Jupiter Ascendant

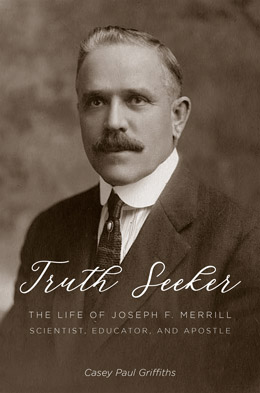

Casey Paul Griffiths, “Jupiter Ascendant,” in Truth Seeker: The Life of Joseph F. Merrill, Scientist, Educator, and Apostle (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 73‒106.

Joseph F. Merrill married Annie Laura Hyde on 9 June 1898, just nine months after he arrived back from the East. Joseph’s father performed the ceremony in the Salt Lake Temple. In his journal, Marriner notes a twenty-minute break in his busy meeting schedule to attend to these joyous duties.[1] Joseph and Laura’s correspondence disappears after Joseph stepped off the train in Utah because from that point on the couple remained nearly inseparable until Laura’s passing nineteen years later. This lack of correspondence deprives us of knowing how Joseph worked out his difficulties with Joseph Kingsbury and the university, but it is clear that the situation resolved itself. In the fall of 1898, Joseph returned to Johns Hopkins, this time accompanied by Laura. His return was made possible by a fellowship appointment from Hopkins, a high honor for a student. As if to make up for his earlier spiritual profligacy, the couple received an appointment to serve as missionaries during their time in Baltimore.[2] By spring he completed his thesis, entitled “Influence of Surrounding Dielectric on Conductivity of Copper Wires,”[3] and received his PhD. He was even elected to Phi Beta Kappa, a prestigious scholastic fraternity.[4] In the spring of 1899, he returned home, this time for good, and began his professional life at the University of Utah.

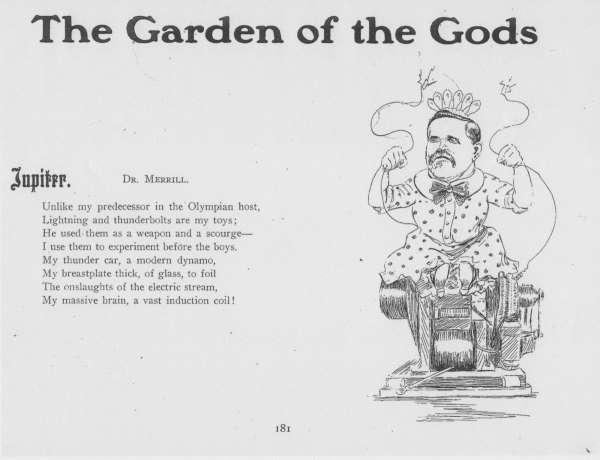

A satirical portrait of Professor Merrill depicting him as "Jupiter." University of Utah Yearbook, year unknown. Courtesy of Church History Library.

A satirical portrait of Professor Merrill depicting him as "Jupiter." University of Utah Yearbook, year unknown. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Frustrating setbacks had marked Merrill’s time in school, but the years 1899 to 1915 brought a period of almost uninterrupted ascendancy in his professional, ecclesiastical, and family life. It was the period of his life when he most successfully bridged the gap “between the devil and the deep blue sea,” winning success in the realms of academia and plaudits within the halls of his faith. He embraced his role as an ardent defender of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, applying his educational training to his ecclesiastical duties. His chief innovation, the seminary program, completely changed the direction of Latter-day Saint education and became the primary delivery method for religious education less than a decade after its creation. In 1906 Marriner W. Merrill passed away, and Joseph developed a new network of family and friends in Salt Lake City.[5] He and Laura built a happy home, and he became the doting father of six children. He became a respected and fiercely loyal member of the Democratic Party in Utah, earning enough confidence to contemplate a second career in politics. He served as the director and dean of the University of Utah’s School of Mines and Engineering from 1897 to 1928, playing a key role in the development of the university from a small frontier institution to a respected house of learning. A caricature published in the university yearbook early in Merrill’s tenure captures his perceived image among the faculty and students, labeling him “Jupiter” and depicting him in cartoon form as holding wires with live electricity in his hands, his head adorned with a crown of light bulbs, curiously clothed in a polka-dot dress, and sitting on top of an electrical generator. The drawing was accompanied by a whimsical poem:

Unlike my predecessor in the Olympian host

Lightning and thunderbolts are my toys;

He used them as a weapon and scourge—

I use them to experiment before the boys.

My thunder car, a modern dynamo,

My breastplate thick, of glass, to foil

The onslaughts of electric stream,

My massive brain, a vast induction coil![6]

It was a time of ascendance. Years later, Merrill himself spoke of it as the most “hopeful and happy” time of his life.[7]

The University of Utah

When Merrill returned from his second sojourn at Johns Hopkins, the University of Utah was settling into its new home on the dramatic rise to the east of the city, which provided a commanding view of the Salt Lake Valley. The university’s new location came through a grant from the United States that donated sixty acres of land from the Fort Douglas military reservation. Brigham Young and the city’s founders had envisioned the plot as the home of a university, but their dream was subsequently interrupted by the coming of a contingent of California volunteers in the Union army, who commandeered the grounds as their base.[8] The spot where forty years earlier the soldiers had calibrated their artillery to inflict maximum damage on the city below, should the Saints prove rebellious, now became the center for higher learning in the newly minted state of Utah. A series of four brick buildings began to rise surrounding a dirt road on the hill that was still playing host to the local flora of sagebrush and wild grasses. The rising complex was positioned at the end of 200 South, one of the wide, straight roads in the city’s grid system. Seen from the vantage point of one walking across this street, even today the campus gives the impression of a new city within the city, rising along with the valley terrain.

Officially, the university was nearly fifty years old, but developmentally it was still in its infancy. In 1900, the first year the new campus opened, the student body officially consisted of 834 students, though discounting the summer students the total number was 693. Of these remaining, only 193 attended as college students. The rest attended as high school students. It would be seven more years before the college students outnumbered those of high school age. In 1907 the university stipulated that “students must be a least sixteen years of age and of good moral character” if they wished to attend.[9] The campus was rustic and consisted of four sturdy brick buildings, the first of which was completed in 1899. Only the Physical Science Building, home to Merrill and his students, was ready in time for the campus to open. A local newspaper reported the scene of that chaotic first day: “There was a scene of crush, animation, and bustle that must have been highly gratifying to President Kingsbury and the professors associated with him. The professors sat at desks in various parts of the room and handled the newcomers with celerity and dispatch; everyone seemed delighted with the building, even though the carpenters were not yet out of the way.”[10]

Photographs from the period show the campus rising out of the raw land, no landscaping finished, and dirt roads connecting the locations on the campus. One of the most evocative images from the time shows a young lady dressed in a white blouse and dark skirt, and sporting a wide-brimmed hat, walking up a dusty, rock-filled road, with the peak of one of the university buildings rising slightly above the horizon. If the building’s root and some nearby telephone poles were eliminated from the photo, it would look as if the young woman were enacting a terrible wilderness drama.[11] By this point in American history the frontier was vanishing, but the little university and the city found themselves surrounded by reminders of the encroaching deserts all around. When one stands on the same spot over a century later, one’s eye is still drawn first to the tree-filled city below, then outward to the large nearby lake—an American Dead Sea—itself surrounded by the Bonneville Salt Flats, as barren and lifeless as any place on earth.

In this setting Joseph F. Merrill made his home for the next three decades. The university hosted his greatest triumphs and his deepest failures. The most common notation in his journals during these years was the oft-repeated entry “spent the day at the ‘U.’”[12] He later proudly claimed to have never taken a sick day during all his years at the university.[13] He also spent many Saturday afternoons and holidays at his desk.[14] His work consumed him, and with an energetic personality and the proper connections, he rose quickly through the university hierarchy. The School of Mines and Engineering was almost completely his creation, and its home on the campus today bears his name.

Creating the School of Mines

At just thirty-three years of age, Merrill took it upon himself to take the lead in establishing a school of mines at the university. Recognizing the advantageous location of Salt Lake City in the booming mining industry, Merrill led the charge to launch the new school and quickly made it one of the most prosperous on the campus. His closest compatriot in establishing the school was Richard R. Lyman. Already close, the two men developed a symbiotic relationship that served as the heart of the new institution. While Merrill was studying in the East, Lyman ran the fledgling school of mines almost single-handedly, teaching nearly all of the classes. Lyman’s duties included nine courses in engineering, three in surveying, and five in drawing. The school was small enough that Lyman somehow managed to meet the demands of each of these subjects as they arose.[15]

After Merrill returned home from his final year at Johns Hopkins, he took steps to formally establish the school of mines under Utah law. He took these steps in response to the rivalry developing between the University of Utah (U of U) and the other leading collegiate institution in the state, the Utah State Agriculture College (USAC) in Logan. He later wrote, “In the [18]90s we at the University felt deeply that we could not afford duplication of courses at the U of U and USAC. How could duplication be avoided? The simplest and best way was consolidation. So there was introduced in the Legislature of 1894 a bill to consolidate the two schools on the same site.” Two separate attempts to merge the two schools failed because of geographical rivalries. Merrill continued, “Logan and Cache County favored consolidation at Logan, but not otherwise. The majority of the U of U people favored consolidation at Logan or any other place named by the Legislature rather than no consolidation. Many people favor consolidation only in the Salt Lake Valley.”[16]

After Utah gained statehood in 1896, it became possible to receive a land grant from the federal government to establish a school of mines, and partisans supporting the University of Utah wanted it established there, rather than at the school in Logan. In 1901 Merrill, fearing that his planned work would be duplicated at USAC, approached the Utah State Legislature and personally wrote the bill establishing the School of Mines exclusive to the U of U. Passed by the legislature in March 1901, the bill wrote into law the stipulation that the school would be “under the arrangement and control of the Regents of the University of Utah.” The bill further directed the flow of federal money toward the new school, marking it as “the beneficiary of all land grants, appropriations, etc., made or to be made by the United States to the State of Utah for the establishment and maintenance of a School of Mines.” The bill then outlined the work of the school, which would offer “courses of instruction relating to mining, metallurgical, electrical, and such other branches of engineering as pertain to the pursuit and development in all its branches of the mining industry in Utah.”[17] With the school now an official part of the university, Merrill next moved to address the staffing question in the department, hiring Elias H. Beckstrand, who took over all of the mechanical engineering courses. This additional support freed Lyman to travel east and complete his PhD. Merrill, Lyman, and Beckstrand all became fixtures at the university, each remaining there for the majority of their careers.[18]

An ominous event took place in the midst of this progress when on 19 December 1901 the Physical Science Building caught fire and was completely gutted. The university newspaper related the details of the tragedy: “While the Salt Lake Theatre, full of students, professors, regents, alumni and friends was ringing with applause, laughter, and college yells, at the brilliant performance of the University Dramatic Club, the handsome new physical building of the university was being consumed by fire, in silent solitude.” As the crowd emerged from the theater, the glow of the fire on the hill was visible from thirteen blocks away. The account continues, “Professors left their wives and students left their sisters and sweethearts, in order to reach the scene with no delay,” rushing to the scene, running into the flaming structure to rescue books, lab equipment, and even the football uniforms of the university team. “There must have been nearly a thousand people on the scene, special cars going to and from the fire until long after midnight. President Kingsbury, a number the Regents and many of the professors and several of the students, all felt alike that a home was being destroyed.”[19] The fire was doused with the help of the local regiment from Fort Douglas, but the building, left as little more than a foundation and standing walls, was out of commission for nearly a year.[20]

Merrill and his compatriots hardly missed a beat, quickly moving their work to the newly completed museum building. The university newspaper noted, “There was some talk among the discouraged engineers of several of them leaving for other mining schools, but all has now subsided now that the restitution of the loss has been so immediate.” The newness of the school actually worked in its favor because much of its physical equipment was still arriving. The school paper confidently noted that “the basement rooms of the new museum, now in course of construction, will be fitted up temporarily for both recitation and laboratory work in chemistry, physics, and mineralogy, when work in these subjects will be in full blast.” The discouraged engineering students resolved to stay and rebuild, and the paper reported that “the Utah State School of Mines, still boasts of being the greatest in the west, both in equipment, in natural advantages, and in severity of entrance requirements.”[21]

The school’s progress continued unabated, and Merrill’s energetic leadership began to bring substantial attention to the fledgling institution. In 1903 the state legislature appropriated forty thousand dollars for new buildings and equipment for the school. The fund was amplified by an overdraft of five thousand dollars used to provide the school with its own power plant.[22] Merrill himself was not above beating the bushes to draw funding for the school and its students. Feeling the imperative to jump-start research work at the school, Merrill personally approached Colonel Enos A. Wall, a wealthy mining creator, to offer a research fellowship of five hundred dollars annually.[23] The funds furnished the school’s handsome laboratory. The university newspaper boasted of the rapidly growing collection of mechanical equipment, listing “a 30 horse-power boiler, an eight horse-power steam engine, a six horse-power gas engine, together with all the other apparatus, such as indicators, meters, condensers, gaugers, necessary for work in steam and gas engines, boiler testing, water meters and condensers.”[24]

Merrill began to dip his feet into the waters of politics as he persuaded the Utah Territorial Legislature to pass several bills granting greater power and funding to his department. Nearly fifty years after the fact, he related his actions with glee in a letter to a historian compiling the history of the university: “The Legislature and Governor made into law a bill (I wrote it) legalizing the establishment of a school of mines at the University. . . . Before this I wrote another bill for the Legislature which became law without amendment, establishing the Department of Mining and Metallurgical Research. Next, I wrote another bill, which also became law giving each biennium $15,000 for six $750.00 graduate fellowships.”[25]

The coup de grâce in Merrill’s legislative wrangling came in the establishment at the university of an official experiment station of the United States Bureau of Mines. He wrote, “By appointment I went alone to the Hotel Utah and met the Director of the Bureau who was glad to accept the invitation of the University, saying we were the first university in the country to offer cooperation. . . . This move was endorsed heartily by the mining industry of the West.” With this success under his belt, in 1909 Merrill was able to persuade the Utah state government to pass a bill (again, he cheerfully adds, “Which I wrote”) to establish the Utah Engineering Experiment Station.[26] The law grandly declared the purpose of the station to “carry on experiments and investigations pertaining to any and all questions and problems that admit of experiment and scientific methods of study and the solution of which would benefit the industrial interests of the State, or would be for the public good.”[27]

Merrill was a tireless promoter of the school. In an article aimed at recruiting new students, he pointed out that less than two years after it had opened, the School of Mines enrolled nearly one-third of the entire collegiate population at the university. Pointing out the rapidity of the school’s growth, Merrill wrote, “Nothing less was to be expected. Why? it may be asked. The answer is, because the Mining school gives what a very large proportion of the young men of Utah who go to college want—an industrial training.” Merrill’s words, describing the school’s prospective students, served as a description of his own personal rise, with allusions to his ascent from working the soil to the higher work of academia: “The young men of this inter-mountain country, they all, with few exceptions, have to work. But they are ambitious to bring out the best there is in them. They do not want to follow when they are capable of leading. They do not want always to occupy menial positions—those that demand ability and training—to be filed by importations from other states. Hence they want . . . an education that truly develops every side of their whole being and stores their minds with useful knowledge.” He concluded, “It is said that practical men are needed everywhere, men who can think, and men who can do. It is just such men that the courses of the School of Mines will develop.”[28]

Merrill’s work became apparent as the school’s growth accelerated. From 1901 to 1910, the number of degrees awarded by the school rose from just two to forty-seven, five of them graduate degrees.[29] The resources of the university flowed into the School of Mines and Engineering. A financial report for 1901–11 showed expenditures of the School of Mines at $4,050, just over 50 percent of the expenditures on all of the departments of the university. The budget of Merrill’s department nearly quadrupled the expenses of its next closest competitor, the Normal (Teaching) School, which reported expenses of $1,325.[30]

Merrill was also a founding father of another distinctive part of the university experience, the collegiate sports program. Even during his student days at the University of Deseret, Merrill was among the first students to gather friends and acquaintances to play baseball. Later he witnessed some of the earliest games of college football played at the University of Michigan. When he arrived back from his doctoral studies, he began urging President Kingsbury to hire a professional football coach as a member of the faculty.[31] In 1904 Kingsbury hired Joseph H. Maddock, fresh from a string of outstanding personal performances in football at the University of Michigan, where he was an all-American tackle on the championship team of 1903. Maddock was designated as the athletic director and instructor in physical culture, and led the football team to a streak of victories against its intermountain rivals.[32] Merrill himself was a lineman on the faculty football team from 1906 to 1912. A sports enthusiast to the core, Merrill served on the board of the University Athletic Association from the turn of the century onward, and as the chairman of the Athletic Council from 1910 until 1916.[33] As the faculty representative in the Rocky Mountain Athletic Conference, he persuaded the schools in nearby Colorado to accept Utah as a conference member. He even led the effort to provide sod for the football field, with the university newspaper pronouncing him “the prime mover in this scheme” and declaring that “owing to his [Merrill’s] efforts Utah will have a most excellent gridiron. He deserves the good will of every student and their aid in all that they can to make the work a success.”[34]

Merrill not only expressed his enthusiasm for the thrill of athletic competition but also showed genuine feeling for the athletes themselves. When a badly injured football player was brought into the gymnasium and no one took responsibility for his care, Merrill was deeply moved. He wrote to the university board requesting medical care and supervision for student athletes. The board accepted Merrill’s suggestion and made arrangements to help the injured players.[35]

Within a few years, Merrill became one of the most popular professors on campus. With the success of the School of Mines and Engineering, his skill in dealing with the state legislature, and the crowd-pleasing nature of the athletic programs, he seemed marked for advancement. As early as 1902, just three years after his return from his schooling in the East, he was appointed to serve as acting president of the university in Kingsbury’s absence.[36] From this time until 1913, it was a regular practice for the university’s Board of Regents to appoint Merrill to act in Kingsbury’s absence, effectively making him the vice president of the university.[37] Within only a short span of years, Merrill went from fearing that he may not hold any position at the university to a place of status and leadership within its ranks.

Family Life

Joseph Merrill’s ascendancy at the university was paralleled by the happiest years of his domestic life. When he and Laura returned from Baltimore in 1899 with one child, Joseph Hyde Merrill, in tow, they soon began adding to the family, roughly at the rate of one new addition every other year over the next decade. While the family was still living in a rented house, a little girl, Annie, was born in 1900. Within three years, Joseph and Laura completed their own home and added another little girl to the family, Edith, born in 1903. The Merrill home continued to fill with the addition of three more boys, Rowland (1904), Taylor (1906), and Eugene (1908). The final addition to the family and the namesake of her mother, Laura, came in 1915.[38]

The family home combined the urban sensibilities of Laura’s upbringing with Joseph’s attempt to re-create on a smaller scale the farm of his youth. Situated on a fairly large lot with Lucerne pastures on both sides, the Merrill homestead featured a barn, a vegetable garden, and a small orchard with apple, cherry, peach, and plum trees surrounded by raspberry, red currant, and gooseberry bushes. According to later descriptions provided by the children, the family plot also housed dozens of different animals, including chickens, rabbits, guinea pigs, “an occasional lamb, dog or cat,” and even a Jersey cow to provide milk for the family.[39] The lot was surrounded by a picket fence, water was supplied by an irrigation ditch, and in front of the house was a dirt road busy with the traffic of the burgeoning young city. In the summertime, a favorite family pastime consisted of sitting on the porch, Joseph reading a newspaper with a young child in his lap, flanked by Laura holding another child, watching the street cars replete with “genteel ladies” wearing large hats trimmed with ostrich plumes.[40] The family itself owned neither an automobile nor a buggy and depended on the city’s system of electric streetcars for transportation.[41] Their daughter Edith lauded the tiny farm as “the ideal self-sustaining, suburban family home.”[42]

Laura presided over the home, taking to domestic life with gusto. Descriptions of her life from this period are drawn almost entirely from her daughters, who saw her as the ideal homemaker. Her daughter Annie later wrote, “I felt she could do anything. She made lovely dresses and pretty white aprons trimmed attractively with embroidery for us girls. She made the boys’ shirts and all of our underclothing and sleep wear. She made beautiful net curtains with lace insets. She was an excellent cook and loved to entertain at dinner parties.”[43] The work of managing such a large household must have been exhausting, but Laura was assisted by a succession of hired girls, usually German speaking, with whom she furthered her study of their language.[44]

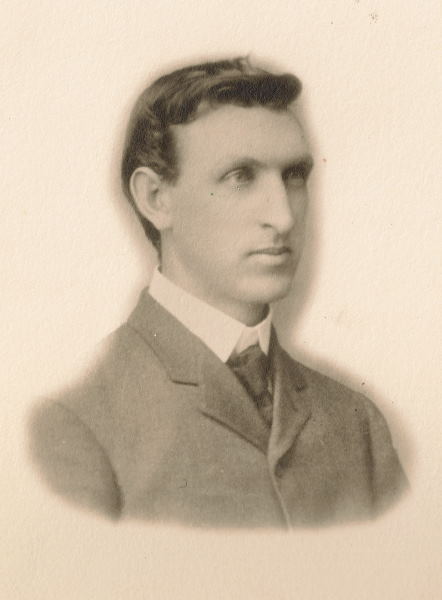

Joseph and Laura Merrill with their children around the time the seminary program was founded (1911). Courtesy of Annie Whitton.

Joseph and Laura Merrill with their children around the time the seminary program was founded (1911). Courtesy of Annie Whitton.

Laura rose early in the morning to perform her chores. Her dress and appearance were simple: she wore no makeup and arranged her curly blond hair, gradually darkening with age, in a bun on top, gentle strands waving about her face. In the afternoon, with the household work finished, she changed into a fresh dress and was often found reclining on the large leather couch in the front room reading a book when the children arrived home from school. Her evenings were often filled with social occasions. One of the children remembered, “I used to love to watch her and papa dress in evening clothes. They looked so happy and handsome. Men then wore tails for formal wear and papa and mama went out to such affairs quite often, always going in the street car.”[45]

In addition to being a skilled homemaker, Laura was an impressive community organizer. She was a charter member of the Daughters of Utah Pioneers (DUP) when it was founded by her mother in 1901, and she later served as president of the organization from 1913 to 1915.[46] She was also president of the U of U Faculty Women’s Club (1912–13) and was active in other prominent clubs throughout the city.[47] She remained remarkably progressive for the era. During one meeting she sponsored during her tenure as president of the DUP, she invited “Madame Bonnin, one of the few Indian women college graduates,” to speak at a gathering held in her home. Throughout the summer of 1914, Laura sponsored a course of study on Native Americans, focusing on their “life, customs, legends, and religion.”[48]

Laura was devout in her religious practices and was an active member of the local Latter-day Saint congregation. Her daughters remembered her wearing the religious clothing, called garments, worn underneath regular clothes by all temple-attending Latter-day Saints, and she adhered to the strictest standards of modesty prescribed at the time. One daughter recalled, “I remember mama sitting by the hot, coal range stirring and bottling the bubbling fruit. She wore the customary clothes of the time. Garments had legs to the ankles and sleeves to the wrists. Shoes were high-laced. Boned corsets held up the stockings and ‘gave support’ to the back and abdomen. Petticoats and skirts were ankle length and sleeves to the wrists. Dresses were protected by aprons tied around the waist.”[49]

While she manifested a devout nature, Laura also demonstrated an open and warm temperament. One child recalled, “I don’t recall her ever saying an ugly word or speaking loudly or in anger or losing her temper or crying. The latter I saw only once, when papa telephoned her to say her father’s neighbors found him dead, sitting in his living room bay window seat. She was gentle, cheerful, kind, uncomplaining, and I never knew her to strike one of the children.”[50] Other relatives commented on her sunny nature, and Joseph’s younger brother Melvin wrote in a letter, “You did capture a peach of a wife.”[51] Merrill idealized his wife and in his later years admonished all his daughters to remember their mother. Years after Laura’s death he wrote to Edith, “She was ambitious, but I think her dominant characteristic was loyalty. No man ever had a more devoted and loyal wife than I had—your mother.”[52] To his daughter Annie he wrote, “Mama is your pattern. No children ever had a better mother than my children. She was loyal, devoted, sweet, self-sacrificing—all to the highest degree. She is the best possible model for all her children.”[53]

Memories of the Merrill home were undoubtedly idealized in the minds of the children, but they have their own warm reminiscences about the family life of their youth. The children passed the hours playing hopscotch, marbles, or jacks, raising animals, or simply sitting on the front porch watching the local traffic pass by. Their daughter Annie remembered, “Papa would read the newspaper while mama sat in a Morris chair with a baby on her lap—a child on each arm of the chair, the boys on the floor listening or playing marbles and she would tell or read us stories. She was an excellent storyteller.”[54] Surprisingly, Laura’s aptitude for telling stories directly led to her husband’s most far-reaching and enduring educational innovation.

“A New Institution in Religious Education”

Because Latter-day Saints emphasize the role of divinely appointed prophetic leadership, there is a tendency for both Latter-day Saints and their observers to believe that every significant program or innovation originates at Church headquarters and begins within the higher echelons of the Church hierarchy. Those familiar with the Latter-day Saints often speak of the central base of Church operations as a kind of Mount Sinai, where instructions are summarily dispensed and then carried out by the dedicated faithful. Just as often, however, the most influential movements within the faith begin on a grassroots level, spread throughout the general membership of the Church, and then make their way to the hierarchy. It was in such a way that what is perhaps Joseph F. Merrill’s most ingenious and far-reaching innovation came to spread throughout the Church.

As the Latter-day Saints moved from a semiautonomous kingdom within the larger boundaries of the United States to a more integrated and mainstream position within American society, one of the most nettlesome issues came in the question of the education of Latter-day Saint youth. As the Saints entered a major transition in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it sought new ways to use education as a tool to transmit its doctrines and values to future generations. In the formative years of the Church, between 1847 and 1879, public schools in the Latter-day Saint community were essentially parochial schools that served communities in the Great Basin. Later, as Protestant-sponsored schools came to the region, scattered attempts were made to launch stake academies.

In response to the Utah Territorial Legislature’s passing of the Free School Act (1890), the Church launched a coordinated effort to build a Churchwide school system, resulting in the launch of a collection of academies scattered throughout the Intermountain West.[55] Even before the Free Schools Act was passed, Church leaders began to express alarm over the impact of having Latter-day Saint youth educated in secular schools. They were even more alarmed by the efforts of the coalition of Protestant denominations consciously establishing “Christian” schools for the purpose of converting Mormon children from the faith of their parents.[56] In 1888 the First Presidency of the Church announced the official creation of a Church Board of Education, stating, “We feel that the time has arrived when the proper education of our children should be taken in hand by us as a people. . . . Religious training is practically excluded from the district schools. The perusal of books that we value as divine records is forbidden. Our children, if left to the training they receive in these schools, will grow up entirely ignorant of those principles of salvation for which the Latter-day Saints have made so many sacrifices.”[57]

The letter captures the centrality of religion in the lives of the Saints. Simply put, it was unfathomable for Latter-day Saint parents to think of enrolling their children in a school where scripture was not part of the regular curriculum. Because the teaching of sectarian doctrine was written into the bill establishing the state’s public schools, Church leaders saw no alternative but to establish their own system of schools throughout the Intermountain West. So Latter-day Saint leaders engaged in direct competition with the public schools.

The academy system, a network of Church-sponsored high schools, proved to be relatively short-lived. While numerous factors were involved, the most critical considerations in the short life of the Church schools were financial. Church members enthusiastically heeded the call, and more than forty academies were established throughout the region with varying degrees of success. The Church schools charged tuition and had difficulty competing with free public high schools that were spreading throughout the region, and Latter-day Saint parents had a difficult time supporting both systems. Further, the massive resources needed to operate the schools meant that only large communities hosted academies. Smaller settlements often sent their children to board at Church schools during the winter, but the need for all hands in the agrarian economy of the rural areas made attendance a sacrifice. Because parents struggled under the burden of supporting public education through taxes and Church education through tuition and tithing, the Church schools began a slow decline at the turn of the century, never recovering despite the pleas of Church leaders.[58]

A more innovative response to the rise of the public schools came in the creation of the Religion Class program. Labeled by one historian as “Utah’s Educational Innovation,” these supplemental classes represented a novel approach to the question of church and state in public education.[59] By October 1890 a proposal emerged for a series of “daily theological classes in those settlements where church schools could not be established.”[60] For the sake of convenience, officials determined to convene these after-school classes in the public schoolhouses, led by the local teachers.[61] Although he initially favored building additional private schools, Karl G. Maeser, the superintendent of Church schools, later wrote that supplementary religious education, with its capacity to provide programs for each denomination, was the only answer to the “great defect in [the] public school system.”[62]

Although the Religion Class program was well intentioned and experienced varying measures of success throughout the 1890s, it suffered from a number of organizational flaws. These problems challenged both the program’s legal standing and its relationship with the other Church operations.[63] Furthermore, the Religion Class program raised significant questions about the nature of religious education in the public schools and the relationship of the Church to the state. For example, Utah law permitted school buildings to be used “for any purpose which [would] not interfere with the seating or other furniture or property,”[64] providing that rent was paid for the use of the building. Under these terms, Church officials felt they had “a perfect right to ask for the use of these buildings” for Religion Class purposes.[65] Additionally, Church leaders declared that they were “perfectly willing for the Catholics, Presbyterians, or any other religious denomination” to also use the buildings for religious purposes. Such statements, however, did little to pacify Utahns who were not Latter-day Saints; many argued that the practice violated the separation of church and state.[66]

While church-and-state questions plagued the Religion Class program throughout much of its history, the most significant complaints about the program ironically came from within the Church itself. Almost from its inception, some local Church leaders questioned the necessity of the program, which caused participation to fluctuate. Extant documents not only reveal high enrollment statistics for the program during many years but also demonstrate frequent discrepancies with regard to attendance. For example, for the 1899–1900 school year the program reported an enrollment of 19,701 students. The following year it reported an enrollment of 35,080, almost double the prior year, but at the same time, it reported an average attendance of only 17,628 students.[67] These radical statistical swings make it difficult to gauge the effectiveness of the program with any degree of certainty in the accuracy of its reports.

The two solutions that the Latter-day Saint hierarchy presented to the church-state problem each came with their own sets of problems. By the time Joseph F. Merrill was thrust into the midst of the difficulty in 1911, enrollment at the academies was in decline, and the Religion Program was unpopular with both the Saints and people not of the faith. In 1911 Merrill was called as a member of the Granite Stake presidency and was given responsibility over the education of the youth in the stake. Many of the younger members of the Granite Stake were attending public schools without access to the religious instruction offered at the Church academies. Recognizing this, Merrill began to search for some way to allow them to receive religious training.

The initial inspiration for the seminary program struck Merrill during an evening at home when Laura regaled the children with scriptural tales.[68] During the family meeting, Merrill was struck by his wife’s ability to tell stories from the Bible and the Book of Mormon to his own children. He later remarked, “Her list of these stories was so long that her husband often marveled at their number, and frequently sat as spellbound as were the children as she skillfully related them, preparatory to the children’s going to bed.”[69] When Merrill asked his wife where she had learned these stories, she replied that they had come from her Bible classes when she was a student at the Salt Lake Stake Academy. Merrill concluded, “If Bible study in school could thus make one girl an effective religious teacher of her children at home, it could do the same for other girls.”[70] Inspired by his wife’s example, Merrill became possessed by the idea of bringing the same kind of opportunity his wife had experienced at the Church academy to the students in his stake who were attending public schools.

Influenced by religious seminaries he had seen in Chicago during his own education,[71] Merrill worked out a plan to teach religion courses to Granite High School students, who would be released from their studies for one period a day. The teaching would take place in a building constructed by the stake adjacent to the high school. Merrill’s plan included some aspects of the earlier Religion Class program while improving on it in other ways. The new plan took advantage of the fact that the students were already gathered together at the high school during the day, and it made religion coursework a part of their regular studies. Holding the classes in a completely separate building from the high school solved many of the tricky church-and-state issues that had troubled the Religion Class program. In the months leading up to the 1912–13 school year, Merrill worked enthusiastically on the new program, meeting with the Granite Stake presidency, the Church Board of Education, and the Granite School District Board. He even met with the Utah State Board of Education to ensure the legality and acceptance of the new venture.[72]

The solution Merrill presented was elegant in its simplicity and reflected his desire to build a bridge between the worlds of the secular and the spiritual. Where the Church academies sought to compete with the public schools, and the Religion Classes created conflict with them, the “released-time” solution embraced them. A staunch advocate of public education, Merrill saw little danger in enrolling young Latter-day Saints in public schools; in fact, he sought to take advantage of it. At a 1911 meeting of the Utah Educator’s Association, Merrill embraced the growing number of public schools, saying, “The almost sudden springing into existence of high schools in all the larger communities of the state well nigh marks an educational revolution.”[73] Only a generation earlier, Brigham Young had publicly declared, “I am opposed to free education as much as I am opposed to taking away property from one man and giving it to another who knows not how to take care of it. . . . Would I encourage free schools by taxation? No!”[74] Now, only a few decades later, Merrill embraced the schools, saying, “All honor to those in every community who have labored incessantly to create this enthusiasm and give these institutions an auspicious birth. . . . You have builded better than you know. And time will demonstrate this fact. Your high schools will bring a new life, a higher life, a nicer life, into your communities.”[75]

Although earlier Church leaders had shunned public schools, Merrill recognized their dominance as inevitable and made them an integral part of his plan. The public schools would provide the transportation, housing, and costs of teaching all secular subjects. Instead of building an entire academy, the Church would simply build the theology department, placing it in a separate location and with the permission of school officials to allow Latter-day Saint students to leave for one period to gain their daily dose of gospel instruction.

Merrill’s plan was presented to the Granite District School Board in March 1912. His plan offered the Latter-day Saint students at Granite High a three-year course of study, with a year each on Old Testament, New Testament, and a final year focusing on Latter-day Saint Church history and doctrine. Merrill did not ask for credit for the final course of Church history, but he received assurances from the school board for the allowance of one-half credit for the classes in biblical studies, pending approval from the Utah State Board of Education.[76]

Merrill’s desire to create a spiritual safe haven for Latter-day Saint students was undoubtedly rooted in his own educational experiences in the East. He likely thought back to his religiously uprooted days in Baltimore and Chicago and designed the new program to provide mentors to the young in the faith as they ventured into the waters of academic study. He provided a detailed description of the kind of man he wanted to serve as the first teacher, writing, “May I suggest it is the desire of the presidency of the stake to have a strong young man who is properly qualified to do the work in a most satisfactory manner. By young we do not necessarily mean a teacher who is young in years, but a man who is young in his feelings, who loves young people, who delights in their company, who can command their respect and admiration and exercise a great influence over them.” Scholarship was also high on the list of qualifications for Merrill, who continued, “We want a man who is a thorough student, one who will not teach in a perfunctory way, but who will enliven his instructions by a strong, winning personality and give evidence of a thorough understanding of and scholarship in the things he teaches. A teacher is wanted who is a leader and who will be universally regarded as the inferior of no teacher in the high school.”[77]

Thomas Yates, a member of the Granite Stake high council, was chosen to serve as the first seminary teacher. Courtesy of the Yates family.

Thomas Yates, a member of the Granite Stake high council, was chosen to serve as the first seminary teacher. Courtesy of the Yates family.

The Granite Stake leaders selected Thomas J. Yates, a trusted member of one of its highest councils, to serve as the first teacher. Yates lacked many of the qualities typically associated with a youth minister. At the time he began his first assignment, Yates was a forty-one-year-old engineer working on the construction of a local power plant. He did not have, nor did he ever gain, any kind of professional training in how to teach religion. But Yates was just the kind of mentor to which a young Joseph F. Merrill would have reached out during his school days. Yates held a PhD in electrical engineering from Cornell University, one of the schools Merrill studied at during his sojourns in the East. Like Merrill, Yates was a child of the frontier, his earliest memories formed while living with his parents in a dirt dugout in Scipio, Utah. His academic demeanor belied a sly sense of humor. He liked to tell stories about pranks he had pulled as a boy, ranging from the industrious—he once completely disassembled a neighbor’s wagon then reassembled it on the top of a nearby shed—to the outrageous—on more than one occasion, Yates and his friends tipped over an outhouse that was still occupied.[78] Yates was also a staunch defender of the faith: he had left to serve as a missionary in the Southern United States less than two months after he was married.[79] He was a former student of the famed Latter-day Saint educator Karl G. Maeser, and before his graduate education he had served as a teacher and principal at Brigham Young Academy.[80] Yates was known for providing erudite gospel discussions mixed with wild stories about his youth, in which both bears and Indians chased him.[81]

With Yates joining him, Merrill launched headlong into preparations to have the new program ready by the fall. Yates was optimistic about the possibilities, though he recognized the difficulties involved in launching a whole new educational program. He explained, “This was a new venture. It had never been tried before. We could see wonderful possibilities[;] if it were successful[,] it would mean a complete change in the Church.”[82] All the while, Merrill and Yates continued to meet with school officials to smooth over any legal concerns and to coordinate the students’ schedules so that released-time seminary would be possible. The high school schedule of a typical student in 1912 consisted of a six-class day. Each student took five classes then had one period to use for study. Merrill and Yates worked with the school’s principal, James E. Moss, to gain permission for the students to attend a religion class during their free period if their parents requested it. Through several meetings, Yates was able to secure full cooperation from Moss and the faculty of the school.[83]

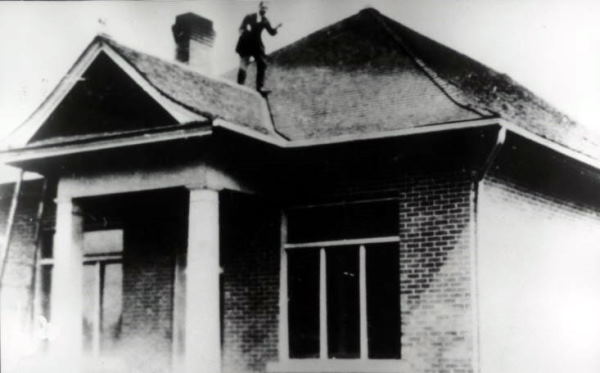

The original Granite seminary building, with a student, Paul Riemann, reenacting "Paul preaching from the rooftops." Courtesy of Church History Library.

The original Granite seminary building, with a student, Paul Riemann, reenacting "Paul preaching from the rooftops." Courtesy of Church History Library.

To fully enforce the decision to keep the seminary program completely separate from the high school, a new building had to be built. Yates took part in purchasing the land, designing the building, and even overseeing its construction. He later wrote, “It required considerable thought to plan this building. We did not know the number of students to provide for, and therefore the size of the classrooms, or the number of rooms. Provision had to be made for hanging wraps and boots etc. There was no precedent to guide us.”[84] In a move showing the fear of failure that many felt for the new institution, the structure was built to look like a common bungalow-style home, one story, with a low-pitched roof covering a simple rectangular plan.[85] If the new venture failed, the building could be sold as a family home. Early photographs of the Granite seminary building show an irregular pattern of bricks where a typical front door might have been found.

Frank Y. Taylor, president of the Granite Stake, borrowed $2,500 from Zion’s Savings Bank in the fall of 1912 to construct the building. The Church General Board of Education paid interest on the note, and when the Granite Stake could not pay, the board was compelled to pay off the principal. The building was begun only a few weeks before school started and was not finished until several weeks into the school year. Even when the structure was completed, its accommodations were Spartan. The building had four rooms: a cloakroom, an office, a small library, and a classroom. Furnishings in the classroom consisted of blackboards, armrest seats, and a stove. There were no lights. There were no regular textbooks other than the scriptures. The seminary’s entire library consisted of a Bible dictionary owned by Yates. The students made their own maps of the Holy Land, North America, South America, Mesopotamia, and Arabia.[86]

When the seminary opened in the fall of 1912, seventy students were enrolled. Construction on the seminary building was not actually completed until the third week of school, eliminating many prospective Latter-day Saint students who by that point in the school year already had full academic schedules.[87] Yates himself made a tremendous sacrifice in time and effort just to get to the building and teach. He would spend every morning working at the Murray power plant and then ride his horse to the seminary in time to teach during the last two periods of the day.[88] His salary for the first year was one hundred dollars a month.[89]

The sparse accommodations were complimented by Yates’s simple style. He later described his teaching method: “Students were asked to prepare a whole chapter in the Bible and then report to the class. Then the class would discuss it. No textbooks were used. The students did not have any form of recreation, there were no parties, no dances, no class affairs or anything in recreation to deviate from the regular pattern of things.”[90]

At the end of the school year, Yates decided to move on. The strain of traveling back and forth from Murray every day proved to be too much, and he chose as his replacement Guy C. Wilson, a professional educator who had recently moved to Salt Lake from Colonia Juárez, in Mexico, where he had served as principal of the local Church academy. Initially the seminaries were viewed as part of the religion class program and operated under the jurisdiction of the Religion Class Board. However, under the leadership of Wilson and other teachers, the seminary program spread and began to be seen as a viable alternative to the Church academies and Religion Classes. By 1918, just six years after the first seminary opened its doors, there were thirteen seminaries serving 1,528 students.[91] A decade later, nearly every Church academy had been closed in favor of the seminaries.[92] Throughout the remainder of the decade the seminary system began to pick up momentum, with more and more seminaries established throughout Utah, Idaho, and Arizona. By the end of the decade, there were a total of twenty seminaries in operation.[93]

Seminary also continued to gain legitimacy as an educational entity. In January 1916 the Utah State Board of Education officially approved high school credit for Old and New Testament studies in the seminaries.[94] As the decade continued, seminaries began to emerge as viable alternatives to the academy system, which continued to be eclipsed by the rapid expansion of public schools. Church President Joseph F. Smith felt that the academy system had reached the limits of its expansion and confronted the reality that the Church would “have to trim our educational sails to the financial winds.”[95] With the academies becoming too expensive to maintain, the seminaries offered a method of teaching religion in a less expensive way that could reach more students than the Church academies could.

While the released-time program started by Merrill has been recognized as the first of its kind begun on the secondary level, it was not created in a vacuum.[96] As early as 1905, an interdenominational conference in New York called on local schools to allow children to “absent themselves, without detriment” for the purpose of receiving religious education.[97] In 1914, just a few years after the first Latter-day Saint released-time program began, William Wirt, school superintendent in Gary, Indiana, launched a released-time program that became a pattern used in many states.[98] As these released-time religion programs spread around the country, the Church’s program blossomed as well, becoming the delivery method of choice for religious education in areas with Latter-day Saint populations large enough to justify it. While the development of released time was more dramatic in the Church-dominated regions of the Intermountain West, its growth mirrored the national expansion of released-time religion programs. By 1947 there were nearly two thousand communities with some form of religious instruction provided by various denominations on the released-time plan, represented in all states except New Hampshire.[99]

The Politician

Successful at the university, content at home, and triumphant in his ecclesiastical duties, Merrill also held political ambitions. Any aversion he had to partisan politics evaporated after his marriage to Laura, and he became more and more involved in the workings of the state Democratic Party. An avowed neutral during his days courting Laura, Joseph quickly became an ardent Democrat. One of his daughters observed his enthusiasm, writing, “I enjoyed watching papa jumping and dancing and whooping it up when a democratic candidate would win.”[100]

Merrill’s first taste of elective victory came in his association with the Utah Education Association (UEA). He was one of the founders of the organization, and in 1909 he came within a few votes of serving as the president.[101] The next year he defeated John A. Widtsoe, the popular president of the Utah Agricultural College, to become UEA president, and served from 1910 to 1911.[102] The public viewed UEA elections with great interest, and Merrill’s influence began to rise. Merrill’s educational connections through the UEA and his work at the university undoubtedly played a role in the relatively smooth reception of the seminary program.

With the taste of politics in his mouth, Merrill began to make inroads within the Democratic Party. In 1910 his name was put forth as a candidate for state representative, though he did not run.[103] In 1912 he was nominated by acclimation as a Democratic candidate for the Utah State Senate, and his portrait appeared on the front page of the Salt Lake Tribune alongside the other candidates for office.[104] As Merrill completed his term as president of the UEA, his political star was rising, and at the 1912 Democratic Convention some in the crowd even began to call for his candidacy as governor of the state. He was also becoming a popular speaker at Democratic rallies.[105] Young, energetic, and well respected in the community, Merrill looked to politics as the next great phase of his life’s work, and the rising prestige surrounding him suggested a bright future.

Dark Skies Ahead

Yet, in the midst of Merrill’s triumphs in the first decade of the twentieth century, some shadows loomed. His tranquil domestic life was disturbed by his wife’s health challenges. Around 1909 Laura was diagnosed with cancer. She underwent a series of operations, which eventually resulted in the removal of one of her kidneys.[106] The idyllic memories later shared by the Merrill children include descriptions of Laura’s long recovery from several taxing surgeries. In his efforts to help his wife recover, Joseph moved her out of the sweltering summertime heat of their home onto a carefully prepared bed on the house porch, where a large American flag was fastened to provide her with some measure of privacy. The 1909 operations excised the cancer but left behind a lingering fear of its return.[107]

Merrill’s sudden ascendance in the political arena also came with some potentially disturbing consequences. His position at the university was viewed as a public trust, and some members of the community began to criticize his involvement in partisan politics.[108] Merrill’s political aspirations also conflicted with Joseph Kingsbury’s strict policy of not allowing faculty members to run for political office. No documentary evidence exists of any conversation between Merrill and Kingsbury on the subject, but when Merrill accepted the nomination for state senate in the fall of 1912 he undoubtedly did so without the university’s permission, creating a situation primed to explode into conflict. No doubt, with his prestige as the second-in-command of the university and his status as the director of one its most influential departments, Merrill felt he could successfully reform school policy and begin his career in politics at the same time. At the height of his success, with all these factors converging, on the boundary of the brightest period of his life, Merrill was about to enter into his darkest time.

Notes

[1] Marriner W. Merrill Journal, 9 June 1898, in Melvin Clarence Merrill, ed., Utah Pioneer and Apostle: Marriner Wood Merrill and His Family (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1937), 227.

[2] Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4 vols. (Salt Lake City: Western Epics, 1971), 1:784–5.

[3] Twentieth-Fourth Annual Report of the President of Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1899), 78, https://

[4] Noted in the “Dedicatory Program for the Joseph F. Merrill Building at the University of Utah,” Utah State Historical Society Archives, P AM 5295 c. 1, 1.

[5] Lawrence R. Flake, Mighty Men of Zion (Salt Lake City: Karl D. Butler, 1974), 232.

[6] This paper was located in the Joseph F. Merrill Collection, box 2, folder 12, at the Church History Library, Salt Lake City. It is mislabeled as the 1932 Utonian, and I have been unable to find its original source. A paper from the same source in the collection contains a portrait of Joseph F. Merrill from around 1903, so the caricature and poem may be from that time.

[7] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 9 June 1935, box 1, folder 3, Joseph F. Merrill Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University (BYU).

[8] Dietrich K. Gehmlich, “A History of the College of Engineering, University of Utah” (unpublished document, 2003), 4–6, http://

[9] Ralph V. Chamberlin, The University of Utah (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1960), 254.

[10] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 253.

[11] Elizabeth Haglund, ed., Remembering: The University of Utah (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1981), 11.

[12] Joseph F. Merrill Journals, boxes 1–3, Merrill Papers, BYU. The number of entries containing this notation are too numerous to list here.

[13] JFM to University of Michigan Alumni Association, 4 February 1928, Merrill Papers, box 23, folder 3, BYU.

[14] JFM to Heber J. Grant, 27 February 1928, Merrill Papers, box 20, folder 3, BYU.

[15] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 268.

[16] Joseph F. Merrill to Ralph V. Chamberlin, 30 January 1952, box 15, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[17] “A Bill for the Establishment of a State School of Mines,” access number 2, box 5, folder 11, Presidential Papers of James E. Talmage and Joseph T. Kingsbury, University of Utah (U of U) Archives.

[18] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 268.

[19] “One Building in Flames,” University of Utah Chronicle, 14 January 1902, 179.

[20] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 239.

[21] “One Building in Flames,” 179.

[22] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 240.

[23] Merrill to Chamberlin, 30 January 1952, box 15, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU. Wall’s background is taken from “Baird Rewarded by Col. E. A. Wall,” Deseret News, 2 September 1902.

[24] “The New Mechanical Laboratory,” University of Utah Chronicle, 8 April 1902, 374.

[25] Merrill to Chamberlin, 30 January 1952, box 15, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[26] Merrill to Chamberlin, 30 January 1952, box 15, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU; Chamberlin, University of Utah, 270. A copy of the bill officially establishing the School of Mines may be found in the Presidential Papers of Joseph T. Kingsbury and James E. Talmage, access number 2, box 5, folder 11, U of U Archives.

[27] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 271.

[28] Joseph F. Merrill, “Concerning the Mining School,” U of U Chronicle, 12 May 1903.

[29] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 273.

[30] Minutes of the Board of Regents of the University of Utah, 2 July 1910, MSS B20, box 5, folder 15, Ralph V. Chamberlin Papers, Utah State Historical Society.

[31] Joseph F. Merrill, faculty biography, box 9, folder 6, pp. 1–2, Chamberlin Papers.

[32] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 303–4.

[33] Merrill, faculty biography, 3.

[34] “The Football Field,” University of Utah Chronicle, 6 December 1909, 3.

[35] Merrill, faculty biography, 3.

[36] “Alumni Society Favors Merrill,” Salt Lake Tribune, date unknown, University of Utah Faculty News Clippings, U of U Archives.

[37] Minutes of the University of Utah Executive Committee, 1 November 1913, U of U Archives.

[38] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill and Annie Laura Hyde Merrill Published by His Children (Salt Lake City: privately published, 1979), 8, 19, 43, 66, 81, 105, 115.

[39] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 43.

[40] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 10, 43.

[41] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 9.

[42] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 43.

[43] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 43.

[44] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 6.

[45] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 9.

[46] Barbara T. Dorigatti, “One Hundred Years of DUP, Pioneer Pathways 4 (2001): 160.

[47] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 10.

[48] “Indians Will Not Give Up Religion,” Salt Lake Tribune, 26 May 1914, 5.

[49] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 44.

[50] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 9.

[51] Melvin Merrill to Joseph F. Merrill, 29 October, year unknown (likely 1909), box 2, folder 6, Joseph F. Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[52] Joseph F. Merrill to Edith Merrill, 19 December 1929, box 14c, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[53] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 10.

[54] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 10.

[55] See Scott C. Esplin, “Closing the Church College of New Zealand: A Case Study in Church Education Policy,” Journal of Mormon History 37, no. 1 (Winter 2011): 86–114.

[56] John D. Monnett Jr., “The Mormon Church and Its Private School System in Utah: The Emergence of the Academies, 1880–1892” (PhD diss., University of Utah, 1984), 37–38.

[57] Monnett, “Mormon Church and Its Private School System,” 3:168.

[58] For an overview of the Latter-day Saint academy system, see Casey Paul Griffiths, “Life at a Church Academy: The Story of the Murdock LDS Academy in Beaver, Utah,” Mormon Historical Studies 14, no. 2 (Fall 2013): 29–53.

[59] D. Michael Quinn, “Utah’s Educational Innovation: LDS Religion Classes, 1890–1929,” Utah Historical Quarterly 43, no. 4 (Fall 1975): 379–89.

[60] Minutes of the Church Board of Education, 8 October 1890, D. Michael Quinn Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT; Alma P. Burton, “Karl G. Maeser, Mormon Educator” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1950), 106.

[61] “Program of Lund Day Exercises in Religion Classes,” 1912, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City; Anthon H. Lund, diary, 2 June 1890, in John P. Hatch, ed., Danish Apostle: The Diaries of Anthon H. Lund, 1890–1921 (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2006), 7.

[62] Maeser, School and Fireside (Salt Lake City: Skelton & Co., Publishers, 1898), 131.

[63] For a discussion of the successes and failures of the Religion Class program during the 1890s, see Brett D. Dowdle, “‘A New Policy in Church School Work’: The Founding of the Mormon Supplementary Religious Education Movement” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2011), 60–103.

[64] Revised Statutes, Sec. 1822, quoted in “Laws and Religion Classes,” in Journal History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 19 October 1904, Church History Library.

[65] Joseph W. McMurrin, in Conference Report, April 1902, 57.

[66] McMurrin, in Conference Report, April 1902, 57. In January of 1900, for instance, some residents of the rural town of Richfield, Utah, who were not members of the Church, signed a petition protesting the local school board’s decision to allow a Religion Class to be held in a state-owned building. “Religion in Public Schools,” Salt Lake Herald, 7 January 1900.

[67] Quinn, “Utah’s Educational Innovation,” 385. At its height in 1926–27, the Religion Class program reported an enrollment of 61,131 students. In the years for which the average attendance is available, peak attendance was 29,190 students.

[68] The two most complete accounts of the circumstances surrounding this meeting are Joseph F. Merrill, “A New Institution in Religious Education,” Improvement Era, January 1938, 55–56, and A. Theodore Tuttle, “Released Time Religious Education Program of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints” (master’s thesis, Stanford University, 1949). The first account was written by Merrill himself; the second draws from an interview conducted by A. Theodore Tuttle with Joseph F. Merrill.

[69] Merrill, “A New Institution,” 55.

[70] Merrill, “A New Institution,” 55.

[71] Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 168. Alexander cites an interview he conducted with Merrill’s daughter as his source for Merrill being inspired by the religious seminaries he saw during his time in Chicago. An interview conducted by one of the authors with two of Merrill’s grandchildren confirmed this story as common knowledge within the Merrill family. Annie Whitton and Joseph Ballantyne, interview by Casey Paul Griffiths, 17 November 2011, notes in author’s possession.

[72] Tuttle, “Released Time,” 57–59.

[73] John Clifton Moffitt, A Century of Service, 1860–1960, A History of the Utah Education Association (Salt Lake City: Utah Education Association, 1961), 317.

[74] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 18:357.

[75] Moffitt, A Century of Service, 317.

[76] William E. Berrett, A Miracle in Weekday Religious Education (Salt Lake City: Salt Lake Printing Center, 1987), 29.

[77] Joseph F. Merrill, “A New Institution,” 55.

[78] Thomas J. Yates, “Autobiography and Biography of Thomas J. Yates,” Church History Library, Salt Lake City, 127.

[79] Yates, “Autobiography,” 46.

[80] Yates, “Autobiography,” 17–18.

[81] Yates, “Autobiography,” 10. For a full profile of Thomas J. Yates, see Casey Paul Griffiths, “The First Seminary Teacher,” Religious Educator 9, no. 3 (2008): 114–30.

[82] Yates, “Autobiography,” 79.

[83] Berrett, A Miracle, 30; Yates, “Autobiography,” 80.

[84] Yates, “Autobiography,” 80.

[85] Thomas Carter and Peter Gross, Utah’s Historic Architecture, 1847–1940 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1988), 54.

[86] Charles Coleman and Dwight Jones, comp., “History of Granite Seminary” (unpublished manuscript, 1933), Church History Library, 6.

[87] Yates, “Autobiography,” 80.

[88] “New Building Dedicated at Granite, the Oldest Seminary in the Church,” Church News, 10 September 1994.

[89] Ward H. Magleby, “Granite Seminary, 1912,” Impact 1, no. 2 (Winter 1968): 9.

[90] LeRoi B. Groberg, as cited in Magleby, “Granite Seminary, 1912,” 9, 15.

[91] Seminary and Institute Statistical Reports, 1919–1953, Church History Department, Salt Lake City.

[92] Seminary and Institute Statistical Reports, 36.

[93] See Tuttle, “Released Time,” 71–74.

[94] See Minutes of the Utah State Board of Education, 5 January 1916, quoted in Tuttle, “Released Time,” 65–66.

[95] Minutes of the General Church Board of Education, 27 January 1915, Centennial History Project Papers, UA 566, box 24, folder 8, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, BYU.

[96] R. W. Wilkins, “Constitutionality of Utah Released-time Programs,” Utah Law Review 3 (1953): 329–39; E. L. Shaver, “Weekday Religious Education Secures Its Charter and Faces a Challenge, Religious Education 48 (January–February, 1953): 38–43; Tuttle, “Released Time,” 71.

[97] Donald Rex Gorham, “A Study of the Status of Weekday Church Schools in the United States” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1934), 3.

[98] Shaver, “Weekday Religious Education,” 19.

[99] Ross Patterson Poore, “Church-School Entanglement in Utah: Lanner v. Wimmer” (PhD diss., University of Utah, 1983), 99.

[100] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 20.

[101] John Clifton Moffitt, A Century of Service, 53; “Either Merrill or Welch for President,” Salt Lake Tribune, 29 December 1909; “Little Politics Not Harmful to Any One,” Salt Lake Tribune, 30 December 1909.

[102] Moffitt, A Century of Service, 63; “Merrill Victor Over Widtsoe,” Salt Lake Tribune, 31 December 1910, 4. At this same meeting the name of the Utah Teachers Association was changed to the Utah Education Association (UEA).

[103] “Democrats Have Many Aspirants,” Salt Lake Tribune, 20 September 1910, 1.

[104] “Democrats Name County and Legislative Ticket,” Salt Lake Tribune, 13 September 1912, 1.

[105] “Democrats in High Spirits at Primaries,” Salt Lake Tribune, 27 August 1912, 1; “Democratic Rally,” Salt Lake Tribune, 2 November 1910, 16.

[106] Joseph F. Merrill to Dr. Curtis F. Burnam, 17 November 1915, box 2, folder 2, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[107] Melvin Merrill to Joseph F. Merrill, 22 July 1909, box 2, folder 6, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[108] Joseph F. Merrill to A. C. Nelson, 17 February 1913, box 2, folder 10, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.