“Have I Not Deserved Better Things?”

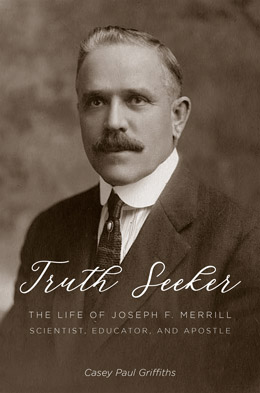

Casey Paul Griffiths, “'Have I Not Deserved Better Things?,'” in Truth Seeker: The Life of Joseph F. Merrill, Scientist, Educator, and Apostle (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 131‒58.

By the fall of 1915, the University of Utah, by no small miracle, was operating near full capacity again. After an exhausting summer of activity, Kingsbury managed to replace all the losses on the faculty. Perhaps just as miraculous, Merrill had weathered the maelstrom of the preceding spring without serious injury to his reputation or his status at the university. All his efforts to reconcile the administration with the faculty in revolt had failed, but he remained intact. It is clear from his efforts in 1913 and his entreaties during the crisis that he favored the position of the aggrieved faculty members, but overall his loyalties lay with the university. If there was a rift between Merrill and Kingsbury over Merrill’s entreaty to Anthon Lund, there is no existing evidence. Merrill remained in place as the university’s second-in-command and the heir apparent, should Kingsbury ever depart. For the moment, the storm had blown over, and calm was returning to the university, along with the majority of the student body, despite the threats of mass resignation among the pupils during the midst of the controversy.

In January 1916 rumors began to emerge among the Board of Regents of a movement to remove Kingsbury. After several board members spoke privately to him, he voluntarily submitted his resignation. Immediately after Kingsbury’s resignation, Simon Bamberger, a member of the board who was not a member of the Church, moved to appoint a committee to search for a new president. In response, Waldemar Van Cott, one of the board’s Latter-day Saint members, moved immediately to appoint John A. Widtsoe, president of the Utah Agricultural College, as the new president of the University of Utah. Four of the regents immediately protested. Widtsoe was a known and respected scholar in the Utah educational community, but he was also a devout member of the Church, and his brother, Osborne, was at the heart of the recent controversy. The board split along ecclesiastical lines, with regents Bamberger, Armstrong, and Whitmore, none of whom were Latter-day Saints, voting against the measure. N. T. Porter, a Latter-day Saint, also joined them.[1] Nevertheless, the protesting board members were outvoted six to four, and Widtsoe was appointed. Regents Armstrong and Bamberger later issued a formal statement protesting the vote. They both explained that they did not question Widtsoe’s qualifications for the position; instead, they questioned the machinations of the other board members in his appointment: “Dr. Widtsoe was decided upon, the matter settled, the position offered to him and accepted by him without any consultation with us.”[2] It was clear that the majority of the board came to the meeting already planning to choose Widtsoe. A few weeks later, the alumni association adopted a formal resolution condemning the action, noting, “The contention in the resolution was not against the removal of Dr. Kingsbury but the method employed by the board in effecting his removal.”[3] The same day, regent Whitmore, one of the dissenters, announced his resignation from the board over the action of the majority members.[4]

The action ruled out any chance of Merrill becoming president of the University of Utah, at least in the short term. Merrill immediately demonstrated his ambition to serve as a university president by rallying all his friends and allies in a bid to fill Widtsoe’s position at the state agricultural college. After Widtsoe was named the new president of the University of Utah, events moved quickly, and Merrill became a leading candidate for the presidency of the Utah Agricultural College. At least four other candidates for the office were mentioned: Franklin S. Harris, Franklin West, George Thomas, and Elmer Peterson, all faculty members of the agricultural college. The strongest support existed for Peterson, the director of the extension division at the college, but a significant faction also supported Thomas, head of the college’s school of commerce and the Logan School Board.[5]

Letters endorsing Merrill’s leadership began to arrive at the homes of the individuals involved in choosing the college’s next president. Letters praising his administrative acumen came from the superintendents of five different school districts within the state and from several high school principals.[6] Several educational officials in Ogden wrote, “It may be safely said that Dr. Merrill has had more training in scholarship than any other man in the state of Utah. He is a very strong executive, has a forceful personality and is a clear and lucid public speaker. He knows where he is going, and is not afraid to take stand and hold it.”[7]

One well-meaning friend, perhaps pushing the agricultural emphasis of the college too far, wrote, “Dr. Merrill live[s] upon what is practically a farm in the suburbs of Salt Lake City, in order that his children may be brought up in the environment preferred by him. . . . With his own hands, in fact, he has performed all the labor that is to be one upon the farm; this experience gives him a qualification which few eminent scholars have for such a position in a college of agriculture.” As the letter continued, it emphasized Merrill’s political work: “All who have ever been associated with his committee work . . . will testify of the extraordinary mind and of his power to grasp great problems. No one has seen him before a committee in the State Legislature who does not know his strength.”[8]

Merrill was more direct about his strengths and weaknesses in writing to his backers for the position: “I am greatly pleased to learn that most of the leading educators of the state—members of the state board of education, school superintendents, and high school principals—strongly endorse me for the AC presidency. . . . It is said I am a mining man—not an agriculturist. I have never studied a subject not now taught in the College, at least in its elementary forms. All my life, except when away at school, I have been, and still am, a practical farmer. It is said the majority of Logan people want a local man. The college is a state, not a local institution. The great majority of the educators of the state prefer me to the local men.” Merrill emphasized his background in Cache Valley and his family ties to the college, playing up every advantage he possessed.[9]

Underneath the surface correspondence, there is evidence of machinations for the college presidency based on Merrill’s affiliation with the Democratic Party. One of Merrill’s brothers living in Cache Valley, James, informed him of the basis of some of the parties opposing him for the college presidency: “The same bunch that opposed Thomas are strongly opposed to you—for political reasons no doubt.” According to James, Elmer Peterson held the support of the state Republicans, including the influential Presiding Bishop of the Church, Charles W. Nibley. He continued, “The significant thing is that they [Peterson’s supporters] appear to have Bishop Nibley’s confidence. The Bishop has the Governor’s confidence, and there’s the ring. Someone of the above crowd is quoted as saying that the Governor would put his foot down on your appointment. Bear in mind that the above is, for the most part, based on rumor and cannot be definitely substantiated.”[10]

While there is little surprise that partisan politics played a role in the selection of such a prominent position in the state, Merrill’s stance on the separation of church and state was another factor limiting his appeal as a candidate. He was too much of a Latter-day Saint for the Gentiles, and too much of a Gentile for the Latter-day Saints. James H. Moyle, Merrill’s close friend, wrote to him, “I thought of your troubles, and the importance of what I say to you relative toward the religious phases of our conversation. I think some non-Mormon friend should discuss your attitude toward religious interference in State affairs. I know you are strongly in favor of the freedom of the Church from outside interference, and just as much opposed to the Church interfering in state affairs.”[11]

In the end, Merrill’s supporters came up short, and Elmer Peterson was chosen as the new president of the agricultural college.[12] Merrill was stoic about his defeat, writing, “I am not a specialist in scientific agriculture. Neither is any other local man who was considered. . . . I cheerfully accept the decision of the board. I hope that Pres. Peterson is the man who can do the most for the College, the State, and education in the state.”[13] Merrill remained at the University of Utah. His position as head of the School of Mines was secure, though his status as part of the university hierarchy was unsure.

With the dust still settling over Kingsbury’s dismissal, John A. Widtsoe arrived at the university. Widstoe openly acknowledged the difficult situation he was entering into. Deep scars remained from the previous year’s battles between the faculty and administration. Widtsoe himself was no stranger to the trouble. The appointment of his brother, Osborne, was one of the key events to which opponents of the school’s leaders pointed as a sign of overt Church influence. Widtsoe acknowledged as much in his memoirs, writing, “Naturally, the faculty were ill at ease. The fight had unnerved them.” Widtsoe took the high road, not mentioning any of his faculty opponents by name, but he did mention that “one professor who had been much trusted by the Board during the upheaval was bitterly disappointed that he was not chosen president. He was thenceforth anything but a supporter of the new administration.”[14] It is tempting to imagine that Merrill was the protagonist Widtsoe described. Merrill was the faculty member the board relied most heavily upon during the upheavals of 1915, and his closeness to Kingsbury meant he was a likely candidate for university president. Still, there is no documentary evidence of antagonism from Merrill upon Widtsoe’s arrival at the university. Though the two experienced some friction several years later, there are no indications that Merrill was the disgruntled faculty staffer Widtsoe spoke about. Widtsoe’s choice to take the high road and not name his antagonist has likely left the issue a mystery forever. If it was Merrill, the two reconciled relatively quickly; by 1918 Widtsoe reappointed Merrill to the position of acting president in his absence.[15]

Unfortunately, the political tumult of 1914, followed immediately by the implosion of the university in 1915, signaled only the beginning of Merrill’s troubles. Under normal circumstances, Merrill, after weathering a difficult time, could have been expected to dust himself off and move on. But the most difficult period of his life was still to come. With the situation at the university settling and his career in a temporary stall, during the months immediately following Widtsoe’s appointment Merrill faced a much more difficult challenge in the place where he spent his most joyful and peaceful hours.

Democratic Dominance

The year of the Democrat in Utah was 1916. The combination of factions in favor of Prohibition, the remnants of Teddy Roosevelt’s Progressive Party, and rising Democratic strength led to the end of the Republican dynasty that had ruled over Utah since the turn of the century. A large number of young, progressive members of the Democratic Party met together and nominated Joseph F. Merrill as a candidate for governor. Merrill demurred, saying, “I shall not seek the nomination, but if it is given to me I shall be willing to enter upon a vigorous campaign for election.” He then outlined his platform: “I am for statewide prohibition; for honesty, efficiency, and economy in the administration of public affairs; for the greatest possible educational, social, and economic development of the state, to be secured by cooperative efforts of our educational, civil and business organizations, and for progressive Democratic state platforms of recent years.”[16]

Merrill was nominated at the August 1916 convention along with a stable of well-known Utah Democrats, including A. W. McCune, Stephen L. Richards, and Simon Bamberger.[17] Bamberger won the nomination,[18] and the Democrats swept to a decisive victory the following November, with the Salt Lake Tribune noting, “Not only did the Democrats elect every man on the state ticket by tremendous pluralities, but they swept practically every count in the state and overturned commanding Republican majorities in each house of the state legislature.”[19] So complete was the victory that eight of the nine state senators and forty-three of the forty-five house members were Democrats. The election of Bamberger swept in a brief period of dominance by the Democratic Party in Utah politics. Yet Joseph F. Merrill, a key party leader, was noticeably absent from the list of appointees and the celebrations surrounding the victory.

Things Given and Taken Away

Merrill’s absence is most simply explained by his failure to receive the party’s nomination for governor. However, a deeper examination reveals tremors in the most placid part of Merrill’s life: his home. In August 1915 the cancer that Laura Merrill had battled six years earlier resurfaced. After the operation that had removed her kidney in 1909, Laura’s health had improved rapidly, and the rhythms of family life had reasserted themselves. Only two months before the cancer reappeared, Laura gave birth to their seventh and final child, a little girl who received her mother’s name.[20] A few weeks after the arrival of the baby, a new growth appeared on Laura’s abdomen. She received two examinations from separate doctors; both declared the tumor inoperable. As the weeks progressed, the tumor continued to grow and soon was easily felt from the surface.[21]

When Merrill found out that there was no surgical option, his scientific tendencies took over, and he began seeking newer and more radical treatments to save his wife. Seven weeks after the tumor appeared, he wrote to Howard A. Kelly, a doctor at Johns Hopkins University, desperately searching for a solution: “Knowing that you are an expert in radium and x-ray treatments, it occurred to me that you are in a position to pass an opinion as to the likelihood of any such treatment being beneficial in this case.” His descriptions of Laura show that the effects of the cancer had not yet taken a firm hold: “The patient has lost a little bit in weight, though her general health during the last seven weeks has been excellent.”[22]

When Kelly wrote back asking Merrill to bring Laura to Baltimore for treatment, Merrill wrote back explaining the difficulties in paying for the trip and the “knotty problem” of arranging care for seven children, including a five-month-old infant.[23] By November the tumor was easily felt and as large as “two thirds the area of a hand.”[24] During this time, Joseph and Laura traveled to the East, visiting Boston and probably Baltimore, though the hectic nature of these months left little in the way of a documentary record.[25] According to Merrill’s journal, she also received X-ray treatments in Salt Lake City.[26]

One letter from Joseph’s mother, Maria, to Laura during this time emphasizes the gravity of Laura’s illness: “You are not a person to give up. . . . I want to say [to] you I know your heart is pure. You know your past life has been devoted to the Lord’s work and you know they tell us he is more merciful that you know. . . . Plead with him. We are all pleading. . . . How can our loving father deny us?”[27]

Laura’s health continued to deteriorate over the next year. Notations about Laura’s illness in Joseph’s journal are brief and few. Laura and Joseph exercised spiritual options along with physical treatments to fight the illness: she received priesthood blessings along with her x-ray treatments.[28] The last mention of her in his journal was made on Christmas Day, 1916: “Laura was carried down to dinner.”[29] Laura finally succumbed to her cancer two months later on 26 February 1917.[30]

Laura’s death was a wound Joseph F. Merrill never fully healed from. The only clear portrait of her emerges from her letters to Joseph while he was studying in the East; it is a portrait of a vibrant, intelligent young woman, Joseph’s intellectual and spiritual equal in many ways. Laura’s work as a community activist is impressive, particularly considering her young family. Before her death she served as the president of several women’s organizations. The Salt Lake Tribune characterized her as “one of the best known women of the city and state.”[31] Laura served as the vice president and a director of the Utah Federation of Women’s Clubs, president of the Women of the U of U, and president the Authors’ Club, a literary society.[32] Only a few months before the reoccurrence of her cancer, she completed a two-year term as president of the Daughters of Utah Pioneers.[33]

Laura’s death haunted Joseph. He idealized her and pined for her in the years following her death. Joseph’s journal entries were normally brief, but occasionally his melancholy overcame him and his feelings burst out on the paper. A few years after Laura’s death, he wrote, “If only she could come back to me—the mother of my children—the best wife that ever lived—the most loyal, devoted, helpful companion ever given to man.” He continued, “I hope I would know how to treat her; at times I am lost in ecstasy of delight when I dream how delightful life would be if only she were here as my helpmeet.”[34]

To his daughters he held up Laura as an ideal of womanhood. He wrote to his daughter Edith, “She herself was energetic, she wanted to be an honor to her forbears, most of all to her grandfather John Taylor, whom she greatly admired. So she was ambitious. But her dominant characteristic was loyalty. No man ever had a more devoted and loyal wife than I had—your mother. . . . God bless her memory, God bless her children. May they never forget her ideals!”[35]

Millie

Joseph would soon court another wife. Emily Lizette Traub had a completely different background and temperament than Laura Merrill. Laura was the grandchild of two Latter-day Saint Apostles, born and reared in one of the largest and finest houses in Salt Lake City; Emily was the daughter of German immigrants, her father a Lutheran minister. Laura was an energetic Latter-day Saint her entire life; Emily was a convert to the Church at the age of forty. Laura was a whirlwind of activity, and her home was the scene of many prominent gatherings of the numerous women’s organizations she belonged to. Those who knew Emily described her as “reserved,” though she was a successful teacher at the university.[36]

Emily Traub Merrill married Joseph F. Merrill in 1918, a year after his first wife, Laura, died from cancer. Where Laura came from some of the most prominent familes in the Church, Millie was a new convert with almost no background in the faith. Photo from Descendants of Marriner Wood Merrill, 461.

Emily Traub Merrill married Joseph F. Merrill in 1918, a year after his first wife, Laura, died from cancer. Where Laura came from some of the most prominent familes in the Church, Millie was a new convert with almost no background in the faith. Photo from Descendants of Marriner Wood Merrill, 461.

Emily Traub was born in Peoria, Illinois. According to family accounts, her father was educated in the top-ranking universities of Germany sometime before immigrating to the United States. Emily came to Salt Lake City in 1917 to visit a younger sister who had married a local man. While in the state, she enrolled in the summer session at the University of Utah. Traveling to the school, she walked two city blocks on First South, then took the streetcar the rest of the way. On his way to work in the School of Mines, Joseph F. Merrill walked the same two blocks and took the same streetcar, and that is where they met.[37] In his journals, Joseph called her “Millie.”[38]

While there exist volumes of correspondence between Joseph and Laura during their courtship decades earlier, only a few facts and one letter tell the story of how Emily became Joseph’s second wife. At the end of the summer of 1917, Emily returned to her teaching career in Indiana.[39] She and Joseph corresponded after she returned home, and by January Joseph proposed that she come to Utah to be his wife. She was understandably hesitant.

In a letter to “My darling little girl” (Joseph was ten years her senior) in January 1918, Joseph wrote, “You want to be ‘absolutely sure that you are not making the biggest mistake of your life.’ Well, I can give you the key. ‘Be sure of your heart and follow it.’ There is always danger in marrying without love.”[40] Merrill’s letter also revealed much about his state in the wake of his first wife’s death: “I am anxious restless lonesome weary—more the last eleven months than in all my life before. I want a sweetheart.” He also cautioned, “I cannot and will not offer to take the hand of a girl whom I do not dearly love. To do otherwise would be to sin against her as well as myself.”[41] While only Joseph’s side of the conversation remains, it is clear that Emily returned his affections, however reticent she was to leave her life in Indiana. Joseph reminded her, “You have written that you will ‘smother’ me with your love. I have believed you and still do.” Joseph, anxious for a companion, brushed aside her concerns: “Neither of us know the other as well as we will after years of marriage but each of us know the other enough to know that we are safe if our hearts to each other are true. . . . Give me your heart and come freely, willing and you will find a heart as true as was ever given to woman.”[42]

By the summer of 1918, Millie agreed to marry Joseph. In late June, Joseph made arrangements to attend an engineering conference in Chicago, and he quietly confided to a few friends that he would be returning to Utah with a new bride. During her year of correspondence with Joseph, Millie had accepted the gospel of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and Joseph baptized her on their wedding day. The baptism and marriage took place in Fort Wayne, Indiana, presided over by German E. Ellsworth, the president of the Northern States Mission.[43]

Joseph’s second marriage took place just sixteen months after Laura’s death and undoubtedly caused some upheaval at home. For over a year Merrill had been a single parent to seven children, and his need for a “sweetheart” and a mother to his children was obvious. Regardless of the logical rationale for the marriage, it was a difficult transition for all involved. The children called her “Aunt Emily,” borrowing an old colloquialism usually used for wives in polygamous families. Many years later, Merrill’s oldest daughter, Annie, wrote, “We felt we could not call her ‘Mother’ as she desired since we were older, and mama was so near and dear to us.” Annie also admitted the difficulties Millie faced as she adjusted to the new life she was suddenly thrust into: “She was expected to raise seven children ages from three to nineteen. Besides she had to live in her predecessor’s home.” Millie was not only living in a new home with a new family but also being fully immersed in a new culture. Annie noted, “She being a convert and not one of the ‘old guard,’ the neighbors, relatives, and friends were negligent in welcoming her to their circles.”[44]

Another Loss

With another strong woman by his side, Joseph’s life was beginning to come back together. However, his work at the university was again disrupted when the nation entered the First World War, and Merrill became an energetic supporter of the cause. Merrill was appointed to the Emergency and Defense Committees and began to use his political connections to bring military training to the university. He wrote to his Utah senator, William H. King, “Out in Utah we wonder what is wrong with the University of Utah. . . . Why is it that since the Government is in such dire need of the services of men trained in the various lines indicated, that the University of Utah may not have men stationed at Fort Douglas devoting part of their time undergoing training? . . . We could handle as many as 300 men and we would like to do it.”[45]

The military did come calling to the university. In the summer of 1918, a few months after Merrill wrote to Senator King, Merrill’s oldest son, Joseph Hyde Merrill, was drafted into the Student Army Training Corps (SATC) along with nearly all of the university’s male student body. The younger Joseph, described by his siblings as a “healthy, alert, intelligent, obedient child,” was just registering to take his first engineering courses when his call to service came. The SATC itself was in a state of disorganization. According to one frank history of the campus at this time, “The [SATC] from the beginning proved bad, the double supervision by military and University officers producing many difficulties. . . . Most of the boys had not been hardened by any preliminary training and, as a result, found their double duties as students and soldiers impossible to perform properly. It was not uncommon to see tired soldiers in recitation and student rooms, slumped in their seats, asleep over unlearned lessons. Students marched to and from classes, to and back from the mess halls, and then to library or other rooms for ‘supervised study.’”[46]

The conflict between university authorities and military leaders became a matter of life and death when the Spanish flu pandemic arrived in Salt Lake City in the fall of 1918. Soon after the opening of the school year, the university declared a vacation until the end of the plague, sending home all students, including the draftees. The military soon countermanded the dismissal of the students, sending notice for all recruits to report back to the campus barracks. In crowded army housing, the flu was particularly deadly, and the university was soon overflowing with sick cadets.[47] Joseph Hyde reported for induction in the SATC just after Thanksgiving. By the first week of December he was gone, a victim of the merciless disease.[48] He was one of twenty-eight university recruits who fell victim to the pandemic.[49] His death came in the midst of accusations by soldiers’ parents of the camp’s lack of blankets, proper clothing, and forced drills in stormy weather.[50]

For the elder Joseph, the death of his son was a harsh blow, following so soon upon the death of his wife. Cautionary conditions against the flu ruled out a proper funeral, so only a small graveside service was held.[51] Less than a year before, Merrill had asked William H. King to bring military training to the U, and now his son was an indirect casualty of the war. He again wrote the senator, this time to thank him for his note of condolences sent after young Joseph’s passing. Merrill was stricken but tried to put on a brave show, writing, “My son was a member of the SATC and died of influenza, December 3rd at the Post hospital; and therein lies the saddest feature of his passing. Could he have died on the battlefields of France, we could have been more reconciled to his going. However, we have to bear, of course whatever befalls us, and it was no worse for him to be stricken with that disease than for the thousands of other many young fellows who went in the same way.”[52]

Reforming the University

Merrill’s actions surrounding the death of his son suggest he coped with these shattering events by throwing himself into his work. He admitted in a note to President Widtsoe that the death of his son “was so unexpected and sudden that the blow stunned us” but only the next day wrote another letter to Widtsoe advising him to reopen the school as soon as possible.[53]

Conditions at the university improved under Widtsoe’s leadership. Recognizing the policies and lack of communication under President Kingsbury that led the faculty to revolt in 1915, Widtsoe initiated a series of reforms. The new “Laws and Regulation of the University of Utah” more clearly outlined the duties and responsibilities of the university’s governing organizations. More generous guidelines appeared for the faculty involved in political activities. The Board of Regents presented a new ruling, stating that it “does not regard it as undesirable that a member of the teaching force should take part conservatively in public activities.” Perhaps even more importantly, the new laws declared that “academic freedom in the pursuit and teaching of knowledge shall be maintained by the University of Utah.”[54]

Merrill praised Widtsoe for the reforms, writing, “I congratulate you upon the skill, wisdom, and ability that you display in your work.”[55] At the same time, Merrill held strong concerns about the way the university was operating, and he urged a series of even more dramatic reforms. Removed from the prominent position he had held when Kingsbury was the head of the school, Merrill was fearless in his criticism of leaders and teachers who he felt kept the school from reaching its full potential.

In June 1920 Merrill wrote an open letter to the Board of Regents expressing dismay over the salary of the professors at the university. He pointedly told the board that, with the exception of President Widtsoe, “the streetcar men are paid more than University professors.” He advocated a 10 to 20 percent increase in salaries and told the board the move could be made feasible by “eliminating all expenditures not really necessary and by requiring all full-time employees to put in full-time doing only necessary work.”[56] Merrill followed up the letter with six pages of handwritten suggestions concerning the inefficiencies at the university. He told the board that “the feeling is general among university employees that they are underpaid.”[57]

On the surface, Merrill’s criticism of the university might seem like an attempt to curry favor with the faculty, but when he specified the source of the problems, he was also critical of inefficiency among the employees. He wrote, “To a considerable extent there is a lack of discipline among the employees of the University; and the Faculty is here again largely to blame for this. Our system is at fault. . . . These conditions make for looseness, and inefficiency and waste.”[58] Merrill was critical of any university official, even the deans of the respective schools, who did not carry a full teaching load. He pointed out unnecessary luxuries, such as automobiles provided for university officials.[59] Merrill’s approach failed to make many friends among either the regents or the faculty. Anthon H. Lund interpreted Merrill’s comments about salaries at the university as a criticism of privileges given to the president.[60] Lund felt that Merrill’s “complaint was more against the Regents than against Widtsoe.” When another regent called for a committee to look into Merrill’s suggestions, Lund refused to vote, writing, “I considered it a bad precedent to allow teachers, who get disgruntled, to have the privilege to spread dissatisfaction among their fellow teachers.”[61]

“Disgruntled” is probably the wrong word to describe Joseph F. Merrill at this point in his life. “Anxious” may fit more properly. Merrill was in his fifties and well into his third decade as a faculty member. He was still ambitious and deeply in love with the university, and he was anxious for the school to reach its potential.

Merrill’s best chance to reform the university came in 1921 when Widtsoe departed to serve as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. The Board of Regents, remembering the controversy surrounding Widtsoe’s appointment five years earlier, began a thorough search, inside and outside of the university community, for a proper candidate to serve as the new president. The faculty was invited to select three of its members to act in concert with the regents in selecting the new president. At a special meeting, the faculty chose to conduct a preferential vote to communicate their wishes to the board.[62] The faculty voted overwhelmingly to choose the next president from among their own number.

Merrill desperately wanted the position and saw himself as the best candidate to bring all the disparate parties at the school together. He wrote to a friend, “I know the University of Utah from A to Z. I know the state of Utah from one end to the other. I know the people of the State—Mormon, Gentile, and Jew as no other man can know them who had not lived here for many years. It seems to me, therefore, that I am in a better position to serve the University as President than any man who could be brought in from the outside.” Merrill knew this was likely his last chance to become president, and he also recognized the forces aligning against him. He admitted, “This is selfish propaganda. But if the usual methods followed by corporations and business concerns are followed there can be no doubt as to who the next President of the University of Utah will be.” Admitting his willingness to pull out all the stops, he concluded, “Modesty, you see, has flown out the other window.”[63]

Merrill was among the candidates selected, along with James Gibson, dean of the School of Arts and Sciences; Milton Bennion, dean of the School of Education; and George Thomas, a professor of economics.[64] Gibson, known among the faculty as “the leader of the opposition,”[65] won the majority of the ballots, but Merrill was close behind. Merrill tied George Thomas twice and received more votes once during the first three rounds of voting. On the final ballot, the faculty were allowed to select a first, second, and third choice. Gibson received the most “first choice” votes, with Merrill and Thomas tied for second. With all the votes counted, Merrill tied with Gibson and surpassed Thomas by six votes.[66]

The Board of Regents also surveyed candidates outside the university, but the prevailing feeling favored the selection of a president from among the faculty. With favor among the faculty and the board, Merrill was a top candidate. However, after six ballots, the board chose George Thomas as the new president of the university.[67] Merrill chose to write nothing in his journal or existing correspondence about the election, but the defeat must have been a bitter pill. In contrast with Merrill’s decades of experience, Thomas had arrived at the university only in 1917. Three months prior, Thomas had made a successful run as a Republican candidate for the state superintendent of public instruction, but he resigned to fill the presidency.[68] At this point, Merrill’s own political ambitions with the Democratic Party had ceased to exist. The momentum he possessed a decade earlier had evaporated in the controversies fought at the university. The hardship of Laura’s death and the ensuing string of tragedies sapped his financial resources. When his name was floated again in 1920 as a candidate for governor, his mother wrote despairingly, “You cannot afford to run for governor, even if you get the nomination.”[69]

Merrill’s relationship with Thomas began cordially and then turned chilly. Shortly after Thomas’s inauguration, Merrill wrote a letter asking for an outline of his own responsibilities, explaining, “I do not wish to be ‘butter-in’ but I do wish to work in harmony.”[70] Thomas acknowledged, “I know that you have been here a long time, and I certainly feel that you have the interests of the university at heart.” He told Merrill to “go on in an even tenor of your way, very much as you have done.”[71]

The two came into conflict a few months later when Thomas initiated a series of reforms, raising the course requirements for students. Merrill protested the move by circulating two letters among the faculty and students that explained the danger of the new standards overwhelming the students. According to Thomas, several faculty members complained about Merrill’s tactics, and Thomas sent him a stinging letter, warning “that the letter would tend to break down the very thing that the Administration has been attempting to establish, that is—good standard courses.”[72] This in turn elicited a sharp response from Merrill, who shot back, “I shall never cease to be surprised and astonished at what you wrote and to believe that my circular letter did not warrant the content of yours.” Explaining his position, he continued, “May not this standard be violated by asking a student to do too much work as well as by asking him to do too little?” At the real heart of Merrill’s grievances was his objection to Thomas’s attempts to interfere with what Merrill saw as the freedom of the teachers to determine their own standards. “Every instructor would like to be just as free and independent in his work as possible, . . . and the less restraint the president imposed the better he would like it.”[73]

Merrill did offer a mea culpa near the end of his letter, assuring, “I do not wish to hamper you in administering the affairs of the University of Utah. I love this institution. I have only its best interests at heart.” He even went so far as to offer his resignation: “The moment you wish me to step aside and give place to someone who can serve more effectively than I can, all you need to do is tell me.”[74] Thomas wrote back, “I have no disposition to replace you, and when I do—if ever—I shall come to you very frankly and ask you to retire. Until that time, I think you can feel that you have my confidence and support.”[75]

“Why Are Things as They Are?”

Merrill’s restlessness at the university was only symptomatic of the larger sense of dissatisfaction he felt with the direction of his life. In truth, the series of disappointments he faced over the preceding several years left him reeling. His career at the university was in a state of stasis, with no immediate possibilities of advancement. His once promising career in politics was all but over. Close professional colleagues like John A. Widtsoe and Richard R. Lyman had left the university and moved on, both to serve in the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. What weighed most heavily on his soul was his home life. His relationship with Millie was stormy. “Wife, who had been sulking for ten days went to a movie,” he recorded. “Oh how I hate sulking!”[76] The normally stoic Merrill typically recorded only terse entries in his journal, the most common being, “At ‘U’ all day.” But early in 1923 his feelings spilled out onto the page, and he wrote a long entry explaining his despair over the state of his life: “How many times have I repented! How much bitterness has come into my life?” He wondered if he and Millie, with their different backgrounds, could find the kind of harmony he knew in his home life before Laura’s death: “The joy, the sweetness, the delight of living with a congenial companion can hardly be realized by those yoked together whose temperaments are as widely different as Millie’s and mine seem to be.” He lamented, “How sad have I been the many times to see my dreams of a happy home life vanish into nothingness. . . . I am a home man. I like the home, the quiet the peace, the freedom of home.”[77]

After six years, Laura’s death still haunted him. He pined for her return: “If she could only come back to me—the mother of my children—the best wife that ever lived, the most loyal devoted, helpful companion ever given to man.” He continued, “When I dream about her at times I am lost in an ecstasy of delight—when I dream how delightful life would be if only she were here as my helpmeet.”[78] At times he was filled with guilt over Laura’s loss, writing, “During her married life I did not fully appreciate her virtues and value. I realized these only when she was gone. Would that with my knowledge I could go back 20 years in my life! I would show her some of the appreciation to which she richly deserved.”[79] He idealized her in his reminiscences: “Not one minute of sleep did I ever lose owing to a disagreement with her. . . . It was part of her ‘religion’ to ‘never let the sun set on thy wrath.’ . . . She made my home a real, real home for me. Oh why did she have to go[?]”[80] Merrill’s lamentations deal more with his longing for Laura than with his dissatisfaction with Millie as a companion. But he did feel that he may have moved too quickly to remarry after Laura’s death. He wrote, “If only my wife were sympathetic, amiable! How important is the marriage step! . . . I trusted too much. I took too much for granted. I hoped too much. I acted hastily.”[81]

His despair during this time came not only from the loss of his first love but also from the continual disappointment he endured during the years since her death. He cried out, “Why are things as they are? Do I deserve the disappointments of the last seven years? Have I not deserved better things?” He blamed himself for his state but tried to see the bright side of his suffering: “I presume what I suffer is the result of my folly. I presume my experiences are designed to discipline me—to give me knowledge. At least I think I am a wiser man now than I was then. How long shall my miseries continue? I do not know.” His discontent is clear, but he consoled himself, affirming, “Happiness is a condition of mind,” vowing to “look forward, not backward, and determine to see the silver lining of every cloud.”[82]

The exact reason why Merrill’s feelings boiled over into his journal during this brief period of his life is unknown. It is clear that his new life with Millie was an adjustment. As a convert to the Church, Millie was thrust into a completely different culture, a factor that undoubtedly accounted for some of the tension in the relationship. Millie was shy and retiring, and suddenly becoming a mother to seven children was an overwhelming task. By all outward indications, she did her best to manage a difficult situation. In her letters to the Merrill children, she is devotedly involved in their concerns.[83] At the same time, she retained a sense of independence. She continued her studies at the university, much to the perplexity of her new family. Joseph’s mother wrote to him, “I cannot understand why Millie at her age would want to burden herself with so many lessons. I would think she would prefer remaining at home and enjoying it, when one has so comfortable a home instead of all the time living that mad rush to get to school. It ages one faster than work and our time is short here anyway.”[84] Millie continued her studies, receiving a bachelor’s degree from the university in June 1922, the same day as two of her stepdaughters, Annie and Edith. All three garnered high enough grades to receive membership in the honorary scholastic society Phi Kappa Phi.[85]

Fatherly Advice

During these difficult times, Merrill found solace in his children’s accomplishments.

With his own hopes stalled, it comforted him to see the progress of his progeny. “My pride and joy from now on is going to be largely in seeing my children succeed,” he wrote to one of his daughters in 1923.[86] He was deeply involved in their education, particularly when they reached the university. His children told tales in later years about how he managed their education, even scheduling the classes they enrolled in. Annie, his oldest surviving child, graduated from the university in three years with two majors, home economics and physical education, a feat she credited to her father’s careful scheduling. When Annie left the university, she took a teaching position at Brigham Young College in Logan, Utah. After three years, she received a scholarship to study public health administration at the University of California in Berkeley. After one year at Berkeley, she married and settled in Tucson, Arizona.[87]

Merrill’s most revealing correspondence from this time is with his daughter Edith, who followed a more adventurous path. After studying Spanish at the University of Utah, Edith departed in the summer of 1921 to live in the tiny Mexican village of Mogote to immerse herself in the language. In Mogote she lived with a local family in a small adobe house, where “water came from a single well and kerosene lamps gave light at night.”[88] Edith reveled in the simplicity of life in the village, spending her weekends with the local young people at dances where a single fiddler provided the only music. In his letters to Edith, Merrill fretted over her diet, advising her to avoid fried foods and pointing her toward “fruits, vegetables, raw turnips, carrots, cabbage, milk, eggs, cheese, whole wheat flour, oatmeal, etc.” He included a reminder that “pimples and grease and fries, etc. go together.”[89] The next year when Edith left the country again to further her studies at the National University in Mexico City, she decided to stay on for an extra six weeks, prompting a letter from her father, who failed to conceal his disdain for the plan. “The ‘family’ doesn’t think very favorably of your proposition to stay out of the Univ. and run around for six weeks with Mexican officers,” Merrill wrote to Edith. “The ‘family’ thinks you went to Mexico to study in the Univ. there and to see and hear what might be incidentally gathered in pertaining to Mexico and things Spanish.” He urged his daughter to “try to summon to your use the best common sense of your ‘forebears’ and act accordingly” and to “guard against the temptation, should there be any, to act foolishly.”[90] Following his advice, Edith did return to the University of Utah to complete her graduate work.[91]

Merrill’s letters to Edith during this time reveal his deep faith in the tenets of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and his anxiety for his children to remain true to their religious upbringing. “Happiness in this world and in the world to come depends on our being true to the Faith,” he wrote to Edith. He worried over his daughters finding spouses of the same religious persuasion. His wish was “a clean, earnest, ambitious Mormon boy for each of you girls.” He continued, “I hope both of you will have always pride and womanhood enough to refuse any man who does not really love you. You girls are well-born. You deserve the best, but clean, energetic, manly Mormon boys are the ones to whom you should look.”[92]

Merrill’s public sentiments matched those given privately to his children. With a number of his former colleagues from the U now serving in the Latter-day Saint hierarchy, Merrill received new opportunities to speak out as a scientific expert expounding the virtues of faith. At a time when controversies regarding science and religion raged throughout the United States, including the famous Scopes Monkey Trial in Dayton, Tennessee, Merrill tackled the challenge head-on. The controversy at the time was less between science and religion than between modernism and fundamentalism. Modernists consisted primarily of biblical scholars advocating a scientific approach toward the Bible. Fundamentalists stressed a literal interpretation of scripture. In each camp there remained a spectrum of views, with some modernists rejecting all biblical miracles including the divinity of Christ, and some fundamentalists viewing the Bible as infallible.[93]

In an address delivered in the Salt Lake Tabernacle, Merrill staked out ground between the two extremes. “We witness an increasing number of ecclesiasts of high and low degree—bishops, pastors, ministers, teachers—members of practically all Christian denominations—rising up and doing their bit to establish modernism—which rejects the divinity of Jesus Christ,” Merrill declared. “This Church is a fundamentalist organization. It is founded upon the divinity of Jesus Christ,” Merrill continued, clearly placing the Church in league with conservative forces. “Take away the divinity of Christ and you take away the foundation stone of the Church.” At the same time, he saw scientific method as a vital tool for both faith and reason: “We see and feel and handle objects about us such as clothes and chairs and food and other familiar things of everyday life. . . . We believe in these things—we know they exist. And the chemist has analyzed them. He tells us that the vast multitude of objects found in our material world are composed of a relatively small number of elements. Thirty years ago the chemist told us the atom was an inconceivably small, invisible unit without parts. . . . But today he tells us something different and some more about the atom.”[94]

To Merrill, the acceptance of ignorance about certain subjects was a key part of faith and reason. He continued, “The scientist must live and walk and work by faith, for otherwise he does not progress. . . . Faith is an essential quality of the scientist as well as of the Christian. Both are faced with many facts that they cannot explain. But because of this no one could in reason expect the scientist to give up his work. Why should a Christian be expected to give up his faith when faced by things he cannot explain or does not understand?”[95]

In another address given in the Salt Lake Tabernacle, Merrill spoke out in defense of science and elucidated its place within the lives of the faithful. In Merrill’s view, “Latter-day Saints, if they are good Latter-day Saints, are also tolerant to the spirit of science as they are tolerant to the spirit of religion.” Similarly, “The true scientist is perfectly tolerant. The true scientist is working only for the discovery of truth. . . . The true scientist we look upon—and must look upon, if we are true to the teaching or our Church, as an agent of divinity, in his efforts to bring truth.” He concluded by reiterating his cherished belief in common ground: “The Church, as a church, has no quarrel with science. It has no quarrel with anyone who is true to the spirit of science, or with the doctrines of science because we believe that ‘truth is truth, wherever found, on heathen or on Christian ground,’ and that truth cannot be in conflict with itself.”[96]

Even as he became more widely recognized as a defender of the Church, Merrill remained vigilant against any kind of discrimination based on religious leanings at the university. When a friend asked Millie if students who were not Latter-day Saints became targets for discrimination at the school, Merrill quickly fired off a letter in reply, defending the U as a haven for religious and political neutrality in the state. “I do not know the political affiliations of the great majority of my colleagues,” he explained. “Religious and political affiliations are always regarded on campus as a man’s private affair.”[97] Thirty years before, when Merrill arrived at the university, he saw it as a no-man’s-land between the Latter-day Saint and nonmember factions of the state. Now he took pride in its status as a place without factionalism: “The campus of the University of Utah is the freest spot in the whole state from religious bias and it is right, of course, that it should be so. Nowhere else in the State, I believe, do people mingle and associate with such freedom from religious and political bias as they do on the campus.”[98]

A New Calling

With his career at the university stalled, Merrill still fiercely fought on behalf of the School of Mines. He believed firmly that “the Mining School of the University was situated more favorably for the study of Mining, Metallurgy, and Geology than any other mining school in the country.” He urged Thomas to put more hard work, advertising, and money into helping the school rise to national prominence.[99] At the same time, he felt overworked and underfunded. He wrote to Thomas, careful to explain, “I am not charging or complaining that any department on the campus receives too little money,” but he believed that “my department receives relatively too little, and the only way that I can see is to keep the expenses of class teaching down to a minimum.”[100] Reaching for more funding, he agreed to teach more classes, feeling strongly that “the interests of the students in my department will . . . be best promoted by more equipment rather than by more teachers.”[101]

Merrill’s departure from the university came suddenly in late 1927 when Church leaders asked him to serve as the head of the Church school system. Honored and delighted to receive the call, he quickly accepted and tendered his resignation to the university. He felt pride in his service to the university, noting that in all of his years there, “Not once did I have to miss a class or other University appointment due to ill health.”[102] Filled with excitement over his new position, he left the U behind with little reflection. He was ready for the change. He wrote to a friend, “It was in January 1893 that I was elected a member of the faculty of the University and it was in January 1928 that I resigned—just thirty-five years after my election. I have been there so long that some of my friends can hardly think of me in any other connection. However, I find the new position delightful.”[103]

Joseph F. Merrill was fifty-nine years old when he resigned from the University of Utah. The university had served as his home for more than half of his life. It was the site of his greatest accomplishments and most stinging failures. He left behind a lifetime of work building the School of Mines and Engineering from the ground up. At an age when most men begin to contemplate a happy retirement, he embarked on the busiest, most productive period of his life. Merrill’s greatest legacy was about to emerge.

Notes

[1] Joseph Horne Jeppson, “The Secularization of the University of Utah,” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1974) 199.

[2] “Alumni Adopt Resolutions Condemning Regents’ Actions,” Utah Chronicle, 7 February 1916, 1.

[3] “Alumni Adopt Resolutions Condemning Regents’ Actions,” Utah Chronicle, 7 February 1916, 1.

[4] “Regent Will Resign,” Utah Chronicle, 7 February 1916, 1.

[5] “College Trustees Make Selection of President to Succeed Dr. Widtsoe,” Logan Republican, 19 February 1916, 1; George Thomas Faculty File, box 9, folder 9, Ralph V. Chamberlin Papers, Utah State Historical Society.

[6] These letters may be found in box 1, folder 4 of the Joseph F. Merrill Collection, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[7] J. M. Mills, et al. to Lorenzo N. Stohl, 5 February 1916, box 1, folder 4, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[8] Unsigned letter, box 1, folder 4, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[9] Joseph F. Merrill to John Dern, 15 February 1916, box 1, folder 4, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[10] James Merrill to Joseph F. Merrill, 12 February 1916, box 1, folder 4, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[11] James H. Moyle to Joseph F. Merrill, 5 February 1916, box 1, folder 4, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[12] “College Trustees Make Selection of President to Succeed Dr. Widtsoe,” Logan Republican, 19 February 1916, 1.

[13] Joseph F. Merrill to John Dern, 18 February 1916, box 1, folder 4, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[14] John W. Widtsoe, In a Sunlit Land: The Autobiography of John A. Widtsoe (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1953), 132–33.

[15] John A. Widtsoe to Joseph F. Merrill, 17 August 1918, box 10, folder 18, Widtsoe Presidential Papers, University of Utah (U of U) Archives.

[16] “University Dean Is Candidate for Governor,” Salt Lake Telegram, 10 August 1916, 2.

[17] “Governorship Battle Lively Field Is Full of Candidates,” Salt Lake Tribune, 17 August 1916, 5.

[18] “Bamberger Choice for Governor,” Salt Lake Tribune, 19 August 1916, 1.

[19] “Clean Sweep Made in State by Democrats,” Salt Lake Tribune, 11 November 1916, 1.

[20] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill and Annie Laura Hyde Merrill (Salt Lake City: privately published, 1979), 115.

[21] Joseph F. Merrill to Howard A. Kelly, 19 October 1915, box 2, folder 2, Merrill Collection, Church History Library (spelling corrected).

[22] Joseph F. Merrill to Howard A. Kelly, 19 October 1915, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[23] Joseph F. Merrill to Howard A. Kelly, 1 November 1915, box 2, folder 2, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[24] Joseph F. Merrill to Curtis F. Burnam, 17 November 1915, box 2, folder 2, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[25] Only one letter from this period exists, in which Joseph wrote to a doctor, G. L. Chadwick, of Boston, thanking him for his treatment of Laura’s illness. Merrill to G. L. Chadwick, 5 February 1917, box 2, folder 2, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[26] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 29 September 1916, Joseph F. Merrill Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University (BYU).

[27] Maria Merrill to Laura Hyde Merrill, undated letter, box 2, folder 2, Merrill Collection, Church History Library (spelling and punctuation added). Though this letter is undated, it is located in a folder containing most of the letters dealing with Laura Merrill’s illness, and the context fits the events surrounding her struggle with cancer.

[28] Merrill Journal, 11 October 1916, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[29] Merrill Journal, 25 December 1916, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[30] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 12.

[31] “Mrs. Merrill Dies After Long Illness,” Salt Lake Tribune, 27 February 1917, 16.

[32] “Mrs. Merrill Dies After Long Illness,” 16.

[33] Barbara Dorigatti, “One Hundred Years of DUP,” in Pioneer Pathways, vol. 4 (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 2001), 160.

[34] Merrill Journal, 6 January 1923, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[35] Merrill to Edith Merrill, 19 December 1929, box 14c, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[36] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 13–14.

[37] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 13.

[38] Merrill Journal, 6 January 1923, box 1, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[39] Merrill Journal, 6 January 1923, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[40] Merrill to Emily Traub, 28 January 1918, box 14c, folder 2, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[41] Merrill to Emily Traub, 28 January 1918, Merrill Papers, BYU (punctuation in original).

[42] Merrill to Emily Traub, 28 January 1918, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[43] “Dr. Joseph F. Merrill Marries in Indiana,” Deseret News, 27 June 1918, U of U Faculty Clippings File, U of U Archives. Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill and Annie Laura Hyde Merrill (Salt Lake City: privately published, 1979), 13.

[44] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 13–14.

[45] Merrill to William H. King, 23 January 1918, box 2, folder 10, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[46] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 356.

[47] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 356.

[48] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 18; “Deaths and Funerals,” Salt Lake Tribune, 5 December 1918, 9.

[49] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 356–7.

[50] “Strict Censors at ‘U’ Harass Weary Parents,” Salt Lake Herald, 4 December 1918, 12.

[51] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 18.

[52] Merrill to William H. King, 6 January 1919, box 2, folder 8, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[53] Merrill to John A. Widtsoe, 16 December 1918, and Merrill to John A. Widtsoe, 17 December 1918, box 10, folder 18, John A. Widtsoe Presidential Papers, U of U Archives.

[54] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 346–47.

[55] Merrill to John A. Widtsoe, 9 June 1920, box 28, folder 10, Widtsoe Presidential Papers, U of U Archives.

[56] Merrill to U of U Board of Regents, 4 June 1920, box 28, folder 10, Widtsoe Presidential Papers, U of U Archives.

[57] Merrill Memo, 9 June 1920, box 28, folder 10, Widtsoe Presidential Papers, U of U Archives.

[58] Merrill to U of U Board of Regents, 4 June 1920, box 28, folder 10, Widtsoe Presidential Papers, U of U Archives.

[59] Merrill Memo, 9 June 1920, box 28, folder 10, Widtsoe Presidential Papers, U of U Archives.

[60] Anthon H. Lund Diary, 10 December 1920, in Danish Apostle: The Diaries of Anthon H. Lund, 1890–1921 (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2006), 784.

[61] Lund Diary, 14 February 1921, in Danish Apostle, 790–91.

[62] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 370.

[63] Merrill to H. T. Plumb, 19 May 1921, box 1, folder 4, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[64] Minutes of the U of U Faculty, 14 April 1921, box 5, folder 8, Chamberlin Papers; Chamberlin, University of Utah, 371, 446–47.

[65] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 447.

[66] Minutes of the U of U Faculty, 14 April 1921, Chamberlin Papers.

[67] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 370.

[68] Chamberlin, University of Utah, 373.

[69] Maria Merrill to Joseph F. Merrill, 23 August 1920, box 2, folder 7, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[70] Merrill to George Thomas, 2 August 1921, box 5, folder 7, George Thomas Presidential Papers, U of U Archives.

[71] Thomas to Merrill, 5 August 1921, box 5, folder 7, Thomas Presidential Papers, U of U Archives.

[72] Thomas to Merrill, 14 December 1921, box 5, folder 7, Thomas Presidential Papers, U of U Archives.

[73] Merrill to Thomas, 22 December 1921, box 5, folder 7, Thomas Presidential Papers, U of U Archives.

[74] Merrill to Thomas, 22 December 1921, Thomas Presidential Papers, U of U Archives.

[75] Thomas to Merrill, 22 December 1921, Thomas Presidential Papers, U of U Archives.

[76] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 6 January 1923, box 1, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[77] Merrill Journal, 6 January 1923, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[78] Merrill Journal, 6 January 1923, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[79] Merrill Journal, 9 June 1923, box 1, folder 1, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[80] Merrill Journal, 9 June 1923, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[81] Merrill Journal, 6 January 1923, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[82] Merrill Journal, 6 January 1923, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[83] Emily Traub Merrill to Edith Merrill, 22 August 1922, box 14c, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[84] Maria Merrill to Joseph F. Merrill, 2 May 1920, box 2, folder 7, Merrill Collection, Church History Library.

[85] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 14.

[86] Joseph F. Merrill to Edith Merrill, 17 June 1923, box 14c, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[87] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 20.

[88] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 44.

[89] Merrill to Edith Merrill, 19 August 1921, box 14c, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[90] Merrill to Edith Merrill, 5 August 1922, box 14c, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[91] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill, 45.

[92] Merrill to Edith Merrill, 29 February 1924, box 14c, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[93] See William R. Hutchinson, The Modernist Impulse in American Protestantism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976).

[94] Joseph F. Merrill, “The Reasonableness of Accepting as an Assured Fact the Possibility of Acquiring an Individual Testimony” (address, Salt Lake Tabernacle, 28 February 1926), printed in Deseret News, 6 March 1926.

[95] Merrill, “The Reasonableness of Accepting as an Assured Fact the Possibility of Acquiring an Individual Testimony.”

[96] Joseph F. Merrill, “Tolerance Held by Latter-day Saints Part of Religion Along with Loyalty, Love for All Mankind and Service” (address, Salt Lake Tabernacle, 27 February 1927), printed in Deseret News, 5 March 1927.

[97] Merrill to George H. Dern, 7 May 1924, box 17, folder 5, Thomas Presidential Papers, U of U Archives.

[98] Merrill to George H. Dern, 7 May 1924, Thomas Presidential Papers, U of U Archives.

[99] Merrill to George Thomas, 3 July 1924, box 24, folder 6, Thomas Presidential Papers, U of U Archives.

[100] Merrill to Thomas, 8 April 1925, box 25, folder 6, Thomas Presidential Papers, U of U Archives.

[101] Merrill to Thomas, 3 April 1925, box 25, folder 6, Thomas Presidential Papers, U of U Archives.

[102] Merrill to University of Michigan Alumni Association, 4 February 1928, box 23, folder 3, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[103] Merrill to Louis A. Parsons, 13 April 1928, box 23, folder 3, Merrill Papers, BYU.