Khirbet Beit Lei and the Lehi of Samson

Old Testament and Book of Mormon Considerations, and a Newly Identified Site for Biblical Leḥi and En-hakkore

Jeffrey R. Chadwick

Jeffery R. Chadwick, "Khirbet Beit Lei and the Lehi of Samson: Old Testament and Book of Mormon Considerations, and a Newly Identified Site for Biblical Leḥi and En-hakkore," Religious Educator 23, no. 3 (2022): 64–85.

Jeffrey R. Chadwick (jrchadwick@byu.edu) is Jerusalem Center Professor of Archaeology and Near Eastern Studies and Religious Education Professor of Church History and Doctrine at Brigham Young University. He also serves as senior field archaeologist and director of excavations in several areas of the Tell es-safi/

This is the Refaim Valley today, southwest of Jerusalem, looking down from the heights of Ramath-leḥi.

This is the Refaim Valley today, southwest of Jerusalem, looking down from the heights of Ramath-leḥi.

In the study, appreciation, and teaching of ancient scripture, the disciplines of archaeology, geography, history, and language can often provide helpful and instructive insights for understanding the settings and events of scriptural narratives. The doctrinal and applicative aspects of those narratives may be enhanced by a correct understanding of their ancient backgrounds. But caution must be taken that data and interpretations from these disciplines be used in accurate and responsible ways, and that sensational claims or wishful thinking unsupported by the data not be advanced in our classes nor become part of the teaching experience. A case in point in this regard is an archaeological site in Israel, known in Arabic as Beit Lei and in Hebrew as Beyt Loya. In Latter-day Saint circles many incorrect claims have been made about this site for some fifty years, and some continue to be perpetuated today.

Those claims began in October of 1971 when a young Israeli cultural anthropologist named Joseph Ginat startled the audience at a Brigham Young University academic symposium by declaring that an ancient cave had been excavated in Israel at a place called the “Ruin of the House of Lehi.” [1] The cave, actually a rock-cut tomb from around 700 BC in Iron Age II, had been accidentally discovered in 1961 by Israeli military engineers, who had been constructing a security road along the old border with Jordan west of Hebron, near the abandoned ruins of a medieval Arab village. In Arabic, those desolate village ruins were known as Khirbet Beit Lei. In his presentation, Ginat equated the Arabic term lei with the Hebrew term leḥi.

Archaic Hebrew inscriptions had been discovered incised in the tomb’s soft chalk walls—including a sentence which mentioned Jerusalem (in an old Hebrew form, Yerushalem) and the divine name Yahuweh (Jehovah; see figure 1). Because of these inscriptions, the multichambered burial cave became known among Israelis and academics as the “Jerusalem Cave.” However, after Ginat’s 1971 presentation at BYU, in which he associated the site with the place called Lehi in the biblical story of Samson (see Judges 15:9–19), some Latter-day Saints began calling it the “Lehi Cave.” Encouraged by popular Latter-day Saint author Cleon Skousen, who was very enthusiastic about Ginat’s ideas, some Latter-day Saints began to associate the cave and the name of the nearby medieval Beit Lei ruins with the prophet Lehi of the First Nephi narrative in the Book of Mormon (see 1 Nephi 1:4). [2] They began referring to the site as “Beit Lehi” (House of Lehi) and the “City of Lehi.”

In Arabic the word khirbet means “ruin” and the words Beit Lei are pronounced “bait lay.” The term lei means “twisting.” But Ginat insisted that Arabic lei actually represented the Hebrew proper name Leḥi. [3] Hence he proposed that Khirbet Beit Lei meant “ruin of the house of Lehi.” But this is simply not correct. The Hebrew Bible term leḥi means “jaw” and is pronounced “lekhee” (quite different from Arabic lei, pronounced “lay”). Harvard professor Frank Moore Cross, noted scholar of Near Eastern languages, explained that Arabic lei and Hebrew leḥi are not the same in meaning, pronunciation, or spelling, and that no linguist would confuse the two, any more than one could confuse the familiar English names Lee and Locke. [4]

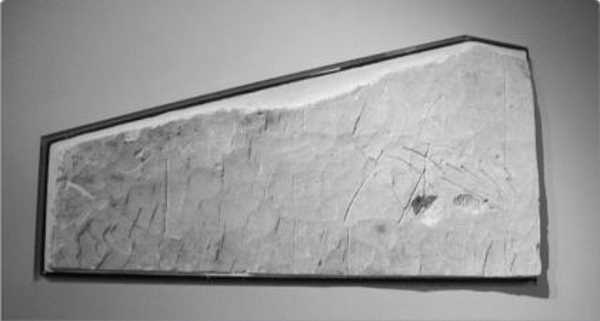

Figure 1—Limestone segment of the wall of the Jerusalem Cave bearing etchings and inscriptions, on display at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. The name Jerusalem (Yerushalem) appears in archaic Hebrew, enhanced in white, at upper center-left in the stone segment. Photo by Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2012.

Figure 1—Limestone segment of the wall of the Jerusalem Cave bearing etchings and inscriptions, on display at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. The name Jerusalem (Yerushalem) appears in archaic Hebrew, enhanced in white, at upper center-left in the stone segment. Photo by Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2012.

In the present study I will reexamine the claims of Ginat and others, with particular emphasis on the personal and place name Leḥi and on the location of the Leḥi of Samson in the biblical narrative. This article represents an update on my original evaluation of numerous “Beit Lehi” claims, which was published previously in The Religious Educator in 2009 as “Khirbet Beit Lei and the Book of Mormon: An Archaeologist’s Evaluation.” [5] That study included detailed diagrams, drawings, and photos of the burial cave and its inscriptions and illustrations, as well as a thorough explanation of the archaeology of the village ruins—information that would be helpful reading in connection with this present study, since the detailed background and history of all claims about the “Lehi Cave,” the “House of Lehi,” and the “City of Lehi” will not be repeated here. Instead, the present article will proceed in two components: (1) an update on the Beit Lei site itself, discussing excavation at the site up to the present, as well as approaches now taken in media and conversation by “Beit Lehi” advocates; and (2) a discussion of claims that link the Beit Lei site to the place named Leḥi in the story of Samson found in the Old Testament book of Judges, explaining why the Leḥi of Samson cannot have been the place that Beit Lei enthusiasts continue to call “Beit Lehi.” In this discussion, a newly discovered potential site in Israel for the Leḥi of the Samson story will be revealed.

A 2022 update and the “Beit Lehi Regional Project”

Although periodic excavations have continued at Khirbet Beit Lei until the present, the basic understanding of the archaeology of the site (see figure 2) has not changed significantly since 2009. That year, in addition to my own study in The Religious Educator, a succinct preliminary report on the archaeology of the site, complete with plans and color photos, was published by its excavator, Dr. Oren Gutfeld. [6] Gutfeld is a highly respected and competent Israeli archaeologist. In his report, he outlined the finds and stratigraphy of the settlement in various periods of occupation. Gutfeld’s publication identified three basic strata at the Beit Lei site, which are listed below (with approximate dates and main features added in parentheses):

Stratum I—the Mamluk period (a medieval Arab village, dating to ca. AD 1200–1400)

Stratum II—the Byzantine–early Islamic period (the Christian chapel, ca. AD 400–800)

Stratum III—the Hellenistic period (Idumean agricultural facilities, ca. 300–160 BC)

and early Roman period (Jewish agricultural facilities, ca. 30 BC–AD 70)

While the Iron Age II rock-cut tomb known as the Jerusalem Cave (or so-called “Lehi Cave”) is located about 100 meters away from the Khirbet Beit Lei site, no Iron Age structures or strata have been found by the excavators at the unrelated village site itself. There is not an Iron Age stratum at Khirbet Beit Lei, nor is there Iron Age architecture of any kind. As noted in my 2009 study, no Iron Age settlement existed at Beit Lei, not around 600 BC nor at any other point in Iron Age I (1200–1000 BC) or Iron Age II (1000–586 BC). [7] The site of the medieval village was neither settled nor otherwise materially occupied throughout the entire Iron Age. [8] Therefore, it cannot have been a “City of Lehi” or a “Beit Lehi” residence or estate belonging to the prophet Lehi in the First Nephi narrative of the Book of Mormon, who lived at Jerusalem just prior to 600 BC.

In 2017, Gutfeld expanded his investigations in the Beit Lei area by initiating the “Beit Lehi Regional Project” with the goal of exploring and excavating sites in the region round about Khirbet Beit Lei (Beyt Loya). The region involved is a 22-square-kilometer (8.5-square-mile) area bounded by Tel Maresha on the north, Nahal Maresha on the west, Tel Amazya on the south, and the Green Line (the pre-1967 Israeli border) on the east. The first significant site identified and excavated in this expansion of the “Beit Lehi” project was Ḥorbat ‘Ammuda, located about 850 meters north of Beyt Loya. (The term ḥorbat in Hebrew is the equivalent of khirbet in Arabic—both terms mean “ruin,” as in the ruins of ancient or antique structures.)

An area of around 100 square meters has been excavated at Ḥorbat ‘Ammuda since 2017, revealing remains of a large building some 57 x 75 meters in size. The structure featured well-built stone walls; it appears to have been an Idumean administrative center. Certain rooms that functioned as cultic or templelike facilities were found within the structure, and they yielded several fascinating cultic objects. Three phases of the building’s use were discerned, dating between about 330 and 160 BC, spanning both the Ptolemaic and Seleucid periods of control over the region during the Hellenistic period. The structure is posited to have been an Idumean operations center in the region prior to the Hasmonean revolt, which saw Judea gain control of the area after 165 BC. The building was destroyed around 160 BC, probably by Hasmonean Jewish forces. Like Beit Lei, no Iron Age strata or structures have yet been identified at ‘Ammuda. A concise preliminary report on the first three seasons (2017–2019) of excavation at ‘Ammuda, complete with plans and color photos, has now been prepared and published by Gutfeld. [9]

In both of the Gutfeld publications I have mentioned, the site of Khirbet Beit Lei is consistently referred to by himself and his coauthors as “Bet Loya” (rendered herein with the fuller transliteration Beyt Loya). The site is never referred to as “Beit Lehi” in Israeli archeological publications. However, the term “Beit Lehi” does appear in Gutfeld’s reports when referring to the Beit Lehi Foundation, a Utah-based nonprofit corporation which supports the work at Beyt Loya with funding and volunteer excavators. Gutfeld also uses “Beit Lehi” when referring to the recently launched “Beit Lehi Regional Project,” likewise significantly funded by the Beit Lehi Foundation. Additionally, when presenting his research to English-speaking Latter-day Saint audiences in the United States and Utah, he does freely use the term “Beit Lehi” when referring to Beyt Loya. The Beit Lehi Foundation website (beitlehi.org) acknowledges the funding and support it gives to Gutfeld’s excavation projects at the site they continue to call “Beit Lehi.” [10]

Recently, Gutfeld and the Beit Lehi Foundation expanded use of the term “Beit Lehi” beyond the limits of the small site at Khirbet Beit Lei (Beyt Loya) to include the nearby Iron Age II burial cave (the Jerusalem Cave or so-called “Lehi Cave”) and the areas excavated or slated for exploration in the 22-square-km area surrounding Beyt Loya. This now includes Ḥorbat ‘Ammuda, which they have begun referring to as being in the greater “Beit Lehi” region. From this notion comes the term “Beit Lehi Regional Project,” mentioned above. This expansion effectively allows the Beit Lehi Foundation not only to claim that “Beit Lehi” has remains which date to Iron Age II (the burial cave near the Arab village remains), but also to anticipate that Iron Age II remains will eventually be found in the greater region beyond Khirbet Beit Lei. This would be a key issue in any unstated hope that the prophet Lehi of Jerusalem in the First Nephi narrative was somehow connected to the site. While Gutfeld has made no mention of Iron Age II finds in any of his Israel Antiquities Authority publications, the current Beit Lehi Foundation website includes Iron Age II in its “History of Beit Lehi” description, creatively suggesting that settlement at Beyt Loya began around 800 BC. [11]

I conclude this update by noting significant differences in the website and other promotional materials produced by the Beit Lehi Foundation since the appearance of my original study in 2009. From the initial announcement of a “House of Lehi” by Joseph Ginat in 1971 all the way down to 2008, print publications and video presentations about Khirbet Beit Lei produced by “Beit Lehi” advocates were quite open and forward about linking the site to the prophet Lehi of Jerusalem, positively suggesting that the location was his property and that he had even lived there. After 2009, however, when publications by myself and Gutfeld first appeared, such open suggestions disappeared from the literature and media produced by those interested in the site, and most notably in material from the Beit Lehi Foundation. The old website of the foundation (beitlehifoundation.org) with its numerous references to the Book of Mormon and the prophet Lehi has been deactivated. And the current website of the foundation (beitlehi.org) contains no reference to the Book of Mormon or its prophet Lehi, even making the progressive leap of noting that “Beit Lehi” is called Beyt Loya by Israelis. This progress in sticking to the facts is noteworthy, and it shows a positive development in their approach to dealing with this significant archaeological site of the Hellenistic and Roman periods.

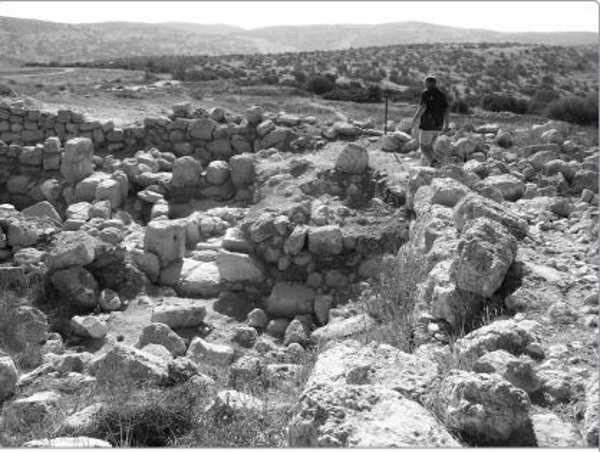

Figure 2—Mixed ruins on surface from the Mamluk period (AD 1200–1400) and the early Roman period (50 BC–AD 70) at Khirbet Beit Lei, also known in Hebrew as Beyt Loya. Photo by Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2008.

Figure 2—Mixed ruins on surface from the Mamluk period (AD 1200–1400) and the early Roman period (50 BC–AD 70) at Khirbet Beit Lei, also known in Hebrew as Beyt Loya. Photo by Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2008.

Despite these positive developments, legitimate questions remain from the continued use of the term “Beit Lehi.” Any observer could reasonably ask whether the original assumption dating back to the days of Ginat, Skousen, and the earliest “Beit Lehi” advocates—that the Beyt Loya site was somehow associated with the prophet Lehi of Jerusalem around 600 BC—has really been abandoned, or whether it in fact remains a powerful underlying expectation. The disclaimer that was added to the Beit Lehi Foundation’s website in 2022 reads as follows: “Archaeologists have yet to discover that the site of the Beit Lehi Regional Project was the home of any prophet named Lehi. Bedouin tradition purports to claim such but the Beit Lehi Foundation makes no such claim until substantiated by archaeological discovery.” [12] But there are no trained and degreed archaeologists of whom I am aware who are attempting or have claimed they are attempting to discover if the Beyt Loya region was the home of the Book of Mormon prophet Lehi. Additionally, as was shown in the 2009 study, there was never any Bedouin tradition suggesting that a prophet named Lehi lived in the area anciently. [13] With these facts in mind, should the name “Lehi” continue to be used in connection with Beyt Loya?

The “Leḥi” of the Samson narrative in the book of Judges

A key claim of Joseph Ginat and those Latter-day Saints who suggested that Khirbet Beit Lei had been a “City of Lehi” or “Beit Lehi” was the idea that the Arabic toponym Beit Lei preserved the biblical Hebrew place name “Lehi” from the account of Samson in the Old Testament (see Judges 15:9–19). The King James Version Bible spelling of “Lehi” represents the biblical Hebrew term לחי (pronounced “lĕkhee”), which is usually rendered phonetically in English as Leḥi (with a dot under the “ḥ” representing the harder “kh” consonant sound as opposed to the normal soft “h” sound in English). The generic Hebrew term leḥi means “jaw,” and by extension “jawbone,” and this is important to remember in reading the story of Samson’s single-handed battle against a company of Philistine warriors in Judges 15. A brief review of that story, and the background and setting of Samson’s life prior to it, will be helpful at this point.

Samson was born into the Israelite tribe of Dan in the town known as Zorah (Hebrew Tzorah), which was located just over 20 km (13 miles) straight west of Jerusalem (see figure 3). As described in Joshua 19, Zorah was one of the cities clustered in the eastern limits of Dan’s land allotment, along with Eshtaol and Ir Shemesh (also known in the Bible as Beth Shemesh and in modern Israeli usage as Beit Shemesh; [14] see Joshua 19:40–48, especially verse 41; see figure 3). While it is difficult to pinpoint events chronologically in the book of Judges, it is likely that Samson was born around 1100 BC and grew up in the eleventh century BC, during the time when the Philistines had begun trying to expand their own territory from the coastal plain of Canaan eastward into Israelite territory. The text notes that Samson grew up and was active “in the camp of Dan between Zorah and Eshtaol” (Judges 13:25).

Virtually all events of Samson’s life that are described in Judges 14–15 took place in the territory of Dan along the Sorek Valley, which winds east to west from the area of Zorah and Beth Shemesh to the Philistine towns of Timnath and Ekron (see figure 3). Those events include Samson’s marriage to a Philistine woman from Timnath (Judges 14:1–5), his killing of a lion (Judges 14:8–9), and his enigmatic riddle about eating honey from the lion’s carcass (Judges 14:10–18). He only left the Sorek region briefly to go to Ashkelon, where he carried out a deadly solution to pay off the bet he lost over his riddle (Judges 14:19). With the failure of his marriage, Samson took revenge against the Philistines of Timnath by tying torches to the tails of foxes and turning them loose in the grain fields and grape vineyards of the Philistines in the western Sorek, destroying a significant part of the Philistines’ food supply. The Philistines responded by killing Samson’s by-then-estranged wife and her family (Judges 15:1–7). Samson retaliated for this by killing many Philistines “with a great slaughter” (Judges 15:8). It is at this point that the narrative introduces the location known as Leḥi.

Samson fled from the Sorek area eastward up into the territory of Judah, and hid in a remote cave, a rock cavity called the “cleft of the rock Etam” (Judges 15:8, NKJV). The King James Version oddly renders the name of this place as “top of the rock Etam,” but the Hebrew phrase in this verse, סעיף סלע עיתם (sif sela etam), is more accurately rendered as “cleft of the rock of Etam” [15] in most modern English translations. [16] This seems to have been a natural cleft cavern in a bedrock formation at or near the biblical site Etam. The location of biblical Etam in the tribal area of Judah is noted in Second Chronicles as being in the vicinity of Bethlehem (see 2 Chronicles 11:6), which was just 8 km (5 mi) south of Jerusalem. Modern biblical geographers almost universally locate Etam at Khirbet el-Khokh, which is southwest of Jerusalem and northwest of Bethlehem, as well as somewhat south of the Refaim (רפים; pronounced rĕ-fâ-yim) Valley (see figure 3). [17] The name Etam is remembered in the Arabic toponym ‘Ain ‘Atan, a spring located at el-Khokh. [18]

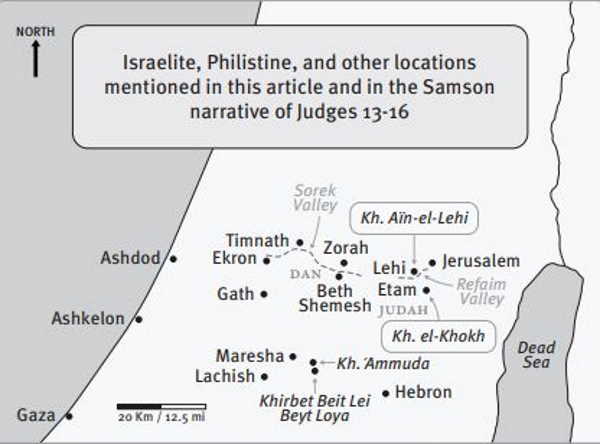

Figure 3—Map of the central part of Israel, with sites marked along the Sorek Valley where the narrative of Samson is set. East of the Sorek Valley, in the Refaim Valley, is the site of Khirbet ‘Aïn-el-Lehi, the proposed location of Leḥi in the Samson narrative (Ramath-leḥi and En-hakkore). Also marked are sites well south of the Sorek between Lachish and Hebron, including Khirbet Beit Lei (Beyt Loya) and other cities of the Philistine Pentapolis. Map by Jeffrey R. Chadwick. [On this map Kh. = Khirbet.]

Figure 3—Map of the central part of Israel, with sites marked along the Sorek Valley where the narrative of Samson is set. East of the Sorek Valley, in the Refaim Valley, is the site of Khirbet ‘Aïn-el-Lehi, the proposed location of Leḥi in the Samson narrative (Ramath-leḥi and En-hakkore). Also marked are sites well south of the Sorek between Lachish and Hebron, including Khirbet Beit Lei (Beyt Loya) and other cities of the Philistine Pentapolis. Map by Jeffrey R. Chadwick. [On this map Kh. = Khirbet.]

A company of Philistine warriors followed Samson up into Judah and established a camp at a location near Etam—a place called Leḥi (Hebrew לחי), the King James Version’s “Lehi” (Judges 15:9). Certain Israelites of Judah went to Samson’s hiding place and negotiated with him to surrender to the Philistines, which he agreed to do (see Judges 15:10–14). Upon being taken by the Judahites to the Philistines encamped at nearby Leḥi, Samson again went into action. The place of Samson’s battle is noted as “Ramath-leḥi” (לחי רמת), which means “the height” or “high place” of Leḥi. The terrain at Leḥi was high, and therefore it had a steep hillside. Having no sword, Samson utilized the large, hard jawbone (the leḥi!) of a dead donkey he found lying about, which became a jagged, deadly club in his hands. Taking on the Philistine company, Samson “slew a thousand men” with the lethal leḥi weapon, perhaps one or two at a time as he moved from defensive spot to defensive spot on the steep hillside (Judges 15:15). Whether the word thousand is to be taken literally here, or whether it is a hyperbolic expression for the large number of Philistine warriors Samson dispatched, is of little importance; in either case, the outnumbered Israelite triumphed over a significant company of men sent to capture or kill him, sending all or most of them to their deaths instead.

The narrative in Judges 15 attributes the naming of the Leḥi site to Samson’s own declaration: “he cast away the jawbone [leḥi] out of his hand, and called that place Ramath-lehi” (Judges 15:17). Overwhelmed with thirst after the protracted battle, Samson cried out to God for water, and “God clave an hollow place that was in the jaw”—that is, at Leḥi—“and when [Samson] had drunk, his spirit came again, and he was revived: wherefore he called the name thereof En-hakkore” (Hebrew הקורא עין; Judges 15:18–19). The term hakkore (הקורא) means “he who cries out.” The term en (עין) means a spring of water. The term is normally rendered ein in modern English spelling, but appears as en in the King James Version (ein is normally pronounced “ine” unless connected to a following term, in which case it is pronounced “en” or “ane”). The text summarizes the geographical location of Samson’s victory by saying that “En-hakkore . . . is in Lehi unto this day” (Judges 15:19). In other words, the spring from which Samson drank was known by the biblical writer, who lived centuries later, to be at the height Samson called Leḥi (jawbone), which was in reasonably close proximity to the vicinity of Etam.

The systematic geography of the biblical account in Judges is very easy to follow. It clearly places the Leḥi of the Samson story in the region east of the Sorek Valley, over the border between Dan and Judah into the Judean hills, not very far from the location of biblical Etam, which itself was in the Bethlehem region. This geography cannot be reconciled with the claims made by “Beit Lehi” advocates that the Leḥi of Samson was at Khirbet Beit Lei, which is over 25 km (15 mi) south of the Sorek Valley and two Shfela valley systems away. One would have to travel south from the Sorek Valley over the Shfela hills of Judah, passing over the Elah Valley, and then over more hills passing the Guvrin Valley, in order to get to the region of Khirbet Beit Lei. As I explained in my previously mentioned 2009 article, “a serious study and reconsideration of the biblical text and the systematic historical geography of the Samson story is warranted” for anyone who maintains the idea that Beit Lei could be the Leḥi of Samson. [19]

Additionally, as already observed, the Arabic term Beit Lei (بيت ليّ) is pronounced “bait lay,” and lei (ليّ) means “twisting” in Arabic, not “jawbone.” It is simply incorrect to maintain that Arabic lei somehow equates to Hebrew leḥi. There is no way, in terms of both place name translations and location factors, that Beit Lei could be the Leḥi of Samson or have anything to do with the Samson story. Furthermore, the Roman-period well close to Khirbet Beit Lei, which is called “Samson’s Well” on the Beit Lehi Foundation website, [20] is not a spring, nor is it in any proximity to the Leḥi of Samson. It cannot have been “En-hakkore,” the spring of the Samson story (Judges 15:19). The claims made by “Beit Lehi” advocates regarding Samson’s connections to Beyt Loya are demonstrably incorrect. For these reasons, use of the fictitious term “Beit Lehi” for the Beyt Loya site and the region surrounding it (including the impressive site at ‘Ammuda) is misleading and should be discontinued.

A recently rediscovered candidate for the site of Samson’s Leḥi

With all of the above in mind, it is fair to ask the question: Where then is the Leḥi of Samson and the spring that he named? Until recently, there has been no satisfactory answer to this query. Modern scholarship has failed to identify a site east of the Sorek Valley that would fit the systematic detail presented in the Samson narrative. Scholars have been unable to use any linguistic, toponymic, or geographic set of clues to identify the biblical location of Leḥi—that is, until now.

In 2017 Dr. Chris McKinny, a talented archaeologist and historical geographer of the rising generation of biblical scholarship (as well as a longtime colleague), published a short article in the online version of the Encyclopedia of the Bible and Its Reception (EBR). In it, he located the Leḥi of the Samson narrative in the Refaim Valley, which is east of the Sorek region and not far from Jerusalem, in the vicinity of a spring known as ‘Ain Hanniyeh. [21] McKinny also followed up with a longer academic article that was published in the academic journal Archaeology and Text in 2018. [22] In that study he more precisely located the site of Leḥi itself slightly north of ‘Ain Hanniyeh at a place that was still known in Arabic in the late 1800s as ‘Aïn-el-Lehi. The name ‘Aïn-el-Lehi remarkably preserves the biblical toponym Leḥi, but it does not appear on any modern Israeli maps of the Refaim Valley today.

McKinny rediscovered the old Arabic reference to ‘Aïn-el-Lehi while researching the work on nineteenth-century Palestine prepared by French explorer Victor Guérin (1821–1891), who travelled to the Holy Land eight times between 1852 and 1888, preparing carefully written studies and remarkably detailed maps of sites he visited, researched, and surveyed. [23] Guérin proposed numerous identifications of biblical sites from his on-the-ground explorations, from his understanding of the Bible’s history and geography, and from interviews with the local Arab population about place names and traditions. His 1881 map of Palestine is a remarkable treasure of carefully plotted and notated sites, the Arabic names of which sometimes preserve biblical Hebrew recollections. A portion of the map, showing the site of unexcavated ruins and a spring in the heights above the Refaim Valley west–southwest of Jerusalem, reveals the Arabic name Kh. aïn-el-Lehi for the location of the heights, the ruins, and the spring. On his map, Guérin himself added the biblical toponym “Ramath Lehi” for the site (see figure 4). [24]

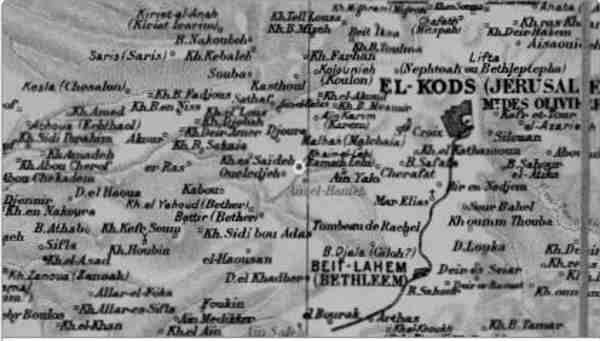

Figure 4—A portion of the 1881 map of Palestine by Victor Guérin, showing the region from Jerusalem westward. The site of Khirbet aïn-el-Lehi is seen with a superimposed red circle around it in the center of this visual, located on the north side of the Refaim Valley and west–southwest of Jerusalem (EL-KODS on the map).

Figure 4—A portion of the 1881 map of Palestine by Victor Guérin, showing the region from Jerusalem westward. The site of Khirbet aïn-el-Lehi is seen with a superimposed red circle around it in the center of this visual, located on the north side of the Refaim Valley and west–southwest of Jerusalem (EL-KODS on the map).

In his published description of the ‘Aïn-el-Lehi site, which covered four pages in his second volume on Judea as part of his comprehensive series Description géographique, historique, et archéologique de la Palestine (Paris, 1869), Guérin used the unabbreviated version of Arabic khirbeh in referring to the site as “Khirbet A’ïn-el-Lehi,” followed by the Arabic alphabet version خر بۿ عين اللحى which he clarified with a diacritical mark above the “h” as اللخى (el-Leḥi) to portray the harder “ḥ” sound. He represented the pronunciation of the name as “el-Lekhi” in his French text. [25] This name, pronunciation, and spelling for the locale was based on his conversation with local Arab men, who explained that the site was the ruin of an ancient village called el-Lekhi (see figure 5). Guérin’s Arabic spelling of the name precisely parallels the Hebrew spelling of Leḥi (לחי) in its use of the hard “ḥ” (Hebrew ח; pronounced khet).

A key factor in support of the ‘Aïn-el-Lehi site as the Leḥi of Samson is that it is located just 6 km (3.7 mi) from Khirbet el-Khokh (see figures 3 and 4; note that Guérin spells the place el-Khoukh). As noted above, el-Khokh is identified by most historical geographers as the site of biblical Etam. The “rock of Etam,” also mentioned above and in the Samson narrative (Judges 15:8), was outside the settlement and was about 5 km (3.1 mi) southeast of ‘Aïn-el-Lehi. In the systematic geography of the Samson narrative, Leḥi seems located in the near vicinity of the “rock of Etam.” The close proximity of Khirbet el-Khokh to Khirbet ‘Aïn-el-Lehi fits the geographic requirements of the Samson narrative quite well.

Two other factors connect the report of Samson’s battle at Leḥi to the ‘Aïn-el-Lehi site. The first is that ‘Aïn-el-Lehi is located on the slope of the mountain heights called Rekes Lavan (the “White Ridge”), which rise up directly from the Refaim Valley, north of ‘Ain Hanniyeh and south of Ein Kerem. The biblical narrative requires an elevated location—a ramah (רמה)—for Samson’s battle at “Ramath-lehi” (Judges 15:17). The term “ramath” in this passage (ramat; רמת) is the construct form of ramah; the two are the same word. And the ‘Aïn-el-Lehi site, which Guérin called el-Lekhi, is definitively a ramah.

The second indicator is that while the Refaim Valley bears a different name than the Sorek Valley of Samson’s home territory, it is actually the eastward extension of the Sorek Valley, ascending from the hills of the Shfela right up to Jerusalem. The two are the same valley system. Indeed, the old train line which runs from Jerusalem down to the coast passes west out of the city, following the Refaim Valley until it becomes the Sorek Valley, and continues all the way to the coastal plain. The entire narrative of Judges 14–15 plays out from its centrality in the Sorek, thus the ‘Aïn-el-Lehi site, located just east of where the Sorek Valley becomes the Refaim Valley, fits the geographical setting of Samson’s battle narrative quite precisely.

Figure 5—Pages 396–97 of Victor Guérin’s Description géographique, historique, et archéologique de la Palestine, vol. 2, in which the site of Khirbet ‘Aïn-el-Lehi (el-Lekhi) is discussed. [26] Public Domain.

Figure 5—Pages 396–97 of Victor Guérin’s Description géographique, historique, et archéologique de la Palestine, vol. 2, in which the site of Khirbet ‘Aïn-el-Lehi (el-Lekhi) is discussed. [26] Public Domain.

Leḥi in the report of Shammah

It is also of note that the Samson narrative is not the only instance in the Old Testament of Philistine forces invading Judah via the Refaim Valley. During David’s reign in the early tenth century BC, several decades after Samson’s era, “a troop of the Philistines pitched in the valley of Rephaim” while “the garrison of the Philistines was then in Beth-lehem” (2 Samuel 23:13–14). Despite the older King James Version spelling, which utilizes “ph” for the “f” sound, this is the same Refaim Valley, located just southwest of Jerusalem and northwest of Bethlehem, spoken of throughout this article (see figures 3 and 4). Although the King James Version does not reveal it, in this passage the Hebrew Bible text notes that Philistines had gathered at the site known as Leḥi and were defeated there by “Shammah the son of Agee” (vv. 11–12), one of David’s “mighty men” (v. 8). The King James Version also does not properly translate the name Leḥi in verse 11, incorrectly rendering it as “troop.” The Hebrew term in verse 11 is לחיה (leḥiah), which does not refer to a troop; instead, it is a grammatical combination attaching the locational preposition ah to the place name Leḥi. Literally, leḥiah would mean “toward (the place) Lehi,” and the translation of the phrase in verse 11 would read “the Philistines gathered toward Lehi.” Older translations such as the King James Version, which is reliant on medieval vowel points in the Hebrew text and unfamiliar or unconcerned with the geographical setting of the biblical stories, do not recognize the place name Leḥi in this passage; however, many recent translations do properly translate this section. For example, in the Revised Standard Version (RSV) we see the following: “The Philistines gathered together at Lehi, where there was a plot of ground full of lentils” (2 Samuel 23:11, RSV). [27] The place Leḥi is noted in 2 Samuel 23 as being in the proximity of both Bethlehem and the Refaim Valley, lending significant credibility to our location of the Leḥi of Samson in that same area.

In his 2018 article, McKinny followed Guérin in identifying the ‘Aïn-el-Lehi site on the north slope of the Refaim Valley as the location of biblical Leḥi in both the Samson narrative (see Judges 15:9–20) and the Shammah narrative (see 2 Samuel 23:11–14), presenting a compelling case for the identification based on both the preserved reference to Leḥi in the Arabic toponym and the systematic geography of the narrative. [28] For Samson’s spring of “En-hakkore,” McKinny suggested the spring ‘Ain Hanniyeh, on the south side of the Refaim Valley, as the waters that quenched Samson’s thirst (Judges 15:18–19; see figures 4 and 5, where Guérin spelled it Aïn-el-Hanieh). At the time he published his proposals, however, he had not visited these sites. Intrigued by his studies, I proposed to him that we attempt to visit the site together. However, conflicting schedules in 2019 delayed our plans, and the COVID-19 pandemic prevented both of us from travelling to Israel in 2020. In June of 2021, though many pandemic restrictions were still in place, I was granted a special permit to enter Israel for continued excavation work at Gath (the ancient Philistine capital). On that journey I also made the attempt to find the ‘Aïn-el-Lehi site.

Because the name ‘Aïn-el-Lehi does not appear on modern maps in Hebrew, Arabic, or English, I assumed it would be difficult to locate and that I might have to do some hiking and exploration in the wild. Triangulating from other sites on Guérin’s map that are well known today, including Ein Kerem and Malcha (Ain Karim and Malhah on the Guérin map), I succeeded in finding the location much more quickly and easily than anticipated.

‘Aïn-el-Lehi is located directly west of modern Jerusalem’s popular Biblical Zoo (also known as the Tisch Family Zoological Gardens). A narrow gravel road travels 2 km westward from the zoo to the ‘Aïn-el-Lehi site, which has been developed into an attractive forest picnic area in the Refaim Valley National Park. The site is now called Ein Lavan, modern Hebrew for “White Spring.” The name is derived from the “White Ridge” heights (Rekes Lavan) that loom above the spring and park (see figure 6). The name Ein Lavan was given to the location and spring after 1948, when Israel became a state and the area fell within its boundaries. No Israelis were aware of the older Arabic name at that time.

Figure 6—The site of ‘Aïn-el-Lehi at the Ein Lavan park in the Refaim National Park just outside Jerusalem. The lower of two pools fed by the site’s spring is seen beneath the eastern heights of the Rekes Lavan ridge. The ridge is proposed as Ramath-leḥi of the Samson narrative, and the spring as Samson’s En-hakkore. Photo by Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2021.

The Ein Lavan site sits well above the Refaim Valley but below the impressive heights of the mountain ridge. It boasts a copious perennial spring called Ein Lavan that feeds two old stone-lined pools. These pools have been reconstructed for wading, making the park a popular picnic getaway in warmer weather. The Rekes Lavan heights rise above the spring and pools, wrapping around the site on the west, north, and east. Just west of the spring-fed pools are the unexcavated remains of an old settlement, its date not yet known. These would be the khirbe or ruins of the old Arabic toponym Khirbet ‘Aïn-el-Lehi, which appears in Guérin’s report. I explored the site and its heights, reading the narrative of Samson at Leḥi while there, and I could see that the dynamics of the story and Samson’s battle fit the landscape perfectly. The account even notes that a “hollow place” (Hebrew maktesh, מכתש—a crater which served as a collection pool) was present “in the jaw” (Hebrew—“at Leḥi”), into which the water of the spring En-hakkore collected, and from which Samson drank (Judges 15:19). I thought immediately that the Ein Lavan or ‘Aïn-el-Lehi spring, located right there on site, must have been Samson’s En-hakkore.

In May of 2022 I visited Ein Lavan again, this time together with my colleague Dr. McKinny, who saw the location of his impressive research for the first time. After exploring the site together and viewing the spring and two pools, the surrounding heights, and the nearby settlement ruins, we both agreed that this site must be the Leḥi of the Samson narrative (see Judges 15:9–19) and of the Shammah narrative (see 2 Samuel 11–14). It follows that the heights of the Rekes Lavan ridge must be the Ramath-leḥi where Samson prevailed in battle over the Philistine force sent to capture him (see Judges 15:17). McKinny also agreed that the spring Ein Lavan—the ‘Aïn-el-Lehi of Guérin’s report and map—must be Samson’s En-hakkore rather than the 'Ain Hanniyeh spring across the valley to the south, which he had suggested as Samson’s spring in 2018. [29] We are now planning joint academic and popular publications on these new identifications and are considering suggesting to the Israel Nature and Parks Authority that the site be noted and perhaps even renamed for its connection to the Samson and Shammah stories in the Old Testament.

Conclusions

Two conclusions present themselves quite obviously as this article is brought to a close. They may be stated quite briefly. The first, of course, is that the site of Beyt Loya, east of Lachish in the southern Shfela region of Israel, cannot in any way be reconciled to the contextual geography of the Samson narrative in Judges 15. Nor does the old Arabic toponym Beit Lei in any way preserve the biblical name Leḥi. There is no linguistic, geographical, historical, or archaeological evidence connecting Khirbet Beit Lei or any of the region surrounding the site to the Samson story; it cannot have been the Leḥi of Samson. There was no “Beit Lehi” or “House of Lehi” in that area. By extension, the site and region cannot have been the source for the name of Lehi of Jerusalem, the patriarchal prophet from the First Nephi narrative.

Figure 7—Dr. Chris McKinny (left) and the author stand by the larger upper pool fed by the ‘Aïn-el-Lehi spring at the Ein Lavan park in the Refaim National Park just outside Jerusalem. At left the Rekes Lavan rises to the north, and at right the eastern height of the ridge is proposed as Samson’s Ramath-leḥi. This pool is reminiscent of the “hollow place” God “clave” for the water which Samson drank at Leḥi (Judges 15:18). Photo by Jeffrey R. Chadwick, 2022.

The second conclusion is that a remarkable new candidate for an Old Testament site of some significance—the Leḥi of the Samson and Shammah stories—may now be identified with considerable confidence at the Ein Lavan park just outside modern Jerusalem. The old Arabic name for this site and spring—‘Aïn-el-Lehi—precisely preserves the biblical Hebrew toponym Leḥi, and the systematic geography of the Samson narrative in Judges 15 also precisely fits the Refaim Valley location of the site. Rediscovery of this site’s connection to the Samson story will be a significant contribution to the study and appreciation of the Old Testament.

Notes

[1] Joseph Ginat, “The Cave at Khirbet Beit Lei,” Newsletter and Proceedings of the SEHA, no. 129 (April 1972): 1–5. The paper was read at the Twenty-First Annual Symposium on the Archaeology of the Scriptures, held at Brigham Young University on October 16, 1971. The symposium was a function of the Society for Early Historic Archaeology (S.E.H.A.), an adjunct association at BYU. In 1979 the S.E.H.A. became independent of BYU, and by 1990 it had ceased operations. Ginat’s 1972 publication may be accessed in PDF format at the following link: https://

[2] Jeffrey R. Chadwick, “Khirbet Beit Lei and the Book of Mormon: An Archaeologist’s Evaluation,” The Religious Educator 10, no. 3 (2009): 19–21, https://

[3] Ginat, “Cave at Khirbet Beit Lei,” 3–4.

[4] Cross, quoted in “Was BAR an Accessory to Highway Robbery?,” Hershel Shanks, Biblical Archaeology Review, November/

[5] Some background to that study will be helpful. In 2008 I was approached by the publication directors of both the BYU Religious Studies Center and the Neal A. Maxwell Institute at BYU. The directors requested that I revisit both Khirbet Beit Lei and the Jerusalem Cave in Israel and reevaluate the “Lehi Cave” and “House of Lehi” claims that had become so widely circulated among Latter-day Saints. I revisited both sites that year, with a personal tour of Beit Lei conducted by a senior staff member of the excavation team, and then prepared the requested study. See Chadwick, “Khirbet Beit Lei and the Book of Mormon.”

[6] Oren Gutfeld, “Horbat Bet Loya,” Hadashot Arkheologiyot—Excavations and Surveys in Israel 121 (2009): 344–49, http://

[7] Chadwick, “Khirbet Beit Lei and the Book of Mormon,” 37–38.

[8] In “Khirbet Beit Lei and the Book of Mormon” (2009), I reported that not a single sherd of Iron Age pottery had been found at the site. In 2017 Beyt Loya’s excavator, Oren Gutfeld, kindly contacted me with an update that a few Iron Age sherds (less than ten) had been found in a filling action for a Stratum III structure. He shared a photo of the sherds with me, and I agreed that they were indeed Iron Age sherds. It is not unexpected that stray Iron Age sherds would appear in such a context, especially considering that an Iron Age II tomb is located 100 meters from the site. There may be additional Iron Age II tombs in the area that have not yet been discovered. Still, no evidence of underlying Iron Age structures (or even of an Iron Age–use stratum) has materialized at Khirbet Beit Lei.

[9] Oren Gutfeld et al., “Horbat ‘Ammuda,” Hadashot Arkheologiyot—Excavations and Surveys in Israel 133 (2021), https://

[10] Beit Lehi Foundation website, https://

[11] See “Introduction,” Beit Lehi Foundation, accessed August 16, 2022, https://

[12] Beit Lehi Foundation homepage, “Disclaimer,” at bottom of page, accessed August 16, 2022, https://

[13] Chadwick, “Khirbet Beit Lei and the Book of Mormon,” 21.

[14] In this paper, the city called ‘Ir Shemesh’ in Joshua 19 will be referred to as Beth Shemesh, its more frequently used biblical and modern name.

[15] A sif or cleft is a narrow, often deep, cavity. Readers may be interested to know that it is also entirely plausible that sif sela (סעיף סלע) was the Hebrew term behind the English-translated phrase “cavity of a rock” in Nephi’s account of hiding from pursuers sent by Laban (1 Nephi 3:27); see Chadwick, “Khirbet Beit Lei and the Book of Mormon,” 40.

[16] For other translations of סעיף סלע עיתם (sif sela etam) as “cleft of the rock of Etam,” see Judges 15:8–10 in the NKJV (New King James Version), in the RSV (Revised Standard Version), in the NRSV (New Revised Standard Version), in the ASV (American Standard Version), and in the NASV (New American Standard Version).

[17] See Yohanan Aharoni et al., The Carta Bible Atlas, 5th ed. (Jerusalem: Carta, 2011), Map-131, “Fortifications of Rehoboam,” and Map-156, “Districts of Judah”; and Student Map Manual: Historical Geography of the Bible Lands (Jerusalem: Pictoral Archive, 1979), 6.4 (map of Samson story) and 15.2 (index of main names).

[18] Chris McKinny, “Lehi,” in Encyclopedia of the Bible and Its Reception, vol. 18, Mass–Midnight (Berlin: DeGruyter, 2018; hereafter EBR), 82–84, https://

[19] Chadwick, “Khirbet Beit Lei and the Book of Mormon,” 43.

[20] As of this writing, the Beit Lehi Foundation website features a page describing the old well east of Khirbet Beit Lei as the “Well of Samson”; accessed August 16, 2022, https://

[21] McKinny, “Lehi,” in EBR.

[22] Chris McKinny, “‘Shall I Die of Thirst?’: The Location of Biblical Lehi, En-hakkore, and Ramath-lehi,” Archaeology and Text 2 (2018): 53–72, https://

[23] Other than short descriptions in various encyclopedias, little information is available in English about the life and works of Victor Guérin. The most complete description comes from Wikipedia, which gives a basic biography and list of Guérin’s publications; https://

[24] The map of Palestine prepared by Victor Guérin now falls within the public domain. A high-resolution version may be viewed at this link: https://

[25] Victor Guérin, Description géographique, historique, et archéologique de la Palestine—Judée tome deuxième (Paris: Imprimerie Impériale, 1869), 396–400.

[26] Guérin, Description géographique, 396–97.

[27] In addition to the Revised Standard Version (RSV, 1952), the following ten modern Bible versions render the place name Leḥi in 2 Samuel 23:11, demonstrating the consensus supporting this translation: Bible in Basic English (BBE, 1949); New English Bible (NEB, 1970); Good News Bible (GNB, 1976); New Life Version (NLV, 1986); New Revised Standard Version (NRSV, 1989); Contemporary English Version (CEB, 1995); New Living Translation (NLT, 1996); Complete Jewish Bible (CJB, 1998); English Standard Version (ESV, 2001); and Lexham English Bible (LEB, 2011).

[28] McKinny, “‘Shall I Die of Thirst?,’” 62, and “Lehi” in EBR.

[29] ‘Ain Hanniyeh is traditionally connected to the memory of St. Anne (Hebrew Ḥannah), the mother of Mary, the mother of Jesus. But the name Ḥannah lacks the “y” consonant (Hebrew yod) present in Hebrew Ḥaniyah or Arabic Hanniyeh. Also, the Hebrew term Ḥaniyah (חניה) actually refers to a place of encampment. We intend to research the possibility that the spring’s name may in fact be a recollection of the Philistine encampment site in the Refaim Valley referred to in Judges 15:9: “Then the Philistines went up, and pitched in Judah.” The third-person-past plural-form verb “pitched” is rendered from Hebrew יחנו (yaḥanu), meaning “they set up camp,” the noun for which camp would be ḥaniyah. Likewise, in 2 Samuel 23:13, the Philistine force “pitched in the valley of Rephaim.” The Hebrew term for “pitched” is the third-person-past singular-form verb חנה (ḥona), again meaning “set up camp.” In this case, the verb is singular because it agrees with the singular term “force” or “troop,” and the noun for this camp would again be ḥaniyah. Any campsite the Philistines would have utilized in the Refaim Valley would have required a water source. The spring in the valley now bearing the name Ḥaniyah, located just below Leḥi, would have been an ideal place for a recurring Philistine camp.