Reanchoring Our Purpose to Jesus Christ

Clark G. Gilbert, Scott C. Esplin, Jared W. Ludlow, and Barbara Morgan Gardner

Clark G. Gilbert, Scott C. Esplin, and Jared W. Ludlow, "Reanchoring Our Purpose to Jesus Christ," Religious Educator 23, no. 2 (2022): 1–15.

Elder Clark G. Gilbert is the Commissioner of the Church Educational System and was called as a General Authority Seventy on April 3, 2021.

Scott C. Esplin (scott_esplin@byu.edu) is the dean of BYU Religious Education.

Jared W. Ludlow (jared_ludlow@byu.edu) is the publications director of the BYU Religious Studies Center.

Esplin: Thank you for your willingness to share your thoughts and insights with us. For some who may be unaware of your background, will you introduce yourself to our readers.

Gilbert: I really feel like the Lord planted experiences in my life from my very earliest years that had a purpose in Him. I would not have known the significance of many of those experiences until just in the last decade. I grew up in a home where education, and Church education in particular, were highly valued. Both my parents graduated from BYU. Both my parents have law degrees. From my dad there was a love, an almost irrational exuberance, for BYU. My dad grew up in Provo. His father was the dean of Continuing Education. He was the student body president at Brigham Young High School (BY High) and at BYU. He served on the law school board. He was the alumni president. He loved BYU in ways that are just hard to describe. Those feelings were just planted in me as a child.

Elder Clark G. Gilbert. Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Elder Clark G. Gilbert. Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

My mom taught us intellectual curiosity. She was brilliant. She and my dad had met at the BYU debate team, and one of the only tournaments my dad lost was to my mom. I learned the importance of women’s education from her. I learned from my father’s respect for her intellect. My mom had taught us to be intellectually curious. Our summer trips weren’t to the beach. They were study tours. We had presentations and reports we had to do. I knew I was going to be in education, and it would probably be tied to Church education. I thought that it would have been tied to BYU. I’ll share more on that in a minute. But it started at home with my parents.

Then I had the most transformational experience at BYU. Interestingly, it didn’t start in Religious Education. It started in a freshman honors colloquium course with John Tanner, twelve credit hours, six credits each semester. The top row of my freshman dorm bookshelves was all for that class, and a third of the bottom row was for everything else. I read Dostoevsky and Milton and so many religious thinkers, and I learned how thoughtful analysis and religious scholarship and classroom learning and the Spirit could all come together. I remember our instructor saying that if they could add a new book to the standard works, they would choose The Brothers Karamazov. It just was transformational for me. I did have religion courses that were foundational to my testimony. My New Testament course was an example. I fell in love with the Savior in that course. I had Stephen Ricks for the Old Testament. Those courses were transformational.

BYU changed me. Some of it was directly from Religious Education, and some of it was second-order religious education, including my experience with other students and seeing their examples. It wasn’t just these remarkable faculty that changed my life, but it was other students as well. I grew up in Scottsdale, Arizona. I had a few friends in the Church, but when I got to BYU, I realized our faith was strong everywhere, and these kids all had made it here, and they all had stayed true to their commitment to the gospel. So a lot of my BYU experience was in the classroom, and a lot of it was from other students.

BYU changed me. I knew from the first semester I wanted to return there and teach. My dad had taught at the law school with Rex Lee for a season before going back into his law practice. My whole life I thought, “Dad should have been back here.” I would take a humanities course, and I saved Don Marshall’s 101 syllabus because one day I thought I would come back to BYU and teach humanities, of all things. Every course I took I thought, “I can’t wait until I can come back and teach this course.” When I married Christine Calder from Provo, Utah, my family assumed it was because she would let me come back to Provo. She changed my life spiritually, and in a strange way she is the reason that I never got to go to BYU. I’ll just tell you a little bit about that story.

I left BYU and did a master’s program at Stanford. I had majored in international relations at BYU, studying under Jeff Ringer and Lanier Britsch, and I thought, “I’m going to go work in the State Department and get a PhD and then come back to BYU.” And I went and worked in the U.S. Information Agency’s Office of Research on Japan. It sounded like it was going to be so interesting, and it was the dullest thing I had ever done in my life. I thought, “Why in the world did I major in international relations?” The problem was I was going into my senior year, so I pivoted.

I had an internship that summer in business, of all things. And I thought, “This is really interesting.” So I changed what I did my master’s thesis on at Stanford. I still knew I was going into academia, but it kind of redirected me to business. I worked for a strategy consultancy firm headquartered in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I met people like Henry J. Eyring, Matt Holland, Scott Pulsipher—all three were BYU graduates and future university presidents. Even as a strategy consultant, I knew I was going to go into academia, and hopefully eventually return to BYU. It almost didn’t matter how it happened. I thought rather naively, “I’ve got to go get one of those doctorates, wherever I can get in,” because I knew you needed that to teach at BYU. Somehow I got into the Harvard Business School, and I met Clay Christensen. I ended up studying organizational design and industry transformation, and I ended up instead taking a job there right out of my doctoral program. The plan was still come to BYU.

I got to the end of my first round on the faculty. And, as you know in academia, right before you get tenure, everyone starts giving you offers if your work is going well. And if you get tenure, your stock keeps rising. And if you don’t, you drop to the bottom of the pile. I was still at my stock-is-rising moment, and I was getting offers from different organizations, different universities, and I had an offer to go to the Marriott School, and I thought, “Let’s go! This is what I’ve been waiting for my whole life.” But my wife said, “I just don’t think that’s where the Lord wants us.” I responded almost incredulously, “I married you so we could go back to Provo, so why aren’t you just jumping up and down?” She responded, “Let’s just keep praying.”

Then Kim Clark called. He had just left Harvard months before. He was in his first year as president of BYU–Idaho, and I said, “Oh, Kim, I’m so glad you called. My packet is due in for my tenure promotion, and I have these offers at these other universities. One of them is at BYU—what do you think?” He didn’t even respond to my question, replying simply: “I’d like you to pray about another option. I’d like you to come to Rexburg to help us rethink Church education globally.” I didn’t even know where Rexburg, Idaho, was. We prayed and received the most profound answer that that’s where the Lord wanted us. And, you know, I often joke that I knew the parable of the rich young ruler, and I said to Christine, “I feel like the rich young ruler, and I have to give up all of these things that I hoped for my whole life, but I know how the parable ends, so we are going to Rexburg.”

It wasn’t really the best attitude. One morning while this was happening, I was at a stake meeting in Weston, Massachusetts. The last speaker got up, and just the night before I had said to my wife, “I feel like the rich young ruler, but I’m going to go.” The last speaker got up. He was in charge of the grounds crew at the Boston Temple, and he was a very humble man. He said, “I wish people could come into the temple where I enter the temple because Heinrich Hofmann’s painting of the rich young ruler is there.” I thought, “Are you kidding me? I was just telling my wife about this parable.” And he then says, “I wish they could just see what Christ is offering. Every time I look at the rich young ruler, he’s thinking about all the things he’s been asked to give up, and he’s not looking at what Christ is pointing him to.” I was sitting next to a friend, and I was crying. He turned to me and said, “This is a good talk, but it’s not that good” (wondering why I had become so emotional). This was a confirming moment for me that that’s where the Lord wanted us, and so we went to BYU–Idaho in absolute faith and didn’t know where it would lead. So that’s a little bit of background on how I got to Church education, just maybe not in the way I planned.

Esplin: Thank you. That is inspiring. That set you on a track where for the last two decades you have been a professor, an executive, a university president, the president of BYU–Pathway Worldwide, and now a General Authority. From these various perspectives, what have you learned about teaching the gospel of Jesus Christ?

Gilbert: I have three thoughts I want to share. The first is that it needs to be about the student. I think when we fail in Religious Education, it’s almost always because it has become about us, as the educator, as the teacher, and not about the student. There is this wonderful talk from President Henry B. Eyring called “Gifts of Love,” where he says that a gift of love has three main characteristics. First, it’s given with sacrifice. Second, you expect nothing in return. Third, the gift is about the recipient and the recipient’s needs and not the giver’s.[1] And I think there’s a risk sometimes that, as educators, the gifts we give are not about the recipient—they’re about us. I’ve seen that in my own teaching. I’ve seen that in others who are brilliant and talented, and they put together just a beautiful lecture or lesson, but it was about what they could give and not about what the student needed.

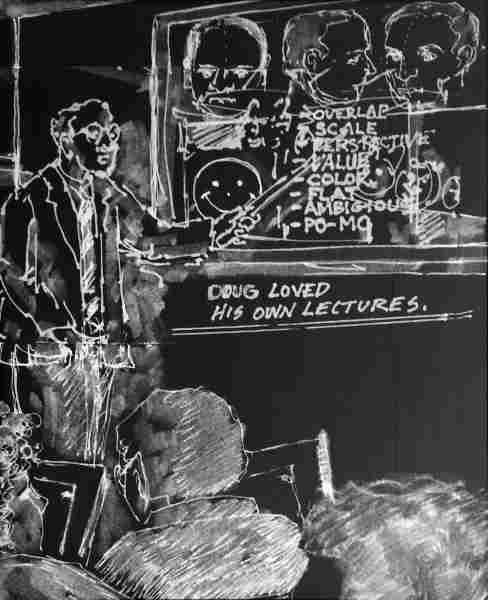

I like a self-portrait by artist Doug Hilson that hangs in The Charles Hotel in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It is a sketch of Doug lecturing in which he is drawing a picture of himself! The caption reads, “Doug loved his own lectures.” I’m not saying, “Ignore your background. Ignore your training. Ignore your professional preparation.” That’s not what I’m saying. But intent really matters in gospel teaching, and if it’s not about the student, we’ll struggle. When you’ve got that sequence right, there’s a whole bunch of very simple downstream things that happen—not because you’ve learned a technique or a practice, but because they flow out of the original motivation, “I am here for these students today. What do they need?” And if that’s your originating motivation, then the idea that you would not need to know your students’ names is an obvious nonstarter. If you claim it’s about the students and you don’t know them, then it’s not about the students.

I remember as a student at BYU I had a humanities class with Don Marshall, and he would videotape the whole first day of class, all two hundred students. There was no lecture; there was no assignment. You just had to go up, say your name, say something about yourself on a videotape, and then you could leave. And if you were last, you had to wait for the whole class to do it. I thought then that this was a waste of time. The rest of the semester he would call on people by name, and he would know something about them. I remember that later when I taught at the Harvard Business School, for a month prior to class I’d get my section assignments for the next semester, and I’d put them in a binder, and I’d memorize the students’ class cards—everything about them. In fact, I remember one student had a beard in his picture, and he had shaved it by the time we started our class. I could never remember his name all semester because I had memorized him with a beard. This sounds so simple, but to our curriculum team at BYU–Pathway or BYU–Idaho when they’d say, “We’ve found pretty compelling ways to grow this section size and maintain most of our learning outcomes,” I’d reply simply, “It’s going to be difficult for me to embrace going beyond the section size where the instructor would not know the names of the students.”

If it's about the student and not about us, we have no problem trusting the student to engage in the learning process. If it's about us, it's very hard to let go. Self-Portrait by Doug Hilson.

If it's about the student and not about us, we have no problem trusting the student to engage in the learning process. If it's about us, it's very hard to let go. Self-Portrait by Doug Hilson.

You can take it from that comment that I am not a big fan of auditorium classrooms. One of the miracles of BYU–Idaho is there aren’t any. We can’t have auditorium lectures because we don’t have those spaces. There’s the Taylor Chapel, and that’s about it. Most of the classrooms for a whole university have thirty to seventy seats. If you don’t know the names, then you probably don’t know their needs. You don’t know their concerns. You don’t know how to connect with them personally. You don’t know how to adapt your instruction to their needs. Of course our scholarship is a vital resource in our teaching, but most of these adaptations require first that we have a student focus far more than a focus on our own particular research or scholarship.

Again, think about President Eyring’s definition of a gift of love and what it means to give with the recipient and not the giver in mind. Doctrine and Covenants 88:122 says, “that all may be edified of all.” Several of our institutions—the teaching emphasis in Seminaries and Institutes, the learning approach of BYU–Hawaii, Ensign College, and BYU–Idaho—have codified in some form this principle that students should teach and learn from one another. If it’s about the student and not about us, we have no problem trusting the student to engage in the learning process. If it’s about us, it’s very hard to let go.

I remember that when I was at BYU–Idaho, one of the concerns we’d hear from colleagues about letting students teach what they’re learning to each other was “I’m going to get killed in the course ratings.” So we started to study it. In the course evaluation instrument, we had three questions that captured the concept “Do your students get opportunities to teach one another in your class?” We put those into a construct when we measured teaching, and then we mapped it to teaching outcomes. The instructor rating was on the vertical axis, and the quartiles for increasing levels of student engagement in teaching one another were on the horizonal axis. The lowest teaching evaluations were for people on the lowest student engagement quartile, basically teachers who lectured. As you increased opportunities for students to teach one another, you got a huge bump in student evaluations. It kept increasing. If our teaching is about the students and their development, they need to have opportunities to teach what they are learning. I have this message from President Clark in his inaugural response at BYU–Idaho:

The challenge before us is to create even more powerful and effective learning experiences in which students learn by faith. . . . To learn by faith, students need opportunities to take action. . . . Some of them will come in the classroom, where prepared students, exercising faith, step out beyond the light they already possess, to speak, to contribute, and to teach one another. . . . It is in that moment that the Spirit teaches.[2]

If we are truly teaching with the students in mind, they also need opportunities to act and show faith. One of the most compelling ways to do that is giving them an opportunity to teach and explain what they are learning. That does not take away from the role of the instructor; in fact, it elevates it. When I used to teach using the case method, I would teach by asking questions. You had to have more command of the material you were teaching in that kind of a setting because you didn’t know what the students were going to say. And if they went over to this domain of knowledge and you didn’t know that, it was going to be really hard to keep teaching that classroom. When you lecture, it’s actually pretty easy. You just narrow it down to what you know, and you don’t have to venture into any unknown territory. But teaching in a student-centered way forces you to have more domain knowledge and depth than any other teaching approach. Beyond that, it requires teaching expertise to know how to take what you have from the students and to guide them to light and truth. In Elder Clark’s words, in that moment when they step beyond the light, they learn what the Spirit teaches.

This gets to my second point: it’s the Spirit that teaches, not us. Elder Richard G. Scott gave one of the all-time great instructions at BYU Education Week in a talk titled “To Learn and to Teach More Effectively.” He says, “If you accomplish nothing else in your relationship with your students than to help them recognize and follow the promptings of the Spirit, you will bless their lives immeasurably and eternally.”[3] Again, having the Spirit be the teacher doesn’t mean we don’t need all of the energy and preparation and insight of our instructors, but it does mean that, for all of us, we need to acknowledge to our students, to ourselves, in the most deliberate of ways that it’s the Spirit that teaches. When we do that, we are going to have much more effective teaching. I remember President Eyring coming to BYU–Idaho and giving a talk called “The Temple and the College on the Hill.”[4] It is one of the more remarkable talks not only about BYU–Idaho but about learning that I’ve ever participated in. He came up three days early for this devotional. He had felt that the Lord had a message for him to give and that the Spirit would reveal that message to him. At a dinner still two days out, he was working to find what that was. He said, “Oh, I know of the talk that you would like, Clark. And I know the talk the faculty would like me to give. And I know the talk the community would like me to give. But what’s the talk the Spirit wants me to give?” And he labored to make sure he aligned himself with that purpose. And this is a brilliant man with wonderful experience in the Church and a real knowledge of what would resonate and sound good. But his deepest purpose was to align himself with the Lord through the Spirit so he would give the message the Lord wanted him to give and the message the Spirit would direct him to give. In our teaching, not only does it need to be about the students, but it has to be about what the Spirit wants us to teach and then inviting the students to listen for that direction, record their feelings, and act on their impressions.

The third thing I would emphasize is that our teaching needs to point to Christ and be grounded in the scriptures and the living prophets. I said earlier I love classic Western literature: Milton, Dante, Kierkegaard, and especially Dostoevsky. I love modern Christian writers: C. S. Lewis and Dietrich Bonhoeffer are two of my favorites. They’re remarkable. I love your colleagues in Religious Education. I love our modern scholarship. We can be edified by all those resources. They’re wonderful complements, but they don’t replace the Lord’s anointed and the scriptures. And so, when we teach, we’ve got to be teaching from the living oracles and from the scriptures themselves and pointing people back to Jesus Christ. This is an insight from Elder Maxwell where he says, “There is an aristocracy among truths.”[5] And that’s not just with other sources of knowledge, but it’s even with the information, the history, and the context of what we teach. All of that’s wonderful and fascinating. I’m preparing for a trip with my family to Jerusalem, and I’m reading about everything you can think about, but if you’re not careful, all of that becomes the sideshow to the core message. When we study history and context and culture, they can be distractions, or they can complement our understanding of a parable from Christ or of what was going on in Kirtland. So when we’re bringing scholarship and other studies into our teaching, they can be wonderful and they can even be edifying, but they should support Elder Maxwell’s hierarchy of truth.

I can think back to one class at BYU I had in Religious Education where I wasn’t deeply edified, but I did learn the birth order of the sons of Lehi. All I remember is just memorizing information. And that knowledge, that birth-order knowledge didn’t help me understand 2 Nephi 9 the way it could have. And so there’s a hierarchy of knowledge, and we ought not to be distracted along the way. When we do bring our scholarship into our teaching, does it lead to and point to edification in the scriptures themselves? As much as we might be edified by modern scholarship, classical literature, and our own cultural analysis and insight, does it point back to Jesus Christ?

Those are the three things I think I’d highlight. When we’re teaching in Religious Education, (1) it’s got to be about the students, (2) it’s the Spirit that teaches, and (3) we’ve got to do everything we can to point our teaching back to the Savior, and that means grounding it in scriptures and modern prophets.

Esplin: Thank you. That’s insightful.

Ludlow: As commissioner, what vision do you have for the mission and direction of Church Education?

Gilbert: Most of the mission statements across the Church Educational System have some discussion about discipleship and some discussion about leadership and giving back. Some of them are quite deliberate in specific language around those purposes. I try to simplify and draw on some of the common language in mission statements across the Church Educational System to say that we’re trying to develop disciples of Jesus Christ who can be leaders in their homes, in the Church, and in their communities. When you think about Church education, our first question needs to be, How does this build discipleship in Jesus Christ? And the second question is, How does it build capacity so these disciples can give back, lead, and lift others in their families, in the Church, and in their communities, professionally and otherwise? I think there’s a risk in both Religious Education and across our universities that we miss that central point.

When I ran the Deseret News, I looked at our resources, and they paled in comparison to great papers around the country. I said things like, “Guys, we’re going to be an “also-ran” if we try to mimic every other newspaper.” And I had a not-so-flattering statement that I would say: “If we don’t differentiate on our core purpose, we’re going to be just another Sacramento Bee.” Now, no offense to the Sacramento Bee. I’m sure it’s a lovely paper, and I realize they have been recognized for some of their strong journalism. But what I was trying to say is that if we mimic the world, we are going to be just another community paper. Even BYU, with what some consider to be an immense budget, pales in comparison to most research universities. Take the University of California, Berkeley, where you were trained, Jared. BYU’s total academic research budget is almost two orders of magnitude smaller than Berkeley’s. So if we don’t differentiate on our core purpose, that’s a strategy for simple replication and we become just another middle-market university.

Let’s embrace our identity. In fact, let me read from Elder Jeffrey R. Holland. Referencing President Spencer W. Kimball’s second-century address, he says:

BYU will become an “educational Mount Everest” only to the degree it embraces its uniqueness, its singularity. We could mimic every other university in the world until we get a bloody nose in the effort, and the world would still say, “BYU who?” No, we must have the will to be different and to stand alone, if necessary, being a university second to none in its role primarily as an undergraduate teaching institution that is unequivocally true to the gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ.[6]

When I look at the Church Educational System, I look at each institution’s distinctive role. BYU–Pathway targets the hidden many. It targets students who didn’t think a traditional education was possible, a student population we don’t reach at any of our other schools. BYU–Pathway also operates everywhere the Church is organized. There’s no other CES institution except for Seminary and Institutes that actually can do that. If you’re in Ghana or the Philippines or South Africa or Mexico City or South Jordan, Utah, you can enroll in BYU–Pathway. The only other analogue is Seminaries and Institutes, so BYU–Pathway has a very distinctive educational strategy.

BYU–Idaho is targeting everyday students who may not be elite academically, but they are hardworking and teachable. The school has an unambiguous, unapologetic teaching emphasis, a year-round calendar supported by online learning. There are no investments in college athletics, graduate programs, or academic research. Every investment in that school goes directly to undergraduate teaching. This, too, is a distinctive educational strategy.

BYU–Hawaii is focused on its target area. President John S. K. Kauwe just spoke at his inauguration. Their goal is not to serve kids from Woods Cross High School or Timpview High School along the Wasatch Front. They are the only Church school with an assigned focus on the Pacific and Asia. They are realizing their goal with a distinctive focus, including trying to shorten time on campus by leveraging BYU–Pathway. BYU–Hawaii has a differentiated educational strategy.

Ensign College is our only school that unambiguously creates job skills curricula. It is a distinctive competence. Moreover, the future growth of Ensign College will come almost entirely online through a curriculum partnership with BYU–Pathway. Here, too, Ensign College has a distinctive educational strategy.

[Our goal as educators] is to build disciples of Jesus Christ who then expand their capacity to lift and build others around them. The Calling of St. Matthew, by Caravaggio.

[Our goal as educators] is to build disciples of Jesus Christ who then expand their capacity to lift and build others around them. The Calling of St. Matthew, by Caravaggio.

So the question for BYU and the charge from Elder Holland is, “How do we embrace our uniqueness, our singularity?” Each of the schools in the Church Educational System has to embrace its distinctive academic role. But no matter what their distinctive academic positioning, they all share the same spiritual purpose in building disciples of Jesus Christ who can be leaders in their homes, in the church, and in their communities. And I liken it to this Caravaggio painting in my office entitled The Calling of St. Matthew. This was a negotiated effort with my wife. I wanted to bring a painting of our children, and I lost that negotiation, so she gave me the Caravaggio print. This previously hung in our hallway. The kids walked past it every day on their way in and out of school. I walked past it every day. There’s a risk in Church education that we miss the miraculous things going on right behind us. You can miss it because you walk by it so much you don’t see its beauty and its amazing design and composition. Or you can also miss it because you overanalyze it. As scholars, sometimes we go so deep on a given topic that we miss its transcendence altogether. For example, when we’re studying John chapter 11 so deliberately we can miss the miracle of “I am the resurrection” (verse 25). In fact, we could do a whole morning devotional on linear plane, chiaroscuro, Michelangelo, and the complex life of Caravaggio and his struggles and miss the whole point of this painting, which is the calling of St. Matthew and understanding someone who is willing to walk away from what he had learned to come and follow Christ. This reinforces my previous point on our scholarship helping us point back to our deeper religious purposes. I think that sometimes, in all of our comings and goings, we miss the main point, which is every single day I can walk into that classroom—whether it is the seminary building, an institute building, a Religious Education course at one of our universities, or a more traditional academic course—and my goal today is to build disciples of Jesus Christ who then expand their capacity to lift and build others around them because of our time together.

So as I think about the mission and direction of Church education, first, each of our institutions has a distinctive role, and we need to embrace that distinctive role. I use one word or a short phrase for each of these institutions in CES. BYU is the educational ambassador and represents the entire system and the Church in its scholarship, academic programs, and ability to be a light beyond the university. BYU is a comprehensive undergraduate teaching university, but it does things as the flagship institution that create a halo for the Church and for the schools that no one else can do. BYU’s the educational ambassador.

BYU–Idaho is the educator. People used to say to me, “I heard BYU–Idaho is super innovative.” I’d respond simply, “Oh yeah. We’re so cutting edge. We’ve got this innovative, breakthrough idea. We want our faculty to—wait for this, this is so novel—we want our faculty to be good at . . . teaching!” So BYU–Idaho is the educator. Everything that isn’t tied to undergraduate student learning has been stripped out of the structure of that university. Scholarship, sports, graduate programs—if it doesn’t lead to student outcomes in the classroom, we don’t do it at BYU–Idaho.

BYU–Hawaii is the Asia-Pacific capstone. There’s no other reason to run a school in such an expensive location as Hawaii, where the airplane ticket costs more than some of our students would pay for their degree in BYU–Pathway. So why in the world are we paying that much money for these students unless it has a unique mission? BYU–Hawaii should be for young adults in the target area, and it should try to be a capstone experience that would leverage BYU–Pathway to reduce what is otherwise a very expensive experience in an expensive island in the Pacific. So BYU–Hawaii is the Asia-Pacific capstone.

Ensign College is the applied curriculum provider. That college is the job-skill curriculum provider to the system, and no one else does that role the way they do.

BYU–Pathway Worldwide is the access provider. There’s no one who is going to reach the enrollment that we are seeing at BYU–Pathway. It is now roughly the equivalent of the combined enrollment of BYU and BYU–Idaho, and it’s barely ten years old. It will operate everywhere the Church is organized, and it will be the engine of growth and outreach for the entire Church Educational System.

And then Seminaries and Institutes is our spiritual anchor, which benefits the entire system through the development of teaching materials and doctrinal preparation across the Church.

We want each CES institution to play a distinctive role, even as they all share a spiritual mission to develop disciples of Jesus Christ who are leaders in their homes, in the Church, and in their communities.

Notes

[1] See Henry B. Eyring, “Gifts of Love” (BYU devotional, December 16, 1980), https://

[2] Kim B. Clark, “Inaugural Response” (BYU–Idaho inaugural address, October 11, 2005), https://

[3] Richard G. Scott, “To Learn and to Teach More Effectively” (BYU Education Week devotional, August 21, 2007), https://

[4] See Henry B. Eyring, “The Temple and the College on the Hill” (BYU–Idaho devotional, June 9, 2009), https://

[5] Neal A. Maxwell, The Smallest Part (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1973), 4.

[6] Jeffrey R. Holland, “The Second Half of the Second Century of Brigham Young University” (BYU University Conference address, August 23, 2021), https://