Lincoln and the Brethren

Mary Jane Woodger and Jessica Wainwright Christensen

Mary Jane Woodger and Jessica Wainwright Christensen, "Lincoln and the Brethren," Religious Educator 11, no. 1 (2010): 109–42.

Mary Jane Woodger (maryjane_woodger@byu.edu) was a professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this was written.

Jessica Wainwright Christensen(jessicaannchristensen@hotmail.com) was a senior in English at BYU when this was written.

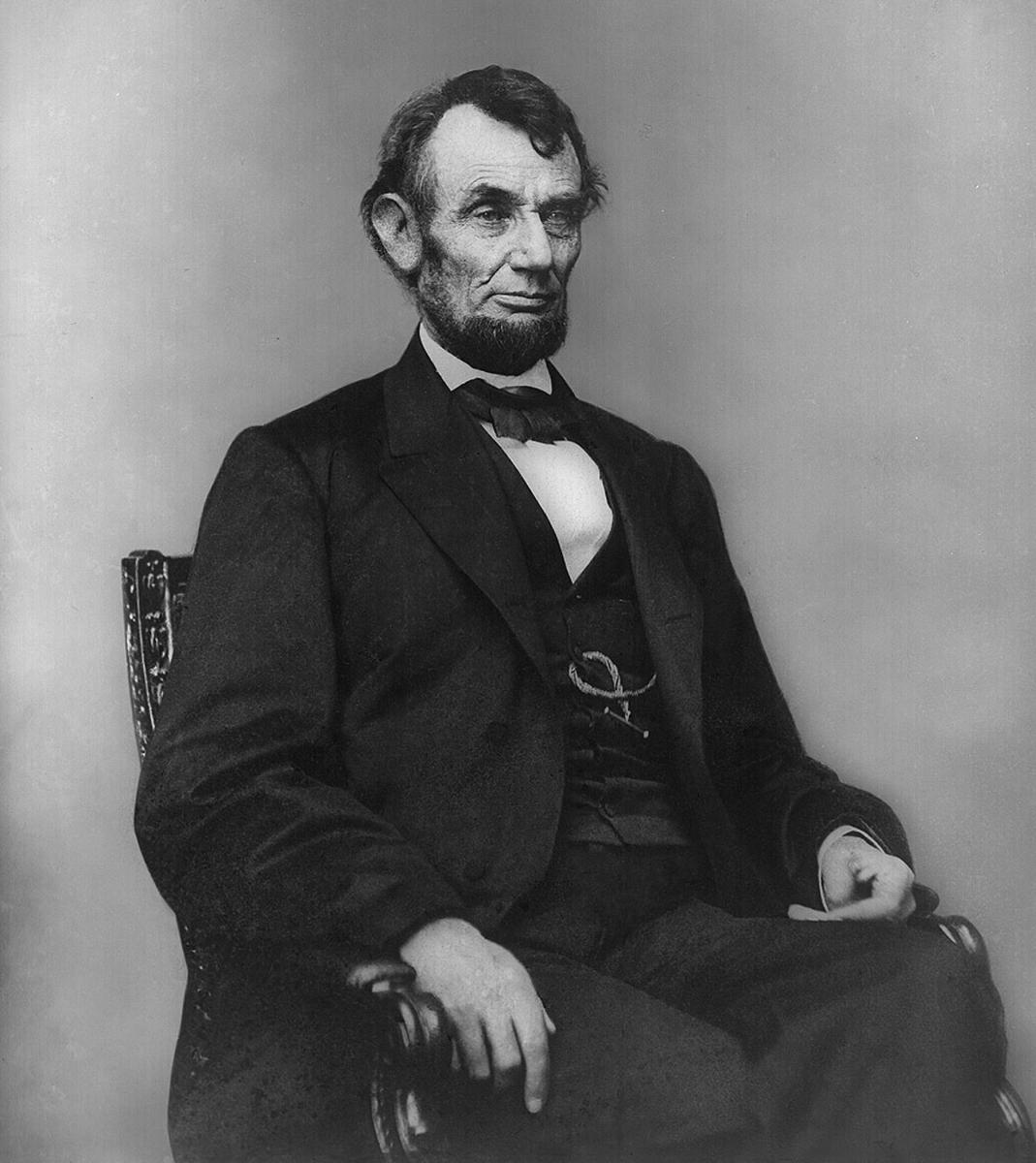

Abraham Lincoln, by Anthony Berger, taken February 9, 1864, Library of Congress.

Abraham Lincoln, by Anthony Berger, taken February 9, 1864, Library of Congress.

Modern General Authorities appreciate and delight in the words of Abraham Lincoln because they help portray gospel concepts in an imaginative and practical manner that appeals to common people.

In general conference addresses, a pattern can be identified of appropriating the words of famous people for pedagogical purposes. Over the years, General Authorities have utilized the words of such well-known figures as C. S. Lewis, Robert Browning, William Shakespeare, Mother Teresa, and George Washington to illustrate gospel principles. This practice among Church leaders shows a willingness to find examples of truth from many sources. By using the words or examples of notable personalities, General Authorities show that gospel truth is ubiquitous rather than exclusive to the standard works and authoritative writings of the Church.

Abraham Lincoln is one of the secular names most often heard over the pulpit at general conferences; his name is even more commonly used than that of the United States’ first president, George Washington. In the history of general conferences, Lincoln is quoted more often than Ralph Waldo Emerson (twenty-four times), Winston Churchill (fifteen times), and Thomas Jefferson (eight times). The sixteenth president of the United States has been quoted 124 times from the general conference pulpit, thirty-nine of those references taking place between 1960 and 1980.[1] From 1960 to 1980 there were approximately 1,660 conference addresses given, meaning Lincoln was quoted in more than two percent of general conferences during that time. Although the number of talks given in each general conference has diminished and the number of General Authorities has simultaneously increased over the years, we believe these statistics still present an accurate indication of the frequency with which Lincoln has been quoted.

In Lincoln in American Memory, historian Merrill D. Peterson argues that Lincoln’s image has been shaped to suit Americans’ own agendas, trends, and concerns.[2] The reverence current Church leaders have for Lincoln parallels Lincoln’s current national reputation among various religious, government, and social leaders. However, such respect and esteem was not given to Lincoln by General Authorities who were his contemporaries. Latter-day Saint leaders once considered this man an enemy, but by the end of the twentieth century they considered his life to be one worthy of emulation.

We will examine the cause of this shift and Lincoln’s gradual elevation in the minds of Latter-day Saints. In addition, this article will explore whether Church leaders coat-tailed the national explosion of Lincoln hagiography of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries or if their usage of Lincoln’s words was unique and independent. As we explore Church leaders’ frequent references to Lincoln’s words, we wish to point out that this study is not exhaustive as it is centered on official reports of general conferences. However, we believe that it does represent an accurate portrayal of the predominant LDS view of Abraham Lincoln. We will explore the relationship of Church leaders’ usage of Lincoln quotations to historical events and their personal backgrounds and experiences. Our study is categorized into four areas: references to Lincoln by his LDS contemporaries, declarations by Church leaders that Lincoln was inspired by God, statements of Lincoln quoted by Church leaders to support gospel principles, and stories about Lincoln referred to by Church leaders to illustrate gospel principles.

“Old Abe” and Contemporary Church Leaders

Latter-day Saint leaders who were Lincoln’s contemporaries did not speak about him in a reverential manner, perhaps because he had been affiliated with the Whig Party, known for its “anti-Mormon stance.”[3] In the 1838 presidential election, most Latter-day Saints voted for all of Benjamin Harrison’s electors except Abraham Lincoln. “In order to keep the Democrats in good humor, the Mormons scratched the last name on the Whig electoral ticket (Abraham Lincoln) and substituted that of a Democrat.”[4]

In contrast, Democrat Stephen A. Douglas had given attention to the Latter-day Saints and quickly built strong friendships with Church leaders. While Douglas asserted that Mormons should have the rights to worship as they pleased,[5] Lincoln was seen as somewhat irreligious. Lincoln once sarcastically said of himself, “No Christian ought to go for me because I belonged to no church, was suspected of being a Deist, and talked about fighting a duel.”[6] Such a statement would likely have done little to win over the citizens of Nauvoo.

In 1858, Lincoln and Douglas debated each other across the state of Illinois.[7] Douglas, who was by that time identified with the Mormons, “became a target for many of the opposition’s blasts” by appointing “partisans of the Church to court positions in Hancock County, thus helping arouse the intense anti-Mormon opposition in Warsaw.”[8] Whigs accused Douglas of “openly courting the Mormon vote.”[9] Whig Party journals publicized the Prophet Joseph Smith’s favorable attitude toward Douglas in 1842, and Douglas was cast for the next several years as a friend of the Mormons. It was obvious that Douglas was their choice over Lincoln.

Because of this early tension between the Saints and Lincoln, it would probably surprise early Church members to see Joseph Smith’s name later linked to that of Abraham Lincoln’s by his successors. For instance, Elder Charles H. Hart (1924) of the Seventy defended Lincoln’s apparent aloofness toward organized churches and associated Lincoln’s situation with that of Joseph Smith, in that they were both led to “prayer and to the truth.”[10] Elder Orson F. Whitney (1913) wondered how Lincoln could not have followed the advice of the Prophet Joseph Smith: “I have often marveled why those great men who came in contact with the Prophet Joseph Smith, men like Stephen A. Douglas and Abraham Lincoln, men of intelligence, men of character, men whose motives were pure and worthy for the most part—why they were not converted to the Gospel[,] the religion that Joseph Smith preached and represented.”[11] Elder Robert K. Dellenbach of the First Quorum of the Seventy compared the two leaders on account of their assassinations.[12]

Over the years as authors have occasionally slandered the name of Lincoln, LDS leaders have in turn openly defended him. Elders Joseph E. Robinson (1908)[13] and Albert E. Bowen (1946)[14] publicly renounced those who maligned Lincoln’s character. President Gordon B. Hinckley (1982) explained that those who saw Lincoln as lacking did not have the whole picture: “Abraham Lincoln was a gangling figure of a man, with a long and craggy face. There were many who looked only at the imperfections of his countenance. There were others who joked over the way he walked, and kept their eyes so low that they never saw the true greatness of the man. That enlarged view came only to those who saw the whole character—body, mind, and spirit—as he stood at the head of a divided nation.”[15] Such a defensive stance likely would have been surprising to Latter-day Saints who lived during the Civil War. In fact, one who did not see this “enlarged view . . . [of Lincoln’s] whole character—body, mind, and spirit”—was Brigham Young; nor did those who followed him to the Great Basin.

News of the election of Abraham Lincoln in the Deseret News on November 14, 1860, received a concerned response from Latter-day Saints. An editorial entitled “Prospective Dissolution” stated: “The day is not far distant, when the United States Government will cease to be, and that the Union, about which the politicians have harped and poets sung, will be no more.”[16] This was only one of many forecasts of doom that had been uttered for months by Church leaders in connection with Lincoln’s rise to the presidency. A member of the First Presidency, George A. Smith, also referred to Lincoln’s election in less than glowing terms, asserting that Lincoln was put into the office by “the spirit of priestcraft” and that this force would control him “to put to death, if it was in his power, every man that believes in the divine mission of Joseph Smith, or that bears testimony of the doctrines he preached.”[17]

Shortly after the election, when Lincoln was asked how he planned to address the “Mormon question” in the Utah Territory, he replied, “I intend to treat it as a farmer on the frontier would treat an old water-soaked elm log lying upon his land—too heavy to move, too knotty to split, and too wet to burn. I’m going to plow round it.”[18] Nibley reports Lincoln as saying, “That’s what I intend to do with the Mormons. You go back and tell Brigham Young that if he will let me alone, I will let him alone.”[19] However, Church leaders did not seem to believe that Lincoln would plow around or leave them alone. On July 9, 1861, it was reported that Brigham Young commented in his office: “Old ‘Abe’ the President of the U.S. has it in his mind to pitch into us when he had got through with the South.”[20] Brigham Young saw Abraham Lincoln as the head of a federal government evidently bent on eventually destroying the Saints. When word reached Latter-day Saints that federal tax agents had been sent to the Great Basin, President Young’s response was recorded by Wilford Woodruff (1861):

Abe Lincoln has sent these men here to prepare the way for an army. An order has been sent to California to raise an army to come to Utah. This is the reason why Bell came back. I pray daily that the Lord will take away the reins of government of the wicked rulers and put it into the hands of wise good [men]. I will see the day when those wicked rulers [are] wiped out. The governor quoted my sayings about the Constitution. I do and always have supported the Constitution but I am not in league with such cursed scoundrels as Abe Lincoln and his minions. They have sought our destruction from the beginning and Abe Lincoln has ordered an army to this territory from California and that order passed over on these wires. A senator from California said in Washington a short time since that the Mormons were in their way and must be removed. The feelings of Abe Lincoln is that Buchanan tried to destroy the Mormons and could not. Now I will try my hand at it.[21]

Though President Young was leery of Lincoln’s motives, when the overland telegraph line was completed he sent the following positive message on October 18, 1861: “Utah has not seceded but is firm for the constitution and laws of our once happy country.”[22] And when the Territory of Deseret was asked to send men to guard the overland mail route, President Young promptly responded affirmatively.[23]

A change in perception at the time of Lincoln’s assassination. Some may be surprised to learn that Lincoln was not unanimously supported; neither his political party nor the public as a whole gave him their loyalty. Lincoln biographer David Donald reminds us: “To most men of his own day Lincoln . . . was simply a rather ineffectual President. It is hard to remember how unsuccessful Lincoln’s administration appeared to most of his contemporaries.”[24] One comment by a member of Congress reveals that Lincoln’s support was not widespread among his fellow Republicans any more than it was among Latter-day Saints: “‘The decease of Mr. Lincoln is a great national bereavement,’ conceded [U.S. House] Representative J. M. Ashley of Ohio, ‘but I am not so sure it is so much of a national loss.’ Within eight hours of his murder Republican Congressmen in secret caucus agreed that ‘his death is a godsend to our cause.’”[25]

Unlike these responses to Lincoln’s assassination, the LDS and general American population’s perception of the man seemed to change at his death: they looked upon it as a great loss. Before his death, Lincoln’s words were not highly valued. Lincoln historian Douglas S. Wilson explained, “Only with his death . . . did it begin to dawn on his contemporaries that Abraham Lincoln’s words were destined to find a permanent place in the American imagination.”[26] Perhaps Lincoln’s image improved after his death because American citizens regretted that he would never see the fulfillment of his aspirations. Much of this shift in perception could have also been due to the nature of the president’s demise. Historian Merrill D. Peterson deduced, “The assassination of the President at any time would have caused an avalanche of emotion in the country; but because it came with dramatic, indeed theatrical, suddenness—a bolt in the clear sky—at the hour of victory, its force was multiplied a hundred times.”[27]

Immediately after his death, eulogistic Lincoln biographies were written by those who had known him. The story of “the Pioneer Boy, and how he became President”[28] became popular and surely resonated with the LDS pioneer community. With “the emotional impact of devastating war, hard-won victory, and calamitous assassination,”[29] the LDS and other American hearts may have softened with each new biography. That rush to the pen has not diminished: “Since 1865 on an average fifty books have been published each year about the Martyr President.”[30]

No other biography had the same impact as did Abraham Lincoln: The True Story of a Great Life, written by William Henry Herndon in 1893. Previous to publishing this biography, Herndon forecasted that “Lincoln will be, in the not distant future, the ideal man of America, if not of all the English speaking peoples, and every incident of his life will be sought for, read with pleasure, and treasured up in the memory of men.”[31] Herndon’s portrayal was exclusively a “Western Lincoln portrait”[32] which the LDS in the Western frontier certainly related to: “From the very beginning Herndon conceived his biography of Lincoln as a study in Western character; he consciously planned it to illustrate the ‘original western and south-western pioneer—the type of . . . open, candid, sincere, energetic, spontaneous, trusting, tolerant, brave and generous man.’”[33] Latter-day Saints who had not known him as their president began to identify with this Lincoln.

A season of relative silence. It took some time for Lincoln to become a permanent fixture in the LDS landscape. Our research shows that from 1860 to 1900, Church leaders made few statements regarding Lincoln. The dissonance between the LDS faith and United States laws may have been responsible for the absence of such references. The Morrill Act, which was signed by Lincoln, and the subsequent Edmunds Act, which outlawed polygamy in the United States, caused considerable distress for Latter-day Saints to the point that President John Taylor and most other Church leaders went into exile in order to avoid arrest.

It may not be coincidental that President Wilford Woodruff, who received the revelation ending polygamy (see Official Declaration 1), took the first steps toward presenting a positive view of Lincoln. In 1877, before the declaration was released, Woodruff presided over the ordinance work in which Lincoln and others were baptized and endowed by proxy in the St. George Temple.[34]

While Lorenzo Snow was the President of the Church, Lincoln was quoted for the first time in general conference (1899).[35] As LDS contemporaries of Abraham Lincoln passed on, indifferent and negative feelings about the sixteenth president apparently dissipated, and positive references began to surface with increasing rapidity.

From Scoundrel to Saint

By looking at historical contexts, we can understand the frequency of references to Lincoln’s name by General Authorities.

32 total references

32 total references

The first two decades of the twentieth century saw a remarkable increase in Church leaders’ statements about Lincoln as an admirable man. The course of General Authorities’ attitudes about Lincoln—from bitterness to veneration—closely resembled national trends: “A reform movement called ‘Progressivism’ arose. Its goals included greater democracy and social justice, honest government, and more effective regulation of business.”[36] Led by Theodore Roosevelt at the start of the twentieth century, the movement grew along with a notable increase of references to Lincoln in general conference. When the Republicans were in control, they continually claimed Lincoln as their founder. Roosevelt, a Republican, especially wanted to be associated with Lincoln, and during his 1912 election campaign “What Would Lincoln Do?” became his catchphrase.[37] Roosevelt successfully connected his name with Lincoln’s at least among Latter-day Saints; his name was mentioned in association with Lincoln’s by Church leaders on two occasions. Several additional events may have brought Lincoln back into the public memory in the first decades of the twentieth century: the commemoration of Lincoln’s one hundredth birthday (1909), the approval of placing his image on the penny (1909), and the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington DC on Memorial Day (1922).

The first Church President to refer to Lincoln as inspired was Joseph F. Smith (1906) when he pointed out that Christ had inspired all great philosophers, including Lincoln, who was guided “in emancipation and union.”[38] Elders Hyrum M. Smith (1905) and Charles Nibley (1925) expressed similar sentiments and said that Lincoln was “raised up” to do God’s will.[39] Elder Melvin J. Ballard (1930) said that God “was with Lincoln.”[40] Elder Richard R. Lyman (1919) called Lincoln the “man of his hour” and said that inspiration rested upon him.[41] Elder Rulon S. Wells (1919) referred to Lincoln as the “the human instrument in God’s hand of preserving [the] precious principles [of human liberty].”[42]

The events of World War I (1914–18) encouraged patriotism and the celebration of earlier American leaders such as Lincoln, and many began to use his life to embody democracy. For instance, Woodrow Wilson, president of the United States during World War I, was often referred to in connection with Lincoln. In addition, American ideals were shared with the Allied forces in World War I, giving a new dimension to Lincoln’s fame. The Big Three (Woodrow Wilson, David Lloyd George, and Georges Clemenceau) considered Lincoln a favorite topic of conversation. The popularity of Lincoln biographies by historian Carl Sandburg, who introduced Lincoln as the “the Strange Friend and the Friendly Stranger,” also influenced Lincolnology.[43] During the 1920s and 1930s Sandburg once again revived appreciation for Lincoln through his biographies, Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and Abraham Lincoln: The War Years. One Church leader suggested that reading these works would be beneficial for all Saints. President Hugh B. Brown (1965) counseled: “If one will become familiar, for instance, with the history of Abraham Lincoln as written by Carl Sandburg, he will there learn how to live, what to do and what to refrain from doing. He will be given courage to meet life’s problems.”[44] By this time Lincoln was securely revered and honored in LDS forums.

From 1921 to 1940, Church leaders made even more Lincoln references in which they portrayed him as a representative of the American objectives which the Church was actively supporting at the time. Over time the position of Lincoln in the eyes of Latter-day Saints was solidified by a declaration of President Heber J. Grant (1928) that “all Latter-day Saints believe firmly [that Lincoln] was raised up and inspired of God Almighty” and that his presidency was “under the favor of our Heavenly Father.”[45] Other Church leaders reiterated the same sentiment. During President Grant’s tenure, many declared that Lincoln was inspired, including Charles W. Nibley (1917, 1925),[46] Rulon S. Wells (1919, 1926),[47] Melvin J. Ballard (1919, 1930)[48] and David O. McKay (1922).[49] Elder Richard R. Lyman (1924) escalated this trend when he called the God that Latter-day Saints worship “the God of Lincoln.”[50]

During this time President Grant, one of the General Authorities who quoted Lincoln most often, developed the LDS Welfare Program and tried to establish friendships with national business leaders. President Grant, disconcerted by “the federal dole,” frequently said that Lincoln heralded work ethic. He quoted these Lincolnisms: “Let not him who is houseless pull down the house of another”[51] (1920) and “The prudent, penniless beginner in the world labors for wages for awhile, saves a surplus with which to buy land or tools for himself, then labors for himself another while, and at length hires another new beginner to help him” (1938).[52]

Also between 1920 and 1940, President Franklin Roosevelt established the New Deal, which led the nation to economic and political change by giving subsidies to farmers, promoting workers’ rights, and improving public lands. Both Grant and Roosevelt worked to ease the effects of the Great Depression and World War II, though their methods and philosophies were very different. It is pertinent to note that when both the Church President and the U.S. president worked toward mutual goals, Lincoln was referred to more often in conference addresses.

As both the nation and Church worked to rebuild Europe after World War II, America formally adopted the Marshall Plan. From 1945 to 1951, President George Albert Smith directed Church funds toward welfare projects in Europe. President Smith promoted the Boy Scout program within the Church and encouraged members to fulfill other civil responsibilities aligned with the national government.

In the 1960s, Lincoln’s popularity soared among U.S. citizens, and Church leaders were no exception. The Vietnam War caused many to become wary of corruption in the government; therefore, people tended to look to strong political leaders of the past like Lincoln for examples of integrity. Furthermore, many young people of this era rebelled from their parents and experimented with new lifestyles. We argue that the Prophets of this era used Lincoln’s legacy to illustrate the value of tradition to youth.

Lincoln was mentioned more by Church leaders in the years between 1960 and 1980 than in any other period. President David O. McKay (1968), who asserted that Lincoln was inspired by God,[53] emphasized the importance of family life and education. President McKay used Lincoln’s legacy to support the ideals of education and families. President McKay nearly leads all General Authorities in how frequently he quoted Lincoln, and he often called Lincoln a “good example.”

President McKay’s associates followed suit. Elder Mark E. Petersen (1969) cited Lincoln numerous times and testified that he “was one of the great men of all time, of all nations.” Peterson added that greatness such as Lincoln’s “leaves an indelible righteous stamp upon the world” and that such greatness “points to the divine destiny which God has provided for mankind.” Further, Elder Petersen taught that Lincoln “knew the Almighty was his Father who had raised him up for a special mission.” He even cited John Wesley Hill’s comparison of Lincoln to biblical prophets, stating that he was of the same fiber and that his “priestly functions [were] essential to the service of his nation and time.”[54] In 1976, the American bicentennial year, Elder Neal A. Maxwell implied that the Lord’s hand was manifest in the timing of Lincoln’s birth by declaring: “If you’ve got only one Abraham Lincoln, you’d better put him in that point in history when he’s most needed—much as some of us might like to have him now.”[55] Such declarations elevated Lincoln to the stature of one of the valiant spirits chosen and foreordained by God before birth to uphold his designs.

The frequency of remarks from LDS leaders about an inspired Abraham Lincoln increased from 1960 to 1980, when it began to wane slightly. During these years Lincoln was quoted by General Authorities more times (forty-three) than he was during any other period. In addition, the largest number of LDS leaders (ten) said he was inspired by God, and the most references (twenty three) were made to his example.

In 1978, President Spencer W. Kimball received the revelation extending the Melchizedek Priesthood to all worthy male members, including African-Americans. This revelation may have caused people to see parallels between Presidents Kimball and Lincoln because of Lincoln’s role in implementing equal status for African-Americans. During President Kimball’s presidency, African-Americans initiated the Civil Rights Movement. Furthermore, groups such as Native Americans, Hispanic-Americans, and women also sought equal rights. By this time Lincoln was seen as the personification of justice and equality, so it was natural for him to be cited on a regular basis in such a setting. In short, the explosion of Lincoln references in the years from 1960 to 1980 can be attributed to attitudes revolving around the Vietnam War, youth rebellion, and the Civil Rights Movement.

Since this peak period between 1960 and 1980, the regularity of Lincoln’s name appearing in the discourses of Church leaders at general conferences has persisted but waned slightly. Ezra Taft Benson, who followed Spencer W. Kimball as Church President, cited Lincoln’s words more times (eleven) during his tenure than did any other Church leader. This admiration of Lincoln was likely partly due to Benson’s position as secretary of agriculture in Dwight D. Eisenhower’s cabinet: “Lincoln was a storybook hero for Dwight D. Eisenhower. A copy of the famous Alexander Hesler photograph of 1860 hung from the wall of his office. . . . He quoted him repeatedly.”[56] This association with Eisenhower, who was fascinated with Lincoln, undoubtedly influenced Benson. “The overt religiosity of the Eisenhower presidency together with the resurgent revivalism of Billy Graham called attention to the paradox that . . . despite the law and the tradition of separation of church and state, the United States was, as G. K. Chesterton had said, ‘a nation with the soul of a church.’”[57] One of President Benson’s favorite Lincoln quotes (1962, 1968) was, “If [wickedness] ever reaches us, it must spring up among us. It cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time or die by suicide.”[58] The following graph shows President Benson as the most prolific among General Authorities in his use of Lincoln quotes in general conference.

Several insights can be extracted from the graph above. First, of the fifteen General Authorities who quoted Lincoln the most, all but four (Lyman, Grant, Smoot, and Hart) served as General Authorities during the period from 1960 to 1980. Note that Marion G. Romney, N. Eldon Tanner, and Hugh B. Brown were all raised outside the United States, yet they quoted Lincoln multiple times.

| General Authorities who quoted Lincoln once include: | |||

| Melvin J. Ballard | Matthew Cowley | Anthony W. Ivins | George S. Romney |

| M. Russell Ballard | Richard L. Evans | Willard Jones | L. W. Shurtliff |

| Albert E. Bowen | Lloyd P. George | Harold B. Lee | George Albert Smith |

| Hugh B. Brown | Marion D. Hanks | Neal A. Maxwell | Joseph F. Smith |

| Elray L. Christiansen | Rufus K. Hardy | Bruce R. McConkie | Steven E. Snow |

| James R. Clark | Devere Harris | Russell M. Nelson | James E. Talmage |

| J. Reuben Clark Jr. | Bryant S. Hinckley | Dallin H. Oaks | Lance B. Wickman |

| Rudger Clawson | Jeffrey R. Holland | LeGrand Richards | Clifford E. Young |

| Don B. Colton | Milton R. Hunter | Stephen L. Richards | |

Since the 1980s, the mention of Lincoln at the general conference pulpit has diminished slightly, again following the national trend of Lincolnology. Merrill Peterson tells us that Lincoln, a national “natural resource, still appeared inexhaustible in the last decade of the twentieth century. His memory had lost some of its clarity, warmth, and power among Americans, but it exerted more appeal than that of any other national saint or hero.”[59]

As President Gordon B. Hinckley took the reins of Church leadership in 1995, he emphasized the international nature of the Church. During his tenure, for the first time more Latter-day Saints lived outside the United States than within its borders and more temples were built worldwide. Because the Church was no longer largely confined to North America, the remarks of the General Authorities were more directed and applicable to members throughout the world. Although Lincoln remains an important figure for Americans, this focus on an international Church is a plausible explanation for the reduced numbers of Lincoln quotes used by Church leaders.

When Barack Obama became U.S. president in January 2009, he referred to Lincoln numerous times during his inaugural address. Perhaps more Lincoln quotes will appear at future general conferences due to this national exposure.

Using Lincoln Quotes to Illustrate Gospel Principles

While it is valuable to know who quoted Lincoln, it is even more vital to look at the specific Lincoln passages that General Authorities have found relevant to the message of the restored gospel. An examination of Lincoln statements quoted by Church authorities illustrates the kinship they felt for this man whom they perceive as God’s foreordained servant. Church leaders have suggested that Lincoln eloquently defended many principles found in LDS doctrine, though an examination of Lincoln’s words in their original context contradict this notion.[60]

In many instances when Church leaders have sought to teach LDS doctrine Lincoln’s statements and anecdotes served as excellent references. However, one thing is very clear about the way General Authorities used Lincoln to support gospel principles: in the 124 instances in which Church leaders cited Abraham Lincoln, his words were never used as the source of or as a confirmation of doctrine, only as a supplement. In addition, Lincoln was never singled out as a person equal in authority with Church officials, as a replacement for living prophets, or as a source of priesthood. Nor have leaders of the Church ever used Lincoln’s wisdom as the basis of their testimony of any gospel principle. To paraphrase LDS scholar Joseph Fielding McConkie, General Authorities obtain doctrinal insights from outside sources (such as Abraham Lincoln); however, they do not use these sources “to obtain the gospel or look to [them] as the source of [their] testimony”[61]

124 total references

124 total references

General Authorities quoting Lincoln. The first General Authority to quote Lincoln in general conference was Elder Rudger Clawson (1899), citing the Lincoln maxim, “God must love the poor because he has made so many of them.”[62] This quotation has been referred to by Church leaders on three other occasions, although not with much accuracy. Elder Bryant S. Hinckley (1916) quoted Lincoln as saying it was “plain people” whom God loved,[63] while President J. Reuben Clark Jr. (1960)[64] and Elder Milton R. Hunter (1964)[65] quoted Lincoln as saying the Lord must love “common people.” Apparently, whether God loves the poor, plain, or common, LDS leaders agreed with Lincoln. There are other discrepancies in the Lincoln quotes used by General Authorities; sometimes Church leaders inaccurately referenced or even failed to reference a quote at all. We do not believe it was the intention of General Authorities to forgo proper citation; rather, we see it is an indication of their general acceptance of Lincoln’s thoughts and words. These examples advocate biographer David Donald statement: “The Lincoln of folklore is more significant than the Lincoln of actuality.”[66] In an essay, “The Words of Lincoln,” Don E. Fehrenbacher suggested that in addition to their meanings “within a definite historical context, some of Lincoln’s words have acquired transcendent meaning as contributions to the permanent literary treasure of the nation.”[67]

Lincoln portrayed his mother as the ideal of motherhood and those who wrote about him perpetuated this claim. Donald wrote: “Regardless of origins, the biographers were sure of one thing. Lincoln loved his angel-mother. It is characteristic of the American attitude [and subsequently the LDS attitude] toward family life and of the extreme veneration for the maternal principle that the utterly unknown Nancy Hanks should be described as ‘a whole-hearted Christian,’ ‘a woman of marked natural abilities,’ of ‘strong mental powers and deep-toned piety,’ whose rigid observance of the Sabbath became a byword in frontier Kentucky—in short, ‘a remarkable woman.’”[68] Lincoln’s mother became “a carefully manipulated [symbol]”[69] to Americans and LDS leaders.[70] “All that I am or ever hope to be I owe to my angel mother” has been reiterated four times in General Authority addresses.[71] Elder Sterling W. Sill (1962) commented on Lincoln’s mother more than any other Church leader, once sharing the advice Lincoln received from his mother on her deathbed: “Abe, go out there and amount to something.”[72] Sill declared that this advice had a great impact on Lincoln’s life and then claimed: “That is exactly what he did by forming an attachment for great people and great books and great ideals. The memory of his mother and the influence of the Holy Bible probably made the greatest contribution toward making Lincoln what he was.”[73]

Wilson reiterated Fehrenbacher’s thoughts: “Americans have for a long time turned to Lincoln’s words not only for inspiration but to understand their own history. To ask the question ‘What are American values and ideals?’ is inevitably to invite an appeal to some of Lincoln’s most illustrious words.” But those words, as Fehrenbacher reminds us, came out of concrete historical circumstances, having been devised in response to specific situations.”[74] Lincoln biographer David Donald adds: “The historian may prove that the Emancipation actually freed a negligible number of slaves, yet Lincoln continues to live in men’s minds as the emancipator of the Negroes. It is this folklore Lincoln who has become the central symbol in American democratic thought; he embodies what ordinary, inarticulate Americans have cherished as ideals. As Ralph H. Gabriel says, he is ‘first among the folk heroes of the American people.’ From a study of the Lincoln legends the historian can gain a more balanced insight into the workings of the America mind.”[75]

Likewise, by looking at Lincoln as presented by Church leaders we can gain insight into the workings of the LDS mind. The Brethren derive Church doctrine through the revelations but like all good teachers they use various sources, including Lincoln, to support their message and intrigue their audience. Specifically, they have used Lincoln’s metaphors to portray theology dealing with principles such as home, motherhood, law, the Constitution, liquor, slavery, friendship, work ethic, labor, and the Bible.

Lincoln’s reverential views on the laws and the Constitution of the United States were often admired. In an address delivered during the bicentennial anniversary of the Constitution, President Ezra Taft Benson (1986) referred to Lincoln’s exhortation, “Let the Constitution . . . become the political religion of the nation.”[76]

Although Lincoln’s public life was often embroiled in contentious issues, LDS leaders discovered and stressed that his personal views were against strife and violence. For instance, Elder Marvin J. Ashton (1973) quoted Lincoln’s words concerning the treatment of enemies: “President Abraham Lincoln was once criticized for his attitude toward his enemies. ‘Why do you try to make friends of them?’ asked an associate. ‘You should try to destroy them.’ ‘Am I not destroying my enemies,’ Lincoln gently replied, ‘when I make them my friends?’”[77]

Along these same lines, President Thomas S. Monson (1997, 2001) taught the brethren of the Church: “Abraham Lincoln offered this wise counsel, which surely applies to home teachers: ‘If you would win a man to your cause, first convince him that you are his sincere friend.’”[78]

Considering the importance of the Word of Wisdom in the Church, it is not surprising that Lincoln’s repulsion toward liquor is also cited. President Spencer W. Kimball (1967) mentioned that “Abraham Lincoln refused to allow liquor served in his home to the delegation that came to give him the official notice of his nomination for the presidency, even though the liquor was free.” President Kimball also cited Lincoln’s admonition, “Liquor has its defenders, but no defense” and said Lincoln not only supported an emancipation from slavery but also an emancipation from liquor.[79] President Kimball related this event: “On the day of Lincoln’s assassination, he said to Major J. B. Merwin of the United States Army, a guest at the White House, ‘Merwin, we have cleaned up, with the help of the people, a colossal job. Slavery is abolished. After reconstruction, the next great question will be the overthrow and abolition of the liquor traffic. You know, Merwin, that my head and heart, and hand and purse will go into that work.’”[80]

Stories about Lincoln That Illustrate Gospel Principles

Much emphasis has been placed on Lincoln as a storyteller. However, those who knew him well did not consider him a storyteller. Lincoln biographer Horace Greeley “knew Lincoln for sixteen years and never heard him tell a story.” It was also “a side of the President that Frederick Douglass never observed.”[81] David Donald tells us:

By the centennial year of Lincoln’s birth the frontier stories that had been considered gamy and rough by an earlier generation had been accepted as typical Lincolnisms; and on the other side, the harshness of the Herndonian outlines was smoothed by the acceptance of many traits from the idealized Lincoln. The result was a “composite American ideal,” whose “appeal is stronger than that of other heroes because on him converge so many dear traditions.” The current popular conception of Lincoln is “a folk-hero who to the common folk-virtues of shrewdness and kindness adds essential wit and eloquence and loftiness of soul.”[82]

Donald stated that in Lincoln’s oft-repeated stories “the facts were at most a secondary consideration. Acceptance or rejection of any Lincoln anecdote depended upon what was fundamentally a religious conviction. Even today this attitude is sometimes found.”[83] Many General Authorities, following the pattern that Donald provides above, have used Lincoln stories to support their own religious convictions.

The most frequently quoted Lincoln story at general conferences deals with one of his conversations and has been cited by several Church leaders (1903, 1914, 1917, 1918, 1939, 1970) to illustrate principles such as obedience and faith: “I hope that the Lord is on our side” a friend of Lincoln or sometimes a minister says. Lincoln responds, “I do not worry about that at all; I know that the Lord is always on the side of right. What worries me most is to know if we are on the Lord’s side.”[84]

Another oft-quoted story by Church leaders (1944, 1949, 1960, 1962) involves General Sickles who fought at Gettysburg:

General Sickles had noticed that before the portentous battle of Gettysburg, upon the result of which, perhaps, the fate of the nation hung, President Lincoln was apparently free from the oppressive care which frequently weighed him down. After it was all past the general asked Lincoln how that was. He said: “Well, I will tell you how it was. In the pinch of your campaign up there, when everybody seemed panic-stricken and nobody could tell what was going to happen, oppressed by the gravity of affairs, I went to my room one day and locked the door and got down on my knees before Almighty God and prayed to him mightily for victory at Gettysburg. I told him that this war was his, and our cause his cause, but we could not stand another Fredericksburg or Chancellorsville. Then and there I made a solemn vow to Almighty God that if he would stand by our boys at Gettysburg, I would stand by him, and he did stand by our boys, and I will stand by him. And after that, I don’t know how it was, and I cannot explain it, soon a sweet comfort crept into my soul. The feeling came that God had taken the whole business into his own hands, and that things would go right at Gettysburg, and that is why I had no fears about you.”[85]

This story confirms that Lincoln believed in God to many. After relating this event, speakers offered encouragement to appeal to God for answers through prayer as Lincoln did.

A third story comes from a letter Lincoln wrote to a grieving mother who had lost five sons during the Civil War.

Dear Madam:

I have been shown in the files of the War Department a statement of the Adjutant General of Massachusetts that you are the mother of five sons who have died gloriously on the field of battle. I feel how weak and fruitless must be any word of mine which should attempt to beguile you from the grief of a loss so overwhelming. But I cannot refrain from tendering you the consolation that may be found in the thanks of the republic they died to save. I pray that our Heavenly Father may assuage the anguish of your bereavement, and leave you only the cherished memory of the loved and lost, and the solemn pride that must be yours to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of freedom.

Yours very sincerely and respectfully, A. Lincoln.[86]

Other General Authorities have related various stories about Lincoln regarding his faith in God exhibited during the Monitor and Merrimac battles (1952),[87] his independence and tenacity in the writing of the “House Divided against Itself” speech (1974),[88] his mother requesting him not to use liquor (1944),[89] and his numerous failures in running for political office before achieving success (1974).[90]

Considering the frequency of General Authorities’ references to Lincoln, some may assume that Lincoln agreed with Church doctrines, which is not necessarily true. Indeed, it should be noted that this “soldier of his Captain Christ” did not belong to any church.[91] However, in the same way we can appreciate Mozart’s music and not agree with his lifestyle, General Authorities utilize Lincoln’s power of exposition although his religious philosophy did not always concur with LDS doctrine. These quotes can engage our imaginations and make gospel principles more accessible. President Boyd K. Packer (1977) of the Quorum of the Twelve tells us when an “intangible ideal can be transposed into something tangible and teachable . . . there is a formula we can use.”[92] Abraham Lincoln was a master of this “formula”; perhaps this is the reason so many Church leaders use the imagery of his words to teach a variety of gospel concepts.

References to the example of Abraham Lincoln. In addition to citing Lincoln’s statements and stories, Church leaders have referred to aspects of Lincoln’s life as exemplary for Latter-day Saints.

The citations displayed in this graph identify specific instances where Lincoln’s characteristics were presented as worthy of emulation. For example, there are more than a dozen references citing Lincoln’s example as a man who prayed.[93] Lincoln’s impoverished background has been frequently mentioned to show how one could overcome humble beginnings.[94] His goodness or greatness has also often been referred to[95] and he has been cited as being a great statesman or leader[96] as well as a liberator or emancipator.[97] Furthermore, on at least six occasions Lincoln’s honesty or integrity was cited in general conference addresses.[98] Other characteristics of Lincoln that General Authorities have encouraged members to emulate include dedication,[99] reverence for the Lord’s name,[100] courage,[101] duty,[102] and obedience.[103] Elder Dallin H. Oaks (2001) praised Abraham Lincoln for his “wise and inspired use of a limited amount of information.”[104]

Of course, not all of Lincoln’s personality traits should be mirrored. As Donald tells us,

The Lincoln ideal offers an excellent starting-point for the investigation. As the pattern has gradually become standardized, the folklore Lincoln is as American as the Mississippi River. Essentially national, the myth is not nationalistic. It reveals the people’s faith in the democratic dogma that a poor boy can make good. It demonstrates the incurable romanticism of the American spirit. There is much in the legend which is unpleasant—Lincoln’s preternatural cunning, his fondness for Rabelaisian anecdote, his difficulties with his wife—yet these traits seem to be attributed to every real folk hero.[105]

The following graph illustrates the many instances where General Authorities cited Lincoln’s characteristics as exemplary:

| Single references to Lincoln as an example to learn from include: | ||||

| Lewis Anderson | Paul H. Dunn | Nephi Jensen | Dallin H. Oaks | |

| Melvin J. Ballard | James E. Faust | Spencer W. Kimball | George Albert Smith | |

| Albert E. Bowen | David B. Haight | Francis W. Kirkham | Reed Smoot | |

| Sylvester Q. Cannon | Charles H. Hart | Harold B. Lee | Walter Stover | |

| James R. Clark | Milton R. Hunter | John Longden | John A. Tvedtnes | |

| Matthew Cowley | Orson Hyde | Neal A. Maxwell | Rulon S. Wells | |

| Royden G. Derrick | Anthony W. Ivins | Thomas S. Monson | ||

Conclusion

A story from an Apostle can help us to make some conclusions:

As [Elder Bruce R. McConkie] waited for [a] flight to be announced, [he] buried himself in a book by a renowned New Testament scholar. He was delighted to discover material by a sectarian scholar that constituted a marvelous defense of Mormonism. As he boarded the flight he met Marion G. Romney, then a member of the First Presidency. He said, “President Romney, I have got to read this to you. This is good,” and proceeded to share his newfound treasure. When he was finished, President Romney said, “Bruce, I have to tell you a story. A few years ago I found something that I thought was remarkable written by one of the world’s great scholars. I read it to J. Reuben Clark, and he said, ‘Look, when you read things like that, and you find that the world doesn’t agree with us, so what? And when you read something like that and you find they are right on the mark and they agree with us, so what?’”[106]

In summary, we must ask, “If Church leaders quote Abraham Lincoln and his words seem to support LDS doctrine, so what?” There is adequate evidence to show that Abraham Lincoln has become an effective pedagogical voice for many General Authorities and that his portrayals have been firmly supported by Church leaders in general conference addresses. When members of the First Presidency, Quorum of the Twelve, and Seventy quote Abraham Lincoln’s words, many members of the Church take notice and even feel that his ideas are inspired. Lincoln is respected and thus quoted by Church leaders and members.

However, the admiration afforded Lincoln should not be equal to that shown to prophets and apostles. Although Church members and leaders alike hold Lincoln in esteem and ensured his proxy baptism and endowment were performed, Church members should not assume that these facts have necessarily given him a place as a member of the Church. One must remember that he did not accept the restored gospel when he was alive. His words are not used by General Authorities as if they were scriptural or prophetic, nor do General Authorities portray Lincoln as someone who has obtained prophetic stature. The use of his words by Church leaders does not give the Church credibility, because General Authorities do not need Lincoln’s word to support divine revelation.

On the other hand, we have established that many General Authorities cite Lincoln to illustrate doctrines that they have already obtained from the fountainhead of revelation. They appreciate and delight in the words of Abraham Lincoln because of his ability to portray gospel concepts in a manner that appeals to common people. They relate his imaginative declarations in practical ways for the cause of the Restoration. This examination of Lincoln’s statements as quoted by General Authorities illustrates the kinship felt by many Church leaders and Saints with this American hero as they use his apperceptions to further illustrate the truths of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ.

Appendix A. Conference Quotes Not Already Listed in Text

| General Authority | Conference Address | Abraham Lincoln Quote Used |

| Heber J. Grant | June 1919 | Take all of the Bible upon reason that you can, and the balance on faith, and you will live and die a better man. |

| Heber J. Grant | June 1919 | Never send a wrathful letter—burn it, and write another. |

| Heber J. Grant | June 1919 | Teach men that what they cannot take by an election they cannot take by war. |

Heber J. Grant Charles H. Hart George Albert Smith Richard R. Lyman George S. Romney Clifford E. Young N. Eldon Tanner | June 1919 April 1921 October 1922 October 1930 April 1934 April 1946 October 1965 | The question recurs “how shall we fortify against it?” The answer is simple. Let every American, every lover of liberty, every well-wisher to his posterity, swear by the blood of the Revolution never to violate, in the least particular, the laws of the country, and never to tolerate their violation by others. As the patriots of seventy-six did to the support of the Declaration of Independence, so to the support of the Constitution and laws, let every American pledge his life, his property and his sacred honor. Let every man remember that to violate the law, is to trample on the blood of his father, and to tear the charter of his own, and his children’s liberty. Let reverence for the law be breathed by every American mother to the lisping babe that prattles on her lap. Let it be taught in schools, in seminaries and in colleges. Let it be written in primers, in spelling books and almanacs. Let it be preached from the pulpit, proclaimed in legislative halls, and enforced in courts of justice. And, in short, let it become the political religion of the nation; and let the old and the young, the rich and the poor, the grave and the gay of all sexes and tongues and colors and conditions sacrifice unceasingly upon its altars. |

Heber J. Grant Joseph L. Wirthlin Thorpe B. Isaacson | April 1920 October 1944 October 1962 | That some should be rich shows that others may become rich and hence is just encouragement to industry and enterprise. Let not he who is houseless pull down the house of another, but let him work diligently and build one for himself, thus by example insuring that his own shall be safe from violence when built. |

Reed Smoot David O. McKay Mark E. Petersen Marion G. Romney | October 1924 April 1942 April 1968 October 1968 | This love of liberty which God has planted in us constitutes the bulwark of our liberty and independence. It is not our frowning battlements, our bristling seacosts, our army, and our navy. Our defense is in the spirit which prizes liberty as the heritage of all men, in all lands, everywhere. Destroy this spirit, and we have planted the seeds of despotism at our very doors. |

Heber J. Grant Richard R. Lyman N. Eldon Tanner | October 1928 October 1930 October 1965 | Bad laws, if they exist, should be repealed as soon as possible; still while they continue in force for the sake of example, they should be religiously observed. |

Richard R. Lyman David O. McKay Ezra Taft Benson Matthew Cowley Sterling W. Sill N. Eldon Tanner | April 1929 October 1942 October 1944 October 1951 April 1958 October 1967 | We have been the recipients of the choicest bounties of Heaven; we have been preserved these many years, in peace and prosperity; we have grown in numbers, wealth, and power as no other nation has ever grown. But we have forgotten God. We have forgotten the gracious hand which preserved us in peace and multiplied and enriched and strengthened us, and we have vainly imagined, in the deceitfulness of our hearts, that all these blessings were produced by some superior wisdom and virtue of our own. Intoxicated with unbroken success, we have become too self-sufficient to feel the necessity of redeeming and preserving grace, too proud to pray to the God that made us. . . . God rules this world—It is the duty of nations as well as men to own their dependence upon the overruling power of God, to confess their sins and transgressions in humble sorrow . . . and to recognize the sublime truth that those nations only are blessed whose God is the Lord. |

| Anthony W. Ivins | April 1930 | [paraphrased] Resolve that the faith in God manifested by our fathers, who bequeathed to us the priceless heritage of liberty which we now enjoy in this chosen land, shall not perish from the earth, but endure forever. This done we are secure, without it we have no guarantee. |

Orson F. Whitney David O. McKay Richard R. Lyman J. Reuben Clark | October 1930 April 1940 April 1943 April 1957 | Government of the people, by the people, for the people. |

Levi Edgar Young Don B. Colton Richard R. Lyman Joseph F. Smith Gordon B. Hinckley | April 1932 October 1933 October 1942 April 1946 October 1980 | With malice towards none, with charity for all. |

| Levi Edgar Young | April 1935 | Pray that we be spared further punishment. |

| Richard L. Evans | October 1938 | [paraphrased] He who molds public sentiment does more than he who enacts laws or hands down decisions. |

| Heber J. Grant | October 1938 | You will never get me to support a measure which I believe to be wrong, although by doing so I may accomplish that which I believe to be right. |

| Reed Smoot | October 1940 | One rainy night I could not sleep. The wounds of the soldiers and sailors disturbed my very bones, pierced my heart, and I asked God to show me how they could have better relief. After wrestling some time in prayer he put the plans of a sanitary commission in my mind and they have worked out pretty much as God gave them to me that night. You ought to thank your kind heavenly Father and not me for the sanitary commission. |

| Rufus K. Hardy | October 1941 | I am conscious every moment that all I am and all I have are subject to the control of a Higher Power, and that Power can use me in any manner and at any time as in His wisdom might be pleasing to Him. |

| Albert E. Bowen | April 1942 | All the wealth piled up by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall sink, and until every drop of blood drawn by the lash shall be paid by another drawn by the sword. |

Ezra Taft Benson Thorpe B. Isaacson N. Eldon Tanner Mark E. Petersen Devere Harris | October 1944 April 1961 October 1966 April 1967 October 1984 | Without the assistance of that Divine Being, . . . I cannot succeed. But with that assistance, I cannot fail. |

Heber J. Grant Thomas S. Monson | October 1944 April 1986 | Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith let us to the end dare to do our duty as we understand it. |

| Joseph L. Wirthlin | April 1949 | I went to my room one day and locked the door and got down upon my knees before Almighty God and prayed to him mightily for victory at Gettysburg. |

| Stephen L. Richards | April 1950 | You can’t fool all the people all the time. |

| Joseph L. Wirthlin | October 1951 | If I ever have a chance to strike this thing [slavery], I will strike it hard. |

| Marion G. Romney | April 1952 | The discipline and character of the national forces should not suffer, nor the cause they defend be imperiled, by the profanation of the day or name of the Most High. |

Marion G. Romney Thorpe B. Isaacson Mark E. Petersen | April 1952 April 1961 April 1967 | I have had so many evidences of his direction, so many instances when I have been controlled by some other power than my own will, that I cannot doubt that this power comes from above. I frequently see my way clear to a decision when I am conscious that I have not sufficient facts upon which to found it. |

Alma Sonne Sterling W. Sill | April 1958 October 1974 | I am not bound to win, but I am bound to be true. I am not bound to succeed, but I am bound to live up to what light I have. |

| Thorpe B. Isaacson | October 1963 | To sin in silence when protest is good makes cowards out of men. |

| ElRay L. Christiansen | October 1963 | No people can ever become greater by lowering their standards, no society was ever improved by adopting a looser morality. |

Alma Sonne M. Russell Ballard | October 1964 April 2007 | This Great Book . . . is the best gift God has given to man. All the good the Saviour gave to the world was communicated through this book. But for it we could not know right from wrong. |

Marion D. Hanks Ezra Taft Benson | October 1976 October 1974 | When I do good I feel good, and when I don’t do good I don’t feel good . . . and when I do bad I feel bad. |

| David O. McKay | October 1968 | I still have confidence that the Almighty, the Maker of the Universe, will, through the instrumentality of this great and intelligent people, bring us through this as he has through all other difficulties of our country. |

| John H. Vandenberg | April 1970 | [paraphrased] “How many legs would a sheep have if we called the tail a leg?” When the answer, “Five,” was given, he corrected it by explaining that just calling the tail a leg didn’t make it one. |

| Harold B. Lee | April 1971 | I accept all I read in the Bible that I can understand, and accept the rest on faith. |

| John H. Vandenberg | October 1971 | I can see how it might be possible for a man to look down upon the earth and be an atheist, but I cannot conceive how he could look up into the heavens and say there is no God. |

| Marvin J. Ashton | October 1976 April 1989 | It is difficult to make a man miserable when he feels he is worthy of himself and claims kindred to the great God who made him. |

| Mark E. Petersen | October 1976 | If we do not do right, God will let us go on our way to ruin. |

| Bruce R. McConkie | April 1978 | . . . conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. |

| Howard W. Hunter | April 1978 | I will prepare, and perhaps my chance will come. |

| Marion G. Romney | October 1981 | The shepherd drives the wolf from the sheep’s throat, for which the sheep thanks the shepherd as his liberator, while the wolf denounces him for the same act. |

| Marvin J. Ashton | April 1982 | Stand with anybody that stands right. Stand with him while he is right and part with him when he goes wrong. |

| Russell M. Nelson | April 1989 | Quarrel not at all. No man resolved to make the most of himself can spare time for personal contention. . . . Better give your path to a dog than be bitten by him. |

| Lloyd P. George | April 1994 | Die when I may, I would like it said of me by those who knew me best, that I always plucked a thistle, and planted a rose where I thought a rose would grow. |

| Neal A. Maxwell | April 1999 | . . . thirsts and burns for distinction, and if possible . . . will have it, whether at the expense of emancipating slaves or enslaving freemen. |

| Lance B. Wickman | April 2008 | . . . gave the last full measure of devotion. |

Notes

[1] See graph 3.

[2] Merrill D. Peterson, Lincoln in American Memory (Cary, NC: Oxford University Press, 1995).

[3] Bruce A. Van Orden, “Stephen A. Douglas and the Mormons,” in Regional Studies in LDS History: Illinois, ed. H. Dean Garrett (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 1995), 365.

[4] William Alexander Linn, The Story of the Mormons (New York: Macmillan, 1902), 244.

[5] Robert W. Johannsen, Stephen A. Douglas (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), 109.

[6] Clark Prescott Bissett, Abraham Lincoln: A Universal Man (San Francisco: J. Howell, 1923), 98.

[7] Stephen B. Oates, Abraham Lincoln: The Man Behind the Myths (New York: Harper Perennial, 1994), 3.

[8] Van Orden, “Douglas and the Mormons,” 363.

[9] Johannsen, Stephen A. Douglas, 107.

[10] Charles H. Hart, in Conference Report, October 1924, 34. Hart said: “The explanation of attributing infidelity [meaning an infidel who did not believe in God] to Lincoln is given by the author of the book, The Son of Abraham Lincoln. He suggests that it was the contention of the different denominations . . . that may have distracted Abraham Lincoln, just as we know at about the same time it distracted the Prophet Joseph Smith and led him to prayer and to the truth.”

[11] Orson Whitney, in Conference Report, April 1913, 123.

[12] Robert K. Dellenbach, “Sacrifice Brings Forth the Blessings of Heaven,” Ensign, November 2002, 33.

[13] Joseph E. Robinson, in Conference Report, October 1908, 24.

[14] Albert E. Bowen, in Conference Report, April 1946, 178.

[15] Gordon B. Hinckley, “Five Million Members—A Milestone and Not a Summit,” Ensign, May 1982, 44.

[16] “Prospective Dissolution,” Desert News, November 28, 1860.

[17] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter Day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 9:18.

[18] Orson F. Whitney, in Conference Report, April 1928, 58.

[19] Preston Nibley, Brigham Young: The Man and His Work (Salt Lake City: Desert Book, 1936), 369.

[20] E. B. Long, The Saints and the Union: Utah Territory during the Civil War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981), 36.

[21] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1833–1898 (Midvale, UT: Signature Books, 1984), 606; spelling and capitalization modernized.

[22] As quoted in Leonard J. Arrington, Brigham Young: American Moses (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985), 294. This occurrence was mentioned in general conference by Melvin J. Ballard (October 1914, 67); Richard W. Young (October 1919, 148); and David O. McKay (October 1953, 97).

[23] Young, in Journal of Discourses, 10:107.

[24] David Donald, Lincoln Reconsidered (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1959), 128.

[25] Donald, Lincoln Reconsidered, 4.

[26] Douglas L. Wilson, Lincoln’s Sword: The Presidency and the Power of Words (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), 3.

[27] Peterson, Lincoln in American Memory, 8.

[28] David Donald, Lincoln’s Herndon (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1948), 371.

[29] Donald, Lincoln’s Herndon, 371.

[30] Donald, Lincoln’s Herndon, 368.

[31] William Henry Herndon and Jesse William Weik, Herndon’s Life of Lincoln (New York: Da Capo Press, 1983), vi.

[32] Donald, Lincoln’s Herndon, 371.

[33] Donald, Lincoln’s Herndon, 371.

[34] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 369.

[35] Rudger Clawson, in Conference Report, April 1899, 4.

[36] U.S. Department of State, “Discontent and Reform,” America: Engaging the World, http://

[37] Peterson, Lincoln in American Memory, 165.

[38] Gospel Doctrine: Selections from the Sermons and Writings of Joseph F. Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1919), 31.

[39] Hyrum M. Smith, in Conference Report, April 1905, 97; Charles W. Nibley, in Conference Report, April 1925, 24.

[40] Melvin J. Ballard, in Conference Report, April 1930, 157.

[41] Richard R. Lyman, in Conference Report, October 1919, 120.

[42] Rulon S. Wells, in Conference Report, October 1919, 208.

[43] Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and the War Years, ed. Edward C. Goodman (New York: Sterling, 2007), 94.

[44] Hugh B. Brown, The Abundant Life (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1965), 108.

[45] Heber J. Grant, in Conference Report, October 1928, 11.

[46] Charles W. Nibley, in Conference Report, April 1917, 144; April 1925, 24.

[47] Rulon S. Wells, in Conference Report, October 1919, 206; October 1926, 134.

[48] Melvin J. Ballard, in Conference Report, October 1919, 119–20; April 1930, 157.

[49] David O. McKay, in Conference Report, April 1922.

[50] Richard R. Lyman, in Conference Report, April 1924, 141.

[51] Heber J. Grant, in Conference Report, April 1920, 10.

[52] Heber J. Grant, in Conference Report, October 1938, 5.

[53] David O. McKay, in Conference Report, October 1968, 144.

[54] Mark E. Petersen, The Way to Peace (Salt Lake City, Bookcraft, 1969), 26–27.

[55] Neal A. Maxwell, Deposition of a Disciple (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 46.

[56] Peterson, Lincoln in American Memory, 324.

[57] Peterson, Lincoln in American Memory, 358.

[58] Ezra Taft Benson, in Conference Report, April 1962, 105; April 1968, 50.

[59] Peterson, Lincoln in American Memory, 395.

[60] See appendix A.

[61] Joseph Fielding McConkie, Here We Stand (Salt Lake City: Desert Book, 1995), 124.

[62] Rudger Clawson, in Conference Report, April 1899, 4.

[63] Bryant S. Hinckley, in Conference Report, October 1916, 83.

[64] J. Reuben Clark Jr., “Work—Work Always!” address given to Brigham Young University student body, Provo, UT, May 25, 1960, 5.

[65] Milton R. Hunter, “The Eternal Quest for Happiness,” address given to Brigham Young University student body, Provo, UT, May 12, 1964, 3.

[66] Donald, Lincoln Reconsidered, 164.

[67] In Wilson, Lincoln’s Sword, 7.

[68] Donald, Lincoln Reconsidered, 150.

[69] Donald, Lincoln Reconsidered, 150.

[70] See Brown, The Abundant Life, 71–72; Heber J. Grant, in Conference Report, April 1934, 14; Don B. Colton, in Conference Report, April 1936, 110.

[71] Sterling W. Sill, in Conference Report, April 1960, 69; Sterling W. Sill “A Personal Proposal: D&C, Section Four,” address given to Brigham Young University student body, Provo, UT, November 1965, 2; Marvin J. Ashton, “The Word Is Commitment,” Ensign, November 9, 1983, 61; Steven E. Snow, “Service,” Ensign, November 2007, 102.

[72] Sterling W. Sill, “Your Hall of Fame,” address given to Brigham Young University student body, Provo, UT, February 21, 1962, 3.

[73] Sill, “Your Hall of Fame,” 3.

[74] Wilson, Lincoln’s Sword, 7.

[75] Donald, Lincoln Reconsidered, 164–65.

[76] Ezra Taft Benson, “The Constitution—A Heavenly Banner,” address given to Brigham Young University student body, Provo, UT, September 16, 1986.

[77] Marvin J. Ashton, “What Is a Friend?” Ensign, January 1973, 41.

[78] Thomas S. Monson, “Home Teaching—A Divine Service, Ensign, November 1997, 46; “To the Rescue,” Ensign, May 2001, 48.

[79] Spencer W. Kimball, in Conference Report, October 1967, 31, 32.

[80] Kimball, in Conference Report, October 1967, 31.

[81] Peterson, Lincoln in American Memory, 99.

[82] Donald, Lincoln Reconsidered, 162–63.

[83] Donald, Lincoln Reconsidered, 161.

[84] Hugh S. Gowans, in Conference Report, April 1903, 97; James E. Talmage, in Conference Report, October 1914, 104; J. Golden Kimball, in Conference Report, October 1917, 134; Willard L. Jones, in Conference Report, April 1918, 121; Gustive O. Larson, in Conference Report, October 1939, 53; Sterling W. Sill, in Conference Report, October 1970, 77.

[85] Marion G. Romney, in Conference Report, October 1944, 57; Joseph L. Wirthlin, in Conference Report, April 1949, 157; Thorpe B. Isaacson, in Conference Report, October 1962, 29.

[86] Heber J. Grant, Messages of the First Presidency: 1935–1951, ed. James R. Clark, (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1975), 6:31; Thomas S. Monson, “He Is Risen,” Ensign, November 1981, 16.

[87] Alma Sonne, in Conference Report, October 1952, 112.

[88] Marion G. Romney, “Integrity,” Ensign, November 1974, 74–75.

[89] Marvin O. Ashton, in Conference Report, October 1944, 108.

[90] Spencer W. Kimball, “The Davids and the Goliaths,” Ensign, November 1974, 80.

[91] Donald, Lincoln Reconsidered, 152.

[92] Boyd K. Packer, Teach Ye Diligently (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1975), 34.

[93] Richard R. Lyman, in Conference Report, April 1922, 79; Richard R. Lyman, in Conference Report, October 1929, 80; Matthew Cowley, in Conference Report, October 1951, 105; Marion G. Romney, in Conference Report, April 1952, 90; Marion G. Romney, “The Beginning of Wisdom,” address given to Brigham Young University student body, Provo, UT, February 11, 1964, 7; Ezra Taft Benson, in Conference Report, October 1956, 105, 107; Teachings of Ezra Taft Benson, 429; Ezra Taft Benson, in Conference Report, April 1963, 109; Ezra Taft Benson, in Conference Report, April 1966, 131–32; Mark E. Petersen, in Conference Report, April 1956, 78; Mark E. Petersen, “The Savor of Men,” Ensign, November 1976, 48; Milton R. Hunter, in Conference Report, April 1963, 16–17; Paul H. Dunn, “Time-Out!” Ensign, May 1980, 38.

[94] Melvin J. Ballard, in Conference Report, April 1929, 69; Thomas S. Monson, “Labels,” Ensign, November 1983, 19; Joseph B. Wirthlin, “Never Give Up,” Ensign, November 1987, 9; David O. McKay, Ancient Apostles (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1964), 3–4.

[95] George Albert Smith, in Conference Report, April 1928, 45; Heber J. Grant, in Conference Report, October 1922, 186; Heber J. Grant in Conference Report, April 1930, 184; David O. McKay, in Conference Report, April 1943, 18; Petersen, “Savor of Men,” 48.

[96] Heber J. Grant, in Conference Report, June 1919, 120; Richard R. Lyman, in Conference Report, April 1922, 79; Hugh B. Brown, in Conference Report, April 1964, 54; Petersen, The Way to Peace, 5.

[97] Anthony W. Ivins, in Conference Report, October 1928, 16; Rulon S. Wells, in Conference Report, April 1930, 72; The Teachings of Spencer W. Kimball, ed. Edward L. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1982), 431; Charles A. Callis, in Conference Report, October 1938, 24; Ezra Taft Benson, in Conference Report, April 1954, 59; Richard C. Edgley, “The Empowerment of Humility,” Ensign, November 2003, 97.

[98] Richard R. Lyman, in Conference Report, October 1927, 98; J. Reuben Clark Jr., in Conference Report, April 1934, 109; Romney, “Integrity,” 75; Royden G. Derrick, “By Their Fruits Ye Shall Know Them,” Ensign, November 1984, 61; David B. Haight, “Ethics and Honesty,” Ensign, November 1987, 13.

[99] David O. McKay, in Conference Report, October 1937, 102.

[100] Henry D. Taylor, in Conference Report, April 1964, 89.

[101] Hugh B. Brown, in Conference Report, April 1964, 54.

[102] Richard R. Lyman, in Conference Report, October 1919, 109.

[103] Petersen, “Savor of Men,” 50.

[104] Dallin H. Oaks, “Focus and Priorities,” Ensign, May 2001, 83.

[105] Donald, Lincoln Reconsidered, 165.

[106] McConkie, Here We Stand, 114.