Review of Joseph Smith’s Seer Stones

Joseph M. Spencer

Joseph M. Spencer, "Review of Joseph Smith's Seer Stones," Religious Educator 18, no. 2 (2017): 162–67.

Joseph M. Spencer (joseph_spencer@byu.edu) was a visiting assistant professor of ancient scripture at BYU when this article was published.

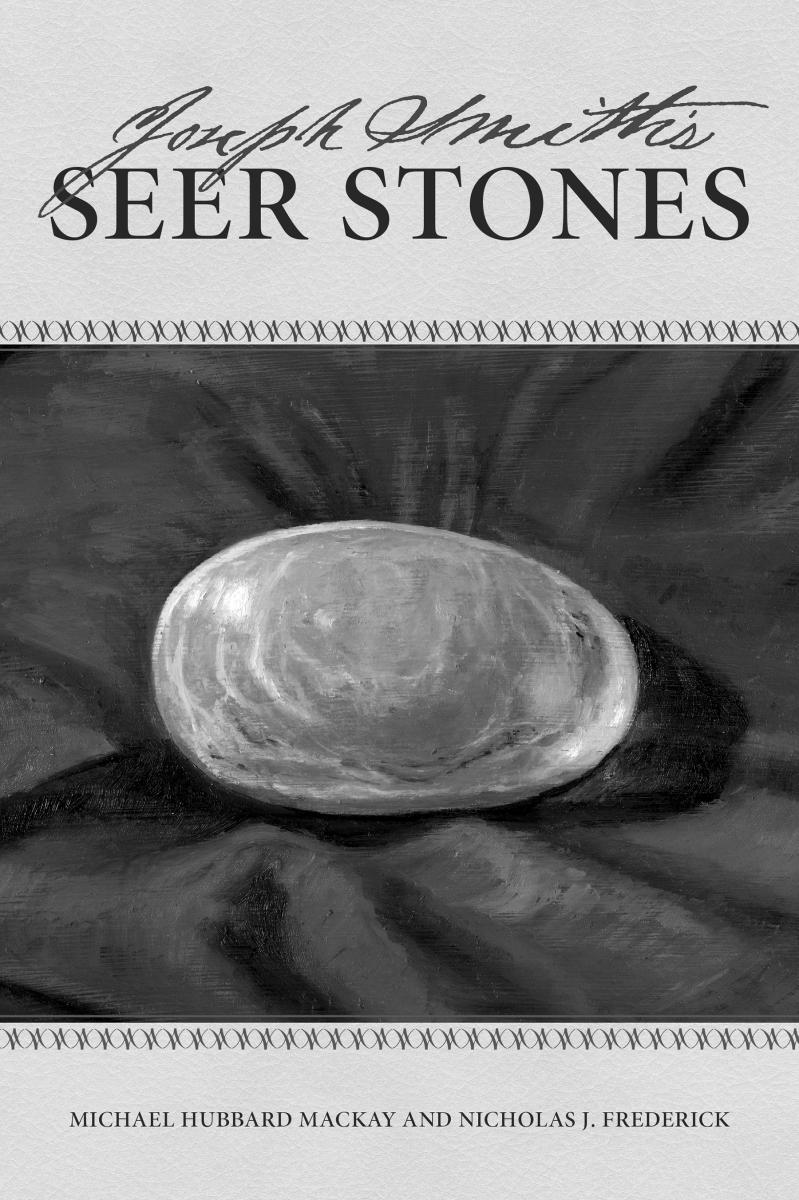

Michael Hubbard MacKay and Nicholas J. Frederick. Joseph Smith’s Seer Stones. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2016. Notes, color illustrations, appendices, annotated bibliography, index. Xxiv + 243 pp. ISBN 978-1-9443-9405-9, US $24.99.

Michael Hubbard MacKay and Nicholas J. Frederick. Joseph Smith’s Seer Stones. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2016. Notes, color illustrations, appendices, annotated bibliography, index. Xxiv + 243 pp. ISBN 978-1-9443-9405-9, US $24.99.

In 1961, Hugh Nibley published The Myth Makers, a creative analysis of Joseph Smith’s critics that exhibits what then-Elder Gordon B. Hinckley called a “Puckish delight” in satirizing those among the Prophet’s contemporaries who had unkind things to say about him.[1] In the book, Nibley imagines a deposition, held preparatory to “the case of the World versus Joseph Smith.”[2] The chairman of the deposition questions the critical witnesses in a sardonic critique of the reliability of the sources. In one scene, the chairman asks to “hear about the peepstone,” and he gets an earful.[3] The witnesses clamor for attention, vying to have their own stories about Joseph’s seer stone heard.[4] But the many voices, ultimately irreconcilable with each other, leave the chairman exasperated; Nibley finally has the chairman dismiss the whole lot of critical witnesses as hopelessly contradictory, suggesting that little can be learned from their accounts.[5]

Half a century has passed since The Myth Makers appeared, and the intervening years have demonstrated that, in fact, much can be learned from the sources Nibley despaired of. Some order can be found in the apparent chaos of the critical sources. In fact, when used in concert with documents produced by believers, they can be used to create a responsible and relatively coherent story about the Prophet’s seer stones. But, as Nibley’s important early survey revealed in advance, producing such a story requires serious sleuthing built on solid training in history. Good historians have for decades been doing such sleuthing, but their discoveries have been largely unknown to average Latter-day Saints. With increased awareness in recent years of various aspects of Mormon history—seer stones among these—there has arisen a real demand that the work of the best historians be packaged in a responsible but popular way. Nonspecialists interested in having their questions about seer stones answered have for too long lacked the resources they need to address the matter responsibly and thoroughly.[6]

With the publication of Joseph Smith’s Seer Stones, by Michael MacKay and Nicholas Frederick, what has hitherto been primarily a conversation written by and for specialists has been properly packaged for the first time for non-specialists. The authors clearly mean to allow—and to encourage—average Latter-day Saints to listen in on and to learn from conversations that have taken place principally among scholars.

Each chapter of the book means to answer one of the more persistent questions asked by average members of the Church in the wake of widespread awareness of the seer stones. The introduction properly addresses what may be the most commonly asked question about them: “Why am I only hearing about seer stones now?” But then the several chapters and appendices that follow provide answers (or outlines of answers) to questions asked with only slightly less urgency: Was use of seer stones unique or common in Joseph Smith’s day? How many seer stones did the Prophet have, and where did he get them? How did seer stones function in the translation of the Book of Mormon and other revealed texts? Where are Joseph Smith’s seer stones today? What do the Prophet’s seer stones have to do with the stones mentioned in the Book of Mormon and elsewhere in scripture (in the Book of Revelation, for instance)? What is the relationship between the seer stones and the Urim and Thummim, the one provided to Joseph Smith with the plates or the one spoken of in the Old Testament? Have others in the history of the Church used seer stones? How do we begin to make theological sense of the seer stones?

MacKay and Frederick address all of these questions (and others) as fully and honestly as possible. Where the historical evidence is contradictory or inconclusive, they hold back from drawing conclusions, even when they have opinions. Clearly, their intention is primarily to acquaint readers with the issues and to provide them with helpful resources, but then they wish to allow readers to draw their own conclusions. To this end, the volume closes with a most remarkable resource: a “Selected Annotated Bibliography for Seer Stone Sources.” Here the authors have provided fifty-two pages of primary sources regarding Joseph Smith’s seer stones. For each, a full citation for the source is provided, along with a full quotation of the most relevant material from the source. Readers are thus allowed to see what the historical sources say, quite directly, rather than only through the lens of an interpreter. The book, as a whole, is clearly meant to get average Latter-day Saints thinking, rather than to do the thinking for them.

Joseph Smith’s Seer Stones is, in my view, a most welcome contribution—and especially because of the way it positions itself between strictly scholarly or academic literature aimed at specialists and strictly nonscholarly or devotional literature aimed at average Latter-day Saints. Of course, many Latter-day Saint authors have produced works that skillfully translate academic literature into language that can speak to nonacademics. But MacKay and Frederick, it seems to me, do so in a way that not only makes scholarly conclusions, but also scholarly resources, available to their readers. They seem implicitly to recognize that many believing members of the Church want both to know the relevant issues and to have the resources to think through the issues themselves. Their book admirably provides its readers with everything necessary to reveal the complexity of the whole matter of Joseph Smith’s seer stones, but also with everything necessary to allow readers to think carefully through things. And Joseph Smith’s Seer Stones is helpfully—and wisely—filled with reminders not to draw conclusions too quickly. The book is thus an introduction to careful thought and research, rather than simply to what seems the best conclusion or conclusions to draw.

Much more impressive, in my view, is the fact that MacKay and Frederick recognize that nonspecialist readers are far less prone than practicing academics to draw strong lines between disciplines. They refuse to limit the materials they gather to historical sources from the nineteenth century. Instead, they delve seriously (and responsibly) into interpretive questions regarding the text of the Book of Mormon—about what might be said regarding seer stones that appear in the text, about what relationship those stones might bear to Joseph Smith’s stones, and about what certain passages in the text might imply about the very nature of the Book of Mormon as a translation. They also raise theological questions that go far beyond the limits of historical inquiry but that are of deep and lasting import to Latter-day Saints, asking about the use of material objects in lived religion, what seer stones suggest about the nature of prophetic knowledge, what role seer stones play in Joseph Smith’s vision of eternal life, and so on. Rather than cordoning off an intellectual space delimited by strict rules of discipline-specific inquiry, they draw on a variety of disciplinary resources in order to draw a richer portrait of the topic they address.

The result of this interdisciplinary approach—motivated by the natural interdisciplinarity of average Latter-day Saints—is that MacKay and Frederick leave their readers with the conviction that seer stones are less a reason to worry than an occasion for reflection and learning. Too often, scholarship on Latter-day Saint history and scripture has served primarily to make believers uncomfortable; in the hands of these authors, scholarship becomes an invitation to deeper study and richer discipleship. If, as Joseph Smith wrote from Liberty Jail, one’s “mind . . . must stretch as high as the utmost heavens, and search into and contemplate the darkest abyss, and the broad expanse of eternity”—at least if one wishes to “lead a soul unto salvation”—then Joseph Smith’s Seer Stones serves as an important invitation to do what the Prophet suggested.[7] It deserves a wide and committed readership.

Notes

[1] Quoted in Boyd Jay Petersen, Hugh Nibley: A Consecrated Life (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2002), 298.

[2] Hugh Nibley, Tinkling Cymbals and Sounding Brass: The Art of Telling Tales about Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, ed. David J. Whittaker (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1991), 105.

[3] Ibid., 219.

[4] Ibid., 220–29.

[5] Ibid., 262.

[6] Widespread awareness of seer stones began with the Gospel Topics essay on Book of Mormon translation, which appeared late in 2013, but then grew especially over the course of 2015 when: (1) From Darkness unto Light, a study of the events surrounding the translation of the Book of Mormon by Michael MacKay and Geritt Dirkmaat, appeared; (2) the Joseph Smith Papers Project published an edition of the Book of Mormon’s printer’s manuscript, along with photographs of one of the Prophet’s seer stones; (3) the Church’s own Ensign and Liahona magazines published an article called “Joseph the Seer” that discussed the translation process and reproduced an image of the seer stone; and (4) Temple Square’s Church History Museum put large photographs of the seer stone on display.

[7] History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957), 3:295–96.