Saarbrücken Branch

Roger P. Minert, “ Saarbrücken Branch, Karlsruhe District,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 254–63.

The city of Saarbrücken lies astride the Saar River, which forms part of the boundary between Germany and France. Located in the middle of an important iron-ore region, the city’s value to Germany caused it to be contested in several wars over the centuries. In 1939, the city had 131,000 inhabitants. [1] The local LDS branch was truly a frontier outpost, because the nearest branches to the west were deep inside Belgium and France.

With twenty-two priesthood holders among its 111 members, this branch was in very good condition as World War II approached. The branch president was Paul Prison. His family and several others lived in the town of Dudweiler, two miles east of Saarbrucken. According to the directory of the West German Mission, most Church programs were operating in this branch in July 1939. [2] Meetings were held in rented rooms at Kronprinzenstrasse 9 in Saarbrücken. As was true all over the mission, Sunday School began at 10 a.m. Sacrament meeting was held at 3:00 p.m., preceded on the last Sunday of the month by a genealogical meeting. The Relief Society met on Tuesdays at 6:30 p.m. and the MIA at 8:00 p.m. No Primary meetings were being held at the time, despite the fact that the branch membership included eighteen children.

| Saarbrücken Branch [3] | 1939 |

| Elders | 8 |

| Priests | 4 |

| Teachers | 3 |

| Deacons | 7 |

| Other Adult Males | 21 |

| Adult Females | 50 |

| Male Children | 10 |

| Female Children | 8 |

| Total | 111 |

Fig. 1. The wedding of Elisabeth Klein and Hans Reger in 1937 was celebrated in the chapel of the Saarbrücken Branch. Note the pictures of Joseph Smith (left) and Christ in Gethsemane (right). (H. Reger)

Fig. 1. The wedding of Elisabeth Klein and Hans Reger in 1937 was celebrated in the chapel of the Saarbrücken Branch. Note the pictures of Joseph Smith (left) and Christ in Gethsemane (right). (H. Reger)

In August 1937, Elisabeth Klein of the Saarbrücken Branch married a fine non-LDS man, Hans Reger. A year later, she was the mother of a baby girl and he was away from home in the service of his country. Elisabeth lived in an apartment at Metzerstrasse 25 and continued to enjoy her association with the Saints in Saarbrücken. As she recalled, “We branch members were all friends. We didn’t have any friends elsewhere. The Church was all of our activity. About forty or fifty people came to church in those days.” [4]

Paul Prison (born 1925) described the building in which the branch met:

The room was about thirty feet long and thirteen feet wide. It was kind of a Hinterhaus with an empty garage in front and a big door where we parked our bicycles. And then there were two steps to go into it and there was kind of a potbelly stove that we heated in the wintertime. There was a sign with the church’s name on it, maybe three by four feet out where everybody could see it. Our building was across the street from a big Catholic church with a tall steeple. We had a pump organ and behind that was a door and there was a little room where the children went and we had another room on the right side (they took that away during the war because they needed room for the people to live there). There were four chairs on the left side and three on the right side of each row, maybe ten to twelve rows. I don’t think we had more than thirty-five to forty people in there because some lived very far away. [5]

Paul recalled going with his father (branch president Paul Prison) to visit members who lived many miles from town. “They didn’t come to church very often. I would say we had about fifteen to eighteen people out of town [as far as fifty miles away].”

Branch president Paul Prison was a coal miner. By the time the war was well under way, he was required to work seven days a week. However, according to his son, Paul, there were ways to avoid that in order to attend church. “My father told his boss that he was sick on Sunday. When they asked for a note from his doctor, he told them that the doctor’s office was closed on Sunday. If you were productive (and my father was) and they needed you, you were safe. Wherever he worked, there was never a cave-in.”

Even before the war began, a member of the Saarbrücken Branch became a victim of the Nazi regime. Harald Ludwig Adam (born 1931) was taken from the family when he was six years old. According to his elder brother Max (born 1927), Harald was mentally handicapped and could not learn,

but his body was in perfect shape. . . . When school time came and he was six years old, two devils came to my parents and told them of a wonderful hospital which was created by Hitler for people like my brother, and they would help him. He was taken to the hospital just north of Frankfurt. Idstein is the name of the town. . . . My parents always got a letter every two months that he was doing well and was happy. They said that we could not see him because if we saw him it would destroy what he had learned. Then we got a telegram that he passed away; it said that he died of the flu and a heart condition. But there is no heart condition [history] in our family at all so I always wondered what happened. Mother in her heart knew what had happened. [6]

Harald Ludwig Adam was one of tens of thousands of victims of the government’s infamous euthanasia program. [7]

When France and Germany issued mutual declarations of war in September 1939, Elisabeth Klein Reger and her daughter were evacuated from Saarbrücken under the assumption that the border city would soon be under attack by the French. While living in Landstuhl, Elisabeth gave birth to another daughter. After the surrender of France in June 1940, Sister Reger and her two daughters (Isolde, born 1938, and Ingrid, born 1940) were allowed to return to Saarbrücken, where she lived in her widowed mother’s apartment.

Young Paul Prison avoided associating with the Hitler Youth and somehow got by without punishment. However, the war inflicted pain on this fifteen-year-old early on when a bomb hit the home of a friend across the street from the Prison home in Dudweiler:

My friend died in 1940, my good friend. He lived just kitty-corner across the street from us. He was my age. It was about 9 or 10 p.m. and I heard an airplane flying around and around very low, and then I heard a big explosion. That big explosion threw me right out of my bed, and I looked out the window, and my best friend’s house was on fire. I got my clothes on and went there, and the house was completely collapsed, and there were already several people. We took our shovels and started digging people out. Eight people lived in that house, and my friend was the first one we could see, but he had a big beam right on top of him, and he was still alive. We couldn’t get it off of him, so somebody went and got a big saw, and we had to saw it in three places. By the time we lifted the beam off, he was dead. Then we got the others out; we got his mother out, but she had no head anymore. Then we got his father out, and he was dead. Then we got the others out. Eight people, we laid them all out across the street on the grass. And while we were shoveling them out, the airplane came around several times and shot at us with machine guns.

Fig. 3. Youth of the Saarbrücken Branch with missionaries in 1938. (C. Hillam)

Fig. 3. Youth of the Saarbrücken Branch with missionaries in 1938. (C. Hillam)

At the age of ten, Max Adam had been inducted into the Jungvolk with his classmates at school. At fourteen, he was advanced into the Hitler Youth and the Sunday meetings of that organization conflicted with the branch meeting schedule. Max’s father, master cabinetmaker Max G. Adam (not a member of the Church but a kind supporter of his wife and sons), came up with a fine plan to allow young Max to miss the Hitler Youth meetings. One of the organization’s programs collected gifts for children each Christmas. The leaders fell for Max’s idea: if the boy could produce fifty toys for Christmas, he would be exempt from attending meetings. This allowed Max to continue to attend church meetings on Sundays.

At the age of fifteen, Max was assigned to work on a farm for a year. The farm was located several hundred miles from Saarbrücken, so Max was unable to visit his family at all during this year of service. Living with other boys in a camp, he participated in a flag-raising ceremony every morning before walking to the farm to which he was assigned. He was totally isolated from the Church while there. Back at home in 1942, he found that Saarbrücken was harassed by air-raid alarms quite often. Allied bombers rarely attacked, but every time they flew to other cities and passed within a certain number of miles of Saarbrücken, the alarms sounded and another night’s rest was disturbed.

One night, the airplanes that had so often passed Saarbrücken on their way to other targets unloaded their bombs there. Within minutes, apartment houses were burning in the neighborhood of the Adam home. Max recalled being part of a bucket brigade as local residents worked feverishly to prevent a fire on the top floor of the building from spreading downward and to adjacent structures. In that same attack, the top floor of the Adams’ apartment building was damaged, but the family’s apartment was still inhabitable. They replaced broken windows with cardboard and were grateful to still have a place to live.

Fig. 4. Max Adam in the uniform of the National Labor Service in 1942. (M. Adam)

Fig. 4. Max Adam in the uniform of the National Labor Service in 1942. (M. Adam)

Horst Prison (born 1920) was drafted in 1940 and sent to nearby France. By June 1941, he was on the Eastern Front and participating in the invasion of the Soviet Union. His experiences there were extremely challenging, beginning with a bout of frostbite. The doctors wanted to amputate his feet, but he prayed intensely to his Father in Heaven, and within a few days he was able to walk again. [8] By the end of the first winter, he had received the combat infantry medal, which denoted three occasions of close-quarters combat with the enemy.

Paul Prison was called into the national labor force in 1942 and assigned to work on a farm in Bavaria. Back home, he was working as a payroll clerk in a small construction company when he received a notice to report for military service on January 3, 1943. Assigned to an artillery unit, he was trained as a radio man and learned Morse code. A few months later, he was stationed in France. In June 1944, he was a forward observer on the coast of Normandy.

Hans Reger was wounded in Russia in 1942 and spent a year in hospitals recuperating. Then he was sent home and resumed a somewhat normal life as a printer working for the post office. His presence was appreciated by his wife and two daughters, especially when a terrifying air raid took place over Saarbrücken in September 1944. As Sister Reger ran down the stairs with her husband and her elder daughter, Isolde, she was worried about her younger daughter, Ingrid, who was staying with her grandmother just two houses down the street. Fortunately, Ingrid and her grandmother were also able to reach the air-raid shelter, where the five were united. Signal flares were coming down around them, and some structures were already ablaze. When they emerged from the shelter, the scene was totally different; some structures had been destroyed and their own apartment house was burning. In the aftermath of the attack, they learned that they had lost everything but the clothes on their backs. About 90 percent of the city had been destroyed. Hans Reger’s place of employment was also gone, and the family took up temporary residence on the outskirts of town in a building owned by another Church member. Soon they were given permission to move to a town not far from Saarbrücken, where they spent the remainder of the war in the home of Elisabeth’s aunt. They were safe there but totally out of contact with the Church.

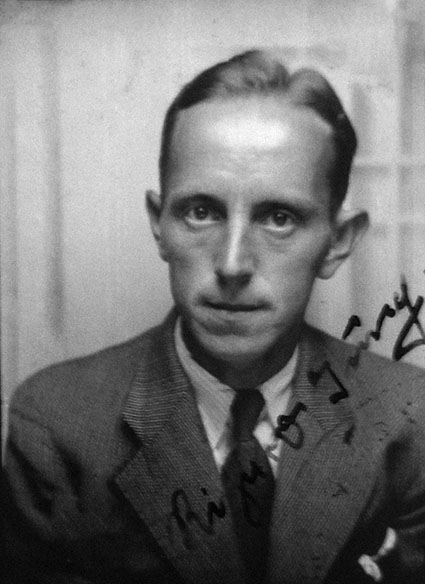

“It’s funny—the things you remember,” said Dieter Jung (born 1937). “Since my dad was a Latter-day Saint he didn’t smoke, so he would trade his cigarette rations for candy bars. When he was at the front, he would send the candy bars back home.” [9] Richard Jung, a tailor, was a social democrat when Hitler came to power, but that political party had a short life under the National Socialist government. He had joined the Church in 1936 and was a priest when he volunteered for service in the Wehrmacht. According to young Dieter, “He volunteered so that Hitler wouldn’t have the satisfaction of drafting him.”

Dieter Jung was only six when he saw his father for the last time. Richard Jung had been sent home after suffering from frostbite on the Eastern Front. Soon after returning to his unit, he was killed. Back at home, his wife, Elfriede, had a premonition that he had been killed and was thus not shocked when two men knocked at her door with the sad news. They presented her with Richard’s personal effects. According to Dieter, “They were sorry that my father had been killed, but on the other hand, he had died for the fatherland, and that’s supposed to be an honor.”

Fig. 5. Richard Jung had a wife and two sons when he was killed in the Soviet Union in 1943. (D. Jung)

Fig. 5. Richard Jung had a wife and two sons when he was killed in the Soviet Union in 1943. (D. Jung)

In 1943, a draft notice arrived for Max Adam. Because both father and son used that name, the family at first feared that the father would be required to serve. However, the call was directed to sixteen-year-old Max, who had been agonizing about serving in the army of an empire he did not support. He described the situation:

I knew that Hitler was bad, period. The Church teaches you one thing and [the Nazis] teach you another. I had a hard time going to war. How could I fight for such a man? I can’t do that! I talked to the [branch president] and he said, “Max, you’ve just got to go!” I said, “But I can’t!” So I was brave enough to go. . . . I prayed for a month about that. Then I got a distinct answer: “Go. You will come home safe.”

Horst Prison was shot cleanly through the calf in Russia in 1943, but he escaped a potentially lethal bullet shortly thereafter despite what he later admitted was a reluctance to listen to the Holy Ghost. He was on guard duty, and somebody told him to take cover. He looked around and could not see anybody. Again he was told to take cover but did not heed the warning. The third time somebody literally pushed him down a hill. At that very moment, a bullet struck his shoulder but did not penetrate his uniform. Had he remained standing, the bullet might have pierced his heart. He never determined who pushed him down that hill, because there was nobody close enough to do so. However, from that time on, he always listened to what others said and listened to the Spirit. That dangerous incident was not his last in Russia. A tank once drove over him while he lay in a trench. After a comrade helped dig him out from beneath the mammoth vehicle, Horst determined that only his watch was broken.

When the Allied forces stormed the beaches of Normandy on June 6, 1944, Paul Prison was atop the slopes overlooking Utah Beach attempting to send radio messages back to his commander. [10] “I couldn’t send the message [at first] because the airwaves were jammed [by music]. Finally, I used Morse Code to send the message. I told them that the invasion had started and they said it was just a bluff.” He and his surviving comrades retreated from the fighting early on because they had quickly run out of ammunition. On August 17, Paul was wounded in three places by mortar fragments—one each in his abdomen, his thigh, and his arm. He made his way to an aid station and was sent to a monastery in Liege, Belgium. He could have died from loss of blood, but an observant elderly physician came to his aid and moved him from the floor onto a bed. After several months in German hospitals, he recovered and returned to his unit in time to celebrate Christmas not far from the area where the Battle of the Bulge was raging.

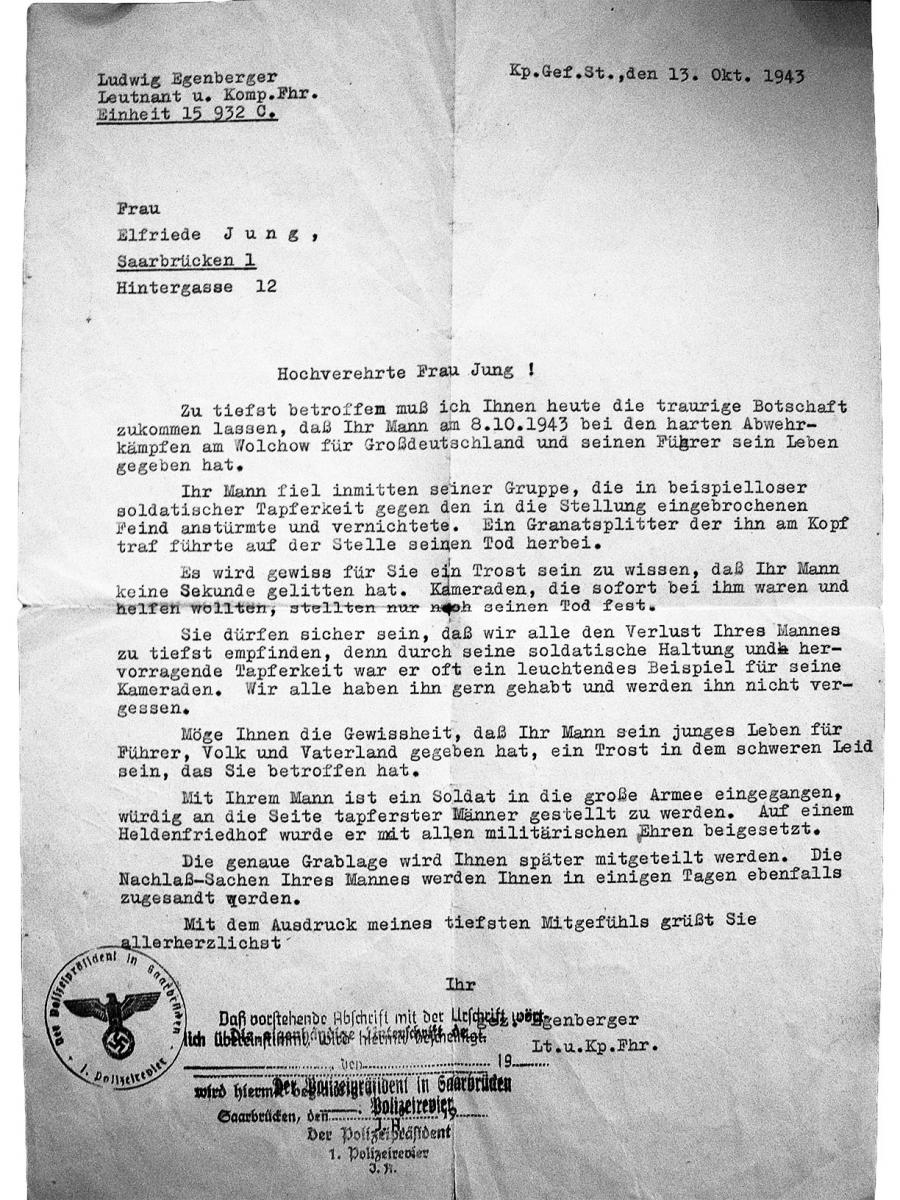

Fig. 6. This letter announced the death of Richard Jung to his wife and their two sons. “You may be comforted by the fact that your husband did not suffer even one second. Comrades who were at his side within moments determined that he died instantly.” (D. Jung)

Fig. 6. This letter announced the death of Richard Jung to his wife and their two sons. “You may be comforted by the fact that your husband did not suffer even one second. Comrades who were at his side within moments determined that he died instantly.” (D. Jung)

Elfriede Jung, now a war widow with two little boys, eventually lost her home in an air raid over Saarbrücken. Dieter, by then seven years old, recalled that the three of them had often gone to the air-raid shelter with their pillows and a few other items. Their apartment house “was totally destroyed—right down to the ground.” His younger brother, Herbert (born 1939), also recalled air-raid experiences: “We went to this big mountain with a cave [as a shelter]. When the bombs hit the mountain, the lights went out. I put my pillow over my head because I thought that would protect me. A couple of days later, we came back out.” [11]

Both boys recalled staying in various towns after their apartment in Saarbrücken was destroyed. For the rest of the war, Sister Jung and her sons were veritable refugees, eventually finding a place to stay in a small Bavarian town near the Austrian border. Harald recalled how the local residents resented taking in refugees: “Nobody wants to have refugees [in their homes], so it was kind of tough.” Dieter recalled being hungry and was therefore quite pleased one day when a farmer gave them a dozen eggs. Unfortunately, a Russian soldier took those eggs and ate them raw. “He was really reprimanded by an officer,” Dieter recalled. While in that town hundreds of miles from Saarbrücken, the Jungs watched the American army come through in a peaceful takeover of the area in the last weeks of the war.

Herbert Jung had the following recollections of the time:

I remember well when the Americans came. They came with their tanks and their trucks and all that. They liked the fresh fruit; they liked their chicken cakes, and they gave us canned goods. So basically that kind of took us away from [our dependency on] the farmers. They liked the fresh stuff; they didn’t like the canned goods. And they gave us chocolates and gum. . . . And then of course we had never seen black people before. Oh, they were something else. We couldn’t believe it. There were no black people in those days in Germany. So that was a big deal for us when we saw those black people.

In January 1945, Paul Prison and his good friend Martin were riding on a truck just a few feet apart when an artillery round exploded nearby. Paul was not hurt, but Martin was struck by shrapnel just below his left armpit. Paul caught him as he fell from the truck. “I couldn’t stop the bleeding,” recalled Paul.

A horse cart came along and we put him in it and took him to the first aid station. By four o’clock the next morning he was dead. Even if he had been on the operating table we couldn’t have saved him. . . . Martin was a very fine person. I always said he was a better person than I am. He was always calm, and he was an altar boy at the Catholic Church, and he really believed in his church and was one of the best men I ever met.

In March 1945, the American army moved through Germany. Elisabeth Klein Reger recalled that there was no fighting when they reached her town and that the conquerors treated the locals with respect. The family soon returned to Saarbrücken, where the French had replaced the Americans as the military occupation force. The Regers were able to rejoin their LDS friends and bring the Saarbrücken Branch back to life. Before long, Hans Reger (who had attended church meetings on many occasions) became the newest member of the Church in Saarbrücken.

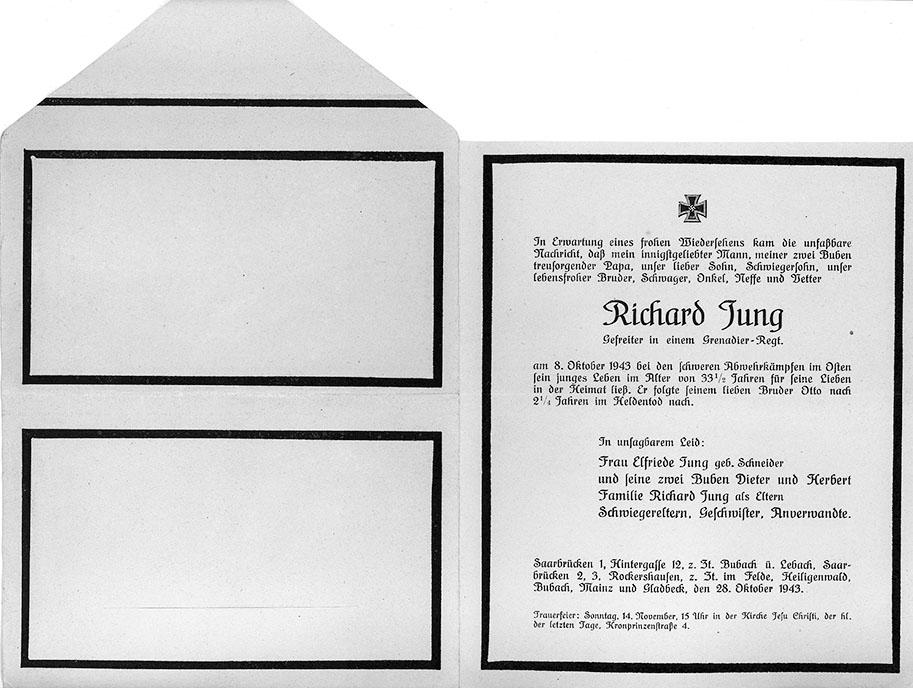

Fig. 7. The standard format for a death notice was still in use in Germany in 1943. A single sheet bore the message and was folded into an envelope. This one was sent by Elfriede Jung to family and friends to inform them of the death of her husband, Richard. The recipient knew by the black border that the contents of the letter would be tragic. (D. Jung)

Fig. 7. The standard format for a death notice was still in use in Germany in 1943. A single sheet bore the message and was folded into an envelope. This one was sent by Elfriede Jung to family and friends to inform them of the death of her husband, Richard. The recipient knew by the black border that the contents of the letter would be tragic. (D. Jung)

In the last months of the war, Max Adam was serving with an antiaircraft battery near the city of Leipzig. As a member of a five-man crew, Max was responsible for setting the vertical angle of the barrel of an 88 mm howitzer as directed. A second crew member moved the barrel left and right. Two other crew members loaded the shells and removed the casings while the fifth member gave the orders. In Max’s recollection, “the men who carried the shells were muscle-men. We had 500 rounds at each station, 250 on the one side and 250 on the other side. We could fire a round in thirty seconds or less. Our duty lasted for two hours, then another crew took over.” No kind of ear protection was used. The howitzer was situated in an area about thirty feet square surrounded by a thick wall of earth.

Max was nearly killed one night while he and his four comrades were off duty. Sitting just a few feet from the howitzer during their two-hour break, they were stunned when an enemy artillery shell landed about ten feet from them. Although there was no barrier between the bomb and Max, he was not hurt but was knocked out. He regained consciousness to find another soldier shaking him and yelling that they had to get out of the area at once; the ammunition supply was on fire. He and his friends were already outside of the enclosure when approximately 125 unused rounds began to explode. “The fire in the air was unbelievable!” he recalled. “That was the first big experience when I was protected.”

Fig. 8. The Reger girls, Isolde and Ingrid, in the ruins of the building in which the Saarbrücken Branch held its meetings before September 1944. (H. Reger)

Fig. 8. The Reger girls, Isolde and Ingrid, in the ruins of the building in which the Saarbrücken Branch held its meetings before September 1944. (H. Reger)

Fig. 9. The building on Kronprinzenstrasse where the Saarbrücken Branch had held its meetings was still a ruin a few years after the war. (H. Reger)

Fig. 9. The building on Kronprinzenstrasse where the Saarbrücken Branch had held its meetings was still a ruin a few years after the war. (H. Reger)

In March 1945, Max Adam was captured by the Americans and was a prisoner of war for three months. “I was in three different camps in three months, and I could not stand it! We sat there all day long with absolutely nothing to do. The soldiers picked fleas out of each other’s hair. That was all we had to do. And wait for a small bowl of watery soup. That’s all we had to eat.”

Paul Prison’s unit retreated slowly through central Germany before the advancing American army. In April 1945, he was captured and transported to a camp by Remagen on the Rhine River. There he lived in squalid conditions that he described as “worse than a concentration camp.” He and his comrades drank filthy water from the river and a dozen men died every day. When they were given small quantities of clean water, they were forced to drink it all at one time, and any remaining water was poured onto the ground by their American guards. For about one week, the prisoners were forced to run up and down hills while being yelled at and beaten by guards. Toward the end of June, Paul was released and transported home to Saarbrücken.

A priest in the Aaronic Priesthood, Paul Prison never met another LDS soldier while away from home. He had lived for three years without reading Church literature, taking the sacrament, or praying with other Latter-day Saints, but he had a testimony and prayed daily. His weight dropped from 152 pounds to 97, but he maintained his allegiance to God and the Church. “We have our own agency; we can have our own testimony and can lose it; that is up to us. I chose to keep it many times. And I wondered why I was still alive; I think it was the hand of God that kept me alive.”

One of the dubious honors accorded Horst Prison as a POW in the Soviet Union was the opportunity to march with thousands of German soldiers through Moscow as the Red Army celebrated its victory over Nazi Germany. The prisoners were starved and mocked as losers in a long and terrible war as they were paraded through the Soviet capital. At the same time, he was likely aware of the sufferings of the Soviet people that had led them to punish German soldiers and civilians long after the war was over.

In June 1945, Max Adam was lining up with other POWs to be released when he realized that the guards might have lied to the prisoners. Instead of being sent home, they might be sent to Belgium or the Netherlands for a year to clean up war damages. Not interested in any such extension of his POW term, he devised a plot to escape. After he successfully sneaked behind the latrines, he managed to scale a ten-foot chain link fence and join a group of POWs who had already been released. When guards checked his papers, he carefully placed his thumb over the area where the release stamp should have been and thus safely exited the camp.

Not far from the camp where Max had made his escape, his parents were living with relatives near the city of Halberstadt. Still just eighteen, he did not expect to see them and was simply walking down the road in the general direction of Saarbrücken (hundreds of miles away) when he heard a familiar voice. It was his father yelling to him from a passing truck. Herr Adam had recognized his son and told the truck driver to stop. As the young soldier recalled, “He jumped [off of the truck] and ran towards me. It was my father. It was a happy reunion, and I had a ride now. We went back to the evacuation town to pick up his suitcases, and then we headed home.” They arrived in Saarbrücken in late May 1945. The first church meeting they attended was held in a school.

Elfriede Jung and her sons returned to Saarbrücken in June 1945. The city was under French military occupation at the time. Dieter recalled a clear distinction between the French soldiers in his hometown and the Americans he had seen in Bavaria: “The French soldiers didn’t have much more than we had as far as food was concerned. American soldiers would treat the kids very nice, give them candy bars and stuff like that. It seemed like they were throwing things away, and we were picking them up and eating them.”

Fig. 10. A German officer ponders his future among the ruins of Saarbrücken in May 1945. (Wikimedia)

Fig. 10. A German officer ponders his future among the ruins of Saarbrücken in May 1945. (Wikimedia)

Until December 31, 1949, Horst Prison suffered many trials as a POW in the Soviet Union. During his more than nine years of military service and imprisonment, he had never had contact with Latter-day Saints except when on leave, which was rare. He had been ordained an elder in connection with his wedding in 1944 and carried his scriptures with him whenever possible, but he never participated in any Church meetings while he was away from home. Nevertheless, he maintained his testimony and his loyalty to God and the Church.

The members of the Saarbrücken Branch had been bombed out and scattered far and wide during the long years of the war and its aftermath, and at least ten of them did not survive the conflict. Little by little, the survivors returned to the city and reconstructed their branch. Peacetime would try them severely as they waited for years to find out whether the province of Saarland would remain in Germany, but their Latter-day Saint lives continued with optimism. [12]

In Memoriam

The following members of the Saarbrücken Branch did not survive World War II:

Harald Ludwig Adam b. Saarbrücken, Rheinland, 27 Jul 1931; son of Max Gabriel Adam and Ella Sophie Adam; d. euthanasia Idstein, Hessen-Nassau, 4 Apr 1939; bur. Saarbrücken 1939 (M. Adam; IGI)

Wilhelmine Biehl b. Saarbrücken, Rheinprovinz, 29 Jun 1875; dau. of Heinrich Biehl and Katharina Greis; bp. 9 Jul 1939; conf. 9 Jul 1939; m. Saarbrücken 12 Sep 1896, Heinrich Paul; d. during the evacuation of Saarbrücken in the Allied invasion 1945 (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, district list, 250–51; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 682; IGI)

Erich Debschütz b. Breslau, Schlesien, 7 Aug 1903; son of Olga Debschütz; bp. 25 May 1920; conf. 25 May 1920; missing as of 1946 (FHL microfilm 68797, no. 523; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 523; FHL microfilm no. 25753; 1930 and 1935 censuses)

Peter Ferdinand Flach b. Ebringen, Freiburg, Baden, 2 Jun 1882; son of Peter Flach and Katherina Graff; bp. 7 Jul 1908; conf. 7 Jul 1908; m. Louise Bach; d. 2 Jan 1941 (FHL microfilm 68797, no. 521; CR 275 8 2441, no. 521; FHL microfilm no. 25767; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Richard Jung b. Saarbrücken, Rheinprovinz, 22 Apr 1910; son of Richard Jung and Elise Georg; bp. 10 or 20 Apr 1934; conf. 10 or 20 Apr 1934; ord. deacon 25 Nov 1934; ord. teacher 16 Feb 1936; ord. priest 3 May 1938; m. 5 May 1934, Elfriede Schneider; 2 children; corporal; k. in battle 3 km east of Dubowik 8 Oct 1943; bur. Sologubowka, St. Petersburg, Russia (Jung; FHL microfilm 68797, no. 575; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Phillippine Knapp b. Frankfurt, Hessen-Nassau, or Mainz, Hessen, 9 Nov 1866; dau. of Margarethe Knapp; bp. 10 Jul 1901; conf. 19 Jul 1901; m. 30 Mar 1887, Ludwig Neuenschwander; 1 child; d. old age 30 Dec 1940 (FHL microfilm 68797, no. 38; CHL CR 275 8 2441, FHL microfilm no. 245241; 1930 and 1935 censuses; no. 38)

Valentin Krämer b. Herrensohr, Rheinland, 15 Jul 1924; son of Valentin Krämer and Elisabeth Lina Rasskopf; bp. 15 May 1933; k. in battle 15 Jan 1943 (IGI)

Richard Friedrich Krämer b. Herrensohr, Rheinland, 31 Dec 1926; son of Valentin Krämer and Elisabeth Lina Rasskopf; bp. 13 Jun 1935; d. 1945 (IGI)

Peter Prison b. Dudweiler, Rheinprovinz, 3 Oct 1867; son of Jakob Prison and Maria Katharina Linnenbach; bp. 7 May 1922; conf. 7 May 1922; ord. deacon 19 Sep 1922; ord. teacher 20 Jan 1924; ord. priest 1 Jan 1934; ord. elder 1 Nov 1936; m. 20 Sep 1890, Theresia Trockle; 8 children; d. pneumonia Dudweiler 19 Dec 1943 (FHL microfilm 68797, no. 42; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 42; IGI)

Johannes Zimmer b. Karlsruhe, Baden, 16 Jul 1921; son of Albert Zimmer and Maria Magdalena Stahl; bp. 28 Aug 1930; conf. 28 Aug 1930; corporal; d. Orleans, France, 15 Jun or 23 Jul 1943; bur. Fort de Malmaison, France (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, district list, 250–51; FHL microfilm 68797, no. 59; FHL microfilm no. 245307; 1925 and 1935 censuses; www.volksbund.de)

Notes

[1] Saarbrücken city archive.

[2] West German Mission branch directory, 1939, CHL LR 10045 11.

[3] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CHL CR 4 12.

[4] Elisabeth Klein Reger, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, July 19, 2007.

[5] Paul Prison, interview by the author, Richmond, Utah, November 22, 2008.

[6] Max Adam, interview by the author, Bountiful, Utah, April 18, 2007.

[7] Harold died in the Kalmenhof Hospital in Idstein (as recorded in the margin of his official birth record in Saarbrücken). The book Euthanasie im Nationalsozialismus by Dorothea Sick (Frankfurt: Fachhochschule, 1983) shows that well over seven hundred persons of all ages were murdered in that hospital and buried nearby. Most murders were done by the injection of lethal drugs, but death was usually not instantaneous.

[8] Horst Peter Prison and Elfriede Deininger Prison, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann in German, April 13, 2009; summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[9] Dieter Jung, interview by the author, West Valley City, Utah, June 20, 2006.

[10] He did not know the name of the landing site until he lived in Utah years later. He and a neighbor (a GI and Normandy veteran) compared descriptions of the area and determined that they had been at the same location, serving in opposing armies.

[11] Herbert Jung, interview by Michael Corley, Salt Lake City, October 30, 2008.

[12] It was not until 1957 that the question of nationality for the Saarland was resolved and France gave up its claims to the valuable territory.