You Shall Have My Word

Apostolic Dedication and Translation of the Chinese Book of Mormon (1959–65)

Chou Po Nien (Felipe) (周伯彥) and Chou Sin Mei Wah (Petra) (周冼美華), “You Shall Have My Word: Apostolic Dedication and Translation of the Chinese Book of Mormon,” in Voice of the Saints in Taiwan, ed. Po Nien (Felipe) Chou (周伯彥) and Petra Mei Wah Sin Chou (周冼美華) (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 61-100.

In 1959, Elder Mark E. Petersen, then a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, visited the island and dedicated Taiwan for the preaching of the gospel. By the dawn of the 1960s, the Southern Far East Mission had divided the area of Taiwan into two districts—North Taiwan and South Taiwan. These districts comprised eight total cities, each with its own branch, including the capital city of Taipei. As of September 1959, the number of missionaries in Taiwan had increased from the original four missionaries to forty-six.[1] In this chapter we discuss the apostolic dedication in 1959 and key events that transpired in the 1960s, including the service of early local missionaries, the beginning of Elder Gordon B. Hinckley’s ministry, and the translation of the Book of Mormon into Chinese.

Elder Mark E. Petersen’s Visit and Dedication of Taiwan

In 1955, after organizing the Southern Far East Mission, President Joseph Fielding Smith informed President Heaton “that it was the policy of the First Presidency to have General Authority visits to all foreign missions annually.” However, when no one came in 1956, Heaton began to inquire about it in his quarterly mission report to the First Presidency and his letters with President Smith and Elder Harold B. Lee. Heaton reported there were no General Authorities assigned to visit his mission for nearly three years. The one exception was the visit of Elder Ezra Taft Benson, traveling in the capacity of a US government official. Heaton said, “Elder Benson was able to give the missionaries a much needed spiritual uplift, but he was unable to do anything about the needs of the Mission.”[2] The following letter from President Smith lamented the lack of visitors to the mission:

I am very sorry that your mission has been overlooked. I understood that it was the intention to visit the missions once each year and now we are passed the third year and no visit. This is a great disappointment to me.. . . We are greatly pleased, however, with the reports that come from your mission. I congratulate you because of the fullness of these reports and the details which so frequently do not appear in the reports of many of the other missions.[3]

In 1959, Heaton was hopeful after receiving communication from Brother Franklin Murdock, from the General Church offices. Murdock had visited Hong Kong the previous year on his way to a travel agents’ conference in Singapore. After visiting a local branch, Murdock said, “President McKay must be able to see this.” Heaton reported:

I received communication from Brother Murdock, informing me that he had been advised that President McKay was scheduling a visit to the Far East in June. Because of potential health problems of President McKay, or other scheduling problems, Brother Murdock requested that we make no public announcement of the visit. This news was exciting and welcome[0].[4]

Unfortunately, President McKay’s health became worse, and he was unable to come. In May 1959, Heaton was notified that Elder Mark E. Petersen of the Quorum of the Twelve would be coming instead.[5] The missionaries were very excited to welcome the Petersens to Taiwan. Elder Michael Walker remembered, “For three years, the members and investigators have heard about the leaders of the Church . . . a Prophet by the name of David O. McKay, who can receive revelations. Also, at the head of this great Church there are twelve living Apostles, who also can receive revelations.” Walker added, “It finally happened!,” when Elder Petersen came to Taiwan.[6]

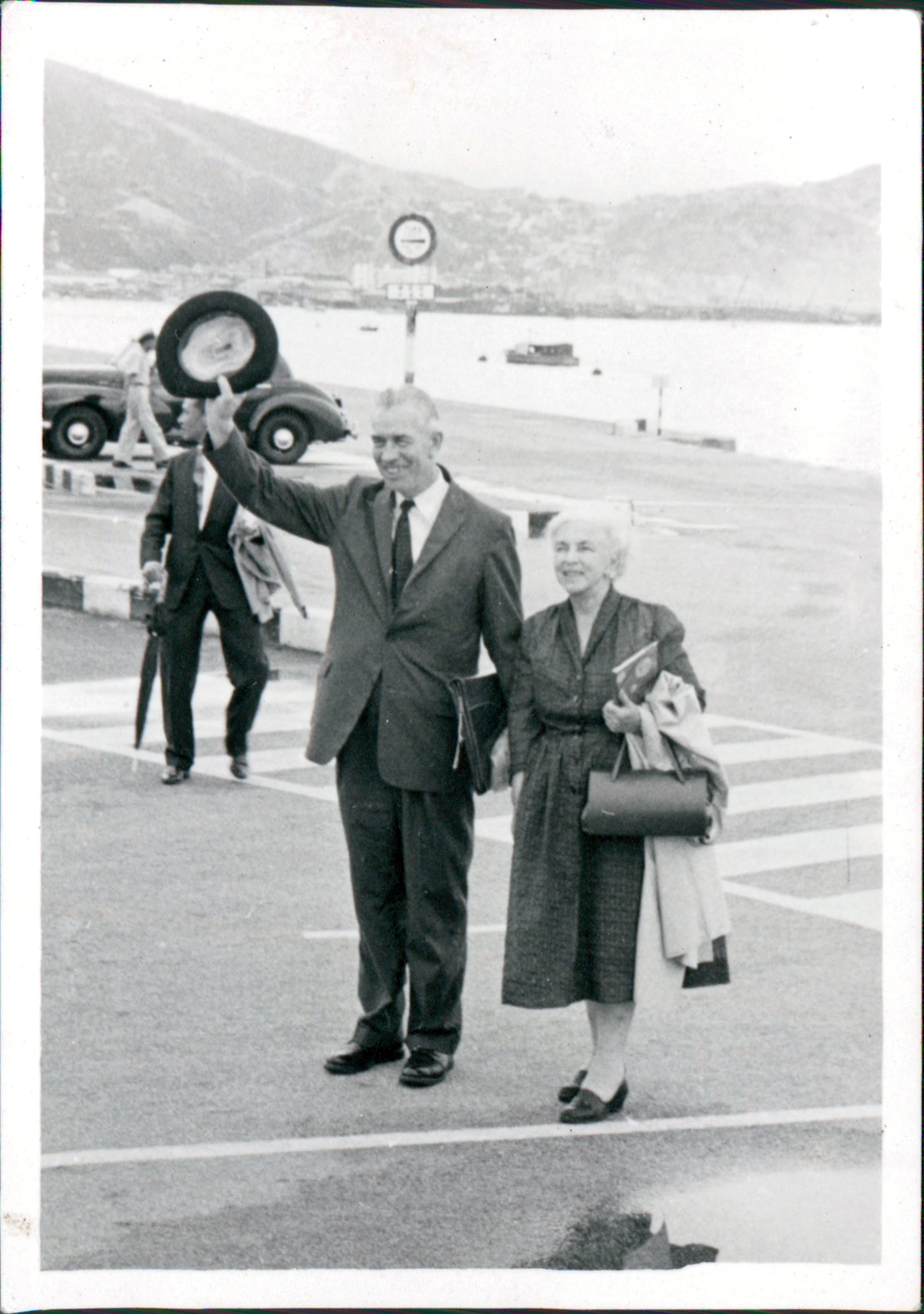

Mark E. and Emma Petersen at the airport in 1959. Courtesy of Heaton family.

Mark E. and Emma Petersen at the airport in 1959. Courtesy of Heaton family.

On 25 May 1959, Elder Mark E. Petersen and his wife arrived at the Taipei airport. President and Sister Heaton arrived on the same day from Hong Kong to accompany the Petersens. The members and the missionaries were at the airport and greeted the visitors with a “Welcome, Brother and Sister Petersen” banner.[7] Brother Chen Meng-Yu (陳孟猶) said, “The minute the people saw [Elder Petersen] at the airport, getting off the plane, they could sense a man of God by his appearance. He was impressed with the spirit Elder Petersen seemed to radiate.” Brother Tseng I-Chang (曾翼璋) “remarked on his humbleness, how he talked to everybody, shook their hands and let them take pictures of him. He was particularly impressed that such a great man was so humble.”[8] Elder Petersen and those traveling with him took a train to Taichung and spent the night there.

The next day, they rented a car to travel to Sun Moon Lake for a missionary conference. During their trip south, they visited with different branches throughout Taiwan. Elder Vernon Poulter reported, “All the Elders were excited. . . . everyone was at the chapel waiting for Apostle Petersen. Perhaps this was going to be the only time that they would be able to see and listen to one of the Apostles of the Lord.” Many members missed school or work for an opportunity to meet a living Apostle.[9] Delays from a pair of flat tires prevented Elder Petersen’s ability to visit every branch on his way to Sun Moon Lake. Nevertheless, the impact on those he was able to visit was powerful. Sister Kuo Mei Hsiang (郭美香), who was baptized the previous year, recalled:

Soon after my baptism, the missionaries told me that Elder Mark E. Petersen . . . of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles was coming to Taipei. They asked me if I wanted to go. Right away I thought about the Apostle Peter in the New Testament and realized what a great opportunity it would be for me to meet an Apostle. I went to Taipei. After the meeting, I met Elder Petersen and his wife. They were very kind to me. I felt my blessings were great, and I wanted to shout for joy![10]

At Sun Moon Lake, Elder Petersen held a combined district conference for all the missionaries in the island. President Heaton remembered that “the Spirit of the Lord attended this meeting and the Holy Ghost was truly with every one of us.” On 27 May, the Petersens, the Heatons, and all the missionaries gathered for an inspiring testimony meeting.[11] The Petersens and their escorts continued on to visit the branches in the Southern District.[12] Elder Walker recalled the following of the experience:

In Kaohsiung, where the missionaries have been teaching English and religion at a local high school, the students made a sign that read “WELCOME TO KAOHSIUNG WELCOME ELDER PETERSEN.” Elder Petersen spoke to over a hundred people, including missionaries, members, students, and investigators.

The thrill of meeting and hearing Apostle Petersen, was easily visible upon the faces of the members. It seemed that all people, Elders, members, and non-members, all to some degree felt the spirit of his coming. The visit has prompted many questions concerning the organization of the Church and has helped the members understand the General Authorities of the Church.

Probably the greatest visible outcome of Apostle and Sister Petersen’s trip is the reality and nearness that the people feel toward the Twelve Apostles of the Church.

The Elders of the Branch gained an added desire to fulfill their assignments, through the close association they were able to feel with Elder and Sister Petersen.[13]

On 30 May, Elder Petersen traveled back to Taipei and held leadership meetings at the Taipei Mission home for branch leaders. The meeting held between 10 a.m. and 12 noon provided instructions on how to be an effective and successful leader, with a focus on service. The afternoon session between 2 p.m. and 4 p.m. explained each auxiliary organization in detail, including Sunday School, MIA (Mutual Improvement Association), Primary, Relief Society, and so on. Then in the evening, a special “Gala Talent Show” was held at the Taipei American School. Each branch contributed to the show, and the auditorium was filled with members and nonmembers alike. Elder Thomas Nielson reported, “It was a busy, inspiring day, and all the people who attended the sessions, or the talent show, learned a great deal and enjoyed themselves. The members of the Church, especially, had their testimonies strengthened with all that happened this day.”[14] On 31 May the Sunday morning session was held at the First Girls School. Nielson remembered, “All that attended were on the edge of their seats, eagerly listening to the words that this special person [Elder Petersen] had to relay to us.” In the afternoon session, Elder Petersen spoke of the early pioneers of the Church and how each Chinese convert was also a pioneer.[15]

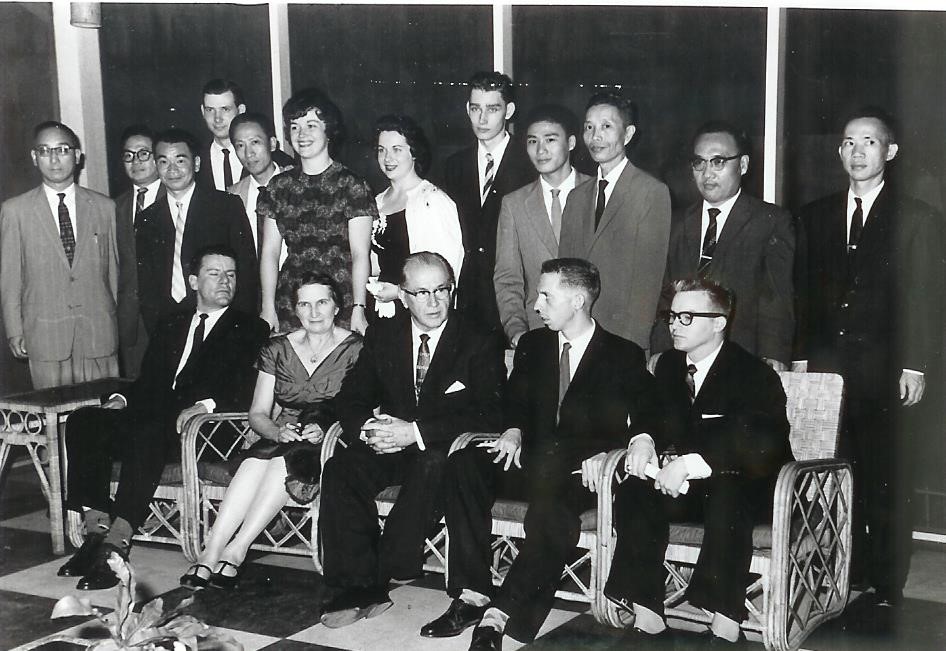

Dedication of Taiwan for the preaching of the gospel by Elder Mark E. Petersen of the Quorum of the Twelve in June 1959. From left to right: Hu Wei-I, Dong Jia-Xue, Chen Meng-You, Elder Petersen and his wife, Emma, Yin Qi-Wen, Qiu Xiu-Ping (or Chiu Mu Tsung (First Chinese convert in Taiwan). Courtesy of Taipei Service Center.

Dedication of Taiwan for the preaching of the gospel by Elder Mark E. Petersen of the Quorum of the Twelve in June 1959. From left to right: Hu Wei-I, Dong Jia-Xue, Chen Meng-You, Elder Petersen and his wife, Emma, Yin Qi-Wen, Qiu Xiu-Ping (or Chiu Mu Tsung (First Chinese convert in Taiwan). Courtesy of Taipei Service Center.

Then on Monday, 1 June 1959, several missionaries and members of the Church gathered at the end of Chung Shan Pei Road, in the shadows of the Grand Hotel, for a meeting to dedicate Taiwan for the preaching of the gospel.[16] Those that came gathered on the steps outside the Grand Hotel, then one of the largest and most magnificent buildings in Taiwan. Nielson recorded:

Monday morning was a little cloudy, the angels in Heaven were watching over us and were ready to cry with joy. . . . The saints who were able, met at the Grand Hotel, which is a beautiful site. There, with Apostle Petersen, we proceeded to have a dedication ceremony for the Island of Taiwan. After the opening exercises a quietness filled those who attended so that the dedication prayer could be heard and absorbed by all. As the Apostle opened his mouth to dedicate Taiwan to the preaching of the Gospel, the Holy Ghost entered and spoke the words that God wanted to be said, and every active member there realized this. Words of prophecy poured forth from his mouth, which will soon be fulfilled.[17]

During the dedicatory prayer, Elder Petersen expressed gratitude for the “general dedication of the Far East for the preaching of the gospel” by President David O. McKay, adding:

Father, we are grateful for the missionary work that has been accomplished in the last few years here on this particular island. We are thankful for the dedication of the missionaries and for the reception of the Saints. . . .

Father, may we have the liberty to go about from house to house. We pray that Thy Spirit may reach mightily upon all the people of this island that they may have respect for the presence of the missionaries and that the missionaries may be emissaries of God. . . . We pray Thee, our Father, that Thou wilt let Thy spirit and blessings be her upon the people, upon the missionaries, upon all Thy purposes as they are carried forth on the island. . . .

We pray that Thou wilt dedicate the island. We pray that the members will dedicate themselves to the work, that their friends and neighbors may receive the blessings of the everlasting gospel. We pray that they will invite their friends and relatives to come to our meetings, that they will introduce them to the missionaries so that the missionaries may teach them in cottage meetings.[18]

After the dedication, the Saints came to the airport to bid farewell to Elder and Sister Petersen and President Heaton and his family. They sang “God Be With You Till We Meet Again” to their departing visitors. Elder Petersen’s visit left a deep impression in the hearts and minds of the members and missionaries in Taiwan. The first visit by an Apostle of the Lord would remain in their memory throughout their lives.[19] Elder Gary Williams summarized the visit:

It was apparent that the visit of Brother Petersen, caused [the members] to feel . . . a part of [the Church]. . . . Brother Petersen’s visit has aroused many questions among the people and has created a much greater interest toward the Church.

The most impressive result of his visit is the effect that it has had [on] the Elders. Although it had some effect on all of the Elders, it had a greater effect on the Elders that have been here for a longer period of time. It has given them a few sparks and stronger desire to do the Lord’s work. In speaking with them, they also expressed the thought that they too felt a part of the church’s enormous organization. Previously, it has been remarked how much alone they have felt, but the visit of Brother Petersen rejuvenated them, and they again feel more part of this great missionary system. The spirit of his visit has keenly been felt by members, Elders and investigators alike.[20]

President Heaton’s wife, Luana Heaton, added that “the Petersens’ . . . visit had great impact on members, non-members and missionaries alike. For those who associated with them . . . it left a lasting impression that was needed. It was important to the people of Asia to know and have confirmation from an Apostle of the Lord, that what they had been taught by the missionaries was indeed the Restored Gospel of Jesus Christ.”[21] At last, the apostolic keys were turned, and Taiwan was dedicated for the preaching of the gospel.

Local Missionaries from Taiwan

Associated with the apostolic dedication was the addition of local missionaries during this period. Like early pioneers of the Church, many early Chinese converts in Taiwan exercised great faith and sacrificed much to join the Church. For those Chinese Saints called to serve as full-time missionaries for the Church, an even greater measure of dedication, devotion, and discipleship was required. The conversions and missionary experiences of Sister Kuo Mei Hsiang (郭美香), Elder Chen Kun-huang (Charles) (陳坤煌), and Elder Chen Yung-Chu (Larry) (陳勇助) are but three of the many stories of the sacrifice and service of early missionaries from Taiwan.

Elder Chen Kun-huang (Charles) is believed to have been the first local male missionary in Taiwan when he was called and began to serve in September 1960. Elder F. Dennis Farnsworth reported that he was surprised when President Taylor, the mission president, came to the island and told him he was moving and getting a new companion. In a letter to his family on 27 February 1961, he wrote, “Moving to Keelung. My companion is elder Chen, the only local missionary here in Taiwan. It is certainly a joy to work with him, to feel his spirit, and to labor with him in this work.” According to Farnsworth, “The people place such confidence in him. He is truly a wonderful missionary. It certainly feels good to be proselyting again. Farnsworth adds in another letter than Chen was born in southern Taiwan, had eleven people in his family, and graduated from the Taipei National Institute of Technology.[22] In a letter dated 13 March 1961, Chen wrote the following to Farnsworth’s family:

I am Elder Charles Chen (Chinese name is 陳坤煌). I have been Elder Farnsworth’s companion for three weeks. I was born in this island which is called Formosa by foreigner, but is called Taiwan by our own people. About six months ago I was called to be the first male local missionary in this island . . .

About four years ago, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints started to preach the true gospel in here. Many elders have been sent to this island to teach my people the restoration Church’s gospel. I am very thankful to our heavenly Father for the gospel. Through it we can gain the salvation of God. All our people are thankful to those who taught and have taught the gospel in this island.

Elder Farnsworth has been here for four months. . . . We go out to proselyte every day except Monday. We have got a lot of investigator now. I am sure that we shall baptize someone in the end of this month.[23]

Farnsworth noted that his companion was a senior elder in the island and knew much about the Chinese people and about teaching the gospel to them. In addition, his companion had many responsibilities, including writing a language book for the missionaries.[24]

Sister Kuo Mei Hsiang (郭美香) was fourteen years old in 1957 when the missionaries taught her and her parents about the fourteen-year-old boy named Joseph Smith. Although her parents asked the missionaries not to come back again, Kuo attended the English class at church, prayed and gained a testimony of the Joseph Smith’s First Vision, and desired to be baptized. But her parents said that “if [she] joined the Church, [she] would not be their daughter anymore.”[25] Kuo recalls:

In September 1958 I was baptized. What a beautiful day it was! I do not have the words to describe the joy I felt that day. My parents did not come, but when I came home, they did not scold me or get angry. I was grateful for that . . .

Unfortunately my parents grew upset again about my becoming a Latter-day Saint. If I blessed my food, my brother took it away from me. If I went to church too much, I got in trouble. Except for my two younger sisters, it seemed everyone in my family was against me and had sharp words for me. It was very difficult. They even read my diary. One of the most heartbreaking things happened when my father tore apart my Bible. I remember how I cried for days afterward. Now I had no scriptures to read. Countless nights I lay on my bed facing the wall and praying to my Heavenly Father.[26]

Afterwards, Kuo’s father was out of work, and she found a job to help support the family. This was a blessing to her family. In addition, her two younger sisters also got baptized during this time. However, her parents got upset again when Kuo quit her job in 1964 to accept the call to serve a mission for the Church. During her mission, she wrote her parents a letter to share her testimony and tell them about a dream she had about her deceased grandfather.[27] She continued:

I didn’t know it at the time, but my father was also very ill. . . . My mom asked all kinds of doctors for help. She even went to the Buddhist temple to ask for help. Nothing happened. In fact, my father got even sicker. Two sister missionaries talked to my mom about the healing power of priesthood blessings, so my mom asked the elders to give my father a priesthood blessing. Right after that, my father began to get well. It was during this time that my letter arrived. My dad’s heart was softened as he read about my dream of my grandfather coming to see me. He felt it was true. My testimony helped him to decide to join the Church, but I did not know that at the time . . .

One day my companion told me we had an assignment to go to Tainan. I was shocked. I told her I did not want to go home. She said, “We are not going to your home. We need to visit the Tainan branch.” I felt very strange. During the six-hour train ride, my emotions were like a roller coaster as I wondered why. When we walked inside the Tainan branch, I saw my parents both dressed in white baptismal clothes. What a wonderful surprise! I thanked Heavenly Father for helping my parents gain a testimony of the gospel.[28]

Kuo later reported, “I have been blessed with a loving husband who holds the priesthood. . . . [We] have been sealed for time and all eternity. I have been sealed to my parents also.” Kuo didn’t realize back then that she, along with her husband and many other early Chinese members, were pioneers of the Church in Taiwan.[29] Although they struggled against generations of tradition, their faith and sacrifice have blessed them, their families, and countless generations.

Another early pioneer to serve as a missionary for the Church was Elder Chen Yung-Chu (Larry) (陳勇助). He joined the Church on 11 October 1964 after working with his brother at the construction of the Chin Hua Street chapel in Taipei. According to Chen, although there were other local sister missionaries before, he was among the few local proselyting elders from Taiwan when he began his mission in December 1965. Even before he was baptized, Chen wanted to serve a mission. However, Chen recalled that one did not apply for a mission during those early years:[30]

Back then, you don’t submit a request for a mission. It was depended on your branch president to recommend you for service. I really wanted to serve a mission, and prayed that I might be called to be a missionary. So I did my best to serve faithfully at Church so I might qualify. About seven or eight months later, the branch president called me to be a full-time missionary. In December 1965, I received the call to be a missionary from President David O. McKay. When I received my mission call, . . . I was very excited, even though I had no money.

The mission wanted to have a local elder called. . . . Due to military obligation for the brothers, the Church then only called sisters. But because I had already finished my military service, I could go.

I had no suit, or anything, . . . but other missionaries donated money to buy me a suit and white shirt, bicycle, and so forth . . . to help me on my mission. Elder Bob Morris helped me a lot.[31]

In December 1965, Chen’s missionary farewell was held at the yet-to-be-dedicated Chin Hua Street chapel. Hu Wei-I (胡唯一), a counselor in the mission presidency, conducted the meeting and said, “If any of you have the desire and the possibility to serve a mission for the Church, let your branch presidency know. . . . The greatest work you will do will be to teach the Gospel to your parents.” Chen’s father thanked everyone for coming to bid farewell to his son. At last, Chen stood up and said, “Why do I want to be a missionary? . . . I guess there are two reasons. . . . One day the sisters taught me the third lesson. I had a secret desire to be a missionary then. I decided I wanted . . . to serve God.” After he spoke, the congregation sang “The Spirit of God.” The closing prayer included, “We know that he [Chen] is a good Latter-Day Saint, but still he needs the help and blessings.” Following the meeting, there were pictures with his parents and others, congratulatory wishes, and signing of a memory book. Members also gathered $450 to help him begin his mission.[32] The next day, Chen boarded the train to Miaoli to begin his two year mission. His first companion was Elder Miner.[33] Local missionaries then were not endowed because there was not a temple in Taiwan. Nevertheless, Chen gained a testimony and desire to go to the temple for his temple blessings. During a cold night in Miaoli, Chen said that his companion’s electric blanket burned up but did not harm this missionary because he was wearing his temple garments. Chen later served with Elder Bob Morris in Hualien, where he learned about priesthood power after they healed someone through a priesthood blessing.[34]

Chen and his brother regularly prayed and fasted for their parents. When Chen was serving in Tainan, about a year into his mission, he received a surprise. He was attending a mission conference in Taipei, and gifts were delivered for each missionary. Chen’s gift, they announced, was that his parents were being baptized. His younger brother, Chen Wu-Hsing (Ed) (陳武雄), said, “My parents saw their sons become better than they were before, and following this example, they began to listen to the lessons.” The younger brother baptized their parents, and the older brother performed the confirmation at the Chin Hua Street chapel.[35] Chen later served as a branch president in Taichung and then again in Changhua. In Changhua, a former branch president led several members to leave the Church, but Chen and his companion worked hard to bring them back. During this time, there were six missionary lessons. Chen used principles from these lessons, but utilized local examples to help the Chinese people he taught. He acknowledged the cultural differences and sought to use Chinese methods and examples to help teach the gospel during his mission.[36] Chen served faithfully as a young missionary from 1965 to 1967, and in 1985, he would be called to serve as the first Chinese mission president in the Chinese realm.

Many other early converts and local missionaries have experienced and continue to experience opposition from family and friends when they chose to follow the Lord and his chosen servants. Some have been blessed to see their family members accept the gospel in this life, but others may have to wait until the next life. Nevertheless, the Lord’s promises are sure and remain upon his chosen servants who obey his teachings and follow his living prophets.

Elder Gordon B. Hinckley Begins His Ministry among the Chinese

Elder Gordon B. Hinckley, then an Assistant to the Twelve, visited Taiwan from 18 to 20 May 1960 to preside over regional conferences in Kaohsiung, Taichung, and Taipei. This would be the first of his many trips to Taiwan throughout the 1960s and subsequent decades. Other members of the Quorum of the Twelve would also visit Taiwan in the 1960s, including Elders Howard W. Hunter, Ezra Taft Benson, and Bruce R. McConkie. However, no other General Authority would visit and supervise the work in Taiwan as much as Elder Hinckley. Decades later, he would note the following in regards to his relationship with the Saints in Asia:

Kuo Mei Hsiang's parents at thier baptisms on 24 October 1965 in Taiwan. From left to right (beginning third from the left): Kuo Tzunan, Kuo Mei Hsiang, Chuang Lan. Courtesy of Moyer family.

Kuo Mei Hsiang's parents at thier baptisms on 24 October 1965 in Taiwan. From left to right (beginning third from the left): Kuo Tzunan, Kuo Mei Hsiang, Chuang Lan. Courtesy of Moyer family.

I say with gratitude and in a spirit of testimony . . . that it has since been my privilege, out of the providence and goodness of the Lord, to bear testimony of this work and of the divine calling of the Prophet Joseph Smith in all of the lands of Asia, . . . [including] Taiwan. . . . I have testified in . . . all of the nations of the Orient in testimony of the divinity of this work.[37]

During Elder Hinckley’s first visit, Elders Thomas Nielson and Robert Suman were assigned to travel with him. Nielson was then the traveling elder in Taiwan (equivalent to an assistant to the mission president in later years), and Suman was his junior companion. They traveled by train to visit nine branches in eight cities, including the following: Keelung, Taipei (two branches), Hsinchu, Taichung, Miaoli, Tainan, Chiayi, and Kaohsiung. They utilized the service of local pedicabs in each city, and Elder Hinckley visited with and interviewed each missionary in the island. When Elder Hinckley returned in the spring of 1961, Suman was then the traveling elder in Taiwan. Suman recalled that rather than pedicabs, they now traveled in taxis.[38]

Elder Gordon B. Hinckley (third from left) visits Taiwan in the 1960s. Courtesy of Robert Suman.

Elder Gordon B. Hinckley (third from left) visits Taiwan in the 1960s. Courtesy of Robert Suman.

Elder Hinckley focused on at least two important efforts in Taiwan during the 1960s. These included the effort to translate the Chinese Book of Mormon and the construction of the first LDS chapel in Taiwan (discussed in the next chapter). This would be the beginning of Elder Hinckley’s decades of service and intimate relationship with the Saints in Asia. Paul Hyer, who later served as a mission and temple president, called Elder Hinckley “Mr. Asia.” Liang Shih-An (梁世安), who later served as a regional representative and the first Area Seventy from Taiwan, said that no other General Authority had come to Taiwan more or honored the early Chinese pioneers and leaders more than Gordon B. Hinckley. His deep appreciation for the Chinese people and its history and his service for them would span decades to come. For example, Liang noted that Elder Hinckley worked with many of the early local leaders, and years later he still remembered them and always invited these early pioneers in Taiwan to sit on the stand with him to honor them and show his abiding love for them.[39]

The Book of Mormon Translated into Chinese

When the Southern Far East Mission was established in 1955, access to a Chinese-language Bible was already available thanks to the efforts of early Christian missionaries. Although early drafts and partial translations of the Bible were started by various individuals and groups in the 1800s, the Protestant Chinese Union Version published in 1919 became the predominant and most widely used Chinese translation of the Bible. The Chinese Union Version helped to standardize gospel terminology and Christian vernacular in Chinese.[40] Although the Chinese Bible was helpful, the need for translated latter-day scriptures was vital to help preach the restored gospel.

Elder Ezra Taft Benson (Front and center) visits Taiwan in November 1960. Courtesy of Bob and Diane Murdock.

Elder Ezra Taft Benson (Front and center) visits Taiwan in November 1960. Courtesy of Bob and Diane Murdock.

The Book of Mormon, however, had not been translated at the inception of the Southern Far East Mission. Although the Prophet Joseph Smith said, “I . . . should be pleased to hear, that [the Book of Mormon] was printed in all the different languages of the earth,”[41] this task is not easy in any language, and Chinese proved to be particularly difficult as it does not use romanized characters. Moreover, differences between Cantonese speakers in Hong Kong and Mandarin speakers in Taiwan also contributed to the challenges of translating the Book of Mormon. Linguistic and cultural differences between those from the Far East and the West resulted in misunderstandings and communication problems which threatened the completion of the Chinese scriptures. One writer captured some of these challenges as follows:

Although a translation department was organized under the Missionary Committee in Salt Lake City after World War II, it grew out of and worked only with the major European languages. . . . In the summer of 1955, except for the Bible which had been translated by Protestants, there were no written materials in Chinese. . . . Over the next two decades a series of administrators from Salt Lake City, mission presidents, and translators labored to translate into Chinese the Mormon scriptures. . . . At times some of these men seemed to be struggling against one another, and a cataloging of the various false starts, delays, and misdirected attempts can only make one wonder if the resultant publications [of the Chinese scriptures] . . . were because of or in spite of their best efforts.[42]

The 1957–63 Early Drafts

In 1955, H. Grant Heaton became the first mission president of the newly organized Southern Far East Mission and immediately sought qualified individuals to translate Church materials by posting an ad in the South China Morning Post. Heaton learned Cantonese as a missionary in Hong Kong and later learned Mandarin as he worked for military intelligence questioning Chinese prisoners during the Korean War. Early efforts included the translation of tracts and pamphlets as well as other Church materials.[43]

By 5 September 1957, Heaton organized a translation committee in Hong Kong to work on the Chinese translation of the Book of Mormon. A multiplicity of issues hindered the efforts of this committee. These translators were unable to focus on the translation of the Book of Mormon due to their time spent translating other Church materials or searching for better employment opportunities. Most of the translators were new converts with limited doctrinal foundation and gospel understanding. They also lacked sufficient training, had poor communication with each other, and struggled with coordinating their efforts. The translated drafts from this committee, which were reviewed by Heaton, had serious mistakes and required major revisions. In addition to these problems, because various committee members worked on different parts of the scriptures, there was a need to bring consistency throughout the entire manuscript. Ultimately, these early efforts did not result in a completed translation.[44]

Although Heaton released an early draft of the Chinese Book of Mormon in 1959, there were major errors and inaccuracies, and additional work was needed to edit and proofread the manuscript. Heaton sent a report and the draft of the manuscript with his suggested edits to the Church Translation Committee, but the work was terminated without further explanation. Nothing else was done between 1959 and 1963, partly due to the lack of Chinese proficiency of the mission presidents who followed.[45] Three or four partial translation drafts came from these early efforts in Hong Kong.[46] Robert J. Morris recounted a conversation with Elder Marion D. Hanks of the First Quorum of the Seventy explaining why it would take a decade to translate the Chinese Book of Mormon:

In 1966, I asked Marion D. Hanks why the Church had been in the Chinese Mission for a decade without a Book of Mormon. In substance he said we had not had anyone in the Church of sufficient spiritual expertise to translate it well enough. We could have hired it done, but it would have lacked the spirit that only a faithful member-translator can give it.[47]

Finding and Teaching Hu Wei-I

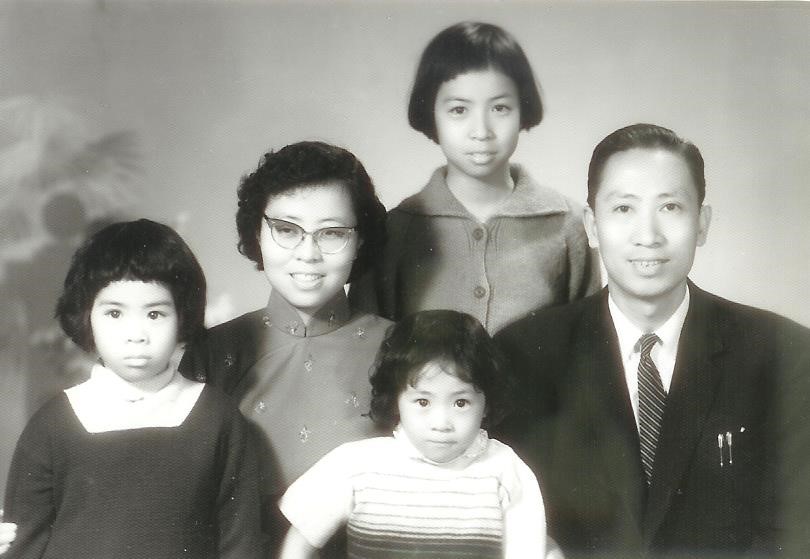

Hu Wei-I and his family in December 1961. Hu was the principal translator of the Chinese Book of Mormon. Courtesy of Bob and Diane Murdock

Hu Wei-I and his family in December 1961. Hu was the principal translator of the Chinese Book of Mormon. Courtesy of Bob and Diane Murdock

Elder Vernon C. Poulter was among the missionaries in the Southern Far East Mission that was assigned to labor in Taiwan in 1958. After Poulter and his companion, Elder Daws, prayed “to be led to someone that [had] been prepared to hear the gospel,” they waited to “receive the Spirit’s direction.” They followed a series of impressions to “turn right” or “turn left” on their bikes until they stopped by an alley. Poulter explained, “I saw a man watching us very intently through an open window. We were only a few feet apart. Our eyes met and I knew he was the person to whom we had been led. I spoke to him through the open window and . . . He invited us in.”[48]

The man who invited them in was Hu Wei-I (胡唯一). Elder Daws taught the first lesson about Joseph Smith and the need for modern-day prophets. Hu accepted this principle and asked, “Since Joseph Smith saw God and Jesus Christ, he is the most important person of our time, [so] how should I honor him?” Hu also asked, “Why hasn’t there been any prophets since the time of Christ until Mr. Smith?” Elder Poulter shared The Great Apostasy pamphlet with Hu, who knew English.[49] Poulter shared his experience when they returned to Hu’s home:

I could see a light, emanating from our contact’s window. I remember it as a “pure, white light.” As we entered, . . . the whole room was bathed in a pure light; it spilled out into the alley and shown on the house across the alley. . . . It was as if the space within the room itself was radiating. . . . It was clear to my mind that we were in the presence of the Holy Ghost . . .

We had planned to give the next lesson in the series, but Mr. Hu asked that we repeat the story of Joseph Smith for his wife and children. At the end of the lesson, he bore his own testimony then gave his own lesson to his family based on his reading of the pamphlet that we had left yesterday. His understanding and sincerity was most impressive. He closed, stating that these elders were bearers of the truth and asked his wife to join him in further investigating the Gospel.[50]

Hu also told the missionaries that his neighbor gave him a hard time about the “foreign-devil missionaries” and asked for permission to translate the pamphlet into Chinese for his friends and neighbors. This would be Hu’s first experience translating Church materials into Chinese. Brother and Sister Hu and their two daughters attended church with the missionaries the following Sunday.[51]

Poulter said that before he came to Taiwan, he went with his father to purchase Talmage’s Jesus the Christ and Articles of Faith. His father also bought him Gospel Doctrine, Doctrines of Salvation, Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, A Marvelous Work and a Wonder, and The Great Apostasy, “just in case.” While Hu was still investigating the Church, Poulter received a transfer and received another impression:[52]

As I started to pack the books my dad had sent with me. Once again, I had the strong impression, “Give the books to Mr. Hu.” After all, dad had said, “If you need more, just let me know.” I knew dad would be happy to replace them. Chinese people do not like to accept gifts from new acquaintances, especially something as personal as books. I was afraid that he would reject the books. However, the inspiration was undeniable.

Elder Daws and I loaded the books on our bikes and took them to Mr. Hu’s home. He was in and greeted us warmly. I told him that I was being transferred, and that I had been impressed to give him my books. His reaction was joy at receiving the gifts. There was no show of false modesty or pride. He was simply thankful to receive them so he could “study the gospel in depth.” He accepted the gift with a warm gesture of thanks and western style handshake.[53]

In 1958, there were no Chinese Church materials, so Hu studied the doctrine of the Church using these English books given to him. Hu indicated that this helped him when he was later called to translate the Chinese Book of Mormon. It took a few months before Hu finished the seventeen missionary lessons. Hu recalled that many times he had to find the answer to his own questions because the missionaries did not speak Chinese well enough to respond beyond their memorized lessons.[54]

Other missionaries beside Elders Poulter and Daws also had the opportunity to teach Hu. When Elder James Goodfellow was first transferred to Taipei, he was introduced to Hu Wei-I. Goodfellow recorded, “We truly had no idea what a powerful and lasting impact we would have on the lives of those we taught, and upon the building of the kingdom, as we daily performed missionary work with those we learned to love in Taiwan.”[55] Goodfellow shared of the humility he saw in Hu:

Hu Wei Yi was a very humble person. He asked interesting and often penetrating questions. Often I did not know the answer to his questions and explained that I would research the answers and bring them back to him. I had no knowledge that Elder Poulter had provided any gospel books to him previously, nor did he volunteer that he in fact possessed the LDS books. . . . He was always kind, serious and gentle in his probing for understanding. He accepted the gospel as we explained it but was always interested in a thorough understanding, which was unusual for investigators.[56]

After ten months, Hu felt embarrassed that he was investigating the Church for such a long time, so he finally decided to quit smoking and drinking. He said that once he made the decision, “I quit all at once. I gave [up] my cigar, cigarettes, and all my pipes.” Following the seventeen-lesson series and five sets of missionaries, Hu was baptized on 24 December 1958.[57] Hu was baptized by Elder Murdock and confirmed a member of the Church by Elder Goodfellow.[58]

Hu did not attend high school or college, but he had served as a colonel at the military academy in mainland China before moving to Taiwan. Although his income was limited, he was taught and obeyed the law of tithing. President Gordon B. Hinckley shared the following in 2005:

The Hu family was taught about the law of tithing before joining the church.

However, his wage made it very difficult for the couple to obey. After some discussion, sister Hu insisted they obey the law. So they paid their tithing.

“Now what we are going to eat?” Brother Hu asked.

The next day, Brother Hu’s supervisor gave him an envelope saying that Brother Hu was a good worker and he was going to give him a raise. When he opened the envelope, he found the same amount of money he had paid for tithing.[59]

Accepting and living the law of tithing and the Word of Wisdom prepared Hu to be worthy of the companionship of the Holy Ghost, which was important as he sought to translate the Chinese Book of Mormon. Being worthy of the Spirit was crucial, as the translation of the scriptures could not be accomplished by man alone. After Hu was baptized with his wife and daughters, he translated into Chinese the LDS books Poulter had given him.[60] His greatest contribution, however, was the translation of the Chinese Book of Mormon. Hu’s experiences translating a missionary pamphlet and other Church materials, as well as translating a draft of 3 Nephi, were necessary preparations. These experiences helped to train, prepare, and refine his translation skills, along with the development of his doctrinal understanding of the restored gospel, which would be important as he was later tasked with the translation of the Chinese Book of Mormon.

Translation Restarted Despite Misunderstanding and Cultural Differences

Robert S. Taylor became the mission president after Heaton was released. On 7 August 1962, Taylor called a few individuals to complete partial translations.[61] Nothing more was done until a new translation effort was restarted when Jay A. Quealey Jr. arrived to serve as the mission president of the Southern Far East Mission.[62]

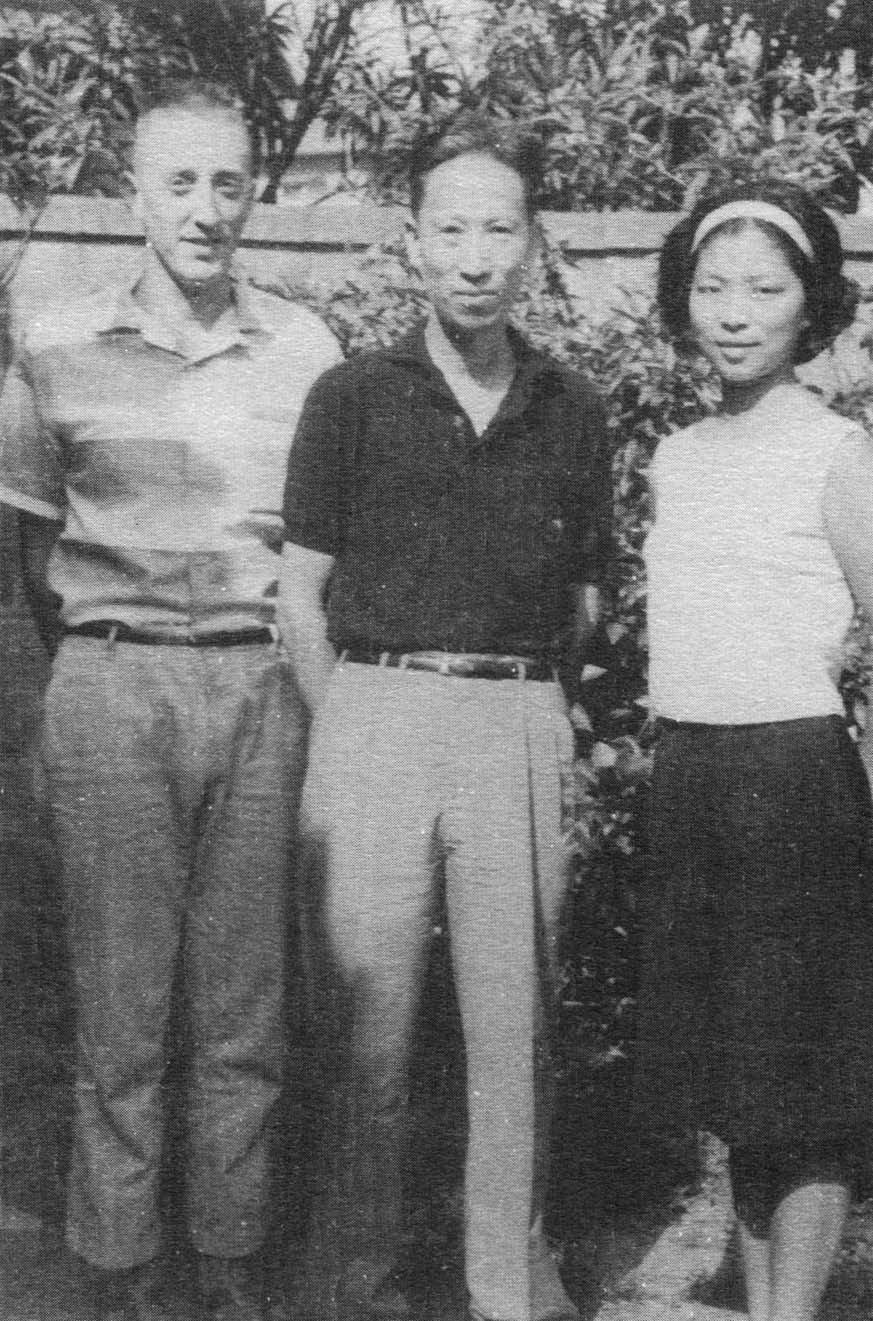

Larry Browning and Hu Wei-I in 1964. Courtesy of Richard Stamps and Wendy Jyang.

Larry Browning and Hu Wei-I in 1964. Courtesy of Richard Stamps and Wendy Jyang.

Larry Browning, who served for three years as a young missionary in Hong Kong, came to Taiwan in 1962 on an education grant from the University of California after finishing a master’s degree in Chinese literature at Stanford University. In 1963, President Quealey asked Browning to review the partial translations completed by different individuals and to select the best one. The partial translation by Hu Wei-I was selected by Browning as “the most readable.”[63] Hu was then serving as a counselor to the mission president in the Taiwan Zone.[64] In 1963, then Elder Gordon B. Hinckley from the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, who supervised the work in Asia, called and set apart Larry K. Browning and Hu Wei-I separately to start anew the translation of the Book of Mormon into Chinese.[65] Elder Hinckley said that this work was “the most important thing taking place in the Far East.” Although both Hu and Browning sincerely desired to bring forth a suitable translation, misunderstanding and cultural differences contributed to a tense relationship between them throughout the translation process.[66] According to Diane Browning,

The most serious hindrance to their work was simply a misunderstanding of their positions. The plan for the translating work as Brother Browning understood it, was that President Hu would do the initial draft, which Brother Browning would then review. Then, together, they would go over the work for a third time discussing the corrections suggested . . . and hopefully agreeing on a final version. The serious flaw in this plan emerged during this third stage, . . . as neither of them had been specifically designated as “final authority.” In other words, no one was in charge. . . . Some of their lack of communication can be attributed to cultural factors, some to the personalities of the two men. . . . In any case, they were far into the work before it became apparent that they each had a different concept of how the work was to progress.[67]

The misunderstanding between Browning and Hu was at least in part attributed to the cultural differences and competing perspectives. Although Browning had been a missionary in Hong Kong and studied Chinese literature, he may have approached the relationship from a Western perspective. On the other hand, Hu was a convert from Taiwan and more likely viewed things from the perspective of someone who grew up in the Far East. Browning’s strength was his understanding of the doctrine and the English language, while Hu’s strength was in his command of the Chinese language.

Hu noted the differences between the Chinese and Westerners as follows: “We Chinese are a little different from Westerners. The Westerners are from stock that have had the Gospel and many have hardened their hearts against it. We have not. . . . There are many parts of the Book that apply to us directly. . . . There are so many good moral analects and standards.”[68] Browning recognized challenges with the Chinese translation of the scriptures. He noted that the “Chinese translation of the Bible . . . [was] done by someone trained for many years in the target language with the help of natives who know some English. Their approach is to be readable at the expense of direct accuracy.” Their dilemma was to choose between “accurate, but not always very readable vs. readable, but not totally ‘accurate.’”[69]

Moreover, both Browning and Hu had different perspectives regarding each of their roles in the translation effort when Elder Gordon B. Hinckley called and set them apart in separate occasions to work on the translation. Browning recorded that he was called on 31 July 1963 to “supervise the translation of the Book of Mormon into Chinese,” while Hu’s perspective was that he was assigned to “translate the whole Book” when he was called and set apart on 5 November 1963.[70] Perhaps if they had been jointly called with clear expectations, some misunderstandings could have been prevented. A tense morning in June 1964 revealed the tremendous difference on how they each saw their respective roles in regards to the work of translation. The following relates the experience:

In a frank discussion taking up most of one morning, Brother Browning, who had been called “to supervise the translation,” explained that he felt that at the very least the two of them should be partners. President Hu, who had not been present at the time Brother Browning was called and set apart, was under the impression that he was to be the translator of the Book of Mormon. He understood that Brother Browning was to be his helper and should restrict his activities to renting offices, buying desks, and sharpening pencils. He never understood the purpose of the third step in the plan, so all along had not been concerned about allowing time for it, and had felt Brother Browning was pressuring him needlessly to work faster.

This discussion, while it explained what was causing their difficulties, did not really solve anything and they continued to work in a strained atmosphere.[71]

Browning also explained that he purchased a safe to store the manuscript. He had the Book of Mormon in various languages, a complete set of Book of Mormon concordances, and several English-Chinese dictionaries. He anticipated the translation process to work as follows: Hu would do the initial rough translation, Browning would review and annotate places requiring changes, and then they would work together to finalize changes. On a typical day, Browning would meet Hu in the morning and pick up and review between two and four translated sheets. Since the review process was faster than the initial translation, Browning used the extra time to procure a printer, work on the layout, and find other members to help make copies of the manuscript, which were done by hand with carbon paper. There were a total of four copies, the original copy by Hu, a copy for the printer, and one each for the Hong Kong and Taiwan offices. According to Browning, the main problem was that Hu was thrown off by the use of idioms or the old English. However, Browning also noted that the problem “was that a translator puts so much into thinking through the meaning and putting it into the target language that he can’t be satisfied with a rough translation.”[72]

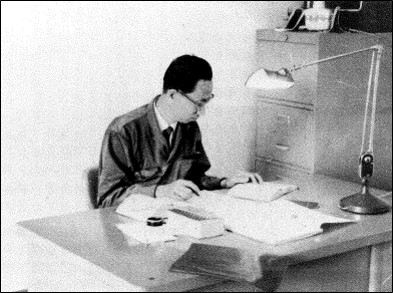

Hu Wei-I working at this desk on translation of the Chinese Book of Mormon, circa 1965. Courtesy of Richard Stamps and Wendy Jyang.

Hu Wei-I working at this desk on translation of the Chinese Book of Mormon, circa 1965. Courtesy of Richard Stamps and Wendy Jyang.

Hu began translating part-time until he was able to get leave without pay from the Civil Air Transport in Taiwan. Time pressure also appeared to add tension to the delicate relationship between Browning and Hu. Hu was given six months leave from the Civil Air Transport, while Browning was planning to begin his teaching position at BYU–Hawaii in September 1964. Browning suggested to Hu that the initial translation and review should move faster so as to allow more time for their final review together. However, Hu felt “pushed” by Browning’s suggestion. Hu felt he needed to take more time in the initial translation and did not see the final review requiring much time. Both men seemed to have different views on how the project should proceed. One felt more time was needed up front; the other felt more time would be needed toward the end. President Quealey, the mission president at the time, visited in February and encouraged them to pray together to help bring unity; however, personal differences persisted:[73]

Later that spring, the translators were finally able to agree that they were both too stubborn to work together! A disagreement over fundamental policy was recognized. President Hu wanted to remain absolutely faithful to the English original, while Brother Browning felt some leeway had to be taken in order to make acceptable reading. They finally decided that this basic policy decision would have to be made on a higher level of authority. . . . President Quealey cautioned against changing anything, but he had no experience in languages. Elder Hinckley declared, “We must have a faithful and readable translation.” This seems on the surface to be a good approach but as they worked they found many questions involved a choice between the two to some degree, so, in fact, the advice was not much help, and the translators continued without an overall policy.[74]

President Quealey was visiting Taiwan in August when he was called to mediate another disagreement between the two. Browning became “too intense” defending his position, and Hu was ready to quit the translation project. Quealey told Browning “to keep the peace” and to reduce his suggestions to only gross mistakes so as to allow the work to be completed. Browning accordingly erased most of his suggestions and corrections, and supervised the final triplicate copies.[75] Still, from Browning’s perspective, there were many mistakes with the translation; Hu was not a trained writer, and his dialect was not standard.[76]

Other challenges were encountered during the translation process. For example, Hu used the Chinese Bible as the reference in working the Isaiah chapters found in the books of Nephi, but he did not like that Bible’s translation because in many cases “the doctrine and meanings [were] translated wrong.” Consequently, he redid the translation. Hu noted that “a translator must be careful not to translate doctrine according to his own opinion, but as what is literally intended in the original. If it is otherwise it is dishonest.”[77]

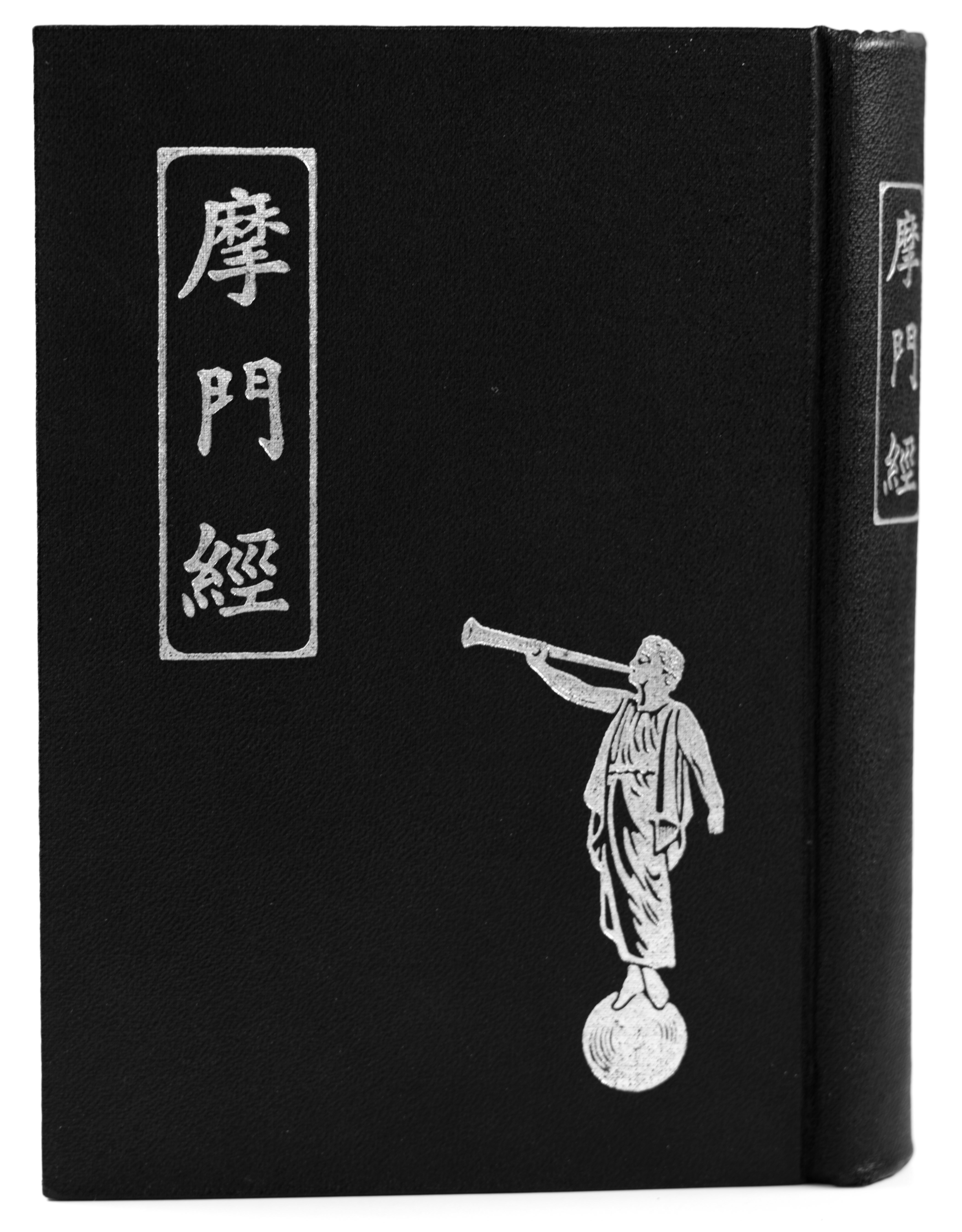

First Chinese Book of Mormon Published in 1965

Hu kept the English Book of Mormon he had used for the translation as well as the original translation he handwrote in green ink. On 19 July 1964, following the completion of the translation, Hu began proofreading the translation and had four sisters from the Church helping to make three additional copies of his original manuscript, including a copy for Hong Kong and one for Taipei. Browning left Taiwan and returned to the United States to accept a teaching position in September 1964. These sisters finished the copies on 24 October 1964, and Hu finished the translation review shortly after. Hu lamented, “It took me seven months [to translate the Book of Mormon, while] Joseph Smith only needed two.” Although Browning had asked Hu to move faster, Hu’s account suggests that he felt he was already doing that. In their own way, both men pushed hard to get it done. With the budget approved in June 1965, the manuscript was prepared for publication. The Chinese Book of Mormon was published December 1965, and Hu proofread the published book between February and March 1966, noting few typographical errors.[78]

First edition of the Chinese Book of Mormon, published in 1965. Courtesy of Tyler Thorstead.

First edition of the Chinese Book of Mormon, published in 1965. Courtesy of Tyler Thorstead.

After the Chinese Book of Mormon was published, Hu would write that “the translation was done through much prayer and fasting by the leaders, missionaries, and members of the Church in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and states, also through the Holy Ghost and power from on high, yet errors are unavoidable because of my weaknesses.”[79] President Keith M. Garner, who replaced Quealey as the new mission president in August 1965, said that the “quality of the book is excellent. There are a few errors, naturally, but on the whole there had been very little criticism and everyone seems delighted. It will stabilize the Church . . . and bring stronger testimonies.”[80] There were somewhere between three thousand to five thousand copies printed in the first edition on 20 December 1965.[81] This first edition had a black cover with a gold-embossed Angel Moroni.

Elder Gordon B. Hinckely presents a copy of the first edition of the Chinese Book of Mormon to President David O. McKay on 29 January 1966. Courtesy of LDS Church. By Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Elder Gordon B. Hinckely presents a copy of the first edition of the Chinese Book of Mormon to President David O. McKay on 29 January 1966. Courtesy of LDS Church. By Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Elder Gordon B. Hinckley, then the member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles assigned to supervise the work in Asia, delivered a copy of the Chinese Book of Mormon to President David O. McKay, who forty-five years earlier had dedicated the Chinese realm for the preaching of the gospel. Elder Hinckley’s inscription in the copy given to President McKay on 9 January 1966 said:

This copy of the first edition of the Book of Mormon in Chinese presented to President David O. McKay, who 45 years ago, on January 9, 1921, accompanied by Elder Hugh J. Cannon, in the “Forbidden City” of Peking dedicated and consecrated and set apart “the Chinese realm for the preaching of the Gospel of Jesus Christ as reported in this dispensation through the Prophet Joseph Smith.”

The Book of Mormon is now available in the language which is the mother tongue of more people than any other on earth. May it go forth among them as a witness of the Son of God, the Savior of the world.

With sincere respect and deep affection,

Gordon B. Hinckley[82]

At a fireside in Kaohsiung years later, Hu Wei-I reported that Elder Gordon B. Hinckley took the first three copies of the newly printed Chinese Book of Mormon: one for Hu, one for President McKay, and one for the Church archives.[83] Elder Hinckley noted, “The Book of Mormon is now available in the language which is the mother tongue of more people than any other on earth.”[84] It was in the language of seven hundred million Chinese people in 1966. He also said that it would “give a tremendous boost to missionary work being done among the Chinese people.”[85] When President McKay received the Chinese Book of Mormon, he said the following:

This is a great event in the history of the Chinese people. This brings back many fond and delightful memories, and especially of a warm and most delightful day in the early morning, 45 years ago, when I went with Brother Cannon . . . [and] we offered the prayer dedicating China for the reception of the Gospel.[86]

Elder Gordon B. Hinckely receives a painting of President David O. Mckay by an investigator in Taiwan in 1966. Painting depicts President McKay in traditional Chinese robe. Courtesy of Phil and Brenda Frandsen.

Elder Gordon B. Hinckely receives a painting of President David O. Mckay by an investigator in Taiwan in 1966. Painting depicts President McKay in traditional Chinese robe. Courtesy of Phil and Brenda Frandsen.

Subsequent Editions of the Chinese Book of Mormon

The relatively small first printing necessitated other printings soon after the first. The second edition followed, with 2,500 copies printed in June 1966 by Wing Tai Printing Company, and another 2,500 copies printed in August by Chen Tsun Stationery Company.[87] These served the needs of the missionaries and members in Hong Kong and Taiwan. Hu Wei-I made a few minor corrections from the first printing and was listed as the translator in this edition. The June version had a blue softbound cover, while the August version had a red or gray hardbound cover (this is the only version with a red cover). A third edition followed in January 1967, with 2,500 copies with a blue softbound cover and few changes. The fourth edition produced in October 1967 had both a blue softbound cover as well as a black hardbound version. The most significant addition was the “索引,” an index with a glossary of terms for this edition. In May and October 1969, ten thousand followed by thirty thousand copies were produced for this fifth edition, published by Luen Shing Printing Company. This was the first copy with the new cover style similar to those produced in other languages.[88] These almost annual productions of small print runs of the Chinese Book of Mormon were, however, an inefficient and expensive way to produce the book.

In 1969, W. Brent Hardy became the mission president for the Hong Kong–Taiwan mission. Hardy believed that because copies of the Chinese Book of Mormon would be distributed quickly, he could save money per unit copy by dramatically increasing print run of the next edition. With minor changes and the addition of color pictures, Hardy published one hundred thousand copies for the sixth edition in 1970. Unfortunately, distribution was slower than anticipated, leaving tens of thousands of unused copies that began molding in the hot and humid climate in Taiwan, while also “preventing Translation Service Department from beginning a complete revision of the work.”[89] This translation by Hu Wei-I would help make the Book of Mormon available to the Chinese people until an updated translation would come years later. The translation of the Book of Mormon into Chinese marked an important milestone for the Church in Taiwan.

Painting of President McKay in traditional Chinese robe in 1966. Elder Hinckley accepted the painting while in Taiwan and presented to President McKay in Salt Lake City. Courtesy of Phil and Brenda Frandsen.

Painting of President McKay in traditional Chinese robe in 1966. Elder Hinckley accepted the painting while in Taiwan and presented to President McKay in Salt Lake City. Courtesy of Phil and Brenda Frandsen.

Conclusion

By 1959, Elder Mark E. Petersen visited members and missionaries in the various branches in Taiwan, and he dedicated the island for the preaching of the gospel. The dedication and service of early Chinese pioneers included the call of the first proselyting missionary elder during this time. During the 1960s, Elder Gordon B. Hinckley would begin his long and personal ministry among the Chinese Saints in Taiwan and others throughout Asia. Due to the efforts of Elder Hinckley and the Saints in Taiwan, the Church began to be better organized in the early 1960s. In 1964, the North, Central, and South Districts were organized in Taiwan with the respective district presidents: Liang Jun-sheng (梁潤生), Ung Min-Tsan (翁明燦), and He Shuen-Ding (賀順定). Elder Hinckley would also call and set apart Hu We-I, who, along with others, would help to translate the first Chinese Book of Mormon in 1965. The publication of this first Chinese LDS scripture would be a significant milestone that would help to further missionary work among the Chinese people in Taiwan.

Notes

[1] “Country Information: Taiwan,” 1 February 2010, LDS Church News http://

[2] Heaton, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, Southern Far East Mission, 1955–59, 652–54.

[3] Heaton, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 652–54.

[4] Heaton, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 652–54.

[5] Heaton, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 652–54.

[6] Michael Walker, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, Southern Far East Mission, 1955–59, 654–55.

[7] Walker, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 654–55.

[8] Thomas Nielson, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, Southern Far East Mission, 1955–59, 658–59.

[9] Vernon Poulter, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, Southern Far East Mission, 1955–59, 655–56.

[10] Mei Hsiang Moyer, “Me, a Pioneer?,” Ensign, August 2002, 11.

[11] Heaton, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 663–64.

[12] Walker, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 654–55.

[13] Walker, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 657–58.

[14] Nielson, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 658–59.

[15] Nielson, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 658–59.

[16] Walker, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 654–55.

[17] Nielson, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 658–59.

[18] Nielson, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 658–59.

[19] Walker, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 654–55.

[20] Walker, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 654–55.

[21] Luana C. Heaton, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, Southern Far East Mission, 1955–59, 637.

[22] Franklin Dennis Farnsworth, Southern Far East Mission letters, 1960–1963, Church History Library (MS 18716).

[23] Franklin Dennis Farnsworth, Southern Far East Mission letters, 1960–1963, Church History Library (MS 18716).

[24] Franklin Dennis Farnsworth, Southern Far East Mission letters, 1960–1963, Church History Library (MS 18716).

[25] Moyer, “Me, a Pioneer?,” 11.

[26] Moyer, “Me, a Pioneer?,” 11.

[27] Moyer, “Me, a Pioneer?,” 11.

[28] Moyer, “Me, a Pioneer?,” 11.

[29] Moyer, “Me, a Pioneer?,” 11.

[30] Chen Yung-Chu (Larry), interview by Chou Po Nien (Felipe), 7 November 2015, Murray, UT.

[31] Chen Yung-Chu (Larry), interview by Chou.

[32] “Taiwan—East Side West Side Story,” Voice of the Saints, February 1966, 34–36, Church History Library.

[33] “Taiwan—East Side West Side Story,” 34–36.

[34] Chen Yung-Chu (Larry), interview by Chou.

[35] Chen Yung-Chu (Larry), interview by Chou.

[36] Chen Yung-Chu (Larry), interview; Chen W-Hsiung (Ed), phone interview by Chou Po Nien (Felipe), 25 March 2016, Salt Lake City.

[37] Gordon B. Hinckley, Teachings of Gordon B. Hinckley (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1997), 422–23.

[38] Robert Suman, interview by Chou Po Nien (Felipe), 27 February 2016, Provo, UT.

[39] Liang Shih-An, interview by Chou Po Nien (Felipe), 20 November 2015, Taipei, Taiwan.

[40] A version of this section appears in print in Chou Po Nien (Felipe), Petra Chou, and Tyler Thorsted, “The Chinese Scriptures,” Mormon Historical Studies, 17, nos. 1–2 (Spring/

[41] Joseph Fielding Smith, Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 176.

[42] Diane L. Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese” (unpublished paper, Brigham Young University, 1977), 1.

[43] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon–Chinese Relations,” 92–97.

[44] Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese,” 2–5.

[45] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon–Chinese Relations,” 92–97.

[46] Larry Browning, “On Translation of the Book of Mormon,” lecture notes given to Dr. Honey’s Chinese class at BYU, 13 March 2007, Provo, UT, 1–6.

[47] Robert J. Morris, “Some Problems of Translating Mormon Thought into Chinese,” BYU Studies 10, no. 2 (Winter 1970): 173–85.

[48] Vernon Poulter to Sandy Lee, 2003, copy in possession of authors. Also published by Mark Albright, “Missionary Moment: The Remarkable Story of the Translation of the Chinese Book of Mormon,” Meridian Magazine, 4 February 2011, http://

[49] Vernon Poulter to Sandy Lee, 2003.

[50] Vernon Poulter to Sandy Lee, 2003.

[51] Vernon Poulter to Sandy Lee, 2003.

[52] Vernon Poulter to Sandy Lee, 2003.

[53] Vernon Poulter to Sandy Lee, 2003.

[54] Hu Wei-I, interview by Melvin P. Thatcher, 21 October 2001, Taipei, Taiwan, Church History Library (OH 2952).

[55] James L. Goodfellow, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, Southern Far East Mission, 1955–59, 467.

[56] Mark Albright, “Missionary Moment: Chinese Book of Mormon Translation: The Rest of the Story,” Meridian Magazine, 6 February 2011, http://

[57] Van Therald, “On Either Side,” Voice of the Saints (Hong Kong: Wing Tai Printing Company, 1966), 35–38.

[58] Hu Wei-I, interview by Thatcher.

[59] Emily Chien, “Ties to Taiwan,” Church News, 6 August 2005, 7.

[60] Vernon Poulter to Sandy Lee, 2003.

[61] Therald, “On Either Side,” 35–38.

[62] Henry A. Smith, “That They May Know . . . ,” Church News, 29 January 1966, 3.

[63] Browning, “On Translation of the Book of Mormon,” 1–6.

[64] Christine Rappleye, “Chinese Translation of the Book of Mormon,” Deseret News, 25 February 2012.

[65] “Country Information: Taiwan,” in 2010 Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2010), 585.

[66] Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese,” 6.

[67] Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese,” 6.

[68] Therald, “On Either Side,” 35–38.

[69] Browning, “On Translation of the Book of Mormon,” 1–6.

[70] Southern Far East Mission (SFEM), quarterly reports, September 1963, Church History Library.

[71] Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese,” 8–9.

[72] Browning, “On Translation of the Book of Mormon,” 1–6.

[73] Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese,” 5–8.

[74] Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese,” 8.

[75] Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese,” 9–11.

[76] Browning, “On Translation of the Book of Mormon,” 1–6.

[77] Therald, “On Either Side,” 35–38.

[78] “Country Information: Taiwan,” in 2010 Church Almanac, 585; Therald, “On Either Side,” 35–38.

[79] Therald, “On Either Side,” 35–38.

[80] Southern Far East Mission Quarterly Historical Report, 31 December 1965, SFEM, Church History Library.

[81] Different sources indicated a different number of copies printed. In the first edition of the Chinese Book of Mormon, it stated that three thousand copies were printed. However, a Church News article dated 29 January 1966, page 3, stated that there were five thousand copies printed; Smith, “That They May Know . . . ,” 3.

[82] Gordon B. Hinckley, inscription inside Chinese Book of Mormon delivered to David O. McKay, 9 January 1966, Church History Library.

[83] Chou Po Nien (Felipe), personal history and journal entries, 2000–2002.

[84] Rappleye, “Chinese Translation of the Book of Mormon,” 25.

[85] Smith, “That They May Know . . . ,” 3.

[86] Smith, “That They May Know . . . ,” 3.

[87] Tyler Thorsted, interview by Chou Po Nien (Felipe), 2 April 2015, Salt Lake City; 1966 Chinese Book of Mormon (June and August editions).

[88] Thorsted, interview by Chou; 1967 Chinese Book of Mormon (January and October editions); 1969 Chinese Book of Mormon (May and October editions).

[89] 1970 Chinese Book of Mormon (May edition); “Country Information: Taiwan,” in 2010 Church Almanac.