A Challenging Opportunity

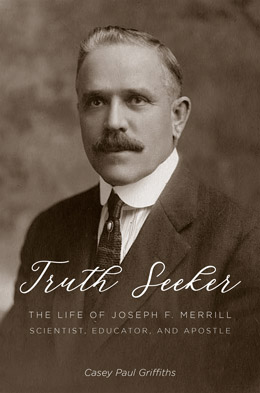

Casey Paul Griffiths, “A Challenging Opportunity,” in Truth Seeker: The Life of Joseph F. Merrill, Scientist, Educator, and Apostle (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 253‒76.

After five stressful years as the Church commissioner of education, Joseph F. Merrill left Utah to pursue an even more challenging calling as president of the European Mission of the Church. It was Merrill’s first long-term sojourn outside Utah since his graduate school days. Leaving the mountain home of the Latter-day Saints was undoubtedly a cultural shock for Joseph and particularly for Millie, who accompanied him during his three-year term. Joseph and Millie left the American West, where the religion of the Latter-day Saints was a well-established institution, and entered a new world where the Saints were an unknown, misunderstood, and largely feared sect.[1]

Leaving Home

The European Mission was long considered the classic proving ground for Latter-day Saint leaders. Just over a century before, nearly the entire Quorum of the Twelve Apostles had embarked for the shores of Europe in a quest to bring in new converts to the faith. Merrill’s immediate predecessors included such well-known Church leaders as David O. McKay, James E. Talmage, and even Church President Heber J. Grant, who occupied the post from 1904 to 1906. His immediate predecessor was John A. Widtsoe, his old compatriot from the University of Utah.[2] The assignment as head of the European Mission made him the presiding Church authority for all of Europe, and his stewardship covered smaller missions in Czechoslovakia, Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland.[3]

Before his departure, Merrill received a blessing from the First Presidency encouraging him to have “joy and satisfaction and happiness in [his] labors in presiding over the European Mission,” which they called “one of the greatest missions of the Church.”[4] Since Merrill’s wife, Millie, was traveling along with him, she too received a blessing that counseled her to “go with [her] husband, to be with him, and act with him, and be a helpmate to him.”[5]

Merrill departed for Europe with less missionary experience than most of his apostolic colleagues. Other than a call to serve as an “educational missionary” with his first wife during the last year of his graduate education in Baltimore, he had not previously been involved in full-time missionary service.[6] As a young married man, he had expressed willingness to serve as a missionary, but he never received a formal mission call. Though he was well traveled throughout the United States, he privately confided to a colleague, “I have never crossed the Atlantic.”[7] Still, he met the challenge with enthusiasm, introducing himself to the missionaries in his charge by writing, “You are Christ’s ambassadors, commissioned to act for and in His name. Knowing this, you are determined to make good! Nothing insurmountable stands between you and success.”[8]

Millie, on the other hand, met the new assignment with considerably more anxiety than her husband. Joseph was a lifelong Church adherent and a popular public speaker in Utah. Millie was a convert to the Church and, by most accounts, shy and introverted.[9] She confided to one of her stepdaughters, “I have to speak at different meetings every Sunday. At first I felt very shaky [and didn’t] remember much of what I said, the first time, but I am learning.”[10] Often called the “mission mother,” the wives of mission presidents served as maternal surrogates for the young missionaries serving far from home and were expected to entertain and feed anyone who visited the mission office.[11] Millie was overwhelmed during her first Thanksgiving in England, in which she was expected to cook for twenty-five guests, and later made some mild complaints about the “locust elders” who completely cleaned out her stores.[12]

Millie filled her days cleaning the mission office, sorting and answering mail, and feeding the constant stream of young elders who passed through the mission offices on their way to and from assignments. She was more familiar with Europe than her husband was and was also fluent in German. Seven years prior, she had spent three months visiting relatives in Germany.[13] She performed all of her tasks diligently, even writing a few articles for the Church newspaper, the Millennial Star, though she never became comfortable as a public preacher. “The worst of all my jobs is the preaching job,” she wrote in a letter home, and in another she proclaimed, “Preaching is still the bane of my existence.”[14] But she also never gave up on trying to develop the kind of comfort with public speaking she so earnestly desired. Her earnestness cries out from her letters home: “I have listened to so many talks at home that made me wish I had stayed at home. When I get up I do not want to talk, but I do want to say something.”[15]

Joseph expressed little anxiety over himself, but he worried about his children at home, particularly his youngest daughter, Laura, who was entering the university when he embarked for Europe.[16] All the other children were grown and married by this point, and Laura, the namesake of his first wife, received the lion’s share of his worry as he left the country. He provided pages of fatherly advice, telling her, “Don’t attempt too much. It is better to do a few things well than many things.”[17] He pleaded for her to overcome her shyness, telling her, “The art of making friends, of favorably impressing all we contact, of living agreeably with people, of making others love us should be learned as early as possible. It is the most important thing we can learn in school and college.”[18] The other Merrill children all protectively watched over Laura, and when Merrill received word of her falling behind in her studies, he was quick to invoke the memory of her departed mother, writing to her, “I want you to develop into a fine, charming, and sweet girl of whom Mama would be proud. You are her baby. How joyously glad we would all be made to see you develop into Mama’s pride!”[19]

The European Mission

Family worries aside, the state of the European Mission soon overtook all of Merrill’s other concerns. Missionary work in England, long fertile ground for Latter-day Saint converts, was at an all-time low. During the glory years of the mid-nineteenth century, thousands accepted the message of the new American missionaries. In 1849, for example, 8,620 converts joined the Church. In 1932, the year before the Merrills’ arrival, 267 converts were baptized.[20] The writings of anti-Mormon polemicist Winifred Graham produced a fair amount of paranoia regarding the motives of Latter-day Saint elders in England in the decade just before Merrill’s arrival. Graham’s writings so exasperated one of Merrill’s predecessors, David O. McKay, that he called her a “co-partner” with the devil and half-jokingly implored the Lord to “take her in hand soon!”[21]

President and Sister Merrill (center, seated furthest left) with a group of elders from the British Mission. Future Church President Gordon B. Hinckley is standing third from left. Courtesy of Church History Library.

President and Sister Merrill (center, seated furthest left) with a group of elders from the British Mission. Future Church President Gordon B. Hinckley is standing third from left. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The ravages of the Great Depression also decreased the number of missionaries serving in the British Mission to just forty-three elders.[22] Similar conditions existed in most of the other missions, with only a handful of elders serving. T. Edgar Lyon, called to the Netherlands Mission around the same time as Merrill’s call, presided over just nineteen missionaries.[23] Wallace Toronto, the president of the Czechoslovakian Mission, reported a conversion rate of 1.6 converts per elder per year.[24]

Merrill was optimistic but also a realist about the condition of the Church in Europe. Returning from a trip to the Continent, he wrote, “In one respect the work in Europe is progressing, but in another respect, I am sorry to say, we are losing. . . . Baptisms are still being performed, but they are all too few in number. I said we are losing; this means that members of the Church in considerable numbers are very indifferent, some of them requesting that their names be withdrawn from the records.” He reported that there was “no gain at all in the active membership of the Church over here” but also spoke of positive progress in “introduc[ing] local government in all these missions as rapidly as the saints will assume it.”[25] Millie was surprised by the state of the Church in London, writing, “In this city where the Gospel has been preached for almost a century and by messengers who were outstanding there are at present fewer than 500 members. . . . It does seem too bad to have to force such a good thing onto people who do not seem to want it, and who in many cases do not stay with the church after they join.” She also noted the generally irreligious nature of the Londoners around her: “The churches that we have visited were absolutely empty on Sunday mornings.” [26]

Trimming Expenses

The first problem Merrill tackled as the mission president was a lowering of expenses in the mission. He counseled the mission presidents serving under him to tighten their belts in any way they could. Merrill’s reputation for economy likely played a large role in his assignment to the mission. Merrill told T. Edgar Lyon that when Heber J. Grant issued the call, he instructed him, “President Merrill, you’re going out in the midst of an economic depression, and tithing funds are getting lower and lower every year. I want you to go over there and reduce the expenditures of the European Mission. I want you to do everything that you can to make things go as they should, and do it as cheaply as feasible, not as possible, as feasible.”[27] Millie reiterated this charge in one of her letters home, explaining, “We have to live as economically as possible. . . . We were sent here to bring down the cost of the missions and in order to teach economy we have to set an example.”[28]

Millie Merrill during her service in the European Mission of the Church. Courtesy of Annie Whitton.

Millie Merrill during her service in the European Mission of the Church. Courtesy of Annie Whitton.

Set an example they did. T. Edgar Lyon described some of the changes initiated by the Merrills after their arrival: “I remember the morning we landed in London in October on the way to Holland, Joseph F. Merrill had moved into an apartment above the mission home, the European Mission office. The Widtsoes had lived in the suburbs, out on an estate, and had a chauffeur that drove them back and forth. Merrill was going to save money. He would do it. He was going to travel on the subways and live in an apartment above the mission home which they had leased.”[29] The Merrills took up residence in a “three room flat on the fourth floor of the office building” where the mission offices were located.[30] The British Mission took up the first two floors of the building, the European Mission the third, and the Merrill residence the fourth.[31] There was no elevator in the building, and Millie wrote home complaining about the “62 steps” from the mission offices to their apartment.[32]

Merrill himself never stayed in a hotel. He bragged to Lyon, “I could come here to live in a tent in England, but that isn’t where I should be.”[33] Before his arrival, the expense of sending a missionary to Europe was exorbitant, and Merrill worked diligently to lower costs wherever he could. Following Merrill’s lead, Lyon launched a vigorous program to reduce expenses in the Netherlands Mission, eventually persuading his missionaries to curtail their spending by an average of almost 40 percent. At a conference of all the mission presidents, Merrill singled out Lyon’s missionaries for praise, leading the other mission presidents to launch similar programs. Lyon remembered, “President Merrill was a great man that way. He said, ‘You can do more with less if you plan.’ He was a great economizer.”[34]

Merrill’s economy became a growing part of his reputation, but he was also capable of largesse when it came to the poor, a steadily increasing population in 1930s London. One of the missionaries in the mission office later recalled, “Our London door carried a brass plaque reading, ‘European Mission.’ In England that had a ‘soup kitchen’ connotation, and the hungry and poor often rang the bell. They never went away emptyhanded, and most of what they received was drawn from President Merrill’s pocket.” The missionary also remembered “a disheveled young man who came coatless and penniless, and who left with a Merrill coat and pound note.”[35]

Exploring New Methods

Photo used in the Millennial Star to announce the arrival of Joseph F. Merrill as the president of the European Missions of the Church. Courtesy of Annie Whitton.

Photo used in the Millennial Star to announce the arrival of Joseph F. Merrill as the president of the European Missions of the Church. Courtesy of Annie Whitton.

Soon after his arrival in England, Merrill began to express frustration about the proselyting methods taught to the missionaries. He wrote frankly to an interested investigator, “Now it is true, I think, that our missionary methods are very inefficient. They are largely inherited. Seventy-five years ago they were very fruitful. But conditions have changed and I think we have not changed our methods to keep up with the changing times.”[36] In a meeting with the mission presidents in his charge, Merrill stressed the importance of updated missionary approaches. He advocated the development of “new methods of contact and proselyting,” including the use of new media approaches. He suggested using “sound pictures with colors, stage plays, the press, fiction, and greater use of the radio.” Frank in his assessment, he told the other mission presidents, “Our message is for all the world. We cannot deliver it if we cannot reach the world. Hence such methods will have to be used as will reach the people. We are not reaching Europe today.” He counseled them to “be ever alert and ready to try new methods when old ones, as ordinary tracting, are fruitless.”[37]

No missionary better understood the challenges posed by these older methods than Merrill’s most famous protégé, Gordon B. Hinckley. Hinckley was the son of a well-known Church leader, Bryant S. Hinckley. Hinckley was a college graduate, a rarity among the missionaries, and exceptionally well spoken, but even he struggled with the antiquated approaches favored by his fellow missionaries. Almost immediately after Hinckley stepped off the train in England, his new companion announced his intention to hold a street meeting that night. Over Hinckley’s protests, his companion compelled him to go to the market square a few hours later, where both began to sing loudly. When a sufficient crowd gathered, both missionaries began to teach and testify. Hinckley later admitted, “I was terrified. . . . I stepped up onto that little stand, looked at that crowd of people and wondered what I was doing there. They were dreadfully poor and looked to have absolutely no interest in religion.”[38]

Hinckley’s experience went from bad to worse over the next few weeks as he suffered through health problems, difficult living conditions, and an unresponsive populace. Frustrated, he wrote home to his family, saying he was wasting his time and his father’s money. He received a terse reply from his father: “Forget yourself and go to work.”[39] Recommitting himself, Hinckley began to show progress and grew in enthusiasm for his assigned work. He even began to demonstrate a flair for writing. Only a month after his arrival, he published his first article in the local Church periodical, the Millennial Star, titled “A Missionary Holiday,” a brief description of the American missionaries’ celebration of the Fourth of July. In this early article, Hinckley also demonstrated an aptitude for public relations. Of the street meetings he later recalled with dread, he wrote, “On the previous evening several of the districts had jointly conducted a street meeting in Kendal. For two hours testimony and song rang out across the public square to the interest of onlookers and the joy of Elders.” He even offered a humorous twist on the cultural gap between the English and their American cousins, continuing, “Then baseball, the grand old American game. What a thrill to play it again! Of course, the English crowd did not comprehend our strange game completely, but they laughed and cheered. What else mattered?”[40]

After eight months in the mission field, Hinckley was transferred to the mission office to serve as Merrill’s assistant. On 5 March 1934, Merrill noted the arrival of “Elder Hinckley, son of Bryant S.” to the mission office.[41] The young missionary remained in the office for the remainder of his time in England. His later recollections provide the clearest picture of Merrill’s life in the mission field. “During the first few days of our acquaintance we regarded him as an austere man. In fact, we thought him severe,” Hinckley later wrote. Over the next few weeks, while the two worked in close quarters, Merrill eventually grew into an important father figure for Hinckley. Every morning Merrill led his missionaries in a regimen of prayer and scripture study and then oversaw their work throughout the day. “In some respects he was not easy to become acquainted with,” Hinckley recalled. “He had the aloofness and precise manner of a general. Smiles were infrequent those first few days, . . . [but] the ice melted, and we discovered in our president a remarkable warmth and depth.”[42]

Hinckley also provides the best description of Merrill’s thrifty lifestyle. “His life was almost Spartan. . . . Cold water for shaving was the invariable rule, although he never objected to our using hot. His meals were simple; a little meat, mostly grains, fruits and vegetables.” Hinckley’s reminiscences also detail some of Merrill’s daily exercise regimen: “Early in the morning we could hear him in the room above, ‘One, two, three, four!’ as he swung his arms in setting-up exercises.” Over the ensuing months the young elder saw his mission president in a number of different circumstances, some even allowing Merrill, an avowed workaholic, chances for leisure: “He loved life. . . . We stood beside him at Empire soccer matches. We sat together in the stands at Wimbledon when the world’s great won their tennis laurels. He cheered and laughed with the rest of us.”[43]

Merrill’s well-known reputation for thrift continued to grow during his time in the European Mission. “Impatient of waste, he suggested that we turn off the lights when we left the room,” Hinckley reminisced. “He reminded us that the bills of the mission were paid from the consecration of the people.” Serving in part as a financial clerk, Hinckley observed Merrill’s strictness in financial matters: “When he traveled on expense accounts, there was no entertainment. Statements were submitted to the penny.”[44]

The young missionaries in the mission office came to know Merrill in a way few ever did, but there was still a distance and reserve to him. “Invariably of any evening he walked a mile or so along the gas-lit streets, oblivious to fog or rain,” Hinckley also recalled.[45] Merrill’s journals, filled with appointments, travel, and other duties, attest to the hectic nature of his life in the European Mission. But they also reveal traces of a lingering melancholy, despite his accomplishments. During one spell of discouragement, he recorded, “This is the 37th anniversary of my first marriage. I confess I place the intervening 37 years with regrets. . . . Am I wiser? Will I profit from my mistakes? Then [I] was hopeful and happy, now no new ventures in prospect.”[46]

Changing Methods

Occasional bouts with depression are understandable for a person under as much stress as Merrill was during this time. He felt a personal calling to improve the Church’s poor public image in Europe. In one of his first editorials for the Millennial Star, he wrote, “There was a time when the character of the ‘Mormon’ people was not well known, that false and malicious stories charging them with disobedience and disloyalty to civil authority were told and generally believed. But enemies of the message of ‘Mormonism’ can no longer find success with tales of that kind.”[47] It was difficult to satiate the British populace’s appetite for sensational material. Merrill lamented, “The truth is that the Church is perfectly willing for any writer to paint a picture of Mormon history. All the Church asks is (and does it not have a right to ask it) that the picture shall be true to the facts.”[48] When a local writer, C. Harcourt Robertson, approached the mission office about writing a series of articles on the history of the Church, Merrill enthusiastically agreed, loaning him a stack of books from the mission library. Robertson produced a series of articles. “We proofread his articles, advising him all along that he should make a public appeal nearly as the stretched truth would permit,” Merrill later wrote. He continued, “Well, the Sunday paper was disappointed that the facts were not sensational. And so the paper did not print the articles. Recently Mr. Robertson came to the office and said a half dozen different publications in London had returned his stories.”[49]

Merrill did eventually generate some positive publicity for his cause through an article published in the London newspaper, the Sunday Dispatch.[50] Merrill was so delighted by the article that he wrote an editorial in the Millennial Star asking all the British Saints to read and share it, writing, “We hope that all readers of the Millennial Star will read the article. . . . They, too, will rejoice that the day has come in this country when a great newspaper will take pains to publish the truth about the Church and its doctrines.”[51]

Merrill looked everywhere for inspiration about how to increase his missionaries’ effectiveness. A few months after his arrival, he met with George W. Hancock, a nonmember acquaintance of fellow Apostle George Albert Smith. Hancock was a retired officer of Scotland Yard who traveled throughout the western United States giving lectures. Merrill was deeply impressed with Hancock’s presentations, which included large, beautifully illustrated slideshow scenes of the West, including Salt Lake City. After his meeting with Hancock, Merrill reflected, “I think he has done more in his lectures to break down prejudice in England against the Mormon people than any missionary we have had here for a number of years.”[52]

In his mission to improve the Church’s public image, Merrill placed an unusual amount of responsibility on Gordon B. Hinckley’s shoulders. When several local papers printed an old anti-Mormon book and touted it as an authentic history of the Latter-day Saints, Merrill called on Hinckley to confront the publisher. Overwhelmed, the young missionary boarded a train and soon arrived at the Fleet Street office of Skeffington & Son, Ltd., the publishers of the book in question. Informed by Skeffington’s secretary that no appointments were available, Hinckley stubbornly replied that he had come five thousand miles and would wait. Within an hour he was in front of Skeffington and began airing his grievances and asking for redress, saying, “I am sure that a high-minded individual such as yourself would not wish to do injury to a people who have already suffered so much for their religion.” Hinckley later remembered, “At first he was belligerent, then he began to soften. He concluded by promising to do something. Within an hour word went out to every book dealer in England to return the books to the publisher. At great expense he printed and tipped in the front of each volume a statement that the book was not to be considered as history, but only as fiction, and that no offense was intended against the respected Mormon people.”[53]

Incidents like this demonstrated Hinckley’s skill in public relations, and Merrill began to give even more responsibility to his young charge. During his time in the mission office, Hinckley published an article titled “The Early History of the Latter-day Saints” in the London Monthly Pictorial. Anxious to begin using new proselyting methods, Merrill directed Hinckley to write a series of presentations using black-and-white slides to illustrate the lectures. Hinckley prepared three presentations, one on the Book of Mormon, another depicting critical events in Church history, and a third highlighting the beauty and culture of Salt Lake City.[54] Thrilled by the results, Merrill told an acquaintance, “We have come to the conclusion that the lantern lecture for cottages and movie lectures for the larger halls would bring many more contacts than we have been able to make during the last twenty-five years.”[55]

Merrill presented the lectures to the presidents of the European Mission at a conference in Liege, Belgium, during the summer of 1935. He received an enthusiastic response, later telling Hinckley, “The feeling was unanimous at the Liege conference that this illustrated lecture project would be one of the best contact means now available.”[56] At the end of Hinckley’s two years of missionary service, Merrill initially asked him to stay an extra six months, then he reversed his request and asked him to travel back to Utah immediately. Merrill was discouraged about the lack of response from Church leaders regarding his need for new missionary materials. He hoped a personal presentation by the persuasive young missionary might convince the First Presidency to increase their efforts.[57]

Hinckley’s first few meetings with Church leaders were discouraging. Hinckley wrote back to Merrill, “The brethren are anxious to help, but they just haven’t quite our viewpoint on some of these things and Europe seems rather remote when there are so many things near at hand holding their attention,” adding forlornly, “I have come to learn that England is not the only place where things move slowly.”[58] After two weeks of repeated requests, Hinckley was granted a meeting with the First Presidency, at the time consisting of President Heber J. Grant and counselors J. Reuben Clark and David O. McKay. He reported back, “Brother McKay expressed himself as being heartily in favor of the thing,” but added, “The President was noncommittal.”[59] Jobless and without many prospects, Hinckley diligently continued to work on the presentations, but with just a lukewarm response to his recommendations, he also began looking for other work. He received a glowing letter of recommendation from Merrill, who commended his “ability as a writer of narratives” and lauded his young friend as “energetic and dependable.”[60]

The weeks wore on with no response from the First Presidency, and Hinckley became discouraged, writing to Merrill, “It’s just about taken the heart out of me to have to go pounding on the doors of busy men, one day after another, with no obvious success.”[61] After six weeks and no results, Hinckley dejectedly informed Merrill that he might need to “get busy at something with which to patch [his] missionary rags.”[62] Hinckley finally accepted an offer from John A. Widtsoe to take over the teaching of a difficult afternoon seminary class, a desperate move, he wrote, to “keep a little butter on [his] bread.”[63]

During this time Merrill was unable to exert any pressure to assist Hinckley. He was preoccupied with the increasing troubles of the Church in Germany. While Hinckley waited in Salt Lake City, Merrill managed the government expulsion of four missionaries from their assigned areas in Germany. He did manage an encouraging note, telling Hinckley, “If nothing comes of it I release you from all responsibilities and obligation to continue your efforts. . . . No one could expect that you would do anything more.”[64] After nearly two months of waiting for a response from the First Presidency, Hinckley was finally contacted. Church leaders hired him to work as a writer on the Church publicity committee. With the hope to “be given a desk in some corner with a typewriter,” Hinckley went to work as the first employed publicity professional of the Church.[65]

Merrill was “filled with delight” when he heard of Hinckley’s hire and immediately requested a new lecture focusing on the Word of Wisdom. He wrote to Hinckley, “So popular are film lectures with our missions here that unless the brethren at home put a break on us you have just begun on a developing industry that will provide us with one of the most successful tools in our proselyting work.”[66]

Darkening Clouds over Europe

Gordon B. Hinckley’s successful expedition to Church headquarters was a rare bright spot in the darkening skies of the European Mission. Merrill’s mention of the expulsion of several missionaries in Germany was just one of an increasing number of disturbing incidents as Europe moved down the road toward another world war. Adolf Hitler had ascended to power in Germany the year before Merrill’s arrival, and the threat of the growing influence of the Nazis cast a dark hue over missionary efforts on the Continent. A concerned acquaintance wrote to Merrill, “The Mormon Church in Germany cannot hope to defy Hitler.”[67] Merrill himself wrote home in 1936, “At the moment Europe is passing through the darkest period of its existence since the war. The situation is extremely grave.”[68] In the Millennial Star, he wrote, “These are critical times—crisis after crisis follows one after the other in rapid succession. What does it all mean? At least one thing is certain—fear is the characteristic quality of our times.”[69]

Incidents on the Continent increased Merrill’s fear for the young missionaries in his charge. In August 1936, Czechoslovakian police arrested three missionaries on a bicycle trip for carrying cameras. The naive young elders were taking pictures in an area in which military maneuvers were taking place. Police confiscated their cameras but allowed the young men to go free. The incident prompted Wallace Toronto, the mission president in Prague, to write Merrill asking whether “it is advisable to forbid the use of cameras at all during these uncertain times and in these war frenzied countries.” He continued, “The devil himself seems to be taking advantage of every opportunity to destroy our work.”[70] Merrill counseled him, “The safe way is for the elders to leave their cameras at home. . . . Let us profit by our experiences.”[71]

Merrill struggled to work within the tightening confines of the Nazi system. A minor controversy occurred when a photograph appeared in the Church News of Merrill speaking at a Church conference in Germany with a Nazi flag in the background.[72] Merrill encouraged the mission presidents and missionaries in his charge to “be careful to establish the right relations between traveling Elders and local officers.”[73] He tried to set the example himself, even sending a telegram to the Fuhrer reporting on a mission conference held in Germany.[74]

With the specter of war overshadowing the work, Merrill also labored to ensure that local members could continue the work if evacuation of the missionaries became necessary. Merrill continued a program his predecessor, John A. Widtsoe, had instituted to gradually replace missionaries serving as branch presidents with local members. Missionaries received direction to call local men as counselors in their branches, and the men moved up the hierarchy as missionaries cycled out.[75] “We are trying to build all our branches into stable and permanent units of the Church and to introduce local government in all these missions as rapidly as the saints will assume it,” he wrote in a letter home.[76] It was an uphill battle. “The members of the Church in considerable numbers are very indifferent,” he wrote. “Some of them are requesting that their names be withdrawn from the records. And so, there is perhaps no gain at all in the active membership of the Church.”[77] Despite discouraging conditions, Merrill labored to build a permanent foundation for the faith in Europe, emphasizing the creation of a generational Church. Writing to Church members, he promised, “The Church is not here for a day only. It will be in Britain when the present generation has passed on. Perhaps the best way to insure this is by proper training of the youth.”[78] He also stressed the importance of adapting to each local culture, rather than touting the superiority of American culture. Instructing his mission presidents on mission publications, he said, “Do not publish sermons that reflect American conditions or that cast reflections on the lives that the Church members in America are leading. . . . They should represent the mission—i.e., be more local in character.”[79]

The World Congress of Faiths

As Merrill sought to allow the national communities of Latter-day Saints to become more distinctive, he also sought to raise the profile of the faith in a way that would transcend national boundaries. A fitting capstone for Merrill’s work in the European Mission was his participation in the World Congress of Faiths held in London in July 1936. For a small and largely misunderstood new sect of Christianity, such as the Latter-day Saint faith was at the time, the opportunity to be represented at such a venue was a signal honor for Merrill and a chance to bring wider awareness and respectability to the Church.

The World Congress of Faiths was the brainchild of Francis Younghusband, a British adventurer with a long and varied career in a number of military interventions on behalf of the Crown. One source described him as “the last great imperial adventurer.”[80] Younghusband was a Christian, but as a young man he had become obsessed with finding harmony among different religious traditions. For the conference he gathered together an eclectic mixture of scholars and faith leaders from throughout the British Empire. Faiths represented included Hinduism, Zoroastrianism, Jainism, Sikhism, Confucianism, and both the Sunni and Shi‘ite branches of Islam. One London newspaper declared the conference was for “the Queer Religions of the Empire” because there were no designated speakers for Judaism or Christianity, though Christian and Jewish scholars presented and participated in the discussions. Younghusband and the other conference organizers announced that the function of the conference was to “familiarize those attending the lectures with the religions of the Empire relatively little known in Britain.”[81]

The Church’s exotic reputation in Britain undoubtedly played a role in Merrill receiving an invitation to serve as the chair of one of the conference sessions. The Millennial Star proudly published Younghusband’s invitation to Merrill and declared it to be “indicative of the growing esteem for the Church throughout the religious world.”[82]

The program organizers allowed all speakers equal status on the platform and asked them not to introduce controversial religious or political topics. Merrill presided over a session titled “Economic Barriers to Peace.” The lead speaker, the Reverend P. T. R. Kirk, delivered a lengthy address criticizing the evils of nationalism, usury, and the race between nations to acquire armaments. When it was Merrill’s turn to speak, he declared, “The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, to which I belong, is probably unsurpassed by any other religious body in the world for its activity in teaching the Fatherhood of God and the Brotherhood of Man.” To illustrate this, he pointed toward the work of missionaries on six continents, who “return to their homes feeling that the people among whom they have lived and worked are the finest people on earth.” He continued, “In a very real sense, our Church is annually bringing back to North America, from all over the world, ‘Goodwill Ambassadors’” who would “never cease to love the people among whom they lived abroad.”[83]

Merrill briefly expounded on Latter-day Saint beliefs, stressing the Church’s tolerance for other religions and its strict belief in allowing other faiths to “worship God according to the dictates of their own conscience.” He concluded his speech by saying, “The Latter-day Saints extend to you the hand of friendship and brotherhood, and they pray that God will help you in the attainment of your every righteous desire, no matter in what country or clime you live, or what may be the colour of your skin.”[84]

Afterward, Merrill praised the conference in the Millennial Star, calling it “a great success” and sharing a hope “that from it would certainly issue a better understanding and more toleration of each other’s religious faith.” He was also aware of the conference’s shortcomings, noting, “It is likely that each member left the Congress as he entered it—with a feeling that his own religion was best.” But overall, he felt hopeful at the outcome, saying, “The fact that each one was apparently willing to tolerate whole-heartedly the religion of the other is proof of a vast growth in human fellowship during recent years.”[85] It was undoubtedly gratifying to him to represent The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints alongside some of the largest and most ancient faith traditions in the world.

Going Home

Only a few weeks after the close of the World Congress of Faiths, Richard R. Lyman was appointed to succeed Merrill as president of the European Mission. Merrill’s farewell editorial in the Star highlighted his frustrations with conditions in Europe and his love for the people. “Measured by what we have accomplished during the three years Sister Merrill and I have been in Europe, the time seems shorter still, so fruitless have our efforts seemed to be,” he wrote.[86] Despite Merrill’s dedicated efforts, Church growth in Europe remained tepid. The British Mission, for example, managed only 147 new converts in 1935 and only 206 in 1936.[87] The Church’s growth in the region remained slow until the postwar era, when conversions in the British Isles accelerated rapidly.[88] Merrill comforted himself by saying, “If desire and intent are also factors in the measurement of time we have no regrets.”[89]

It is unlikely any Latter-day Saint leader of the era would have produced better results in Europe than Joseph F. Merrill managed to from 1933 to 1936. He left Europe with the darkening skies of war approaching, aware of the precarious situation the local members of the Church faced. He praised the European members as “some of the most faithful Latter-day Saints it [had] ever been [their] pleasure to meet.” He also warned, “The lands of the European countries in themselves are good. Whether they are pleasant lands to their dwellers will depend on the righteousness of these dwellers—so the justice of God has always determined.”[90]

Merrill’s most valuable contribution to Latter-day Saint proselytizing came in the work of Gordon B. Hinckley, toiling away at his typewriter at Church headquarters. The path Merrill placed Hinckley on led to significant changes in missionary work. In the ensuing decades, innovative use of media became a hallmark of Latter-day Saint missionary efforts, with Hinckley spearheading Church efforts in radio, television, and other forms of media. After Hinckley became an Apostle in 1961, he continued to lead Church efforts in this area. By the time he became Church President in 1995, he was not only the senior Apostle but also the senior employee at Church headquarters, where he presided over a bustling number of international media ventures owned and operated by the Church. Hinckley’s presidency was a culmination of his many years working with the media and ushered in a new era of openness, with one scholar branding him the “standard bearer” in a new age of Latter-day Saint publicity.[91] In his lifetime, Joseph F. Merrill saw only the beginning of his religion transforming from what many saw as an obscure and backward sect to a well-respected and internationally known faith. But the seeds planted in his work with Gordon B. Hinckley and the other missionaries in the European Mission office are now in full bloom decades later.

Notes

[1] In preparing this chapter, I am indebted to the work of Rob Taber, who prepared an excellent article on the work of Joseph F. Merrill and Gordon B. Hinckley in the European Mission. See Rob Taber, “The Church Enters the Media Age: Joseph F. Merrill and Gordon B. Hinckley,” Journal of Mormon History 35, no. 4 (Fall 2009): 218–33.

[2] Richard L. Evans, A Century of “Mormonism” in Great Britain (repr., Salt Lake City: Publisher’s Press, 1984), 242.

[3] “Report of the Conference of the Presidents of the European Missions, Held at Berlin, Germany, 11–15 June 1935,” box 22, folder 1, Joseph F. Merrill Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University (BYU).

[4] “A Blessing Upon the Head of Elder Joseph F. Merrill by Presidents Heber J. Grant, Anthony W. Ivins, and J. Reuben Clark Jr., President Grant Being Voice, Setting Him Apart to Preside over the European Mission,” 25 August 1933, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[5] “A Blessing Upon the Head of Elder Joseph F. Merrill.”

[6] Journal History of the Church, 23 September 1898, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[7] Joseph F. Merrill to Roy A. Welker, 22 July 1933, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[8] Joseph F. Merrill to European Missionaries, 7 November 1933, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[9] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill and Annie Laura Hyde Merrill Published by His Children (Salt Lake City: privately published, 1979), 14.

[10] Emily T. Merrill to Edith and Richard Mollinet, 31 November 1933, 5, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[11] Merrill to Mollinets, 25 December 1933, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[12] Merrill to Mollinets, 31 November 1933, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[13] Joseph F. Merrill to Roy A. Welker, 22 July 1933, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[14] Merrill to Mollinets, 23 March 1934; and Merrill to Mollinets, undated letter, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[15] Merrill to Mollinets, 23 March 1934, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[16] Merrill to Welker, 22 July 1933, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[17] Joseph F. Merrill to Laura H. Merrill, 10 September 1933, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[18] Merrill to Merrill, 25 April 1934, Merrill Papers, BYU (emphasis in original).

[19] Merrill to Merrill, 22 August 1934, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[20] Evans, Century of “Mormonism,” 244.

[21] See Malcolm R. Thorp, “Winifred Graham and the Mormon Image in England,” Journal of Mormon History 6 (1979): 107–21.

[22] Evans, Century of “Mormonism,” 243.

[23] Thomas E. Lyon oral history, interview by Davis Bitton, 13 January 1975, James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, 109.

[24] “Report of the Conference of Presidents of the European Missions,” 17, see also Mary Jane Woodger, Mission President or Spy? The True Story of Wallace F. Toronto, the Czech Mission, and World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019).

[25] Joseph F. Merrill to Alonzo B. Merrill, 20 June 1934, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[26] Merrill to Mollinets, 31 November 1933, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[27] T. Edgar Lyon oral history, 1974–75, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, 108.

[28] Emily T. Merrill to Laura H. Merrill, undated letter, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[29] T. Edgar Lyon oral history, 101.

[30] Merrill to Mollinets, 18 November 1933, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[31] T. Edgar Lyon oral history, 109.

[32] Merrill to Mollinets, 31 November 1933, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[33] T. Edgar Lyon oral history, 108.

[34] T. Edgar Lyon oral history, 109.

[35] Gordon B. Hinckley, “Church Mourns the Passing of Elder Joseph F. Merrill,” Improvement Era, March 1952, 147.

[36] Joseph F. Merrill to C. R. Irving, 12 March 1935, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[37] “Report of the Conference of the Presidents of the European Missions,” 11–15 June 1936, box 22, folder 2, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[38] Quoted in Sheri Dew, Go Forward with Faith: The Biography of Gordon B. Hinckley (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996), 62.

[39] Dew, Go Forward with Faith, 64.

[40] Gordon B. Hinckley, “A Missionary Holiday,” Millennial Star, 27 July 1933, 494–95.

[41] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 5 March 1934, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[42] Hinckley, “Church Mourns,” 144–45.

[43] Hinckley, “Church Mourns,” 144, 147.

[44] Hinckley, “Church Mourns,” 144, 147.

[45] Hinckley, “Church Mourns,” 144.

[46] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 9 June 1935, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[47] Joseph F. Merrill, “The Message of the First Presidency,” Millennial Star, 11 January 1934, 24.

[48] Merrill to Irving, 18 April 1935, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[49] Merrill to Irving, 18 April 1935, Merrill Papers, BYU. A search for other works by C. Harcourt Robertson revealed only one other work, Burmese Vignettes, a brief, 152-page book published by W. Thacker in 1930.

[50] Ian Coster, “What Shall Man Believe?,” Sunday Dispatch, 1 February 1934.

[51] Joseph F. Merrill, “The ‘Sunday Dispatch’ Article,” Millennial Star, 22 February 1934, 120.

[52] Joseph F. Merrill to L. E. Cowles, 27 February 1934, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[53] Gordon B. Hinckley, in Conference Report, October 1971, 123; Dew, Go Forward with Faith, 73.

[54] Dew, Go Forward with Faith, 71–72.

[55] Joseph F. Merrill to James H. Douglas, 2 April 1935, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[56] Joseph F. Merrill to Gordon B. Hinckley, 23 August 1935, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[57] Dew, Go Forward with Faith, 77.

[58] Gordon B. Hinckley to Joseph F. Merrill, 7 August 1935, box 20, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[59] Hinckley to Merrill, 21 August 1935, box 20, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[60] Joseph F. Merrill letter of recommendation to Gordon B. Hinckley, 4 September 1935, box 20, folder 4, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[61] Hinckley to Merrill, 17 September 1935, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[62] Hinckley to Merrill, 19 September 1935, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[63] Hinckley to Merrill 17 September 1935, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[64] Merrill to Hinckley, 3 October 1935, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[65] Hinckley to Merrill, 3, 16 October 1935, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[66] Merrill to Hinckley, 30 October 1935, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[67] C. W. Irving to Joseph F. Merrill, 2 February 1935, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[68] Joseph F. Merrill to Mr. and Mrs. Richard S. Bennett, 12 March 1936, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[69] Joseph F. Merrill, “Armistice Day and Safety,” Millennial Star, 29 November 1934, 760–61.

[70] Wallace F. Toronto to Joseph F. Merrill, 15 September 1936, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[71] Joseph F. Merrill to Wallace F. Toronto, 18 September 1936, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[72] “Germany Holds MIA ‘Echo of Joy’ Festival,” Church News, 18 July 1936, 2.

[73] “Report of the Conference of the Presidents of the European Missions,” Merrill Papers, BYU, 17.

[74] “Report of the Conference of the Presidents of the European Missions,” Merrill Papers, BYU, 23.

[75] T. Edgar Lyon oral history, 122.

[76] Joseph F. Merrill to Alonzo B. Merrill, 20 June 1934, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[77] Merrill to Merrill, 20 June 1934, Merrill Papers, BYU.

[78] Joseph F. Merrill, “Concerning the Primary Association,” Millennial Star, 30 August 1934, 552.

[79] “Report of the Conference of the Presidents of the European Missions,” 23.

[80] Marcus Haybrooke, A Wider Vision: A History of the World Congress of Faiths, 1936–1996 (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 1996), http://

[81] Haybrooke, Wide Vision.

[82] Millennial Star, 23 April 1936, 260–62.

[83] Faiths and Fellowship, Being the Proceedings of the World Congress of Faiths held in London, July 3rd–17th, 1936, ed. A. Douglas Millard (London: J. M. Watkins, 1936), 337–38.

[84] Faiths and Fellowship, 338.

[85] Joseph F. Merrill, “The End of the Congress,” Millennial Star, 30 July 1936, 489.

[86] Joseph F. Merrill, “A Coming and a Going,” Millennial Star, 24 September 1936, 616.

[87] Evans, Century of “Mormonism,” 244.

[88] Richard O. Cowan, “The Church Comes of Age in Britain,” in Regional Studies in Church History: British Isles (Provo, UT: Department of Church History and Doctrine, 1990), 194–96.

[89] Merrill, “A Coming and a Going,” 616.

[90] Merrill, “A Coming and a Going,” 616.

[91] J. B. Haws, The Mormon Image in the American Mind: Fifty Years of Public Perception (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013). 159.