Munich Branch

Roger P. Minert, “Munich Branch,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 280–297.

Titles such as “the Venice of the North” and “the northernmost Italian city” have been applied to Munich because of its architectural beauty and rich cultural heritage. The city has been the capital of Bavaria for hundreds of years. Tracing its beginnings to the end of the nineteenth century, the Church’s branch in Munich was large and vibrant at the start of the war, but Saints were rare in this city of 815,212 people. The branch had fifty-nine priesthood holders and the president, Anton Schindler (born 1873) had already served in that capacity for more than thirty years. [1]

In 1928, the Munich Branch had found nice rooms to rent for their meetings atKapuzinerstrasse18, located about one and one-half miles southwest of the city’s center. [2] The building was a Hinterhauswith only one floor, a former workshop. Elisabeth Grill (born 1914) described the setting:

The rooms were very simple with a small heater in the middle of the main room. One brother always had to come earlier to heat up the rooms and make sure that the smoke would be mostly gone out of the rooms. There was one larger room and a smaller one without a window. It always looked dark. I used that smaller room to teach classes. We had another small classroom. The adult Sunday School class took place in the large room. The rooms were in the back of a building. They always told us to be quiet, to not say anything and to walk quickly and not linger anywhere. The people in the front building did not want to be disturbed by us. [3]

Elisabeth recalled a sign indicating the presence of the Church in that building. She estimated the size of the congregation at sixty to seventy persons on a typical Sunday.

| Munich Branch [4] | 1939 |

| Elders | 16 |

| Priests | 13 |

| Teachers | 16 |

| Deacons | 14 |

| Other Adult Males | 29 |

| Adult Females | 114 |

| Male Children | 13 |

| Female Children | 13 |

| Total | 228 |

BertaWolperdinger(born 1922) recalled the green curtains that hung on the rostrum behind the podium as well as a banner with letters cut from gold paper that read in German, “Prove all things; hold fast that which is good.” [5] That was later replaced by a rhyming motto reminding the Saints to come to church on time:“Fünf Minuten vorder Zeitist des Mormonen Pünkt lichkeit” (Five minutes early is Mormon punctuality). “The children usually sat in the front rows. It was a wonderful atmosphere,”Bertarecalled. “We had pictures of the prophets on the walls, and the chairs could be moved to the sides of the room for other activities.” [6]

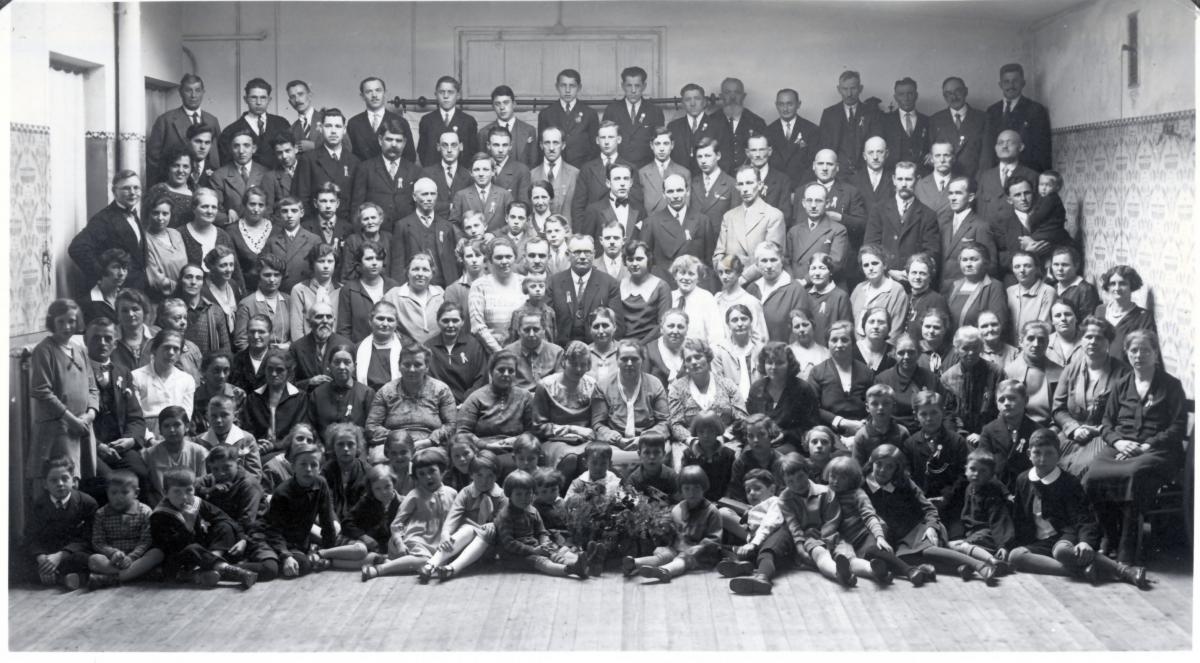

Fig. 1. Members of the Munich Branch a few years before the war. (M. Behrens)

Fig. 1. Members of the Munich Branch a few years before the war. (M. Behrens)

Berna Probst (born 1926) recalled that a Brother Mathes changed the sayings on the wall now and then. One of the sayings he displayed was “The Glory of God Is Intelligence.” She also remembered that a Brother Westermaier was in charge of the cloak room; with his wooden leg (a reminder of the Great War), he was always in a hurry to keep up with the members as they arrived and handed him their coats. [7]

Fig. 2. American missionaries visiting the Nussbaumer family in late 1938. (C.Hillam)

Fig. 2. American missionaries visiting the Nussbaumer family in late 1938. (C.Hillam)

The counselors to Anton Schindler when the war began were Ludwig Vikariand August Burkart(who also served as Sunday School president). Anton Vikariwas the president of the YMMIA and Paula Leypoldthe president of the YWMIA. Marie Lerchenfeldled the Primary organization and Anna Wienhausen the Relief Society. Rudolf Netting served as the branch genealogical consultant and the Stern subscription coordinator.

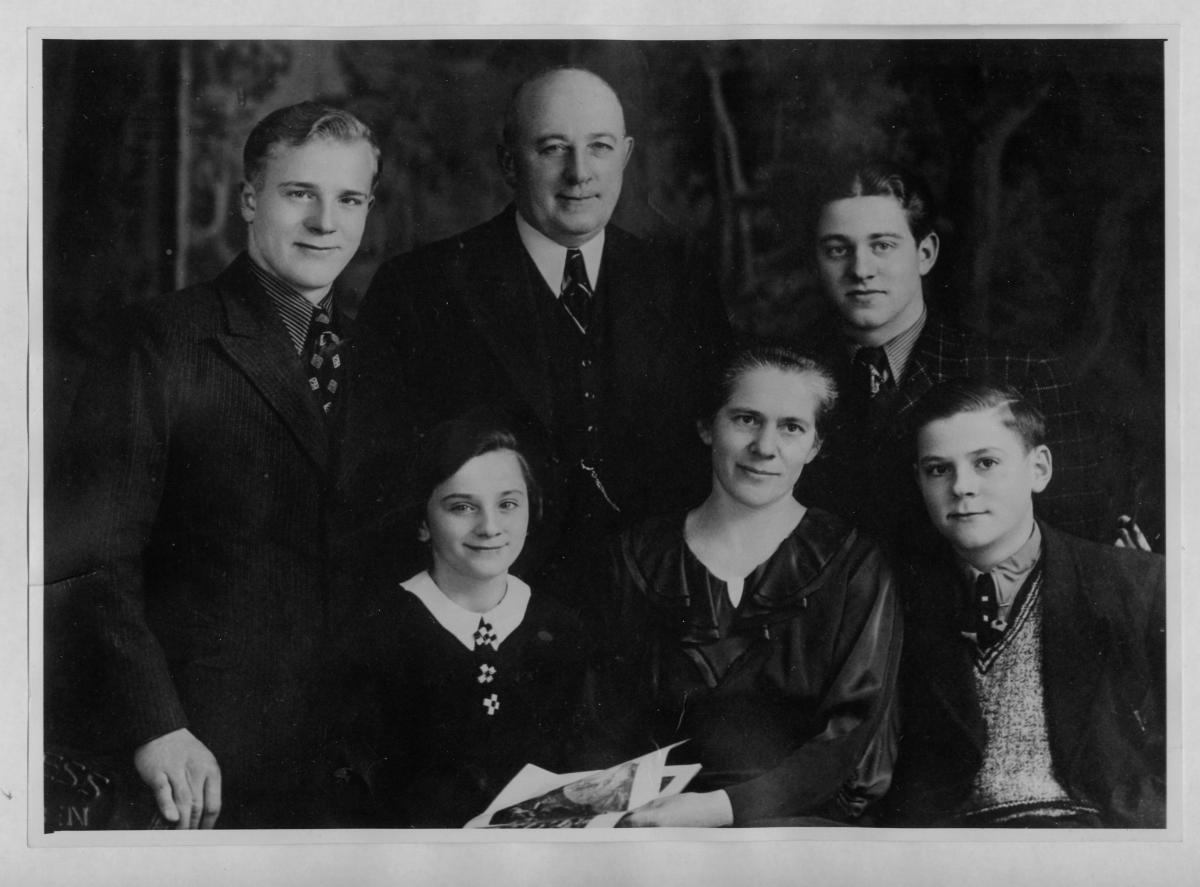

Fig. 3. Anton Schindler served for decades as the president of the Munich Branch. (M. Behrens)

Fig. 3. Anton Schindler served for decades as the president of the Munich Branch. (M. Behrens)

As was the case in nearly all German branches, the Sunday School in Munich began at 10:00 a.m. Sacrament meeting began at 7:00 p.m. [8] The Primary met on Mondays at 3:00 p.m., and the Relief Society met that evening at 7:30 p.m. Mutual meetings took place on Wednesdays at 8:00 p.m., and the genealogical class met after Sunday School on the first Sunday of the month.

“My parents and I were all baptized on August 20, 1939, in the suburb of Unterhaching in a public pool,” recalled Berta Wolperdinger. “We had to pay a fee to enter. The ceremony started at 6:00 a.m. before the public was admitted to the facilities. We were also confirmed that day at the same place.” This baptism story reflects conditions all over the West German Mission at a time, since only three branches had a baptismal font in their meetinghouses.

American missionaries participated in that baptismal ceremony, but just six days later, they were gone—evacuated from Germany. Berta recalled that the atmosphere was uneasy even before the missionaries left Munich. “We felt that war was inevitable in 1939, and some bomb shelters had already been prepared.”

Fig. 4. Berta Wolperdinger (front row, third from left in the overcoat) was baptized just twelve days before the war began. (B. Wolperdinger)

Fig. 4. Berta Wolperdinger (front row, third from left in the overcoat) was baptized just twelve days before the war began. (B. Wolperdinger)

The Habermann family of the Munich Branch traveled to Sunday church meetings in much the same way as LDS families all over Germany did. Gustav Habermann (born 1922) provided this description:

We lived in the Nussbaumstrasse 12. It took us about twenty minutes to walk to church. There was no other transportation available. We got dressed early in the morning and always went to church with our widowed mother. After Sunday School, we walked home and went back later for sacrament meeting. Our neighbors knew that we went to church. It was normal to go to church on Sundays for all of us—Catholics, Protestants, Mormons. [9]

Erna Probst recalled that her parents, Johann and Thekla Probst, were not at all enthusiastic about the Nazi regime under which they lived. She had no interest in the League of German Girls, and her parents supported her in avoiding involvement with the group. The Probsts were concerned that their three sons would become victims of the war. Sister Probst was even bold enough to make negative statements about Hitler in public, but her husband constantly reminded her of the dangers of such talk.

As soon as Thekla Probst heard that war had been declared, she sent her daughter Erna to the store to buy anything she could find. According to Erna:

She explained that we couldn’t know how long the situation would last so we needed to prepare. I then went and got sugar and flour and whatever I thought we would need. It was interesting for me because I didn’t understand at all what it meant to be in a war, or why my brothers had to leave to serve in the war and why I, in the end, had to leave also.

Just after the Polish campaign ended victoriously on September 21, 1939, Gustav Habermann decided to join the army. He recalled:

Before I volunteered for the service, I thought about how I didn’t like hearing that whatever Adolf Hitler said, everybody had to obey (Führer befiehlt, wir folgen!). I knew that I would be drafted when I turned twenty-one and I wanted to choose for myself where I was assigned. My goal was to serve in the paratroopers, but I ended up in the air force. I received my basic training in a period of three months and then worked as a technician for airplanes. The basic training was in Flensburg.

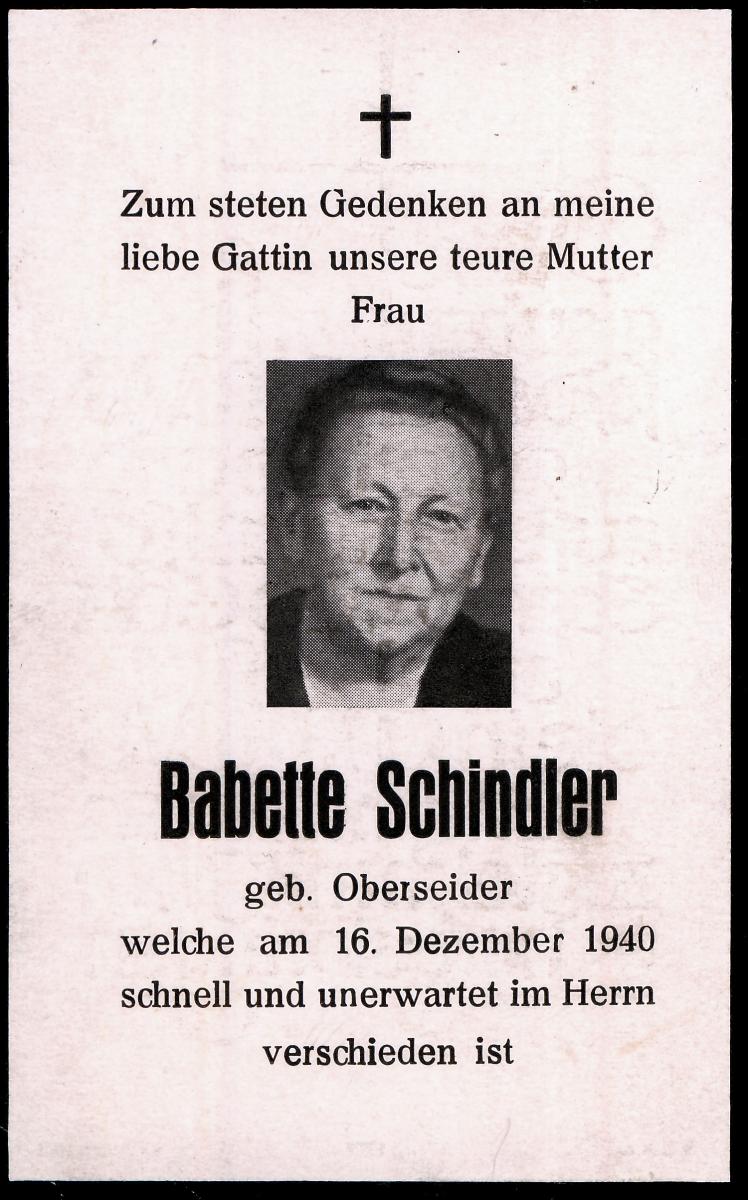

Fig. 5. Branch president Anton Schindler lost his dear wife in 1940. In the final war years, resources for such formal death announcements were no longer available. (M. Behrens)

Fig. 5. Branch president Anton Schindler lost his dear wife in 1940. In the final war years, resources for such formal death announcements were no longer available. (M. Behrens)

The family of Josef and Philomena Hörner had gone through severe trials even before the war started. A veteran of the Great War, Brother Hörner was a political malcontent and had gained many enemies in high places by the time Hitler came to power. During the Nazi era, the police were constantly on his trail, hoping to find a crime for which he could be tried and imprisoned. To add to his woes, he had an extramarital affair and was excommunicated from the Church. [10] During the 1930s, his family was not seen in church very often, but by the time the war began, Josef was attending meetings again. His son, Georg (born 1926), recalled the pressure his father’s activities put on the family, especially Georg’s mother:

When the police came to get him, he would hide in the bushes or in the forest. Then my mother would send my older sister to him with some food. He often came home during the night and we heard our parents talking. But at around 2 a.m., the police would come in and my father had to hide. They would have killed him before our very eyes if they could have. When the police asked us during the night where our father was, we did not say anything. . . . Often, my father would climb out the window when the police came in, and they would look for him but could not find anything. When they were gone, my mother would open the window or knock, and my father was able to come back in again. . . . For us children it was a horrible time seeing our father like that. [11]

In the fall of 1940, Josef Hörner “was tired and in such a bad condition that he no longer cared what happened,” according to Georg. He was caught in his home and thrown down the stairs while neighbors watched. Not long thereafter, he was sent to the Mauthausen Concentration Camp near Linz, Austria. Georg’s account of his father’s demise continued:

It did not take long before a letter came saying that my father had died of pneumonia. They also said that if we wanted his ashes, they would send us the urn. We did that but we knew even then that the ashes could have been from many different people. We buried the urn by the grave of my brother Joseph, who had died while a member of the Reichsarbeitsdienst before the war.

The German government believed it necessary to thoroughly indoctrinate every boy and girl, including Rudolf Strebel (born 1931). He had this recollection of the program:

When I was ten years old, our class was drafted into the Jungvolk. We got the uniform and participated in the activities. We saw it as part of normal schooling but we didn’t necessarily like it. We had to run a lot. For me, it wasn’t much fun. We marched in the parades but never did anything like camping. They did teach us about Hitler and the National Socialist ideals, but that happened in a non-compulsory manner. We made the commitment right at the beginning that we would never miss a church meeting because of a Jungvolk activity. Sunday was my Church day. All other days, I would be available. I never got into trouble because of it. [12]

Fig. 6. This Munich Branch photograph was taken at the rear of the main meeting hall. (E. Probst Höhner)

Fig. 6. This Munich Branch photograph was taken at the rear of the main meeting hall. (E. Probst Höhner)

The meeting rooms at Kapuzinerstrasse 18 were lost relatively early in the war. An air raid in 1941 totally destroyed the building, and the Saints were compelled to seek other meeting venues. [13] Elisabeth Grill recalled meeting for a while on Hebelstrasse and also on Reisingerstrasse. In each location, only one room was available. According to Berta Wolperdinger, “We would find out each Sunday where the meetings would be held the next week.”

Elisabeth Grill was an employee of an insurance company that had offices at Goetheplatz in Munich. As the only Latter-day Saint in that office, she was often asked about her faith. The other employees were Catholic and complained about the church tax they paid. [14] They wondered how she could afford to pay tithing on her meager salary. As she recalled:

They tried to get me to drink coffee and would say that just one drink would not make any difference. But I told them that one drink would also not benefit me at all. Then they quit trying. When we celebrated something like Christmas or birthdays, they were very considerate and would offer me a glass of juice instead of champagne or wine.

Fig. 7. The rostrum at the end of the main meeting room was used on many occasions for theatrical performances. (E. Probst Höhner)

Fig. 7. The rostrum at the end of the main meeting room was used on many occasions for theatrical performances. (E. Probst Höhner)

Erna Probst recalled what her family knew about the situation of the Jews in Hitler’s Germany:

My father worked at the local railroad station so we always lived close to it. The trains that took people to the concentration camp in Dachau always passed our house. The prisoners had to work in Munich and wore striped suits and hats. My mother would often say that she had to go shopping and would cut some bread and take it with her. She passed the trains and would give the bread to the prisoners. My father was so scared that she would get caught.

Alfred Gerer (born 1934) was the youngest child of the family of Josef and Barbara Gerer; he watched as his older brothers left for military service. He recalled how his widowed father learned of the death of his son Lorenz at Stalingrad, Russia, in December 1942, when the German Sixth Army was encircled and destroyed:

A man came to our home with a telegram. My father knew that a telegram could only mean one thing. And that’s what it was. It said that my brother Lorenz died in Stalingrad and that his body would remain there. It also told us that they could not send anything back except his medals. The message hit my father very hard. We held a funeral service in the branch with his picture displayed. [15]

As the war dragged on, the building in which Elisabeth Grill’s insurance office was housed was damaged and working conditions became challenging: “We also didn’t have stairs anymore, but we used a simple ladder to get to the second floor. To heat the rooms, we used a small oven. The broken windows were covered with simple cloths. It was difficult and not very pleasant to work under those circumstances.”

Air raids experienced at home were not pleasant either. Elisabeth Grill explained that the public shelter was too far away from the family’s apartment and would likely have been full by the time they arrived, so the residents of her building simply went downstairs into their basement. The building suffered damage to windows and doors, but the damage was minor compared to the house across the street, which was totally demolished. “If our building had suffered a direct hit, we wouldn’t have survived,” she concluded.

Berta Wolperdinger also experienced most air raids in the basement of her home. Her father had built a small house in the suburb of Taufkirchen, six miles south of Munich. Just a few yards from the local railroad station, the house was in danger of being bombed every time the trains were attacked. “I remember that when our windows burst, we had glass all over our beds,” Berta explained.

Political speeches over the radio were daily fare in Germany during the war. Georg Hörner recalled how he watched police officers clear the sidewalks just before a broadcast, so that nobody had an excuse for missing a speech: “Whenever Hitler spoke, we got time off of work and we were required to listen to the radio.” Before his arrest, Georg’s father had listened to such broadcasts; he had even told Georg that Hitler was not such a bad man but that there were “lots of little Hitlers” around who were bad.

Alfred Gerer of the Munich Branch was certainly not the only boy who did not fully understand why wars are fought, as he recollected: “When the war started, I didn’t understand much of it. But for a boy my age, it also had an adventurous aspect.” His story continued:

My father was responsible for all the people in our house during an air raid. He had to make sure that all of us were in the basement or a shelter. He didn’t manage to do that with me. I went back outside all the time to watch the American planes drop their “Christmas trees” [illumination flares used to mark bombing targets]. Very close to our home was a factory that produced all kinds of tires [Metzler Gummiwerke]. I knew that the Americans wanted to get that factory. For me, it looked like the finest fireworks. When my father found me, he grabbed me by the ear and dragged me downstairs again.

Alfred was caught between religious loyalties when his widowed father married a Catholic woman. She had no children of her own and did not wish to go to mass by herself, so she added a few cents to Alfred’s allowance to persuade him to go along with her. He wanted the money, and she enjoyed showing off a boy who appeared to be her son.

The family of Anton and Ursula Roggermeier lived in the eastern Munich suburb of Berg am Laim. The area was quite rural in those days and their son, Herbert (born 1936), enjoyed the fact that his mother’s parents owned a dairy just a short distance from his home. He went there on his way home from school each day to spend time with his grandparents and a variety of animals. “I came home late sometimes, but my mother always knew where I was,” he recalled. [16] Herbert saw very little of his father, who was drafted in 1939. As an artist and interior decorator, Anton Roggermeier was not well suited for combat. Perhaps the Wehrmacht recruiters recognized this, because he was assigned to serve as a fireman at airfields. His son recalled that Anton was stationed in Munich, Vienna, Romania, and France. Fortunately, he was never wounded or otherwise damaged by the experience of military service.

Fig. 8. TheThallerhome in the Munich suburb ofSollnin about 1940. (W.Thaller).

Fig. 8. TheThallerhome in the Munich suburb ofSollnin about 1940. (W.Thaller).

District president Johannes Thaller purchased a home for his family in the southern Munich suburb of Solln. His son Edwin (born 1938) described the setting:

My father bought a house just outside of Munich in a wealthy area in 1939. (It wasn’t a new house.) He hired a maid. The house was large enough to have all the members of his family live in it. We also had a double-car garage with a sliding door. We were able to keep our own chickens on a one-half-acre piece of land adjacent to the house. The house was a single family home with four bedrooms and one and one-half bathrooms. We had a living room, a kitchen, a family room, and an office. We had very comfortable living standards as far as everything goes—we had a refrigerator, a telephone, and an electric stove. [17]

Testimonies of eyewitnesses allow the assumption that Elder Thaller was pleased to share his resources and talents with Church members and nonmembers alike. In 1942, he moved his family to the Austrian town of Haag am Hausruck. The LDS branch president there, Franz Rosner, found them a place to stay in the building in which the branch held its meetings. Life in Munich had become very uncertain, and thousands of people were leaving the city. The Thallers moved back into their home in Solln in the last year of the war.

By the middle of 1943, Georg Hörner had left home for northern France. “After that, I didn’t have any contact with the Church until after the war.” As a Hitler Youth member, he had been trained to use a rifle, but he was not required to use weapons during the war. He spent his first months of service in France, and things were quiet there, but such peaceful conditions would not last long.

According to Rudolf Strebel’s recollection:

We had constant air raids from 1943 to 1945. The Siemens electrical factory was located just about two blocks away from us, which meant that we lived in a targeted area. When an air raid happened, we went downstairs into the basement. It was fortified with the ceiling having extra supports. We also had break-out sections in the walls just in case we needed to climb through into the building next to ours. I remember that a bomb hit the hill in front of our apartment house once and part of the roof came off. But nothing happened on our side of the building, which was on the opposite side. During that attack, we had all of our windows open and nothing happened to them. But the people who had theirs closed came home to broken windows.

Fig. 9. Max Grill of the Munich Branch was one of the hundreds of German Latter-day Saint men who were killed before they could become husbands and fathers. (E. Grill)

Fig. 9. Max Grill of the Munich Branch was one of the hundreds of German Latter-day Saint men who were killed before they could become husbands and fathers. (E. Grill)

Due to the increased danger of living in Munich, Rudolf Strebel was evacuated with his entire school class of boys to the Alpine town of Bad Reichenhall. As part of the Kinderlandverschickung program, he stayed there for eighteen months, with infrequent visits from his mother. Rudolf had the following to say about his time away from home:

Every three to four months, I was able to go home. I was very homesick during that time—I was still so young! It took us about two hours to reach home when we used the train. [In Bad Reichenhall] we could often see the [American] bombers flying towards Munich. We also heard some pounding in the far, far distance. [Munich] was about 100 miles away. There weren’t any other larger targets around us, so we knew they wanted to attack Munich.

On a few Sundays, Rudolf took the train to Salzburg, just seven miles distant. “I wasn’t totally isolated from the Church. I couldn’t go that often, but if I had the chance, I would. That was maybe once a month or so. The members were so kind and took me in for dinner. [But] they didn’t come to Bad Reichenhall to visit me.”

Gustav Habermann’s military service took him to stations all over Europe. After being trained in engineering in Bernburg, Germany, he learned to fly in Danzig, Germany, but never flew in combat. While in Danzig, he met the girl he eventually married. (She was a Lutheran, which did not please Gustav’s mother back in Munich.) [18] Although there was a large and active branch of the Church in Danzig at the time, Gustav did not attend meetings there. He explained the situation in these words:

I did not think about the Church at all during that time. I was not yet a Priesthood holder and did not carry scriptures with me. While being isolated from the Church during my military service, I did not have a testimony of the Church yet. I did not pray and even doubted that there was a God. I drank alcohol as a soldier, and I also started smoking but stopped when I got home after the war.

Unfortunately, in Danzig, Gustav made the mistake of refusing to get out of bed one day. “I told the officer I didn’t want to get up, so they took me to a court-martial, and I was given a punishment of six weeks at the front.” After surviving that experience, he was trained in the Netherlands to drive a tank and from there was transferred to Italy and finally to the Eastern Front. By 1944, he was engaged to be married.

A young adult during the war years, Berta Wolperdinger admitted that life offered very little entertainment in those days: “There was no opportunity for us to go out and have fun. It was dangerous to go out during the evening. If we went downtown with the streetcar, we didn’t feel very safe. Everything was dark. All my friends lived in other villages, and we were all scattered.” The daily chores also left little time for amusement: “We went grocery shopping with the food ration cards. We also owned some property on which we could grow things, and that helped get us through the war. It was nothing much, but we always had fruit and vegetables. We still had our problems, but it wasn’t as severe as if we had had to live on the ration cards.”

By the time Herbert Roggermeier was old enough to attend school, the war in Europe was well under way. Regarding the possibilities of enjoying life as a boy at such times, Herbert had the following comments:

During the war, I played with my school friends a lot; we liked to play soccer. But we could never play very long because we had to go home very quickly when an alarm went off. Also, the school was next to a huge antiaircraft battery. If there was an alarm while we were in that area, we ran home immediately; we knew what we had to do. . . . There was no situation in the war when I thought that I would die. I was a child, and children don’t take things like that too seriously. But I had to sit in a shelter and realized that bombs were being dropped on my city.

On June 8, 1944, Erna Probst was inducted into the national labor service and sent to the town of St. Stefan in southern Austria. Because her leaders thought her physically frail, they assigned her to work in a storage area rather than on the farm. She stayed there until the harvest was finished in October and then was transferred to Vienna. In Austria’s capital city, Erna was assigned to be a night watchperson. During the day, her unit was to monitor enemy air traffic and report on the number and types of planes flying over. She was also fortunate to attend church with the Vienna Branch on one occasion. She recalled:

I liked my time there because we girls were a fun group, but I didn’t like the fact that we had to stay there over Christmas. Near the end of the war, we heard that the Russians were coming closer. We were then trained in marching during the day and night and even got special boots for that. Then, we heard that we had to leave Vienna and we walked [120 miles west] to Linz.

In the last years of the war, life became increasingly difficult, as Elisabeth Grill described: “Sometimes the electricity wouldn’t work, or it would be turned off. It was the same with gas and water. We began to store water in case it was turned off. We were often very cold because there wasn’t enough wood or coal. We couldn’t even go out and get wood anywhere. I collected pine cones from the ground around trees.”

The lives of Munich residents were not just in peril when air-raid sirens were wailing. As Elisabeth recalled, one could be killed just walking through town. On one occasion, she was crossing a long railroad bridge when enemy dive-bombers flew over. Fortunately, they did not return to drop bombs on the trains rolling along below the bridge. “I was very scared, but I didn’t feel as if I was going to die,” she recalled. “I had many spiritual experiences during the war, and those kept me in the Church.”

After the Allied landing on the coast of Normandy in June 1944, Georg Hörner’s unit of the national labor service was moved slowly away from the advancing battlefront. As the enemy pushed eastward, Georg marched through northern France to the Netherlands and on to Cologne on the Rhine. From there he was transferred to central Germany near Halle and Leipzig. When the city of Dresden was destroyed in the terrible firebombing of February 13–14, 1945, Georg was just a dozen miles away, working at the Leuna factory. Because he was never officially drafted into the Wehrmacht, he was not required to confront the enemy invaders and was not classified as a prisoner of war at the conclusion of the conflict.

Trying to stem the tide of invasion from the east was essentially impossible for the Wehrmacht in the spring of 1945. Gustav Habermann was stationed near the Baltic Sea and—like thousands of his comrades in the German army—he wanted nothing other than to make his way west before the Soviets could capture him.

I decided to take a ship, but it was harder to get on the boat than I thought. I saw a soldier who was severely wounded and I took him with me on a small boat so that we could reach the larger ship. They allowed us to board and we sailed to Stettin. I got off of the ship in Stettin wearing a jacket with the word Flak [antiaircraft] on it. They had told us that men with that assignment were allowed to leave the ship first, and that’s what I wanted. When a ship is full of soldiers, nobody really knows where anybody belongs. From Stettin, I made my way to Berlin.

A few months before the end of the war, Dorothea Strebel went to Bad Reichenhall to pick up her son. The Hitler Youth leaders did not wish to let him go, but she exercised her rights as a parent and took him home to Munich. Rudolf recalled that after his return home, the branch held meetings in the German Museum. “On our way to church after air raids, we saw many areas destroyed. But we took our bicycles anyway and went to the meetings.”

Returning from Austria to Solln, the Thaller family had to deal with the increasing frequency of air raids in their suburb. An antiaircraft battery had been set up just a few hundred yards from their house and the guns relentlessly fired at enemy aircraft. On one occasion, an airplane was shot down and landed not far from the house. According to young Werner, the plane’s motor was detached and struck the ground next to the house; the impact cracked or broke every window. “It was so close that I could touch the house with one hand and touch the motor with the other hand,” he recalled. [19]

Werner’s brother, Edwin, had similar memories:

One night after an air raid, we picked fifty [incendiary] bombs out of our yard and our house. [20] One went through our tile roof into my mother’s bedroom and closet. It started burning there [but we extinguished it]. They were similar to phosphorus bombs—you couldn’t put them out with water but had to use your hands or blankets. One also hit our car, and it burned out. Luckily, our second car was still intact.

The Thallers were typical Germans in that they were always on the lookout for neighbors who needed help during air raids. Werner described the conditions in these words:

There’s no way you could call a fire department or anything because it just wasn’t available. Once we saw flames coming out of our neighbor’s roof, so we went over to alert them and found them huddled down in their basement. But because we were alert, awake enough to see, we were able to save them and their house and get the fire put out. The house on the other side of them was a small wooden house and it got hit, but it burned before we could do anything to stop it.

Erna Probst arrived home from Vienna in early March 1945. She already knew that their apartment building had been damaged extensively in an air raid, but her parents had managed to find rooms to live in next door. She remained in hiding for the next few weeks, because she was officially required to report for duty again but had no desire to do so. Fortunately, her neighbors did not report her disobedience, and her father burned her Arbeitsdienst uniform.

Fig. 10. The family of JohannProbstwhen the war began. (E.ProbstHörner)

Fig. 10. The family of JohannProbstwhen the war began. (E.ProbstHörner)

“Our home was destroyed in the last attack on Munich,” recalled Alfred Gerer. The event was almost tragic for his family, as he explained it:

I was sitting in the basement next to my father and his wife. First, we heard the sounds, but then it was like everything moved in slowmotion. Some cracks appeared in the walls, and then everything fell apart. Everybody was running towards the hole in the wall [to the adjacent building], which was too small for everybody at once. All the people made it through the opening except for my father’s wife. She was a bit larger than everybody else, and she was stuck in the ruins of our basement. We all got shovels and got her out of there. We also poured water over her, which was in buckets everywhere [to prevent burns]. When she regained consciousness, her first words were: “The meatloaf is still in the oven.” My father told her that she did not have to worry about that anymore. She was not seriously hurt.

When the fires died out, Alfred returned to the ruins to search for a personal treasure: “I was the only boy in the neighborhood who had a film projector, and I was looking desperately in the ruins. It was very dear to me. I never found it. We had lost everything in the ruins.”

On March 20, 1945, the American army entered Munich under peaceful conditions. The surviving Saints wondered what kind of treatment they would experience at the hands of the conquerors. According to Berta Wolperdinger:

It was not always a nice situation. They occupied whatever rooms they wanted. We could not sleep very well anymore because it was such an uncomfortable situation. The first night they were there, they came into our house. We were all so tired, and we did not think that they would take things away from us. But they did. I guess other soldiers did the same. . . . I always carried my watch with me because it was a keepsake. That night, I put it on the nightstand and they stole it. But they kept everything else in order and did not destroy anything. They also did not molest us.

“The Americans came down our street and stopped to have lunch,” recalled Rudolf Strebel. “Then they moved on. There wasn’t any fighting; the German troops had already left. . . . We hung out white sheets, but in reality it wasn’t even necessary. Two or three days later, they looked through our homes for weapons or soldiers, but that was all.”

The Gerer family moved to the suburb of Allach in northwestern Munich after they lost their home. The Dachau Concentration Camp was just a few miles to the north, and conditions in the area became very insecure when inmates of that camp were released at the end of the war. According to Alfred, “They came into our house and took our jewelry. I was scared of the prisoners since they had a feeling of revenge inside, but I was not scared of the American soldiers.” For the duration of the war and for some time thereafter, the family took the train to downtown Munich on the way to church. Josef Gerer was a railroad employee, so they rode for free. Church meetings were still being held every Sunday.

Fig. 11. HerbertRoggermeierof the Munich Branch was baptized in 1944 in this idyllic stream inTaufkirchen, a suburb six miles south of the downtown. [21] (R.Minert, 2008)

Fig. 11. HerbertRoggermeierof the Munich Branch was baptized in 1944 in this idyllic stream inTaufkirchen, a suburb six miles south of the downtown. [21] (R.Minert, 2008)

Herbert Roggermeier remembered the day the Americans entered the suburb of Berg am Laim: “We children thought it was cool that they came in Jeeps. We ran towards them. They gave us Hershey’s chocolate and bubblegum. There were both black and white American soldiers. I didn’t know . . . even how to eat a banana. I would have eaten it with the skin.”

Next to Herbert’s grandparents’ home was a prison, and his grandmother often threw bread or other food over the fence to the prisoners. After the war was over, the former prisoners found some guns and, according to Herbert, “stood in front of the dairy and made sure that nobody came to do any harm to it. The prisoners were from Eastern Europe—Ukraine and other countries.”

The war was over, but new challenges and adventures presented themselves. Young Werner Thaller recalled one that is common in many cultures:

There was an instance when one of us kids picked up a pack of cigarettes; we saw [American] soldiers driving or walking by and smoking, so we thought that’s the thing to do. We got us a match and sat down out behind our house. As a group of neighborhood kids, we passed the cigarettes around and lit them up. And of course, Mom found out and she got upset and took them away. She told Dad, and he took us into a room. Back in those days, the punishment was always a belt or a wooden spoon or something. So before Dad even began to us, we started crying. So mom came in and said something to Dad. I don’t know what she said, what she whispered in his ear, but Dad all of a sudden put the wooden stick down and he knelt down with us and we had a word of prayer.

The Probst family had previously discussed possible outcomes of the war. Erna’s father, Johann, had indicated that conditions in Germany would be worse if Hitler were victorious and that he wanted to take his family to Ukraine if that happened. According to Erna, “We were not scared of the Americans and they didn’t do anything at all to us.” All three of Erna’s brothers had been drafted, and her parents were delighted when they came home. Ernst and Ludwig returned soon after the war’s end, but Sebastian did not come home until 1947. Suffering from a serious lung ailment, he needed surgery and a long hospitalization period before he could recover.

By May 1945, Gustav Habermann had been transferred into occupied Czechoslovakia and was serving with a tank unit. When the men heard that Hitler was dead and the war over, they were told to head for home any way they could. Gustav’s crew initially loaded a tank with food and planned to drive it to Germany but soon decided it was better to split up. “On my way [to Berlin], none of the Russians bothered me. All they took away from me was a ring and my watch. They left me my engagement ring. I saw a jacket on a scarecrow and took it so that I would look different. I tried to make them think I was an Italian. I was on my way to Berlin because I had heard that if I went to Munich the Americans would make me a prisoner of war.” Arriving safely in Berlin on May 20, he located his fiancée, and they were married in the Soviet occupation zone in June.

At the end of the war, the branch members still alive and still in town gathered for meetings in rooms of the Deutsches Museum on the Museum Island in the Isar River in downtown Munich. Few members of the Munich Branch were still in the city by then. As Berta Wolperdinger explained, “When the war began, our branch was very close and we saw each other very often. But as the war continued, we felt more and more torn apart.” By the spring of 1945, many families were still living as evacuees in rural communities, and more than sixty of the members had been killed or had died of other causes.

Fig. 12. The building in which the Munich Branch met during the first years of the war stood adjacent to theHinterhausseen at the left in this picture. No structure has been built at that location since the war. (R.Minert, 2008)

Fig. 12. The building in which the Munich Branch met during the first years of the war stood adjacent to theHinterhausseen at the left in this picture. No structure has been built at that location since the war. (R.Minert, 2008)

In May 1945, Rudolf Strebel had never known any government but the Hitler regime. However, he understood that some aspects of life in Nazi Germany had not been good:

We were glad when the system broke down. We were free again. There had always been a certain pressure on us—what we were allowed to say or do. I knew of one family where the woman was lying on the floor, crying her heart out, because what she had believed in wasn’t there anymore. She was really a fanatic national socialist.

The once beautiful city of Munich lay in ruins. At least six thousand people had been killed in seventy-three air raids, and fifteen thousand more had been injured. Twenty percent of the city was totally destroyed, including more than seventy-six thousand apartments. [22] In addition to the sufferings of the populace, thousands of refugees from eastern Germany had come to Munich and were competing for housing and food.

Fig. 13: In the last days of the war, the Munich Branch was meeting in a lecture hall of theDeutschesMuseum in Munich. (R.Minert, 1973)

Fig. 13: In the last days of the war, the Munich Branch was meeting in a lecture hall of theDeutschesMuseum in Munich. (R.Minert, 1973)

The Munich Branch had been scattered to the four winds, and the losses of property and life among the members were among the worst in the West German Mission. Nevertheless, eyewitnesses insist that meetings were held somehow at whatever locations became available and that the spirit of the gospel did not diminish through those challenging and often sorrow-filled years.

Erna Probst summed up her church experiences during the war in these words:

We had a wonderful branch before, during, and after the war. I always loved going to church, and I liked the talks and the music. We had a wonderful choir, also. When somebody died in the war, the funeral services were extraordinary. There was a large picture of that person on a table on the podium surrounded by flowers. And then we held a sacrament meeting in that person’s behalf. I know we did that for Ludwig Lang, Edwin Thaler, and Otto Scharmbeck.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Munich Branch did not survive World War II:

Richard Amerseder b. München, München, Bayern, 4 Aug 1927; son of Karl Amerseder and Amalie Hubauer; bp. 28 Sep 1940; conf. 28 Sep 1940; ord. deacon 6 Jun 1943; k. in battle Romania or d. dysentery in a field hospital Focsani, Romania, 13 Aug 1945; bur. Focsani, Romania (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 305; CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, all-mission list, 1943–46, pp. 186–87; CHL 2445, no. 10; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 943; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Georg Bader b. Altfreimann(?), München, Bayern, 30 Jan 1900; son of Georg Bader and Anna Walter; bp. 25 Jan 1930; conf. 25 Jan 1930; ord. deacon 14 Dec 1930; ord. teacher 24 Jan 1932; ord. priest 26 May 1935; ord. elder 10 May 1937; m. 2 May 1931, Magdalene Rietzl; d. stroke 7 Jun 1943 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 13; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 634; IGI)

Alma Peter Bartl b. München, München, Bayern, 19 Feb 1912; son of Andreas Bartl and Walburga Adler; bp. 28 Feb 1920; conf. 28 Feb 1920; ord. deacon 2 Oct 1932; ord. teacher 12 Nov 1933; m. 3 Jun 1933, Magdalena Pitrak; missing as of 20 Aug 1946 (CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 16)

Elisabeth Bausch b. Eningen, Schwarzwaldkreis, Württemberg, 17 Aug 1866; son of Johann Bausch and Regina Eitel; bp. 5 Jul 1924; conf. 5 Jul 1924; m. 21 Feb 1916, Josef Krempl; missing as of 21 Aug 1946 (CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 154; FHL microfilm 271381, 1935 census; IGI)

Theresia Bitter b. Donauwörth, Schwaben, Bayern, 22 Jul 1893; dau. of Hans Bitter and Anna Ziegler; bp. 15 Jun 1926; conf. 20 Jun 1926; m. —— Egensberger; missing as of 20 Aug 1946 (CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 50; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 5; FHL microfilm 25760, 1925 and 1930 censuses)

Babette Boeher or Bocher b. München, München, Bayern, 12 Jun 1879; dau. of Christian Boeher or Bocher and Maria Satzinger; bp. 5 Apr 1936; conf. 5 Apr 1936; m. —— Drezer or Dreher; d. heart condition 13 Jun 1941 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 245; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 49; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 734; IGI)

Auguste Anna Bösmüller b. München, München, Bayern, 20 Oct 1868; dau. of Rudolf Egidi Georg Bösmüller and Auguste Carolina Simbeck; bp. 10 Mar 1937; conf. 10 Mar 1937; m. 23 Nov 1893, E. Morald Ehe; 2m. 12 Aug 1895, Anton Bauer; missing as of 20 Aug 1946 (CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 19; IGI)

Anna Breitsameter b. München, München, Bayern, 19 Dec 1881; dau. of Franz Xaver Breitsameter and Anna Sturm; bp. 11 Feb 1903; conf. 11 Feb 1903; m. München 25 May 1920, Anton Pichler; 1 child; d. stroke München 3 or 9 May 1944 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 120; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 335; IGI)

Agathe Brem b. Kirchdorf, Freising, Bayern, 23 Mar 1871; dau. of Aurel Brem and Anna Maria Meyer; bp. 29 May 1920; conf. 29 May 1920; m. Kirchdorf 27 Feb 1907, Otto Spichtinger; 3 children; d. stroke München, München, Bayern, 21 Jun 1940 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 158 CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 389; IGI)

Heinz Horst Harry Engelhardt b. Königsberg, Ostpreußen, 23 Nov 1912; son of Ernst Paul Engelhardt and Elise Berta Klein; bp. 2 May 1925; conf. 2 May 1925; d. 27 Oct 1942 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 284; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 896)

Willibald Fendl b. München, München, Bayern, 15 Oct 1899; son of Josef Fendl and Katharina Sandl; bp. 20 Jan 1909; conf. 20 Jan 1909; missing as of 20 Feb 1944 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 55; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 158)

Lorenz Gerer b. München, München, Bayern, 2 Apr 1919; son of Josef Gerer and Barbara Rottler; bp. 2 Apr 1927; conf. 2 Apr 1927; ord. deacon 2 Oct 1932; ord. teacher 10 May 1936; ord. priest 30 May 1937; k. in battle Stalingrad, Russia, 12 Dec 1942 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 48; CHL, CR 375 8 2445, no. 84; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 48; A. Gerer; IGI)

Theresia Greimel b. Reinting, Hohenpolding, Bayern, 29 Aug 1862; dau. of Josef Greimel and Therese Schreff; bp. 2 Jul 1927; conf. 2 Jul 1927; m. Taufkirchen, Oberbayern, Bayern, 5 May 1884, Lorenz Nonimacher; 1 child; m. 24 Mar 1900, Johann Burkhardt; d. old age München, München, Bayern, 4 Aug 1944 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 30; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 74; IGI)

Max Grill b. München, München, Bayern, 11 Apr 1917; son of Josef Grill and Maria Sandl; bp. München 23 May 1925; conf. 23 May 1925; ord. deacon 26 May 1935; corporal; k. in battle Italy 15 or 20 Apr or 20 Jul 1945; bur. Futa-Pass, Italy (E. Grill; www.volksbund.de; FHL microfilm 68801, no. 53; CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 463–64; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 208; IGI)

Andreas Jakob Gröber b. München, München, Bayern, 4 Jul 1904; son of Andreas Gröber and Magdalena Hagn; bp. 16 Jun 1923; conf. 16 Jun 1923; missing (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 96)

Gottfried Hartmaier b. Steinen, Lörrach, Baden, 29 Jan 1911; son of Gottfried Hartmaier and Maria Schneider; bp. 13 Jun 1926; conf. 13 Jun 1926; missing as of 20 Mar 1944 (CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 855; FHL microfilm 162777)

Maximilian Hierboeck b. Weihmörting, Weihmörting, Bayern, 25 Sep 1864; son of Georg Hierboeck and Elisabeth Unterbuchberger; bp. 20 Feb 1909; conf. 20 Feb 1909; ord. deacon 14 Nov 1915; ord. teacher 3 Nov 1916; ord. priest 4 Feb 1917; ord. elder 1 Dec 1920; m. München, München, Bayern, 11 Apr 1891, Anna Kislinger; 7 children; k. air raid München 13 Jul 1944; bur. München (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 68; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 240; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Josef Hörner b. München, München, Bayern, 27 Apr 1898; son of Georg Hörner and Anna Angermaier; bp. 17 Oct 1956; m. München 17 or 27 Aug 1919, Philomena Ficklscherer; 6 children; d. in concentration camp Hartheim, Linz, Oberösterreich, Austria, 9 Nov 1940 (Hörner; IGI)

Joseph Hörner b. München, München, Bayern, 3 Apr 1918; son of Josef Hörner and Philomena Ficklscherer; bp. 12 May 1928; d. asphyxiation München 16 or 21 Jun 1939; state funeral (G. Hörner; Der Stern no. 24, Christmas 1939, 387)

Franz Xaver Mathias Huber b. Pfaffenhofen, Ilm, Bayern, 19 Feb 1870; son of Josef Huber and Karolina Eufronia Wunner; bp. 15 Jun 1926; conf. 20 Jun 1926; ord. deacon 27 Jan 1932; ord. teacher 3 Jul 1938; m. 16 Oct 1906 or 1916, Franziska Müller; d. lung disease 22 or 23 May 1944 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 78; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 7; IGI)

Karolina Jordan b. Zwerchstraß, Schwaben, Bayern, 11 Sep 1873; dau. of Georg Jordan and Fanny Hammel; bp. 4 Jul 1914; conf. 4 Jul 1914; m. Georg Wiesent; missing as of 20 Aug 1946 (CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 354; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 500)

Friedrich Karl b. München, München, Bayern, 6 Jun 1915; son of Johann Karl and Therese Vollmer; bp. 30 Nov 1935; conf. 30 Nov 1935; missing as of 4 Apr 1945 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 242; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 731)

Helene Gertrud Rosa Kirschning b. Braunschweig, Braunschweig, 1 Apr 1909; dau. of Friedrich Kirschning and Gertrud Moller; bp. 7 Sep 1918; conf. 7 Sep 1918; m. 9 Sep 1938, Heinrich Hartmann; missing as of 5 Apr 1945 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 281; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 778)

Anna Kislinger b. Adlkofen, Landshut, Bayern, 13 Dec 1870; dau. of Anton Kislinger and Anna Maria Strohhofer; bp. 20 Feb 1909; conf. 20 Feb 1909; m. München, München, Bayern, 11 Apr 1891, Maximilian Hierboeck; 7 children; k. air raid München 13 Jul 1944 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 67; IGI)

Elisabeth Kowald b. Köln, Rheinprovinz, 4 Jun 1904; dau. of Andreas Kowald and Emma Forstmann; bp. 5 Jul 1921; conf. 5 Jul 1921; m. 3 Dec 1928, Karl Zimmermann; missing as of 20 Feb 1940 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 269; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 763)

Josef Krempl b. Karlshuld, Schwaben, Bayern, 9 Sep 1859; son of Michael Krempl and Kreszenz Rai; bp. 2 Aug 1924; conf. 2 Aug 1924; m. 21 Feb 1916, Elisabeth Bausch; missing as of 20 Aug 1946 (CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 155; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 2811; IGI)

Maria Lög b. München, München, Bayern, 22 Sep 1858; dau. of Georg and Kreszens Türk; bp. 19 Jun 1908; conf. 19 Jun 1908; m. —— Riss; d. old age 19 Jun 1942 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 147; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 359; IGI)

Georg Merkel b. München, München, Bayern, 18 Nov 1926; son of Adalbert Merkel and Margarete Weininger; bp. 16 Jun 1940; conf. 16 Jun 1940; private; d. mobile field hospital 681 1 Feb 1945; bur. Kaliningrad, Russia, (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 304; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 934; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Oskar Meyer b. Schrobenhausen, Oberbayern, Bayern, 20 Oct 1917; son of Wilhelm Meyer and Josepha Huiss; bp. 5 Apr 1932; conf. 5 Apr 1932; k. in battle 12 Sep 1944; bur. Wesel, Wesel, Rheinland (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 110; CR 375 8 2445, no. 677; www.volksbund.de; FHL microfilm 245232 1935 census; IGI)

Philippine Meyer b. Schrobenhausen, Oberbayern, Bayern, 17 Apr 1916; dau. of Wilhelm Meyer and Josepha Huiss; bp. 5 Apr 1932; conf. 5 Apr 1932; missing as of 20 Aug 1946 (CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 200; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 676; FHL microfilm 245232; 1935 census)

Rudolf Gottlieb Netting b. München, München, Bayern, 26 Apr 1884; son of Karl Gottlieb Netting and Agathe Kober; bp. 7 Jun 1924; conf. 7 Jun 1924; ord. deacon 18 Mar 1925; ord. teacher 15 May 1927; ord. priest 11 Nov 1930; ord. elder 12 May 1935; m. 7 Oct 1918, Therese Knoll (div.); 2 children; 2m. 2 Jan 1929, Elisabeth Maria Liebler or Liebl (div.); 3m. 3 Apr 1937, Veronika Ligmanovski or Lygenanovek or Lygenanowek; d. stomach cancer München 8 Mar 1940 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 115; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 60; FHL microfilm 245241, 1925 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Anna Babette Oberseither b. Winterhausen, Unterfranken, Bayern, 24 Jan 1873; dau. of Emanuel Decker and Sofie Dorothea Oberseither; bp. 30 Aug 1898; conf. 30 Aug 1898; m. München, München, Bayern 23 Feb 1897, Anton Schindler; 7 children; d. heart condition München 16 Dec 1940 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 164; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 297; IGI, PRF)

Franz Ewald Walter Polier b. Liegnitz, Liegnitz, Schlesien, 27 Jul 1912; son of Franz Albert Joseph Polier and Anna Ernestine Pauline Friedrich; bp. 14 Sep 1929; conf. 14 Sep 1929; ord. deacon 6 Sep 1931; lieutenant; k. in battle Gusaki, Brysgalowo, Russia, 20 Aug 1942 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 243; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 230; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 729; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Sigmund Popp b. München, Bayern, 20 Apr 1905; son of Eduard Popp and Katharina Weinsinger; bp. 11 Jul 1914; conf. 11 Jul 1914; missing as of 20 Jul 1944 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 125; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 229; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 338)

Antonie Katharina Redle b. München, München, Bayern, 10 Oct 1925; dau. of Katharina Hütterer; bp. 5 Jun 1938; conf. 5 Jun 1938; missing as of 20 Aug 1946 (CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 771)

Maximilian Redle b. Freising, Freising, Bayern, 26 Sep 1897; son of Maximilian Redle and Maria Hollmeder; bp. 5 Jun 1938; conf. 5 Jun 1938; m 14 Aug 1931, Maria Hollmeder or Hutterer; k. in battle Russia 18 Oct 1944 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 271, no. 273; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 770; IGI)

Franziska Ring b. Kelheim, Niederbayern, Bayern, 14 Feb 1866; dau. of Johann Ring and Maria Seebauer; bp. 13 Jun 1911; conf. 13 Jun 1911; m. 6 May 1893, Anton Amann; d. stroke 29 Nov 1943 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 6; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 83; IGI)

Johann Sandl b. München, München, Bayern, 3 Aug 1893; son of Therese Sandl; bp. 20 Jan 1909; conf. 20 Jan 1909; ord. teacher 6 Sep 1914; missing as of 20 Feb 1944 (CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 385; FHL microfilm 245257, 1935 census)

Katharina Sandl b. Sünching, Bayern, 18 Nov 1870; dau. of Josef Sandl and Anna Behner; bp. München, München, Bayern, 20 Jan 1909; conf. 20 Jan 1909; m. Josef Fendl; d. stroke 1 Apr or Jul 1943 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 32; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 54; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 159)

Dina Christina Schäfer b. Frankfurt/

Otto Schamböck b. München, München, Bayern, 16 Apr 1922; son of Otto Schamböck and Rosa Lang; bp. 25 Sep 1930; conf. 25 Sep 1930; ord. deacon 2 Jul 1939; k. in battle Eastern Front 17 Sep 1943 (Hörner; FHL microfilm 68801, no. 161; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 652; IGI)

Anna Schenkel b. Neuschwetzingen, Untermarfeld, Bayern, 3 Jan 1883; dau. of Johann Schenkel and Anna Babette Koch; bp. 7 Jun 1924; conf. 7 Jun 1924; m. Triefing, Oberbayern, Bayern, 11 Oct 1904, Friedrich Burkhard; 7 children; 2m. Ingolstadt, Oberbayern, Bayern, 29 May 1916, Benedikt Bachmann; 2 children; 3m. 22 Apr 1940, Josef Mathias Ertl; d. heart attack München, München, Bayern, 8 Sep 1941 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 9; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 142; FHL microfilm 25715, 1930 census; IGI)

Rosine Schenkel b. Neuschwetzingen, Neuburg/

Rudolf Ludwig Schulz b. Neusalz/

Franz Schuster b. München, München, Bayern, 26 Aug 1918; son of Jakob Schuster and Maria Anna Schalch; bp. 23 Jun 1928; conf. 23 Jun 1928; ord. deacon 2 Oct 1932; missing as of 5 April 1945 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 315; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 526)

Sophie Seidl b. Langenfeld, Neustadt, Oberbayern, Bayern, 24 May 1886; dau. of Johann Georg Seidl and Salwina Hagner ; bp. 22 Jun 1929; conf. 22 Jun 1929; m. Karl Bindewald; d. old age 9 Oct 1939 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 22; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 607; FHL microfilm 25723, 1930 census; IGI)

Anton Wilhelm Spaehn b. Reutin, Bayern, 10 Nov 1899; son of Xaver Spaehn and Karolina Demptle; bp. 15 Jun 1926; conf. 20 Jun 1926; missing as of 20 Aug 1946 (CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 275; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 6)

Elisabeth Maria Steinseder b. Hirten, Altötting, Oberbayern, Bayern, 19 Nov 1891; dau. of Georg Schukbeck and Maria Steinseder; bp. 22 Dec 1928; conf. 22 Dec 1928; m. 2 Jan 1929, Rudolf Netting; 2m. 18 May 1936, Jakob Schmid; missing as of 20 Aug 1946 (CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 317; IGI)

Erwin Julius Thaller b. Nürnberg, Mittelfranken, Bayern, 7 Jan 1915; son of Georg Thaller and Regina Böhm; bp. 26 Apr 1924; conf. 26 Apr 1924; ord. deacon 29 Nov 1931; ord. teacher 4 Nov 1934; m. 16 Dec 1939, Anna Reithmeier; constable; d. on the Feodosia-Kertsch branch of the Koy Asan railway 26 Feb 1942; bur. Sewastopol, Ukraine (W. Thaller; www.volksbund.de; FHL microfilm 68801, no. 178; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 331; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 451; FHL microfilm 245283, 1925 and 1935 censuses)

Eugen Theobald Thaller b. Nürnberg, Mittelfranken, Bayern, 12 or 13 Nov 1912; son of Georg Thaller and Regina Böhm; bp. 26 Apr 1924; conf. 26 Apr 1924; ord. deacon 2 Oct 1932; m. 6 Feb 1939, Rosa Pestenhofer; k. in battle Isle of Grado, Italy 27 Jun 1944; bur. Costermano, Italy (W. Thaller; FHL microfilm 68801, no. 179; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 452; www.volksbund.de; FHL microfilm 245283, 1925 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Werner Gerhard Vikari b. München, München, Bayern, 5 Feb 1945; son of Anton Vikari and Hildegard Plötz; d. 20 Apr 1945 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 338; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 2; IGI)

Christian Voigt b. Zwickau, Zwickau, Sachsen, 18 Sep 1909; son of Kurt Alfred Voigt and Melanie Beleman; bp. 10 May 1929; missing (Membership Records LDS C 189)

Karolina Wiesent b. München, München, Bayern, 25 May 1911; dau. of Georg Wiesent and Karolina Jordan; bp. 29 Sep 1923; conf. 29 Sep 1923; missing as of 20 Feb 1944 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 218; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 502)

Katharina Wiesinger b. München, Bayern, 28 Apr 1877; dau. of Jakob Wiesinger and Marie Barbara Steinbeiser; bp. 1 Apr 1913; conf. 1 Apr 1913; m. Josef Wiendl; missing as of 20 Aug 1946 (CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 501; FHL microfilm 245299 1925 and 1935 censuses)

Anton Wimmer b. Altenburg, Landshut, Niederbayern, Bayern, 12 June 1880; son of Peter Wimmer and Anna Nitzel; bp. 4 Oct 1924; conf. 5 Oct 1924; ord. deacon 29 Jan 1928; ord. teacher 18 Apr 1932; ord. priest 30 May 1937; m. München, München, Bayern, 27 Jul 1908, Katharina Kraus; 7 children; d. heart and circulation München 9 Feb 1941 (FHL microfilm 68801, no. 196; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 344; CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 506; IGI)

Notes

[1] Munich city archive.

[2] Helga Seeber, “Werden und Wirken der Mormonen in München” (unpublished history, 1977).

[3] Elisabeth Grill, interview by the author in German, Munich, Germany, August 10, 2006; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[4] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[5] 1 Thessalonians 5:21.

[6] Berta Wolperdinger, interview by the author in German, Munich, Germany, August 22, 2008.

[7] Erna Thekla Probst Lankes Hörner, interview by the author in German, Ramerberg, Germany, August 10, 2006.

[8] West German Mission branch directory, 1939, CHL LR 10045 11.

[9] Gustav Adolf Habermann, interview by the author in German, Munich, Germany, August 22, 2008.

[10] After the war, Georg Hörner wrote to President David O. McKay to explain the circumstances of his father’s excommunication. President McKay then restored the membership status of Josef Hörner.

[11] Georg Hörner, interview by the author in German, Ramerberg, Germany, August 10, 2006.

[12] Rudolf Strebel, interview by the author, Bountiful, Utah, April 10, 2009.

[13] Eyewitnesses disagree about the date. Several indicate that the building stood until 1944. No branch records exist to resolve the question.

[14] The Church tax consisted of less than one percent of an employee’s income that was automatically deducted by the government tax office from the employee’s pay. The only way to avoid paying that very small tax was to officially withdraw from the Church. Both the Catholic and the Lutheran churches collected the tax in those days and still do.

[15] Alfred Gerer, interview by the author in German, Tutzing, Germany, August 21, 2008.

[16] Herbert Roggermeier, interview by the author in German, Taufkirchen, Germany, August 22, 2008.

[17] Edwin Thaller, telephone interview with the author, February 10, 2009.

[18] Gustav actually found the opportunity to take his fiancée to Munich to meet his mother. Sister Habermann was inactive at the time and was reportedly told by one branch member that if she did not attend church, her sons would not survive the war. Several of them were already in uniform.

[19] Werner Thaller, telephone interview with the author, February 5, 2009.

[20] Many eyewitnesses told of extinguishing incendiaries and recalled that a great many of that type of bomb did not ignite at all.

[21] When the author visited Roggermeier in 2008 and asked about his baptism, he responded, “Come out on the balcony [of the eighth story apartment] and I’ll show you where I was baptized. “ He then pointed to the tree by the creek about six hundred yards away.

[22] Munich city archive.