Fred E. Woods, "The Ascension of Abraham: A Mortal Model for the Climb to Exaltation," Religious Educator 23, no. 2 (2022): 46–63.

Fred E. Woods (fred_woods@byu.edu) is a professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU.

Introduction: Lens of Inquiry

Talmudic literature proclaims, “We do not see things as they are.” Rather, “we see things as we are.”[1] This profound statement reminds us that our vision is often blurred by our mortal misjudgments and forgetfulness; we forget that we are in fact the sons and daughters of God, the literal offspring of Deity. The talmudic aphorism is an invitation to introspection, an adjustment of our lens, before we give serious thought to another person, particularly one so enlightened as Abraham, who we are told has entered into his exaltation (see Doctrine and Covenants 132:29). We can learn much from viewing Abraham as he moves through secular history on a horizontal human plane, from birth to death. His noble life serves as a model for the process of deification, seen in his divine nature and conscientious covenantal choices. Abraham was one of the “noble and great ones” who was “chosen before” he was born (Abraham 3:22–23) and has now reached exaltation (see Doctrine and Covenants 132:37). Indeed, we should follow the Lord’s admonition to “look unto Abraham [our] father” (Isaiah 51:2)[2] as we ourselves strive to qualify for godhood.

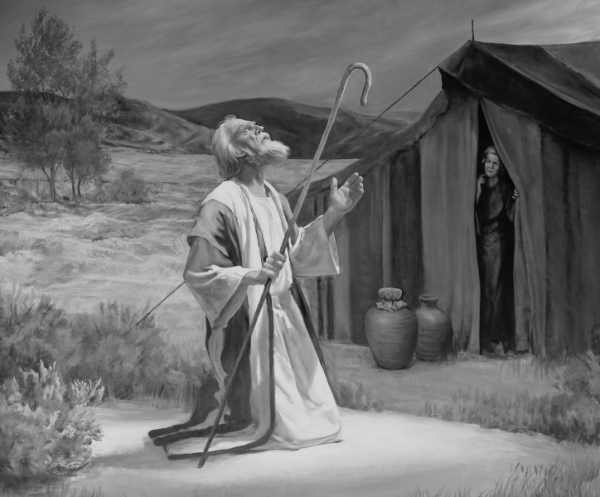

We can learn much from viewing Abraham as he moves through secular history on a horizontal human plane from birth to death. Abraham Sees the Promised Land, anonymous after Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld.

We can learn much from viewing Abraham as he moves through secular history on a horizontal human plane from birth to death. Abraham Sees the Promised Land, anonymous after Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld.

This paradigm suggests that we should strive to quench our thirst from a divine fount in preference to those fountains that are not as pure. President Marion G. Romney noted, “I don’t know much about the gospel other than what I’ve learned from the standard works. When I drink from a spring I like to get the water where it comes out of the ground, not down the stream after the cattle have waded in it.”[3]

The Prophet Joseph Smith once said, “Could you gaze in heaven five minutes, you would know more [about God] than you would by reading all that ever was written on the subject.”[4] Thus, until we have received our own celestial seeric stones of perfect light (see Doctrine and Covenants 130:11), it is wise to read and ponder what others have seen with their spiritual eyes, especially prophets, seers, and revelators who have had a sacred glimpse of the great patriarch Abraham. Secondarily, inasmuch as the Lord has declared that there “are many things contained [in apocryphal literature] that are true” (91:1), we must spiritually align ourselves with him so that we might be “enlightened by the Spirit” in order to “obtain benefit therefrom” as we search other sources (v. 5).[5]

We must also be keenly aware that what we bring to a text has a significant impact on what we receive from the encounter.[6] Thankfully, we are not limited to a single text when studying Abraham. Rather, we have several sources of scripture to help us better view and appreciate a model that I propose is like a stairway to heaven, for they enable us to analyze the progression of Abraham as he ascends through mortality to a divine throne. Like the Liahona of which Nephi spoke, this is best accomplished by engaging a sacred text with “faith and diligence and heed” so that we uncover “a new writing” that is “changed from time to time” as we continue our personal journey to a far better land of celestial promise (1 Nephi 16:28–29).

In order to understand Abraham in mortality, in the second act of a play performed in a theater on telestial terrain,[7] we of course turn to scripture. Specifically, we will scrutinize select segments of the largest scriptural Abrahamic corpus of material, which is the primary focus of our study (Genesis 12–25), in an attempt to uncover a heavenly staircase as a pattern of one who strove for perfection.[8] At the same time, we will cite the Book of Abraham, which not only sheds light on Abraham’s mortal sojourn (Abraham 1–3) but also provides a glimpse of act 1, where we encounter a premortal Abraham (3:22–23). We will also review act 3, which provides us with a view of a postmortal, deified Abraham (see Doctrine and Covenants 132:37).

Leaving Babylon Behind

Why are God’s first words to Abram “Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and from thy father’s house”? (Genesis 12:1). There appears to be a definite connection between the story of the Tower of Babel in Genesis 11 and what immediately follows in the next chapter of the Abrahamic narrative. Genesis 11:4 seems to portray a carnal people who seek the goods and gods of Babylon, desiring to make a name for themselves by building an imitation temple. In contrast, Abram sought the blessing of adhering to a divine name, to make “a great nation” (12:2) “and to be a father of many nations” (Abraham 1:2), wherein “all families of the earth [would] be blessed” (Genesis 12:3).[9]

The relationship of Abram with his earthly father Terah is also instructive. As Abraham 1 points out, Terah was an idolatrous man who sought the empty idols of Egypt, while Abram focused on a righteous, living God. Yet Abram wanted to bring his father along the path to Zion. It is also noteworthy that Abram, not Terah, was the leader of the journey to the promised land. Abram explained, “My father followed after me” (Abraham 2:4, which corrects Genesis 11:31). In addition, it is worth noting that the transitional shift from Babylon occurs when “Terah died” (Genesis 11:32) and Abram was charged to leave his country and his “father’s house” (12:1). His mortal father had been pronounced dead, and it was time to “awake! and arise” (2 Nephi 1:14) and look for things heavenward. By leaving Babylon behind and looking heavenward, Abraham led the way for his posterity to inherit eternal life.

Divine Discontent: The Key to Overcoming Heir Pollution

Abram shows early signs of his seeric inclinations and divine discontent in his introductory words in the Book of Abraham:

In the land of the Chaldeans, at the residence of my fathers, I, Abraham, saw that it was needful for me to obtain another place of residence; and, finding there was greater happiness and peace and rest for me, I sought for the blessings of the fathers, and the right whereunto I should be ordained to administer the same; having been myself a follower of righteousness, desiring also to be one who possessed great knowledge, and to be a greater follower of righteousness, and to possess a greater knowledge, and to be a father of many nations, a prince of peace, and desiring to receive instructions, and to keep the commandments of God, I became a rightful heir, a High Priest, holding the right belonging to the fathers. (Abraham 1:1–2)

These introductory verses are a lens that sheds light on Abram’s sudden shift from Babylon (a worldly environment) to Zion (a covenantal, heavenly abode). It is also apparent, from the Book of Abraham and from noncanonical sources, that the reason it was “needful” for Abram “to obtain another place of residence” was that he had preached against idolatry, a message that his fathers “utterly refused to hearken to” (Abraham 1:5).

The book of Jubilees notes that after Abram asked his father Terah, “What help or advantage do we have from these idols before which you worship and bow down?” he pointed out that there was “not any spirit in them, for they are mute.” Abram then admonished Terah, “Do not worship them. Worship the God of heaven” (Jubilees 12:3–4). The text next notes that the sixty-year-old Abram “arose in the night and burned the house of idols.”[10] Such destruction apparently infuriated some of Abram’s Mesopotamian neighbors and his father and provides evidence of Abram’s bold, righteous anger.[11]

These introductory verses in the Book of Abraham are also a model of how a son overcame what might be referred to as “heir pollution” as he forgave Terah for his idolatrous, wicked behavior and “sought for the blessings of the [righteous] fathers” (Abraham 1:2). And, as noted, we encounter in the next chapter (also attested in Genesis 11:31) a father and son desiring to walk together to a far better land of promise, although for Terah that desire was only temporary (see Abraham 1:30; 2:4–5).

What the text implies is not only Abram’s deep, divine desire to receive the blessings of the ancient fathers and patriarchs (see Abraham 1:2) but also Abram’s forgiveness of his own father and ancestors, who were steeped in idolatry (see v. 5). This circumstance eventually left Abram with only the divine hand of a Heavenly Father to spare his life (see vv. 15–16). This model of a forgiving son also emerges in another ancient text in which we hear another valiant son counsel on forgiveness, which is a powerful application: “Condemn me not because of mine imperfection, neither my father, because of his imperfection . . . ; but rather give thanks unto God that he hath made manifest unto you our imperfections, that ye may learn to be more wise than we have been” (Mormon 9:31).

Winning Souls for Christ

The Genesis text next informs us that Abram as well as Lot (and their families) departed from “Ur of the Chaldees” (Genesis 11:31)[12] and took with them not only “their substance that they had gathered” but also “the souls that they had gotten in Haran; and they went forth to go into the land of Canaan” (12:5).[13] The KJV translation of the word gotten in this verse derives from the Hebrew word asah, meaning “to make,” wherein conversion is implied. This is strengthened by the Book of Abraham, where the text notes that Abram and his family departed from Haran with “the souls we had won in Haran” (Abraham 2:15). Jewish tradition also lends secondary support to this inspired interpretation. “The Midrash asked why then Genesis 12:5 did not simply say, ‘whom they had converted,’ and instead says, ‘whom they had made.’” The Midrash explains that this verse “teaches that one who brings a nonbeliever near to God is like one who created a life.”[14]

This concept implies that Abram led his family in a contest for souls, a spiritual struggle to rescue people as they pursued their journeyed to a far greater land of promise. It also provides a glimpse into the great and noble soul of Abraham, who mirrored the qualities expressed in this statement by the Prophet Joseph Smith: “A man filled with the love of God is not content with blessing his family alone, but ranges through the whole world, anxious to bless the whole human race.”[15] In losing our lives in striving to win souls for Christ, we each find our own life’s ultimate purpose—to prepare to inherit eternal life with God.

The Heavens Bear Witness of Christ

Having left Haran, and upon entering the land of Canaan, Abram is told by the Lord, “Unto thy seed will I give this land,” whereupon Abram immediately builds an altar to worship the Lord God Jehovah (Genesis 12:5–7). However, because of a terrible famine, Abram is compelled to pass through the land and temporarily settle in Egypt (see v. 10). Therefore, he becomes a type of Christ, whose life was similarly preserved when Joseph and Mary were forced to flee from Canaan to Egypt (see Matthew 2:13–16).[16]

While in Egypt, Abram would have received a better understanding of a previous revelation in which he learned that the Egyptians had imitated the priesthood order that Abram himself sought (see Abraham 1:4, 26). During his Egyptian sojourn he also learned more about records he had received, which contained “a knowledge of the beginning of the creation, and also of the planets, and of the stars, as they were made known unto the fathers” (v. 31).

Through the Urim and Thummim (Hebrew words meaning “lights and perfections”), he “saw the stars” and learned that “one of them [Kolob] was nearest unto the throne of God” and that it governed “all those planets which belong to the same order” (Abraham 3:2–3, 9). In addition, he was taught that the stars and planets were analogous to the spirits God had created. He also learned that Jehovah was “more intelligent than they all” (v. 19). Further, he came to understand that there were “many of the noble and great ones” whom God had appointed to become rulers. Among them was Abram, who had been chosen to such an exalted station before he was born (see vv. 22–23).

Against the dark night, Abram was to see the Light of this World and learn of other leading luminaries, as well as those rebellious spirits who followed an “angry” Lucifer and chose to keep not their first estate (Abraham 3:28). In addition, he received with great clarity a vision of understanding, by which he discovered the purpose of life and how the earth was created as a probation location wherein God’s children would be tested “to see if they [would] do all things whatsoever the Lord their God shall command them” (v. 25). This drawing of the curtains appears to be very important for Father Abram: he saw the purpose of earth’s stage, the platform for mortality’s play in which chosen vessels would be cast in various roles to exemplify Christlike characteristics. It appears that Abram himself keenly understood that a series of tests would follow to see if he would make and obey covenants and thus bear witness of Christ by adhering to him.

Generating Light Instead of Heat: Blessed Are the Peacemakers

Having narrowly escaped being sacrificed to the Egyptian gods in his youth while dwelling in Mesopotamia (see Abraham 1:12–16), Abram also barely escaped death when he entered Egypt. He again learned he could trust the great Jehovah, who instructed him to tell the Egyptians that Sarai was his sister instead of his wife (see Genesis 12:12–20; Abraham 2:22–25). Although Abram deceived Pharaoh and the Egyptians, he was following the Lord’s instructions to him.

At the time of Abram’s reentry into Canaan, he may have been tested in another way, not by another near-death experience but rather with riches: “Abram was very rich in cattle, in silver, and in gold” (Genesis 13:2). Because of their large number of flocks and cattle, Lot and Abram could not dwell in the same place (see vv. 5–6). Subsequently, “there was a strife between the herdmen of [Abram] and the herdmen of [Lot]” (v. 7). However, Abram initiated a generous solution to a serious problem. Choosing to generate light instead of heat, he told Lot, “Let there be no strife . . . between me and thee, and between my herdmen and thy herdmen; for we be brethren” (v. 8). Abram’s plan was to let Lot (who should have allowed Abram, his leader, to choose first) select whatever portion of the land he desired; Abram would have what was left over (see vv. 9–12). Instead of choosing temporary telestial treasures, he chose to set a righteous example by putting familial relationships first, leaving a legacy for his posterity to ponder. Further, he chose to submit to Melchizedek by paying tithes of all his increase (see 14:20). At one point “Abraham received the priesthood from Melchizedek” (Doctrine and Covenants 84:14) and a blessing from his hands wherein he was told, “Blessed be Abram of the most high God, possessor of heaven and earth” (Genesis 14:19). By choosing to be a peacemaker and choosing to submit to the law of the tithe (and certainly by magnifying his priesthood in other ways), Abram became a possessor of all that the Father has.

The Need for Faith in the Light of the World to See through the Darkness of Mortality

In Genesis 15 we learn that Abram’s faith was tested by his not having the offspring he desired. Abram said, “Lord God, what wilt thou give me, seeing I go childless?” (v. 2). Jehovah responded, “Look now toward heaven, and tell [i.e., count] the stars, if thou be able to number them: and he said unto him, So shall thy seed be.” “And he [Abram] believed in the Lord; and he counted it to him for righteousness” (vv. 5–6). This encounter apparently served as a reminder of the previous vision Abram had received as he looked at the stars of a dark Egyptian sky while the Lord comforted him, saying, “I will multiply thee, and thy seed after thee, like unto these [stars]” (Abraham 3:14).

Abram was then told he would also receive the land of Canaan for an inheritance. When he asked how that would occur, the Lord asked him to offer sacrifice (see Genesis 15:7–11). The text then explains that Abram learned of the Egyptian bondage and ultimate deliverance of his descendants; and before the Lord promised him the land of Canaan (vv. 13–18), Abram offered sacrifice. “And when the sun was going down, a deep sleep fell upon Abram; and, lo, an horror of great darkness fell upon him” (v. 12).

In Joseph Smith’s inspired translation we also learn that, immediately following this dark experience, Abram was shown a vision in which he “looked forth and saw the days of the Son of Man, and was glad, and his soul found rest, and he believed in the Lord, and the Lord counted it unto him for righteousness” (JST Genesis 15:12). Such a mixture of light and darkness is certainly reminiscent of a future theophany in which another prophet would encounter the powers of heaven and hell in a sacred grove (see Joseph Smith—History 1:15–17). Both Abraham and Joseph managed to exercise mighty faith in the Light of the World, even Jesus Christ, to pierce through the darkness of their mortal experience and find answers to their challenges.

The Need to Adhere to Sacred Covenants to Reap the Promised Blessings

The divine promise made to Abram is now given:

And when Abram was ninety years old and nine, the Lord appeared to Abram, and said unto him, I am the Almighty God; walk before me, and be thou perfect. And I will make my covenant between me and thee, and will multiply thee exceedingly. And Abram fell on his face: and God talked with him, saying, As for me, behold, my covenant is with thee, and thou shalt be a father of many nations. Neither shall thy name any more be called Abram, but thy name shall be Abraham; for a father of many nations have I made thee. And I will make thee exceeding fruitful, and I will make nations of thee, and kings shall come out of thee. And I will establish my covenant between me and thee and thy seed after thee in their generations for an everlasting covenant, to be a God unto thee, and to thy seed after thee. And I will give unto thee, and to thy seed after thee, the land wherein thou art a stranger, all the land of Canaan, for an everlasting possession; and I will be their God. (Genesis 17:1–8)

In these verses, we learn that Abram was now ninety-nine years old and that the Lord wanted to bind a covenant with him. He was reminded that he would be a “father of many nations” (v. 4). In addition, his name was changed from Abram to Abraham, a Hebrew name that may be translated as “high or exalted father of a multitude.”[17] The introduction of a new name confirms that these verses are to be viewed in a sacred covenantal context, especially for those who belong to the house or family of Israel. It also reminds modern-day covenant people of a “new name” that is given to all those who are heirs of the celestial kingdom (see Doctrine and Covenants 130:11). Further, Abraham is told that kings will come out of his fruitful lineage. Such verbiage (for those belonging to the royal lineage of Abraham) may symbolically serve as a reminder that, if faithful to covenants, his descendants are destined to become “priests and kings” who will receive of God’s “fulness, and of his glory” (76:56).

The Book of Abraham sheds additional light on the implications of this sacred covenant:

And I will make of thee a great nation, and I will bless thee above measure, and make thy name great among all nations, and thou shalt be a blessing unto thy seed after thee, that in their hands they shall bear this ministry and Priesthood unto all nations; and I will bless them through thy name; for as many as receive this Gospel shall be called after thy name, and shall be accounted thy seed, and shall rise up and bless thee, as their father; and I will bless them that bless thee, and curse them that curse thee; and in thee (that is, in thy Priesthood) and in thy seed (that is, thy Priesthood), for I give unto thee a promise that this right shall continue in thee, and in thy seed after thee (that is to say, the literal seed, or the seed of the body) shall all the families of the earth be blessed, even with the blessings of the Gospel, which are the blessings of salvation, even of life eternal. (Abraham 2:9–11)

These verses reveal that Abraham and his descendants will be blessed not only with a promised land (celestial property) but also with a continuation of seed (posterity); the priesthood will continue with Abraham’s descendants, by whom the world will be blessed, “even with the blessings of the Gospel, which are the blessings of salvation, even of life eternal.” Further, Latter-day Saint doctrine asserts that Abraham was baptized,[18] received the priesthood (see Doctrine and Covenants 84:14), and entered into the order of celestial marriage, with the guarantee that he would have eternal posterity. In addition, Latter-day Saint theology maintains that these same blessings extend to Abraham’s posterity and that “the portions of the [Abrahamic] covenant that pertain to personal salvation and eternal increase are renewed with each individual who receives the ordinance of celestial marriage.”[19]

In Abraham’s day, there was an additional stipulation that went hand in hand with this covenant but is not required in our present dispensation. Abraham was told, “Ye shall circumcise the flesh of your foreskin; and it shall be a token of the covenant betwixt me and you. And he that is eight days old shall be circumcised among you, every man child in your generations” (Genesis 17:11–12). The Joseph Smith Translation of verse 11 explains that circumcision at eight days old was done as a reminder that “children are not accountable . . . until they are eight years old.” The text of Genesis further notes that “the uncircumcised man child whose flesh of his foreskin is not circumcised, that soul shall be cut off from his people; he hath broken my covenant” (v. 14).

This token in the flesh served as a physical reminder to Abraham and his posterity that if they were true to the promises they made with Jehovah, their seed would continue forever. If they did not keep or remember the covenant, they would be dismembered[20] from the chosen seed of Abraham’s family; in other words, they would be “cut off” from God’s people and would no longer be entitled to promised blessings. This Hebrew verbiage connected with circumcising the flesh of the male reproductive organ and with cutting, or making, a covenant (as in the Hebrew root k-r-t, used in Genesis 15:18) is interrelated, giving the vivid sense of being “cut off” when covenants are not adhered to.[21] In such cases the promise of eternal seed does not continue, a concept also embedded in the Hebrew language, where the root z-k-r for the word male and remember are the same.

The sad state of those who lose these priceless blessings is described vividly in modern scripture where we read of those whose “hearts are corrupted” (Doctrine and Covenants 121:13) as well as the consequences: “They and their posterity shall be swept from under heaven, saith God, that not one of them is left to stand by the wall [a Hebrew idiom referring to males]. . . . They shall not have right to the priesthood, nor their posterity after them from generation to generation” (Doctrine and Covenants 121:15, 21; see 1 Kings 16:11).

Following this covenantal encounter, Abraham entertains three holy men on the plains of Mamre. During the visit Abraham and Sarah are informed that aged, barren Sarah will soon have a son, thus fulfilling a portion of the covenant (see Genesis 18:1–14). In addition, Abraham learns of the impending destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, because “their sin is very grievous” (v. 20). Abraham thus asks, “Wilt thou also destroy the righteous with the wicked?” (v. 23). What follows is another episode in which Abraham is a type of Christ. When he comes before the Lord as an advocate for his people, Abraham asks with great heartfelt faith if the Lord would be willing to spare Sodom and Gomorrah if fifty righteous souls could possibly be found, then forty, thirty, twenty, and finally ten righteous people (see vv. 24–32). This powerful advocacy for the souls of his family reveals yet again that Abraham (like the Lord) cared greatly for his family and did not want one of them to be lost. Notwithstanding his pleadings, the wicked cities of Sodom and Gomorrah were destroyed (see Genesis 19). Yet people who keep their covenants as did Abraham will be blessed with the rights to the priesthood and eternal posterity.

Submission Leads to Exaltation

When Abraham was presented with the covenant of circumcision, he and Sarah were promised they would have a son. The text notes that Abraham rejoiced, and surely this was because he and barren Sarah would finally, and miraculously, have a child of their own (see JST Genesis 17:17). Abraham named his chosen son Isaac (tzachak), the Hebrew root of which means “to rejoice” or “to laugh” (see Genesis 21:3–6). Yet another severe trial lay ahead for Abraham and Sarah: Jehovah issued the command to Abraham to sacrifice his promised son, Isaac, who had undoubtedly brought immense joy to this aged couple. The text states that God tried Abraham by instructing him to take Isaac to the land of Moriah and offer him as a sacrifice. Just as Abraham was about to slay his son, “the angel of the Lord called unto him out of heaven, and said, Abraham, . . . lay not thine hand upon the lad, neither do thou any thing unto him: for now I know that thou fearest God, seeing thou hast not withheld thy son, thine only son from me” (22:11–12). Abraham was then told that because of his faithful works he would be blessed with a multiplicity of seed (see vv. 15–18).

Surely Abraham's proving experiences and pattern of obedience to God prepared him for his ultimate test of willing to sacrifice his only son. Abraham on the Plains of Mamre, by Grant Romney Clawson. Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Surely Abraham's proving experiences and pattern of obedience to God prepared him for his ultimate test of willing to sacrifice his only son. Abraham on the Plains of Mamre, by Grant Romney Clawson. Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

In the Book of Mormon, we learn that Abraham’s willingness to offer his son Isaac was “a similitude of God and his Only Begotten Son” (Jacob 4:5). In this narrative, there is displayed a willingness on the part of a righteous father and son to surrender all. Pertaining to the willingness of our Heavenly Father to sacrifice his son as represented by the great patriarch Abraham, Elder Melvin J. Ballard noted the following:

I think as I read the story of Abraham’s sacrifice of his son Isaac that our Father is trying to tell us what it cost him to give his Son as a gift to the world. . . . I can see our dear Father behind the veil looking upon these dying struggles until even he could not endure it any longer; and, like the mother who bids farewell to her dying child, has to be taken out of the room, so as not to look upon the last struggles, so he bowed his head, and hid in some part of his universe, his great heart almost breaking for the love that he had for his Son.[22]

What gave Abraham the strength to not withhold his only begotten son, who came from the womb of his beloved Sarah? That Abraham had previously undergone an extreme trial when he himself was nearly offered as a human sacrifice is important to remember (see Abraham 1:15–16). Did he think that, similar to his own rescue, God would save Isaac at the last possible moment? Perhaps this question is best answered by the following facts: First, Abraham had previously learned that the purpose of the earth’s creation was to serve as a testing ground to determine whether God’s children would be obedient (see Abraham 3:24–25). Second, Abraham had been shown in vision that the Lord Jesus Christ would be raised from the dead, as would Abraham (see JST Genesis 15:10–12). Third, the author the of the book of Hebrews explained, “By faith Abraham, when he was tried, offered up Isaac[,] . . . accounting [i.e., considering] that God was able to raise him up, even from the dead” (Hebrews 11:17, 19). Surely Abraham’s proving experiences and pattern of obedience to God prepared him for his ultimate test of willingness to sacrifice his only son. Such faithful submission to God’s will established for all time a powerful model for all who undertake the journey to exaltation.

The Need to Renew Covenants and Let God Prevail in Our Lives

This knowledge gave Abraham not only the faith to obey God’s command to sacrifice Isaac but also the strength to carry on when his beloved Sarah died at age 127. Abraham, now alone, was determined to ensure that the covenant would continue with Isaac and a virtuous woman whom the Lord would choose. Therefore, he sent his eldest servant (probably Eliezer per 15:2) to find a wife for his son. However, before his trusted servant departed, he was asked to put his hand under Abraham’s thigh and swear a sacred oath that he would not select a daughter of the Canaanites (see 24:2–3). The Joseph Smith Translation uses the word hand instead of thigh in this verse, so it appears that the meaning is that Abraham’s servant was to put his hand under the hand of his master, Abraham, as it rested on his thigh. The word thigh in this setting is most interesting since the Hebrew word used here, yârêk, also means the seat of procreative powers.[23] Thus, the narrative is again rich with the symbolic understanding of perpetual seed in connection with the Abrahamic covenant and is a reminder of the importance of not marrying outside the covenant, wherein these blessings are made possible.

The faithful servant of Abraham does indeed find a righteous woman, named Rebekah, who has a familial tie to Abraham and who (like Sarah) appears to be an equal to Isaac and worthy of the promised blessings. When her family asked if Rebekah would go with Abraham’s servant, she said simply, “I will go” (Genesis 24:58). Her family then blessed Rebekah and said, “Thou art our sister, be thou the mother of thousands of millions” (v. 60). Through this faithful union, the covenant continued and they had twin sons, one of whom was named Jacob (25:23–26). Jacob proved faithful and the covenant was also renewed with him. Like his grandfather Abraham, he received a new name, Israel, meaning “one who prevails with God” (32:28). Since that time, the term house of Israel has been used to refer to the descendants of Jacob, who are from the family of Abraham, the chosen patriarch. Those who renew sacred covenants and let God prevail in their lives will receive all the blessings that Abraham received, even eternal life.

Abraham, a Noble Friend of God

The notion of Abraham’s being God’s friend is attested in both the Old Testament (see Isaiah 41:8; 2 Chronicles 20:7) and the New Testament, where James proclaims, “He was called the Friend of God” (James 2:23).[24] The question naturally arises why Abraham was referred to as “the Friend of God.” It seems the answer has everything to do with the principle of strict obedience. Even before his mortal birth, Abraham was recognized as one of the “noble and great ones,” one who was “chosen” before he was born (see Abraham 3:23–24). The issue of obedience and selection is also reiterated in Alma the Younger’s teachings where he notes that high priests were “called and prepared from the foundation of the world . . . on account of their exceeding faith and good works, . . . having chosen good” in the premortal life (Alma 13:3).

As already noted, while in Egypt Abraham learned that planet earth was a place to be tested and that the purpose of mortality was to see if God’s children would consistently obey in any given circumstance: “And we will prove them herewith, to see if they will do all things whatsoever the Lord their God shall command them” (Abraham 3:25). Abraham proved to be God’s faithful friend and fulfilled the charge of Jesus: “Ye are my friends, if ye do whatsoever I command you” (John 15:14). We too need to be a friend of God by following Abraham’s example of continual obedience.

Conclusion

Abraham, like Jesus, sought continually to do the will of the Father. The experiences of mortal Abraham’s life illustrate a faithful journey to a promised land and serve as an invitation to all mortals to migrate forward to a far greater land of celestial promise. “Abraham received all things, whatsoever he received, by revelation and commandment, by my word, saith the Lord, and hath entered into his exaltation and sitteth upon his throne. Abraham received promises concerning his seed, and of the fruit of his loins—from whose loins ye are” (Doctrine and Covenants 132:29–30). The promises made to Father Abraham are the same promises made to his seed. “This promise is yours also, because ye are of Abraham. . . . Go ye, therefore, and do the works of Abraham” (vv. 31–32), be called God’s friends, and become joint-heirs with Christ.

Notes

[1] https://

[2] This same verse admonishes that we should also “look unto . . . Sarah.” However, because of page limitations, the focus of this article is on Abraham. It should be understood that Abraham’s exaltation was not independent of Sarah. It is implied that she too has been exalted, because celestial marriage is required to inherit the highest degree of the celestial kingdom or, in other words, exaltation (see Doctrine and Covenants 131:1–4). Sarah was truly the equal of Abraham and may have even exceeded him in spirituality. They were companions in their journey to Zion and serve as a wonderful example of Paul’s teaching that “neither is the man without the woman, neither the woman without the man, in the Lord” (1 Corinthians 11:11). On the topic of Sarah as a true helpmeet for Abraham, see E. Douglas Clark, The Blessings of Abraham: Becoming a Zion People (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2005), 59–61.

[3] Address delivered at Coordinators’ Convention, Seminaries and Institutes of Religion, April 13, 1973, quoted in “Search the scriptures; know personally what Lord says,” Church News, March 23, 1991, https://

[4] Discourse, 9 October 1843, as Reported by Willard Richards, p. [121], The Joseph Smith Papers, https://

[5] Although Doctrine and Covenants section 91 is referring specifically to the Apocrypha, my opinion is that the principle of reading other noncanonical books with the assistance of the Holy Ghost assists with discerning truth from error, such as the Pseudepigrapha. A few of these extra canonical sources will be incorporated in this study. For a brief definition and overview of the books known as the Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha, see “Apocrypha,” Bible Dictionary in the Latter-day Saint edition of the KJV Bible (hereafter Bible Dictionary), 610–11; and “Pseudepigrapha,” Bible Dictionary, 710. The latter notes, “The pseudepigrapha are useful in showing various concepts and beliefs held by ancient peoples in the Middle East. In many instances latter-day revelation gives the careful student sufficient insight to discern truth from error in the narratives, and demonstrates that there is an occasional glimmer of historical accuracy in those ancient writings. The student may profit from this, always applying the divine injunction that ‘whoso is enlightened by the Spirit shall obtain benefit therefrom’ (D&C 91:5).”

[6] Noted German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer maintained that “people have a historically-effected consciousness (wirkungsgeschichtliches Bewußtsein), and that they are embedded in the particular history and culture that shaped them. . . . [Thus,] interpreting a text involves a fusion of horizons (Horizontverschmelzung)” in which the scholar finds the ways that the text’s history articulates with his or her own background. https://

[7] The idea of mortality as the second act of a three-part play comes from Elder Neal A Maxwell, “Enduring Well,” Ensign, April 1997, 7, who noted, “Trying to comprehend the trials and meaning of this life without understanding Heavenly Father’s marvelously encompassing plan of salvation is like trying to understand a three-act play while seeing only the second act.”

[8] For an excellent treatment of the entire life and teachings of Abraham, see E. Douglas Clark, The Blessings of Abraham: Becoming a Zion People (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2005).

[9] The humility and godliness of Abraham, who sought Zion, may also be viewed as diametrically opposed to the arrogance and wickedness of Nimrod, a contemporary of Abraham who sought to build the kingdom of Babylon. On this topic see Clark, Blessings of Abraham, 34–38.

[10] Jubilees 12:2–4, 12, in R. H. Charlesworth, ed., The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, 2 vols., (Garden City, NY: 1983–85), 2:80. Further, the Apocalypse of Abraham 8:6 indicates that this idolatrous house belonged to Terah. However, it notes it was consumed by thunder (probably meaning lightning). If such is the case, perhaps Abraham’s involvement in this destruction was that he prayed for it and invoked a divine power to devour this house of idolatry, or perhaps the destruction was a mixture of Abraham’s and Jehovah’s combined work. In any case, these narratives suggest that Abraham was somehow involved in such a destruction that caught people’s attention. This theme of Abram’s rejection of idolatry is treated in detail in chapters 1–8 of the Apocalypse of Abraham. See Charlesworth, Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, 1:689–93.

[11] On Abram’s boldness in rejecting idols, see Louis Ginzberg, The Legends of the Jews, 7 vols. (Philadelphia: Publication Society of America, 1912–38), 1:195–203.

[12] This region is also noted in Abraham 1:20 as “Ur, of Chaldea.” Evidence suggests that this region, once identified as being in southern Mesopotamia, is actually in northern or upper Mesopotamia, although two cities by the name of Ur are known in Mesopotamia. E. Douglas Clark, in Blessings of Abraham, 34, notes that when Abraham sent his servant Eliezer back to his native land to find a wife for Isaac, he went to the city of Nahor (see Genesis 24:2–10), which was in northern Mesopotamia. Clark further notes that “the Book of Abraham depicts heavy Egyptian influence there during Abraham’s day, making the southern location impossible: ancient Egypt never exercised control over the southern Ur,” but it did in northern Mesopotamia.

[13] One item that is omitted in the Genesis account is that Abram took sacred records with him on his journey from Ur to the promised land of Canaan. However, we find the preservation of sacred records included in the Book of Abraham. Therein, Abraham noted, “But the records of the fathers . . . the Lord my God preserved in mine own hands; . . . [these] have I kept even unto this day” (Abraham 1:31). Such records were no doubt just as important for Abram’s family’s journey as they were for Lehi’s family, who would later embark on another sacred journey to another promised land. Nephi noted that such records were “of great worth unto us” and that “it was wisdom in the Lord that we should carry them with us, as we journeyed in the wilderness towards the land of promise” (1 Nephi 5:21–22). The Book of Jubilees 12:27, in R. H. Charlesworth, ed., Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, 2:82, also supports the Book of Abraham’s mention of records, inasmuch as we find that Abram “took his father’s books—and they were written in Hebrew, in the tongue of creation.” Such sacred records may have been used in winning souls for Jehovah when Abraham reached Haran.

[14] https://

[15] Letter to Quorum of the Twelve, 15 December 1840, p. [2], The Joseph Smith Papers, https://

[16] For an interesting study that points to other ancient sources that speak of Abraham’s experiences in Egypt, see Hugh Nibley, Abraham in Egypt, 2nd ed. (Provo, UT: FARMS; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000).

[17] Sarai’s name was also changed, to Sarah (see Genesis 17:15). A mighty blessing foretold she would be “a mother of nations” and kings (v. 16).

[18] In JST Genesis 17:4–7 there is evidence that Abraham understood baptism and that the ancient people had neglected to obey the covenant of baptism and had fallen into apostasy. They had strayed in “the washing of children, and the blood of sprinkling; and have said that the blood of the righteous Abel was shed for sins.”

[19] Bible Dictionary, “Abraham, Covenant of.”

[20] The idea of dismembering the body in a covenantal context was suggested to me in a discussion in September 2012 with anthropologist Dr. Stephen L. Olsen, the senior curator of the Church History Library in Salt Lake City.

[21] It is of interest that when Joshua crossed the river Jordan, the waters were “cut off” (Joshua 3:16) and the children of Israel “passed clean over Jordan” (v. 17). In the following chapter we read, “The waters of Jordan were cut off before the ark of the covenant” (4:7), and after the children of Israel passed through the waters, they were “circumcised” (5:2). In each of these verses, the Hebrew root k-r-t is used, with the idea of making, or cutting, a covenant in relation to the token of the Abrahamic covenant, which was signified by the cutting of the foreskin of all males who were of the seed of Abraham.

[22] Melvin J. Ballard, “Classic Discourses from the General Authorities: The Sacramental Covenant,” June 1949, www.lds.org/

[23] Study Bible, s.v. “yârêk,” https://

[24] The teaching of Abraham as God’s friend is also attested in the Islamic tradition. See Sūrah 4:25, in Ahmed Ali, Al-Qur’ān: A Contemporary Translation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993), 90.