“Beyond the River of Death”

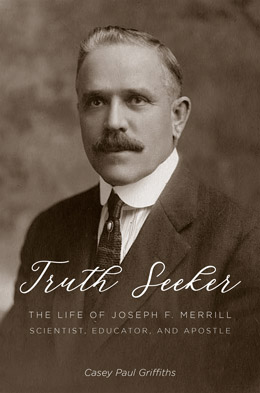

Casey Paul Griffiths, “'Beyond the River of Death,'” in Truth Seeker: The Life of Joseph F. Merrill, Scientist, Educator, and Apostle (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 303‒24.

The final year of Joseph F. Merrill’s life saw a mellowing and deepening of his faith in both religion and science. His faith in science was tested as he saw his beloved discipline used to create terrible weapons capable of destroying the greater part of humanity. His faith in his religion was also severely tested as he once again witnessed the death of one of the important women in his life. With growing adversity and a slow but constant decline in his health and vitality, the old warrior became less concerned with condemning sin and more focused on shepherding lost souls back into the fold. As the twilight of his life came upon him and his ability to control the world around him seemed to spin ever more out of control, his faith served as a fixed point in the growing chaos of the postwar world.

While Merrill was in the midst of recording his radio series, World War II came to a devastating conclusion. Merrill declared in one of his talks, “Another thing the science of this century has done is to reveal to us a world and a universe more extensive, more wonderful, and more mysterious than man ever imagined before—a universe too big, too minute, too marvelous for mortal minds to comprehend.”[1] The next day, the ominous potential of science was put on graphic display when the city of Hiroshima was obliterated during the first combat use of an atomic bomb. Merrill wrote carefully in his journal about the “sensational” news, noting in careful detail the announced explosive power of the bombs. When the second bomb fell on Nagasaki three days later, he again wrote a description in his journal, circled for emphasis and recording the action “practically destroying” another Japanese city.[2]

Joseph F. Merrill with Gordon B. Hinckley producing a Church film. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Joseph F. Merrill with Gordon B. Hinckley producing a Church film. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Merrill never commented on the morality of the bombings, but he did take note in his next broadcast of the promise and peril of this terrifying new power source. He interrupted his prepared text to comment, “Since the above was written came the announcement, August 6th, of the atomic bomb. So a beginning has been made in the release and control of the enormously great amount of atomic energy.” He cautiously told his audience, “How economically to unlock atomic energy for practical uses is a problem for the future. If it was satisfactorily solved there would be at hand a never-ending source of power. Coal and water power could be forgotten.”[3] Even in the midst of tragedy, he noted the promise of scientific advancement.

Merrill’s faith in both science and religion was tested in unique ways during his final years. He was witnessing the birth of a world where his beloved art of physics was being used to create terrifying weapons. The end of the war failed to bring security, instead ushering in a new era of uncertainty with the old order of things swept away and new powers taking the world in unexpected directions. At the same time, his beliefs in the divine science he esteemed in Latter-day Saint health codes were tested by the ailment of another important woman in his life. He moved through all these trials, along with his own declining health, with remarkable optimism and grace. His characteristic fire abated in his later years, leaving him filled instead with magnanimity. One acquaintance noted, “He was an exemplar in positive utterance. This had beautifully mellowed in his later years.”[4]

Questions and Answers

Now in his late seventies, Merrill’s increasing age did not diminish his workaholic tendencies. He sometimes stayed at his office from the early morning until eight p.m.[5] His apostolic duties consisted of meeting with and training missionaries, counseling couples with troubled marriages, and generally meeting with any person who walked in the door. The Church remained a close-knit organization, with members having direct access to their leaders through several different channels. Members who wrote a letter to Merrill usually received one in return. Fortunately, a robust record of his apostolic correspondence from this period is open to the public. The letters, combined with the experiences recorded in his journal, reveal Merrill as a compassionate counselor who wrestled with questions presented by members from all walks of life. He was not above admitting his ignorance on certain doctrinal matters, but he was also a staunch defender of the faith when challenged.

His journal notes marriages, divorces, and meetings with missionaries, as well as several encounters with some of the more fanatical members of the faith. On one occasion, a member calling on the phone informed Merrill that “sometimes he is tempted to believe he is Satan—other times the Holy Ghost [and] others it is his duty to [commit] suicide.” The next visitor in Merrill’s office “announced that the God had specially called him a High Priest to the task of setting the world in order” and that he was “the one mighty and strong” referred to in one of Joseph Smith’s revelations.[6] Merrill consoled the first visitor but offered no commentary on the next; however, it is safe to assume his claims were not accepted.

In dealing with Church members, Merrill was direct but firm. Writing to one member who was excommunicated for practicing plural marriage, Merrill declared, “Apparently you claim, brother, that you still hold the priesthood, that excommunication did not take it from you. If it did not take it from you has it taken it from anyone who has been excommunicated from the Church? You know well that what the Priesthood binds on earth shall be bound in Heaven.”[7] At the same time, Merrill was remarkably open about polygamy and its history within the Church. When a member wrote inquiring about Joseph Smith’s practice of plural marriage, he wrote back, “I have read the affidavits of several women who claimed that they were sealed to the Prophet Joseph . . . I married a granddaughter of John Taylor and Orson Hyde. She knew her grandfathers well and from them and their wives she learned that ‘polygamy,’ it is commonly called, was practiced in Nauvoo. I myself am the oldest son on my father’s fourth wife and from the things that I heard talked about and the things I had read I am absolutely convinced that the Prophet Joseph Smith was ‘sealed’ to other women besides Emma Smith.”[8]

When it came to his own feelings about polygamy, he wrote, “The Lord tested his people in the [18]80’s. The Presidency called upon the leaders to stand loyal to the Church during a time of persecution. . . . He found them loyal and true, and then the practice of plural marriage had served a beneficent purpose. The enemies had come upon the Saints. The Lord had proved their leaders. He gave the law of plural marriage to the Church. He then revoked that law.”[9]

Merrill didn’t avoid questions on difficult topics, but he also showed little equivocation when he didn’t know the answer to a question. Marion G. Romney, called as Assistant to the Quorum of the Twelve in 1941, remembered an encounter with Merrill while they were riding together on a train. The younger man asked Merrill for advice on what he should speak about in the upcoming general conference. Merrill replied, “I don’t know, Brother Romney, but one thing I can tell you is that neither you nor I need to declare any new doctrine.”[10] When a letter arrived asking about unusual spiritual manifestations in Church temples, Merrill responded that he had “heard some stories about the wonderful manifestations in the temple” but that “some of them were certainly exaggerated.” He concluded, “I suggest that you spend no time in your classroom in trying to unravel mysteries or interpret hidden prophecies. We may well wait for these things until we get on the other side.”[11]

On the more controversial topics, Merrill followed his own advice. During Merrill’s time the Church practice of not ordaining men of African descent to the priesthood was less controversial than it became in the following decades, but questions concerning the practice did occasionally cross his desk. In response to one such letter, Merrill wrote back, “From the beginning of our missionary work we have not been going especially to the colored people. This, not because we have any prejudice against the colored people as such, but because they may not have the priesthood, and why, we do not know—the Lord has not revealed it.” He did mention one prevalent theory for the practice at the time, writing, “Some people in Church believe the reason is that the spirits of the colored people were neutral in the Great War in Heaven.” Merrill did not express specific acceptance or rejection of the theory. He concluded, “So as one member of the Church replied when asked why the Negro may not hold the Priesthood said, ‘I do not know, ask the Lord, and that is all that can be said of the matter.’”[12]

In matters of undefined doctrine, Merrill stressed compassion over strict observance of Church policy. When a bishop wrote in asking about how to conduct services for a stillborn child, Merrill wrote back, “It is my understanding that stillborn infants may not receive an official burial under the auspices of the Church, but the parents are at liberty to do as they would like. . . . If it gives comfort to the parents it should not be refused. When the spirit enters the body is not known. The Church does not know . . . if in a private capacity you can serve the parents in a way that will give them comfort you are not prohibited from doing so.”[13]

Merrill also stressed a course of moderation in observance of Church teachings. One woman wrote to Merrill asking for assistance because her “husband has become so religious he thinks of nothing else.” She continued, “He is so strict in every way, we are very unhappy . . . Sunday has become a day to dread and I don’t feel that this is right.”[14] Merrill sent back an official Church document on sabbath observance, but added, “May I say that all experts teach that the normal child should be led and not driven. Its feelings and views must be treated with respect, and reasoned with. Children may be led through kindness to see what is right to do, and generally they will respond.”[15]

Extending Forgiveness

Merrill softened during his final years, and the fiery partisanship of his earlier life receded in favor of a more congenial approach toward his apostolic duties. Several remaining letters from his final years came from remorseful missionaries who lied to Merrill in their initial interviews and then wrote later, confessing and asking for forgiveness. After nineteen months of full-time service, one young elder wrote with contrition, “I well remember the day you interviewed me and you asked me if I was morally clean. I said yes and that’s all there was to it. I lied right to the face of an Apostle of the Lord, no worse than those Sons of Perdition who will look in the face of God and say he isn’t true. May he be merciful to me, and in some way may I repay you for the wrong that I have done.”[16] Merrill wrote back, “There is nothing that I can say that will change the situation, but I advise you to forget anything you may have done in the past that you now feel was not right and of which you have repented and have been forgiven. There is nothing more you can do except to remember that true repentance means to repair the wrong and turn away, never repeating. Your letter indicates that you have done this. And from the joys you experience in your missionary work, it is evident that the Lord has forgiven you.”[17]

At other times instead of being asked to forgive, Merrill acted as an intermediary for those who needed to forgive others. One heartbroken missionary wrote about his fiancée back home, who had broken the Church standard of chastity before they became a couple. When she confessed to the missionary only days before his departure, he was upset. He wrote to Merrill, describing the entire episode, “Well, Sir, I took it pretty hard, so hard in fact that she finally told me that the story was false, that she had just hatched it up to teach me not to distrust her.” The missionary left for Europe, his faith in his sweetheart restored. Months later, the young lady was called on a mission herself. In her worthiness interview, she confessed to Merrill that she had told the truth initially and had lied when her fiancé was disturbed by the story. She wrote an earnest letter to him, pleading, “Please forgive me for lying to you then but at the time I felt that I had to. That is what I discussed with Bro. Merrill. He told me that I didn’t even need to tell you but the Lord knew my heart and that I was repentant. He made me feel I was worthy of you. But now that is up to you.”

The missionary wrote to Merrill, “I feel like my heart has been crushed into a million pieces,” continuing, “I don’t mean to imply that I consider myself the personification of righteousness [but] all my life I’ve been taught that I should marry a girl whom I knew was clean and who I would want to be the mother of my children, and when I hear some of the missionaries who preach about chastity say they would rather go down to their graves unmarried than to marry a girl who had fallen into such transgression, I have felt to join them.” He concluded, “What shall I do? . . . I have been shedding bitter tears all through the course of writing this letter.”[18] Merrill’s reply came back, “You seem greatly disturbed. . . . The thing of which you write is a transgression that the Lord will forgive on sincere repentance. Why should not you? With the help of the Lord you can overcome your worry and your trouble, and you will; and doing this, you will feel happy indeed.”[19]

The Word of Wisdom

While Merrill was moderate in his views of most things, his opinions concerning the health code of the Latter-day Saints might be seen as more out of the mainstream by modern members of the Church. Along with John A. Widtsoe, Merrill advocated a stricter interpretation of the law than the majority of their fellow Saints. The Word of Wisdom came from an 1833 revelation given to Joseph Smith, and was originally declared to be given “not by commandment or constraint.”[20] It was followed with varying degrees of rigor during the first century of its observance.[21] During the early twentieth century, the Word of Wisdom was given greater emphasis, beginning with Church President Joseph F. Smith and his successor Heber J. Grant. Merrill came to the apostleship when Grant’s campaign to make the law a standard part of the Church was at its height, due largely in part to the national battle over Prohibition. For years, Merrill served on the Church Anti-Liquor and Tobacco Committee, and he believed firmly in the principles of the Word of Wisdom.

When a concerned Church member wrote Merrill asking about a supposed smoker she witnessed serving in a Church calling, he wrote back, “You ask three questions: 1. Should smokers be used as ward teachers? 2. Do we have ‘smoking quorums’ organized as such? 3. Should smokers hold office and administer the sacrament? My answer to each of these is no, except on the promise of repentance which they will keep. . . . Of course, everyone has his free agency. The Church will not compel anyone against his will.”[22]

In expressing these views, Merrill was in sync with the mainstream of Latter-day Saint thought in his day. Outside of the strict prohibition on alcohol, tobacco, coffee, tea, and harmful drugs, the Latter-day Saint interpretation on the Word of Wisdom left plenty of room for ambiguity, and there seemed to be no end to members’ speculation on which substances were allowed. At a talk given to a small audience, Merrill addressed the widely varying interpretations of the law, saying, “The Word of Wisdom in a very brief outline. Some say the Word of Wisdom is literally what it says and that it is binding [and] that anything it doesn’t say is not a part of it.” He continued, “Another interpretation is that it is an outline indicating that anything that is detrimental to or hurtful to man is, in spirit, part of the Word of Wisdom; that if it is a handicap to health, it is contrary to the spirit of the Word of Wisdom.”[23]

Where Merrill may have deviated from the course of the average Church member was in his interpretations of the health code and the use of meat. For instance, among the sermons on the wonders of science and faith is a sermon titled “Eat Meat Sparingly,” in which Merrill quotes a number of experts on the dangers of a diet filled with too much protein. The topic was important enough to him to merit inclusion in the first set of radio broadcasts he carried out for the Church in 1931, and again in 1945.[24]

The original revelation declared “flesh also of beasts and of the fowls of the air” to be “ordained for the use of man with thanksgiving” but added, “it is pleasing unto me that they should not be used, only in times of winter, or of cold, or famine.”[25] In his sermon Merrill cites six different ways health could be affected through the excessive consumption of meat. His sources range from respectable physicians at institutions, including Yale and the University of Wisconsin, to J. H. Kellogg, superintendent of the Battle Creek Sanitarium.[26] The aim of the sermon is to prove the inspiration of Joseph Smith’s revelation, but it also serves to illustrate how seriously Merrill considered the scientific merit of Joseph Smith’s revelations. He believed many members of the Church were too carefree about the Word of Wisdom and needed to follow a more strict interpretation.

One of his final addresses in general conference focused on the Word of Wisdom.[27] He gave the talk, he later said, “because the people of the church feel that they are keeping this commandment merely because they do not use tea, coffee, tobacco, and liquor.” According to Merrill, “This is the negative side” of the Word of Wisdom.[28]

To his credit, Merrill genuinely lived the law as he taught it. Whether or not he became a full vegetarian is not known, but his journal is sprinkled with references to his food. He noted on one occasion, “My dinner—at home—self-prep and included canned peas, beans & corn, milk, cottage cheese, bread & watermelon, the latter delicious.”[29] At the same time, Merrill did not expect others to follow his own interpretation of the Word of Wisdom, writing to one curious member that, “In the winter time an average serving of meat once a day for an active man would not be considered breaking the Word of Wisdom.”[30]

One of the factors driving Merrill’s observance of the Word of Wisdom was the death of his first wife, Laura—a loss he may never have fully recovered from. Laura was taken by “a malady born of ignorance—a preventable malady, I believe,” he wrote in his journal.[31] He blamed himself for her death, writing, “Oh why did she have to go. Had we understood and observed well the principles of nutrition I think she might still be with me. Was her cancer not due to malnutrition and overwork?”[32] Merrill’s devotion to the Word of Wisdom was due in part to this loss and his vow after Laura’s death to “teach the principles of nutrition to my family.”[33] His belief in not eating meat also stemmed from Laura’s long struggle with cancer. On one occasion Merrill cited an expert who called “the flesh of fowl, fish, and eggs” “putrefactive foods” that, “due to the poisons developed in body during the long time they are in the digestive tract at body temperature, were the cause of cancer.”[34]

Merrill’s beliefs regarding the Word of Wisdom embody his unique fusion of faith and science. The trauma of losing the mother of his children relatively early in his life cemented his faith in both realms as a way of preventing the loss of another member of his family. Able to keep up a rigorous schedule of work and travel well into his eighties, Merrill felt he was living proof of his beliefs. “I have always lived according to my understanding of the Word of Wisdom,” he wrote in his journal, “this has contributed to my good health.”[35] However, in the final years of his life, his beliefs would undergo another severe test.

A Second Laura

During the last few years of his life, Joseph F. Merrill cared for his youngest daughter, Laura, who, like her mother, fought a brave battle against cancer. Courtesy of Merrill family.

During the last few years of his life, Joseph F. Merrill cared for his youngest daughter, Laura, who, like her mother, fought a brave battle against cancer. Courtesy of Merrill family.

A constant throughout Merrill’s life was the presence of strong women, many of whom served as his closest counselors and confidants. The system of plural marriage Merrill was raised in meant that his mother, Maria, ran the family homestead on her own, carrying out long hours of backbreaking labor to meet the needs of her family. After Merrill left home, Annie Laura Hyde became his close confidant as they fell in love and raised their family together. Just fifteen months after Laura’s passing, Merrill married Emily (Millie) Traub, who became his companion for over two decades. In the closing years of his life, his most important companion was another Laura, his daughter.

Laura Hyde Merrill was born to a dying mother. Her namesake passed when she was just nineteen months old. Her closest sibling in age was seven years older than her, and she grew up in a much different family than her siblings had, with Millie serving as the only mother she ever knew. At age eighteen, she was left in the care of her older siblings when her father and adopted mother departed to serve in the British Mission. Bright and vivacious, she graduated from Brigham Young University in 1936 and was soon awarded a scholarship to a fashion school in the East where she studied clothing design. She eventually received a master’s degree and embarked on a successful career. She was working as a purchaser for ZCMI, the Church-owned department store, in New York City when she received word of Millie’s death. Soon after, she left New York to return home and care for her father.[36] Laura’s sacrifice did not go unnoticed by Merrill. He wrote one of his sons, “Laura is a very fine and superior girl.” He marveled at how his daughter left her single life in the East to care for him, noting, “Among other accomplishments she can cook very fine dinner and serve them delightfully. This agreeably surprised me.”[37]

Though she still made occasional trips to the East on behalf of her employers, Laura spent most of her time caring for her aging father. From 1941 onward she was not only his caregiver, but his official companion at most public events.[38] Only in her twenties when she came home to Salt Lake City, she still enjoyed an active social life with her friends and Church acquaintances.[39] Laura filled the void in Merrill’s life after the death of Millie. Though his daughter provided some companionship, Merrill still struggled with loneliness in the years following Millie’s death. On one occasion he wrote of parsing through Millie’s old notebooks, writing, “In her papers were several prayers, clippings, & short essays all of which indicated her ideals and religious feelings.” He added, “She had no enemies, but possessed refined and sensitive feelings.”[40]

Five years after Millie’s passing, Merrill experienced another shock when Laura was diagnosed with breast cancer. The two reversed roles over the next few months as she underwent a mastectomy and was incapacitated for several weeks. Merrill’s journal entries from this time included constant updates on Laura’s condition, with short entries noting, “Laura was looking and feeling better,” “Laura was feeling depressed,” or “Her condition improves.”[41] Laura’s initial treatment was successful, and life resumed as normal for a time.

“The Devil Is in the Saddle”

As Merrill worried over his daughter at home, he also worried over a son living abroad. Eugene Merrill, his second youngest child, moved his young family to Berlin, serving among the occupation forces stationed there at the end of the war. As relations between the United States and the Soviet Union worsened, Merrill became deeply concerned over the possibility of his son being caught in the middle of the confrontation between the two superpowers. He understood the good his son’s work was doing in Germany. He also saw the value in the efforts of Church members to send aid to their former enemies. “Personally I think that the relief we have sent and are sending will have greater proselyting value than all of the missionaries we can send to Europe during the next ten years,” he wrote to Eugene.[42] Merrill did not want a war, but he held the view that “if we must fight Russia let us do it . . . before Russia ‘stumbles’ onto the atomic bomb.”[43] Fearing the start of another world war, he suggested “that the family get out of Germany as soon as feasible and come home to Utah.”[44]

Merrill’s letters to his son highlight his concern with the unraveling of the world, abroad and closer to home. His faith in God remained intact, but his belief in the wisdom of men waned as he saw the world headed into dangerous paths. “Who wants war?” he wrote to Eugene, “Yes, the Devil will continue to do all he can to bring trouble, misery, distress and wickedness to the Father’s children. It does seem that peace will not come until the dawn of the Millennium when Satan will be bound, but why cannot intelligent human beings, in view of all the past, know that wars never pay? Why can we not learn to live and let live?”[45]

Merrill also expressed concerns over discord within the United States. He wrote to his son, “Internally, the U.S. has a number of very serious troubles also. . . . Personal liberty for one who desires to work for what he gets seems to be rapidly vanishing entirely in the United States. What will the end be?”[46] He resigned himself to a world of growing troubles. “Whether in our country or abroad, the ultimate cause is the same—the influence of Satan. And this influence is largely manifested through a universal human trait—that of selfishness.”[47]

“Faith Is All That Can Save Her”

While Merrill worried over the larger troubles of the world, a more personal trial reemerged in his home life. Laura’s cancer returned sometime in 1949. Small notices began to appear in Merrill’s journals concerning Laura’s increasing difficulties.[48] It was clear at this point that Merrill was more of a caregiver to Laura than she was to him. When he left for a Church assignment, a granddaughter was brought in to care for Laura because her pain was unmanageable without help.[49] For the second time in his life, Merrill found himself watching over the slow decline of a woman he loved named Laura. He wrote helplessly in his journal, “Laura suffers pains in her back and left arm continuously & more or less severely. . . . No relief has been secured. Laura we are very, very sorry. What can we do? Yes, we do pray.”[50]

As Laura’s condition worsened over the ensuing months, Merrill struggled to know how to save his daughter. “She has been to doctors & nurses who offer her no hope or relief,” he recorded, “Seemingly faith alone can save.”[51] When his first wife was diagnosed with cancer, Merrill used all of his influence to try and find a scientific treatment for the disease. He again followed this approach, noting new cures for cancer as they appeared in newspapers, and attempting to find new drugs to fight the disease. He also encouraged Laura to begin a program of fasting and other holistic treatments.[52] None of these approaches curbed the spread of the cancer. Laura was forced to take large amounts of painkillers, Merrill noted she was “doped most of the time, due to pains.”[53] Sick with worry, he wrote, “Laura’s condition is only fair. Faith is all that can save her.”[54]

During the spring of 1950, Laura languished in the hospital, suffering as her body wasted away. Merrill visited her every night, though on at least one occasion her pain was so severe she refused any visitors, even her father.[55] She received priesthood blessings from Merrill and others, sometimes more than one a day, but her condition deteriorated.[56] Members of the family maintained a constant vigil, sometimes staying overnight in the hospital to assist.[57] Merrill recorded her final days in his journal in excruciating detail. He wrote, “During the night, about 1:00 am, Laura called ‘hungry’ and with seeming great relish, drank a glass of orange juice, a glass of tomato juice, one after another with apparent relish. . . . A little later she said, ‘Let me stay here, please, let me stay here please’ as a prayer.” He lamented, “Laura so wanted to live! A little while before passing she opened her eyes, looked around and said, ‘hello.’ This was her last word.”[58] Laura Merrill passed away on 11 May 1950 at the age of thirty-four.

Other than to record the events of her passing, Merrill never commented on the death of Laura. He recorded minor details about the dispersion of her belongings, but never wrote down his feelings about the death. His own passing came less than two years after hers, and the loss may have never lost its sting long enough for Merrill to fully come to terms with it. He records no bitterness over her death, and never saw fit to tackle the difficult questions accompanying the passing of one so young. He did not speak at the funeral, but William L. Woolf, the bishop of his congregation, undoubtedly close to Merrill and Laura, attempted to provide comfort during the services. Speaking in Merrill’s own terms, Woolf said, “We do not lose faith in science because science was not able to prolong her life. . . . Man will live forever after every disease has been conquered because it has been so ruled by our Father in Heaven; nor do we lose faith in our Father, because he has not prolonged the life of this, our sister, . . . so the faith which has been exercised in the behalf of Sister Merrill does not die nor pass away any more than does she.”[59]

Laura’s death does not appear to have affected Merrill’s faith in the Word of Wisdom as a divine health code. The last address Merrill gave in general conference featured the Word of Wisdom as one of its major themes.[60] However, the loss of a second Laura undoubtedly served as a reminder of the lack of control over human events universally felt by both scientists and Apostles. He never commented on the failure of the treatments to save Laura, only expressing his grief over her pain and passing. In the years following the death of his first wife, his first Laura, he expressed guilt for not following the principles of nutrition found in the teachings of the Church and his own scientific research. With his second Laura, he received a chance to employ all his knowledge, yet the outcome was the same. For a third time, the most important woman in his family, this one in the prime of her life, was taken by a process undeterred by the best efforts of faith and science to preserve her life. He undoubtedly wrestled with the realization of his own helplessness, regardless of the capacity of his knowledge or the strength of his faith. Regardless, his devotion to faith and reason remained unshaken in the wake of Laura’s death.

Keeping the Course

In the wake of Laura’s death, Merrill showed no signs of slowing down in regards to meeting the demands of his Church duties. One of his fellow Apostles later said, “I marveled at his energy. Apparently, he never got tired; he loved the truth. He loved the truth of science, but he loved more the truths of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.”[61] His travels continued to take him throughout the United States. Nearly every weekend he traveled to a different location to hold Church meetings, ranging from rural towns in Utah to the growing cities on the coasts of California.[62]

His emphasis on thrift impressed those he met with during his travels. Glen G. Fisher recalled picking up Merrill to attend a stake conference in Vancouver, Canada. When Merrill arrived at his hotel, he booked a single room for both of them, explaining that he didn’t want to waste any money. Fisher was at first alarmed because he thought the aim was for both of them to sleep in the same bed. He was relieved to see two separate beds when arrived at their room. The next day they arose at six a.m. and ate a modest breakfast of rolled oats at a small, inexpensive café. When Merrill thought Fisher was going to waste food, he chided him, saying, “Brother Fisher we believe in the gospel of the clean plate.” Fisher wrote in his journal, “Elder Merrill was very much opposed to spending Church money unwisely. He refused to eat on the train because it was too expensive.’[63]

In his final public speeches, some fiery political discourse characteristic of Merrill’s younger days reasserted itself. In the spring of 1950, he gave a fervent address in general conference condemning corporate greed, labor unions, and “office-hungry politicians, longing for the emoluments, influence, and power of public office.” Declaring he was “speaking on my own responsibility,” he delivered a stern rebuke to politicians who “have courted, and are courting, the support of selfish, ambitious, and powerful leaders of labor unions, as well as the ne’er-do-well elements in our population.” At the end of the talk he thundered, “We are faced in this country with two alternatives, repentance or slavery—turn away from indulging in the unreasonable, excessive, and wicked selfishness manifest in many of the things we do or lose the freedoms that have been our pride and glory. . . . Yes, it is repentance or industrial slavery.”[64]

Tackling political topics directly in a Church general conference caused some controversy, and Merrill addressed the question of the mingling of church and state in another conference address given a few months later. He later noted, “A few days following the annual conference, a lady spoke to me on the street and asked how I dared to mix politics and religion in a general conference address. My reply was that I understand our religion is essentially a way of life and therefore covers in a broad way the whole field of human moral relations. . . . We do not limit our religion to the teaching of a set of theological doctrines.”[65]

These addresses typify the final stage of the evolution of Joseph F. Merrill. Raised in the insular world of the Church-dominated Cache Valley, when he arrived at the university, he became acutely aware of the divide between church and state in Salt Lake City. Embracing the world of secular learning but retaining the beliefs of his youth, he found himself, as he put it, “between the devil and the deep blue sea.” He attempted to walk that path for the majority of his life, finding compromises between the worldly concerns of his work at the university, his political ambitions, and his devotion to his faith. Now in his final days, he abandoned these artificial boundaries and proclaimed what he thought was right and just, regardless of the sensitivities of the people around him. Entering the eighth decade of his life, with little time to waste, he let go of any pretense, and gave his prescription to solve the troubles of the day. “Yes, among the troublous situations that America faces are inflation, communism, and the monopoly of labor union bosses; and the most imminent of these three are inflation and monopoly,” he declared. “Both of these would disappear overnight if all concerned would immediately repent and live the Golden Rule.”[66]

Going to Sleep

Throughout Merrill’s life, he witnessed the slow decline of several of his loved ones but was spared from suffering any significant decline on his own part. By 1952 he was older than any of the General Authorities, including new Church President David O. McKay. Though he joked to one of his sons, “Well, you know I am getting very, very old,” he remained remarkably healthy toward the end of his life.[67]

Less than two weeks before his death, Merrill attended a stake conference in Los Angeles. One of the leaders present later related, “He attended Sunday morning’s priesthood meetings, spoke at that meeting, and then at the ten o’clock meeting, went with us to lunch, following which I said, ‘Elder Merrill, don’t you think you had better take a rest now?’” Merrill replied, “Take a rest? Why?” The stake officer replied he thought Merrill would like rest after a long morning, and the day’s work still ahead of him. Merrill simply said, “Why should I lie down? Come on, let’s attend to the duties.” The leader later related the incident to President McKay, remarking, “He is as active as a young man in his fifties.”[68]

There is no evidence Merrill felt any intimations of his coming death, though in the last months of his life his mind seemed to continually turn toward his early youth, as if he was beginning the process of reflecting back and taking stock of his roots and accomplishments. He mentioned the largesse of his father, Marriner W. Merrill, on two separate occasions in general conference, citing his generosity during a particularly difficult famine in Cache Valley.[69] On another occasion he wrote to an interested inquirer about “our beautiful doctrine of Salvation for the Dead,” expressing his belief that God “has provided a way for everyone born into mortality to hear and accept the gospel either in this life or the life beyond the river of death.” He added, “This is what my father taught, and this is what I believe.”[70]

In one possible act of premonition, Merrill signed a will less than three weeks before his death, expressing a desire to “make court action unnecessary in the settlement of my estate when I pass.”[71] He continued a regular work schedule. In the final entry in his journal, he noted, “Business as usual, . . . busy with usual matters.”[72]

On the final night of his life, he conducted a stake conference in Salt Lake City, speaking to a large congregation. Afterward he retired to the home of his son Rowland, where he lived following the death of his daughter Laura. He visited with several members of the family, and then retired to bed. President McKay later described his passing: “Sometimes towards morning, Brother Merrill fell asleep, the last earthly sleep. There was evidence of no struggle, no coverlet was moved or disorderly. Presumably about 4 o’clock last Sunday morning Elder Merrill awoke in the morning of eternity.”[73]

Notes

[1] Joseph F. Merrill, The Truth-Seeker and Mormonism (Independence, MO: Zion’s Press and Printing Company, 1946), 51.

[2] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 6–9 August 1945, Merrill Papers, box 2, folder 3, BYU.

[3] Merrill, Truth-Seeker, 59.

[4] “Tributes to Elder Merrill,” Improvement Era, March 1952, 207.

[5] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 4 January 1946, Merrill Papers, box 2, folder 4, BYU.

[6] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 16 July 1946, Merrill Papers, box 2, folder 4, BYU.

[7] Joseph F. Merrill to J. W. Musser, 5 December 1951, Merrill Papers, box 20, folder 2, BYU.

[8] Joseph F. Merrill to E. L. Edwards, 1 August 1947, Merrill Papers, box 21, folder 9, BYU.

[9] Joseph F. Merrill to J. W. Musser, 5 December 1951, Merrill Papers, box 20, folder 2.

[10] F. Burton Howard, Marion G. Romney: His Life and Faith (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft: 1988), 163.

[11] Joseph F. Merrill to Anna Christensen, 23 October 1951, Merrill Papers, box 20, folder 2, BYU.

[12] Joseph F. Merrill to J. W. Monroe, January 26, 1951, Merrill Papers, box 20, folder 2, BYU. The doctrine of premortal neutrality was a popular theory within the Church for the priesthood restriction and was taught by several of Merrill’s contemporaries in different settings, but never became an official teaching of the Church. See Bryant S. Hinckley, Sermons and Missionary Services of Melvin J. Ballard (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1949), 140, 248.

[13] Joseph F. Merrill to Parley J. Shaffer, 4 October 1951, Merrill Papers, box 20, folder 2, BYU.

[14] Mrs. Don Horn to Joseph F. Merrill, 11 February 1951, Merrill Papers, box 20, folder 2, BYU.

[15] Joseph F. Merrill to Mrs. Don Horn, 14 February 1951, Merrill Papers, box 20, folder 2, BYU.

[16] (Name withheld) to Joseph F. Merrill, 15 May 1950, Merrill Papers, box 21, folder 1, BYU.

[17] Joseph F. Merrill to (name withheld), 31 May 1950, Merrill Papers, box 21, folder 1, BYU.

[18] (Name withheld) to Joseph F. Merrill, 24 May 1949, Merrill Papers, box 21, folder 1, BYU.

[19] Joseph F. Merrill to (name withheld), 1 June 1949, Merrill Papers, box 21, folder 1, BYU.

[20] “Revelation, 27 February 1833 [D&C 89],” p. [113], The Joseph Smith Papers.

[21] See Paul H. Peterson, “An Historical Analysis of the Word of Wisdom” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1972).

[22] Joseph F. Merrill to E. N. Neubert, 15 June 1951, Merrill Papers, box 21, folder 4, box 21, folder 4.

[23] “Notes on a Talk by Dr. Joseph F. Merrill,” 25 February 1949, Merrill Papers, box 21, folder 4.

[24] Merrill, Truth-Seeker, 247.

[25] Doctrine and Covenants 89:12–13.

[26] Merrill Truth-Seeker, 253–55.

[27] Joseph F. Merrill, in Conference Report, 5–7 October 1945, 135.

[28] “Notes on a Talk by Dr. Joseph F. Merrill,” 25 February 1949, Merrill Papers, box 21, folder 4.

[29] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 21 September 1949, Merrill Papers, box 3, folder 1.

[30] Joseph F. Merrill to James A. Versluis, 31 July 1933, Merrill Papers, box 21, folder 4.

[31] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 9 June 1923, Merrill Papers, box 1, folder 1.

[32] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 9 June 1923, Merrill Papers, box 1, folder 1.

[33] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 9 June 1923, Merrill Papers, box 1, folder 1.

[34] “Notes on a Talk by Dr. Joseph F. Merrill,” 25 February 1949, Merrill Papers, box 21, folder 4.

[35] Joseph F. Merrill 1943 Journal Memoranda, Merrill Papers, box 2, folder 3.

[36] Descendants of Joseph F. Merrill and Annie Laura Hyde Merrill (Salt Lake City, privately published, 1979), 115–16.

[37] Joseph F. Merrill to Eugene Merrill, 12 January 1942, copy in author’s possession.

[38] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 22 December 1943, 4 August 1946, Merrill Papers, box 2, folder 3.

[39] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 16 February 1943, 24 October 1946, 4 July 1947, Merrill Papers, box 2, folders 3–4.

[40] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 10 August 1947, Merrill Papers, box 2, folder 4.

[41] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 12, 23, 29 May 1946, Merrill Papers, box 2, folder 4.

[42] Joseph F. Merrill to Eugene Merrill, 16 April 1946, quoted in Dear Eugene, comp. Barbara M. Merrill and Barbara Jean M. Galbraith (unpublished document, copy in author’s possession), 11.

[43] Joseph F. Merrill to Eugene Merrill, 6 September 1946, in Dear Eugene, 19.

[44] Joseph F. Merrill to Eugene Merrill, 23 April 1948, copy in author’s possession.

[45] Joseph F. Merrill to Eugene Merrill, 2 June 1950, copy in author’s possession.

[46] Joseph F. Merrill to Eugene Merrill, 9 September 1948, copy in author’s possession.

[47] Joseph F. Merrill, in Conference Report, 1–3 October 1948, 61.

[48] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 29 November 1949, Merrill Papers, box 3, folder 1.

[49] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 5 December 1949, Merrill Papers, box 3, folder 1.

[50] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 6 December 1949, Merrill Papers, box 3, folder 1.

[51] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 31 December 1949, Merrill Papers, box 3, folder 1.

[52] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 24 January 1950, 14 March 1950, 6 February 1950, Merrill Papers, box 3, folder 1.

[53] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 18 April 1950, Merrill Papers, box 3, folder 1.

[54] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 21 April 1950, Merrill Papers, box 3, folder 1.

[55] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 24–25 April, 24 May 1950, Merrill Papers, box 3, folder 1.

[56] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 8 May 1950, Merrill Papers, box 3, folder 1.

[57] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 9 May 1950, Merrill Papers, box 3, folder 1.

[58] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 11 May 1950, Merrill Papers, box 3, folder 1.

[59] “Funeral Services of Laura Hyde Merrill,” Merrill Papers, box 14, folder 3.

[60] Joseph F. Merrill, in Conference Report, 6–9 April 1951, 53.

[61] Joseph Fielding Smith, “He Accepted the Restored Gospel as Divine Truth, Without Reservation,” Deseret News, Church Section, 7 February 1952, 3.

[62] Joseph F. Merrill to Eugene Merrill, 29 October 1951, copy in author’s possession.

[63] Glen G. Fisher Journal, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[64] Joseph F. Merrill, in Conference Report, 6–9 April 1950, 61–62.

[65] Joseph F. Merrill, in Conference Report, 29–30 September, 1 October 1950, 121.

[66] Joseph F. Merrill, in Conference Report, 29–30 September, 1 October 1950, 121.

[67] Joseph F. Merrill to Eugene Merrill, 18 December 1951, copy in author’s possession.

[68] Story told by David O. McKay at JFM funeral, “Pres. McKay Presides at Services for Elder Joseph F. Merrill,” Deseret News, Church Section, 7 February 1952.

[69] Joseph F. Merrill, in Conference Report, 29–30 September, 1 October 1950, 125, 6–9 April 1951, 56.

[70] Joseph F. Merrill to Claude Richards, 29 June 1951, Merrill Papers, box 20, folder 2, BYU.

[71] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 17 January 1952, Merrill Papers, box 3, folder 3.

[72] Joseph F. Merrill Journal, 31 January 1952, Merrill Papers, box 3, folder 3.

[73] “President McKay Presides at Services for Elder Joseph F. Merrill.”