Rahab and the Perpetuation of Deliverance

Amy H. Fisher

Amy H. Fisher, "Rahab and the Perpetuation of Deliverance," Religious Educator 25, no. 1 (2024): 169–189.

Amy H. Fisher is a part-time independent researcher and speaker and a full-time stay-at-home mom.

The story of Rahab demonstrates the saving power of God in profound and indispensable ways. Rahab is both rescuing others and being rescued herself.

The story of Rahab demonstrates the saving power of God in profound and indispensable ways. Rahab is both rescuing others and being rescued herself.

Abstract: Deliverance is clearly the major theme of the memorable Exodus story, but the Exodus is not the only Old Testament account that teaches profound lessons about God’s redemption. The story of Rahab—the woman of Jericho—is situated in relation to the Exodus through shared images and narrative elements to highlight additional insights about God’s power to save. Specifically, the Rahab story shows that God continues in the temporal, collective delivery of his covenant people even after Egypt. God is also interested in both the temporal and spiritual deliverance of individuals, as shown in the life of Rahab herself. Finally, the story of Rahab has poignant implications for the way that God saves us all spiritually, gathering all those who are willing into his own covenant family.

Keywords: Old Testament, Rahab, deliverance, salvation

Few scriptural stories dramatize God’s power to save as memorably as the Exodus from Egypt. The Exodus’s miracles of deliverance emphatically declare God’s great interest in intervening to deliver his people and confirm his boundless capacity to enact that deliverance. So decisive is the illustration that when the parted Egyptian sea closes behind the freed Israelites, we might be tempted to believe that we have learned all there is to know about God’s saving capacities. But the Exodus does not end or even culminate the Old Testament’s theme of God’s deliverance. This is strongly evidenced in the early chapters of the book of Joshua, in the brief story of Rahab, which demonstrates the saving power of God in profound and indispensable ways. Rahab, in both rescuing others and being rescued herself, illustrates that God’s deliverance expands even more broadly and poignantly than seen thus far in the biblical text.

The Exodus, after all, is about God’s power to save one people, the progeny of the prophets followed throughout the book of Genesis. Rahab’s story, though, woven with thematic threads that bind it to the Exodus, makes it uniquely clear that the same deliverance offered to Israel can perpetuate in many variations to all of God’s faithful. This study will attempt to expound these variations, exploring how carefully crafted allusions to the Exodus throughout Rahab’s biblical account have implications for our understanding of how God’s deliverance perpetuates. First, Rahab most obviously signifies God’s continued interest in Israel’s collective and temporal deliverance. I will show that through attentive study, we might also see how Rahab’s story illuminates God’s interest in personal temporal deliverance and personal spiritual deliverance. Ultimately and most magnificently too, Rahab’s story culminates in a promise of collective spiritual deliverance, wherein God gathers the faithful of all backgrounds into his own family with all the incumbent blessings of inheritance. Unlikely as it seems, these variations on the theme of deliverance from the small story of Rahab are able to widen the impact of the Exodus and teach more profoundly about God’s deliverance than the Exodus can alone.

The often-neglected story of Rahab may initially seem a surprising vehicle for expanding the Exodus’s overarching scheme of deliverance. Rahab is a Canaanite woman living in the border city of Jericho at the crucial moment when the now nation-sized Israelite family prepares for entry into the promised land (see Joshua 1:11).[1] Many generations have passed since the Israelites’ ancestor and namesake had departed Canaan for Egypt with his twelve sons. Israel’s family had grown in Egypt, been enslaved, and then been rescued in miraculous manner. For forty years now the Israelites have camped in the wilderness outside of Canaan, not quite in isolation as we sometimes imagine, but interacting with neighboring tribes, even violently.[2] Rumors of their victories and strength, along with the continued miracles that accompanied them, have drifted across the desert and become a topic of gossip in the streets of Jericho, reaching the ears of Rahab (see Joshua 2:9–11).

When Joshua sends two Israelite spies to gain information about Jericho, they take refuge in Rahab’s home (see Joshua 2:1). The king summons Rahab and demands that she give up the men, presuming she is ignorant of their mission as spies. Rahab speaks for the first time in the narrative, acknowledging that there were indeed two strangers with unknown origins who had come.[3] She claims that the men had already set off through the city with the aim of leaving before the gates closed at nightfall. She encourages the king to send his guards after them, which he does with haste (see Joshua 2:2–5).

The king is a victim of dramatic irony, however. The narrator has already explained that Rahab has hidden the spies for safekeeping in piles of flax upon her roof (see Joshua 2:4). Thus her first spoken words are not actually innocent shrugs of ignorance, but carefully chosen and courageous deceits uttered in a tense and potentially life-threatening moment, for what if the king discovers her treason? A brief narrative gloss (“and the woman took the two men, and hid them”—only six words in the original Hebrew) is enough to wrench the reader’s perception of Rahab from bystander to woman of mettle and agency (Joshua 2:4). Through the quick-thinking and daring of this Canaanite, Rahab likely saves the lives of two Israelite men. Her abetment of these men of Israel is as heroic as it is unanticipated and becomes the jumping off point for Rahab’s role in the Bible’s ongoing theme of deliverance.

Collective Temporal Deliverance

Rahab’s rescue of the two Israelites prefigures the Lord’s ongoing efforts on behalf of Israel’s collective temporal welfare. Indeed, the beginning of the book of Joshua repeatedly echoes scenes from the Exodus, even explicitly in order to show the continued interference of Israel’s God on their behalf: “This day will I begin to magnify thee [Joshua] in the sight of all Israel, that they may know that, as I was with Moses, so I will be with thee” (Joshua 3:7; emphasis added). Thereafter, in a direct recurrence of the crossing of the Red Sea, the waters of the Jordan River “rose up upon an heap” and “all the Israelites passed over on dry ground” (Joshua 3:16–17). In reperforming this most spectacular of the Exodus miracles, the Lord was teaching the children of Israel that it was God, not Moses, who was orchestrating their deliverance all along, and that he was continuing to work miracles on their behalf even now that human leadership had passed from Moses to Joshua.

It is not only Joshua, though, who participates in divinely intentioned reenactments of the Exodus. More implicit but nonetheless integral recurrences echo throughout the story of Rahab as, with a literary technique known as intertextuality, those who crafted the text accentuate like images, words, and phrases in order to underscore connections and common themes between the two stories.[4] Together, the Exodus recollections throughout Rahab’s story “orient” readers forward, allowing us to anticipate a campaign that will be as successful in Canaan as it was in Egypt.[5] The imagery of deliverance begins again as if from the first to show that God’s power can deliver his people not only from bondage but also into a promised land.[6]

Among the many echoes possible to find in the story of Rahab, of most interest to this study are those that relate to the women who bring forth the first fledgling rescues of the Exodus.[7] Rahab hides the fugitive Israelite males in “stalks of flax”—willowy green reeds topped with feathery blooms—evoking an earlier guardian woman who hid her condemned Israelite son Moses in reedy “flags by the river’s brink” (Joshua 2:6; Exodus 2:3).[8] Then (and more prominently), Rahab’s saving actions mirror those of two midwives in Exodus chapter one. Pharaoh, whose domineering plans devolved from subjugation of the vastly grown Israelite family to infanticide, had enlisted midwives named Shiphrah and Puah to kill the male Hebrew babies as they were born (see Joshua 2:4).[9] The midwives were called to the presence of the king to account for an apparent lack of obedience. In fact they had been flaunting Pharaoh; in a narrative gloss strongly similar to that in the Rahab account, the text has already mentioned that they “did not as the king of Egypt commanded them, but saved the men children alive” (Exodus 1:17). Rather than admit their dereliction, they, like Rahab, misdirect, inventing the excuse that Israelite mothers are especially fit for childbearing and do not require midwives to deliver. This clever lie, like Rahab’s, was accepted by the king (see Exodus 1:18–20).

It is not only narrative and structural parallels in their stories that link Rahab and the midwives. Rahab, as a Canaanite, is clearly a rescuing foreigner but so, surprisingly, Shiphrah and Puah may have been. The phrase “Hebrew midwives” is as ambiguous in the original Hebrew as it can be in the English, meaning either “midwives who are Hebrews” or “midwives to the Hebrews” (Exodus 1:15). Medieval commentaries emphasize the view that the midwives were Israelites, but there is a lasting, more “fringe” body of commentary that includes Shiphrah and Puah in lists of female “converts among the Gentiles” (which relevantly contain Rahab as well).[10] This (generally earlier) exegetical view that the midwives were Egyptian derives from, among other things, the assumption that Pharaoh would not have trusted Israelites to enact such macabre orders against their own.[11] In general, I find defenses of their Egyptian identity persuasive, especially when the stories of Rahab and the midwives already intertwine so carefully. That they may likewise have paralleled one another as lifesavers of foreign identity seems to me both to justify the biblical author’s intertextual entwining and to enlarge the implications of their association.

It is hardly remarkable, after all, if midwives of Hebrew origin “fear God,” the reason given for Shiphrah and Puah’s defiance of Pharaoh (Exodus 1:17). But it would be extraordinary if Egyptians had risked their lives on behalf of a minority group because reverence for a non-national God superseded their fear of Pharaoh.[12] Nonetheless, this is essentially the same explanation given to Canaanite Rahab for her deception. In her own voice, Rahab explains to the spies that, after hearing of God’s redemptive works on behalf of the Israelites, “I know that the Lord hath given you the land. The Lord your God, he is God in heaven above, and in earth beneath” (Joshua 2:11).[13] The one, omnipotent Israelite God is not a part of the Canaanite pantheon of power-sharing idol-gods, but Rahab, in hearing tales of miracles and supernatural strength, has come to believe that unlike the idols the people of Jericho worshiped, the Israelites’ God is actually acting in the affairs of men. He has true power, specifically to save; they have none. Rahab’s motivation for risking her life to save those of the Israelite spies, then, ties her choice and its catalyst tightly to the Egyptian Shiphrah and Puah, as she joins them as God-fearing Gentiles who deliver God’s chosen people.

In the collective, temporal deliverance the children of Israel receive by way of Rahab, the allusion to the midwives of Exodus, regardless of their ethnic origins, is deeply symbolic. The word deliver has many meanings pertinent to this discussion, among them “to set free or liberate” (as in God’s deliverance of the slaves), “to . . . save” (as in Rahab’s and the midwives’ deliverance of the Israelites from death), “to give into another’s possession or keeping” (as in God’s deliverance of the promised land to his covenant people), as well as—markedly—“to assist [a mother] in bringing forth young” (the role of a midwife).[14] Therefore, Rahab delivers the two Israelite spies from the capture or death that otherwise awaits them. As she does so, she prophesies of the success of their mission.[15] The spies are then able to confidently report to Joshua that success—a new land but also a new life—will be delivered to them in Jericho. As Tikva Frymer-Kensky piquantly observes, by giving Rahab’s story echoes of the Hebrew midwives, the biblical narrator paints Rahab as the midwife who facilitates the birth of the nation Israel in its new land.[16] Delivered by God from slavery and death in Egypt, the next generation looks forward to a new existence beyond the Jordan River. And there, just as this new birth commences, Rahab is present to serve as God’s delivering hands.

Personal Temporal Deliverance

Rahab is not merely an instrument for Israel’s continued deliverance, however. It is at this point in the narrative that the rescue provided by Rahab translates into rescue for Rahab, and it is this aspect of the story that demonstrates that God’s deliverance encompasses more than one man and his posterity. With Rahab, the Lord begins to show that deliverance is available to all who trust him (Daniel 3:28).

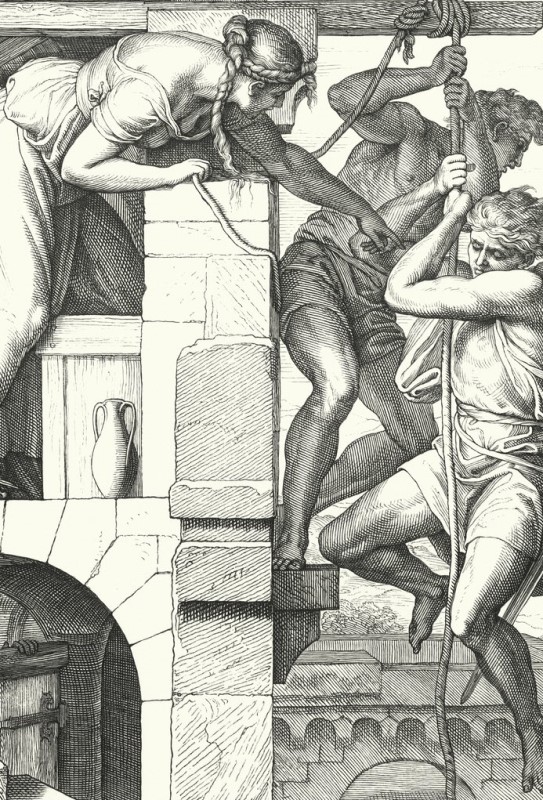

This occurs as Rahab facilitates the escape of the Israelite spies down the outer walls of the city. Knowing that they will return with Joshua’s army, she asks for her life in return for theirs: “Now therefore, I pray you, swear unto me by the Lord, since I have shewed you kindness, that ye will also shew kindness unto my father’s house, and give me a true token: And that ye will save alive my father, and my mother, and my brethren, and my sisters, and all that they have, and deliver our lives from death” (Joshua 2:12–13).[17] The men covenant with her to do so and offer an intriguing token as pledge of this covenant: “Behold, when we come into the land, thou shalt bind this line of scarlet thread in the window which thou didst let us down by” (Joshua 2:18; emphasis added). Rarely does the Old Testament provide physical description for people or objects without some significant relevance.[18] That the thread at Rahab’s window is described as scarlet both here and again in verse 21 is something to note. Close attention to the structure of the spies’ promise and conditions as outlined in the text illuminates what I believe to be a compelling connection.[19]

Two instances of the phrase “to bind the scarlet line in the window” enclose exactly two repetitions of the word blood in a typical textual envelope structure.[20] Included within this envelope is the promise that

Thou shalt bring thy father, and thy mother, and thy brethren, and all thy father’s household, home unto thee. And it shall be, that whosoever shall go out of the doors of thy house into the street, his blood shall be upon his head, and we will be guiltless: and whosoever shall be with thee in the house, his blood shall be on our head, if any hand be upon him (Joshua 2:18–19; emphasis added).

Given the strong relationship between the color red and blood, especially in ancient contexts like this one, the use of “scarlet” here seems to signal special attention to the role of blood in instructions strikingly similar to those given to Moses in preparation for the tenth plague (in which blood plays a salient part).[21] In fact, there are a number of elements from Rahab’s story that align with details from Exodus chapter 12:

| Joshua 2 | Exodus 12 |

Scarlet at a threshold | |

| Thou shalt bind this line of scarlet thread in the window (v. 18) | And they shall take of the blood, and strike it on the two side posts and on the upper door post of the houses (v. 7) |

As a token of a relationship of protection | |

| Swear unto me by the Lord, since I have shewed you kindness, that ye will also shew kindness unto my father’s house, and give me a true token (v. 12) | And the blood shall be to you for a token upon the houses where ye are: and when I see the blood, I will pass over you, and the plague shall not be upon you to destroy you, when I smite the land of Egypt (v. 13) |

Protecting a full household | |

| And thou shalt bring thy father, and thy mother, and thy brethren, and all thy father’s household, home unto thee (v. 18) | In the tenth day of this month they shall take to them every man a lamb, according to the house of their fathers, a lamb for an house (v. 3) Take you a lamb according to your families (v. 21) |

But egress through the door brings death | |

| And it shall be, that whosoever shall go out of the doors of thy house into the street, his blood shall be upon his head (v. 19) | None of you shall go out at the door of his house until the morning. For the Lord will pass through to smite the Egyptians; and when he seeth the blood upon the lintel, and on the two side posts, the Lord will pass over the door (vv. 22–23) |

The color of the thread is unusually highlighted in order to situate the token as part of a second passover, this time uniquely arranged for Rahab and her household under covenant—not yet with God, but with the Israelite people instead, who will come as destroyers able to pass her by because of the scarlet mark at her window. It is no coincidence that after the Israelites cross the Jordan River, and immediately prior to their march on Jericho, the tribes of Israel perform the Passover for the first time since entering the promised land (see Joshua 5:10). Readers are meant to have the Passover forefront in their minds when Rahab and her family are rescued during the battle, for their salvation is literally the next iteration of Passover liberation.

Here, though, the parallel is reconfigured in a deeply personal, rather than communal way. Where the Passover in Egypt was collective—God intervening in history to influence the affairs of nations—here the new Passover is individual, on behalf of one believing woman and her immediate family. We see that God’s deliverance will persist, and not only among those born into the Israelite nation but also to individuals outside it who seek participation in his dealings on earth.

Indeed, the first Passover was never meant to be a one-time occurrence. From the beginning, from before the Passover even happened, God mandated that its memory be commemorated with an annual, ritual reenactment now called a Seder (see Exodus 12:14–20).[22] The reenactment was to allow each passing generation to symbolically participate in the Passover and to internalize its meaning in a personal way.[23] This becomes the everlasting power of the Seder. When Jews today celebrate the Passover each spring by eating unleavened bread and bitter herbs, they recognize the ritual as if it was the first Passover, as if that deliverance had happened to themselves, rather than to ancestors three thousand years old. In the words of the Passover Seder itself, spoken in Jewish homes the world over:

In every generation it is one’s duty to regard himself as though he personally had gone out from Egypt, as it is written (Exodus 13:8): You shall tell your son on that day: “It was because of this that [the Lord] did for ‘me’ when I went out of Egypt.” It was not only our fathers whom the Holy One redeemed from slavery; we, too, were redeemed with them, as it is written (Deuteronomy 6:23): He brought “us” out from there so that He might take us to the land which He had promised to our fathers.[24]

“Stabilizing” the memory of deliverance with prescribed physical action is meant to reinforce both the covenant relationship with God their deliverer and to perpetuate acknowledgment that the God of their covenant is a God of power who keeps his promises and continues to act in their lives on their behalf.[25]

Though Jews acknowledge during the Seder that God would be worthy of praise had he stopped after any one of the wonders of the Exodus, the power of the personalized reenactment is exactly that he didn’t stop and will not cease his deliverance even as the generations pass.[26] To say that it is personal, as if it had happened to us, would be a measly token if God’s agency and power did in fact remain firmly in the past. Had God acted once in Egypt but never delivered his children again, the Passover ceremony still celebrated by Jews the world over would have puny significance. The true vital force of the Passover symbol is embodied in Rahab as echoes of the Passover encircle her own window and family and affirm that her deliverance is not a random stroke of mere good fortune. That her deliverance happened in this way testifies that God is still capable of deliverance and will continue to provide actual, real deliverance to all individuals who trust him.

Personal Spiritual Deliverance

Admittedly, when Jews today perform the Passover Seder with attention to their own personal deliverance, it is generally not from physical bondage or battle that participants’ minds turn. The ritual is personal because in this reenactment, Egypt and Pharaoh stand in for a life led without God, for the worldly captivity of the fallen “natural man,” and for any other form of downtroddenness, injustice, or stagnation the world imposes.[27] Faithful Jews trust that, just as in the first Passover, God will deliver them from their own individual, often spiritual, Egypts. Rahab’s story is relevant in consideration of this kind of personal spiritual deliverance, too, as we consider the end of Rahab’s story in light of her background.

Rahab is described as a Canaanite from the doomed city of Jericho, but immediately, before she is even identified by name, Rahab is described as a harlot (Joshua 2:1). There are several practical reasons the text might distinguish her thus; her professional dealings likely explain her heightened access to the male gossip of the city, which acquainted her with news of the Israelites’ strength (and that of their God!) and allowed her authoritative insight into the resulting fears of the Jericho men (see Joshua 2:9–11).[28] It may also explain how the spies ended up in her home, situated as it was on an outer wall of the city, where skulking men from both within and without might come without detection (see Joshua 2:15). But given that Rahab is such a heroine on behalf of the Israelites, her identification as a harlot has long troubled orthodox commentators. One tradition, not infrequently cited, claims that the Hebrew profession zonah can acceptably read more liberally as “innkeeper,” or “purveyor of provisions.” This tradition seems to originate around the beginning of the Common Era when Josephus, a Jewish historian, identified Rahab as an innkeeper, and Jonathan ben Uzziel, author of a rabbinic translation into Aramaic of the prophetic books of the Bible, translated zonah with a word meaning “seller of baked goods.”[29] However, while a Hebrew word usually has a number of possible meanings, in all other biblical contexts zonah refers unambiguously to fornication, making it almost certain that Rahab was literally a harlot in the plain sense of the word.[30] Though it seems tempting to whitewash Rahab’s past, the reading is unsound and inadvertently reflects a belief that God’s saving reach is limited and can’t possibly extend as far as harlotry. Acknowledging the dark side of her past, on the other hand, allows us to appreciate the full measure of the divine deliverance she experienced.

For, after all, God’s deliverance has never just been temporal (see Matthew 9:2–7). While God is concerned with the physical well-being of his children (as evidenced by Israel’s emancipation from slavery and Rahab’s deliverance from death), his interests continue decisively on, touching the state of the Spirit in the most encompassing ways. To this end, the Exodus is not, in fact, fundamentally an escape to freedom. Instead, the people are delivered immediately to Sinai, where they receive a law under covenant.[31] Significantly, the very words of this Sinaitic covenant represent a new closeness with God directly in terms of his earlier deliverance: “Ye have seen what I did unto the Egyptians, and how I bare you on eagles’ wings, and brought you unto myself. Now therefore, if ye will obey my voice indeed, and keep my covenant, then ye shall be a peculiar treasure unto me above all people” (Exodus 19:4–5). In other words, the Lord brought the people forth from slavery so that they could circumscribe every part of their lives within God’s covenant framework, ensuring their continued ability to abide in a close, “peculiar” relationship with him.[32]

That this covenant relationship could be personal, as well as collective, and that God’s deliverance could be applied to a full range of spiritual suffering was clearly understood by later Israelite authors. The psalms put particular trust in God’s ability to deliver “my soul from death, mine eyes from tears, and my feet from falling” (Psalm 116:3–8).[33] The Book of Mormon prophet Alma makes perhaps the clearest connection between the original Exodus and personal deliverance, both from hardship and from sin:

And I have been supported under trials and troubles of every kind, yea, and in all manner of afflictions; yea, God has delivered me from prison, and from bonds, and from death; yea, and I do put my trust in him, and he will still deliver me. And I know that he will raise me up at the last day, to dwell with him in glory; yea, and I will praise him forever, for he has brought our fathers out of Egypt, and he has swallowed up the Egyptians in the Red Sea; and he led them by his power into the promised land; yea, and he has delivered them out of bondage and captivity from time to time...and I have always retained in remembrance their captivity; yea, and ye also ought to retain in remembrance, as I have done, their captivity. (Alma 36:27–29)

Alma recognizes that God has delivered him from prison, bonds, and death, just as the Israelites were delivered from slavery. But he implies that in remembering the deliverance of the Exodus, he is also better able to recognize the rescue he receives from trials, troubles, and afflictions (representing various kinds of emotional and spiritual distress) as well as God’s ability to lift him up into heavenly exaltation.

Clearly over time God’s deliverance came to mean more than physical rescue. Though it is not depicted in the Rahab account as clearly as in Psalms or the Book of Mormon, there are textual intimations here, as early as the book of Joshua, that portray rescue as spiritual relief.[34] We learn that after Rahab’s life was spared, “she dwelleth in Israel even unto this day” (Joshua 6:25). Rabbinic commentators have long interpreted this phrase to mean that Rahab cast off her prior ways and joined Israel with full heart and conviction, a supposition supported perhaps by this later promise from Jeremiah: “And it shall come to pass, if they will diligently learn the ways of my people, to swear by my name, The Lord liveth; as they taught my people to swear by Baal; then shall they be built in the midst of my people” (Jeremiah 12:16; emphasis added).[35] For those Canaanite idolators who come to testify—like Rahab—that “the Lord liveth,” even though they once swore in Baal’s name, dwelling “in the midst of” God’s people becomes the mark of established participation in God’s blessings and favor.

Rahab’s full fellowship, represented by dwelling among the people, plays on the reminiscence that as a harlot, Rahab lived in or on the outer walls of Jericho, on the very margins of her own society. The connotation of encompassing closeness within the Israelite community that Rahab experiences is much stronger in the original Hebrew than in the King James English. That Rahab dwelled b’qerev Israel, translated merely “in” Israel in the King James Version, actually comes from a root signifying the inward parts of a body. A more accurate translation here would be that she dwelled “in the midst” of Israel, or even thickly in the midst, utterly embedded within the people, a far cry from her marginal existence in Jericho.[36] Her previous lifestyle of worldliness, sin, and possibly oppression contrasts sharply with the blessings of inclusion among God’s people that come after her expressions of faith. What begins as a temporal deliverance from death additionally becomes a deeply inner rescue. Thus, by measures both poignant and personal, Rahab confirms the spiritual fulfillment of the Exodus and represents the breadth of God’s expansive plan.

Collective Spiritual Deliverance

It is Rahab’s spiritual transformation, represented by her complete integration with the Israelite people, that leads to the most profound implication of her deliverance. The original promised reward for helping the spies was mere deliverance from harm. Her resulting relationship with Israel, though, extends to her dwelling in their midst and, according to both Jewish and Christian tradition, to her marriage into one of Israel’s preeminent families. Thereafter, Rahab remarkably becomes the grandmother of prophets, priests, and kings. This is an astonishing supersession of the preliminary terms of her deliverance and a stunning personal redemption for Rahab the erstwhile idolatrous harlot. I believe her inclusion in the family of Israel also has the most expansive ramifications for our exploration of deliverance themes in Rahab’s story. With such a culmination, Rahab’s story becomes a pattern for all peoples of the world who will one day be gathered forever into the family of God (see Ephesians 1:10).

Jewish tradition, developed from a series of nuanced textual extrapolations, claims that Rahab married Joshua and became the ancestress of eight priest-prophets, including Jeremiah.[37] Christian tradition, drawn from Matthew chapter one, recognizes Rahab instead as the wife of Salmon and mother of Boaz, who went on to marry Ruth (see Matthew 1:5). David, king of the united tribes of Israel, comes through this line, as does Jesus Christ, the Christian King of kings. Nothing demonstrates Rahab’s complete assimilation and unification into her new community more than her marriage and prestigious place in the genealogies of the people.[38] This represents more than an incidental, singular opportunity for a foreigner seeking a new life. Rahab shows the possibilities of adoption as complete heir to the blessings and birthright of the great family of Israel.

Adoption is a powerful analogy precisely because Israel continues in essential principle as a family (despite its immense numbers and nation-like laws), an identity that is integral to their—and now Rahab’s—relationship with God. The Exodus narrative configures God in the role of father to the posterity of Israel, depicting him as kinsman patriarch in a tribal environment where the role of patriarch comes with axiomatic legal responsibilities.[39] One such patriarchal responsibility is to redeem—a legal term that refers to the repurchase of kinsmen taken into slavery. When God says to Moses, “And thou shalt say unto Pharaoh, Thus saith the Lord, Israel is my son, even my firstborn: And I say unto thee, Let my son go, that he may serve me,” God’s reference to sonship is not induced for sake of sentiment nor to teach doctrine about the origins of human spirits (Exodus 4:22–23).[40] It is meant as a legal claim, to set forth stakes that would have been well understood to Pharaoh in this tribal context. If God claims the role of tribal father, then bringing his firstborn out of slavery is the foremost requirement of his position and every resource at his (significant, he will soon show) disposal will be enacted to that end.

The biblical narrative that relays God’s successful redemption from Egypt contains the elements of any ancient panegyric to tribal gods for perceived rescue in times of trial.[41] What sets apart the Exodus’s triumphant recollection of Israel’s divine deliverance is what comes before these feats of favor, in Genesis. For the story of this family ultimately starts, after all, with their God’s creation of the earth and all the peoples in it.[42] God only gives peculiar attention to Abraham, Israel’s original progenitor, so that through him (and by extension, through the posterity God endows upon him) “shall all families of the earth be blessed” (Genesis 12:2–3; emphasis added). In other words, God claims the posterity of Abraham’s grandson Israel as his own children, and grants them blessings of protection, redemption, and deliverance accordingly; but in doing so, his much greater purpose is to commit blessings upon all the families of the earth.

What is incredible and unique about this family of Israel, especially in their henotheistic context, is not that God had claimed them as his children, performing mighty acts in order to redeem and deliver them;[43] rather, it is that this God claims all those who believe in him as his children, and desires to bless all humankind with the blessings of kinship he has already shown to Israel.[44] Additional scripture sets forth the concept of the kinship adoption of the faithful explicitly, such as in John 1:12: “But as many as received him, to them gave he power to become the sons of God, even to them that believe on his name” (emphasis added).[45] The Book of Mormon goes further to acknowledge that patriarchal redemption (again, one of the key blessings of family relationship) is available for the faithful who become the children of God: “And as many as have received me, to them have I given to become the sons of God; and even so will I to as many as shall believe on my name, for behold, by me redemption cometh” (3 Nephi 9:17). Adoption as children of God will not be limited to a few faithful outliers, as the Book of Mormon makes clear: “Marvel not that all mankind, yea, men and women, all nations, kindreds, tongues and people, must be born again; yea, born of God, changed from their carnal and fallen state, to a state of righteousness, being redeemed of God, becoming his sons and daughters” (Mosiah 27:25). In this the prophet Alma is explicit: God’s imperative is to adopt all people as his sons and daughters and heap upon them the redemptive blessings his kinship affords.

Emphatic and marvelous as God’s deliverance from Egypt is, this pressing concern to redeem all humankind is missing from the narrative. In the book of Joshua, however, Rahab confirms the validity of God’s universal mission as an immigrant to Israel-the-nation and specifically through her adoption into Israel-the-family. Admittedly, my claim that the story of Rahab emphasizes a broadened deliverance challenges conventional interpretations of the book of Joshua, which view it as especially particularistic, apparently condoning the mass destruction of anyone who was not already an Israelite. Interestingly, while the first few chapters of the book of Joshua are most often remembered for the walls of Jericho that “come tumbling down,” Richard Hess analyzes the ways in which the story of Rahab is interwoven with the destruction of Jericho, pointing out that the word count depicting Rahab’s deliverance is almost as high as that narrating Jericho’s defeat. Hess asserts that for the author of the book of Joshua, “the salvation of Rahab and her family is as important as the destruction of Jericho.”[46] In fact, Hess suggests that bringing forth faith in God was always a primary purpose of Joshua’s Canaan campaign. He points out that the Hebrew word used in Joshua 2 for spies, meraggelim, is used elsewhere to signify those who might “disseminate information and seek to rally people to their side.” Thus, Hess believes Joshua’s spies were actually proselytes, in Jericho not merely to discover information useful for Jericho’s overthrow, but actually to “make known the plan of God to those they find who are loyal to God.”[47] Whether or not the spies were truly undercover missionaries, what is clear is that Rahab, who is prodigiously incorporated without question into Israel despite her identity as a Canaanite, is placed prominently at the forefront of Israel’s campaign. Such placement might certainly show that adoption was always the preferred alternative to destruction.

So clear was it to early Christians that Rahab represented God’s expanding opportunities for gentile nations, that patristic commentators—who saw the church as a fulfillment of those opportunities—took an eager interest in her story. Church fathers duly noted that harlotry figuratively represents idolatry throughout the Old Testament, and they acknowledged that as both Canaanite and harlot, Rahab initially represents the most lost of the pagan and gentile world.[48] But Rahab’s words of faith and works of courage, both commended separately in the New Testament, led these commentators to attest Rahab’s complete conversion and claim her broadly as a symbol for the gentile church.[49]

One specific aspect of Rahab’s story led these commentators to recognize Rahab as a representation of the collective gentile believers, rather than merely the individual convert. Rahab, beautifully, includes her own family in her plea for protection, petitioning on behalf of her father, mother, sisters, brothers, and “all that they have” (presumably her nieces and nephews; Joshua 2:13). Patristic commentator Cyprian (third century), sees this as an example of the saving power of the church, noting that just as crossing the threshold of Rahab’s home would forfeit the lives of any family member, so leaving the church is fatal to the soul.[50] More relevant for our discussion is his observation that this gathering of Rahab’s family into the safety of her home comes inextricably from the principle of unity, quoting Jesus who says, “And there shall be one flock and one shepherd” (John 10:16).[51] In fact, when the spies direct Rahab to “bring thy father, and thy mother, and thy brethren, and all thy father’s household, home unto thee,” the original Hebrew word for “bring unto” could more literally be translated as “gather in,” perhaps evoking to the figurative- and universalist-minded the image of God’s arms reaching to gather in his own broad family to a safe and unified heavenly home (Joshua 2:18).

Clearly the authors of the book of Joshua did not write the story of Rahab with the gentile Christian church in mind. But the evaluations of early church fathers tellingly capture the universal impulse of Rahab’s story, as she who was outsider, harlot, and idolator becomes so fully enveloped within God’s people as believer, wife, and mother. It is perhaps no coincidence that Rahab’s name (from the Hebrew raḥav) means “broad” or “wide.” For after the Exodus had shown the children of Israel God’s great power to save them, Rahab comes at a pivotal point in their history to represent the widening of God’s saving power and the broad, sweeping arm of the deliverance on offer to all those who trust in him.[52] That this Canaanite becomes a literal forebear of Jesus Christ is a poignant reminder that “all nations, kindred, tongues and people” who exercise faith in him are welcomed into God’s divine family, there to receive the deliverance his paternity proffers and the safety his house affords.

Conclusion

The Israelites’ Exodus from Egypt has often rightly been evoked as supreme testament to God’s delivering power. Many hundreds of years after that event, however, the prophet Jeremiah prophesied that the Exodus, with its limited, particularist scope, would fade as the ultimate symbol of God’s salvation (see Jeremiah 16:14–16). Instead, the Lord promises that “I will put my law in their inward parts, and write it in their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people. And they shall teach no more every man his neighbour . . . saying, Know the Lord: for they shall all know me, from the least of them unto the greatest of them, saith the Lord: for I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sin no more” (Jeremiah 31:31–34). Surely Jeremiah foresees a day when all people upon the earth, no matter their origin or background, acknowledge that the God of Israel is “God in heaven above, and in earth beneath” (Joshua 2:11). And God assures us that he, as the Great Deliverer and Divine Kinsman, will open his arms wide to redeem, rescue, and gather them all.

Rahab both foreshadows and fulfills this universal mission of God. In rescuing the Israelite spies, Rahab represents God’s continuing provision on behalf of his covenant people. In her own rescue from the destruction of Jericho, we see how that provision expands to include any who trust him. God’s provisions are not merely physical and temporal but extend to the inner spirit, as illustrated by Rahab’s full inclusion among the people despite her worldly past. And in the ultimate signal that her sins were forgiven and forgotten, Rahab was gathered into the family tree of Jesus Christ himself, representative of God’s efforts to deliver all nations, kindreds, tongues, and people into new life within his own family, with birthright blessings and an inheritance in God’s promised land.

Notes

[1] On Israel as a nation, see Genesis 46:3 and Exodus 19:6.

[2] See, for example, Exodus 17:8–13; Numbers 14:45; and Numbers 21:21–25.

[3] Robert Alter, scholar of the Hebrew Bible and modern literature, and therefore highly attuned to narrative style, has pointed out that a biblical character’s first words are often emblematic of her overarching character, personality, or relationship to God. The Art of Biblical Narrative (New York: Basic Books, 2011), 93–94.

[4] Quite different from modern scholarly commentary that sees the crafters of the biblical text as quaint, creatively ignorant, and infighting, Jewish rabbinic commentary assumes a deep coherence throughout the text, believing every word to be intentionally chosen to further the purposes of God. More recently, a small collection of interdisciplinary scholars has analyzed the Old Testament’s intricate and complex structural forms to strengthen the Jewish position that the text was carefully and intentionally crafted, a position I assume throughout this paper. For more on this scholarly divide, see Alter, Art of Biblical Narrative, 13–23; and Yoram Hazony, The Philosophy of Hebrew Scripture (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 12–23.

[5] I quote the word orient here directly from literary critical scholar Robert Alter, who argues that reader orienting is the purpose of biblical “type scenes.” While Rahab’s story is not precisely the kind of type scene Alter expounds, intertextuality here functions with the same kind of orienting purpose. Alter, Art of Biblical Narrative, 77.

[6] Connections between the book of Joshua generally and the books of Moses, especially Deuteronomy, have been well recognized. See Carol Meyers, “Joshua,” in The Jewish Study Bible, ed. Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 462, for example, who notes that especially in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries it was so common to view Joshua as a literary continuation of the Moses saga that scholars regularly referenced a Hexateuch (involving the first six books of the Old Testament), instead of the much more standard five-book unit, the Pentateuch. What has not been widely discussed, however, are the captivating parallels between Rahab and especially the women in the earliest chapters of Exodus, strongly furthering deliverance themes.

[7] Tikva Frymer-Kensky calls the story of Rahab “a masterpiece of allusive writing.” For more on intertextual allusions throughout Rahab’s story, see Frymer-Kensky, “Reading Rahab,” in Tehillah Le-Moshe: Biblical and Judaic Studies in Honor of Moshe Greenberg, ed. Mordechai Cogan, Barry L. Eichler, and Jeffrey H. Tigay (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1997), 57–67.

[8] See Tikva Frymer-Kensky, Reading the Women of the Bible: A New Interpretation of Their Stories (New York: Schocken Books, 2002), 36 for more evidence on this particular parallel.

[9] It is worth noting that it is the women of these stories who are named and not the kings.

[10] Moshe Lavee and Shana Strauch-Schick, “The ‘Egyptian’ Midwives,” TheTorah.com, https://

[11] See Shadal (Samuel David Luzzatto), commentary to Exodus 1:15, who analyzes other rabbinic arguments for and against their foreign identity and falls firmly on the gentile side of the debate. https://

[12] That Shiphrah and Puah feared God might initially seem to confirm their Israelite identity. However, because this is fear, or reverence, of the more universal God El (“yir’at ’elohim”—a phrase only used biblically in reference to foreigners), rather than the more common fear of the particularist “Lord” of Israel (“yir’at yhwh”), their deference to God has actually been used to strengthen arguments for their non-Hebrew lineage. See Jan Assmann, The Invention of Religion: Faith and Covenant in the Book of Exodus (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018), 107.

[13] For more on Rahab’s faith as tied to the historic, redemptive works of God, see Richard S. Hess, The Old Testament: A Historical, Theological, and Critical Introduction (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2016), 174–75.

[14] Dictionary.com, s.v. “deliver,” https://

[15] For more on Rahab’s assurance to the spies as prophecy, see Frymer-Kensky, Reading the Women, 297–98.

[16] Frymer-Kensky, Reading the Women, 36. Other commentators have suggested that the cord by which Rahab eventually lets down the spies from her window relates figuratively to the umbilical cord, further strengthening this association between Rahab and midwifery. While the words for umbilical cord (shor) and the rope used here (ḥevel) are not the same in Hebrew as they are in English, there is an intriguing linguistic connection, as the word used for rope does share the same triconsonantal root as the word for birth pains. In fact, use of the root ḥ-v-l in Isaiah 66:7 specifically relates to the figurative birth of a new Israel, quite like the birth of Israel anew in the promised land precipitated by this episode with Rahab and her rope. See Francis Brown, S. R. Driver, and C. A. Briggs, eds., A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1951), s.v. “חֶבֶל” and “חֵבֶל” (hereafter cited as BDB).

[17] This entreaty follows covenantal form in its exchange of a promise and token and in Rahab’s plea for ḥesed, translated here as “kindness.” On the covenantal nature of ḥesed, see Jon D. Levenson, The Love of God (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016), 24–25.

[18] Alter, Art of Biblical Narrative, 60, 101–2.

[19] Many commentators, both ancient and modern, claim that the reference to scarlet is part of a lurking motif of sensuality. While a symbolic reminder of Rahab’s disreputable past may reinforce the surprising nature of her assistance, her professional identity as a harlot otherwise lacks bearing in the immediate context, making it a much weaker explanation for the color’s inclusion than the one I present according to textual and structural evidence.

[20] Regarding envelope structures, see Alter, Art of Biblical Narrative, 33.

[21] Though not expressly used here, the more general Hebrew word for “red” (adam) is derived from the word for “blood” (dam). For more on this, as well as the general linguistic and anthropological connections between “red” and “blood,” see Guy Deutscher, Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2010), 91–92.

[22] The commandment to commemorate an annual Passover feast was reiterated a number of times throughout the wilderness years and can be found in each of the remaining books of Moses.

[23] Jan Assmann speaks of the effect of performing the Passover ritual as the “transformation of semantic memory (what we have learned) into episodic memory (what we have experienced).” Invention of Religion, 167–68.

[24] Rabbi Nosson Scherman, trans., The ArtScroll Family Haggadah, ed. Rabbis Nosson Scherman and Meir Zlotowitz (Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications), 45. The Haggadah is loosely canonized (though with various editions much like Bible translations) as a kind of script to use on the night of the Passover Seder. It guides participants through the ritual meal and includes speaking parts, songs, instructions for ritual action at established times, and commentary on the story of the Exodus.

[25] The word stabilizing here is quoted directly from Jan Assmann, Invention of Religion, 193. Assmann accepts Nietzsche’s belief that memory is a fleeting thing and can be retained only through physical ritual. Unlike Nietzsche, Assmann does not believe that such physical ritual must be violent or painful to be effective, as witnessed in part by the thousands-year communal impact of the joyous Passover Seder. See Invention of Religion, 166–67, for more about how the Passover ritual engages the whole person with the purpose of personalizing the freedom made possible by the Passover.

[26] One favorite Seder song is a lively, many-versed lyric known as Dayenu, which essentially asserts that even if God had ceased his assistance after any particular wonder of the Exodus, his help would still have been “enough to make us immeasurably grateful.” Scherman, ArtScroll Family Haggadah, 43. (“Enough for us” is the meaning of the chorus word dayenu).

[27] See Assmann, Invention of Religion, 167. The introduction to one of the popular Haggadot states, “There is another slavery, another degradation, one that is not to masters holding whips. . . . Idolatry, too, is a form of enslavement, for when people choose idols that suit their own desires and concerns, they are truly slaves—to their own passions. . . . So the Exodus represented a two-fold liberation: from physical enslavement and from spiritual degradation.” Scherman, ArtScroll Family Haggadah, 10. For scriptural references to the “natural man,” who is ignoble without the purifying, elevating grace of God, see 1 Corinthians 2:11–14; 2 Peter 2:12; Mosiah 3:19; 16:3; and Alma 41:11.

[28] It has been noted especially that Rahab transitions from using the first person plural “us” to noting in verse 11 that “neither did there remain any more courage in any man,” perhaps an observation gained from firsthand knowledge (BT Zevachim 116:b). For a summarized overview of rabbinic commentary about Rahab, see Tamar Kadari, “Rahab: Midrash and Aggadah,” Jewish Women’s Archive, https://

[29] Josephus, The Antiquities of the Jews 5.1.2, https://

[30] BDB, s.v. “זָנָה”.

[31] Indeed, Sinai was always the purpose of their deliverance, as represented by Moses’s initial request of Pharaoh: “The God of the Hebrews hath met with us: let us go, we pray thee, three days’ journey [the distance to Sinai] into the desert, and sacrifice unto the Lord our God” (Exodus 5:3). Interestingly (and intentionally underscored in the text), to “serve” the Lord is the same Hebrew word as to “work” in bondage in Egypt. The vital difference is that service to Pharaoh is compulsory, but the people willingly choose God to be their master and serve him freely. See Jonathan Sacks, Exodus: The Book of Redemption (New Milford, CT: Maggid Books, 2010), 11, 85–86; and Assmann, Invention of Religion, 99 (with related commentary through 106).

[32] See the progression of God’s deliverance in Exodus 6:6–7: first he brings Israel out from under their burdens, then he rids them of bondage, then he redeems them, then he takes them to himself as a people and becomes their God.

[33] For other examples of personal and spiritual deliverance, see Psalm 50:14–23; 56:13; and Job 33:28–30. On how the Exodus came to be seen in a personal light, see George S. Tate, “The Typology of the Exodus Pattern in the Book of Mormon,” in Literature of Belief: Sacred Scripture and Religious Experience, ed. Neal E. Lambert (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1981), 245–62.

[34] On the plainness of Alma, see Alma 13:23 and Alma 14:2.

[35] On rabbinic confidence in Rahab’s full conversion, see Judith Baskin, “The Rabbinic Transformations of Rahab the Harlot,” Notre Dame English Journal 11, no. 2, Judaic Literature: Critical Perspectives (April 1979): 141–57, https://

[36] See BDB s.v. “קרב (II)”.

[37] See Megillah 14b.

[38] Ruth is another example of a foreign woman who integrates into her new community so fully that she is able to marry and bear Jewish children within the royal line.

[39] For a beginning survey of this topic, see Amy Hill Fisher, “The Divine Kinsman: Yahweh and the Tribal Mechanism,” BYU Religious Education Student Symposium (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2010), 141–51.

[40] This is not to say, of course, that God has no familial sentiment or that our spirits have no divine paternity, only that these are not the intent of the narrative in its legally loaded context.

[41] For example, scholars have analyzed Exodus 15—the song of rejoicing after crossing out of Egypt—in terms of Ugaritic and Egyptian influences. See, for example, Joshua Berman, “The Kadesh Inscriptions of Ramesses II and the Exodus Sea Account,” “Did I Not Bring Israel Out of Egypt?”: Biblical, Archaeological, and Egyptological Perspectives on the Exodus Narratives, ed. James K. Hoffmeier, Alan R. Millard, and Gary A. Rendsburg (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2016), 93–111.

[42] I am indebted to Yoram Hazony’s work in Philosophy of Hebrew Scripture (pp. 58–60) for these thoughts, but while Hazony recognizes that the Old Testament has universal, rather than particular, scope like other tribal records, he does so to claim that the Hebrew Bible illustrates a way of life meant as a pattern for the world to follow. I don’t disagree, but my focus, unlike Hazony’s, is on God’s desire to gather even non-Israelites to himself through Israel, with the intention then of blessing them like Israel (as in the right to deliverance).

[43] Henotheism—the worship of one particular god (usually by a family, tribe or nation) without denying the possible existence of other gods—was the standard religious understanding of the ancient Mediterranean world.

[44] For more on covenant adoption as the means by which God’s claim on his believers is enacted, see Levenson, Love of God, 22–23.

[45] See also Romans 8:14; Mosiah 5:7; Doctrine and Covenants 11:30; and Moses 6:68. I have used the word faithful without condition here, but it should be noted that faith in a biblical context implies far more than belief in God’s existence. It is, in fact, a condition of loyalty and faithfulness as fruits of strong trust that God will keep his promises of protection and redeeming obligation.

[46] Hess, Old Testament, 175. The Bible makes clear that the Canaanite threat to Israel was ever their idolatry. Canaan’s worship of human-wrought deities with no power to save threatened to lull the Israelites away from faith in their divine deliverer. See Exodus 34:11–17. For a limited and by no means exhaustive selection of other passages on this theme, see also Numbers 33:51–52, 55; Deuteronomy 7:1–5; 12:2–3; and 2 Kings 23:4–6. Of note, this same idolatry also blinded the Canaanites and prevented them from acknowledging, as Rahab did, the sovereignty of the God who created them. Thus, the book of Joshua depicts iconoclasm, not God’s rejection of other ethnic or national groups as such. Ruth, the Moabite convert from only slightly later in the biblical chronology, is another example of the adoption of the gentile faithful. Jonah’s successful proselytizing to the entire Assyrian city of Nineveh provides additional confirmation of God’s interest in all nations.

[47] Hess, Old Testament, 170, n. 21.

[48] See, for example, “Lecture II: On Repentance and Remission of Sins, and Concerning the Adversary,” The Catechetical Lectures of S. Cyril and “Origen’s Commentary on the Book of Matthew,” XII:4.

[49] See Hebrews 11:31 and James 2:25, as well as “Origen’s Commentary on the Book of Matthew,” XII:4 and Augustine, “Psalm LXXXVII,” Expositions on the Book of Psalms.

[50] “Epistle LXXV: To Magnus, on Baptizing the Novatians, and Those Who Obtain Grace on a Sick-Bed,” The Epistles of Cyprian.

[51] “Treatise I: On the Unity of the Church,” The Treatises of Cyprian.

[52] Given that biblical names often have symbolic resonance, Rahab’s name has undergone much evaluation. Though there have been other interpretations made, this is the one I find by far the most compelling. See Frymer-Kensky, “Reading Rahab,” 67.