“My Darling Sweetheart”

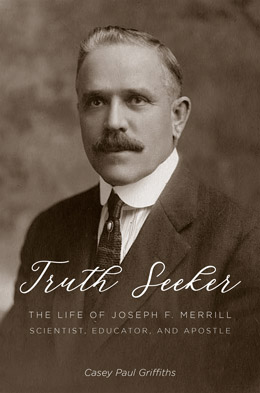

Casey Paul Griffiths, “'My Darling Sweetheart,'” in Truth Seeker: The Life of Joseph F. Merrill, Scientist, Educator, and Apostle (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 41‒72.

Joseph and Laura engaged in an intense correspondence over the next three years, creating a voluminous collection of letters that offer an intimate portrait of the two young lovers. In these pages Joseph emerges from the documentary record as a fully fleshed-out individual, his hopes and anxieties laid completely bare for Laura to read. For her part, Laura can be drawn as an assertive, bright, educated young woman, anxious to engage the world and sometimes constricted by the societal norms surrounding her. Beyond illuminating the life of the future Apostle and his wife, the letters offer a penetrating look into the minds of a pair of young Latter-day Saints in the early years of the postpolygamy era. The world of their youth was defined by plural marriage and the dominance of the Church in nearly every aspect of everyday life. When Joseph F. Merrill boarded the train to travel east, the Church was in the midst of redefining its role in the lives of its members, and it was moving into a new era. Joseph and Laura’s letters put a face on the struggles of the Church during this period, and the young couple represents by proxy the struggles of a new generation of Latter-day Saints to redefine themselves and the role of their culture as their religion moved into the larger world.

Annie Laura Hyde, the future Mrs. Merrill. Photograph taken about the time of her marriage to Joseph in 1898. Courtesy of Annie Whitton.

Annie Laura Hyde, the future Mrs. Merrill. Photograph taken about the time of her marriage to Joseph in 1898. Courtesy of Annie Whitton.

Laura was the more prolific letter writer of the two, composing two letters for every one Joseph wrote. Joseph acknowledged as much, but the lesser volume of his correspondence should not be construed as a measure of lesser affection.[1] Joseph was the dreamier and more romantic of the two, filling his letters with long passages of flowery, poetic phrases meant to express his love and affection. Laura was also affectionate, but she retained an intense fixation on local and national politics, controversies involving the Church, and the future that she hoped to share with Joseph. Joseph was often flippant in his writings, his letters filled with passages meant to offer a self-deprecating portrait of himself as the naive Westerner in the midst of the big city. Her fierce intensity is often contrasted with his deflating, teasing prose. He cautioned her against taking him too seriously, writing, “I am seldom in earnest except when I talk politics and love. I rarely tell half my feelings.”[2]

Despite his glibness, Joseph showed a growing interest in politics and could write forcefully on the subject when his ire was raised. Laura presents a complex portrait of a young Latter-day Saint woman, in contrast to the stereotypical image of a submissive young female Saint that was prevalent during the period. She was devoted to her faith, more than Joseph appears to have been during this time, but she also questioned some Church practices, including polygamy and male dominance in the Church hierarchy. The separation of the young couple, seen as a harsh trial by the two, is a rich source for those seeking to understand the formation of the modern Church during the early years after the end of plural marriage.

On another level, Joseph and Laura’s story is one of many playing out during this time among young Latter-day Saints who left the West to travel to universities in the Eastern United States. During the time, colonies of young Latter-day Saints formed at other universities such as the University of Michigan (where Merrill had attended earlier), Harvard, and Columbia. The experiences of these young Latter-day Saints at these universities became a transformational factor in bridging the divide between the Saints and the rest of the nation. One scholar of the period noted, “Right when Mormon-Gentile animosity was at fever pitch . . . American universities offered a rising, influential generation of Mormons rare, revivifying freedom from Gentile aggression and ecclesiastical oversight. A realm of genuine hospitality, dignity, and freedom, the American university became a liminal, quasi-sacred space where nineteenth-century Mormons could undergo a radical transformation of consciousness and identity.”[3] Joseph and Laura are two examples of the transformation the events of this period produced in the hearts and minds of the rising generation of Latter-day Saints.

Traveling to the East

From the fall of 1895 until his return to Utah two years later, Joseph F. Merrill divided his time between Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, where he spent the fall and winters, and the University of Chicago, where he continued experimental work in the summers. He did not return home during the entire two years, though he constantly teased Laura with the possibility. Several times, particularly near Christmas and springtime, he mentioned rumors of his return with the intent to sweep her off her feet, marry her, and then return to the East with his young bride.[4] Joseph may have been indulging in a subtle game of cat and mouse to continue to stoke the flames of Laura’s affection. If this was the game, Laura gave as good as she got, peppering her letters with mentions that she “had invitations galore and never lack for attention,”[5] and telling her beau that “some of the boys tell me I am the most consummate tease.”[6]

Throughout the summer of 1895, while Joseph remained in Richmond and Laura in Salt Lake City, they wrote to each other. Laura visited Richmond in late July, and a few days after her departure, Joseph sent a letter telling her “I know my own heart I am led to think that between us there is an interchange of pure affection such as is born only with Heaven’s sanction,”[7] comparing her visit to “an enchanting dream which was all too short.” The two seemed to thirst for each other’s company every moment, with Joseph writing, “To think that I would ask you to come here and then wear you out for want of sleep.”[8] When Joseph apologized for writing on substandard paper, she wrote back, “How very simple you must think me, just as if I cared what you wrote on, so that you write is all I care. . . . You have no idea how many times I have read [your letter], but I assure you it has been read several, several, times.”[9]

When Joseph finally boarded the train for Baltimore on 19 September 1895,[10] the young couple immediately began to feel the pangs of separation, with Laura writing, “I felt pretty blue after you left Monday, and I am glad you are not going often, for it is so hard to let you go.”[11] Joseph was swept up in the adventure of traveling all the way across the country, and his letters to Laura took the form of a travelogue, revealing his somewhat provincial nature, despite his schooling in Michigan. He described Arkansas as a “country that appears to be so poor that his Satanic majesty wouldn’t have it” but rejoiced because he “got an excellent meal for fifty-cents at a railroad hotel.” When he arrived in Memphis, Tennessee, he described the city as having “many of the earmarks of a modern city” and praised the local populace as “very neighborly” but also criticized the lack of streetlamps, remarking that “most of the streets are as black as a portion of its population.” He reserved his most lengthy descriptions for the city of Baltimore, describing the city as full of “noise and bustle,” telling her, “the noise of the vehicles, the rattling over the stony street is something that wakes me up in the morning.”[12]

Soon after his arrival, he wrote Laura to inform her that he was shifting his course of study from chemistry to physics, maneuvering for a more likely opening at the University of Utah upon his return home. He wrote apologetically, “In order to do so my darling, I must tell you what seems at present to be a fact, and of which I was very much afraid when I left you, that I was bidding you goodbye for two years. The fear of this made it doubly hard to leave you.”[13] Still, Joseph could hardly contain his excitement as he launched himself wholeheartedly into his studies at Johns Hopkins, telling Laura, “I am still of the opinion that this is the best place in America to study physics.”[14]

“Modern Political Warfare”

Given the intensity of Merrill’s studies in Baltimore, Laura’s letters were a welcome diversion. She wrote passionately and with emotion, and not many interests appear to have held her fancy more than politics. Laura was an ardent Democrat, and many of her letters were filled with attempts to get Joseph to declare himself one as well. Joseph’s family was strongly Republican, but at first he remained aloof of questions of politics, trying to persuade Laura to drop her interest in it, writing, “I could easily think of the leopard changing spots as of your developing into a woman who would delight to revel in the unholy strife of modern political warfare.”[15] Joseph worked to dampen her involvement, saying, “I said if I ever got a wife I hope she would be interested in politics, among other public things. But by that statement I didn’t mean to say that I hoped she would take an active part in politics.”[16]

Laura was undeterred by Joseph’s attempts to dampen her interest in the blood sport of politics. She wrote back, telling him about her work selling flowers and badges at Democratic receptions, and she continued her campaign to persuade him to join the Democratic Party.[17] She sensed that some of his hesitation came from his family’s Republican ties. Joseph’s younger sister wrote Laura, telling her that Joseph was a Republican because “if a person is on the fence he is always a Republican.”[18] Learning this, Laura declared her feelings in no uncertain terms: “For goodness sake Joseph say you are a Democrat. Of course you are a Democrat are you not? You should declare yourself.” She then added, threateningly, “Mama said it was the only way to decide our case, to lay it before you and let you decide.”[19] Their arguing, mostly with a teasing tone, continued as the months wore on. Joseph wrote back, telling Laura, “I think you would make a good criminal lawyer. . . . I was foolishly thinking that I would have no difficulty in arguing you into my way of thinking on political matters, but your last letter revealed a new fervor I didn’t know you possessed. Hereafter, I shall be a little shy of drawing you into debates. . . . If I ever do essay a debate with you I shall be better prepared, now that I know your power better.”[20]

The letters between the two reflect the growing partisan divide in Utah. With the dissolution of the Church-sponsored People’s Party in 1891,[21] more and more of the Saints joined both the Democratic and Republican Parties. The Church had participated in partisan politics for decades before the end of plural marriage, and as Utah approached statehood, the political role of the Church was still undergoing refinement. One particularly polarizing figure in Utah politics, the Latter-day Saint Apostle Moses Thatcher, received frequent mention in Joseph and Laura’s exchanges.

Moses Thatcher was a successful businessman from Logan who had business ties to both Joseph’s and Laura’s fathers.[22] He was also deeply involved in Utah politics and after the dissolution of the Church party became an important figure in the Democratic Party. He was also a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Thatcher and B. H. Roberts became outspoken opponents of what they saw as the gradually strengthening dominance of the Republican Party, led by fellow Apostles John Henry Smith and Joseph F. Smith. Several times during the early 1890s, Thatcher was rebuked by Church leaders for his strong partisan stances. He even reportedly declared that Jesus Christ would have been a Democrat, and Satan a Republican. By the time Joseph departed for the East, the acrimony between Thatcher and the Church hierarchy was reaching a fever pitch, and rumors began to abound of his possible expulsion from the Quorum of the Twelve or even his excommunication.[23]

There was likely no love lost between Joseph Merrill and Moses Thatcher. Less than a year earlier, Thatcher had incorrectly criticized Marriner Merrill in a Church meeting in Paris, Idaho, saying that Merrill had been “rebuked” by the First Presidency for teaching politics too strongly.[24] Thatcher also opposed Marriner’s appointment as president of the Logan Temple.[25] Laura, with her strong Democratic leanings, saw Thatcher almost as a political martyr. Thatcher was also suffering from a “very severe and serious digestive trouble,” most likely a chronic stomach ulcer linked to anxiety and stress.[26] Hearing of Thatcher’s failing health, she wrote to Joseph, “Brother Thatcher is very ill. I hear that they are having a fast day for him in Logan, and I believe in the whole of Cache. I hope he will recover. He is a very dear friend of ours and was a friend in need, standing up for what he knew to be right in spite of everything.”[27]

While Joseph was pursuing his studies in the East, the acrimony between Thatcher and the remainder of the Church hierarchy reached its climax. In the months following Joseph’s departure, Church leaders pressed Thatcher to sign a document known as the “political manifesto” that declared, among other things, that current leaders in the Church hierarchy would refrain from running for public office. Thatcher, who was politically ambitious and had hopes of someday serving as a United States senator, categorically refused to sign the document. Brigham Young Jr., one of Thatcher’s harshest critics among the Church leadership, wrote that Thatcher “throws away the Priesthood and hugs politics, rendering fealty to the world at the same time inconstant to his former vows.”[28] The debate stretched over a period of months until the Church general conference held in April 1896, where the political manifesto was read to the audience and unanimously accepted. The very next order of business was a reading of the General Authorities of the Church for sustaining, and Thatcher’s name was omitted from the list.

Seated among the crowd was Laura Hyde, who noted the omission in her next letter to Joseph. By then her devotion to the Church seems to have outweighed her ties to Thatcher. She wrote, “I fell in full accord with the sentiments expressed. . . . I felt it was perfectly right and voted heartily for it.”[29] Supportive of the authorities, she still worried over Thatcher, particularly his health. “Oh Joseph darling!” she wrote, “Brother Thatcher’s name was not mentioned, he had been dropped from his quorum. It was dreadful darling, we have always thought so much of him, and in his condition, I am afraid it will kill him.”[30] While Laura was loyal to her faith, she lamented that “it is to be regretted that the church engages in politics at all, and it is to be hoped that they will soon cease to do so.”[31]

Joseph’s feelings about the whole affair are less transparent. He was generally coy in his letters to Laura, perhaps downplaying his opinions in response to her fiery passion for politics. Indications of his feelings are best found in the letters from his parents, who seemed to think their son was on the verge of apostasy. His letters to his parents have not survived, but in a letter to Laura, Joseph revealed he had told his parents that “I thought high church men should keep out of politics, that church influence should not be used in politics, because it could not be exercised without violating a solemn pledge given to the public.”[32] Joseph’s parents took the letter as a sign of apostasy, and his mother wrote back, “I can’t feel it right for you to pick at the Presidency if they have faults.”[33] She privately warned him that “Pa is getting uneasy about you.” His parents counseled him to stop receiving the Salt Lake Herald, a pro-Democratic paper supporting Moses Thatcher, urging him instead to receive the more pro-Church Deseret News. Maria supported Marriner, writing that the Deseret News contained the sermons of Church leaders and that “we know you need spiritual food because without it we die spiritually, and Pa says he knows the Herald will embitter you against the Church.” It is apparent that Joseph was more direct in sharing his views with his mother because she cautioned him, writing, “Joseph if I was to tell him all I know about you he would feel more uneasy than ever . . . why he says he would rather you could not read or write than to deny the faith.” Maria’s fears for her son’s spiritual well-being are apparent in her writings as well. She sent a rebuke to Joseph, who “we have prided in and thought would be a shining light in the Church.” She continued, “Then to hear you talk about our religion and the Authorities as you do it pains my heart. . . . I had such confidence in you that I thought you could not be shaken. I was for a long time perfectly content in that regard even when I heard others express their fear.”[34]

Joseph wrote a long letter to his mother and father trying to clarify his views and also informed Laura that “my parents are greatly exercised over me thinking I am on the verge of apostasy.” He also readied himself for the possibility of his parents taking more extreme measures to bring him back to the fold, writing, “It may be possible that I shall be asked to spend my summer in the mission field in order to convert myself.” He also thought that his parents’ strong reaction could possibly stem from larger problems in the Church back in Utah: “I confess I cannot understand how such anxiety could originate unless it be that there is a wave of apostasy sweeping over the Church.” At the same time, he recognized the reasonableness of his mother’s fears, given that his own uncle lost his belief in the faith while on a similar educational sojourn in the East. “I think I can sympathize with her,” he wrote to Laura. “Ever since I first left for Ann Arbor there have been busy tongues always telling her that I would deny the ‘faith’—for college education in the east always ‘ruins our boys.’ She has heard this talk for six years, and naturally it has made her a little uneasy at times.”[35]

Laura replied in terms of consolation, writing that “I think it is a downright shame that your folks should suspect you of being anything but a true Latter-day Saint” and that “they do not fully sympathize or understand you.”[36] Regarding the possibility of a mission call, she teasingly wrote, “Where would you be expected to preach? East, South, or would they make a missionary of you in Utah? I wonder if I don’t need preaching to and converting as much as the heathen. I am sure you could convert me sooner than anyone else.”[37]

If Joseph was indeed on the road to apostasy, the only sin his letters indicate is profligacy in his observance of the Sabbath day. His letters, usually written on Sundays, contain numerous moments of self-chastisement over his activities on the holy day. One letter from late in his first year at Johns Hopkins seems to have captured the depth of this Sabbath-breaking demeanor: “I really wonder if I am getting bad? ‘Is it wrong, really wrong?’ I have asked myself today. You know I have told you recently that I have busied myself more or less lately on the Sabbath with my school work. Only once or twice, however, have I studied but my engagement was rather in the way of writing-copying,” he wrote, justifying his behavior.[38] While Joseph did not engage in any particularly troublesome acts, his time in the East did represent a peak of spiritual apathy in his life. He wrote to Laura, “I believe I am the only Mormon at Hopkins,” and “there are no LDS missionaries or branch of the Church in this region that I know of.”[39] With no local congregation to attend, Joseph became somewhat aloof in his attitude toward worship services. During his first summer away he wrote to Laura, “It’s a little amusing to see some pious people; they seem to think religion consists principally in going to church. But I must confess that judged by this standard I have lost nearly all my religion. I haven’t been to church but once since May 30. What do you think will become of me! Don’t the prospects frighten you?”[40]

However, accusing Joseph of apathy in spiritual things may be an inaccurate assessment. He was deeply interested in religion, and during his time in the East he attended dozens of different church services with local acquaintances, usually his roommates. With the visits occurring on the same day that he usually wrote Laura, his religious explorations often served as material in composing his letters to her. The wide variety of religious experiences he sought out are evident in his letters. He wrote of attending a lecture by Robert Ingersoll, a popular speaker known as “the Great Agnostic” of the Gilded Age.[41] Joseph expresses no sympathy or antagonism toward Ingersoll’s views, but he admits, “I never before or since heard such eloquent description and eulogistic utterances. I was simply spellbound by his ever increasing eloquence.”[42]

One spiritualist meeting Joseph attended was singled out to provide comedic fodder in a letter to Laura. When a speaker at the meeting claimed to be a resident of the third heaven, Joseph balked at the description: “He forgot to tell us how he got back to earth, or whether he was in his body or not. During his talk, however he said a spirit could not get back into his body after passing through what he called the resurrection or what we call death. After having made this statement, and in view of his claims about his residence, one would have thought that he would have been a little more particular to tell about his own condition.” As the meeting became more theatrical in nature, Joseph’s skepticism continued to rise: “He began telling this person and that one that such and such a spirit was present, named so and so, and saying so and so. When he told anything to a person he would say, ‘Am I right!’ But he happened to be wrong about as often as he was right.” Joseph then found himself the center of attention in the meeting: “Pretty soon he came advancing down the aisle and pointing his finger at me, said ‘May I tell you something.’ ‘Certainly,’ I replied. Then he began ‘there is a beautiful young girl about 14 years old with the most pleasant countenance standing by you with her arm on your shoulder. She is holding a beautiful cream colored rosebud in her left hand and she turns and speaks to you; she says (and he threw his head wildly about) “my brother!” Have you a sister in the spirit world?’ I said, yes, then he said, ‘and you gave her that rose on her death bed. Am I right?’” Joseph replied, “No.” He contently reported to Laura that “this shut him off.” Joseph continued, “Yet he left me, declaring he was right, but that I had forgotten. He finally said he didn’t think I was a spiritualist anyhow. Had I answered yes to all his interjections I presume I would have received a long message as some of the others did.”[43]

If the dramatic nature of the spiritualists disturbed the young Latter-day Saint, he found a contrasting example when he attended a Quaker meeting a few months later. He wrote, “There was no organ, no singers, anywhere to be seen. These simple worshippers do not grieve the Spirit by indulging in frivolous music making.” According to Joseph’s description, the service, which lasted an hour and a half, was held in complete silence broken only by two members of the congregation who were moved to stand up and pray or deliver a discourse. Joseph described the end of the meeting held by these “lovers of silence” by noting that “after another silent fast of fifteen minutes duration a man arose and said ‘we will meet again at eight o’clock this evening.’ This ended the service.”[44]

Later in his life, Joseph claimed to have attended dozens of different church services during his time in the East, though his enthusiasm for describing them gradually waned in his letter writing. However, he frequently referred to these experiences and contrasted them with his experience in the Church. In 1946 he wrote, “I usually attended one non-Mormon church service, sometimes two services every Sunday” and claimed to have attended the services of various denominations “at least 350 times” during the nine-year period of his education in Michigan, Baltimore, Chicago, and New York. He continued, “I listened to many eloquent sermons, but never once did I hear the preacher use the word ‘know’ with the meaning we give it in our testimony bearing.”[45]

Joseph’s letters from his time at Johns Hopkins don’t provide any indication of a real search for a new faith; rather, they reveal a hunger for some kind of communal experience. The congregations in the settlements of his youth were more than just religious services—in the early Latter-day Saint settlements the line between church and community was practically nonexistent. He told Laura, “I believe we go to church largely because our friends go and we want to see them and mingle more or less with them, if I knew the member of any congregation here and had any interest in them, no doubt I would go to church very much more often than I do.”[46] These statements provide a key to understanding his religious explorations while in the East: Joseph felt a lack of connection, a loneliness. He wrote that, in contrast to the lively student community at the University of Utah, “social life at the J.H.U. is at a low ebb. . . . Most students who come here came for business, they are not-flush with means and their whole desire seems to be to get through in the shortest possible time and get away.” He also hinted at the contrast between his schooling in the smaller frontier city of Salt Lake and his experience in a larger metropolis like Baltimore, writing, “This being a large city, it . . . absorbs the student body so that social activity due to school organization doesn’t amount to anything.”[47]

At times Joseph was cynical in his assessment of the various churches he visited every week, feeling a lack of substance in the sermons he heard. He wrote to Laura, “Most of the sermons are non-interesting and largely of the emotional type. Further, I am so egotistic that I usually feel these professional divines don’t know as much about the true principles of salvation as I myself.”[48] Laura, who was generally more sunny in her assessments of others, replied with her views on church attendance, telling Joseph, “The great majority [of people] go for the good they receive,” and “they are all brothers and sisters working in the same cause for the advancement of God’s work.” She then added as a note of caution: “Darling don’t let your college training make you, as scoffers always contend it does, cynical and indifferent.”[49]

In this and other exchanges, Laura emerges as a vital check on Joseph’s tendency toward sarcasm and cynicism in his assessments of his life in Baltimore. Commenting on a Church sermon she had recently heard, she wrote that “the happy man was the only successful one, and that this earth could be a heaven to us if we made it so. Old thoughts, old ideas, but bustling with truth.”[50] In their correspondence, Laura also emerges as the more spiritually minded of the two. Faced with challenges of her own at home, she wrote of leaving her difficulties “in the Lord’s hands, and I feel perfectly resigned that no matter how it turns out it will be for our best good.” When faced with doubts concerning the divine, she wrote, “I do not feel that because He has not answered our prayers He has not heard them, & I think we are probably like children asking for things which Our Father with His greater wisdom sees as not for our good.”[51]

Laura was even willing to defend the most controversial of Latter-day Saint practices, plural marriage, writing, “We all believe in it firmly, believe that it was revealed for some purpose known to Him.” But she did express a realistic view of the difficulties found in the lifestyle associated with plural marriage: “We did not want it to come to us, as we did not believe there was any happiness, save that which comes from knowing one is doing their duty, and doing the will of God. Yet we have said we would obey and do the best we could if we were to be tried in that way.”[52]

Yet while Laura was more orthodox in her views of religion, she too was an explorer of faith. She was not attending a different church every week like Joseph was, and she was devoted to the Church, but she was adventurous in her thoughts about the future of her faith and the role of women in it. Laura was a curious mix of old-fashioned and progressive, both mingled together in the same character. Living in a great age of progressive women, including Latter-day Saint feminists like Emmeline B. Wells, Susa Young Gates, and a host of others,[53] Laura wrote, “I used to admire the progressive woman, the woman who surmounting all difficulties carved a name for herself” and described “pity for the old time woman who was content within the foundation of her house, content there to live for her husband and her children when if her talents had been used she could have gained distinction.” She continued, “I overlooked that it takes the greatest of talents to make a happy home.”[54]

Seemingly settled into a future role as a homemaker, in the next paragraph she returned to her less orthodox views: “My idea is still strong that a woman has a right to all the privileges that a man enjoys and I think too that it will not be long before our church sees its narrowness and will grant women all the powers of the priesthood and that a single woman, as well as a single [man] will be allowed to hold the priesthood and officiate in its ordinances.”[55] Such sentiments, coming from a young Latter-day Saint woman in the 1890s, are surprising even more than a century later, but Laura saw no conflict between the two female icons of a devoted housewife and a progressive feminist.

Laura’s comments immediately snapped Joseph out of the laxity toward religion he had felt since his arrival in Baltimore. The voice of the former branch president, shepherd to a group of wayward students at the University of Michigan, reemerged through the counsel found in his return letter to her: “I could laugh at such a remark from one whom I knew had no faith in Mormonism, for the most obvious inference is that the Church is governed by men, not by Jesus Christ himself through men as agents.” He continued, “Oh, Laura, do you not see that to say the Church is narrow in this thing is to say that God is narrow, that he is unjust. The Lord has said upon whom the Priesthood may be conferred and until he says it may be conferred upon women, no officer in the Church can so confer it. You sure understand this if you will reflect a moment. If you do, then if you will remember that I have unshaken belief that Christ has not deserted the Church; that he is with it today as much as ever, you may understand that you could never stir me.”[56]

Laura in turn replied with one of the sharpest exchanges in any of their letters: “I do not doubt for a moment that Christ is not with His church, nor do I think that every officer in the church could confer any order of the priesthood unless [he] had that authority from God. I believe that God reveals Himself to His prophet on the earth as much today when it is necessary, as He did to Joseph Smith and I would not be a good Mormon did I think otherwise.” Her spiritual credentials established, Laura returned to her original point: “Why can He not reveal that it is His will that a woman who is worthy hold the Priesthood? We are not given all revelations at once, we are not prepared for them all, but we grow near to God and fit ourselves for fresh revelations. He will reveal more of His will to us.”[57]

She then launched into a lengthy explanation of her views, writing, “Joseph Smith in organizing the Relief Society in Nauvoo said he intended to make a society of priests as in the days of Enoch. He did not say priestesses and there were unmarried women in that society. Could he not have foreseen what God was to reveal?” Laura then conceded that she saw a great role for women as part of the future of the Church, but she admitted that her wishes might be premature. “If the priesthood gives a person any greater advantages or blessings and helps them to reach higher, does not a tender and loving father think as much for the welfare of his daughters, and for their advancement, as for that of his sons? If the members of the church are yet narrow minded God is not, He may in pity for us keep many things back because we are not ready to receive them.”[58]

Joseph, sensing he may have touched a raw nerve, was more conciliatory in his reply: “I do not presume to say what will be revealed, but I do not believe that God is ever unjust, though to our finite minds it is very hard, or impossible, to see the justice in His ways.” Handling the topic with considerable finesse, he continues, “I dare not believe that in the past an injustice has been done women by granting them no more of the rights of the Priesthood. If ever it becomes right—and just—for married women to hold the Priesthood, I believe they will do it.” Addressing the larger topic of the rights of women, he added, “I am in favor of the largest freedom, consistent with morality, for all women, as well as men, who are not bound by marriage vows and maternal duties. But matrimony and motherhood involve limitations and responsibilities as well as privileges and opportunities. And I believe that those women, if there are any who cannot cheerfully bear the former should not enjoy the latter.”[59]

The exchanges continued over the months, and what is presented here serves only as a sampling of the political and theological sparring of two intelligent, articulate young people. Regarding the elements of their religious faith, it is tempting to steer the narrative to favor one or the other of the partners, depicting the faithful girl at home pulling her wandering fiancé away from the brink of apostasy, or the valiant priesthood holder explaining the fallacious views of radical feminists. The truth, as found in the letters, is that each spent their time wandering and exploring different paths of belief and thought, and each served as an important check to the other in regard to their religious beliefs. Like two magnets, they seemed to continually draw each other toward a central point. It is tempting to speculate whether the young scholar may have become indifferent toward religious observance altogether without his constant correspondence with Laura. Likewise, the possibility exists that she may have become an agitator within the faith without Joseph’s restraining hand. But all this is speculative. In truth, they kept each other centered, and as their discussions became more candid, they experienced the joy of discovering what the other was really like. In the same letter in which he expressed his views on women and the priesthood, Joseph wrote, “Nearly all, if not all, your letters have something of the personality of the writer in them. I know more about you than I did a year ago. But I have not found you failing as many things and persons do under the eyes of scrutiny.”[60]

“The Fireworks of Politics”

It was a time of transformation for Joseph and Laura in more than just their religious views. Joseph found himself in close proximity to the nation’s capital in the midst of one of the most exciting presidential contests in years. The country was afire with the controversy surrounding free silver, with the Democratic Party favoring bimetallism, the coining of both gold and silver as national currency, and the Republican Party opposing it. The dispute seems strangely colloquial to the modern reader, but it was argued with all of the vehemence accompanying the most divisive political topics in any era of American history. As usual, Laura was firm and passionate in her convictions, supporting the Democrats and telling Joseph her home was “a house of free silver enthusiasts.” She wrote with enthusiasm about Emmeline B. Wells, a prominent Latter-day Saint suffragist, and about the President of the Church, Joseph F. Smith, and how she wanted to “see whether the Church was for Rep. or Democracy this fall,” practically equating the opinions of the Democratic Party with the institution of democracy itself.[61]

Joseph remained noncommittal, writing to Laura that “should ‘free silver’ elect a president in Nov. and House in harmony with him there will be the greatest financial shaking up this country has seen for many a day. . . . Free silver will not bring all the blessings to the poor man that its warmest advocates claim.” Where Laura was earnestly serious about her politics, he remained coy, writing in a tone of superiority, “I am sure that the mass of the people will vote on it without understanding its merits. In this country when times are hard people always vote for a change.”[62] Less than two weeks later, Joseph relocated to Chicago to pursue his research there and found himself in the midst of one of the most famous political conventions in American history.

In July 1896, thirty-six-year-old William Jennings Bryan, acclaimed as “the boy orator,” won the Democratic nomination for president by delivering his “Cross of Gold” speech at the party convention in Chicago. Joseph still feigned aloofness to the entire affair but admitted he had been caught up in the excitement surrounding the city and had walked over to the site of the convention. “Having no ticket I stayed outside,” he wrote to Laura, “I heard the applause that each candidate received as he was nominated.”[63] During the convention proceedings Bryan gave a performance that is still famous in the annals of political discourse. Painting the free silver controversy as a class struggle between the rich and the poor, he declared, “You come to us and tell us that the great cities are in favor of the gold standard; we reply that the great cities rest upon our broad and fertile prairies. Burn down your cities and leave our farms, and your cities will spring up again as if by magic; but destroy our farms and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country.” At the climax of the speech, Bryan declared, “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns; you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold,” and then he held his arms in a crucifixion pose for a full five seconds, as if offering himself as a sacrifice.[64]

Given his response to the speech, it is likely that Joseph was one of the many crowding into the entrances to hear the oration. The crowd within the convention burst into a pandemonium of acclaim. According to contemporary accounts, one farmer who was about to leave rather than listen to Bryan’s speech threw his hat into the air, slapped the empty seat in front of him with his coat, and shouted, “My God! My God! My God!”[65] The effect was no less dramatic on Joseph. He wrote to Laura, “It is doubtful if ever in the history of the world there was a speech that electrified more than his [Bryan’s]. In this day men proudly say that reason governs, that oratory has lost its vaunted powers. But this speech put reason and calculation to flight. Bryan’s tongue will be worth a cold million of McKinley’s gold in this campaign.”[66]

He still maintained an air of neutrality, writing, “I am compelled to remain an independent in politics,” but it is clear that he was thrilled by this exposure to the power of Bryan’s oratory and found himself clearly leaning toward the Democratic Party, speaking in tones of praise about Bryan: “The candidate is an able young man of untarnished character and reputation, unselfishly devoted to what he thinks is right and fearless in his crusade against what he thinks is wrong.” It is easy to see how Bryan’s speech, with its potent imagery of the lowly farmer fighting the corrupt city-dwellers, appealed to Joseph, who even during his tenure as an instructor at the university spent his summers tilling the soil of his father’s farm. Bryan’s theatrics and Christian imagery struck a chord as well, and Joseph admiringly observed that Bryan was “a devoted ‘Christian’ and an ardent Sunday School worker.”[67]

Laura appeared to be delighted at the gradual political conversion of her fiancé and wrote to him with excitement about serving as a delegate to the Utah Democratic convention. She asked Joseph to “write me all the things political you deign to because I enjoy them and they teach me so much.”[68] Joseph responded accordingly, coloring his letters of the next few weeks with his observations and insights from the people surrounding him. One of his roommates, unidentified in the letter, told him in no uncertain terms that Democratic supporters “ought to be shot as traitors to the human race if they would still vote for Bryan” and that a Bryan presidency would “bring more disaster and suffering upon the country than all the wars and famines combined.”[69]

William Jennings Bryan lost the 1896 presidential election, but Laura lost none of her resolve, writing to Joseph that “even if Bryan did get defeated, this morning’s paper says we have elected the democratic ticket, which is some consolation anyway.”[70] Joseph’s experience in Chicago and the subsequent months following the Bryan campaign permanently converted him to politics. Back in Baltimore after his summer studies, he made the trip to Washington, DC, to attend William McKinley’s inaugural festivities. His wide-eyed observations reveal an endearing side of his innocence and provincialism: “The show consisted of people, people, people, in various places,” he wrote. “I never saw so many people out before and probably nearly half of them were negroes. Washington appears to be the colored man’s heaven.”[71] If Bryan’s campaign was a failure on the national level, it was a rousing success in converting Joseph to an ardent Democrat who consoled his love by promising her that “I shall wait and take you with me to Bryan’s inaugural ball four years hence.”[72]

Joseph’s and Laura’s devotion to national politics represents the growing awareness and involvement of Latter-day Saints in the world around them. At the same time, Joseph and Laura showed a unique fusion of the theological worldview of the spiritual kingdom that shaped their early views and their emerging consciousness as citizens of the American nation. Their views on politics often mingled freely with their religious worldview, in which they saw the world in terms of a battle between the rising Kingdom of God and the worldly powers of Satan. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was still vilified thoroughly in the nation’s presses, and it was seen as a dangerous menace throughout the nation. “Regarding politics,” Joseph wrote, “I am going to express a belief . . . that this high praise with which everyone is lauded who in any way opposes the church is not prompted exactly by the right kind of spirit.” He continues, “I believe thoroughly in the existence of evil spirits and in the cunning of Satan. . . . It is unnecessary to tell you that we are taught that these are the last days and that the Good Book foretells that Satan shall have great power in such days.” Joseph worried about the “very elect” of the Church falling and warned that “one should think even thrice before allowing the fireworks of politics to carry him on to dangerous ground.”[73]

Laura also mingled her religious devotions and her politics, telling Joseph, “When I prayed about the election I prayed that God’s will might be fulfilled.” When Bryan lost the election, she wrote, “I believe when we do everything we can, and then we are seemingly defeated and crushed we should trust in God still, and believe He is allowing these things to happen for our own good.” Expressing her own fiery nature in politics, she added, “But I never believe in giving up while there is anything to be done.”[74]

“When Did You First Love Me?”

In the letters between Joseph and Laura during their separation, all the expressions devoted to religion and politics form a small part of the correspondence compared to expressions of their feelings for each other. These were, after all, love letters. Joseph, in particular, was determined to be romantic, constantly veering the conversation away from his views on other things to devote long passages to how he missed Laura and longed for her companionship. “My heart is tired of the pen,” he wrote. “It wants other ways of expressing itself. The pen is such an unfeeling thing, it cannot in crude fingers convey to another the feeling and finer sentiments of the heart. I long to hold you so close that you can feel my heart throbs for you.”[75] Laura was just as enraptured, if more restrained, in sharing her feelings with Joseph. “What a delightful thing love is, isn’t it?” she wrote to Joseph. “It makes everything so beautiful for us. There are many things in which I saw no beauty until I loved and was loved, and now it seems I can find beauty in everything.”[76]

Laura Hyde Merrill in a four-generation photo taken in 1899 with her mother, Annie Maria Ballantyne Taylor, her grandmother Jane Ballantyne (wife of Church President John Taylor), and her son Joseph Hyde Merrill. Courtesy of Annie Whitton.

Laura Hyde Merrill in a four-generation photo taken in 1899 with her mother, Annie Maria Ballantyne Taylor, her grandmother Jane Ballantyne (wife of Church President John Taylor), and her son Joseph Hyde Merrill. Courtesy of Annie Whitton.

Their letters often took a teasing tone. Joseph knew he would raise the ire of the fiery suffragette when he wrote, “Some women stumpers say their sex is in bondage, and they long for freedom. What nonsense. Women rule the world, and whatever bondage they suffer they have themselves to blame for it. But my opinion is that if the time ever comes that women wade in the mire of politics as freely as men do now, that they will then find they rule men less than they do now. Their scepter of power will be tarnished, if indeed it is not shattered.”[77] Laura often failed to see the humor in his exchanges, telling him, “I don’t know whether you deserve anymore letters from me or not after the way you ridicule me, and combat every mild assertion or remark I make. I believe you enjoy arguing with and trying to convince a person of the failing of their views.”[78]

Joseph was aware of Laura’s temper, writing, “Until you are ruffled you are ideally affectionate. But I think the ice of Greenland is not colder than you when you have lost control of yourself.”[79] He always apologized when he sensed hurt feelings: “My darling I beg of you to try to control yourself when you are tempted to be angry with me. . . . I frankly confess that my imagination if allowed to run, working with such an incident as this paints many unpleasant scenes in our future home. I want my wife to be a woman who will be patient and forbearing with me.”[80] In order to deflect her wrath, Joseph was often the butt of his own jokes, especially about his weight. After receiving some visitors from Utah, he wrote, “I am so fat and hearty looking that every one of those hungry appearing Utonians asked where I was boarding. The last time I got on a penny scale they wouldn’t go because I was so heavy.”[81]

One truth emerging from the letters is that the two young correspondents were in love, and in love with the idea of being in love. Laura asked almost giddily, “When did you first love me and think I could be dearer to you than other women? You do love me, don’t you? I know you do, and it gives me great pleasure to know it.”[82] In another letter, written in a more melancholy mood, she mused, “I know I should not be happy to marry anyone who did not love me. I should much rather never be married here or hereafter.”[83] Joseph returned the sentiment, telling her, “I have already drunk from the cup of single blessedness to my heart’s content. Yet I shall replace it with the other cup only when my heart’s queen sips jointly with me.”[84]

Above all sentiment, they longed to return to each other. Laura kept a ribbon calendar, anticipating the days until his return. She wrote, “Every morning as I move it for another day I say to myself he is another day nearer.”[85] When she discovered, after a year of separation, that his time in the East was to be lengthened by another year, she was devastated. She later wrote, “I wanted you to come and take possession of me, to show people that you loved me, and that I belonged to you.”[86] Sensing her disappointment, Joseph wrote back, “Laura, you do not ‘belong’ to me except as your heart makes you truly mine, just as my heart makes me truly yours.”[87]

“I Have Very Little Hope of Obtaining This Degree”

The only thing keeping the young couple apart was Joseph’s ambition, but by the winter of 1897, after eighteen months of toil and shuttling between Johns Hopkins and the University of Chicago, even that appeared to be waning. After a year of steady work, Joseph began to grow cynical about the process of graduate education. He wrote to Laura, “It is astonishing to think how little, as a rule, are in these theses, yet how much time they take. All this time is spent in clearing up some little point, a point of itself of no great consequence, yet involving a truth which must be known in order that the science may advance.”[88] Laura acknowledged his discouragement but responded kiddingly, “How are you getting along with your experiments? I expect the last question to be answered by ‘I have given them up.’”[89] She kept up a steady stream of encouragement to the young scholar, writing, “I think it is best to get knowledge, and work for that rather than honors, but a degree certainly gives prestige.”[90]

A few months later, with obstacles piling up and his funds nearly exhausted, he wrote her, “Laura to tell you the truth, I have very little hope of ever getting this degree. This degree is desirable but it is not worth everything. As I look at it now its cost is more for more than I can afford to give.”[91] Joseph was subsisting on money borrowed from his father, and his promissory notes continued to pile up. From the spring of 1897 alone, there are three different notes written by Joseph, apparently to himself, promising to repay his father within the year, and even committing himself to an interest rate on the loans of 10 percent per year.[92] He remained uncertain as the weeks wore on, writing Laura, “I may get a degree sometime and I may not. Another years’ study here under fortunate circumstances would make me a PhD, but I do not think it the part of wisdom to try to maintain myself here next year.”[93]

Making matters worse, there was a regime change at the University of Utah that upset all his future plans. While Joseph was in the East, his uncle Joseph T. Kingsbury was elected as the new president of the University of Utah. While this familial connection might have been encouraging to Joseph, word soon arrived that his assured position as a professor was in jeopardy. Enraged, he vented his feelings to his fiancée: “To say that I am mad expresses it but lightly. I am going to kick and kick hard too. My kick may take me out of the Univ., but in my present mood I can truthfully say I don’t care. The moment I saw the report I could hardly restrain myself from sitting right down and telling Kingsbury ‘a professorship or nothing.’” He railed, “[Kingsbury] recently told my father that I would be the strongest man at the Univ. on my return: Nice words to be sure, but deeds count in this world.” His rage gave way to despair as he wrote, “I have now spent the equivalent of seven college years in the best institutions of America and have spared no expense to qualify. I believe no man in the schools of Utah has spent as much time in preparation and at as great an expense. I voluntarily asked for a leave of absence without pay. . . . Yet I am to return to the position I left.”[94] His anger was channeled into finishing his studies, but he was too aware of his limitations to commit fully. “If I can make the degree without too great an expense, I shall do it. But too many years of my life are behind me, and my finances too limited and the real advantages too few to justify me in making any and every sacrifice for the degree.”[95]

Joseph’s mother was shocked at Kingsbury’s behavior, telling her son, “I thought him to be more just than that.” She saw Joseph’s struggles in academia as the work of Satan: “You are capable of doing much good in the University—the Devil is sure to kick, there is always opposition to the Lord’s work.”[96] Laura saw her future plans disrupted and wrote that “Kingsbury has treated you shamefully.” She also wrote tenderly, in a tone of self-sacrifice, “You know the greatest desire you have at present is to gain your PhD and you would do anything, or sacrifice anything to get it,” knowing that the situation possibly meant another year of separation but wanting the best for Joseph.[97]

When it became clear that Joseph was returning home at the end of the summer instead of continuing his studies, Laura was gripped by a flood of conflicting emotions. “What if your dreams come true? What if you come to Salt Lake and find your sweetheart not what you had imagined? . . . Oh, Joseph I do not want you to pretend to love me.” Her thoughts raced: “What a dreadful thing it would be if you were to kiss me and find it was repulsive to you.” She was tentative about their future relationship and unsure about his feelings for her: “I think I had better receive you as a friend when you return instead of as a lover don’t you?”[98] Joseph wrote back, assuaging her fears, telling her, “I have not done a great deal of courting in my letters, because I have all the time been dreaming of the delightful little scenes we will make by ourselves when I return, and I have felt a little backward about marring their beauty by my crude pen.” He then addressed her offer of friendship instead of love: “Though I know of course that you were joking yet I like much better to have you say that you will rush into my arms than you will give me a formal reception when I return. The picture of your receiving me as a mere friend is not at all pleasant.” He concluded the letter by defining his affection in no uncertain terms, telling her, “Aren’t you frightened and horrified to know that I want to carry you off? I have a craving desire to come into physical contact with you, to put my arms right around you and hug you good and long.”[99]

The Prodigal Returns

At the end of the summer, Joseph F. Merrill set foot in a Latter-day Saint Church meeting for the first time in nearly two years. During his first summer in Chicago he found more time to attend church services; he wrote about attending chapel services held on behalf of the university every day and mentions the meetings of the Students’ Christian Association.[100] Now back in Chicago, with only weeks before his return to Utah, he saw a notice in a newspaper about a meeting of Latter-day Saints. After a journey of twelve miles on streetcars and on foot, Joseph found the meeting in a “pleasant” hall with “a saloon on either side of the ground entrance.” Inside was a small congregation holding a fast and testimony meeting. Joseph walked in during the middle of a Sunday School class—the meeting had started a half hour late. Joseph noted with warm amusement that the presiding elder was “a Scandinavian and does not speak English very well.” The superintendent of the Sunday School was a German who also struggled to speak English. Despite the language barriers, Joseph was clearly delighted to be back in the company of the Saints. “They seem to be a very sociable set of people,” he wrote. “After meeting instead of going home they remained to enjoy themselves in social ‘confab.’” Joseph also noted, “the place of the meeting is so far away that I doubt if I get out there very often,” and there are no indications that he returned to the tiny branch for Sunday services during his remaining six weeks in Chicago.[101]

Pondering his return home, Joseph made an interesting comparison, writing, “Is Utah the promised land? . . . If I were going to answer my own question I should say yes with both hands up. It is my Mecca, the seat of all my fairy day dreams.”[102] He remained in the faith, committed to Laura, and yet there is still a slight tone of defiance in his attitude toward the faith of his youth. “The church should not go into politics, nor should politics go into the church. The latter is even worse than the former,”[103] he wrote in one of his final letters from Chicago. It was with this mindset that Joseph boarded the train to return home to Utah for the first time in nearly two years.

He was returning to an uncertain future. He came back with no degree, an uncertain position at the university, and even some ambiguity in his relationship with Laura Hyde. Decades later, he wrote autobiographically of his feelings of conflict during the long ride: “I was going to Utah with my mind convinced it would be well for me to avoid public activity in Church service. . . . I resolved in my public capacity to be neutral towards both [Church and anti-Church] factions.” He had firmly resolved during his earlier teaching stint that “I must exhibit no partisanship else to that extent I might endanger the good work of the University,” and during the return his feelings remained unchanged. He committed to a path between the Latter-day Saint and Gentile factions in Utah, playing the role of the erudite scholar who was above the fray of tribal warfare in his provincial mountain home.[104]

He vividly remembered not the date but the time, about ten o’clock in the morning, as he was riding westward across the arid plains of Wyoming, when he experienced the second recorded theophany of his life. He was reading a Salt Lake newspaper and saw a notice regarding the appointment of Richard R. Lyman, a fellow student from his time in Michigan, as the superintendent of the Young Men’s Mutual Improvement Association, the Church auxiliary tasked with leading the charge to steel the Latter-day Saint youth against the encroaching influence of Babylon. He then recalled, “To myself I said ‘Congratulations, Richard.’ No sooner had these words passed through my mind than I was surprised by the words ‘You are to be his first counselor.’ These last words were not read from the paper or audibly spoken in my ears but they were forcibly impressed upon my consciousness as if they had been uttered in thunderous tones. I shook. ‘Is not this strange?’ I thought.”[105]

He was not at the end of his schooling, fixed in his professional course, or certain of anything in his future. But this moment, according to Joseph, marked the end of his desires to serve as a neutral but friendly observer to the travails of the Church, and the beginning of his career as an enthusiastic partisan for the faith. His time in the East was an odyssey of spiritual, political, and philosophical exploration, but it ultimately returned him to the same point. Recognizing his status as a returning prodigal, his first communication to Laura upon his return home contained only three words:

Laura Hyde,

Kill the calf.

Joseph.[106]

Notes

[1] Joseph F. Merrill to Annie Laura Hyde, 23 June 1897, box 14a, folder 7, Joseph F. Merrill Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University (BYU).

[2] Merrill to Hyde, 22 July 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[3] Thomas W. Simpson, American Universities and the Birth of Modern Mormonism, 1867–1890 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 28. For a list of the Latter-day Saint students attending these universities, see Simpson, American Universities, 129–61.

[4] Merrill to Hyde, 27 November 1895, box 14a, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[5] Hyde to Merrill, 14 September 1895, box 14a, folder 9, Merrill Papers, BYU. All letters from Annie Laura Hyde are designated as being written in Salt Lake City.

[6] Hyde to Merrill, 25 August 1896, box 14b, folder 3, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[7] Merrill to Hyde, 4 August 1985, box 14a, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[8] Merrill to Hyde, 4 August 1895, box 14a, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[9] Hyde to Merrill, 26 June 1895, box 14a, folder 9, Merrill Papers, BYU (emphasis in original).

[10] Marriner W. Merrill Journal, 19 September 1895, in Merrill, Marriner Wood Merrill, 191–2.

[11] Hyde to Merrill, 25 September 1895, box 14a, folder 9, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[12] Merrill to Hyde, 29 September 1995, box 14a, folder 5, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[13] Merrill to Hyde, 29 September 1895, box 14a, folder 5, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[14] Merrill to Hyde, 17 November 1895, box 14a, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[15] Merrill to Hyde, 9 July 1895, box 14a, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU (emphasis in original).

[16] Merrill to Hyde, 9 July 1895, Merrill Papers, BYU (emphasis in original).

[17] Hyde to Merrill, 25 September 1895, box 14a, folder 9, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[18] Hyde to Merrill, 8 December 1895, box 14a, folder 10, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[19] Hyde to Merrill, 8 December 1895, box 14a, folder 10, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[20] Merrill to Hyde, 2 August 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[21] Gene A. Sessions, ed. Mormon Democrat: The Religious and Political Memoirs of James Henry Moyle (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1998), xv.

[22] Moses Thatcher, Marriner Merrill, and Alonzo Hyde all held stock in John Beck’s Bullion Beck mine in Eureka, Utah, as did a number of influential Church leaders including George Q. Cannon, Charles O. Card, L. John Nuttall, and George Reynolds. The legal disputes over the mine and its mismanagement by Beck may have been a contributing factor in the increasing strife between Marriner Merrill and Thatcher. See Edward Leo Lyman, “The Alienation of an Apostle from His Quorum: The Moses Thatcher Case,” Dialogue 18, no. 2 (Summer 1985), 68; and Marian Skeen Merrill, Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill and Annie Laura Hyde Merrill (Salt Lake: printed by author, 1979), 6.

[23] Lyman, “Alienation,” 73.

[24] Edward Leo Lyman, ed. Candid Insights of a Mormon Apostle: The Diaries of Abraham H. Cannon (Salt Lake City: Smith-Pettit Foundation, 2010), 581–2.

[25] Abraham H. Cannon, diary, 17 November 1895, see Kenneth W. Godfrey, “Moses Thatcher in the Dock: His Trials, the Aftermath, and His Last Days,” Journal of Mormon History, 24 no. 1 (Winter 1998), 66.

[26] Lyman, “Alienation,” 77.

[27] Hyde to Merrill, 18 November 1895, box 14a, folder 10, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[28] Quoted in Lyman, “Alienation,” 80–81.

[29] Hyde to Merrill, 6 April 1896, box 14b, folder 2, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[30] Hyde to Merrill, 6 April 1896, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[31] Hyde to Merrill, 7 October 1895, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[32] Merrill to Hyde, 1 March 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[33] Maria Merrill to Joseph F. Merrill, 23 February 1896, box 14b, folder 7, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[34] Maria Merrill to Joseph F. Merrill, 23 February 1896[?], box 14b, folder 7, Merrill Papers, BYU (some punctuation added). While Maria Merrill usually did not add a notation of the year in her letters, it is clear from the context that this letter was mostly likely written in 1895, during the midst of the Moses Thatcher controversy.

[35] Merrill to Hyde, 1 March 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[36] Hyde to Merrill, 1 March 1896, box 14b, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[37] Hyde to Merrill, 11 March 1896, box 14b, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[38] Merrill to Hyde, 14 June 1896, box 14, folder 2, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[39] Merrill to Hyde, 12 January 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[40] Merrill to Hyde, 9 August 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[41] See Susan Jacoby, The Great Agnostic: Robert Ingersoll and American Freethought (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013).

[42] Merrill to Hyde, 15 December 1895, box 14a, folder 5, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[43] Merrill to Hyde, 15 December 1895, box 14a, folder 5, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[44] Merrill to Hyde, 11 October 1896, box 14a, folder 6, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[45] Joseph F. Merrill, “Some Fundamentals of Mormonism,” Church News, 7 December 1946.

[46] Merrill to Hyde, 7 June 1896, box 14, folder 2, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[47] Merrill to Hyde, 7 November 1895, box 14a, folder 10, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[48] Merrill to Hyde, 7 June 1896, box 14, folder 2, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[49] Hyde to Merrill, 12 June 1896, box 14b, folder 2, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[50] Hyde to Merrill, 12 June 1896, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[51] Hyde to Merrill, 14 August 1896, box 14b, folder 3, Merrill Papers, BYU. The family difficulties described in this letter appear to involve some legal troubles concerning Laura’s father, Alonzo Hyde. I have been unsuccessful in determining exactly what the difficulty was, but it is clear from Laura’s letters that during this time her family was under considerable stress.

[52] Hyde to Merrill, 1 March 1896, box 14b, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[53] See Carol Cornwall Madsen, An Advocate for Women: The Public Life of Emmeline B. Wells, 1870–1920 (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2006); and Leonard J. Arrington, “Emmeline B. Wells: Mormon Feminist and Journalist,” in Forgotten Heroes: Inspiring American Portraits from Our Leading Historians, ed. Susan Ware (New York: Free Press, 1998), 121–8.

[54] Hyde to Merrill, 14 September 1896, box 14b, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[55] Hyde to Merrill, 14 September 1896, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[56] Merrill to Hyde, 20 September 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[57] Hyde to Merrill, 24 September 1896, box 14b, folder 3, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[58] In organizing the Relief Society, the Church’s official women’s organization, Joseph Smith said he intended to “make of this Society a kingdom of priests”; “Nauvoo Relief Society Minute Book,” 30 March 1842, p. 22, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed 15 March 2014, http://

[59] Merrill to Hyde, 27 September 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[60] Merrill to Hyde, 27 September 1896, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[61] Hyde to Merrill, 25 August 1896, box 14b, folder 3, Merrill Papers, BYU. For background on Emmeline B. Wells, see Leonard Arrington, “Emmeline B. Wells: Mormon Feminist and Journalist,” in Forgotten Heroes, ed. Susan Ware (New York: Free Press, 1998), 121–128.

[62] Merrill to Hyde, 27 June 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[63] Merrill to Hyde, 12 July 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[64] Michael Kazin, A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan (New York: Knopf, 2006), 61.

[65] R. Hal Williams, Realigning America: McKinley, Bryan and the Remarkable Election of 1896 (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2010), 85.

[66] Merrill to Hyde, 12 July 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[67] Merrill to Hyde, 12 July 1896, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[68] Hyde to Merrill, 20 September 1896, box 14b, folder 3, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[69] Merrill to Hyde, 13 September 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[70] Hyde to Merrill, 4 November 1896, box 14b, folder 3, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[71] Merrill to Hyde, 28 February 1897, box 14a, folder 7, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[72] Merrill to Hyde, 28 February 1897, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[73] Merrill to Hyde, 27 June 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[74] Hyde to Merrill, 11 November 1896, box 14b, folder 3, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[75] Merrill to Hyde, 28 February 1897, box 14a, folder 7, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[76] Hyde to Merrill, 21 August 1896, box 14b, folder 3, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[77] Merrill to Hyde, 12 July 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[78] Hyde to Merrill, 8 August 1897, box 14b, folder 6, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[79] Merrill to Hyde, 21 June 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[80] Merrill to Hyde, 18 June 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[81] Merrill to Hyde, 15 July 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[82] Hyde to Merrill, 21 August 1896, box 14b, folder 3, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[83] Hyde to Merrill, 6 June 1897, box 14b, folder 5, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[84] Merrill to Hyde, 24 June 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[85] Hyde to Merrill, 19 October 1896, box 14b, folder 3, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[86] Hyde to Merrill, 31 January 1897, box 14b, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[87] Merrill to Hyde, 7 February 1897, box 14a, folder 7, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[88] Merrill to Hyde, 6 July 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU (some punctuation added).

[89] Hyde to Merrill, 14 August 1896, box 14b, folder 3, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[90] Hyde to Merrill, 20 September 1896, box 14b, folder 3, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[91] Merrill to Hyde, 7 February 1897, box 14a, folder 7, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[92] None of Merrill’s debtor notes are found in his official papers, but in a collection of unorganized files contained at the Church History Library in Salt Lake City, there is a letter from Marriner Merrill to Joseph sending funds; Marriner W. Merrill to Joseph F. Merrill, 13 March 1890, box 2, folder 8, Joseph F. Merrill Collection, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. There are also three promissory notes dated 13 March, 15 March, and 1 April, 1897, box 2, folder 11, MSS 22972, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[93] Merrill to Hyde, 28 March 1897, box 14a, folder 7, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[94] Merrill to Hyde, 17 April 1897, box 14a, folder 7, Merrill Papers, BYU (emphasis in original).

[95] Merrill to Hyde, 23 May 1897, box 14a, folder 7, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[96] Maria Merrill to Joseph F. Merrill, 25 April 1897, box 14c, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[97] Hyde to Merrill, 16 May 1897, box 14b, folder 5, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[98] Hyde to Merrill, 6 June 1897, box 14b, folder 5, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[99] Merrill to Hyde, 23 June 1897, box 14a, folder 7, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[100] Merrill to Hyde, 13 September 1896, box 14, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU. Chapel services were common at universities throughout the United States during this time. According to one study from the time, chapel services were held at twenty-two out of twenty-four schools surveyed and were compulsory for undergraduates at half of the schools. See George M. Marsden, The Soul of the American University: From Protestant Establishment to Established Nonbelief (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 170–71. Marsden also notes that daily chapel services “were typically neglected at scientific schools in the East” (171). Merrill never mentions attending chapel services at Johns Hopkins in his correspondence.

[101] Merrill to Hyde, 1 August 1897, box 14, folder 8, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[102] Merrill to Hyde, 4 July 1897, box 14a, folder 7, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[103] Merrill to Hyde, 22 August 1897, box 14a, folder 8, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[104] Joseph F. Merrill, “The Lord Overrules,” Improvement Era 37, no. 7 (July 1934): 413.

[105] Merrill, “The Lord Overrules,” 413.

[106] Telegram from Merrill to Hyde, Echo, UT, 13 September 1897, box 14a, folder 8, Merrill Papers, BYU.