The Book of Mormon and the Academy

Nicholas J. Frederick and Joseph M. Spencer

Nicholas J. Frederick and Joseph M. Spencer, "The Book of Mormon and the Academy," Religious Educator 21, no. 2 (2020): 171–92.

Nicholas J. Frederick (nick_frederick@byu.edu) and Joseph M. Spencer (joseph_spencer@byu.edu) were assistant professors of ancient scripture at BYU when this was written.

Editor’s note: This article in part of a recent series of conversations about religious education published in the Religious Educator. This article is less formal in tone and lacks traditional footnoting to avoid becoming a literature review. However, readers are welcome to contact the authors to follow up on any points discussed herein.

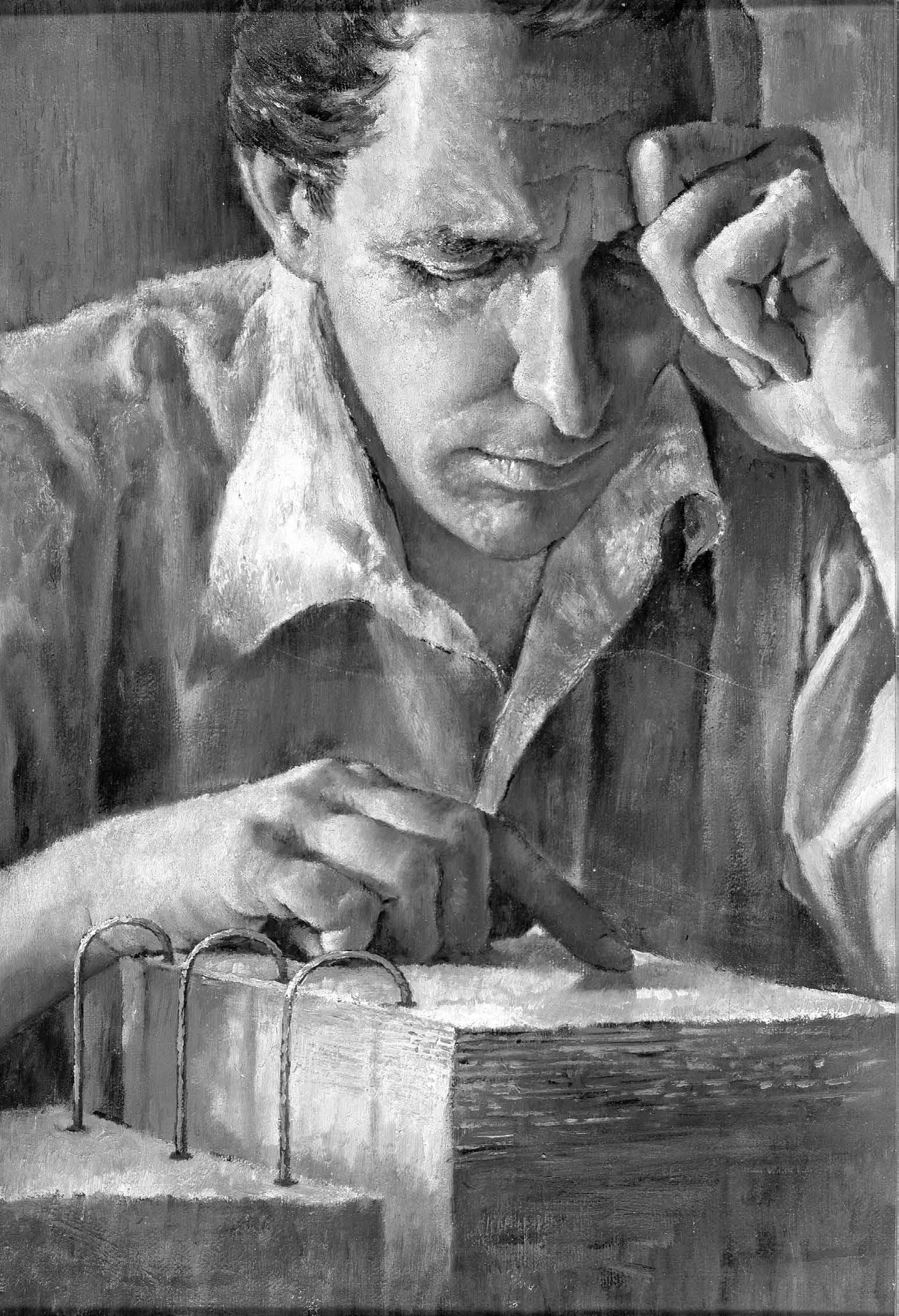

We needn’t and in fact mustn’t give up on the truth of the Book of Mormon—on its spiritual truth

We needn’t and in fact mustn’t give up on the truth of the Book of Mormon—on its spiritual truth

or on its historical truth.

It doesn’t take a lot of looking to see that something has changed—potentially for the better—about the scholarly world’s relationship to the Book of Mormon. Over the past twenty years, academic presses with no relationship to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have begun publishing serious and high-quality work on this sacred volume of scripture. Various journals have begun to do so as well. Several different scholarly editions of the Book of Mormon are now in print, and both the manuscripts for the Book of Mormon and the volume’s earliest historical editions are readily accessible. We have witnessed a dramatic rise in interest from scholars of other persuasions in writing on and publishing on the Book of Mormon, and the once-common dismissive spirit regarding the book in scholarly circles has begun to fade. For the first time, the Book of Mormon is being considered a legitimate object of inquiry by outside scholars. What do all these changes mean for the believing scholar who wishes to write about the Book of Mormon for as wide an audience as possible?

The recent developments just reviewed aren’t without their dangers, of course. Hugh Nibley used to argue that early Christians lost their way when they placed too high a priority on academic respectability. As with academic study of the Bible, the price of admission to join the academic conversation about the Book of Mormon is real. Disciples who takes their faith seriously must be careful as they decide whether—and why—they might want to walk through the door that now seems to stand open to them. Is it a door into the great and spacious building where there’s mostly mockery going on? Or is it an effectual door divinely opened to make the Book of Mormon known throughout the world? How possible is it really for a believer to write about the Book of Mormon for people outside the circle of believers without (directly or covertly) proselytizing for the Church? Can this be done faithfully, or must one concede too much and so compromise our sacred faith?

We, the authors of this essay, have ventured to enter the larger academic conversation about the Book of Mormon directly, but as fully committed Latter-day Saints. We’re both believers in the ancient historicity of the book and confessors of the divine inspiration that saturates its teachings. We’re also scholars who write at times in contexts where neither of those commitments is taken seriously. And so we sometimes find that we feel like we’re walking on a narrow beam, hoping to keep our balance. It isn’t hard to find common ground with nonbelieving academics whose interest in the Book of Mormon doesn’t begin from its truth. But if we limit ourselves to that common ground, do we risk affirming the faithlessness of our conversation partners? More importantly, do we risk compromising our own faith, conceding much to the secular position of our conversation partners while they concede little or nothing to our positions of faith? If we write in a tone acceptable to the academy, do our writings give Latter-day Saints the wrong impression that we don’t believe, encouraging secularity and faithlessness among those for whom we have direct and divine responsibility as religious educators?

These are, we’re fully aware, difficult questions. We’re laboring with the best of intentions—genuinely hoping to draw increased attention to the richness and depth of the Book of Mormon—but we’re also conscious of the possibility that we’re pursuing a thankless task. For the moment, though, our experiences encourage us that there’s much good to be done—that we can make friends for the faith, for the Church, and for our sacred scriptures. Cautiously, we press on in the hope that we aren’t wrong about that.

One consequence of the work we’ve undertaken is that we often write in a way that’s seen as somewhat different in tone and in topic from many who wrote before us. For example, our writings may seem strangely unconcerned with questions and problems that have often drawn the attention of those writing on the Book of Mormon. The fact is that occasion seldom arises in the course of writing this or that article to explain how we reconcile traditional difficult issues with faith. Especially as we write for other academics, it’s difficult to find space and time to address and reassure the Saints directly. We’d therefore like, in the following few pages, to claim some space to outline in a quasi-systematic fashion how we make sense of our own faith in the Book of Mormon. How do we hold our orthodox faith in the restored gospel of Jesus Christ with our intellectual commitment to the scholarly project? We’ll address nine issues connected to the Book of Mormon, one by one, before drawing out a few general conclusions. We don’t mean so much (or at all) to introduce novel approaches to the issues we’ll review here. We mean more to explain the lay of the land as it looks to us as we try to forge ways of talking about the Book of Mormon’s richness and depth to the larger academic world. To be clear, we aren’t saying that the ideas we’ll explore in the following sections are uniquely ours—only that they’re the theories and ideas we find most convincing and useful as we find our way in the academy. We are grateful to those who have gone before us. Hopefully, we can in some way return the favor and assist those who now contemplate how to balance their own faithful teaching or serious study of the Book of Mormon with the challenging questions and difficult topics that have emerged over the last decade or so.

The Process of Translation

Joseph Smith’s story about plates and an angel is a challenge—or even a scandal—to those outside the faith. This hasn’t changed with the rise of academic interest in the Book of Mormon. The simple fact that the angel took the plates away after their translation is an affront to anyone hoping to undertake an unbiased investigation into the Book of Mormon’s truth. Left only with an English text (and its various translations into other languages), how is one to determine the relationship between the Book of Mormon and the ancient origins it claims for itself? It calls itself a translation, but what does the word translation mean if the translated text can’t be compared to the original? There are questions here for the believing Latter-day Saint as much as for the outsider. Is there a tight correlation between the English text of the Book of Mormon and the characters inscribed on the gold plates? What exactly was Joseph Smith’s role in providing the English text of the book? Does the Book of Mormon reflect only the voices of its ancient and original authors, or does it also reflect the voice of its modern translator?

Two contrasting positions have emerged among believing Book of Mormon scholars in response to these questions. Both have developed in response to criticisms of the Book of Mormon. One holds that Joseph Smith was given the very words he dictated to his scribes, that he didn’t directly inform the shape or diction of the translation. Another holds that the Prophet was given impressions rather than words and that he had to decide what words to use in giving shape to impressions. (And some argue for a hybrid of the two.) The former position makes better sense of the eyewitness descriptions of the translation process, while the latter position seems better able to account for aspects of the text that might appear more modern than ancient. Whichever position one espouses, one has some explaining to do. Those who argue for “tight control” (the Prophet had the text simply given to him) thus sometimes set forth speculative theories about who the real translator of the text was. Those who argue for “loose control” (the Prophet played a key role in shaping the text) have outlined equally speculative theories about how the mind interacts with a seer stone.

Of course, to scholars working outside the Latter-day Saint tradition, this debate is moot. Rejecting the idea that Joseph Smith had a prophetic gift and rejecting the existence of a new-world Israelite people who created gold plates, such scholars simply assume the Book of Mormon had its origins in the nineteenth century. Thus the conversation about how much the Book of Mormon reflects ancient sources or a nineteenth-century American perspective—while intense and of obvious interest to believers—remains insider talk. In our own work, therefore, we haven’t taken an overt position on this debate, preferring to write simply and exclusively about the English text of the Book of Mormon rather than the relationship between the English text and the gold plates. We, of course, believe that there were gold plates delivered to Joseph Smith by Moroni, but we’re unsure how much can constructively be done in trying to prove or disprove the divine origins of the plates. There’s plenty of work to do just in trying to understand the text God has given the modern world, regardless of what other work can be done trying to decide how much the respective environments of original production and ultimate translation shape the text we know.

But this doesn’t mean that we’re without opinions on the nature of the translation. For our part, we incline toward “tight control,” which for us represents the position that Joseph Smith had little or no influence on the shape of the Book of Mormon. What we have today with the English Book of Mormon represents what God wanted us to have; the Prophet’s primary role was as a transmitter of that text. This doesn’t mean that the text is foreign to the nineteenth-century context in which it appeared, though. It means only that we’re unconvinced that whatever smacks of the nineteenth century (or, for some, the seventeenth century) in the Book of Mormon was the Prophet’s rather than God’s contribution. In fact, we find deep and devotional comfort in the idea that God wished to ensure that an ancient text would have real purchase in the context of its latter-day appearance. We marvel at God’s gift and power evident in the coming forth of the Book of Mormon, and we marvel at God’s love and mercy manifested in the words he gave to his prophet so that he could give them to the world. In our view, the Book of Mormon as God gave it to Joseph Smith through divine means refuses to remain trapped in the ancient world where it originated. Instead, it makes its relevance to the modern world evident in the English text that is our subject of study.

Changes to the Text

As Joseph Smith dictated the Book of Mormon to his scribes, they took down dictation on what would come to be called the “original manuscript.” As translation ended and printing began, the Prophet assigned Oliver Cowdery to copy the manuscript and create a “printer’s manuscript” that could be used for production while the original was kept safe. Although much of the original manuscript no longer exists, the fragments that do can be compared with the printer’s manuscript, and there are interesting differences between the two—some suggesting simple errors on the copyist’s part, others that Cowdery struggled to read the original, and still others that there were transcription errors in the original that needed correcting. Even before the Book of Mormon saw its way into print, then, there were already minor difficulties in deciding on the exact text of the book.

Four editions of the Book of Mormon appeared during Joseph Smith’s lifetime—all under his authority but three under his close supervision. The first, of course, appeared in 1830 in Palmyra, New York, set by John Gilbert largely (but not entirely) from the printer’s manuscript. Gilbert introduced punctuation but also—occasionally by mistake but at times intentionally—other variants into the text. The second edition appeared in Kirtland, Ohio, in 1837, set anew from the same printer’s manuscript. Oliver Cowdery had primary responsibility for printing this edition, but not before Joseph Smith himself directly revised the printer’s manuscript. The Prophet made over a thousand changes, most linked to fixing grammar or updating archaic language. A few changes could be viewed as doctrinally significant, however, such as changing “God” to “Son of God” in 1 Nephi 11:18. The Church then issued a third edition in 1840 in Nauvoo, Illinois, with Don Carlos Smith (the Prophet’s brother) and Ebenezer Robinson as the printers. This edition included further corrections and clarifications, such as a shift from “a white and a delightsome people” to “a pure and a delightsome people” in 2 Nephi 30:6. For this edition, the original manuscript was clearly consulted and certain errors in previous editions corrected. Finally, a fourth edition appeared in 1841, published in Liverpool, England, and largely reproduced from the 1837 second edition.

The question for faithful readers of the Book of Mormon in all this is how to understand Joseph Smith’s constant efforts at revising the text of the book. If the words of the Book of Mormon were granted by the gift and power of God and correctly written down by scribes, isn’t the earliest or original text what God wants us to have in the book? Why change it? And what of the Prophet’s famous statement that the Book of Mormon is “the most correct of any book”?[1]

Maybe the overwhelming majority of the changes had to do with grammar, but why shouldn’t God have given a grammatically flawless text to the Prophet in the first place? And isn’t it especially concerning that some changes appear to alter doctrinal content?

In our view, these questions all arise only if one first favors a specific notion of what it means for Joseph Smith to have been a prophet. Even as we favor a “tight control” model for translation, we recognize that the Prophet felt—and rightly felt—a proprietorship over the text of the Book of Mormon. That is, the changes he made to the Book of Mormon suggest that one of the responsibilities he had as prophet was to make the text accessible, modern in its English, and clear in its doctrine. But we insist that it’s wholly inaccurate to suggest that the revisions Joseph Smith made amounted to substantive changes. One idea lay behind all the revisions: to remove obstacles to reading and understanding the text originally given him. The revisions are extremely conservative. This comes out with real clarity when they’re set side by side with revisions the Prophet made to the revelations in the Doctrine and Covenants or with the revisions the Prophet made to the Bible, which are dramatic and theologically significant. And so, in our eyes, it’s a mistake to believe that “most correct” implies something about the inerrancy or perfect clarity of every word, phrase, or punctuation mark in the Book of Mormon. The tension in Joseph Smith’s editorial method was between modernizing or clarifying the text and leaving the historical and theological teachings of the book untouched. To us, it looks like the Prophet did his work rather well as he balanced competing loyalties.

Alleged Modern Sources

Once the Book of Mormon was in print, it attracted the direct attention of critics, and that hasn’t abated. One consistent form of critique has been to argue that Joseph Smith was influenced by contemporary texts. The so-called Solomon Spaulding manuscript provided a narrative framework that the Prophet could easily adopt. Ethan Smith’s View of the Hebrews may have offered ideas to him about connections between Israelites and Native American origins. Gilbert Hunt’s The Late War between the United States and Great Britain could have been a catalyst for writing an American history in biblical language. The first of these three alleged influences on the Book of Mormon drew extensive attention in the nineteenth century. The second drew much attention in the twentieth century. The third has begun to draw attention only in the twenty-first century.

The earliest theory asserts that Joseph Smith plagiarized the Book of Mormon from a manuscript written by Solomon Spaulding and passed to Joseph Smith by Sidney Rigdon (who supposedly came into possession of the manuscript in Pittsburgh). Like the Book of Mormon, Spaulding’s tale centered on a group of refugees (Roman in Spaulding’s story) who landed in the Americas and interacted with different native tribes. Although no one could locate a copy of Spaulding’s manuscript, several individuals swore affidavits that the Spaulding Manuscript and the Book of Mormon overlapped in several places—including names of characters and major plot points. In 1884, though, Spaulding’s actual manuscript was discovered, making clear that, except at the broadest and therefore irrelevant level, the two manuscripts shared nothing in common. Apart from a few hobbyists, critics therefore ceased to espouse the Spaulding theory. At about the same time, though, critics turned to View of the Hebrews as a possible source text. In 1823, Ethan Smith, a Congregationalist pastor from Vermont, published a well-received book arguing that native Americans descended from the lost tribes of Israel. Parallels between View of the Hebrews and the Book of Mormon are far more compelling than those between Spaulding’s manuscript and the Book of Mormon. B. H. Roberts, a believing leader in the first half of the twentieth century, famously wrestled long and perhaps inconclusively with parallels he found between the two books. Even in this case, though, the parallels are too broad to justify any theory of actual dependence, and the differences in conception are striking and important.

A newer theory, similarly motivated, has emerged in just the last few years. The Late War plays in the most recent attempt to discover a secular origin for the Book of Mormon. This book, written in 1816 by Gilbert J. Hunt, is an attempt at a history of the War of 1812 in biblical style, representative of a whole genre of pseudo-biblical histories popular in the United States around the beginning of the nineteenth century. Because the book uses phrases such as “and it came to pass,” alludes to “freemen” and “kingmen,” includes a possible chiasm, narrates the building of a ship, and relays a story of “two thousand hardy men” who fight against King George III, some have argued that Joseph Smith read The Late War in school and (consciously or even unconsciously) modeled the Book of Mormon after it. As with View of the Hebrews, many of these parallels are broad or general ones dealing with a similar topic (war), and similarities in language are likely due to both books having a biblical style, that of the King James Version.

Although these alleged secular sources for the Book of Mormon have drawn attention from critics and defenders of our sacred scripture, they simply haven’t felt compelling enough to us to give them serious heed. In general, they also haven’t drawn the attention of outsider academics whose interest in the Book of Mormon has grown. Maybe the existence of works relevantly similar to the Book of Mormon in the decades leading up to 1830 seems suspicious. But, unless direct dependence can be demonstrated, why shouldn’t the believer hold that such works providentially served to prepare a ready audience for the new scripture? And in the meanwhile, establishing actual literary dependence is exceedingly difficult. All the theories regarding possible sources for a plagiarized Book of Mormon remain a good distance from actually establishing literary dependence. At most, they suggest that certain ideas and certain biblical turns of phrase were in the air. But that’s no surprise. The Book of Mormon came forth when travel romances were popular and investigations into the origins of the Native Americans were topics of conversation. It’s a narrative history and so has themes and tropes similar to other works of narrative history. All of these works do have a shared literary source on which they depend, and that’s what seems to put them on comparable terrain. They all share a debt to the King James Version of the Bible. But to say much more than that, we feel, is to say more than the evidence warrants.

Anachronisms in the Text

Other long-standing critiques of the Book of Mormon concern elements of the narrative that might seem to fit better into the nineteenth-century context of the book’s appearance than in the ancient world. Still others focus attention on parts of the narrative that, according to the best of our current scientific knowledge, wouldn’t fit in pre-Columbian America (but someone like Joseph Smith might have naturally believed would fit). These two sorts of critiques thus concern anachronisms, things out of place in the time the text claims to describe. And so critics point to the Book of Mormon’s references to steel and silk, or to horses and elephants. Or they point to things like (relatively) democratic ideas or ideals, strongly racializing language, or religious questions of particular concern in pre–Civil War American culture. (We leave for the next two sections certain more specific accusations regarding anachronism—the presence of certain biblical texts in the Book of Mormon.) Don’t these kinds of things suggest origins in the nineteenth century? It’s certainly true that these are harder to explain away than any of the supposed problems we’ve surveyed in the previous three sections.

But we have to confess that these difficulties—all addressed in various ways by defenders of the Book of Mormon’s historicity—don’t draw or hold our attention often or for long. They aren’t at all unimportant, but anachronisms are something one should naturally expect from any good or useful translation. The Book of Mormon, as we’ve already suggested, doesn’t purport to be a scientifically accurate, word-for-word translation of a text written in and for an ancient context. The claim the book makes for itself is that it’s a translation, by the gift and power of God, of what a few men wrote anciently whose eyes were squarely focused on the last days. Prophecy is itself anachronistic, out of sync with the time of its utterance. And then, of course, translation is also an anachronistic enterprise, a re-presentation of things native to one context within a wholly different context, alienated from its proper time as it comes to inhabit another time. If the Book of Mormon weren’t anachronistic in certain ways, it would be unintelligible to its modern readers. And also, if it weren’t anachronistic in a truly deep sense, it wouldn’t be prophetic, prepared to call the whole world to repentance in the last days.

Of course, this or that particular anachronism might well get under our skin, and there’s certainly reason to work up some explanation of it. From our perspective, however, what’s most important about addressing any particular anachronism in the Book of Mormon is to understand it, to make sense of the passage or context in which it appears. And we feel that there will be—perhaps there must be—instances where anachronisms will be unexplainable to our satisfaction. It would be foolhardy to think that we’ll be able to exhaust the meaning of a text as rich as the Book of Mormon. We trust it’s necessary occasionally to have to sit patiently and faithfully, living with a bit of mystery, refusing to let lingering concerns distract us from what matters infinitely more than a few unanswered questions of detail. Anachronisms aren’t unimportant, but they aren’t as important as the saving truths that call for deep and sustained analysis. To us, it’s somewhat puzzling that we’ve collectively given more intellectual effort to explaining potentially anachronistic elements in the book than we have to really riddling out the volume’s covenant theology (to take one example), which Moroni in the Book of Mormon title page asks us to consider deeply. We are most appreciative for the work that has been done to explain potential anachronisms, and we recognize that this is a very legitimate issue for some who struggle to subscribe to the Book of Mormon’s historicity. We’re also eager to see other kinds of work on the Book of Mormon move forward.

In our own work, therefore, we’ve tended to say little about potentially anachronistic elements of the Book of Mormon’s text. It doesn’t seem wise to pretend they aren’t there, but it also doesn’t seem wise to work up premature responses to them. In short, it doesn’t seem wise to give them any more attention than they do, rightly, deserve. The truth of the Book of Mormon doesn’t depend on there being an answer to every item in a long list of potential problems with the book. It depends on there being a theological framework in the book that might convince us to come to Christ and take up his work. What we believe has to be done before we can grasp the fullness of the Book of Mormon’s teachings is to make sense of how the book operates—its structures, its literary style, its complex as well as its simple message. That is work we’ve committed ourselves to pursuing while leaving to others to sort out answers to questions about potentially anachronistic elements of the text.

Isaiah in the Book of Mormon

Two potential anachronisms in the Book of Mormon, however, have drawn a special sort of attention, and they’re of more direct interest to us. The first concerns Isaiah. The past century and a half has seen a consensus emerge among biblical scholars that the Book of Isaiah weaves together writings that originated in three dramatically different periods of Israel’s history. The first set of writings are generally believed to go back to Isaiah of Jerusalem, who wrote during the eighth century before Christ. The second and third sets of writings, however, are believed to have originated more than a century later than Isaiah’s own lifetime and to have been appended to the collection of Isaiah’s writings long after his death. Isaiah scholars debate the details, but the vast majority agree on the general picture. It’s important to note that there are Isaiah scholars who take a dissenting position, but nearly all who do begin from conservative Christian theological assumptions about biblical inerrancy (that is, about the Bible being wholly without error because it’s God’s word).

All this poses difficulties for the Book of Mormon because Nephi quotes from certain supposedly later portions of the book of Isaiah. According to the Book of Mormon, Nephi and his family left Jerusalem with the brass plates (Nephi’s source for Isaiah) at the beginning of the sixth century before Christ. At least parts of what he quotes from Isaiah, however, are generally believed to have been written no earlier than a few decades into the sixth century—and certain other parts still later. Even the parts of Isaiah Nephi quotes that definitely originated earlier, it’s often argued, only received the shape they have in the Book of Mormon rather late, decades after Nephi’s family would have left for the promised land. Consensus scholarship thus suggests that there’s something anachronistic about the Book of Mormon’s quotations of Isaiah. This difficulty has long been recognized by Latter-day Saint scholars, who have been writing about it since the 1930s.

Some, too eager to solve this potential problem for the Book of Mormon quickly, have suggested that biblical scholars come to their conclusions simply because they don’t believe in real (predictive) prophecy. This grossly oversimplifies matters, however. It’s true that biblical scholars—really, scholars of all kinds—are too quick to draw secularizing conclusions without having sifted all the evidence, but there are various kinds of evidence that lead scholars to their conclusions regarding authorship. And anyway, it’s foolhardy to insist that the conclusions of biblical scholarship result solely or even primarily from the scholars’ worldview. Worldviews always play a role in scholarship, to be sure, but so does evidence, and it’s the evidence that needs to be dealt with. To show that Isaiah passages quoted in the Book of Mormon existed in their final form by the time Nephi acquired the brass plates, it would be necessary to engage directly and convincingly with the evidence for the dating discussed by Isaiah scholars.

For our part, we feel that the question of whether the Book of Mormon’s uses of Isaiah are decidedly anachronistic hasn’t yet been asked earnestly. It isn’t enough for critics to point to scholarly consensus to establish that the Book of Mormon stumbles on this point. Consensus changes, and it always has blind spots. But it also isn’t enough for defenders of the Book of Mormon’s antiquity to line up scattered points of evidence regarding the single authorship of Isaiah or to cast aspersions on the motivations of biblical scholars. The fact is that no Isaiah scholar has yet fully put to the test the hypothesis that all the parts of Isaiah quoted in the Book of Mormon (and no more) had their final form by the beginning of the sixth century before Christ. Scholars of other persuasions have no motivation to pursue this hypothesis, and Latter-day Saint scholars with relevant training haven’t given sufficient attention directly to this question to decide it. Nothing definitive—certainly nothing definitive enough to risk one’s faith commitments on—has yet appeared in answer to such questions. It would be wonderful to see this issue receive the most serious treatment possible. For the moment, that hasn’t happened, and so every conclusion drawn is premature.

Further, though, it’s simply unclear just how important it would actually be to show that every Isaiah passage quoted in the Book of Mormon had been authored and given final shape by Nephi’s day. Perhaps God wished modern readers of the Book of Mormon to have a fuller Isaiah text than was available to Nephi on the brass plates. Because we don’t have access to the gold plates from which the Book of Mormon was translated or the brass plates from which Nephi claims to have drawn his Isaiah text, we don’t know how exactly the English text of the Book of Mormon is meant to reproduce the ancient sources. From our perspective, then, it seems more than a little overhasty for a believer to decide against the Book of Mormon’s truth because of its uses of Isaiah. To the contrary, the brilliance of Nephi’s interaction with Isaiah’s prophecies—the careful program of Nephi’s interpretations of Isaiah—is a substantial reason to give the book the benefit of the doubt. We find prophetic inspiration all throughout the Book of Mormon’s work with Isaiah, and that’s received too little attention so far. While we’re waiting for further and decisive work on the historical issues, we’re happy to give our time to sorting out what the Book of Mormon actually does with the writings of Isaiah.

Dependence on the New Testament

A second potential anachronism worthy of special note is the Book of Mormon’s use of language reminiscent of the King James New Testament. New Testament language is, in fact, substantially more present in the text than is often recognized. Some suggest that this is a threat to the Book of Mormon’s historicity. How could a book with origins in a 600 BC migration from Jerusalem to the Americas contain passages from the standard nineteenth-century English translation of the New Testament? Phrases from the Old Testament might be expected, since the Nephites possessed some version of writings known in the Old Testament. But the presence of language from, say, the Gospel of John in 1 Nephi 10 is more difficult to understand. Naturally, as with all criticisms of Book of Mormon historicity, there are various ways this issue has been dealt with.

The most traditional approach has been to argue (or at least to assume) that New Testament language appears in the Book of Mormon because that’s what was inscribed on the gold plates by its ancient authors. On this view, there’s no direct dependence of the Book of Mormon on the New Testament. The two have similar language because God reveals the same things from one generation to another. A slight variation on this view might be the idea that the ancient authors of the Book of Mormon were given, through divine experiences, to know the language of the New Testament and to use it in their writings. Nephite prophets occasionally explain that they saw the last days and had a message directly intended for those living in a late Christian context. Yet another slight variation would be the idea that Book of Mormon authors and New Testament authors had access to similarly worded texts that aren’t extant today, older traditions that played a role in their composition. What unites all of these first approaches is that they take the text to be (as much as possible) a word-for-word translation of the gold plates, which already had what we would today recognize as New Testament language in it.

Another set of approaches has gained ascendancy in recent years. Even as these newer approaches insist on the existence of ancient gold plates and some correlation between the plates and the English text of the Book of Mormon, they allow for a looser notion of translation, suggesting that the English text might take certain liberties with the underlying gold-plates text. That is, these approaches take the Book of Mormon’s English text as introducing New Testament language into a text that wasn’t originally worded that way. Again, to translate needn’t be to produce a slavish reproduction of content in one language into another; it can also be to couch the content of the original in language and imagery more familiar to the target audience. As we’ve noted, some understand a looser translation like this to be the product of Joseph Smith’s own involvement, whether larger or smaller, in producing the English text. Others take it to be the work of some divine being—God or an angel—before the English words’ appearance on the seer stone the Prophet read from. Either way, those who embrace this looser notion of translation tend to see a variety of reasons for a less literal translation. New Testament language makes the Book of Mormon more intelligible to a latter-day (and largely Christian) audience. It also lends rhetorical authority to the Book of Mormon, allowing it to speak in the voice of authoritative scripture.

All these theories are interesting, and all seem possible. For our part, the one that makes the most sense is the last one mentioned—that there’s no need for the Book of Mormon to be as literal a translation as possible of the gold plates and that God or an angel provided the text that would speak to the nineteenth century and beyond most forcefully. This makes the best sense of evidence showing that the Prophet read from the seer stone, and it allows ample room for God to ensure that the text of the Book of Mormon would speak directly to its intended latter-day audience. For our part, we find it frankly reassuring to think that the text we have today is what God wanted us to have. Indeed, we take the familiarity and availability of the English text of the Book of Mormon to be a sign of God’s intense love and mercy for us as readers. He could have arranged for a technically accurate translation of a deeply foreign record. Instead, God worked to give us a book that could speak directly to us in the last days. It’s as the translation of the book is adapted to the weakness and the language of its readers that it does its marvelous work.

Apologetics as an Enterprise

The preceding sections all deal with what might be called traditional criticisms of the Book of Mormon. Those who set out to demonstrate that the Book of Mormon was the product of Joseph Smith’s own mind—or the mind of one of his associates—tend to take up one of these questions. (So too, of course, do those who set out to demonstrate that the Book of Mormon is divine, though obviously with a different aim!) What’s peculiar about how the English text of the Book of Mormon was produced in the first place or about how that text has been changed from edition to edition? Can one identify modern sources or other anachronistic elements in the text that might betray nineteenth-century origins? Are there clear difficulties deriving from the presence of biblical texts in the volume, whether those explicitly identified (like Isaiah) or those simply alluded to (especially New Testament texts)? These are old questions, and critics of the Book of Mormon have, for the most part, given them the same answers for a very long time. There’s seldom (but not never!) anything new under the sun that shines on Book of Mormon historicity, whether for or against. We watch with great interest for emerging new angles on these questions and read with eagerness responses from believing scholars to criticisms. But there’s much work to do in the meanwhile that often threatens to go undone. This is one reason we, the two authors of this article, don’t ourselves address these traditional concerns in our own work. Returning again and again to the issue of Book of Mormon historicity can feel like starting a car over and over again to prove that it runs but putting it in drive only once in a long while to see what it can do. For our part, we’re convinced that the car runs. Further demonstrations of (or questions raised about) that fact are interesting, but we want to know what it feels like to drive it.

This might sound like a wholesale dismissal of apologetics—that is, of the task of rationally defending one’s faith commitments. In our view, though, it isn’t that at all. In fact, we worry that it’s precisely an obsessive concern over the one question of historicity that threatens to compromise the apologetic task. If the work of apologists addresses this one question only, then the Book of Mormon’s truth as we defend it is too narrow. We want a book that’s true not only in that it’s historical (though that’s obviously important). We want a book that’s true in a hundred other ways also and in ways that matter to us on an existential (and not just an intellectual) level. Our experience leads us to believe that that’s what many or even most readers of the Book of Mormon want as well. Readers today are as likely—if not, in fact, more likely—to reject the Book of Mormon for reasons that have nothing to do with historicity: because it seems irrelevant, archaic, boring, clichéd, unenlightening, or troubling. A number of students come into our classes fully convinced that the Book of Mormon is ancient but seem unconvinced that they have more to learn from it.

For us, then, the apologetic enterprise needs to give as much attention to questions of deep social relevance, contemporary interest, and demonstrations of spiritual force as to questions of historicity. Indeed, while we wholly understand that (and why) others see this differently, we’re convinced that it needs to give a good deal more attention to these questions than to questions of historicity. The situation was certainly different a generation or two ago, as we fully recognize. But today, we sometimes find ourselves wondering what a person is profited if they gain the historical place of the Book of Mormon in the world but loses the soul of the book. From our perspective, then, a contemporary task of Book of Mormon apologetics is to find the soul of the book, its bearing and significance. It’s to help to articulate intellectually defensible reasons why we do and should place the Book of Mormon at the very heart of our collective devotion to the God of the Restoration. Scholars working before us have done important work on these questions, to be sure, and we strive to build on their work. But where their work was, in the twentieth century, often at the margins of academic study of the Book of Mormon, it seems that it could be at the center of such study today. Because of the intellectual needs we’ve had in the past, we sometimes, as a people, treat the Book of Mormon as if it were theologically uninteresting—more a historically defensible bit of evidence for the larger Restoration’s truth than an occasion for devoted thought or action. We’re convinced, though, that the Book of Mormon can take all the theological pressure we can put on it, and we want to see what that looks like more consistently and more publicly than has been done in the past.

Now, apologists working to set the Book of Mormon in the ancient world have been astonishingly creative in their efforts. They’ve scoured the records of the human race, sifted through the sands of ancient civilizations, mastered dozens of potentially relevant languages, and discerned new ways of reading texts from within the Book of Mormon. The monument to the Book of Mormon they’ve built is a wonder, breathtaking in its scope. But now, we believe, we need to muster exactly the kind of commitment and ingenuity the apologists before us have put into just one question regarding the Book of Mormon’s truth. And we’ve got to put that commitment and ingenuity into a host of other questions regarding the book’s truth. If we had a small army of trained theologians, philosophers, textual critics, and social critics, all working as hard on the Book of Mormon as those trained in ancient history have worked before us, what might emerge from their effort and inventiveness? And how many souls, growing bored with a text they feel they’ve exhausted, might be saved as their fire for the Book of Mormon is rekindled? The apologetic enterprise isn’t at an end. It’s at a crossroads, a moment of expansion and deepening that may well help to make the Book of Mormon still more central to our faith. What was arguably treated as secondary work before must become primary today, and precisely for apologetic reasons. And so we might turn next to providing outlines of how we might respond to questions deserving of renewed and deepened apologetic attention.

Questions of Race

Recent years have seen a noticeable uptick in the frequency of publications on race in the Book of Mormon. The fact of the matter is that, however one tries to make sense of individual passages that are (or at least appear to be) about race, they look deeply problematic through twenty-first-century eyes. Many discussions on the topic boil down to asking how to interpret references in 2 Nephi 5 to a “mark” and a “curse” being placed on the Lamanites. Statements by Church leaders have tended to try to soften the correlation between the imposition of a “curse” and the text’s talk of a “skin of blackness” while still leaving space for literal interpretation. And so, in the minds of most believing readers, the Book of Mormon’s references to “black” and “white” skin are generally taken to be literal, referring to pigmentation: the Nephites physically possess light, “white” skin, and the Lamanites physically possess a dark or “black” skin. Readers perhaps most commonly imagine Laman and Lemuel as being initially white but then becoming dark after the Lord enacts a demonstrative change.

Of course, the existence of differently colored peoples would not in and of itself be a problem, especially if they were to live in harmony, appreciative of any differences among them. But various passages in the Book of Mormon seem straightforwardly to tie skin color to certain cultural and spiritual values, and dark skin is associated with striking frequency with spiritually negative values—many of them tied to classically racist and racializing tropes about things like laziness and savagery. In addition, certain passages suggest that dark-skinned individuals who come to Christ lose their dark skin and acquire white skin, suggesting that whiteness is a kind of moral standard for the Book of Mormon. These passages are troubling to believers who follow modern prophets in denouncing racism, and they’re often taken by twenty-first-century readers to be clear indications that the Book of Mormon had its origins in the nineteenth century’s racially charged atmosphere but also that they’re clear indications that the book is morally dangerous and uninspired.

Various approaches to these issues have been taken by believing and unbelieving readers of the Book of Mormon. Historical or even anthropological approaches have argued that the texts can be explained in terms of Lamanite intermarriage with other ancient American peoples hailing from different parts of the world, coupled with classic Nephite distrust of an outsider group. This approach is interesting, although it has to be said that it leaves the Nephites (especially and including their prophets, who write the troubling passages) in an ethically compromised position. Rather different readers have argued that the words “white” and “black” aren’t used to refer to skin colors in any literal sense; instead, they’re used symbolically as in many ancient cultures, to refer to what’s valued as good or righteous over against what’s disvalued as evil or wicked. This seems to remove literal questions of race, but some respond to this approach that it problematically leaves “whiteness” in a normative position, still the standard by which “blackness” is measured and found wanting. Still other approaches explore the possibility that what’s “white” and “black” in the text is clothing, animal “skins” rather than human flesh.

We’re ourselves disinclined toward symbolic approaches of these last several sorts, except in certain texts where the words “white” or “dark” are clearly used metaphorically (as in Jacob 3:8–10 or 3 Nephi 19:24–25). Even in those passages, the fact that whiteness becomes a standard remains problematic from a twenty-first-century perspective. In most passages, it seems clear to us that “white” and “black” indeed refer to skin pigmentation, so there really are serious and difficult race problems within the Book of Mormon. In our view, however, this makes the Book of Mormon more rather than less relevant to the twenty-first century. The book shows us what it looks like when a people develops systemic racism, with Nephites rejecting Lamanites simply because of the color of their skin (something at least a few Nephite prophets directly point out and criticize—most especially Jacob). What we’re reading when we read the Book of Mormon is a long and deeply relevant history of wickedness that ultimately ends in destruction, while the racially out-of-favor are slowly revealed to be a chosen and preserved people. The last prophet, Mormon, asks us to hear at length a dark-skinned prophet, the remarkable Samuel—who’s strikingly underappreciated in our collective reading. Along with some other recent readers, then, we find in the Book of Mormon a richly cautionary tale regarding racism and racialism. The book invites us to recognize, with the Nephite prophets at their most clear-sighted moments, that God invites all to come to him, “black or white” (2 Nephi 26:33). This is a book that might well teach us about racism and racialization, if we’re open to asking it to show us the consequences of such things.

The Status of Gender

Also of deep concern to many readers of the Book of Mormon in the twenty-first century is the book’s apparent lack of interest in female characters. Already in the 1970s, but then especially in the 1980s and 1990s, there began to appear articles and book chapters asking about how few women with names—or even nameless women of real substance—appear in the Book of Mormon. Nephite scripture feels to many like a book written by and for men. Some suggest that this is a feature of its being a premodern book, a text with origins before the rise of modern feminism. Unfortunately, though, this doesn’t really work as a moral defense of the Book of Mormon because the Bible—an equally ancient book that provided the cultural context out of which Book of Mormon peoples originated—pays much more attention to women than the Book of Mormon does. Because certain Book of Mormon prophets explicitly claim to have seen the last days, one might in fact expect them to be more aware of their latter-day female readers and so to be readier than their biblical contemporaries to write about women. But readers of the Bible find much more material on women to work with, as the remarkably robust field of feminist biblical scholarship shows.

How, then, might one make sense of the situation women face in the Book of Mormon? And how, especially, is one to affirm the book as rich and inspired scripture in an age of increasing emancipation for women? We confess that, being both of us men, we tremble at the task of answering that question. We nonetheless find reason to find hope for women in the Book of Mormon if the book is read carefully. This isn’t to say that the few stories the book offers contain such rich portrayals that they make up for the absence of women elsewhere in the volume. No, it’s rather to say that there’s a much more complicated presentation of questions concerning gender in the Book of Mormon than is usually recognized, and it’s the larger pattern of where and how women appear in the Book of Mormon that might provide careful readers with hope. The vast majority of what has been written on women in the Book of Mormon ignores the larger patterns, moving too quickly to either a critical or a defensive extreme. But we find in the text something more compelling.

When Jacob stands before his people shortly after Nephi’s death, he quotes at length from Lehi and claims that one of the principal reasons for the colony’s removal from Jerusalem and relocation in the promised land was to make possible the transformation of an oppressive sexual culture that existed in the Old World. Women throughout Israel were suffering because of men’s wickedness. This might be overcome in the New World, if Lehi and Sariah’s children would work against the sexual oppression of women. Jacob goes on to condemn Nephite men for their oppression of women, and he predicts dire consequences—utter destruction—if they don’t repent of their actions and their ongoing patterns of action. And then Jacob claims that Lamanite men haven’t given themselves to the same oppressive sins as Nephite men, and that there is instead a rich kind of family life among the Lamanites that was lacking among the Nephites. He explicitly states that it’s because of Lamanite relations between the sexes that they would be preserved to become a righteous people one day.

One might guess at first that Jacob’s words were applicable only to his own time, but they describe perfectly the patterns of Nephite and Lamanite culture throughout the whole of the Book of Mormon. Women consistently fare poorly in Nephite culture or among Nephite men. Nephite history is in fact one long disaster for women, with numerous stories of violence toward and suffering for women (kidnapping, forced marriages, murder, abuse, and rape). By contrast, the few glimpses readers have of Lamanite society in the Book of Mormon consistently reveal a culture without the oppressions visible among the Nephites. Female hero figures like Abish and Lamoni’s queen or the mothers of the stripling warriors are found only among the Lamanites. And, true to what Jacob prophesies, the Nephites are utterly destroyed, and the Lamanites are preserved. All this suggests that the Book of Mormon isn’t meant to illustrate a righteous culture among the Nephites but a disastrous one—a culture that leads to the oppression of women and that therefore ultimately leads to the whole collapse of that society. The preserved Lamanites, with promises of full restoration in the last days, find themselves poised for redemption because of how women fare among them in the text. It seems the Book of Mormon has a conscious and deeply relevant message regarding women and men, something of potential importance for the twenty-first century.

Conclusion

In 1869, the first transcontinental railroad in the United States was completed. For two decades, the Saints in and around Utah had been largely able to create their own culture and to live as they wished. There had been enemies in their midst, of course, and outsiders often enough came through and raised uncomfortable questions to which the Saints had to create good answers. But with the completion of the railroad, a new era dawned. The buffer between the Saints and the rest of the United States disappeared, and it became necessary to conceive of new strategies for interacting with people who quickly became neighbors instead of enemies. Members of the Church had to create new forms of discourse, new ways of talking about their faith that would allow them to get along with other Americans without compromising their commitments to the faith of their pioneer mothers and fathers.

Something like a transcontinental railroad has been completed in the last two decades, one that connects traditional study of the Book of Mormon to the larger scholarly world. We might react to this development in any variety of ways, but the fact of the matter is that young members of the Church are increasingly familiar with what’s at the other end of that railroad—as familiar with all that as they are with the Book of Mormon at this end of the same set of tracks. The way we study the Book of Mormon when we do our most serious intellectual work on it will change, and we have to decide what that change will look like. We needn’t and in fact mustn’t give up on the truth of the Book of Mormon—on its spiritual truth or on its historical truth. But how we talk about and defend that truth is already changing. Some questions that seemed pressing just a few years ago seem less pressing today, while questions that didn’t seem terribly important just a few years ago seem crucial today.

In these few pages, we have tried to outline what it means for us, we two who are writing this article, to be regular passengers on the train that goes back and forth between the academy and traditional study of the Book of Mormon. We haven’t tried to provide a final word on these matters. Far from it! If anything, we’re trying to speak just a first word, to announce that the situation looks different today, and to ask for some understanding as we come to know the contours of the altered terrain. And we’re hoping, with others, to sound an invitation to other deeply faithful scholars to find their way to the station platform. Come and help us and others figure out how this dawning project will work—in full fidelity to the Restoration and with total rigor academically, by study and by faith. There are many empty seats on the train, and we’d love the company. What we’ve said here is simply our story, the expression of how we’ve navigated our way through the Book of Mormon’s history and text. We would love to hear how others have taken similar (or perhaps very different) journeys.

In the meanwhile, it’s our witness and testimony that the Book of Mormon is true, historically and theologically. It’s a book that doesn’t need to be handled delicately or kept on the shelf. It needs, rather, to be studied. Study always involves risk. But we’re convinced, for the moment, that the risk is worth it. There’s much to be gained, including the confidence of our youth. There’s much to be lost as well, and so we’re trying to be cautious, eyes peeled and always aware. We know we’ll make mistakes. But so long as we carry an unshakable conviction of the unswerving truth of the Restoration with us, we trust that God will go with us. We’re still in the midst of the divine coming forth of the Book of Mormon. Let’s pray that this is another important stage of that marvelous work and a wonder.

Notes

[1] “History, 1838–1856, volume C-1 [2 November 1838–31 July 1842],” 1255, The Joseph Smith Papers.