A Firm Foundation

The First Mission and the Church Educational System (1970–75)

Chou Po Nien (Felipe) (周伯彥) and Chou Sin Mei Wah (Petra) (周冼美華), “A Firm Foundation: The First Mission and the Church Educational System (1970-75),” in Voice of the Saints in Taiwan, ed. Po Nien (Felipe) Chou (周伯彥) and Petra Mei Wah Sin Chou (周冼美華) (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 141-178.

The 1970s were a decade of economic growth and political upheaval in Taiwan, but it was also a time period when the Church permanently established “a firm foundation” in Taiwan. How did the political and religious dynamics in Taiwan affect the development of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Taiwan during the 1970s? This chapter examines major historical events of the Church—including the establishment of the first mission and first seminary and institute programs—placed within the context of the political and religious climate in Taiwan in the early 1970s. In addition, it explores the translation and publication of the Chinese Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price. Church membership grew from 3,509 at the beginning of the 1970s to 8,367 by the close of this decade.

Taiwan Gains Its First Mission

In the 1960s, Elder Gordon B. Hinckley, then a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, toured the Asian missions. As early as 1966, Elder Hinckley recommended that Taiwan be made into a separate mission. W. Brent Hardy, who had served as a young missionary in the Southern Far East Mission in the 1950s, was serving as the mission president of the Southern Far East Mission. On 11 November 1969, he became the president of the Hong Kong–Taiwan Mission, following major organizational changes and the creation of the Southeast Asia Mission that year. In 1970, the Hong Kong–Taiwan Mission had 9,442 total members organized into branches and districts and between 153 and 159 missionaries, and they also had 789 convert baptisms that year.[1]

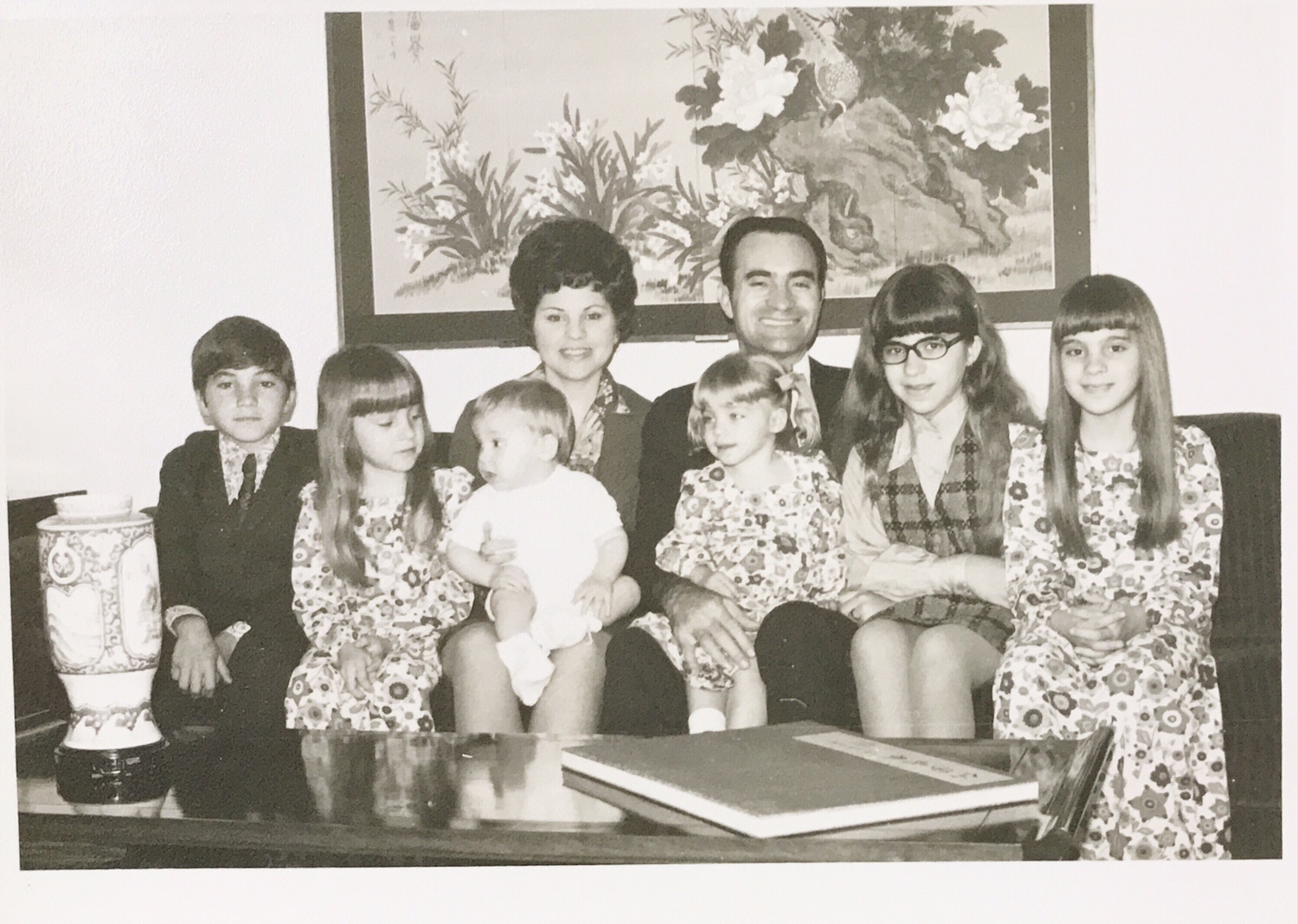

Malan R. Jackson with his wife and children. Jackson was the first president of the Taiwan Mission in January 1971. Courtesy of Liang Shih-Wei (Carl).

Malan R. Jackson with his wife and children. Jackson was the first president of the Taiwan Mission in January 1971. Courtesy of Liang Shih-Wei (Carl).

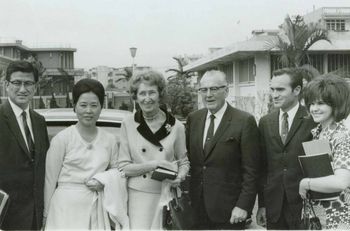

On 1 January 1971, less than fourteen months after the organization of the Hong Kong–Taiwan mission, Taiwan became its own Mission. Malan R. Jackson was called to preside over this new Taiwan Mission, which consisted of approximately 4,500 members, 90 missionaries, and 50 convert baptisms each month.[2] Jackson had been among the first eight missionaries in Hong Kong and had prior exposure to the Chinese language and culture. He was an administrator at Arizona State University in Tempe, Arizona, at the time of his call.[3] The Taiwan Mission was the ninety-third mission of the Church.[4] Shortly after the Jacksons arrived in Taiwan, they received a visit from President Harold B. Lee, then the First Counselor in the First Presidency. This would be the second visit by a member of the First Presidency to Taiwan. President and Sister Lee were accompanied by Elder and Sister Komatsu as they traveled with the Jacksons to visit the Saints in Taiwan. During his visit, President Lee challenged the members “to prepare themselves . . . to receive the greater blessings of the Lord.”[5]

President Harold B. Lee visits Taiwan in 1971. From left to right: Elder and Sister Komatsu, President and Sister Harold B. Lee, and President and Sister Malan Jackson. Courtesy of Malan Jackson.

President Harold B. Lee visits Taiwan in 1971. From left to right: Elder and Sister Komatsu, President and Sister Harold B. Lee, and President and Sister Malan Jackson. Courtesy of Malan Jackson.

The establishment of the Taiwan Mission was important to further the growth of the Church in Taiwan. Since the 1950s, the missionaries and members in Taiwan had lacked local supervision from the distant Southern Far East or Hong Kong–Taiwan Missions. In many ways, they felt neglected by the leaders in Hong Kong. R. Lanier Britsch, an LDS scholar, noted that supervising the work in Taiwan from a distance was challenging and limited in its ability to move the work forward. As a result, “the Church did not take hold in Taiwan quite as quickly as it did in Hong Kong” during the 1950s and 1960s.[6] The effect of having a mission president presiding, living, and directing the work in Taiwan was tangible. The prior feelings of neglect from distant Church leaders were quickly forgotten, and the Saints in Taiwan moved forward with renewed commitment and consecrated effort.[7]

The creation of the Taiwan Mission in 1971 allowed for local direction and supervision, with an onsite mission president who held keys for the work in Taiwan. For example, Jackson recognized the local challenges, such as low church attendance and activity, and focused on bringing the less active back to church. In addition, he sought to strengthen local leadership by transitioning branch leadership from American missionaries to local Chinese members. Moreover, missionaries in Taipei and its vicinity formed the “Voice of the Saints” choir in 1971. This choir sang at hospitals, department stores, public places, and so forth. They also appeared regularly on television programs, bringing additional exposure and publicity for the Church. By 1972, there were twenty-four branches in Taiwan, compared to nineteen the previous year.[8]

In addition, local Chinese converts served as full-time missionaries, and the number of people serving missions grew substantially in the 1970s. Wang Li-Ching (王麗卿), for example, was a teenager in 1967 became and the first in her family to accept the restored gospel. As a twenty-year-old college student in 1971, she was going home after her final exams and felt impressed to get off the bus to stop by the Taiwan Mission office. Unsure why she was there, she entered the chapel and mission office. She was met by President Jackson, who was prompted to call her on a mission.[9] Although she was not yet twenty-one years old, nor had she applied to be a missionary, Wang readily accepted and served and assisted Jackson. Wang didn’t even get to go home that day; instead, Jackson called her father and had her family bring her clothes to the mission office. Wang served for three months as his secretary and translator. She helped to translate letters to branch presidents throughout Taiwan as well as letters to new converts.[10] She was among the many young adults in Taiwan who accepted calls to serve and assist in the 1970s. There were twenty-eight local Chinese missionaries by 1971.[11]

During the 1960s and 1970s, the financial support from the United States and other nations led to dramatic economic growth in Taiwan. During the Cold War era, the United Nations and other Western nations recognized Taiwan or the Republic of China (ROC) as the legitimate Chinese government. However, the United Nations formally changed China’s seat from the ROC to the government of mainland China (People’s Republic of China, or PRC) in 1971.[12] About a month after that, Elder Marvin J. Ashton, then an assistant to the Twelve Apostles, was sent to visit the Saints in Taiwan in November 1971.[13] Ashton and the LDS Church maintained a neutral position and avoided making political statements, since the Church and its missionaries have “no political agenda, . . . circulate no petitions, advocate no legislation, [and] support no candidates.”[14] By contrast, the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan issued three public statements critical of the government in Taiwan in the 1970s, including “Public Statement on Our National Fate” in 1971.[15] Feng Xi noted the impact of this policy on the LDS Church and its development in Taiwan:

There was increased tension between the government and the Christian churches in Taiwan. . . . The Presbyterian Church had been in conflict with the Kuomintang. In the early 1970s, it sharply criticized the regime’s authoritarian structure. . . .

President Jackson instructed his missionaries to stay away from politics and refrain from sensitive comments. As a result, there never occurred a harsh confrontation between the Mormon Church and the Taiwan government. Problems like a rejection of visas to foreign missionaries never happened to the Mormons. This cautious and neutral political position of the Church, well observed by all later mission presidents, laid a good foundation for developing future relations between the Church and top Taiwan government officials in the 1980s.[16]

In 1972, US president Richard Nixon visited mainland China to help normalize relations, holding talks on a wide range of international and political questions.[17] Although the United States continued to support and recognize the government in Taiwan, there was increased concern and uncertainty among those living on the island. As the world turned its attention to China, the Church remained interested in and committed to its missionary efforts in Taiwan.[18] The establishment of the Taiwan Mission in 1971 helped to instill faith and hope among the Saints in Taiwan. While the people of Taiwan felt abandoned by the world, the Saints in Taiwan appreciated the care and interest of the Church leaders in Salt Lake.

Regional Representatives and Mission Representatives

As the Church continued to experience rapid growth worldwide, the First Presidency announced major new supervisory programs for missions and regions that would impact the work in Taiwan. The changes made in 1972 resulted in increased numbers of regional representatives and created a new position known as mission representatives of the Quorum of the Twelve. Three days before President Joseph Fielding Smith passed away, he explained the new changes when he spoke at the mission presidents’ seminar. He noted that regional representatives would go to mission districts to provide training and leadership opportunities for members worldwide, as they had been doing with stakes, while the mission representative would help train and increase effectiveness of missionaries.[19] He noted that additional regional representatives had been called, bringing the total to 108, along with 29 mission representatives. President Smith also said, “The new program calls for discontinuance of the supervision of specific areas of the world by members of the Twelve and other General Authorities.” “You mission presidents,” he said, “may expect the brethren of the Twelve to visit you periodically, but not in the capacity of area directors as has been the case in the past.”[20]

W. Brent Hardy from Las Vegas, Nevada, who had previously served as a mission president of the Southern Far East and Hong Kong–Taiwan Missions, was called as the new regional representative for the Hong Kong and Taiwan Missions. Edward Y. Okazaki from Denver, Colorado, was called as the new mission representative for the Japan Central, Japan West, and Taiwan Missions.[21] These changes would help missionary efforts, train members, and prepare future local leadership in Taiwan. The work of regional representatives and mission representatives of the Quorum of Twelve was important in providing additional supervision to help the mission and local leaders in Taiwan. Since Taiwan did not yet have a stake and had only mission districts at the time, expanding the role of regional representatives to help train local leaders and bring forth the full program of the Church to mission districts was particularly important to help develop local leadership and prepare them to become autonomous stakes. The work of mission representatives was equally significant to train and help increase the effectiveness of missionaries throughout Taiwan.

Health Missionaries

In 1971, Dr. James O. Mason, then the Church health commissioner, developed the health missionary program in response to President Harold B. Lee’s request to address the health needs of the members of the Church throughout the world. Missionaries with nursing skills and other specialized training were called to assist mission presidents and their wives to teach disease prevention among missionaries and members worldwide,[22] evaluate health resources, and address health issues.[23]

Following the organization of the Church’s health missionary program in 1971, a year later Sister Aira Gyllenbogel from Finland became the first health missionary sent to Taiwan. Health service missionaries taught healthcare and preventive medicine and were very successful in their efforts. In 1975, there were additional changes to the program, and these health missionaries became known as welfare service missionaries, with a more holistic approach that focused on all aspects of personal and family preparedness and welfare.[24] Sister Margaret Jensen, then a health missionary, explained that activities included connecting with local health organizations, surveying healthcare needs of members, preparing materials and teaching health-related lessons at Church and local agencies, preparing lists of local resources, supporting branch welfare-services committee meetings, and working with missionaries to improve their nutrition. For example, at a health open house held by the Taipei East Branch, health missionaries taught using displays on dental care, cancer prevention, and nutrition.[25] Health missionaries served both members and nonmembers of the Church, developed resources for future health missionaries, and utilized various methods to contact the people to address health issues.[26]

Health Missionaries teaching dental health at a public school in Taiwan, circa 1975. Courtesy of Margaret Jensen Kitterman.

Health Missionaries teaching dental health at a public school in Taiwan, circa 1975. Courtesy of Margaret Jensen Kitterman.

Sister Lin Mei Yu (林美玉) was a registered nurse and the first native health missionary in Taiwan when she was called as a full-time missionary in 1973. Lin was baptized in Fengyuan in 1972 and remembered receiving a call from President Malan Jackson asking her to serve a mission. She was not quite sure what that meant, but she was obedient and answered the call to serve. When her mother asked her how long it would be, she wasn’t sure and thought it might be for a month. Lin would serve for eighteen months, helping to teach members and missionaries about health.[27] Along with her responsibilities as a health missionary, Lin also helped teach other missionaries about the people, land, and culture in Taiwan. She was one of more than one hundred health missionaries of the Church during this period.[28] The establishment of the Taiwan Mission and the work of the health missionaries were important events in the presence of the Church in Taiwan.

Establishment of CES Programs

While the Church began to gain a firm foothold in Taiwan, certain individuals sought to provide weekday religious education for the youth in Taiwan. Some of these classes were held by expatriates living in Taiwan, and others were organized by the missionaries. A few of these programs were called “seminary,” and in some cases they may have attempted to use seminary materials (which had not yet been translated into Chinese).[29] For example, one early effort in 1965 included a gospel study class organized in Taichung for the youth. This effort provides an example of how early missionaries tried to duplicate seminary classes or weekday religious classes they had experienced in the United States.[30] According to the Seminaries and Institutes (S&I) annual report,[31] seminary officially started in 1968 in Taiwan and institute in 1973; however, records of specific seminary or institute classes prior to 1973 are not available.

In 1972, Neal A. Maxwell, then commissioner of the Church Educational System (CES), organized the Asia Educational Resources Project (AERP) with specialists from Brigham Young University. The members of the AERP committee visited and surveyed the educational needs of the members in Asia, including those in Taiwan. This committee found a perceived need for educational assistance, particularly a strong desire for religious education and scholarship.[32] The findings of this committee eventually resulted in various religious educators being sent abroad to help establish seminary and institute programs. In 1973, Alan R. Hassell and his young family were sent from the United States to Taiwan to help establish CES programs. Hassell set up the first CES office in Taiwan and visited branches throughout the island to help coordinate seminary and institute programs.[33]

When Hassell completed his mission in Taiwan back in May 1969, he wondered if he would ever return to the island. Hassell married his wife, Michele, and was hired to teach seminary in 1970. During a weeklong training at the Orem Seminary in Utah, Frank Day came to speak and talked about sending a brother to Japan and another to the Philippines. Day was a zone administrator for Asia who was working to begin seminary and institute in various countries. Hassell walked up to Day during the training and said, “You know, I served a mission in Taiwan. . . . If you’re ever going to need someone to go to Taiwan, I would really like to go back.” However, Day must have forgotten the conversation, and Hassell was assigned to teach in Tuba City, Arizona. Then, in January 1973, while Day was having a hard time finding someone to go to Taiwan, he was told there was one teacher in Tuba City who had served in Taiwan and spoke Mandarin Chinese. Day immediately asked Weldon Thacker in his office to phone that man. Thacker called Hassell and told him that “there’s an opening in Taiwan and we would like you to go.”[34] Married only three years earlier, Hassell took his wife and their two young children (ages one and two) on an incredible adventure. They were greeted by the mission president when they arrived in Taiwan in July 1973. The first few weeks were spent securing and furnishing housing as well as purchasing a Volkswagen to travel the length of the island.[35]

There were no Chinese seminary materials translated at the time, so efforts to do so began immediately. Sister Wang Li-Ching (王麗卿), Hassell’s new secretary, helped to translate the Tom Trails filmstrips so there would be some resources for use in the classroom. Wang, who previously served a three-month mission to assist President Jackson, became the first employee of the Church in Taiwan when she was hired to be the CES secretary for Hassell. Wang and her family were among those taught and baptized by Hassell when he was a missionary in Taiwan a few years earlier. Wang assisted with translation of materials, supervised two other part-time secretaries, and assisted Brother Hassell.[36] After Brother Hassell set up the first CES office in Taiwan in the basement of the Chin Hua Street chapel, he traveled with President Jackson to visit branches throughout Taiwan to help establish home-study seminary programs.[37]

Hassell reported that “one thing that really made it difficult [to start seminary] is that Chinese kids have what they call Pu Shi Pans or college prep classes. . . . They go every night plus Saturdays and half a day [on] Sunday.” This made it challenging to persuade the parents to allow their children to attend seminary. Initially, due to the demanding school and study schedule, seminary was adopted as part of the weekly Sunday School class. Hassell and Jackson visited several branches, which participated in seminary in 1973 and 1974. Initial “test” areas for S&I programs included Taipei, Taichung, Chiayi, Tainan, Kaohsiung, and Pingtung. Eventually, the adults began asking for an institute class as well. Ho Tung-Hai (何東海), who later became the first stake president of the Kaohsiung Stake, was asked to be the first institute instructor in Kaohsiung.[38]

Hassell labored diligently to establish S&I programs throughout the island. He taught institute classes in the Taipei chapel Tuesday through Thursday, in Taichung on Friday, and in Kaohsiung on Saturday. On Sundays, he would visit seminary classes as follows: Pingtung and Kaohsiung one weekend, Tainan and Chiayi the next, Taichung after, and home one weekend each month to fulfil his calling as a Scoutmaster for his ward.[39] Hassell put 30,000 miles in one year.[40] Hassell shared the following experience:

We received a letter in early September telling us that we would be hosting the Commissioner of Church Education, Neal A. Maxwell and his wife Colleen for a couple of days, he was touring the Far East and would spend a couple of days with each of the International Coordinators. . . .

CES had bought us a car which was nice, but had no air conditioning. Given the intense heat I tried to get air conditioning but was told that there was no budget for it, and moreover there were no parts available in Taiwan. We picked up the Maxwells at the airport and took them to Mongolian BBQ, which he approached hesitantly at first and then with enthusiasm.

When we picked them up at the Hotel the next morning, he allowed Colleen to sit in the front and he took the back seat. It was a hot and humid August day in Taiwan. After ten minutes in our hot car he inquired why we had no A/

C. I told him we had been told it wasn’t in the budget. He stated the conditions were inhumane and no one should have to deal with that. Before they left the next day he asked to use the office phone, called Salt Lake and informed [the head of finance] that CES was going to purchase a car with air conditioning for the Hassell’s. Seven months later we got our new Toyota with A/ C.[41]

The lack of translated materials was one of the initial challenges experienced. But once study materials began to be translated into Chinese, they were written on ink paper, printed on stencil, and distributed to students. Seminary classes were provided to youth ages fourteen to eighteen. Institute classes were provided to all adults ages eighteen to sixty due to lack of gospel scholarship among all new converts. Seminary and institute classes were held in local chapels once a week.[42] By the end of 1973, there were 64 students in Taiwan, and one year later, 104 had enrolled.[43] When Hassell and his family returned to the United States in December 1974, just eighteen months after they arrived in Taiwan, there were eleven seminary and seven institute classes in Taiwan.[44] In addition, Hassell had hired a local CES coordinator, Wan Kon-Leung (Joseph) (尹根亮), who was prepared to continue the program and take over as the coordinator of the country.

Alan Hassell, Michele Hassell, Wan Ng suk-Yi (Alice), and Wan Kon-Leung (Joseph) in December 1974. Brother Hassell served as the first CES coordinator in Taiwan, followed by Brother Wan. Courtesy of Alan Hassell.

Alan Hassell, Michele Hassell, Wan Ng suk-Yi (Alice), and Wan Kon-Leung (Joseph) in December 1974. Brother Hassell served as the first CES coordinator in Taiwan, followed by Brother Wan. Courtesy of Alan Hassell.

Wan was born in China in 1944, but his family moved to Hong Kong when he was six years old. After Wan was baptized in February 1961, he served as a missionary in the Southern Far East Mission in Hong Kong from 1965 to 1968. In 1971, he moved to Kaohsiung, Taiwan, to work as a factory supervisor and as an English teacher. He was still single when he was called to be a branch president.[45] Hassell recalled that during a visit to Kaohsiung, Wan took him to dinner to discuss the possibility of exporting teakwood to the United States.[46] Hassell shared the following experience:

I thought that [Wan] might be a good teacher because he was very eloquent and had great English, so he had a real command of all three languages. . . . I phoned Frank Day and I said, “I think I have found a good man.” He said, “Well, why don’t you work with him part-time and see what you can do?” And so I talked to Joe [Wan] and he did some supervisory work in Kaohsiung for us for a couple of months and seemed to do a really good job. I got a hold of Frank again and I said, “I think this man is going to really work out well.” And he said, “Well, I am coming over in a little while, so I’ll visit with him.” And so Frank showed up about a month or so later and Joe came up north and they visited for a while. Joe went back down, and Frank said, “He’s a good man. Go ahead and bring him on full-time.”[47]

In 1974, Wan moved to Taipei and became the first native CES coordinator in Taiwan. Wan and his fiancée were married in the Salt Lake Temple shortly thereafter. There were eleven seminary classes and seven institute classes in Taiwan during this time.[48] Efforts were made throughout the island to move the home-study seminary classes to a day other than Sunday. As the program continued to expand, with additional seminary classes, and an institute class in Taichung, Brother Wan hired Lee Ding Kuen (李定坤) to become the coordinator managing S&I programs in Kaohsiung in 1974.[49]

Establishing the S&I programs was challenging in those early days. Most seminary and institute teachers called were new converts who had limited understanding of the gospel. Constant turnover rates also made it difficult to provide a consistent program. Coordinators worked sixty to seventy hours per week teaching classes, training teachers, hosting “Super Saturdays,” visiting parents and priesthood leaders, and encouraging students. Asking parents to cover the cost for course materials was not so easy when parents felt that participating in seminary already required a substantial sacrifice of time. The difficulty was compounded when students had parents who were not members of the Church. Nevertheless, through coordination efforts with priesthood leaders, parents and youth were persuaded to make the additional efforts.[50]

An example of how the seminary program helped to prepare and develop local Chinese missionaries is illustrated by the experience of Juan Jui-Chang (阮瑞昌). He was young when he was taught the restored gospel and became a member of the Church in 1974. Like other new, young members, Juan began to attend seminary after he was baptized. In a retrospective account, he stated, “The reason I served a mission is because of [a] seminary teacher.”[51] Years later, Juan served as a stake president for the Taichung Taiwan Stake. Thereafter, Elder Juan served the members in Taiwan and other parts of Asia as an Area Seventy in Asia.

The institute program was also important in strengthening new converts. After Yang Tsung-Ting (楊宗廷) was baptized on 6 April 1973, he attended institute and was among the first institute graduates in 1977.[52] He would later serve as the stake president for the Taipei Taiwan West Stake and later as an Area Seventy in Asia. Both Elders Yang and Juan talked often about the importance of seminary and institute programs of the Church in their lives and the lives of other members of the Church throughout Taiwan.[53] Thus, seminary and institute were laying the spiritual educational foundations for Church leaders in the decades to come.

A highlight in 1978 was a three-day conference for single adults held in Shi Tou, Taiwan. This event brought together about three hundred institute students (including about eighty from Hong Kong). Church leaders invited single-adults throughout Taiwan and Hong Kong to gather in central Taiwan to strengthen the testimony of single adult institute students and providing meaningful association. Some were inspired to serve missions, while others found and later married their eternal companions. For example, Brother Tony Ling and Sister Wong Kam-Ping, who were assigned to lead and travel with the group from Hong Kong to the single-adult conference in Taiwan, were later married.[54] This activity and others provided opportunity for those who were single to be able to associate with other singles who had the same beliefs and values.

In 1978, Wang Lu Pao (王綠寶) was hired to help with CES programs in Taipei, and he later supervised the CES programs on the whole island when Wan was transferred to Hong Kong and Lee moved to the United States in 1979. For the next two decades, Wang oversaw most of the development of seminary and institute programs in Taiwan. He was instrumental in the strengthening and steady growth experienced during this period, at times responsible for the northern region of the country when there was a coordinator in Kaohsiung, and at other times solely responsible for all the CES programs in Taiwan. He traveled throughout the island to train and support volunteer teachers and spent countless hours visiting various cities to meet with priesthood leaders, teachers, parents, and students. He played a key role in establishing both home-study seminary and institute classes in many wards and branches of the Church in Taiwan.[55] By the late 1970s, there were more than 350 seminary and over 400 institute students in Taiwan. The establishment of the seminary and institute programs in Taiwan helped to strengthen the faith of new converts in the 1970s. These programs helped the members expand their gospel scholarship, strengthen their testimonies, and prepare missionaries and future Church leaders in Taiwan.[56]

Missionary Lessons Adapted to Local Culture and Customs

On 20 June 1974, the Taiwan Mission was renamed the Taiwan Taipei Mission. Thomas P. Nielson, an early missionary in the Southern Far East Mission, served as the Taiwan Taipei Mission president from 1974 to 1977. At the time Nielson received his call, he was a professor of Chinese literature at Arizona State University. His background and training was important in helping him fulfill his responsibilities as a mission president in Taiwan. His experience with and understanding of the Chinese culture were critical to the growth of the Church in Taiwan during this period. Feng Xi noted the following: “Nielson succeeded Jackson as the president of the Taiwan Mission. . . . Not long after his arrival, the Church held a meeting in Asia and asked its mission presidents to focus more on the increase of baptisms. After that, Nielson changed his style to more practical methods that would produce immediate results.”[57]

Elder Gordon B. Hinckely visits Taiwan, circa 1974. From left to right: Elder Hinckley, Taipei Mission president Thomas Nielson, and Chang I-Chin. Courtesy of Robert Suman.

Elder Gordon B. Hinckely visits Taiwan, circa 1974. From left to right: Elder Hinckley, Taipei Mission president Thomas Nielson, and Chang I-Chin. Courtesy of Robert Suman.

Important adaptation to the missionary lessons was developed by the Taiwan Taipei Mission under the leadership of President Nielson. The seventeen-lesson plan used by the first missionaries in Taiwan in the 1950s was replaced in the 1960s by the uniform six-lesson plan implemented by the Church Missionary Department in 1961.[58] Nielson used the uniform lesson plans by the Church Missionary Department but also implemented important adaptations based on his understanding of the local culture and customs, which helped increase the harvest of new converts in Taiwan.[59] Feng Xi credited Nielson for the immediate results: “Nielson, with a Ph.D. in Chinese language and literature, was a dynamic and culturally oriented mission president. . . . Nielson stressed the importance of missionary cultural awareness in order to make them carry out their proselyting in a Chinese way, which he believed would make proselyting more effective in the long run. Quite often he read poems of the Chinese Tang dynasty to his missionaries and did many other things to increase their cultural awareness.”[60]

Nielson recognized that as one sought to preach the restored gospel and help bring others unto Christ, it was helpful to have an understanding and appreciation for the culture and perspective of those being taught. While many Western countries were established with basic Judeo-Christian beliefs, this was not the case for most of Asia. The Taiwanese culture was heavily influenced by the tenets of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism. This made it difficult and led to challenges in the teaching and conversion of the people of Taiwan who lacked a basic knowledge and understanding of Christianity and its rudimentary tenets, teachings, and beliefs.

Moreover, the Chinese people had a deep sense of their duty to honor and respect their parents and ancestors. Those who joined the Church were often viewed by their families and friends as abandoning their Chinese values, practices, and traditions. Accepting Christianity was viewed as denial of family tradition and ancestor worship. Traditional Chinese families, many of whom were Buddhists, viewed conversion to Christianity as a great tragedy, bringing shame to the entire family.[61] Sister Wang Li-Ching’s (王麗卿) experience illustrates the cultural challenges in Taiwan:

While home alone, I heard knocking at the door. Answering the door, I was surprised to see two tall American young men standing in front of me with friendly smiles, asking me if I had ten minutes. I had never been so close to foreigners before and was quite amazed that they could speak Mandarin. I assumed that they got lost and needed help to find their way back home, so I thought I could spare ten minutes to help. After being seated, they began to introduce themselves as missionaries from a church with a long name and almost immediately asked if I had ever had questions about where I came from, why I was here and where I would go after this life. I couldn’t believe my ears—that someone actually knew what had been in my mind!

That day my questions were answered. When the missionaries told me about Heavenly Father, His begotten Son, Jesus Christ, Joseph Smith, and the Book of Mormon, I didn’t have any doubt in my mind that what they said was all true. It sounded like something I used to know, but just forgot. They were there to remind me of my eternal history. My heart was comforted and I happily agreed to welcome them back next week. So began my journey toward truth.[62]

While Wang felt great joy about the messages she heard from the missionaries, she also faced opposition. Wang continues:

A few weeks after I started taking the missionary discussions, a fortune-teller came to our house. . . . It was quite a common practice at the time. . . . He said that Mother had the favor of Buddha and that this family should not betray Buddha to believe in another god. Mother hesitated, but decided to tell him that one of her daughters was learning about Jesus Christ and seriously thinking about being baptized into that church. The fortune-teller’s comment was to not let her join in the Christian church; otherwise, Mom would die when she turned 43. Mom was 41 at the time. The entire family turned against me and warned me that I would be responsible if anything happened to Mom. Though I was sure about this new church, I felt great pressure from my family. I told the missionaries about this fortune-teller’s prediction. They asked if I would fast and pray with them. I agreed and so we did. That was the first time I ever fasted and prayed. We did for two days and two nights and after that we met at the meeting place (we didn’t have a chapel at the time—just a rented place) and prayed together. When I got home, Mom approached me and said that she wanted me to go ahead and be baptized. “I think your God will bless you and He will bless me, too,” she said.[63]

Wang was baptized, and over the next two years each of her family members also joined the Church. Her father had the most difficulty in conversion, largely because of his cultural commitments. Wang describes:

[My father] was a faithful investigator for almost two years. There were a few things that he needed to overcome. First of all, as the first-born son, he needed to carry the family name according to Buddhist ways. This meant that he needed to worship his ancestors twice a month with incense burning and candles lighted in honor of them, and offerings of chicken, pork, or ducks as sacrifices. In fact, for years before the visit of the missionaries, Mom and Dad had been the earliest worshippers to be in the Buddhist temple to show their sincerity and faith in order to be blessed with their needs. Secondly, they had big financial problems. Thirdly, Grandpa needed to understand about this decision to change beliefs. This problem was solved when Grandpa learned that we were required to do genealogy—something he was pleased to support. Finally, Dad, as a manager in his company, had been smoking and drinking, just like most businessmen did. He started those habits when he was a teen-ager, so it took him almost two years to quit. He finally did, because he wanted to be with us. Father was baptized on April 13, 1969, two years after I was baptized.[64]

Shortly after Wang’s father was baptized, Wang’s mother (at the age of forty-three) had to undergo a serious surgery. To those who had been critical of Wang and her family being baptized, this seemed like divine retribution. Wang continues:

[Our] relatives and neighbors began to spread the word that we deserved this curse because we betrayed our religion to believe in the western God. Father was logical and calm. He asked about the cause and the development of Mom’s tumor. Doctors told him that it took at least seven to eight years to develop that kind and size of tumor and we had joined in the church only two years before. Dad concluded that it had nothing to do with our new religion, but that it was time for us to show our faith in our Father in Heaven. He gathered all six of his children and asked us to fast and pray for Mom. . . .

Today, 83 years old, Mom is still very active in serving the Lord as a Relief Society leader and visiting teacher. Father was one of the first bishops in Taiwan ordained by President Hinckley, who affectionately called him “Pineapple Wang.” . . . Although half of my siblings went through special challenges in their lives and were inactive for several years, all six of us are now active in the Church along with most of our children and grandchildren. We were all sealed to Mom and Dad in the temple.[65]

This experience illustrates some of the unique challenges faced by those wishing to join the Church in Taiwan. For example, the culture in Taiwan included honoring parents and showing respect for ancestors. President Nielson made adaptations to the missionary lessons to address cultural and local needs. For example, We Are Waiting became the first in a series of filmstrips developed by the Taiwan Taipei Mission under Nielson to help investigators with a Buddhist background learn and understand the value the LDS Church and its members placed on families, the need to search after one’s ancestors, and the essential role of temple ordinances for the salvation of one’s ancestors. [66]

Yang Tsung-ting (楊宗廷), who grew up in a Buddhist home before he was baptized in 1973,[67] explained that “most Taiwanese parents expect that when they die, their children will burn paper money and incense for them and offer food. Otherwise, they fear they will be hungry and poor in the next life. That is why older people sometimes panic when they see their young people join the Church.” Yang continues by noting an adaptation which helps minimize the fear from the elderly as follows, “Church members emphasize ancestors but in a different way. . . . We do family history work, submit names to the temple, and perform ordinances for their eternal benefit.”[68]

A 1975 Friend article noted that “one reason the gospel has been so well accepted in Taiwan and other Asian countries is because of the Church’s emphasis on genealogy work. Great honor and respect [is] given to ancestors in these countries.”[69] Brother Chang Cheng Hsiang (張鉦祥) shared the following in the Taiwan Taipei Mission’s monthly publication:

Chinese society is based on the family, the nation, and the culture. . . . Another interesting thing to note is that the customs of the Chinese people are much the same as those of ancient Israel. Many Chinese agree with the plan of salvation and existence of God as they hear the gospel from the missionaries for the first time. They also respect their fathers and worship them. They build ancestral halls and make family genealogies. Because of China’s excellent belief in genealogy, I have been able to trace my family history about 4,000 years back![70]

The adaption to the missionary lessons benefited the Church in Taiwan, and by 1975 there were about seven thousand members in thirty branches, with two hundred full-time missionaries serving in Taiwan.[71] There are various examples of how the missionary efforts in the 1970s would bless the growth and development of the Church in Taiwan, both in the immediate as well as distant future. However, growth was not without its challenges, as illustrated in the experience of Wang Ti’en-te and the Ke Liao Branch: “Wang Ti’en-te founded an independent Christian congregation. . . . With the help of his followers, Wang built a little church there and had a membership of about 250 in 1973. . . . For quite some time, Wang showed little interest in Mormonism, . . . [but] his attitude towards the Church changed suddenly. . . . In April 1973, over 100 members of Wang’s little church were baptized.”[72]

A report in the August 1975 Ensign suggested a promising beginning, but it turned into a sad ending when the truth about Wang surfaced. After being baptized, Wang told his followers that “For 18 years . . . you have followed me; you have trusted me as your shepherd these many years. I invited you to follow me to the waters of baptism today.”[73] It was reported that fifty of his followers joined the LDS Church the same day. Wang was called as the branch president of the Ke Liao Branch, and the Church paid $55,000 to Wang for his chapel. However, most of the branch members spoke only Taiwanese and their ability to understand the teachings of missionaries (which occurred in large groups) was limited. It was later discovered that Wang had deceived the missionaries. Wang’s church had financial problems in early 1973, so he and many of his followers decided to join the LDS Church to gain financial help from the American missionaries. Wang took the money, a lawsuit against the Church was filed by Wang’s followers, Wang fled the country in 1976, many of those baptized left the Church, and the Ke Liao Branch was dissolved after the Church settled the legal dispute.[74] While this sad tale does not represent missionary efforts during this period, it is a reminder of the importance of individual conversion rather than group baptisms.

By contrast, there were many examples of faithful new converts during this period who helped to further the cause of Zion. For example, Wang Wei (王偉) was converted in 1973, and twenty years later he and his wife, Wang Tan Hsiao-Feng (王譚筱鳳), would serve as the first Chinese temple president and matron from 1993 to 1997.[75] Wang regularly taught the importance of searching out one’s ancestors and then bringing those names to the temple to perform the necessary saving ordinances in their behalf. Wang and others like him received both challenges and blessings from accepting the restored gospel. They would have significant impact on the growth and development of the Church in the 1970s and thereafter.

Juan Jui-Chang (阮瑞昌) noted the following in regards to the way the Chinese respect their ancestors and the performance of temple ordinances: “Though I had been attending the temple for more than 13 years at that point . . . , I felt the Spirit more strongly than ever while performing the work for my parents. In the sealing room, I represented my father and my wife represented my mother, and we knelt together at the altar. We felt it was the greatest thing we could do for our parents. . . . We need to help people see that the gospel is not something foreign to Taiwanese culture but something we already know pieces of.”[76]

Publication of the Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price

Another important development in the 1970s was the completion of the first Chinese translation of the Doctrine and Covenants in 1974, followed by the Chinese edition of the Pearl of Great Price in 1976. As with the translation of the Book of Mormon, it was not a smooth experience for those involved. In fact, Lanier Britsch wrote that the “translation of the Doctrine and Covenants into Chinese was an unhappy experience for all concerned.”[77] Part of the challenge stemmed from the differences between the Cantonese and Mandarin dialects used in Hong Kong and Taiwan respectively as well as from personal preferences of mission presidents and various individuals involved with the translation and review process in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the United States.[78]

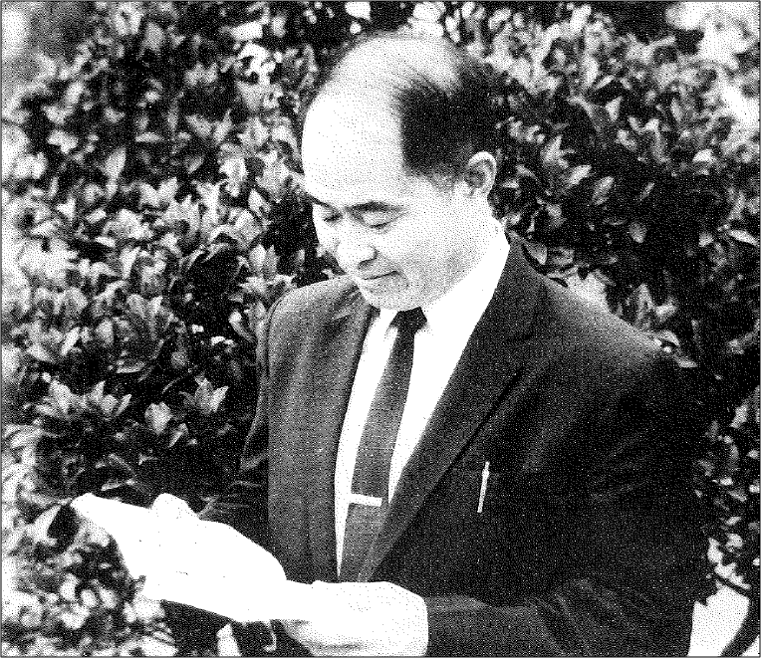

Che Tsai Tien was the principal translator of the Chinese Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price, circa 1974. Courtesy of Richard Stamps and Wendy Jyang.

Che Tsai Tien was the principal translator of the Chinese Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price, circa 1974. Courtesy of Richard Stamps and Wendy Jyang.

In August 1966, President Keith Garner of the Taiwan Taipei Mission had called and set apart Ch’e Tsai Tien (車在田), his counselor in Taiwan, to be the principal translator of the Chinese Doctrine and Covenants and Pearl of Great Price. A former missionary and a student of Chinese literature, Thomas Nielson (later a mission president, as described previously) was in Taiwan working on his doctoral degree and was asked to assist in this work.[79] Their translations were to be sent to Hong Kong for review by Brothers Ng Kat Hing (吳吉慶) (head of translation projects in Hong Kong for almost a decade by this time) and Liu Nga Sang in 1967 or 1968.[80]

The manuscript was being reviewed by multiple individuals and groups independently, which contributed to the project’s difficulties. In 1969, Brother D’Monte W. Coombs from the Church Translation Services Department in Salt Lake created a rather circuitous review process by asking Larry Browning—who was then living in the Washington, DC, area—to review the manuscript of the Doctrine and Covenants translation. Browning’s suggestions would be sent to Coombs in Salt Lake City and forwarded to Hong Kong, which already had another committee conducting a review of the manuscript. The Hong Kong committee had been organized by W. Brent Hardy, president of the Hong Kong–Taiwan Mission, along with two Chinese missionaries and Brothers Ng Kat Hing, Liu Nga Sang, and Wang Leung. In 1971, the mission was divided. President William S. Bradshaw arrived to preside over the Hong Kong Mission, and President Malan R. Jackson became the president of the newly created Taiwan Mission. Although the Hong Kong office retained responsibility for the translation project, new difficulties arose:[81] “The basic difficulty involved in completing a suitable translation grew out of two problems: too much nit-picking and too many personal preferences on the part of mission presidents and other reviewers and basic differences in structural preference between Cantonese and Mandarin speakers. The official version of the Doctrine and Covenants was published by Brother Ng in Hong Kong. However, the Taiwan Mission, under Malan R. Jackson, published its own version.”[82]

Coombs, then manager of the Pacific Area of the Translation Services Department in Salt Lake City, wrote in 1971 to Ng in Hong Kong, then the translation coordinator for the mission. Coombs thought the review was near completion and encouraged Ng to “move rapidly with this matter . . . to publish this material within this year’s budget.”[83] Coombs noted that “all that was required were letters from the Hong Kong and Taiwan mission presidents . . . certifying to the correctness of the translation, along with a letter from Brother Ng recommending the publication.” Coombs was seeking approval letters, not new reviews.[84]

Bradshaw and Ng conducted a review of the revised manuscript in Hong Kong, while Jackson and Ch’e conducted their own review in Taiwan. While both mission presidents and their translators had concerns with the revised manuscript and could not recommend publication of the current manuscript, their reasons were different. Those in Hong Kong had concerns with the revised manuscript but felt it was better than the original, while those in Taiwan felt the original version was better. Distance between Salt Lake and the Far East also contributed to communication problems. Coombs, who had initially pushed to expedite the publication, backed off in 1972 after the mission presidents expressed serious concerns and did not feel good recommending the publication of the revised manuscript.[85]

To reduce the communication problem resulting from distance and from mail communication, Jackson and Ch’e traveled to Hong Kong to work with Bradshaw and Ng in April 1972. Four months later, Bradshaw and Liu traveled to Taiwan to work with Jackson and Ch’e. After many long days, their combined effort provided unity for the translation of the first forty-five sections of the Doctrine and Covenants. President Bradshaw recorded the following:

We began our work at 7:00 and had a one hour break for lunch, a one hour break for dinner, and worked into the evening until 10:00. It was a very rigorous and demanding schedule, but we feel that a great deal was accomplished. President Jackson, Brother Ch’e, Brother Liu, and I worked together in President Jackson’s office. One of the full time lady missionaries acted as our scribe. We found a great deal of changes were necessary in the text of the manuscript. I was continually saddened by the delay that has been created in the publication of the Doctrine and Covenants because Brother Ch’e, the original translator, was never included in approving the review. We found numerous passages which had been changed in the review needlessly, primarily a result of personal opinion and the committee’s decision was to restore the original translation. The original manuscript had to be reviewed, of course, and we found a significant number of passages where neither of the Chinese brethren fully understood the English of the D&C. I developed a strong impression that translation work should include a native speaker and a native English speaker working together. I am also very strongly convinced that the review procedure should not be a retranslation by a second party, but rather a reading of the manuscript wherein the reviewer makes notations about questionable passages even offering alternative translations, but not retranslating the manuscript. It is my belief that the original translator should make the final changes which are suggested.[86]

Requests from both mission presidents to have the first few sections published were not approved by leaders in Salt Lake. Coombs visited Bradshaw in Hong Kong in September 1972, and they had a heated discussion. A year earlier, Coombs had been pushing for the publication, while Bradshaw wanted more time. The roles were then reversed, with Bradshaw pushing and Coombs wanting more time. In their compromise, Coombs authorized Ng to begin the printing process when translation was completed for the first one hundred sections. The review process between Hong Kong and Taiwan continued, but disagreement on the translation between Ng and Ch’e delayed the process.[87]

After visiting Bradshaw again in October 1973 to discuss how to address stalemates between translators in Hong Kong and Taiwan, Coombs sent a memo entitled “Division of Responsibilities between Hong Kong and Taiwan Distribution Centers.” In this memo, Coombs made the Taiwan Distribution Center independent of the one in Hong Kong and instructed Ch’e to review and publish the manuscript before sending it to Ng to do his review. Yet he noted that the printing of the Doctrine and Covenants already under way would proceed under the direction of Ng. Coombs also noted that the Translation Services Department should call, organize, and chair translation committees, not the mission presidents.[88] A Church News article noted that Elders Alfred Sheng Liu and David Bailey would also assist in the review of the translation of the Doctrine and Covenants.[89]

A month or two following the memo, Ng was surprised to learn that Taiwan was printing its edition of the Doctrine and Covenants, with numerous significant textual differences from the Hong Kong version.[90] In many cases, Ch’e used wording from his original version, found in his “green book” copy, instead of the version agreed to between Hong Kong and Taiwan.[91] The Taiwan edition came in April 1974, and the Hong Kong edition came about a month later in June 1974. The former had a dark blue paperback cover, and the latter had a light blue hardbound cover. Both versions had five thousand copies printed.

The complexity of producing a Chinese translation of the Book of Mormon in 1965 was magnified during the translation of both the Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price. There were challenges due to the preferences of multiple reviewers and the need to address the structural language differences between Cantonese and Mandarin. Diane Browning noted, “The great genius of the Chinese writing system, which has served to unify that nation for three thousand years, seems on the verge of being frustrated by competing versions of the same material by the Hong Kong and Taiwan translation offices.”[92] Since the publication of the Doctrine and Covenants, other translations—such as missionary discussions, the temple ceremony, and most recently, the names of the General Authorities—have been translated differently, and these differences are not mere dialectical variants.

Although there were differences between the editions published by Brother Ng in Hong Kong and President Jackson in Taiwan, the translation of the Doctrine and Covenants into Chinese was an important achievement. The Chinese translation of the Doctrine and Covenants was officially published in 1974.[93] There were similar challenges in bringing forth the Chinese translation of the Pearl of Great Price, published in April 1976.

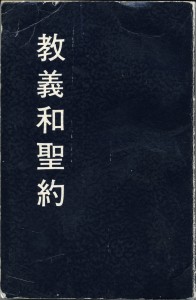

First Chinese Doctrine and Covenants, published in 1974. Courtesy of Tyler Thorstead.

First Chinese Doctrine and Covenants, published in 1974. Courtesy of Tyler Thorstead.

Back in 1966, Garner had called and set apart Ch’e to translate both the Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price. Following the publication of the Doctrine and Covenants, focus was turned to the completion of the Pearl of Great Price. Britsch recorded the following about the experience:

The translation of the Pearl of Great Price did not go smoothly either. First, it is evident that Translation Services personnel in Asia did not expect careful, meticulous analysis of the style of Brother Che’s translation when they sent it to Salt Lake City for approval. They thought they had a satisfactory translation and wanted more or less unquestioning approval by the review committee. Second, even though the review committee suggested content and stylistic changes in almost every verse, when the Chinese version was printed, almost none of the reviewers’ suggestions were incorporated into the printed text. Nevertheless, the Chinese version of the Pearl of Great Price was published in Taiwan in April 1976.[94]

Twenty years after the first four missionaries arrived in Taiwan, the Chinese translation of all Latter-day Saint scripture was finally completed. This allowed missionaries to use these new scriptures in proclaiming the gospel and assisted members in deepening their doctrinal knowledge and understanding of the restored gospel. The translated scriptures were welcomed by the Saints, for whom their full impact cannot be adequately measured or appropriately quantified.

Other Versions, Formats, and Editions

Additional versions, formats, and editions would follow throughout the years to clarify the wording or to improve the translation in some cases.[95] Some corrections and changes have been made following 1965, when Chinese Book of Mormon was first published. Robert J. Morris noted the following in his 1970 article regarding the Chinese translation of the Book of Mormon: “The Book of Mormon was first issued in Hong Kong in January 1966, and each succeeding edition has seen many corrections in wording and concept, ‘clarifying the wordings in some instances,’ as translator Hu Wei-I told me in an interview. He calls them purely translation changes, not doctrine changes.”[96]

In June 1977, the first Chinese triple combination would appear with limited circulation. There were two thousand copies printed for this triple combination, and the hard cover included characters written across rather than the traditional flow of Chinese characters, which are up and down. This version incorporated all three LDS scriptures into one book, including the 1970, or sixth edition, of the Chinese Book of Mormon; the 1974 Doctrine and Covenants version published in Taiwan; and the 1976 Pearl of Great Price translation. Other editions of the triple combination followed in 1978, 1979, 1980, and 1981. Also in 1981, there were some printed copies of the Doctrine and Covenants with the Pearl of Great Price. This edition, published from 1981 through 1985, did not incorporate the Book of Mormon but included the new sections of the Doctrine and Covenants added in the new edition of the English scriptures.[97] Thereafter, a Chinese triple combination was published in 1982.[98]

Chinese triple combination, 1982. Courtesy of Tyler Thorstead.

Chinese triple combination, 1982. Courtesy of Tyler Thorstead.

Under the direction of the Church’s Presiding Bishopric, a committee was organized in March 1979 with five committee members, including H. Grant Heaton, who was the first president of the Southern Far East Mission. Their task was to conduct a confidential, critical evaluation of the Chinese Book of Mormon translation. However, the Translation Services Department terminated the project shortly after Heaton sent a fifty-page critique of the translation by Heaton’s committee.[99] The reason for disbanding this committee was unclear, but it was in 1979 and 1981 that the new edition of the LDS scriptures were published in English.

In 1979, twenty thousand copies of the Chinese Book of Mormon were printed for this seventh edition. This edition was the last hardbound edition, with all later editions coming in a paperback format. The eighth edition came in November 1980, and the ninth edition in July 1982, with thirty thousand and ten thousand copies respectively. All editions were printed in Hong Kong until 1981, when Taiwan printed it for the first time. The ninth edition of the Chinese Book of Mormon, printed in 1982, was the last printing with the angel Moroni on the cover as well as the last to be a numbered edition.[100]

Another significant change also occurred in 1982, when the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles approved the subtitle “Another Testament of Jesus Christ” in the English edition of the Book of Mormon.[101] Thereafter, all new editions of the Book of Mormon in the various languages throughout the world, including the Chinese edition, began to carry this subtitle as well as the newly added sections of the Doctrine and Covenants. From 1983 forward, all editions of the Chinese Book of Mormon would be the traditional dark blue cover with the subtitle. In addition, colored pictures by Arnold Friberg replaced the old Latin America pictures, and the title and subtitle words were written horizontally, similar to all other language editions, rather than the vertical format typical to Chinese writing.[102] Feng Xi reported the following: “As time went on, the Translation Services Department too realized the urgent need for a revision of the Chinese version of the Book of Mormon over the past few years. It organized a group of translators to work on a new version. By 1992, the new version of the Book of Mormon had been completed and a confidential evaluation of the translation was under way.”[103]

Conclusion

The early missionary efforts during the 1950s and 1960s were important in laying a foundation for the expansion of the Church in Taiwan. However, there were significant events in the 1970s that helped to cement a firm foundation for the work of salvation to expand in the island. While Taiwan lost diplomatic recognition from the United Nations, and while other Christian religions, like the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan, would struggle with the Taiwanese government, the LDS Church was able to expand and support the Saints in Taiwan.

Major Church historical events in Taiwan in the 1970s helped to expand missionary efforts as well as develop and prepare local leadership in Taiwan. The first event was the creation of the Taiwan Mission (later renamed the Taiwan Taipei Mission) in 1971, which provided a mission president living by and working directly with the members and local leaders in Taiwan. The next milestone was the establishment of CES programs, which helped to strengthen the testimony of members and increase their gospel scholarship. Third, there were changes in the missionary program, which included organizational changes, as well as adaptation of the missionary lessons based on local needs, resulting in increased convert baptisms (including the baptism of future leaders of the Church). Finally, there was the completion of the Chinese translation of the Doctrine and Covenants and Pearl of Great Price, providing all modern scriptures to the Chinese members.

Notes

[1] A version of this section appears in print in Chou Po Nien (Felipe), “History of the Church in Taiwan in the 1970s,” in The Worldwide Church: The Global Reach of Mormonism, ed. Mike Goodman and Mauro Properzi (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2016), 121–42; Britsch, From the East, 259.

[2] “Programs and Policies Newsletter: Taiwan Mission,” Ensign, February 1971, 76.

[3] Britsch, From the East, 259.

[4] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 117.

[5] “Taiwan Saints Eager for Temple Blessings,” Ensign, November 1984, 107–9; Elder Komatsu would later become the first General Authority of Asian descent.

[6] Britsch, From the East, 254.

[7] Britsch, From the East, 254.

[8] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 172–75.

[9] Paul Hyer, “Taiwan,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, and Richard O. Cowan (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 1216–17.

[10] Wang Li-Ching (Sandy Lee), phone interview by Chou Po Nien (Felipe), 18 November 2013.

[11] Paul Hyer, “Taiwan,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 1216–17.

[12] Murray A. Rubinstein, “Taiwanese Protestantism in Time and Space, 1865–1988,” in Taiwan: Economy, Society and History, ed. E. K. Y. Chen, Jack F. Williams, Joseph Wong (Hong Kong: Centre of Asian Studies, 1991); William Heaton, “China and the Restored Church,” Ensign, August 1972, 14–18.

[13] Ng Shee-Nan and Chin Ching-Man, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: History in Hong Kong, 1949–1997, trans. Anita Chin (Hong Kong: Printforce Printing, 1997).

[14] Britsch, From the East, 254.

[15] Christine L. Lin, “The Presbyterian Church in Taiwan and the Advocacy of Local Autonomy,” Sino-Platonic Papers (January 1999).

[16] Feng Xi, “Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 176–77.

[17] Harry Harding, A Fragile Relationship: The United States and China Since 1972 (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 1992); William Heaton, “China and the Restored Church,” Ensign, August 1972, 14–18.

[18] William Heaton, “China and the Restored Church,” 14–18.

[19] “New Supervisory Program for Missions and Regions,” Ensign, September 1972, 87–89.

[20] “New Supervisory Program for Missions and Regions,” 87–89.

[21] “New Supervisory Program for Missions and Regions,” 87–89.

[22] James O. Mason, “The History of the Welfare Service Missionary Program”

(address at the Missionary Training Center, Provo, UT, 12 August 1979); “Church’s Health Team Teaches Maternal Care,” Church News, 3 March 1979, 13.

[23] Margaret R. J. Kitterman, interview by Richard L. Jensen, Salt Lake City, May–September 1975, Historical Department (1972–2000), History Division (1972–80). Note: Margaret Kitterman’s maiden name is Jensen.

[24] “Church’s Health Team Teaches Maternal Care,” 13.

[25] Margaret R. J. Kitterman to Chou Po Nien (Felipe), email, 29 April 2016.

[26] Kitterman, interview by Jensen.

[27] Chen Lin Mei-Yu (Rebecca), interview by Chou Po Nien (Felipe), 7 November 2015, Murray, UT.

[28] “Keeping Pace with Church Programs and Emphases: The International Look of Health Services Missionaries,” Ensign, March 1975, 70–71.

[29] In the case of English-speaking expatriates, they could have used the English materials.

[30] Stamps and Shamo, The Taiwan Saints, 105.

[31] Seminaries and Institutes of Religion Annual Report for 2013 (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2013).

[32] Britsch, From the East, 272–73.

[33] Chou, “History of the Church in Taiwan in the 1970s,” 121–42.

[34] Alan Hassell, interview by Dale LeBaron, 17 May 1991, Medford, OR, copy in possession of the authors.

[35] Alan and Michele Hassell, unpublished Christmas 1974 letter, copy in possession of the authors.

[36] Wang Li-Ching (Sandy Lee), phone interview by Chou.

[37] Alan Hassell, unpublished personal history of work in Seminaries and Institute, copy in possession of the authors.

[38] Hassell, interview by LeBaron.

[39] Hassell, unpublished personal history of work in Seminaries and Institute.

[40] Alan and Michele Hassell, unpublished Christmas 1974 letter, copy in possession of the authors.

[41] Hassell, unpublished personal history of work in Seminaries and Institutes.

[42] Hassell, interview by LeBaron.

[43] While official seminary and institute records are not available for this time period, an overview entitled “The Early Development of Church Education in Hong Kong and Taiwan” lists these numbers: http://

[44] Hassell, interview by LeBaron.

[45] John Hilton III and Chou Po Nien (Felipe), “The History of LDS Seminaries and Institutes in Taiwan,” Mormon Historical Studies 14, no. 2 (Fall 2013): 83–106.

[46] Hassell, interview by LeBaron.

[47] Hassell, interview by LeBaron.

[48] Hassell, interview by LeBaron.

[49] Hilton and Chou, “The History of LDS Seminaries and Institutes in Taiwan,” 83–106.

[50] Hilton and Chou, “The History of LDS Seminaries and Institutes in Taiwan,” 83–106.

[51] Juan Jui-Chang, interview by the Family and Church History Department, 20 October 2001.

[52] Christopher K. Bigelow, “Taiwan: Four Decades of Faith,” Liahona, May 1999, 29.

[53] Chou Po Nien (Felipe), personal history and journal entries, 2000–2005.

[54] Ng and Chin, History in Hong Kong, 95.

[55] Kuo Hung Chou served as the coordinator in Kaohsiung from 1985 to 1994; Hilton and Chou, “The History of LDS Seminaries and Institutes in Taiwan,” 83–106.

[56] Ng and Chin, Church of Jesus Christ of LDS: History in Hong Kong, 93.

[57] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 177.

[58] Britsch, From the East, 265.

[59] Britsch, From the East, 265.

[60] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 177.

[61] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 118.

[62] Wang Li-Ching (Sandy Lee), “My Conversion Story” (unpublished personal history, copy in possession of the authors).

[63] Wang, “My Conversion Story.”

[64] Wang, “My Conversion Story.”

[65] Wang, “My Conversion Story.”

[66] Taiwan Taipei Mission Historical Reports, 31 March 1976, Church History Library.

[67] Stamps and Shamo, The Taiwan Saints, 23–25.

[68] Bigelow, “Taiwan: Four Decades of Faith,” 29.

[69] “Friends in Taiwan,” Friend, November 1975, 13.

[70] Janice Clark, “Taiwan: Steep Peaks and Towering Faith,” Ensign, August 1975, 55–58.

[71] “Country Information: Taiwan,” Church News, 1 February 2010, http://

[72] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 179–83.

[73] Clark, “Taiwan: Steep Peaks and Towering Faith,” 55–58.

[74] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 179–83.

[75] Britsch, From the East, 294.

[76] Bigelow, “Taiwan: Four Decades of Faith,” 29.

[77] A version of this section appears in print in Chou Po Nien (Felipe), Petra Chou, and Tyler Thorstead, “The Chinese Scriptures,” Mormon Historical Studies 17 nos. 1–2; (Spring/

[78] Ng and Chin, Church of Jesus Christ of LDS: History in Hong Kong.

[79] Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese,” 21–22.

[80] Britsch, From the East, 266–72.

[81] Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese,” 12–14.

[82] Britsch, From the East, 266–72.

[83] Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese,” 14.

[84] Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese,” 15.

[85] Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese,” 15.

[86] Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese,” 19.

[87] Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese,” 17–19.

[88] Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese,” 19–20.

[89] “Scripture for 800 Million,” Church News, 10 July 1971, 12.

[90] Tyler Thorsted, interview by Chou Po Nien (Felipe), 2 April 2015, Salt Lake City.

[91] Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese,” 21–22.

[92] Browning, “The Translation of Mormon Scriptures into Chinese,” 22.

[93] Bigelow, “Taiwan: Four Decades of Faith,” 38–46.

[94] Britsch, From the East, 268.

[95] Joseph G. Stringham, “The Bible: Only 4,263 Languages to Go,” Ensign, January 1990, 17–21.

[96] Robert J. Morris, “Some Problems of Translating Mormon Thought into Chinese,” BYU Studies 10, no. 2 (Winter 1970): 173–85.

[97] Thorsted, interview by Chou.

[98] Rappleye, “Chinese Translation of the Book of Mormon.”

[99] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 102.

[100] Thorsted, interview by Chou; 1979 Chinese Book of Mormon (July edition); 1980 Chinese Book of Mormon (November edition); 1981 Chinese Book of Mormon (November edition); 1982 Chinese Book of Mormon (July edition), from http://

[101] Boyd K. Packer, “Scriptures,” Ensign, November 1982, 51–53.

[102] Thorsted, interview by Chou; 1983 Chinese Book of Mormon, from http://

[103] Feng Xi, “A History of Mormon-Chinese Relations,” 102.