Prelude to 1956

Entering and Dedicating the Chinese Realm (1852–1955)

Chou Po Nien (Felipe) (周伯彥) and Chou Sin Mei Wah (Petra) (周冼美華), “Prelude to 1956: Entering and Dedicating the Chinese Realm (1852-1955),” in Voice of the Saints in Taiwan, ed. Po Nien (Felipe) Chou (周伯彥) and Petra Mei Wah Sin Chou (周冼美華) (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 1-24.

Historical Background

When Portuguese sailors first passed the island of Taiwan in 1544, they named it Ilha Formosa, meaning “Beautiful Island.” Taiwan is about one-sixth the size of the state of Utah, but the population would grow to over twenty-three million people by 2016. The 58,756 members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) in 2016 accounted for only 0.2 percent of the population in Taiwan.[1] This book shares the history of the LDS Church in Taiwan.

Taiwan is an island located off the east coast of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). It was originally inhabited by aboriginals before the arrival of small Dutch settlers, bringing some of the first Christian missionaries to Taiwan in 1624. In the seventeenth century, Christianity was introduced by Catholic and Protestant missionaries. Loyalists of the Ming Dynasty defeated the Dutch and established control of the island in 1662 until they were overpowered by the Qing Dynasty. In 1683, the Han Chinese of the Qing Dynasty conquered and brought Buddhism and Taoism to the island in 1683, driving out Christian missionaries until the nineteenth century.[2]

In the years following the first treaty between China and a Western nation in 1842, foreign powers gradually dismembered the once-glorious Chinese empire, resulting in the steady decline of the Qing Dynasty. Christian missionaries entered portions of China in ensuing years, despite efforts to drive all foreigners from the country.[3] As part of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895, Japan gained control of Taiwan. The Japanese allowed missionary work in the Taiwan, but limited it to non-Presbyterian Protestant religions at first. However, by the 1920s this rule gradually relaxed, allowing other Protestant denominations in the island.[4]

An Ensign to All Nations

About a year after The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was organized, an earthquake hit Beijing, China, in June 1831. Although this incident had no relation to the new faith organized by the Prophet Joseph Smith, it was made relevant by newspapers in the eastern United States. An anti-Mormon article blamed the earthquake on “Mormonism in China,” reporting that a young Mormon girl predicted this disaster six weeks earlier, even though the Church had not yet turned its attention to the Orient. The purpose of this false report was to mock the Church and prevent people from investigating it.[5]

After Brigham Young became the President of the Church following the martyrdom of the Prophet Joseph Smith, he led the Saints to the Salt Lake Valley in 1847. By 1849, Church leaders expressed a desire to build an “ensign to the nations.”[6] Although the international expansion of the Church would begin in Europe and the Pacific, Brigham Young raised the issue of foreign missions, including China, with Willard Richards in May 1849. On 22 September 1851, the sixth general epistle of the Presidency of the Church called upon the Saints to fulfill the Church’s international destiny by taking the light of the gospel to “the four quarters of the earth” and to expedite the preparation “for the introduction of the Gospel into China, Japan.”[7]

Early Mission to the Chinese

On 28–29 August 1852, before the usual October conference, a special missionary-themed general conference of the Church was called by President Brigham Young for the purpose of sending out 108 missionaries to various parts of the world. Except for the twenty-two assigned to the United States, this was the largest number of missionaries to be sent abroad in a single year to this point. As part of this missionary-centered conference, the Church officially announced the doctrine of plural marriage (discontinued by the Church in 1890; see Official Declaration 1). Heber C. Kimball said to those assembled, “I say to those who are elected to go on Missions, go, if you never return; and commit what you have into the hands of God—your wives, your children, your brethren and your property.” On 16 October, these missionaries were set apart and given priesthood blessings. Among them there were thirty-eight missionaries called to Calcutta, Siam, China, the Sandwich Islands, and Australia.[8]

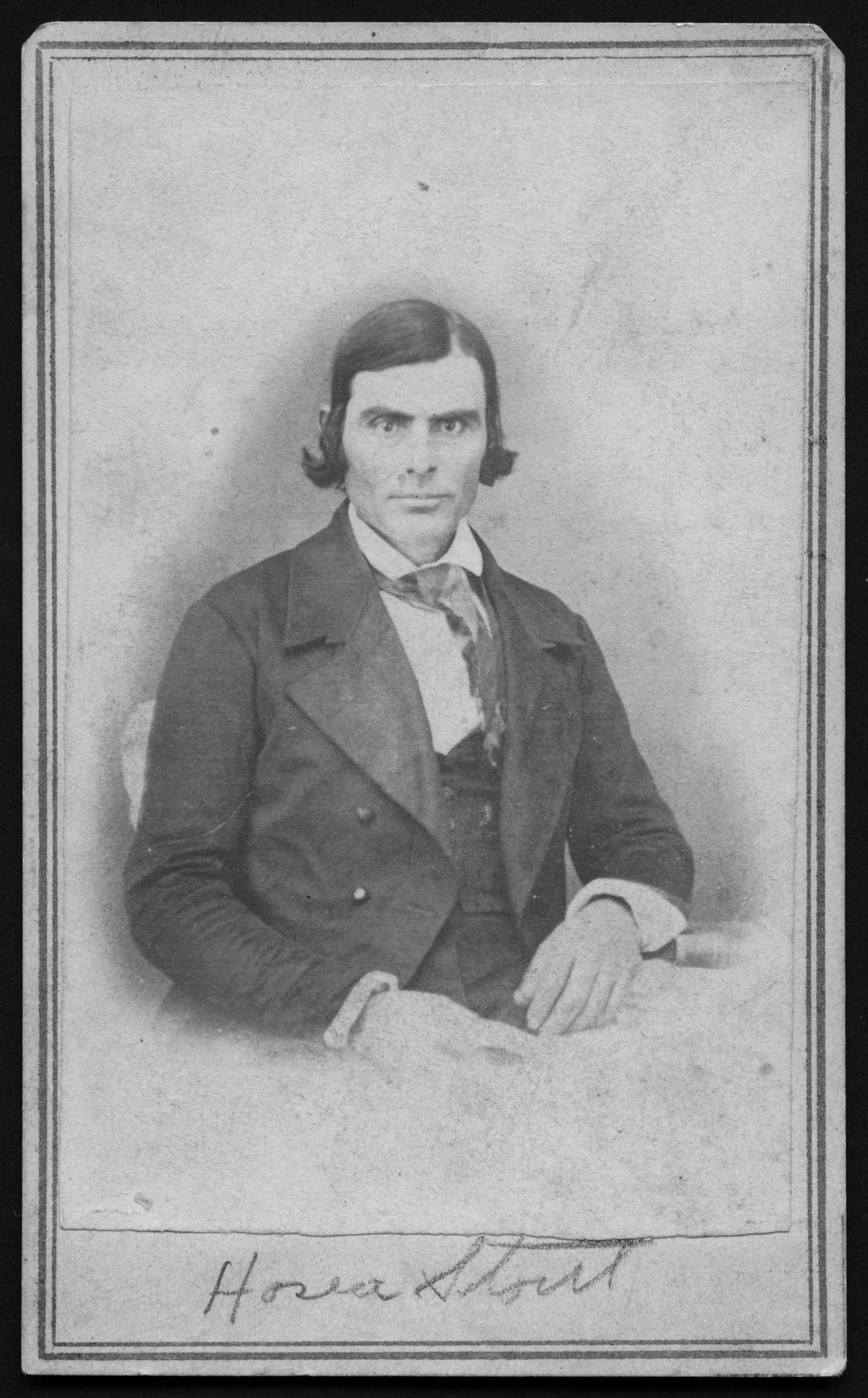

The four missionaries sent to China were Hosea Stout, James Lewis, Walter Thompson, and Chapman Duncan. The sacrifice of early missionaries is illustrated by the experience of Stout, who had to overcome emotional and financial challenges to prepare for his mission overseas. In addition to his wife and youngest son being sick at the time, Stout lacked sufficient funds to provide for the basic needs of his family while he was away. He sold his carpentry tools, books, and other things to raise funds for them.[9] Elder Wilford Woodruff set apart Stout and blessed him as follows:

Let the heart be comforted, for the Lord thy God shall make thee as a flaming sword in his hands, thy tongue shall be loosed, and thy voice shall be as the voice of angels of God. . . .

Thou shalt have power to command the elements and they shall obey thee. Thou shalt have power to perform mighty miracles, and cast out devils, heal the sick, and cause the blind to see, the lame to leap as an hart; for when thou shalt command in the name of the Lord thy commands shall be obeyed. . . . Though the nation and people may be shrouded in darkness, and the prospects before thee gloomy, yet it shall be light. [10]

Hosea Stout lead the first group of missionaries to China in 1852. Courtesy of LDS Church. By Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Hosea Stout lead the first group of missionaries to China in 1852. Courtesy of LDS Church. By Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

On 24 October, this group gathered at Peteetneet Creek near Payson, Utah, to organize the camp, and Hosea Stout was made captain.[11] Although these missionaries knew little about the language, history, tradition, culture, or customs of the Chinese people, they moved forward with faith. As they began their journey, they were unaware of the political instability in China following the end of the Opium War in 1842 that brought rebellions and revolutions in a number of provinces in China. Among the largest of these uprisings were the Taiping Rebellion from 1850 to 1864 and the Nian Rebellion from 1851 to 1868. The former would nearly overthrow the Qing Dynasty.[12]

The group of missionaries arrived in California on 3 December 1852. Walter Thompson returned to Salt Lake due to illness. After raising funds and receiving their passports on 22 January 1853, they proceeded to secure passage to their various destinations. Although others secured passage by late January, the three missionaries bound to China did not sail from San Francisco until 9 March. After forty-seven days at sea, the ship Bark Hoorn arrived in Hong Kong on 28 April 1853. The missionaries found the atmosphere very exciting and initially found temporary quarters with a Mr. Emeny, who provided much information about the city. Rent was rather expensive, so on 5 May, they moved to their own apartment at “Canton Bazaar” after the landlord by the name of Mr. Dudell offered the missionaries free rent for three months.[13]

On 6 May, they taught a group of British soldiers. On 11 May, they taught the first two Chinese people, one having lived in England for eight years. Then they put an announcement in the China Mail, a local paper, that they would hold meetings on the “green,” or the parade ground. As a result, they attracted about one hundred citizens and as many soldiers on 18 May. Meetings were also held on 19–20 May, with about thirty citizens and two hundred soldiers. Local newspapers began to print articles that the Mormons were polygamists, and the missionaries tried to meet with newspaper editors. On 31 May, the missionaries held their last meeting on the parade ground.[14]

Although the missionaries held meetings on the parade ground, they found that the people had little interest. The heat, humidity, and the lack of interest led Stout to say on 7 June 1853, “We have preached publicly and privately as long as anyone would hear and often tried when no one would hear.” Challenges with the language and culture, as well as the Taiping Rebellion from 1850 to 1864, also hindered missionary work. In addition, there was only a small contingency of European soldiers in Hong Kong. On 22 June, the three elders sailed on the Rose of Sharron, arriving in San Francisco on 22 August 1853.[15]

Upon his return, Stout found that his wife and baby had passed away during his mission, and that his mother-in-law was caring for his other children.[16] Although these missionaries did not find success in Hong Kong, the Lord recognized their obedience, sacrifice, and devotion to the cause of Zion. In 1996, during the dedicatory prayer of the Hong Kong Temple, President Gordon B. Hinckley prayed, “We are grateful for the faith of those who, nearly a century and a half ago, first came to Hong Kong as missionaries of Thy Church. Their labors were difficult and largely without reward. But their coming was an evidence of the outreach of our people to all nations of the earth in harmony with the commandments of Thy Beloved Son that the gospel should be preached to every nation, kindred, tongue and people.”[17] This gratitude for the first missionaries to the Chinese people is shared by the Saints in Taiwan who are acquainted with their sacrifice.

Taiwan remained under Japanese rule between 1895 and 1945. Furthermore, the Empire of Japan also used Taiwan as a base for their colonial expansion into Southeast Asia and the Pacific until the end of World War II. Alma Taylor, an LDS missionary who had been serving in Japan, toured China in 1910 to determine whether missionaries should be sent to this nation.[18] Taylor found the circumstances in China to be difficult and reported to the First Presidency, “It appears to us that the latter day saints will not be neglecting their duty to the world nor allowing any golden opportunity to slip by if they postpone the opening of a mission in China until the present chaotic transitory state changes sufficiently to assure the world that China really intends and wants to give her foreign friends protection and a fair chance.”[19]

Elder McKay’s Dedication of the Chinese Realm in 1921

In 1912, the Republic of China (ROC) was established in mainland China, bringing a degree of stability in the region that allowed Elder McKay to visit in 1921 to dedicate the Chinese realm for the preaching of the gospel. In 1920, the First Presidency felt strongly about sending a General Authority on a one-year fact-finding mission to evaluate world conditions after World War I. President Heber J. Grant, then President of the Church, assigned this responsibility to Elder David O. McKay, then a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Prior to leaving on his world tour, Elder McKay received instructions from President Grant to dedicate China for the preaching of the gospel if he “felt so impressed.” Hugh J. Cannon, then president of the Salt Lake Liberty Stake, was Elder McKay’s traveling companion on his world tour.[20]

Elder David O. McKay (right) on world tour with Hugh J. Cannon. They entered China in January 1921. Courtesy of LDS Church. Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Elder David O. McKay (right) on world tour with Hugh J. Cannon. They entered China in January 1921. Courtesy of LDS Church. Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

After visiting Japan, Elder McKay and President Cannon arrived in Beijing by train on the evening of 8 January 1921. At their hotel, just south of the Forbidden City, they prayed that night and the next morning to know if they should move forward with the dedication. Elder McKay felt that the time was “near at hand when these teeming millions should at least be given a glimpse of the glorious Light now shining among the children of men,” so they proceeded to the Forbidden City after breakfast on 9 January 1921.[21]

While visiting the Forbidden City in Beijing, they searched for a suitable location for the dedication and found a secluded grove of cypress trees in an area known today as the Zhongshan Park. Cannon recorded, “Directed, as we believe, by a Higher Power, we came to a grove of cypress trees, partially surrounded by a moat [Tongzihe or Tube River], and walked to its extreme northwest corner, then retraced our steps until reaching a tree with divided trunk which had attracted our attention when we first saw it.”[22] When he saw the impressive and solemn scene, Elder McKay said, “This is the spot.”[23] Cannon was asked by Elder McKay to consecrate the location for “prayer and supplication.” Then they both knelt down, and Elder McKay offered the dedicatory prayer using his apostolic keys to “unlock the door of the Gospel.” Elder McKay dedicated and set apart the Chinese realm for the preaching of the gospel.[24] In his dedicatory prayer, Elder McKay prayed:

Elder David O. Mckay at the Forbidden City in Beijing, China, to dedicate the Chinese realm for the preaching of the gospel on 9 January 1921. Courtesy of Spencer J. Palmer, The Church Encounters Asia (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1970), 34.

Elder David O. Mckay at the Forbidden City in Beijing, China, to dedicate the Chinese realm for the preaching of the gospel on 9 January 1921. Courtesy of Spencer J. Palmer, The Church Encounters Asia (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1970), 34.

Our Heavenly Father: In deep humility and gratitude, we thy servants approach thee in prayer and supplication on this most solemn and momentous occasion. . . .

In this land there are millions who know not thee nor thy work . . . who have never been given the opportunity even of hearing the true message of their Redeemer. Countless millions have died in ignorance of thy plan of life and salvation. We feel deeply impressed with the realization that the time has come when the light of the glorious Gospel should begin to shine through. . . .

To this end, therefore, by the authority of the Holy Apostleship, I dedicate and consecrate and set apart the Chinese Realm for the preaching of the Gospel of Jesus Christ as restored in this dispensation through the Prophet Joseph Smith. By this act, shall the key be turned that unlocks the door through which thy chosen servants shall enter with Glad Tidings of Great Joy to this benighted and senile nation. . . .

May the Elders and Sisters whom thou shalt call to this land as missionaries have keen insight into the mental and spiritual state of the Chinese mind. Give them special power and ability to approach this people in such a manner as will make the proper appeal to them. We beseech thee, O God, to reveal to thy servants the best methods to adopt and the best plans to follow in establishing thy work among this ancient, tradition-steeped people . . .

Hear us, O kind and Heavenly Father, we implore thee, and open the door for the preaching of thy Gospel from one end of this realm to the other, and may thy servants who declare this message be especially blest and directed by thee.[25]

Elder McKay recorded that he “supplicated our Father in heaven and by the authority of the Holy Melchizedek Priesthood, and in the name of the Only Begotten of the Father, turned the key that unlocked the door for the entrance into this benighted and famine-stricken land of the authorized servants of God to preach the true and restored gospel of Jesus Christ.” After less than two weeks in China, they continued to tour the non-American missions of the Church, forever changed by the Orient and its people.[26]

They returned to Utah in December 1921, after traveling 61,646 miles—including 23,777 miles by land and 37,869 by water. At his next mission general conference address, Elder McKay said, “I want to testify to you that God was with us when we stood beneath that tree in old China and turned the key for the preaching of the gospel in the Chinese realm.”[27] Although Elder McKay had turned the key, he also suggested in his report that it was not yet time for the work to commence in China due to the lack of peace and instability in China at the time.[28]

The Chinese and Southern Far East Missions

While serving in the First Presidency, President McKay continued to be involved with the early missionary efforts to the Chinese people.[29] Elder Matthew Cowley of the Quorum of the Twelve was sent to access conditions for reopening the Chinese Mission. With Hilton A. Robertson and Henry Wong Aki, Elder Cowley went to the Victoria Peak and dedicated Hong Kong for the preaching of the gospel on 14 July 1949. Elder Cowley desired that “Oriental people will accept the Gospel readily and in due time, there will be a temple built here to the Most High.”[30]

Robertson became the first president of the Chinese Mission, with Aki as his first counselor. The first two young missionaries to arrive on 25 February 1950 were Elders H. Grant Heaton and William K. Paalani. During 1950, there were five missionary elders assigned to the Chinese Mission, baptizing seventeen people including one American serviceman. However, within a couple of years the missionaries were withdrawn due to the Korean Conflict and the tensions from the Chinese revolution.[31] The Chinese Mission in Hong Kong was closed in January 1951 and missionaries were transferred to Hawaii and then to San Francisco by April of that same year. By February 1953, the Chinese Mission in San Francisco closed.[32]

Elder Matthew Cowley with China missionaries, February 1951. Back row from left to right: Elders Yuen, Parry, Heaton, Smith, Pa'alanai. Front row: Sister and Brother Henry Wong Aki, Elder Cowley, President and Sister Hilton A. Robertson. Courtesy of Heaton Family.

Elder Matthew Cowley with China missionaries, February 1951. Back row from left to right: Elders Yuen, Parry, Heaton, Smith, Pa'alanai. Front row: Sister and Brother Henry Wong Aki, Elder Cowley, President and Sister Hilton A. Robertson. Courtesy of Heaton Family.

Meanwhile, the Chinese civil war ensued after World War II. By 1949, Mao Zedong’s Communist army established the “People’s Republic of China” (PRC) in China after defeating Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang (KMT) government. The “Republic of China” (ROC) led by Chiang and his KMT government relocated to Taiwan, with Taipei as its temporary “wartime capital.” The United States sent its Seventh Fleet to the Taiwan Straits to minimize hostilities between the KMT and the Communist government in mainland China in the 1950s as the Chinese civil war continued without truce.[33]

Approximately two million Kuomintang leaders, soldiers, supporters, and refugees fled to Taiwan.[34] Refugees from mainland China brought a combination of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism to Taiwan.[35] Chinese Catholics and other Christians were also among the refugees.[36] The government imposed martial law and regulated free speech and religious freedom in Taiwan but also welcomed Western Christian missionaries following the US military and economic aid.[37] This facilitated the entry of American LDS missionaries.[38] The Presbyterian Church in Taiwan, which had arrived in the nineteenth century, was very vocal and critical of the government’s restriction of religious freedom and called for local autonomy.[39] The Presbyterian Church’s confrontation with the government resulted in the expulsion of some of their church leaders, a situation avoided by the LDS Church as a result of their policy of political neutrality.[40]

In 1954, President David O. McKay sent Elder Harold B. Lee, then a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, to tour and assess conditions in Asia. During their two-month trip, he met with President Hilton A. Robertson and visited hundreds of servicemen and members of the Church throughout Asia. While in Hong Kong, they visited Victoria Peak and later held a small sacrament meeting with a few Chinese converts in a hotel room. When Elder Lee’s bus was pulling out to take him to the airport, Koot Siu-Yuen (Nora), the first Chinese convert baptized on 31 December 1950, stretched her hand through the window and pleaded in tears, “Apostle Lee, tell President McKay to please send the Church back to China.” Elder Lee wept and replied, “My dear sweet girl, as long as we have a faithful devoted band like you who without a shepherd, are remaining true, the Church is in China.”[41]

Smiths and Heatons with the first eight missionaries of the Southern Far East Mission on 23 August 1955. Back row from left to right: Elders Bradshaw, Wheat, Madsen, Degn, Birch, Ollis, Fong, Jackson. Front row: President Joseph Fielding Smith, Sister Smith, Sister Heaton and Grant Jr., President H. Grant Heaton. Courtesy of Heaton family.

Smiths and Heatons with the first eight missionaries of the Southern Far East Mission on 23 August 1955. Back row from left to right: Elders Bradshaw, Wheat, Madsen, Degn, Birch, Ollis, Fong, Jackson. Front row: President Joseph Fielding Smith, Sister Smith, Sister Heaton and Grant Jr., President H. Grant Heaton. Courtesy of Heaton family.

In 1955, conditions improved, and President McKay, then the President of the Church, sent Joseph Fielding Smith, then President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, to visit East Asia. He was accompanied by his wife, the Heatons, and a group of missionaries. President Smith’s group traveled to Japan and visited Japan Mission president Robertson, LDS servicemen, missionaries, and members in Japan. On 16 August 1955, everyone sustained the proposal to divide the Far East Mission into the Northern Far East and the Southern Far East missions. The former included Japan and Korea, and the latter included Guam, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Taiwan, mainland China (not open to LDS proselyting), and other nations in Southeast Asia. H. Grant Heaton, who was a former missionary in Hong Kong in 1951, was sustained as the mission president for the Southern Far East Mission.[42] Elder Gordon B. Hinckley, then a member of the Quorum of the Twelve, said that Heaton’s “contribution can never be adequately measured. He spoke the languages of the people; he worked with them as one who loved them. . . . Surely when any history is written concerning the teaching of the restored gospel in Asia, the name of Grant Heaton must be mentioned and appreciated.”[43] Heaton, then only twenty-six years old, took his wife, Luana, and their six-month-old baby. When Heaton was called and set apart back in Salt Lake, President McKay explained the previous attempts made to preach the gospel among the Chinese and promised, “This time, we will not fail!”[44]

Southern Far East Mission President Harold Grant Heaton, wife Marilyn, and children in 1957. Courtesy of Heaton Family.

Southern Far East Mission President Harold Grant Heaton, wife Marilyn, and children in 1957. Courtesy of Heaton Family.

Journey to the Far East and Time in Hong Kong

The following experiences were related by two young missionaries who would later be among the first four elders to be sent to Taiwan. Weldon Kitchen thought a stateside two-year mission, like the Southern States Mission, would be plenty long when he submitted his mission papers. So when he opened his mission call on 13 July 1955, he was completely stunned to learn that he was called to serve for three years in the Southern Far East Mission. Part of the letter from the Church office read, “You will pick up your visa in Tokyo, Japan, enroute to Hong Kong, China.” His father responded, “Where is Hong Kong?”[45] Melvin C. Fish was also called to the Southern Far East Mission and shared the following:

My mission call stated; “You are hereby called to be a missionary of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to labor in the Southern Far East Mission.” It was dated June 21, 1955, and was signed by President David O. McKay. It did not say where the headquarters of the mission was located or anything about the territory that was included in the mission. It was not until a week or two later that I found out actually where I would be going. . . . [We] contacted various leaders whom we thought would know about the Southern Far East Mission. Nobody had ever heard of it. I later found out that no one had heard of it because at that time it only existed on paper.[46]

They eventually found out that this was a new mission to be created and reported to the mission home in Salt Lake City, Utah. In the 1950s, there was no missionary training center, and missionaries reported to and spent one week at the mission home. Elder Kitchen explained the following:

The Mission Home comprised of three large, old homes that had been converted into a bunch of bedrooms. . . .

We attended some very spiritual meetings that first day, listening to some General Authorities expounding on worthiness to enter the temple. We were all humbled by what was said, and we were all on our knees praying throughout the night to prepare us for going to the temple the next day to receive our endowments. And so it was, I made my first entry into the temple on August 25, 1955. . . . Many more trips would be made to the temple before I would begin to understand the significance of the endowment.[47]

Kitchen observed that one week was not much time to prepare for one’s mission. Besides the instructions from Church leaders and attending the temple, they also received instructions about their journey.

One event stands out in my mind that I will always treasure. . . . [We] were given instructions to go to an office outside of the Church Office Building to receive special instructions concerning our boat passage. We went to a gentleman’s office, and he instructed us for over an hour on what was expected of us on our voyage across the Pacific. . . . We were told of things that were acceptable, and things that were not acceptable on our voyage. We were charged with the responsibility of being representatives of the Church and creating an image that would be complimentary to the rest of the world. The person who gave us this advice was no other than Gordon B. Hinckley. At that time he worked for the Church, but wasn’t yet a General Authority.[48]

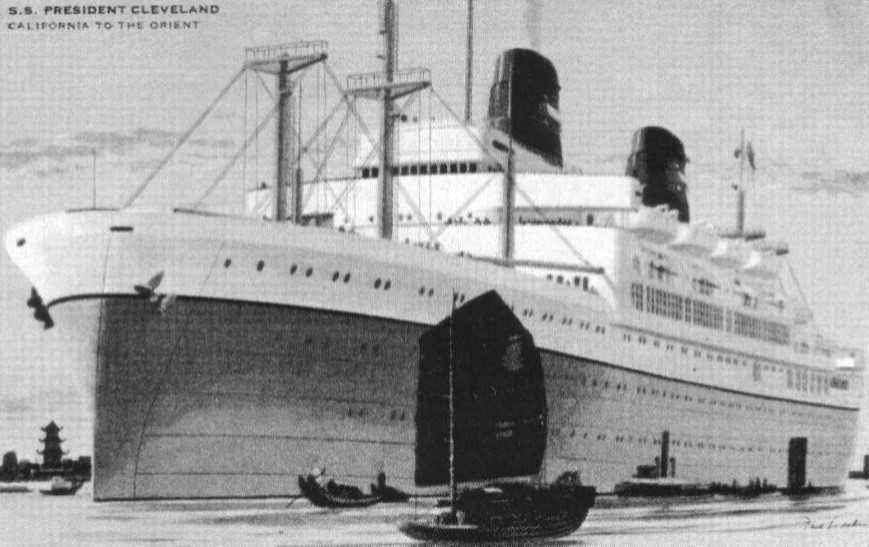

On their last day at the mission home, 31 August 1955, the missionaries were set apart by different General Authorities for their respective missions. Then, the missionaries returned home as they waited for their travel to commence. On 12 September 1955, missionaries traveled by car, bus, and train to reach San Francisco the following day. They rested at the Hotel Shaw and secured their visas. Some family members came to see the missionaries off. Kitchen reported it was great to see his parents before boarding the boat, but he wondered if he would see them again, as his mother and father were sixty-four and sixty-six years old respectively. The six missionaries boarded the SS President Cleveland at noon on 15 September 1955. The voyage took the missionaries to Hawaii, Japan, and the Philippines, arriving in Hong Kong after several weeks at sea.[49] Fish reported meeting missionaries and ministers from other churches on the ship.

SS President Cleveland in 1955. Early Missionaries traveled by ship from the US to the Far East. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchen.

SS President Cleveland in 1955. Early Missionaries traveled by ship from the US to the Far East. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchen.

I became acquainted with a Catholic priest. When he heard that we were going to Hong Kong where we would be teaching the Chinese people and that we would only be there for three years he laughed and said, “There is no way you can be effective at all. I have studied Chinese for six years and I still have trouble carrying on a conversation. How do you expect to learn enough Chinese before you go home to be able to teach anything?”

I responded by saying, “We believe in the gift of tongues.”[50]

H. Grant Heaton, the first mission president of the Southern Far East Mission greeted the missionaries as they disembarked in Hong Kong on 8 October 1955. He was only twenty-six years old at the time, only a few years older than the newly called elders.[51] The Heatons had just arrived in Hong Kong six weeks earlier, after traveling with President Joseph Fielding Smith and his wife and welcoming eight other missionaries to open the Southern Far East Mission.[52] With the arrival of the six new elders, Heaton now had fourteen missionaries. Heaton was a missionary in Hong Kong before the Korean War and finished his mission in San Francisco’s Chinatown because missionaries were moved back to the United States due to the war. After his mission, he served in Korea with a military unit that was involved with Chinese negotiation, further cementing his ability to speak Chinese.[53]

A couple of weeks after the second group of missionaries arrived, Heaton held a meeting with the fourteen elders at the mission home and assigned them to their areas of labor. The four missionaries selected to go to Taiwan were Elders Duane W. Degn, Keith A. Madsen, Melvin C. Fish, and Weldon J. Kitchen. They hired a husband and wife pair to tutor them in Mandarin, the language spoken in Taiwan, rather than the Cantonese spoken in Hong Kong.[54] Although Fish indicated two teachers were helpful, Kitchen noted it was confusing due to their different accents. Later on, the missionaries had language study half of the day and proselyted the other half among English people or Chinese people in Hong Kong who spoke English. Since Hong Kong was a British colony and many spoke English, the missionaries were able to find people to teach the gospel. Kitchen recorded, “The process of proselyting was an invigorating activity after the drudgery of language study.”[55] The missionaries found and baptized some people during this time.

Entire group of missionaries in the Southern Far East Mission in 1955. Back row form left to right: Kenneth Fong, Gary Bradsaw, Jerry Wheat, Garnet Birch, Ronald Ollis, Edward Peterson, Lowery Bishop, Duane Degn, Wayne Bringhurst, and Keith Madson. Front Row: Malan Jackson, Melvin Fish, Launa Heaton, and Grant Jr., President H. Grant Heaton, Weldon Kitchen and Lamont Bee. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchns,

Entire group of missionaries in the Southern Far East Mission in 1955. Back row form left to right: Kenneth Fong, Gary Bradsaw, Jerry Wheat, Garnet Birch, Ronald Ollis, Edward Peterson, Lowery Bishop, Duane Degn, Wayne Bringhurst, and Keith Madson. Front Row: Malan Jackson, Melvin Fish, Launa Heaton, and Grant Jr., President H. Grant Heaton, Weldon Kitchen and Lamont Bee. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchns,

Heaton also felt the missionary plan from the US had to be adapted to the Chinese, so he assigned each elder to prepare specific topics, resulting in seventeen lessons prepared to teach the Chinese people. Obtaining visas to Taiwan proved to be a difficult and long process, resulting in an eight-month wait in Hong Kong.[56] The delay may have been partly due to the continued conflict in the Taiwan Straits during 1955–58, as artillery bombardments were exchanged between the Communist forces in the eastern coast of Mainland China and Chiang Kai-shek’s military units in the small islands off the west coast of Taiwan.[57] Notwithstanding the wait, the missionaries grew to love the Chinese people as expressed by Fish:

One really learns to love the people. It doesn’t matter what culture or living standards the people may have. All people are children of God and I really learned to love the people with whom I worked. . . . I found the Chinese people to be extremely polite and highly cultured. I doubt if there could be anywhere on earth where I could have been treated any better than I was by the Chinese people.[58]

To obtain the necessary visas and secure permission to enter Taiwan, a legal form had to be completed along with support from two sponsors. The only two acquaintances in Taiwan provided the needed sponsorship. The first was a business man named Terry Kwan, who owned the popular “Terry’s” restaurant, and whom Heaton met during his military service. The second was Eva Wang, a member of the National Assembly of the National Government in Taiwan, who knew President Robertson when he was in Hong Kong in the 1950s. (Robertson was at the time serving as the mission president in Japan.) Although neither Kwan nor Wang ever joined the Church, their sponsorship allowed the registration for visa permissions to be granted.[59]

With a small group of American LDS servicemen stationed in the region and the Southern Far East Mission established in 1955, the first four LDS missionaries were sent to Taiwan in 1956.[60] Joseph Fielding Smith explained the reason for taking the gospel to the nations of the Far East. Referring to the parable in Jacob 5, he taught:

The interpretation of this parable . . . is a story of the scattering of Israel and the mixing of the blood of Israel with the wild olive trees, or Gentile peoples, in all parts of the world. Therefore we find in China, Japan, India, and in all other countries that are inhabited by the Gentiles that the blood of Israel was scattered, or “grafted,” among them . . .

So the Lord took branches like the Nephites, like the lost tribes, and like others that the Lord led off that we do not know anything about, to other parts of the earth. He planted them all over his vineyard, which is the world. No doubt he sent some of these branches into Japan, into Korea, into China. . . .

That is the answer to these people who approach me with the question, what’s the use of going out among the Chinese, Japanese, and Korean, and the people of the Far East to preach the gospel to them? The answer: because they are branches of the tree, they are of the house of Israel. . . .

Are we going to preach the gospel in Korea, in Japan, in China? Yes, we are. Why? Because the blood of Israel is there.[61]

Notes

[1] According to LDS Church 2015 year-end report. See “Facts and Statistics,” Mormon Newsroom, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2015, http://

[2] Murray A. Rubinstein, “Taiwanese Protestantism in Time and Space, 1865–1988,” in Taiwan: Economy, Society and History, ed. E. K. Y. Chen, Jack F. Williams, and Joseph Wong (Hong Kong: Centre of Asian Studies, 1991), 251–82.

[3] R. Lanier Britsch, From the East: The History of Latter-day Saints in Asia, 1851–1996 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1998), 227–29.

[4] Rubinstein, “Taiwanese Protestantism in Time and Space, 1865–1988,” 251–82.

[5] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, vol. 1 (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1930), 158.

[6] Isaiah 5:26.

[7] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations, 1849–1993” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1995).

[8] Britsch, From the East, 14–39; Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 15; Spencer J. Palmer, The Church Encounters Asia (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1970), 27.

[9] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 17–18.

[10] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 18.

[11] Britsch, From the East, 14–39.

[12] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 16.

[13] Britsch, From the East, 14–39; Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 17–20.

[14] Britsch, From the East, 14–39.

[15] Britsch, From the East, 14–39.

[16] Britsch, From the East, 14–39.

[17] “May Thy Watch Care Be Over It” (dedicatory prayer of the Hong Kong Temple), Church News, 1 June 1996, 4.

[18] Reid L. Nielson, “Alma O. Taylor’s Fact Finding Mission to China,” BYU Studies 40, no. 1 (2001), 183.

[19] Alma O. Taylor, “Report On Our Visit to China,” 31–32, Church History Library (MS 4209).

[20] Reid L. Neilson, “Turning the Key That Unlocked the Door: Elder David O. McKay’s 1921 Apostolic Dedication of the Chinese Realm,” Mormon Historical Studies 10, no. 2 (Fall 2009), 76–101.

[21] Neilson, “Turning the Key That Unlocked the Door,” 86–92.

[22] Neilson, “Turning the Key That Unlocked the Door,” 86–92.

[23] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 32.

[24] Neilson, “Turning the Key That Unlocked the Door,” 90–92.

[25] Neilson, “Turning the Key That Unlocked the Door,” 90–92.

[26] Neilson, “Turning the Key That Unlocked the Door,” 77–92.

[27] Neilson, “Turning the Key That Unlocked the Door,” 92.

[28] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 33.

[29] Neilson, “Turning the Key That Unlocked the Door,” 93.

[30] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 36.

[31] H. Grant Heaton in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission 1949–53, Southern Far East Mission 1955–59, comp. by H. Grant and Luana C. Heaton (Salt Lake City, H. Grant & Luana C. Heaton: 1999), 521–23.

[32] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 63–67; “Two New Stakes for the Far East,” Ensign, June 1976, 87.

[33] Ian Skoggard, “Taiwan,” Countries and Their Cultures, http://

[34] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 148–50; Britsch, From the East, 251–52.

[35] Chou Po Nien (Felipe), “History of the Church in Taiwan in the 1970s,” in The Worldwide Church: The Global Reach of Mormonism, Brigham Young University 2014 Church History Symposium, ed. Mike Goodman and Mauro Properzi (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2016), 120.

[36] Chen-Tian Kuo, Religion and Democracy in Taiwan (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2008), 53–54.

[37] Yunfeng Lu, Byron Johnson, and Rodney Stark, “Deregulation and the Religious Market in Taiwan: A Research Note,” Sociological Quarterly 49, no. 1 (Winter 2008): 139–53.

[38] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 176–77.

[39] Murray A. Rubinstein, The Protestant Community on Modern Taiwan: Mission, Seminary, and Church (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 1991), 3–5.

[40] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 176–77.

[41] Harold B. Lee, “Report on the Orient,” in Conference Report, October 1954, 125–31.

[42] Neilson, “Turning the Key that Unlocked the Door,” 93; Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 70–71.

[43] Palmer, The Church Encounters Asia, 43.

[44] Heaton, A Documentary History of The Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 29, 625.

[45] Weldon Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen (self-published, 2013), 1–2, Church History Library (MS 27068).

[46] Melvin C. Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish (self-published, 2006), 8, Church History Library (M270.1 F5325f 2006).

[47] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 2.

[48] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 2–3.

[49] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 3–4.

[50] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 12.

[51] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 15.

[52] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 5.

[53] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 15.

[54] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 5–6.

[55] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 6.

[56] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 7.

[57] Heaton, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 107.

[58] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 20–23.

[59] Heaton, A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 106.

[60] “Facts and Statistics: Taiwan,” Mormon Newsroom, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, http://

[61] Joseph Fielding Smith, Answers to Gospel Questions, comp. Joseph Fielding Smith Jr., 5 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957–66), 4:40–41, 204–7.