“Infidel Factory”

Casey Paul Griffiths, “'Infidel Factory,'” in Truth Seeker: The Life of Joseph F. Merrill, Scientist, Educator, and Apostle (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 21‒40.

Joseph F. Merrill departed Richmond and the insular world of Cache Valley at the age of nineteen. It was his first step into the wider world and away from the close-knit community where he spent his adolescence. Salt Lake City in 1887 was the closest thing that the Utah Territory could boast as a cosmopolitan center. The city was then, as it is today, a place with a dual personality. Like ancient Rome, it was a center of government and culture. Like Rome, the city became the focus of the perennial conflict between the kingdom of Caesar and the kingdom of God.[1] As Merrill entered this new environment, two life-altering events occurred. First, he fell in love with the study of science and the world of academia. Second, he became acutely aware of the conflict between the faith of his childhood and the outside world. As he arrived in Salt Lake City, he left the comfortable center of Latter-day Saint culture and encountered the religion’s often-contentious line of contact with the outside world.

For decades, the headquarters of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints stood in the center of the city. The Salt Lake Temple, gradually rising above the city skyline, was entering the fourth decade of its construction. The temple, designed to be the city’s focal point, was located on a plot of land where, only a few days after the Saints arrived in 1847, Brigham Young had stabbed his cane into the ground and declared it to be the place where the temple of their God would be built.[2] After their arrival in the Salt Lake Valley, the Saints’ isolation had lasted only a decade before nonmember settlers (called Gentiles by the Latter-day Saint faithful) came in the form of an army sent by the American government to put down a “Mormon rebellion.” In the ensuing years, an army of prospectors invaded the commonwealth, swarming the mountains and hills to seek out mineral wealth. One of the most ominous signs of the Gentile presence was Fort Douglas, the army installation built in the 1860s on the eastward slope of the Wasatch Mountains, where its artillery was in easy range of the temple and Church headquarters in the valley below.[3] This center of conflict, where the world of Joseph F. Merrill’s youth clashed so strikingly with the world of his adulthood, would eventually become his permanent home.

The University of Deseret

No place in the Utah Territory better captured the overlapping worlds of the spiritual and the secular than the University of Deseret. Named after a word from the Book of Mormon meaning “honeybee,”[4] the fledgling institution was officially founded in 1850 but experienced several deaths and resurrections before Joseph Merrill arrived in the late 1880s. It finally grew into permanence under the direction of John R. Park, an Ohio physician who came to the territory in 1861 and became the first president of the university.[5] Despite struggling with every kind of difficulty imaginable over the years, the university began to gain respect as an institution of learning throughout the territory. Joseph Merrill acknowledged as much when he later reflected on his time at the school. “I came from Cache County to attend the University largely because a former student from my town in his exuberant praise spoke of the University as being ‘the best school in the world.’”[6] Merrill never mentioned the name of the university booster who inspired him to attend, but he was likely also influenced by the teacher his father hired, Miss Ida Ione Cook, who is listed in the university annals as one of its early teachers.[7]

When Merrill arrived, the university was still struggling to build its own home at Union Square, a site less than a mile west of Church headquarters.[8] The school’s condition was rapidly improving, but classes often took place in less than desirable circumstances. One history class was taught in a basement room with a dirt floor, where students sat on seats made of planks on end supports and the only light came through spaces between the boards over the windows.[9] The school was attended by about two hundred students, presided over by a small handful of faculty.

Part of the university’s troubles came from its perception as a Church institution rather than as a center of secular learning. Eli H. Murray, an appointed territorial governor who was not a member of the faith, continually vetoed appropriations for the school, arguing that it was a Latter-day Saint school where the tenets of the Church were taught. The Board of Regents before this time was composed almost exclusively of Latter-day Saints, and the faculty largely consisted of members of the Church, but the school offered no courses in religion. One university leader argued to the governor that the school was “non-sectarian in its character and conducted in such a manner as to avoid giving a bias in the pupils’ minds in favor of any particular form of religion.” The force of this argument, however, was undercut by the fact that it came from George Q. Cannon, the First Counselor in the Presidency of the Church.[10]

At the same time that the school was accused of serving as an appendage of the Church, the religious members of the community also viewed it with suspicion. In the same letter in which George Q. Cannon argued for the secular credentials of the school, he noted, “The fact that it has been non-sectarian has been, in the minds of some of our citizens, an objection to the institution.” Cannon continues, “The charge has been made that the tendency of its teaching has been to favor infidelity in religion and doubts respecting the existence of God. The University has had this prejudice to contend with, and on this account, many have felt some reluctance about permitting their children to become its pupils.”[11]

“Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea”

Joseph Merrill also noticed the tension inherent in the university’s place between the camps of the Latter-day Saints and the Gentiles. “I was at the University during 1887–89,” he later wrote. “This was a period of intense feeling between the Mormons and Gentiles. Most of the Church leaders were living on ‘the underground’ and were continually hunted by ‘Deputy Marshalls.’”[12] Only a few months after Joseph’s arrival at the university, his father, Marriner, was arrested for unlawful cohabitation. He was discharged after a hearing two days later, but conflict over plural marriage colored every interaction in the community.[13] Fear and apprehension about the future of the practice of plural marriage and the future of the Church hung over the territory. In only two years, increased federal pressure would cause Church leaders to issue the 1890 Manifesto, in essence ending the practice, though it lingered on in different forms for years afterward.

Joseph found himself at times caught between these two worlds. His father was such a staunch advocate of polygamy that he once ordered a man to enter into it or to be put out of the Church.[14] Even after the Manifesto was issued, Marriner declared that “the time will never come in this Church when polygamist children will not be born.”[15] Joseph himself never showed any leanings toward polygamy in his writings, public or private, but as the son of one of the most prominent polygamists in the territory he felt a personal stake in the conflict. The stakes could only have been raised when Marriner was called to the apostleship in the fall of 1889.[16] Still, Joseph attempted to remain aloof, though he felt pulled between the two worlds. Reflecting on this time, Joseph later wrote, “We at the University felt that we were between ‘the devil and the deep blue sea.’ The Gentiles regarded us as a Mormon institution. The Mormons (some of them) look upon our own school as an ‘infidel factory.’ Hence we did not enjoy the whole-hearted support of either institution.”[17]

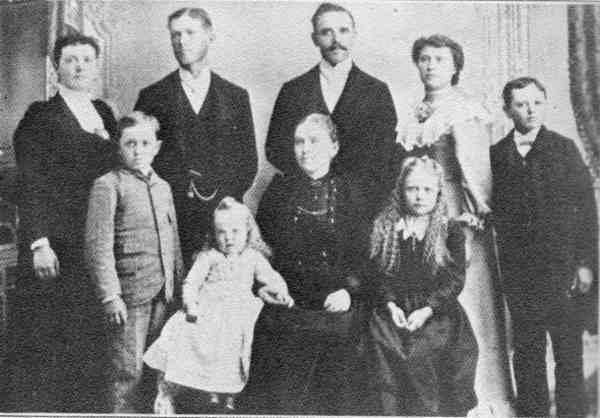

Joseph and his brothers and sisters in 1895. Joseph is standing directly behind his mother, Maria Merrill. Photo from Descendants of Marriner Wood Merrill, 458.

Joseph and his brothers and sisters in 1895. Joseph is standing directly behind his mother, Maria Merrill. Photo from Descendants of Marriner Wood Merrill, 458.

There was indeed reason for Joseph’s parents, especially Maria, to worry that he was entering an institution that might lead him down the road to apostasy. One of the surrogate fathers Joseph Merrill adopted during his studies at the University of Deseret was his uncle, Joseph T. Kingsbury, who was Maria’s older brother. Like Joseph, Kingsbury had been born in pioneer circumstances and reared in a Latter-day Saint environment. He too entered the University of Deseret under the direction of John R. Park and then traveled to the East, where he studied at Cornell University in New York and Wesleyan University in Illinois, returning home with a PhD and taking up the chair of chemistry and physics at the University of Deseret.[18] During his studies in the East, Kingsbury was deeply affected by his liberal arts training, in particular by lectures about God and man, and life and death, which were the first he had experienced outside of the context of Latter-day Saint theology. He came to seriously question the divinity of the Church.[19] When Kingsbury returned to Utah, his uncertainty turned into skepticism, irritation, and, at times, antagonism. He accused Church leaders of being anti-intellectual and not taking “the slightest interest in the establishment of an institution worthy of the name, university.” He complained, “Why is it that our people are afraid that much learning diffused throughout the territory would be a detriment rather than a benefit to the Church?”[20] Merrill never mentions Kingsbury in affiliation with religion, but he recognized the incompatibility of science and faith in the minds of some, noting that “many students of science begin to feel sooner or later that there is no personal God.”[21] Kingsbury represented one possible path that Merrill could follow as he began his education, and he became a key influence in Joseph’s life for the next four decades.

Life at the University

Despite the political-religious controversy surrounding the school, at its center the students found a welcoming and stimulating home. Joseph later reminisced about the time: “Glancing back I see an enrollment at the University of Deseret of about 200 young people, most of whom were out-of-town, and looked it, but all of whom were earnest and ambitious, knowing exactly why they were there.”[22] Joseph was fortunate enough to board at the Dean House, a well-known residence for students that housed other later luminaries in Utah education such as D. H. Christensen, the future superintendent of Salt Lake City schools, and Milton Bennion, whom the university’s school of education would one day be named after. Students lived in simple accommodations, and Joseph was lucky to have a roof over his head at a time when several of his fellow students lived in a tent pitched at the mouth of nearby City Creek Canyon.[23]

In later years, Joseph reveled in telling stories of the awkwardness and ignorance of himself and his fellow classmates. He recalled, “Amiable Dr. Park, the President, occasionally so far forgot himself as to lecture in his classes. I vividly recall that on the conclusion of one of his lectures he asked with animation, ‘Any questions, any questions, any questions?’ Harry Young, a student who listened attentively from the front seat, very calmly replied: ‘The truth is, Doctor, we don’t know enough to ask questions.’” Joseph continued, “Green, awkward and uncultured though most of us were (in those days I believe you would call it unsophisticated), still we loved our school.”[24]

While the faculty and students offered a congenial spirit to the young scholar, the facilities offered little else. Joseph remembered, “There were no laboratories, except the crudest beginnings of such in chemistry and mineralogy, subjects taught by Professor Kingsbury. A little field work was carried on in botany and geology under the direction of Professor Orson Howard. There was a small library in the charge of gracious Dr. Hardy. Aside from these, all instruction was given in the classrooms, the text book and recitation method being almost universal.”[25] However, the university students enjoyed a lively social life. At regular intervals the furnishings in the library were cleared out for dances. The faculty closely supervised the dances and even approved the list of attendees, lest the festivities get too out of hand. Some of the university’s more prestigious dances even saw the attendance of luminaries from the city and territory.[26]

Some social events were sponsored by Delta Phi, a popular fraternity. John Park organized Delta Phi as early as 1870, in an effort to “groom speakers and debaters.” [27] Fraternity members not only organized the dances but also sponsored debates, gave literary readings, and practiced parliamentary procedures, tackling some of the most heady topics of their day or days past. Debate topics included “Can a Man Sin Without Knowing It?” and “Was the Execution of Charles I of England Justifiable?”[28] The year before Joseph’s arrival, Delta Phi became so popular that a secessionist group was founded, resulting in charges of treason from both sides so inflammatory that Dr. Kingsbury was forced to intervene and settle the affair.[29] In addition to the intellectual pursuits of Delta Phi, the university offered a wide range of intramural activities, including football (students versus nonstudents), wrestling matches, ladies’ foot races, baseball (city students versus country students), boxing matches, and contests in swimming and rowing.[30]

Within a year after his arrival, Joseph earned a Normal (teaching) degree. At this point, the option was to leave school for a comfortable teaching career in any of the settlements of the territory, yet Joseph hungered for more. He secured a letter of recommendation from Dr. Park, who wrote, “During his attendance at the University, Mr. Merrill was exemplary in his deportment, assiduous in his studies, and in every way may bare an honorable and upright character. I take pleasure in introducing this gentleman and recommending him wherever such formality may seem necessary.”[31] Even before he left the university, Joseph was determined to follow in his uncle’s footsteps, setting his sights on an eastern university—the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. With his future in mind, the young scholar returned home to enact the perennial drama of the student asking for more funds.

Arriving in Richmond in December 1888, Joseph soon found himself in a wagon with his father, accompanying Marriner on one of his weekly trips to the Logan Temple. Sometime during the trip, Joseph mustered his courage and asked his father for the funds to travel to the East. He was surprised when his father quickly replied, “Yes, and I will keep you there as long as you let the girls alone and devote yourself to study.” Marriner then revealed an insecurity that may have been at the root of all his educational drive for his children: “I have been handicapped all my life by my lack of education.” He added jovially, “So I decided to give my children an education instead of leaving them anything to quarrel over after I am gone!”[32]

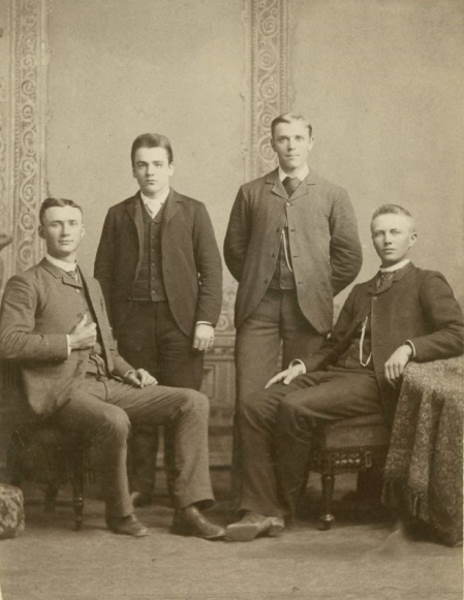

Sometime near his graduation from the University of Deseret in May 1889, Joseph and several of his schoolmates stopped in at the studio of C. R. Savage in Salt Lake City and posed for one of his earliest known photographs. He is pictured along with Edwin (Teddy) Bennion, Samuel A. Hendricks, and D. H. Christensen. Joseph, not yet twenty-one, stands with ramrod-straight posture in a reserved pose, his hands clasped behind his back and his tightly closed mouth giving a slight hint of a smile on his face. The picture shows no indication of a beard or even the beginnings of a mustache, which would become so characteristic of his features in later years. But there is a confidence in his eyes, a look of steely determination and a focused gaze indicating depth and intelligence.[33]

Schooling in the East

Soon after his graduation from the University of Deseret in 1889, Joseph departed for the East. He spent the better part of the next decade in different schools throughout the eastern United States, studying at the University of Michigan, Cornell University, the University of Chicago, and Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where he became one of the first Utahns to earn a doctorate. He carried out his undergraduate work in chemistry, most likely spurred by Joseph Kingsbury, who no doubt was eyeing his young nephew as a possible faculty member for the growing University of Deseret back in Utah. Of this crucial period in his life, Merrill’s time at the University of Michigan is most difficult to piece together. Joseph remained at Ann Arbor until 1893, and while the documentation of his life during this period is fragmentary, there is evidence of two crucial events from this time that impacted the remainder of his life.

A group portrait of University of Utah students, 1889. Left to right: Edward Bennion, Samuel A. Hendricks, Joseph F. Merrill, and D.H. Christensen. Courtesy of Church History Library.

A group portrait of University of Utah students, 1889. Left to right: Edward Bennion, Samuel A. Hendricks, Joseph F. Merrill, and D.H. Christensen. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The first event is found in his father’s record of correspondence. Joseph’s departure from Utah in 1889 occurred when the pressure applied by the federal government to end polygamy was reaching its most extreme levels. Four decades of conflict over polygamy had drained the Church of financial resources and left it teetering on the brink of bankruptcy. While Joseph was in Michigan, Wilford Woodruff, the President of the Church, presented the 1890 Manifesto, publicly ending the practice of plural marriage in the Church. The move was controversial on all sides, and Marriner noted that the announcement was carried by a “weak vote; but seemingly unanimous” in the Church general conference where it was announced.[34] The announcement meant the gradual end of polygamy in the mainstream Church, but it did not entirely mitigate the amount of persecution that the Latter-day Saints faced outside of their home in the West.

Despite Marriner’s enthusiasm for education, there are indications of his worries over the spiritual well-being of his son. Joseph was the first of his children to travel to the East for schooling, and Marriner’s admonition to “let the girls alone, and devote your time to study” probably related more to the fear of his son taking a nonmember wife than to any fear over a lack of focus in academics. Joseph was not the first young Latter-day Saint to attend school in the East, and Marriner likely had the example of Joseph Kingsbury in mind when he worried over his son’s schooling. With the notion of strength in numbers, when Joseph left for his second year at Ann Arbor, his half sister Libbie, the daughter of Marriner’s third wife, traveled back with him as a fellow student.[35]

Only a few months after Joseph’s departure, Marriner wrote to George Q. Cannon, a counselor in the First Presidency, requesting the appointment of a person in Ann Arbor to preside over the students. Less than a week later, he met with President Woodruff face-to-face to make the same request. No movement was taken at the time, but within a few months Joseph was called to his first position of ecclesiastical leadership, as the branch president over his fellow students from Utah.[36] Marriner’s worries about his children may have inadvertently led to his son’s first position of Church leadership. Joseph took the lead in the small branch that numbered around sixty students.[37] Joseph’s leadership over the Latter-day Saint students in Ann Arbor does not appear to have entirely alleviated his father’s fears over his son’s spiritual well-being. In one of the only letters remaining from this period, Marriner wrote to Joseph, “Do not forget your prayers and attend to your meetings even if only two or three attend, I do not want you to lose faith in the Gospel. Better not have an education than to do that, like some of our young men have done. This is my caution.”[38] Joseph’s side of the conversation is missing, but he seems to have felt some apprehension about his role as a Church leader at so young an age. In another letter from the time, Marriner admonished his son, “You say that you are not ordained to preach, but you are, and have authority to preach, but you have not been set apart and sent out to preach. That is the difference.”[39]

The second important event that took place during Joseph’s time in Michigan came in the development of a lifelong friendship with Richard R. Lyman. The bond between Merrill and Lyman came easily: both were the children of Apostles, both grew up in similar circumstances, and both showed a keen interest in science. Lyman was the son of Francis M. Lyman, an Apostle since 1880, and the grandson of notorious Apostle and apostate Amasa M. Lyman.[40] Alice Louise Reynolds, another Latter-day Saint student in Michigan with Merrill and Lyman, called the two “lifelong friends” and noted the parallel nature of their lives as both men eventually returned to Utah and later became close associates as they followed the apostolic paths of their fathers.[41] For his part, Lyman was impressed with the tenacity that Merrill brought to his studies at Ann Arbor, later writing of his friend, “Outstanding in his character is his persistence. When he attacks a problem no road is too long, no combination of circumstances too difficult.”[42] He also provided one of the only descriptions of Merrill’s work at the university, saying, “Joseph F. Merrill was associated with great investigators who were building upon the discoveries of Pasteur, the man who in 1880 made to human welfare perhaps the greatest of scientific contributions. Because of the accuracy and thoroughness of his work, Joseph F. Merrill was one of the students from the department of chemistry to aid in this experimental research.”[43]

Merrill also made an impression on other students and faculty during his time in Michigan. Isaac Demon, the head of the English Department, took Alice Louise Reynolds aside one day to tell her, “Miss Reynolds, your Mr. Merrill ranks high in scholarship; he is a sound student, and a capable man.” Reynolds herself was deeply impressed by Merrill as he served as her branch president, noting that the small cohort of Latter-day Saint students “came to know the depth of his spiritual life.”[44] While details are sparse concerning Merrill’s time at Ann Arbor, his experiences there undoubtedly drove him further down the path toward his dual role as a person with one foot in the realm of empirical science and the other in the world of religious faith. He had rubbed shoulders with some of the finest minds in the nation, and he had worked closely with the students from the world of his upbringing as their spiritual leader.

Falling in Love

When he returned to Utah in 1893 with a bachelor’s degree in hand, Joseph F. Merrill immediately took up a position at his old school, newly given the more secular title of the University of Utah.[45] He was appointed as an assistant professor of chemistry, continuing his role as a protégé of Joseph Kingsbury. During the summers he traveled to the East to further his studies at Cornell University in New York.[46] He continued to work and lay plans for a doctorate, setting his sights firmly on Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. However, the most important development in Merrill’s life during this period came not in the science of chemistry but in the even more peculiar science of romance.

Annie Laura Hyde came from a background both similar and dissimilar to Joseph F. Merrill’s.[47] She was a grandchild of two Apostles, John Taylor and Orson Hyde. Her father, Alonzo Hyde, was a wealthy and prosperous businessman, a manager of the Bullion Beck Mine. Yet while Joseph grew up on a rural farm in Cache Valley, Laura grew up in the urban center of the territory. The home of her youth was a large residence built across the street from the Salt Lake Temple. The house was so large that in later years it served as the first home of the Primary Children’s Hospital.[48] Lively and vivacious, Laura, as she insisted on being called to avoid confusion with her mother who shared the same name,[49] was described by a contemporary as “one of the elite girls of the town.”[50] George Albert Smith, the future President of the Church, was a childhood friend of Laura’s and described her, saying, “She was beautiful and had hair the color of spun gold.”[51]

Like Joseph, Laura Hyde lived in a world where the controversies surrounding plural marriage constantly swirled around her. Her father was not as prominent in the practice as Marriner Merrill was, and most of her life she grew up in a monogamous home. Her father was arrested for cohabitation in 1886, and Laura was asked to testify on his behalf. According to records available at the time, Laura testified that she knew nothing about her father’s involvement in plural marriage.[52] However, Laura’s father had taken a plural wife three years earlier in 1883.[53] Joseph later said that Laura’s father had been asked by George Q. Cannon, the First Counselor in the First Presidency, to take a plural wife to prove his loyalty.[54] Whether Laura deliberately perjured herself to protect her father or genuinely did not know is impossible to say. The controversy surrounding the practice, combined with the stringent federal enforcement of antipolygamy statutes, led many Latter-day Saint men to enter the practice in secret, without telling their families. In other cases, families often misled federal officials to protect their loved ones. At any rate, both Laura and Joseph, young, modern Latter-day Saints, became familiar with the practice of plural marriage through their fathers, and both knew the toll it exacted on their families.

Laura attended the Salt Lake Academy, a Church-owned school located in the heart of the city. She enrolled at the University of Deseret around the same time as Joseph. The exact circumstances of their first meeting are unknown, but Joseph mentioned in a letter to Laura that it was at one of the university’s well-known dances. Looking back on their first meeting, Joseph wrote, “I never think of dancing without having you in mind. You know it was at a dance that I made my speaking acquaintance with you and was mean enough to deliberately place you in such a position that you couldn’t well avoid asking me to call.”[55]

By the summer of 1895, their romance was in full bloom. Joseph was preparing to travel east again, this time in pursuit of a doctorate at Johns Hopkins University, and he wanted to secure the object of his affections by becoming engaged before he departed. On 13 June 1895, Joseph proposed to Laura in the library of her home.[56] She accepted, and Merrill was then determined to ask her father for his permission in person, but he lost his nerve when he met with Laura’s father face-to-face. A few days later, upon arriving in Richmond for the summer, Joseph followed the traditional practice of composing a letter to ask for Laura’s hand in marriage, writing, “I called at your house frequently especially during the last few weeks, and I had a purpose in doing so, which I recently declared to your daughter Laura. It was no less than the bold one of trying to capture her heart with a view of asking for her hand. But before going further I would like your permission to do so, and your consent to have her hand, provided I can get her to give it.”[57] Joseph wrote a letter to Laura the same day, hoping to increase his chances by instructing her to “see that [her father] is in good humor when he gets the letter,” and confessing his own anxiety, writing, “I shall know real peace only when I get a favorable answer from him.”[58]

Unfortunately, the reply was not favorable. Laura’s father wrote back a few days later, “We have talked with our daughter Laura on the subject of your letter and learn from her that it is your intention to spend the next two years in the east in study. In view of this fact both her mother and myself consider it the wiser course on the part of you both that no engagement should be entered into between you until after your return from your studies.” He did offer some salve to the young suitor’s heart, continuing, “From our limited acquaintance with you and from what we know of your reputation I will frankly admit that I know of no reason why we should object to your attentions to our daughter.” Hyde offered his permission for Joseph to continue writing to his daughter and even consented to a marriage after the young student’s return, but he also offered the practical advice that “should either of you in the meantime change in your feelings we do not think you should be bound by any promise or covenant.”[59] For his part, Joseph accepted the rejection stoically, writing back, “I told your daughter I should like to see her hand go where her heart went. And if at any time she found someone who she thought more of than she did of me that I wanted her to tell me and that I should then consider all at end between us.” He continued, “It is decidedly against any desire of mine to bind her in the least until I am ready to offer her my name.”[60]

The engagement ended before it really began. Joseph continued his preparations to travel to Baltimore, with no more forceful advocate of his going than Laura. Joseph showed his lovesickness over their separation and his anxiety over her father’s tacit rejection of their engagement. His letters during this time often lapsed into sentimental, semipoetical phrases. “I must confess that favors from you seem like delicious draughts from the cup of bliss,” he wrote. He reflected back on the brief time they spent together that summer, “To think that I would ask you to come here and then wear you out for want of sleep,” and planned future meetings, imagining the poetry he would compose after future rendezvous. “How I would enjoy a drive with you tonight . . . while the breeze among the trees seems to be whispering love to the moon beams as they quietly pass with their soothing messages to the beating hearts beneath.”[61]

While the young man showed some signs of vacillating on the eve of his departure, Laura was the partner in the relationship steeling him for the long separation. “I should not think you would look forward to going east with dread,” she wrote. “It should be a great pleasure in anticipation for you.” It is clear that Laura already saw their lives as invariably intertwined, and she knew that an education in the East was a gateway to influence at the university. “I want you to be prominent and to be the most popular professor in the University. I have an unfounded ambition for you, and do not want to hinder you in any way.” Her letters indicate that she already thought of herself as his spouse, even if their formal commitment was somewhat held up by her father’s objections. She continued, “If I cannot be a help to you, then I am not the woman whom you should marry, for a man’s wife should be the one whom he can trust above everyone else, whom he can go to for sympathy and encouragement, and who is his nearest counselor and advisor.”[62]

Laura’s words came at a fortunate time. Joseph was beginning to feel pressure from his family about the direction of his life. His father remained a firm advocate of his choice to forestall marriage in order to study in Baltimore, but other family members expressed dismay over his choices. Now twenty-seven years old, without a wife, family, or a firmly set profession, the young scholar was somewhat of an aberration in a culture fixated on family and faith. Doubts poured in from other family members on more conventional paths. Joseph wrote to Laura about a letter he had received “from Heber, my German missionary brother, in which Heber said he didn’t know what to think about me going off to college again. He thought I better turn my thoughts to a sweetheart and get married, or if I must leave Utah, he was convinced the best possible way for me to spend my time was in the missionary field.”[63]

Joseph may have been denied the formal recognition of his engagement to Laura, but he was determined not to leave the state without first placing a ring on her finger. Despite her father’s intervention, rumors of their engagement swirled in the circles of Laura’s friends and family. In response, Joseph was defiant. “I smiled when I read what you had to say about what people there are saying of us. Would your father frown if he were to hear it? Would he call me a base liar? There is no contradiction; . . . your third finger can wear a ring from me.”[64] With his departure date to Baltimore drawing near, he again waxed romantic, urging her to save her kisses and caresses for their final visit, “since I shall then have to go away for a long time, and can then caress you only in fancy and taste the sweetness of your lips as I now taste the pleasures of your constant companionship.”[65]

So it was that in late September 1895 Joseph boarded a train bound for the East, traveling farther from home than he had ever traveled before. No descriptive accounts exist of the scene staged by the young couple on the railway platform, but it is easy to imagine the young, uncertain scholar hesitantly boarding the train, compelled by the urgings of his ambitious but affectionate fiancée. His destination was far away from the mountain kingdom of his youth in more than just a geographical sense. During his previous sojourn in Michigan, there had been a small branch of Saints, a sister accompanying him, and a charge to oversee the spiritual welfare of the group—all tying him to the culture and upbringing of his family’s faith. In Baltimore there was no Latter-day Saint community, no branch, and no connection to the kingdom, other than letters. Almost completely severed from the world of his nativity, the strongest tie that Joseph F. Merrill would hold over the next two and a half years would be from his correspondence with the young lady now tearfully waving goodbye as his train sped east.

Notes

[1] Thomas G. Alexander and James B. Allen, Mormons and Gentiles: A History of Salt Lake City (Boulder, CO: Pruett, 1984), 93.

[2] Matthias F. Cowley, Wilford Woodruff: History of His Life and Labors (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1964), 316–17.

[3] E. B. Long, The Saints and the Union: Utah Territory During the Civil War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981), 117.

[4] Ether 2:3.

[5] Ralph V. Chamberlin, The University of Utah: A History of Its First Hundred Years (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1960), 63–64.

[6] Joseph F. Merrill, “Remarks at U of U Alumni Commencement Banquet, Union Building,” 4 June 1946, 3–4, Joseph F. Merrill Papers, Marriott Library Special Collections, University of Utah.

[7] See Jill Mulvay, “The Two Miss Cooks: Pioneer Professionals for Utah Schools,” Utah Historical Quarterly 43, no. 4 (Fall 1975); see also Chamberlin, University of Utah, 69, 96.

[8] Alexander and Allen, Mormons and Gentiles 114; Chamberlin, University of Utah, 122. The location of the University of Deseret when Joseph F. Merrill first began attending roughly corresponds to the location of West High School in Salt Lake City: 241 North 300 West.

[9] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 126.

[10] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 125.

[11] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 125.

[12] Joseph F. Merrill, “The Lord Overrules,” Improvement Era, July 1934, 413 (punctuation in original).

[13] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 15 January 1889, box 1, folder 1, Joseph F. Merrill Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University. See also Marriner Merrill journal in Merrill, Marriner Wood Merrill, 104.

[14] Richard S. Van Wagoner, Mormon Polygamy: A History (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1989), 98.

[15] B. Carmon Hardy, ed. Doing the Works of Abraham: Mormon Polygamy, Its Origin, Practice, and Demise (Norman, OK: Arthur H. Clark, 2007), 373.

[16] Marriner W. Merrill Journal, 7 October 1889, in Marriner, Marriner Wood Merrill, 108.

[17] Merrill, “Lord Overrules,” 413.

[18] Orson F. Whitney, History of Utah, 4 vols. (Salt Lake City: George Q. Cannon and Sons, 1904), 4:356.

[19] Lyndon B. Cook, Joseph C. Kingsbury: A Biography (Provo, UT: Grandin Book, 1985), 202.

[20] Cook, Joseph C. Kingsbury, 223.

[21] Merrill, “Boyhood Experiences,” 146.

[22] Merrill, “Remarks,” 1.

[23] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 139.

[24] Merrill, “Remarks,” 3.

[25] Merrill, “Remarks,” 3.

[26] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 139.

[27] William G. Hartley, Delta Phi Kappa Fraternity, A History, 1869–1978 (Salt Lake City: Delta Phi Kappa Holding Corp., 1990), 2.

[28] Hartley, Delta Phi Kappa, 18.

[29] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 140.

[30] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 139.

[31] John R. Park to Joseph F. Merrill, 23 September 1889, MSS 22972, Joseph F. Merrill Collection, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

[32] Merrill, Marriner Wood Merrill, 348. See also Richard R. Lyman, “Dr. Joseph F. Merrill of the Council of the Twelve,” Improvement Era, November 1931, 10.

[33] Photograph, PH 4199, Church History Library.

[34] Marriner W. Merrill Journal, 6 October 1890, in Merrill, Marriner Wood Merrill, 128. See also Sarah Barringer Gordon, The Mormon Question: Polygamy and Constitutional Conflict in Nineteenth Century America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 220.

[35] Marriner W. Merrill Journal, 29 September 1890, in Merrill, Marriner Wood Merrill, 127. Dozens of young Latter-day Saints attended school at the University of Michigan during this time, including Martha Hughes Cannon, James H. Moyle, William Henry King, Benjamin Cluff Jr., Alice Louise Reynolds, and Richard R. Lyman. See Thomas W. Simpson, American Universities and the Birth of Modern Mormonism, 1867–1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 137–47.

[36] Gordon B. Hinckley, “Church Mourning the Passing of Elder Joseph F. Merrill,” Improvement Era, March 1952, 146.

[37] The biographer of Alice Louise Reynolds, one of Joseph Merrill’s fellow students, places the number of students in the Latter-day Saint group at the University of Michigan at sixty-four. Reynolds’s time in Ann Arbor overlapped only slightly with Merrill’s. See Amy Brown Lyman, A Lighter of Lamps: The Life Story of Alice Louise Reynolds (Provo, UT: Alice Louise Reynolds Club, 1947), 23.

[38] Marriner W. Merrill to Joseph F. Merrill, 1 July 1892, box 14d, folder 7, Joseph F. Merrill Papers, Brigham Young University (spelling and punctuation in original).

[39] Marriner W. Merrill to Joseph F. Merrill, 28 February 1893, box 14d, folder 7, Merrill Papers, BYU (emphasis in original).

[40] See Richard R. Lyman, “President Francis Marion Lyman,” Young Woman’s Journal 28:3–6; and Edward Leo Lyman, Amasa Mason Lyman: Mormon Apostle and Apostate (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2009).

[41] Alice Louise Reynolds, “Dr. Joseph F. Merrill,” Relief Society Magazine 18, November 1931, 604.

[42] Richard R. Lyman, “Dr. Joseph F. Merrill,” 10.

[43] Richard R. Lyman, “Dr. Joseph F. Merrill,” 9–10.

[44] Reynolds, “Dr. Joseph F. Merrill,” 604.

[45] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 173.

[46] Bryant S. Hinckley, “Greatness in Men: Joseph F. Merrill,” Improvement Era, December 1932, 77.

[47] Biographical information on Annie Laura Hyde is condensed from Marian Skeen Merrill, Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill and Annie Laura Hyde Merrill (Salt Lake City: printed by the author, 1979), 6–12.

[48] “History,” Primary Children’s Hospital, Intermountain Healthcare, https://

[49] Annie Laura Hyde to Joseph F. Merrill, 19 February 1896, box 14b, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[50] Marian Merrill, Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill and Annie Laura Hyde Merrill, 6.

[51] Marian Merrill, Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill and Annie Laura Hyde Merrill, 6.

[52] “Alonzo E. Hyde Arrested,” Deseret News, 14 July 1886, 4.

[53] Myrtle Stevens Hyde, Orson Hyde: The Olive Branch of Israel (Salt Lake City: Agreka Books, 2000), 496. Alonzo E. Hyde was married to a second wife, Ellen Amelia Wilcox, on 9 March 1883. According to the Deseret News article that detailed the arrest of Alonzo Hyde, Laura testified that “she did not know and never had heard of Ellen Wilcox.”

[54] Joseph F. Merrill to J. W. Musser, 5 December 1951, box 20, folder 2, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[55] Joseph F. Merrill to Annie Laura Hyde, 27 November 1895, box 14a, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[56] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 13 June 1924, box 1, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[57] Joseph F. Merrill to Alonzo E. Hyde, 19 June 1895, box 14a, folder 3, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[58] Joseph F. Merrill to Annie Laura Hyde, 19 June 1895, box 14a, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[59] Alonzo E. Hyde to Joseph F. Merrill, 23 June 1895, box 14a, folder 3, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[60] Joseph F. Merrill to Alonzo E. Hyde, 25 June 1895, box 14a, folder 3, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[61] Joseph F. Merrill to Annie Laura Hyde, 4 August 1895, box 14a, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[62] Annie Laura Hyde to Joseph F. Merrill, 29 August 1895, box 14a, folder 9, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[63] Merrill to Annie Laura Hyde, 24 August 1895, box 14a, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[64] Merrill to Annie Laura Hyde, 10 August 1895, box 14a, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[65] Merrill to Annie Laura Hyde, 10 August 1895.