St. Georg Branch

Roger P. Minert, “ St. Georg Branch, Hamburg District,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 162–85.

As the largest of three branches in the largest city in the West German Mission, the St. Georg Branch was located in the heart of Hamburg—a city of 1.7 million people. With 413 members in 1939, the St. Georg Branch had the largest population in the mission, followed by Nuremberg. It had an outstanding number of elders (thirty-nine) and fifty-four more men and boys who held the Aaronic Priesthood. This was indeed a very strong branch in which nearly all programs of the Church were running at high efficiency when the war broke out.

The location of the meeting rooms was fortunate—just a few short blocks from the main railway station and the city hall. Branch historian Hans Gürtler described the rooms at Besenbinderhof 13a in these words:

How happy we were when the Redding Printing Co. rented us some rooms on the main floor that was not only much larger [than our previous venue] but also isolated and offered us total peace and quiet. . . . The date was January 30, 1910. This would be our location for thirty-five [thirty-three] years. . . . Just before the war we were able to rent small rooms above and next to the main hall. A foyer with a cloak room was added. The crown jewel was the kitchen that was built in the basement.” [1]

The entry to the rooms in building 13a was from the street called Besenbinderhof. The Saints went through a portal in the main building, then into an alley and down the so-called Hexenberg (Witch’s Mountain) perhaps one hundred feet to the door of the building. The setting outside could not have resembled a traditional German church in any way.

Hertha Schönrock (born 1923) recalled a sign that indicated the presence of the branch in that building and that a baptismal font was constructed on top of the stage in 1940. “It was very rare and we were blessed to have one.” [2] Ingo Zander (born 1934), a son of the branch president, was baptized in that font in 1942. [3] The Zander family lived in the suburb of Hamm and needed a good half-hour to get to church with the streetcar and on foot (a trip the family made twice each Sunday). Hertha Schönrock was impressed by the emphasis on reverence in the meetings. “If we came late, they wouldn’t let us in. The doors were closed to promote reverence.”

| St. Georg Branch [4] | 1939 |

| Elders | 39 |

| Priests | 13 |

| Teachers | 13 |

| Deacons | 28 |

| Other Adult Males | 54 |

| Adult Females | 214 |

| Male Children | 28 |

| Female Children | 24 |

| Total | 413 |

The branch presidency in 1939 consisted of Arthur Zander, Franz Jakobi, and Walter Benkowski. Erich Gellersen was the supervisor of the Sunday School; Erich Leiss, the leader of the young men; Paula Schnibbe, the leader of the young women; and Anna Ruthwill, the leader of the Relief Society. The branch directory of August 1939 does not list a leader of the Primary organization (or a meeting time for that matter), even though there were fifty-two children in the branch at the time. [5] Eyewitnesses estimated the average attendance at one hundred to one hundred and fifty persons on a typical Sunday (perhaps one-third of the registered members).

Sunday School began at 10 a.m. and sacrament meeting at 7 p.m. The Relief Society and priesthood groups met on Monday evenings at 7:30 and the Mutual on Wednesdays at the same time. The meeting schedule likewise includes times for a genealogy class and rehearsals for the branch choir and the branch orchestra. Special entertainment was scheduled for a Friday “at least once each month,” according to the branch directory of 1939. [6]

Living in the suburb of Wilhelmsburg (across the Elbe River to the south), the Schönrock family had a distance of about four miles to negotiate four times each Sunday if they were to attend all of the meetings of the St. Georg Branch. According to daughter Hertha, “It looked like geese were marching in a line when our entire family was on the way to church. Sometimes it was too expensive for all of us to take the train or the bus to church. When we were older, we spent the time between meetings in the homes of friends.”

Hertha enjoyed her experience as a member of the League of German Girls, but she was not an admirer of Adolf Hitler. “I saw him once with my League group when he came to Hamburg, but I never considered him anyone special.” Hertha’s father, Wilhelm Schönrock, was a communist who sometimes went to a neighbor’s apartment to listen to BBC broadcasts. As an electrician, he had worked on the new battleship Bismarck and had even participated in the maiden voyage of that famous vessel.

“My life changed drastically in 1938 with the Night of Broken Glass,” recalled Karl-Heinz Schnibbe (born 1924). “All of the Jewish businesses were destroyed. I was very angry and decided to leave the Hitler Youth.” [7] Soon thereafter, he was called into the Nazi Party headquarters in Hamburg and accused of being a communist (his father was actually a Social Democrat, almost as bad as a communist in the opinion of the Nazis). Karl-Heinz was relieved to be informed that the Hitler Youth no longer had room for him.

Several eyewitnesses recall seeing police officials sitting on the back row during meetings. “We knew who they were,” claimed Erwin Frank (born 1923). The men never said anything and never interrupted or tried to cancel the meetings. The Mormon Church apparently meant little to the city government at the time. In general, the neighbors of LDS families in Hamburg also knew little about their Church activities. Erwin’s parents had eight children and were interested only in the Church—not politics. According to Erwin, “Back then the big thing was the Nazis and the communists and neither party appealed to us.” [8]

Fig. 1. The main meeting room at Besenbinderhof 13a was probably the largest used by any branch in Germany in 1939. The room accommodated up to five hundred people. The baptismal font was constructed on the rostrum (behind the photographer) in 1940. (I. Gellerson Long)

Fig. 1. The main meeting room at Besenbinderhof 13a was probably the largest used by any branch in Germany in 1939. The room accommodated up to five hundred people. The baptismal font was constructed on the rostrum (behind the photographer) in 1940. (I. Gellerson Long)

“Both of my parents had been out of work,” recalled Gerd Fricke (born 1923), “but Hitler turned things around. When my parents found work, they supported him at first.” Gerd’s father was not active in the Church, but the fact that he joined the SA (the party’s organization for men) did not mean that he belonged to the Nazi Party, according to Gerd. During the first years of the war, Gerd worked in a factory where parts for submarines were produced. “Back then, we teenagers still found ways to have fun. We were involved in sports and other entertainment. It wasn’t all deadly serious.” [9]

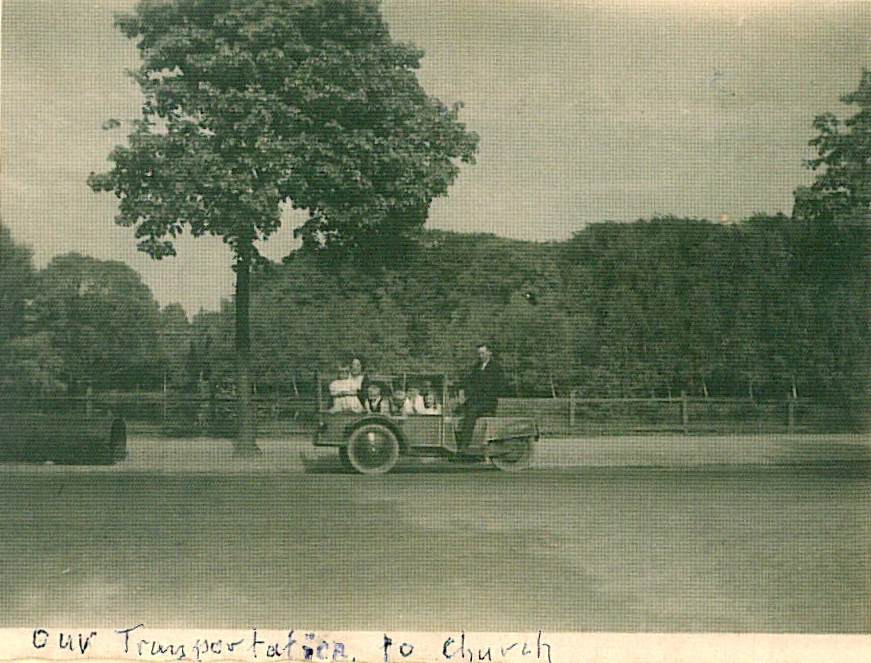

Fig. 2. Richard Pruess drove several members of his family to church in this three-wheeled vehicle. (H. Pruess Mueller)

Fig. 2. Richard Pruess drove several members of his family to church in this three-wheeled vehicle. (H. Pruess Mueller)

Just before the war, the family of Richard and Rosalie Pruess of Rahlstedt owned a three-wheeled automobile. According to daughter Lieselotte (born 1926), her father drove as many as six of the family members to church in that vehicle. Rahlstedt is a northeast suburb of Hamburg and fully seven miles from the branch rooms at Besenbinderhof. As a Primary girl, Lieselotte had actually made the trip alone on the bus and the streetcar many times in the mid-1930s. “When I was eight and nine, I took my little sisters too because they begged to go.” [10]

Richard Pruess was anything but a Nazi and refused to use the standard greeting of “Heil Hitler!” Nor was he ashamed to receive a Jewish guest in his home. Salomon Schwartz, a member of the Barmbek Branch, visited the Pruess family on occasion—in fact, often enough that the neighbors were aware of him. It was possibly the general respect for Brother Pruess that prevented neighbors (some of whom were “good Nazis”) from reporting him to the police for entertaining a Jew in his home. In Lieselotte’s recollection, her father removed the Juden verboten sign from the church on one occasion; he was accustomed to saying that those who persecute Jews will be punished.

Otto Berndt (born 1929) was inducted into the Jungvolk just months before the war began. As he recalled:

I liked the Hitler Youth because I had the opportunity to go places which I would have never had. We learned the Hitler way and had meetings every week. It actually was indoctrination of the highest order but we were all too dumb to realize what was being done with the youth. After school, we had to assemble and sing the German national anthem and the Horst Wessel song. We did a lot of marching and singing in formation. [11]

The outbreak of war was not much of a surprise to Erwin Frank and his family. “It got to the point that Hitler didn’t seem to be satisfied with what he had. As soon as he marched into one country, he was ready for the next.” Erwin’s prime concern in the fall of 1939 was not the war; he was only sixteen and had begun his apprenticeship as a galvanizing specialist. He needed four years to prepare for his examination, but his program was interrupted in 1940 by a call to the Reichsarbeitsdienst.

The war began when Karl-Heinz Schnibbe was a young apprentice. He recalled his reaction to the news:

We heard that Germany had attacked Poland; it was announced over the radio as “special news.” I was young and didn’t give the matter much thought. When the war started, nobody believed that Germany could lose. I thought that Germany could do anything she wanted because the country was strong and Hitler was a strong personality. Poland was conquered in two and a half weeks, which was unbelievable. I must say though that the older people were worried.

The announcement of the war against Poland also appeared in all German newspapers. Karl Schönrock (born 1929) recalled reading about it as he delivered his newspapers one day:

We delivered our papers in the afternoon after school (my sister and my brother also had paper routes). . . . I had thirty or forty people to deliver newspapers to. I wasn’t scared that Germany was going to war. I felt it was somewhat justified because of an announcement that some Polish troops had attacked the radio station in the [German] city of Gleiwitz. Later on, of course, after the war, they said those were German [criminals] disguised as Polish soldiers. [12]

Werner Schönrock (born 1927) was in the Jungvolk when the war began. As he recalled:

I was a member of the Jungvolk as well as the Hitler Youth later on and I liked going there. In my free time, I liked being involved in sports, especially gymnastics and handball. Because the sports field was right next to our home, we were able to do so much there. We were still able to do all those things during the war though the circumstances got more hazardous. [13]

Werner’s athletic field took on a different role as the air raids over Hamburg became more frequent: antiaircraft batteries were set up there, and eventually two bunkers for civilians were erected.

Ingeborg Thymian (born 1930) was baptized in the Elbe River on March 16, 1940. She had wanted to be baptized at the age of eight (two years earlier), but there was a problem. As she recalled, “Because I had braided my hair that day, it was always floating on the water. After the third unsuccessful attempt, they told me that they had to baptize me at another date.” The successful baptism was conducted despite a different obstacle—ice in the Elbe. A hole was cut in the ice, and Ingeborg was baptized. “We, as children, were always scared that somebody would get sick in the cold water, but Heavenly Father protected us.” [14]

The Kinderlandverschickung (children’s rural evacuation program) took Astrid Koch (born 1932) away from her family in Hamburg when she was only eight years old. She shared the following recollections:

When we got to Pulsnitz [in Saxony], there was a big hall in a school and they had something for us to eat. People who wanted to take children in came there and picked out the children. I didn’t know where I was going. [The people who chose me] were the Hardtmanns; they thought it might be interesting to raise a young child, so they decided on doing that. My twin sisters were also in that town; they were four years older, they were twelve. They went to a different family. My people were very nice, and the people that owned that house [the Erichs] had a daughter my age. [15]

Walter and Gertrud Menssen had married just before the war and were parents by January 1939. Walter (born 1913) was drafted just months after the war began. Gertrud (born 1919) was fortunate to find a nice apartment in his absence. It was there that their second child, a daughter named Edeltraut, was born in May 1941. Because Walter had always wanted a garden, Gertrud found and leased a plot of land measuring sixty by ninety feet in the Hamburg suburb of Horn. They constructed a one-room cottage on the property and spent most of June and July of 1941 there, despite the rain that fell nearly every day that summer. Little did they know that this would become their principal residence in a few years. [16]

Walter Menssen had spent several months in the army in early 1939 and was called in again at the end of that year. When the war began, the Luftwaffe needed men to serve in units all over Europe. Brother Menssen lead a charmed life as a soldier, beginning with an assignment just a few miles from his home. He was soon working in the comfort of an office while he watched thousands of air force men be assigned to faraway stations. His health was excellent, with the exception of a short stay in the infirmary. This may have been the reason that he was given the classification of “conditionally fit for duty,” which meant that he would not be assigned to locations beyond the borders of Germany. [17]

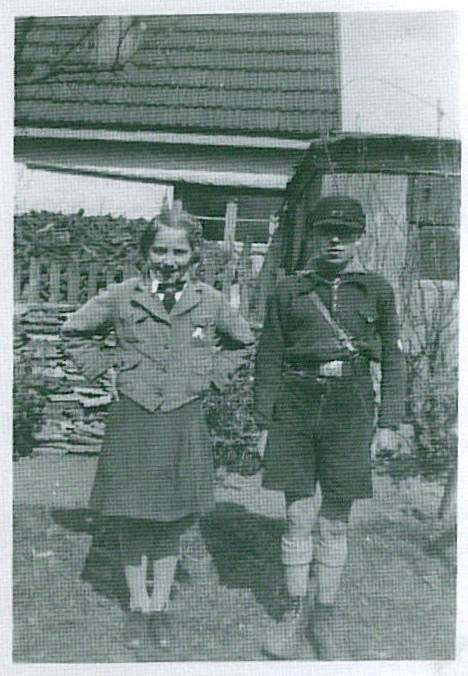

Fig. 3. Lieselotte and Richard Pruess in the uniforms of the League of German Girls and Hitler Youth respectively in about 1941. (H. Pruess Mueller)

Fig. 3. Lieselotte and Richard Pruess in the uniforms of the League of German Girls and Hitler Youth respectively in about 1941. (H. Pruess Mueller)

Werner Schönrock finished his public schooling in 1940 and hoped to join the war effort as a navy man. To his disappointment, he was too small. “They sent me home and told me that I should eat more.” A few months later, he reported again and was sent for aquatic training that would render him more fit for duty. This time he became ill, however, and was hospitalized for three months with tuberculosis. It seemed that he was not to serve in Hitler’s military.

Like hundreds of other LDS men of the West German Mission, Hans Gürtler (born 1901) hoped against hope that he would not be drafted. Already a husband and father of four, he received his call to the Wehrmacht in March 1941. He was first stationed in Harburg, a southern suburb of Hamburg; but in late 1941, he was sent to central Germany for additional training. A man of letters, he was quite opposed to Hitler’s regime and expressed this in private by arranging with a comrade to change the wording of the soldier’s oath: “Otto Schmidt and I had promised each other that we would not repeat the [words of the] oath correctly, but rather to pronounce a curse on Adolf Hitler, which we then did. Of course, our pious wish went unheard among the loud voices around us, which we wished would happen. After all, we didn’t want to cut our own throats.” His career as a soldier began most peacefully. For example, during a stay in the Polish city of Posen, he was able to attend a theater play three times in ten days. [18]

Therese Gürtler (born 1929) recalled how her father, Hans, was always writing poems. As an opponent of the Hitler regime, he even wrote poems against the state and the war. Therese and her siblings were aware of this but of course never mentioned it outside of the home. She did remember that one man in the branch found out and threatened to report Brother Gürtler to the Gestapo. Apparently the fact that Hans Gürtler was soon drafted satisfied the man, and the anti-Hitler poet was not denounced. [19]

During the many minor air raids of the early war years, Therese Gürtler spent a lot of time with her family and their neighbors in their basement shelter. As she later explained:

We usually would bring some games down with us, and it was always something that didn’t really scare me. But when you heard the sirens before—when the air raid started, when they were warning us—that was a sound that was so eerie and so frightful. That’s really the only thing that I remember being scared of. But for some reason, I was never afraid that we would be bombed, or that we would be hurt, or that we would lose our home. I guess, when you grow up in a family that is living the gospel and believing, there is a feeling of security and safety that is kind of indestructible. You’re taken care of by your parents, and you know you’ll be fine.

Most LDS children in the Jungvolk told of positive experiences, but that was not the case with Werner Sommerfeld (born 1929); to him, the Jungvolk program was anything but entertaining. He provided the following description:

Boys of 12 and 13 were taken for intense military training. I can still remember the camps with the ground covered with gravel, where we had to crawl on our elbows from one side of the compound to the other, while they fired bursts of live ammunition over our heads. Many young boys were crying and calling out for their mothers. Some raised a little too high and were injured or killed. . . . My group became trained in anti-tank warfare. We carried bazookas (Panzerfaust) and balanced them under our arms to aim at oncoming tanks. We were expendable. [20]

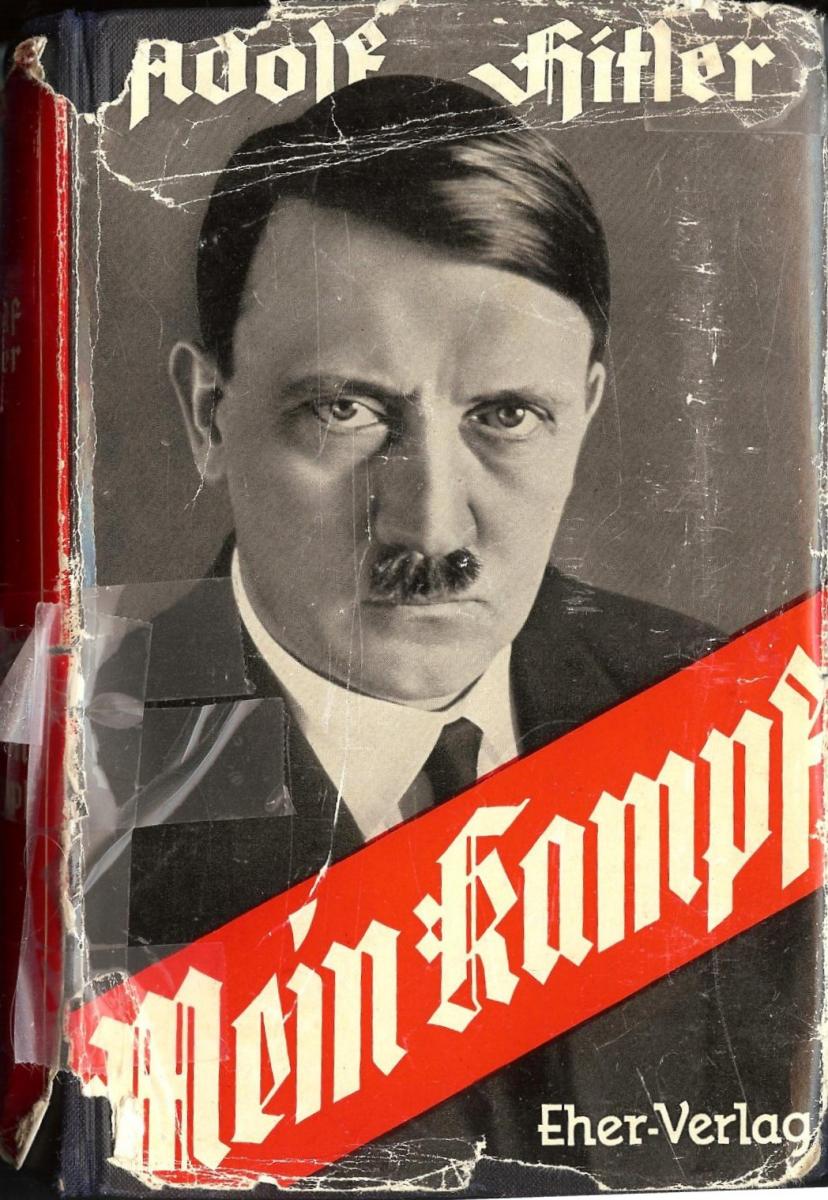

Karl Schönrock recalled his experience in the Jungvolk, where membership was required of boys and girls when they turned ten: “They mostly indoctrinated us and we were encouraged to read Mein Kampf and that was all. As a matter of fact, I still have the book. They didn’t give us a copy; I had to buy it. I was maybe twelve when I bought it, and I actually read it, but I didn’t understand much of it at that age.”

Fig. 4. The economy edition of Adolf Hitler’s book Mein Kampf (My Struggles) was seen on many coffee tables in Germany during the National Socialist era. (K. Schoenrock)

Fig. 4. The economy edition of Adolf Hitler’s book Mein Kampf (My Struggles) was seen on many coffee tables in Germany during the National Socialist era. (K. Schoenrock)

When the air raids over Hamburg became more frequent and intense, the city government required that watchmen be stationed in all larger buildings. Harald Fricke (born 1926) recalled standing guard in the church rooms with his father. Their responsibility was to watch for and report any bomb damage and to fight any fire that might start in the meeting rooms. After each attack, if nothing was out of order at the church, they hurried home to determine the status of their apartment and their family. [21]

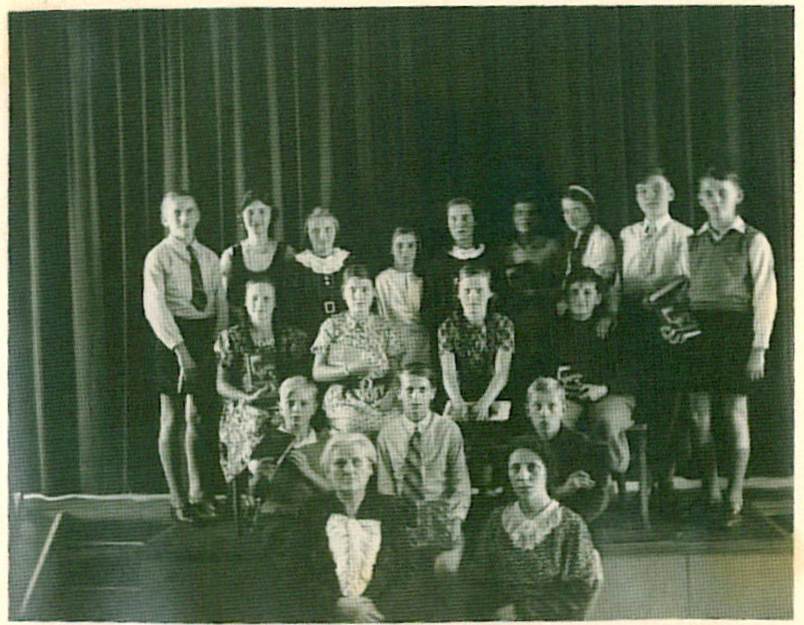

Fig. 5 and 6. Scenes from the St. Georg Branch in happier days. (H. Pruess Mueller)

Fig. 5 and 6. Scenes from the St. Georg Branch in happier days. (H. Pruess Mueller)

Perhaps the most challenged people in Germany during the war were the young mothers who were left to raise their children alone. Such was the condition of Maria Niemann (born 1911) who dearly missed her husband, Henri, while he served on the Eastern Front for four years. With her young son, Henry (born 1936), she did her best to keep order in life. As she recalled:

We cried for [my husband] and always [awaited] a letter that he was still alive and everything was fine. So, for him it wasn’t fine, but I was calmed down and I was happy to hear that he was still alive. . . . He came home for [leave] sometimes and then I was happy to have him for a day and off went his soldier clothes and [on] his private clothes and then I always reminded him . . . that he should take his [identification] papers with him or he would go to jail. [22]

Hertha Schönrock was a spirited young lady who worked in a textile factory. The bombing raids carried out by the British over Hamburg angered her so much “that I was close to enlisting in the army. I sometimes wished I was a boy so that I could do more.” [23] Her sister, Waltraud, worked in a different factory where clothing and gowns were produced.

Johann Schnibbe had been called to be a traveling elder during the early years of the war. He often visited branches in other cities as part of this assignment. Another aspect of his service was visiting four families in the St. Georg Branch. He took his son, Karl-Heinz, along for those visits. As Karl-Heinz recalled, “We either took the streetcar or walked. If nobody was home, my father insisted that we go again the next day and that’s what we did. Nobody had a telephone. We were assigned to visit four families and it took about three hours to visit them all.”

Like most of the Saints in the West German Mission in the early years of the war, the Richard Pruess family of Rahlstedt sat in the basement of their home while the air-raid sirens wailed and the bombs fell; the public shelter was too far away from their home. According to little Hilde (born 1934), the basement had been reinforced by large wood beams and concrete blocks were stacked outside in front of the basement window. [24]

The government program of evacuating school children from cities under attack took Hilde away from her family several times for a total of nearly two years. She spent more than one year in the southern German town of Wunschendorf. She was home again for a while, then sent back to Wunschendorf. On another occasion, she was sent to Thorn in eastern Germany where she lived in a school along with refugee families. Thorn was a long way from her family and her church.

In August 1941, Erwin Frank was drafted into the national labor force and stationed in France. It was there that he enjoyed a rare privilege, a get-together with his friend Paul Mücke, another member of the St. Georg Branch. The two spent only one afternoon together before Paul returned to his unit. At the completion of the six-month assignment, Erwin returned to Hamburg to the same message thousands of young men received just days after they completed the Reichsarbeitsdienst tenure: a draft notice. Paul was instructed to report for service in the Luftwaffe. It was January 1942.

Eyewitnesses generally agree that several Latter-day Saints in the St. Georg Branch were also ardent members of the National Socialist Party. According to historian Hans Gürtler:

Essentially all possible political opinions were represented in the branch. It was especially painful that we had National Socialists in our midst—people who idolized Hitler. Despite general caution, we had some disturbances now and then. Even today, we can still recall the negative feelings we had when prayers were said at the pulpit for that Satanic charlatan. Some even dared to put the swastika flag in our hallowed meeting rooms and to use the Hitler salute. On the other hand, it can and should be noted that many of our members only saw the positive aspects of Hitler’s regime and could not see behind the scenes. . . . One humiliating concession to the government was a necessary evil—the exclusion of Jews from our meetings. [25]

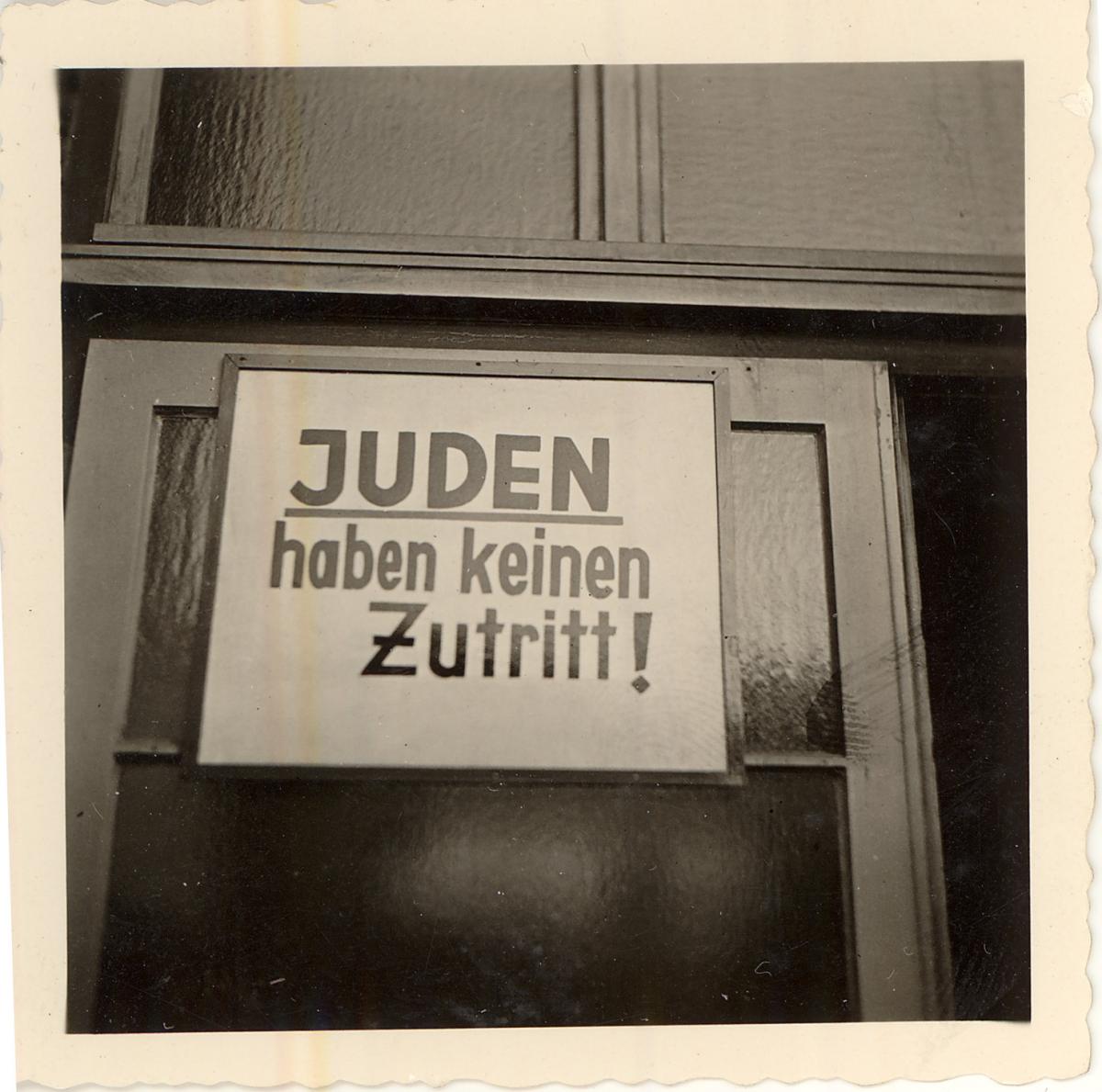

Branch president Arthur Zander was considered by many eyewitnesses a devout National Socialist. Although most claimed that he did not give political speeches in Church meetings, they did recall that he interrupted meetings so that Hitler’s speeches could be played over the radio for the Saints to hear. Indeed the disagreements about politics may have been more distinct in this branch than in any other in the West German Mission. Ingo Zander described his father as “a very dynamic, magnetic person.” [26] Perhaps President Zander was also very decisive, because many eyewitnesses identified him as the man who posted the sign Juden verboten at the front door and denied entry to such members as Salomon Schwarz, a man with an undetermined degree of Jewish blood. (Brother Schwarz was then taken in by the neighboring Barmbek Branch where no such sign was posted.) In contrast, some eyewitnesses suggested that President Zander posted the sign in order to curry favor with the local police authorities; he may have believed that without the sign, the branch would be forced to close down entirely.

Fig. 7. “Jews are not allowed here!” Signs of this variety were posted all over Germany to make life impossible for Jews who had not yet left the country. (G. Blake) [27]

Fig. 7. “Jews are not allowed here!” Signs of this variety were posted all over Germany to make life impossible for Jews who had not yet left the country. (G. Blake) [27]

Like so many children in Germany during the war, young Otto Berndt became an expert on air raids. His recollections are a combination of religious and the practical knowledge:

Whenever we had to go to the bunker because of an air raid, we would all kneel in prayer and ask for protection of what was to come. An air raid would always last two hours. You could set your clock by it. The British bombed during the night and the Americans bombed during the day, so that there wasn’t much time to do much of anything [else]. I don’t remember being comforted by prayer, but now that I’m older and it’s all over with I know that “somebody up there loves me.” [28]

Branch historian Hans Gürtler was quite mild in his comments regarding Helmut Hübener, Karl-Heinz Schnibbe, and Rudi Wobbe, the three teenagers tried and convicted of treason in 1942. [29] He referred to their illegal actions as

the saddest experience in the branch. [These] three younger brethren had listened to foreign radio broadcasts and had copied them using the branch mimeograph machine, then distributed the flyers. It was a serious challenge for the district president [Otto Berndt] to prevent the branch from suffering the worst imaginable punishment. How often the existence of the branch seemed to hang by a thread! [30]

The reactions of the Saints to the arrest and trial of the three Aaronic Priesthood holders who defied the government were mixed and emotional (see their story in the Hamburg District chapter). Karl-Heinz Schnibbe recalled that one older man in the branch told him to his face that “he would have shot me personally if he knew what we had done.” Most eyewitnesses stated that while they felt sorry for the boys when they were punished, the case had placed the three Hamburg branches in serious jeopardy with the police; the boys were foolhardy to undertake any such resistance and the fact that they used church equipment to support their treasonous activities was inexcusable. The membership records show that Helmut Hübener, Karl-Heinz Schnibbe, and Rudi Wobbe were all excommunicated from the Church shortly after their trial in Berlin (an action that was reversed by the Church’s First Presidency a few years later). [31]

After a full year in Saxony, Astrid Koch was returned to her family in Hamburg. However, she had been treated so well in Pulsnitz that she asked her parents to send her back to her host family: “The first thing I told my parents was: ‘I want to go back to Onkel and Tante (I called them that) because I loved being there.’” The Kochs sent her back in the summer of 1942 and Astrid lived there until 1946.

By the summer of 1942, Erwin Frank was on the island of Sicily where he worked as a radio operator reporting flights of enemy aircraft toward German positions. He was scheduled to be sent across the Mediterranean Sea to a station in North Africa, but Allied forces gained the upper hand in the region and the move was canceled. Subsequent transfers took him to the islands of Sardinia, Corsica, and Elba.

The air raids that plagued Hamburg were already taking their toll on the populace in 1942—if not in high death counts, then at least emotionally. Gerd Fricke recalled rejecting instructions to go down into the basement when the sirens wailed one night:

I was too tired to go downstairs, so I stayed in my bed. My mother, my brother, and my sister all went down. I was lying in bed when the roof of our house was blown off. I wasn’t fully dressed, so I ran downstairs in a shirt and pants. While we waited in the basement, a bomb fell into our apartment and everything burned, but we got out of the basement safely. That was the first time we lost everything and it happened again [in 1943].

Walter Menssen once returned to his quarters in a Hamburg suburb to find his commanding officer sitting in a chair, reading in one of his American church books. The officer asked him point-blank if he was a Mormon, and the answer was unhesitatingly affirmative. “That is the only reason you are in this office,” was the man’s response, “because I can trust you.” Walter recalled having taken the officer back to his quarters after too many drinks at social affairs on several occasions and knew that statement to be true. The officer then recounted his experiences in the United States and declared that the greatest man he had ever known was one Heber J. Grant, whom he met in a bank in New York City. “He invited me to Salt Lake, and I stayed in his home for two weeks. I was driven around in Salt Lake and saw everything. That is the reason you are here.” Once again, a soldier of the LDS Church had been rewarded for living a life of high standards.

Indeed, Walter was tempted on several occasions by comrades who wished to see him deny his standards and smoke cigarettes or drink alcohol. They offered him money to smoke and even spiked his soda drinks, “but a Mormon can smell that alcohol a mile away,” he claimed. He used his cigarette rations to pay other soldiers to take over his duty assignments so that he could attend church with his family. “In other words, keeping the Word of Wisdom helped me quite a bit.” [32]

Little children seldom understood the reasons for air raids over Hamburg, but they did not enjoy being rousted out of bed in the middle of the night or sitting in dark and cold basements and shelters surrounded by terrifying noises. Regarding the possibility of being hurt or killed under those circumstances, Ingo Zander’s observations are typical: “I probably didn’t give much thought to dying, but you wouldn’t totally dismiss [the possibility] either. I remember once when a classmate didn’t show up for school, I went to where he lived. Where his house had been, there was a crater as deep as the house had been high and nobody heard anything anymore of him.”

Many children in Germany’s largest cities enjoyed the hobby of collecting pieces of shrapnel from the streets on the mornings after air raids. Karl Schönrock of the St. Georg Branch was one of those collectors, as he later explained: “We collected [the shrapnel] from the antiaircraft shells that exploded [above our homes]. In school we compared who had the most and the best-looking ones.” Sometimes, Karl and his siblings would go outside during air raids and watch the British flares descend from the sky and the shells of the antiaircraft guns attempting to shoot down the enemy airplanes. With metal raining from the sky, they soon learned that it was better to stay inside during such dangerous activity.

Ingrid Lübke (born 1933) had distinctly sad memories of the air war over Hamburg: “My school was next to a POW camp. One day we had an alarm so we left the school to go to a shelter. When we came back, the school yard was full of bodies [of prisoners] and they even hung in the branches of the trees. It was awful!” [33] Later in the war, she experienced a different type of very personal danger: “Sometimes planes intentionally aimed at us children when we were playing. Once, we ran to the next house that we saw and hid there to be safe. Another time, I was playing outside the shelter and a plane shot at me; [the pilot] saw me and I even saw him and I fell down, but nothing happened to me.”

The loss of the meeting rooms in 1943 at Besenbinderhof was painful and very inconvenient. Still very intact, the rooms were needed for more important purposes in the opinion of the city government. After thirty-three years of meetings under what were likely the finest conditions for Latter-day Saints in all of Germany and Austria, the rental contract was canceled and the branch was required to remove the Church property from the building. Historian Hans Gürtler had this to say about the move: “There is no reason to seek the actual cause and perpetrators of the expulsion. At that time, our Church simply did not have the respect it enjoys today [1969] and anybody who did not like us could easily throw stones in our path.” [34] The meeting rooms were confiscated in the spring of 1943, and the members were then required to make their way to the home of the Altona Branch—about three miles to the west across town.

Arthur Zander may have wondered what his role was to be as a branch president without a branch, but the Wehrmacht solved this problem by drafting him in 1943. With the destruction of the family’s apartment in July 1943, Sister Zander took their three sons and headed for southern Germany. Like so many other families in the St. Georg Branch, the Zanders were absent from town for the rest of the war.

Like tens of thousands of other German schoolchildren, Otto Berndt and his entire school class of thirty-five boys were evacuated to the Czech town of Kubice to spare them the dangers of a Hamburg under constant assault from the sky. For two years, the boys lived in a hotel next to the railroad station in that farming community. Their teacher was with them and was what Otto called “a good egg. We weren’t expected to work like slaves. In the morning we had our regular school.” For two years, the boys stayed in Kubice. Otto was visited once by his father; otherwise he was totally isolated from his hometown, his family, and his church. [35]

In August 1943, homeless Gertrud Menssen and her two children were sent to Bavaria where they were taken in as refugees on a farm. At first, the host family gave them poor accommodations and treated them as strangers. The guests could not understand the local dialect, suffered from lice (“how sickening!”), and were very homesick for Hamburg, but “the hardest thing was that we were so far away from the church.” Eventually, Gertrud learned that the LDS branch in Munich was within reach; a journey of one hour on foot and ninety minutes or more by train took her to the Bavarian capital, where she enjoyed meeting with the Saints a few times. “[The trip] took us the whole day and that was hard with little children and me expecting our third.” [36]

Figs. 8 and 9. The Pruess home in Rahlstedt before the bombing (left) and after reconstruction in 1944 (right). The top two floors could not be rebuilt at the time. (L. Pruess Schmidt

Figs. 8 and 9. The Pruess home in Rahlstedt before the bombing (left) and after reconstruction in 1944 (right). The top two floors could not be rebuilt at the time. (L. Pruess Schmidt

Harald Fricke was evacuated with his family (his mother, brother, and sister) to the part of Poland that had been Germany before 1918. He recalled attending church meetings in the nearby branches of Elbing and Danzig—two cities that could be reached by train from Marienwerder where the family was temporarily housed. “We somehow found out where all the branches met,” he recalled. After five or six weeks, Sister Fricke took her children home to Hamburg, where they were assigned another apartment.

As a new recruit, Gerd Fricke went through basic training for six months near Bremen. Just before Christmas 1943, he was transferred to France, but never moved farther west than Luxembourg. He soon became yet another soldier who was harassed because of his LDS health standard: “One time, I was tempted by the other soldiers to drink alcohol. I said that I wouldn’t do it, and they wanted to pour it down my throat. I resisted and they later said that I was pretty tough and really knew what I wanted.”

The family of Emil and Lilly Koch lost everything they owned in the firebombings of 1943. According to daughter Lilly, the family left town and found a place to live near Dresden in Saxony. However, Brother Koch was a city employee, and he was required to return to Hamburg to work. His daughter Lilly went with him because she had a job in a factory where airplane engine parts were made. The two first lived with relatives, but once they found their own apartment, the rest of the family could return from Saxony to be with them.

Lilly Koch described some of the challenges of being an adolescent during World War II:

Being a teenager during the war was not a nice situation. I remember that I turned 18 years old during the war and was astonished that many things were already forbidden—like going dancing. That is why we often felt like we were losing contact with our friends and especially with the other members of the Church because we did not know where all the others were and what we could do. Everything was always destroyed. [37]

The family of district president Alwin Brey had lost everything when their apartment house burned in July 1943. President Brey then took his family to Bamberg in southern Germany where they found a small room to live in. Because there was no branch in that city, Frieda Brey and her children were isolated from the Church. Soon after their arrival in Bamberg, daughter Irma (born 1926) was called to serve a Pflichtjahr (duty year) on a farm. She lived and worked there with many other girls her age who assumed work normally done by the men who had been drafted. Irma was very homesick but was at least safe from the terrible attacks on Hamburg. [38]

Fred Zwick went with his mother to Polzin in Pomerania after their apartment was destroyed. However, his father came on leave and insisted that they return to Hamburg. He told them that the Russians might be invading that area and that he had heard what Russians did to women and children. Back in Hamburg, the only place they could find to live in was a little cottage on a garden property belonging to Fred’s grandparents. He described the structure in these words:

It wasn’t too small of a building. It was livable. It had a little store room and a room for a portable potty, and then a kitchen. We had our water pump; the pipe went out through the wall into a shed and then there was a stove in it and a table of course and windows. Next to it was kind of a living room and next to that was a really small bedroom. There was plenty of room for three people. [39]

Waltraud Schönrock’s life took an early turn toward adulthood when she became engaged to fellow Latter-day Saint Gerhard Kunkel at the age of seventeen. She was eighteen when they were married on September 25, 1943, and she offered this description of the event:

It was a simple wedding. Our mother prepared a small dinner at home and that was all. We got married in the civil registry office [in city hall] first, and then we went to church on Sunday. . . . I had a white dress and even a veil. [Gerhard] returned to his unit a few days after our wedding. We didn’t have a honeymoon. [40]

After the Koch family lost everything they owned in the firebombings, they traveled to Pulsnitz and were taken in where Astrid had been for more than two years. It was nice for the family to be together again, but that experience was short-lived. Brother Koch was required by his employer (the city of Hamburg) to return to work. The rest of the family stayed until after Christmas and returned to Hamburg in early 1944. Astrid remained with her host family for two more years. In Pulsnitz, she joined with her Lutheran hosts in attending church, and they even wanted her to be baptized as a Lutheran because her LDS baptism had been postponed. Astrid eventually learned the local dialect and felt very much at home in her Saxon refuge.

Part of Astrid Koch’s Pulsnitz experience was her membership in the Jungvolk program. She fondly recalled helping make wood toys for children, for example: “We had to sand them and paint them. And we went on outings and field trips, and we collected magazines from local people. Those were for the wounded so they had something to read in the hospitals. They made half of our school into a hospital. When I was a member of the school choir, we went over to the hospital and sang for them at Christmas.”

Fig. 10. The Zwick family acquired this small garden house just before the war and lived in it after they were bombed out. (F. Zwick)

Fig. 10. The Zwick family acquired this small garden house just before the war and lived in it after they were bombed out. (F. Zwick)

After the horrific summer of 1943, Maria Niemann took her children north to the town of Hude in Schleswig-Holstein. They found a very pleasant apartment there; but according to her son Henry, they had no contact with the church for the next four years. Maria continued to have health crises and was in the hospital again when her husband came home on leave. Although she recognized the hand of God in saving her from the destruction of Hamburg, she was without her husband for four years beginning in 1944. It was an especially discouraging time, during which her father-in-law died. Regarding her absent husband, her prayer often included the same plea: “Heavenly Father, don’t let him [have to] kill anybody.” [41]

In early 1943, Werner Sommerfeld was sent away from the dangerous life of Hamburg residents. Placed on a farm in Hungary, he was fed by Germans and for the first time in recent memory, he had “enough to eat for an entire year.” After a year of life in an area where there was essentially no war, he rejoined his family, but not in Hamburg. His mother had taken the children to Jungbuch, her hometown in Czechoslovakia. Werner was still a small teenager and thus avoided being taken away into military service; he was free to begin an apprenticeship in plumbing. It was about that time that Arthur Sommerfeld was drafted and sent to Russia (despite the severe burns he suffered in July 1943) and that their father, Gustav, was sent to France that where he soon became a prisoner of the British and was moved to England. [42]

Anna Marie Frank (born 1919) had lost her apartment on July 28, 1943, and her two-year-old daughter, Marianne, had disappeared in the smoke and flames of the burning city. Sister Frank was then evacuated to eastern Germany with her son Rainer (only fourteen months old). While there, another disaster befell the family when Rainer contracted diphtheria and died in April 1944. Bereft of both of her children, Anna Marie returned to Hamburg and found a job in a factory and mill where she sewed bags for flour. She worked there through the end of the war and for some time afterward. It was not until 1946 that she learned that her husband, Willy Frank, was a prisoner of war in Yugoslavia. She wrote to him every week from then until his release in 1948. [43]

“After we were bombed out [and lost everything], we lived in the garden plot community,” recalled Ingrid Lübke. Her description continues:

We didn’t have electricity, water, or a bathroom. We got our water from a pump, but in the winter it froze and we had to take hot water and pour it over the pump so that we could get at least some water. It was also far away and [the bucket] was heavy to carry. When it came to food, it was sparse but we had an advantage because we had some garden land around our little house. I remember my grandmother telling me one morning: “Look, there are two slices of bread, a little bit of sugar, and some black coffee. That is all I have for today.” We ate rutabaga and we ground fish heads so that we could eat them.

Gertrud Menssen’s third child, a son named Wolfgang, was born in Bavaria in February 1944. Thinking that Hamburg had been sufficiently destroyed to no longer merit the enemy’s attention, Gertrud longed to return and prayed and fasted many times for a confirmation of that plan of action. Her husband had been transferred to a town close to Hamburg and learned that his family could apply for a modular cottage that could be erected on his garden property (to replace the original hut that had since been destroyed). By March, their application was granted and their new cottage constructed. According to Gertrud, “The house was great—it had a big family kitchen and one bedroom just barely big enough for two sets of bunk beds (from a bombed-out shelter) and one crib which was a miracle to find. . . . No plumbing, of course—outhouse only.”

Soldier and staff member Walter Menssen was often able to spend weekends with his family. Unfortunately they were still not safe from enemy attacks and he soon dug out a shallow bomb shelter near the cottage. They took a practical approach to life in the last year of the war, as Gertrud recollected: “We did not worry anymore to have to die. We only had one wish every night—that we could all go together. If Walter could be with us all was fine.” In her husband’s absence, Gertrud scraped meals together from ration coupons, but had to leave the long lines in front of stores on occasion when the air raid sirens wailed. “It was really bad again, but we lived through it all.” They did indeed, and Walter returned shortly after the war to a loving family. [44]

In a most daring move, Walter Menssen forged release papers for two of his brothers-in-law. Because he worked in the air force administration office, he had access to nearly everything he needed to issue papers that would allow his relatives to leave the military early and return home—everything, that is, except the official stamp of that Luftwaffe district. His solution was novel: “I took a fresh egg, cooked it, peeled it, and rolled this egg over an old seal of old papers of mine and then took that egg and put that seal over the new paper I had written.” By securing a release for his relatives, Walter may well have saved them a term in a POW camp after the war or even a fate much worse. [45]

In the fall of 1944, orders were given to German soldiers to defend the Mediterranean island of Elba to the last man. Fortunately, Erwin Frank was suffering from malaria at the time and was on the opposite side of the island from the French landing and the combat that ensued. The contingent of three thousand German defenders was soon reduced to three hundred (among them Erwin Frank) who were finally extracted from the island. From that point, Erwin saw only Italy and points north. Whatever the military and the media wished to call the moves of the next few months (such as a “repositioning”), Erwin understood it to be a steady retreat. However, things were not all bleak in his life. On his last wartime visit home, he met and fell in love with a young lady of the Barmbek Branch—Ruth Drachenberg. They were engaged in October 1944.

The St. Georg Branch history includes several comments regarding the few men left in Hamburg as the war dragged on. They were mostly too old to serve in the military, and they took on three, four, or more assignments vacated by the young men who were drafted. However, Hans Gürtler stated in his branch history that the spirit remained very positive among the members as they gathered to worship, and in some respects, the members of the branch grew closer in those challenging times.[46]

As the company clerk, Brother Gürtler traveled frequently during the war but was never in combat and never in danger. In his autobiography, he detailed his route through eastern Europe in 1942–44. He had time to make friendships, carry on extensive correspondence, and write poems to send to his brother Siegfried, an actor and voice talent at the state opera in Bielefeld. In 1943, Hans had moved his wife and their children to the eastern Bavarian town of Cham, where Brother Gürtler sent all possible extra food from his rations (and the booty gained from swapping cigarettes with comrades). Karla Gürtler had lost everything in the destruction of Hamburg but lived in good circumstances with her children in Cham. [47]

Ingeborg Thymian recalled the following about those who attended the meetings in Altona after all three Hamburg branches were united:

The attendance pretty much stayed the same. What astonished me was that there were many handicapped people in our branch. Even our branch president was blind. We could count the healthy people on one hand. Every other person had some disability, for example having lost a leg or an arm. It was a unique situation and I always wondered why, but I think it must have been because of the war. The branch president also brought his dog with him to the meetings. He would lie next to him at the podium in order to help with anything that his master needed.

“It took us about fifteen or twenty minutes to reach the air-raid shelter from our home,” explained Hertha Schönrock regarding air raids during the last year of the war. “We also had to take the stroller with us for Waltraud’s baby. One wheel kept falling off and so it took us even longer. Sometimes, the [illumination flares] were already coming down, and we were still walking.” The tension must have been severe at such moments, because the bombers followed the flares marking the target by only a few minutes. One of the raids damaged the roof and the windows of the Schönrock apartment, and eventually there were eleven persons sleeping in the living room.

Even Wilhelmsburg, a suburb south of Hamburg’s harbor, was damaged in the attacks. Hertha and Waltraud Schönrock experienced the attacks in terror one night when the British dropped phosphorus bombs, and Waltraud’s leg was burned.

It hurt my leg very badly and I could even stick my fingers into [the holes in] my leg. I sat in water all night and that relieved the pain. The stairs down to the canal were full of people and . . . they were burning. My husband’s pants were on fire so he jumped into the canal. We saw terrible things. People were sitting by the side of the streets burning. My father and my husband went back the next day to find our grandparents, but they didn’t survive.

It was nothing short of remarkable that Richard Pruess found enough building material to restore the lower floors of his Rahlstedt house during the war. “You could hardly get a nail in those days, but we somehow got nails, wood, and glass,” recalled Lieselotte. Several Russian POWs were allowed to assist in the reconstruction of the home. The rest of the family out in Poland were worried about the approach of the Red Army from the east and wanted very much to return to Hamburg. A few months later, they did and “we lived in the basement because there was [almost] nothing upstairs.”

Richard Pruess Jr. was a soldier who made a comment often attributed to German LDS young men: “My only wish is that I won’t have to kill anybody in this war.” His sister, Hilde, heard him make this statement before he left home in the uniform of the Wehrmacht. In August 1944, another sister, Lieselotte, had a remarkable dream:

My brother [Richard] came to me in a dream. He was a soldier in France at the time. He said, “This is the end for me, but didn’t we have beautiful times together? Didn’t we have beautiful times when we were little?” In other words, he kind of said good-bye to me. A week or two later, we got the message that he had died. Then I remembered the dream and connected it to the time he died. It was kind of sad when you said good-bye, but the memories he brought to my mind were nice memories.

By the late summer of 1944, former branch president Arthur Zander had been transferred from the Netherlands to France as the Wehrmacht tried to counter the Allied invasion after D-Day. He was wounded, captured there by the Americans, and then shipped as a POW to the United States. He stayed in Oklahoma until the end of 1945 then was returned to Germany and Hamburg.

For the last year of the war, Irma Brey served in the Reichsarbeitsdienst. Assigned to work in an underground munitions factory, she was frightened by the Russians who worked with her. She lived in army barracks with other young women. All during her service away from home, on the farm, and in the munitions factory, she was totally isolated from the Church.

Life was difficult for Hamburg residents of all ages, but youngsters like Fred Zwick still found happy ways to pass the time. Before the family’s apartment house was destroyed, he played with his friends at a kindling wood business next door. They would climb on the wood piles and make structures with bundles of wood. Later, he lived near a park called “ash mountain” with a playground and a swimming pool. “In the winter, we took our sleds there and went sledding down the little hill made of ash,” he explained. Fred met some French laborers at a local greenhouse and he played with them. “Somehow they got hold of some sugar once and made candy for us. They were our favorite guys to be with.” Life was not all suffering and privation in wartime Hamburg.

Fig. 11. The Zwick family managed somehow to find a Christmas tree in 1944. (F. Zwick)

Fig. 11. The Zwick family managed somehow to find a Christmas tree in 1944. (F. Zwick)

The branch history includes some very sad notes about the members in the early months of 1945 as the war drew to a close: “Not only was it a struggle to make the trek for hours to Altona to the meetings, but the winter of 1944–45 was bitterly cold in the rooms. On the coldest days, the water froze in the sacrament cups! The terrible inflation added to the suffering of many members.” [48] With the three branches in the city united as one, the attendance was usually about one hundred persons. There were generally only Sunday meetings held in early 1945.

After two years in the Czech town of Kubice with his school class, Otto Berndt was invited in January 1945 to join the army. As a member of the birth class of 1929, he could not be forced to serve, so he chose to attend the Adolf Hitler School east of Prague. In the confusion of the war, he did not stay at that school but returned to Hamburg instead. Back at home, he was ordered to report for military service but was classified as unfit for regular duty. He was handed a rifle and ordered to join the home guard in defending the city. As he recalled, “I was supposed to be an ammo handler for an 88 mm gun. For some reason it never materialized that I was really drafted. My dad told me, ‘Don’t be a dead hero.’” Rather than look for a fight to join, Otto Berndt and his father traveled to the town of Nitzow, near Berlin, to gather the rest of the family and move them back to Hamburg. It was already clear that the Nitzow area would be included in the Soviet occupation zone, and President Berndt had no intention of leaving his family in that region. [49]

In early 1945, Hilde Pruess was again away from Hamburg, this time living near the home of the Wagner family, members of the branch in Annaberg-Buchholz in the East German Mission. She enjoyed attending church meetings with the Wagners; but when the Soviet army approached the town, Hilde was put on a train all by herself and sent back to Hamburg. She recalled her fears at the time:

I was eleven years old and had to cross the country by myself. Suddenly, I met a strange lady who said that I could take the last train to Chemnitz. I thought she was an angel. I don’t remember if I was carrying a suitcase, but I know that I was praying. I just took train after train until I got to Hamburg. When I arrived at my home, my parents didn’t recognize me. I had been gone more than a year and was wearing a hat, so my dad didn’t know who I was at first.

Lilly Koch described the challenges of attending church in Altona when her family lived in the distant southern suburb of Harburg—well beyond the Elbe River harbors south of Hamburg: “The streetcars were usually not running on Sundays and it was too far to walk, or there were air-raid alarms and we couldn’t go. There were still enough priesthood holders to administer the sacrament if we did attend the meetings. Before the war, we had enjoyed special programs and celebrations, but during the war such events were not possible.” The Koch family survived the war intact. “During the air raids, we sat in the basement in the corner as a family and prayed to our Heavenly Father to help us,” explained Lilly.

In February 1945, political prisoner Karl-Heinz Schnibbe was released from his prison cell on an island of the Elbe River. (“It felt like Alcatraz to me.”) He was allowed a short visit with his mother before he was sent to the east to help defend Germany against the Soviet invaders. While with his mother, he spent several precious hours sitting in an air-raid shelter beneath the main railroad station. Among other news, his mother told him that she and his father needed more than three hours to walk through the rubble of the inner city from their home to the meetings in Altona. After their talk, Karl-Heinz left the air-raid shelter and departed immediately for the Eastern Front. He would not see his mother again until 1949.

The last major air raid over Hamburg occurred in March 1945. Karl Schönrock recalled being a bit too far from the concrete bunker when the alarms sounded, but wanting very much to get there:

The soldiers were just ready to close the door as I came running, and I got in there and only a few minutes later we got a direct hit on that [bunker]. As a matter of fact, it tilted towards the crater. . . . It’s a strange feeling when the earth shakes like in an earthquake. And they didn’t just drop a bomb here and there; it was carpet bombing. We had about a dozen craters on the soccer field right next to our home. We had one big crater in the backyard which was maybe thirty yards away from the house where it hit our favorite apple tree (the tree disappeared). The crater was big enough to put half a house in, mostly because the ground there was really soft. . . . It looked like the craters of the moon.

In the last months of the war, Inge Laabs learned what it was like to go without the basic necessities of life: “I remember that it was hard to find anything to wear to keep warm. Our shoes were worn and our clothing had holes. We were cold.” [50] It was hard for Inge to see her hometown in ruins: “Some parts of the city were closed to pedestrians because so many dead people were lying in the streets.” The war ended on Inge’s seventeenth birthday, May 8, 1945; but just a few weeks before that, she and her family members were still trying to avoid attacks by dive-bombers. “We couldn’t even go out to get water without something dangerous happening. When they attacked us, we jumped into the bushes. We also couldn’t make fires to cook or keep us warm.” Regarding her attitude toward the death and destruction of the war, Inge stated, “I tried to make the best of everything and turn it into a positive experience. Now I know that I was often protected by my Heavenly Father.”

Although he did not qualify for military service, Werner Schönrock came close to losing his life in early 1945. Caught outside in a sudden air raid, he felt a piece of shrapnel hit his hand. He was standing at that moment next to a neighbor who was home on leave from the army. That neighbor sustained such drastic shrapnel wounds that he lost a leg. In the same attack, a bomb fell into the apartment building where the Schönrock family lived, but the damage was not severe. According to Werner, “We were lucky that nothing else [tragic] happened that day.”

The American advance overtook Gerd Fricke’s unit in 1945. “One time they attacked us with phosphorus and I thought I wouldn’t survive.” A buddy was killed just a few feet from where Gerd was standing. The advancing GIs soon made Gerd a POW. His experience of being incarcerated by the Americans in Germany was very short but not as pleasant as reported by German POWs who spent time in the United States. According to Gerd:

We slept in a potato field and [the guards] enjoyed seeing us get wet when it rained. [One day] they drove us out of Ulm [in southern Germany] and demanded that we give them everything we owned. Then they allowed us to do whatever we wanted, so many of us simply started to walk home. [The Americans] didn’t want to give us a train ticket home, but I protested, saying that I had fought for my country and now I deserved to ride the train home. I rode on a coal car and was filthy when I got home. It was wonderful to see everybody again. My mother hadn’t known if I was alive or not because I hadn’t been allowed to write home while I was a POW.

Far from the rubble of Hamburg, Sister Niemann and her two children were spared the ravages of war and a dangerous invasion. According to her son, Henry, the war ended in the town of Hude when the last German defenders retreated through the area. “The British came with their tanks and rolled through. They were there and that was it.” [51] Henry had just turned nine years old and had little recollection of life without war.

With the British army just twenty miles from Hamburg, Walter Menssen decided that he was through with the war. Discarding his uniform in favor of a civilian suit, he packed his things and was ready to leave his quarters when his commanding officer entered. Thinking that he might be shot as a deserter, Walter was relieved when the man offered him the use of his staff car to go home. “No, I take the motorbike,” he replied. “I wish I could do it [go home] too, but I can’t,” replied the officer. Walter’s unit left for the Danish border to the north, but ran into the British on the way. The ensuing battle cost many of the men their lives even though the war was long since lost. [52]

For Astrid Koch in faraway Pulsnitz, the war ended when Polish soldiers appeared in town and began to loot. They were driven out by the locals, but soon the Soviet army appeared, and life for Astrid (not yet thirteen) became a little frightening. Her host family took her, and they fled for a few miles but were overtaken by the conquerors. As she recalled:

We had to be careful because they were after all the girls and women. A lot of people got raped. The niece of the people I stayed with was twelve years old and she got raped. My hosts must have been scared to death taking care of me. They hid me in a building where they made elastic stuff. When the Russians came back, they went looking for the women and children. We had a man looking out for us and he told us to hide. So they put us in one kind of a storage room and put boxes and everything in front of the door, but they found out there was a door behind it. So they had us all come out, all of us women and children. A soldier with a big gun told us to stay outside in the sun, but only one woman was raped and nothing happened to the rest of us.

On May 6, 1945, the commanding officer of Erwin Frank’s unit made these comments: “They want us to stay together in case they need us for some action or cleanup, [but] if any of you think you can make it home, you’re welcome to try. I can’t give you any release papers, so you’ll be on your own.” Erwin went to the nearest village where he found people who could provide him with civilian clothing and a bicycle. He needed to ride his bike for only one day to reach Hamburg. He was home but without official release papers from the British occupation authority, he could get neither employment nor ration coupons. In August 1945, he reported to the authorities in Hanover and was given the necessary papers. [53] That month, he married Ruth Drachenberg, and they began a new life without National Socialism.

When the British Army entered Hamburg, no attempt was made to defend the city. Ingrid Lübke had positive recollections of her encounters with the “Tommies”: “The British came to Hamburg first, and the children ran out to meet them and they gave us chocolate. I didn’t know what a roll was or a banana and an orange but we could suddenly buy them again in the grocery stores.” All over western Germany, children were treated very kindly by the invading forces, and many LDS eyewitnesses would later tell of such encounters with fond memories.

Three days after returning home (in time to greet his new baby girl), Walter Menssen was arrested by the British, but his charmed life in the service seemed to continue. Despite being terribly hungry and lacking proper facilities on occasion, he was home with his family in a few months and immediately joined the surviving Saints who were meeting in the Altona Branch rooms. [54]

With peace restored and the war ended, the dispersed members of the St. Georg Branch began to return to their devastated city. According to Hans Gürtler:

From wherever they had been scattered, fled, or sent all over Germany, they came back in the summer of 1945—the families, the mothers with their children, the widows, the flak assistant girls and the brethren who were fortunate to be POWs for just a short time. But many, many did not return. Several men were still missing in action and others still in POW camps. [55]

Hans Gürtler spent the last few months of the war in Hungary and Austria. He was taken prisoner by the Americans near Salzburg in May 1945, and it was then that he first experienced the trials of being a soldier. Going without food, water, or shelter for days on end, he lost his favorite possessions as GIs divested him of most of his personal property. Moved across southern Germany to France, he was handed over to the French and put to work. In St. Avold he experienced what he would call “the worst experiences of my POW time.” Although he allied himself with the cultural arts groups in the camp, he worked with a crew of prisoners assigned to remove land mines from the countryside. The danger was severe, and he became seriously ill at least once. [56]

Hans Gürtler’s daughter Therese summarized her sentiments about the war and her belief in God in these words:

We didn’t have to maintain a testimony. It was just always there. There was never anything happening that would endanger my testimony, or where I would question that maybe God didn’t love me because I had to suffer. I don’t have any ill memories of the war. None at all. Only the sound, when the air raid was announced. That is a sound that was frightful. But I don’t have any negative memories from the war. So my testimony was never attacked. It was intact.

Marie Sommerfeld and her children were quite safe in Czechoslovakia until the last months of the war when Germans in that area became personae non gratae. At first, Czech authorities told them to leave, and then the Soviets took over and forced their departure. Loading their things into a two-wheeled cart, they slowly made their way toward the German border. With nothing to eat, they dug for potatoes in nearby fields. Because of the reports of molestation by conquering Soviets, Marie’s daughters dressed as boys and tucked their hair into their caps to avoid attracting attention. Werner was brokenhearted when Russian soldiers stole his accordion. Near the city of Dresden, Leni Sommerfeld became separated from the family—apparently abducted by a Russian. As Werner later wrote, “We waited and searched in the city of Dresden, hoping against hope that she would turn up. In the end there was nothing for us to do but to press on for Hamburg.” Sister Sommerfeld was suffering from a serious kidney ailment during the entire trip home and the loss of her daughter was nearly overwhelming. About one month after arriving in Hamburg, Leni showed up and reported that she had managed to escape harm during the separation from her family. The only place the Sommerfelds could find to live was in the basement of an apartment building under construction; there were no doors or windows in the structure. During the winter of 1945–46, they came close to freezing to death and both Arthur (already home from the Eastern Front) and daughter Mary became seriously ill. Fortunately, everybody survived the trials and Gustav Sommerfeld eventually returned from his tenure as a POW.

Looking back on the difficult experiences of the war, Werner Sommerfeld made this summary statement:

The German people are good, strong, faithful people, and my mother in particular was a woman of great faith. Many times, she didn’t know where she would get food for her five children. She prayed many times and there were many, many miracles in her life where she just found food at the door or somebody just came by with food. And that was not just true with our family. The [Latter-day Saints] trusted in the Lord and lived by faith each and every day. [57]

When Arthur Zander returned to Hamburg in 1946, he found his wife and his three sons living in a tiny (six-by-twelve-foot) garden shed. The structure was so small that according to Ingo, “there were no utilities at all, because it was not designed for people to actually live there. In the morning we had to take out our beds to make way for a table and chairs and at night we reversed the procedure.”

As a seventeen-year-old, Harald Fricke had finished his service with the Reichsarbeitsdienst and was drafted into the Wehrmacht. Stationed near the Baltic Sea, his unit was passed by as the Red Army rushed toward Berlin. After the war, he and his comrades were transported as POWs to the city of Stalingrad, where they helped clean up and reconstruct that important industrial center. He recalled some of the trials of the experience:

At the age of nineteen, I suffered from constant hunger and the lack of proper hygiene. I only survived because a Russian woman doctor sneaked me some medicine and hid me when it came time for physical examinations. Every day German soldiers died in the camp and their bodies were loaded onto small carts and dumped into mass graves. While working near the Volga River during the winter [of 1945–46], the tip of the big toe on my right foot was lost to frostbite and I suffered from thrombosis and other illnesses. This made me incapable of working and I shrank to skin and bones. So they shipped me home which was a great blessing. [58]

When Harald returned to Hamburg, his mother told him that she had constantly prayed that somebody would care about and for her son. The Russian doctor had been that somebody.

In the summer of 1946, Hans Gürtler was released from the POW camp in France and sent to Münster in northwest Germany to be processed out of the military. He immediately made his way back to the northern Hamburg suburb of Rahlstedt, where his family had been living since the end of the war. Not knowing precisely where his family lived, he tossed pebbles against windows after midnight until he woke neighbors who could give directions. He recalled the reunion: “Karla woke up and then . . . she and the children, all of them suddenly wide awake, came down in their pajamas. What a reunion!” They entertained each other with stories as he unpacked the goodies he had brought home—including many poems, a piece of leather, and a chess game. “After six years, I was finally free!” he wrote. [59]

Since March 1941, Karla Gürtler had taken care of four children almost totally by herself. However, she recalled the life of a single mother in positive terms: “Of course it’s difficult to be a mother in the war, but everyone was in the same boat. When times got tough, I lived through them the best I could. I had to live for my children. And I think the link to the Church was more intensive during such a time because we needed the faith.” [60]

After spending four years away from Hamburg, Maria Niemann finally returned to her apartment in 1946. Although extensively damaged in the air raids, it had been repaired, and refugees were living there when the Niemanns arrived. At first, the refugees insisted that they had forfeited their rights to the apartment by being absent for so long, but city officials intervened and asked the refugees to leave. Maria was home, but she had not heard from her husband since the end of the war. “I prayed and my children prayed,” she recalled, “and my daughter put his picture in the window every day and said, ‘My father, please come home, I love you.’” [61]

In the summer of 1946, Astrid Koch’s mother made her way illegally across the border into the Soviet occupation zone to pick up her daughter in Pulsnitz. There were serious challenges to be overcome when the two made their way back to the British zone, but they managed to do so without injury. After being away from Hamburg for five of the previous six years, Astrid lived with her family in a small apartment her father had found in the rubble of the port city. The Kochs were together again and looked forward to a totally new phase of life.

Frieda Frey and her children had spent three years in the Catholic city of Bamberg in southern Germany. It was a beautiful town, and they enjoyed the peace that prevailed there, but it was a happy day when they returned to Hamburg in 1946. Two years later, former district president Alwin Brey was released from a POW camp and made the trek home to his family.

Willy Frank (born 1915) was captured in Yugoslavia at the end of the war. As a POW there, he wrote to his wife, Anna Marie, every week; but until 1946, he did not know whether she was actually alive. Finally, his message got through via the Red Cross; he was able to write to her and she was able to write back to him. They had lost their two children, and this was a very lonely time for both. One day in 1948, it was announced that his group would be transported to Germany. They rode in boxcars from Yugoslavia to Germany; then they were allowed to ride in first-class coaches for the rest of the trip to Hamburg. For his time and labor as a prisoner of war, he was paid a total of 50 Marks (about thirteen dollars). He had lost nearly half of his weight during his term as a POW. [62]

The war was fully four years in the past when Fred Zwick’s father returned from a POW camp in 1949. Sister Zwick had written many letters after the war to locate her husband. It was likely a very sad time for her, but she did not express that openly to her son. As Fred recalled, “Children really weren’t included in family affairs or with parents. Children weren’t told much.” Finally, a connection was established with Fred’s father through the Russian Red Cross, and things began to look up. When he returned, his wife and his son were still living in the garden cottage.

“When I came back to Hamburg in 1949, the city was one big heap of rubble,” recalled Karl-Heinz Schnibbe. As a political prisoner and then a POW in Russia, he had sacrificed seven years of his young life, but he was happy to be home with his family. “The streets were cleared, and the rubble was piled up on the sides. And everywhere things were being built up and repaired again. I found my street right away.”

Perhaps more than any other LDS branch in the West German Mission, the St. Georg Branch was practically broken apart during World War II. After losing their comparatively luxurious meetinghouse, the members had been dispersed all over the continent. Many families were homeless and separated, taking refuge in what they hoped were safe and peaceful locations within Germany. In essentially every case, they were isolated from the Church while away from Hamburg. Those who stayed in the city during the war and could still attend church meetings made the long trek through the rubble of their city to the meeting hall in Altona, where important vestiges of their Latter-day Saint existence were maintained. There were enough older men at home to administer in all priesthood functions. With the war over, the Saints of the St. Georg Branch would need nearly five years to gather home, and their branch was never reconstituted. Beginning in the summer of 1945, they became members of several new branches in and around the city of Hamburg. At least forty members of the branch (10 percent) did not live to see peace return to Germany.

In Memoriam

The following members of the St. Georg Branch did not survive World War II:

Walter Heinrich Johannes Bankowski b. Hamburg 19 Nov 1910; son of Ludwig August Otto Bankowski and Auguste Caroline Sievers; bp. 28 Jan 1930; conf. 28 Jan 1930; ord. deacon 13 Oct 1930; ord. priest 4 Jan 1932; ord. elder 26 Feb 1935; m. Hamburg 24 Mar or Apr 1937, Anna Wittig; d. stomach tumor 19 June 1944; bur. Pomezia, Italy (FHL microfilm 68804, book 1, no. 19; www.volksbund.de; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 8; IGI)

Martin Heinrich Friedrich Bergmann b. Fliegenfelde, Stormarn, Schleswig-Holstein, 23 Jun 1887; son of Christian Friedrich Bergmann and Luise Dorothea Anna Kämpfer; bp. 2 Jun 1911; conf. 2 Jun 1911; ord. elder 2 Jun 1927; m. 5 Jun 1943, Caroline Kropp; k. air raid 28 Jul 1943 (FHL microfilm 68804, book 1, no. 37; CHL CR 275 8, no. 317; CHL 10603, 118)

Ilse Johanna Charlotte Blischke b. Burg, Jerichow, Sachsen, 25 May 1911; dau. of Fritz Blischke and Anna Louise Graul; bp. 17 Feb 1925; conf. 17 Feb 1925; missing as of 20 Mar 1946 (FHL microfilm 68804, book 1, no. 31; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 231)

Carl Waldemar Bobbermin b. Itzehoe, Steinburg, Schleswig-Holstein, 2 Jul 1911; son of Wilhelm Fr. August Bobbermin and Auguste Krempien; bp. 22 Apr 1923; conf. 22 Apr 1923; k. while deactivating bombs 17 Apr 1947 (FHL microfilm 68804, book 1, no. 42)

Emma Ida Bochnia b. Klein-Lassowitz, Rosenberg, Schlesien, 21 Nov 1901; dau. of Friedrich Bochnia and Bertha Maleck or Malesk; bp. 27 Dec 1931; conf. 17 Dec 1931; m. 21 Nov 1936, Johann Friedrich Paul Haase; k. air raid Hamburg 28 Jul 1943 (FHL microfilm 68804, book 1, no. 139; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 64; CHL 10603, 118)

Elke Brey b. Hamburg 19 May 1942; dau. of Alwin Max Brey and Frieda Ocker; d. scarlet fever 27 May 1945 (FHL microfilm 68804, book 1, no. 49; IGI)

Carla Maria Cizinsky b. Hamburg 16 or 18 Aug 1942; dau. of Walter Theodor Wilhelm Cizinsky and Carla Maria Krüger; d. diphtheria 16 Mar or May 1945 (FHL microfilm 68804, book 1, no. 60; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 478; IGI)

Alfred Werner Frank Fick b. Hamburg 6 Jul 1925; son of Richard Karl Wilhelm Fick and Grete Anna Elisabeth Schloss; bp. 18 Sep 1933; MIA 1 Jun 1943 (E. Frank; www.volksbund.de; IGI, PRF)

Marianne Sonja Frank b. Hamburg 14 Jun 1941; dau. of Willy Richard Otto Frank and Anneliese Haase; k. air raid Hamburg 27 or 28 July 1943 (FHL microfilm, location by W. Frank; FHL microfilm 68804, book 1, no. 105; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 451)