A Marvelous Work and a Wonder

The Labor of the First Missionaries (1956–59)

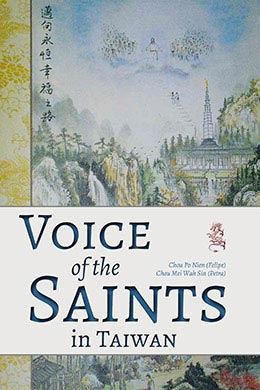

Chou Po Nien (Felipe) (周伯彥) and Chou Sin Mei Wah (Petra) (周冼美華), “A Marvelous Work and a Wonder: The Labor of the First Missionaries (1956-59),” in Voice of the Saints in Taiwan, ed. Po Nien (Felipe) Chou (周伯彥) and Petra Mei Wah Sin Chou (周冼美華) (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 25-60.

In the mid-1950s, “a marvelous work and a wonder” was about to go forth among God’s children in Taiwan. After the end of World War II, a fragile level of stability returned, thus allowing the Church’s missionary efforts to commence once more in the region. Soon after the Southern Far East Mission was established in 1955, mission president H. Grant Heaton assigned missionaries for Taiwan. Following the war, the United States military stationed personnel in various places throughout Asia, including Taiwan. Accordingly, a small contingency of LDS servicemen was stationed in the island, thus facilitating the arrival of the first four LDS missionaries to the island in June 1956.

Despite the tragic death of Elder Keith Madsen and cultural challenges early on, the persistent efforts by these missionaries ensured the permanent establishment of the Church in Taiwan. Missionaries found, baptized, and prepared early Chinese converts to serve as the first local branch presidents and Relief Society presidents on the island. During the first three years, from 1956 to 1959, the seeds of the restored gospel spread to various cities throughout the island.

Missionary Work Begins in Taiwan

First four missionaries to Taiwan in June 1956: Weldon Kitchen, Keith Madsen, Duane W. Degn, and Melvin C. Fish. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchen.

First four missionaries to Taiwan in June 1956: Weldon Kitchen, Keith Madsen, Duane W. Degn, and Melvin C. Fish. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchen.

On 2 June 1956, four Taiwan-bound missionaries boarded the SS Szechuan, a British ship. A local newspaper reported that “Mormon Missionaries Now Labor in Formosa. . . . [They] will be the first missionaries of the Church to labor in that land. The four young men, Elder Duane W. Degn of Ogden, Utah; Elder Keith A. Madsen of Walnut Creek, California; Elder Weldon J. Kitchen of American Fork, Utah; and Elder Melvin C. Fish of Pintura, Utah.” After a two-day voyage, the first LDS missionaries entered the Keelung harbor on 4 June 1956 and were welcomed by Church members and American servicemen and their families stationed in Taipei. This group of LDS servicemen was a great support to the missionaries.[1]

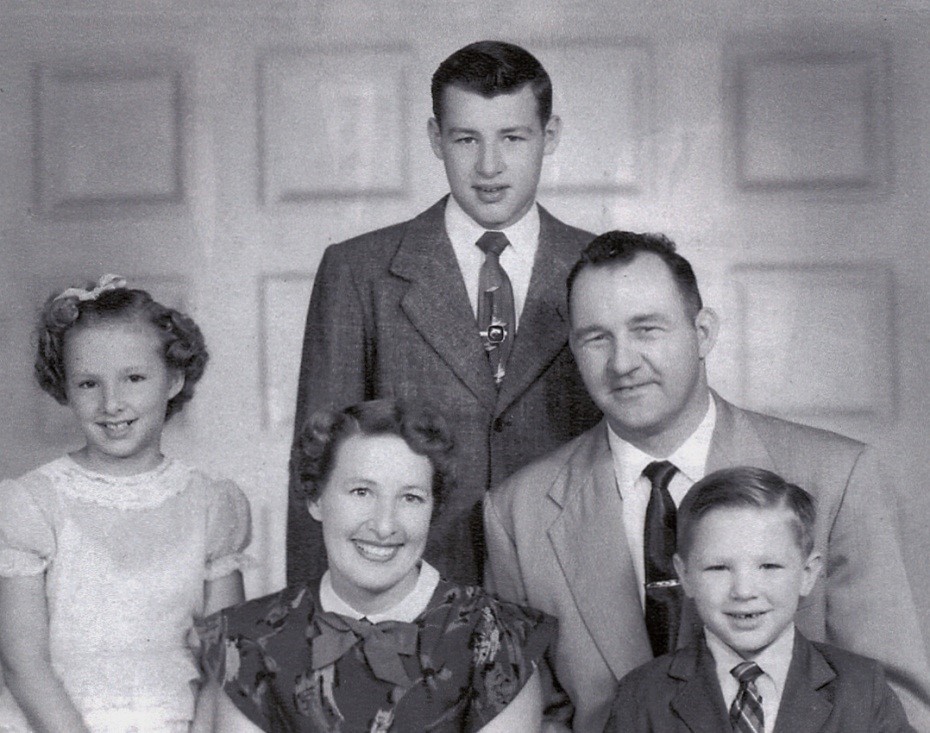

Stanley was the first branch president of Church in Taiwan. The Simiskey family in 1956: Stanley and Julia with their children (Oldest to youngest) Patrick, Rose Mary, and Jared. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchen.

Stanley was the first branch president of Church in Taiwan. The Simiskey family in 1956: Stanley and Julia with their children (Oldest to youngest) Patrick, Rose Mary, and Jared. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchen.

Brother Stanley Simiskey, a captain in the US Air Force, was stationed in Taiwan with his wife, Julia, and their three children. Simiskey was serving as a group leader before he became the branch president, and Elder Degn was named as supervising elder for the missionaries in Taiwan. In his role as the president of the “Taipei American Branch” in Taipei, Simiskey had rented and furnished a two-bedroom apartment for the missionaries and had stocked the pantry with food from the American commissary. The Simiskeys often had the missionaries over for dinner, and the missionaries developed a strong bond with them. Fish said, “This was one of the kindest, most loving and helpful families one could ever know. . . . This family cared for the first four of us as if we were their own children. They would do anything for us.”[2] The missionaries shared their initial experience upon arrival and their surprise at the difference between Hong Kong and Taiwan:

After unpacking our bags and arranging everything in our new house, we had to ride our bikes down to the American Embassy and register. This turned out to be a rude awakening. I have never in my life seen so many bikes. This was a traffic jam to supersede anything I had ever seen. . . .

Although Taipei was a rather large city with a population of about two million people, it was spread out over a wide area. Its tallest buildings downtown were only six or seven stories high. It almost gave us the feeling that we were out in the country, after living in Hong Kong for eight months, with all its skyscrapers.[3]

Another missionary also reported the significant differences between Hong Kong and Taiwan:

Living in Taiwan was quite different from Hong Kong. Hong Kong had so many people in a small place that I always felt confined. . . .

Taiwan had been under the control of the Japanese for about fifty years prior to the Second World War. We arrived there less than ten years after the war ended, so as one would expect, there was still a lot of Japanese influence on the Island. . . .

Most of the tracting areas consisted of small individual houses with a tiny front and back yard. A great many of them were Japanese style, and most of the people followed the Japanese custom of removing their shoes as they entered the home. . . .

Many of the people did not have chairs in their homes. . . . Instead of sitting down they would squat on the floor. I think I gave more missionary discussions in that position than I did while sitting on a chair.[4]

The missionaries encountered different challenges in Taiwan. Once, the missionaries returned home to find their home had been broken into. Not long after, a member of the Church brought the missionaries a dog named “Pandy” to protect their place. On another occasion, one of the missionaries left his bicycle outside during Sunday School, only to find it stolen an hour later.[5] Despite these few challenges, the missionaries came to love the Chinese people in Taiwan as they continued to adjust to the culture and climate in Taiwan. Fish provided the following insights:

The Chinese people were the most polite courteous people I have ever met. When we came to visit they always greeted you warmly and always offered you [tea] . . . We would tell them that we did not drink tea and ask for plain hot water. Most of the water we drank was very hot, even in the summer time. That was good because boiled water was safer to drink . . .

Because there was no air-conditioning most of the people would only wear their underwear around the home and sometimes in public.

We had to wear suit and tie until about March then it would get hot enough that the mission president would declare the change in dress code; then we changed to white short sleeve shirts with an open collar. . . .

In Taiwan people did not have refrigerators. They had iceboxes. These were much like a refrigerator but smaller . . .

I got new soles on my shoes by having a street vendor repair my shoes. He used tread from an automobile tire for soles and they never wore out.

Homes had very little space provided for food storage. Iceboxes were small and there were very few cupboards. So as a result most people shopped daily for food. Most of the food came from open street markets.[6]

Learning the language also continued to be a challenge for the missionaries, and they continued to study and pray for the gift of tongues. It was typical for missionaries to use the aid of a flannel board to help teach the Chinese people. However, one of the challenges of preparing someone to be baptized was the time it took for the missionaries to teach each investigator. Fish recorded, “At that time the approach we used in teaching the gospel required that we teach [seventeen] lessons before the investigator was baptized. We usually taught each investigator once a week at the same time each week.”[7] This process meant it would take several months before an individual could be baptized. Then after baptism there was a second series of lessons, which had twenty more lessons to complete. Although a lengthy process, it was felt that these lessons were essential because most people in Taiwan were Buddhist, Taoist, or followers of Confucius, with no Christian background.[8] There was also opposition from other ministers, as noted by Fish:

A Baptist minister was losing some of his members and decided to do something about it; so he wrote a little pamphlet warning people about the Mormons. He said that the Mormons practiced polygamy and when a woman refused to be involved in a polygamist marriage they were locked up in the towers of the Salt Lake Temple. The only way they could get free was to dive out of a window into the Great Salt Lake and swim to safety. Instead of turning people away from us, it made them curious and they listened to us just to find out what we really believed.[9]

The missionaries also met important government officials in Taiwan. A Miss Wang would invite the missionaries to elaborate dinners and entertainments, where they met these officials. As it turned out, Miss Wang was part of the Chinese secret police assigned to check on the missionaries. Still, this gave the missionaries opportunities to meet with a senator, a general, a bank president, and others. They even taught a man that turned out to be the secretary of state, as well as the wife of the second vice minister of foreign affairs.[10]

First Baptisms Through LDS Servicemen

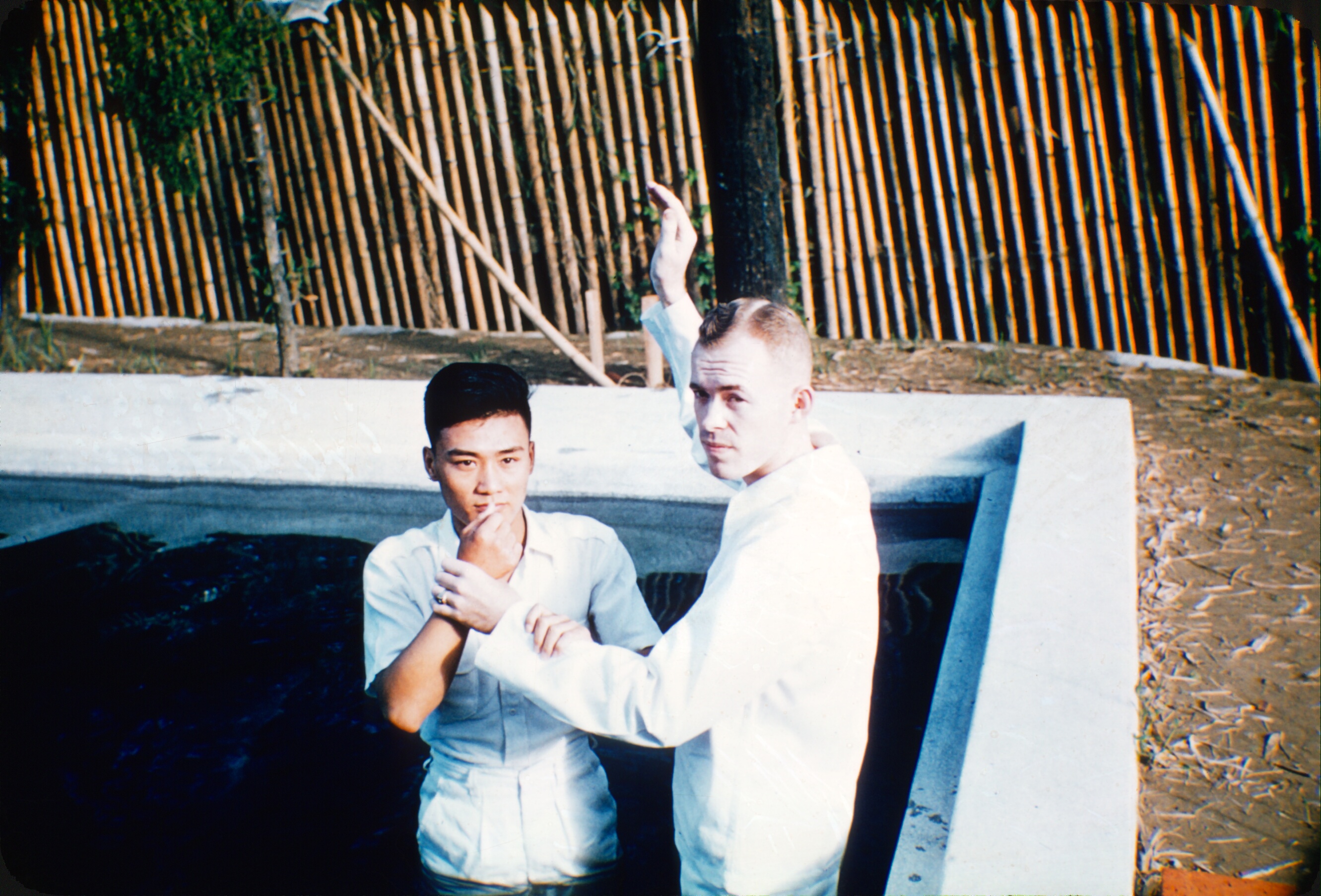

Prior to the arrival of the missionaries in 1956, LDS servicemen in Taiwan began to share the gospel with other military personnel stationed in the island. Robert Hinkley, from Idaho, was among the American servicemen stationed in Taiwan and the first person baptized in Taiwan. As a new convert, Hinkley was excited to share the gospel and befriended Chin Mu Tsung (Richard) (金慕宗), a young Chinese soldier in his department. Chin learned English during a one-year assignment in the United States to study special military strategy. This allowed Chin to read the Book of Mormon in English and gain a testimony of the gospel. Hinkley baptized Chin, who became the first Chinese convert in Taiwan.[11] Chin spoke English well and was a great asset to the missionaries as a translator while they were still developing their Chinese language skills.[12]

First Chinese baptism in Taiwan. Chin Mu Tsung (Richard) was baptised by Robert Hinkley on 26 September 1956. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchen.

First Chinese baptism in Taiwan. Chin Mu Tsung (Richard) was baptised by Robert Hinkley on 26 September 1956. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchen.

On 22 July 1956, the missionaries baptized their first convert, Thomas Kintaro. The Kintaros were actually part of the American military stationed in Taiwan and were not a Chinese family. When the missionaries first met Brother Kintaro, he tried to send them away by telling them his wife would never be interested in becoming a Mormon. After his baptism, this “golden family” became a real asset to the branch.[13] The work among the Chinese was slow, as the missionaries lacked translated materials, including the Book of Mormon, which would not be translated until the next decade. Fish was grateful when the first Chinese tracts arrived from Hong Kong, almost a year after he landed in Hong Kong. He related the following:

We received our first literature printed in Chinese. It was the Joseph Smith Story . . . from the Pearl of Great Price printed in the form of a tract. The more literature we can get in Chinese the faster the work will progress. We only received four copies, but we expect to get more of them soon. It is really gratifying to see how happy some of our contacts were when they saw that we had something for them to read. . . .

October 8, 1956 we finally got our first significant shipment of tracts printed in the Chinese language. These tracts covered six different subjects. . . . The work went much faster when we could teach a lesson; then leave a tract that covered the subject we had just taught. It seemed the people were hungry for the truth.[14]

The number of missionaries doubled on 16 October 1956, when Elders Mark Freebairn, Michael Walker, Gary Williams, and Lewis Wiser arrived in Taiwan.[15] Each new elder received a senior companion, one of the first four missionaries, to assist him with Chinese language study. Housing was arranged at a second location, adding another place for Church services.[16]

Tragedy Threatens Progress

One day, the missionaries met a group of young men at a college in Taipei who invited them to play basketball. The missionaries thought this would be a great opportunity to become better acquainted with these potential investigators.[17] But a tragic accident that day would threaten the progress of the work. Elder Kitchen recorded the following:

We accepted their invitation and scheduled an afternoon game on December 31, 1956. It was a couple of miles ride on our bikes to the college. Elder Madsen was carrying the basketball in one hand as we rode along. . . . I was closest to him, maybe ten yards in front of him. As I happened to look back, I saw his front wheel jackknife, throwing Elder Madsen up over the handle bars, causing him to come head first down on the concrete road. He was knocked totally unconscious. It was apparent this was a very serious accident. We had an ambulance called to take him to the hospital. While waiting for the ambulance to arrive, we administered to him. We felt secure that this administration would make everything all right. We were to learn a lesson that we were not prepared to receive. Elder Madsen remained unconscious for the next two days, and on January 2, 1957, he died. We were shocked beyond belief. We felt like our faith had been totally violated. How could the Lord allow such a thing to happen? Why had our administration not been answered as we had pronounced it? Our faith was shattered.[18]

Fish, called as the new supervising elder of the Taiwan District just a couple of weeks before the accident, said that Madsen hit a rut in the road, flew over his handlebars, and hit his head on the ground, fracturing his skull.[19] When Madsen was first taken to the hospital, everyone was praying for him. President Heaton flew in from Hong Kong when he learned of the accident, and he felt assured at the hospital that Madsen would recover. So when President Heaton was informed that Madsen passed away, he said, “The shock was almost more than I could withstand. I could not weep, nor talk. I was helpless and hopeless. . . . I could not meet the missionaries to comfort them, because I was not comforted. President Simiskey was a Godsend to me during this time.”[20]

Keith A. Madsen, one of the first four missionaries, died on 2 January 1957 in Taiwan from a bicycle accident. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchen.

Keith A. Madsen, one of the first four missionaries, died on 2 January 1957 in Taiwan from a bicycle accident. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchen.

Due to the lack of embalming facilities in Taiwan, arrangements were made through the American Embassy to have the body put into a freezer unit on the US military base temporarily. After a memorial service was held in Taiwan, the body was flown to Hong Kong to accommodate embalming. A funeral service was held in Hong Kong before the body was flown back to California to Madsen’s parents.[21] This tragedy was a tremendous blow to the missionaries and members. Heaton recorded his feelings during this time:

As I finished with the funeral services in Hong Kong, I was still in a spiritual and physical despair. The confidence I had previously experienced turned to anger. I became angry with the Lord for letting this happen. I was angry with myself for not being able to provide better medical treatment for Elder Madsen.

Finally, just prior to shipping the body to the United States, a dream came to me in which I was arguing with the Lord about Elder Madsen. I demanded to know why He would let such a thing happen to a young man serving a mission? The answer I received was a rebuke from the Lord. He seemed to say to me, “Why are you so concerned about Elder Madsen? He has been called to another calling and you do not have any responsibility over him. Why should you be angry if I have called him for My own purposes?” This was not a vision, it was only a dream, but I awakened with a sweet calming spirit which took away all the anger, and the doubt, but not the remorse. I did surely wish the Lord had a better method of calling people. He needed, and I doubted if He needed Elder Madsen as much as we did, at that time. . . .

My memories of Elder Madsen now are only sweet and serene. Both Sister Heaton and I have felt it was a special privilege to have had the opportunity to spend some time with Elder Keith A. Madsen.[22]

The elders in Taiwan were also comforted after receiving a tape of the funeral service in the United States from Madsen’s parents. Kitchen reported that Joseph Fielding Smith spoke at that funeral and “stated that the Lord had a more important mission for him [Elder Madsen] in opening the missionary work for millions of Chinese in the spirit world.”[23]

President Heaton returned to Taiwan the following week to hold a conference with the missionaries in Taiwan. The death of Elder Madsen and the lack of success in Taiwan led Heaton to consider moving all the missionaries back to Hong Kong. According to Kitchen, the missionaries “despaired over the thought of leaving Taiwan” and “pleaded with President Heaton and begged for a little more time before making this decision.” Heaton conceded and told the missionaries he would wait four months to make a final decision. The missionaries redoubled their efforts in Taiwan.[24]

Baptisms in Wu Lai Canyon and Subsequent Growth

On 27 April 1957, before their four months were up, the missionaries baptized their first two Chinese converts at the waters in the Wu Lai Canyon. Elder Degn was overjoyed to baptize Brother Chiu Hung Hsiung (Richard) (邱鴻雄).[25] Elder Kitchen recorded the following about Chiu’s preparation and commitment to follow the Lord and enter the waters of baptism:

We made contact with Chiu Hung Hsiung (Dick) at this time, who became another golden contact. Dick was one of the students that we were going to play basketball with the day of Elder Madsen’s accident. Dick had a pretty good understanding of English, and thus became a big asset to our work. The Book of Mormon had not yet been translated into Chinese, so it became necessary to do some onsite, local translating to convey some of our messages. Dick became a vital link in this regard. Dick Chiu expressed his desire to be baptized. He displayed a strong testimony in the Church—being faithful in every regard. He was willing to sacrifice anything for the Church. He even offered to give up his bike, his only earthly possession, if that was what the Lord wanted. Another time he showed up for Church right in the middle of a typhoon, with wind gales up to about 100 mph. His faith was certainly not waning. April 27, 1957, was the date set for his baptism.[26]

Baptisms at Wu Lai Canyon on 27 April 1957. From left to right: Elder Wiser and Kitchen, Chiu Hung Hsiung (Richard), Elders Freebairn and Degn, Tseng I-Chang (first brother from Taiwan to receive the Melchizadek priesthood), Elder Walker. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchen.

Baptisms at Wu Lai Canyon on 27 April 1957. From left to right: Elder Wiser and Kitchen, Chiu Hung Hsiung (Richard), Elders Freebairn and Degn, Tseng I-Chang (first brother from Taiwan to receive the Melchizadek priesthood), Elder Walker. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchen.

Brother Tseng I-Chang (曾翼璋) was also baptized on that day. Elders Kitchen and Wiser found the Tsengs while tracting. Kitchen said that while teaching Brother and Sister Tseng, “the spirit was strong as I told the Joseph Smith story. They both listened very intently, and at the conclusion of the discussion Brother Tseng bore his testimony that the story was true and the church that was created as its result was indeed God’s true church. From that time forth he referred to the Church as ‘our’ Church.”[27] Brother Tseng was raised in mainland China and educated at a Christian school, so he had a good knowledge of the Bible. He attended all the meetings every Sunday and was so faithful that the missionaries asked him to be the Sunday School teacher. Although Brother Tseng had never joined any church, his wife had joined the Baptist Church. It was odd for the missionaries that Brother Tseng came to the LDS Church while his wife continued to attend her church. Sister Tseng had already been baptized and did not see the need to be baptized again, but she appeared satisfied that her husband was being taught and prepared to join a church.[28]

After Brother Tseng received nearly all the lessons, he was taught the Word of Wisdom. Although it is typical for Chinese people to drink tea on a daily basis, Tseng readily accepted the Word of Wisdom and assured the missionaries that “if the Lord didn’t want us to drink tea that there would be no more tea in his house.” Finally, the time came to teach about the law of tithing.[29] Kitchen wrote about his experience teaching Tseng about commandment:

I saved for last what I considered would be [Tseng’s] biggest challenge—the payment of tithing. He and his family lived in a very tiny, humble house. His monthly wage amounted to $810 NT ($27.00 U.S. equivalent) per month. . . . How could he support his family on only that amount? . . . I took a deep breath and presented the law of tithing, supporting the law by reading the scripture in Malachi 3:8–10. When I finished, Brother Tseng didn’t say a word. I decided in my anxiety about the presentation, my Chinese was so poor that he didn’t understand a word I had said. I decided to go through it again. . . . Brother Tseng still did not say a word. In desperation, I decided to go through the presentation one more time, making VERY SURE I said every word perfect. When I finished, Brother Tseng looked at me and asked me a question. “What is the problem, Elder Kitchen, don’t you believe it?” I was completely humbled. He had understood everything the first time through and had accepted all. The next Sunday, Brother Tseng brought $81 NT ($2.70 U.S. equivalent) to church to pay for his tithing. He accepted the challenge to be baptized the same day that Dick Chiu would be baptized.[30]

A month after he was baptized, Tseng shared his testimony of the law of tithing during a fast and testimony meeting. Shortly after he was baptized, his pay was increased from 810 New Taiwan dollars to 1,290 New Taiwan dollars (or from 27 US dollars to 43 US dollars) per month, then later, he received another raise to 1,410 New Taiwan dollars (or 47 US dollars). Soon after, the missionaries taught and baptized Paul Lin, a student from Hong Kong studying at the University of Taiwan. Kitchen reported that the Church began to grow, and “President Heaton was very impressed with the caliber of people who were being baptized . . . [and] decided that our mission would continue in Taiwan.”[31]

Elder Cutler, who had arrived on 4 February 1957, worked with the other missionaries as missionary work continued to progress in Taipei.[32] Efforts to increase missionary work during the summer of 1957 included various cottage meetings with investigators in Taipei. Fish also tried a new approach by placing an ad in the newspaper that said, “Improve your English and at the same time learn the truth about God. Gospel study classes to be held in connection with an English conversation class.”[33] They began with fifty people, and their English class grew. Fish explained:

The way we operated the class was to select the one who spoke the best English and let him be a translator. We gave the missionary lesson in English and had them translate into Chinese. After the lesson there was a question and answer period. Many of the class members started coming to church. President Heaton was afraid that we would get baptisms where people were baptized for the wrong reason. He required those who wanted to get baptized to have two or three months of individual lessons. When it was all over we really did get quite a few baptisms out of the class.[34]

By September 1957, there was not enough room to accommodate meetings in the two homes of the missionaries. The eight elders moved in together and rented a large mansion. The large garage was converted into a chapel for 150 people, and the front room was used for the Junior Sunday School and Primary for 90 people. This home became the “Taiwan mission home, chapel, and church headquarters.”[35]

Eight missionaries biking in 1957. From left to right Elders Degn, Fish, Freebairn, Kitchen, Wiser, Williams, Cutler, and Walker. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchen.

Eight missionaries biking in 1957. From left to right Elders Degn, Fish, Freebairn, Kitchen, Wiser, Williams, Cutler, and Walker. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchen.

“Anti-American” riots in Taiwan in May 1957 caused some alarm in the mission, and the missionaries were evacuated to the US military compound briefly.[36] The tension occurred after an American military vehicle hit and killed a young Chinese girl. The instability around the world, including Taiwan, prompted the First Presidency to institute a worldwide emergency evacuation plan in 1957. There were two parts to the plan. First, when a cable came from the Church with the code “Prepare Books for Shipment,” preparations were to be made to evacuate missionaries to Japan, the Philippine Islands, or the United States. The second code, “Ship Books Immediately,” meant the missionaries should proceed immediately to obtain travel to one of those designated locations. At the time, there were constant rumors of military actions in Asia and other parts of the world.[37] Fortunately, there was never a need for an emergency evacuation.

Hymnbook and Relief Society in Taiwan

Emma Smith, the wife of the Prophet Joseph Smith, compiled the first LDS hymnbook and was later called to serve as the first Relief Society president for the Church. However, in 1956, the person who compiled the first Chinese LDS hymnbook and served as the first Relief Society president in Taiwan was Elder Fish, rather than a sister.[38]

Fish recognized the importance of hymns in Church worship services, so he decided to compile a Chinese LDS hymnbook. He purchased several Protestant hymnbooks and copied every hymn that was also used by the LDS Church. During his review of the lyrics for doctrinal accuracy, he replaced the Chinese characters for “three in one” to describe the Trinity with three other characters that express the idea for “Godhead.” The latter characters were pasted over the former ones. Unfortunately, the small paper with the correction was peeled off before it was printed. As a result, the five hundred copies of the hymnbook produced for Taiwan and Hong Kong had to be corrected individually. The small hymnbook had thirty-seven pages and included Christmas carols.[39]

Fish reports his call as the first Relief Society president in Taiwan:

I became the first Relief Society President. Because we were starting out from scratch with no Chinese members to rely on, when we finally grew to the point where we were ready to organize a Relief Society, we had no sisters that knew anything about Relief Society. Someone needed to prepare a Sister to take the position of Relief Society President. President Heaton called me to be the Relief Society President, telling me that I would hold that position until I trained someone to take my place. Let me tell you this, it didn’t take long to train my replacement.[40]

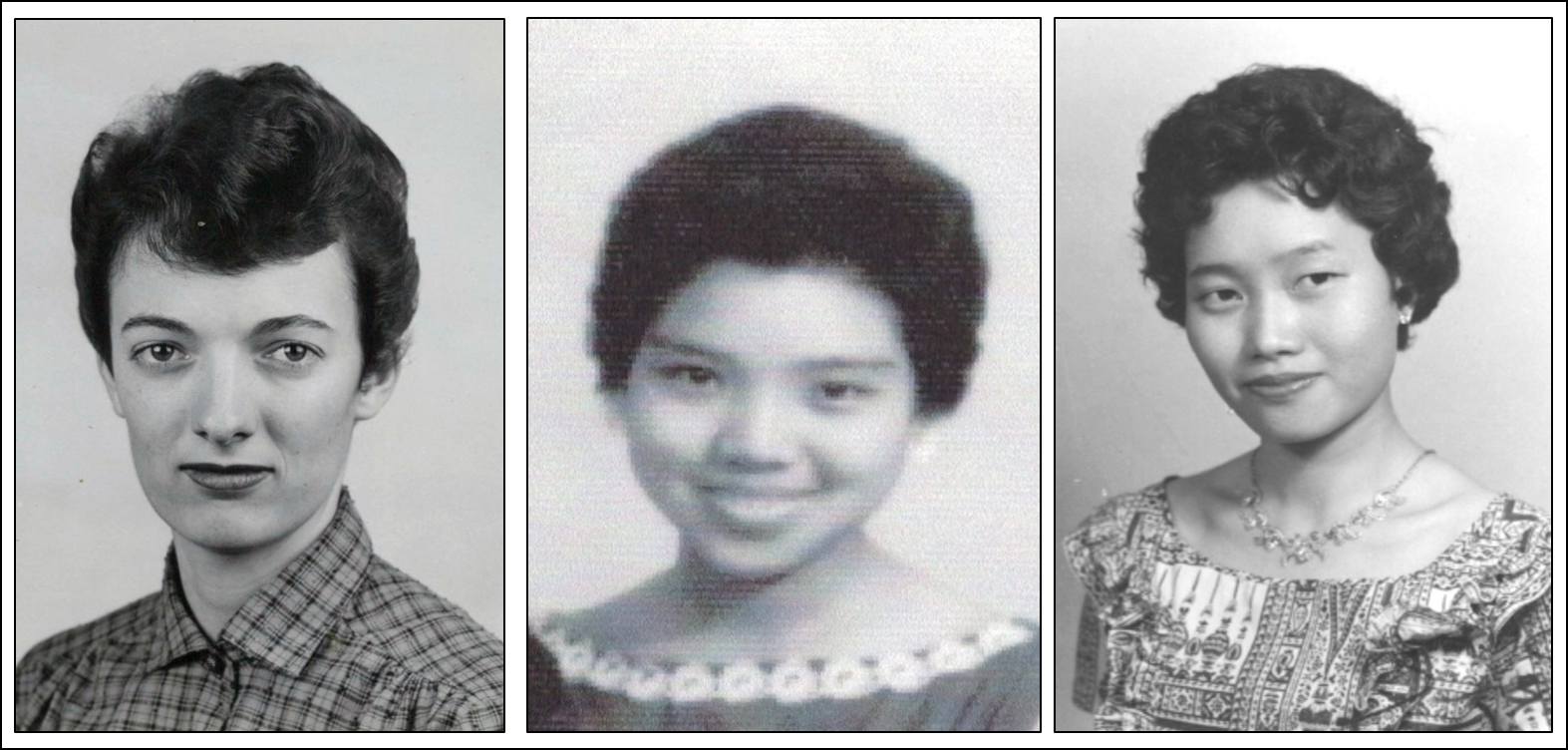

The Relief Society was organized in Hong Kong in April 1957 and held a bazaar in 1958. Afterward, Sister Betty Johnson was sent from Hong Kong to Taiwan to help with the Relief Society.[41] Sister Johnson explained that the missionary elders, who were responsible for the Relief Society programs, were hardly sad to pass it on to her. In January 1959, Sister Chiu Siou Ping (Donna) (邱秀平) became Johnson’s companion and the first local sister missionary from Taiwan. From Sunday evening until Saturday, they traveled by train to hold Relief Society throughout the week.[42] Sister Koot Siu Yuen (Nora), a convert from 1950, was the first Chinese sister missionary from Hong Kong.[43] She was serving in Hong Kong until she was sent to Taiwan in 1959 to help Johnson, staying several weeks to visit branches to help set up the Relief Society.[44] These sisters were the first sister missionaries to serve in Taiwan. Their efforts brought about the early beginnings of the Relief Society organization in Taiwan.

The first sister missionaries to serve in Taiwan. From left to right: Betty Johnson from the US, Chiu Siou Ping (Donna) from Taiwan, and Koot Siu Yuen (Nora) from Hong Kong. Johnson served with Chiu and Koot while in Taiwan. Chiu was the first Chinese sister missionary from Taiwan when she became Johnson's companion in January 1959. Courtesy of Heaton family.

The first sister missionaries to serve in Taiwan. From left to right: Betty Johnson from the US, Chiu Siou Ping (Donna) from Taiwan, and Koot Siu Yuen (Nora) from Hong Kong. Johnson served with Chiu and Koot while in Taiwan. Chiu was the first Chinese sister missionary from Taiwan when she became Johnson's companion in January 1959. Courtesy of Heaton family.

Sister Chen Lin Shu-Liang (陳林淑良) became the first local Chinese sister to serve as a Relief Society president in 1958. In the spring of 1957, Elders Kitchen and Wood knocked on her door on a rainy day and asked if they might come in to teach her. She asked them to return next Saturday when her husband would be home. During their first lesson, the Chens realized that the missionaries’ Chinese was not that good, so they asked the elders to teach in English, to which the missionaries were more than glad to oblige. When the Chens had to travel, they left notes to cancel the lesson with the missionaries, hoping they would not return; but the missionaries kept coming back. Finally, one day, the Chens planned to tell the missionaries they did not want to have any more lessons. It was raining pretty hard, and the missionaries were soaked when they arrived. When Sister Chen gave them a towel to dry off, one of the missionaries said, “It doesn’t matter that we are wet; as long as you are willing to listen, we are happy to come teach the word of God.” Sister Chen was touched by their patience, persistence, and sacrifice during the six months they were being taught.[45]

Sister Chen gained her testimony after studying 2 Nephi and accepted the invitation to be baptized. On 28 September 1957, a holiday celebrating Confucius’s birthday, a group of American members took fifteen investigators to Wu Lai Canyon. There, Sister Chen was baptized by Elder Wood. She recounted, “When I came out [of the water], I could feel the sunlight shining on me.” A beautiful spirit attended her that day. Elder Wood’s patience brought many into the Church, including Sister Chen’s husband, Chen Meng-Yu (陳孟猶), who was baptized on 25 January 1958, and was among those ordained a high priest by then-Elder Gordon B. Hinckley on 26 April 1976.[46] Sister Chen was surprised when she was asked to teach an MIA (Mutual Improvement Association) class ten days after her baptism. When the Taipei Branch was created, she was called to be the Relief Society president.[47] Chen recounts the day that Elder W. Brent Hardy and Sister Johnson visited her:[48]

Sister Chen Lin Shu-Liang and her husband Chen Meng-Yu at the 40th anniversary of the Church in Taiwan in 1996. In 1958, Sister Chen was the first Chiense sister to serve as Relief Society president in Taiwan. Courtesy of Richard Stamps and Wendy Jyang.

Sister Chen Lin Shu-Liang and her husband Chen Meng-Yu at the 40th anniversary of the Church in Taiwan in 1996. In 1958, Sister Chen was the first Chiense sister to serve as Relief Society president in Taiwan. Courtesy of Richard Stamps and Wendy Jyang.

They came to my home and asked me to organize a Relief Society. So they hire a pedi-cab and ask me and Sister Johnson to go to every sister’s home to ask them to come to the church to have the first Relief Society meeting . . .

I was called to be the first branch Relief Society president. At the time we don’t have any Chinese copy materials. Sister Johnson give me a magazine, a Relief Society magazine. All the lessons were printed inside. At that time we don’t have many sisters who can understand English. So I have to teach the Relief Society lesson. The other lesson I translate[0] into Chinese and give the sisters to teach in the Relief Society. I was so afraid.[49]

Sister Chen said to Sister Johnson, “I don’t know anything about Relief Society. How can I be president of this organization?” Johnson replied, “I [will] work with you together.” Two months later, Johnson concluded her mission and returned to the United States, so Chen’s fears were not totally resolved. Nevertheless, Chen continued to work hard to establish the Relief Society and received support from many of the sisters.[50] After a year or two, her son failed the college entrance exam and blamed her for spending more time at church than at home, tutoring him, so she asked to be released from her calling. At the same time, Brother Hu Wei-I (胡唯一) was asked to replace Brother Liang Jun-sheng (梁潤生) as the new branch president. Hu’s response was, “I can accept. The only condition is Sister Chen [has] to be the Relief Society president.” When Mission President Robert S. Taylor and Brother Wu asked Chen to continue as the Relief Society president, she told them she could not because her son needed her. Taylor said, “I promise you [that] if you do God’s [work], God will take care of your other business, your other things.” Chen’s response was, “If you promise this, maybe I can.” She continued to serve and said, “My son really passed the examination. After that . . . my two children were able to pass their examination. . . . So I do not worry about my children’s business [anymore] . . . President Taylor’s promise [was] fulfilled.”[51]

Moreover, there were not many Chinese LDS materials at the time. Sister Chen said that about a year after the first Chinese LDS hymnbook was compiled, there were about one hundred hymns. But later on, there were two hundred hymns. Chen helped to translate about twenty-five songs in the hymnbook, and she later worked for the Church Translation Department for eight years.[52] During her service, she also assisted the wives of five mission presidents. In addition, after the Taipei Stake was organized, she served as the stake Relief Society president for many years. For the October 1973 general conference, Mission President Malan Jackson suggested that Chen attend to represent the Taiwan Relief Society sisters. So the Chens saved money to purchase their plane ticket, and traveled to Utah for the conference. While they were there, on 9 October 1973, they were sealed in the Salt Lake Temple by Elder Edward H. Sorenson. The Chens served for many years as ordinance workers after the Taipei Temple was dedicated, and their faithful service has been an example to the Saints in Taiwan. In 2006, at the fiftieth anniversary of the Church in Taiwan, Sister Chen said, “I am almost as old as the Church!”[53]

Spreading the Gospel to Other Cities

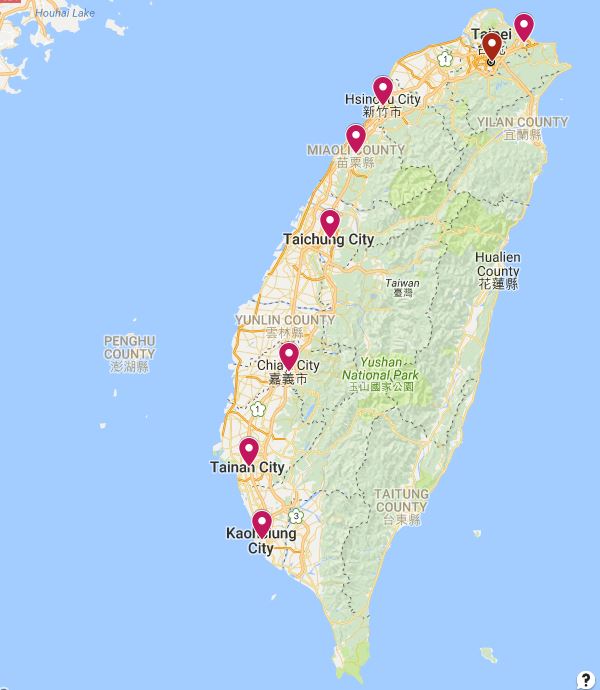

Missionary work was progressing, but thus far, it was primarily centered in the city of Taipei. In 1957, President Heaton felt impressed that it was time to branch out and spread the gospel to other cities. He was also concerned that the missionaries were getting burned out. Heaton assigned Elders Fish and Kitchen to go on a weeklong “vacation” to survey the island and explore potential cities to open for missionary work.[54] According to Kitchen, this provided “needed . . . R & R time in conjunction with missionary work. As it turned out, it was very rejuvenating to [their] bodies and spirits. It was very relaxing not to worry about any meetings and simply scout around areas that we thought would be productive to missionary work.” During their trip by train down the west coast, they identified various potential cities including Taichung, Chiayi, Tainan, and Kaohsiung. They traveled by bus up the east coast, visiting the small rural towns of Taitung and Hualien. They passed by Keelung and finished circling the island when they arrived in Taipei.[55]

Not long after, President Heaton came to Taiwan with his family for two weeks. On 26 November 1957, Heaton left Taipei with Elders Fish and Wiser to tour possible cities to further expand missionary work. They stopped in Taichung briefly for two and a half hours to survey the city. However, Heaton was more impressed with Tainan, the next city they visited. Their day concluded when they arrived and spent the night in Kaohsiung. The next day, after exploring the large industrial city of Kaohsiung, they headed back north on the train, stopping at two or three smaller towns.[56] On 2 December 1957, Fish recorded receiving a new assignment from Heaton.

President Heaton called me into the office and explained that missionaries would go to Tainan first and that they would go as soon as arrangements could be made. He said that the elders going down there would have to learn Taiwanese. It all sounded real good, then he said, I have decided that I want you to be the one to start the work there.” Of course that meant that I would be released from my assignment as Supervising Elder, and I would start to learn a new language . . . which is just as different from Mandarin as French is from English.[57]

To Tainan and Other Cities

On 31 December 1957, Fish and his new companion, Elder Thomas Nielson, moved to Tainan to open a new branch of the Church. Tainan had many Chinese military personnel. The missionaries tried a new approach by going door-to-door to pass out little tracts and invite people for a study class, which proved to be quite successful. When Elder Goodfellow replaced Nielson in March, they had many investigators at both their Taiwanese and Mandarin Sunday School classes. On 11 June 1958, Fish and Goodfellow baptized the first converts in Tainan: Sister Chou Ni Fang-Lan, followed by Brother Lin Chu-Nan.[58] Goodfellow felt their success was due to their persistence. He remembered a house they visited several times until “finally on the 8th visit we met the father of the home. Not only did he welcome us but after I was transferred . . . Brother Chen was baptized and became the first Chinese branch president of the Tainan Branch.”[59]

In 1958, the Church expanded outside of Taipei and Keelung in the North and moved into central and southern Taiwan. After Tainan, new branches were opened in Taichung, Kaohsiung, and Hsinchu. Hsinchu proved to be more difficult due to the anti-Mormon efforts by the Catholics and other Protestant churches. Missionaries also attempted to study and teach in the Taiwanese language in the southern part of the island, but they found predominantly Mandarin speakers interested in meeting with them.[60] By 1959, Chiayi and Miaoli would also be added.

The first eight branches created in the Taiwan by 1959. Courtesy of Chou Po Nien (Felipe).

The first eight branches created in the Taiwan by 1959. Courtesy of Chou Po Nien (Felipe).

To the Remote Villages

The missionaries took the gospel to the largest cities, as well as the remote villages on the island. Elder W. Brent Hardy recollected when he went with the elders “down south” to a remote village far east of the rail line, followed by a bus ride to the hinterlands:

The village was not large and it seems that almost everyone came to greet us. How long, if ever, has it been since a “Foreign Devil” had visited their village? . . . The room was small, maybe twenty by twenty. It was full . . . There were no electric lights in the room, or the village. Candles and lanterns were available for our use. When it was dark we would have to move the candle up and down the flannel board so the people could see the word strips and pictures. The press of people made it necessary to hang our flannel board on the wall and then almost stand with our backs tight against the wall to give the lesson.[61]

Hardy then noticed the beautiful reflection of the full moon upon the water covering the rice paddies. This was a beautiful and magnificent view. He continued:

As I stood gazing at this splendid scene I was transported in my mind, it seems, to a high place. Not a cloud nor a mountain, but somehow suspended in space, yet not so far that I couldn’t see the details on earth. From this place I could see us in our journey to this remote village. I could see my home in the United States. I could see my friends, my girlfriend, the University of Utah, and my family. The distance between home and that village seemed overwhelming. The question came to my mind, “Why have you left your family, friends, schooling, and all that is dear to you to travel the many thousands of miles to come to this land to the end of the earth, and then today journeying since early morning by train, bus, and bicycle to come to this small obscure village. Surely there must be a thousand thousands of places like this in the world?”

. . . I was quickened by the spirit and the answer to my query poured into my mind in such clarity that I have never forgotten it. “You have come all this way to tell this people the most important thing that they will ever know in their lifetime. There is a true and living God. He is their Father. That Father has a Son named Jesus Christ and He is their Savior. That Father and His Son appeared to Joseph Smith in the United States in 1820. Joseph Smith was a Prophet and God used him to establish His true Church on the Earth. You represent that true church. It is called The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. There is a living prophet on the earth now and he lives in the United States. His name is David O. McKay!”[62]

Another experience, shared by President Heaton, illustrated the hunger in Taiwan to learn the gospel. He reported that during a train ride in Taiwan, in which he hoped to catch a few hours of sleep, one person after another kept asking him questions about God and the restored gospel:[63]

Once onboard [the train], I placed my pillow on the window and got comfortable for the four hour ride to Taipei. . . . Suddenly my seat mate jabbed me with is elbow and asked me what my name was? I told him and intended to go back to sleep. Again he poked me and inquired what I was doing in Taiwan. I told him I was a missionary and tried to go back to sleep. He again interrupted my sleep by suggesting that if I was a missionary, I should have a message for him. I did! My message was to leave me alone and let me sleep . . . but I could not deliver this message. I thought I could give a brief introduction to the Church and still get back to my own schedule . . .

My tormentor had several [more] good questions, which I tried to answer. From behind me a voice chimed in asking another question. . . . Two others from across the aisle joined in with comments and questions. By the time we reached Tainan, seven people were involved in a religious discussion.[64]

Between Kaohsiung and Taipei, some of the participants left the train while others got onboard and joined in the conversation. Heaton estimated that about 10 percent of the people in the train car voluntarily joined the ongoing gospel discussion. One Chinese man said, “Now I know how you can say there is a God.” As Heaton left the train, three soldiers followed him to continue the conversation. He finally gave them the address for the missionaries and caught a cab for the airport. He later recorded, “This train ride in Taiwan taught me that there are no circumstances under which we cannot be used by the Lord to deliver the message of the Gospel.”[65]

Kaohsiung Branch, circa 1958. Courtesy of Colin Betts.

Kaohsiung Branch, circa 1958. Courtesy of Colin Betts.

Changes to the Branch Leadership

As noted earlier, the Church in Taiwan began with the LDS servicemen and their families stationed in Taiwan, with Stan Simiskey called as the first branch president in Taiwan. The missionaries and members loved the Simiskeys, who served until they finished their tour of duty and returned to the United States. Brother Lyle Simpson was called as the new branch president and served until his tour of duty concluded. By this time, President Heaton felt it was time to begin shifting local leadership responsibility from the LDS military servicemen to local Chinese members. Heaton created two branches, a military branch and a Taiwanese branch, which began to hold separate meetings in May 1958.[66] Elder Kitchen recorded his call to preside over the Taiwanese branch:

On April 13, 1958, President Heaton called me to be the Taipei Taiwanese Branch President. His specific instructions to me were to work with the members and strengthen their testimonies. . . . Member attendance at Sacrament Meeting was between 25 to 30 percent. I was told to choose a counselor to assist me in the work. After some prayer and contemplation, I was impressed to call Brother Tseng Yi-Chang to be my counselor. Brother Tseng was the first person I had baptized, and he had remained very faithful since that time. I don’t remember his exact age, but he was around 40 years old. He would bring not only spirituality, but also maturity to his calling. He had already received the Aaronic Priesthood, but was to receive the Melchizedek Priesthood and be ordained to the office of elder in conjunction with his calling in the Branch Presidency. And so, on April 20, 1958, I laid my hands upon Brother Tseng’s head and ordained him an elder in the Melchizedek Priesthood. He thus became the first Chinese brother in Taiwan to receive the higher priesthood.[67]

Kitchen added that having a Chinese brother in the branch presidency, who also held the Melchizedek Priesthood, caused the Church to “expand in a dramatic way.” Kitchen and his counselors worked to bring back those who had become inactive and helped teachers in their lesson preparation before Sunday. Kitchen was released as the branch president on 14 September 1958, when he concluded his mission and returned to the United States.[68] As a branch president, Kitchen helped to increase sacrament attendance from 30 percent to 66 percent.[69]

Taipei Branch in 1958 at the Guiyang chapel, which was used to house missionaries, mission home, and Taipei Branch. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchen

Taipei Branch in 1958 at the Guiyang chapel, which was used to house missionaries, mission home, and Taipei Branch. Courtesy of Weldon Kitchen

President Heaton’s ability to visit Taiwan was limited because of his other responsibilities throughout the various areas covered by the Southern Far East Mission. He was concerned that some missionaries disregarded mission rules owing to the lack of direct supervision by the mission president. Toward the latter part of 1958, Heaton assigned one of his counselors in the mission presidency, W. Brent Hardy, to live in and supervise the work in Taiwan. This was a significant change to help the work progress at a faster pace.[70] Hardy arrived in September 1958 and was instructed to remain in Taiwan for at least six months. In December, Heaton held a member conference at Sun Moon Lake to organize two districts in Taiwan. Hardy retained supervision of the North Taiwan District, which included Taipei and Hsinchu, and Ronald M. Walker was called to preside over the South Taiwan District comprising Taichung, Tainan, and Kaohsiung.[71]

The First Chinese Branch President

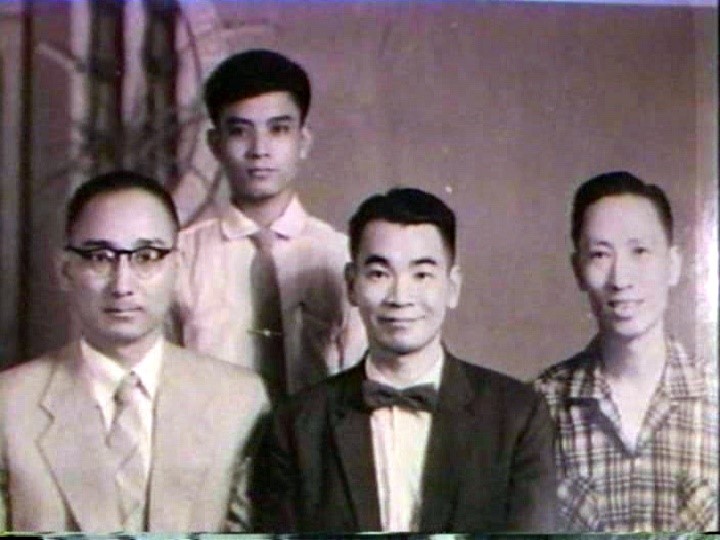

First Taiwanese branch president, Liang Jun-sheng (front ceter), circa 1959. Elder Mike Walker ordained and set apart Liang. Courtesy of Phil and Brenda Frandsen.

First Taiwanese branch president, Liang Jun-sheng (front ceter), circa 1959. Elder Mike Walker ordained and set apart Liang. Courtesy of Phil and Brenda Frandsen.

Liang Jun-sheng (梁潤生) became the first Chinese Branch President in Taiwan in 1959. Liang was born in China in 1914, studied to be a teacher, and married his wife in August 1946. After World War II, his professor moved to Taiwan after being hired as a director of a museum and invited Liang to come work for him. While in Taiwan, the Liangs had two boys and one girl. Later on, he taught at Taiwan University until his retirement in 1984.[72] But Liang struggled while working at the museum because he felt undervalued and lonely. During this time of difficulty, Elders Williams and Walker knocked on his door. The missionaries used a flannel board, had several lessons to teach, and used an old Chinese Bible. Liang explained that their biggest challenge was the lack of a Chinese LDS scriptures, but the few pamphlets translated into Chinese were very helpful. After several lessons, he was taught about the Word of Wisdom.[73] Liang said:

Not smoking was not a problem, not drinking alcohol was not a problem, not drinking coffee was not a problem, because the Chinese people don’t have a habit of drinking coffee. But as far as drinking tea, plain water did not taste well, so adding some tea leaves tasted better. At home, I still had a lot of tea leaves. So I told the missionaries I would consider being baptized after I finished drinking all my tea. Because not obeying the Word of Wisdom and not obeying the other commandments after baptism was not good. For me, either I don’t do something or I do it all the way. So after the tea was finished, I got baptized on August 1958. . . . My wife and I were both baptized.[74]

Soon after Liang was baptized, he was called to be the Sunday School teacher and supervisor. Since he was not a teacher nor had studied the Bible previously, teaching was a challenge. Since the lessons were not in Chinese, the missionaries assisted Liang as he prepared to teach.[75]

Liang was ordained a priest so he could baptize his two sons, Liang Shih-An (梁世安) and Liang Shih-Wei (梁世威), who were eleven and eight years old respectively when their father was baptized. Liang’s youngest son remembered that it was a very cold day and “someone boiled a kettle of water and poured it into the baptismal fount,” but it didn’t help much. After his father baptized him, he ran about seventy feet into the Church building and out of the freezing cold.[76] Liang’s oldest son, however, did not want to be baptized. Nevertheless, his father was firm, and both sons were baptized on 28 December 1958.[77] Liang Shih-An recalled that he was in sixth grade, and because there were no other Christians at his school, he didn’t want to be baptized. But his father said, “If you don’t get baptized, you are not my son.” Liang Shih-An, then twelve years of age, cried on his way to his baptism. Years later, he expressed his gratitude that his father insisted on him being baptized into The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[78] Liang Shih-An learned much by watching his father serve the members and missionaries in their small branch. For example, after a typhoon, his father visited each family in the branch to help repair their roof. In addition, his father always invited the missionaries to their home for dinner. Back then, members and missionaries were very close, and the branch was like a close-knit family.[79] His father felt it was his responsibility to assist and care for every member of the Church. This included caring for the sick and comforting the families of the deceased.[80]

After serving as a branch president, Liang Jun-sheng also served as a district president, counselor in the Southern Far East Mission presidency, first counselor in the first stake presidency in Taiwan, and stake patriarch. Serving as a patriarch was challenging for Liang because he had to travel extensively to provide patriarchal blessings for the members, including those in Hualien and Taitung on the east coast. For each blessing, Liang had to create three handwritten copies, one for the Church, one for the member, and one for the patriarch. He often felt the Holy Ghost guiding him as he gave each patriarchal blessing. Despite battling with four different types of cancer throughout his life, he continued to serve with the Lord’s help.[81] His devoted service and example was a blessing to all. Both of his sons would serve as stake presidents in later years, with the oldest also serving as a regional representative and as the first Chinese Area Seventy from Taiwan.[82]

Conclusion

The establishment of the Southern Far East Mission and the arrival of the first four missionaries to Taiwan commenced “a marvelous work and a wonder” among the Chinese people on the island. The delay to obtain the necessary visas and the waiting period in Hong Kong provided the missionaries an opportunity to study and prepare their leadership and language skills before they entered Taiwan. With the help of LDS servicemen stationed there and the first Chinese members in Taiwan, the missionaries began to teach and baptize the first converts in the Taipei area. Despite the tragic death of Elder Madsen, missionary work grew in Taipei and later expanded to the southern regions of the island. Church membership grew to 371 people by 1959.

The establishment of the Relief Society further strengthened the sisters in Taiwan. This, along with the call of the first Chinese Relief Society and branch presidents in Taiwan, helped to lay a foundation for the Church. While serving as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve, Elder Gordon B. Hinckley said:

The Orient, of all areas of the world, is perhaps least understood by the people of the West…

[LDS missionaries] have gone in response to calls from the Prophet of the Lord . . . It has not been easy for these missionaries. They have known sickness and abuse. They have fasted for the power of the Lord to learn the languages of these areas, strange and terrifying to the newcomer. They have prayed for the Spirit to touch the hearts of the people, most of whom know little or nothing of the Lord Jesus Christ. They have witnessed the outpouring of that Spirit in a measure wonderful to behold. And they have developed a love for these people among whom they have labored, a love that never seems to dim, but which grows brighter and stronger with the passing years.[83]

The early missionaries to Taiwan were indeed among the “other choice spirits who were reserved to come forth in the fullness of times to take part in laying the foundations of the great latter-day work”[84] among the people in Taiwan. Although these missionaries faced many challenges to adjust to the culture and learn the language, they were instrumental in opening the first small branches throughout Taiwan that would later grow into wards and stakes in the coming decades. Their sacrifice and service will be remembered for years to come, and their names and memories will be cherished and honored by their early converts and future generations.

Notes

[1] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 38–41; H. Grant Heaton to Simiskey, 8 May 1956, copy in possession of authors. Note that records of the departure date from Hong Kong differ between 1 and 2 June, and arrival date in Taiwan also differ from 3 and 4 June. However, both the letter from Heaton and journal by Kitchen suggest the most likely arrival date to be 4 June.

[2] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 41–42; Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 7–8.

[3] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 8.

[4] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 43–44.

[5] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 8–9.

[6] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 44–46.

[7] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 69.

[8] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 54, 69.

[9] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 70–71.

[10] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 67–69.

[11] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 11.

[12] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 71.

[13] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 69.

[14] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 69–71.

[15] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 11.

[16] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 71.

[17] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 12–13.

[18] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 13.

[19] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 74.

[20] Heaton, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 521–23.

[21] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 13.

[22] Heaton, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 522–23.

[23] Weldon Kitchen, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, Southern Far East Mission, 1955–59, 492–95.

[24] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 13–14.

[25] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 14.

[26] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 14.

[27] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 12.

[28] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 12.

[29] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 14.

[30] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 14–15.

[31] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 15.

[32] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 74–75.

[33] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 74–75.

[34] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 75.

[35] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 75.

[36] Heaton, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 36.

[37] Heaton, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 107–8.

[38] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 70.

[39] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 70.

[40] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 70.

[41] Bernard E. Knapp, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, Southern Far East Mission, 1955–59, 497.

[42] Betty Johnson Morris, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, Southern Far East Mission, 1955–59, 526–27.

[43] Heaton, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 35.

[44] Knapp, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 497.

[45] Richard Stamps and Wendy Shamo, The Taiwan Saints (self-published book commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the Church in Taiwan, 1996), 19–20.

[46] Stamps and Shamo, The Taiwan Saints, 19–20.

[47] Stamps and Shamo, The Taiwan Saints, 19–20.

[48] Chen Meng-yu and Lin Shu-liang, interview by Melvin P. Thatcher, 22 October 2001, Taipei, Taiwan, Church History Library (OH 2947).

[49] Chen Meng-yu and Lin Shu-liang, interview.

[50] Chen Meng-yu and Lin Shu-liang, interview.

[51] Chen Meng-yu and Lin Shu-liang, interview.

[52] Chen Meng-yu and Lin Shu-liang, interview.

[53] Stamps and Shamo, The Taiwan Saints, 19–20.

[54] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 17–18.

[55] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 17–18.

[56] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 77.

[57] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 77.

[58] Fish, Missionary Experiences of Melvin C. Fish, 77–82.

[59] James L. Goodfellow, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, Southern Far East Mission, 1955–59, 467.

[60] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 156.

[61] W. Brent Hardy, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, Southern Far East Mission, 1955–59, 480–82.

[62] Hardy, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 480–82.

[63] Heaton, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 204–6.

[64] Heaton, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 204–6.

[65] Heaton, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 204–6.

[66] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 19.

[67] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 19–20.

[68] Kitchen, The Taiwan Experiences of Weldon Kitchen, 20–21.

[69] Kitchen, in A Documentary History of the Chinese Mission, 1949–53, 492–95.

[70] Britsch, From the East, 254.

[71] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 157–58.

[72] Liang Jun-Sheng, interview by Melvin Thatcher, 23 October 2001, Taipei, Taiwan, Church History Library (OH 2954).

[73] Liang Jun-Sheng, interview.

[74] Liang Jun-Sheng, interview.

[75] Liang Jun-Sheng, interview.

[76] Liang Shih-Wei to Chou Po Nien (Felipe), email, 7 March 2016.

[77] Liang Jun-Sheng, interview.

[78] Laing Shih-An, interview by Chou Po Nien (Felipe), 20 November 2015, Taipei, Taiwan; Liang Shih-An to Chou Po Nien (Felipe), email, 17 and 23 October 2016.

[79] Laing Shih-An, interview.

[80] Liang Jun-Sheng, interview.

[81] Liang Jun-Sheng, interview.

[82] Laing Shih-An, interview; Liang Shih-Wei, interview.

[83] Gordon B. Hinckley, “The Church in the Orient . . . Prologue,” Improvement Era, March 1964, 166–67.

[84] D&C 138:53.