“Is It Not Strange?”

Casey Paul Griffiths, “'Is It Not Strange?,'” in Truth Seeker: The Life of Joseph F. Merrill, Scientist, Educator, and Apostle (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 107‒30.

Joseph F. Merrill lost the 1912 election. He was defeated along with the majority of the Democratic Party as a whole in the state of Utah. The Republican machine that was so dominant over Utah politics was too much to overcome, although cracks were beginning to appear in it during the first decade of the twentieth century. Part of the struggle Democrats faced came in the implied (but not official) sanction given to their opponents by the candidacy of Apostle Reed Smoot, who was now an incumbent United States senator. The Church fervently preached neutrality in its official politics, but the presence of Smoot on the Republican ticket made it difficult for Utahns to see the party as anything other than the quasi-official political choice of the state’s dominant religion. Smoot’s position as a senator, coupled with the popular presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, created a mood in Utah that favored the GOP, which won every election from 1900 to 1910 with a healthy majority.[1] But by 1912 the party’s grip on the state was beginning to loosen, and young Democrats like Merrill were hoping to take advantage of the change.

Several factors pointed to an end of the dominance of the Republican juggernaut. First, Roosevelt’s successor, William Howard Taft, was unpopular. Roosevelt himself was so unhappy with the direction of the Taft administration that he threw his own hat into the ring again. When Republican bosses blocked Roosevelt’s nomination, he formed his own party, the Progressives (“Bull Moose”), and aimed to win the presidency via a third-party route. With Roosevelt’s candidacy threatening to split the vote nationally and on the state level, the way was open for a Democratic resurgence. Further, leading the Democrats was the erudite and eloquent Woodrow Wilson.[2] A former university professor and president, Wilson represented all of Merrill’s future aspirations for himself.

On the local level, the Republican coalition ruling the state was beginning to come apart at the seams. Dubbed the “federal bunch” by the Salt Lake newspapers, Smoot and his cohorts brought together a powerful alliance of Latter-day Saint and nonmember interests within the state. By 1909 the state legislature consisted of sixty-one Republicans and two Democrats. Not surprisingly, when a joint session was held in 1909 to elect a new senator from the state of Utah, Reed Smoot received sixty-one votes, and William H. King, the Democratic candidate, only two.[3] Prohibition began to drive a wedge between the teetotaler Latter-day Saints and their of other faiths allies, who favored the sale of alcohol. Nevertheless, the Republican machine was still strong enough in 1912 to make Utah one of only two states that voted for Taft, the party’s establishment candidate.[4] The Republicans carried Utah in the presidential contest with 42,013 votes, compared to 36,579 for the Democrats and 24,171 for the Progressives. Merrill failed to win his race, but so did every other Democratic candidate who ran in the state, save one incumbent in the senate.[5] The acrimonious split in the Republican Party, however, gave the Democrats hope for the next election cycle. They could see that, with the right exploitation of the divisions in the ranks of their opponents, a way might open to end the Republican domination of Utah.

Underlying Tensions

There is no evidence of any conflict between Merrill and the university over his run for the state senate in 1912. The results of Merrill’s first foray into state politics were encouraging enough, though, that he began to prepare the way for his next campaign in 1914. At the same time, Merrill began to take steps to address the growing unrest among the faculty at the University of Utah. Resentment was on the rise due to the dictatorial policies initiated by President Kingsbury. The venerable Kingsbury, president since 1897, was an able administrator but began to alienate the faculty by cutting off contact between the university staff and the university’s Board of Regents. A generous historian of the university wrote, “The faculty had no regular means of contact with the Board excepting through the President, who in practice came to conduct himself as a representative of the Board rather than as a spokesman for the faculty.”[6] With a growing arrogance due to his long tenure, Kingsbury began to regularly bypass the faculty and take matters straight to the board.[7] As with nearly every conflict in the state, there was an unspoken tautness due to the continual charges that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints meddled in the affairs of the state. Many of the dissenters whispered of Church control at the university and favoritism among the faculty.

Merrill was caught in the middle of the rising tensions between the two factions due to his familial connection to Kingsbury, his uncle, and his increasing role as the unofficial spokesman for the faculty. Hoping to defuse these tensions, and with an eye to his own political ambitions, Merrill began an effort to reform the university before the problem got out of hand. In October 1913 Merrill, along with other members of the faculty, submitted a petition to the Board of Regents outlining several grievances. After a few opening lines commending the growth and prosperity of the school, the document cut to the chase: “We have been perturbed, therefore, because of certain recent acts which appear to have infringed upon the proper freedom of the individual instructors and to have raised a question as to the security of the tenure of office.” The petition diplomatically listed the most trivial problems first, complaining about mandatory physical examinations for the teachers that required them to pay their own fees to preapproved doctors. The next complaint spoke directly to Merrill’s political drive: “The purpose of the regulation concerning the acceptance of a nomination for political office is not well understood. If it is intended merely as a safeguard against neglect of duties arising from such candidacy it seems unnecessary.” The petition then took on an accusatory tone: “If it has any other purpose it appears to many of the faculty to constitute an infringement of the proper freedom of action on the individual.”[8]

The petition next addressed the charged atmosphere of the school: “Members of the faculty have been subjected to censure because they had expressed views upon debatable questions which did not conform with those of some other persons.” Without naming names, it cited the case of “a prominent member of the faculty . . . removed from his position without being fully informed as to the reasons for such action, and without being accorded a hearing.”[9] Merrill placed his own reputation on the line in making these charges of academic suppression. His position was the equivalent of a university vice president, and to the mercurial Kingsbury the act could be construed as a display of outright mutiny. Yet Merrill openly announced himself as the leader of the dissenting faculty on these questions. With a reckless boldness, the signature line on the petition read, “J. F. Merrill and 46 other instructors.”[10]

Merrill intended to stir the waters and start a serious conversation about academic freedom at the university, but, at least on the surface, the petition barely made a ripple. At the committee meeting where the petition was received, the school officials quickly filed it away without much fanfare for consideration at a future meeting. The petition was never mentioned again in the minutes, and the board quickly moved on to more pedestrian business without comment. Almost as much time in the meeting was devoted to Merrill’s duties as the head of the athletic committee as was devoted to the serious charges of faculty unrest presented by the petition.[11]

The silence from the board and from President Kingsbury only exacerbated the growing dissent at the university. Merrill’s attempts to reconcile the two parties failed, and the situation continued to grow worse. Given the actions taken by Kingsbury and the board over the next two years, it is unlikely that the document was given much consideration. During 1914 and 1915 the accusations in the petition practically became a script for the events at the university, with Kingsbury and the board unwittingly acting out the charges made against them.

The 1914 Election

By 1914 Democratic prospects had improved to a startling degree. Woodrow Wilson became a popular leader, and the effects showed around the country. Democrats successfully continued to use Prohibition to drive a wedge into the Republican ranks. The erratic acts of Utah governor William Spry, who vetoed a bill favoring Prohibition brought before him, served to decrease the perception of Church sanction of the Republicans. Through stake conference addresses and signed articles in the Deseret News, Apostles Heber J. Grant, George Albert Smith, Anthony W. Ivins, and Francis M. Lyman all began to encourage action in favor of Prohibition.[12] Grant in particular threw his influence behind the Democrats, helping to equalize their standing in the eyes of Church members.[13] A new law put the election of US senators in the hands of the populace, and the Democrats nominated Henry D. Moyle, a respected Latter-day Saint, to run against Reed Smoot. It looked as if Smoot’s “federal bunch” was disintegrating, and the possibility of defeating the Apostle-senator became very real. Most importantly, the remnants of Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive Party allied themselves with the Democrats, creating a viable majority capable of toppling Republican dominance in the state.[14]

Amid this flurry of developments, Joseph F. Merrill was again nominated for the office of state senator, this time on a fusion ticket by both the Democrats and the Progressives. The Salt Lake Tribune, strongly pro-Democratic, acclaimed Merrill as the one of the two “strongest candidates on the ticket.”[15] The events of 1912 repeated themselves, only this time Merrill had a real chance of winning the election. For two months Merrill labored among the committees of the party to build the strongest ticket possible. Newspaper accounts frequently mention Merrill as a party insider who smoothed over quarrels and worked out compromises to bring a united front to bear on the Republicans.[16]

Merrill’s second attempt at political office came to a sudden end when he was ordered by the university’s Board of Regents in early September 1914 to withdraw from the race. Merrill withdrew but slammed the proverbial door on his way out and ignited a controversy debated in the Salt Lake papers for several days. There are no reports about whether Merrill met with the board, protested privately, or vacillated in his decision, but on 18 September Merrill tendered his resignation, sending a letter to Ray Van Cott, the Democratic chair, stating the reasons for his resignation. The letter made for excellent political theater and was reported in all four of the Salt Lake City newspapers. The intent of Merrill’s letter was to offer “a word of explanation and defense of my action.”[17]

Merrill wasted no time in pointing out those he saw as the culprits behind the order from the board. “I resign out of respect to the wishes of those that control the government of this state. If I understand aright, those controlling the party in power deem it improper for a public educator to be a candidate on a ticket opposing that party. To me this idea is new, and I believe it savors of a narrowness, illiberality, and political intolerance that should have no place in our public life.” Next, Merrill addressed the bitter partisanship reflected in the action: “In the past, religion has divided the people of this state more deeply and sharply than any other cause. But we have learned religious toleration, so that now we can differ religiously and yet live and work together in peace and amity. Educators may be active in religious affairs without active criticism or without bringing the schools into religious controversies. And so is it not strange that we cannot differ in our political views and still be friends?”[18]

Merrill told the Tribune that he felt the directive from the board was due to pressure exerted by the politicians in control of the Herald-Republican, a Salt Lake newspaper controlled by Republican interests. Merrill pointed to the influence of the Herald-Republican and pointedly asked why “an educator may not be given an unsought nomination to a public office without a threat from the official organ of the party in power that vengeance will be visited upon the institution to which he is connected.” He then redirected the charge laid against him of bringing partisan politics to the university, saying, “The objection to the nomination cannot spring from an honest conviction that the nomination would draw the institution [the university] into politics unless politicians of the party in power should make the nomination an excuse for introducing politics into the institution.” He pointed out that “in the past, prominent educators . . . have served with credit in our state legislatures and have also taken the stump for the party in power without anyone questioning, so far as I know, the propriety of their so doing.” He went so far as to point out that Woodrow Wilson, the current president of the country, was serving as the president of Princeton University when he made his entry into politics.[19]

Defending his own choice to accept the nomination, Merrill argued that “the nomination itself would not interfere in the least with the discharge of my regular duties” and promised that “if elected, then my work at the university would have to be arranged for during a short time.” In the closing lines of his letter, he remarked with some degree of sarcasm that “wise men say present political conditions in this state make it inexpedient for me to remain on the ticket,” but he promised to “cheerfully withdraw.” He gave in to the temptation to fire one final parting shot, closing with his conviction that he was “rendering the best service I can now give to the cause that seeks to drive from power the intolerant and domineering politicians who stand in the way of a genuine rule of the people.”[20]

The Herald-Republican, the most direct target of Merrill’s accusations, printed Merrill’s letter almost wholly without commentary, giving only a sparse account of the events leading to the resignation and of the party meetings held afterward to find a successor to take Merrill’s place on the ticket.[21] The brief report appeared on page 8 of the paper. When the Church-owned Deseret News contacted W. W. Ritter, the chair of the university’s board, about Merrill’s statement, Ritter replied only that he was “very surprised at the communication” but told the paper the board was “opposed, as most universities and colleges are, to the members of the faculty running for political office.”[22] When asked about rumors of a secret communication between Utah governor William Spry and the board requesting a move against Merrill, Ritter denied the accusation. When asked for comment, Governor Spry also denied any secret communication but immediately seized the opportunity to point out that when George Thomas, president of Utah Agricultural College, was asked to run for state office, he consulted with the board of his school and was denied permission to run.”[23]

There is a lack of compelling evidence to fully answer whether the Republican leaders chose to intervene with the Board of Regents against Merrill. No minutes exist from the board’s meeting in which the move was made, and the only contemporary reference is found in the journal of Anthon H. Lund, a member of the board and an influential First Counselor in the First Presidency. Lund records simply, “Jos. Merrill in running for senatorship has violated the discipline of the School. The opinion of several presidents of universities were read and the general opinion was that this would bring politics into schools.”[24]

Goodwins Weekly, another Salt Lake periodical, openly derided Merrill, saying that his withdrawal “amounts to little more than one of the tea-pot variety when the real facts are considered.” Siding entirely with the Board of Regents, Goodwins called Merrill’s accusation of behind-the-scenes political dealing “absurd on its face.” The article dismissed Merrill’s charges, saying, “Professor Merrill has always demonstrated his strict partisanship and the present occurrence is not the only one in which trouble has been caused by an attempt to inject politics into the University.”[25]

The Salt Lake Telegram and the Salt Lake Tribune, the city’s two Democratic-leaning papers, came to Merrill’s defense. The headline in the Telegram blared that Merrill “Quits Race on Order of Utah Bosses,” calling the resignation a “brilliant communication” in its denunciation of “the autocratic rule of Republican state officials.” The article even went so far as to accuse the university regents of bowing to “manipulators of the Republican machine.”[26] The Tribune warned that “because Professor Merrill did not bow to the cap which they had placed on a pole they set out to crush him. They say to him and to all who are within the sphere of their pernicious influence: ‘Obey us or we will ruin you.’”[27] The Tribune was less caustic in its accusations and brought more evidence to bear in building a case for dirty political dealings. The Tribune pointed out seven different educational officials, including a member of the Board of Regents and a university faculty member, who were currently serving in political positions. It then made the observation that “all of the educators who have served in the legislature in the past without jeopardizing their positions have been Republican, for the most part subservient to the dictation of the bosses who control the party. Professor Merrill is a Democrat and opposed to practically everything the bosses advocate.” The article also raised the point that “no objection whatever was made from any source to the candidacy of Professor Merrill two years ago for the state senate,” then laying the direct charge that the fact that “the bosses kept silent two years ago and made such an emphatic protest this year would probably be taken to indicate that two years ago they felt certain of winning, while this year they are very much afraid that Professor Merrill would be elected were he permitted to remain a candidate.”[28]

Was there a conspiracy against Merrill in the 1914 election? Governor Spry was correct in stating the precedent of George Thomas’s consulting with the board of the agricultural college before accepting a nomination. He did not point out that Merrill had attempted to start a similar conversation with the University of Utah’s board the year before, when the faculty petition spearheaded by Merrill was presented and summarily tabled by the board. Perhaps the most telling argument was the point made by the Tribune, which noted the lack of objections to Merrill’s candidacy in the 1912 election, when he held almost no chance of winning.

Merrill’s dramatic resignation was undoubtedly good political theater, but it also demonstrated his genuine feelings of being singled out because of his rising political stature. As a testament to the increasing fortunes of the Democratic-Progressive ticket, George H. Dern, the man nominated to take Merrill’s place, still managed to win an extremely close election.[29] While the decision to force Merrill’s resignation was not entirely without precedent, the timing was suspicious. When asked for comment on the board’s policy in the matter, President Kingsbury was evasive in his response, saying, “There has been no definite policy in the past, but I understand the members of the board think that it is inexpedient at this time for anybody to accept a nomination.”[30]

The Democratic trend in Utah politics continued over the next few years, with the fortunes of Republicans waning almost in direct proportion to the popularity of Woodrow Wilson on the national scene. Even the seemingly undefeatable Reed Smoot only narrowly defeated a challenge from Democrat Henry D. Moyle, winning by just three thousand votes.[31] A later biographer of Smoot remarked, “He didn’t win, he survived.”[32] The Republican majority in the lower house of the Utah State legislature was completely wiped out. Continuing to exploit Prohibition as a wedge to drive the Republican coalition apart, Democrats and Progressives made gains in the ensuing years.[33] The Republican machine imploded entirely in 1916, and a Democrat-Progressive coalition took over the state legislature and the governorship.[34] Merrill, however, was not to take part in these victories; instead, he was swept up in a maelstrom that engulfed the University of Utah in 1915.

The 1915 Controversy

The 1913 petition submitted by Merrill and the university faculty and the 1914 debacle surrounding Merrill’s candidacy were only symptoms of larger problems simmering under the surface at the university. A month before Merrill was nominated to run for state senate, a minor disturbance occurred during the June 1914 commencement exercises, when Milton H. Sevy, the president of the student body and class valedictorian, gave an inflammatory speech regarding the current state of politics in Utah. “The people must be converted,” Sevy declared, “that their political hope lies in the breaking down of ultra-conservatism and in the leadership of young, progressive, men.” Sevy said there were many young men ready to “place Utah on the progressive map” and said “the new leaders must fight against the inertia of the established prestige of present leaders.”[35] This was a bold move, given that the current leaders of the state, including Governor William Spry, sat on the stand in front of the student body while Sevy launched his verbal assault. Nevertheless, the young valedictorian continued fearlessly, even making charges of manipulation by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: “Unfortunately, there still remains some vestige of the old-time church antagonism. Some provincial ideas and narrow prejudices are still held by representatives of all factions. . . . We can not grow as we should under such a policy; we must have a broader and bigger outlook.”[36] As Sevy continued, it became clear that the speech was intended to inflame the university and state officials on the stand. At one point in the speech, Sevy even accused the governor of making the housing of livestock at the state fairgrounds a priority over housing female students at the university because of a rejected initiative to build more women’s housing.[37]

Governor Spry placidly listened to the speech then arose and gave a conciliatory address, never directly mentioning Sevy’s comments. Privately, the governor and members of the Board of Regents were furious over the speech. Anthon H. Lund, sitting on the stand next to Governor Spry, recorded in his journal, “The Oration by Student [Milton H.] Sevy was political clap-trap, with flings at Gov. Spry and the Legislature. The Governor whispered to me: ‘Is that what we get for all our sacrifices we have made for the education of our youth? I have a good notion to resent this talk.’”[38] Three days later, Governor Spry sent a letter to the Board of Regents, writing, “In attending the Commencement exercises of the University I was amazed at the utterances of the Class Valedictorian. While the impulse was strong to give public expression of my disapproval of the spirit of the address, . . . I refrained from mentioning the matter in my address, feeling that doing so might embarrass and tend to mar the proceedings of the day.” The governor took a dismissive attitude toward Sevy, attributing his involvement to “inexperience and irresponsibility.” The letter then took a darker turn. Spry warned that “the Faculty of the University of Utah in their eagerness to secure larger appropriations for the institution, are bearing fruit in a generation of graduates who . . . fail to recognize the extent of their obligations, sneer at what has been done for them at great cost and oft-times great sacrifice, and, with the approbation of their college professors, heap abuse on the state and her institutions.” He then warned ominously, “There is a growing feeling in the state that the burden [of taxation for educational purposes] is more than the people can carry, and I am fearly that this sentiment will crystallize in a general curtailment of educational appropriations.” [39] Whether this was a warning or a veiled threat is not entirely clear, but President Kingsbury and the board were jarred sufficiently by the letter to immediately launch an investigation into the matter.

Kingsbury, at the request of the board, called Milton Sevy in for a long conference only hours after the governor’s letter arrived. Sevy later testified that in the meeting, “The President proceeded to admonish me to be careful in saying anything that would offend any supporters of the University, that when various interests were supporting the University by taxation they were very sensitive about being criticized.” Kingsbury further grilled Sevy about the involvement of any faculty members in the writing of the speech. Sevy named three professors: William G. Roylance, the former editor of the school’s newspaper; Charles W. Snow, a member of the English Department and Sevy’s debate coach; and Byron Cummings, the respected dean of arts and sciences.[40] Revealing the political undertones to the whole affair, Sevy later reported that Kingsbury “said he was glad Dean Cummings had examined it, because he was a stand-pat Republican, and in had been charged that Democratic and Progressive Faculty members were responsible for the speech.”[41]

Kingsbury and the board took no immediate action on the matter, but widening divisions continued under the surface at the university. At times the conflict was painted as one between Republican interests and the growing influence of Democrats and Progressives in the state. Others chose to attribute the difficulties to the interference of the Church hierarchy in university matters. Of the fourteen regents, four were not members of the Church, eight were Latter-day Saints, and two were “cultural” Latter-day Saints, not active in the faith. The most prominent Church member on the board was Anthon H. Lund, First Counselor in the First Presidency. Kingsbury was raised as a Latter-day Saint but became irreligious as an adult. One critic of the board said it was “composed chiefly of politicians and capitalists.”[42]

The controversy surrounding Merrill’s run for state senate that fall not only highlighted the political divisions at the university but also demonstrated the difficulty in simplifying the controversy as another Latter-day Saint versus secular conflict. Merrill was an ardent Democrat and a devout member of the Church. But Merrill himself alluded to the history of religious conflicts in the state, though he optimistically believed that people could differ religiously and still work together toward a common good.[43] Unfortunately, the ugly charges of Church domination arose in the ensuing months, and Merrill, devoted to bridging the gap between the two communities, found himself caught it the middle of it.

The spark ignited by Sevy’s speech finally exploded in February 1915. On 26 February, President Kingsbury informed four professors, including Charles W. Snow, Sevy’s debate coach, that he was declining to recommend their reappointment for the following year. The men were given no reason for this action other than Kingsbury’s assurances that his actions were “for the good of the University.” He also denied them the opportunity of any kind of formal hearing regarding their termination.[44] The move caused an immediate outcry among the student body. The university Chronicle reported, “That these four men, who are among the most popular and progressive instructors in the University, should be discharged without any reason being given, has caused great indignation not only in the student body and in the Faculty, but among prominent businessmen of Salt Lake.”[45] The dismissed professors immediately took their case to the local press. Charles Snow tied the firing directly to Sevy’s commencement address, saying, “Fundamentally it is a fight for academic freedom. . . . The one thing we should fight most and fear most is repression of thought and repression of free speech. If a young man at commencement wants to urge a reform program on the state and nation, he should have perfect liberty. . . . Our university teachers should be running streams rather than stagnant pools.”[46]

All four of the fired professors were not members of the Church, lending credence to charges of Church interference in the school. The situation was exacerbated further on 1 March when Kingsbury announced the removal of George M. Marshall, a twenty-three-year veteran of the faculty who was not a Latter-day Saint, as the head of the English Department. Marshall’s health was the primary reason behind his removal, but the controversy was inflamed by the simultaneous announcement of Osborne J. P. Widtsoe as his replacement. Widtsoe was the principal of the Latter-day Saints’ High School and had no experience teaching on the collegiate level. His position as a Latter-day Saint bishop provided new ammunition to the school’s critics.[47] An anonymous rogue even printed and circulated a handbill using faux scriptural language to tell the story of “The End of the Reign of Prexy the Pious,” which Kingsbury called a “direct insult.”[48]

The troubled atmosphere surrounding the dismissals led to calls within the community to investigate Kingsbury’s handling of the university. On 3 March, twelve hundred students held a rally and presented a resolution asking the board to investigate Kingsbury’s acts.[49] A few days later, state senator George H. Dern, Merrill’s replacement in the senate run the prior fall, introduced a resolution in the legislature calling for the appointment of an investigative committee and labeling Kingsbury’s actions “a matter of grave concern to all the people of the state of Utah.”[50] The action was voted down within a few days, and Dern claimed that Kingsbury used his political connections to quash the inquiry.[51]

In the meantime, the university’s alumni association issued its own call for an investigation and elected a committee of its own to carry out the investigation.[52] On 10 March the university faculty met to appoint their own investigative committee. Merrill presided at the meeting and was asked by the faculty to serve on a committee of three that would be tasked to confer with the regents over the firing. When reporters asked Merrill to comment on the controversy, he refused, telling them only that he thought publicity would not benefit the university and that it would prove a hindrance to the speedy settlement of the issue.[53]

Given the circumstances, Merrill’s restraint is admirable. He could have crowed about the faculty’s 1913 attempt to head off the factors leading up to the current difficulty. Because he was still nursing wounds from the senate fight the previous year, this new controversy might have become another opportunity for him to prove his point about the divisive politics infecting the university. It is likely that his reticence came from his close ties to Kingsbury. The growing storm threatened to undo his years of hard work to build the university into a respectable institution. Merrill sincerely wanted the University of Utah to receive its due respect as a beacon of higher learning, but he also wanted it to be a place where believing Latter-day Saints like himself could mingle with the brightest minds inside and outside the faith. After decades of relative calm, the violent conflicts of his youth manifested themselves, and he once again found himself “between the devil and the deep blue sea.” He had earlier called for greater academic freedom, but he was also Kingsbury’s chief lieutenant, essentially the vice president of the university, and Kingsbury’s fall could bring all his dreams toppling down too.

Fuel to the Fire

The situation deteriorated quickly when the Board of Regents voted, eight to four, to reject the faculty call for an investigation. The board issued a long statement supporting Kingsbury and providing some insight into why the firings occurred. According to Kingsbury, the departing professors spoke “very disrespectfully” of the board and in a “deprecatory way about the University.” The board felt that an “irreparable breach” had developed between Kingsbury and the professors and chose to keep Kingsbury rather than the dissenting teachers. The statement also strongly denied any outside forces directing the events at the university: “Neither religion nor politics now has or ever had anything to do with any action of the president or of the board.”[54] The statement only added fuel to the fire. The university Chronicle correctly pointed out that the statement was written before the meeting of the board and was issued only a few minutes after the session adjourned, indicating that the board never took seriously the faculty’s request for an investigation. The Chronicle went on to say that the statement was “full of praise for President Kingsbury and his actions, and of condemnation for everyone who has criticized either the president or the board. It ignores entirely the protests of the faculty, the alumni association, and the students.”[55]

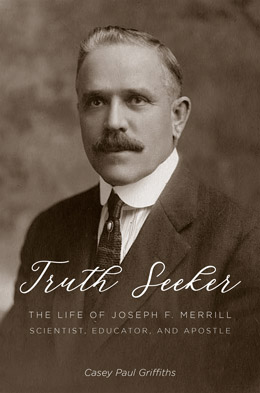

Joseph T. Kingsbury, Merrill's uncle, become embroiled in a controversy that cost the university some of its best teachers and derailed Merrill in his aim of becoming the president of the University of Utah. Courtesy of The Salt Lake Tribune.

Joseph T. Kingsbury, Merrill's uncle, become embroiled in a controversy that cost the university some of its best teachers and derailed Merrill in his aim of becoming the president of the University of Utah. Courtesy of The Salt Lake Tribune.

The evening after the board statement was issued, the Salt Lake Telegram published an extra edition, declaring the resignation of twelve professors, including five heads of departments and two deans. The move was apparently premeditated among the resigning faculty; several of their letters of resignation appeared in the Telegram.[56] The following day, two more professors resigned, bringing the total of departing faculty to fourteen, not including the four dismissed teachers. Faced with a full-scale mutiny, Kingsbury dug in his heels, issuing a statement that “The action of professors is no surprise to me. . . . The resignations of the men will have no material effect on the university.” He continued, “We will have no difficulty in replacing them with men just as able as those who will leave.”[57] Despite Kingsbury’s assurances, the situation was unraveling quickly. The same day, the student body held a mass meeting where all but thirty-four students voted to leave the university if the resignations went through. Another resignation was received from J. J. Thiel, a language professor, bringing the total number of faculty voluntarily leaving the school to fifteen.[58]

Merrill was not among the professors who quit but was deeply concerned over the situation. To this point, he had worked within official channels to try and head off the disaster. In a rare move of dissent, he privately approached Anthon H. Lund to speak about Kingsbury’s handling of the situation. The only part of the conversation recorded in Lund’s journal is that Merrill told him he thought Kingsbury “does [not] draw his faculty to him.” [59] The next day Lund spoke with Kingsbury personally, assuring the embattled president that the majority of the regents would back him. Later in the day, Apostle Francis M. Lyman and his son, Richard R. Lyman, approached Lund and suggested that the situation might be defused if Osborne Widtsoe simply refused the appointment. Lund felt that any kind of capitulation would be used for evidence of Church involvement. He recorded in his journal, “It would make the other side more aggressive. They would say, ‘The Mormons tried to put a Mormon bishop into the University, but when the people objected they backed out.’ We have gone too far in the matter. I can prove that the Church did not seek his [Widtsoe’s] appointment.”[60] Kingsbury told Lund that he was accepting the resignations and made no attempts to meet or negotiate with the departing faculty.[61]

Neither side was willing to compromise, but Merrill continued his attempts to repair the widening breach. With time running out, Merrill attempted to arrange a last-minute conference between university officials and resigning faculty, but both sides rejected his entreaties. When it was reported that he came on behalf of Kingsbury and the regents, Merrill issued a statement in the Telegram: “I was acting for no one except myself in attempting to arrange for a meeting of the professors leaving the faculty and the president. I wish to correct any impression that may have gone out that I was acting as the representative of the administration.” Merrill continued, “My idea was that perhaps a meeting of the professors, the president, and some of the board of regents would result in some understanding. I thought that this opportunity for a discussion of the differences might result in some good, but it appears that the breach was too wide. . . . The meeting should have been held before the resignations were accepted.”[62]

On 5 April the university’s alumni association voted to conduct its own investigation of the dismissals. The meeting revealed how deeply the actions of Kingsbury and the board had ruptured the community, in particular the Latter-day Saint supporters of the university. B. H. Roberts, a prominent member of the Church hierarchy, wanted the departing professors to reconsider to prevent the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) from intervening. Horace H. Cummings, the superintendent of Latter-day Saint schools, spoke out against the alumni association’s appointing a committee to investigate when the newly established faculty relations committee was perfectly able to handle any future disputes. Waldemar Van Cott, also a Latter-day Saint, expressed his dismay, saying that the alumni association was jumping into the fray before the Board of Regents could. Despite these protests, the alumni voted 197–134 to investigate. At the meeting, a committee of twenty-five was appointed to conduct the formal investigation, among them prominent Latter-day Saint leaders such as Apostle David O. McKay and Sylvester Q. Cannon, a future Presiding Bishop.[63] The divided stance among Church leaders indicates that the hierarchy probably played little part in the initial dismissals, but it signaled a cracking facade in the unity of Church leadership toward the problems at the university. The rift among Church leadership became more obvious a few days later when an editorial appeared in the Deseret News declaring the alumni association’s investigative committee a weapon of the resigned professors. B. H. Roberts fired off a letter of his own, accusing the editorial writer of being the same person who sent a letter to the Board of Regents urging them not to cooperate with the alumni committee. Writing of both the letter and the editorial, Roberts expressed his dismay: “I consider both performances, the first unworthy of the Board of Regents to adopt, and the second unworthy of the Deseret News to receive into its editorial columns.”[64]

By now the controversy at the school was national news. The newly formed AAUP sent notice to the university that it was sending its own investigator to Utah. The same night that the alumni association appointed their committee, Professor Arthur Q. Lovejoy of Johns Hopkins University, Merrill’s alma mater, arrived in Salt Lake City. “Scholars in the East,” Lovejoy told the local newspapers, wished “to know whether men having the self-respect of their profession at heart can come here to teach, should they be invited!”[65] Lovejoy stayed in Utah conducting his investigation for four days. Lovejoy’s arrival injected a hearty dose of notoriety into the controversy at the university. Such nationally known educational leaders as John Dewey of Columbia, Frank A. Fetter and Howard C. Warren of Princeton, James P. Lichtenberger of Pennsylvania, and Roscoe Pound of Harvard sat on the AAUP’s newly appointed Committee of Inquiry on the Conditions at the University of Utah. The prestige accompanying Lovejoy upon his arrival was enough to convince the Board of Regents to submit to the AAUP’s suggestions. The Board of Regents subsequently voted to provide no assistance to the alumni committee.[66]

A few days later the Board of Regents voted to begin filling the faculty vacancies, essentially ending any chance of reconciliation with the departing professors.[67] On 23 April Merrill and another professor, Frederick W. Reynolds, made one last-ditch attempt to reconcile the two warring parties. The regents almost relented. Anthon H. Lund recorded, “A couple of hours were spent in an informal talk about taking back the resigning professors. It was suggested we tell them to come back. Prof. Reynold and Dr. Merrill had spoke[n] to Mr. [William W.] Armstrong . . . in behalf of the departing professors, but we had no direct word from them. It was understood that they would not come back only on the permission that all should be welcomed back.” This last ray of hope was extinguished when Lund and several others argued that “we have 95 [faculty members] who have been true to the institution” and “that they should be considered.”[68] This action essentially ended the contest. Perhaps with a touch of irony, on the same day that Merrill and Reynolds’s attempts at reconciliation failed, Milton Sevy, the student whose remarks set off the entire firestorm, arrived back on campus after “several months having been frittered away on his father’s sheep ranch in Southern Utah.”[69]

The final tally of the resigning faculty was devastating. It included nine full professors, including the dean of arts and sciences, the dean of the law school, four assistant professors, three instructors, and one lecturer—a third of the entire faculty.[70] The departing faculty scattered to the wind, most of them finding gainful employment at other universities throughout the western states. That summer, Kingsbury embarked on a rapid tour of eastern states, recruiting as many new professors as he could to fill the positions of the resigned faculty. Conditions at the university were so depressed that the graduating class voted to hold no exercises. Some members even attempted to withdraw a class fund that had been set up as a memorial because they feared that “the establishment of such a fund might be construed as evidence that the members of the class approved of the administrative policy which has so nearly wrecked the University.”[71] For Merrill, it was his worst defeat at the university. From the time of his arrival two and half decades earlier, he had spoken of bridging the divides threatening the close-knit university community. Now it was all torn asunder, and many of his close colleagues left behind the dream they built together.

The AAUP’s official report was published in July 1915 and presented to the Board of Regents the following September. In ensuing months, the AAUP published an advertisement in the Nation, a coast-to-coast magazine, warning professors away from the University of Utah.[72] The report roundly criticized the university leadership, declaring, “Under the present administration of the university there has existed a tendency to repress legitimate utterances (on the part of both faculty and students) upon religious, political or economic questions, when such utterances were thought likely to arouse the disapproval of influential persons or organizations, and thus to affect unfavorably the amount of the university’s appropriations.” The report did concede that “the committee does not find evidence, however, that this policy has led to the dismissal of any professor.”[73] Merrill was one of several professors quoted in the report, telling the investigator he held no knowledge of a conspiracy among the faculty to remove Kingsbury from his position.[74]

The conflict at the university was perhaps inevitable, given Kingsbury’s dictatorial tendencies. The attempts led by Merrill in 1913 to press for more openness and dialogue between the administration and the faculty failed to impede the coming disaster. Merrill’s forced withdrawal from the 1914 state senate race and the crisis at the university the following year sadly demonstrate his naivete concerning the divisions of the warring parties he sought to placate. When he left the senate race, he asked, “Is it not strange that we cannot differ in our views and still be friends?”[75] The statement captures in large measure the optimism he felt toward the differing factions surrounding him. Up to this point, his whole life had been spent reconciling groups that were said to be irreconcilable. He found the common ground between faith and science, brokered compromises between the Latter-day Saint and secular factions at the university, and even found a reasonable compromise between church and state in the creation of the released-time seminary program. But his attempts to broker compromise between the administration and the resigning faculty had failed. It was his first major disappointment after sixteen years of success at the university. Little did Merrill know, it was only the first in a series of devastating tragedies.

Notes

[1] C. Austin Wahlquist, “The 1912 Presidential Election in Utah” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1962), 30.

[2] The 1912 election is one of the most fascinating in the history of American politics and has been written about extensively. The most detailed analysis of the election within Utah is found in Wahlquist, “1912 Presidential Election,” 1962. The best short analysis of Utah politics from this period is found in Jan Shipps, “Utah Comes of Age Politically: A Study of the State’s Politics in the Early Years of the Twentieth Century,” Utah Historical Quarterly 35, no. 2 (Spring 1967), 91–111.

[3] Shipps, “Utah Comes of Age,” 102.

[4] Wahlquist, “1912 Presidential Election,” 95.

[5] “Who’s Who in Utah Senate and House,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, 7 November 1912, 1; Allan Kent Powell, “Elections in the State of Utah,” in Utah History Encyclopedia, ed. Allan Kent Powell (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1994), 159.

[6] Ralph V. Chamberlin, The University of Utah: A History of Its First Hundred Years (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1960), 323.

[7] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 324.

[8] “Petition to the Board of Regents of the University of Utah,” 28 October 1913, box 1, folder 5, 2–3, James E. Talmage and Joseph T. Kingsbury Presidential Records, University Archives and Records Management, University of Utah.

[9] “Petition to the Board of Regents,” 3.

[10] “Petition to the Board of Regents,” 3.

[11] Minutes of the Executive Committee of the University of Utah, 1 November 1913, MSS B 20, box 5, folder 15, Ralph V. Chamberlin Papers, Utah State Historical Society.

[12] Shipps, “Utah Comes of Age,” 103.

[13] Shipps, “Utah Comes of Age,” 107.

[14] Shipps, “Utah Comes of Age,” 108.

[15] “Democrats and Progressives Name County Fusion Ticket,” Salt Lake Tribune, 19 July 1914, 1. The other candidate the paper declared to be the strongest on the ticket was Thomas Homer, the nominee for Salt Lake County Clerk.

[16] “Democrats Will Meet on June 11,” Salt Lake Tribune, 1 May 1914.

[17] “Merrill Raps Bosses Who Persuaded Regents,” Salt Lake Tribune, 18 September 1914.

[18] “Merrill Raps Bosses.”

[19] “Merrill Raps Bosses.”

[20] “Merrill Raps Bosses.”

[21] “Prof. J. F. Merrill Resigns Candidacy for State Senate,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, 18 September 1914, 8.

[22] “Merrill Tenders His Resignation,” Deseret News, 19 September 1914, 5.

[23] “Merrill Tenders His Resignation,” 5.

[24] Danish Apostle: The Diaries of Anthon H. Lund, 1890–1921, ed. John P. Hatch (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2006), 548.

[25] “Straight Talk,” Goodwins Weekly, 14 September 1914, 6.

[26] “Quits Race on Order of Utah Bosses,” Salt Lake Telegram, 17 September 1914.

[27] “Merrill’s Case,” Salt Lake Tribune, 20 September 1914.

[28] “Merrill Raps Bosses.” The educators mentioned in the article were E. W. Robinson, a member of the faculty of the Utah Agricultural College, who had served two terms as speaker of the Utah House of Representatives; Preston D. Richards, who served a term in the lower house of the state legislature while principal of a public school; Herschel Bullen, Jr., a member of the state senate, who was an administrator at Brigham Young College; John M. Mills, who served in the legislature while serving as superintendent of schools in Ogden and was a former faculty member at Latter-day Saints University; W. N. Williams, a member of the U’s Board of Regents and a member of the state senate at the time of the controversy; Byron Cummings, a U faculty member who also served on the Salt Lake City Board of Education; and R. H. Bradford, another member of the U’s faculty who was also on the Salt Lake School Board.

[29] “Dern Is Successor of Merrill on Democratic Ticket,” Salt Lake Telegram, 24 September 1914. “Vote in Salt Lake,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, 4 November 1914, 1.

[30] “Merrill Tenders His Resignation,” Deseret News, 17 September 1914.

[31] Gordon B. Hinckley, James Henry Moyle (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1951), 271.

[32] Milton R. Merrill, “Reed Smoot, Apostle in Politics” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1950), 159.

[33] Shipps, “Utah Comes of Age,” 109–10.

[34] Noble Warrum, ed., Utah Since Statehood: Historical and Biographical (Chicago: S. J. Clarke, 1919), 178.

[35] Quoted in “The American Association of University Professors Report of the Committee of Inquiry on Conditions at the University of Utah” (AAUP Report), July 1915, 60.

[36] AAUP Report, 61.

[37] AAUP Report, 61.

[38] Diaries of Anthon H. Lund, 542 (grammar and punctuation in the original).

[39] AAUP Report, 63.

[40] Joseph Horne Jeppson, “The Secularization of the University of Utah” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1974), 163.

[41] AAUP Report, 65.

[42] Jeppson, “Secularization,” 162.

[43] “Merrill Raps Bosses.”

[44] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 328.

[45] “Popular Instructors Are Dismissed from Faculty by President,” University of Utah Chronicle, 1 March 1915.

[46] C. W. Snow, “Says It’s New Utah and Freedom Against Old Utah and Bondage,” Salt Lake Herald, 27 February 1915.

[47] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 328–9.

[48] “Marshall Gets Another Post,” Deseret News, 2 March 1915, U of U 1915 Controversy Scrapbook, University of Utah Archives.

[49] “Students Hold Mass Meeting,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, 3 March 1915, U of U 1915 Controversy Scrapbook. The local newspapers quibbled over the size of the rally. While the Herald presented the number of students as twelve hundred, the Deseret News claimed that “only about four hundred” signed the petition. “Student Meeting Was Not Official,” Deseret News, 3 March 1915, U of U 1915 Controversy Scrapbook, University of Utah Archives.

[50] “Asks Senate to Probe U of U Fight,” Salt Lake Telegram, 4 March 1915, 9.

[51] “Probe Blocked by Kingsbury, Asserts Dern,” Salt Lake Tribune, 29 March 1915, 1.

[52] “University Alumni Ask Investigation,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, 6 March 1915, U of U 1915 Controversy Scrapbook.

[53] “Probe Is Sought by University Faculty,” Salt Lake Tribune, 10 March 1915, 14.

[54] “Regents Refuse to Make Investigation,” University of Utah Chronicle, 18 March 1915, 1–3.

[55] “Regents Refuse to Make Investigation,” 1–3.

[56] “Twelve Resign from ‘U of U,’” Salt Lake Telegram, 18 March 1915, 1.

[57] “14 U. of U. Professors Resign; Kingsbury Takes Revolt Coolly,” Salt Lake Tribune, 19 March 1915, 1.

[58] “All But 34 Students Vote to Quit,” Salt Lake Telegram, 19 March 1915, 1.

[59] Danish Apostle: The Diaries of Anthon H. Lund, 19 March 1915, 572.

[60] Danish Apostle: The Diaries of Anthon H. Lund, 20 March 1915, 572.

[61] Diaries of Anthon H. Lund, 20 March 1915, 572.

[62] “U of U Alumni Will Discuss Controversy,” Salt Lake Tribune, 23 March 1915, 2.

[63] Jeppson, “Secularization,” 175–6.

[64] Salt Lake Tribune, 18 April 1915.

[65] University of Utah Chronicle, 6 April 1915, 1.

[66] Jeppson, “Secularization,” 180.

[67] Jeppson, “Secularization,” 180.

[68] Diaries of Anthon H. Lund, 23 April 1915, 575–76.

[69] University of Utah Chronicle, 23 April 1915, 3.

[70] E. E. Ericksen, Memories and Reflections: The Autobiography of E. E. Ericksen, ed. Scott G. Kenney (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1987), 73.

[71] “Seniors Abandon Idea of Holding Class Exercises,” Utah Chronicle, 14 May 1915, 1.

[72] Jeppson, “Secularization,” 190.

[73] Jeppson, “Secularization,” 190.

[74] Jeppson, “Secularization,” 36.

[75] “Merrill Raps Bosses.”