens of the SLA model, we see how Christ prepared and developed Enoch into an effective leader.

The Old Testament proper contains little information about Enoch’s preparation for leadership (Genesis 5:18–24). However, the book of Moses in the Pearl of Great Price contains a two-chapter narrative of Enoch’s call, preparation, and ministry (see table 2). The premortal Jesus Christ established a direct relationship with Enoch when he said, “Enoch, my son” (Moses 6:27). Here Christ began Enoch’s direct leadership development using the central component of relationship building, calling him by his name and addressing him in relational terms, “my son.” This aligns directly with the SLA model, which has relationship building at its core. From there, Christ moved seamlessly into increasing responsibility by issuing the imperative “Prophesy unto this people, and say unto them—repent” (Moses 6:27), giving Enoch his primary responsibility. Christ then began direct instruction on what Enoch was to say in his ministry (Moses 6:27–30). Doing so represents Christ moving from the initial steps of relationship building and increasing responsibility into the instructing/

Enoch’s first reaction was to feel incapable (Moses 6:31). Feeling insecure like Enoch did, though not a step or component for an apprentice-leader in leadership development, is a very common response. Recognizing Enoch’s feelings, Christ intervened to assuage his insecurities by moving to another element of the SLA model: sharing the vision. He assured Enoch that he would be made capable under the apprenticeship and power of God (Moses 6:32–34). “Open thy mouth, and it shall be filled, and I will give thee utterance” (Moses 6:32), and “All thy words will I justify . . . therefore walk with me” (Moses 6:34). Here Christ wove together multiple components into one. Christ’s words gave Enoch confidence by sharing part of God’s vision for the powerful leader Enoch would grow to become. They also provided for Enoch his first glimpse of Christ as his role model and exemplar for how to lift and inspire others as a leader. This element of seeing Christ as a role model is highlighted by the phrase “walk with me” (emphasis added). Simultaneously, Christ’s encouragement provided another building block in developing the relationship of trust between the two of them. What followed was additional work in sharing the vision, in which Christ literally gave Enoch a revelatory vision, allowing him to see “the spirits that God had created . . . which were not visible to the natural eye” (Moses 6:36). Next, Enoch entered the authentic activity of his prophetic work and ministry, going “forth in the land among the people” (Moses 6:37). As Enoch grew into his leadership role, Christ increased the responsibility given to him. As he moved among the people, we, the readers, are assured that he “walked with God,” (Moses 6:39) again highlighting that Christ was alongside Enoch, providing instruction and mentorship as he engaged in the real-world work.

At this point, Christ had used all the components of the SLA model, and yet Enoch was still growing and developing. Consequently, Christ continued to move through the SLA components for the remainder of Enoch’s ministry. In chapter seven of Moses, we read Christ’s direct fulfillment of his promises to Enoch,[41] which served to further build their relationship of trust. Christ is described as having given great power to Enoch (Moses 7:13), a nod to his increasing responsibility. Also in chapter seven we find the description of an immense vision given to Enoch (Moses 7:24–67), in which, famously, Enoch saw Christ weep over the suffering of his children on the earth and their hatred toward each other. Also in this vision, Enoch was shown the life and mortal ministry of Jesus Christ (Moses 7:47), providing for him the clearest illustration of Christ as an exemplar and role model. Throughout this vision, Christ continued to build their relationship, showing his own vulnerability, and providing encouragement and comfort to Enoch during the prophet’s moments of sorrow (Moses 7:44–63). The prophetic vision concluded with Christ showing to Enoch the final salvation of the righteous, providing the most powerful example in the entire narrative of sharing the vision. As a result, Enoch “received a fulness of joy” (Moses 7:67). The final result of Christ’s mentoring of Enoch and of Enoch’s leadership is that “all his people walked with God” and “God received [them] up into his own bosom” (Moses 7:69).

| Engage in Authentic Activity | The Lord trained Enoch, using the behaviors listed below, in the authentic context of Enoch going out and actually doing the work of the ministry. 6:37 Enoch went “forth among the people.” |

| Build the Relationship | 6:27 “Enoch, my son.” 6:34 The Lord makes specific promises to Enoch. 7:13 The Lord fulfills the promises made to Enoch in 6:34, building trust. 7:28–37 The Lord allows Enoch to see him weep, showing vulnerability and trust. 7:41 Enoch understands the Lord’s heart and is also moved to weep, showing vulnerability and trust. 7:44–63 When Enoch feels depressed and insecure, the Lord builds him up. |

| Share the Vision | 6:32–34 When Enoch feels incapable, the Lord inspires him with confidence. 6:35–36 The Lord allows Enoch “to see” beyond the veil, literally sharing greater vision. 7:24–50 The Lord gives Enoch an expansive prophetic vision of the world. 7:51–64 The Lord gives Enoch a vision of the future salvation of humankind. 7:65 The Lord gives Enoch a vision of the life of Christ. |

| Provide an Example or Mode | 6:32–34 The Lord inspires confidence within Enoch during his moments of self-doubt, modeling for Enoch how to do likewise for others. 6:34 The Lord invites Enoch to “walk with me.” 6:39 Enoch is said to have “walked with God.” 7:28–37 The Lord allows Enoch to see him weep, providing an example for him of the compassion he must also develop. 7:41 Enoch understands the Lord’s heart and is also moved to weep, following his example. 7:44–63 When Enoch feels depressed and incapable, the Lord inspires him with more confidence, providing an example for how he too should uplift others. 7:47 The Lord shows Enoch the life of Christ, providing a visual role model for him to follow in his own ministry. |

| Instruct and Mentor | 6:28–30 The Lord gives Enoch direct instruction on what to teach in his ministry |

| Increase Responsibility | 6:27 The Lord gives Enoch the responsibility to “prophesy unto this people.” 6:37 Enoch goes forth among the people to preach. 7:13 “So great was the power . . . which God had given to Enoch.” |

Table 2. Enoch’s leadership journey aligned with the elements of the SLA model. (All references are from the book of Moses in the Pearl of Great Price.)

New Testament Era: Peter

Christ used the same methodology (the SLA model of leadership development) to train his Apostles in the New Testament to become leaders in the Church as he used with Enoch. One key contextual difference is that Christ was physically present for the training. To illustrate how Christ followed the SLA model to prepare his chosen Apostles for leadership, our analysis is centered on the leadership development of Peter. The narrative in the New Testament is divided across the four Gospels and Acts. There is overlap between them, however there is no absolutely harmonized chronology of the events. Therefore in the analysis below, we organized the illustrative events under the headings of the elements of the SLA model rather than in a chronological order (see table 3).

Throughout the New Testament narrative there are multiple occasions in which Jesus Christ directly engaged in relationship building with Peter. In John 1:42, Christ changed his disciple’s name from Simon to Cephas, or Peter, a sign of a special relationship between them.[42] Later, Christ ordained Peter and the other Apostles “that they should be with him” (Mark 3:14, emphasis added). In this passage, Christ appeared to be doing more for them than simply expecting them to learn from him as students. He was also inviting them to enter into a close relationship with him. In one particularly personal moment, Christ entered Peter’s home to find his mother-in-law sick in bed. Christ’s response was to heal her from her ailment (Matthew 8:14–15), demonstrating the concern that Christ had for Peter and his family. On Christ’s last night with the disciples, he voiced a heartfelt prayer for Peter and the other Apostles. By allowing them to hear his prayer for them, Christ showed them the depth of the love he has for them. All these actions, and others, allowed a deep personal relationship of love and trust to develop between Jesus and Peter. This deep personal relationship acted as an effective medium through which to transmit the other components of the SLA model of leadership development.

Within the context of this deep personal relationship, Christ explicitly shared his vision for the work in which he was engaged, and to which he was recruiting Peter. Christ’s first words to Simon Peter and his colleagues were, “Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men” (Matthew 4:18–21), thus introducing the work Peter would be doing. Christ publicly announced that his purpose was to “save that which was lost” (Luke 19:10), “to preach . . . to heal . . . to set at liberty” (Luke 4:16–21), and ultimately to save the world (John 3:16–17). These declarations undoubtedly formed in Peter’s mind the core understanding of Christ’s vision for the work. In another moment, Christ taught his disciples that the core principle of his entire gospel is love (John 13:34–35), an important vision-setting lesson for the future leadership of the Church. In Matthew 16:13–19, Jesus explicitly told Peter that he would become a central leader in the Church, using some wordplay with his name when he said, “Thou are Peter [meaning stone or rock], and upon this rock I will build my church,” implying that Peter himself was the rock upon which the Church would be built. A final example of Christ sharing his vision with Peter to help him understand the great commission to which he had been called was when, before his final ascension into heaven, he instructed them to “Go ye therefore and teach all nations” (Matthew 28:16–20).

Openly holding his own actions up as a model, Christ used the power of his example to prepare Peter for his developing leadership role. Interestingly, Christ also modeled how he learned through example, describing to his apprentice leaders that he himself had learned by watching the example of his Father (John 5:19). Christ explained to the disciples that his learning expectations for them were to observe his example and seek to follow it (Matthew 4:19; 16:24–27). Following the powerful foot-washing experience, Christ explained to Peter, “I have given you an example, that ye should do as I have done” (John 13:4–16). Another example of Christ providing himself as a role model to be observed and imitated is seen in the raising of the daughter of Jairus from the dead. He called Peter, James, and John to accompany him, and put all others out of the house (Mark 5:22–43). In this private moment, these three apprentice leaders were able to intimately watch how Christ compassionately interacted with Jairus’s family, and humbly exercised his power to raise the girl from the dead. Keehn explains that Jesus was following the common rabbinical “practice of serving under and literally following around the master-leader to learn by observation and servanthood. Upon examining the Synoptic Gospels, a reader will recognize the call to discipleship was rooted in the Jewish practice of literally following a rabbi around for a length of time to become like the religious master in belief, attitude, and actions.”[43]

There are many examples of Christ taking time to give Peter direct instruction on his leadership role. Several of these are when he explained to Peter that he was to lead by following Christ’s example, as in the stories above. All three synoptic Gospels include an account of Christ teaching Peter specifically about servant leadership (Matthew 20:25–27; Mark 10:42–44; Luke 22:25–27). Thomas explains that “soon after the mission of Mark 6 was completed, additional mentoring and reflection took place to prepare the disciples for an even greater mission.”[44] A final example of direct instruction is when, after Peter’s thrice-repeated denial and Christ’s Resurrection, the Lord instructed him to “feed my sheep.”[45]

As Peter and the other apprentice leaders learned how to lead through Christ’s direct instruction and modeling, embrace his vision for the work, and develop a deeper relationship with him, all within the context of authentic activity, Christ turned over to them more and more authority and responsibility. It began with a promise: “I will make you fishers of men” (Matthew 4:18–21). Soon, Christ ordained Peter with priesthood power “to preach,” “to heal sicknesses, and to cast out devils” (Mark 3:14–16) and sent Peter and the other Apostles on a missionary journey (Mark 6:7). The responsibility given to Peter increased throughout his leadership development, as Jesus transitioned more and more authority to his Apostles. In the closing events of Christ’s physical presence on earth, he explained to Peter, “My Father hath sent me, even so send I you” (John 20:21), ending with his great commission to Peter and the other disciples to “Go ye therefore and teach all nations” (Matthew 28:16–20). From there, the responsibility to lead the Church was fully transitioned to Peter, and this transition is further described in the book of Acts.

Table 3 summarizes some of the New Testament passages that exemplify ways in which Christ utilized the elements of the Shepherd-Leadership Apprenticeship model to train and develop Peter’s leadership skills.

| Engage in Authentic Activity | Christ trained Peter for leadership in the real-world context of actually doing the work. Peter saw Christ’s example by accompanying him in the work. Christ gave Peter real assignments to go out and actually do. |

| Build the Relationship | John 1:42 Jesus renames Simon to Cephas or Peter, a symbol of a special relationship (as with Abram-Abraham, Jacob-Israel, and others). Matthew 8:14–15 Jesus heals Peter’s mother-in-law. Mark 3:14 Jesus ordains Peter and the other Apostles “that they should be with him” (emphasis added). John 17 Jesus prays for Peter and the other Apostles, and allows them to hear the prayer. |

| Share the Vision | Matthew 4:18–21 “Follow me and I will make you fishers of men.” Luke 4:16–21 Christ quotes Isaiah like a personal vision statement: “To preach . . . to heal . . . to set at liberty. . . .” Luke 19:10 “To save that which was lost.” John 3:16–17 To save the world. John 10:10 “I am come that they might have life.” Matthew 16:13–19 “Thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church.” John 13:34–35; Matthew 22:37–40 The two great commandments are about love. Matthew 28:16–20; Mark 16:15–18 Christ extends his great commission to Peter and the other Apostles to “Go ye therefore and teach all nations.” |

| Provide an Example or Model | John 5:19 Christ himself follows the example set by the Father. Mark 5:22–43 When Christ goes to raise the daughter of Jairus from the dead, “he suffered no man to follow him, save Peter, and James, and John.” Matthew 4:19 “Follow me.” Matthew 16:24–27 “Take up [your] cross, and follow me.” John 13:4–16 Christ washes Peter’s feet, saying, “I have given you an example.” |

| Instruct and Mentor | Matthew 20:25–27; Mark 10:42–44; Luke 22:25–27 Direct instruction to Peter on servant leadership. John 13:15–16 “I have given you an example, that ye should do as I have done.” Mark 4:10–20, 33; 6:30; 7:17–23 Jesus teaches Peter and the Apostles in private moments. Mark 6:8–11 Jesus gives direct instruction on how to behave during Peter’s mission. Mark 16; Matthew 28 Upon the disciples’ return from a previous missionary journey, “additional mentoring and reflection took place to prepare the disciples for an even greater mission.”[46] John 13:34–35; Matthew 22:37–40 The two great commandments are about love. John 21:1–19 Peter takes Apostles fishing, and the resurrected Christ invites him to “feed my sheep.” |

| Increase Responsibility | Matthew 4:18–21 “Follow me and I will make you fishers of men.” Mark 6:7 Christ sends Peter and his disciples, without him, into the mission field two by two. Mark 3:14–15 Jesus ordains Peter and the twelve “to preach,” giving them “power to heal sicknesses, and to cast out devils.” Mark 16; Matthew 28 Upon the disciples’ return from a previous missionary journey, “additional mentoring and reflection took place to prepare the disciples for an even greater mission.”[47] Matthew 28:16–20; Mark 16:15–18 Christ extends his great commission to Peter and the other Apostles to “Go ye therefore and teach all nations. . . .” John 20:21 “My Father hath sent me, even so send I you.” |

Table 3. Peter’s leadership journey aligned with the elements of the SLA model. Though many of these events happened with and to other Apostles as well, this analysis is focused on Peter.

Book of Mormon Era: Nephi

Like the Old Testament and the New Testament, the Book of Mormon is full of valuable leadership lessons.[48] Christ utilized the SLA model of leadership development to train numerous leaders in the Book of Mormon.[49] The SLA model is seen clearly in the experiences of Nephi, the son of Lehi (hereafter Nephi). The first step of the model is the development of a deep personal relationship with Jesus Christ. The initial development of this relationship is described in 1 Nephi 2. Nephi had listened to his father Lehi preach about the coming of the Messiah, the destruction of Jerusalem, and many other “marvelous things” (1 Nephi 1:18). Nephi wanted to understand what his father was teaching, and he wanted to know if these things were true. He desired “to know of the mysteries of God” and “did cry unto the Lord.” Nephi’s prayer was answered, and Jesus Christ “did soften my heart that I did believe all the words which had been spoken by my father” (1 Nephi 2:16). Through this experience Nephi learned that Jesus Christ hears and answers prayers and that he desires to have a personal relationship with his followers. The rest of Nephi’s story in the Book of Mormon documents the ongoing development and strengthening of this relationship. Nephi responded with faith when he returned for the brass plates with his brothers (1 Nephi 3:7), allowed himself to be led by the Spirit during his encounter with Laban (1 Nephi 4), and obediently began building a boat (1 Nephi 18). In every case Nephi demonstrated that he could be trusted and that he would do Christ’s will. In return, Christ answered Nephi’s prayers (1 Nephi 2:16; 7:17–18), provided him with guidance and direction (1 Nephi 4:6; 18:2–3), and physically protected him (1 Nephi 18). Nephi’s relationship with Jesus Christ was at the heart of his leadership development journey.

As a result of Nephi’s relationship with Jesus Christ, he was privileged to receive a deeper understanding or vision of Heavenly Father’s plan of happiness. On several occasions Jesus Christ imparted with Nephi the vision of saving mankind that he shares with Heavenly Father (1 Nephi 14:7, 14). One of the earliest examples was during the retrieval of the brass plates. The Spirit taught Nephi that “inasmuch as thy seed shall keep my commandments, they shall prosper in the land of promise. Yea, and I also thought that they could not keep the commandments of the Lord according to the law of Moses, save they should have the law. And I also knew that the law was engraven upon the plates of brass” (1 Nephi 4:14–16). Nephi learned that Jesus Christ wanted the people to prosper in the land and came to understand that the only way that they could prosper in the land was to keep the commandments given to them. They needed the brass plates in order to know what the commandments were. Nephi’s experience relative to Lehi’s vision of the tree of life is another example of how Jesus Christ shared the vision with Nephi. Nephi prayed to understand the vision of the tree of life that had been given to Lehi. As a result of his desire to understand, he was shown a panoramic vision. Through this vision he came to understand Jesus Christ’s personal mission and the depth of Heavenly Father’s love for his children. (1 Nephi 11–14).

As a result of Nephi’s willingness to believe the teachings of his father and his willingness to keep the commandments of Jesus Christ, Nephi was given increased responsibility. Christ promised Nephi a land of promise because of his faith and told Nephi that he would make him a ruler and a teacher over his brethren (1 Nephi 2:19–22). Nephi was later given responsibility to teach his brothers about the importance of prayer (1 Nephi 15:8–11), commanded to build a ship (1 Nephi 17:8–10), told to make plates of ore to record the things of his ministry (1 Nephi 19:1–15), and given responsibility to teach his family what he had learned through his many spiritual experiences (1 Nephi 19:22). This pattern of receiving increased responsibility as Nephi was obedient to the commandments was repeated throughout the rest of his life with Jesus Christ supplying him what it was that he most needed in the moment of that need.

As Nephi came to understand what motivates Heavenly Father and Jesus Christ, he was privileged to learn from their examples. Nephi’s learning occurred in two ways: (1) He learned about Jesus Christ from the brass plates and studied how he (as Jehovah) led in the Old Testament. (2) Through Nephi’s own visions, he was able to “see” Heavenly Father’s and Christ’s leadership in person. They also allowed Nephi to come to understand how love motivates everything that Heavenly Father does. Nephi witnessed Christ lead and train leaders in the Americas (1 Nephi 12:6–11), and he saw Christ’s Galilean ministry in vision and learned how Christ interacted with and led his disciples (1 Nephi 11:27–34). Nephi was able to model his own leadership after their examples. Nephi had another model in his father Lehi, who was also tutored by Jesus Christ using the SLA model of leadership development.

Jesus Christ took numerous opportunities to directly teach Nephi spiritual and temporal lessons. When Nephi prayed to learn if his father’s teachings were true, Christ answered that they were (1 Nephi 2:16–17). Nephi then taught what he had learned to his brother Sam. Nephi received numerous visions (as previously mentioned) in which he was taught, among other things, the plan of salvation and the depth of Heavenly Father’s love for his people. He was taught how the Liahona functioned and came to understand that its purpose was to “give us understanding concerning the ways of the Lord” (1 Nephi 16:28–30). Nephi was personally mentored so that he could accomplish the work that Heavenly Father and Jesus Christ had for him.

It is important to note that Nephi’s experiences with the Shepherd-Leader Apprenticeship model of leadership development are not linear. Jesus Christ taught leadership to Nephi using each component of the model as Nephi needed it. For example, as Nephi was gaining a deeper vision of Heavenly Father’s purpose, he was also shown how Christ led and loved people. He was then given the responsibility to share this learning with his family. The SLA model of leadership development is an iterative process that occurred as Nephi lived his life. It unfolded as he engaged in the activities necessary to successfully help his family and people come unto Christ.

Table 4 summarizes some of the Book of Mormon passages that illustrate how Jesus Christ utilized the elements of the Shepherd-Leadership Apprenticeship model to teach Nephi leadership skills.

| Engage in Authentic Activity | Nephi’s experiences with leadership occur as he lives his life and engages in the activities necessary to successfully help his family and people. |

| Build the Relationship | 1 Nephi 2:16 Nephi prays about what Lehi had taught, and the Lord softens his heart so that “I did believe all the words which had been spoken by my father.” 1 Nephi 3:7 Nephi exercises faith in the Lord and responds positively to his father. 1 Nephi 4:6 Nephi is led by the Spirit. 1 Nephi 4:18 Nephi obeys the voice of the Spirit. 1 Nephi 5:20 Nephi keeps the commandments. 1 Nephi 7:17–18 Nephi prays for strength to break his bonds. and the Lord gives him strength. 1 Nephi 17:2–3, 12–14 The Lord blesses Lehi and his family during their travels; Nephi recognizes that the Lord is fulfilling his promises. 1 Nephi 18:10–22 Nephi’s brothers bind him. Nephi prays for the Lord to soften their hearts. Nephi is released and prays for the storm to stop. The storm stops; Nephi’s prayer is answered. |

| Share the Vision | 1 Nephi 4:11–15 Nephi is taught why it is so important for him to obtain the brass plates. 1 Nephi 11–14 Nephi is given a vision in which he learns of the plan of salvation and comes to understand the importance of Jesus Christ to that plan. 1 Nephi 19:7–17 Nephi shares what he has learned of the plan of salvation. 2 Nephi 26:9 Nephi sees that his people will be healed by Christ. 2 Nephi 27–32 Nephi is given a vision of the future, and his understanding of the central role of Jesus Christ is strengthened. |

| Provide an Example or Model | 1 Nephi 11:27–34 Nephi sees Christ’s Galilean ministry in vision and learns how Christ led his disciples. 1 Nephi 12:6–11 Nephi witnesses Christ lead and train leaders in the Americas in vision. 1 Nephi 13:33–37 Nephi is taught that Christ will be merciful to the Gentiles and sees in vision how this happens. 1 Nephi 17:48–55 Nephi is commanded to tell his brothers not to touch him or they will be smitten. Nephi is then commanded to stretch forth his hand, and his brothers are shocked. |

| Instruct and Mentor | 1 Nephi 2:17 Nephi shares with the Sam the things “the Lord had manifested unto me by his Holy Spirit.” 1 Nephi 4:11–15 Nephi is taught why his people need the brass plates. 1 Nephi 11:11–36 Nephi desires to know the interpretation of Lehi’s vision and is taught by the Spirit of the Lord. 1 Nephi 16:28–30 Nephi learns how the Liahona functions. The writings on the Liahona “give us understanding concerning the ways of the Lord.” 1 Nephi 18:2–3 The Lord teaches Nephi how to build a boat and other “great things.” 2 Nephi 4:25 “And mine eyes have beheld great things, yea, even too great for man.” |

| Increase Responsibility | 1 Nephi 2:19–22 The Lord promises that Nephi will inherit a land of promise because of his faith and that he will become a ruler and a teacher over his brothers. 1 Nephi 7:8–15 Nephi reprimands his brothers for their lack of faith. 1 Nephi 9:3 Nephi is commanded to keep a separate set of plates regarding his ministry. 1 Nephi 15:8–11 Nephi teaches his brothers about the importance of inquiring of the Lord. 1 Nephi 17:8–10 Nephi is commanded to build a ship. 1 Nephi 19:1–15 Nephi makes plates of ore at the command of the Lord; the purpose of these plates is to record the things of Nephi’s ministry. 1 Nephi 19:22 Nephi teaches his family. 1 Nephi 22 Nephi explains the Isaiah chapters to his brothers. 2 Nephi 4:14 Nephi preaches to his brothers. 2 Nephi 5:19 Nephi notes that the word of the Lord has been fulfilled in that he was his brothers’ teacher and ruler. 2 Nephi 25:28 Nephi has spoken plainly to his people so that they cannot misunderstand. |

Table 4. Nephi’s leadership journey aligned with the elements of the SLA model.

Latter-Day Era: Joseph Smith

The Servant-Leader Apprenticeship model of leadership development is used by Jesus Christ in our dispensation as well. It is clearly seen in the life of Joseph Smith. Joseph Smith’s leadership development experiences are documented in Joseph Smith—History and the Doctrine and Covenants (see table 5). Joseph’s experiences fit the SLA model of leadership development utilized by Jesus Christ. Joseph desired a relationship with God and Jesus Christ, and that relationship was reciprocated. Joseph’s leadership journey began with his efforts to build a relationship with God. He studied the Bible and acted on what he learned. In his history, Joseph Smith described coming across a verse of scripture that inspired him to approach God. Joseph Smith—History 1:12–13 describes the impact of James 1:5 on young Joseph. He recounted how this scriptural passage entered into his heart and how he reflected constantly on it. Joseph eventually “came to the conclusion that I must either remain in darkness and confusion, or else I must do as James directs, that is, ask of God. I at length came to the determination to ‘ask of God,’ concluding that if he gave wisdom to them that lacked wisdom, and would give liberally, and not upbraid, I might venture.” Joseph retired to a grove of trees near his home and his prayer was answered. One of the stunning revelations coming from Joseph’s experience is that, like with Moses, Christ and Heavenly Father knew his name. Joseph was individually known to them, and this became the cornerstone of Joseph’s relationship with deity. Heavenly Father and Christ conversed with Joseph and promised him further instruction. Another powerful example of Christ’s efforts to build a relationship with Joseph occurred in Liberty Jail. Christ comforted and taught Joseph using himself as an example of long-suffering (Doctrine and Covenants 121–22). Joseph’s deeply personal relationship with Heavenly Father and Jesus Christ was at the heart of his leadership journey.

The Servant-Leader Apprenticeship model of leadership development is an ongoing and iterative process. This is clearly seen in Joseph’s experiences. Joseph was eventually visited by the angel Moroni, who taught him the plan of salvation and helped him understand God’s ultimate purpose (Joseph Smith—History 1:27–54). This visit served to deepen Joseph’s relationship with Heavenly Father and Jesus Christ because they kept their promise to provide him with more information. The visit also introduced Joseph to the fact that he now had greater responsibility and was expected to teach others what he had learned. This greater responsibility was manifest with his receiving the gold plates and the charge to translate them (Joseph Smith—History 1:59–75). The translation of the plates led to the reception of the priesthood and the gift of prophecy. It also provided Joseph with a model of how Jesus Christ exercised leadership and how he trained leaders. Joseph was able to witness the SLA model of leadership development that he was experiencing himself. He read about Nephi’s experiences and how his leadership skills were developed by Jesus Christ. He also learned about how Christ developed other leaders in the Book of Mormon. This was not the only way that Joseph was taught. He also received the revelations that comprise the Doctrine and Covenants. These revelations increased his understanding of the plan of salvation and Heavenly Father’s work to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man. They also deepened his relationship with Jesus Christ as he was personally tutored and taught what he needed to know to accomplish the responsibilities that he had been given. Among the lessons that Joseph was taught were the importance of repentance (Doctrine and Covenants 3:15–20), the role of Elijah (Doctrine and Covenants 2), the importance of heeding God’s word (Doctrine and Covenants 6:2), the nature of the afterlife (Doctrine and Covenants 76), and what truth is (Doctrine and Covenants 93:24). Through the whole process Christ modeled what it meant to be a leader. Joseph was also given greater responsibility as he was taught and came to understand the things that he was taught. The publication of the revelations received by Joseph were one way that he fulfilled the increased responsibility that was given him.

Joseph was tutored in the implementation of the SLA model as he selected others to help him in the work. He built relationships with the men who would assist him in the work of establishing a church and preaching the gospel. He taught them what he had learned and helped them understand the vision that drives the work. He modeled for them what it meant to be a leader and he then gave them greater responsibility for the work. Many of these experiences are documented in the Doctrine and Covenants.

| Engage in Authentic Activity | Joseph Smith’s leadership experiences occur as he lives his life and engages in the activities necessary to successfully help his family and followers. |

| Build the Relationship | Joseph Smith—History 1:11–13 Joseph reads the scriptures and is prompted to pray. Joseph Smith—History 1:17–20 Christ and Heavenly Father appear to Joseph Smith, who call him by name. Joseph Smith—History 1:27–54 Moroni is sent to Joseph in response to his prayers and teaches him. Doctrine and Covenants 24:1–9 Jesus Christ has lifted Joseph out of his afflictions. Doctrine and Covenants 121–122 Christ comforts Joseph while he is in Liberty Jail. |

| Share the Vision | Doctrine and Covenants 3:16–20 Joseph is taught that the Book of Mormon will save the seed of Lehi. Doctrine and Covenants 35:2 Christ explains his role to Joseph Smith. Doctrine and Covenants 39:4 Christ gives power to become his sons. |

| Provide an Example or Model | Doctrine and Covenants 6:37 “Behold the wounds which pierced my side, and also the prints of the nails in my hands and feet”; Christ demonstrates the depth of his love for humankind to Joseph. Doctrine and Covenants 20:20–28 Mortals become devilish and sensual, and Heavenly Father sends his Son to save them. Doctrine and Covenants 122:8–9 Christ has descended below all things, and he does not expect Joseph to do something he himself hasn’t done. |

| Instruct and Mentor | Joseph Smith—History 1:66–75 Joseph is taught by Moroni. Doctrine and Covenants 3:5–15 Joseph is taught the importance of repentance if he wishes to continue to translate. Doctrine and Covenants 38:26–27 Christ teaches through the parable of the sons. Doctrine and Covenants 39:6 “And this is my gospel—repentance and baptism by water, and then cometh the baptism of fire and the Holy Ghost, even the Comforter, which showeth all things, and teacheth the peaceable things of the kingdom.” Doctrine and Covenants 121:41–46 Christ teaches Joseph how to use the priesthood. |

| Increase Responsibility | Joseph Smith—History 1:59 Joseph receives the gold plates. Joseph Smith—History 1:66–75 Joseph translates the plates, receives the Aaronic Priesthood, is baptized, and receives the spirit of prophecy. Doctrine and Covenants 13 Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery receive the Aaronic Priesthood. The majority of Doctrine and Covenants sections are products of revelations that Joseph Smith received giving him increased responsibility. Doctrine and Covenants 20 Joseph receives revelation on Church organization and government. Joseph is ordained an Apostle of Jesus Christ. Doctrine and Covenants 24:1–9 Joseph is called to translate scripture and to teach. |

Table 5. Selected examples of how Joseph Smith’s leadership journey aligns with the elements of the SLA model of leadership development.

Discussion

Eugene England described The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as “a lay church and radically so—more than any other.”[50] As a lay church, disciples of Jesus Christ are given numerous opportunities to serve as leaders. These can be formal callings within the Church, in addition to informal roles in families and communities. The Servant-Leader Apprenticeship model of leadership development provides a clear methodological skeleton that leaders can use to train new leaders and arm them with the skills needed to accomplish their responsibilities. The scriptures show how Christ used this model to develop the leadership skills of his disciples who serve in a variety of capacities and roles. The model was used with a variety of individuals who felt varying degrees of comfort with their ability to lead, and it gave all of them the skills needed to become strong leaders.

At the heart of the SLA model is relationship building. Christ demonstrated to us the importance of getting to know those who we are tasked to train as leaders. He actively reached out to Enoch, Peter, Nephi, and Joseph Smith. He called many of them by name and knew their hopes and fears. He kept his promises to them and showed that he could be depended on. His relationship with them was not transactional, based on what he needed them to do for him. Rather, it was based on his deep love for them and his desire to help them succeed. He taught and honed their skills by mentoring them while doing the actual work. Developing leaders is not a quick process. Wood notes that “in his short ministry, Jesus could heal and perform miracles in a matter of minutes and teach in a matter of hours, but spent over three years preparing a team of Apostles to lead . . . [This] reveals a sober note—long-term influence takes time and extraordinary patience.”[51] It is the same today. Training leaders requires time and effort invested in the potential leader. This bears repeating—leadership development is a long-term commitment and is most successful when rooted in love for the potential leader. The other components of the SLA model are only possible through the medium of a trusting relationship.

Once a relationship has been established, leaders can help potential leaders develop their leadership skills. As we have seen from the scriptural examples reviewed above, different individuals will need help with different components of the SLA model at different times in their leadership development journey. Having a relationship with the developing leader lets the leader-trainer see where to focus time and effort as far as the other components of the SLA model go: vision, modeling, teaching, and increasing responsibility. Development of these components needs to occur within the context of authentic activity—in other words, practical experience is the best teacher.

Having served in various roles in the Church, including leadership capacities, we have often seen leadership development training take place in a classroom-type or sermon-type setting. The leader-trainer provides direct instruction about how to lead. This instruction is often inspiring, motivating, and deeply well-intentioned. However, this training is also often all the training that is provided. The learners are expected to be able to transfer the principles and skills presented in the classroom or sermon-training context into the authentic real-world context, a feat that the literature on learning theory suggests is obstacle ridden at best and nearly impossible at worst. The SLA model of leadership development used by Jesus Christ highlights that direct instruction is inadequate alone. It must be paired with the other components, and it must be embedded in the authentic context of practice to maximize the growth of the leaders-in-training. The elements of the SLA model can be used by anyone to help others develop leadership skills.

Two examples help to illustrate how this process could occur in a modern Latter-day Saint environment. The first involves a ward Primary president, Maria, training her new counselors in their responsibilities. In this example, the Primary president and the new first counselor, Sofia, have a preexisting relationship, having been friends for twenty years. In this case, because of their existing relationship of mutual trust, a central SLA element, Maria can move immediately into one of the other elements. She focuses her initial efforts on sharing with Sofia her vision for her presidency. Maria describes how she has felt inspired to focus on helping each child feel the love of the Savior personally and invites Sofia to study the scriptures and to pray about how she can contribute to this vision. Maria then explains to Sofia how she wants her to direct the Primary’s opening events each Sunday, which will be one of Sofia’s responsibilities. Understanding the importance of learning contexts, Maria chooses to conduct this training session in the ward building’s Primary room, embedding the learning experience within one of the same physical spaces where Sofia will be expected to apply what she has learned. The president then takes Sofia with her as she visits the homes of each Primary child, modeling for her how she wants her to weave her vision of helping each child feel the Savior’s love into their interactions with the children and their families. After their first home visit, Maria tells Sofia that Sofia will take the lead during the next visit. Following each visit, they discuss what went well and how to improve for their next one. All the while, Maria reinforces with Sofia the love they share. On the following Sunday, Sofia directs the Primary’s opening exercises as she had been instructed. Afterwards, Maria gives her a high five and a hug, and tells her that she “nailed it” (see table 6 below).

On the other hand, Maria has no prior relationship with her new second counselor, Carolina, who has just moved into the ward. The first thing Maria does is focus on building a relationship with her second counselor. She invites Carolina to go to lunch with her and spends time getting to know her and her family. As Maria does this, she comes to recognize that the second counselor already shares her vision, having deep desires to help each child in the Primary feel the Savior’s love individually. As a result, Maria’s next step is to invite Carolina to accompany her on some home visits. Just like with Sofia, Maria models for Carolina how to enact their shared vision in the lives of their Primary children and then shifts responsibility to her for leading the home visits. In between visits, Maria explains to her that one of her responsibilities will be to ensure that every Primary class has teachers and a room to meet in each Sunday. Maria and Carolina discuss the best way to monitor and track this, and they develop a plan for Carolina to assume this responsibility starting the coming Sunday (see table 7 below).

As the Primary president becomes more comfortable with each of her counselors and their individual strengths, she assigns them specific activities and responsibilities in the management of the Primary and allows them to actively run those activities. All of this occurs in the context of doing the work of the Primary. The Primary president is leveraging each component of the SLA model and is adjusting which component to focus on based on the needs of her counselors. She is working hard to ensure that their leadership development occurs in the context of authentic activity.

| SLA Element | Method | Authentic Context |

| Share the Vision | One-on-one training | Primary room in the ward building |

| Instruct and Mentor | One-on-one training | Primary room in the ward building |

| Provide an Example or Model | Trainee accompanies trainer, trainer models the how | Visiting ward members’ homes |

| Increase Responsibility | Allowing trainee to take the lead in home visits, and to direct the primary events | Within members’ homes and in the Primary room of the ward building |

| Build the Relationship | Preexisting relationship of friendship and trust. Continues strengthening of the relationship throughout the other elements | Throughout all the contexts above |

Table 6. Primary president Maria’s work with first counselor Sofia and the order she performed the SLA elements.

| SLA Element | Method | Authentic Context |

| Build the Relationship | Lunch and family visit(s) | Lunch at a restaurant and unnamed other family activity Continued throughout contexts below |

| Share the Vision | Preexisting alignment with vision discovered through relationship building above | Discovered while in their context above and continued reinforcement throughout |

| Provide an Example or Model | Trainee accompanies trainer, trainer models the how | Visiting ward members’ homes |

| Instruct and Mentor | Trainer delivers some direct instruction in between home visits | While out visiting ward members |

| Increase Responsibility | Over the course of the visits trainee assumes responsibility for leading the home visits | Within members’ homes and in the Primary room of the ward building |

Table 7. Primary president Maria’s work with second counselor Carolina and the order she performed the SLA elements

The second example is of interactions between an Aaronic Priesthood teachers quorum advisor named Hien and the fifteen-year-old teachers quorum president named Binh. Binh has been the quorum president for several months, and in that time, Hien has noticed that Binh has strong faith in Jesus Christ, a sincere desire to help his quorum brothers build their faith, and a great relationship with the other young men. Hien has also noticed that Binh expects Hien to lead his quorum presidency meetings, plan all the quorum activities, and report to the bishopric about the quorum activities and progress. Hien recognizes that by relying on Hien to fulfill these duties, Binh is not having the opportunities to develop in his role as the quorum leader and decides to implement a conscientious plan to help Binh develop his skills. He begins by mentoring Binh in the skill of leading a presidency meeting. For their next presidency meeting, he and another adult advisor meet with Binh prior to their presidency meeting. He gives Binh an agenda for the meeting and explains that although he, Hien, will be leading this meeting as before, he wants Binh to watch for specific things he does to keep the meeting on track and resolve the quorum business. Hien then models for Binh the running of an effective meeting. At the conclusion of the meeting, he debriefs with Binh about what he observed and informs him that he will turn over the leading of the next meeting to Binh. Binh is nervous, but Hien responds by describing the confidence he and the Lord have in Binh’s ability to do it.

After their meetings the next Sunday, Hien chats with Binh and one of Binh’s counselors in the hallway of the church. After laughing together about a funny story that Binh recounted from school that week, Hien uses questions to help Binh articulate his vision for the quorum. He then gives Binh some advice on how to share that vision with the rest of the presidency during their next presidency meeting. Binh’s counselor enthusiastically agrees. Binh successfully leads his next presidency meeting with only a few hiccups. The pre-meeting chat with Hien helped to calm his nerves and prepare him, and the post-meeting debrief helped him improve for the next one. Over the next several months, Hien models good leadership for Binh, instructs him, and shifts responsibility over to him and his counselors for planning activities, managing the quorum calendar of activities and teaching assignments, and reporting to the bishopric. Hien frequently tells Binh how proud he is of his progress and uses the fun activities that the group does together to further strengthen their relationship. Though every activity isn’t perfect, Binh grows into his role as the quorum president, and the other young men are able to see the light of Binh’s testimony as their own faith grows as well. Hien utilized all the elements of the SLA model to guide his decisions in helping Binh develop his leadership skills, moving between them as they were needed. see table 8 below).

| SLA Element | Method | Authentic Context |

| Provide an Example or Model | Modeling how to lead an effective presidency meeting | Performed in an actual presidency meeting, rather than a discussion or simulation about a meeting |

| Instruct and Mentor | Specific instructions on how to lead a meeting | Before and after meetings |

| Increase Responsibility | Shifting responsibility of leading meetings, planning activities, arranging quorum teaching assignments to the trainee as he became ready for them | Within the environments of each activity |

| Share the Vision | Helped trainee identify and articulate his vision | In the church hallway |

| Build the Relationship | Scattered throughout the steps above, sharing laughter, confidence, reassurance, and expressions of trust | In a variety of environments: in the church hallway, before and after presidency meetings, and at quorum activities |

Table 8. Teachers quorum advisor Hien’s work with quorum president Binh and the order in which he used the SLA elements.