Fight to the Bitter End

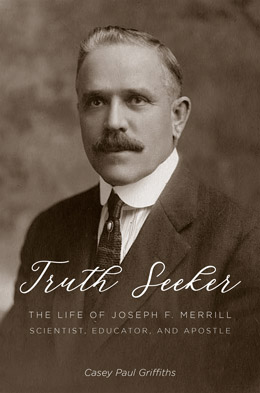

Casey Paul Griffiths, “Fight to the Bitter End,” in Truth Seeker: The Life of Joseph F. Merrill, Scientist, Educator, and Apostle (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 189‒220.

In the early 1930s, the educational system of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints found itself near the end of a major transformation. In the short span of only a dozen years, the Church had all but abandoned its network of loosely associated Church academies in favor of a system of less expensive released-time seminaries linked to public high schools throughout the Intermountain West. As a result, the seminary program grew explosively, quickly becoming the dominant form of Church education. However, an ominous feeling of insecurity hovered over the seminary program. Still less than twenty years old and largely experimental, the program stood on uncertain legal ground. During the 1920s, Church leaders put all of their hopes on the seminaries, hoping no new threat would arise.[1]

With the end of all Church schools now a possibility, Church leaders continued to expand the seminary program. Perhaps without knowing it, Merrill had stepped into a potentially volatile situation. Tension was high, especially in Salt Lake City, over the Church’s aggressive push to start new released-time seminaries. Ultimately igniting this powder keg was the unique set of circumstances surrounding the closure of the high school portion of LDS College in Salt Lake City.

Joseph F. Merrill (center) and the teachers of the Church seminary program at Brigham Young University in the summer of 1929. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Joseph F. Merrill (center) and the teachers of the Church seminary program at Brigham Young University in the summer of 1929. Courtesy of Church History Library.

While the seminary program spread in other areas, it met with opposition in the Salt Lake area because the local school board refused to grant either released time or credit for Bible-study classes. The success of the seminary program outside of the greater Salt Lake area stemmed in part from the willingness of school boards to grant permission for released time to students and offer school credit for classes in Bible study. From its inception, seminary curriculum had consisted of three courses: Old Testament and New Testament, for which credit was granted, and Church history, for which no credit was granted. As a result, in the heart of Church headquarters, students were forced to take seminary before or after regular school hours. Partly because of this, seminary enrollment in Salt Lake remained at about 10 percent of the Latter-day Saint population, compared to an average of 70 percent in other areas. Such a low attendance rate in the heart of the Church, where many of its leaders and their families resided, was not only potentially embarrassing for the Church but also placed these local Church youth in a situation where they might not receive daily religious education.[2]

Even before the closure of the high school,[3] some Church educators believed that conflict over the seminary system was inevitable. Lowry Nelson, a professor at BYU, wrote privately that the seminaries were “destined to sooner or later stir up animosity between the church and other churches. Not a very considerate gesture on our part to fasten them on to the secular system of education, just because we happen to be in the majority.”[4] At the time the seminary system was thought by some to be a foolhardy investment on the part of the Church. Others felt that the Church may have moved too rapidly in closing the academies in favor of the seminary system. At a meeting of the Church Board of Education in 1926, David O. McKay stated, “I think the intimation that we ought to abandon our present Church Schools and go into the seminary is not only premature but dangerous. The seminary has not been tested yet but the Church schools have. . . . Let us hold our seminaries but do not do away with our Church schools.”[5] McKay was right. Despite the blessing of the local school boards and the state board, little legal precedent for the seminary system existed.

Merrill recognized the tension surrounding the relationships between seminaries and schools and did not want to give the impression that the Church was seeking anything beyond what he felt were its legal rights. In his first address as commissioner, he explained, “In all of our system of education we are not trying to get into, we are not trying to dominate, we are not trying to influence improperly, we are not trying to interfere in any way with the public school system of education. All that we are asking is that the members of the Church may voluntarily go during school hours into our buildings, and our own property, and receive religious education.”[6]

The last thing the Church leaders wanted was a confrontation over the seminary system. With the divestiture of Church schools already in progress, the continued operation of the seminaries was crucial to the success of Church education. The worsening economic situation made seminaries more desirable. The Church had reached a point of no return, where any move to reestablish the academy system might not be possible. However, a confrontation was on the horizon.

The 1930 Williamson Report

While all these pieces moved into place, a report to the state school board from Isaac L. Williamson,[7] the state inspector of high schools, was issued on 7 January 1930. The report was a scathing critique of the relationship between Utah high schools and seminaries. At the time, there were few indications that the attack was coming. Merrill had tried to meet with Williamson’s committee before it made its report to the state board but had been refused permission.[8] Church leaders, Merrill included, were blindsided by the report.

Criticism from a man with Williamson’s credentials presented a cause for serious alarm. Williamson, not a member of the Church, was also somewhat of an outsider to Utah politics. A former superintendent of schools in Wikita, Oklahoma, he had completed postgraduate work at Harvard University before coming to Utah to serve as principal of Tintic High School in Eureka in 1912.[9] He was chosen as the first superintendent of the Tintic School District in 1915.[10] Williamson lived for over a decade in Eureka, a town nestled in central Utah’s mining district and one of the few areas of the state without a dominant Latter-day Saint population. Appointed as the state high school inspector in 1923, Williamson’s seven prior years of service as the state inspector gave little indication of any concerns regarding the seminary program. The only entries in the minutes of the state board included a thorough evaluation of a Catholic school in 1926[11] and a minor complaint about seminary classes being held in some rural public high schools.[12] Ironically, a new Church seminary had been announced in Williamson’s home district of Tintic only two weeks before the report was released.[13] Williamson proved to be a formidable and tenacious critic during the ensuing months.

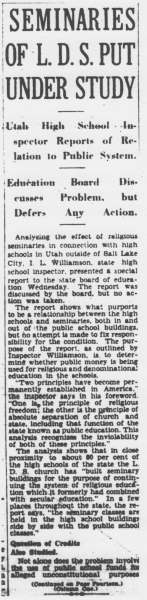

The full text of the report was issued in the Salt Lake Tribune on 9 January 1930. Covering more than an entire page of the paper in tiny print, the report was a thorough and damning accusation against the seminary program, raising a number of serious charges about its constitutionality. Williamson began by pointing out that Utah laws expressly forbade the teaching of sectarian doctrine in a state-controlled school. He questioned whether Bible courses in seminaries were truly free from sectarian doctrine. He went on to show evidence that the Book of Mormon was used to supplement the Bible during Old and New Testament studies. He charged the seminaries with teaching doctrines in credit courses accepted by no other religious body besides the Church, writing, “That the Garden of Eden was located in Missouri; that Noah’s ark was built and launched in America; that Joseph Smith’s version of the Bible is superior to the King James version, and that Enoch’s city, Zion, with all its inhabitants and buildings, was lifted up and translated bodily from the American continent to the realms of the unknown may all be facts, but they are not accepted as such by the religious world in general, and consequently must be classed as denominational doctrine.”[14]

Isaac L. Williamson's school report brought the legality of the Latter-day Saint seminary program into serious question. Courtesy of the Salt Lake Tribune.

Isaac L. Williamson's school report brought the legality of the Latter-day Saint seminary program into serious question. Courtesy of the Salt Lake Tribune.

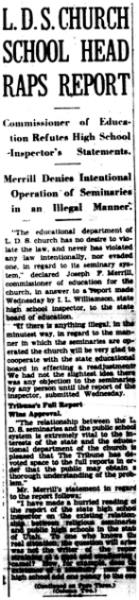

Joseph F. Merrill responded quickly and decisively to save the fledgling seminary system. Courtesy of the Salt Lake Tribune.

Joseph F. Merrill responded quickly and decisively to save the fledgling seminary system. Courtesy of the Salt Lake Tribune.

Next, Williamson questioned whether the current relationship between seminaries and public high schools violated the principle of the separation of church and state. He said that the state was giving financial support to seminaries by allowing students to be transported to schools in state vehicles, where they would subsequently be attending seminary classes during the day. He claimed that high schools’ rooms were being used for seminary classes, heat and janitorial services were being provided from public funds, and school attendance offices were being used to report absences from seminary classes. He even went so far as to claim that students using school study halls to do homework from seminary classes were in violation of the law. In the minds of the public, Williamson charged, the seminaries and schools were thought of as one institution, though he acknowledged that the connection between high schools and seminaries was “somewhat intangible.”[15] The charge was not without truth. It was common practice during the time for most of the seminaries to enjoy a close relationship with their respective high schools. Many high school yearbooks of the time published portraits of the religion teachers side by side with their public school counterparts.[16]

Leaving questions of church and state, Williamson accused seminary classes of causing students to fail in other studies because of overwork, resulting in a lower rate of graduation and a greater rate of failure once students reached the college level. To prove his contentions, he cited a 1926 US Bureau of Education study reporting that student performance in county schools was lower than that in Salt Lake City’s schools. Williamson connected the academic shortfall of the county schools to the time students spent on religious studies compared to Salt Lake schools, which had no released-time programs. From Williamson’s perspective, even if a theology course held more value than a high school course, the schools had an obligation to furnish public education. In his judgment the seminary program was dragging down the academic achievement of the public-school students who enrolled in it.[17]

Continuing, Williamson accused the seminary program of increasing the state’s financial burden, due to the effects of low grades and failures it purportedly caused. The report stated that seminaries were forcing pupils to become “part-time” students since seminary students were taking sixteen units of credit instead of the typical eighteen. Beyond this, the report charged that curriculum had to be adjusted for all students to compensate for those taking fewer credits as a result of seminary. Without giving any specific numbers, Williamson estimated the resultant cost to the state to be “many thousands of dollars.”[18]

Williamson concluded, “The time has arrived when the whole question of the relationship of seminaries to the public schools should receive careful consideration. . . . That the spirit, and perhaps the letter, of constitution is violated by the practice of giving credit in the public schools for something which the constitution prohibits being taught there, and of making the religious education an indirect burden on the public taxpayer is only the opinion of one layman.” He went on to suggest that “the point might be settled by the state judiciary.”[19] The state board moved cautiously to assess the credibility of the Williamson report, appointing a three-man committee to consider the validity of the report’s claims and make recommendations by the end of March 1930.[20]

A Dangerous Time

Given the Church’s financial situation, an attack on the legality of the seminary system could not have come at a worse time. The Williamson report presented a threat not only to the seminaries but to the educational plan of the Church as a whole. By the time Merrill began his service as commissioner, the Church had already thrown its lot in with the seminaries. A return to the academy system at this point would be almost impossible, given the financial trauma caused by the Great Depression. Now the whole educational program of the Church was about to collapse like a house of cards, and Merrill would have to struggle to put the pieces together.

Like most major institutions at the time, the Church’s finances were sinking under the burden of the Great Depression. Merrill’s correspondences during his service as commissioner were filled with pleas for Church educators to be extremely cautious with their funds. To Franklin S. Harris, president of Brigham Young University, he wrote, “The income of the Church is going rapidly from bad to worse, resulting in the First Presidency looking with very grave concern upon every item of expenditure.”[21]

Despite the Church’s rocky finances, Merrill was still optimistic about the future of the system. Even while he arranged for the transfer of the junior colleges to the state, he quietly held a different vision for BYU. Even after the First Presidency decided to begin the process of divesting the Church of the university, Merrill began moving to keep BYU in the fold. In a letter dated 21 February 1929, the day after President Grant declared that the closure or transfer of the university was an option, Merrill wrote to a stake president in Utah Valley, requesting his assistance in taking steps necessary to ensure BYU’s survival. “My own hope and fondest desire is that we may retain the BYU as a senior and graduate institution, eliminating its junior college work, and make the University outstanding, a credit to the Church, and a highly serviceable and necessary institution,” he confided, “but whether this can be done or not will, of course, depend on conditions.”[22] When the announcement was made a few days later that the Church would be closing two schools by June 1930, many at BYU sensed the danger to their own institution. “The whole thing is full of dynamite,” Harris wrote to John A. Widtsoe, sharing his feelings that Church education was headed in a dangerous direction.[23] Seeking to assuage the concerns surrounding the school, Merrill told Harris that he thought it was “perfectly feasible and logical to make the BYU the most outstanding institution between the Mississippi and the Pacific coast. Enough said.”[24]

Over the next few months, Merrill carefully arranged for the transfer of the junior colleges while ensuring his support for BYU. Two months after the Church board’s meeting, Harris had confided in a faculty member that “the little flurry [over the schools’ closures] had died down as far as [they were] concerned.”[25] Then came the Williamson report. With the fate of the seminaries now threatened, the future of the university was as well. It is ironic that the seminaries and institutes, which were intended to replace the Church schools, were now a key factor in Merrill’s strategy for keeping BYU open and under Church control. Before the Williamson report was issued, Merrill had written George Brimhall, head of religious education at BYU, explaining, “The most effective argument I have for the permanency and continued maintenance of the BYU is that we need it for the training of teachers in the Department of Education. I think the Department of Religious Education should be the strongest and most developed . . . of any department in the University.”[26]

To convince the skeptical board members that BYU should be maintained, Merrill had emphasized the one truly unique thing the school could offer: training for Latter-day Saint religious educators. Merrill’s correspondence with Harris during the period indicated his desire to have every seminary and institute teacher trained at BYU and to have them receive master’s degrees in religious education there as well.[27] By making such a bold initiative, Merrill had given the board a solid reason to retain BYU. However, in doing so he had inextricably tied the fates of the released-time seminary program and BYU to each other. If released-time seminary was eliminated, there would be little need for professional religious educators.

To Merrill, BYU was the head of the Church educational system, and the seminaries and institutes were its body. Any threat to one could mean the death of the other. This sudden turn of events could have seriously curtailed Merrill’s efforts to keep BYU alive. Less than two years into his service as commissioner, Merrill was facing disaster unless immediate action was taken.

Merrill’s Response

With so much at stake, Merrill immediately moved to answer Williamson’s accusations. The same day that the report was published, Merrill fired back by publishing a lengthy response in the Deseret News. Merrill countered that the seminaries saved state money by shouldering part of the educational load and raising the standards of the students attending state high schools. He labeled part of Williamson’s report an overreaction: “To one who knows the real situation, the question will arise, was not the writer of the report straining at a gnat and swallowing a camel? How, for example, does the existence of a seminary near any high school add one penny to the cost of transporting pupils to and from the high school? Every person who gets this transportation is a school student, and if the seminary did [not] exist not one penny could be saved in transportation.”[28]

Merrill countercharged Williamson’s claims of the financial burdens caused by the seminary, pointing out that the program saved the state thousands of dollars by employing teachers and providing for part of the cost of the credits required for graduation without charging for any of these services. Further, he cited a Church questionnaire, sent out fourteen months earlier, in which nearly every high school principal questioned cited the presence of a seminary as a benefit for their schools.

Merrill acknowledged that the report had raised some valid concerns and vowed, “Should any of these conditions be found to exist, they will be corrected.”[29] He attempted to explain why some of the discrepancies in the report existed. For example, in Panguitch, Utah, the seminary had been conducted in a high school classroom. This action, however, had come about as the result of a trade in which the school, lacking facilities, had been given permission to use a local Church recreation hall for some of its classes.

Merrill also pointed out that universities and colleges had allowed credit for biblical studies for years, and there was no reason why high schools could not offer credit as well. Answering the more serious question of scholastic deficiency in seminary students, Merrill said, “The impression widely prevails that the scholarship of seminary students is higher than those of non-seminary students. If this is the case, then what the report says about scholarship of high school students has no point whatever,” promising to investigate the charges, nonetheless. The Church stood firmly behind the laws and acted as a force to promote “sound morality, good citizenship, and high educational ideals and attainments.”[30]

Merrill was not the only one to respond to the report’s accusations. D. H. Christensen, a former superintendent of Salt Lake City schools, and a Church member, wrote a letter to the Deseret News questioning Williamson’s interpretation. He noted that the US Bureau of Education report quoted by Williamson also declared that Salt Lake City children attended 480 weeks of school during their twelve-year education, while students from rural districts, where seminary was offered, attended only 420. Therefore, any academic differences between the two groups were more likely to be a product of less school time rather than time spent in seminary. Christensen continued, “A high school student who spends 1/

Reforming the System

While publicly refuting the Williamson report, Merrill was taking steps behind the scenes to remedy some of the problems highlighted by the crisis. The minutes of the Church general board indicate that in a 5 February 1930 meeting, the board engaged in an extensive discussion concerning the report. In that meeting, Merrill proposed that Guy C. Wilson, a close associate, be moved to the BYU Theology Department. A month later, the reason for the move became evident when Merrill and Wilson both proposed that all seminary texts and outlines be rewritten. To help professionalize the system, Merrill asked for the establishment of a Department of Religious Education at BYU, with Wilson as the head.[32] Before this time, BYU’s Theology Department was not a part of any particular college. The entire theology faculty consisted of former BYU president George Brimhall.[33] Even before the Williamson report, Merrill had begun to see the need for a professional group of scholars to guide religious education in the Church. In May of the previous year, 1929, he had written President Harris, saying, “May I suggest that serious consideration be given to the problem of making a strong department of religion, or of religious education, whichever you care to call it.”[34] In Wilson, Merrill placed a capable lieutenant at BYU who began building a world-class association of Latter-day Saint scholars. Dr. Sidney Sperry, fresh from the PhD program at the University of Chicago, joined the faculty in 1932, and Russel Swensen, also trained at Chicago, arrived the next year.[35] Wilson himself had served as the first full-time teacher at the original seminary at Granite High School and as a principal at a number of LDS schools, and was a staunch supporter of the seminary system.[36] The crisis provided the sense of urgency Merrill needed, and so his requests were granted and Wilson was in place by the end of February.

The Crisis Deepens, March–April 1930

As Merrill was taking these steps to ensure the future of the seminary program, the situation went from bad to worse. The special committee appointed to review the matter issued a response even more condemnatory than Williamson’s. Their report also revealed that the state board was beginning to fracture along religious lines concerning the question. Only two members of the three-man committee agreed to sign the report. Judge Joshua Greenwood, a Latter-day Saint from Utah County, refused to sign, while George Eaton, assistant superintendent of Salt Lake City, and Clarence Robertson, an attorney from Moab, endorsed its contents.[37]

The report was a thirty-two-page bombshell in which the two men sustained every charge in the Williamson report and then went on to add their own legal concerns about released-time seminary. Included in the committee’s report were legal opinions from seven states and citations of several court cases against religious education in schools. Almost all of the report came across as an attack on the seminary program, with only one court decision cited that upheld credit for biblical studies. Based on these assumptions, the Eaton and Robertson report recommended the following actions: first, that seminaries completely disassociate from the high schools (referring mainly to the practice of the two sharing attendance records); second, that credit for religious instruction both at the high school and at any state universities be withdrawn; and third, that no students be excused during the school day to attend seminary classes or be allowed to work on seminary work during the school day.[38]

These provisions meant essentially the end of the released-time program and would have dealt a serious blow to the Church’s weekday religious-education program and the fledgling institute program. All of the work transitioning the educational system from the academies to the seminaries would be effectively wiped out in one stroke. Aware of how far-reaching the consequences of their recommendations could be, Robertson and Eaton moved to take no action until Merrill could appear before the state board to make his case. The action was seconded by Greenwood, who later explained his refusal to sign the report by saying that he didn’t want to incite public furor. “It must be admitted,” he argued, “that it is the LDS seminaries that are affected by the report. My idea was that Dr. Merrill might talk this matter over with the committee of three before the final action is taken.”[39] Following the report’s release, the state board invited Merrill to make a defense a month later. Unless he managed to turn the tide, it looked as if the Church would suffer a serious defeat.

As drastic as the second report made the situation seem, it suffered from many of the same defects as the Williamson report. Nearly all of the legal opinions cited related to the teaching of religion in public schools, something that released time was specifically designed to avoid, and it made the bold assumption that blame for Utah students’ academic woes could be laid at the feet of Church education. Nevertheless, the situation had grown darker. Released-time/

Recognizing how serious the situation was becoming, Merrill rallied the troops and launched a counterattack. At a meeting of Church educators held two weeks later, on 7 April, President Heber J. Grant; Milton Welling, Utah’s secretary of state and former stake president; and Milton Bennion, dean of the University of Utah’s School of Education and a member of the Church General Sunday School Board, each took turns hammering away at the state board’s actions. Grant stated, “Our fathers and mothers came to Utah and bore their trials and tribulations for the sole purpose of religious liberty,” and called for a public vote to determine the future of seminary. Welling issued an all-out call for the faithful to organize and fight the board’s decision: “If they [the seminaries] are lost it will be the fault of the people of the Church. If they will unite their efforts and follow their convictions, I do not think that the work of the opposition can be accomplished.”[40] Bennion first detailed the opposing arguments, then systematically attacked them, citing his correspondence with practitioners of released-time programs in five states. He went on to extol the benefits of character education, saying, “The government does not hesitate to call for the cooperation and assistance of the church in time of war or other national crisis. In time of peace the government might very well welcome the cooperation of the churches in every feasible way in promoting the character education of youth.”[41] Bennion sounded the most conciliatory note, expressing that it might be possible to reduce the number of hours of released time, but overall the conference was a call to war. The report of the conference in the Deseret News carried the subheading “Pres. Grant Calls On Saints to Defend Rights.”[42] The Church had made its position clear. Depending on the board’s next move, a drawn-out public battle could be looming.

Before the State Board, May 1930

A month later, Merrill was given the chance to present the Church position before the state board. The moment was crucial. Merrill presented a twenty-four-page document addressing the claims of Williamson’s report on 3 May 1930. While this written reply is likely the work of many in the Church Department of Education, it bears Merrill’s signature and repeats many of the arguments he had already made in favor of seminary. Robert L. Judd, a local attorney, appeared with Merrill to present the Church’s stance on the legal issues surrounding the case.[43]

Merrill began by addressing the charge that seminary was a cause of deficient scholarship among high school students. Securing data from the fifty-two high schools where seminaries were adjacently located, he reported that in 1928, out of a total of 2,017 students, 1,019, or 55 percent, were also seminary graduates. The seminary graduates had an average scholarship grade of 83.3 compared to their non-seminary counterparts, who had an average grade of 81. The figures from 1929 reflected roughly the same conclusion, with an average grade of 83.6 among seminary graduates and an average of 81.6 among nongraduates.[44]

Addressing Williamson’s charge that seminary attendance affected college performance, Merrill cited statistics from BYU, where seminary graduates had an average grade of 75.6, whereas nonseminary students had an average grade of 71.3. At the Utah State Agricultural College, seminary graduates earned an average grade of 81.42; nonseminary graduates earned an average grade of 79.36. The University of Utah had declined to provide statistics. Merrill acknowledged the extra work required of seminary students but asserted that there was “no excellence without labor” and “no royal road to learning.” If students were failing to excel, it was more likely the result of too little study rather than the fault of the seminary.[45]

Answering concerns that seminary studies prevented students from graduating, thereby costing the state more money, Merrill reported that in Utah in 1928 only one student’s failure to graduate from high school was linked to his seminary studies. In 1929 three students gave seminary as their reason for not graduating. Having begun to establish his case, Merrill now leveled an accusation at the state inspector: “Can there be any justification for a school official making grave charges against an institution without having facts to substantiate his charges?”[46]

Merrill further responded by citing questionnaires sent from the Church Office of Education to superintendents of school districts where seminaries operated. The letters asked two questions: “1) Are the LDS seminaries in your district a financial burden to the public-school funds? That is, if they should cease to exist would the expense of operating your high schools be increased, diminished, or not affected? 2) Is the influence of the seminary helpful or hurtful to the high school and the students? That is, does it handicap or otherwise [impair] high school discipline, efficiency or morale?”[47] All but two principals reported that seminaries had a positive influence on discipline, efficiency, and morale, with the remaining two saying they had no evidence either way. Though the reports were issued with promised anonymity, several superintendents volunteered to make their names public and provide statements supporting the seminaries.[48]

When it came to the expense needed to transport students to schools, and therefore to adjacent seminaries, Merrill responded even more cuttingly. He pointed out the absurdity of this charge: “As to bus transportation, we admit frankly that the seminary is benefited by the transportation system of the high school. So is the corner grocery, the refreshment stand, the shop, the business house, and the town as a whole in which the high school is located. It could not be otherwise. But within the meaning of the law no sane person would assert that because these places are benefited by the presence of the high school in the community they are therefore supported, in part, in any legal sense whatsoever, by the money of the taxpayers.”[49]

Merrill continued, observing that instead of costing the state money, the Church had been shouldering a significant amount of the work of providing the state with education. He cited schools such as LDS College, Dixie College, and the other junior colleges under Church control as institutions that were saving state funds by providing education for the young. There is perhaps an air of irony in Merrill making these statements while he was simultaneously working to pass these assets on to the state, but the fact remained that the Church had borne a great portion of the educational burden of the state for the better part of its history.

Merrill must have known that Williamson’s most serious charges were related to the seminary program’s alleged violations of church and state. Recognizing this, Merrill saved his strongest arguments for this issue. Comparing seminaries to private schools, he asserted, “It is the practice of the public schools of America to give credit on transfer from private schools; and further, the public schools accept credit on transfer from reputable private schools for subjects that they themselves do not teach. This is common practice in America.”[50]

Merrill readily admitted that the Utah Constitution prohibited the use of public funds for religious purposes, but he also acknowledged that liberal interpretations of the provision abounded. For example, the Utah Legislature paid its chaplains’ salaries, the State Senate opened with prayer, chaplains were allowed to pray in the United States Army and Navy, and so forth. Merrill asked, “Does this violate the Constitution? Literally, yes, a layman might say; in spirit, no, we believe every court would interpret it.”[51]

Merrill pointed out that the virtues of the seminary system even received praise from the US commissioner of education: “On a visit to Utah, when he was United States Commissioner of Education, Hon. J. J. Tigert said to Mr. Robert D. Young, who at the time was a member of the State Board of Education, that he had made some study of the LDS seminary system in cooperation with public high schools and thought it one of the finest arrangements in the land. He said he believed this method of religious character training would, in the near future, be adopted by the whole United States.”[52]

Merrill explained to the board how the first seminary at Granite High School had received unanimous approval from the local school authorities, including the superintendent of public instruction. In addition, the state had passed a law on 5 January 1916 allowing credit for Bible study. He candidly admitted that the Williamson report was correct in some particulars and explained action the board was taking to correct these faults: “It may be that the teaching of the Bible has not always been free from sectarianism. But the office of the LDS Department of Education has urged that the teaching be non-sectarian. We are quite sure that departures from this kind of teaching have not been frequent or general, even though the Inspector infers to the contrary.” But he also turned the charge of questionable practices back on Williamson himself, declaring, “The inspector did not speak personally to any high school or seminary principals about the problem before submitting his report. Why were all those involved not consulted before charges were made? In the past the Church Department of Education had asked the inspector to contact them if he found anything questionable in their practices.”[53]

Merrill openly asked the board whether the report was motivated by religious intolerance. Was it an attack on the legality of released-time religious education or the cultural dominance of the Church in Utah? Such suggestions may have been uncomfortable for the state board, but it was impossible to ignore this figurative elephant in the room. He argued, “The adoption of the committee’s suggestions means the death of the seminary, and the enemies of the seminary all know it. But why do they want to kill something that every high school principal and school superintendent of experience says is good, being one of the most effective agencies in character training and good citizenship that influences the students? Is religious prejudice trying to mask in legal sheep’s clothing for the purpose of stabbing the seminary, this agency that has had such a wonderful influence in bringing a united support to the public schools?”[54]

In concluding with such incendiary language, Merrill sent a clear message to the board about his intentions. He was not going to let their resolutions pass without a fight. Following Merrill’s remarks, Judd, the attorney who attended the meeting with Merrill, rose and stated that the abuses represented in the Williamson report did not answer the real question—whether released time was unconstitutional or not. He then added that if the board was not opposed, he was authorized to say that the Church would be willing to have the question tested in the courts. Challenged in court, the Church held a good chance of winning.

Merrill even upped the ante by presenting the board with a deadline, informing board members that he needed to know “at once” whether any action would be taken to interfere with the operation of the seminaries during the coming school year. Put under pressure, the board agreed not to take any action that would immediately affect the status of the seminaries. C. N. Jensen, the state superintendent of education and the board chairman, immediately occupied a mediatory position and moved to soothe both sides. Jensen declared that he had read every legal ruling he could find relating to the matter since the Williamson report was issued and was in consultation with several attorneys. He believed the question was “not economic nor scholastic, nor a moral question calling for determination as to whether the seminaries were good or bad, but that it was a legal question.” He motioned to send the question back to the three-man committee so they could confer with the state attorney general. The motion carried unanimously. Williamson, who was present at the meeting, was offered a chance at rebuttal but deferred until he could fully read Merrill’s reply and formulate a response.[55]

Merrill’s actions gave the seminaries a temporary reprieve, but the question was far from settled. Still, his presentation stopped the state board from taking further action—a positive development after months of setbacks. Franklin Harris wrote Merrill to compliment his actions: “It seems to me you have hit them with a solar plexus blow, and I do not see that they have a come-back.”[56] Merrill himself remained less sure of the outcome. At a meeting of the Church board a few days later, board members engaged in a lengthy discussion on the state board’s actions. Merrill expressed his hopes that the matter was settled, and no further action would be taken. At the very least, he assured the board, seminary was safe for another year.[57]

Attack and Counterattack, Summer 1930

Meanwhile, the question still lingered with the members of the state board. In a meeting held on 28 June 1930, C. A. Robertson presented a plan for settling the question in court. In the negotiations following Merrill’s appearance before the board, Judd and the Church attorneys had apparently agreed not to bring to bear any legal attacks if credit was eliminated by the board, considering it the board’s right to extend or withdraw credit. As a compromise, both parties had agreed to find a taxpayer to bring to a “friendly lawsuit” to answer the questions arising out of the Williamson report.[58]

At this same meeting, Williamson appeared before the state board. Presenting another lengthy report, Williamson reiterated his points from the original report and attempted to rebut Merrill’s arguments. Williamson backed off on economic questions but still objected to the seminaries in principle, passionately arguing, “The existing relationship between the public schools and the seminaries is fundamentally wrong. Even if it saved the State millions of dollars and did not cost a cent, it would still be wrong.”[59]

Merrill, who was not present at the state board meeting, soon caught wind of Williamson’s renewed attacks. In a 2 July meeting of the Church board, he reported on Williamson’s response and expressed his own opinion that Williamson had been “rather misleading,” but he also stressed the seriousness of the situation.[60] Sensing Williamson’s tenacity, Merrill again went on the offensive the next day. Meeting with a gathering of BYU students, he announced that the Church would “fight to the bitter end” to save its seminaries and that the controversy might eventually end up in the Supreme Court.[61]

While maintaining a hard line publicly, Merrill continued working to remedy the ills spotlighted by the Williamson report. The new texts Merrill had spoken of were ready for publication by August 1930, an astonishing turnaround time for any textbook. Ezra Dalby, the author of the new text for the Old Testament course of study, Land and Leaders of Israel, noted in his preface that “the text has been written under pressure of time and no doubt many imperfections will be noted.”[62] James R. Smith, author of the New Testament course of study, The Message of the New Testament, noted in his preface that “the text has been written, as requested, from a Christian point of view without regard to creed.”[63] The new texts also featured some notable changes from the former texts. The first lesson in the Old Testament manual was “Abraham, the First Pioneer,” leaving out the beginning of Genesis and, as a result, many of the teachings Williamson had focused on as examples of sectarian teaching. Also missing were such notable lessons as “Our Life before We Came to Earth” and “The Story of Enoch,” both of which had been present in earlier texts.[64] The New Testament manual began with “The Coming of John the Baptist” but left out chapters from earlier texts such as “Prophetic Testimonies of Christ’s Earthly Mission.”[65] The new texts featured no references to works by other Latter-day Saint authors, which had been abundant in the earlier texts.

The new texts were so innocuous when it came to Latter-day Saint doctrine that they raised concerns among some members of the Church board. In a meeting in December 1930, Joseph Fielding Smith, at the urging of President Grant, pointed out a number of items in the Old and New Testament texts that he felt were “very unsatisfactory and not in revealed harmony with revealed truth.” Smith plainly stated that he felt the texts were not suitable for use among the young people of the Church. Merrill responded that on the advice of the Church attorneys no dogma had been incorporated, and the authors had written with those instructions in mind. A hearty debate ensued, but in the end, no changes were made. Survival was the order of the day, and Merrill was willing to make a few sacrifices to ensure the continuance of the seminary system.[66]

The Tide Turns, November 1930–September 1931

While this flurry of changes occurred on Merrill’s side, an ambiguous silence prevailed from the state board. After Williamson’s second report in July, the state board met only sporadically, and no discussions occurred about the fate of the seminaries. Merrill learned privately that the state board’s attempt to find a private citizen willing to bring a suit against the seminary system had stalled. In a Church board meeting held in November 1930, Merrill reported that state superintendent Jensen and the Church attorneys had come to the opinion that local boards of education, rather than the state board, should be allowed to handle the question. Both Jensen and Joshua Greenwood had informed Merrill that no more would be heard on the matter.[67] This development weighed heavily in the Church’s favor. If control fell into the hands of the local boards, a complete ban on released time and cancellation of credit seemed highly unlikely given the large Latter-day Saint population in most areas of the state.

Emboldened by this information, Merrill continued to expand the seminary program. In a Church board meeting held 26 December 1930, Merrill pressed the issue of the closure of LDS College. The closing of the school had already been announced a year earlier,[68] but some members of the Church board hesitated to move forward with the fate of the seminaries still in question, especially in Salt Lake City. Merrill pressed that with the opening of the new South High School in the city, LDS College should be closed immediately so that its teachers could find employment at the new school. The main opponents of this view were Joseph Fielding Smith and David O. McKay, both expressing concern that only a small percentage of Latter-day Saint students in the schools could attend seminary. Merrill told the board that the students could still be reached if the Church board gave the move its backing. The debate was ended when President Grant intervened, drawing attention to the hard facts of the matter. He told the board that the question wasn’t “what we would like but what we can do. We can’t extend the seminaries unless we stop these schools.” Grant expressed his regret over the closing of the school and his desire to keep it open. He even went so far as say that “the influence and spirit of the Church school is something that can’t be had in another institution, in this city or elsewhere, but he could see no alternative.”[69] The weight of these remarks cannot be underestimated. It signaled what was effectively an acknowledgment that the era of the academies was over. The seminary crisis and the energies exerted to save the program effectively brought into focus where the Church’s resources were to be devoted. With Grant’s backing, the board voted unanimously to close the school and lay the fate of the students in the hands of the seminary system.

When LDS College closed at the end of the 1931 school year, the seminaries expanded in the Salt Lake area to provide for the influx of Latter-day Saint students attending public high schools. However, since released time was still restricted in Salt Lake City, the announcement of this move served to prod the state board to finally announce its position. The announcement read, “It is necessary that the seminary classes will be held at the hours specified (before and after school), since Salt Lake City schools do not follow the precedent of the other schools in the state and the nation in giving released time during the school hours for this type of study.”[70]

While circumstances seemed to be moving in favor of the seminaries, Williamson prepared a third attack on the system, submitting still another report in July 1931. He tacitly acknowledged the telling effect of Merrill’s counteroffensive on the situation, writing, “The Church Commissioner of Education, through his two articles in the public press, through mimeographed and printed material sent to local school boards, through public addresses, and through instructions to local church officials, has interpreted the seminary movement in a way which obscures the vital principles involved, and which tends to stimulate a crusade for the further extension of the seminary system, with the perpetuation of its unconstitutional relationship to the public schools.”[71] Williamson’s tone in the report is one of frustration, and he exerts some very direct charges of coercion at Merrill and his associates. Williamson claimed, “Instances have been reported where Church [leaders] have brought irresistible pressure to bear upon high school principals to stimulate greater enthusiasm among the students of the high school,” but he offered no specific cases. He also charged that “in the opinion of the Commissioner of Church schools there, evidently, is no limit to the amount of school time the Church may appropriate” and that “the taxpayer has not made sufficient study of the question to realize that the schools are utilizing only five sixths of the school time in legitimate school activities.”[72]

Williamson then proposed his own attempt at a compromise. He suggested that students attend no seminary during their first three years of high school, then sever their connection to the public schools to attend seminary full-time during their senior year. He noted, “This, of course, would make it necessary for the Church to pay for the students’ transportation during the fourth year, but, since this probably would not exceed $60,000 per year, it should not prove burdensome to the Church, and it would be a great relief to the taxpayer.”[73] With seminary enrollment at over thirteen thousand students at the time, Williamson was estimating that total transportation costs for each student for an entire school year would total just over eighteen dollars, an optimistic estimate by any standard, not considering the other costs that would be incurred.[74]

A new report was submitted by the three-person investigative committee, which again split, with Joshua Greenwood dissenting. This time, the two remaining committee members, C. A. Robertson and George Eaton, seemed to acknowledge that they were fighting a losing battle. Hence, they moved to make a compromise. The demands of the committee were softened to request that “local boards gradually lessen the hours of seminary instruction.” While the complete elimination of released-time seminary was taken off the table, the committee remained firm in their request to disassociate the schools and seminaries in relation to attendance records, and insisted that no credit be offered for either seminary or institute studies.[75]

The final vote came in September 1931, with a verdict of six to three in favor of continuing the credit policy for seminary.[76] All six state board members who favored retention were Latter-day Saints, while the three dissenters—Robertson, Eaton, and Kate Williams—were not, a reflection of how divisive the issue had become in the community.[77] The victory, however, came with a cost. The state board ordered a complete disassociation of the seminaries from high schools in regard to physical plants, faculty records, and publications. Local boards of education were ordered to limit the time given to seminary instruction to no more than three hours a week during regular high school hours.[78]

What had changed from a year earlier, when it seemed that credit, released time, and the entire seminary system was in jeopardy? Merrill may not have realized it at the time, but the turning point was most likely when the state board promised they would not take action for the current year. Time was on the side of the seminaries. As the depression deepened and school finances worsened, the seminaries became more valuable to the schools. The most piercing arguments Merrill had made before the state board were about finances. The seminaries saved the schools a considerable amount of money. Asking the schools to increase their student, teaching, and classroom loads by one-sixth while they were struggling to keep their doors open at all was a price too heavy to pay. Williamson’s arguments about the financial strain the seminaries were placing on the system may have been too ethereal, and his proposed solution was entirely impractical. On the other hand, it was a concrete reality that the cancellation of released time would cost the schools money immediately.

Another factor pulling on the state board during this time is manifest in Merrill’s efforts to divest the Church of its remaining schools. Other than LDS College, which was closing outright, the rest of the Church schools were being transferred to state control. In the intervening months between Merrill’s defense and Williamson’s second report, the state board did not discuss the seminary issue in its meetings, but it did discuss the management of its new system of junior colleges.[79] The next time Merrill attended a meeting of the state board, he came not to discuss the fate of the seminaries but to work out details of the transfer of Weber College to state control.[80] During Merrill’s tenure, Weber and Snow colleges were transferred to state control, and negotiation began to transfer Dixie College.[81] It is not unreasonable to conclude that part of the reason why the state board was so generous in its ruling was that they did not want to upset this delicate process, which still had its critics inside and outside the Church. It is possible that the sacrifice of the Church schools may have saved the seminary system, which in turn gave Merrill the justification he needed to save BYU and the remaining Church schools.

Skirmishes over the seminary issue continued in the ensuing decades. A year after the state board’s decision, Oscar Van Cott, a principal at Bryant Junior High School, gave an incendiary speech regarding seminaries at the annual convention of the Utah Educator’s Association. Van Cott minced no words, saying, “Church seminaries as they are currently functioning in conjunction with the public schools are an evil more subtle, farther reaching, more dangerous and unwise than the cigarette evil, the Church is encouraging and fostering a direct violation of the state constitution and statute in operating the seminaries, and school officials who allow the functioning of the seminaries are guilty of a crime.”[82] The Church responded with a Deseret News editorial repeating the basic arguments for the legality of seminary. The controversy eventually sputtered out, though it did serve to illustrate how heated some educators’ feelings were.

Called as an Apostle

As for the two main antagonists, Merrill and Williamson, the immediate future held divergent paths. Less than a week after the state board made its decision, Merrill was chosen to fill a vacancy in the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles left when Orson F. Whitney passed away. He still continued to serve in his capacity as Church commissioner of education, but he now occupied a place in one of the top governing councils of the Church.[83] Merrill saw the calling as an endorsement of the difficult work he was still engaged in. In his first major address as an Apostle, he said, “This honor that has come to me is very great, because the nomination that I have received expresses a confidence in me of what I have come to regard as the finest body of men that live.”[84] He also acknowledged the impact of his work as commissioner. Where he had been languishing in his final years at the U, the constant stress and combat of his work within the Church revitalized him. He told the conference, “I have often remarked that in the position I have been occupying since coming to the Church Office Building, nearly four years ago, I have experienced the greatest joys of my life.”[85]

In truth, having a cause to fight for brought new life to Merrill. He had always enjoyed being in the thick of politics, but his aspirations remained unsatiated by the setbacks he suffered at the University of Utah. Now he was in the midst of controversy, and he reveled in it. The battles surrounding the seminary allowed Merrill to leave his traditional role as a peacemaker and enter the fray as a full partisan. He led an aggressive fight against the forces arrayed against him and used the crisis as leverage to make some of the changes he felt were vital to the future of the Church system. The heat of the crisis marked the completion of the transition of Joseph F. Merrill from the world of academia to a full-fledged member of the Church hierarchy, as his call to the apostleship attested.

Merrill’s chief opponent, Isaac L. Williamson, who emerges so vividly from the minutes of the state board, vanishes almost completely from sight after the 1930 crisis. According to the Salt Lake City Directory for 1932, he left the state in 1931, after nineteen years in Utah public education. His motives for leaving can only be guessed at, but given the timing, it is likely related to the outcome of the whole affair.[86]

What was at stake in 1930? It is possible that the Church may have been able to carry on without the released-time system. It is also possible that BYU and the other Church schools may have been able to survive without Merrill’s arguments that they were necessary training centers for seminary and institute teachers. What can be determined is that Merrill’s tenure as commissioner of education, and particularly the battle waged in 1930 and 1931, were critical in the creation of the hybrid system of education that the Church uses today. The potentially fatal blows of the Williamson report, unfortunately striking at a time when the Church was financially reeling from the effects of the Great Depression, could have radically altered the course of Church education. Instead, those crucial months served as a crucible that united the two systems. Before the 1930 crisis, the Church schools and the seminaries and institutes were often seen as a one-or-the-other proposition. Perhaps Merrill’s greatest accomplishment was the formation of a centaur-like system, with the Church schools as the head and the seminaries and institutes the body. Joseph F. Merrill’s decisive and vigorous action allowed both systems, one in its infancy and the other teetering on the brink of dissolution, to continue, grow, and prosper, despite the difficult conditions of the times.

Notes

[1] Primary sources for this study were drawn mainly from the Joseph F. Merrill Papers (MSS 1540) and the Franklin S. Harris Brigham Young University President’s Records (UA 1089) located in L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University. Both collections have been made available for public use in the last few years and contain a rich amount of material dealing with early twentieth-century topics. A vital resource for this study was also the records of the state board from this period, kept at the Utah State Office of Education. My thanks to Twila Affleck at the Utah State Office of Education for her generous help obtaining and copying these records. Other important materials were found in the Frederick Buchanan Papers at the University of Utah. In addition to these sources, the records of the BYU Centennial Committee (UA 566) at BYU and William E. Berrett’s CES History Resource Files, 1899–1985 (CR 102 174) at the Church History Library in Salt Lake City were immensely helpful. Other materials were taken from the Journal History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; Kenneth G. Bell,: “Adam S. Bennion LDS Superintendent of Education, 1919–1928” (master’s thesis, BYU, 1969); and Scott C. Esplin, “Education in Transition: Church and State Relationships in Utah Education, 1888–1933” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 2006).

[2] James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 504–5.

[3] Though most of LDS College was closed at this time, the business school was allowed to stay open. It was later renamed LDS Business College and continued to operate in the heart of downtown Salt Lake City. In September 2020 the school was renamed Ensign College. See Lynn M. Hilton, The History of LDS Business College and Its Parent Institutions, 1886–1993 (Salt Lake City: LDS Business College, 1995), “LDS Business College Announces Name Change and Other Significant Adjustments,” https://

[4] Lowry Nelson to Franklin S. Harris, 8 March 1929, UA 566, box 28, BYU Centennial Committee Records, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, BYU.

[5] David O. McKay, in Brigham Young University: The First One Hundred Years, ed. Ernest L. Wilkinson, 4 vols. (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1975), 2:73.

[6] Joseph F. Merrill, in Conference Report, April 1928, 37–39.

[7] 1920 US Census for Eureka, Juab County, Family History Library, Salt Lake City. For Williamson’s religious background, see Frederick S. Buchanan, “Masons and Mormons: Released-Time Politics in Salt Lake City, 1930–56,” Journal of Mormon History 19, no. 1 (1993): 77.

[8] William E. Berrett, A Miracle in Weekday Religious Education (Salt Lake City: Salt Lake Printing Center, 1988), 43.

[9] “Prof Adams Will Go to Park City,” Eureka Reporter, 31 May 1912.

[10] “Assignment of Tintic School District Teachers Completed,” Eureka Reporter, 10 September 1915.

[11] Minutes of the Utah State School Board, 27 November 1926. Copies in author’s possession.

[12] Minutes of the State Board, 21 December 1926. Copies in author’s possession.

[13] “LDS Seminary Will Soon Be Built,” Eureka Reporter, 26 December 1929, 1.

[14] “Seminaries of LDS Church Put Under Study by School Officials,” Salt Lake Tribune, 9 January 1930, 14–15.

[15] “Seminaries of LDS Church,” 14–15.

[16] “Seminaries of LDS Church,” 14–15.

[17] “Seminaries of LDS Church,” 14–15.

[18] “Seminaries of LDS Church,” 14–15.

[19] “Seminaries of LDS Church,” 14–15.

[20] “Inspector Hits LDS Seminaries,” Deseret News, 9 January 1930.

[21] Joseph F. Merrill to Franklin S. Harris, 2 May 1932, box 36, folder M, UA 1089, Franklin S. Harris Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, BYU.

[22] Joseph F. Merrill to T. N. Taylor, 21 February 1929, Harris Papers, BYU.

[23] Franklin S. Harris to John A. Widtsoe, 2 March 1929, Harris Papers, BYU.

[24] Merrill to Harris, 8 January 1930, Harris Papers, BYU.

[25] Franklin S. Harris to M. C. Merrill, 29 April 1929, Harris Papers, BYU.

[26] Joseph F. Merrill to George A. Brimhall, 3 July 1929, Harris Papers, BYU.

[27] Merrill to Harris, 25 February 1929, 7 May 1929, 8 June 1929, etc., Harris Papers, BYU. Setting up, strengthening, and ensuring a strong, professional Department of Religious Education was one of the major works of the Merrill administration. Of the remaining correspondence between Joseph F. Merrill and Franklin S. Harris, a large number of letters are related to this subject.

[28] “Head of System Answers Attack Upon Seminaries,” Deseret News, 9 January 1930, 1.

[29] “Head of System Answers Attack,” 1.

[30] “Head of System Answers Attack,” 1.

[31] D. H. Christensen, “Seminary Students Not Deficient in Scholarship,” Deseret News, 21 January 1930, 3.

[32] Minutes of the Church Board of Education, 5 February and 5 March 1930. Copies in the author’s possession.

[33] Wilkinson, Brigham Young University, 2:286.

[34] Merrill to Harris, 7 May 1929, Presidential Papers, cited in Wilkinson, Brigham Young University, 2:219.

[35] Wilkinson, Brigham Young University, 2:287.

[36] See T. Earl Pardoe, The Sons of Brigham (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Alumni Association, 1969), 223–24.

[37] “Probe Committee Splits on LDS Seminaries,” Deseret News, 24 March 1930; “Groups Splits on Seminary Work Probe,” Salt Lake Tribune, 24 March 1930. The author is indebted to Frederick Buchanan for the religious affiliations of the committee. See Buchanan, “Masons and Mormons,” 78.

[38] Minutes of the State Board, 24 March 1930, Utah State Board of Education Offices, Salt Lake City. Copies in author’s possession.

[39] “Group Splits on Seminary Probe.”

[40] “Church Leaders Protest Battle on Seminaries,” Deseret News, 7 April 1930.

[41] “Attitude of Educators Toward Religious Education,” Deseret News, 26 April 1930.

[42] “Church Leaders Protest Battle.”

[43] Minutes of the State Board, 4 May 1930.

[44] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, A Reply to Inspector Williamson’s Report to the State Board of Education on the Existing Relationship Between Seminaries and Public High Schools in the State of Utah and Comments Thereon by a Special Committee of the Board, issued as a letter to the Utah State Board of Education, 3 May 1930, box 57, folder 13, Buchanan Collection, AO149.xml, Special Collections, Marriott Library, University of Utah, 4 (hereafter referred to as the Merrill report). While it is likely several figures authored this report, it was sent under Merrill’s signature, and he should be considered, if not its sole creator, at least responsible for it. For the sake of clarity, and so as not to confuse this report with the Williamson report, I will refer to the words in this report as Merrill’s, knowing other unidentified Church officials may have also had a hand in writing them.

[45] Merrill report, 5–6.

[46] Merrill report, 8.

[47] Merrill report, 7.

[48] Merrill report.

[49] Merrill report, 9.

[50] Merrill report, 11.

[51] Merrill report.

[52] Merrill report, 19–20.

[53] Merrill report.

[54] Merrill report, 23–24.

[55] Minutes of the State Board, 4 May 1930.

[56] Franklin S. Harris to Joseph F. Merrill, 6 May 1930, Harris Papers, BYU.

[57] Minutes of the Church Board, 7 May 1930.

[58] Minutes of the State Board, 28 June 1930; “Status of Church Seminaries Seek Court Decision,” Deseret News, 28 June 1930.

[59] Minutes of the State Board, 28 June 1930.

[60] Minutes of the Church Board, 2 July 1930.

[61] “LDS Church to Wage Seminary Fight to Finish,” Salt Lake Telegram, 3 July 1930, 6.

[62] Ezra C. Dalby, Land and Leaders of Israel (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1930), ix.

[63] James R. Smith, The Message of the New Testament (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1930), vii.

[64] Outlines in Religious Education for Use in the Schools and Seminaries of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: Old Testament (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1928).

[65] Outlines in Religious Education.

[66] Minutes of the Church Board, 3 December 1930. It would seem that eventually Joseph Fielding Smith’s views prevailed in this particular case. Under the direction of the Church board, new texts for both the Old and New Testaments were published to replace the 1930 textbooks, both of which included discussions of the topics that had been deleted in their immediate predecessors. The new texts were published in 1937 and 1938 and enjoyed a much longer life in the seminary system than did the 1930 texts. See J. A. Washburn, Story of the Old Testament (Salt Lake City: Church Department of Education, 1937); and Obert C. Tanner, The New Testament Speaks (Salt Lake City: Church Department of Education, 1938).

[67] Minutes of the Church Board, 5 November 1930.

[68] “Closing of LDS College Explained,” Deseret News, 8 January 1930.

[69] Minutes of the Church Board, 26 December 1930.

[70] “Church Extends Programs at Three Seminaries in Salt Lake to Make Up for LDS College Closing,” Deseret News, 18 August 1931 (emphasis added). See also Buchanan, “Masons and Mormons,” 81.

[71] Minutes of the State Board, 27 June 1930.

[72] Minutes of the State Board, 27 June 1930.

[73] Minutes of the State Board, 27 June 1930.

[74] These figures were calculated by dividing the total number of seminary students at the time by four to account for only one grade. Seminary-enrollment statistics taken from Richard R. Lyman, “The Church in Action,” Improvement Era, June 1930, 533–37.

[75] Minutes of the State Board, 27 June 1931.

[76] “State Retains Credit Rating of Seminaries,” Salt Lake Tribune, 24 September 1931.

[77] Buchanan, “Masons and Mormons: Released-Time Politics in Salt Lake City, 1930–56,” Journal of Mormon History 19, no. 1 (1993): 80.

[78] “State Retains Credit Rating of Seminaries,” Salt Lake Tribune, 24 September 1931.

[79] Minutes of the State Board, 26 October 1931.

[80] Minutes of the State Board, 28 April 1933.

[81] See Richard W. Sadler, Weber State College: A Centennial History (Salt Lake City: Publisher’s Press, 1988); Albert C. Antrei and Allen P. Roberts, History of Sanpete County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1999); and Douglas D. Alder and Karl F. Brooks, History of Washington County: From Isolation to Destination (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1996).

[82] “Teacher Flays Seminaries at UEA Session,” Deseret News, 29 October 1932, 3.

[83] Merrill was another in a long line of Church educational commissioners who also served as Apostles, among them David O. McKay and John A. Widtsoe and, more recently, Neal A. Maxwell, Jeffrey R. Holland, and Henry B. Eyring.

[84] Joseph F. Merrill, in Conference Report, October 1931, 35.

[85] Joseph F. Merrill, in Conference Report, October 1931, 36.

[86] See Buchanan, “Masons and Mormons,” 77.